#RAF Kenley

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Video

1940 RAF Hawker Hurricane Mk1 V7497 G-HRLI SD-X No 501 Squadron by Chris Murkin Via Flickr: 1940 RAF Hawker Hurricane Mk1 V7497 G-HRLI SD-X No 501 Squadron The aircraft has been painted in the colours SD-X No 501 squadron RAuxAF Based at RAF Kenley UK Photo taken at the Imperial War Museum Duxford Cambridgeshire 18th March 2025 YYB_2115

#Air#Vintage#History#RAF#Hawker#Hurricane#Mk1#V7497#G-HRLI#41H-136172#War#Museum#Duxford#Cambridgeshire#UK#Nikon#Display#Military#Warbird#WWII#Warbirds#PLANE#Photo#Prop#Fighter#Flying#AIRCRAFT#Aeroplane#Attack#Air-Legend

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

New Zealand ace Bill Crawford-Compton with his Spitfire at RAF Kenley, 1942.

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

15 August 1940. Pilot of 64 Squadron RAF running towards his Spitfire Mk Ia as the Squadron is scrambled at Kenley – Battle of Britain.

@ron_eisele via Twitter

75 notes

·

View notes

Text

I have the house to myself tomorrow (!!) and I’m planning to cuddle my dogs, do a bit of writing, and have a Powell & Pressburger marathon. Join in the sleepover vibe and send me some questions maybe? 💕 Freestyle it or choose from:

✨ some general writing asks

✨ OC asks

✨ shippy asks (heads up: some of these are NSFW)

(If you haven’t been introduced to my OCs yet, there is a list of my faves below the cut!)

Louise Johnson

Lou was born and raised in the Kent countryside, but moves to London to work as a secretary before the war. After a year or so in the WAAF, she is recruited into the Special Operations Executive and dropped into occupied France as a special agent. A Band of Brothers OC, paired with Floyd Talbert, but has also been cloned into the Masters of the Air universe, where she meets a certain Rosie Rosenthal…

Emily Johnson

Emily is Lou’s older sister. She is solemn and shy, a contrast to Lou’s boldness and wicked sense of humour, but when the sisters reconcile they find they share more than they thought.

Ruth Lawrence

During the Battle of Britain, Ruth worked alongside Louise as a WAAF plotter at RAF Kenley, but left the service when she got married. She lives with her husband Tim in London.

Virginia Harris

Vee, as she is known to her friends, is the life and soul of the party. A nursing officer, she works in a RAF hospital in Scotland, alongside her close friend and fellow nurse Ada Monroe.

John Ferraby

Half-French, half-English, John is a lieutenant in the Royal Signals and an SOE wireless operator. He is teamed up with Louise prior to D-Day.

Rosie Clifton

The Honourable Rosalie Clifton, to give her full title, is the only daughter in a wealthy English family. Her father and brothers love parties, fast cars, and drinking; Rosie does not. But she does share their love of aircraft and flying. During the war Rosie joins the Air Transport Auxiliary. A Masters of the Air OC.

#floydmtalbert sleepover weekend#Askbox memes#You may have to specify BoB Lou or MotA Lou on some of these btw...

