#Perkins brailler

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

@estsolcity ( for valeria )

Technology had come along way, but it seemed the humble, hefty Brailler was slowly fighting against progress. And against staying in working order. With a grunt, he drops the far too heavy machinery on the table. "Old Perkins' kicked the bucket. Again. Is it too much to ask for you to just... invent a new one?"

#valeria#valeria: perkins#( braillers haven't changed in YEARS and im fascinated by them#go ham if valeria wants to have made a new version or they can chat or w/e ! we can assume some connection or#assume he thinks he's talking to someone else )

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

How Blind People Write Braille (Part 1)

Tommy Edison, who's been blind since birth, shows us his vintage Perkins Brailler that he's used to write Braille since childhood.

#blindness#blind#brailler#accessibility#vintage#perkins#writing#technology#vintage tech#retro tech#retro

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Okay so the standard qwerty keyboard has 26 letter keys plus all the punctuation marks, number and function keys. That's over 60 keys and some have several functions so you occasionally need to press several keys per symbol but mostly it's one key per letter. According to Google, the average typing speed is 40 wpm and nearly double that number for professional typists. Stenotype keyboards have only 22 keys and experienced people can type 300 wpm with it. A Perkins Brailler has only six keys which means one to six simultaneous strokes to represent all letters/numbers. I couldn't find any information on typing speed. A telegraph machine only needs one key but up to five consecutive strokes per letter/number. Google mentions speeds of 20 wpm but I'm sure you could go faster if it's used as typing input and not read by a human.

Somewhere in the middle exist a keyboard layout that can minimise key numbers, maximise typing speed and is also easy to use.

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

‘We’d be stuck’: alarm as UK’s last braille typewriter repairer ponders retirement

Alan Thorpe is Britain’s last certified fixer of the Perkins brailler, a machine vital for teaching blind children to read and write

Article by Matthew Weaver

0 notes

Text

Braille Development: A Journey of Innovation and Accessibility

Braille, a tactile writing system used by blind and visually impaired individuals, has a rich history of development that spans nearly two centuries. The evolution of Braille has been marked by ingenuity, perseverance, and a relentless pursuit of accessibility. This article delves into the development of Braille, highlighting its origins, advancements, and impact on the blind community.

Origins of Braille

The story of Braille begins with Louis Braille, a Frenchman born in 1809 who lost his sight due to a childhood accident. In 1824, at the age of 15, Louis Braille invented the system that bears his name. He was inspired by a military code called "night writing," devised by Charles Barbier, which allowed soldiers to communicate silently and without light. While Barbier's system was innovative, it was cumbersome and difficult to use for everyday reading and writing.

Louis Braille simplified and refined Barbier’s concept, creating a system based on cells of six raised dots arranged in a 3x2 grid. Each combination of dots represented different letters, numbers, and punctuation marks. This innovation provided a simple, efficient, and versatile means for blind individuals to read and write through touch.

Early Adoption and Resistance

Despite its effectiveness, the Braille system faced significant resistance in its early years. Many educators and institutions for the blind were reluctant to adopt it, preferring to rely on embossed text systems that were less efficient and harder to learn. However, the persistence of Louis Braille and his advocates eventually paid off. By the mid-19th century, the Braille system began to gain acceptance, starting with the Royal Institute for Blind Youth in Paris.

Global Expansion

As the benefits of Braille became more widely recognized, the system spread beyond France. By the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Braille had been adapted to multiple languages, each with its own unique code to accommodate different alphabets and linguistic needs. This adaptability was a key factor in Braille’s global expansion.

Technological Advancements

The 20th century brought significant technological advancements that further developed Braille. The invention of the Perkins Brailler, a typewriter-like device for Braille writing, revolutionized how Braille was produced and used. This durable, easy-to-use machine allowed for faster and more efficient Braille writing, making it more accessible for students and professionals alike.

In recent decades, digital technology has brought even more advancements to Braille. Refreshable Braille displays, which use electronic pins to form Braille characters, allow users to read digital text in real-time. These devices can be connected to computers, tablets, and smartphones, providing blind individuals with unprecedented access to digital information.

Braille Literacy and Education

The development of Braille has had a profound impact on education for blind and visually impaired individuals. Braille literacy is crucial for academic success and overall independence. Various organizations, including the American Foundation for the Blind (AFB), have been instrumental in promoting Braille literacy through educational programs, resources, and advocacy.

Challenges and Future Directions

Despite its many benefits, Braille usage has declined in recent years due to various factors, including the rise of audio books and screen reader technology. However, Braille remains an essential tool for many blind individuals, particularly for reading complex materials such as mathematics and science texts.

Efforts are ongoing to integrate Braille with modern technology further. Innovations such as Braille e-readers and portable Braille notetakers are making Braille more versatile and accessible. Moreover, advocacy for Braille literacy continues to be a priority, ensuring that future generations of blind individuals can benefit from this invaluable system.

Conclusion

The development of Braille is a testament to human ingenuity and the drive for accessibility and independence. From its origins in the mind of a young French boy to its global adoption and technological advancements, Braille has profoundly impacted the lives of countless individuals. As we look to the future, continued innovation and advocacy will ensure that Braille remains a vital tool for literacy and empowerment in the blind community.

For more information on Braille development and resources, visit the Braille.NL for the Blind.

1 note

·

View note

Text

DYMO have a label maker that does braille. Can't remember what it costs but it does it letter by letter, kinda embossing through pressure. It takes forever but it's cheaper than the electric ones or a Perkins brailler by like a bunch. I don't use mine often anymore but it is handy in a pinch!

I've got a great idea for my next video, I just need to figure out how to label floppy disks in Braille and I'm set

76 notes

·

View notes

Text

Braille system

Braille is a tactile writing system used by the blind and the visually impaired. It is traditionally written with embossed paper. Braille-users can read computer screens and other electronic supports thanks to refreshable braille displays. They can write braille with the original slate and stylus or type it on a braille writer, such as a portable braille note-taker, or on a computer that prints with a braille embosser. Braille is named after its creator, Frenchman Louis Braille, who went blind following a childhood accident. In 1824, at the age of 15, Braille developed his code for the French alphabet as an improvement on night writing. He published his system, which subsequently included musical notation, in 1829.[2] The second revision, published in 1837, was the first digital (binary) form of writing.

Braille characters are small rectangular blocks called cells that contain tiny palpable bumps called raised dots. The number and arrangement of these dots distinguish one character from another. Since the various braille alphabets originated as transcription codes of printed writing systems, the mappings (sets of character designations) vary from language to language. Furthermore, in English Braille there are three levels of encoding: Grade 1, a letter-by-letter transcription used for basic literacy; Grade 2, an addition of abbreviations and contractions; and Grade 3, various non-standardized personal shorthands. Braille cells are not the only thing to appear in embossed text. There may be embossed illustrations and graphs, with the lines either solid or made of series of dots, arrows, bullets that are larger than braille dots, etc. In the face of screen-reader software, braille usage has declined. However, braille education remains important for developing reading skills among blind and visually impaired children, and braille literacy correlates with higher employment rates.

