#Peridexion tree

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

Bestiary, literary genre in the European Middle Ages consisting of a collection of stories, each based on a description of certain qualities of an animal, plant, or even stone. The stories presented Christian allegories for moral and religious instruction and admonition.

The numerous manuscripts of medieval bestiaries ultimately are derived from the Greek Physiologus, a text compiled by an unknown author before the middle of the 2nd century ad. It consists of stories based on the “facts” of natural science as accepted by someone called Physiologus (Latin: “Naturalist”), about whom nothing further is known, and from the compiler’s own religious ideas.

The Physiologus consists of 48 sections, each dealing with one creature, plant, or stone and each linked to a biblical text. It probably originated in Alexandria and, in some manuscripts, is ascribed to one or other of the 4th-century bishops Basil and Epiphanius, though it must be older. The stories may derive from popular fables about animals and plants. Some Indian influence is clear—for example, in the introduction of the elephant and of the Peridexion tree, actually called Indian in the Physiologus. India may also be the source of the story of the unicorn, which became very popular in the West.

The popularity of the Physiologus, which circulated in the early Middle Ages only less widely than the Bible, is clear from the existence of many early translations. It was translated into Latin (first in the 4th or 5th century), Ethiopian, Syriac, Arabic, Coptic, and Armenian. Early translations from the Greek also were made into Georgian and into Slavic languages.

Translations were made from Latin into Anglo-Saxon before 1000. In the 11th century an otherwise unknown Thetbaldus made a metrical Latin version of 13 sections of the Physiologus. This was translated, with alterations, in the only surviving Middle English Bestiary, dating from the 13th century. It, and other lost Middle English and Anglo-Norman versions, influenced the development of the beast fable. Early translations into Flemish and German influenced the satiric beast epic. Bestiaries were popular in France and the Low Countries in the 13th century, and a 14th-century French Bestiaire d’amour applied the allegory to love. An Italian translation of the Physiologus, known as the Bestiario toscano, was made in the 13th century.

Many of the medieval bestiaries were illustrated; the manuscript of the earliest known of these is from the 9th century. Illustrations accompanying other medieval manuscripts are often based on illustrations in the Physiologus, as are sculptures and carvings (especially in churches) and frescoes and paintings well into the Renaissance period.

The religious sections of the Physiologus (and of the bestiaries that were derived from it) are concerned primarily with abstinence and chastity; they also warn against heresies. The frequently abstruse stories to which these admonitions were added were often based on misconceptions about the facts of natural history: e.g., the stag is described as drowning its enemy, the snake, in its den; and the ichneumon as crawling into the jaws of the crocodile and then devouring its intestines. Many attributes that have become traditionally associated with real or mythical creatures derive from the bestiaries: e.g., the phoenix’s burning itself to be born again, the parental love of the pelican, and the hedgehog’s collecting its stores for the winter with its prickles. These have become part of folklore and have passed into literature and art, influencing the development of allegory, symbolism, and imagery, though their source in the bestiary may be frequently overlooked.

multicolored cats

Worksop Bestiary, England c. 1185

NY, The Morgan Library & Museum, MS M.81, fol. 46v

#studyblr#history#classics#christianity#catholicism#art#art history#medieval art#animals#birds#zoology#botany#trees#folklore#ancient greece#egypt#india#alexandria#basil of caesarea#epiphanius of salamis#bestiary#worksop bestiary#physiologus#unicorns#deer#ichneumonidae#phoenix#pelican#hedgehog#peridexion tree

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Just realized I never posted my marginalia-themed zine cover. I figured since the interior of this zine was nothing but random stuff created and collated through the Pandemic, I'd treat it like medieval monks treated their scraps of writing and art.

The title is not really a title. It's a magic square, meant to protect the contents inside of the book. I'd have used the more well-known Roman 'tenet' square but I didn't want to come across as a Christopher Nolan fan-zine.