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

1943 08 17 Defence of Darwin - Norman Clifford

The date is 17 August, 1943, time 4.30pm and the crew of the Japanese Ki-46II “Dinah” had failed in their mission to photograph Darwin Harbour in Northern Australia. Flying the Spitfire Vc (Tropical) is Australia’s leading WWII fighter pilot Clive Caldwell, Wing Commander of No. 1 Fighter Wing RAAF, the defenders of Darwin during 1943.The “Dinah” is from the reconnaissance element of the 202 Kokutai “Zero” fighter unit of the Japanese Naval Air Force based on the island of Timor. Three “Dinahs” of the Japanese Army Air Force had failed to return from reconnaissance trip over Darwin that morning. All had been lost to 457 Squadron.Born in 1910, Caldwell enlisted in the permanent RAAF at the outbreak of war. When he was called up for service in February, 1940, not only did he have to lower his age (he was “too old” for pilot training), he discovered he was destined to be an instructor! Caldwell, wishing only to be a fighter pilot, promptly resigned, and rejoined the Empire Training Scheme in Sydney on May 6.Becoming operational in the middle East in May, 1941 as a pilot officer with 250 Squadron RAF, Caldwell flew P-40 Tomahawks. He experienced a rapid rise in the hard and dangerous world of the fighter pilot, becoming the Squadron Leader of the famous 112 “Shark” Squadron RAF on 6 January, 1942.Caldwell was the first Empire Air training Scheme pilot to achieve squadron command. Soon after having done so, he became the most successful pilot of the Desert Air Force with a total of 20.5 victories. He was then rested from operations, but not for long.Following a quick stint on operations with the Kenley Wing in England to gain experience on Spitfires, Caldwell returned to Australia via the Curtis factory in the USA. He was then attached to No. 2 O.T.U. where he flight tested the Australian Boomerang fighter. On 26 November, 1942, Caldwell was assigned to No. 1 Fighter Wing known as the “Churchill Wing” which comprised of 452 of 457 Squadrons RAAF and 54 Squadron RAF. No. 1 Fighter Wing arrived in Darwin on 15 January, 1943 and the unit was equipped with Spitfire Vc (Tropical) code named “Capstan”. The wing performed admirably under Caldwell’s leadership and on 2 March he claimed his first Japanese victories when leading a flight of six Spitfires on patrol. Just beyond landfall he spotted six “Kate” dive-bombers escorted by 12 “Zeros”, preparing to attack allied shipping in the Arafura Sea, north of Darwin.The five Spitfires followed their leader and wreaked so much havoc amongst the enemy that the intruders turned and sped homewards, but not before one “Kate” and one “Zero” fell under Caldwell’s guns. His third tour got underway on 14 April, 1944; Caldwell, now a Group Captain was placed in command of No. 80 Fighter Wing, RAAF. This unit included 79, 452 and 457 Squadrons which were equipped with the Spitfire MkVIII.Caldwell became one of only two Australians to achieve “Ace” status flying from Australia and is portrayed having just destroyed the last of his 28.5 confirmed aerial victories in the evocative painting by Norman Clifford.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Avro 652 Anson C.21 in formation with a DHC-1 Chipmunk and a Percival Provost. RAF Sqdn 61 near RAF Kenley. ca1955

20 notes

·

View notes

Photo

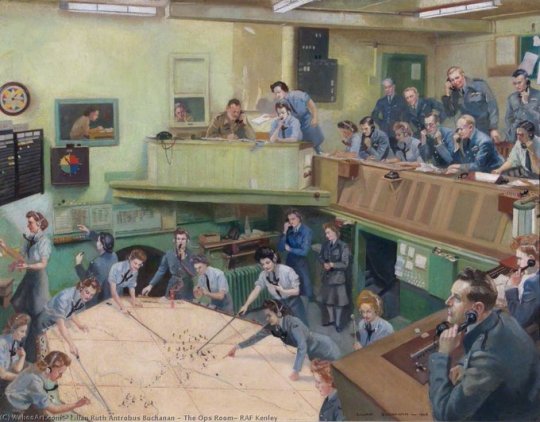

Here's a fantastic oil painting by Lilian Ruth Antrobus Buchanan. "The Ops Room, RAF Kenley"

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Section 5 of the London Loop

The London Outer Orbital Path, or LOOP, almost completely encircles Greater London. Nearly 150 miles are split into 24 mostly flat or gently sloping sections sections between Erith station (1) and Purfleet (24). The Loop combines beautiful open spaces like Hainault Forest Country Park and Bushy Park with historic buildings such as Hall Place and Black Jack's Lock & Mill.

The 10.2km/6.4mile Section 5 is considered one of the most picturesque walks. Notable features you pass through include:

Riddlesdown chalk grassland, ancient woodland and forested paths with the chance to spot wildflowers, birds including nesting skylarks and butterflies (rare chalkhill blue butterfly). The quarry at the foot of Riddledown is approx 200 years old and was working until 1967. The impressive railway viaduct dates from 1884 when the line from East Grinstead to Oxted opened.

Kenley Common came into the City of London's care in 1874. The Royal Flying Corps was based at Kenley Airfield during WW1 and was an RAF base for Spitfires and Hurricanes in WW2.

The stunningly beautiful Happy Valley and Farthing Downs (SSSI) are home to one of Britain's rarest plants - the yellow rattle, so called because when the plant is ready to seed it dries out and rattles. Traces of human occupation dating back to the neolithic periods 12,000 years ago can still be found. Later occupants, Anglo-Saxon communities, used the Downs as a burial ground, creating large burial mounds, known as barrows, for their most important members. From Farthing Downs links to 21st Century London are also visible with views over to the Canary Wharf and the Shard on the horizon.

