#WHAT are the chances that the last emperor of the Byzantine empire would fall for (insert ur muses' name)

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

/ What are the chances that a bat god would fall in love with (insert ur muses' name)-

#WHAT are the chances that the last emperor of the Byzantine empire would fall for (insert ur muses' name)#what are the chances that the god of the night sky; hurricanes; conflict; obsidian; sacrifice woums fall in love with (insert ur muse name)#what are the chances that one of the best warriors during the kurukshetra war would fall in love wit-#what are the chances that the king of ithaca who fought on the trojan war + embarked on a journey that seemed to have no end would#fall in love with (insert ur muses' name)#what are the chances that a bat god and (ur muses' title) would fall in love-#what are the chances that a man considered to be one of the most important rullers in wallachian history would fall in love with u rn-#I COULD GO LIKE THIS ENDLESSLY#im missing more but#basically; i wanna write pinning and romance and and-#im putting all of them on the table 😳

21 notes

·

View notes

Note

Is the popular headcanon that Nicky was illiterate, stupid and barbaric fitting in the stereotypes about Southern Europeans / Mediterraneans ? I’m guessing it’s from the American part of the fandom that’s choosing to not respectfully write Nicky since he is white while being virulent towards anybody that doesn’t perfected and accurately write Joe because he is MENA.

Hello!

Mind you, I am neither a psychologist, a sociologist nor a historian, so of course be aware these are my own views on the whole drama.

But to answer your question, yes, I personally think so. It definitely comes from the American side, but I have seen Northern Europeans do that too, often just parroting the same type of discourse that Anglos whip out every other day.

There is an abysmal ignorance of Medieval history – even more so when it concerns countries that are not England: there is this common misconception that Europe in the Middle Ages was this cultural backwater full of semi-barbaric people that stems unfortunately not only from trying to (correctly) reframe colonialist approaches to the historiographies of non-European populations (that is, showing the Golden Age of Islamic culture, for instance, as opposed to what were indeed less culturally advanced neighbours), but also from distortions operated by European themselves from the Renaissance onwards, culminating in the 18th century Enlightenment philosophes categorising the Middle Ages as the Dark Ages.

Now this approach has been time and time again proven to be a made-up myth. I will not go into detail to disprove each and every single one misconception about the Medieval era because entire books have been written, but just to give you an example: there was no such a thing as a ius primae noctis/droit du seigneur; people were aware that the Earth was not flat (emperors, kings, saints, etc, they were depicted holding a globe in their hands); people were taking care of their hygiene, either through the Roman baths, or natural springs, or private tubs that the wealthier strata of the population (and especially the aristocracy) owned. The Church was not super happy about them not because it wanted people to remain dirty, but because often these baths were for both men and women, and it was not that in favour of them showing off their bodies to one another. Which, you know, we also don’t do now unless you go to nudist spas. It was only during the Black Death in the 14th century that baths were slowly abandoned because they became a place of contagion, and they went into disuse (or better, they changed purpose and became something like bordellos). And, lastly, there was certainly a big chunk of the population that was illiterate, but certainly it was not the clergy, which was THE erudite class of the time. It was in monasteries and abbeys that knowledge was passed and preserved (as well as lost unfortunately often, such as the case for the largest part of classical literature).

So what does this mean? According to canon, Nicolò was an ex priest who fought in the First Crusade. This arguably means that at the very least he was a cadet son of a minor noble family (or a wealthy merchant one) who was part of the clergy. As such, historically he could have been neither illiterate nor a dirty garbage cat in his daily life.

Let’s then talk geography. Southern Europe (and France) was far, far more advanced than the North at the time and Italy remained the cultural powerhouse of the continent until the mid-17th century. Al Andalus in the Iberian Peninsula, the Italian States, the Byzantine Empire (which called itself simply Roman Empire, whose population defined itself as Roman and cultural heirs of the Latin and Greek civilisations): these places have nothing to do with popular depictions of Medieval Europe that you mainly see from the Anglos. Like @lucyclairedelune rightfully pointed out: not everyone was England during the plague.

Also the Middle Ages lasted one thousand years. As a historical age, it’s way longer than anything we had after that. So of course habits varied, there was a clear collapse right after the fall of the Western Roman Empire, but then things develop, you know?

Anyway, back to the point in question. Everything I whipped up is not arcane knowledge: it’s simply having studied history at school and spending a few hours reading scientific articles on the internet which are not “random post written by random Anglo on Tumblr who can hardly find Genoa on a map”.

Nicolò stems from that culture. The most advanced area in Europe, possibly a high social class, certainly educated, from Genoa, THE maritime superpower of the age (with…Venice). It makes absolutely no sense that he would not be able to speak anything past Ligurian: certainly Latin (the ecclesiastical one), maybe the koine Greek spoken in Constantinople, or Sabir, or even the several Arabic languages from the Med basin stretching from al Andalus to the Levant. Because Genoa was a port, and people travel, bring languages with them, use languages to barter.

And now I am back to your question. Does this obstinacy in writing him as an illiterate beast (basically) feed into stereotypes of Mediterranean people (either from the northern or the southern shore)? It does.

It is a typically Anglo-Germanic perspective that of describing Southern (Catholic) Europeans are hot-headed, illiterate bumpinks mindlessly driven by blind anger, lusts and passions, as opposed to the rational, law-abiding smart Northern Protestants. You see it on media. I see it in my own personal life, as a Southern Italian living in Northern Europe for 10 years.

Does it sound familiar? Yes, it’s the same harmful stereotype of Yusuf as the Angry Brown Man. But done to Nicolò as the Angry Italian Man (not to mention the fact that, depending on the time of day and the daily agenda of the Anglo SJW Tumblrite, Italians can be considered either white or non-white).

Now, the times where Nicolò is shown as feral are basically when he is fighting (either in a bloody war or against Merrick’s men) or when Yusuf is in danger. Because, guess what, the man he loves is being hurt. What a fucking surprise.

Nicolò is simply being reduced to a one dimensional stereotype of the dirty dumb angry Italian, and people are simply doing this because they do not seem to accept the fact that both he and Yusuf are two wonderfully complex, flawed, fully-fledged multidimensional characters.

So I am mainly concentrating on Nicolò here because as an Italian I feel more entitled to speak about the way I see the Anglo fandom treating him and using stereotypes on him that have been consistently applied to us by the Protestant Northerners. I keep adding the religious aspect because, although I am an atheist who got debaptised from the Catholic Church, a big part of the historical treatment towards Southern has to do with religion and the contempt towards Catholic rituals and traditions (considered, once again, a sign of cultural backwardness by the enlightened North).

I do not want to impose my view of Yusuf because there are wonderful Tumblr users from MENA countries who have already written wonderful metas of the way Yusuf is being depicted by non-MENA people (in particular Americans), especially (again) @lucyclairedelune and @nizarnizarblr.

