#Paris Through Pentax

Text

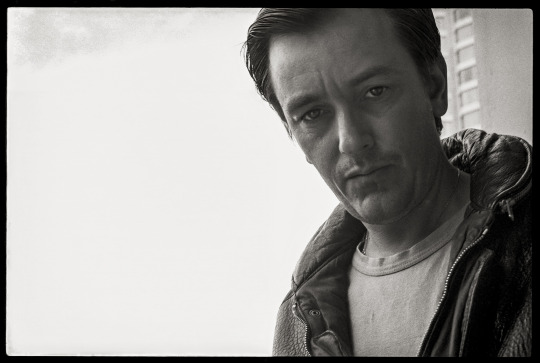

The 1986 film festival was the first I covered as both a writer and photographer, and was the beginning of a quarter century of regular portrait work every September in the rooms of whatever hotels were hosting the guests and publicity suites that year. It was so much easier in 1986, before the big movie PR professionals showed up en masse, and you could still book nearly every shoot and interview through the festival's own press office. Besides David Lynch - my big score that year - I photographed people like Dutch-born Australian director Paul Cox.

I was a fan of Cox after his films Lonely Hearts and Man of Flowers, and he was here promoting Cactus, starring Isabelle Huppert. I wish I'd known at the time that Cox had started his career as a photographer - Google was decades in the future - but it explains why he was so comfortable posing for my camera, despite my inexperience (I had only bought my Pentax barely a year and a half before). Cox was passionate and adamant - he had no patience for the big studios and the mainstream filmmaking that he considered the enemy of small, independent pictures like his. I remember leaving the interview chastened and inspired - practically a convert to his worldview. Cox would continue to make films for nearly three more decades, but this period probably marked the peak of his profile as a festival director. Paul Cox died in 2016.

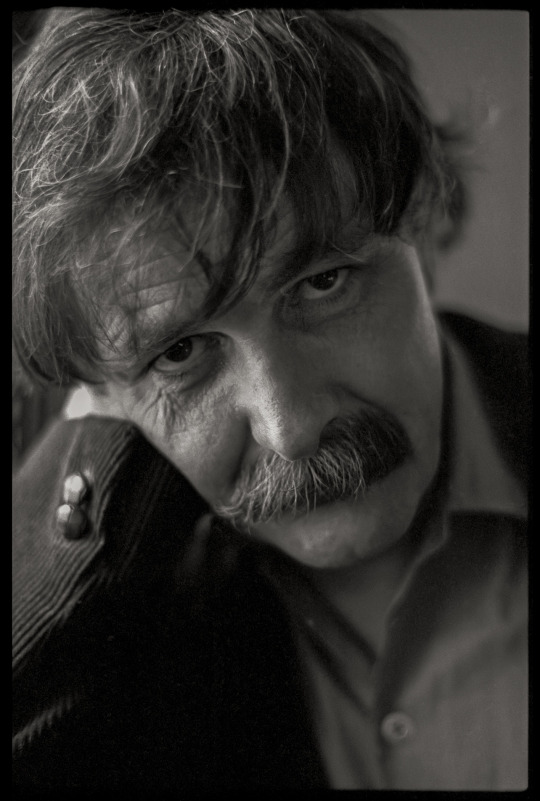

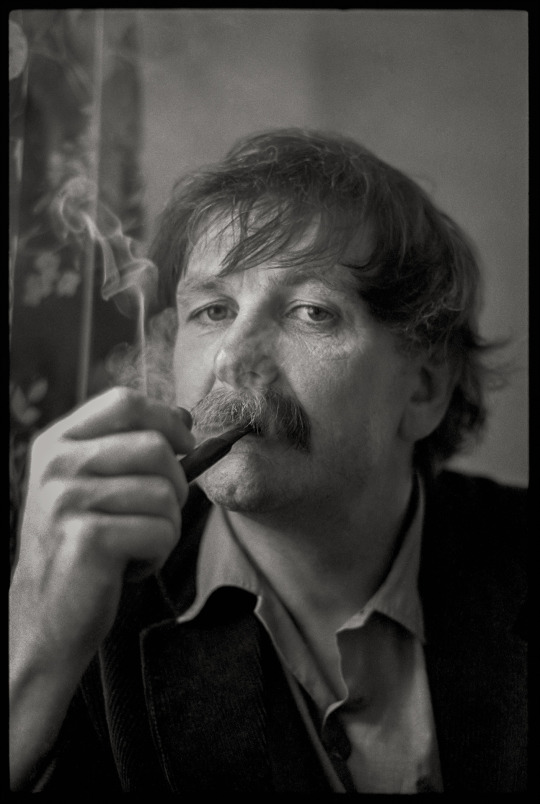

Another director I photographed at the 1986 film festival was Jean-Jacques Beineix, who I'd first heard about when his film Diva was a huge hit at the festival five years previous. He'd hit a rough patch with his next film, Moon in the Gutter, but made a comeback with Betty Blue, the film he brought to the Toronto festival that year. Films like Diva and Betty Blue, as well as directors like Beineix, Leos Carax and Luc Besson, were dubbed cinéma du look by French critics, and I remember how exciting they seemed at the time. It was, looking back, very much the sort of thing that would appeal to a young man - romantic and stylish and full of angst - and while I think Betty Blue is still worth seeing (though it would never be made today), I'm not sure that Diva has held up well.

Beineix had been through a lot in the last few years and I suppose it showed in these photos. I considered one of these frames unprintable back then, very far beyond my meagre darkroom skills, but I have managed to rescue it today thanks to superior scanning skills and the assistance of neural AI filters in Photoshop. The result looks like a still from an old nouvelle vague film, with Beineix in the role of Belmondo or Delon. Jean-Jacques Beineix died of leukaemia in Paris in 2022.

Horton Foote and his daughter Hallie were at the 1986 film festival promoting On Valentine's Day, the second film in a trilogy of pictures based on his plays set in the Texas of Foote's childhood, which starred his daughter in a role based on Foote's mother. Today everyone probably knows Foote for his Oscar-winning screenplay for To Kill a Mockingbird. He reccommended Robert Duvall for the role of Boo Radley in the film, and years later Duvall would play the lead role in Tender Mercies, which would get Foote another Oscar nomination and win Duvall one for Best Actor.

Foote also wrote scripts for pictures like Baby the Rain Must Fall, Of Mice and Men and The Trip to Bountiful - the latter based on his own 1953 teleplay, which went on to Broadway. Foote was the cousin of historian Shelby Foote, who wrote the 3-volume history that was the basis for Ken Burns' documentary series The Civil War, for which Foote provided the voice of Jefferson Davis. I photographed Horton and Hallie Foote simply, in a chair by the window of a room in the Park Plaza (now the Park Hyatt) hotel; the similarity of the poses and lighting ended up underscoring the family resemblance. Hallie Foote still works, mostly in theatre; Horton Foote died in 2009.

(From top: Beineix, Cox, Horton & Hallie Foote)

#jean jacques beineix#paul cox#horton foote#hallie foote#portrait#portrait photography#toronto#photography#black and white#film photography#director#photographer#some old pictures i took#old work#toronto international film festival#1986

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

You've Got to Look for the Good Stuff: Week 14, Spain

Like light is to darkness, this week has been an antidote to the last. My mood has lifted and the days have flown by, as lockdown continues and we do too.

Sunshine is a simple remedy. Each day this week has been warm and dry, if not bright and sunny too. It’s allowed us to live more inside-outside, which not only makes life easier but lifts my mood. It’s been a stark contrast to the constant rain and cold which dominated last week’s blog post.

I’ve also loved seeing pictures of children out in the streets and parks again, as Spain slowly lifts its coronavirus measures. It’s almost incomprehensible to imagine what it must be like for all these youngsters, many of whom have been cooped up in city-centre apartments with their siblings and parents for weeks and weeks. Even with the generous garden we have here and our weekly walks to the supermarket I’ve been going borderline insane, so I shudder to think how isolation has affected kids and their mental health.

Gaba Podcast live streams continue to punctuate my week. Adam Martin, whose podcast I mentioned in Week 10’s post, shares breathwork and meditative practices that have really helped me ease my busy mind. One of the things Adam talked about this week was what we consider to be ‘exercise’, in light of zealous Brits moaning that people sitting in the park, standing still in public and seemingly staring into space are breaking government-imposed controls around exercise. Adam argues that we consider sport and movement in open space an essential part to looking after our physical health, whilst ignoring the ‘exercise’ or psychological nurturing that our mental health deserves.

