#Terusuke

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

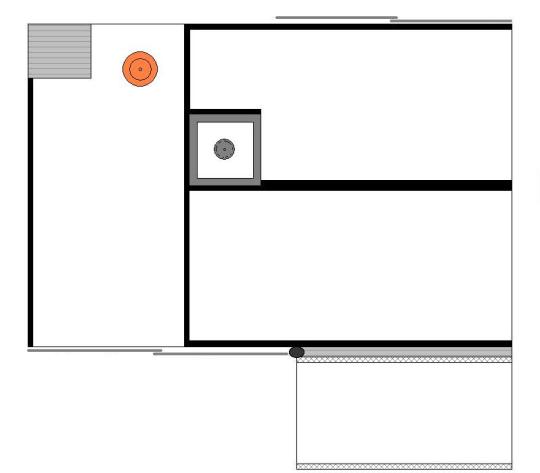

Nampō Roku, Book 7 (80): Concerning Lord Hino’s¹ Use of Kayari [蚊遣]² in the Roji.

80) Concerning [his connection with] Rikyū-koji, Hino Terusuke had become his disciple, and [they] frequently visited [each other]³.

On an evening in the summer, [Terusuke] set up a kayari-bi [蚊遣火] in his garden, in the shade under the trees⁴. When [Ri]kyū saw this [he said] “indeed, isn’t that most tasteful!” -- he was deeply moved⁵.

Since then [it has become the practice that], in a secluded place in the roji [and] near the koshi-kake, in a suitable place in the shade under the trees, the kayari should be set to smoldering [in order to keep the area free of mosquitoes]⁶.

_________________________

◎ The toku-shu shahon version of this entry agrees with the Enkaku-ji manuscript. However, according to both Tanaka Senshō and Shibayama Fugen -- and rather curiously -- the genpon text substitutes the name of Lord Asukai [飛鳥井殿] (perhaps Asukai Masakata [飛鳥井雅賢; 1585 ~ 1626], who held the lower grade of the junior fourth rank, and was Sakon-e no shosho [左近衛少将], equivalent to lieutenant-general of the Sakon [Left] Guards unit) for that of Hino Terusuke [日野輝資; 1555 ~ 1623]. This is strange because, while Lord Hino is known to have been a disciple of Rikyū (he is mentioned several times in the Nampō Roku in this capacity), a connection between Rikyū and Lord Asukai is less well documented*. ___________ *In 1609, Asakai Masakata was exiled to Naka-no-shima [中之島] in Oki [隠岐] (a group of islands northwest of the border between Tottori and Shimane Prefectures) on account of having seduced one of the emperor’s ladies-in-waiting. Masakata died in exile later in 1626.

Masakata is not recorded to have had any interest in chanoyu, and there does not appear any other reason to associate Masakata with Rikyū.

The Asakai family was established during the Heian period, but they were always more closely associated with waka [和歌] and kemari [蹴鞠] than with other cultural activities. (Kemari, which appeared in something resembling its present form toward the end of the Heian period, is usually described as a kind of football; but the object of the game was to keep the ball in the air, and prevent it from touching the ground: after kicking the ball, that player had to intone an original waka before the ball was kicked again. As can be seen below, the participants usually wore casual court dress, as well as their lacquered caps of estate.)

Members of the Asakai family were the instructors of kemari to the Ashikaga shōgun Yoshimasa and Yoshinao, and their courts. During the fifteenth century the Asakai also founded the Niraku school [二楽流] of calligraphy. Their fortunes seem to have declined in tandem with those of the Ashikaga house, so that they were remembered more for the scandal involving Masakata, than for other accomplishments during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

¹Hino Terusuke [日野輝資; 1555 ~ 1623] was a scion of the hereditary court nobility (kuge [公卿]), who served in various governmental posts, ultimately being appointed Gon-dainagon [権大納言] (Supernumerary Grand Counselor of State) in 1597, at which time he was elevated to the senior grade of the Second Rank. He was thus the highest ranking among Rikyū's noble disciples.

Terusuke retired from government service in the Fifth Month of Keichō 12 [慶長十二年] (1607) and became nyūdō, taking the name Yuishin-in [唯心院]. Nevertheless, it seems that he remained a counselor to both Tokugawa Ieyasu and his son Hidetada until his death.

²Kayari [蚊遣] means mosquito repellent, and usually referred to burning pine-needles or dried mugwort (or an incense compounded from the latter) for this purpose. The practice had been employed at the Imperial Court since ancient times, but this occasion appears to have been the first time that it was used in the roji -- to rid the roji and koshi-kake of mosquitos during a chakai.

³Rikyū-koji ha, Hino Terusuke no montei ni natte, tsune ni mairare-keri [利休居士ハ、日野輝資ノ門弟ニ成テ、常ニ參ラレケリ].

Rikyū-koji ha [利休居士は] means concerning Rikyū-koji.

Koji [居士] was the “non-title” (meaning a Buddhist layman, or lay believer -- that is, a follower who had not formally taken the tonsure) that was bestowed on Rikyū in early 1586, so he could enter the Imperial Palace and assist* Hideyoshi’s service of tea to the Emperor Ōgimachi [正親町天皇; 1517 ~ 1593 -- his reign extended from the 27th day of the Tenth Month of Kōji 3 [弘治三年], 1557, to the 7th day of the Eleventh Month of Tenshō 14 [天正十四年], 1586] in Hideyoshi’s golden tearoom (which was set up on the deep veranda of one of the halls within the palace compound).

Hino Terusuke no montei ni natte [日野輝資の門弟になって]: this phrase is grammatically irregular; but the meaning seems to be that Hino Terusuke was one of Rikyū’s disciples†.

Tsune ni mairare-keri [常に參られけり] means that (he) frequently desired to visit‡ -- while this is usually understood to mean that Terusuke often visited Rikyū, the context of this entry implies that the visits between the two were reciprocal.

Here, and throughout the entire passage, he toku-shu shahon agrees exactly with the Enkaku-ji text**. ___________ *Despite occasional assertions to the contrary that are found in the popular tea histories, Rikyū’s job on this occasion was primarily to grind the tea, help prepare the utensils, and take care of various things that had to be done in the preparation area (such as emptying the koboshi, and returning it after cleaning, so Hideyoshi could replace it on the daisu), and sit in the vicinity of the sadō-guchi, ready to offer any advice that Hideyoshi might have needed. The surviving accounts suggest that the daisu-temae that Hideyoshi employed on this occasion used a bon-chaire and dai-temmoku, and everything used was either made of gold, or made of wood covered with gold (the temmoku was made in that way, since a gilded ceramic bowl would have been too heavy, and potentially could have been too hot to hold comfortably).

On this occasion, Rikyū did not meet the Emperor or serve him tea while Hideyoshi sat and chatted with the Emperor (the way some popular versions of the story suggest). Indeed, the Emperor would have been entirely unaware of Rikyū’s presence.

†Linguistically, the construction of this phrase seems to suggest that Rikyū became Lord Hino’s disciple, which is nonsense.

‡The suffix -keri [けり] might be interpreted to suggest that this was something that happened in the past, something that had already ceased to occur by the time that this text was written down.

And, indeed, as Lord Hino rose higher and higher in the government, he would have had correspondingly less time to indulge in things like chanoyu.

**As does the genpon text -- except that, as noted above, the genpon version inserts the name Asukai-dono [飛鳥井殿], Lord Asukai, in place of Hino Terusuke [日野輝資]: Rikyū-koji ha, Asukai-dono no montei ni natte, tsune ni mairare-keri [利休居士ハ、飛鳥井殿ノ門弟ニ成テ、常ニ參ラレケリ].

There does not seem to be any historical justification that might account for this change in the text, however, so it is difficult to imagine how the substitution came to be made by the editors of the genpon edition. Tanaka Senshō, however, argues that the reason for the name change was because of the Asakai family’s traditional connection with kemari (that was mentioned in the sub-note below my introduction). Because the Asakai were the national experts, the men of their family would have had to practice kemari out-of-doors throughout the year. During the summer months, because of the discomfort caused by mosquitoes (not only while playing, but also while resting between innings in the shade of the trees in the garden), they began to burn mosquito repellent in the garden to make their long practice sessions more endurable. Nevertheless, this does not give us any clues as to why Rikyū would have been visiting them, or why he would have been so deeply impressed by the idea of burning kayari in the garden.

⁴Natsu yū-gata, o-niwa no ko-kage ni kayari-bi wo tateraretari wo [夏ノ夕方、御庭ノ木陰ニ蚊遣火ヲタテラレタルヲ].

Natsu yū-gata [夏の夕方] means on an evening during the summer.

O-niwa [御庭]: the honorific o- [御] was probably used because Lord Hino was a member of the kuge [公卿], the hereditary court nobility, so the use of the polite form would indicate unambiguously that this garden was in his residence.

O-niwa no ko-kage ni kayari-bi wo tateraretari wo [御庭の木陰に蚊遣火を立てられたるを] means that in (Lord Hino’s) garden, in the shade of the trees*, a kayari-bi [蚊遣火]† was set up.

