#Ripley's Game

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

R I P L E Y (2024)

***Contains SPOILERS***

A review (of sorts, but more a rambling opinion piece that veers off the main subject occasionally).

So I've watched R I P L E Y (2024), all eight episodes of it. One word: Bravissimo!

As someone who loves the Ripliad series of novels by Patricia Highsmith immensely, and having watched all the Ripley film adaptations there are thus far — Plein Soleil aka Purple Noon (1960), The American Friend aka Der Amerikanische Freund (1977), The Talented Mr. Ripley (1999), Ripley's Game (2002), and Ripley Under Ground (2005) — I went into this new series (released on Netflix on April 4th) with expectations…

Not high, for I've learned it's never good to have high expectations or you'll more than likely just be setting yourself up for disappointment…but with expectations all the same!

Thus far, my favourite Ripley film adaptation had been 2002's Ripley's Game starring John Malkovich as an older Ripley. Had been. Until this series that is! I still love Ripley's Game a lot of course! (heh!) And there really should be no comparison given it's two different mediums and the two Ripleys are portrayed from different times of the character's life.

So saying, this new series definitely sets a new standard for a Ripley adaptation! And as someone who love the books a lot, I'm glad this series is very closely adapted from the first book!

The decision to go for a black and white cinematography, I was skeptical about that at first but after looking at the trailers and reading on the director's reasoning for going B & W with this, I can understand why, and generally agree with his decision.

Though at times, especially when looking at the wonderful interior sets, I'll be wishing I could see it in all its colour glory and thinking what a waste it was not to have it in colour, but that is but a minor hitch, for the B & W cinematography is done with superb mastery and skill, and it's hard to find fault with going this route. And it does contribute to getting into the film noir feel from films of yesteryear.

On the actors, I was skeptical on Andrew Scott as Ripley at first, but I'm happy to say he has proven me wrong and his Ripley, while not as young as Ripley should be at the start of the novel series, is one that is characterised the closest, and if Showtime/Netflix has any plans to adapt the rest of the novels, Scott will be perfect as an older Ripley, I think!

Maybe that was/is the plan…that's why Scott was chosen even though age wise, he doesn't quite fit in the beginning…one can hope! (heh!)

Moving on, just a brief rambling on the other main actors/characters because I'm getting tired:

Love Dakota Fanning as Marge Sherwood, she was exactly how I imagined Marge to be as I read the (first) book. A superb performance by Fanning I'd say!

Johnny Flynn as Dickie Greenleaf was underwhelming for me partly because in my eyes, Jude Law was/is the perfect Dickie (even if his — Law's — American accent was/is questionable), but partly also because I find Flynn is lacking charisma (sorry, Flynn fans!), I didn't get the sense of what was so fascinating about this Dickie that Ripley would be so enamoured with him or his lifestyle, enough to kill for it.

Perhaps the fault lies partly with the script too for I felt we the audience didn't get to see more of what drew Ripley to Dickie, besides his obvious wealth and status.

Eliot Sumner as Freddie Miles. Now this was the character that underwent the most drastic change as compared to the book and the 1999 The Talented Mr. Ripley film adaptation. In both the book and the 1999 film, Freddie was described (and portrayed to perfection by Philip Seymour Hoffman in my opinion) as an American with carrot-red hair, stocky, loud and all round obnoxious from miles away sort.

2024 Freddie is slim-built, androgynous looking, with a cherub face and British…he's practically a whole different character except in name.

As such, it's unfair to compare I guess, but having envisioned Freddie as described in the book for so long, helped along by PSH's award-worthy performance, I'll just say this is not the Freddie for me.

But, that doesn't mean Sumner's Freddie was bad. In terms of being almost a foil to Ripley, Sumner's Freddie is still quite effectively annoying.

Special mentions to Maurizio Lombardi and Margherita Buy as Inspector Ravini and Signor(in)a Buffi (Ripley's landlady) respectively! I enjoyed watching these two characters.

Also a special mention to Lucio (Signor(in)a Buffi's cat), who, had it been able to speak, Ripley would certainly have silenced! (heh!)

Last but not least, a special mention to John Malkovich as Reeves Minot.

I was so excited when I first saw Malkovich in the trailer because not only is his casting a nice tribute to his turn as Tom Ripley in Ripley's Game (2002), I thought he would be playing Herbert Greenleaf at first, but he turned out to be playing Reeves Minot! Even better! Gives more hope that new seasons of R I P L E Y (2024) may happen!

