#accompanying image has no meaningful organization it's just there to make me look insane. enjoy

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

hello join me in thinking about some books and authors that are, or might be, part of s5′s intertextuality

5.10 in particular offered specific shout outs, and also u know i’m always wondering what might be ahead so i have some ideas on that:

- first, as mentioned in a previous ask post, i know i wasn’t alone in keeping an eye out for 5.10 parallels to the lost weekend (1945) the film that gave episode 1.10 its name and several themes - or to the 1944 book by charles r jackson which the film is based on

- s5 has not been shy about revisiting earlier seasons, especially s1. altho i feel that 1.10′s parallels to the lost weekend centered characters other than jughead (mostly betty), a 1.10-5.10 connection involving jughead and themes from jackson’s story (addiction, writers block, self reflection) seemed v possible if not inevitable

- but like,, , for a hot minute after the ep, i was really stumped on understanding how anything from the book or film could apply, even tho the pieces were almost all there

- jackson’s protagonist don birnam goes thru and comes out the other side of a harrowing days-long drinking binge that could be compared to jughead’s one-night hallucinogenic writing retreat

- but jughead is struggling primarily with traumatic memories, not addiction and self control like birnam. and tho drinking activates birnam’s creativity, it paralyzes his writing as he gets lost in fantasies; he’s never published anything. jughead’s drug trip recreates circumstances that already helped him write one successful book. even the rat that startles him mid-high doesn’t line up with birnam’s withdrawal vision of a dying mouse, symbolic of his horror at his own self-destruction thru alcohol

- and maybe the most visible discordance: in the film there’s a romantic motif around a typewriter. first it’s an object of shame; birnam’s failure to write, tied up with his drinking, makes him flee his relationship. he tries to pawn the typewriter for booze money and finally a gun when shooting himself feels easier than getting sober. but with the help of relentless encouragement from girlfriend helen, he quits drinking, commits to her, and focuses on typing out the story he’s dreamt of writing. rd goes so far to avoid setting any comparable scenario that jughead has brought a wholeass printer into the bunker so there can still be a physical manuscript to cover in blood by the end, even without his own typewriter. the subtle detail of his laptop bg image is a little less noticeable than his avoidance of betty’s gift

- tabitha might be closer to a parallel than jughead is, but she’s still no helen. both refuse to take advantage of the inebriated men in their care, but birnam takes advantage of helen, financially and emotionally. jughead refused a loan from the tate family and now has resolved to deal with his shit before he considers a relationship with tabitha. instead of helen’s relentless and unwelcomed attempts to get birnam sober, tabitha reluctantly agrees to help jughead trip safely bondage escape notwithstanding. she even helps him get the drugs.

- whatever potentials exist for parallels to jackson’s story, they were not explored for this episode. ok so why tf am i even talking about this? what was there instead?

- i have arrived at the point

- s5 has been revisiting s1, not directly but with a twist. and jughead’s agent samm pansky is back. u may recall, pansky is named for sam lansky

- jughead’s trip-thru-trauma is a story device tapped straight from lansky’s book ‘broken people’

- lansky is like if a millenial john rechy wrote extremely LA-flavored meta but just about himself no jk very like a modern successor to charles r jackson. both play with the boundary between memoir and fiction. lansky is gay; jackson wrote his lost weekend counterpart as closeted and remained closeted himself until only a few years before his death. both write with emotional clarity and self-scrutiny on the experiences of addiction, sobriety, and the surrounding issues of shame and self worth

- i feel like a fool bc after this ep i had been thinking about de quincey and his early writings on addiction (c.1800s), but i failed to carry the thought in the other direction, to contemporary writers in the genre, to make this connection sooner

- lansky’s second book, broken people, follows narrator ‘sam’, mid-20s, super depressed, hastled by his agent to write a decent follow-up to his first book, but too busy struggling with his self-worth and baggage from several past relationships. desperate, he takes up an offer to visit a new age shaman who promises to fix everything wrong with him in a matter of days. not to over simplify it but he literally spends a weekend doing psychedelics and hallucinating about his exes. jughead took note

- unless u want me to hurl myself into yet another dissertation about queer jughead, i think his parallel to sam - who, unlike jughead, has considerable financial privilege and whose anxieties center on body dysmorphia, hiv scares, and his own self-centeredness - pretty much ends there

- But,, the gist of the book could not be more harmonius with a major theme shared by the 2 films that inform the actual hallucination part of jughead’s bunker scene: mentally reframing past relationships to get closure + confronting trauma head-on in order to move forward

- so that’s neat. what other book and author stuff was in 5.10?