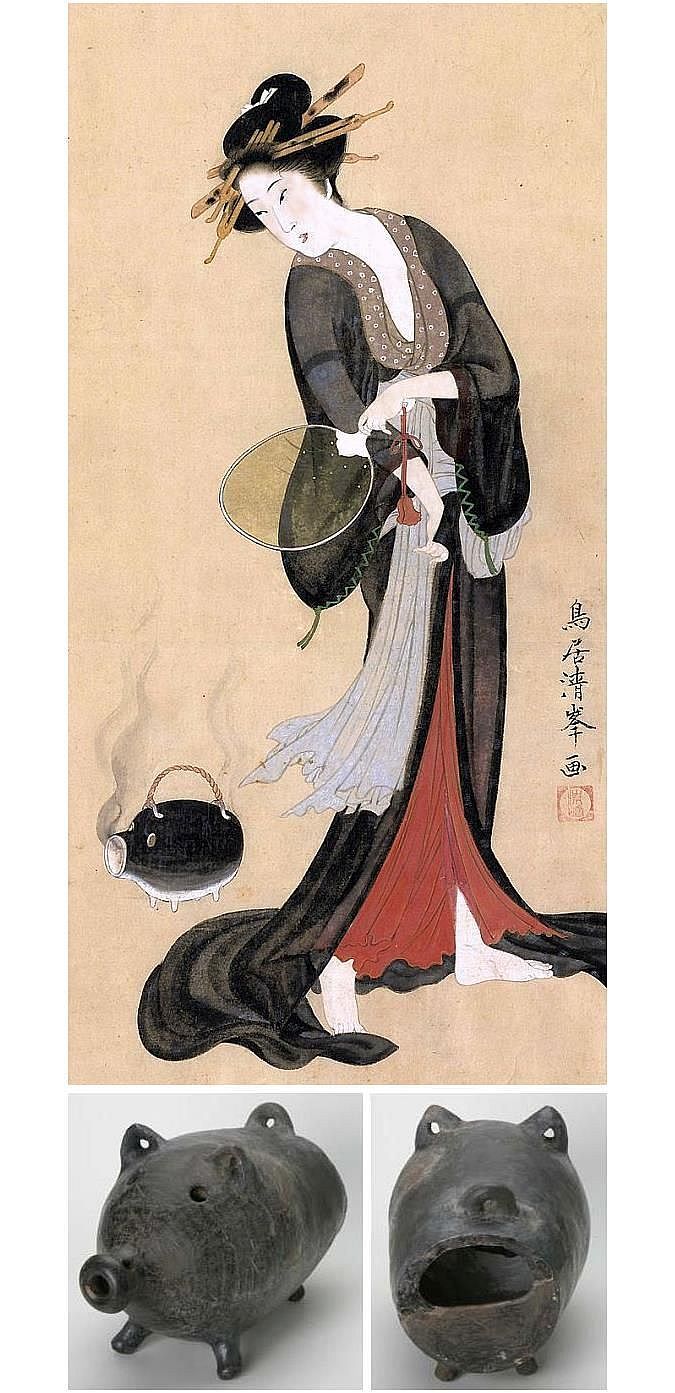

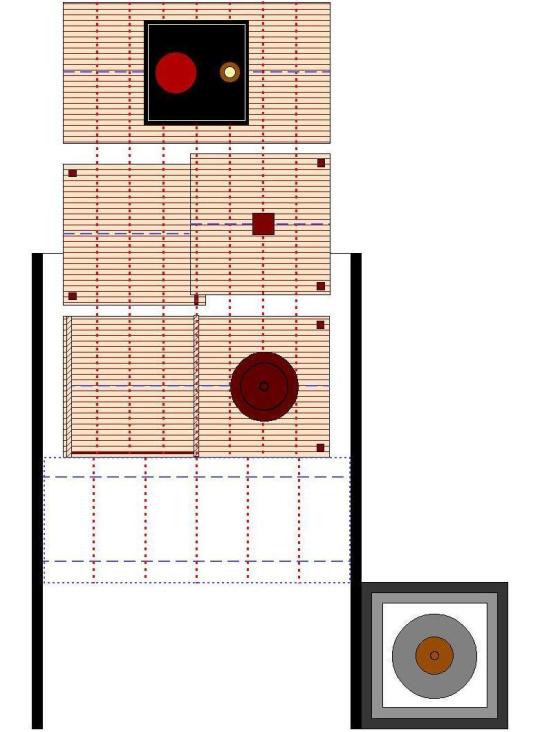

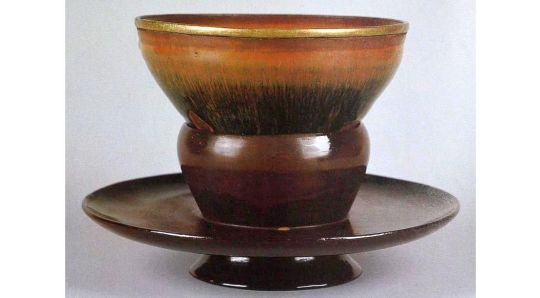

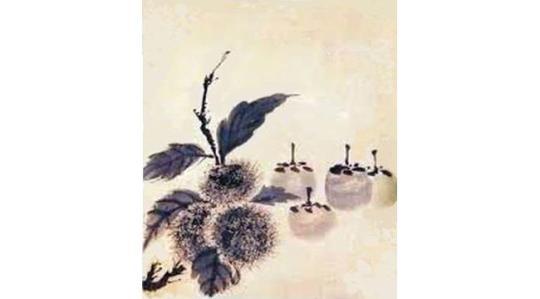

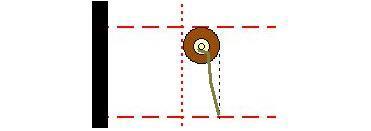

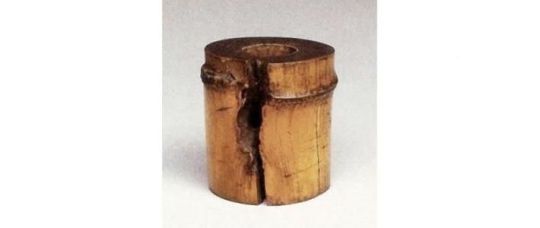

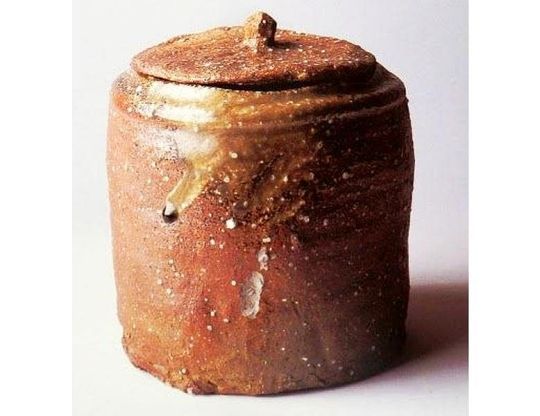

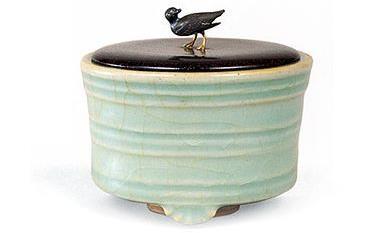

A kayari-bi was an openwork (usually ceramic) brazier (an Edo-period example of a kayari-bi that was made to be set on the floor of a room is shown above) in which either dried pine-needles, or stalks of dried mugwort (Artemisia princeps, and possibly other species)‡, were set to smoldering, since the smoke from these plants had mosquito-repelling properties.

However, by the point in the Edo period when this text was written, mosquito-repellent incense sticks (katori-senkō [蚊取線香]**), made from crushed mugwort mixed with charcoal powder, also seem to have been invented, so this entry could be referring to either form of kayari.

The above painting, titled Kayari-bijin [蚊遣美人] (“a Beauty with a kayari-bi”), by Torii Kiyomine [鳥居清峯; 1836 ~ 1867] shows how a handle was attached to another Edo-period example of a katori-bi (an antique example is shown below the painting -- the pine-needles, stalks of mugwort, or a coil of mosquito incense, would be placed inside through the large hole in the back side of the kayari-bi). The handle was used to carry the kayari-bi from place to place, as needed, to keep the mosquitos away††. __________ *Since the gathering during which this kayari-bi was set up in the roji was held in the evening, the shade from the trees is probably less important to the story than the fact that the kayari-bi was placed somewhere where it would not be seen. The purpose was, of course, to chase away the mosquitoes and other night insects from the vicinity of the koshi-kake and roji.

†With respect to this use of a kayari-bi in the roji, Tanaka Senshō comments:

Kayari de naku, eji-kago tote, niwa no tsūro ni kō wo taku-koto ha ko-rai aru. Ka no dō no tsuru ya, kamo nado wo tei-jō ni oite kō wo taku-koto ha, ko-rai okonawareta-koto de aru. Kono-koto kara, kayari wo omoi-tsuita no de arau ka. Roji ni kayari wo tateta-koto ha, mukashi to shite omoshiroi shu-mi de aru. Ima-doki ha, ryōri-ya no teien ni, katori-senkō ga takarete-iru ga, kore ha fūryū to ha ienu. Yahari, eji-kago nado suete, mukashi-fū no kayari-bi no kata ga omoshiroi to omou

[蚊遣でなく、衛士籠とて、庭の通路に香を炷く事は古来ある。彼の銅の鶴や、鴨抔を庭上に置いて香を炷く事は、古来行われた事である。此事から、蚊遣を思ひ付いたのであらうか。露地に蚊遣を立てた事は、昔として面白い趣味である。今時は、料理屋の庭園に、蚊取線香が炷かれているが、是は風流とは云ヘぬ。やはり、衛士籠抔据ゑて、昔風の蚊遣り火の方が面白いと思ふ].

“In the absence of a kayari, since ancient times it has been the practice that even [something like] an eji-kago [衛士籠] might be set up beside the garden path and used for burning incense. As for placing bronze cranes and ducks and the like in the garden for burning incense [to perfume the air], this has been done since ancient times. Perhaps this was how they came up with the idea of [burning] kayari? Setting up the kayari in the roji must have been a interesting way to amuse [oneself] in bygone days. Nowadays, katori-senkō is burned in the gardens of restaurants, but [I don’t] think this can be called tasteful. I think it would be much more interesting to set up an eji-kago and make use of this old-fashioned way of repelling mosquitos!”

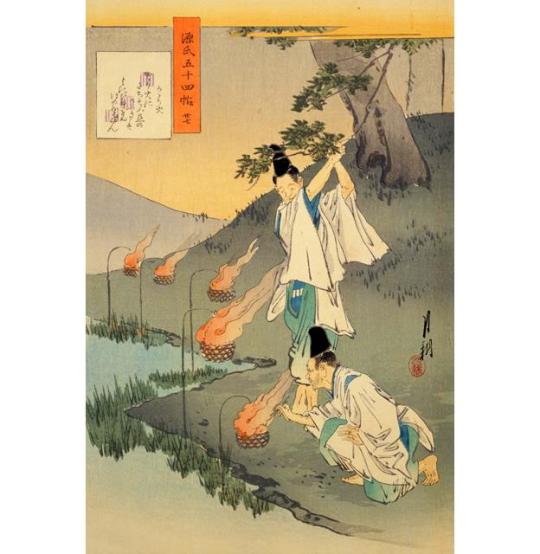

An eji-kago [衛士籠] (the name means a sentry’s/gatekeeper’s basket -- by the light of which the guard was able to identify people approaching the gate for admittance) was (originally) an iron basket, suspended from or on some sort of stand or tripod (as can be seen below), in which wood was kindled for illumination. This arrangement was also referred to as a kagari-bi [篝火] -- as in the following Edo period illustration for chapter 54 of the Genji monogatari [源氏物語] (which sets the scene on a veranda whose garden is illuminated in this way). In the picture we see a line of kagari-bi (often translated as “flares”) set up along the bank of the garden stream, with the fires attended by underlings.

Here, it is unclear whether Tanaka believed that the smoke from the fire in the kagari-bi would be sufficient to drive the mosquitoes away, or whether he is using the word eji-kago to refer to a similar sort of arrangement -- albeit one in which pine needles or mugwort, or some other special material, would be burned in similar manner to produce the desired fumigatory or mosquito-repelling effect.

The reference that he makes to bronze cranes and ducks installed in the garden is either addressing the matter of the supports from which the containers of smoldering incense (usually crushed jin-kō [沈香] or kyara [伽羅], or blends based on these) were suspended (the bowls were taken in when incense was not being burned, leaving the bronze statues standing in the garden as decorative objects in their own right), or to bronze censors cast in these shapes (such as the one shown below) that were set out in the garden to perfume the air.

It might be added that most of the oldest tsuri-bune [釣り船] imported from Mogul India and China were originally made as hanging incense burners.

‡This plant is called yomogi [よもぎ = 蓬) in Japanese, and ssuk [쑥] in Korea. In addition to its mosquito-repellent qualities (in Korea, the plant was traditionally cultivated along the edge of the veranda, since even when living the essential oils volatilize into the air, deterring mosquitos; and in the autumn the stalks were cut down to the ground, and then suspended upside-down under the eves to dry for use as a kayari (fumigant) the next year). Mugwort is also used in both country’s cuisine; in Korea, it is also used in certain varieties of traditional sweets (though strongly-flavored sweets of this kind fell out of favor in Japan early in the 20th century -- when the preference shifted to tastes that would best appeal to young women). Mugwort is also used in the traditional medicine of both countries (and the mugwort-flavored sweets were just one example).

**While originally produced as straight incense sticks, the coil version of katori-senkō seems to have appeared during the Edo period as well -- allowing for a longer-burning piece of incense that was not spatially limited as a linear stick would have been.

††The fact that the roji is watered so frequently means that mosquitoes are an inevitable menace from late spring to deep autumn, where they usually attack the participants at the exposed strip of skin between the edge of the tabi and the hem of one’s kimono -- a sensitive area where their bite is horribly annoying (especially in Japan, where the custom is to avoid touching the feet and ankles as much as possible, so the brief relief of scratching is completely out of the question).

⁵Kyū mite, sasuga ni fūryū-no-koto kana to kanshin-shi [休見テ、サスガニ風流ノ���トかナト感心シ].

Kyū mite [休見て] means (and) when Rikyū saw this...

Sasuga ni fūryū* no koto kana [流石に風流のことかな] means “indeed, isn’t that most tasteful!” These words were supposed to have been murmured by Rikyū when he noticed the faint tendrils of smoke trailing through the plantings†.

To kanshin-shi [と感心し] means as he was deeply moved (by the sight). ___________ *The expression fūryū [風流], especially as it is being used here, did not enter the lexicon of the chajin until the Edo period (indeed, fūryū was, culturally, a very important and popular way of describing moving, tasteful, and “artistic” experiences from the second half of the seventeenth century onward). This helps us understand that this text, while possibly based on a real incident -- the first time that a kayari-bi was used during a tea gathering to keep the roji and koshi-kake free of insects during night gatherings in the summer -- could not have been written until the late seventeenth century.

†Perhaps it initially reminded him of the smoke of the burning pine needles that trailed through the pine trees during the fusube-chanoyu [ 燻べ 茶の湯] that Rikyū had created for Hideyoshi as a way to enjoy chanoyu even in the pine barrens at Daizen-ji and Hakozaki, during the Kyūshū campaign of 1586~7.

See the post entitled Nampō Roku, Book 7 (66): Fusube-chanoyu [フスベ茶湯] – a Tea Gathering Held Out-of-doors for further details. The URL is:

https://chanoyu-to-wa.tumblr.com/post/726511147567775744/namp%C5%8D-roku-book-7-66-fusube-chanoyu-%E3%83%95%E3%82%B9%E3%83%99%E8%8C%B6%E6%B9%AF

⁶Sono ato, roji・koshikake no atari, ko-kage no shikaru-beki-tokoro ni, kayari wo takare-shi-koto ari [其後、露地・腰カケノアタリ、木陰ノシカルベキ所ニ、カヤリヲタカレシコトアリ].

Sono ato [その後] means after that, later on, afterward.

The implication is that this gathering, hosted by Hino Terusuke, was the first occasion on which a kayari-bi had been used, secreted under the trees to clear the area of noxious insects during the chakai. The realization of how useful this would be is why Rikyū is made to be so impressed and moved -- because he had never though of doing something like that himself*.

Roji・koshikake no atari [露地腰掛の當り] means in an out-of-the-way place in the roji and koshi-kake; on the edge of the roji and koshi-kake.

Ko-kage no shikaru-beki-tokoro ni [木陰の然るべき所に]: ko-kage [木陰], as above, means in the shade of the trees (in other words, in an inobvious place under the trees that were planted to obscure the fences that enclose the roji from view); shikaru-beki-tokoro ni [然るべき所に] means in a suitable place, in the right place.

Kayari wo takare-shi-koto ari [蚊遣を薫かれしことあり] means the fumigant† should be set to smoldering‡ (in the shade under the trees). __________ *It appears that the burning of kayari originated with, and was largely restricted to, the Imperial Court -- with kayari-bi set up in obscure corners of the various ceremonial and audience halls, to eliminate mosquitoes that would have disrupted the proceedings (since mosquitoes remain active even during the daytime in such large, and dark, spaces, and court ceremonials and audiences could carry on for hours without a break).

†Kayari [蚊遣] -- without the -bi [火] -- means a fumigant or mosquito repellent; however, this short form was also used informally as a way to refer to the kayari-bi, as a self-contained unit, so either interpretation would be correct.

‡This particular verb, takareru [薫かれる], is used specifically to mean to “burn” something like incense -- not with an active flame, but so that it smolders slowly.