Those who have read the books will know that Reeves Minot is a recurring character in the later books — I can't really remember how many exactly, it's been some time since I last read them (and I should again!).

To sum up, I did enjoy this series tremendously and will definitely rewatch many times to come, and I hope we'll get further adaptations of the other books with the same standards as set for this one!

P.S.: I've seen a few people mention “this (R I P L E Y) is like Saltburn!”. I never heard of the film Saltburn before looking at some opinion pieces, but after looking it up, dare I say, Saltburn ripped off the Ripliad stories and its characters (the Ripliad books first came out in the 1950s) and I think it's more appropriate to say “Saltburn is like Ripley”!

#Dake Rambles#Ripley 2024#Ripley Netflix#Andrew Scott#John Malkovich#Ripley's Game#The Talented Mr Ripley

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ripley's Game (2002), directed by Liliana Cavani

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

'I was about three episodes into the Netflix Ripley mini-series when I decided to read the Patricia Highsmith novel it was based on. A question about the setting of the mini-series sparked my interest in the novel. The series claimed to have been set in 1961, but it gave me feelings of post-war Italy, maybe 1949 or so.

The answer is that the Highsmith novel was published in 1955, which means that it captures a cultural sense of the mid-1950s. 1961 is not too far off from that.

By now, everyone should know that the title character, Tom Ripley, is a sociopath. The word “sociopathy” is not used in either presentation. The acting of Andrew Scott in the Netflix series captures the essence of a sociopath. Scott plays Ripley as awkward, autitistic, and anhedonic — Scott’s Ripley is one off-beat, creepy dude.

The opening scene in the Netflix series is a perfect representation of the sociopath in action. On the spur of the moment, Ripley intercepts a letter from a postal carrier by acting as if he is going into an apartment. He then uses the letter to scam the sender to send a replacement check to him by posing as a bill collector. He has to abandon the cashing of the check when he senses that he is about to be unmasked. The sequence portrays the opportunism of a lot of crime, which has to be the domain of sociopaths who do not hesitate a moment out of guilt or conscience.

In contrast, it doesn’t seem that Highsmith had a developed knowledge of sociopathy. Her Ripley is weirdly bipolar. He transitions from bouts of manic exuberance about his plans to bitter resentment about the injustices he feels he has been subjected to. Highsmith’s Ripley is not nearly as disciplined as the Netflix Ripley. In Highsmith’s novel, for example, Ripley just collects the checks from his victims without ever trying to cash them.

This could reflect the development of the idea of the sociopath/psychopath as a fictional type. We have had decades of tropes and caricatures about high-functioning sociopaths that Highsmith didn’t have. While the idea of psychopathy was introduced in the 1950s, sociopathy had been known since the 1930s.[3] One source describes the history of sociopathy as follows:

While psychopathy was yet to make its premiere in the DSM, sociopathic personality disturbance, or sociopathy, was included in the DSM-I. Sociopathy was developed in the 1930s and consisted of antisocial and dissocial reactions and sexual deviation (Pickersgill, 2012). Differences and similarities existed between sociopathic personality disorder and psychopathy, however psychopathy would not have its own category in the DSM until the publication of the DSM III. In DSM-I, sociopathic personality disturbance, antisocial reaction was defined as a diagnosis for chronically antisocial individuals who didn’t profit from experience or punishment and maintained no real loyalties (Pickersgill, 2012).

This could explain why Tom Ripley is not the smooth and charming manipulator we expect to see in more recent stories involving psychopaths.

It might also explain why Highsmith edges around the homosexual issue.

It seems clear from Highsmith’s novel that Tom is “same-sex attracted.” He is a young man (around 24 or 25) who has been “kept” by a wealthier male who treats him as a possession. Highsmith shares that Tom runs in homosexual circles and poses as a homosexual but is a virgin:

His mind went back to certain groups of people he had known in New York, known and dropped finally, all of them, but he regretted now having ever known them. They had taken him up because he amused them, but he had never had anything to do with any of them! When a couple of them had made a pass at him, he had rejected them — though he remembered how he had tried to make it up to them later by getting ice for their drinks, dropping them off in taxis when it was out of his way, because he had been afraid they would start to dislike him. He’d been an ass! And he remembered, too, the humiliating moment when Vic Simmons had said, Oh, for Christ sake, Tommie, shut up! when he had said to a group of people, for perhaps the third or fourth time in Vic’s presence, “I can’t make up my mind whether I like men or women, so I’m thinking of giving them both up.” Tom had used to pretend he was going to an analyst, because everybody else was going to an analyst, and he had used to spin wildly funny stories about his sessions with his analyst to amuse people at parties, and the line about giving up men and women both had always been good for a laugh, the way he delivered it, until Vic had told him for Christ sake to shut up, and after that Tom had never said it again and never mentioned his analyst again, either. As a matter of fact, there was a lot of truth in it, Tom thought. As people went, he was one of the most innocent and clean-minded he had ever known. That was the irony of this situation with Dickie.