While this pandemic takes lives, we need to keep in mind the impact that social distancing is having on our psyches.

I titled this week’s digital diary entry ‘You’ve Got To Look Out For The Good Stuff’ because I’ve realised that there’s plenty of good stuff around, but quite simply, you’ve got to look for it. That might sound pretty obvious, but in comparing this week to the last, I can see that the main thing that’s changed isn’t my situation, but more so my mindset. Admittedly, the sunshine has made a huge difference, but apart from that, we’re still stuck in lockdown in Spain in the same physical, geographical and financial situation that we were in last week.

What’s caused this shift in mindset? Honestly, I don’t know. I think life in lockdown is making us act in all kinds of strange ways, cycling through an emotional spectrum so extreme we’ve rarely experienced it before and yet now feels like the norm. Tears, laughter, smiles and frowns easily paint my face in a matter of hours. So maybe my mood this week has just been luck. But as my shifted mindset has worked its magic, somehow I’ve seen and experienced little nuggets of ‘good stuff’. I hope that some of you have seen and enjoyed those nuggets too, wherever you are.

After rain left the road to the supermarket blocked, we finally made it to the shops this week, when the water subsided.

Perhaps fearful of another rainfall, this time we piled the trolley high in the local Aldi and returned home to stock up the cupboards. A plentiful fridge has resulted in some more cooking adventures - this week including George’s new specialty, Spanish omelette, and a new fave of mine too, veggie paella.

We picked and podded the final batch of broad beans this week, and helped to dig up the patch where they were growing to make way for the vegetables of the coming season: tomatoes, courgettes, cucumbers and peppers. One of the inadvertent blessings of being ‘marooned’ here in Catalunya has been to see and enjoy the changing of the seasons, and my interest in food growing and land management increases with them. George and I have always said we’d like to live in Spain in a self-built tiny house with a bit of land, and somehow we’ve landed in a situation right now that’s not far off! In addition to the vegetables we can get from the garden, I’ve been buying fresh eggs from the neighbour (often still warm from the coop!) which is a real treat.

(images, left to right) ‘Why simple changes [like growing food] are really profound’ a lovely illustration I discovered from Brenna Quinlan, George prepping the soil for tomatoes, and my new favourite thing to cook, veggie paella.

Food isn’t the only ‘good stuff’ to be grateful for. Since I mentioned Simon Mair’s article in my post from Week 11, I’ve been researching ‘Ecological Economics’ and its potential to lead us towards more just and sustainable ways of living. That research finally came to a head this week, when I had the pleasure of interviewing not only Simon himself but also friend and futures thinker from Mumbai, Mansi Parikh.

Making a video about alternative economic futures which address some of the challenges posed by Covid-19 is turning out to be a bit of a challenge in itself!

The interviews with Simon and Mansi were utterly fascinating, and I was so grateful to be able to talk to two super knowledgeable folk, who like me, are passionate about the future and how we can make it better. They shared their time and their insights, and now I’m left with over 150 minutes of recorded zoom calls to make sense of!

I want to use these interviews to make a video which engages people who perhaps wouldn’t usually be interested in economics, without ‘watering down’ the message or intent of the film. It’s such a hard balance to strike, to create something which is at once accessible and engaging but also rich with ideas. As the week progresses, I’ll start editing the footage and hopefully the narrative of the video will reveal itself.

One of the best things about making a new video is the chance to do loads of research! There have been so many articles which have got my brain buzzing, from ‘no-growth’ economics to deliberative democracies, and I’ve also just started reading ‘Fully Automated Luxury Communism’ which is a manifesto for a post-Capitalist future. Even if this research doesn’t directly inform the video I’m working on, it serves to inspire me. I’ve actually found myself a few times this week almost overwhelmed by how much interesting media there is out there to consume, and often just resort to adding thing to my ‘read later’ list, or quoting my favourite gems on Twitter.

(images, left to right) Recording interviews with Mansi and Simon, and my latest reading project...

The realisation of a project we began in January, ‘Place Portraits: Episode 1’ was finally released this week.

George had the idea a while ago to create a video series exploring cities and places through analogue photography. Whilst it was a super simple idea, we thought these short, laid-back videos would contrast with some of the longer-format stuff or more informative films we’re hoping to upload on the Broaden YouTube channel.

Back at the start of our trip we shot on a roll of Kodak Portra 400 and Fujifilm C200, using the trusty Pentax that was once George’s dad’s camera. We’d had the photos back from the processing lab for a while, but have only just completed the edit and got the film online, which is such a nice feeling. We’ve had some lovely responses to the resulting four-minute video, and I’ve especially valued constructive feedback so we can start to think critically about what Episode 2 might look like.

youtube

(video) Place Portraits: Episode 1 - Paris

Since ‘The Hundred Miler’ hit 90K views this week (which in and of itself is pretty nuts), I knew I had to temper my expectations about how many views we’d get with Place Portraits. Even though it’s not far past 200 views, each and every one of those views counts and I’m chuffed to see it finally online. Watching Broaden’s audience slowly grow has also served as great motivation to submit The Hundred Miler into film festivals, a process which we started this week.

There’s probably plenty more good stuff which deserves to be celebrated, but the one which can’t go unmentioned is of course the company of others.

Embracing what has become a routine activity for many of us these days, I’ve spent some cheerful hours on phonecalls and videochats to others across the globe.

This week included a three-way call between Ireland, Australia and Spain with dear friends that George and I used to live with catching up on career plans, cats and newfound hobbies. I also enjoyed a game of movie charades (which involved some impressive commitment from some people!) and even attended an evening of ‘drag queen bingo’. These digital hangouts leave me asking ‘Would I be connecting with friends and family this much if the world wasn’t in a global pandemic?’ and I think the answer would be no.

(images) Just some of the beautiful humans that feed my soul.

I’m grateful that these human connections are now much more of a priority. In being restricted to a simpler and more isolated way of living, we’re certainly reassigning value to the things that matter. That’s something which I’ve found from making the economics video and learning about the idea of value, but also something I’ve felt in a visceral way when a phone call with my parents or a friend leaves me beaming.

There’s so much good stuff out there, you’ve just got to be open to it.

#hiacevan#digitalnomads#COVID19#coronavirus#lifeinlockdown#quarantinegratitude#goodstuff#BryonyandGeorge#Broaden#PlacePortraits

1 note

·

View note

Text

Human Beauty Is The Dignity Of Beings

La Croix L'Hebdo: Last September, the Visa pour l'image photojournalism festival awarded you an Honorary Visa d'Or for Your Lifetime Achievement and the Praemium Imperiale Prize, awarded by the Imperial Family of Japan , has just been assigned to you. What do these rewards mean to you? Sebastião Salgado: It’s a mark of recognition for my work that touches me. The Visa d'Or was a real surprise, the secret had been well kept, I had gone to Perpignan to see exhibitions and attend the closing evening where a selection of images from Amazônia was to be screened. The Praemium Imperiale Prize has another connotation, I was born in Brazil and this country has a very special relationship with Japan: at the turn of the 20th century, hundreds of thousands of Japanese emigrated to Brazil to participate in the modernization of the country. On a more personal level, Lélia, my wife, and I taught for fifteen years at the Nippon Photography Institute in Tokyo, which reinforced our attachment to this country.

Do you remember your first photographic emotion? Se. S .: I remember it very well: we were in France for a short time, we were very young - Lélia was 22 years old, I was 25 - and we had to leave Brazil in the summer of 1969 because of our political commitments against the military dictatorship. Lélia was enrolled in the Faculty of Architecture and, for her studies, she very quickly needed to photograph buildings. In the spring of 1970, some friends lent us a house in Haute-Savoie, and we took the opportunity to go to Geneva to buy a camera. She chose a Pentax with a 50mm lens. Back home, we started to test it, and the first photograph I took was a picture of Lélia, sitting at the window. I still have it. I had never touched a device before and found it fantastic to be able to image anything that I found beautiful or interesting into an image: it was like a little miracle.