==============================================

◎ If these translations are valuable to you, please consider donating to support this work. Donations from the readers are the only source of income for the translator. Please use the following link:

https://PayPal.Me/chanoyutowa

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

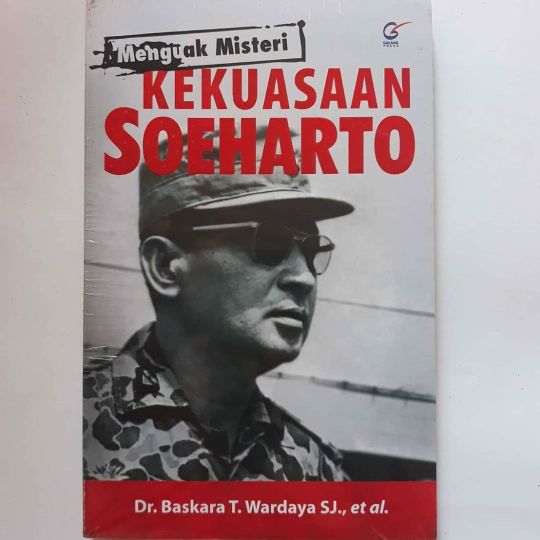

Menguak Misteri Kekuasaan Soeharto Penulis : Baskara T. Wardaya dkk Penerbit : Galang press Tebal : 297 hlm | Bookpaper Dimensi: 14x20 cm | Soft Cover Harga Normal: Rp38.000 Diskon 10% : Rp34.200 Selama lebih dari tiga dekade (1966-1998) Soeharto dan rezim Orde Baru-nya menguasai Indonesia. Pertanyaannya, mengapa dia bisa berkuasa begitu lama? Adakah rahasia atau misteri-misteri tertentu dibalik kekuasaan yang pnjang itu? Mengapa pula dia dan rezimnya pada tahun 1998 bisa lengser beitu cepat, hampir secepat balon terusuk jarum? Dengan menggunakan pendekatan multidimensional, buku ini bermaksud menguak misteri di balik kekuasaan mantan orang nomor satu Republik Indonesia itu. Tujuannya bukan untuk mengorek luka lama, melainkan untuk belajar bersama dari periode yang telah menjadi bagian tak terpisahkan dari bangsa ini. Kita tahu, bangsa yang besar adalah bangsa yag tidak takut untuk belajar dari lembar-lembar sejarahnya sendiri, betapapun hitam atau putih lembar-lembar tersebut. Semua itu dimaksudkan untuk membantu membangun kembali Indonesia sebagai negeri yang tidak hanya elok alamnya, melainkan juga penuh keadilan dan nilai-nilai kemanusiaan. #buku #bukubacaan #tokobuku #bukusejarah #bukupolitik #bukumurah #bukudiskon https://www.instagram.com/p/B7n9gJYAe2T/?igshid=co1wa8d1huu4

0 notes

Text

Sesak memang,dipertemukan disaat yang tidak diinginkan.

- hari ini aku bertemu denganmu lagi,yang pasti aku lihat dengan seorang wanita. Entah itu siapa,aku tetap sesak melihatnya. Seperti terusuk pedang tetapi tidak terlepas lagi,dan mengkarat.

0 notes

Text

Nampō Roku, Book 2 (4): (1586) Tenth Month, Fifth Day, Evening; Fu-ji [不時].

4) Tenth Month, Fifth Day, Evening¹; fu-ji [不時]².

◦ 4.5-mat [room]³.

◦ [Guests:] Amano Hikosuke [天野彥右]⁴, Ueda Hayato [上田準人]⁵.

Sho [初]⁶.

﹆ From Lord Hino [I received] a chrysanthemum from today's Court Banquet, to which was tied a tanzaku. This was arranged in a basket and hung up in the toko just as it was⁷.

◦ Kama ・ unryū [suspended over the ro on a bamboo] jizai [釜・雲龍 自在]⁸.

◦ On the fukuro-dana [袋棚]⁹:

◦ kōgō ・ Chōjirō kaki [香合・長二郎 カキ]¹⁰;

◦ habōki [羽箒]¹¹;

◦ mizusashi ・ Shigaraki [水サシ・シカラキ]¹².

Su [ス]

◦ The charcoal [was brought out] in a na-kago [菜籠]¹³.

▵ Charcoal-roasted hoshi-sakana [干肴]¹⁴, [accompanied by] two rounds of sake¹⁵.

▵ Mizu-kuri [水栗]¹⁶.

Go [後]¹⁷.

◦ The toko was left just as it was.

◦ On the fukuro-dana:

﹆ chaire ・ nasubi [茶入・ナスヒ]¹⁸, temmoku [天目]¹⁹, these two things, on a naka-bon [中盆]²⁰;

◦ hishaku [ヒシヤク];

◦ futaoki ・ in [蓋置・印]²¹;

◦ mizusashi ・ the same as before.

Su [ス]

◦ Kae-chawan ・ e [カヘ茶碗・繪]²²;

◦ chashaku ・ ori-tame [茶杓・折タメ]²³;

◦ koboshi ・ Bizen [コホシ・備前]²⁴.

_________________________

¹Jū-gatsu itsuka, yū [十月五日、夕].

The date was November 14, 1586 in the Gregorian calendar.

Yū [夕] means evening, dusk. As this was an impromptu gathering (apparently given to honor the chrysanthemum that Rikyū received from Hino Terusuke [日野輝資] as a souvenir of the Imperial Court Banquet that was held earlier that day), it seems likely that Rikyū invited the two guests to his home as they were leaving Hideyoshi’s audience chamber.

²Fu-ji [不時].

Fu-ji [不時] means unplanned, impromptu. Due to its having been completely unscheduled, the refreshments are minimal, with the host making use of the kinds of things that would likely be on hand to serve his guests.

³Yojō-han [四疊半].

This was the 4.5-mat room in Rikyū’s residence.

⁴Amano Hikosuke [天野彥右].

Though he is also mentioned as a guest in the Rikyū Hyakkai Ki [利休百會記], Amano Hikosuke has not been identified with any certainty.

⁵Ueda Hayato [上田準人].

This seems to refer to the bushō [武将] (military man) Tsuda Hayato [津田準人; ? ~ 1593]. It appears that Rikyū confused him, or at least his surname, with Ueda Satarō [上田左太郎].

Tsuda Hayato was a relative of Oda Nobunaga. Originally he served as a member of Nobunaga's cavalry (he held the position of sa-ma no suke [左馬允], third officer of the cavalry's left division), eventually rising to be the protector (or guardian) of Nobunaga's puppet-shōgun Ashikaga Yoshiaki [足利義昭; 1537 ~ 97]*. After Nobunaga's death, he served Hideyoshi in various capacities.

Tsuda Hayato was also actively involved with chanoyu. __________ *Yoshiaki was the fifteenth and last shōgun of the Ashikaga family. He was essentially deposed by Nobunaga in 1573, by being driven out of Kyōto, though he never officially relinquished his title. Thereafter he shaved his head and took the Buddhist name Shōzan Dōkyū [昌山道休].

Some time after Nobunaga's death, Hideyoshi invited Yoshiaki to return to the throne -- on the condition that he adopt Hideyoshi as his heir (so Hideyoshi could become the sixteenth Ashikaga shōgun), but Yoshiaki refused.

⁶Sho [初].

The details of the sho-za [初座] begin here.

⁷Hino-dono yori kyō [no] gyoen no kiku to te, o-tanzaku musubite dasare sōrō wo, kago ni te toko kakeoki-sōrō sono mama [日野殿ヨリ今日御宴ノ菊トテ、御短尺ムスヒテ被下候ヲ、籠ニテ床ニカケ置候其儘].

Rikyū received a chrysanthemum (with a tanzaku* tied to it) as a gift from Lord Hino†. In order to display it so that the guests could also read the poem without difficulty, Rikyū decided to arrange the flower in a hanging basket hanaire.

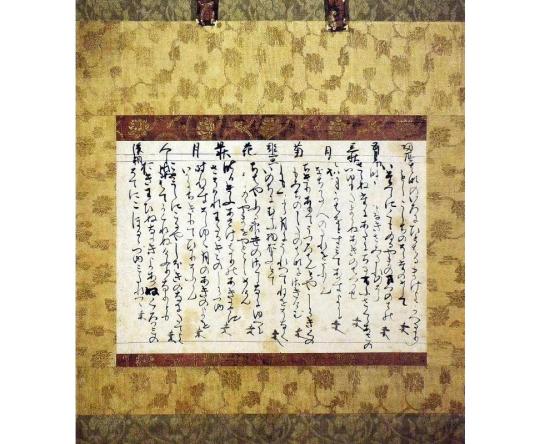

Rikyū's Katsura-kawa kago [桂川籠], which he used as a kake-hanaire, is shown above.

Kakeoki-sōrō sono mama [カケ置候其儘]: Rikyū just put the chrysanthemum in the hanging basket, without manipulating it in any way: he was not “arranging” the flower; he was simply displaying it as it was received from Lord Hino. ___________ *At court banquets, it was the custom for the high noblemen to compose congratulatory poems, which were written on tanzaku (a piece of paper 2-sun wide and 1-shaku 2-sun long, that had a hole in the center near the upper edge, by means of which they were tied to a seasonally auspicious floral offering -- in this case, a chrysanthemum -- and so presented to the Emperor; the flowers were arranged in front of his seat, and after the conclusion of the banquet the authors were apparently allowed to reclaim their flower and poem as a souvenir).

†Hino dono [日野殿] refers to Lord Hino Terusuke [日野輝資; 1555 ~ 1623], a kuge [公家] (a court noble -- a hereditary nobleman, rather than someone who had been elevated to the rank of courtier from the military caste), who was the Gon-dainagon [権大納言] or (supernumerary) Chief Counselor of State (senior grade of the Second Rank).

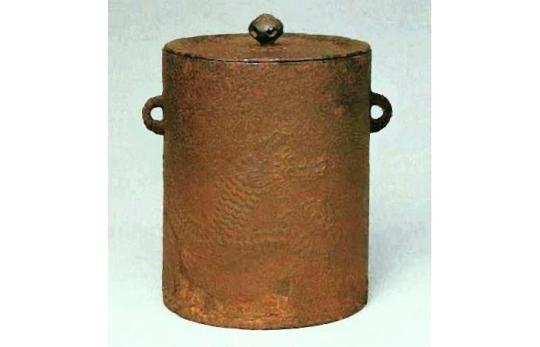

⁸Kama ・ unryū jizai [釜・雲龍 自在].

This was the second small unryū-gama [小雲龍釜] with matsu-kasa kantsuki [松笠鐶付] (shown below) and an iron lid, that Rikyū had ordered from Yoshirō after presenting the original kama (along with the large Temmyō kimen-buro) to Hideyoshi, for use in the Yamazato-maru tearoom in the boathouse of Ōsaka castle.

This small kama* was suspended over the ro on Rikyū’s abura-dake jizai [油竹自在]†, using his bronze kan [鐶] and tsuru [弦] (both of which are shown below).

___________ *Rikyū used the small unryū-gama because it would boil quickly. This was an impromptu chakai, and using this kama would allow Rikyū to prepare fresh water for the tea (rather than using water that had been boiling all day, or else changing the water in the large ro-gama and then waiting for it to come to a boil -- with nothing to distract the guests, since preparing a full kaiseki without prior notice would have been impossible).

†Abura-dake [油竹], which means “oily bamboo” (oil-stained bamboo) is usually called susu-dake [煤竹] (smoky-bamboo; smoke-stained bamboo) today. Both names refer to the 1-sun diameter bamboo poles taken from the underside of a farmhouse kitchen when the building was repaired or rebuilt, that have been stained by exposure to years of oil-filled cooking smoke. As a result, the bamboo becomes a dark brown-purple in color (though the color is mottled, rather than being uniform as in the case of artificially dyed bamboo).

⁹Fukuro-dana ni [袋棚ニ].

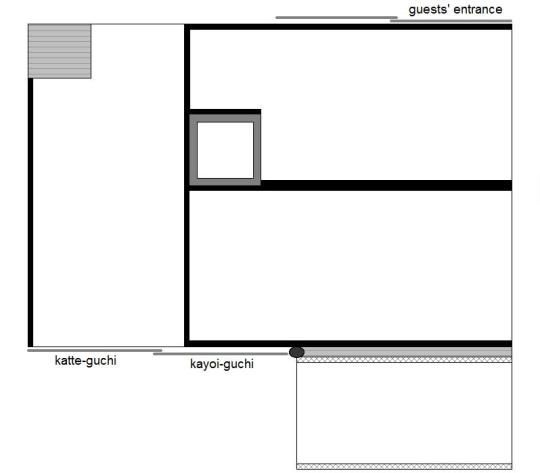

This refers to the fukuro-dana that was created by Jōō (shown below), based on the similar tana that was used by the Shino family at their incense and tea gatherings.

The Shino-dana [志野棚] has a pair of hinged doors, with a locking mechanism (to keep the host’s collection of kyara [伽羅] incense wood, that was stored in the ji-fukuro, safe); Jōō replaced the pair of locking doors with a single lift-out door -- and he also changed the procedures so that the guests were encouraged to open the ji-fukuro to inspect its contents each time they entered the tearoom (the shōkyaku was responsible for opening the door, while the last guest was charged with closing it again before the host entered for the temae).

Jōō’s famous Daikoku-an poem refers to this fukuro-dana.

◎ While Jōō originally taught that the fukuro-dana should be placed on the right side of the mat (so that its right edge sat on top of the right heri of the utensil-mat), after Rikyū entered Hideyoshi’s service (if not before) he began to center the fukuro-dana on the utensil mat (just as is done with all of the other oki-dana [置棚] during the ro season).

◎ At the beginning of the sho-za, the habōki and kōgō were arranged together on the naka-dana (the shelf above the mizusashi), with the mizusashi below.