However, I just want to underline that, by only ever writing Yusuf as essentially a monodimensional character without a single flaw, this takes away Yusuf’s canon multidimensionality, the right he has to feel both positive but also negative feelings (he was hurt and angry at Booker’s betrayal, allegedly his best friend, AND HE HAD EVERY RIGHT TO BE – and I say this as a Booker fan as well).

I have not been the first to say these things, it is nothing revolutionary, and it exactly complements what the MENA tumblr users in the TOG fandom have also been trying to say. Both of us as own voices people who finally have the chance to have two characters that are fully formed and honest representations of our own cultures, without stereotypes or Anglogermanic distortions.

And the frustration mounting among all of us comes from the fact that the Anglos are, once again, not listening to us, even telling us we are wrong about our own cultures (see what has happened to Lucy and Nazir).

What is even more frustrating is that everything in this cursed fandom – unless it was in the film or comics – is just a bloody headcanon. But these people are imposing their HCs as if it were the Word of God, and attacking others – including own voices MENA and Italians – for daring to think otherwise.

I honestly don’t expect this post will make any difference because this is just a small reflection of what Americans do in real life on grander scale, which is thinking they are the centre of the world and ignoring that the rest of the world even exists regardless of their own opinions on it.

But still, sorry for the length, hope I answered your question.

#i am also expecting to receive lots of shit for this but can't say i care#the old guard#tog discourse#nicolo di genova#the old guard meta

241 notes

·

View notes

Text

Clarifying the Crusades as “Defensive War”

Or How NOT to Do Crusader Apology

I felt the need to write this blogpost because there is a massive (but understandable) misconception that comes with defending the Crusades among people that know they have been smeared by liberals and revisionists, but are prone to commit serious blunders themselves because they lack historical knowledge about them. Some view it as a proper belated response after centuries of Islamic aggression which may be the case, but that is a gross oversimplification of what actually happened. But there are a lot of subtle details that get lost which result in constructing a very idealized view of the Crusades as an pan-Christian cooperation effort to destroy Islam. As an historian specialized in this time period and someone who goes at great lengths to defend them from political activists, I must advise fellow apologists to not fall into certain traps when talking about it.

The Context of Islamic Aggression

The Crusades officially began in 1095, but their origins can be traced back as further as the rise of Islam almost five centuries prior. Previously Christian lands such as Egypt, Syria, Palestine, the entirety of Northern Africa and Spain fell at Muslim rule and even then this didn’t stop further attacks all over the Mediterranean and Southern Europe from Arab pirates.

It’s important to note that the vast majority of this aggression directed at Europe was committed by the Umayyad Caliphate, which was established after the death of Ali, Muhammad’s cousin, the fourth caliph of Islam (and first Imam of Shia Islam). This caliphate practically continued the policies of expansion laid out by it’s predecessors but following the Battle of Portiers and the Second Arab Siege of Constantinople (both Christian victories that halted any expansion into Europe), the Umayyads entered a period of decay and a lot of infighting took place where they were replaced by the Abbasid Caliphate. This one was a lot less violent and more interested in consolidating it’s power by fighting rival Islamic empires than waging war on the infidels. One such rivals were the Seljuk Turks, a recently converted people that became displaced from the Turkic regions into the Middle-East.

The immediate cause of the Crusades was the Seljuk’s advance into Eastern Anatolia gobbling up huge parts of the Byzantine Empire and eventually culminated in the Battle of Mazinkert where they dealt a crushing defeat and the Emperor was captured, throwing the Empire in disarray. Alexios Komnenos was the emperor that sent letters of help to the Pope asking for relief - which was no easy task since the Catholic and Orthodox churches have parted ways over a series of theological, ecclesiastical and political disputes. Pope Urban assembled the Council of Clermont where he pledged Catholics to take up arms to

This is No “War on Terror”

A often cringy apologist statement I see thrown out is that “The Crusades were waged to stop Islamic aggression” because I know any debater is gonna pick that one apart and embarrass the one who said it. The reason why its said is because 1) apologist observes there was historical preceding violence against Christians 2) therefore the Christians are fighting back. However, it’s important to note that by the time the Crusades were declared, there was no realistic chance of Islam ever taking Europe by military power because of the dispute between the countless Islamic states like the Abbasids, the Umayyads, the Seljuks, the Fatimids and etc.

The contemporary rhetoric of the Crusades at the time was “retake the Holy Land”, not “stop the invasion”. While it’s perfectly plausible that Urban II did fear a potential invasion in the future should the Byzantine Empire collapse, the average crusader at the time did not sell his possessions and donated his lands to fund the expedition to possibly die in a far away land to preserve their Earthly way of life. He did it for the salvation and expiation of his soul - that is what he believed in. I think this isn’t acknowledged by apologists - whether they be actual Christians or secularists themselves (yes they exist) - because it’s embarrassing to admit at one point this is what Christians believed, but that is what history taught us whether we like it or not.

The one context where you could conceivably call this particular campaign a “defensive war” was to lend assistance to the Byzantine Empire, given they were in a time of crisis and needed all help they could get. Might as well call the ones to preserve the established Crusader states that were under threat. The problem is that it leads to another misconception made by Crusade defenders...

Christian Unity Was Lacking

While it’s true that Pope Urban was successful in inflaming the crowds of Europeans at Clermont about the atrocities reaped on the Christians of the East, another common misconception made by modern apologists is that they were acting like how Catholics and Orthodox do today, they were going to liberate their brethren and then leave them be. Due to the East-West Schism that took place just a few decades ago, the reality was far more cynical: The Catholic Church had no intention of restoring of restoring the reconquered lands to the Byzantine Empire and all Crusader states were to be under Latin jurisdiction, ruled by Latin Catholic monarchs with Catholic clergymen. As far as the Catholic Church was concerned, the Eastern Orthodox Church was schismatic and was to be brought into heel rather than left to coexist.

It’s well documented that Western knights disdained Byzantines for their seemingly effeminate and hedonistic manners, finding them unmanly fuccbois, while Byzantines wrote how Catholics were rough, uncivilized brutes, unworthy of being considered “Romans” and more akin to the Germanic tribes that overwhelmed the Western half centuries ago (though to be fair they weren’t entirely lying about that last part). And that is not even getting into the countless conflicts between Crusaders and Byzantines because I’d be here all day.

It’s inconvenient to point that the Crusader states were often in a very fragile state and requesting aid from Europe, since after the First Crusade was successful, many Europeans returned home and very few capable people were left to manage it. Yeah, yeah, we have better things to do so hold tight, m8s. This reality shIts all over the commitment that Christians had in solidarity for their co-religionalists. So Crusade apologists need to be careful in framing these campaigns as motivated by that motive.

