#Naval!Commander!John

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

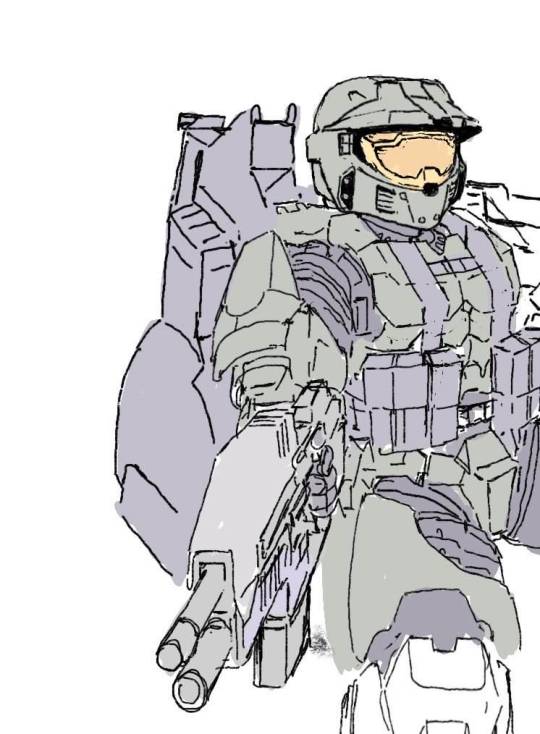

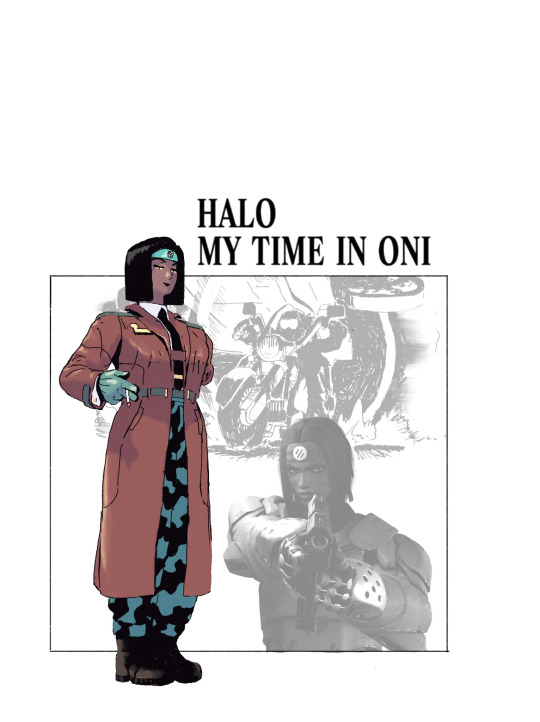

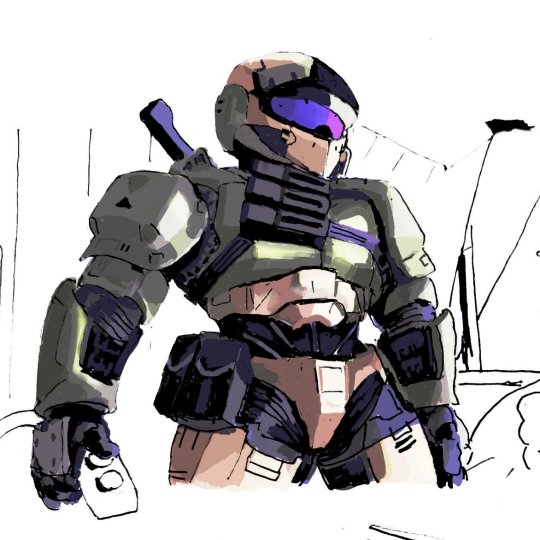

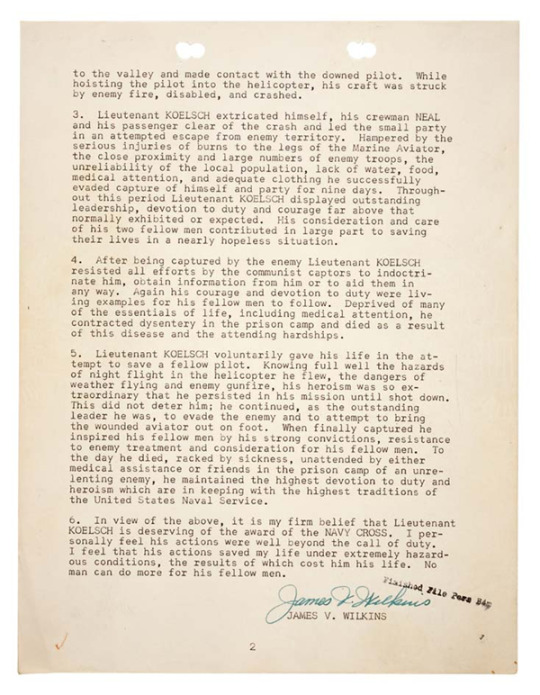

My Time In ONI [Webcomic]

Second Generation Spartans,

John 117, Vittoria 088 and Dani 109

#halo#halo webcomic#my time in oni#office of naval intelligence#master chief#john 117#halo fanart#halo art#united nations space command#oni section iv#toku city hunters#berserk forces#spartan ii#spartan

165 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mark Harmon & John Finn in NCIS S9.E8 Engaged part I (2011)

#navy cis#ncis: naval criminal investigative service#mark harmon#leroy jethro gibbs#john finn#marine commandant charles t. ellison

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Old naval slang

A small collection of terms from the 18th - early 20th century that were and probably still are known among sailors.

Admiralty Ham - Royal Navy canned fish Batten your hatch - shut up Beachcomber - a good-for-nothing Cape Horn Fever - feigned illness Cheeseparer - a cheat Claw off - to avoid an embarrassing question or argument Cockbilled - drunk Cumshaw - small craft - Chinese version of scrimshaw Dead Marine - empty liquor bottle Donkey's Breakfast - mattress filled with straw Dunnage - personal equipment of a sailor Flying Fish sailor - sailor stationed in Asian waters Galley yarn - rumour, story Hog yoke- sextant Holy Joe - ship's chaplain Irish hurricane- dead calm Irish pennant - frayed line or piece of clothing Jamaican discipline - unruly behaviour Knock galley west - to knock a person out Leatherneck - a marine Limey - a British sailor Liverpool pennant - a piece of string used to replace a lost button Loaded to the guards - drunk Old Man - captain of the ship One and only - the sailor's best girl On the beach - ashore without a berth Pale Ale - drinking water Quarterdeck voice - the voice of authority Railroad Pants - uniform trousers with braid on the outer leg seam Railway tracks - badge of a first lieutenant Round bottomed chest - sea bag Schooner on the rocks - roast beef and roast potatoes Show a leg - rise and shine Sling it over - pass it to me Slip his cable - die Sundowner - unreasonable tough officer Swallow the anchor - retire Sweat the glass - shake the hour glass to make the time on watch pass quickly - strictly forbidden ! Tops'l buster - strong gale Trim the dish - balance the ship so that it sails on an even keel Turnpike sailor - beggar ashore, a landlubber claiming to be an old sailor in distress Water bewitched - weak tea White rat - sailor who curries favor with the officers