- stephen king and raymond carver get name dropped. i’m passingly familiar with them both but u bet i just skimmed their wiki bios in case anything relevant jumped out

- like jughead, carver was a student (later a lecturer) at the iowa writers workshop. also the son of an alcoholic and one himself

- i recall carver’s ‘what we talk about when we talk about love’ is what jughead was reading in 2.14 ‘the hills have eyes’ after he finds out about the first time betty kissed archie (at that time he does not respond as would any of carver’s characters)

- this collection of carver stories deals especially with infidelity, failings of communication, and the complexities and destructiveness of love. to unashamedly quote the resource that is course hero, ‘carver renders love as an experience that is inherently violent bc it produces psychic and emotional wounds.’ very fun to wonder about the significance of this collection within the s2 episode and in jughead’s thoughts. and maybe now in the context of the s5 state of relationships. or, at least, the state of jughead’s writing as seen by his agent

- anyway pansky doesn’t want carver, he wants stephen king

- i have too much to say about gerald’s game in 5.10, that’s getting its own post someday soon

- lol wait king’s wife is named tabitha uhhh king’s wiki reminded me of his childhood experience that possibly inspired his short story ‘the body’ (+1986 movie ‘stand by me’) when he ‘apparently witnessed one of his friends being struck and killed by a train tho he has no memory of the event’

- no mention of that in this rd episode but memories of a train could be interesting to consider with the imagery that intrudes on jughead’s hallucination. i still feel like it was a truck but the lights and sounds he experiences may be a train

- ok now we’re in the speculation part of today’s segment

- if jughead’s traumatic memory involves trains, then it’s possible this plot will take influence from la bête humaine <- this 1938 movie is based on the 1890 novel by french writer émile zola. this story deals with alcoholism and possessive jealousy in relationships, sometimes leading to murder. huh, kind of like carver. zola def comes down on the nature side of the nature-vs-nuture bad seed question (tho i should say he approaches this with great or maybe just v french compassion). also i can’t tell if this is me reaching but, something about la bête humaine reminds me of king’s ‘secret window’ which we’ve observed to be at least a style influence on jughead post time jump

- but wow a late-19th century french writer would be a random thing to drop into this season, right? then again zola also wrote about miners, which we’ve learned are an important part of this town’s history + whatever hiram is up to this time. and most notably, zola wrote ‘j’accuse...!’ an open letter in defense of a soldier falsely accused and unlawfully jailed for treason: alfred dreyfus. archie’s recent army trouble comes to mind.

- since the introduction of old man dreyfuss (plausibly Just a nod to close encounters actor richard dreyfuss, but also when is anything in this show Just one thing) i’ve been wondering if these little things could add up to a season-long reference to zola’s writings. but i had doubts and didn’t want to speak on it too soon bc, u know, it’s weird but is it weird enough for riverdale??

- however,,,

- (come on, u knew where i was going with this)

- a24′s film zola just came out. absolutely no relation to the french writer, it’s not based on a book but an insane and explicit twitter thread by aziah ‘zola’ wells about stripping and? human trafficking?? this feels ripe for rd even outside the potentials here for the lonely highway/missing girls plot.

- that would add up to a combination of homage that feels natural to this show

- anyway pls understand i’m just having fun speculating, most of this is based on nothing more concrete than the torturous mental tendril ras has hooked into my skull pls let go ras pls let go

#accompanying image has no meaningful organization it's just there to make me look insane. enjoy#riverdale speculation#filmref#but books#adhd has me like. this is Not the post i've been trying to write for weeks but my brain gave me no choice

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

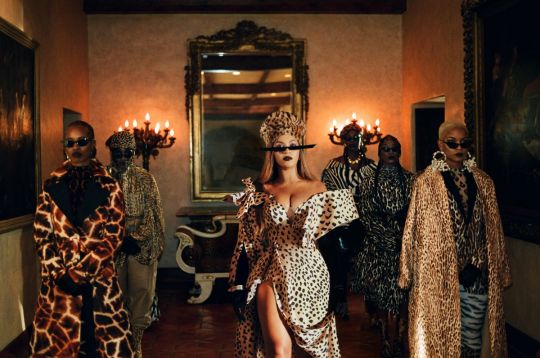

Black is King: Africa Beyoncéfied

I really enjoy watching old music videos on YouTube. It reminds me of simpler times: before CGI, insanely big budgets and, well, YouTube.