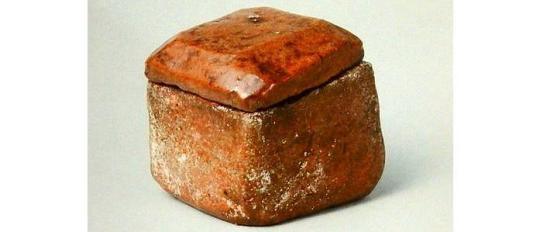

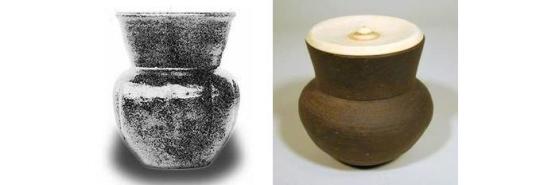

¹⁰Kōgō・ Chōjirō kaki [香合・長二郎 カキ].

There appears to be an error in this entry. All of the manuscripts of the Nampō Roku (apparently including Jitsuzan’s original version which he copied with the original Shū-un-an documents in front of himself) -- with the exception of the presentation copy that Tachibana Jitsuzan gave to the Enkaku-ji -- read kōgō ・ Chōjirō-yaki [香合・長二郎ヤキ]*. Only the Enkaku-ji version reads kōgō ・ Chōjirō kaki [香合・長二郎 カキ].

The issue can best be addressed in this way. Chōjirō [長次郎] (to use the currently accepted representation of his name) had been employed by Hideyoshi to create the (unglazed) sculptures that would decorate the roofs of his Juraku-tei [聚樂第] palace (which entered the initial stages of construction earlier the same year -- 1586). Making glazed pottery for Rikyū was a side-job, almost more like a hobby. Chōjirō appears to have been familiar with the basic technology (which was similar to pottery techniques used in the kilns at Masan, in Korea -- though in that case they coated the raw clay with white slip before glazing, while Chojiro was using a slip colored with red iron-oxide), though it seems that he had never used it before in his own craft. Since he was not a professional potter who worked with glazes, he was still in the experimental stage in the autumn and winter of 1586, thus his bowls and other pieces from this early period are generally very simple and regular in shape (since he was still learning how the clay body interacts with glaze, and how both respond to the heat in the kiln). Chōjirō, as a professional sculptor, would certainly have been capable of modeling a kōgō that resembled a persimmon (or, indeed, an even more elaborate shape); but the other pieces fired at this time suggest that he did not do so because he was still learning how to make glazed pottery.

The error likely crept in because the katakana for ka [カ] is similar to the katakana for ya [ヤ] -- and the similarity may be even more pronounced in handwritten documents (and especially if the writing was done quickly, as appears to have been the case when Jitsuzan copied the Shū-un-an documents -- since he was apparently given only limited access to them). When Jitsuzan got around to writing out the presentation copy, he may have forgotten what he had originally seen, and interpreted his notes through contemporary knowledge -- that the pottery was referred to as Raku-yaki (not Chōjirō-yaki), even when speaking about pieces made by Chōjirō; and because the Raku family was, in his day, making kōgō in all sorts of shapes, including persimmons, copied from the so-called “katamono kōgō” [型物香合] that had been imported from the continent†.

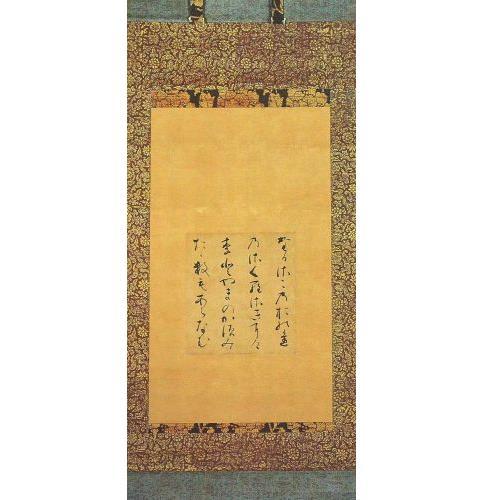

The cube-shaped kōgō shown above was made by Chōjirō during the early part of his career as a Raku potter‡. Indeed, this seems to be the earliest kōgō-like piece associated with his name. Thus, it may either be the kōgō that Rikyū used on this occasion**, or a sibling fired around the same time. ___________ *Some second-generation manuscripts, which were copied from the earlier versions, unambiguously read Chōjirō-yaki [長二郎燒] -- meaning that this word is being used as the name for the early Raku-ware created for Rikyū by Chōjirō [長次郎].

†As an example, here is a modern Korean copy of a classical Korean container (used as a seal-ink case), and a modern Raku kaki-kōgō.

The latter was clearly inspired by the prototype of the former, even if it was not copied directly.

‡Both the unstable quality of the glaze, and the fact that the piece had partly collapsed from the heat of firing attest to its early date.

**The imperfect quality of this piece (which mirrors the same sort of imperfection in both glaze and shape seen in Chōjirō’s mizusashi that was used during the first two chakai described in this kaiki from 1586~7) seems to be just the sort of thing that Rikyū appreciated; and its use on the (finely crafted) fukuro-dana would have been characteristic of his tastes as well.

¹¹Habōki [羽箒].

Rikyū does not mention the kind of feathers used for this habōki -- probably because habōki were replaced frequently*, and so did not demand special notice.

Because Rikyū is using an o-dana [大棚] in a 4.5-mat room, the habōki is of the larger size (with feathers around 9-sun long) -- the kind most commonly seen today†.

Because the chakai was taking place at night, it seems logical that he would have used some sort of light-colored feathers, such as those from a swan (haku-chō [白鳥]), shown above.

Rikyū seems to have gotten his feathers from the birds taken by Hideyoshi’s hawkers, and a quick glance back at the Rikyū Hyakkai Ki will give the reader an idea of the possibilities. ___________ *Some people during his period actually used them only once -- which is why we have very few authentic examples of habōki from Rikyū’s day.

†Because they were changed frequently, few habōki survived from Rikyū’s day (or before) into the Edo period. And, curiously, those that did were all habōki made from especially beautiful feathers from the earlier period (when a 4.5-mat room was always used -- in a room of 4.5-mats and larger, the “utensil mat” is considered to be a maru-jō, a full-sized mat; thus a larger habōki was used to clean it).

Lacking (or perhaps closing their eyes to) other examples, the machi-shū schools argued that the surviving habōki with feathers that average 9-sun in length were the only kind that were acceptable for use -- even in the small room, and even on the daime (and so directly opposed to Rikyū’s own teachings on the matter).

This is why the go-sun-hane [五寸羽] that were preferred by Rikyū for use in the small room (where the utensil mat is always considered to be a daime -- whether it is actually a daime-tatami or a full-length mat) are rarely seen and almost unknown today.

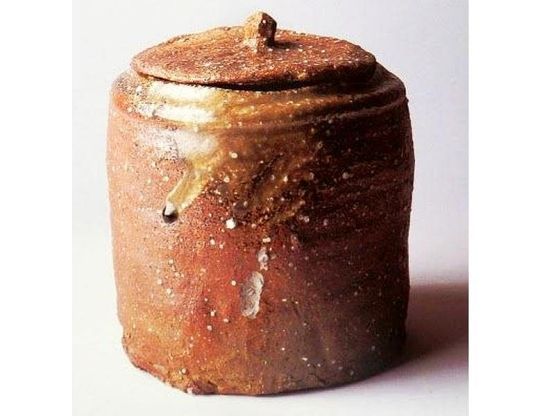

¹²Mizusashi ・ Shigaraki [水サシ・シカラキ].

This was Rikyū’s Shigaraki mizusashi, the same one he used during the chakai recorded in the Rikyū Hyakkai Ki.

In the sixteenth century (as had always been the case), the potters were primarily making things for home and commercial use, not for chanoyu. For the most part, they made tea utensils only on commission -- though it was from around this time (the last quarter of the sixteenth century) that some potters did occasionally make things that could be used for chanoyu without their being pre-ordered, and fired them when there was space in the kiln.

While some pieces were fired only once (like this one), others -- such as the hanaire and mizusashi that were heavily encrusted with natural ash deposits that were favored by Oribe -- usually went through multiple firings (it seems these pieces were simply left in the kiln when the utilitarian objects were removed for sale, in accordance with the feedback that the potters had received from people like Rikyū and Sōshitsu).

Because of the still relative rarity of such things, when a chajin acquired a piece that fulfilled his needs (aesthetic as well as practical), he was unlikely to think about replacing it.

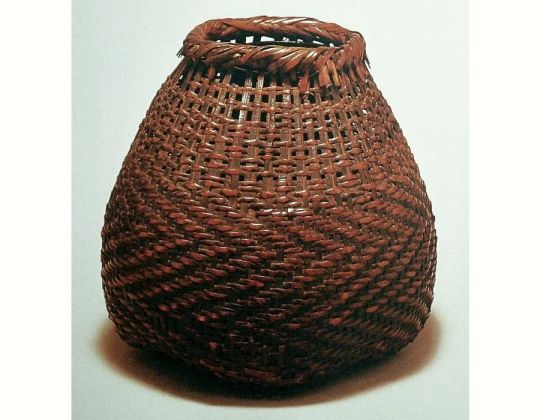

¹³Na-kago [菜籠].

The original na-kago [菜籠]* were shallower than this sumi-tori, made with a square bottom and somewhat flaring, circular mouth, and intended to display produce in the wet market (generally the price quoted by the merchant was for the contents of one basket).

This kago was made for Rikyū, probably to his design, and intended to be used as a sumi-tori†. The kind of bamboo that was used was referred to as abura-dake [油竹] (oily bamboo) in Rikyū’s period‡, and was salvaged from the underside of the roofs of farmhouses when they were rebuilt. Rikyū liked this kind of bamboo because of its mellow, aged appearance. Because the bamboo that was used to line the roofs was usually just 1-sun in diameter (this kind of bamboo was commonly available everywhere in Japan), with thin walls, it was suitable only for use when making something like a jizai [自在], for the so-called “purple” chasen and chashaku, or split and used in basketry, as here. ___________ *The kanji can also be pronounced sai-ro [菜籠].

†While Jōō‘s rule was that basket sumi-tori were to be used with the furo, and fukube sumi-tori were to be used with the ro, Rikyū occasionally used a basket with the ro. Aside from aesthetics, Rikyū’s usage may simply reflect the fact that tea utensils were increasingly being made specifically for use in chanoyu (and thus something like a basket could be made whatever size the person ordering it preferred), whereas in Jōō’s day people used pre-existing things that they found in the market (and na-kago, as the usual way to display produce, were both ubiquitous, and of a uniform size -- and that size was too small to hold a whole day’s supply of charcoal the way a fukube could), and so their preferences were limited to what they could find. In fact, this was how it had been since the beginning of chanoyu. Making things specifically for chanoyu was really a revolutionary idea, one that began with Furuta Sōshitsu -- and it was one of Oribe’s greatest contributions to the way that chanoyu evolved thereafter.

‡It is usually called susu-dake [煤竹] (smoke-stained bamboo) today, probably because the word abura-dake (especially when thinking about chasen) makes people think that it will damage the taste of the tea.

¹⁴Hoshi-sakana aburite [干肴 アフリテ].

Hoshi-sakana [干し肴] means “dried fish;” aburu [炙る] means to roast or char over a charcoal fire. Hoshi-sakana aburite is shown below.

The most common fish served in this way is the ma-iwashi [真鰯] (Sardinops melanostictus), known as the Japanese pilchard (a kind of “sardine”). It is also known in Japanese as nanatsu-boshi [七つ星] (”seven stars”), which name was explained as being a reference to the fact that usually seven of the dried fish (which are silver-gray in color) are tied together with a rice straw cord, and so sold in the market (the above photo, perhaps coincidentally, shows seven fish). Usually fish between 5- and 6-sun in length that were air-dried are served in this way.

This kind of food is a typical side-dish served together with sake [酒] -- even today.

¹⁵Sake ni kaeshi [酒 二返].

Kaesu [返す] means to come back, return. In the traditional drinking custom, the host drinks with each guest (he pours for the guest, and then the guest returns the sakazuki [盃] to the host, and pours him a drink of sake).

¹⁶Mizu-kuri [水栗].

The “water chestnut” (the English name is a translation of one of its Chinese kanji names) is the corm of the sedge known as shiro-guwai [白慈姑] (Eleocharis dulcis) in Japan. While often sweetened today by boiling the corms for a short time in honeyed water, they can also be grilled over charcoal, or even eaten raw. It is not clear from the kaiki how Rikyū prepared the mizu-kuri on this occasion.

However, both Tanaka Senshō and Shibayama Fugen quote a different explanation: according to their source, raw chestnuts are shelled, and then the pellicle (the thin, brown “skin” that covers the creamy-white flesh) is scraped away from one half of each fruit in a comma-like shape (”,”), so that each fruit resembled a 3-dimensonal futatsu-tomoe [二つ巴] (the “Yin-Yang” symbol). Because the pellicle is extremely bitter, the fruit must then be soaked in water for several hours to leech out the bitterness, after which the mizu-kuri can be served.

While their information is surely historically accurate, so far as this way of preparing raw chestnuts is concerned, the problem with their idea is that this was a fu-ji [不時] -- impromptu -- chakai. If Rikyū had sufficient forewarning to prepare a snack that required several hours of soaking, he would have had adequate time to cook and serve a kaiseki.

¹⁷Go [後].

This refers to the go-za [後座], the description of the arrangements for which follows.

◎ At the beginning of the go-za, the, the chaire and chawan were arranged together on a naka-bon [中盆], displayed on the tei-ita of the fukuro-dana, and the meibutsu futaoki was displayed alone on the naka-dana (the shelf above the mizusashi). The mizusashi remained as it was during the sho-za.