There Were Actual Defensive Crusades

The real irony is that they existed after the period even if we don’t traditionally associate with them. the Fall of Constantinople heralded a new chapter in the war between the Cross and the Crescent with the Ottoman Empire beginning an expansion campaign rivaling that of the ancient Umayyads. Even before the city fell, the Ottomans had already consumed chunks of the Balkans including the entirety of Bulgaria, Serbia, Macedonia and Wallachia. Even though the Crusades to retake the Holy Land fell out of fashion by the time of their rise, the situation now changed - the enemies were right at the door instead of thousands of miles in faraway lands and the Byzantine bulwark that withstood for 1000 years is no more.

This time there would be no bullshitting - Catholics and Orthodox would have to cooperate again to deal with the Ottoman dragon and there was no time for squabbling. Cooperation was increased with Albanian Catholics and Orthodox setting aside religious differences and form the League of Lezhe, Pope Pius II interacting with Wallachian Orthodox ruler Vlad III Dracula and Catholic king Matthias Corvinus lending his Black Army to Moldavian prince Stephen III to triumph against the Ottomans at Vaslui. There were officially sanctioned Crusades like the Crusade of Varna and the Crusade of Nicopolis, but they were major Islamic victories over the Christians.

There can be no denying that the Christian campaigns (whether they were Catholic and Orthodox) against the Ottomans were defensive and fit the conventional understanding of a crusade, whether it’s a military campaign sanctioned by the Pope or simply any war waged by Christians. The reason why the Balkans are ignored is because the Holy Land Crusades are the more lasting ones in the modern public consciousness and still believed to be the cause of many political problems today between the West and the Islamic world (which is rich, since the latter never gave a flying shit about the Crusades until they were on the receiving end of colonialism for a change). Other factors can be accounted like the Protestant Reformation taking everyone’s else attention and being more comparatively significant and that these particular wars were not for people’s souls, but for their lives, their lands and loved ones.

So to my fellow apologists: be careful when you say “the Crusades were defensive wars” because if the other side is more knowledgeable than you, they are going to take up to task and debate you if they can. You need to be prepared to acknowledge the little subtleties of history and remember that the current “bro” relationship between Catholicism and Eastern Orthodoxy was not the same as it was for medieval times, let alone was a motive for the Crusades because one side viewed the other as f*gg*ts and the latter viewed the former as brainlet cavemen. And more importantly, educate yourself about the wars in the Balkans and Eastern Europe which is surely a fun subject to study since many historical legends emerged from this period like Saint Stephen, Vlad the Impaler, Skanderbeg and John Hunyadi.

They were all crusaders but you didn’t knew about it.

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

11/11/11 Tag

Thanks to @corishadowfang for the tag! Sorry this took so long but I’ve been pretty shot the past couple days.

Rules: Answer the eleven questions, make eleven of your own, then tag eleven people.

1. Do you have a WIP for NaNo? If so, what’s it about?

Sort of? I’m not really doing Nano officially, but I’m trying very hard to wrap up Blackheart this month.

2. Are there any things you’d really like to write about that you haven’t had the chance to yet?

I’ve got a story about dragons invading late medieval Europe on the backburner. It features actual historical figures that were in power at the time, like famous Polish King Casimir the Great, Pope Innocent VI, and more! Some events change due to the dragons’ invasion, like the massive war ending a power struggle in the Holy Roman Empire and ensuring Louis V, son of the previous emperor ascends to rulership, where as in our timeline he lost out to Charles VI and ended up being the Duke of Bavaria. In this story most of Europe is destroyed and the survivors flee to the Byzantine Empire, which intends to make a stand at Constantinople. The son of the dragons’ leader spends a large portion of the story being held captive in Constantinople, and is interrogated and persuaded throughout the story.

3. Plotter, pantser, or plantser?

Plantser, I guess? I plan the framework, and sometimes I have a scene I really want to make a certain way, but for the most part it’s touch and go.

4. What is your favorite part of the writing process?

The creative process. Just daydreaming about all sorts of scenes and scenarios is incredibly fun. When it comes time to put it to paper though it gets tougher.

5. What does your editing process look like?

Spellcheck and extension. I usually write a scene haphazardly and then add more dialogue and descriptions when I return.

6. Is there a scene in your WIP you’re particularly proud of? Share it!

This scene in the chapter “Field of Dreams” chapter of Blackheart, it’s my favorite chapter in the book honestly. As a prelude, how this works in Blackheart is that demons capture people and turn them into mindless beasts. Earlier on, a paladin runs into a corrupted birdwoman as he journeys through the city. He goes to kill it like all the others, but when she starts begging for help he realizes the survivor is still clinging on deep in there. He tries to bring her somewhere safe to perform a purity ritual to save her. She struggles and eventually is overcome by the corruption. The last thing she remembers before waking up in darkness is the paladin choking her as she begged for mercy.

Fianna suddenly found herself standing in nothingness. All around her, terror filled the air.

Voices of the damned screamed at her, dark visages stared from afar and corpses and flames littered the expanse.

Other corrupted lurched forward, hobbling toward her, screaming and howling as they closed in. The darkness had come to claim her at last.

She could only cower in as absolute fear gripped her heart. This really was it.

The crowd latched onto her, dozens of unholy beasts dragging her into the ground. She could feel herself falling, sinking into nothing as her soul was trapped in the nothingness.

Just as she felt her head begin to sink under, to join her body in eternal torment, a loud noise brought everything to a halt.

The beasts dragging her to the abyss suddenly paused, turning away and looking up. She too joined them in staring up into the blackness.

The sky flashed a bright white, the corrupted monsters, in unison, all crumbled away. They simply fell apart into nothing at all, scattering to the wind and leaving Fianna alone.

The screams let out a loud unified wail before the blackness, all around her, flashed wildly, vibrant colors flowing through the air and filling the void with light.

She felt numb for a moment as she found herself no longer sinking. The koutu clenched her talons as she lay on the ground, panting and heaving.

"Fianna."

Dozens of voices filled the air. Unlike the screams of the damned, these voices were clear, coherent, and sweet as honey.

She looked up, and all around her, as the void pulsed with light and color...figures surrounded her.

They were familiar. All of them.

Her family.

Her friends.

Everyone she could ever remember meeting.

One of the figures stepped forward.

She was a tall and graceful koutu, every step dignified, her eyes full of warmth and love. Her feathers were patterned the same as Fianna's...

Her feathers...?

She looked down.

The jet black feathers were changing, warping.

The blackness seemed to almost...bleed away, the feathers beginning to glow with color in the middle, expanding outwards until the blackness was a simple lining at the ends of each feather.

Soon, that tiny bit of blackness bled away, and her feathers were her own again. Her midsection was a bright and beautiful orange, while the rest of her was mainly a deep, vibrant blue.

Just like she remembered.

She looked back up at the other koutu, whose coloration and shape was the same as her own.

"Sister..." Fianna said breathlessly.

"You are free," she spoke softly.

"B-but, the demons, you were-"

"I know," her sister assured her, "I know. I am no longer here...but even though I am not here...I will always be HERE."

She pressed her hand against Fianna's chest...over her heart.

Fianna could feel herself crying again.