Lately, I’ve been tripping on Kate Bush. Wuthering Heights sees her as a cosmic, cherubic teenager wafting alone in a field. In Army Dreamers she’s running through a forest with a blonde kid, stopping only to mesmerise with her phantasmal, milky eyes. In Breathing she’s stuck in a Zorb until freed to join some green-faced virologists in a lagoon.

Those are all delightful, but my favourite has to be Babooshka. Shrouded in a black veil, she cavorts, improvised and imperfect, with a double-bass; like a mime artist bride's first dance at an enchanted wedding reception. Then, the chorus kicks in. Wailing, she transforms into a steampunk warrior temptress, back-lit by a heavenly white glow; her hips uttering truths even Shakira’s could never profess to know. There is one camera, one room, one performer, two outfits, and one special effect – zoom. It’s lo-def, simple, cheap, and in its way, purely spectacular.

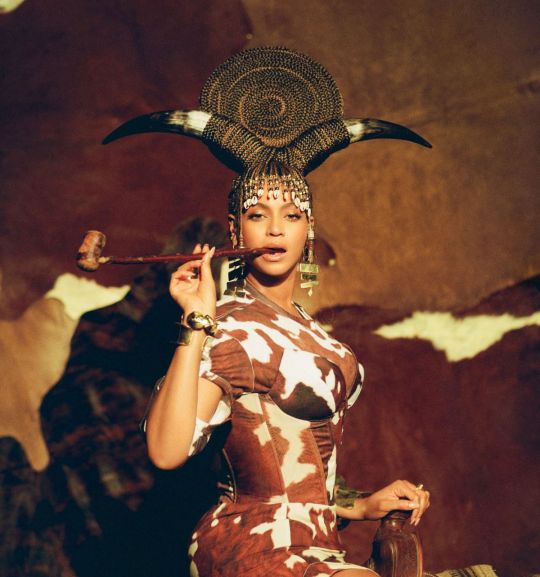

Fast-forward almost exactly forty years and, NOW STREAMING ON DISNEY+, Beyoncé releases Black is King – an ostentatious, opulent, enormous, 85-minute antithesis to the austerity of Babooska. In keeping with BEYONCÉ and Lemonade, it’s a “visual album” to accompany her (I suppose we need to call it now) “audio album” – The Lion King: The Gift. Both are inspired by last year’s CGI-update of the classic 1994 animation, following a similar storyline.

The film opens onto an “African” river. A wicker basket floats downstream, interspersed with shots of colourfully clad “Africans” in a variety of settings. James Earl Jones resonantly reiterates that “we are all connected in the great circle of life”. Under a pastel sunset, Beyoncé materialises on a beach in a flowing, white mille-feuille dress, holding a baby. There is spoken-word poetry, earnestness, shots of her daughter, a man painted blue. A group baptism ensues. Church organs sound. “You’re part of something way bigger”, she exclaims as she paints the face of a pre-pubescent boy.

The imagery steeply escalates, every colour luminescent and outfits increasingly innumerable. Beyoncé in horse-print… on a horse. Beyoncé in a painting… as Mother Mary. Beyoncé in water, dripping with red rope. It turns out we’ve been in heaven. Or space. Or somewhere beyond both - blacker and more kingly. The boy takes off, becomes a comet, hurtling towards earth. Is this in 4K? 8K? 16K? Did they shoot it in Bey, not K? Whatever the definition, it is high. Babooshka, it is not. This is irrepressible Beyoncé, lofty Beyoncé; the terrestrial goddess, progenitor of pop. To make the film, Queen Bey – who also wrote, directed and produced – drafted in a wealth First off, a word about Beyoncé’s “Africa”. It is relentlessly proud and picturesque in a way perhaps no other film about “Africa” has ever been. It is cool, hot, sensual, and sincere. It is appealingly traditional yet ambitiously modern. It’s Africa filtered first through the American kaleidoscope, then again through a diamond encrusted Beyoncéscope.