0 notes

Text

Kenley Scramble: The Definitive History of the RAF Airfield 1917-1940 :: Richard C. Smith

Kenley Scramble: The Definitive History of the RAF Airfield 1917-1940 :: Richard C. Smith

View On WordPress

#24 squadron#615 squadron#978-0-9557-1809-0#aerial actions#aerodrome layouts#aeroplane#air force#aircraft#books by richard c smith#bristol bulldog aircraft#british military history#british war department#fairey battle aircraft#gloster gamecocks#handley page bomber aircraft#hawker hurricanes#hector biplanes#raf kenley#rfc pilots#royal air force history#signed books#world war 2#world war ii#world war two

0 notes

Photo

Pilots of 'B' Flight, No. 32 Squadron, relax on the grass at RAF Hawkinge in front of a Hurricane Mk. I. Left to right: R. F. Smythe, Keith R. Gillman, J. E. Procter, Flight Lieutenant P. M. Brothers, D. H. Grice, P. M. Gardner, and A. F. Eckford (all Pilot Officers except for Brothers). Gillman was posted missing August 25th, 1940, but the rest all survived the war.

A further contingent of NZ airmen are welcomed upon arrival by the High Commissioner for New Zealand. The men are armourers, and wireless operators for ground duties, and have arrived by ship along with members of the Naval Volunteer Reserve.

Two armourers service the machine guns of a Hawker Hurricane Mk. I of No. 85 Squadron, while another unpacks belts of .303 inch ammunition (RAF Debden, July 25th, 1940).

A pilot of No. 64 Squadron RAF runs towards his Supermarine Spitfire Mark 1A as the squadron is scrambled at 10:45 am at Kenley (August 15th, 1940).

WAAF telephone operators in Sector 'G' Operations Room at RAF Duxford, receiving reports of enemy aircraft pilots from Observer Corps posts (September 1940).

A Hurricane pilot discusses his flight with the intelligence officer after returning from aerial combat (October 17th, 1940).

Pilots of No. 310 (Czechoslovak) Squadron RAF and their British flight commanders, grouped in front of a Hawker Hurricane Mk. I at RAF Duxford (September 7th, 1940).

Left to right (standing): Pilot Officer Svatopluk Janouch, Sergeant Josef Vopalecky, Sergeant Raimund Puda, Sergeant Karel Seda, Sergeant Bohumir Furst, and Sergeant Rudolf Zima.

Left to right (sitting): Pilot Officer Vilem Goth, Flight Lieutenant Josef Maly, Flight Lieutenant Gordon L. Sinclair DFC, Flying Officer John E. Boulton, Flight Lieutenant J. Jefferies, Pilot Officer Stanislav Zimprich, Sergeant Jan Kaucky, Flight Lieutenant Frantisek Rypl, Pilot Officer Emil Fechtner, and Pilot Officer Vaclav Bergman.

#history#military history#aviation history#ww2#britain#england#new zealand#czechoslovakia#london#kent#cambridgeshire#folkestone#kenley#duxford#raf hawkinge#raf duxford#raf#waaf#royal observer corps

48 notes

·

View notes

Video

1940 RAF Hawker Hurricane Mk1 V7497 G-HRLI SD-X No 501 Squadron by Chris Murkin Via Flickr: 1940 RAF Hawker Hurricane Mk1 V7497 G-HRLI SD-X No 501 Squadron The aircraft has been painted in the colours SD-X No 501 squadron RAuxAF Based at RAF Kenley UK Photo taken at the Imperial War Museum Duxford Cambridgeshire 14th March 2025 HAA_0721

#Z8#Air#Vintage#History#RAF#Hawker#Hurricane#Mk1#V7497#G-HRLI#41H-136172#War#Museum#Duxford#Cambridgeshire#UK#Nikon#Display#Military#Warbird#WWII#Warbirds#PLANE#Photo#Prop#Fighter#Flying#AIRCRAFT#Aeroplane#Attack

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Group Captain "Johnnie" Johnson, Commanding Officer of the Canadian-manned Kenley Wing in RAF. By VE-Day, his score stood at 34 destroyed, 7 shared destroyed, 3 probables, and 10 damaged. He was the highest scoring Royal Air Force fighter pilot of WW2.