Sailors' Language, by W. Clark Russell, 1883 Soldier and Sailor Words and Phrases. Edward Fraser and John Gibbons, 1925 Sea Slang, by Frank C. Bowen, 1929 Royal Navalese, by Commander John Irving, 1946 Sea Slang of the 20th century, by Wilfried Granville, 1949 The Sailor's Word Book, by Admiral W.H. Smyth, 1967

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

The thing about gay sailors in the Victorian era is that England and America had totally different takes on it. In the british navy they could, and did, literally kill men for having consensual relationships with other men. But in the US navy, even tho John Adams literally copied England's naval regulations when making America's version, he chose to leave out every proscription against sodomy. And no one knows why!!! England was like hmm yes the death penalty and America was like i dont really see how thats my business. And like gay American sailors could still be charged with things like "uncleanliness" or "indecency" (charges that were vague enough to cover a lot of different things) but bc it wasnt specifically forbidden in the regulations "the commanding officers [were given] wide discretion to prosecute, punish, or ignore."*

And by and large US officers seem to have ignored it. We literally have the records of every flogging (the most extreme form of punishment allowed during these specific years) onboard a naval vessel for the years of 1846-1848 and almost all of the cases that involved homosexual activity "unambiguously refer to male/male homosexual activity involving attempted assaults on children, not consensual couplings between adults."* There are also multiple recorded instances throughout the Victorian Era of an American sailor coming forward with a charge of sexual assault and pulling in other sailors or even officers as witnesses who tell their captain yeah i totally saw them and didn't say anything until this sailor told me it was nonconsensual. There are even records recorded by naval recruitment officers of men with extremely explicit gay tattoos being allowed to join the navy. Why did the US navy not care enough to even include it in the regulations while the British navy literally hanged men for it??? Were we so hard up for sailors that John Adams was like bitch we need every gay sailor we can get????

And weirdly enough this was true on American Whaling ships too! In the recorded cases where homosexual activity led to sailors being disciplined (in some cases punishment so mild as just being dropped off their ship at the next port) it was usually in situations where rape was involved and/or there was a high degree of ship disruption related to it (guys getting into a public knife fight for example). Idk I just think thats so interesting especially when America and England were so similar to be so different in this particular area is fascinating

*quotes from Unruly Desires: American Sailors and Homosexualities in the Age of Sail by William Benemann

#why did john adams think sodomy in the navy was a-okay???? did he not think americans capable of sodomy? did he have gay sailor friends????#us history#queer history#naval history#the terror#william benemann

93 notes

·

View notes

Note

Greetings,

I am a little obsessed with your Rossier pirate AU now. I was wondering whether you'd be willing to share the long version of it (the short version in the tags was already excellent)!

All the best

Ps. Because I sometimes think I am funny:

John Ross, having the Admiralty on speed dial: Why is my nephew fraternizing with this Irish guy??

William Edward Parry (their captain, basically), covering for them: Lol, idk what you mean, man.

Sorry this has been sitting here for a while because I didn't exactly know what to write so my pookie @vykerr helped me :))) and I also wanted to draw something for it so here we go!

Yippee!!

After coming back from the Antarctic expedition, Crozier is wracked by jealousy that his beloved Ross is getting married, even though he knows they cannot be together. Unbeknownst to him, Ross is using the marriage as a cover to protect Crozier, as he knows what the admiralty would do if they found out the Irishman was also a sodomite.

When Crozier is passed over to command the expedition to find the northwest passage, he finally snaps. He takes a small crew, sneaks onto the Terror, and commandeers her, sailing south instead of north. In the southern hemisphere he grows his crew by visiting various ports and taking on other naval officers and seamen that have been left out to dry by the admiralty. Then Crozier begins to engage in acts of piracy, though only against British naval vessels. He is somewhat of a master tactician, and the Terror being a warship also helps. The men on these crews who survive his raids and surrender are offered a choice between joining his crew or being dropped off at the nearest port.

The admiralty of course wants to send someone to apprehend Crozier and bring him to justice. Ross volunteers, wanting to make sure no harm comes to his beloved Francis, to try and bring him home safely and then he will try and protect him from the harsh hand of the admiralty. But Crozier knows Ross too well, and Ross won't risk killing him, and Crozier uses that to his advantage in their battles. Though of course, Crozier won't risk killing Ross either. He always manages to escape somehow, usually by disabling Ross' ship and then hightailing it out of there.

It gets to the point where despite Ross' insistence that he will eventually be able to capture Crozier, the admiralty no longer think he is capable of it. So they send in the Erebus, captained by Franklin with Fitzjames as his second. Franklin is cocksure that he will be able to take down the Terror with his superior vessel. However, his confidence turns out to be unfounded, as Crozier soundly thrashes him, his men boarding the Erebus and cutting down most of the men. Crozier indulges in killing Franklin himself, revenge for stealing his command. Some of the Erebites surrender, such as Fitzjames, who is taken captive by Crozier. In this case where these men attacked him, Crozier keeps them prisoner.

Crozier has also amassed a large enough crew now for two ships, so decides to take control of Terror's sister, spreading his crew out across the two ships mixed in with a few Erebites who are forced into working for him. The other crewmates teach them all about being pirates. But Crozier takes an instant liking to handsome Fitzjames, and decides to keep him as a personal prisoner in the great cabin.

phew! so many words! Everyone thank Vyker for helping me out because my ass cannot speak English this well!

#the pookies <3#pirate au#my art#ask#the terror#<3#james clark ross#francis crozier#james fitzjames#(mentioned)#rossier#jopzier#(mentioned also)#sorry if frank looks weird i still struggle to draw him#but augh i am insane about gay little sword fights sorry

59 notes

·

View notes

Text

Basil Lekapenos - a powerful eunuch and ruler of Byzantine empire. He was an illegitimate son of the Byzantine emperor Romanos I Lekapenos who served as the parakoimomenos and chief minister of the Byzantine Empire for most of the period 947–985, under emperors Constantine VII, Nikephoros II Phokas, John I Tzimiskes, and Basil II. His mother was a slave woman of "Scythian" (possibly implying Slavic/Bulgarians) origin. From his father's side, he had Macedonian and Armenian roots. Basil was a close friend of emperor John Tzimiskes. Basil himself took part in the great campaign against the Rus' in Bulgaria in 971, having been entrusted with the reserve forces, the baggage train and the supply arrangements, while Tzimiskes himself with his elite troops marched ahead. His enormous wealth enabled Basil to become, according to the Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium, "one of the most lavish Byzantine art patrons". "Psellos characterized him as the most remarkable person in the Roman empire, outstanding in intellect, bodily stature, and regal in appearance." As an artifice shaped by human hands, Basil Lekapenos became skilled in rhetoric, diplomacy, warfare; he possessed avid desire for wealth and power, subtle taste, and an eye for exquisite shapes. This eunuch's adorned body could be equated to the beautiful Limburg container. It is this brilliant form in which power resides. The eunuch is the angelic guard and protector; the face and body of the empire, in brief—the container of the empire. Relic and reliquary work in tandem, a pair suspended between presence and absence, between inaccessible energy—the emperor—and sensual experience of an iconized container—the eunuch."