[img id] A bold red cover for an art zine, accented with black, lime-green, and teal. The title, 'Crab Rare Arts Best', is set in a square that reads the same in any order. The black serif letters are decorated with red fields and lime-green dots. A green tree threads its branches through the title. Each branch has a silly little red leaf at the end.

Three stern, stylized doves perch in the branches. At the base of the tree, leaping among hills of crimson and bushes with red leaves, is a teal dragon with a red head. It flaps stylized red-and-teal wings. The dragon is eating a hapless dove head-first. The dragon's tail is floral and it has lion's paws for feet. Text beneath the dragon reads: H. McGill http://hmcgill.art. [/id]

52 notes

·

View notes

Text

Writing Notes: Medieval Plants & Stones

for your next poem/story

Agate - a stone that is used to find pearls. When divers want to locate pearls, they tie an agate to a rope and drop it into the sea. The agate is attracted to a pearl, and the diver can follow the rope to where the pearl lies.

Carbuncle - a red stone, and the name referred to several stones: the Oriental ruby, the garnet, etc. It is said to be found in the forehead of the asp or the dragon. Theophrastus says of it: "Its color is red and of such a kind that when it is held against the sun it resembles a burning coal."

Diamond - no harm can come when kept in a house, even demons cannot enter; comes from the East, where it is found at night by its shining. A person who possesses a diamond can overcome both men and beasts. The diamond does not keep the smell of smoke or fear iron. Only the hot blood of the he-goat can dissolve diamond. It is a miraculous medicinal substance formed by burning magnetic stone in a hot fire.

Fire stones - stones that burst into flames when brought close together; as long as they are kept apart, they are safe

Indian stone - a stone that can cure the illness called dropsy (i.e., a disease of excessive water retention) if it is tied to him. The stone will absorb the man's impurities, and in so doing, comes to weigh as much as the man. If the stone is then placed in the sun for 3 hours, the impure water will drain out of it and it can be re-used.

Magnet stone - or lodestone; attracts iron; can be used to determine if a wife is chaste; produces harmony between man and woman; enhances skill in argument; as a drink it cures the sickness called dropsy; powdered, it quenches fire. Burning a magnet stone produces a diamond.

Mandrake - a plant that shrieks when it is pulled from the earth; its roots grow in human form, male and female; it is of great use in medicine, but anyone who hears the plant's cry dies or goes mad. It was therefore a custom to tie a hungry dog to the plant by a cord and place a piece of meat beyond its reach. To get at the meat the dog tugs at the cord and drags up the plant, while its master remains safely out of hearing; it grows in the East, near the Earthly Paradise (i.e. garden of Eden)

Peridexion tree - a tree in India that attracts doves and repels dragons; doves gather in the tree because they like the sweet fruit, and because there they are safe from the dragon. The dragon hates the doves and would harm them if it could, but it fears the shadow of the peridexion tree and stays on the unshaded side of it. The doves that stay in the shadow are safe, but any who leave it are caught and eaten by the dragon.

Source ⚜ More: Writing Notes & References ⚜ Medieval Period

#medieval#writing inspiration#fantasy#writeblr#dark academia#spilled ink#writing prompt#literature#writers on tumblr#writing reference#poets on tumblr#poetry#creative writing#fiction#writing ideas#light academia#novel#lilla cabot perry#writing resources

190 notes

·

View notes

Photo

This dragon is probably pretty pissed off because the doves are hiding under a peridexion tree where it can't reach them. This is a pretty common analogy in medieval bestiaries where the tree symbolizes the church and the doves i.e. christians who stray to far from it fall prey to the dragon, who is the devil.

Guess what friends, it’s dragon time 🐲 !

It’s been a while since my last post, so I thought it was about time to bring medieval dragons back, and to show you, fellow humans of Tumblr, another depiction of those incredible creatures ! So here is a tiny dragon, desperately trying to scare off a couple of doves chilling under a tree (unless he is singing to them ? Reading some poetry maybe ? Hard to tell but in any case, the doves don’t really pay attention. Poor lad, nobody cares about him).