She reached out and embraced her sister. The older koutu returned the gesture, the two of them kneeling and hugging each other tightly.

They sat in silence like this for quite some time.

For the first time since the attack, Fianna felt alive...even though she had the sneaking suspicion she wasn't.

The paladin was right. This was better. She was thankful.

The nightmare was over.

"I missed you so much," Fianna said, her face damp with tears.

"I missed you too."

"I'm so happy we're together again."

Her sister was silent for a moment.

"...you know you're not dead, right?"

Fianna blinked.

"W-what?"

"You have to go back."

The koutu's eyes widened as comprehension dawned on her. "N-no, no!"

"I'm sorry," her sister said quietly, "I know you don't want to."

"Sister, please..."

"I can't control it, Fianna. It's your life, not mine."

"T-than how are you-"

"Because this isn't real."

Fianna's heart sank.

She was in her own imagination, dreaming about being with her family again, rather than actually being reunited.

Her grip tightened on his sister, who looked at her curiously.

"Fianna?"

"I don't want to let go..."

"Trust me, I understand," she answered quietly. For the first time, her voice too was filled with pain. "I want to be together too."

"I-I just...want it to be over."

"You have to get through this," her sister spoke, "Please. Don't end up like me."

Fianna couldn't believe this was happening.

"I want you to live. Can you do that? Please. I've been watching you, you know. I know how hard it's been...but you've come so far. You're so nearly there. Just a little more. Please...you have to hold on, okay?"

Fianna nodded.

"O-okay...okay, I'll do my best."

The two sisters looked up and stared at one another.

"I'll keep watching you. I know you can do it. Be good for me, alright?"

"O-okay."

"I'll be waiting for you, someday."

With that, everything faded away once again.

7. Is there an author that inspires you a lot?

I wouldn’t say particularly. I like certain books but I don’t really “follow” anyone like that...well, maybe some of the other writers on here.

8. Do you do anything to prepare yourself to start writing?

Put on some music and grab a drink.

9. What’s your favorite type of villain to write? To read about?

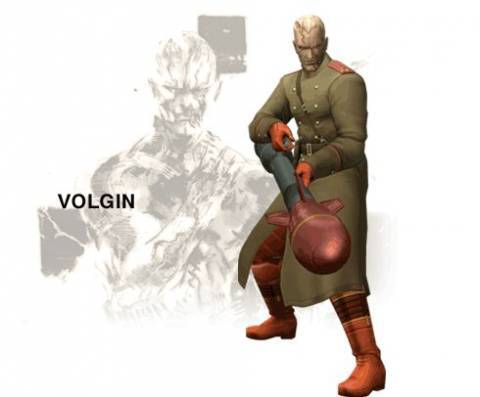

Villains that you love to hate. After so many ““““sympathetic”””” villains (this mass murderer got bullied by people that have nothing to do with who he’s killing, he’s justified!), it’s nice to have a villain that’s just plain evil and knows it. Someone that’s so shamelessly bad that you’re just dying for the heroes to give em’ his comeuppance. Also, villains and antagonists can be very different. Someone like The Boss from MGS3 is an antagonist, but she could hardly be called a villain. Sympathetic antagonists are a lot easier to root for than someone that’s out and out a bad guy.

10. What is the best compliment you’ve ever received on your work?

Probably either @lady-redshield-writes or @paper-shield-and-wooden-sword. They’ve both said so many great things I can’t even begin to remember all the nice stuff they’ve said.

11. What are your characters’ favorite animals?

Considering his shield and family crest, Alexander’s is probably the eagle. Leianna likes dogs. Lexius and Senci both like cats.

My questions:

1. Do you make steady progress in writing or work in short bursts?

2. What’s your favorite character archetype?

3. Favorite fictional hero? (Can be from any media) Has that character influenced any of your own?

4. What sort of scenes do you struggle most with? (Fights, group conversations, etc.)

5. What time period do you find yourself writing the most of?

6. Do you enjoy music, background noise or silence while writing?

7. Where’s your favorite writing spot?

8. Do you like people reading along as you write, or do you want people to wait til’ it’s all edited and done?

9. Share a random hobby besides writing!

10. If you could have your cast from your story visit another time or world, real or fictional, where would it be?

11. Have any of your characters changed or developed drastically since they were first created?

Tagging @lady-redshield-writes, @homesteadchronicles, @paper-shield-and-wooden-sword, @candy687, @ashesconstellation. Joining in, as always, is completely up to you.

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Jerusalem was Heraclius’s last moment of glory

The trip to Jerusalem was Heraclius’s last moment of glory. He fell ill soon afterward; and in the field in the 630s he was represented by other generals, who saw his most important frontiers collapse.

The future lay to the south. Muhammad died in 632, leaving behind a whirlwind prepared to move north, east, and west. The pummeling that Byzantine and Persian forces gave each other and the relative detachment of Syria, Palestine, and Egypt from Byzantine control gave the men of the desert their chance. Just as the northern barbarians had found their strength shadowing the empire they admired, so the Arabs of the desert marches had grown in strength and confidence and were prepared to seize an opportunity. If it was not divine providence that brought them to this moment, they seized it as though it were.

Defeated Theodore

In 634 the Arab armies invaded Syria and defeated Theodore, the emperor’s brother, in a string of battles. Heraclius raised a large army that attacked the Arabs near the Yarmuk River, a tributary of the Jordan, in the fall of 636. After a successful beginning, the larger Byzantine army was defeated and put to flight. Roman Syria was easily taken at that point. The Arabs capitalized on Persia’s disarray by quickly taking the whole of the frontier lands (including Mesopotamia and Armenia) and then Egypt not long afterward. Alexandria fell in 640 after a siege that lasted more than a year. At that time, Muhammad had been dead less than a decade.

What was left for ancient empire? The Balkans, the suburbs of Constantinople, most of Asia Minor, and the African outpost around Carthage that Justinian had seized at such cost. Italy remained, with as much cost as benefit, but the African base would support Constantinople for the sixty years remaining before the Arabs seized it at the turn of the eighth century. (Sicily remained Byzantine much longer: without it, the whole of Byzantine pretension might have fallen.) By the end of the seventh century, the economics of empire had caught up with Constantinople and the city population collapsed.

Heraclius died on February 11, 641, his empire fully and finally in tatters. His two sons failed to establish themselves, and it was his grandson Constans II who became emperor later that year at age eleven, at the onset of what would be a long and pointless reign. Irony alone would accompany him as he visited Rome in 663, the first emperor seen there in two centuries. He was assassinated in his bath in 668, and his successors forgot the west.

0 notes

Photo

Jerusalem was Heraclius’s last moment of glory

The trip to Jerusalem was Heraclius’s last moment of glory. He fell ill soon afterward; and in the field in the 630s he was represented by other generals, who saw his most important frontiers collapse.