— Res: Anthropology and Aesthetics, 51: Spring 2007. By Francesco Pellizzi

The history of Byzantium is dotted with examples of what some historians condemn as over-powerful eunuch courtiers, who attempted to dominate their rulers. From Chrysaphios in the fifth century, Euphratas under Justinian, to Staurakios and Aetios, Samonas in the ninth, Basil Lekapenos in the tenth, and John the orphanotrophos (in charge of the large Imperial Orphanage in Constantinople) in the eleventh, the list is extensive. Basil Lekapenos, an illegitimate son of Romanos I, known as ‘Nothos’ (‘the Bastard’), made a particularly successful career. After being castrated as a child to destroy any imperial ambitions he might have developed, he was appointed parakoimomenos by Constantine VII. He held on to great power through the rule of Nikephoros II and John I, and practically governed the empire during the first decade of Basil II’s reign (976–85). With his great wealth, he commissioned magnificent art objects such as the Limburg reliquary. He also wrote a treatise on naval battles and had it copied in a splendid manuscript of military Taktika.

In this respect, Basil Lekapenos was typical of several high-ranking eunuchs who became art patrons, diplomats, generals, administrators, teachers, writers, theologians and churchmen (plate 10). In many cases these officials were detached from their court duties to undertake particular missions, diplomatic or military, such as Andreas, who negotiated with the Arabs in the seventh century, or Theoktistos, who commanded the navy in the ninth century. In Byzantium, as in the caliphate, eunuchs regularly found employment as military generals and diplomats. Their high status is confirmed in the Book on the Interpretation of Dreams, written by a Christian Greek author, Achmet, who drew on Byzantine and Arabic sources as well as on his own dreams. In common with many authors, he equates beautiful eunuchs with angels. Both of course were considered sexless beings, since angels have no sex and eunuchs were supposed to have lost theirs.

As well as these high-ranking eunuch officials, others made careers far away from the Great Palace and imperial patronage. They appear incidentally in hagiographical sources, and sometimes feature on a list of wedding gifts, as in the story of Digenes Akrites, the frontier hero. When Digenes Akrites finally married the girl (she is never named), her eldest uncle presented them with ten boys:

Sexless and handsome with lovely long hair, Clothed in a Persian dress of silken cloth With fine and golden sleeves about their necks. — Byzantium: The Surprising Life of a Medieval Empire by Judith Herrin.

About eunuchs' appearance in Byzantium. As he [Andrew] sat on the ground in front of the gateway there came a young eunuch who was the chamberlain of one of the nobles. His face was like a rose, the skin of his body white as snow, he was well shaped, fair-haired, possessing an unusual softness, and smelling of musk from afar. [Another variant: beautiful young eunuch, with blond hair (epixanthos), a face like a rose and a body white like snow] -- Life of St Andrew the Fool.

Basil had a luxurious palace with 3000 servants, and he also built the most beautiful church of St. Basil, full of gold and decorations. It is said that when his nephew Basil Porphyrogenitus destroyed this church, Basil the eunuch fell from a stroke and was paralyzed, and later he died in the monastery.

Psellos records that In 985, the emperor Basil Porphyrogenitus assumed personal rule and banished Basil Lekapenos who soon after died "his limbs…paralysed and he a living corpse".

***

"In the course of Byzantium’s long history, a few individuals effectively ruled the empire without occupying the imperial throne. One of the most interesting of these figures was Basil the Nothos, or Basil the Parakoimomenos, who was the main power beside or behind the throne for most of the period from 945 to 985.

This he did until 985, when Basil II, no longer a teenager, could no longer bear his own exclusion from power. The vindictiveness with which he not only removed the Parakoimomenos from office, but also sought to destroy the latter’s political legacy, is a measure of how complete the elder Basil’s political control had been. It was a political control that both amassed and expended great wealth, both facilitating and relying on an extensive network of social and cultural patronage. The greatest beneficiary of this patronage, the monastery that Basil founded in the name of his patron saint, has disappeared almost without trace, but his sponsorship has been seen, or surmised, in numerous cultural artefacts of the later tenth century, and interest in his role as the last patron of the “Macedonian Renaissance” shows no signs of abating.

At the centre of the Parakoimomenos’ quasi-imperial power and patronage was his oikos, which was no doubt appropriate to his status. Indeed, his house and household are mentioned no less than four times in literature of the period. According to Leo the Deacon, Basil was able to mobilise and arm over three thousand “household members” (οἰκογενεῖς) in support of Nikephoros Phokas in 963. The same author later records that he had witnessed a bright star descending on the house of the proedros Basil; this portended Basil’s death shortly afterwards and the looting of his property

There is an additional reason for seeking the house of Basil the Parakoimomenos in the area of the Embolos of Domninos. This is because it was somewhere to the west of the Embolos that Basil established his monastery of St Basil, which was famously stripped of its wealth and its ornaments by Basil II."

-The House of Basil the Parakoimomenos, by Paul Magdalino

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

Exam results (Royal Naval College)

For this, I am not 100% sure if it is our John. Only because some dates don’t line up exactly: with Bell's book (1881) saying that John entered the naval college in Portsmouth on the 25th June 1828. If John graduated in 685 days as written below, then that would have made his enrolment date the 6th August 1828. However, I realise this excludes weekends, holidays, and perhaps some time to settle etc. So it’s a little messy to establish concrete confirmation with the given dates! But the timeframe is reliable, the high results — especially in maths — are consistent with what we know about his academic career (high midshipman’s scores and gained full numbers in maths!), the college title and location is consistent, and as far as I know there was not another John Irving who was the same age and in the same school. So it could simply be a date mix up due to the lack of detail.

Here’s my transcription regardless, because if it is him it’s so cool! And if solid information is found I will be sure to provide updates.

Source: RUSI/NM/243 Greenwich National Maritime Museum (& much appreciation to @cdr-edwardlittle for finding the entry 🫶!!)

"Royal Naval College, 22nd June 1830.

Mr. John Irving

Finished his Mathematical Education at the Royal Naval College in 685 days; being 45 days less than the Two Years; and made the following Progress,—730 being the full numbers.

[Days at College; or, Numbers expected in that Time], [Numbers gained], [Remarks = N/A for all].

- Mathematics = 685; 730

- English and Classics = 685; 690

- History and Geography = 685; 600

- French = 685; 600

- Drawing = 685; 630

Gained the following numbers at the Midshipmen‘s Examination.

[Value of full Answer a], [Value given a], [Remarks], [Value of full Answer b], [Value given b].

1. 10. 10 —- Geometry. 40. 35

2. 10. 10 Course & Distance. —-

3. 10. 10 Parallel Sailing. Arithmetic, & [S] —-

4. 10. 10 Current. —-

5. 30. 28 Days Work. Algebra. 50. 47 1/2

6. 10. 10 Time of *s on Merid: —-

7. 10. 10 O's Merid: Alt. Trigonometry. 50. 46

8. 10. 10 [symbol]‘s Merid: Alt. —-

9. 10. 10 *'s Merid: Alt. Astronomy. 50. 40 1/2

10. 10. 10 * under Pole. —-

11. 10. 10 Pole *. Navigation. 280. 278

12. 40. 40 Double Alt: —-

13. 30. 30 Chronometer. Instruments, —-

14. 40. 40 Lunar. —-

15. 10. 10 Amplitude. Mercator‘s Chart, —-

16. 20. 20 Azimuth —-

17. 10. 10 Tide. & Surveying. 40. 34 1/2

18-21. —- Gunnery & Fortification. 50. 35

Total = 280 / Total = 278

Total = 560 / Total = 516 1/2

Examined on the 22nd June 1830, and allowed Two Years Time of Service at Sea, being found Qualified to be Discharged into His Majesty‘s Navy.