I always feel better when I stumble upon some dragon-related stuff so I hope you’ll enjoy admiring this lovely dragon as much as I do ! Let this little fella give you all the strength you need to go through this week. Have some dragon love, there is nothing better !

About the manuscript :

Bestiary of Guillaume le Clerc, Bibliothèque Nationale de France, MS. 1444B, fol. 254. Copied and illuminated in France, towards the end of the 13th century.

Previous post : I

121 notes

·

View notes

Text

Scattered concepts for Vindictus Virtuous (i.e. the 'mons thing). I'm happy with Peridia and Peatii; the others may be subject to adjustment.

Peridia is based on the peridexion tree, a mythological tree that was described in the Physiologus as attracting doves and repelling serpents. Any good Pokemon-like needs at least one cute plant girl.

Peatii (ignore the "Pearis") is the base stage of Phasiris, carried over from one of my two older Fakemon concepts. (The Holicite line is here, too.)

Misophyte doesn't like you.

Divini is inspired by fortune tellers' tables and the Witch of Endor, a figure in the Bible that frustrates Christian scholars.

Silkae is a smaller version of Ephraim's long-dropped "celestial being" form.

Fortuneko is the first "hybrid group" mon; representing symbols of both good and bad luck will do that to you.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Peridexion Tree / arbor peridexion. The Latin narrative of the Peridexion tree, elaborating on the original Greek versions of “Physiologus”, is a continuation of the story about doves. It takes inspiration from the Evangelic proverb about a grown mustard seed /Matthew 13:31, 32; Mark 4:32/ or from the tale of a snake afraid of the shadow of an ash-tree /Pliny XVI.13.24/ (Lauchert F. Geschichte des Physiologus. Strassburg, 1899). The Tree of Perindeus /oak of Perindeus in the Slavonic version of “Physiologus”/ grows in eastern lands. Its fruit is sweet and tasty. Doves take delight in the fruit and live in the tree. The dragon is the enemy of doves, but it fears the shadow of the tree. When the shadow falls to the west, the dragon moves round it to the east, and when the shadow comes to the east, he flees to the west. If, however, a dove happens to be outside the shade, the dragon would seize it. The bestiary extends the parallels, drawn in “Physiologus” between the tree of God the Father, between the fruit of the tree and Jesus Christ and his wisdom, the tree’s shade and the Holy Spirit; the doves and the faithful.

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Peridexion tree. Bestiary.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dragon Enemies

Panthers (and Cats)

In European Bestiaries, panthers were multicolored felines, their pets covered with white and black spots. Unusual, given that it's a cat, but it's said to be a gentle creature, with one notable exception. Dragons are said to be its enemies, and when the Panther is around the dragon will hide away in its den, while other beasts are drawn forth by the Panther's sweet smelling breath.

In an allegorical sense, the Panther is said to be symbolic of Christ, while the dragon represents the devil.

In Egyptian mythology, the cat is symbolic of Ra, and is shown fighting and slaying the Chaos Serpent Apep. Real cats are known to hunt and kill snakes, so this may be the source of this association.

Elephants

There is also an unusual animosity given between Elephants and Dragons. Dragons are said to hunt elephants, either with the intention of eating their calves or drinking their blood (dragons run hot, you see, so they need the cold blood of an elephant to cool off. Dragons kill elephants by constricting, sometimes hanging down from trees to form a noose. In some accounts these hunts are successful. In others, the elephant collapsing crushes and kills the dragon. When an elephant gives birth, she does to in the water, to protect her child from the dragon.

Burning the bones of an elephant is also said to drive away serpents.

Deer

According to bestiaries, Stags were the enemies of snakes and serpents. Stags would go out of their way to track snakes down, luring them from their holes by spitting down water and luring the snake out with their breath. If ill, the Stag would eat the snake, then go drink water to cleanse itself of the snake's poison.

Birds

Seen in mythology across the world is the animosity between birds and serpents. A potential explanation for this is that in nature birds will prey upon snakes, and as representations of the sky (birds) and earth/water (serpents), it would fit that they'd be seen as natural enemies.