The future lay to the south. Muhammad died in 632, leaving behind a whirlwind prepared to move north, east, and west. The pummeling that Byzantine and Persian forces gave each other and the relative detachment of Syria, Palestine, and Egypt from Byzantine control gave the men of the desert their chance. Just as the northern barbarians had found their strength shadowing the empire they admired, so the Arabs of the desert marches had grown in strength and confidence and were prepared to seize an opportunity. If it was not divine providence that brought them to this moment, they seized it as though it were.

Defeated Theodore

In 634 the Arab armies invaded Syria and defeated Theodore, the emperor’s brother, in a string of battles. Heraclius raised a large army that attacked the Arabs near the Yarmuk River, a tributary of the Jordan, in the fall of 636. After a successful beginning, the larger Byzantine army was defeated and put to flight. Roman Syria was easily taken at that point. The Arabs capitalized on Persia’s disarray by quickly taking the whole of the frontier lands (including Mesopotamia and Armenia) and then Egypt not long afterward. Alexandria fell in 640 after a siege that lasted more than a year. At that time, Muhammad had been dead less than a decade.

What was left for ancient empire? The Balkans, the suburbs of Constantinople, most of Asia Minor, and the African outpost around Carthage that Justinian had seized at such cost. Italy remained, with as much cost as benefit, but the African base would support Constantinople for the sixty years remaining before the Arabs seized it at the turn of the eighth century. (Sicily remained Byzantine much longer: without it, the whole of Byzantine pretension might have fallen.) By the end of the seventh century, the economics of empire had caught up with Constantinople and the city population collapsed.

Heraclius died on February 11, 641, his empire fully and finally in tatters. His two sons failed to establish themselves, and it was his grandson Constans II who became emperor later that year at age eleven, at the onset of what would be a long and pointless reign. Irony alone would accompany him as he visited Rome in 663, the first emperor seen there in two centuries. He was assassinated in his bath in 668, and his successors forgot the west.

0 notes

Photo

Jerusalem was Heraclius’s last moment of glory

The trip to Jerusalem was Heraclius’s last moment of glory. He fell ill soon afterward; and in the field in the 630s he was represented by other generals, who saw his most important frontiers collapse.

The future lay to the south. Muhammad died in 632, leaving behind a whirlwind prepared to move north, east, and west. The pummeling that Byzantine and Persian forces gave each other and the relative detachment of Syria, Palestine, and Egypt from Byzantine control gave the men of the desert their chance. Just as the northern barbarians had found their strength shadowing the empire they admired, so the Arabs of the desert marches had grown in strength and confidence and were prepared to seize an opportunity. If it was not divine providence that brought them to this moment, they seized it as though it were.

Defeated Theodore

In 634 the Arab armies invaded Syria and defeated Theodore, the emperor’s brother, in a string of battles. Heraclius raised a large army that attacked the Arabs near the Yarmuk River, a tributary of the Jordan, in the fall of 636. After a successful beginning, the larger Byzantine army was defeated and put to flight. Roman Syria was easily taken at that point. The Arabs capitalized on Persia’s disarray by quickly taking the whole of the frontier lands (including Mesopotamia and Armenia) and then Egypt not long afterward. Alexandria fell in 640 after a siege that lasted more than a year. At that time, Muhammad had been dead less than a decade.

What was left for ancient empire? The Balkans, the suburbs of Constantinople, most of Asia Minor, and the African outpost around Carthage that Justinian had seized at such cost. Italy remained, with as much cost as benefit, but the African base would support Constantinople for the sixty years remaining before the Arabs seized it at the turn of the eighth century. (Sicily remained Byzantine much longer: without it, the whole of Byzantine pretension might have fallen.) By the end of the seventh century, the economics of empire had caught up with Constantinople and the city population collapsed.

Heraclius died on February 11, 641, his empire fully and finally in tatters. His two sons failed to establish themselves, and it was his grandson Constans II who became emperor later that year at age eleven, at the onset of what would be a long and pointless reign. Irony alone would accompany him as he visited Rome in 663, the first emperor seen there in two centuries. He was assassinated in his bath in 668, and his successors forgot the west.

0 notes

Photo

Jerusalem was Heraclius’s last moment of glory

The trip to Jerusalem was Heraclius’s last moment of glory. He fell ill soon afterward; and in the field in the 630s he was represented by other generals, who saw his most important frontiers collapse.

The future lay to the south. Muhammad died in 632, leaving behind a whirlwind prepared to move north, east, and west. The pummeling that Byzantine and Persian forces gave each other and the relative detachment of Syria, Palestine, and Egypt from Byzantine control gave the men of the desert their chance. Just as the northern barbarians had found their strength shadowing the empire they admired, so the Arabs of the desert marches had grown in strength and confidence and were prepared to seize an opportunity. If it was not divine providence that brought them to this moment, they seized it as though it were.

Defeated Theodore

In 634 the Arab armies invaded Syria and defeated Theodore, the emperor’s brother, in a string of battles. Heraclius raised a large army that attacked the Arabs near the Yarmuk River, a tributary of the Jordan, in the fall of 636. After a successful beginning, the larger Byzantine army was defeated and put to flight. Roman Syria was easily taken at that point. The Arabs capitalized on Persia’s disarray by quickly taking the whole of the frontier lands (including Mesopotamia and Armenia) and then Egypt not long afterward. Alexandria fell in 640 after a siege that lasted more than a year. At that time, Muhammad had been dead less than a decade.

What was left for ancient empire? The Balkans, the suburbs of Constantinople, most of Asia Minor, and the African outpost around Carthage that Justinian had seized at such cost. Italy remained, with as much cost as benefit, but the African base would support Constantinople for the sixty years remaining before the Arabs seized it at the turn of the eighth century. (Sicily remained Byzantine much longer: without it, the whole of Byzantine pretension might have fallen.) By the end of the seventh century, the economics of empire had caught up with Constantinople and the city population collapsed.

Heraclius died on February 11, 641, his empire fully and finally in tatters. His two sons failed to establish themselves, and it was his grandson Constans II who became emperor later that year at age eleven, at the onset of what would be a long and pointless reign. Irony alone would accompany him as he visited Rome in 663, the first emperor seen there in two centuries. He was assassinated in his bath in 668, and his successors forgot the west.

0 notes

Photo

Jerusalem was Heraclius’s last moment of glory

The trip to Jerusalem was Heraclius’s last moment of glory. He fell ill soon afterward; and in the field in the 630s he was represented by other generals, who saw his most important frontiers collapse.

The future lay to the south. Muhammad died in 632, leaving behind a whirlwind prepared to move north, east, and west. The pummeling that Byzantine and Persian forces gave each other and the relative detachment of Syria, Palestine, and Egypt from Byzantine control gave the men of the desert their chance. Just as the northern barbarians had found their strength shadowing the empire they admired, so the Arabs of the desert marches had grown in strength and confidence and were prepared to seize an opportunity. If it was not divine providence that brought them to this moment, they seized it as though it were.