Braille was based on a tactile military code called night writing, developed by Charles Barbier in response to Napoleon's demand for a means for soldiers to communicate silently at night and without light. In Barbier's system, sets of 12 embossed dots encoded 36 different sounds. It proved to be too difficult for soldiers to recognize by touch, and was rejected by the military. In 1821 Barbier visited the Royal Institute for the Blind in Paris, where he met Louis Braille. Braille identified two major defects of the code: first, by representing only sounds, the code was unable to render the orthography of the words; second, the human finger could not encompass the whole 12-dot symbol without moving, and so could not move rapidly from one symbol to another. Braille's solution was to use 6-dot cells and to assign a specific pattern to each letter of the alphabet.[3] At first, braille was a one-to-one transliteration of French orthography, but soon various abbreviations, contractions, and even logograms were developed, creating a system much more like shorthand.[4] The expanded English system, called Grade-2 Braille, was complete by 1905. For the blind today, braille is an independent writing system rather than a code of printed orthography.[5]

Derivation

Braille is derived from the Latin alphabet, albeit indirectly. In Braille's original system, the dot patterns were assigned to letters according to their position within the alphabetic order of the French alphabet, with accented letters and w sorted at the end.[6]The first ten letters of the alphabet, a–j, use the upper four dot positions: ⠁⠃⠉⠙⠑⠋⠛⠓⠊⠚ (black dots in the table below). These stand for the ten digits 1–9 and 0 in a system parallel to Hebrew gematria and Greek isopsephy. (Though the dots are assigned in no obvious order, the cells with the fewest dots are assigned to the first three letters (and lowest digits), abc = 123 (⠁⠃⠉), and to the three vowels in this part of the alphabet, aei (⠁⠑⠊), whereas the even digits, 4, 6, 8, 0 (⠙⠋⠓⠚), are corners / right angles.)The next ten letters, k–t, are identical to a–j, respectively, apart from the addition of a dot at position 3 (red dots in the table): ⠅⠇⠍⠝⠕⠏⠟⠗⠎⠞:

Unicode rendering table

The Unicode standard encodes 8-dot braille glyphs according to their binary appearance, rather than following their assigned numeric order. Unicode defines the character block "Braille Patterns" in the hex code-point range of 2800 to 28FF. Dot 1 corresponds to the least significant bit of the low byte of the Unicode scalar value, and dot 8 to the high bit of that byte. Most braille embossers and refreshable braille displays do not support Unicode, using instead 6-dot braille ASCII. Because of this, they are unable to display this article. Some embossers have proprietary control codes for 8-dot braille or for full graphics mode, where dots may be placed anywhere on the page without leaving any space between braille cells, so that continuous lines can be drawn in diagrams, but these are rarely used and are not standard.

Page dimensions

Most braille embossers support between 34 and 37 cells per line, and between 25 and 28 lines per page. A manually operated Perkins braille typewriter supports a maximum of 42 cells per line (its margins are adjustable), and typical paper allows 25 lines per page. A large interlining Stainsby has 36 cells per line and 18 lines per page. An A4-sized Marburg braille frame, which allows interpoint braille (dots on both sides of the page, offset so they do not interfere with each other) has 30 cells per line and 27 lines per page.

Literacy

A sighted child who is reading at a basic level should be able to understand common words and answer simple questions about the information presented.[9] The child should also have enough fluency to get through the material in a timely manner. Over the course of a child's education, these foundations are built upon in order to teach higher levels of math, science, and comprehension skills.[9] Children who are blind not only have the educational disadvantage of not being able to see, but they also miss out on the very fundamental parts of early and advanced education if not provided with the necessary tools.

U.S. braille literacy statistics

In 1960, 50% of legally blind, school-age children were able to read braille in the U.S.[10][11] According to the 2011 Annual Report from the American Printing House for the Blind, there are approximately 58,939 legally blind children in the U.S aged 0–21. Of these, about 9% prefer braille as their primary reading medium; 27% are visual readers, 8% are auditory readers, 21% are pre-readers, and 34% are non-readers.[12]There are numerous causes for the decline in braille usage, including school budget constraints, technology advancement, and different philosophical views over how blind children should be educated.[13]

A key turning point for braille literacy was the passage of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, an act of Congress that moved thousands of children from specialized schools for the blind into mainstream public schools.[11] Because only a small percentage of public schools could afford to train and hire braille-qualified teachers, braille literacy has declined since the law took effect.[clarification needed][11] Braille literacy rates have improved slightly since the bill was passed,[clarification needed] in part because of pressure from consumers and advocacy groups that has led 27 states to pass legislation mandating that children who are legally blind be given the opportunity to learn braille.[13]

In 1998–99, there were approximately 55,200 legally blind children in the United States, but only 5,500 of them used braille as their primary reading medium.[14][15] Early Braille education is crucial to literacy for a visually impaired child. A study conducted in the state of Washington found that people who learned braille at an early age did just as well, if not better, than their sighted peers in several areas, including vocabulary and comprehension. In the preliminary adult study, while evaluating the correlation between adult literacy skills and employment, it was found that 44% of the participants who had learned to read in braille were unemployed, compared to the 77% unemployment rate of those who had learned to read using print.[16] Currently, among the estimated 85,000 blind adults in the United States, 90% of those who are braille-literate are employed. Among adults who do not know braille, only 33% are employed.[11] Statistically, history has proven that braille reading proficiency provides an essential skill set that allows visually impaired children not only to compete with their sighted peers in a school environment, but also later in life as they enter the workforce.[13]

United Kingdom

Though braille is thought to be the main way blind people read and write, in Britain (for example) out of the reported 2 million visually impaired population, it is estimated that only around 15–20 thousand people use braille.[17] Younger people are turning to electronic text on computers with screen reader software instead, a more portable communication method that they can also use with their friends. A debate has started on how to make braille more attractive and for more teachers to be available to teach it.

#Refreshable braille display#Perkins Brailler#Napoleon#Louis Braille#Latin alphabet#French alphabet#Charles Barbier#Braille

0 notes

Text

The Unbecoming of Elias Bouchard (M, ao3)

After about 1,000,000 years (10 months), my Michael/OGElias fic is finished! Hooray! Enormous shoutout to @blindbeta for doing a sensitivity read (and more, tbh) for me! Check it out here

Excerpt (from Chapter 4):

Some days it was like this:

“You’re too old to sit like that now, surely.” Michael commented, dropping two tote bags of groceries on the kitchen island and shaking off his coat.

Elias grinned where he was sat at the dining room table, chair turned the wrong way ‘round, chin resting on the chair back. “Counterculture ‘til I die, baby.”

Michael laughed and leaned over Elias where he was now frowning at his Perkins Brailler, trying to remember what his teacher had said about telling the difference between “i” and “e”.

“And how goes the memoir?” Michael teased. Really, tell the man you feel like Hemingway on the machine one time…

“It will be earth-shattering, so long as I can learn to spell my name right. Check for me?”

And Michael did, and then started chopping vegetables for their dinner and Elias turned on the record player and went back to clacking away with his tongue between his lips in concentration. The quiet between them was comfortable as a warm quilt, patchworked with the worn scraps of who they were before, and when Michael walked by Elias to go to the pantry, he trailed a hand over his shoulder and Elias leaned into it, easy as anything.

Elias dug his socked toes into the carpet and inhaled the smell of onion and garlic sauteing in a pan and the soft sound of Michael singing to himself and it was perfect.

Then, other days were like this:

The sounds of Michael pacing his bedroom, rambling to himself, his manic bursts of laughter. Elias knew better than to go in and try to talk to him—these dark moods were just another part of their life now. Sometimes Michael was still his ray of sunshine, bright and eager to please and then a switch would flip and his laugh would turn mocking, or he would have a short burst of meanness, like a raincloud passing by, there and then gone. It was a small price to pay to get Michael back, to be allowed to keep him. But that didn’t make it any easier.

There was a crash that suggested broken glass and Elias huffed out a sigh and flipped to his other side, resisting the childish urge to stuff a pillow over his head. Michael—the old Michael—would have been much better at this than Elias was, if their positions were reversed. Michael had been much better; how many times had he held and soothed away Elias’s frantic energy?