Highsmith, Patricia. The Talented Mr. Ripley (pp. 79–80). W. W. Norton & Company. Kindle Edition.

On the other hand, everyone who knows Tom suspects that he is a homosexual. He is fixated on Dickie. He becomes jealous when he sees Dickie with his girlfriend, Marge Sherwood.

In the Netflix series, this backstory is not revealed. There are clues that he might be homosexual and attracted to Dickie, such as the weird scene where he dresses as Dickie, which prompts Dickie to tell Tom that he is not “queer.”

In the book, Tom’s two murders occur after homosexuality is derided. Before Tom murders Dickie, the two men are watching the gymnastics of a group of men that Dickie describes as “daffodils” by quoting lines from a poem. This sets Tom off on a chain of thinking about taking over Dickie’s life after he remembers Aunt Dottie describing him as a “sissy.” Later, Tom justifies killing Freddie Miles for accusing Dickie of “sexual deviation”:

The gin only intensified the same thoughts he had had. He stood looking down at Freddie’s long, heavy body in the polo coat that was crumpled under him, that he hadn’t the energy or the heart to straighten out, though it annoyed him, and thinking how sad, stupid, clumsy, dangerous, and unnecessary his death had been, and how brutally unfair to Freddie. Of course, one could loathe Freddie, too. A selfish, stupid bastard who had sneered at one of his best friends — Dickie certainly was one of his best friends — just because he suspected him of sexual deviation. Tom laughed at that phrase “sexual deviation.” Where was the sex? Where was the deviation? He looked at Freddie and said low and bitterly: “Freddie Miles, you’re a victim of your own dirty mind.”

Highsmith, Patricia. The Talented Mr. Ripley (pp. 140–141). W. W. Norton & Company. Kindle Edition.

However, Freddie didn’t make such an accusation. Tom killed him because Freddie had noticed him wearing Dickie’s shoes and Dickie’s bracelet.

In contrast, the Netflix series takes the Freddie character toward gingercide. In the novel, Freddie is a redhead, which disgusts Ripley. Highsmith writes:

The American’s name was Freddie Miles. Tom thought he was hideous. Tom hated red hair, especially this kind of carrot-red hair with white skin and freckles.

Highsmith, Patricia. The Talented Mr. Ripley (p. 64). W. W. Norton & Company. Kindle Edition.

And who doesn’t feel this way?

A lot of people, apparently, given the disappearance of soulless day-walkers from popular media.

In the Netflix series, Freddie is played by a former (or current) female — the actor is Elliott Summer, who, as it turns out, is Sting’s daughter. The actor who plays Freddie is obviously a woman trying to pass as a man, which means the character is obviously a woman trying to pass as a man, but nothing is ever made of this.

It was like Chekov’s gun was left hanging on the wall.

We are in a Heisenberg’s Trans situation. Is the fact that Freddie is trans part of the story, or are we supposed to pretend that the woman playing the man is a man in both the story and the real world?

Was the character/actor's sexual confusion supposed to be a stand-in for Ripley’s confusion? Are we now supposed to read the actor’s biographies as a metatext to understand the film?

I hope not.

But what does it mean? I don’t have a clue.

The conclusion was another difference between the two. In the novel, Ripley gets away clean. No one ever finds a photo of Dickie Greenleaf and realizes that they’ve been hornswoggled, which, honestly, is strange in retrospect. Certainly, photos were common enough in the 1950s for police to ask the family for a photo to show people in their search for Dickie. The subject is never raised, and the reader may never consider it.

In contrast, in the Netflix series, Tom dives into another identity with the help of John Malkovich, who played Tom Ripley in Ripley’s Game, a movie based on a later Ripley novel.

There are some fascinating details in both the novel and the series, but the characters never resonated with me. In both vehicles, the character of Tom Ripley is not redeemed by intelligence, cleverness, or charisma. In both, he reacts to circumstances. In the novel, the killing of Dickie Greeleaf is deliberate in the sense of being premeditated, but there is no deliberation about the crime or how Tom will escape. In the series, it is an emotional reaction that is thoroughly botched and results in Ripley nearly killing himself. Watching Ripley extemporize a cover-up, which he botched badly, was painful.