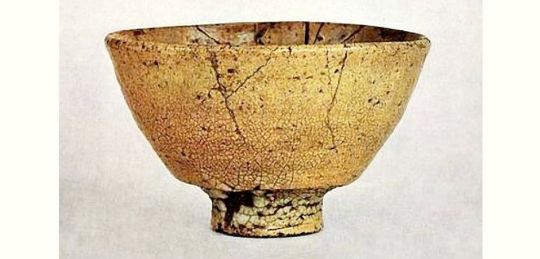

¹⁸Chaire ・ nasubi [茶入・ナスヒ].

This seems to be the nasu chaire now known as the Rikyū ko-nasu [利休小茄子] -- because the other “nasu-chaire” associated with Rikyū -- the Konoha-zaru [木ノ葉猿] -- would be too large to be arranged on a naka-bon together with Rikyū’s temmoku. The Rikyū ko-nasu is between 1-sun 9-bu and 2-sun in diameter; the Konoha-zaru chaire is 2-sun 5-bu in diameter.

Rikyū is said to have presented this chaire to Hideyoshi sometime after the present chakai.

This chaire is rarely seen today -- indeed, the above photo from the beginning of the 20th century, is the only one I could find. This chaire is considered to be a kan-saku karamono [カン作唐物 = 韓作唐物], which means it was made in Korea during the first half of the fifteenth century.

The small size means that it can only hold enough tea for two guests* (if both koicha and usucha will be served). ___________ *This is, in fact, usual with respect to the ko-tsubo chaire. In the old days, ko-tsubo were used when serving tea to a nobleman (originally, to the image of the Buddha). Thus only a single bowl of koicha would be made during the temae (the fact that the chaire held more than enough tea was a precaution; and filling the chaire fully also helped to protect the tea from contact with the air, which would cause it to degrade).

¹⁹Temmoku [天目].

This was Rikyu’s temmoku chawan, which he sometimes referred to as an ake-temmoku [朱天目], which is a sub-variety of the nogime-temmoku [禾目天目] that has an especially reddish-toned glaze. It appears that this chawan was actually produced at the Seto kilns; though what Rikyū knew or believed about its origins is unclear from the records that he left*.

This chawan measures 4-sun in diameter.

On this occasion, the (empty) temmoku was displayed on the naka-bon without its shifuku†. The temmoku-dai (if one was used‡) would have been put inside the ji-fukuro prior to the temae. ___________ *Rikyū clearly seems to have handled it as if it were a karamono temmoku.

†Rikyū actually seems to have disliked this classical practice, considering that the cloth of the shifuku would trap dust, which could fall into the chawan as lint, and make it dirty. He preferred to rinse the chawan in the mizuya, and then leave it without a covering -- whether or not the chakin, chasen, and chashaku were placed in it (though the absence of the shifuku is an invitation for the host to do this, too).

‡Nothing is said in the kaiki regarding this point. The temmoku-chawan could not have been displayed on the naka-bon together with the chaire if it were resting on its dai: the naka-bon is too small for this kind of arrangement.

Rikyū generally seems to have felt that a dai should be used only when serving a nobleman (what the modern schools usually call kijin-date [貴人立て, or 貴人點] today). And while it could be argued that Hosokawa Yūsai might be so treated, because this gathering was taking place at night (when it is generally more difficult to do things), the setting itself would argue against its use.

²⁰Naka-bon [中盆].

While both Shibayama Fugen and Tanaka Senshō say this refers to the round naka-maru-bon [中丸盆] that was one of the six meibutsu trays that were used with the daisu, the larger size of that tray would have made it more difficult to manage at night, when the room was dark. Consequently, the square naka-bon seems more likely.

The shi-hō naka-bon [四方中盆] was not one of the original six meibutsu trays that were used with the daisu. Nevertheless, its use dates at least from the fifteenth century. It is also described in Book Six (“Sumi-biki” [墨引き]) of the Nampō Roku (along with the other six trays).

This shi-hō naka-bon measures 1-shaku square. ___________ *Rikyū’s personal preference for smaller trays also argues for the 1-shaku square shi-hō naka-bon. Also, Rikyū preferred square trays to round ones -- since square trays can be oriented with greater accuracy.

The naka-maru-bon measures 1-shaku 2-sun 3-bu in diameter -- slightly larger than the space available in front of the fukuro-dana. Something else that would have chafed on Rikyū’s sense of propriety.

²¹Futaoki ・ in [蓋置・印].

This was the meibutsu Rinzai-in [臨濟印] (a square bronze name-seal, purportedly made by order of the Emperor of China, that was used by the Tang period Chán monk Línjì Yìxuán [臨濟義玄; ? ~ 866]).

This name-seal had formerly belonged to the great dōbō [同朋] Nōami [能阿彌; 1397 ~ 1471]; and its use as a futaoki is generally credited to him.

Rikyū follows Nōami’s precedent at this chakai.

The Rinzai-in would have been displayed in the middle of the naka-dana (the shelf above the mizusashi) of the fukuro-dana, with the hishaku placed on the kō-dana (the shelf that forms the roof of the ji-fukuro).

²²Kae-chawan ・ e [カヘ茶碗・繪].

This chawan dates to the middle of the Ming dynasty, and was probably imported from the continent around the middle of the sixteenth century.

The bowl seems to have been made as an ordinary rice bowl, rather than for any special purpose.

This chawan is now known by the name of Ki-mi-i-dera [紀三井寺], which is a (perhaps fanciful) reference to the painting that decorates the face of the bowl; it is also said to have been one of the first sometsuke [染付] bowls to be used as a chawan in Japan.

The chakin, chasen, and chashaku were brought into the room arranged in the kae-chawan. It may also have been used to help facilitate the serving of usucha afterward.

²³Chashaku ・ ori-tame [茶杓・折タメ].

This would have been a chashaku that Rikyū made to be used with the ko-nasu chaire [小茄子] that is shown above -- albeit in consideration of the fact that it would be rested on a naka-bon (which means that the chashaku had to be longer than if the chaire were being used with a smaller chaire-bon).

²⁴Koboshi ・ Bizen [コホシ・備前].

The Bizen-yaki koboshi shown below was apparently recovered from the site of Rikyū’s former residence (in the Ima-ichi area of Sakai, near the entrance to the Nanshū-ji). The irregular coloring is due to the fact that it was recovered in fragments, and the missing pieces were replaced without attempting to obscure the fact.

This piece may be the actual Bizen koboshi that Rikyū used during this chakai.

1 note

·

View note

Text

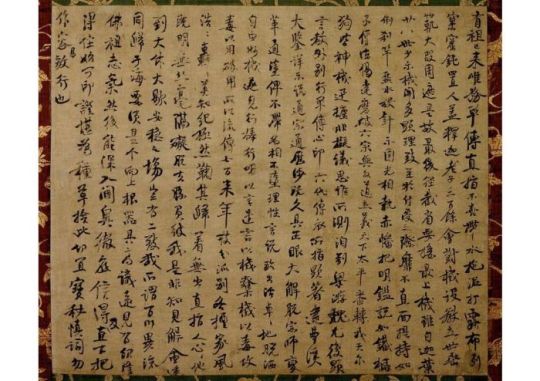

Appendix 2: Rikyū’s Utensils (1) -- Kakemono [掛物].

Kakemono [掛物] (18 scrolls).

The utensils here (and in the following appendices) are arranged by order of frequency. Following the number of incidences is a list (in parentheses) of all of the posts in which the utensil is featured. The numbers refer to the list of URLs published in the preceding appendix.

In general, utensils that Rikyū used frequently he probably owned outright, while those that he only used one or two times were probably borrowed from Hideyoshi’s collection (or, occasionally, lent to him by other chajin -- in the hope that their being featured in one of Rikyū‘s high-profile chakai might help the owner find a buyer).

1. Yoku-ryō-an bokuseki [欲了庵墨跡].

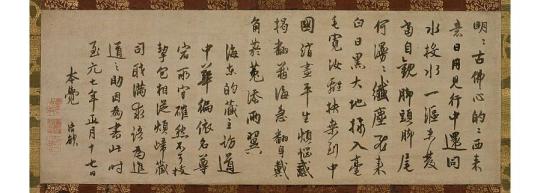

Yoku-ryō-an [欲了庵] is the name by which Rikyū referred to this scroll -- which was perhaps one of Rikyū’s most prized possessions. It was written by the Yuan period Chán monk Liǎo-ān Qīng-yù [了庵清欲; 1288 ~ 1363].

This scroll appears in the kaiki sixteen times (featured in the gatherings covered in the posts 13, 14, 20, 23, 25, 30, 32, 36, 37, 38, 45, 49, 50, 53, 54, 55).

2. Tōyo bokuseki [東與墨跡].

This refers to a bokuseki written by the Yuan period monk Dōnglíng Yǒng-yú [東陵永璵; 1285 ~ 1365]* (whose name is pronounced Tōryō Eiyo in Japanese).

He is said to have been related to the great Chán master Wúxué Zǔyuán [無學祖元; 1226年 ~ 1286] (Mugaku Sogen in Japanese). Both Wúxué and Dōnglíng emigrated to Japan in order to spread the orthodox Chán teachings.

Dōnglíng Yǒng-yú was a follower of the Sōtō sect [曹洞宗] of Chán; and, as mentioned above, he came to Japan in Shōhei 6 [正平六年] (1351). Although he was a monk of the Sōtō Shū, he served as the abbot (jūji [住持]) of a number of important Japanese temples that had no affiliation with that sect, among which were the Tenryū-ji [天龍寺] and Nanzen-ji [南禪寺] in Kyōto, and the Kenchō-ji [建長寺] and Enkaku-ji [圓覺寺] in Kamakura.

This scroll was used on seven occasions during the year covered by this kaiki (3, 11, 22, 27, 29, 39, 44).

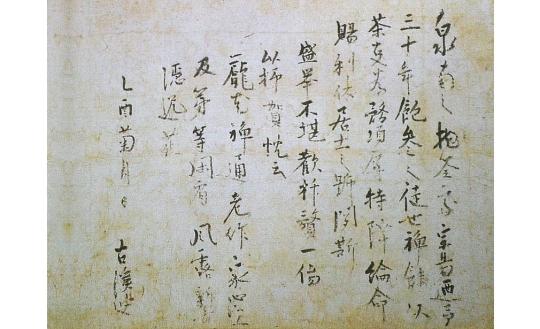

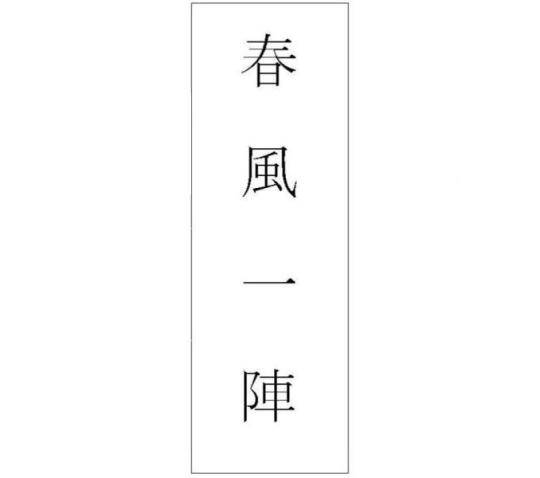

3. Kokei Ichi-gyo-mono [古溪一行物].

Kokei [古溪] refers to Kokei Sōchin [古渓宗陳; 1532 ~ 1597], who was also known as Ho-an Kokei [蒲庵古溪]. . He was Rikyū's Zen master*.

This refers to an ichi-gyō-mono [一行物] (a vertical scroll containing a single line of characters) of the phrase “shun-fū ichi-jin” [春風一陣] (which means “a gust of Spring wind”). This scroll was one of Rikyū's personal treasures.

This scroll disappears from contemporary records in 1591 -- and was probably was destroyed (on Hideyoshi's orders) around the time of Rikyū's seppuku.

This scroll was displayed during five chakai in the cycle covered by Book Two of the Nampō Roku (5, 16, 18, 19, 35).

4. Engo bokuseki [圓悟墨跡].

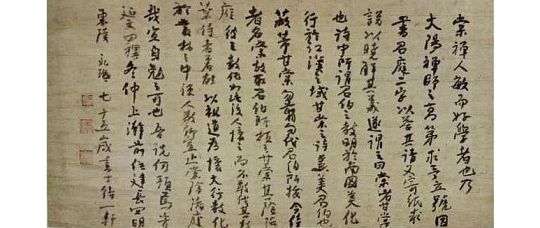

This is the bokuseki known as the Nagare Engo [流れ圜悟], formerly owned by Shukō (this is the scroll that tradition holds was presented to him by Ikkyū Sōjun), which he hung in his room when serving tea. It is further said to have been the first bokuseki ever used for chanoyu.

The scroll was written by the Chinese Chán monk Yuán-wù Kèqín [圜悟克勤; 1063 ~ 1135], the editor of the Bìyán Lù [碧 巖 錄] (Heki-gan Roku; the Blue-cliff Records).

This document was not intended (by its author) to be mounted as a scroll: it is actually a fragment of the text of one Yuán-wù’s lectures (who traveled around China delivering lectures on the cases in the Bìyán Lù at various major temples, and this was part of the text of one of these lectures).

Rikyū used it at four gatherings (1, 21, 24, 48).

5. Kurin Setchū-jōdō bokuseki [古林 ・ 雪中上堂墨跡].

The name Kurin [古林] refers to the Yuan dynasty Chán monk Gǔlín Qīngmào [古林清茂; 1262~1329]. A number of his bokuseki have been preserved in Japan*.