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chris Murkin Following

RAF Hawker Hurricane Mk1 V7497 G-HRLI SD-X P2902 G-ROBT DX-R R4118 G-HUPW UP-W G-HITT P3717 SW-P

1940 RAF Hawker Hurricane Mk1 V7497 G-HRLI SD-X No 501 Squadron

The aircraft has been painted in the colours SD-X No 501 squadron RAuxAF Based at RAF Kenley UK

RAF Hawker Hurricane Mk-1 P2902 G-ROBT DX-R

P2902 was operational with 245 Fighter Squadron based at Drem on the East Coast of Scotland.

RAF Hawker Hurricane Mk-1 R4118 G-HUPW UP-W 605 Squadron

The only Hurricane from the Battle of Britain still airborne today, Mk1 R4118 is widely regarded as the most historic British aircraft to survive in flying condition from the Second World War.

During the Battle of Britain, it flew 49 sorties from Croydon and shot down five enemy aircraft

RAF Hawker Siddeley Hurricane Mk1 G-HITT P3717 SW-P

MkI Hurricane and handed over to the RAF in June 1940 initially flown by Polish Pilot Officer W M C Samolonski with 253 Squadron

Battle Britain Airshow

Photo taken at the Imperial War Museum Duxford Cambridgeshire 18th Sept 2021

BAH_0938

Via Flickr

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

ORIGINAL CHARACTER ROLL-CALL

Meet (some of) my original characters, featured in pieces written—or being written—for the Band of Brothers and Masters of the Air fandoms!

Louise Johnson

Lou was born and raised in the Kent countryside, but moved to London to work as a secretary. When war breaks out, she joins the WAAF, and is later recruited into the Special Operations Executive and dropped into occupied France as a special agent. A Band of Brothers OC, paired with Floyd Talbert, but has also been cloned into the Masters of the Air universe, where she meets a certain Rosie Rosenthal…

Emily Johnson

Emily is Lou’s older sister. She is solemn and shy, a contrast to Lou’s boldness and wicked sense of humour, but when the sisters reconcile they find they share more than they thought.

Ruth Lawrence

During the Battle of Britain, Ruth worked alongside Louise as a WAAF plotter at RAF Kenley, but left the service when she got married. She lives with her husband Tim in London.

Virginia Harris

Vee, as she is known to her friends, is the life and soul of the party. A nursing officer, she works in a RAF hospital in Scotland, alongside her close friend and fellow nurse Ada Monroe.

John Ferraby

Half-French, half-English, John is a lieutenant in the Royal Signals and an SOE wireless operator. He is teamed up with Louise prior to D-Day.

Eve Dalton

Eve is a farmer’s daughter, born and bred in Aldbourne. She works as a nurse at the prestigious St Thomas’ Hospital in London, but returns to her home village for a few months in the summer of 1944.

Rosie Clifton

The Honourable Rosalie Clifton, to give her full title, is the only daughter in a wealthy English family. Her father and brothers love parties, fast cars, and drinking; Rosie does not. But she does share their love of aircraft and flying. During the war Rosie joins the Air Transport Auxiliary.

Nina Bowen

Originally from a village in Shropshire, where her father owns a garage and her mother runs the adjoining tearoom, Nina is a driver in the WAAF. In the autumn of 1943, she is shuttling workers to and from RAF Ludham.

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

F/O Bob Middlemiss and F/O George 'Buzz' Beurling DSO, DFC, DFM and Bar, RCAF 403 Squadron, RAF Kenley in Surrey, late 1943.

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

• Douglas Bader (English RAF Ace)

Group Captain Sir Douglas Robert Steuart Bader, CBE, DSO & Bar, DFC & Bar was a Royal Air Force flying ace during the Second World War. He was credited with 22 aerial victories.

Bader was born on February 21st 1910 in St John's Wood, London, the second son of Frederick Roberts Bader, a civil engineer, and his wife Jessie Scott MacKenzie. His first two years were spent with McCann relatives in the Isle of Man while his father, accompanied by Bader's mother and older brother Frederick, returned to his work in India after the birth of his son. At the age of two, Bader joined his parents in India for a year. When his father resigned from his job in 1913 the family moved back to London. Bader's father saw action in the First World War in the Royal Engineers, and was wounded in action in 1917. He remained in France after the war, where, having attained the rank of major, he died in 1922 of complications from those wounds in a hospital in Saint-Omer. Bader's mother was remarried shortly thereafter to the Reverend Ernest William Hobbs. Bader was subsequently brought up in the rectory of the village of Sprotbrough, near Doncaster, West Riding of Yorkshire. His mother showed little interest in Bader and sent him to his grandparents on occasion. Without guidance, Bader became unruly. Bader was then sent as a boarder to Temple Grove School, one of the "Famous Five" of English prep schools, however one which gave its boys a Spartan upbringing.