It’s just. They weren’t—well, Elias wasn’t sure what they were and weren’t, exactly. They certainly weren’t in a relationship, at least not the kind they had been in when they were in their 20s. Elias would say “roommates,” if the thought wasn’t so depressing he wanted to fling himself off the roof, but, honestly, that wasn’t quite right either.

It felt like living with a total stranger, in many ways, except the total stranger knew a handful of the most important things about you and also you were still, inconveniently, in love with him. Also he was a little bit of a monster.

An enormous thud let Elias know that Michael had flipped over the guest bed again. He should really get up and go to him.

Instead, he groped around the bedside table for his earplugs. For all his growth, he was still a coward.

[don't worry, this has a happy ending :))]

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

Writing A Blind/Visually Impaired Character: Canes, Guide Dogs, O&M

Wow, back in June I decided to take a few months break from blogging to recharge and focus on my mental health. About a month ago I began writing this specific post, slowly and in stages because of how demanding, detailed, and long it is.

I’m not sure when I planned to come back. I have about 200 posts with tags and image description in my drafts folder, waiting to be queued, but I wanted to finish this guide before I fully came back.

Come back with a bang, right?

But this blog, and specifically, my Writing a Blind or Visually Impaired Character guide, has gotten so much traffic and support that I felt incredibly motivated to come back now.

So I finished the guide, and now here it is. It’s been a year+ in the making. Since the very beginning of this writing advice series about writing blind characters, I’ve promised to write a guide specifically about canes, guide dogs, O&M, and other accessibility measures the blind community relies on.

In fact, if you look at my master post for this guide (now pinned at the first post on my blog) you’ll find that it was reserved as Part Four, even as other guides and additions were added over the last year.

In this post I’ll be explaining

What Orientation and Mobility (O&M) is

How one learns O&M

About canes, from different types of canes and their parts, as well as how to use a cane.

I will be explaining the sensory experiences of using a cane and how to describe it in narrative.

I will include small mannerisms long-time cane uses might develop.

At the very end will be a section on guide dogs, but this will be limited to research because I have no personal experience with guide dogs, being a cane user.

Disclaimer: I am an actual visually impaired person who has been using a cane for nearly three years and has been experiencing vision loss symptoms for a few years longer than that. This guide is based on both my experiences and my research. My experiences are not universal however because every blind person has a unique experience with their blindness

What Is Orientation & Mobility

Orientation and Mobility (O&M) is the specific skill of understanding and navigating the world safely and confidently with vision loss.

I’m going to quote Vision Aware’s specific definition [link]

"Orientation" refers to the ability to know where you are and where you want to go, whether you're moving from one room to another or walking downtown for a shopping trip.

"Mobility" refers to the ability to move safely, efficiently, and effectively from one place to another, such as being able to walk without tripping or falling on steps or elevation changes, crossing streets, and using public transportation

O&M can involve :

-learning how to use a cane, as well as what cane works best for you

-safely navigating obstacles with your cane, including stairs, ramps, elevators, uneven or curved sidewalks, through crowds, around furniture

-learning safe strategies for crossing the street

-planning routes to new or recurring locations

-using technology enroute, including GPS and apps like Uber and Lyft

-safely accessing public transportation

-how to ask for help when needed

-working with human sighted guides

A Note on the Blind Community and Their Relationship with Canes

The Perkins School for the Blind estimates that only 2-8% of the blind community rely on canes for navigation. The rest rely on remaining vision, guide dogs, and sighted guides. Only about 2% of the blind community relies on guide dogs however, and to get a guide dog in the first place, a person must go through O&M classes and use a cane for six months before they can sign up for a guide dog.

What this means is that 90% of the blind community don’t use a cane.

I didn’t know this fact until I begun research for this guide, and that number astounds me.

Truth be told, while I have navigated my life without a cane before, I can’t imagine going back to the way it was before I got it. Even if I only need my cane some of the time, I can’t bear to not use it in the situations I need it. Having a cane made my life a lot easier, a lot safer.

I don’t know what to attribute this number to.

I might attribute it to the concepts of invisible vs. visible disability, internalized ableism, or the feeling of ‘not being blind enough’ for a cane, as well as accessibility to the blind community and knowledge, and access to buying a cane in the first place. I could write a thing about it, but if I try it’s gonna be its own post.

Onward~

How Do You Learn O&M? How Will My Character Learn?

You will have to find an Orientation and Mobility instructor and have them personally teach you O&M skills.

The O&M Instructor is a sighted adult who has gone to school for a bachelor’s degree and gone through O&M training themselves while blindfolded, usually fulfilling a certain requirement of hours (one program required 400 hours of O&M practice blindfolded before you could become certified), and apply for certification to teach O&M.

(Or, as is the process to become an instructor in the United States, where I am from. Becoming an instructor would vary in other countries, I’m sure)

To find an O&M instructor, you would reach out to your local school or foundation for the blind. Finding your nearest school for the blind could be done through…

Google search

Your Ophthalmologist (eye doctor) referring you to a school for the blind

A Social Service Worker reaching out to you and helping you contact the school

Possibly your school (as in grade/primary school, high school, university) reaching out to the nearest school for the blind on your behalf.

Unfortunately, there is not an abundance of schools and foundations, so your nearest might still be a far travel distance. My local school is a 45 minute drive away. For some it might a few hours away.

This is, again, a U.S. experience, because our land mass is spaced out, and something like a six hour drive feels like nothing to most people (although is highly impractical and very difficult to a blind person who cannot drive themselves), but in other countries a six hour drive would mean crossing several borders, and other countries have different social programs.

There is not a full and complete database of every available school for the blind either, no one website to find every possible option. For example, the school I went to wasn’t listed in most of the website resources I found, even though it has seven branches and locations.

This is more a complaint at the real life struggle to find disabled services, that there are few comprehensive resources out there. If you ask me, it should be made significantly easier to find and access your local blind communities. Accessibility and disabled services should be easily available everywhere.

If your story is based in a real world location, googling ‘school for the blind (city/county/country)’ should suffice in finding the one most local to your setting.

What might a school for the blind provide for your character?

Well, on top of helping your character connect to an O&M instructor, a school for the blind might provide other rehabilitation classes and access to additional resources.

Those rehabilitation classes could include lessons on:

-Reading/Writing Braille & using brailling machines

-Technology classes for screen readers, magnifiers, etc on your computer and smart phone.

My local school has separate classes specific to Andriod, iOS, JAWS, Zoomtext Fusion

-Independent Living skills (cooking, cleaning, organizing, planning how to get groceries and medications)

-Self Improvement (dancing, art, music, self defense. These were classes my school taught)

The additional resources form these schools might include-

Referrals to counselors for coping with vision loss

Access to their audio-book and braille library

Access to magnifier devices, brailler machines (think of a typewriter for writing braille)

Some schools also offer grade-school or high-school education, meaning blind children/teens learn there instead of a mainstream school.

Some schools have lodgings for clients to stay at while going through rehabilitation, especially if the vision loss is sudden and severe. They live on-campus and take part in classes. Other schools only have day classes offered and you need to find transportation for every visit. Many schools might have a rehabilitation specialist or O&M instructor visit you in your home.

My local school did the last two. They had on site classes, but the school is a 45 minute drive from me, so I only visited a few times. They were able to send an O&M instructor to me.

On Wednesdays at 3 pm she would drive to my house and give me lessons on using my cane. Those included her driving me to different locations to practice certain skills (like using stairs and escalators at the mall, or crossing a moderately busy intersection, or visiting a bus station to practice boarding a bus safely and communication with a bus driver where my stop was).

She also brought multiple different types of canes for new students to try out and determine which felt best for them.