In the series, there are moments when Ripley almost displays the criminal competence that I assume he cultivates during the next four books. After that flash of competence, he quickly returns to form, doing imprudent and pathological things. We might be fascinated with his performance if he were competent, but he is such a klutz.

So, what is the enduring appeal of this book? There have been three Ripley movies or series, and the book has been in print for nearly 70 years. Why did I read it? Ripley is an evil man who deserves to have been captured and executed.

Perhaps, the answer is that — God help us — we are fascinated by evil. Maybe we all have an inner sociopath who is begging to be let out to play.'

#Patricia Highsmith#The Talented Mr Ripley#Ripley#Netflix#Freddie Miles#Dickie Greenleaf#Marge Sherwood#Eliot Sumner#John Malkovich#Ripley's Game#Andrew Scott

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

LMAO ??????? Welcome to the Resistance, [checks notes] Tom Ripley!!!!!

#you can tell highsmith by this book just likes the guy.#books#reading#ripliad#tom ripley#ripley's game#patricia highsmith#heloise plisson

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Reading Challenge 2024 Book 9/24: Ripley's Game by Patricia Highsmith Rating: 4.25/5

Tom Ripley is still living in France with his wife, and things are very stable. There's no reason for Ripley to get into mischief at all. So he makes some for himself on a lark, dragging a near-random acquaintance into a life of crime as an experiment.

This is my favorite Ripley book so far. It's a good balance of tone between the first two books. Ripley runs into challenges that push him and create risk, unlike the second book, but things never get to the queasy intensity of the original, so the plot is more fun than anxiety-inducing.

As a novel, the original is probably the best because it has the most complicated character study. Everybody knows what Ripley is by book 3. However, I still enjoy his attempts to find people who think and feel like him. He does the most terrible, absurd, disturbing things without blinking an eye and expects his companions to respond similarly. Of course, as he notes himself, "us to Tom was only Tom Ripley."

I told my friend he has a kind of Hannibal and Will dynamic with his victim in this one. That's probably the real reason I like it most, lol.

#reading challenge 2024#ripley's game#patricia highsmith#okay that's it for the april books#only 3 more to write about and i'll be caught up

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

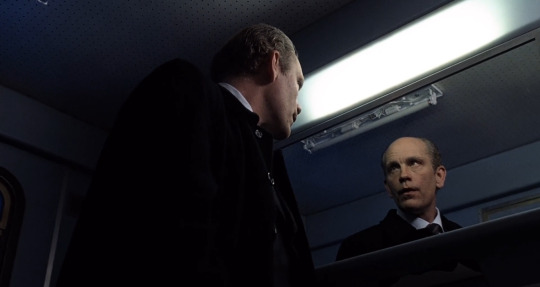

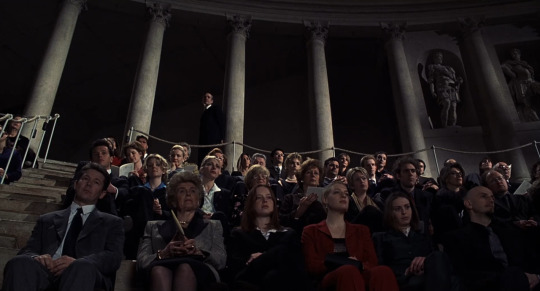

Dougray Scott and John Malkovich in Ripley's Game (Liliana Cavani, 2002)

Cast: John Malkovich, Dougray Scott, Ray Winstone, Lena Heady, Chiara Caselli, Sam Blitz, Paolo Paoloni, Evelina Meghnagi, Lutz Winde, Wilfred Xander. Screenplay: Charles McKeown, Liliana Cavani, based on a novel by Patricia Highsmith. Cinematography: Alfio Contini. Production design: Francesco Frigeri. Film editing: Jon Harris. Music: Ennio Morricone.