Thomas Foley - Admiral and Commander in Chief.

[Michael Seymour?] - Commissioner.

Wentworth Loring - Lieut. Gov. Royal Naval College."

Context =

Source: Lieut. John Irving, R.N. of H.M.S. “Terror,” in Sir John Franklin’s Last Expedition to the Arctic Regions: A Memorial Sketch with Letters. Edited by Benjamin Bell, F.R.C.S.E. (1881): https://ia801404.us.archive.org/31/items/cihm_29830/cihm_29830.pdf

#john irving#the terror#franklin expedition#If I misunderstood anything feel free to correct me#unlike john i‘m bad with numbers

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

Back to the Dance Part Four: Naval Warfare

Thanks for reading so far! Here's the new master post if this is your first time encountering this series!

From the battles on land we now shift our focus to the war at sea; this is a topic I covered in the original series and in my Velaryon Blockade analysis, although I hope the quality of this analysis will be closer to the latter than the former. The Dance only features two theaters in which naval forces play any sort of role, the Narrow Sea and the Sunset Sea, so our focus will be on House Velaryon and the Ironborn. I'll scrutinize the the organization of their fleets and the ships they command based on how well they reflect the Medieval and Early Modern settings which inspired George. Scale is a significant problem here, but a lot of it comes down to the story having no perspective of what is achievable for these factions given the technology at their disposal.

Before analyzing the Velaryon and Ironborn fleets and their actions in the Dance, it's important that we understand how the term 'sea power' has been conceptualized in the past and whether such theories have any applicability to the setting. The Velaryon Blockade analysis was in many ways responsible for my deciding to re-analyze the Dance, as researching pre-modern naval warfare showed me that my frame of reference was completely wrong. I spent part 2 of the original series speculating about fleet sizes and critiquing the tactics of the one naval battle we get in the story, but this was a pointless exercise in retrospect. I threw out a basic definition of the term sea power without demonstrating what it entailed in terms of resources and strategy, or asking if a modern definition of sea power was even relevant to a Medieval/Early Modern context like Westeros. To remedy this error, I'll give a brief precis of the tenets of sea power and naval strategy as defined by Alfred Thayer Mahan (1840-1914), the great American naval theorist of the 19th and 20th centuries, based on John Hattendorf's essay "Theories of Naval Power: A. T. Mahan and the Naval History of Medieval and Renaissance Europe." This will allow us to better assess the capabilities of Westerosi fleets, and it also has some relevance to the subject of Part Five in this series, dragons.

i. Sea Power, Mahan-Style

To call Alfred Thayer Mahan influential would be a gross understatement: The Influence of Sea Power upon History and its successor about the wars of the French Revolution and Napoleon cast a long shadow over the 20th century, through the writing and study of military history and the conduct of war itself. Nonetheless, Mahan's critics, supporters, and commentators have added much baggage to the man's reputation since he first published in 1890, and Hattendorf does an able job of capturing the fundamental principles. For Mahan, sea power was based on a combination of maritime economic and naval factors, the former concerning elements like production, shipping, and colonies while the latter was concerned with protecting a maritime economy using armed force at sea via naval supremacy (Hattendorf, "Theories of Naval Power," 8). Mahan identified other factors which determined the capacity to develop sea power, namely geographical position, the extent of one's territories, population size, national culture, political structures, and physical conformation factors such as natural resources and climate (Ibid.).

As regards the maritime economic and naval factors of sea power, Westeros and in particular Driftmark and the Iron Islands 'make the cut;' except for colonies, pretty much every kingdom possesses ports with shipbuilding facilities and merchant ships that contribute to the economy, while only Dorne and the North lack any real military capabilities at sea. The capacity factors for sea power are more uncertain: National culture isn't really a factor in this setting, but the Velaryons and Ironborn are both seafaring peoples with a culture and long history tied to it; political structures are a mixed bag, but the existence of the Royal Fleet in King's Landing and other major fleets that predate the conquest show that naval forces were and are taken seriously by political powers; geographical position is ostensibly favourable, since the Seven Kingdoms have ample coastline and the size of Westeros alone incentivizes the movement of people and goods by sea, the main issue being that Mahan wrote about coastal powers whereas the Iron Islands and Driftmark are islands; this in turn makes extent of territory and population size a problem, since Driftmark and the Iron Islands have small landmasses and lack the large populations of mainland ports such as Oldtown, Lannisport, and Gulltown; while physical conformation is the greatest obstacle by far, since the Iron Islands are cold and wet climate-wise with few forests, although F&B refers to Driftmark as "fertile." While some of Driftmark and the Iron Island's worldbuilding is a problem, Westeros as a whole possesses the basic building blocks of sea power from a Mahanian perspective.

The exercise of Mahanian sea power via naval strategy is where the Velaryons and Ironborn in particular are on shakier ground. For Mahan, naval strategy was dependent on a number of factors, starting with locations of strategic value: the geographical location of a place in relation to lines of communication and trade at sea, it's defensibility and potential to support offensives, and it's resources for survival (Ibid., 10). Mahan added an interrelated fourth criteria called strategic lines, meaning the ability of ships to travel from one location to another either by using an open sea route (typically the shortest) or by following friendly or neutral coastlines if the open sea was not an option (Ibid., 10-11). From here, the other factors necessary to naval strategy were a reasonably secure home frontier and a navy that could dispute the enemy's control of the sea, permitting distant operations in enemy waters and maritime expeditions to land troops in enemy territory, with the overall goal of driving away or drawing out the enemy fleet through threat of battle to destroy it and gain control of the seas (Ibid., 10-12).

Looked at purely from a Mahanian perspective, the locations of Driftmark and the Iron Islands are conducive to naval strategy, between Driftmark's location between Crackclaw Point and Massey's Hook and the Iron Islands being situated off the northern coast of the Westerlands at the mouth of Ironman's Bay. There are other worldbuilding aspects of the Velaryons which don't really make sense from the perspective of Mahanian naval strategy: According to HOTD, the Velaryons or at least Corlys Velaryon are the wealthiest house in Westeros prior to the Dance; in reality, F&B makes clear that Corlys' ninth voyage to Qarth brought back such wealth in spices and silk that their profits "briefly" eclipsed the wealth of House Lannister and Hightower. Nonetheless, F&B still claims that Driftmark and Spicetown began to draw traffic away from Duskendale and King's Landing owing to their closer proximity to the Narrow Sea. This doesn't really add up given that Driftmark is an island, meaning cargos cannot reach markets on land directly as they can from Blackwater Bay's western ports. Regarding resources for survival, we're again told that Driftmark is "fertile" but not much else, while we at least know the Iron Islands have grazing for animals like goats and fisheries to support the islands. Driftmark's home frontier is clearly the more secure, being near to Dragonstone and thus the Targaryen dragons, whereas the Iron Islands only saving grace is that neither the Riverlands nor the North possesses much strength at sea, otherwise the Westerlands and Reach possess the resources and wealth to maintain large fleets such as those of Lannisport, Oldtown, and the Arbor.