Bader's aggressive energy found a new lease of life at St Edward's School, where he received his secondary education. During his time there, he thrived at sports. Bader played rugby and often enjoyed physical battles with bigger and older opponents. In mid-1923, Bader, at the age of 13, was introduced to an Avro 504 during a school holiday trip to visit his aunt, Hazel, who was marrying RAF Flight Lieutenant Cyril Burge, adjutant at RAF Cranwell. Although he enjoyed the visit and took an interest in aviation, he showed no signs of becoming a keen pilot. Bader's formative years, he took less of an interest in his studies. However, Bader received guidance from his school's headmaster Warden Henry E. Kendall and, with Kendall's encouragement, he excelled at his studies and was later accepted as a cadet at RAF Cranwell. In 1928, Bader joined the RAF as an officer cadet at the Royal Air Force College Cranwell in rural Lincolnshire. On 13 September 1928, Bader took his first flight with his instructor Flying Officer W. J. "Pissy" Pearson in an Avro 504. After just 11 hours and 15 minutes of flight time, he flew his first solo, on February 19th, 1929. Bader competed for the "Sword of Honour" award at the end of his two-year course, but lost to Patrick Coote, his nearest rival.

On July 26th, 1930, Bader was commissioned as a pilot officer into No. 23 Squadron RAF based at Kenley, Surrey. Flying Gloster Gamecocks and soon after Bristol Bulldogs, Bader became a daredevil while training there, often flying illegal and dangerous stunts. While very fast for its time, the Bulldog had directional stability problems at low speeds, which made such stunts exceptionally dangerous. After one training flight at the gunnery range, Bader achieved only a 38 percent hit rate on a target. Receiving jibes from a rival squadron (No. 25 Squadron RAF), Bader took off to perform aerobatics and show off his skill. It was against regulations, and seven out of 23 accidents caused by ignoring regulations had proven fatal. Nevertheless, on December 14th, 1931, while visiting Reading Aero Club, Bader attempted some low-flying aerobatics at Woodley Airfield in a Bulldog Mk. IIA, K1676, apparently on a dare. His aircraft crashed when the tip of the left wing touched the ground. Bader was rushed to the Royal Berkshire Hospital. Both his legs were amputated one above and one below the knee. Bader made the following laconic entry in his logbook after the crash, "Crashed slow-rolling near ground. Bad show." In 1932, after a long convalescence, throughout which he needed morphine for pain relief, Bader was transferred to the hospital at RAF Uxbridge and fought hard to regain his former abilities after he was given a new pair of artificial legs. In time, his agonising and determined efforts paid off, and he was able to drive a specially modified car, play golf, and even dance. Bader got his chance to prove that he could still fly when, in June 1932, Air Under-Secretary Philip Sassoon arranged for him to take up an Avro 504, which he piloted competently. A subsequent medical examination proved him fit for active service, but in April 1933 he was notified that the RAF had decided to reverse the decision on the grounds that this situation was not covered by King's Regulations. In May, Bader was invalided out of the RAF, took an office job with the Asiatic Petroleum Company (now Shell) and, in October 1933, married Thelma Edwards, a waitress he meet during his convalescence.