The Many Types of Canes

Long Canes are used to sweep the immediate area in front of the cane user as they’re walking. This is the cane type that the general public is most familiar with seeing. There are several sub-types of long canes. They can also be called white canes or probing canes.

[Image Description: Man in business clothes traveling on the side walk with a white and red cane. End Image Description]

White cane can be a misnomer for two reasons: One, the concept of the standard cane for the blind can look different in different countries. In America, the standard is white with a red tip. In some countries the standard is an all-white cane. In some countries an all white cane might mean the user is blind while a white cane with a red tip means the user is deaf-blind.

Two, some companies like Ambutech allow customers to customize their cane colors and tips. Example: Molly Burke’s hot pink cane. My white cane with a purple tip. An all black or all sky blue or all red or all purple cane. A black cane with a blue or purple tip. Ambutech also allows customers to request neon-colored reflective tape to make their canes more visible at night.

Probing cane is not a term I’ve personally heard before, but it is a term Vision Aware uses on their website.

There are three main types of long canes:

Non-folding Canes: a cane that has no sections, cannot be folded or collapsed.

[Image Description: stock photo of man in business suit with a non-folding all white cane. End Image Description]

Folding Canes: The cane has 3-6 sections depending on its height. The taller the cane, the more sections it has. The sections are separate pieces that are made to snap together and are held together by a strong elastic rope inside the sections.

[Image Description: a folding cane with four sections, white with a red tip, and a rolling marshmallow tip. End Image Description]

Telescopic Canes: in which the sections slide into each other, similar to a telescope/spyglass, rather than pulling apart and folding. The handle is the widest section, and the tip section is the thinnest.

[Image Description: Three stacked images of a blue telescopic cane. First is of the cane completely collapsed. Second is of the sections partially sliding out. Third is the cane sections completely out and locked.]

Beyond that is also the Identification Cane. The function of this cane is to visibly identify the user as blind. It’s not used for O&M the way long canes are, there is no sweeping out the next two steps. It can be used as a support cane, however.

It’s appeals most to the elderly who not only make up a huge percentage of the blind community, but might also benefit most from having both a support cane and an identifier for their blindness, in case they need assistance.

[Image Description: identification cane with curved handle. All white with red tip. End Image Description]

A note: From what I’ve heard in the blind community, some people prefer solid/non-folding canes over folding or telescopic canes. The reason for this is that solid canes transfer vibration better than folding or telescopic canes. It’s said that the more sections a cane has, the less precise the vibrations are.

Some cane users train themselves to understand the vibrations of the surfaces their canes are touching. It tells them what kind of surface they’re on (wood vs. marble vs. concrete), if there are nearby objects to their cane. While I rely somewhat on cane vibrations to tell me what surface I’m walking on (more on that later), it is beyond my current O&M abilities to use cane vibrations to sense nearby walls or objects.

Cane vibrations are just an additional information-sense to add to the others in use, and extra bit of data input.

Parts of the Cane: Materials, Handle, Tips, Sections, Elastic Band

Material

The three most common types of materials used to make canes are aluminum, carbon-fiber, and fiberglass. Each material has some drawbacks and benefits.

The ideal cane is lightweight and durable. It should be strong enough to withstand hitting something solid without bending or splintering.

Aluminum is strong and durable, but heavy. If it’s damage, it’s more likely to bend than break entirely. A bend can be straightened out, but it takes considerable strength.

Carbon-fiber is lightweight and durable. It’s stronger than fiberglass, and it can bend out of shape rather than splintering.

Fiberglass is lightweight but a bit rigid. If it breaks, it splinters.

Handles and Elastic Bands

While some canes can have specialized grips (plastic, wood, corkboard) the most common handle material is a black rubber handle that is about ten inches long, give or take. In the previous photos you’ve seen, the canes have had black rubber handles.

Here is an example of a cane with a wood-mesh material used as the handle.

[Image Description: a four section white cane with a red tip and a orange wood mesh handle, with black elastic band attached. End Image Description]

The benefits of black rubber handles over others are that it’s easier to hold onto, especially if your palms are wet or sweaty, than a plastic or polished wood handle. It also wouldn’t show the indents or scratches from wear and tear daily use. I’m guessing that is cheaper to make on the manufacturing standpoint, and thus is conveniently the standard.

Pay attention to the black elastic band attached to the handle in the above photo. Notice how it has a tied off loop? That is so that when the cane is folded, that loop can be stretched over the folded sections to hold it together.

[Image Description: a four section folding cane folded up with the black band around them. End Image Description]

Additional benefits or functions of the elastic could be to use it as a wrist strap while using the cane, or hanging it up on a hook while not in use. I tend to have my cane folded up and tuck my wrist under the strap to hold it more securely while carrying it. Images of that ahead in my cane-isms section.

Cane Height

Ideal cane heights depend on the user. For most users, you want your cane height to be to your shoulder, give or take a few inches. You might need a longer cane if you are a fast walker with long strides, or a shorter cane if you prefer to hold your cane at a lower angle than is traditional.

What I mean when I talk about holding your cane at a certain angle is that the standard is to hold your cane handle in your dominant hand and position it in front of your belly button, moving it side to side with each step. Traditional grip methods are holding your hand palm side up with your cane in hand, or to hold the cane at the section joint closest to the handle with what is called the pencil grip, holding the cane like a fat pencil.

Depending on the height, a cane can have anywhere between three and six sections. Longer canes have more sections. The top section includes the handle, and the last section includes the stripe color (traditionally red, unless customized) and the tip.

The sections of the cane are generally slightly reflective, regardless of color. If you hold a cane up to the light you’ll see tiny specks of light reflected back, almost like very fine, tiny particle glitter paint. This detail is important in cane production because it makes the cane more visible at night, especially if something like car headlights reflect off it while someone is crossing.

Additional visibility at night can be added by wrapping stripes of reflective tape along the shaft.

Cane Tips

There are several different tip options for canes.

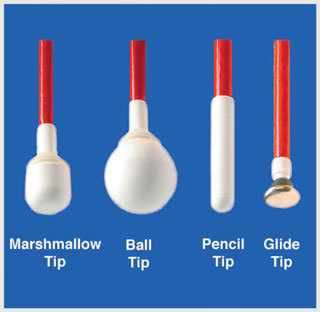

[Image Description: four different types of cane tips on a blue background with labels. From left to right: marshmallow tip, ball tip, pencil tip, glide tip.]

[Image Description: a rolling marshmallow tip with a blue background. End Image Description]

[Image Description: Bandu basher tip with a white background. For anyone not familiar with the name, the long, curved cane tip that looks like a hockey stick. End Image Description]

Some of these tips are better for the tap-tap method of cane travel, as in tapping the spots where you plan to step. They can also be used to feel out the shapes of objects, stairs, etc.

marshmallow tip, pencil tip,

They should not be scraped over surfaces, the tips will wear down much faster than they should. There are better tips for rolling over surface

Some tips are better for the rolling method of cane travel, which is the method I use. They aren’t great for tapping, but it can be done in a pinch.

rolling marshmallow tip, ball tip, glide tip

The Bandu Basher tip, the hockey stick shaped tip, is best for hovering an inch off the ground and lightly tapping objects. It could be tapped. It should not be scraped over the ground like a rolling tip. It hovers.

After enough use, the tips will wear down and need to be replaced. The part of the tip that has the most contact with the ground, usually the edge of the shape, gets scrapes, sands down, and eventually begins to look like it was shaved off while still having bits of plastic still gripped to it.

Never fear, cane tips can be removed and replaced when they wear out, replacing the whole cane is not necessary.

Some tips slip on or twist on. Others hook on. By hook on I mean that the elastic that keeps the cane sections together also has a loop at the tip end that a hook onto and stay held into place. Look back at the photo of the rolling marshmallow tip and you will see the hook that attaches to the black elastic.