Patricia Highsmith's novel Ripley's Game was filmed before, by Wim Wenders, as The American Friend (1977), a movie that's more Wenders than Highsmith. When I saw that version, as witty and accomplished as it is, I commented that it made me want to see the story done more slickly and conventionally, which is exactly what Liliana Cavani does in her version. The novel was Patricia Highsmith's third about the chameleonic and psychotic Tom Ripley. Most of us have seen one or more of the versions of her first Ripley novel, The Talented Mr. Ripley, whether in the versions filmed by René Clément (as Plein Soleil or Purple Noon) in 1960, by Anthony Minghella (under the original title) in 1999, or by Steven Zaillian (as Ripley) in the TV series in 2023. But few of us have seen the film version of the intermediate novel, Ripley Under Ground, a critical and commercial failure directed by Roger Spottiswoode in 2005, in which we learn that Ripley has flourished on his ill-gotten gains and is further enriching himself as a dealer in art forgeries. So Cavani's Ripley's Game begins rather abruptly, with Ripley (John Malkovich) engaged in a shady transaction and yet another murder. But more important, the character of Ripley has changed: Malkovich's Ripley doesn't have the specious charm of the ones played by Alain Delon, Matt Damon, or Andrew Scott -- maybe because he doesn't need it, being already on top of the world. This lack of charm and vulnerability is a problem for the film to overcome, especially when it invests some of those traits in the film's chief victim, Jonathan Trevanny (Dougray Scott). Trevanny should elicit our sympathy: He's dying of leukemia and has an attractive wife (Lena Heady) and small son (Sam Blitz), and he desperately wants to leave them well off after his death. Unfortunately, Ripley overhears Trevanny scoffing at Ripley's wealth and taste at a dinner party, and immediately sets out to get even. What follows is the familiar Ripleyan snarl of schemes and murders. And in the end, it demonstrates what was wrong with my reaction to Wenders's version: Slickness and convention aren't enough to make a really good film, sometimes what you need is an auteur.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Die postapokalyptische, aber farbenfrohe Leseliste:

Der schöne Antonio ist der Schwarm aller Frauen von Catania und gilt als großer Weiberheld, weshalb die Sizilianer automatisch davon ausgehen, daß er auch politischen Einfluss auf die Mächtigen im Mussolini-Staat hat. Bis sich herausstellt, daß es sich um einen schlimmen Fall von sexueller Hochstapelei handelt. Ein sizilianischer Klassiker von Antonio Brancati, der nicht so viel von seinen Landsleuten zu halten scheint.

Der brillante Rotherweird-Erfinder Andrew Caldecott entführt uns in ein zweiteiliges postapokalyptisches Abenteuer mit tollen Drogen, in denen Kunstwerke erlebt werden können, Figuren aus Alice im Wunderland, wunderbaren Steampunkt-Flugschiffen und allerlei schönen Erfindungen sonst. Zwei Clans/Firmen streiten um, das wenige, was von der Welt übrig ist und trotz prächtiger Schurken ist schwer zu sagen, wer die guten und wer die Bösen sind. Ist wieder ganz fabelhaft.

Wie es mit Ripley weitergeht: Er langweilt sich ein wenig auf seinem französischen Landsitz und stiftet spaßeshalber einen unbescholtenen Bekannten an, einen Auftragsmord zu übernehmen. Was soll er auch sonst machen?

Mungo Parks historische Afrikareisen, von denen zumindest die zweite als grandiosis gescheitert gewertet werden muss, bilden die Grundlage für T. C. Boyles mit den historischen Fakten relativ unbefangen umgehenden Roman Water Music. Es ist ein Buch von denkbar schlechtestem Geschmack und ist von widerlichen, schmutzigen Gedanken, und der Titel wird Händel sich im Grabe rumdrehen lassen, sagt Salman Rushdie. Das wollte ich schon lange mal wieder lesen, um zu schauen, ob es mir immer noch so gut gefällt. Tut es.

Im vierten Buch der Hitchhiker-Trilogie kehrt Arthur Dent unerwartet auf die im ersten Teil vernichtete Erde zurück. Die Delfine sind verschwunden und bedanken sich für all den Fisch: dafür erscheint Ford Prefects Artikel über die Erde endlich komplett im Reiseführer. Es ist wieder einmal alles sehr merkwürdig.

Und weil es ja schon 3 Bücher her war seit dem letzten postapokalyptischem Unrechtsstaat, las ich noch einmal Jasper Ffordes Shades of Grey (nicht zu verwechseln...). Hier bestimmt die Farbwahrnehmung den sozialen Status. Das ist auch sehr merkwürdig, dies und alle anderen Regelungen dürfen aber nicht hinterfragt werden, sonst kommt es zu schrecklichen Schwanattacken oder schlimmerem. Das musste ich jetzt doch etwas auffrischen, weil die außerordentlich langerwartete Fortsetzung nach 12 jahren nun tatsächlich erschienen ist:

Sie macht alles ein ganz kleines bisschen nachvollziehbarer. Ich kann es Ihnen jetzt trotzdem nicht sinnvoll zusammenfassen.