Setchū jōdō [雪中上堂] seems to be the first part of a seven-character kōan [公案] that formed part of a Chán poem (the whole line apparently being setchū jōdō setchū bai [雪中上堂雪中梅]; which would mean “the Upper Hall [of the temple] is obscured by snow; the plum [blossoms] are obscured by snow”: the Upper Hall would seem to refer to the monk's Buddhist scholarship (or training); the plum blossoms would refer to his enlightenment (or samadhi), both of which are to be obscured by the whiteness of the snow): and, indeed, Gǔlín Qīngmào's surviving works largely consist of a poem, followed by a dedicatory or explanatory passage.

The words in question, however, are not found in any of his surviving kakemono, however, suggesting that the scroll displayed by Rikyū on these four occasions (8, 9, 11, 40) has been lost -- indeed, the lack of clarity suggests that this occurred before the beginning of the Edo period.

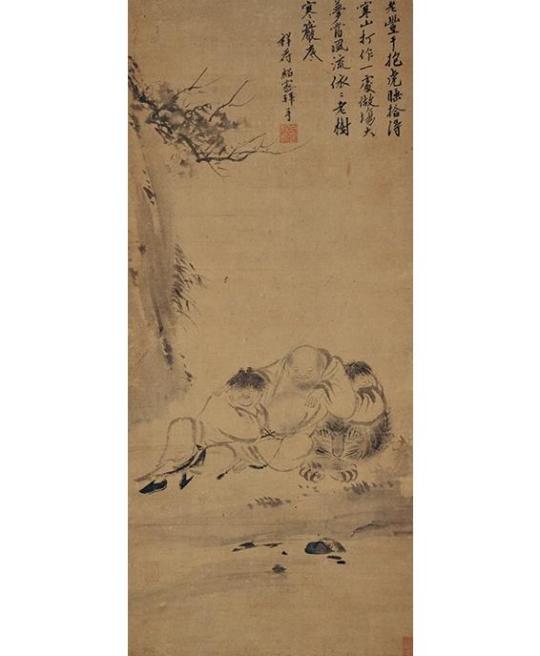

6. Moku-an Ji-ga ji-san Kanzan Jittoku e [黙庵自畫自讃 寒山拾得繪].

This refers to the Japanese monk-artist Moku-an Rei-en [黙庵霊淵; ? ~ c 1345]. He is said to have been tonsured as a monk in Kamakura (though his biographies do not identify the temple) sometime before 1323, and subsequently traveled to China in 1327. He became a renowned Zen painter, working with ink sketches, and a number of his paintings bear colophons by some of the eminent (Chinese) Chán monks of the day. A number of these were later brought back to Japan by other travelers, where they were especially treasured. Moku-an died in China around 1345.

Ji-ga ji-san [自畫自讃] means that both the painting (ga [畫]) and the colophon (san [讃]) were done by Moku-an himself. Meanwhile, this painting is usually known as Shì-shuì-tú [四睡圖] (in Japanese, Shi-sui zu: “Picture of the Four Sleepers”).

Hánshān [寒山], Shí-dé [拾得], and Fēng-gān [豐干] -- the subjects of this sketch -- were all renowned Tang period monk-poets, who were often referred to as the Tiāntái sān-shèng [天臺三聖] -- the three [poetic] sages of Tiāntái (Mountain).

As the three monks and their tiger (who represents their Chán energy) are sleeping out of doors, the picture suggests both intimacy, confident repose, and the warming season. The three chakai (31, 33, 34) at which this painting was displayed were held at the beginning of summer.

7. Kokei oshō Saiji [古溪和尚・細字].

Saiji [細字] means a document written in small writing. This is the second scroll by Kokei Sōchin [古渓宗陳; 1532 ~ 1597] that Rikyū owned.

It is rather surprising that this kakemono has survived into the present -- and that was only because it had been hidden from Hideyoshi in the archives of the Daitoku-ji around the time of Rikyū’s death. Rikyū used it on three occasions that are described in Book Two of the Nampō Roku (7, 46, 47).

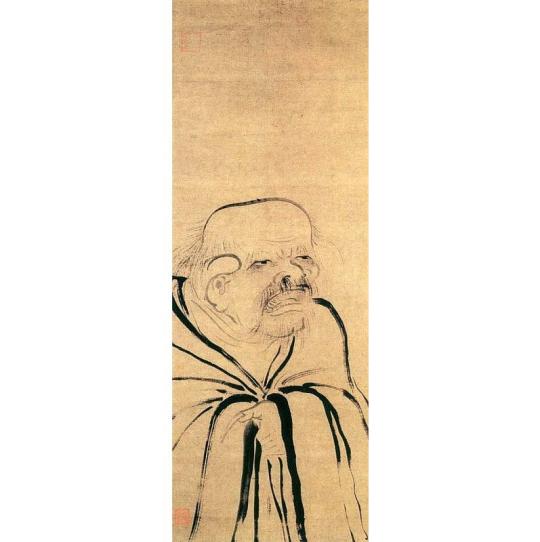

8. Mokkei Jurō-jin e [牧溪 壽老人繪].

The name Mokkei [牧溪]* refers to Mùxī Fǎcháng (牧溪法常; 1210? ~ 1269?), a Chán monk who lived during the Southern Song Dynasty -- and who was arguably one of the greatest Chán painters in all of Chinese history. His works, indeed, are frequently used to illustrate the essence of the medium. He left behind not only a collection of outstanding masterpieces, but also served as a model for generations of monk-painters to come, both on the continent and in Japan.

Among Mùxī’s surviving portraits is one that is said to be of the ancient Chinese sage Lao-tzu [老子] (shown above). Perhaps the actual subject of this painting was not clear to Rikyū, and he took it to be a more generic portrait of an old man (or of a sort of god of long-life, which is what jurō-jin means).

Rikyū displayed this scroll on two occasions (15, 17) -- one of which was completely private (he invited no guests for his first tea of the New Year).

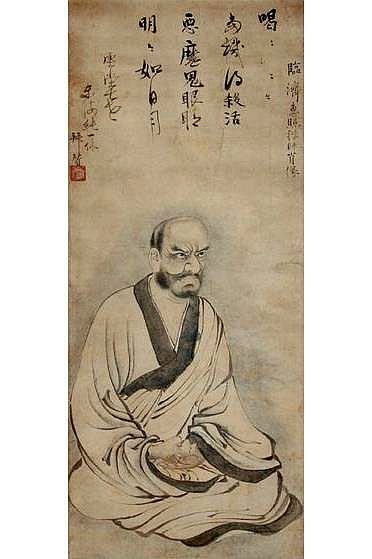

9. Rinzai zenji zō [臨濟禪師像].

Though Rikyū mentions nothing but the subject matter, this appears to be a painting by the fourteenth century Japanese artist Soga Jasoku [曾我蛇足; his dates of birth and death are not known].

While most of the details of Jasoku's career have been lost to history, it is said that he studied Zen under Ikkyū Sōjun [一休宗純; 1394 ~ 1481] -- and, in turn, seems to have taught Ikkyū painting.

This kakemono was hung in the toko on two occasions (51, 56).

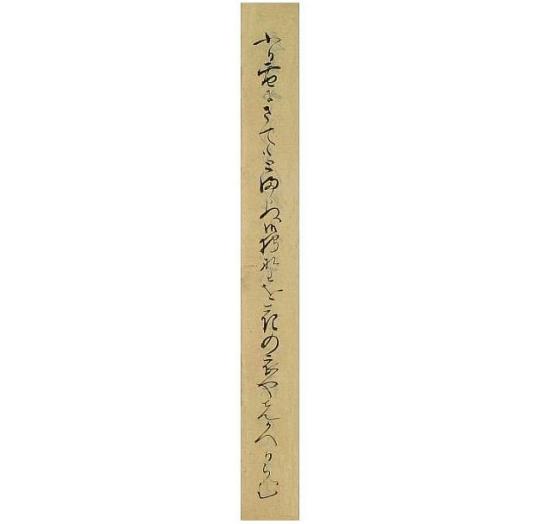

10. Waka-tanzaku [和歌短尺/短冊].

This tanzaku, probably written by Lord Hino Terusuke [日野輝資; 1555 ~ 1623] during the court banquet that was held earlier that day (the text of the poem is unknown), was presented to Rikyū tied to a chrysanthemum (the flowers, with poems tied to each, were displayed in the Imperial presence during the banquet).

This tanzaku has not been identified. The flower with the tanzaku tied to it was hung in the tokonoma during the chakai that Rikyū hosted on the evening of the day of the banquet (4).

11. Jōō Daikoku-an no uta [紹鷗大黒庵ノ哥].

According to Rikyū (as he wrote in the Fukuro-dana no densho [袋棚の傳書] that he addressed to Nomura Sōkaku), before his death Jōō presented him with a single book (or, possibly, scroll*) of his teachings, within which he found several loose sheets of paper on which Jōō had written verses in his own hand. This poem was one of them:

waga na wo ba daikoku-an to iu nareba, fukuro-dana ni zo hiji to komekeru

[わか名をば大黒庵といふなれば、 ふくろ棚にぞ祕しとこめける].

(“If it may be said that my name is Daikoku-an, then it is in the fukuro-dana that I conceal my secrets.”)

This scroll was hung in the toko on a single occasion -- during the chakai that Rikyū hosted on the anniversary of Jōō’s death (6);

12. Teika-kyō Furi-yuki ni [定家卿 降雪に].

Fujiwara no Sadaie [藤原定家; 1162 ~ 1241], who is also known (perhaps more commonly) as Fujiwara Teika [藤原定家]*, was a renowned poet, poetic critic, calligrapher, novelist, anthologist, scribe, and literary scholar of the late Heian to early Kamakura periods.

This poem, which is found in Sadaie's personal poetry anthology (the Shūigusō [拾遺愚草]), reads:

furi-yuki ni sate mo tomaranu mikari-no wo, hana no koromo no mazu kaeriran

[降る雪に偖もとまらぬ御狩野を、 花の衣の先かへりらむ].

-- “the snow is falling, so truly I must not delay: even though Mikari-no is dressed in flowery robes; anyway, I must return [home].”

While a number of Fujiwara Sadaie’s shikishi and other writings have been preserved, this one is unknown.

It was displayed during a single chakai (9).

13. Mokkei Taiki kaisan [牧溪戴逵繪讚].

“Mokkei” is the Japanese pronunciation of the name of the Southern Song Chán monk and artist Mùxī Fǎcháng [牧溪法常; 1210? - 1269?].

This refers to a painting by Mùxī Fǎcháng known as Setsu-ya hou Tai [雪夜訪戴] (“a snowy-night's visit to Tai [= Dài Kuí]”).

This kakemono , which was probably part of Hideyoshi’s collection, was displayed at one chakai (10).

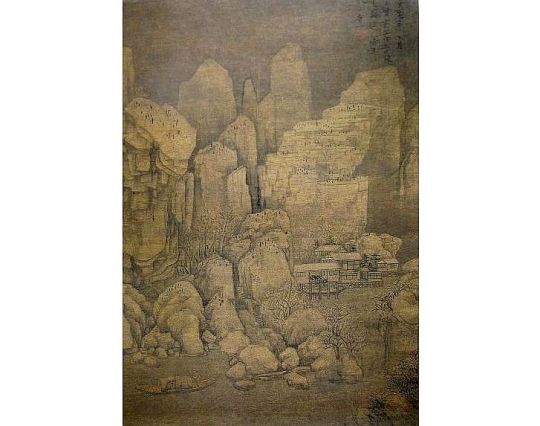

14. Ni-fuku ittsui Ba En san-sui [二幅一對 馬遠山水].

Ni-fuku ittsui [二幅一對] means a diptych, a pair of pictorial scrolls intended (though not necessarily by the artist) to be hung in the toko at the same time (they usually feature identical mountings).

“Ba En” is the Japanese pronunciation of Mǎ Yuǎn [馬遠; c. 1160 or 1165 ~ 1225]. Mǎ Yuǎn was an important painter, from a family of professional painters, of the Southern Song dynasty. His works are mentioned six times in the Kun-dai Kan Sa-u Chō-ki [君臺觀左右帳記], by Nōami [能阿彌], and four times in Sōami's [相阿彌; ~ 1525] O-kazari Sho [御飾書].

This pair of scrolls were hung in the shoin during the second part of a chakai that Rikyū hosted for Hideyoshi (13).

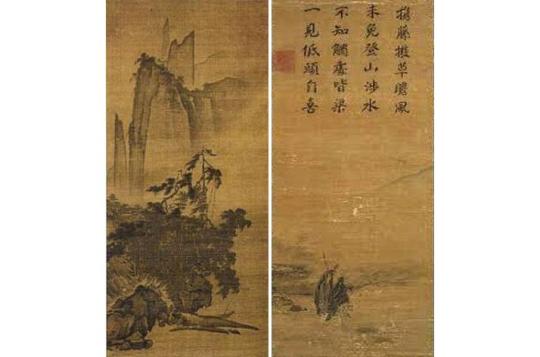

15. Shunkyo Momo-no-e [舜擧 桃繪].

Shùn-jǔ [舜擧] is one of the names used by the Chinese painter Qián Xuǎn [錢選; 1235 ~ 1305], who is also known as Yù-tán [玉潭]. He was active from the late Song into the early Yuan dynasty.

Among Qián Xuǎn's surviving paintings is one that is known as “a broken-off branch of peach blossoms” (Zhézhī táo-huā [折枝���花]), which may have been the painting displayed by Rikyū on this occasion.

This scroll was used on the third day of the Third Lunar Month (26), which is known as the momo-no-seku [桃の節句], or peach-blossom festival.