But as my Ghanaian mother relentlessly reminded people, Africa is not a country. It is the second largest continent on earth. It is not at all a singular culture. To chop up a kilo of its prettiest bits and squish them all into one tasty, palatable burger would be horribly reductive. One can fairly assume that patty-fying Africa is not Beyoncé’s intention, but if Black is King’s aim is not to represent a real-life place, what is it intended to do? In Beyoncé’s own words from a June 29 Instagram post:

I wanted to present elements of Black history and African tradition, with a modern twist and a universal message, and what it truly means to find your self-identity and build a legacy.

So it’s an idealised agglomeration of cultural concepts in service of Beyoncé’s ideas about her true heritage, and by association, those of anyone that identifies as black. Pastiche-ifying Africa. Fair enough.

But as I watch, innumerable questions arise, thudding inside my skull to the rhythm of jovial afrobeats: Where is the line between race and culture? Where does glorifying one’s ancestry end and appropriating a foreign culture begin? What legitimate connection does a billionaire American musician have to the African continent (where she has rarely visited and even more rarely performed)? Does being a dark-skinned American, 10-15 generations removed from your African ancestors, deliver a free pass to portray a place of 1.3 billion people you have barely been to?

What if Beyoncé was white, but born and raised in Ethiopia, and she made this same film? Is Beyoncé, in fact, the best – or only – person to show a positive version of modern “Africa” to a global audience? Is she creating a falsely romanticised version of heritage for Black Americans or a necessary interpretation of the continent they have a natural, genetic attachment to? Is animal print and people in trees cool or offensive? Is it cool or offensive to present all black people as the descendants of Kings and Queens? Is Disney+ available anywhere in Africa and will it ever be?

Is this just a pop music video, geared towards Beyoncé and Jay-Z adding to their billion-dollar empire? Or is it a deeply meaningful, glamorous exposition of what it means to be black, whether diasporic or native to Africa? Is Black, in fact, King?

I can’t answer most of these questions because I could argue both sides ‘til the Beys come home. Black is King is simultaneously superfluous and necessary; respectful and insulting; clever and vapid. It’s completely absurd, and completely logical. Part of me is appalled, but the majority, absorbed; addicted.

I can’t look away. It’s the Beyoncé Paradox.

Many of these contentions arise because Beyoncé is so often front and centre; royally, religiously presented. In fact, the scenes without her – those dominated by West and South African rappers, singers, and nameless dancers – offer the most exhilarating, authentic, and refreshing moments. Had she chosen to purely direct rather than star, or stayed a little more in the background, her broader message may have been elevated. Instead, with her plumb in the middle, Africa is necessarily re-invented in Beyoncé’s image; moulded to fit the Beyoncé narrative - not that of the global Black diaspora, “Africans”, or nationals of its 50+ territories, hosting 2000+ languages. In this world, Beyoncé is King, albeit a benevolent one that invites her African subjects to participate in amplifying her personal glorification, ancestral identification and iconographic myth-building.

This is the artist’s prerogative, but ultimately, attributing deeper meaning to the film than it being a fundamentally superficial exercise in branding Beyoncé as Disney’s African Queen feels pretentious. Arguable, but pretentious.

That said, just as a joke is only offensive if it is insufficiently funny, when something is as beautiful, stimulating, and cool as this, does anything else matter? If people are happy to pay $7 a month and find some fantastical personal solace in it, what harm does it do? In the end, it’s a big, sexy, pop music video. Entertainment. Treated predominantly thus, it is, in its way, purely spectacular. So watch it. While Lemonade had far deeper meaning because of her proximity to the subject matter, Black is King is still Beyoncé’s most stunning video to date. Its form and existence raise challenging questions about race, heritage, culture and society, but in the end, the sheer scale and sumptuous visual onslaught will inevitably win out. Streaming now on Disney+.* (*Not available in Africa)

Black is King Trailer

youtube

Babooshka

youtube

0 notes