This is how the photo entered my life, never to come out. What training did you take? Se. S .: I did not follow any theoretical training, I learned in the field and especially in my laboratory: I developed all my films myself and I learned to exhibit my films according to the result I wanted. in the print, which I made for a long time alone. I have worked a lot in Africa. I realized that the films were designed for fair skin and the light of the rich countries, that beautiful and soft light of the North. They were neither suited to the harsh light of the tropics nor to black skin whose grain they did not give back. By dint of trial and error in my laboratory, I changed the way I exposed my films, changed the chemical formula of the developer, I freed myself from the instructions for use. With this empirical self-study, I surely lost time, but I also gained a lot of freedom, probably more than if I had left a school.

What advice would you give to a young photographer today? Se. S .: I can only give advice for the kind of photography that interests me: reportage, human, environmental, social photography. I would advise him to go to a university to train in social sciences: to do a little history, geography, geopolitics, anthropology, sociology. He must be able to understand the society in which he is a part and which is the object of his work, so that he can fully insert himself into the historical moment he is living through. Controlling the light, being the best cameraman is not enough, you have to understand the history in motion, with past and future issues in perspective. You work in black and white, why this choice? Se. S .: My very first photos in Savoie were color slides, it was when I returned to the Cité internationale universitaire de Paris, where we lived, that I discovered black and white thanks to a Brazilian friend, who told me. initiated the draw.

As soon as I was able, I set up a small lab in our home and, to finance my photography - our budget was very tight at the time - I started making black and white prints for residents of the city. Back in the day, working in color was much more expensive and more complicated to develop and print your work yourself. Another big drawback in my eyes is that with color the narrative sequence is cut off: the slides are independent of each other, once they are laid out on the light table you only keep the best ones. , the others disappear and the sequence is broken. With the contact sheet, photos and films follow one another and the narrative thread is preserved, you follow the course of time, even through the years: with black and white, the story is told.

0 notes

Text

Global Bronchoscopes Current and Future Market Size (2016-2023) | COVID-19 Impact Analysis

According to MRFR Analysis – Bronchoscopes Market is growing at a CAGR of 7.4% during the forecast period 2017 To 2023. The Global market industry segmented into by type, application, end user, and Region.

Bronchoscopes Market Synopsis:

The rising demand for minimally invasive procedures to conduct bronchoscopy is expected to fuel demand for bronchoscopes in the years to come. Market Research Future (MRFR) has found out in its latest study that the global bronchoscopes market is expected to reach a valuation of USD 2,244.4 Mn by the end of the forecast period (2017-2023) striking a CAGR of 7.4%.

The rising burden of respiratory and airway diseases are likely to catalyze the growth of the bronchoscopes market over the next couple of years. In addition, the rising prevalence of lung cancer is another major factor anticipated to boost the revenue growth of the bronchoscopes market in the years to come. According to the American Cancer Society, lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer death, and 228,150 new cases are estimated to be registered in the U.S. in 2019. The statistical observation offered by the organization further suggested that the death toll due to lung cancer in the U.S. is expected to reach 142,670 mark by the end of 2019.

Get a FREE Sample (Including COVID19 Impact Analysis, Full TOC, Tables and Figures) of Bronchoscopes Market @ https://www.marketresearchfuture.com/sample_request/4483

Technological developments are projected to act as growth catalysts for the bronchoscopes market over the assessment period. In addition, factors such as increasing older population, rising healthcare expenditure, etc. are anticipated to catalyze the expansion of the market in the upcoming years. However, the high cost of the device remains an impediment to market growth.

Bronchoscopes Market Segmentation:

By type, the global bronchoscopes market has been bifurcated into rigid bronchoscopes and flexible bronchoscopes. The flexible bronchoscopes segment has been further sub-divided into fiber optic bronchoscopes and video bronchoscopes.

By application, the bronchoscopes market has been bifurcated into diagnosis and surgical procedure. The diagnosis segment has been sub-segmented into examination, bleeding lungs, chronic cough, patient’s airways, possibility of lung cancer, and obtain tissue specimen for biopsy. Furthermore, the surgical procedure segment has been sub-segmented into removal of a foreign object in the airway, lung abscess, laser resection of tumors, percutaneous tracheostomy, stent insertion, and tracheal intubation.

By end-user, the global bronchoscopes market has been segmented into hospitals & clinics, diagnostic centers, and others.

Bronchoscopes Market Regional Analysis:

By region, the global bronchoscopes market has been segmented into Americas, Europe, Asia Pacific, and the Middle East & Africa. Americas is expected to hold the most substantial share of the global market and maintain its prominence through the review period. The region has a huge patient population which is likely to have a positive influence on the growth trajectory of the market over the next few years. Europe is anticipated to retain its second position in the global marketplace over the review period expanding at a CAGR of 6.9%. Asia Pacific is projected to exhibit rapid development, whereas the Middle East & Africa is expected to grow at a limited pace over the next few years.

Bronchoscopes Market Competitive Dashboard:

The key players of the global bronchoscopes market profiled in this MRFR report are Boston Scientific Corporation (US), Ambu Inc. (US), Cogentix Medical (US), Guangzhou MeCan Medical Limited (China), Olympus Corporation (Japan), Fujifilm Holdings Corporation (Japan), Pentax Medicals (Japan), Schindler Endoskopie Technologie Gmbh (Germany), KARL STORZ GmbH & Co. KG (Germany), Schölly Fiberoptic Gmbh (Germany), Hangzhou EndoTop Medi-Tech Co., Ltd. (China), Vimex Sp. (Poland), and LocaMed (UK).

Obtain Premium Research Report Details, Considering the impact of COVID-19 @ https://www.marketresearchfuture.com/reports/bronchoscopes-market-4483

Bronchoscopes Market Industry News:

In February 2019, Paris-based Mauna Kea Technologies received 510(k) clearance from the U.S. Food & Drug Administration (FDA) for using Cellvizio AQ-Flex 19 Confocal Miniprobe through existing bronchoscopes and other equipment for the detection of lung cancer.

In January 2019, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted approval for Olympus‘ Spiration Valve System (SVS) which is a minimally invasive treatment for a progressive form of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), severe emphysema.

In June 2018, the Zephyr Endobronchial Valve (Zephyr Valve), a new device designed for the treatment of severe emphysema was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

About Market Research Future:

At Market Research Future (MRFR), we enable our customers to unravel the complexity of various industries through our Cooked Research Report (CRR), Half-Cooked Research Reports (HCRR), Raw Research Reports (3R), Continuous-Feed Research (CFR), and Market Research & Consulting Services.

MRFR team have supreme objective to provide the optimum quality market research and intelligence services to our clients. Our market research studies by Components, Application, Logistics and market players for global, regional, and country level market segments, enable our clients to see more, know more, and do more, which help to answer all their most important questions.

In order to stay updated with technology and work process of the industry, MRFR often plans & conducts meet with the industry experts and industrial visits for its research analyst members.

Contact:

Market Research Future

+1 646 845 9312

Email: [email protected]

NOTE: Our team of researchers are studying Covid-19 and its impact on various industry verticals and wherever required we will be considering covid-19 footprints for a better analysis of markets and industries. Cordially get in touch for more details.

#bronchoscopes market#bronchoscopes market size#respiratory diagnostic#bronchoscopes market share#bronchoscopes market CAGR#bronchoscopes market growth#Bronchoscopy

0 notes

Photo

Left In The Window

• American Photographer Mark Fisher •

Taking A Break

There’s The Nikon

Resting While The Pentax

Is Having Too Much Fun

Image Captured Occurred With Mixed Lighting Sources

Modified During Post Lab

In New York City

•

• Just Be Creative •

•

No Second Usage Without Permission

All Rights Reserved • Models,Actors, Actresses,Dancers,

Musicians Used In The Web Posts Are Professionals

and Require Fee For Any Publication or Usage.

All Have Management.

Removal Of The Image Or Blog May Violate U.S. Laws.

Photographer Mark Fisher™ Is

A Well Accomplished Published Photographer

In Beauty, Fashion, and Music Photography.

New York City

Based Image And Filmmaker

Has A Worldwide Following.

Is A Member Of The Press.

There Is Fan Page On Facebook.

http://www.facebook.com/AmericanPhotographerMarkFisher

∆

Commissions Accepted Through Contract

• New York • • Paris • • Milan • • London •

Private Client Request Accepted.