Defeated Theodore

In 634 the Arab armies invaded Syria and defeated Theodore, the emperor’s brother, in a string of battles. Heraclius raised a large army that attacked the Arabs near the Yarmuk River, a tributary of the Jordan, in the fall of 636. After a successful beginning, the larger Byzantine army was defeated and put to flight. Roman Syria was easily taken at that point. The Arabs capitalized on Persia’s disarray by quickly taking the whole of the frontier lands (including Mesopotamia and Armenia) and then Egypt not long afterward. Alexandria fell in 640 after a siege that lasted more than a year. At that time, Muhammad had been dead less than a decade.

What was left for ancient empire? The Balkans, the suburbs of Constantinople, most of Asia Minor, and the African outpost around Carthage that Justinian had seized at such cost. Italy remained, with as much cost as benefit, but the African base would support Constantinople for the sixty years remaining before the Arabs seized it at the turn of the eighth century. (Sicily remained Byzantine much longer: without it, the whole of Byzantine pretension might have fallen.) By the end of the seventh century, the economics of empire had caught up with Constantinople and the city population collapsed.

Heraclius died on February 11, 641, his empire fully and finally in tatters. His two sons failed to establish themselves, and it was his grandson Constans II who became emperor later that year at age eleven, at the onset of what would be a long and pointless reign. Irony alone would accompany him as he visited Rome in 663, the first emperor seen there in two centuries. He was assassinated in his bath in 668, and his successors forgot the west.

0 notes

Photo

Jerusalem was Heraclius’s last moment of glory

The trip to Jerusalem was Heraclius’s last moment of glory. He fell ill soon afterward; and in the field in the 630s he was represented by other generals, who saw his most important frontiers collapse.

The future lay to the south. Muhammad died in 632, leaving behind a whirlwind prepared to move north, east, and west. The pummeling that Byzantine and Persian forces gave each other and the relative detachment of Syria, Palestine, and Egypt from Byzantine control gave the men of the desert their chance. Just as the northern barbarians had found their strength shadowing the empire they admired, so the Arabs of the desert marches had grown in strength and confidence and were prepared to seize an opportunity. If it was not divine providence that brought them to this moment, they seized it as though it were.

Defeated Theodore

In 634 the Arab armies invaded Syria and defeated Theodore, the emperor’s brother, in a string of battles. Heraclius raised a large army that attacked the Arabs near the Yarmuk River, a tributary of the Jordan, in the fall of 636. After a successful beginning, the larger Byzantine army was defeated and put to flight. Roman Syria was easily taken at that point. The Arabs capitalized on Persia’s disarray by quickly taking the whole of the frontier lands (including Mesopotamia and Armenia) and then Egypt not long afterward. Alexandria fell in 640 after a siege that lasted more than a year. At that time, Muhammad had been dead less than a decade.

What was left for ancient empire? The Balkans, the suburbs of Constantinople, most of Asia Minor, and the African outpost around Carthage that Justinian had seized at such cost. Italy remained, with as much cost as benefit, but the African base would support Constantinople for the sixty years remaining before the Arabs seized it at the turn of the eighth century. (Sicily remained Byzantine much longer: without it, the whole of Byzantine pretension might have fallen.) By the end of the seventh century, the economics of empire had caught up with Constantinople and the city population collapsed.

Heraclius died on February 11, 641, his empire fully and finally in tatters. His two sons failed to establish themselves, and it was his grandson Constans II who became emperor later that year at age eleven, at the onset of what would be a long and pointless reign. Irony alone would accompany him as he visited Rome in 663, the first emperor seen there in two centuries. He was assassinated in his bath in 668, and his successors forgot the west.

0 notes

Photo

Jerusalem was Heraclius’s last moment of glory

The trip to Jerusalem was Heraclius’s last moment of glory. He fell ill soon afterward; and in the field in the 630s he was represented by other generals, who saw his most important frontiers collapse.

The future lay to the south. Muhammad died in 632, leaving behind a whirlwind prepared to move north, east, and west. The pummeling that Byzantine and Persian forces gave each other and the relative detachment of Syria, Palestine, and Egypt from Byzantine control gave the men of the desert their chance. Just as the northern barbarians had found their strength shadowing the empire they admired, so the Arabs of the desert marches had grown in strength and confidence and were prepared to seize an opportunity. If it was not divine providence that brought them to this moment, they seized it as though it were.

Defeated Theodore

In 634 the Arab armies invaded Syria and defeated Theodore, the emperor’s brother, in a string of battles. Heraclius raised a large army that attacked the Arabs near the Yarmuk River, a tributary of the Jordan, in the fall of 636. After a successful beginning, the larger Byzantine army was defeated and put to flight. Roman Syria was easily taken at that point. The Arabs capitalized on Persia’s disarray by quickly taking the whole of the frontier lands (including Mesopotamia and Armenia) and then Egypt not long afterward. Alexandria fell in 640 after a siege that lasted more than a year. At that time, Muhammad had been dead less than a decade.

What was left for ancient empire? The Balkans, the suburbs of Constantinople, most of Asia Minor, and the African outpost around Carthage that Justinian had seized at such cost. Italy remained, with as much cost as benefit, but the African base would support Constantinople for the sixty years remaining before the Arabs seized it at the turn of the eighth century. (Sicily remained Byzantine much longer: without it, the whole of Byzantine pretension might have fallen.) By the end of the seventh century, the economics of empire had caught up with Constantinople and the city population collapsed.

Heraclius died on February 11, 641, his empire fully and finally in tatters. His two sons failed to establish themselves, and it was his grandson Constans II who became emperor later that year at age eleven, at the onset of what would be a long and pointless reign. Irony alone would accompany him as he visited Rome in 663, the first emperor seen there in two centuries. He was assassinated in his bath in 668, and his successors forgot the west.

0 notes

Photo

Jerusalem was Heraclius’s last moment of glory

The trip to Jerusalem was Heraclius’s last moment of glory. He fell ill soon afterward; and in the field in the 630s he was represented by other generals, who saw his most important frontiers collapse.

The future lay to the south. Muhammad died in 632, leaving behind a whirlwind prepared to move north, east, and west. The pummeling that Byzantine and Persian forces gave each other and the relative detachment of Syria, Palestine, and Egypt from Byzantine control gave the men of the desert their chance. Just as the northern barbarians had found their strength shadowing the empire they admired, so the Arabs of the desert marches had grown in strength and confidence and were prepared to seize an opportunity. If it was not divine providence that brought them to this moment, they seized it as though it were.

Defeated Theodore

In 634 the Arab armies invaded Syria and defeated Theodore, the emperor’s brother, in a string of battles. Heraclius raised a large army that attacked the Arabs near the Yarmuk River, a tributary of the Jordan, in the fall of 636. After a successful beginning, the larger Byzantine army was defeated and put to flight. Roman Syria was easily taken at that point. The Arabs capitalized on Persia’s disarray by quickly taking the whole of the frontier lands (including Mesopotamia and Armenia) and then Egypt not long afterward. Alexandria fell in 640 after a siege that lasted more than a year. At that time, Muhammad had been dead less than a decade.