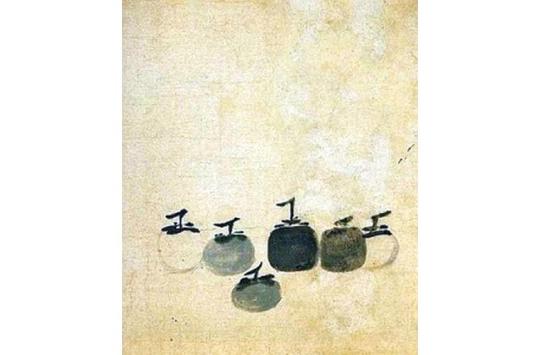

16. Mokkei Kashi-e [牧谿 菓子繪].

This was a painting by the Chinese monk-artist Mùxī Fǎcháng [牧溪法常; 1210? - 1269?] -- known in Japan as “Mokkei” [牧谿]*.

It is generally believed that the painting in question was the famous one of six persimmons, which is preserved in the Ryōkō-in [龍光院] subtemple of the Daitoku-ji in Kyōto.

Rikyū used this scroll once (28).

17. Ue-sama o-ji-hitsu o-ji-ei kakemono [上樣御自筆御自詠カケ物].

This refers to a waka-kaishi [和歌懐紙], written by Toyotomi Hideyoshi on the occasion of his previous visit to the Same-ga-i [醒ヶ井], a famous well in Kyōto. It was displayed during the chakai that Rikyū hosted for Hideyoshi’s second visit to the compound housing the well (41).

18. Mokkei Kuri-kaki e [牧溪 栗柿繪].

This refers to a painting of chestnuts (kuri [栗]) and persimmons (kaki [柿]), by the Southern Song Chán monk and artist Mùxī Fǎcháng [牧溪法常; 1210? - 1269?].

References sometimes confuse this work with Mùxī’s other painting of fruit, the Kashi-e [菓子繪] -- though Rikyū’s notes make it clear that they were different paintings.

He displayed on one occasion (52).

0 notes

Text

Nampō Roku, Book 2 (42): (1587) Sixth Month, the Last Day, Evening.

42) Sixth Month, the Last Day¹.

◦ [At the] Lower Kamo [Shrine], on the bank of the river²; however, [the service of tea was] at dusk, on the occasion of the ritual purification³.

◦ [Guests:] Myōhō-in [妙法院]⁴, Hino dono [日野殿]⁵, Yūsai [幽齋]⁶, Ryōmu [了無]⁷.

◦ [Suspended from] an ori-gake-take [折カケ竹]⁸, the kiri no ko-gama [桐ノ小釜]⁹.

◦ Sugi te-oke [杉手桶]¹⁰.

◦ Within the chabako [茶箱ノ内]¹¹: ◦ chaire maru-tsubo [茶入 丸壺]¹²; ◦ chawan Mishima-zutsu [茶碗 三嶋筒]¹³.

▵ Sage-mono [さけ物], in which were [arranged] the kashi [菓子]¹⁴.

_________________________

¹Roku-gatsu mizoka [六月晦日].

The Sixth Month of Tenshō 15 had only 29 days. The date of this chakai, consequently, was August 3, 1587.

²Shimo-gamo kawa-bata ni te [下加茂川端ニて].

Shimo-gamo [下加茂] is a reference to the Kamo-mioya Jinja [賀茂御祖神社], which is commonly known as the Shimo-gamo Jinja [下鴨神社; or, as Rikyū is attempting to write*, 下 賀茂 神社], the “Lower” Kamo Shrine†.

The river-bank was the site of lustrations, and probably had been used for this purpose earlier in the day. ___________ *He has confused the second kanji of the shrine’s name ka [賀] with the homophonous ka [加].

†The “Upper” Kamo Shrine is formally known as the Kamo-wakeikazuchi Jinja [賀茂別雷神社]. “Upper” and “Lower” refer to their geographic positions (the Upper Shrine is higher up the Kamo river from the Lower Shrine; the Lower Shrine is located at the point where the Takano river joins the Kamo river); the Kamo river [Kamo gawa, 鴨 川] entered the ancient city at its north-eastern corner: this corner is, according to the teachings of Feng-shui [風水] (Fū-sui in Japanese; the ancient Chinese geomancy), known as the ki-mon [鬼門] (the demon’s gate), and the shrines were established by the Kamo clan (long before the capital was relocated to Kyōto) to protect their settlement from these potentially malign influences.

Incidentally, the Lower Shrine is thought to be about a century older than the Upper Shrine.

³Tadashi, yūgata o-harai no tsuide [但、夕方御秡ノ序].

This statement literally means “however, [this chakai was held on] the occasion of the great purification ritual in the evening.”

O-harai [御秡] -- perhaps he means ō-harai [大祓], “the great purification ritual” -- refers to the Minazuki-barae [水無月祓], the lustration held on the last day of the Sixth Lunar Month*. The purification rites were also referred to as the Nagoshi no harae [夏越しの祓].

The statement is somewhat ambiguous: it is unlikely that Rikyū was serving tea during the confusion of the lustration itself, so this chakai was probably taking place after the crowds had gone home. ___________ *The Minazuki-barae took place on the last day of the the Sixth Month, and were intended to clean out the pollution that had accumulated during the first half of the year (another lustration was held at the end of the Twelfth Month, to deal with the impurities of the second half of the year). Various ceremonies at the Shinto shrines gave participants the opportunities to separate themselves from this pollution (specifically, folded paper streamers, such as are often seen in Shintō rituals, were rubbed on the body, and then cast into the river -- in the general area where Rikyū was hosting this chakai); the lustrations had also served as a social event since at least the Heian period (they frequently figure in scenes in the various monogatari -- one of the earliest references being found in the Ise Monogatari [伊勢物語] -- since this was one of the occasions when women went out in public).

⁴Myōhō-in [妙法院].

This was the Prince known as Myōhōin-no-miya Jōinhō shinnō [妙法院常胤法親王; 1548 ~ 1621], Abbot of the Myōhō-in [妙法院], a branch temple of the Enryaku-ji [延暦寺], a temple of the Tendai Sect (Tendai-shū [天臺宗]).

The fifth son of Prince Fushimi (Fushimi-no-miya Kunisuke shinnō [伏見宮邦輔親王; 1513 ~ 1563]), he had been adopted by the Emperor Ogimachi so that he could be appointed to this abbacy (Ogimachi having fathered only one son, who was naturally named the heir-apparent, while this abbacy also required an imperial son).

⁵Hino dono [日野殿].

This refers to Lord Hino Terusuke [日野輝資; 1555 ~ 1623], a kuge [公家]*, who rose to the office of Gon-dainagon [権大納言] (supernumerary) Chief Counselor of State (holding the senior grade of the Second Rank).

He seems to have had some sort of connection with Myōhō-in, since they appear as fellow guests at other chakai (with Myōhō-in naturally taking the seat higher than Hino Terusuke). __________ *A court noble. Lord Hino was a hereditary nobleman, rather than someone raised up from the military caste (as was the case with most of the nobles surrounding Hideyoshi).

⁶Yūsai [幽齋].

This was the the literary scholar and (former) daimyō Hosokawa Fujitaka [細川藤孝; 1534 ~ 1610], who was known as Hosokawa Yūsai [細川幽齋] after his “retirement” from secular life following Akechi Mitsuhide's attack on Nobunaga at the Honnō-ji in Kyōto.

He was the second attendant at the previous chakai, and additional information about his life and career can be found in that post, under footnote 6.

⁷Ryōmu [了無].

The name (which means something like “at the end there is nothing”) would seem to be the sort affected by a monk; but nothing is known about this person.

⁸Ori-gake-take ni [折カケ竹ニ].

This refers to a sort of tripod made from three lengths of bamboo*. The bamboo were usually secured by wrapping a cord (or, as in the present day, the far end of the chain on which the kama would be suspended) around them about 1-shaku below the upper end of the poles.

The kama was suspended over a depression in the ground (usually lined with roof tiles, or something of the sort, to protect the fire from the dampness of the ground), in which a charcoal fire was kindled.

This kind of arrangement is still used at outdoor chakai today.

While things were probably set up so that the kama was suspended between the host and the guests (and so resembling the ro in a 4.5-mat room or a room with a daime-gamae), it is not possible to say anything definitely, since Rikyū is moot on this point. __________ *Shibayama Fugen states that the pieces of bamboo were cut, gathered together, tied, and then stood up at the place where tea would be served.

According to Tanaka Senshō, however, at least one of the pieces (and possible all three) were actually left attached to their roots, with the tops simply pulled together and tied to form a tripod (though this would be doubtful if the gathering took place on the riverbank -- as Rikyū says -- since bamboo does not grow near the water).

⁹Kiri no ko-gama [桐ノ小釜].

This was the small kiri-gama, originally made as a kiri-kake kama for a small kimen-buro, but whose bottom had rusted away.

The kama seems to have been repaired by Jōō (it lookd the same then as now), who used it as a tsuri-gama (perhaps the first kama suspended from the ceiling on a chain) in the ro.

¹⁰Sugi te-oke [杉手桶].

This was a handled bucked made entirely of fragrant cryptomeria wood, with cherry-bark stitching*.

The water was probably drawn directly from the Kamo-gawa using this bucket. ___________ *The fact that the modern schools tend to use this kind of bucket when offering hot water to the guests for washing their hands at the chōzu-bachi in winter is irrelevant. Rikyū seems to have preferred generally not to do so; but when circumstances or the particular guests made offering hot water appropriate, Rikyū gave it to them in a kata-kuchi (with an assistant posted at the chōzu-bachi to pour the hot water while the guest rubbed his hands together under the stream).

¹¹Chabako [茶箱ノ内].

The word chabako [茶箱] refers to two different things in the Nampō Roku. Sometimes it is used to mean what we now call a sa-tsū-bako [茶通箱], a box in which one (or up to three) lacquered containers of matcha were sent to someone as a gift: this kind of chabako was made to match the dimensions of the tea container(s) it would hold. The other use is, as here, to mean a medium-sized te-bako [手箱] in which the chawan (containing the chakin and chasen, with the chashaku resting across the rim) and the chaire were placed side-by-side.

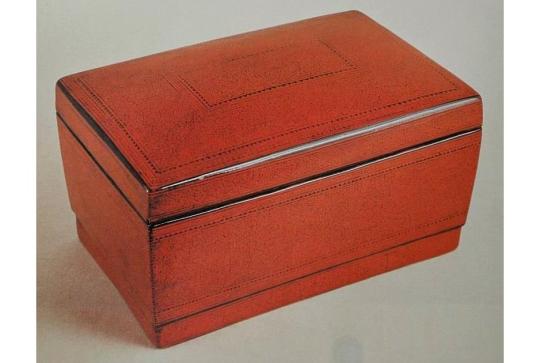

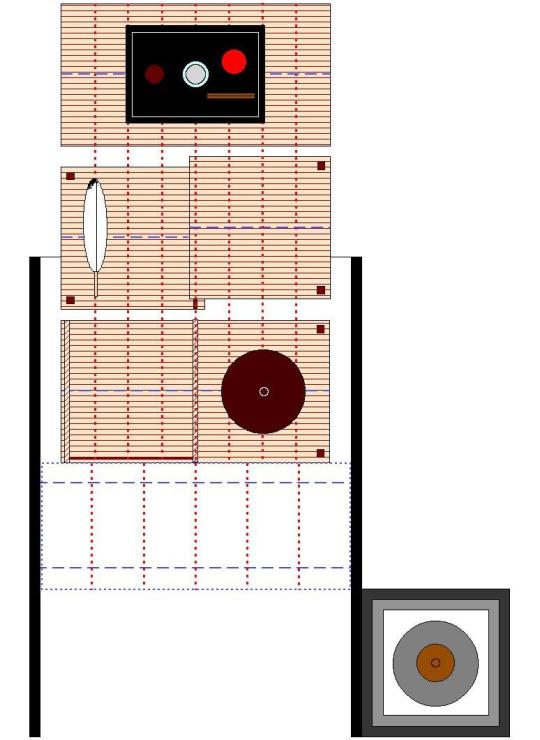

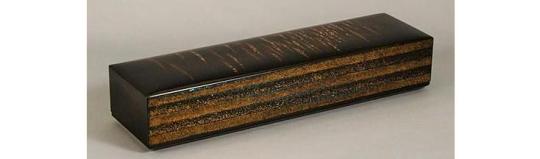

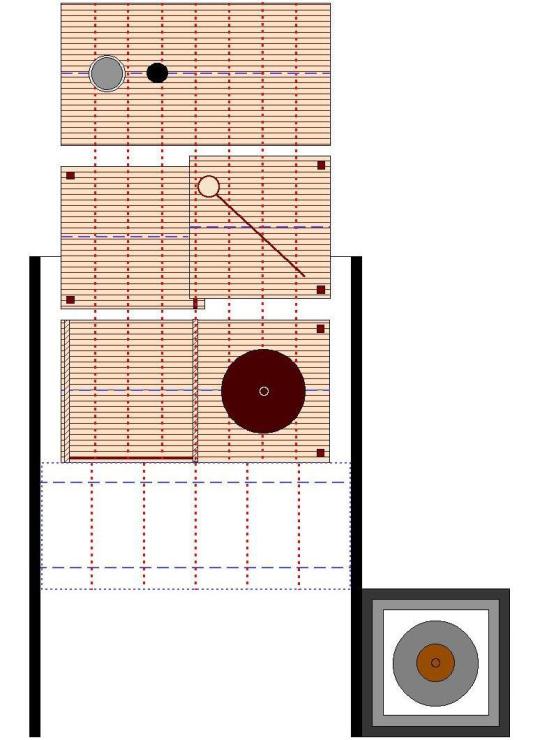

The te-bako that Rikyū used to carry a chawan and chaire on outings of this sort is shown above*.

The reader is cautioned to remember that the modern “chabako-temae” were a product of the modern period, and have nothing to do with Rikyū.