Website www.americanphotographernyc1.com

For More Info Contact

Management

New York, New York

Thank You

#American Photographer Mark Fisher#Photographer Mark Fisher#Mark Fisher Photo-Images#MARK FISHER NYC PHOTOGRAPHER#New York Photographer Mark Fisher#Mark Fisher New York Photographer#Mark Fisher Photography#Mark Fisher NYC1#Mark Fisher NYC#Mark Fisher#Mark Fisher Photographer#NYC Photographer Mark Fisher#google images#Mark Fisher Images#Mark Fisher Mark Fisher#Mark Fisher Photo#Creative NYC1#Creative Photographer Mark Fisher#Mark Fisher Creative Photographer#Mark Fisher Creative#American Creative photographer Mark Fisher#Mark Fisher American Creative Photographer#North American Photographer Mark Fisher#Great American Photographer Mark Fisher#Mark Fisher Manipulation Photography#Mark Fisher Legendary Photographer#Legendary Photographer Mark Fisher#first stamp multimedia

0 notes

Link

0 notes

Photo

New Post has been published on https://www.jg-house.com/2020/01/26/sardinella-gold-1/

Sardinella & Gold, 1

When a few minutes before 3:00pm, our driver, Joseph, who had said little since we left Dakar, drove us into Saint Louis, not far from the border with Mauritania, I felt my anxiety rise. The Fulani man, wearing a gold earring with a short-sleeved shirt and brown slacks, navigated his Peugeot across the bridge in silence.

The bridge, called Pont Faidherbe, in honor of a French civil servant in West Africa who almost became mayor of Saint Louis, appeared to be old, but it was not. It was roughly the same age as the Eiffel Tower in Paris, designed by Gustave Eiffel before he became famous.

I occupied the back seat of the vehicle, peering out the window to my right. Lomax, my younger brother, sat in the front seat next to the driver, scrolling through images in his Pentax 645.

The medium-format camera, fitted with a 90-millimeter lens, was big, and Lomax alternately complained about it and praised it, calling it “my baby.” He had taken only a few photos on the 165-mile trip.

“At what time did we leave Dakar this morning? 10:30?” Lomax asked. I nodded.

I kept my gaze on the landscape unfolding on the river below. On the opposite bank, I saw an assortment of buildings in washed out pastels.

The three of us moved into the heart of Saint Louis, located on an island, called N’Dar, in the middle of the Senegal River.

I knew the bridge, which was opened to the public in 1897, connected N’Dar Island to the older, more run-down parts of Saint Louis to the east where the disused railroad from Dakar came to a halt in a patch of weeds. What I knew came from information from tourist brochures, not from Senegalese people themselves or from direct experience. Lomax and I had been to Senegal once before a few years before.

Joseph, reaching the end of Pont Faidherbe, turned right into the French colonial town, moving through a series of narrow, dusty streets lined by old buildings. Finally, he turned right on Rue Blaise Diagne and brought the sedan to a halt in front of one of the buildings, a massive 4-story structure occupying half a city block on our left. Two signs, one running horizontally across the middle of the structure and the other hanging vertically from its northern edge, displayed the same words: Hotel La Residence. We had arrived at our destination.

Above us, against a brilliant blue sky, fat, billowing clouds extended upward as far as the eye could see. The sky, on that Thursday afternoon, was oppressive. I opened the back door of the Peugeot, and a man, who had been leaning against the side of the building, next to the entrance of the hotel, moved toward me. I stood in the dusty street. The black man, covered only by a ripped brown tank top and red short pants, spoke in French. Lomax, too, as he exited the vehicle, came face to face with a black man speaking French. Lomax said, “Bon jour, monsieur.”

A group of black men gathered around Lomax and me as we collected our luggage from the trunk of the car. We were surrounded. Lomax, especially, was nervous. Several of the men were 50 or 60 years old, but most were in their late teens to mid 20s. All of them spoke to us, almost casually, as if they were distracted, in a kind of French I had heard spoken before by other Africans in other places. Previously, I had lived in Europe, where I had met many French-speaking Africans, in Brussels and Paris but also in Rome. It was in Italy’s capital that I had an apartment on Via Ostiense across the street from Basilica San Paolo, the second largest Catholic Church in the world. It was there, too, I had a Congolese girlfriend who had been born in Kinshasa but who had grown up in Paris.

Joseph drove off in his car, and Lomax and I, carrying our luggage through the crowd, walked the short distance to the lobby of the hotel.

Boy in Embroidered Shirt and Pants

The Guide

Just inside the main door of the lobby, a man, a tall African with closely cropped hair wearing an Izod cotton pull-over shirt and pressed trousers, stepped forward and smiled. Behind us, on the other side of the door made of glass panels, I could see the group of men dispersing. In front of us, the tall man handed me a card. “I will be your guide,” he said. His English sounded more like French.

“My name is Ismael,” he added. He opened the door and stepped into the street.

A mixture of dark wood and soft lighting, the lobby had a floor set in a pattern of alternating black and white tile squares. On the walls, a series of photos referred back to the 19th century. To our right, four leather chairs lined the wall. Upon closer inspection, the paint on the walls was faded and, in places, peeling. The upholstery of the chairs was coming apart at the seams. The overall impression was one of decline.

“It’s quiet,” said a man behind the front desk, speaking softly in English. “We don’t have many tourists now.” The man, who was black and about 60 years old, wore a tan linen blazer with both of the buttons buttoned and looked tired. “People here are desperate for work,” he said, looking through the glass panels of the door into the street. “Now we also have people from elsewhere, Mali and Cameroon.” The man continued, “You’re the Americans?” He handed us the key to our room. “Most of our visitors are Europeans, especially French.”

“By the way, Ismael has a special arrangement with the hotel,” the man added. “If you want, he will show you around Saint Louis for a small fee.”

Lomax and I walked through an open doorway at the end of the lobby to a wide staircase, laid with ceramic tiles. At the heart of the hotel, open to the sky above, the stairs rose up sharply into the bright sunlight. The glare was blinding. At first, we were alone on the stairs, dragging our bags up the steep incline and paying special attention to our heavy cameras. An elderly couple—a short silver-haired white man and a grey-haired woman—who were speaking French with Parisian accents appeared on the landing above us. Neither of the two spoke as they passed, but the woman smiled.

When we reached the 3rd floor, we turned left and found our room in one corner of the building. However, after inserting the key in the lock, we discovered it wouldn’t open the door. Next to the lock, the wood was scarred and slightly loose, as if someone recently had attempted to force the door. Suddenly, the door swung open.

Our room, with a view of the dusty street, Rue Blaise Diagne, was non-descript and minimally furnished. Against one wall, a small, black television set protruded into the air. No remote control was visible. I didn’t attempt to turn on the TV. Neither did Lomax. Under the TV was a table with two narrow wooden chairs. To one side of the table, attached to the wall, was a small mirror. Against the opposite wall, two twin-sized beds, each covered by a thin, red blanket, extended into the center of the room.

“All right,” I said to myself, setting down my luggage on a chair next to the window overlooking the street.

“We need cash,” I said to Lomax. “Let’s find an ATM.” Lomax looked at me. He was, I could see, not yet ready to go back outside.

Young Father with Two Daughters

At the ATM

I was opening the door when two people, two women in their 30s, appeared, moving along the hotel corridor in the direction of the stairs. I saw one of them nod at me, but I was pre-occupied and looked back over my shoulder into our room.

The room, which was neither large nor small, had a black-and-white photograph of ten fishermen in a big wooden boat setting out on a fishing expedition on the Senegal River. On the east side of the room there was a tall window, providing a view of Rue Blaise Diagne. Next to the window stood Lomax, looking down into a street of shadows. It occurred to me that Lomax was studying the desperate men who had surrounded us when we stepped out of the Peugeot sedan earlier.

“Come on,” I said, pushing the door open.

Lomax picked up his Pentax and walked past me into the corridor, bathed by a brilliant but setting sun. I looked at the digital watch strapped to my wrist—it was almost 5:30—and stepped into the sunlight too. I closed the door and tested the lock, hoping no one would force it again and make off with our computers. Following Lomax down the stairs through the lobby and out into the dusty street, I realized conditions in Senegal were worse than I had expected. From the moment my brother and I arrived in Senegal, we had been surrounded by groups of people, primarily young men, on the streets.

On Rue Blaise Diagne, he and I walked south until we reached the end of the block. At the cross street Rue Mor Ndiaye—I checked a sign on the side of a building—we turned right, scanning both sides of the short block before us for a bank. We needed to find an ATM so that we could obtain cash in the local currency, the West African CFA franc, for daily expenses.