Against a background of increasing tensions in Europe in 1937–39, Bader repeatedly requested that the Air Ministry accept him back into the RAF and he was finally invited to a selection board meeting at Adastral House in London's Kingsway. Bader was disappointed, it appeared that he would be refused a flying position but Air Vice-Marshal Halahan, commandant of RAF Cranwell in Bader's days there, personally endorsed him and asked the Central Flying School, Upavon, to assess his capabilities. On October 14th, 1939, the Central Flying School requested Bader report for flight tests on the 18th. He did not wait; driving down the next morning, Bader undertook refresher courses. Despite reluctance on the part of the establishment to allow him to apply for an A.1.B. (full flying category status), his persistent efforts paid off. Bader regained a medical categorisation for operational flying at the end of November 1939 and was posted to the Central Flying School for a refresher course on modern types of aircraft. In November, eight years after his accident, Bader flew solo again in an Avro Tutor; once airborne, he could not resist the temptation to turn the biplane upside down at 600 feet (180 m) inside the circuit area. Bader subsequently progressed through the Fairey Battle and Miles Master (the last training stage before flying Spitfires and Hurricanes). In January 1940, Bader was posted to No. 19 Squadron based at RAF Duxford near Cambridge, where, at 29, he was older than most of his fellow pilots. Geoffrey Stephenson, a close friend from his Cranwell days, was the commanding officer, and it was here that Bader got his first glimpse of a Spitfire. It was thought that Bader's success as a fighter pilot was partly because of his having no legs; pilots pulling high g-forces in combat turns often blacked out as the flow of blood from the brain drained to other parts of the body, usually the legs. As Bader had no legs he could remain conscious longer, and thus had an advantage over more able-bodied opponents.

Between February and May 1940 Bader practised formation flying and air tactics, as well as undertaking patrols over convoys out at sea. Bader found opposition to his ideas about aerial combat. He favoured using the sun and altitude to ambush the enemy, but the RAF did not share his opinions. Official orders/doctrine dictated that pilots should fly line-astern and attack singly. Despite this being at odds with his preferred tactics, Bader obeyed orders, and his skill saw him rapidly promoted to section leader. Bader was subsequently promoted from flying officer to flight lieutenant, and appointed as a flight commander of No. 222 Squadron RAF. Bader had his first taste of combat with No. 222 Squadron RAF, which was based at RAF Duxford and commanded by another old friend of his, Squadron Leader "Tubby" Mermagen. In May, 1940 Germany invaded France as well as it's neighboring countries. RAF squadrons were ordered to provide air supremacy for the Royal Navy during Operation Dynamo. While patrolling the coast near Dunkirk on June 1st, 1940 at around 3,000 ft (910 m), Bader happened upon a Messerschmitt Bf 109 in front of him, flying in the same direction and at approximately the same speed. Believing the pilot must have been a novice, taking no evasive action even though it took more than one burst of gunfire to shoot him down. In the next patrol Bader was credited with a Heinkel He 111 damaged. On June 4th, 1940, his encounter with a Dornier Do 17, which was attacking Allied shipping, involved a near collision while he was firing at the aircraft's rear gunner during a high-speed pass. Shortly after Bader joined 222 Squadron, it moved to RAF Kirton in Lindsey, just south of the Humber. After flying operations over Dunkirk, on June 28th, 1940 Bader was posted to command No. 242 Squadron RAF as acting squadron leader.

No. 242 Squadron was mainly made up of Canadians who had suffered high losses in the Battle of France and when Bader arrived were suffering from low morale. Despite initial resistance to their new commanding officer, the pilots were soon won over by Bader's strong personality and perseverance, especially in cutting through red tape to make the squadron operational again. Bader transformed No. 242 Squadron back into an effective fighting unit. Upon the formation of No. 12 Group RAF, 242 Squadron was assigned to the Group while based at RAF Duxford. After the French campaign, the RAF prepared for the coming Battle of Britain in which the Luftwaffe intended to achieve air supremacy. Once attained, the Germans would attempt to launch Operation Sea Lion, the codename for an invasion of Britain. The battle officially began on July 10th, 1940. On the 11th, Bader scored his first victory with his new squadron. The cloud base was down to just 600 ft, and forward visibility was down to just 2,000 yards. Bader was alone on patrol, and was soon directed toward an enemy aircraft flying north up the Norfolk coast. Spotting the aircraft at 600 yards, Bader recognised it as a Dornier Do 17, and after he closed to 250 yards its rear gunner opened fire. Bader continued his attack and fired two bursts into the bomber before it vanished into cloud. The Dornier, which crashed into the sea off Cromer, was later confirmed by a member of the Royal Observer Corps. Later in the month, Bader scored a further two victories over Messerschmitt Bf 110s. On August 30th, 1940, No. 242 Squadron was moved to Duxford again and found itself in the thick of the fighting. On this date, the squadron claimed 10 enemy aircraft, Bader scoring two victories against Bf 110s. On September 7th, two more Bf 110s were shot down, but in the same engagement Bader was badly hit by a Messerschmitt Bf 109. Bader almost baled out, but recovered the Hurricane. Bader claimed two Bf 109s shot down, followed by a Junkers Ju 88. Two days later, Bader claimed another Dornier. On September 14th, Bader was awarded the Distinguished Service Order (DSO) for his combat leadership. On September 24th, he had been promoted to the war substantive rank of flight lieutenant. During the Battle of Britain, Bader used three Hawker Hurricanes. The first, in which he scored six air victories. The second aircraft, Bader did score one victory and two damaged in it on September 9th. The third, in which he destroyed four more and added one probable and two damaged by the end of September. On December 12th 1940, Bader was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross (DFC) for his services during the Battle of Britain. His unit, No. 242 Squadron, had claimed 62 aerial victories.