First, there were two different ways in which this kind of thing could be done: either the host, and the guests, simply squatted down on the ground (with the utensils arranged on boards that were set out for this purpose), or tatami mats were placed out for the people (and utensils) to sit on†.

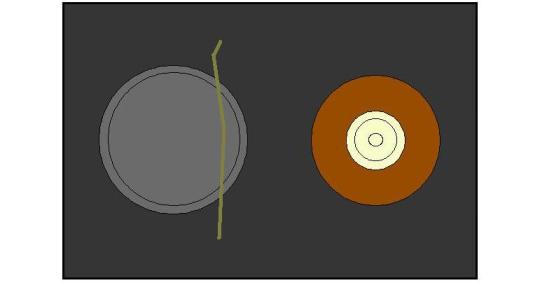

That said, Rikyū probably displayed the box in front of the mizusashi placed horizontally (so the chawan and chaire would be oriented as usual -- as shown in the above sketch, where the box, chawan, and chaire are all drawn to scale), in lieu of a tana or dōko; or perhaps he may have placed the box on the left side of the mat (where a dōko would ordinarily be found). At any rate, at the beginning of the temae, he simply opened the lid and lifted the chawan and chaire out, and then placed them down in front of the mizusashi (first the chaire, and then the chawan‡).

If the beach was covered with pebbles, Rikyū probably discarded the used water onto the pebble-covered ground to the left of his seat; or, if the waste water would not flow away immediately, possibly a small hole was dug in the ground to receive the water. In either case, a koboshi would not have been needed. __________ *This kind of lacquerware is called kimma [キンマ = 蒟醬], and was a product of south-east Asia (probably the country then known as Annam [安南]). The piece is made of basketry, which is then painted with numerous coats of black lacquer until a smooth surface is achieved. Then a layer of red lacquer is painted on top and, after it dries, a design is etched into the lacquer (revealing the layer of black underneath) with a nail.

Rikyū's chabako measures 4-sun 6-bu high, 7-sun 8-bu from side to side, and 5-sun 2-bu front to back (and so is a little larger than the chabako that they sell today).

†Since this gathering was being held during the hot spell that followed the rainy season, it is possible that Rikyū may have erected platforms extending out over the water, with the fire located just on the bank. In this case, a koboshi would not have been used; the waste water simply being poured over the side into the river.

‡This follows the teaching of tai-yō [軆用], where the chaire takes its place first (oriented relative to the mizusashi), and then it is used to guide the host when positioning the chawan.

Tai [軆] means the object that is already in place, and yō [用] the second object that finds its place relative to the first. (In this case, the back side of the foot of the chawan is placed so that it is in line with the back side of the chaire, and it is set down 2-sun away from it.)

Placing them down simultaneously, as some modern schools teach, runs contrary to Rikyū's teachings.

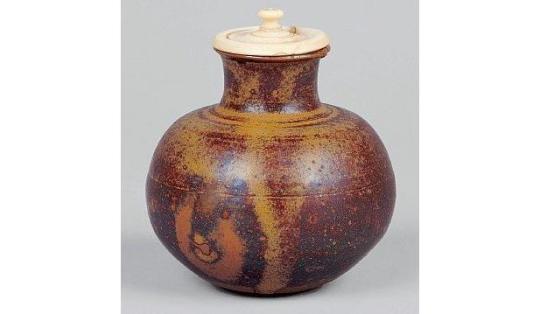

¹²Chaire maru-tsubo [茶入 丸壺].

This is the chaire now known as the Rikyū maru-tsubo [利休丸壺], shown below.

This is a karamono chaire; it measures 2-sun 4.5-bu in diameter (and so is only slightly smaller than the chawan).

Though not mentioned in the record of this chakai, the chashaku would have been one of Rikyū's ori-tame [折撓]. During the temae it would have been leaned against the lid of this chaire, with the butt end touching the floor.

The temae-za is reckoned as being 6-sun from front to back. For this reason, the length of the handle would have been determined by the space available in front of the chaire, as shown in the following sketch.

¹³Chawan Mishima-zutsu [茶碗 三嶋筒].

This was the Korean tsutsu-chawan that Rikyū sometimes refers to as Hikigi-no-saya [引木の鞘].

As at several other chakai held during this period of intense heat, using a deep chawan allowed Rikyū to make the tea as cool as possible -- the deep bowl preventing the tea from cooling further before the guest was able to drink it.

In addition to the above utensils, Rikyū would also have needed a futaoki -- and a take-wa [竹輪] is most likely.

¹⁴Sage-mono, kashi ni te [さけ物、菓子ニて].

A sage-mono [提げ物] is a set of boxes that fit in a frame (often accompanied by an outer box, as seen below), designed for carrying food out of the house (on a picnic, for example).

It is unclear how many boxes were in Rikyū's set, though each box would have contained one type of kashi, and the guests would have passed each box around, so each person could take what he liked.

As for the kashi, a number of different things would have been offered (perhaps ranging from things like senbei [煎餅], to sliced fresh fruit, dried fruit, roasted chestnuts and mushrooms, and so on, perhaps even something like dengaku [田樂] -- things large enough that it would be easy to see and eat in the poor light provided by torches set up along the water), so the guests could help themselves. Everyone present would probably have been involved in the days activities, and so had little time to eat. Thus, in addition to wanting something to drink and some time to rest and relax, they may have been feeling a little hungry as well.

0 notes

Text

Nampō Roku, Book 2 (18): (1587) First Month, Fifth Day, Midday.

18) First Month, Fifth Day; Midday¹. Ne-no-hi [子日]².

◦ Three-mat room³.

◦ (Guests:) Hino dono [日野殿]⁴, Yūsai [幽齋]⁵, Sōkyū [宗久]⁶.

Sho [初]⁷.

﹆ In the toko, on an ashi-tsuke [足付]⁸ noshi-awabi [ノシアワヒ]⁹ ・ ne-matsu [根松]¹⁰.

◦ Kama unryū [釜 雲龍]¹¹.

◦ On the tana: ◦ in a fukube [フクベ], the charcoal¹²; ◦ habōki [羽帚]¹³.

▵ Shiru uguisu-na [汁 鶯ナ]¹⁴.

▵ Namasu tori [鱠 鳥]¹⁵.

▵ Kuro-me ・ kushi-awabi [黒メ・串鮑]¹⁶.

▵ Ao-ae・suzuna [青アヘ・スヽ菜]¹⁷.

▵ [Kashi] fu-no-yaki ・ shiitake [フノヤキ・椎茸]¹⁸.

[Go [後].]¹⁹

◦ Kokei Shun-fū [古溪 春風]²⁰.

◦ Chaire ryugo [茶入 リウコ]²¹.

◦ Tsutsui ori-tame [筒井 折タメ]²².

◦ Mizusashi Shigaraki [水指 シカラキ]²³.

◦ On the tana: ◦ hane [羽]²⁴.

_________________________

¹Shōgatsu itsu-ka, hiru [正月五日、晝].

The date was February 12, 1587, in the Gregorian calendar.

People usually spent the first four days alone with their family in their homes, and began to receive guests from the fifth.

Perhaps because members of his extended family were staying in his Ima-ichi machi residence, Rikyū borrowed Nambō Sōkei's Shū-un-an to receive this small group of friends.

²Ne-no-hi [子日].

This was the first Day of the Rat (the meaning of ne-no-hi) of the year.

◦ It was on this day that the Seven Grasses of Spring were collected (in the fields) and served during the meal.

◦ At this time, seedling pines were also collected, and displayed (and exchanged, as wishes for a long life).

◦ It was also the day when people gathered to enjoy group activities (things done for pleasure, such as playing games; and also chanoyu) for the first time in the year.

Rikyū observes these precedents during this chakai.

³Sanjō shiki [三疊敷].

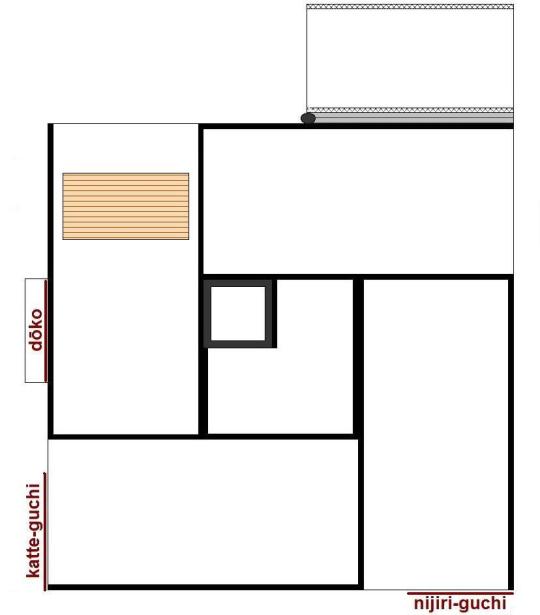

This refers to the Shū-un-an [集雲庵], Nambō Sōkei's official residence in the Nanshū-ji in Sakai, a short walk from Rikyū's Ima-ichi machi home.

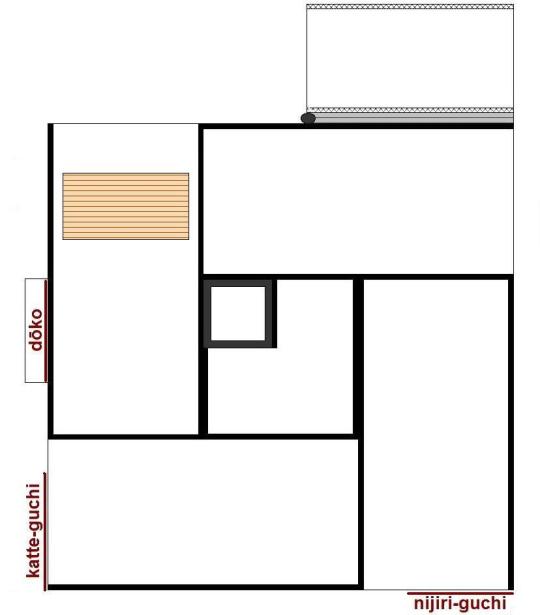

The Shū-un-an was a three-mat room, with the ro cut in the mat on which the lower guests sat. It was thus used as if it were a two-mat daime room.

This room contained the original tsuri-dana that was suspended in the left corner of the utensil mat, and so was known as the Shū-un-an-dana [集雲庵棚]. Rikyū appreciated the effect, and subsequently incorporated this kind of tana in his 2-mat rooms with a mukō-ro.

⁴Hino dono [日野殿].

This refers to Lord Hino Terusuke [日野輝資; 1555 ~ 1623], a kuge [公家]*, who, at the time of this chakai, was a gon-chūnagon [権中納言] or (supernumerary) Middle Counselor. Later this year (Tenshō 15 -- 1587) Lord Hino would be elevated to gon-dainagon [権大納言], (supernumerary) Major Counselor, and receive the senior grade of the Second Rank.

Lord Hino (who was born the same year that Jōō died) was also one of Rikyū's personal students. __________ *A court noble. Lord Hino was a hereditary nobleman (he was the 28th head of his house), rather than someone who had been raised up from the military caste (as was the case with most of the nobles surrounding Hideyoshi).

⁵Yūsai [幽齋].

This was the daimyō and scholar Hosokawa Fujitaka [細川藤孝; 1534 ~ 1610], who was known as Yūsai [幽齋] after his retirement*. He was originally a champion of the Ashikaga shōgunate, and later offered his allegiance to Oda Nobunaga and, subsequently, to Hideyoshi as Nobunaga’s successor†.

As a literary scholar Hosokawa Fujitaka’s fame is well known; and it was natural, and almost unavoidable, that they would be intimate colleagues during Rikyū’s years of service to Hideyoshi‡. ___________ *As a direct consequence of the events leading up to Nobunaga’s seppuku. Hosokawa Fujitaka's son and heir was married to the daughter of Akechi Mitsuhide, and so he should have joined Mitsuhide in his rebellion against Nobunaga -- this was the expected behavior in this kind of situation. Nevertheless, Hosokawa Fujitaka decided to shave his head and became nyūdō [入道], taking the name Yūsai; with which act he surrendered his status as a daimyō to his son (though, since he was still considered to be the head of the family, his decision to refuse to join Mitsuhide would obviate his son from being pressed into capitulating to Mitsuhide's demands).

†Hosokawa Fujitaka’s refusal to participate in the battle of Yamazaki probably helped to secure the victory for Hideyoshi, since it kept his retainers from participating on the side of Mitsuhide. As a result, though Fujitaka was technically retired, he was encouraged to remain active both politically and culturally, and in these capacities he served as an advisor to Hideyoshi to the end of his lifetime (for which Hideyoshi rewarded Fujitaka with an income and land in Yamashiro Province in 1586; which was doubled again in 1595).

Nevertheless, his allegiance to Hideyoshi aside, Fujitaka supported Tokugawa Ieyasu (perhaps due to a personal dislike for Ishida Mitsunari and his schemes -- one of which resulted in the death of Fujitaka’s son’s wife and his granddaughter), for which the family was honored by the Tokugawa bakufu.

‡Which support persisted even after Rikyū’s death: the reason why it was his son who went to the bank of the Yodo River to “see Rikyū off” was not because of a lack of affection or esteem on his part, but so that Fujitaka would be in a position to ward off any attacks (on either Rikyū, or Fujitaka’s own family) from Hideyoshi that this gesture may have precipitated.

⁶Sōkyū [宗久].

This was Imai Sōkyū [今井宗久; 1520 ~ 1593], who, together with Rikyū and Tsuda Sōkyū, was regarded as one of the three greatest chajin of the age.