This is as far as Mahan can get us in this setting, since the instruments of naval strategy he envisioned, that is fleets and their ships, are very different from those in our setting. Mahan's Influence of Sea Power series focused on the period of 1660 through 1815, and was intended along with his other writings to encourage the development of a powerful US Navy in the 1890s and 1900s. The multi-decked, heavily armed ship-of-the-line was the foremost instrument of sea control in the times he wrote about, while the heavily armoured battleship was its successor in his own day and remained the chief instrument of sea control until after the Second World War, contrary to the popular belief that the aircraft carrier supplanted it (Tim Benbow has two great articles on this subject, though I recommend James FitzSimonds' "Aircraft Carriers versus Battleships in War and Myth" for the Journal of Military History). The warships of the Medieval and pre-1660 Early Modern Periods differed greatly in their capabilities, and this is the period we must look to for assessing the Velaryon and Ironborn fleets. The organization and composition of these fleets and Westerosi fleets in general indicates that Mahanian naval strategy via sea control is not viable in this setting, owing in no small part to how George envisions his warships.

ii. No money, no problem?

The foremost issues with the fleets of Westeros is that of the armies: No one seems to be paid outside of sellsails and private merchants. When the Small Council discusses the High Septon's attempts at abolishing brothels in King's Landing in Cersei VIII of AFFC, Cersei argues that the taxes on brothels "help pay the wages of my gold cloaks and build galleys to defend our shores," implying that the coin spent on the fleet goes towards the vessels themselves and not those serving on them. Similarly, when Theon joins his father's cause in Theon I and II of ACOK, he is advised on how to "choose" his crew with no suggestion that they will be paid either by himself or his father. The idea that the same, vague 'feudal obligations' used to mobilize Westerosi armies can be applied to large fleets in unworkable: in my discussion on twitter with Bret Devereaux and X user SzablaObr2023 (screenshots are in the Velaryon Blockade post), Szabla observed that sailors are generally long-service professionals whose skills are in-demand. Paying them for any length of service is non-negotiable, and their wages must be competitive otherwise they'll become merchantmen, pirates, or mercenaries. Since all three are viable options in Westeros, the Seven Kingdoms and it's noble houses cannot operate their fleets without paying wages to their sailors, marines, and officers.

Building and maintaining warships would certainly be costly, but paying and provisioning the crews and replacing them if need be would add a whole other level of expenses. As an example, Edward III of England assembled 371 ships between July 1338 and May 1340 for his Low Countries campaign at the start of the Hundred Years War; his wardrobe books indicate that just over £382000 was spent on 291 ships to transport his army and its supplies and 80 support vessels (Bryce Lyon, "The infrastructure and purpose of an English medieval fleet in the first phase of the Hundred Years' War," 65-66). 12263 masters, constables, sailors, pages, clerks, and carpenters were remunerated to the tune of £4797 for ferrying 2720 earls, bannerets, knights, squires, men-at-arms, and hobelars, 5550 mounted and dismounted archers, over 500 members of the king and queen's household, and 4614 horses across the channel (Ibid., 66). Adjusted for inflation, it cost £465 million or $590.5 million USD to maintain a fleet which was gathered from across the kingdom, the bulk of the ships being privately held as only 14 were the king's ships (Ibid., 71).

The Ironborn are closer to historical precedent than the other Westerosi fleets, as it appears to be superficially derived from the 'leding' systems of Scandinavia. This system existed in varying forms in Sweden, Denmark, and Norway during the Early and High Middle Ages, requiring their populations to contribute towards maintaining and manning ships, either partially for those with lower incomes or fully for the wealthy. The Ironborn's aesthetic was clearly inspired by the 'vikings' and it makes sense that a similar system for providing longships and their crews would exist on the Iron Islands. However, as with the 'feudal obligations' for land forces we discussed in Part Three, the 'leding' was primarily a defensive organization intended to ward off foreign raiders and invasion; only Denmark appears to have allowed for expeditio or offensive military operations, and that could only be invoked once every four years per the 13th century Law of Skåne (Niels Lund, "Naval Power in the Viking Age and in High Medieval Denmark," 30). Beyond this allotted time period, Danish rulers were required to persuade their magnates and lords to provide forces for any foreign operations, just like their Swedish and Norwegian neighbours (Ibid., 31-32).

iii. You're rowing the wrong way!

When it comes to the ships of the Velaryon and Ironborn fleets, there are similarly glaring problems with the oared vessels or galleys in particular. While the Velaryons also operate sailing ships, I'll discuss those types in the context of the Ironborn since they have special relevance to their worldbuilding problems. We have pretty good information regarding the composition of the Velaryon fleet: When Alyn Velaryon sets out for the Stepstones in 133 AC, we're told the Velaryon fleet assembled '60 war galleys, 30 longships, and over 100 cogs and great cogs,' or over 190 ships. We know that the Gullet cost the Velaryon fleet almost a third of it's ships, and 7 ships were lost escorting the Gay Abandon, placing the fleet at c.254 ships at least in 129 AC, the actual number probably being between 260 and 300. As we've already seen, Edward III's fleet numbered 371 ships in 1340 drawn from across England, meaning the Velaryon fleet is at least 70% that size. For further comparison, per John E. Dotson's essay "Economics and Logistics of Galley Warfare," the wars between Venice and Genoa from 1250 to 1352 saw the latter city assemble over 150 ships for it's fleet in 1295 while the former assembled over 200 ships in 1293 (Dotson, "Economics and Logistics," 223). Those fleets were exceptional, with fleet sizes in other years ranging between just over 100 to just over 50 ships, subsidized wholly or in part by government funds (Ibid). For an island as small and lacking in natural resources as Driftmark, a fleet of over 250 ships is an almost impossibly large.

From the description we have of the Battle of the Gullet, it appears that the galleys of the Velaryon fleet had the worst of the fighting, meaning its composition at the start of the Dance was probably 50/50 oared to pure sailing vessels, if not more on the side of oars. When it comes to portraying galleys in the series, George is hampered by two major misconceptions: how oarsmen are placed on the ships and how many oars are used; and the role of ramming in naval warfare. George uses the number of oars, number of decks, and number of 'banks' in a way that seems to imitate the number of decks and guns used to classify sailing warships in the Age of Sail. Thus in the prologue of ACOK, Lord Stannis's Fury is described as a 'triple-decked' war galley of 300 oars; Sam refers to the Honor of Oldtown as "Lord Hightower's four-decked banner ship" in Sam V of AFFC; Arya describes the Wind Witch as a "sleek three-banked trading galley" in Arya V of AGOT; and the Braavosi warship Grand Defiance which Alyn Velaryon sinks in the Stepstones is described as a "towering Braavosi dromond of 400 oars."