#Buch gelesen#Antonio Brancati#Schöner Antonio#Andrew Caldecott#Momenticon#Simul#Patricia Highsmith#Ripley's Game#T. C. Boyle#Water Music#Douglas Adams#So Long and Thanks for All the Fish#Jasper Fforde#Shades of Grey#Red Side Story

0 notes

Text

0 notes

Text

tbf jonathan at points seems to think this is a good thing as well

as many people have said before, when i "stan" a "problematic" "character", i condone every single one of their choices. without a hint of irony. i think it's good that tom ripley trips up annoying children in public places and forces a man to get involved in a mafia killing because he was once rude to him at a party

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

R I P L E Y (2024) | Teaser Trailer | 04.04.24

#Thought shelved since COVID struck but looks like it pulled through!#Though it's branded under Netflix#And most shows under them suck!#But…but…it's#Ripley! One of my fave book series!#Cautiously hopeful?#Ripley 2024#Andrew Scott#John Malkovich#Hey! A tribute casting?#Malkovich played Ripley in#Ripley's Game#(2002)#Johnny Flynn#The Talented Mr Ripley

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Aliens: Alien 2 (Square, 1987)

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

'Patricia Highsmith’s 1955 novel The Talented Mr. Ripley has been made into two sterling films: 1960’s Plein soleil (Purple Noon) starring Alain Delon, and 1999’s The Talented Mr. Ripley headlined by Matt Damon, Jude Law, and Gwyneth Paltrow. Nonetheless, Netflix’s new Ripley stands head and shoulders above its predecessors (and most modern TV offerings) as an adaptation par excellence.

Over the course of its eight exhilarating episodes, all of them shot in breathtaking black-and-white by Oscar-winning cinematographer Robert Elswit (There Will Be Blood), this stellar thriller exhibits a formal precision, dexterity, and majesty that electrifies its tale of a small-time New York City grifter named Tom Ripley (a phenomenal Andrew Scott) who attempts to remake himself in Italy by slipping into the life of wealthy playboy Dickie Greenleaf (Johnny Flynn). Cunning cons and brutal murder ensue, all of them dramatized by the show with a suspenseful elegance and psychological complexity that does justice to its source material—and, in certain cases, adds new, incisive wrinkles to the oft-told tale.

Ripley is, quite simply, a small-screen masterpiece, and credit for its triumph goes, first and foremost, to writer/director Steven Zaillian. In the three decades since he won the Best Adapted Screenplay Oscar for Schindler’s List, the 71-year-old has collaborated with a who’s who of Hollywood greats, from Brian De Palma (Mission: Impossible) and Sydney Pollack (The Interpreter) to Ridley Scott (Hannibal, American Gangster, Exodus: Gods and Kings), David Fincher (The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo) and Martin Scorsese (Gangs of New York, The Irishman).

Along the way, he’s additionally penned the excellent Moneyball, helmed three of his own feature scripts (including the fantastic Searching for Bobby Fischer), and spearheaded HBO’s acclaimed The Night Of. Even with such a formidable résumé, however, Zaillian’s latest may be his finest achievement to date. Its scintillating style wholly wedded to its storytelling, and its meticulousness central to its simmering undercurrent of sociopathic madness, it’s a work of controlled Machiavellian malevolence, rife with tension and rich in detail and depth.

Guided by Zaillian’s virtuosic hand, Ripley is the rare example of genuine auteurist television, even as it simultaneously stands as a testament to the fact that projects are more likely to be great when they’re made by a collection of great artists. Now available on the streaming platform, it’s an early contender for end-of-year accolades. Consequently, we were elated to speak with Zaillian about the challenges of making his sensational series, collaborating with Scott and Elswit, and the enduring appeal of Highsmith’s famous novel.

Ripley is better directed than 99 percent of modern television, to a great degree because it’s been actually directed, with personality, flair, and guiding motifs and techniques. Was there any pushback to your approach, given that TV generally wants formal style to take a backseat to storytelling?

No, there was no pushback. The style that the show became… I started with the writing, I can’t write anything without imagining it. That being said, things obviously change when you’re shooting, and motifs come up and the style gets set at a certain point. But the whole time we were shooting, basically all anybody is seeing are dailies. It’s hard to tell from dailies what’s going on, you know [laughs]? Most people at the studios didn’t see anything until it was edited. So I had this great freedom to do what I wanted in terms of its look, and I spent a lot of time doing it. It was important to me that it looked good and felt good in terms of its tone, and most of the people who came to this come from film, and we approached it as one long movie.