What was left for ancient empire? The Balkans, the suburbs of Constantinople, most of Asia Minor, and the African outpost around Carthage that Justinian had seized at such cost. Italy remained, with as much cost as benefit, but the African base would support Constantinople for the sixty years remaining before the Arabs seized it at the turn of the eighth century. (Sicily remained Byzantine much longer: without it, the whole of Byzantine pretension might have fallen.) By the end of the seventh century, the economics of empire had caught up with Constantinople and the city population collapsed.

Heraclius died on February 11, 641, his empire fully and finally in tatters. His two sons failed to establish themselves, and it was his grandson Constans II who became emperor later that year at age eleven, at the onset of what would be a long and pointless reign. Irony alone would accompany him as he visited Rome in 663, the first emperor seen there in two centuries. He was assassinated in his bath in 668, and his successors forgot the west.

0 notes

Photo

Jerusalem was Heraclius’s last moment of glory

The trip to Jerusalem was Heraclius’s last moment of glory. He fell ill soon afterward; and in the field in the 630s he was represented by other generals, who saw his most important frontiers collapse.

The future lay to the south. Muhammad died in 632, leaving behind a whirlwind prepared to move north, east, and west. The pummeling that Byzantine and Persian forces gave each other and the relative detachment of Syria, Palestine, and Egypt from Byzantine control gave the men of the desert their chance. Just as the northern barbarians had found their strength shadowing the empire they admired, so the Arabs of the desert marches had grown in strength and confidence and were prepared to seize an opportunity. If it was not divine providence that brought them to this moment, they seized it as though it were.

Defeated Theodore

In 634 the Arab armies invaded Syria and defeated Theodore, the emperor’s brother, in a string of battles. Heraclius raised a large army that attacked the Arabs near the Yarmuk River, a tributary of the Jordan, in the fall of 636. After a successful beginning, the larger Byzantine army was defeated and put to flight. Roman Syria was easily taken at that point. The Arabs capitalized on Persia’s disarray by quickly taking the whole of the frontier lands (including Mesopotamia and Armenia) and then Egypt not long afterward. Alexandria fell in 640 after a siege that lasted more than a year. At that time, Muhammad had been dead less than a decade.

What was left for ancient empire? The Balkans, the suburbs of Constantinople, most of Asia Minor, and the African outpost around Carthage that Justinian had seized at such cost. Italy remained, with as much cost as benefit, but the African base would support Constantinople for the sixty years remaining before the Arabs seized it at the turn of the eighth century. (Sicily remained Byzantine much longer: without it, the whole of Byzantine pretension might have fallen.) By the end of the seventh century, the economics of empire had caught up with Constantinople and the city population collapsed.

Heraclius died on February 11, 641, his empire fully and finally in tatters. His two sons failed to establish themselves, and it was his grandson Constans II who became emperor later that year at age eleven, at the onset of what would be a long and pointless reign. Irony alone would accompany him as he visited Rome in 663, the first emperor seen there in two centuries. He was assassinated in his bath in 668, and his successors forgot the west.

0 notes

Text

Science Fiction New Releases: 15 June, 2019

The Four Horsemen. The Republic of Cinnabar Navy. The Imperium of Man. Tyler Barron’s Confederation. The Abh Empire. Black Jack Geary’s Alliance. Classic space navies of the past and present loom large in this week’s constellation of the newest releases in science fiction.

Crest of the Stars #1 – Hiroyuki Morioka

In the far-distant future, mankind has traversed the stars and settled distant worlds. But no matter how advanced the technology of the future becomes, it seems the spacefaring nations cannot entirely shed their human nature.

Jinto Lin finds this out the hard way when, as a child, his home world is conquered by the powerful Abh Empire: the self-proclaimed Kin of the Stars, and rulers of vast swaths of the known universe. As a newly-appointed member of the Abh’s imperial aristocracy, Jinto must learn to forge his own destiny in the wider universe while bearing burdens he never asked for, caught between his surface-dweller “Lander” heritage and the byzantine culture of the Abh, of which he is now nominally a member. A chance meeting with the brave-but-lonely Apprentice Starpilot Lafier aboard the Patrol Ship Goslauth will lead them both headfirst down a path of galaxy-spanning intrigue and warfare that will forever change the fate of all of humankind.

Earth Unleashed (Earthside #12) – Daniel Arenson

It begins. The final battle between man and machine.

Earth burns. The Dreamer, a cruel artificial intelligence, brutalizes our world. His robots reduce our cities to ash. His cyborgs march by the millions. Humanity is now an endangered species.

But we still fight!

A band of heroes undertakes a dangerous quest. Some call it a suicide mission. They fly to a computerized world, deep in space, where the Dreamer dwells.

There humanity will face an electric god. There we will fall . . . or rise higher than ever before.

The Eve of War (Ruins of the Galaxy #1) – Christopher Hopper

He’d never do this again.

But she was pretty.

And it was his job to follow orders, right?

Still, this kind of woman was trouble. The type that ended careers. That got Republic Marines killed.

All he needed to do was keep her close and get her to the top of the building. But his gut told him she wasn’t going to make it easy.

That victory cigar was a long day away.

The Feeding of Sorrows (Four Horsemen Tales #11) – Rob Howell

Once is an accident. Twice is a coincidence. Three times is enemy action.

When Zuul-led thugs attack members of the Queen Elizabeth’s Own Foresters leaving the Lyon’s Den, the battles on Cimaron 283133-6A and Peninnah become enemy action, not simply mercs fulfilling contracts. What the Foresters don’t realize is that these attacks have been planned for years as part of an even larger series of plots aided by members of the Mercenary Guild.

Unlikely allies appear, including a Peacemaker who doesn’t like being used, an electronic intelligence specialist with a past that’s heavily redacted, and the strangest recruit in the Foresters’ history, but will their aid be enough against foes who seek the unit’s complete and utter destruction? And more importantly—who is funding the intelligence specialist’s special toys?

Answers will be found as the Foresters battles across the stars and in alien jungles—but will the answers only bring more questions?

Only two things are certain. Alliances will shift. And sorrows will be fed.

The Others (Blood on the Stars #13) – Jay Allan

From the deepest darks of unknown space, evil comes…

Admiral Tyler Barron and the Confederation navy face a new threat, darker and deadlier than any that have come before.

The Confederation has just concluded its war with the Hegemony, but now that power, so long the hated enemy, is calling for help, for the Confederation to join it to face a deadly invasion, one likely to subjugate all humanity.

Barron must overcome his own resentments, and the resistance of the Senate, and find a way to lead his forces into battle once more. The odds are long, but the stakes couldn’t be higher, no less than a choice between survival and freedom…and slavery and death.

Barron and his people will find the strength, somehow, to face the invincible enemy, to find some way to fight, to overcome the darkness.