This isn't how galleys worked at all, although in fairness to George his misconceptions were widely held prior to the 20th century. As Michael Pitassi notes in Hellenistic Naval Warfare and Warships 336-30 BC, Classical sources mention no more than three classes of rower (called thranite, zygite and thalamite from top to bottom) nor do we have any iconography suggesting more than three horizontal levels or remes of rowers on classical galleys (Pitassi, Hellenistic Naval Warfare, 97). This means that designations higher than trireme referred not to the number of remes but to the number of rowers manning the oars in a vertical 'group'; thus a 'five' was a trireme with it's thranite and zygite oars double-manned (2+2+1=5). Oars are also unworkable at an operating angle of more than 30 degrees, meaning that while oars could be up to 17.4m in length as with the thranite oars on Ptolemy IV's massive 'Forty,' the height of most polyreme galleys was limited compared to pure sailing ships (Ibid., 97-101). Just to demonstrate how far off George's conceptualizations are, the Grand Defiance has the same number of oars as the 'Forty,' the largest galley known to have been built and which never put to sea, let alone saw battle. Similarly, the term 'four-decker' used for Honor of Oldtown properly applies to ships-of-the-line which have four gun decks; only three such vessels were ever built, Santísima Trinidad, Pennsylvania, and Valmy, with Santísima Trinidad being the only one to see naval combat.

The other issue with the portrayal of galleys is their use of ramming tactics, which were not used by the Byzantine dromons and Venetian galleys that George claims were his inspirations, but this appears to be an honest mistake. The naval rams in the books are described as being iron, whereas rams in classical antiquity were made from bronze; John Pryor notes in Age of the Dromon that Medieval and Early Modern galleys did carry an iron device called a spur on their prows, but this was misinterpreted by R. H. Dolley in 1948 as being a ram (Pryor, Age of the Dromon, 204). Unlike the waterline ram of Graeco-Roman galleys, which was built as an integral part of the keel and stempost with the stempost being straight and reinforced, the spur was attached by chains or coupling to the stempost which was raked upwards like that of a merchant vessel (Ibid., 136-140). Combined with the long, thin design of the spur compared to the flat, hammer-like design of the waterline ram, this indicates the spur was not designed for a head-on impact with the opponent's hull. Instead, Medieval sources indicate the spur's job was to allow the galley to ride up and over the opponent's oars, smashing them and immobilizing the enemy galley to allow it to be boarded (Ibid., 143-144).

Naval ramming was possible in the Mediterranean of antiquity because ships were constructed 'shell first,' using mortises cut into the planks or strakes of the hull to insert tenons which were held in place with wooden pegs, allowing the strakes to be held together edge-to-edge (Ibid., 145). Rams were likely designed to shatter the waterline wale (i.e. the out planks of the hull near or below the water) or cause it to flex markedly, dislodging frames and tearing loose the mortise and tenon joints, causing the planks to split down the middle and resulting in the hull rapidly flooding (Ibid., 145-146). The preference for lighter softwoods in Mediterranean shipbuilding also facilitated this; by contrast, shell-first construction in Northern Europe was based on the 'clinker' tradition where the strakes overlapped and were held together by iron nails, the preference being for hard woods and oak in particular. Julius Caesar's Commentaries on the Gallic War reports that the Gallic ships built in this way were impervious to ramming, and the shift from mortise and tenon to 'frame first' or Carvel construction in the Medieval Mediterranean likewise cancelled out the effectiveness of naval ramming, which seems to have disappeared in Late Antiquity (Ibid., 146-147).

Byzantine dromons and Venetian galleys were much closer to the galleys of 100-200 oars or less mentioned in the books. At the height of its usage during the Macedonian Dynasty of the Byzantine Empire, the dromon was a bireme galley with one reme of oars above deck and one below, with each side having 25 single-manned oars (Pryor, "Byzantium and the Sea," 85-86). The dromon had an overall length of 31.25 meters with a deadweight tonnage of 25 tonnes; 2 triangular Lateen sails assisted with propulsion while the crew numbered 150 men, of which 108 were the ousia or rowing crew (Ibid.). A siphon or greek fire projector was mounted below the forecastle in the dromon's prow, while castles were also located around the foremast for missile troops to man during battle (Pryor, Age of the Dromon, 203-205). The Byzantines also operated a smaller vessel with a single mast called the galea, from which the term 'galley' is derived and whose design would inspire the later galleys of the Venetians and other powers in the western Mediterranean (Pryor, "Byzantium," 86).

The galleys that eventually replaced the dromon differed little from it in size, the key difference being how they were rowed: the oarsmen were now located entirely above deck, and were seated side-by-side on angled benches with each rowing their own oar in a style that became known as alla senzile (Pryor, Age of the Dromon, 430). This style co-existed with another that eventually replaced it, a scaloccio, which used a single heavy oar instead of individual, lighter oars and could be rowed by as many as 5-7 oarsmen at one oar (Mauro Bondioli et al, "Oar Mechanics and Oar Power in Medieval and later Galleys," 191-192). George's multi-decked galleys would face the severe challenge of supplying air to the rowers and keeping them cool owing to the heat, CO2, and sweat produced by the oarsmen at work, a problem which Medieval galleys solved by placing their oarsmen above deck (Pryor, Age of the Dromon, 435, 443). This also freed up space in the hold of the galley to carry more personnel and supplies, and to accommodate ballast to stabilize the galley in rough conditions. The greater power of the new rowing methods allowed for larger galleys to be built, with three-sailed, trireme alla senzile galleys being used as merchant vessels for voyages between Venice and Flanders in the 15th century (Ulrich Alertz, "The Naval Architecture and Oar Systems of Medieval and later Galleys," 158-159).

iv. Like the Vikings, except they suck

We'll discuss galley performance more when we come back to the question of sea control, but I want to cover the Ironborn and their ships first, as well as the importance of sailing ships. George seems to believe that the Ironborn longships are based off the iconic 'Viking' longships of Early Medieval Europe, but the descriptions we get do not support this. The one good description we have of a 'longship' comes from Theon II of ACOK, in which a new longship is described as 100 feet long with a single mast and 50 oars, with deck enough for 100 men and an arrowhead-like iron ram on it's prow. This ship cannot be one of the galleys of the Iron Fleet, as Theon mentions it is not so large as Balon's Great Kraken or Victarion's Iron Victory. It's length and rigging is almost identical to that of Skuldelev 2, the great longship discovered by archaeologists in the Roskilde Fjord of Denmark in 1962, which had a single mast and a length of 98.5 feet (Owain Roberts, "Descendants of Viking Boats," 15). On the other hand, the deck space of Skuldelev 2 seems to have been limited to elevated decks on the bow and stern (Ibid., 19), and since 'Viking' ships never carried rams, the 'longships' of the Ironborn come off more as small, monoreme war galleys. This also appears to be how Ironborn 'longships' looked in the past, since Dalton Greyjoy was able to sink 25% of the ships in Lannisport harbour and was later prepared to meet Alyn Velaryon's fleet in battle, indicating his ships also had rams.

The problem with this 'longship' design is that it is very poorly suited to the tasks the Ironborn carry out during the Dance. I already alluded to the vulnerability of the Ironborn to the autumn and winter weather in Part Two of this series, but I must stress that the distances the Ironborn cover in the conditions they should be facing are simply unfeasible. For Dalton's surprise raid on Lannisport to work, he would need to avoid the coast and travel on the open sea; using Atlas of Ice and Fire's map scale, the distance as the crow flies from Pyke to Lannisport via Feastfires looks to be 650 miles (1000km), and avoiding the coast would probably push this to 700-800 miles (c.1127-1287 km). By comparison, Norse sailings to North America via the Greenland-Iceland-UK gap traveled along the coast whenever they could, sticking to Greenland's shore at the end and following Baffin Island down to Newfoundland, a journey of about 700 to 800 nautical miles or c.1300-1500km. Dalton's journey would be shorter than traveling from Norway to North America by a few hundred kilometers, but he'd be making it at the wrong time of year (autumn-winter, not summer), and in the wrong kind of boat. 'Longships,' like galleys, were best suited to shallow waters while sailing vessels called knarrs were used for travelling the open seas and voyaging from Europe to North America. Funnily enough, this illustrates Mahan's point about strategic lines quite well: the fastest and safest route to strike at Lannisport would be the coastal one through the Straits of Fair Isle, but since this would make surprise impossible Dalton would have to take a longer route via the open sea and risk losing most if not all his ships to the adverse weather.