Cane tips sell for about 5 - 10 U.S. dollars, plus shipping, so it’s advised to buy several back up tips with your cane. I replace my rolling marshmallow tips once every six to twelve months. I don’t know if that’s considered too much or too often. The last time I needed to replace mine was June 2019 (It’s July 2020 at the date of writing this, but I’ve hardly left my home for the last six months because of COVID-virus related quarantine/social distancing.)

Sensory Details/Describing What Using a Cane Feels Like

Every surface type feels and sounds different when tapping or rolling a cane over it. It’s this difference that tells us a lot about our environment.

It tells us when we stepped off the side walk onto the grass, when we’ve walked inside because the concrete changes to wood or carpet flooring. These little details become trail markers too, useful for places we anticipate traveling to a lot.

Example: A week before every semester in college, I would travel to each of the classrooms and learn necessary routes. I learned that certain paths had giant cracks in the sidewalk that would be distinct enough to use as a trail marker to where I was on a path, or that certain paths went from cement to gravel, or cement to brick.

Carpet: The sound is very soft, and if you’re rolling your cane across carpet it sounds like a quiet swish-swish-swish. Tapping sounds depend on how thick the carpet padding underneath is, the thicker the carpet the softer the sound. If there’s a lot of padding then taps don’t make much sound, but if the padding is thin or underneath the carpet is tile or concrete then you hear a louder thudding tap. It’s still pretty quiet. If you’re rolling the cane you would feel a little bit of drag, the cane moves slower over the carpet. The thicker or shaggier the carpet is, the more drag it has.

Wood floor: Cane tips make rumbling sounds when rolling over wood floors. The smoother the wood, the less it rumbles. There’s a little vibration moving from the cane tip, through the cane and into your hand as you roll over wood planks. Very small. The more sensitive you are to vibrations, the more you feel it. Tapping makes hallow, thudding sounds on the wood. Sometimes they sound a little snappish if you’re tapping harshly. You feel stronger vibrations when tapping. Older wood feels softer, with more give. New wood is stronger, more vibrations in the cane.

Tile:It depends on the size of the tiles and the wideness of the grout lines, but it’s not a pleasant feeling. Tiles have grout lines, which are little divets between the tiles. The smaller the tiles or rougher the grout lines are, the more the cane vibrates in your hands. Every bump is felt running from the cane to your hand. The sound is a little grating too. Imagine fifty sets of stiletto shoes walking on tile, that’s what it sounds like when you roll your cane over rough, small tiles. Larger tiles with smoother grout lines aren’t so bad. Tapping the tile with your cane sounds like one really loud step of a stiletto heal, one step for each tap. Tile floors are usually found in bathrooms, kitchens, and industrial locations where the room is going to have harder walls (more tile, concrete, etc) and few furniture, so the room echoes more.

Linoleum: is a smooth even surface. It feels like your cane is gliding when you roll it, barely feeling any vibrations. The rolling sounds are very soft because of the lack of bumps, however tapping sounds are a bit louder. Not as snappish as tile or marble, but almost.

Marble: is similar to linoleum in its smoothness. Your cane glides when rolling. Tapping sounds are sharp. Because marble floors are common in high end malls, luxury homes, and fancy office building entries, places that usually have high ceilings and hard walls with minimal decorations and minimalist furnishing, those sharp tapping sounds may echo. Assuming there isn’t too much noise and the environment is relatively quiet.

Concrete: (I’m referring to concrete found in parking garages and industrial buildings, not sidewalk) It depends on the age of the concrete and how it’s maintained. Old concrete with lots of cracks and mini-craters feels very different from smooth concrete that was set less than a year ago. With old concrete there’s a rattling sound as your cane tip rolls over the bumps and those vibrations travel up your cane. New concrete can feel similar to marble or linoleum. The taps are loud thuds on dull concrete and sharper on new concrete.

Sidewalks: are made of concrete, but in my experience they feel a little different than the above example. Sidewalks have a grittier surface, they’re slightly rougher, more dry. There’s a bit more rolling cane vibration with sidewalks and the taps have more of a thud sound. And because they’re outside, you’re unlikely to hear any echoes unless you’re walking in an alley or between buildings.

Asphalt: is one of the worst surfaces in my personal opinion. Asphalt is the material used in roads and it’s made to be rough and gritty so that car tires can grip onto it and not lose traction while driving. The older and more damaged it is, the rougher it is. Because it’s rough the vibrations are much stronger, sometimes irritatingly so. I can’t roll my cane over asphalt because the bones in my hand can’t handle those kinds of vibrations, so I almost always use the tapping method instead. The sounds are gritty and dull. Unfortunately, asphalt is an unavoidable surface, unless you can find a way to never need to cross a street or walk through a parking lot.

Note: the white or yellow lines that have been painted into asphalt sometimes feel smoother because of the material they’re made of and because they’re added after the asphalt has been laid down.

Note: There’s something called tarmac which is similar to asphalt, used for a similar purpose, and more common in the U.K. (I believe) but I can’t say that I’ve ever knowingly walked on it so I have no personal experience to give you.

Gravel: Another one of those evil surfaces. Gravel is just loose rocks and they’re common in rural roads, driveways, some landscaping. The looseness of them is what makes them untrustworthy. It makes a crunching sound. If you roll your cane, you’re likely to end up tossing small bits of rock and dust here and there. If you tap, you’ll hear the crunch but your brain might not translate that into “it’s gravel” until you’re walking on it and only realize when you walk over it and the sharp rocks begin digging into your shoes.

Wood Chips: I don’t have any experience with this since vision loss and getting a cane, so I’m using my memories of being on the playground in grade school because the surface on the playground was wood chips. I’d say wood ships are a love child between gravel and wood floors. The surface is loose and rolling your cane over it would kick up loose chips and dust. It would probably sound similar to walking on sand I think, because wood chips are much softer than gravel but not as consistent as wood. If it’s rained recently, then the waterlogged wood chips sound even softer.

Hard Dirt: I’m thinking dirt roads here, which are a lesser evil to asphalt and gravel. They can be rough like all roads, but the material isn’t has hard and solid. Rolling your cane will kick up dust on a dry day, but if it rained a few days ago you might hear a soft crunch as you roll over wet dirt. Tapping will have a very soft thud.

Soft Dirt: Think gardening dirt. Because it’s so soft, it makes very little sound and is easily kicked up. There’s a bit of drag, about the same or slightly more drag than grass or sand. Tapping has almost no sound but you might feel a slight give as your tip lands in the dirt, a slight resistance as it sinks in.

Mud: Yuck. I’m imagining this getting in my cane tip and how gross it would be after. Sound and feeling depend on how wet the mud is. Wet mud sounds slurpy. There’s more squish if you roll or tap your cane. Your character might not identify it right away until their shoes begin slipping as they walk over the mud. This is a personal experience. Drier mud sounds soft and feels almost solid underneath your cane. Wetter mud has more drag for a rolling cane. Muddy areas are also generally uneven because top soil has been displaced, so muddy hills and fields have unexpected but usually subtle changes in elevation.

Puddles: have both a slurpy and splash-splash sound. The slurpy sound is more common with rolling cane techniques. The splash sound is more common with tapping. The deeper the puddle, the louder is sounds and the more drag you experience. I am not fond of this texture/experience.

Snow: I have zero experience with snow since the development of blindness. So no experience of what it’s like to walk through with a cane. This is something I hope a blind reader can inform me on so I can edit this at a later date. My best guess is that it has a soft crunch, softer than the crunch of shoes in snow. A lot of drag too. Rolling through snow would probably be near impossible, especially if it’s deep snow or hard packed. Again, my best guess. The last time I experienced snow was when I was twelve.