Above, a column of white clouds in bright colors extended into the brilliant sky. Behind, black figures followed closely. We turned left at another street, called Rue Khalifa Ababacar Sy. A bank, named Compagnie Bancaire de l’Afrique Occidentale, came into a view on the west side of the street.

As Lomax and I moved toward the bank, one of the men behind us, in his mid 20s, came up to Lomax, speaking softly in French, but Lomax ignored him. I realized, at that moment, upon approaching the bank’s ATM, it was right on the street.

Woman Cleaning Fish

“Not this one,” I said, gesturing with my head in a southerly direction. Lomax moved in that direction. The man retreated a few steps. Resuming our pace, Lomax and I, with the African men not far behind, moved down Rue Khalifa Ababacar Sy toward the end of the block. We turned right on an equally narrow street, called Rue Blanchot. No cars had passed through any of the streets in the old town, but I realized that here and there cars were parked on both sides of the streets. A second bank, called Banque Internationale pour le Commerce et l’Industrie du Senegal, came into view. As we approached, I noticed its entrance was enclosed by a set of heavy steel doors.

“Here,” I said.

Behind the doors, Lomax and I found ourselves in an antechamber which contained an ATM. Alone inside the enclosed space, we were able to insert our debit cards, follow a set of instructions in English, obtain a small stack of bills, and retrieve our cards. Both of us relaxed, counting the francs and securing the money in pouches we wore tied around our necks. Previously, in Dakar, where we had stayed for two days, neither of us had been able to complete an ATM withdrawal.

In the sky, the mass of white, billowing clouds floated over the old town in the fading light. A cool breeze pushed away the warm air.

I stood on the sidewalk in front of Banque Internationale pour le Commerce et l’Industrie du Senegal, looking at my watch. It was almost 6:00. Lomax stood silently beside me, adjusting the strap of the camera on his shoulder. I stepped off the sidewalk into the narrow street, and we started to re-trace our steps through the old town toward our hotel.

Behind us, the same crowd of young men followed. One individual, appearing suddenly at my side, looked different from the others. With hair cut close to the scalp and wearing a clean polo shirt, he was not in the same class as the others. A gold ring on a finger and a gold bracelet caught my attention. Then, I realized the man was Ismael, the African guide, who had introduced himself in the lobby of Hôtel de La Résidence. “What do you want to see?” he asked, smiling. “You like photos? I take you to many good places along the river.”

I stared at Ismael, regarding him in a different light now that we were walking in the street at sunset, not standing in the hotel. Ismael was about my age, 42, and 6 feet in height, but he seemed thinner than I remembered. Also, he looked uncertain in the presence of the men standing nearby.

I noticed, at that moment, Lomax had raised his camera. To one side of the narrow street, I saw four teen-age boys playing marbles in the dirt. Three younger boys, skinny with bare feet, and one tiny girl with pig-tails had gathered around the older boys. Lomax steadied his camera and took several pictures. I waited, hoping he wouldn’t continue obsessively, taking additional photos, changing the settings on his camera again and again.

Just minutes later, though, Lomax and I were on Rue Blaise Diagne. We had covered the half block to Hôtel de La Résidence quickly. We stepped onto the concrete sidewalk at the front door. I was astonished that we had made it. Most of all, I couldn’t believe we had gotten our money without a mishap.

Ismael, once again, appeared. “I’m always available,” he reminded us, and melted back into the crowd. Lomax and I entered the building, passed through the lobby, and ascended to the 3rd floor, where I inserted the key into the lock on our door and discovered it opened the door easily.

Rue Blaise Diagne

An hour later, preparing to go downstairs to the restaurant for dinner, I heard a knock on the door and opened it. Standing in the corridor was a 65-year-old man, who looked familiar, but, also, angry.

“Do you have hot water in your room?” he asked in a French accent.

“Well, yes,” I said, “we do.” I paused, studying the elderly man. “I just finished taking a shower.”

“My wife is upset,” he stated. “We told the hotel staff an hour ago that we didn’t have hot water. Ten minutes ago, the manager told us the problem had been solved.” The man paused, staring. “But we still don’t have hot water.” With a determined, semi-angry look on his face, he continued to stand in the doorway. Then, he put his head down and walked to the stairs. I watched him retreat, thinking he was going down to the restaurant and realizing I was hungry and wanted to go downstairs too.

“Let’s eat dinner,” I shouted back into the room at Lomax, opening the door wider. Lomax stood by his bed. My gaze shifted to the opposite side of the hotel corridor, where a door of a room opened and, there, emerging, were the two young women I had seen earlier.

“Bon soir,” I uttered without thinking.

Woman Wearing Blue Scarf

François

Entering the restaurant on the ground floor of the hotel, Lomax and I saw not only an interior dining room but also, through a set of floor-to-ceiling glass panels which closed off a courtyard open to the sky, a collection of tables and chairs creating an outdoor dining room.

Seated at one of the tables in the outdoor courtyard, the two 30-year-old women were drinking white wine. At an adjoining table, a 65-year-old, silver-haired man and his wife were bent over their plates. The thought crossed my mind that the older couple was dining without taking a shower. I knew the elderly man and his wife felt uncomfortable. Probably they were both still upset. It had been a hot day.

Lomax and I walked to the center of the interior dining room, where a man sat at a table set for four persons. Before him on the table was a plate of fish, rice, and some vegetables. Near the middle of the table, within arm’s reach, sat a bottle of Flag beer, and a half-full glass of alcohol. The man, who was Caucasian, took a bite of fish as a waiter ushered Lomax and me to the table next to his. “Hello,” the man said, looking up.

“It’s pretty quiet in the hotel,” Lomax said, staring at the man. “Not many guests.” Then, to the waiter, Lomax said, “Two Flag beers.” Lomax sat in a chair, directly facing the man, who wore thick-framed glasses and an expensive looking, long-sleeved purple shirt. I sat in a chair at our table opposite Lomax.

“There will be more of us arriving in the next couple of days,” the man with glasses said, looking through the floor-to-ceiling panels at the diners in the courtyard. “You’re here for the river-boat cruise, like the rest of us?”

I shifted my chair at a 90° angle to the table partially facing the man with glasses. “Yes,” I said. “But also for other things.”

“That makes at least eight of us,” the man said, raising his glass toward Lomax and me. “More members of the cruise will arrive tomorrow, I believe.” He paused. “My name is François,” he added, “from Montreal, Canada.”

“We’re from Southern California,” Lomax replied, studying the fingers on his left hand. After a moment, he looked up and, remembering what he had to do, introduced us to François.

The waiter returned, placing two bottles and glasses on the table. Lomax filled my glass, and I picked it up and drank half its contents, leaning back in my chair. Lomax contemplated the bottle of beer in front of him, looking at it as if he had decided he didn’t want it. Then, in one motion, he picked up the bottle and drained it.

Boy in Red Shirt and Short Pants

“I’ve been on the cruise up to Podor once before,” François said, studying Lomax. “But this time we’re taking a bus to Podor and catching a boat back down the river to Saint Louis.” Podor, a small town on the border with the neighboring country of Mauritania at the southern edge of the Sahara Desert, was about 125 miles northeast of Saint Louis. I drank the rest of my beer and looked up at the ceiling. A large fan turned slowly above my head.

Lomax said, “I thought we were taking the boat up to Podor.”

The waiter re-appeared and asked if we were ready to order. Lomax nodded. Then he glanced at François, “What’s he having? I’ll have the same.”

When the waiter turned to me, I requested a Zebu steak with pepper, flambéed in cognac, and a potato. “Put sour cream and butter on the potato,” I added. François was looking at me.

The waiter said, “Very good.”

“You can talk to Anna,” François said to Lomax. “She manages the river-boat office across the street. She’ll answer questions about the itinerary.”

Lomax was reading the label on the beer bottle still in his hand. “Why not?” Lomax said, suddenly, allowing the bottle to drop on the table. François studied Lomax again, attempting to make sense of his behavior.

Lomax removed the Pentax from his bag and placed the camera on the table. “When was the last time you were here?” he asked François.

“Two years ago,” François replied. “It was in the fall, though.” He stared at the food on his plate. “I’ve been coming to Senegal for 25 years. I’m an administrator at a private school in Montreal which has an exchange program with a school in Thies, a town not far from Dakar.” François took a sip of beer from his glass and cast a glance at Lomax. “I’ve never seen it like it is now,” he continued. “The economic devastation, I mean. The desperate people roaming the streets every day.”