Is the writing process different when you’re writing for yourself, versus another director?

I don’t write any differently. As I mentioned, I can’t write it without seeing it, so whether I’m writing for myself or someone else, it’s the same process. I don’t ever put in, close-up here or wide shot there. However, I do see it, so when I’m making my shot lists, I’ve already done it once before when I was writing it. But in terms of writing in a different way if someone else is going to direct it, no.

What made you want to tackle The Talented Mr. Ripley, which has been adapted multiple times before?

I’ve been wanting to do it since I read it, which I think was probably back in the ’80s. Certainly after Purple Noon but before The Talented Mr. Ripley movies. I saw it in a certain way and I wanted to try that, so when this opportunity came up, I took it. I just think it’s one of the great characters and one of the great stories that can be told over and over again.

What is it about the novel that’s allowed it to endure so powerfully over the past 70 years? Despite its age, it feels extremely relevant in today’s socio-political climate.

The idea of a character who becomes somebody else is something that happens all the time, today and throughout history. We’re strangely fascinated with it. I mean, it comes up all the time! There are articles—one that comes to mind from a few months ago was called “The Talented Mr. Santos.” I think this particular character is fascinating, certainly to me and I hope to other people. And the style of it—and I don’t mean the photographic style, but the style of the story—comes from Highsmith, where she finds these kinds of extraordinary things happening in normal circumstances with normal people. It’s something she’s well known for, and is something which I feel we can all relate to.

You’ve directed three feature films, but none since 2006. As a director, what compelled you to segue to television?

It’s the way things go. It’s strange to say that it’s easier to get a television show done than a movie, but it seems to be true, at least with the kinds of movies that I want to make. [TV] is a lot harder and it takes a lot longer, and I long for the days and the chance to make a movie again. I’m hoping that that’s what I’m going to do next, only because it won’t consume years and years of my time [laughs]. I can do the same thing and not have it take four or five years.

At what point did you decide to shoot the entire series in black and white, and what was your thinking behind that creative decision?

It started with the writing; that’s how I imagined it. Why, I don’t know. Maybe because of the period. I did want it to not feel like a postcard, and Italy, if shot in bright vibrant colors in the summertime with blue skies, can feel that way. I felt that this was a more dark and sinister story, not unlike a film noir story, and so black and white seemed to be the natural choice.

Yet despite that monochromatic scheme, you didn’t lose the classical beauty and romance of Italy.

You can’t lose that in Rome—it’s impossible [laughs]. Nor did I want to. But that being said, even a familiar place to people—like, well, you don’t really see the Coliseum except when he’s driving around with a corpse in the car—I didn’t want those places to be front and center. I wanted the backstreets of Rome more than the boulevards. Naples and Palermo are both really interesting places that photograph wonderfully in black and white.

But again, part of the story does take place on the Amalfi Coast, and that’s the place that’s hard to make sinister in color. When you have the aqua blue water and the bright sun, it’s tough. Luckily, we were at least filming there in the fall, so we didn’t have the brunt of tourism or those postcard shots, which certainly helped.

Robert Elswit shot the pilot of The Night Of and the entirety of Ripley. What is it about him as a cinematographer that makes your collaboration work so well?

It’s many things. Obviously, he’s really talented. He shoots beautiful movies. And we get along really well. He’s very intrepid—he’ll do anything, and go anywhere, and work crazy hours. He’s a workhouse in that regard. This took that kind of person. We shot for 160 days in Italy, with a one week break in the middle, and that’s tough on anybody. He just loved the idea of shooting it in black and white, and he’s a master with lighting, as you can tell when you watch it. It’s a great collaboration, we have.

The series is dominated by shots of Tom at a distance, framed in long claustrophobic hallways and by constricting architecture (such as the stairs of Dickie’s home in Atrani). Was it difficult to find the locations you needed for that visual style?

That’s one of those things when you talk about motifs… yes, I wrote a scene where Tom climbs a lot of steps, but that was a place that [production designer] David Gropman and I found. We drove from Salerno to Sorrento, all the way up the coast, and this little town called Atrani that has 800 people had those stairs, and I was fascinated by them. I said to David, it looks like an M.C. Escher drawing, and I found out much later that [Escher] had actually lived there and had drawn those very stairs. So that’s where it started. Then, wherever we went, we encountered stairs, and that’s when it started becoming a motif.