Grass: One of my least favorites personally. Too much drag. Worse than shag carpeting. It’s very soft and doesn’t make much sound either. Like a crisp crunch you can barely hear. If the grass is wet or frosty you hear it a bit more crunch.

Surface with fallen Autumn leaves: Leaves everywhere! This is a bit dependant on whatever surface the leaves are on. It would soften the sound of cement, but there would be a louder crunch on grass. If the leaves are big and very curvy/pocketed then they’re easy to push aside. Smaller, flatter leaves don’t push as easily. The driest ones will crunch under your cane. It’s fun sometimes, if you’re the kind of person who likes stepping on leaves on purpose, but if you can’t see the leaves it might lose some of its fun and be more unexpected.

Sand: I’ve never personally taken my cane to the beach, despite living so close to the coast. The reason is because beach sand is so squishy and loose that it’s already impossible to stay steady on your feet. The sand is always sinking under your feet, unless you’re next to the water line and the dampness has made it firmer. So a cane isn’t very useful to me at the beach. Not to mention that sand isn’t something you want inside your cane joints if you want the cane to last. Sand will erode and damage the joints, regardless of if they’re metal or plastic. If I were to take my cane to the beach, it would make the softest crunching-swishy noise of sand sliding over sand, similar to what your footsteps sound like on sand, but possibly even quieter because canes are lighter.

Side Note: My mother sarcastically asked about rolling your cane through dog poop or gum left on the floor. Can’t say I’ve ever rolled through it, so couldn’t tell you. Use your imagination I guess, Mum

The Invention of Tactile Paving

These are amazing! Tactile Paving are those yellow (or sometimes grey) bumpy squares you see on ramps leading into parking lots or when crossing the street. In 1965, Japanese engineer Seiichi Miyake used his own money to develop a tactile brick that you could feel even when walking over it with shoes, and he designed this because a friend of his was losing their vision and he wanted to help. These are amazing, and accessible to everyone, even the blind who don’t have a cane or guide dog. These are literal life savers. Before I got my cane, if I felt those bumps under my shoes I knew to immediately stop because I was about to walk into the road. Because less than 10% of the blind community uses canes or guide dogs, this is the most accessible form of blind aide available.

[Image Description: a yellow rectangle of tactile paving in front of a ramp leading into a parking lot. End Image Description]

Note: similar detail, most doors in commercial buildings (in my localized experience) have a metal plate on the threshold to hold the door in place so there are no cracks underneath. The metal scraping sound when you roll or tap your cane on it is distinct but temporary and non-repeating, so it’s a good indication that you’ve reached and passed the threshold.

Blind-isms

I have a section in this guide about blind-isms, but these ones are focused specifically on cane use.

-Do. Not. Touch. My. Cane. Don’t. Just fucking don’t.

-The above ism comes from the fact that our cane is our safety net, an extension of our body, our eyes, the one thing that makes sure we’ll get somewhere safely. For that reason, blind people hate having their canes (or their on duty guide dogs) touched by strangers, acquaintances, friends we’re not very close to, some family members.

Important Note: That is a universal thing for disabled people. Don’t. Touch. Their. Mobility Aides. It’s assault. Touching someone’s wheelchair or pushing them around without their expressed permission is assault. Moving their wheelchair while the user is currently standing is assault. (Most wheelchair users are not paralyzed, but they still need the wheelchair because of their medical condition, which is not your business to know). It doesn’t matter if the wheelchair is in the way, the disabled person needs it right there, do not touch it. Touching or grabbing someone’s support cane or their long cane is assault. Touching or moving someone’s walker is assault. Touching, poking at, or tampering with someone’s hearing aids is assault. Touching their oxygen tank or cannula is assault.

Back on topic-

-Idle motions with your cane while waiting in line. I often rest my chin on my cane or lean on it

-twirl my cane like a staff when I’m alone and no one can see. I would not ever do this in front of anyone because I don’t want anyone thinking it’s a toy or they can just touch or grab it. I’m just a little childish and bored sometimes and idle motions are a common thing for people with ADHD.

-When carrying my folded cane inside (like say a store) I hang it from my wrist by the strap.

-Keeping my cane within arms reach at all times, even in situations where I don’t need it currently. Example: if we’re doing a classroom assignment where I need to leave my desk, I know the classroom well enough to not use my cane, but I won’t leave it at my desk, ever. (This does not apply at home. And in the homes of a very few, very trusted friends I will leave it somewhere I deem safe.)

-Having a set, specific place in my home (living with my immediate family, who almost never have guests) for my cane. In my case, it’s the top of an antique dresser in the living room, across from the door. It has a little bowl for my sunglasses as well. If I move out and have roommates, my cane will be in my room.

-Love me a bag or backpack that has enough space to discretely store your cane, but most of my bags cannot do that.

-People with folding canes develop a muscle memory for folding and unfolding their cane, so they can do it without really thinking about it.

-Unfolding my cane: I hold the black handle between my thumb and palm with my other fingers folded over the remaining three sections, cane tip pointing up. I slide the elastic over the tip, loosen my four fingers and roll my wrist to the side. The red colored section unfolds first and snaps into place with its neighboring section. I roll my wrist in the opposite direction so the next white section can unfold and snap into place with it’s neighboring section. Roll it back in the first direction and the third section snaps into place with the handle. My four section cane is now unfolded and straight.

-Sometimes I just grab the black handle and let the sections fall and unfold as they will, but this is less controlled and risks your cane bumping into something or someone.

-Folding my cane: I start with the black handle, lifting it up so the joints unlock. I fold it down, grab both sections in my hand and lift the second section away from the third and fold it over. Wrap my hand over all three sections and unlock it from the red section.

-Because I have a four section folding cane, the cane tip and the handle are on the same side while the metal joints are on the opposite side. Those metal joints are what my elastic slips over.

-A three or five folding cane will have the head of the handle (and its elastic) on the opposite side of the cane tip, and you will be folding the elastic over the cane joints and tip.

-A six section cane has the tip and handle facing the same direction like the four section cane.

-People with non-folding canes like leaning their canes up against walls and other objects when not in use. Corners are popular, the corner of a desk up against a wall too.

-But oh god the frustration when the cane randomly rolls out of place and hits the floor, it’s a combination of “Not again” and “did that really just happen” and “you had one job. one job.”

-Sitting with our cane tucked between our legs. Picture a bit of man spreading, the cane tip leaned against the side of our foot to keep it stable and the cane leaning against our shoulder or opposite knee, possibly also held securely with our fingers too.

-The no-manspreading alternative of that is with the cane leaning against our shoulder, cane tip resting on the toe of our shoe or the outside of it, held securely with our fingers or our arm wrapped around it, elbow hooking it.

(Okay, a while back I was looking for photos of someone using a cane to use as a reference for drawing Ulric. I only found three, and two of them were Daredevil promo photos. Which, no offense to Charlie Cox, but he is not blind and he does not use a cane in his daily life, he does not have that relationship a blind person has with a cane and the concept of a fifth limb, and it shows. So the photos were stiff and unusable, so I had to like use several photo references of different poses and Frankenstein them together to get what I wanted.

And I still haven’t finished the painting... fuck)

-In a car with a non-folding cane:

-Right passenger seat- The cane tip goes all the way into the corner of the foot well to the right of my feet, with the handle resting over my right shoulder or on the seatbelt. It pokes a bit past my headrest. The longer the cane, the harder it is to tuck into a car.

-The U.K. / Austrailian / New Zealand / Japan version of this (because they drive on the left side of the road with their drivers seats on the right side of the car) it’s like this: Cane tip in the foot well to the left of my feet, handle on my left shoulder or on the seatbelt.