On March 18th, 1941, Bader was promoted to acting wing commander and became one of the first "wing leaders". Stationed at Tangmere with 145, 610 and 616 Squadrons under his command, Bader led his wing of Spitfires on sweeps and "Circus" operations over north-western Europe throughout the summer campaign. During 1941 his wing was re-equipped with Spitfire VBs, which had two Hispano 20 mm cannon and four .303 machine guns. Bader flew a Mk VA equipped with eight .303 machine guns. Bader's combat missions were mainly fought against Bf 109s over France and the Channel. On May 7th, 1941 he shot down one Bf 109 and claimed another as a probable victory. The following month was more successful for Bader. On July 2nd, 1941 he was awarded the bar to his DSO. On the 12th, Bader found further success, shooting down one Bf 109 and damaging three others between Bethune and St Omer. Bader had been pushing for more sorties to fly in late 1941 but his Wing was tired. He was intent on adding to his score, which, according to the CO of No. 616 Squadron RAF Billy Burton, brought the other pilots and mood in his wing to a near-mutinous state. Bader's immediate superior of OC No. 11 Group, Fighter Command, relented and allowed Bader to continue frequent missions over France even though his score numbered 20 victories. Between March and August 1941, Bader flew 62 fighter sweeps over France.

On August 9th, 1941, Bader flying a Spitfire Mk VA without his wingman on an offensive patrol over the French coast, looking for Messerschmitt Bf 109s. Just after Bader's section of four aircraft crossed the coast, 12 Bf 109s were spotted flying in formation approximately 2,000 feet (600 metres) below them and travelling in the same direction. Bader dived on them too fast and too steeply to be able to aim and fire his guns, and barely avoided colliding with one of them. He levelled out at 24,000 feet (7,300 metres) to find that he was now alone, separated from his section, and was considering whether to return home when he spotted three pairs of Bf 109s a couple of miles in front of him. He dropped down below them and closed up before destroying one of them with a short burst of fire from close range. Bader was just opening fire on a second Bf 109, which trailed white smoke and dropped down, when he noticed the two on his left turning towards him. At this point he decided it would be better to return home; however, making the mistake of banking away from them, Bader believed he had a mid-air collision with the second of the two Bf 109s. Bader's fuselage, tail and fin were gone from behind him, and he lost height rapidly at what he estimated to be 400 mph (640 km/hr) in a slow spin. He jettisoned the cockpit canopy, released his harness pin, and the air rushing past the open cockpit started to suck him out, but his prosthetic leg was trapped. Part way out of the cockpit and still attached to his aircraft, Bader fell for some time before he released his parachute, at which point the leg's retaining strap snapped under the strain and he was pulled free. Bader's aircraft was not found. It is likely that it came down at Mont Dupil Farm near the French village of Blaringhem, possibly near Desprez sawmill. A French witness, Jacques Taffin, saw the Spitfire disintegrating as it came down. He thought it had been hit by anti-aircraft fire, but none was active in the area. There were also no Spitfire remains in the area. The lack of any remains was not surprising, owing to the Spitfire breaking up on its descent. After crashing Bader was soon taken prisoner by the Germans. The Germans treated Bader with great respect. When Bader was taken prisoner, he was sent to a hospital near Saint-Omer, near the place where his father's grave is located. On leaving the hospital, Colonel Adolf Galland and his pilots invited him on to their airfield and they received him as a friend. Bader was cordially invited to sit in the cockpit of Galland's personal Me109. Bader asked Galland if it was possible to test the 109 by "a flight around the airfield". Galland refused him with laughter!