In Hindu and Buddhist belief, the Garuda is the enemy of the Naga people. The mother of the Naga, Kadru, was the sister-wife of the mother of Garuda, Vintata. Kadru and the Naga enslaved Vintata and Garuda, so when the great bird received a boon from the gods, he asked that the Naga be his prey.

In the tales of Sinbad, the Roc is said to prey upon giant serpents of a diamond filled valley.

Thunderbirds in North American myth are the enemies of the Horned Serpents, with the birds preying on the serpents, and the serpents eating the birds' eggs. In some tales, the Thunderbirds predate the serpents to extinction. Interestingly enough, Thunderbirds are said to use a different species of serpent, the Haietlik, as a hunting weapon.

In Norse myth, the serpent Nidhogg and the unnamed eagle of Yggdrasil are often locked in argument and insult.

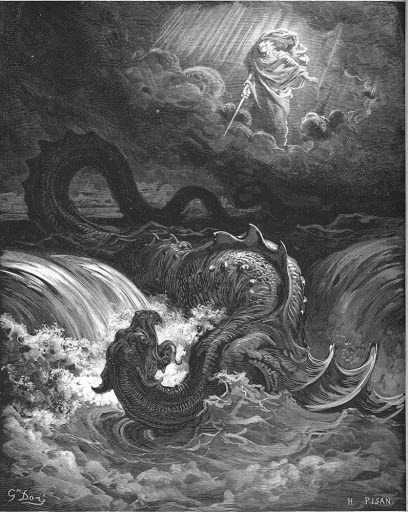

Storm Gods

Study world mythology, and you're going to notice a pattern. Storm and Sky gods fighting against vast serpents, often denizens or personifications of water. This motif was named the Chaoskampf (struggle against chaos), and can be seen across cultures, especially those descended from the Proto-Indo-Europeans.

In Greek mythology, Zeus battled and slew (or imprisoned) the earth dragon Typhon. Over in Japan, Susanoo killed the eight headed Yamata-no-Orochi. Marduk killed Tiamat, then fashioned the world from her corpse.

Like with birds, this conflict may be centered around symbolism. If dragons represent the untamed nature of the earth and sea, then the civilized god of the sky and, through lightning, fire being their foe seems obvious.

Weasels and Mongooses (and Water-Snakes?)

As I have said before, dragons are ultimately just fantastical snakes. So it would seen logical that the natural enemy of the snake would continue to be the natural enemy of the dragon.

In the real world, mongooses often prey upon snakes. This can be seen reflected in folklore, where the weasel (not actually related to mongooses, but similar enough in appearance where the ancient European would probably not know the difference) was said to be one of the few creatures capable of defeating the Basilisk.

In medieval bestiaries, creatures called the ichneumon and the hydrus were said to be the enemy of serpents and crocodiles. They would cover themselves in mud and allow themselves to be swallowed, at which point they would chew their way from the predator. But while the ichneumon seems to be a mongoose (it was also called the Pharaoh's Rat), and the hydrus seems to be the same sort of creature, both are considered serpents, and are often drawn in the same way their draconic victims are.

Plants

Various plants are said to ward against dragons and serpents.

In some variations of the myth of Saint George, he took refuge under an orange tree, which the dragon could not approach.

According to bestiaries, doves would take refuge in peridexion trees, the shadow of which dragons were said to fear and avoid.

Rue was said to be one of the few plants which could survive the deadly nature of the Basilisk.

According to Chinese belief, the dragon dislikes both the Wang plant as well as the Lien tree, though the exact identity of these plants are uncertain.

Then, in a twist where dragons are said to be the enemy of a tree, Norse Mythology has several dragons which are chewing the roots of the world tree Yggdrasil, and will one day kill it.