François looked through the glass partition into the courtyard. I followed his gaze. The two women sitting at a table in the courtyard were looking back at us. One of them smiled and waved.

Girl with Lollipop

Madeline and Sylvie

“I need to get back to my hotel,” François announced. “It’s 30 minutes away on foot.” He stood up.

“You’re not staying here? At La Résidence?” Lomax asked.

The waiter appeared, placing one plate with fish in front of Lomax and a second plate with a steak and baked potato in front of me.

“No, I prefer another place in the old town,” François replied. “Maison d’Hotes au Fil du Fleuve at the southern end of the island.” He smiled. “Enjoy your dinner.” Then, as he walked away, he stopped and, looking at Lomax, said, “I’d be interested in seeing some of your work.”

“Work? Oh, you mean photography,” Lomax replied and opened a pouch on the front of his camera bag and removed a business card. “Here,” he commented, reaching toward François. “My Internet address is printed on the front.”

After François departed, I finished the meal. When Lomax finished, he started to scroll through images on his large camera.

“Let’s go outside,” I said, looking through the glass partition into the courtyard and noticing the two women also had finished their dinner.

On the sidewalk in front of the hotel, moist air from both the Atlantic Ocean less than a mile to the west and the Senegal River two streets to the east settled over the night. The two women followed Lomax and me from the lobby. We stood looking across the narrow street at a dress shop and, next door, the office of the river-boat company. I followed their gaze, recalling the suggestion of François to visit the office the next day and remembering the name of the river boat, the Bou El Mogdad.

“I’m Madeline,” the shorter of the women said. “This is Sylvie.” Madeline nodded at her companion, a tall, black woman. “We’re from Paris.” Madeline, slender with curly dark hair, and Sylvie, more filled out, but slightly overweight, were unsteady on their feet. After drinking the two bottles of chablis which I had seen the waiter place on their table, they would be asleep soon. Madeline slurred her words when she mentioned their reservation on the Bou el Mogdad on Sunday. “I’m an MRI technician,” Madeline said. “Sylvie, an anesthesiologist at the same hospital with me outside Paris, in Combs-la-Ville.” Madeline spoke English with no accent, but Sylvie didn’t utter a word. Sylvie raised her right arm, and I noticed the gold bracelet which she wore on her wrist, reflecting the light shining from the hotel lobby.

“A nice piece,” I said, pointing to the bracelet. “I like the engravings on it. Where did you get it?”

“I bought it in Mali a week ago,” Sylvie commented. “In Djenne, about 600 kilometers up the Niger River from Bamako, the capital.” I’d been to Bamako the year before and wanted to go back. Sylvie showed me her other arm, saying, “I’ll go shopping tomorrow. I need another bracelet for my other arm, as you can see.” She laughed. “I love gold.” Then she spoke quickly in French to Madeline, while an image of Ismael and his gold rings came to me.

I wondered how soon Ismael would find Sylvie.

Sisters with Little Brother

Bertrand and Beatrice

At 9:00, on Friday morning, Lomax and I went downstairs and passed into the lobby on our way to the dining room. In the lobby, I noticed the silver-haired man and his wife, who were talking with the desk clerk and who glanced in our direction as we entered.

“My name is Bertrand,” the man said immediately. “I apologize for my behavior yesterday. I can’t believe I lost control.” Bertrand introduced his wife, Beatrice. “We’re from Montpellier, in southern France,” he said. He appeared to be in better spirits than he had been the previous day. “We live in Paris now,” Bertrand said. “My wife is a professor of economics at a small Catholic college near Notre Dame Cathedral, specializing in microfinance.” Beatrice smiled and extended her hand to me and then Lomax. Bertrand continued: “I was an executive at an insurance company, but I’m retired now. I’m a chef, not a professional one but a fanatical one who refuses to allow his wife in the kitchen or even to suggest what he should cook.” Beatrice started to laugh. Bertrand, though, looked uneasy, as if he feared what Beatrice might blurt out about him on impulse.

Bertrand peered at me and studied Lomax, who wore an oversized black baseball cap with an emblem of a raven on its front. “You’re the Americans,” he said, as if he had re-gained his confidence from the night before. But it occurred to me that everyone in the hotel—and, possibly, the town—already knew who Lomax and I were. Nevertheless, Lomax started to introduce us to the couple in an overly formal way, explaining that he worked as a software engineer for Motorola in Southern California and I worked in Washington, D.C., for a political research group. After Lomax finished, Bertrand and Beatrice excused themselves, saying they had an appointment with another chef, who was an old friend from Montpellier.

Lomax and I entered the courtyard. In the sky, I didn’t see a single cloud.

**

#Africa, #Travelogue #Africa, #Art, #Beauty, #Culture, #Environment

0 notes

Photo

Le bonheur d'Elza (2012)

Dir. Mariette Monpierre

Country: France

Language: French

Rating: 2/5

There is so much beauty working for the debut film Le bonheur d’Elza by Mariette Monpierre—the first female director from the island of Guadalupe. The cinematography captures a sumptuous tapestry of the island’s natural beauty. Bright, saturated colors dance across the screen creating a stark, but welcomed, contrast to the film’s opening Parisian backdrop. The first time actors are capable, beautiful, and have palpable chemistry. However, the many successful bits and pieces ultimately makeup a disjointed whole, which often treads the line into soapy melodrama territory.

We open on Elza (Stana Roumillac) who has freshly graduated with honors from a Parisian university—a feat which thrills her mother. That almost immediately flips when Elza announces she’ll leave her life in Paris. She’s headed to her childhood home on the Caribbean island of Guadeloupe in order to find the father who abandoned her. While she reconnects with her homeland through flashes of sun soaked joy we’re reminded of the french road films that preceded it. She also plays the part of a P.I., a rather awkward shift, and armed with a trust Pentax she discovers her father is a failing businessman who’s having an affair with a younger woman. She follows her father—Mr. Désiré (Vincent Bryd Le Sage), back to his sprawling mansion only to find his white wife, adult daughter, son-in-law, and granddaughter, Caroline (Eva Constant). The wife mistakes Elza as a nanny for little Caroline, an error which Elza doesn’t correct as she’s too afraid to reveal that she’s actually one of Désiré’s many illegitimate children. From there she integrates herself seamlessly into their lives, using this access to more closely observe her father and the life he left her for.

There is much throughout the film that is lobbed at the audience and never actually receives a satisfactory conclusion or exploration. The men of privilege in the film are predatory beings who pursue women for sex outside of their marriages. Some of this is consensual, some is sex work, and some is flat out assault. One such character, Désiré’s son-in-law, assaults Elza twice, but in the scenes between they share quips and a heartfelt chat. Elza never confronts him, no one ever discusses it despite their overwrought reactions in the moment, and the film spends no time questioning or meditating on these actions. In fact, the second assualt leads to the film’s climax where Caroline almost gets hit by a car and Mr. Désiré has a heart attack. The effect has almost camp-like soap operatic effect that that merely hangs there as something we witnessed, and the characters seemingly forgot they experienced, as it bears no true weight on the progression of the film.

Additionally, the film is definitely trying to explore a very layered and important conversation on race in post-colonial territories. We’re thrown crumbs of the perceived difference between “good” and “bad” hair or light and dark skin, which are obviously still very loaded concepts. The film opens on Elza’s beautiful curls, which she’s trying to get tamed and straightened into a tight bun for her graduation party. For the remainder of the film she lets her curls go natural, which draws a cold comment from her father once she finally confronts him: “With your kinky hair, you couldn’t be my daughter.” Mr. Désiré has a white wife though from the mistresses we’ve seen—they’ve all been black. He even keeps his daughter, Caroline’s mother, from her lover as he is a black man and not deemed good enough in Mr. Désiré’s eyes. It’s a heavy subject and we’re left with a series of questions, observations, and heartache over post-colonial identity in Guadalupe—this self hate—but it’s so drowned by subplots and camp we’re never given a satisfactory grasp on what the director’s potential answers and conclusions are.