This brings us to sailing ships, which have a serious advantage over galleys thanks to their freeboard, i.e. the distance between the waterline and the gunwale of a boat. As Timothy Runyan notes in his essay "The Cog as Warship," the Bremen Cog was 4.2 meters high from keel to gunwale amidships compared to 1.9 meters for the Gokstad Ship, a longship some 20 feet shorter than Skuldelev 2 (Runyan, "Cog as Warship," 50). Their actual freeboard would have been shorter, but the Cog would still have been much better served than the 'longship.' When it comes to the sailing ships used during the Dance, we know that the Velaryon fleet had cogs and 'great cogs' under it's command, and Alyssa Farman's ship Sun Chaser was a four-masted carrack built in 54-55 AC, although no carracks are mentioned in the context of the Dance. Carracks were the largest ships of the Late Medieval and Early Modern periods, first appearing in the mid-to-late 14th century and eventually giving rise to 'Great Ships' like Sweden's Vasa and England's Mary Rose. They were generally three or four-masted ships, with wide and deep hulls in keeping with F&B's description of Sun Chaser, and tended towards a minimum of 300-400 tonne capacity (Ian Friel, "The Carrack: The advent of the Fully-Rigged Ship," 85). Cogs were flat-bottomed one-masted ships and were much smaller than carracks in general; my guess is that the 'great cog' is reminiscent of the Genoese cocha, a Mediterranean derivative of the cog which later gave rise to the carrack, and probably has two masts instead of one.

The problem that sailing ships represent for the Ironborn is that galleys have a very poor 'match up' against them historically. In his essay "The New Atlantic: Naval Warfare in the Sixteenth Century," N.A.M. Rodgers notes that because boarding actions were the dominant form of naval combat in the Late Medieval Period, "the size of sailing ships gave them an overwhelming advantage over galleys, with their exposed crews and low freeboard" (Rodgers, "New Atlantic," 244). An excellent example of this mismatch was the Danish siege of Stockholm from 1389 to 1394, when Queen Margaret's armies and longships surrounded and blockaded the city but the cogs of the Victual Brothers ran the blockade and kept the defenders supplied (Alex Querengasser, "Klaus Störtebeker and the Victual Brotherhood," 13). These asymmetries meant that galleys and ships were used for different purposes, the former being employed in coastal operations, raids, and landings where their shallow draught gave them an advantage, whereas the latter were used to cross open seas and carry large quantities of troops and supplies, as well as for engaging other ships (Ibid.). This situation only really changed at the beginning of the 16th century, when cannons capable of sinking ships were developed and galleys mounted them on their bows, enabling them to target ships close to their waterlines (Rodgers, "New Atlantic," 244-245). The Ironborn need proper sailing ships to conduct raids over long distances and in rough seas as they do in the Dance, but aside from prizes and fishing vessels they rely entirely on 'longships' whose designs are unsuited for this.

v. Whither the Velaryon blockade

Now that we have an idea of the vessels available to our fleets during the Dance, we can return to Mahanian naval strategy and the question of sea control. Sea control doesn't really factor into the Ironborn due to their warfare relying mostly on raiding, but it absolutely does for the Velaryon fleet. Although I've covered the Velaryon Blockade already, I want to return to the subject by answering two questions: Is it possible for the Velaryons to 'control' entry and egress through the Gullet; and is Otto's plan to enlist the Triarchy to break the blockade workable? If we allow that Mahanian sea power can be applied conceptually to the setting, does this mean that Mahanian naval strategy via sea control is realizable with the tools available to the setting?

F&B takes it for granted that the Gullet blockade is possible: the Velaryon fleet gives Rhaenyra "superiority at sea" while Daemon asserts that only through winning over the Ironborn could Aegon mount a challenge at sea; the Black Council decides that the Velaryon fleet will "close off the Gullet" blocking all traffic "entering or leaving Blackwater Bay," and the Sea Snake's ships set sail after Rhaenyra's coronation "to close the Gullet, choking off trade to and from King's Landing." 'Command of the sea' was a recognized concept in classical antiquity, with N.A.M Rodger noting that something like 'sea control' was a feature of the wars between Venice and Genoa in the High and Late Middle Ages and in the Baltic naval wars of the mid-16th century, but this was unusual in Europe prior to the 17th century (Rodgers, "New Atlantic," 237). John Dotson provides details on the wars of Venice and Genoa in "The Economics and Logistics of Galley Warfare," accepting that galley fleets could not drive an enemy from the seas or blockade ports in the style of the Royal Navy during the 18th and 19th centuries, while dominating one or more entrepôts like the Black Sea, the eastern Mediterranean shore, or Alexandria was beyond the economic and naval capabilities of any Medieval sea power (Dotson, "Economics and Logistics," 218).

Nonetheless, the wars of Venice and Genoa showed that some kind of control could be exerted thanks to the combination of the Mediterranean's geography, winds, and currents, which created focal points around islands and coastal routes where shipping could be intercepted from bases, with the 'closing of the sea' in autumn placing even greater importance on these routes at specific times (Ibid.). Dotson calculates a 150km radius for galleys operating at their extreme operational endurance, allowing for 4-7 days at sea with 2-3 being the case for a round trip (Ibid.). Dotson's findings are of no use to the Velaryons however, thanks to the geography and weather of the Gullet in 129-130 AC: using Atlas' map scale, the Gullet looks to be c.70-80 miles (c.113-129km) wide from High Tide to Sharp Point, making it just under Dotson's radius, but since galleys would usually put in to shore at night, the range of Velaryon galleys drops to less than 30km with nothing but open waters between High Tide and Sharp Point; Dotson is also analyzing Venetian and Genoese operations that would have taken place in-season, whereas the Velaryons are mounting a blockade in autumn when the conditions would probably be too dangerous for galleys to operate; Dotson is also talking about coastal shipping routes, while 'closing off the Gullet' would be unnecessary if all that was needed was to intercept coastal shipping around Driftmark and Sharp Point, which means the galleys and 'longships' of the Velaryons can be of no assistance for intercepting ships sailing the open waters of the Gullet itself.