175 notes

·

View notes

Text

[Atmos. BM|Bandcamp] Peridexion Tree - Demo III https://t.co/VfmuZgHt0v pic.twitter.com/cKEFIC0TqW

— Ambient BM Music (@ambientbm_bot) November 26, 2018

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Pinned to Medieval Images: Doves roost in a peridexion tree, safe from the dragons below, except for two that have foolishly landed on the dragon's tails.Bodleian Library, MS. Douce 151, Folio 71v https://www.pinterest.com/pin/80501912073109401

1 note

·

View note

Photo

AN INCOMPLETE HISTORY OF MEDIEVAL ART L MEDIEVAL NATURE III: EXCURSUS - THE UNNATURAL The medieval bestiaries, aviaries, herbals, and lapidaria purport to offer a comprehensive explication of the natural world. In general, the texts, the majority of which are are paraphrases of Pliny the Elder’s Historia naturalis, do not waste time rehearsing basic, readily-observable facts about ordinary animals and plants. Instead, the extraordinary and esoteric aspects of a given subject are highlighted and the actions most amenable to allegorical interpretation summarized. Inscribed in the “strange but true” natural world is its Other, the Unnatural. Descriptions of mythological, legendary and imaginary flora and fauna such as the baleful manticore and leucrota, the deadly siren and the hapless unicorn are evenly interspersed among those of the real animals and presented with the same solemnity of tone. Copying passages from Isidore of Seville about weird animals and unlikely plants posed no problems for the scribes of the bestiary. The inclusion of the unnatural world, however, severely taxed the representational powers of its illuminators. With neither an iconographical tradition nor direct visual experience to fall back on, the professional artists assembled the details mentioned in the texts into quirky, highly-imaginative forms that are not always suave, but highly memorable. As for the readers of the bestiaries, they were scholars affiliated with monasteries, cathedral schools or universities. For this constituency, the book was an exegesis of the spiritual sense of the natural world, analogous to the figurative interpretation of scripture. Thus, the allegorical and moral dimensions were the work’s primarily source of interest. The bestiary was not a biology textbook or a handbook for identifying birds and flowers while gardening and the daily life and habits of mice and sheep were of little or no importance to urban theologians and intellectuals. Anachronistc expectations of a materialist, empirical approach to nature cause modern readers to valorize the literal and descriptive components of the book, while dismissing the allegories as irrelevant, tendentious impositions, a misreading that exactly inverts the book’s structure. Finally, there is no reason to assume that all medieval readers and viewers credulously accepted the accounts of the onocentaur and the peridexion tree as true or believed they would die if a wolf saw them first. Sceptical readings of aspects of the text were permissible, particularly those parts written by pagans. Doubts about the allegorical methodology, however, crossed the line of heresy. 1. Manticore 2. Siren and Centaur 3. Dragon 4. Leucrota 5. 6. Turtle 7. Woman Nursing Lion Cub 8. Griffin 9. Unicorn 10. Fish.

An Incomplete History of Medieval Art by C. G. Hughes is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://lostprofile.tumblr.com/copyright.

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Art for a specevo thing I gotta write up an actual description for tomorrow ;-; Based off the Peridexion Tree of medieval bestiaries, the Peridexion Fig is a fruiting tree similar to the one we know, albeit even stranger than your standard fig- featuring a very unusual symbiosis with local wildlife and unique properties.

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

Have you considered adding some magic plants as well? Either chimerical plants, like the Vegetable Lamb and Barnacle Goose Tree, or things like the Peridexion tree?

I’d like to, but they’re a lot harder to find books on. Most books on “magical plants” are new age stuff about how wolfsbane will cure your glaucoma or something.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

[Bandcamp] Peridexion Tree - Demo III https://t.co/KauYuwVNJL pic.twitter.com/wrwkVoN6wj

— Raw BM Music (@rawbm_bot) November 24, 2018

0 notes

Text

[Bandcamp] Peridexion Tree - Demo I https://t.co/8YTqrFZwcm pic.twitter.com/bJfYWPRf3M

— #death metal in BC (@dmtag_bot) August 4, 2018

0 notes