Additionally, this racial divide is, for a moment, an issue separating Elza and her father as he cannot accept her due to her dark skin and kinky hair. However, after his heart attack she seeks him out at the hospital. Once he awakes they hold hands and it seems all has been forgiven. We fade into a scene of them dancing at his estate—him in a white suite, her in a black dress—in a rather obviously framed scene that feels out of left field. While heartwarming, the resolution was slipped in there to give the protagonist a happy ending and not because it was the natural evolution of character motivation. However, to even ruminate on post-colonial effects in Guadalupe, I’ll admit, was a refreshingly bold and unique theme to have included at all.

#movie review#movie recommendation#women directors#black directors#black women directors#blockbusther#blockbusthers#guadalupe#guadalupecinema#cinema#caribbeancinema#mariette monpierre#le bonheur d'elza#elza#frenchlanguagefilm

0 notes

Text

1983 Beirut barracks bombing, through the lens of a camera | Middle East

Early morning on Sunday, October 23, 1983, Pierre Sabbagh awoke from an uncomfortable night time’s sleep within the grounds of the US Battalion Touchdown Group (BLT) headquarters in Beirut, Lebanon.

The Lebanese photojournalist had slept in a foxhole on the BLT’s location of the American navy compound – residence to the US Marines from the Multinational Peacekeeping Power (MNF) – and all was quiet. In a metropolis that had rained bullets and bombs since Lebanon’s bloody civil conflict had erupted in 1975, Sabbagh gathered his belongings to discover exterior the camp.

“I used to be sleeping within the foxhole and it wasn’t actually nice,” recalled Sabbagh, then a 23-year-old shooter for United Press Worldwide (UPI). “And I noticed there was nothing notably occurring – so I made a decision to depart the US base within the very early morning.”

Because the marines slept soundly of their bunks – or started to awaken themselves from one other unpredictable night time within the restive Lebanese capital – the bottom at Beirut Worldwide Airport was shattered by a large blast.

A truck laden with explosives – later estimated to be the equal of 12,000 kilos of TNT – had rammed the BLT after crashing by way of the compound’s fortified perimeter. The guards on early morning responsibility stood no likelihood because the car’s driver detonated his cargo on the bottom ground of the headquarters. Of the boys stationed there, 241 US service personnel have been crushed to loss of life within the rubble. A second bombing on the French contingent killed 58 French peacekeepers. One other six Lebanese civilians have been additionally killed within the twin assault.

Two suicide bombers detonated truck bombs on the French and US barracks [Pierre Sabbagh/Al Jazeera]

The occasions of that day, 35 years in the past, stay recent within the thoughts of Sabbagh, who was the primary photojournalist on the scene of the bombing, which befell at 6:22am.

“Once I heard the blast on the street exterior the bottom, I instantly headed again,” remembers Sabbagh, now 58, who stated he had left the camp about 15-20 minutes earlier than the explosion. “That is how I used to be capable of be current inside earlier than they closed the entire web site to press and photographers.”

A then little-known Iranian-backed group calling itself Islamic Jihad claimed duty for the bombing because it did for the lethal truck bomb assault on the French navy barracks of the MNF the identical morning. Many studies contend that this group would ultimately develop into Hezbollah – the Lebanese Shia group backed by Iran and Syria. Decisive duty stays unclear to today, nonetheless.

‘Smoke and rubble’

Talking at size for the primary time of his expertise that day to Al Jazeera, Sabbagh stated that when he returned to the location the place he had been current minutes earlier, he was confronted with “plenty of smoke, mud, dust and rubble”.

“I rushed in and fell on the bottom … and was helped up by a guard, who introduced me into the secured perimeter in truth earlier than he acquired the orders to shut the world,” he stated.

The Beirut-born Sabbagh, who describes his re-admission into the flattened compound as “pure likelihood”, then started taking pictures for over two hours as US navy personnel struggled to get a grip of the grim scenario. He snapped his Pentax digicam nearly constantly – shifting from black-and-white movie to color and again once more. Little may have ready him for the horror wherein he now discovered himself as a younger skilled photographer, however he fell again on his expertise taking pictures the nation’s advanced civil conflict.

For a person who took up pictures as a interest at 16, and who went on to drop a resort administration diploma so as to concentrate on his photojournalist profession, the occasions of October 23, 1983, offered an project he couldn’t have foreseen. Certainly, the bombing had taken unconventional warfare to new heights; the FBI later stated the explosion was the most important typical blast they’d ever investigated.

The US itself had arrived in Beirut in August 1982. They have been a part of the peacekeeping pressure that additionally included a French, Italian and British navy contingent that was largely unsuccessful in maintaining the opponents from decimating components of town. By the point of the bombing, violence between the varied Muslim and Christian factions had been raging for eight lengthy years.

Nevertheless, the US’ alliance with Israel prompted Lebanon’s Muslim inhabitants to view US President Ronald Reagan’s White Home as endorsers of a Christian-led Lebanese authorities pursuing US-Israeli pursuits. In September 1983, and following the suicide bombing on the US embassy in April, American involvement turned deeper nonetheless when US warships, supporting Lebanese military operations, shelled Muslim positions within the Shouf Mountains.

The assaults ultimately performed a big function within the pullout of the peacekeeping pressure from Lebanon [Pierre Sabbagh/Al Jazeera]

The end result of those occasions was a bombing that put Sabbagh entrance and centre of a global incident. He was lastly faraway from the blast web site by US navy when his cordoned-off photographic competitors drew consideration to his privileged place contained in the destroyed stays of the navy compound. He was, he defined, requested to surrender his digicam rolls – however after consulting together with his boss, “determined to submit empty movies”.

His iconic photographs of that grim day have been revealed internationally, not least in French-language information journal, Paris Match.

He remembers the pictures portraying the “expressions within the eyes” of the surviving US Marines – one thing he stated he could not fairly recognize trying “by way of the viewfinder”. Delicate-spoken and considerate, Sabbagh would not totally elaborate on the “emotions” he felt days after the bombing – however on the finish of 1984, he give up the photojournalism enterprise. He was nearly to get married and the kidnappings in Beirut made him re-think his profession.

US pullout

The People, for his or her half, pulled out of Lebanon 4 after the bombing, in February 1984. Maurice Jr Labelle, assistant professor of historical past on the College of Saskatchewan, instructed Al Jazeera that originally after the bombing Reagan refused to again down, as an alternative declaring an early model of the conflict in opposition to “terrorism” and that US forces would keep till a “lasting peace” was cast.

“A long-lasting peace, ultimately, didn’t engender a US retreat; quite, withdrawal was pushed by an accumulation of political assassinations, which focused many People, together with American College of Beirut (AUB) president Malcolm Kerr, and [the] ensuing home congressional protests,” Labelle stated.

“Reagan’s so-called ‘peace mission’ in Lebanon was an utter failure. The truth is, Reagan’s so-called ‘peace initiative’ and open assist for the Israeli occupation and [Israel’s] Lebanese allies set ‘peace’ and the normalisation again,” Labelle added.

Born in Beirut, Sabbagh was the primary photojournalist on the scene of the bombing [Nabil Ismail/ Al Jazeera]

Immediately, Sabbagh, a married father-of-two, and a twin Lebanese-French citizen, manages a photographic distribution firm in Beirut that offers in Nikon cameras. Although he nonetheless indulges his ardour for pictures in his spare time, he says he deflects frequent requests to showcase his physique of labor, by way of the likes of an exhibition, from that bloody day in October 1983.

“It is a closed story for me,” he stated.

!function(f,b,e,v,n,t,s)(window, document,'script','//connect.facebook.net/en_US/fbevents.js');

fbq('init', '968100353246427'); fbq('track', 'PageView');

from SpicyNBAChili.com http://spicymoviechili.spicynbachili.com/1983-beirut-barracks-bombing-through-the-lens-of-a-camera-middle-east/

0 notes

Video

Paris Through Pentax from Maison Carnot on Vimeo.

Discover the city of love through a legendary camera, the Pentax 67.

maisoncarnot.com

Music : A.taylor - A late night's wandering

Thanks to Gaetan Morant (Absolt Agency) for the typography.

0 notes

Video

Paris Through Pentax from Maison Carnot on Vimeo.

Discover the city of love through a legendary camera, the Pentax 67.

maisoncarnot.com

Music : A.taylor - A late night's wandering

Thanks to Gaetan Morant (Absolt Agency) for the typography.

0 notes

Video

Paris Through Pentax from Maison Carnot on Vimeo.

Discover the city of love through a legendary camera, the Pentax 67.

maisoncarnot.com

Music : A.taylor - A late night's wandering

Thanks to Gaetan Morant (Absolt Agency) for the typography.