Backseat: the absolute worst. There’s less foot well room, and if you’re in a sedan there is almost no room behind your shoulder for the handle. I position my cane diagonally with the handle on the shoulder closest to the door and the tip next to the foot closest to the middle.

-For this reason, no one with a non-folding cane will want to be sitting in the backseat.

About Guide Dogs

While my knowledge of guide dogs is limited only to what I can research and not personal, I will give you some basic facts and practical knowledge from said research.

Guiding Eyes for the Blind estimates that there are 10,000 guide dog teams out there in the world. That makes up 2% of the blind and visually impaired community.

Guide Dog Training

Becoming a guide dog is the most difficult form of dog training there is. The majority of dogs who enter guide dog training wash out and either become family dogs or go into a different type of service dog training, like medical response or PTSD/anxiety response, or possibly become therapy dogs, which is a career altogether different from being a service dog.

Guide dogs go through two or three years of training, which includes puppy training, basic socialization, proper behavior when on duty and actual guide training. Most service dogs only go through a year to a year and a half of training before they are partnered with a disabled handler.

Between the cost of training, the cost of housing and feeding the dog and the cost of vet bills from birth until being partnered with a blind handler, the overall cost of a guide dog is something like 30k to 40k. While most service dog training organizations require handlers to fundraise and pay for the cost of training (usually something like 15-30k), guide dog organizations give their dogs to qualified blind clients for free. These organizations pay for the dog costs through their own fundraising and charities. Fortunately for these organizations, guide dogs are a highly respected field and have a lot more charity directed their way, while other service dog types have less public interest when it comes to charity.

Guide Dog organizations have an application process, requirements, and a wait-list before you can be partnered with a guide dog.

Requirements to get a guide dog are (usually) as follows:

Must be legally blind (as in not visually impaired, but legally blind) and have had at least six months of O&M with a cane and demonstrate enough O&M stills to navigate by oneself. They also require you to be responsible enough to independently care for a dog, able to keep up with training and retraining of the dog, as well as financially able to handle food and vet bills (which are at least a few thousand dollars every year).

The reason for cane training before getting a guide dog is because the dog cannot do everything for you. You, the dog handler, are responsible for knowing where you are and how to get where you need to be.

The dog can’t read stop signs or tell when a light is green or red, nor do they have GPS to find a brand new location nor can they learn that route on the first try, nor will they know exactly where you want to go when you say “Starbucks” or “library” or “school” or “mom’s house” and guide you all by themselves. That falls on you, the dog handler, having enough orientation and mobility skills to know when a street is safe to cross and knowing how to learn new routes and how to keep on route and make sure you make the correct turns. A guide dog can’t communicate with bus drivers for you either, they don’t know which number bus to use or what stop to choose. That falls on the blind person’s own skill.

Other Guide Dog Resources

Molly Burke is a guide dog user and has made several videos about what kind of work guide dogs do, her personal experience being a guide dog user for over ten years, how she got a guide dog, specific commands, unique experiences with things like travel, etc. She has a playlist all about guide dogs, but here are some of my favorite videos.

How Guide Dogs Guide A Blind Person

Guide Dog User Answers the Most Googled Questions about Guide Dogs

How I Met My First Guide Dog

Final Thoughts:

There is a lot more to be said about Orientation and Mobility, such as:

How do you safely cross the street with a cane?

How do you learn new routes?

How does getting a cane significantly change your life?

How do family, friends, and strangers react to you “suddenly” having a cane?

I could also write a ton on other tools the blind community relies on so strongly, such as screen readers, magnifiers, etc. In fact, I originally promised to include those in my master post when Part Four was titled Part Four: What Your Blind Character Needs to Survive and Not Die. However, this guide is ages long and it feels better to focus on this specific topic for here.

Did you like this guide?

Consider checking out my other guides, links of which can be found on the master post here.

Follow my blog, I write and curate writing advice guides outside of blindness, I reblog writing memes with image descriptions, reblog soothing aesthetic photos with image descriptions, talk about disability, lgbtqa+ issues, ableism, and mental health.

If you want to further support me, this is the link to my ko-fi (however there is no such requirement nor pressure to do so, and please don’t worry about it, especially if you are in a financial situation that can’t afford it)

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Writing in Braille - A Quick Guide

I admit to being a little confused about this question at first, but it reminded me of a post I wanted to write about how blind people can read and so decided to answer a similar question about writing here.

To be honest, I feel like this is a question that could be researched on one’s own, but I get why someone would ask.

Braille is a code language and not raised print. It also has nothing to do with Sign Languages. Just so it is clear. Braille can be used to write the alphabet, abbreviations, and symbols. Different kinds of Braille are used for math and music.

If you can read Braille, it makes sense that you can write it as well, correct? There are actually a few options for writing Braille.

1. A Brailler - This is basically a typewriter if it had less keys. The most well known is the old Perkins Brailler, which is traditionally a grey color. They were very heavy when I was using one and come with stick stick paper that is a light brown. You roll the paper in and the process a similar to a typewriter if you have ever seen one. Then you can use keys 1, 2, and 3, separated by a space bar, then keys 4, 5, and 6. Here is a video showing a Perkins Brailler.

The Brailler has improved since. There is even a Smart Brailler that contains a screen and audio. (You can find information about it in the second article I link to below.) I do notice a lot of people still use the regular Brailler and there are lot more demonstrations for it on YouTube for it than for the other kinds.

2. A ‘note-taker’ - This is a small, compact Braille keyboard with refreshable Braille display. There different types of these devices (Braille Note, Braille Lite, and probably many that are more recent) but they are basically small computers now. You can email and use the internet, etc. My friend used to take notes in class and write papers. It has audio feedback so you normally use it with earphones. Despite the nane, you can do more than takes on it. They can be used with Braille or QWERTY keyboard. I think they came out in the early 2000’s.

3. A slate and stylus - People compare it to a pen and paper. I have never used one myself. I know you write backwards when using it. Here is a video about the slate and stylus.

4. Typing on a computer QWERTY keyboard and then translating it into Braille, or translating Braille from Braille to computer print.

A few important things:

Yes, you can type even without seeing the QWERTY keyboard. Technically, no one is supposed to need to look when they type. Audio from a computer or phone can also help someone as they type.

The machines used to translate text to Braille is very big and very loud, unless it has been updated since. Which I doubt.

Braille books are very big and much longer than print books. Therefore, even short things translated into Braille can be longer than one expects.

Here is an article with information about the Braille systems and grades, the slate and stylus, the Brailler, and note-takers and the evolution of them. Article link.

Here is an overview of tools use by blind people that contains some extra information. Article link.

Here is a video overview of all this stuff that Molly Burke made. She has a cool Brailler that is pink and seems much lighter, even as she says her Brailler is older compared to things people use now. Her stories should give you a good idea of what using Braille is like. Video link.

Molly covers this in her video, but today’s children are unfortunately less likely to read Braille and rely only on the advancements in audio information. Not as many people know Braille. This is a shame because it can help reinforce grammar and spelling and also help that person read if they ever lost their hearing later in life. Learning Braille can also allow people to label objects around the house.

I hope this helps. I’ll try to write my post on options blind people use to read soon. Would anyone be interested in more information?

84 notes

·

View notes

Text

How the Braille Alphabet Works?

The braille alphabet is used by people who are blind or visually impaired as a basis of the larger braille code for reading and writing. Blind kids and adults read braille by gliding their fingertips over the lines of embossed braille dots and write braille using a variety of tools including the Perkins Brailler. People who are sighted can learn braille as well, either by touch or using their vision. A great place for everyone to begin learning braille is with the braille alphabet.