Bader had lost a prosthetic leg when escaping his disabled aircraft. When he had baled out, Bader's right prosthetic leg became trapped in the aircraft, and he escaped only when the leg's retaining straps snapped after he pulled the ripcord on his parachute. General Adolf Galland notified the British of his damaged leg and offered them safe passage to drop off a replacement. Hermann Göring himself gave the green light for the operation. The British responded on August 19th, 1941 with the "Leg Operation" an RAF bomber was allowed to drop a new prosthetic leg by parachute to St Omer, a Luftwaffe base in occupied France. Galland stated in an interview that the aircraft dropped the leg after bombing Galland's airfield. Galland did not meet Bader again until mid-1945, when he arrived at RAF Tangmere as a prisoner of war. Bader escaped from the hospital where he was recovering by tying together sheets. Initially the "rope" did not reach the ground; with the help of another patient, he slid the sheet from under the comatose New Zealand pilot, Bill Russell of No. 485 Squadron, who had had his arm amputated the day before. Russell's bed was then moved to the window to act as an anchor. The plan worked initially. Bader completed the long walk to the safe house despite wearing a British uniform. Unfortunately for him, the plan was betrayed by a woman at the hospital. He hid in the garden when a German staff car arrived outside a house, but was found later. Over the next few years, Bader made himself a thorn in the side of the Germans. He often practised what the RAF personnel called "goon-baiting". He considered it his duty to cause as much trouble to the enemy as possible, much of which included escape attempts. He made so many escape attempts that the Germans threatened to take away his legs. In August 1942, Bader escaped with Johnny Palmer and three others from the camp at Stalag Luft III B in Sagan. Unluckily, a Luftwaffe officer of JG 26 was in the area. Keen to meet the Tangmere wing leader, he dropped by to see Bader, but when he knocked on his door, there was no answer. Soon the alarm was raised, and a few days later, Bader was recaptured. He was finally dispatched to the "escape-proof" Colditz Castle Oflag IV-C on August 18th, 1942, where he remained until April 15th, 1945 when it was liberated by the First United States Army.

After his return to Britain, Bader was given the honour of leading a victory flypast of 300 aircraft over London in June 1945. On July 1st, he was promoted to temporary wing commander. Bader was given the post of the Fighter Leader's School commanding officer. He received a promotion to war substantive wing commander on December 1st, and soon after was promoted to temporary group captain. Unfortunately for Bader, the fighter aircraft's roles had now expanded significantly and he spent most of his time instructing on ground attack and co-operation with ground forces. Also, Bader did not get on with the newer generation of squadron leaders who considered him to be "out of date". It is likely Bader would have stayed in the RAF for some time had his mentor Leigh-Mallory not been killed in an air crash in November 1944, such was the respect and influence he held over Bader, but Bader's enthusiasm for continued service in the RAF waned. In July 1946, Bader retired from the RAF with the rank of group captain to take a job at Royal Dutch Shell. Bader considered politics, and standing as a Member of Parliament for his home constituency in the House of Commons. He despised how the three main political parties used war veterans for their own political ends. Instead, he resolved to join Shell. He spent most of his time abroad flying around in a company-owned Percival Proctor and later a Miles Gemini. In September 1946, Bader was sent on a public relations mission for Shell around Europe and North Africa with United States Army Air Forces (USAAF) Lieutenant General James Doolittle, Doolittle having left active duty in January 1946. Bader's first wife, Thelma, developed throat cancer in 1967. Aware that her survival was unlikely, the two spent as much time with each other as possible. After a long battle, she died on January 24th, 1971, aged 64. Bader married Joan Murray on January 3rd, 1973. They spent the remainder of their lives in the village of Marlston, Berkshire. Bader campaigned vigorously for people with disabilities and set an example of how to overcome a disability. In June 1976, Bader was knighted for his services to disabled people. Bader died of a heart attack on September 5th, 1982 at the age of 72 in Chiswick, London. Afterwards On the 60th anniversary of Bader's last combat sortie, his widow Joan unveiled a statue at Goodwood, formerly RAF Westhampnett, the aerodrome from which he took off. The Douglas Bader Foundation was formed in honour of Bader in 1982 by family and friends many also former RAF pilots who had flown with Bader during the Second World War. One of Bader's artificial legs is kept by the RAF Museum at their warehouse in Stafford, and is not on public display.

#second world war#world war 2#world war ii#british history#royal air force#aviation#air force history#aircraft#biography

114 notes

·

View notes