0 notes

Text

Helicopter Over New York • Photographer Mark Fisher • Caught In Flight

Helicopter Over New York Image © Mark Fisher NYC1 • Photographer Mark Fisher • Caught In Flight This One Was Filming Street To Street In The City The Color Of Craft Was Dark Blue A Simple To Capture In New York Just Be Creative™ No Second Usage Without Permission All Rights Reserved • Models,Actors, Actresses,Dancers, Musicians Used In The Web Posts Are Professionals and Require Fee For…

View On WordPress

#American Art#American Beauty Photographer Mark Fisher#American Fashion Photographer Mark Fisher#American Fashion Photographer Mark Fisher Wiki#American Music Photographer Mark Fisher#american photographer#American Photographer Mark Fisher#American Photography#Beauty Photographer Mark Fisher#Fashion Photographer Mark fisher#Fashion Photographer Mark Fisher Wiki#first stamp multimedia#Fisher Creative Wiki#Google#Google Images#Google Search#Mark Fisher#Mark Fisher American Beauty Photographer#Mark Fisher American Fashion Photographer#Mark Fisher American Photographer#Mark Fisher Beauty Photographer#Mark Fisher Creative#Mark Fisher Fashion Photographer#Mark Fisher Music Photographer#Mark Fisher New York Beauty Photographer#Mark Fisher New York Fashion Photographer#Mark Fisher New York Photographer#Mark Fisher NYC Beauty Photographer#Mark Fisher NYC Fashion Photographer#Mark Fisher NYC Photographer

0 notes

Video

Paris Through Pentax from Maison Carnot on Vimeo.

Discover the city of love through a legendary camera, the Pentax 67.

maisoncarnot.com

Music : A.taylor - A late night's wandering

Thanks to Gaetan Morant (Absolt Agency) for the typography.

0 notes

Video

Paris Through Pentax from Maison Carnot on Vimeo.

Discover the city of love through a legendary camera, the Pentax 67.

maisoncarnot.com

Music : A.taylor - A late night's wandering

Thanks to Gaetan Morant (Absolt Agency) for the typography.

0 notes

Photo

New Post has been published on https://www.jg-house.com/2019/07/30/black-white-blue/

Black, White, and Blue

When a few minutes before 3:00pm, our driver, Joseph, who had said little since we left Dakar, drove us into Saint Louis on the border with Mauritania, I felt my anxiety rise. The Fulani man, wearing a short-sleeved, button-down dress shirt and black slacks, navigated his Peugeot across the bridge in silence.

The bridge, called Pont Faidherbe, in honor of a French civil servant who almost became mayor of Saint Louis, appeared to be quite old, but it was not. It was roughly the same age as the Eiffel Tower in Paris, designed by Gustave Eiffel before he became famous.

I occupied the back seat of the vehicle, peering out the window to my right. Lomax, my younger brother, sat in the front seat next to the driver, scrolling through images in the LCD of his Pentax 645.

The medium-format camera, fitted with a 90-millimeter lens, was big, and Lomax alternately complained about it and praised it, calling it “my baby.” He had taken only a few photos on the 165-mile trip.

“At what time did we leave Dakar this morning?” Lomax asked. He turned to look at me over his shoulder.

“10:30,” I replied.

Girl, Old Town, Saint Louis, Senegal

Crossing

I kept my gaze on the landscape unfolding on the river below. On the opposite bank, I saw an assortment of buildings in reds, blues, and yellows, all of them in mildly washed out pastels.

The three of us moved into the heart of Saint Louis, known as the old town, located on an island, called N’Dar, in the middle of the Senegal River.

I knew the bridge, which was opened to the public in 1897, connected N’Dar Island to the older, more run-down, parts of Saint Louis to the east where the railroad from Dakar came to a halt in a patch of weeds.

What I knew came from information from tourist brochures, not from any Senegalese people themselves or direct experience. Neither Lomax nor I had ever been to Senegal, or any other country in Africa.

Joseph, reaching the end of Pont Faidherbe, turned right into the French colonial town, moving through a series of narrow, dusty streets lined by old buildings. Finally, he turned right on Rue Blaise Diagne and brought the sedan to a halt in front of one of the buildings, a massive 4-story structure occupying half a city block on our left-hand side.

Two signs, one running horizontally across the middle of the structure and the other hanging vertically from the structure’s northern edge, displayed the same words: Hotel La Residence, 159 Rue Blaise Diagne. Above us, against a brilliant blue sky, fat, billowing clouds extended upward as far as the eye could see. The sky, on that Thursday afternoon in a strange land, was oppressive.

Teen-Age Girl, Old Town, Saint Louis, Senegal

Impact

I opened the back door of the Peugeot, and suddenly a man, who had been leaning against the side of the building, next to the entrance of the hotel, moved toward me. I stood in the dusty street.

The black man, covered only by a ripped brown tank top and red short pants, spoke to me in French. Lomax, too, as he exited the vehicle, came face to face with a black man speaking French. Lomax said, “Bon jour, monsieur,” mispronouncing the second word.

Soon a group of black men gathered around Lomax and me as we collected our luggage from the trunk of the car. We were surrounded, and Lomax, especially, seemed frightened.

Several of the men were 50 or 60 years old, but most were in their late teens to early 20s. All of them spoke to us, almost casually, as if they were distracted, in a kind of French I had heard spoken before by other Africans in other places. Previously, I had lived in Europe, where I had met many French-speaking Africans, in Brussels and Paris but also in Rome. It was in Italy’s capital that I had an apartment on Via Ostiense across the street from Basilica San Paolo, the second largest Catholic Church in the world. I also had a black Congolese girlfriend who spoke French.

Joseph drove off in his car, and Lomax and I, carrying our luggage through the crowd, walked the short distance into the lobby of the hotel.

Girl, Old Town, Saint Louis, Senegal

Survival

The lobby had a floor set in a pattern of alternating black and white tile squares, just inside the front door. Behind us, on the other side of the door made of glass panels, the group of men began dispersing.

The lobby was small, a mixture of dark wood and soft lighting, and of several photos referring back to the 19th century. Facing us, 10 feet away, was the front desk. To our right, several dilapidated leather chairs lined a wall.

The overall impression was one of decline. Paint on the walls was faded and, in places, peeling. A door to an interior room appeared to be dislodged from one of its hinges. The chairs along the wall, upon closer inspection, were varying shades of well-worn yellow and brown.

“It’s the slow season,” said a man, looking into our faces while speaking softly in English. “We don’t have many tourists now.”

The man, who was black and about 60 years old, stood behind the front desk. He wore a tan linen blazer with both of the buttons buttoned. He was bald and appeared tired, even depressed.

“People here are desperate for work,” said the man, looking through the glass panels of the front door into the street. “Now we also have people from other parts of Africa, mainly Mali and Cameroon. They’re desperate for a way to survive at this point.”

The man continued. “You’re the Americans?” He handed us the key to our room. “Most of our visitors are Europeans, especially French.”

The desk clerk disappeared into a back office, leaving us alone.

Boy, Old Town, Saint Louis, Senegal

Decision

Lomax and I walked through an open doorway at the end of the lobby to a wide staircase, laid with slick white tiles and tall railings for support. At the heart of the hotel, open to the sky above, the stairs rose up sharply into the bright sunlight and a blinding glare.

We were alone on the stairs dragging our bags up the steep incline and paying special attention to our heavy, expensive cameras and lenses.

When we reached the 3rd floor, we turned left down a corridor and found the room in one corner of the building. However, after inserting the key into the lock, we discovered that the key wouldn’t open the door. Next to the lock, the wood was scarred and slightly loose, as if someone had attempted to force open the door.

Then, suddenly, the door swung open.

Our room, with a view of the street, Rue Blaise Diagne, was non-descript and minimally furnished. Against one wall, a small, black television set protruded into the air. It was an ancient model. No remote control was visible. I didn’t attempt to turn on the TV. Neither did Lomax.

Under the TV was a table with two narrow chairs. Next to the table was a small mirror.

Against the opposite wall, two twin-sized beds, each covered by a thin, red blanket, extended into the center of the room.

“All right,” I said, setting down my luggage on a chair next to the window overlooking the street. “We need cash. Let’s go find an ATM.”

Lomax looked at me. He was, I could see, not yet ready to go back outside.

#Africa, #LifeCulture

0 notes