You shoot Tom’s two murders (and their aftermaths) in long, methodical sequences. Why was it important to stage those in such detail?

I had a little note scribbled on a Post-it when I started this saying, “It’s easier to kill somebody than it is to get rid of the body.” I wanted to show that. Even getting rid of a body that’s laying down in a little boat is hard to get rid of. I thought, this could be an opportunity to try something that I’d like to, which is showing these things in what feels like real time, and how difficult it is. I thought it was interesting, I thought it was entertaining, and I thought it was something I’d wanted to do from the beginning. So in the scripts, in episodes three and five, those sequences are about 35 pages long.

How did you settle on Andrew Scott for Tom?

I’d only seen him in three things, and one of them, I didn’t even see him; I’d only heard him—that was in a movie called Locke in which he did not appear, but he was a voice on the telephone. He created a really interesting character with just his voice. That was the first time I saw anything he was in. Then his Moriarty [in Sherlock] and Fleabag. With those three things, I felt he could do anything. They were so different from each other that I felt, that’s Tom. He’s got the range to play Tom.

Often in Ripley, the most important aspect of a given scene is what’s taking place beneath what’s being said aloud. From a writer’s standpoint, how do you tackle such undercurrents?

That’s always been important to me in the writing—to know, what is the point of the scene? Is it a piece of dialogue, is it an action, or is it the moments between the dialogue? Often, that’s where it is for me. Like you say, someone is lying and the other person knows they’re lying, and they play this kind of game with each other—that is the point of the scene! So those moments in-between the dialogue are what’s important. I spend a lot of time with that, and the actors got that, and they’re smart and they’re good and they like doing that. So in those instances, that was what was going on.

John Malkovich makes a late, brief appearance as Reeves, which is both a sly shout-out to Ripley’s Game (which he starred in, as Tom) and a tantalizing suggestion of future seasons. Was Malkovich’s participation always part of the plan—and was his cameo designed to keep the door open for a follow-up?

Both of those things are true. I wrote to him and explained that I’d like him to consider doing this. It’s very short, it’s just a couple of days, but maybe it’s a fun idea. And he thought it was and came to Venice and did it.

Yes, I was also thinking that if there’s another season, this character appears in the next two Highsmith books about Ripley, and he’s a great character. He does not appear in The Talented Mr. Ripley book; he doesn’t appear until the second book. But yeah, if that ever happens, I hope he’ll do it. Because he’s perfect for it.'

#Steven Zaillian#Robert Elswit#Patricia Highsmith#Matt Damon#Jude Law#Gwyneth Paltrow#Ripley#The Talented Mr Ripley#Andrew Scott#Locke#Sherlock#Fleabag#John Malkovich#Reeves Minot#Ripley's Game#David Gropman#Atrani#Moriarty#Netflix

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jonathan already had a pretty perverse streak before Tom sunk his talons into him, seeing as he thinks there's something specifically Catholic about his wife objecting to him becoming a hit man.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

#rhea ripley#wwe#wwe survivor series#wwe war games#survivor series#war games#survivor series war games#my edits#my gifs#wweedit

787 notes

·

View notes

Text

#rhea ripley#demi bennett#wwe#survivor series#survivor series: war games#war games#wweedit#wwe gifs#*gifs

776 notes

·

View notes

Text

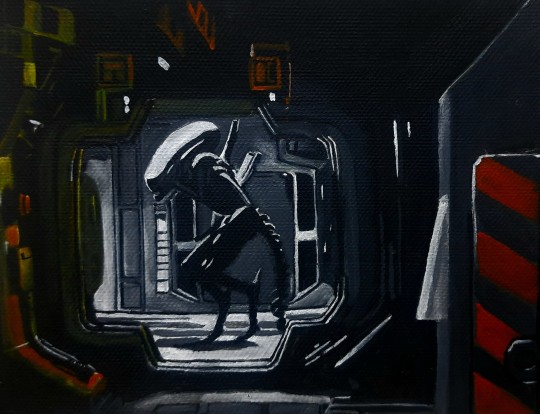

This is my first time dipping into horror art. This piece was more difficult than I expected. There were a lot symmetrical structures which I found challenging to paint while maintaining a proper contrast between light and dark. In the end, I think it turned out alright

#horror#horror art#horror aesthetic#horror painting#my art#my artwork#thriller#horror games#horror movies#creepy art#xenomorph#alien#ellen ripley#alien isolation

2K notes

·

View notes