1 note

·

View note

Text

i got my perkins brailler today and i'm like a lil kid at christmas just typing away on it hfkdkdhdbdkf it's ridiculous

#ive always wanted a typewriter hdkdkdhfkf mum joked that i look a proper writer now when i carried it around earlier#next chapter of tiwmug will be written and posted in braille#no one cares rebeccah

1 note

·

View note

Text

How To Read and Write Braille | Department for the Blind

Braille is a tactile writing system used by individuals who are blind or visually impaired. It enables them to read and write through touch, ensuring access to literature, information, and communication. Learning braille opens up a world of independence and literacy. Here’s a guide on how to read and write braille.

Understanding Braille

Braille consists of raised dots arranged in cells. Each cell has up to six dots in a 2x3 grid. Different combinations of these dots represent letters, numbers, punctuation, and even entire words or phrases.

Learning to Read Braille

Familiarize with the Braille Alphabet: Start by learning the braille alphabet. Each letter corresponds to a specific arrangement of dots. For example, the letter "A" is represented by a single dot in the top-left position, while "B" consists of two dots in the top row.

Use Braille Books and Resources: Access beginner braille books, flashcards, and online resources. Many libraries and organizations for the blind offer materials in braille. Reading these resources will help you get accustomed to recognizing the dot patterns.

Practice Touch Sensitivity: Developing the ability to distinguish the dot patterns by touch is crucial. Practice reading with your fingertips, moving from left to right across the page. Start with simple texts and gradually progress to more complex materials.

Join Braille Literacy Programs: Enroll in programs offered by organizations like the National Federation of the Blind (NFB) or the American Council of the Blind (ACB). These programs provide structured learning environments and support from experienced instructors.

Learning to Write Braille

Get the Right Tools: To write braille, you need specific tools like a braille slate and stylus or a braille typewriter. A slate and stylus are portable and affordable, consisting of a guide (the slate) and a pen-like tool (the stylus) to punch dots into paper. A braille typewriter, also known as a Perkins Brailler, functions similarly to a traditional typewriter but produces braille dots.

Understand the Writing Method: Writing braille manually involves creating mirror images of the letters since you write from right to left on the back of the paper, then read from left to right on the front. The braille typewriter simplifies this by allowing direct writing.

Practice Regularly: Begin with simple exercises, writing the alphabet, and then move on to words and sentences. Regular practice will help you become proficient. Writing personal notes, lists, or diary entries in braille can make practice more enjoyable and practical.

Use Braille Translation Software: Modern technology offers braille translation software that converts text into braille. These programs can be useful for creating braille documents efficiently. Braille embossers (printers) can produce braille output from a computer.

Tips for Mastery

Be Patient and Persistent: Learning braille takes time and effort. Consistent practice is key to becoming proficient in both reading and writing.

Seek Support: Join a community or group of braille learners. Sharing experiences and tips can be motivating and helpful.

Utilize Technology: There are many digital tools and apps designed to assist with braille learning. These can supplement traditional methods and offer interactive ways to practice.

Conclusion

Braille is more than just a literacy tool; it is a means to independence and empowerment for individuals who are blind or visually impaired. By learning to read and write braille, one can access a wealth of information, communicate effectively, and enhance their quality of life. The journey to mastering braille might be challenging, but with dedication and the right resources, it is an attainable and rewarding goal. For more information and resources on braille literacy, visit the Department for the Blind.

0 notes

Text

I learned to touch type when I was 9-10, in Year 4. Before that we were doing computer lessons but there were no school computers with a screen-reader installed on them so I didn't make much headway.

However, I use Home Row and both hands to type because I was using a Brailler for four years before I got familiar with a qwerty-style keyboard, and writing with a Perkins Brailler requires both hands. It also requires more pressure than typewriter keys do, since you have to push the pins through the paper to make the Braille symbols via the combination of keys you're writing with, so typing on a keyboard is easier for me in that respect. I miss having a Brailler though.

Hold on, this is fascinating. Reblog this and tell me in the notes how old you are and if you ever had typing lessons.

37K notes

·

View notes

Text

Here is my public service announcement for today, if you want to get a cheaper at Perkins brailler try eBay I learn that today on Reddit also I learned that there was an old blind thank you Reddit that was useful. Now, I got a question here can someone help me think of a good way to convince my mom to let me purchase the 60-something dollar Perkins I want a Perkins brailler I can still see someone and right but I'm learning Braille and I eventually one of them to write it I have a slate and stylus if that's the only option but when I originally started learning at work my original Braille instructor told me that as a new Braille learner that slate and stylus might not be the best option because it's a little bit harder. So, I made it my mission to find an inexpensive or purchase my own trailer or find some way to get a loan or whatever it is, because they're expensive and I know why they're expensive they last basically and I want to actually get one so, I'm going to attempt to purchase the one on eBay but what I need from you guys is someone give me some tips, and suggestions on how to convince my mom to let me purchase it it's my money I'm allowed to spend it on what I like and that's not like three hundred or $900 like the other ones are give me the heck alone but also, it's about 60 something dollars, which is still a lot of money in something she probably might not want me to spend on that since I don't need it. So someone could help me please let me know as soon as possible.

0 notes

Note

hi! i’m writing a blind character for a story, and in the story she does a lot of administrative work. i was wondering how blind people type; do they use braille keyboards, or just normal keyboards but learned where all the letters are? do they dictate? thanks in advance!

It varies from person to person. If you went blind later in life you would likely learn touch typing: typing by subconscious muscle memory. It's pretty common and with a voice-over program, you could have it read back what you typed to make sure everything is correct.

There are braille letter stickers you can press onto each individual key for when someone is learning how to use a keyboard for the first time.

MaxiAids has a set of stickers for every key on the keyboard.

There is the Perkins Brailler, a mechanical Braille writer that works similar to a typewriter. There are modern keyboards with similar eight-button setups that connect to computers, tablets, and phones via Bluetooth.

Molly Burke did an awesome video explaining how Braille typewriters work and how you type with it.

There are keyboards that have Braille displays as well. There is a row of Braille cells with individually retractable slots. With those, you can read a line of digital text in Braille. They're great but they are super expensive.

Here is one you can buy from MaxiAids for the low-low price of $1,399

Dictation can be done either by having an assistant type out what you say (highly unlikely to have unless you're important enough in the business world to have a personal assistant) or by using a computer program.

Speech-to-text is great for sending text messages and emails. I cannot imagine using one for any larger projects like an essay or writing fiction, but there are definitely people who do it.

What method would your character use?

How old were they when they first had access to computers? Would she have learned it in grade school, high school, college, or after? Compare that age to when her vision loss began.

If she was in grade school after 2000 and had enough vision loss to have a secondary educator assist her in class, then they probably taught her to use a Perkins Brailler and to touch-type on a regular keyboard with stickers and a program like Mavis Beacon Teaches Typing.

Depending on how far into college she went, she might have been given access to a Braille keyboard like the one I linked above. It would belong to the college or a disability services program and they would loan it out to her while she was a student. After she's done, it returns to the program to be loaned to another blind student.

If she decided it was her preferred method of typing, she might choose to save and invest in one for personal use, or she might have her employer provide one to her for company use as part of the accommodations they're legally required to provide.

If she went blind earlier in life and finished her education before computers became a norm, then she used the Perkins Brailler but not a traditional keyboard typewriter.

If she wanted to learn to use the computer after vision loss, she would contact a local school for the blind and get specialized classes to teach her how to use a computer, including typing and using the screen-reader program. They would probably apply Braille stickers to her traditional keyboard at home or at work for her.

51 notes

·

View notes