Or at least to survive to fight another day.

The Solar War (The Horus Heresy: Siege of Terra #1) – John Fench

After seven years of bitter war, the end has come at last for the conflict known infamously as the Horus Heresy. Terra now lies within the Warmaster’s sights, the Throneworld and the seat of his father’s rule. Horus’ desire is nothing less than the death of the Emperor of Mankind and the utter subjugation of the Imperium. He has become the ascendant vessel of Chaos, and amassed a terrible army with which to enact his will and vengeance. But the way to the Throne will be hard as the primarch Rogal Dorn, the Praetorian and protector of Terra, marshals the defences. First and foremost, Horus must challenge the might of the Sol System itself and the many fleets and bulwarks arrayed there. To gain even a foothold on Terran soil, he must first contend the Solar War. Thus the first stage of the greatest conflict in the history of all mankind begins.

READ IT BECAUSE: The final act of the long-running, bestselling series starts here, with a brutal and uncompromising look at the first stage of the Siege of Terra, the war to conquer the solar system. Armies will fall, heroes will rise and legends will be written…

To Clear Away the Shadows (RCN Series #13) – David Drake

The truce between Cinnabar and the Alliance is holding, and the Republic of Cinnabar Navy is able to explore regions of the galaxy without the explorers being swept up in great power conflict.

The Far Traveller is probing sponge space to open routes for Cinnabar traders—and for RCN warships if war breaks out again. But besides astrogation, the Far Traveller is to survey and catalog life forms on the worlds it touches.

Harry Harper has just been posted to the Traveller. He’s an RCN officer by convention, a scientist by training—and a member of one of leading aristocratic families on Cinnabar by birth.

Lieutenant Rick Grenville would rather serve on a warship in the heart of battle, but peace and the whim of the Navy Board have put him on an exploration vessel instead. He finds that the dangers on the fringes of civilization are just as great as those from missiles and gunfire that he expected to face.

As internal struggles cause the Alliance to relax its iron grip, regional forces are attempting to increase their own power—and they’re not fussy about the means they use.

Besides the biological answers that officials on Cinnabar expect the Far Traveller to find, the ship’s Director of Science, Doctor Veil, has her own agenda: to learn more about the Archaic Spacefarers who roamed the universe tens of thousands of years before humans reached the stars.

The crew of the Far Traveller is poised to clear more of the shadows away from the deep past than ever before in human history—if they survive.

Triumphant (Genesis Fleet #3) – Jack Campbell

The recently colonized world of Glenlyon has learned that they’re stronger when they stand with other star systems than they are on their own. But after helping their neighbor Kosatka against an invasion, Glenlyon has become a target. The aggressive star systems plan to neutralize Glenlyon before striking again.

An attack is launched against Glenlyon’s orbital facility with forces too powerful for fleet officer Rob Geary to counter using their sole remaining destroyer, Saber. Mele Darcy’s Marines must repel repeated assaults while their hacker tries to get into the enemy systems to give Saber a fighting chance.

To survive, Glenlyon needs more firepower, and the only source for that is their neighbor Kosatka or other star systems that have so far remained neutral. But Kosatka is still battling the remnants of the invasion forces on its own world, and if it sends its only remaining warship to help will be left undefended against another invasion. While Carmen Ochoa fights for the freedom of Kosatka, Lochan Nakamura must survive assassins as he tries to convince other worlds to join a seemingly hopeless struggle.

As star systems founded by people seeking freedom and autonomy, will Kosatka, Glenlyon and others be able to overcome deep suspicions of surrendering any authority to others? Will the free star systems stand together in a new Alliance, or fall alone?

We Dare – edited by Chris Kennedy and Jamie Ibson

All I need is an edge! As long as humans have competed with each other (for food, profit, and love), people have looked for ways to get an edge on the competition—how to be better, faster, and smarter than the opposition. With better science and technology, many things are now possible, and there will be many more in the future! Gene splicing will augment your abilities. Implants will make you smarter. Cybernetic systems will make you stronger.

Edited by Jamie Ibson and Chris Kennedy, “We Dare” is a collection of 15 all-new stories that explores the use of augmented humanity in the near future. From getting a new personality loaded with the skills you need for a mission to nanobots that keep you from being killed to creating an indestructible tank, anything is possible!

But just because we can augment humanity doesn’t necessarily mean we should, and there are cautionary tales inside as well. Along with the “good” that might be possible, there is also the potential for augmentation to be used for more…nefarious���ends. Will augmentation make better criminals? What happens when someone with implants has their mind taken over?

One thing is certain, though—people will dare to augment themselves to get an edge. Our authors dared to write these stories of augmented humanity; will you now dare to read them?

Science Fiction New Releases: 15 June, 2019 published first on https://sixchexus.weebly.com/

0 notes

Photo

Jerusalem was Heraclius’s last moment of glory

The trip to Jerusalem was Heraclius’s last moment of glory. He fell ill soon afterward; and in the field in the 630s he was represented by other generals, who saw his most important frontiers collapse.

The future lay to the south. Muhammad died in 632, leaving behind a whirlwind prepared to move north, east, and west. The pummeling that Byzantine and Persian forces gave each other and the relative detachment of Syria, Palestine, and Egypt from Byzantine control gave the men of the desert their chance. Just as the northern barbarians had found their strength shadowing the empire they admired, so the Arabs of the desert marches had grown in strength and confidence and were prepared to seize an opportunity. If it was not divine providence that brought them to this moment, they seized it as though it were.

Defeated Theodore

In 634 the Arab armies invaded Syria and defeated Theodore, the emperor’s brother, in a string of battles. Heraclius raised a large army that attacked the Arabs near the Yarmuk River, a tributary of the Jordan, in the fall of 636. After a successful beginning, the larger Byzantine army was defeated and put to flight. Roman Syria was easily taken at that point. The Arabs capitalized on Persia’s disarray by quickly taking the whole of the frontier lands (including Mesopotamia and Armenia) and then Egypt not long afterward. Alexandria fell in 640 after a siege that lasted more than a year. At that time, Muhammad had been dead less than a decade.

What was left for ancient empire? The Balkans, the suburbs of Constantinople, most of Asia Minor, and the African outpost around Carthage that Justinian had seized at such cost. Italy remained, with as much cost as benefit, but the African base would support Constantinople for the sixty years remaining before the Arabs seized it at the turn of the eighth century. (Sicily remained Byzantine much longer: without it, the whole of Byzantine pretension might have fallen.) By the end of the seventh century, the economics of empire had caught up with Constantinople and the city population collapsed.

Heraclius died on February 11, 641, his empire fully and finally in tatters. His two sons failed to establish themselves, and it was his grandson Constans II who became emperor later that year at age eleven, at the onset of what would be a long and pointless reign. Irony alone would accompany him as he visited Rome in 663, the first emperor seen there in two centuries. He was assassinated in his bath in 668, and his successors forgot the west.

0 notes