As I concluded in the Velaryon Blockade analysis, the cogs and great cogs of the Velaryon fleet are the only vessels they have that could even attempt a blockade of the Gullet, meaning they can only employ half or less of their fleet for the blockade. We also don't know of any specific shipping lanes within the Gullet itself, meaning that even if the cogs and great cogs could remain 'on station' in an area like the warships of the 18th century, the absence of any lanes to intercept combined with the inclement weather would further rule out the blockade. If the battle line of Stannis' fleet at the Battle of the Blackwater is any indication, sailing ships also seem to be used more as transports and supply ships than as actual warships. For the Velaryons to do anything, we'd no longer be talking about a blockade but 'sea-keeping missions' as they were called in the context of the Hundred Years War, which involved trying to apprehend enemy ships by patrolling with ships of one's own (Timothy Runyan, "Naval Power during the Hundred Years War," 66). Even then, some of the over 100 cogs and great cogs would need to remain in port to act as replacements for damaged or lost ships and to allow ships the opportunity to drydock, which would give blockade runners ample opportunities to escape the Bay thanks to the transient nature of the Velaryons mission. The seasons create further problems, since shorter days will make visual navigation difficult while overcast skies will render navigating using the moon and stars almost impossible. This is why Planetos needs the compass for navigation, as China had by the 11th century and Europe and the Middle East by the 12th-13th centuries; the word itself appears just once in the prologue of ACOK, but it must be present if George expects anyone to be travelling by sea at all in the winter.

It simply isn't possible for the Velaryons to blockade the Gullet, let alone exercise Mahanian sea control over it's waters, and Otto's plan involving the Triarchy fairs no better. The distance from Tyrosh to High Tide looks to be over 750 miles (c.1200km) as the crow flies, and since F&B's description of the Battle of the Gullet suggests most if not all the Triarchy warships were galleys, this plan runs into the same distance problems as the Velaryons. Their reliance on galleys rules out traveling the open sea, which means the Triarchy fleet would have to take a coastal route either north towards Old Andalos and then crossing over to Crackclaw Point, or west to Cape Wrath before coasting via Shipbreaker Bay or more likely Tarth, entering the Gullet from the south via Massey's Hook. Once again the setting inadvertently supplies us another example of the importance of strategic lines: since the shortest, most direct route via the open sea is unavailable, the Triarchy must rely on coastal routes that would bring them into contact with those sympathetic to Rhaenyra's cause, either the Pentoshi or Houses Tarth, Massey, and Bar-Emmon, spoiling their surprise attack even without the heroics of Aegon III and Stormcloud. Of course those routes would probably also rule out running into the Gay Abandon, so the entire Narrow Sea plot of the Dance ends up null and void, let alone the Velaryon blockade.

vi. Conclusion

I'll once again save the bulk of the 'fix-its' for the sections on strategy in the Dance (just two more parts to go, I promise!). Nevertheless, reining in the scale would go a long ways towards making things more believable; it's too late to pay the sailors as it is for the soldiers, but keeping the ships believable would be the best route to take. If anything, relying on fantasy polyremes was unnecessary if George wanted to have fantastic ships in his setting: the Venetians operated an alla senzile quinquereme or 'five' in the mid-16th century (i.e. five men to a bench rowing five oars), and Henry V's warship Grace Dieu was as large as HMS Victory despite being built in the 15th century! Otherwise I suggest re-reading the Velaryon Blockade post for my 'fix-its' there, as they'll be relevant later on in this series; with that being said, thank you once again for reading and I'll see you next time for 'Dragon Warfare'!

#house of the dragon#hotd#asoiaf#asoiaf critical#grrm#grrm critical#fire and blood#fire and blood critical#corlys velaryon#alyn velaryon#dalton greyjoy

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

• USS Intrepid

USS Intrepid (CV/CVA/CVS-11), also known as The Fighting "I", is one of 24 Essex-class aircraft carriers built during World War II for the United States Navy. She is the fourth US Navy ship to bear the name. Commissioned in August 1943, Intrepid participated in several campaigns in the Pacific Theater of Operations. Because of her prominent role in battle, she was nicknamed "the Fighting I", while her frequent bad luck and time spent in dry dock for repairs—she was torpedoed once and hit in separate attacks by four Japanese kamikaze aircraft—earned her the nicknames "Decrepit" and "the Dry I".

The keel for Intrepid was laid down on December 1st, 1941 in Shipway 10 at the Newport News Shipbuilding & Dry Dock Co., Newport News, Virginia, days before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor and the United States' entrance into World War II. She was launched on April 26th, 1943, the fifth Essex-class aircraft carrier to be launched. She was sponsored by the wife of Vice Admiral John H. Hoover. In August 1943, she was commissioned with Captain Thomas L. Sprague in command before heading to the Caribbean for shakedown and training. She thereafter returned to Norfolk, before departing once more on December 3rd, bound for San Francisco. She proceeded on to Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, arriving there on 10 January, where she began preparations to join the rest of the Pacific Fleet for offensive operations against the Imperial Japanese Navy.

Intrepid joined the Fast Carrier Task Force, then Task Force 58 (TF 58), for the next operation in the island-hopping campaign across the Central Pacific: the Gilbert and Marshall Islands campaign. On January 16th, 1944, Intrepid, her sister ship Essex, and the light carrier Cabot left Pearl Harbor to conduct a raid on islands in the Kwajalein Atoll from January 29th to February 2nd. The three carriers' air group destroyed all 83 Japanese aircraft stationed on Roi-Namur in the first two days of the strikes, before Marines went ashore on neighboring islands on January 31st, in the Battle of Kwajalein. That morning, aircraft from Intrepid attacked Japanese beach defenses on Ennuebing Island until ten minutes before the first Marines landed. The Marines quickly took the island and used it as a fire base to support the follow-on attack on Roi. After the fighting in the Kwajalein Atoll finished, on February 3rd, Intrepid and the rest of TF 58 proceeded to launch Operation Hailstone, a major raid on the main Japanese naval base in the Central Pacific, Truk Lagoon. From the 17th to 19th of February, the carriers pounded Japanese forces in the lagoon, sinking two destroyers and some 200,000 GRT (gross register tonnage) of merchant ships.

The strikes demonstrated the vulnerability of Truk, which convinced the Japanese to avoid using it in the future. Intrepid did not emerge from the operation unscathed, however; on the night of 17th–18th of February, a Rikko type Torpedo Bomber from the 755th Kōkūtai (Genzan Air Group) flying from Tainan attacked and torpedoed the carrier near her stern. The torpedo struck 15 ft (5 m) below the waterline, jamming the ship's rudder to port and flooding several compartments. Sprague was able to counteract the jammed rudder for two days by running the port side screw at high speed while idling the starboard screw, until high winds overpowered the improvised steering. The crew then jury-rigged a sail out of scrap canvas and hatch covers, which allowed the ship to return to Pearl Harbor, where she arrived on February 24th. Temporary repairs were effected there, after which Intrepid steamed on March 16th, escorted by the destroyer USS Remey, to Hunters Point Naval Shipyard in San Francisco for permanent repairs, arriving there six days later. The work was completed by June, and Intrepid began two months of training around Pearl Harbor. Starting in early September, Intrepid joined operations in the western Caroline Islands; the Fast Carrier Task Force was now part of the Third Fleet under Admiral William Halsey Jr., and had been renamed Task Force 38. On September 6th and 7th, she conducted air strikes on Japanese artillery batteries and airfields on the island of Peleliu, in preparation for the invasion of Peleliu. On the 9th and 10th of September, she and the rest of the fleet moved on to attack airfields on the island of Mindanao in the Philippines, followed by further strikes on bases in the Visayan Sea between the 12th and 14th of September. On September 17th, Intrepid returned to Pelelieu to provide air support to the Marines that had landed on the island two days before.

Intrepid and the other carriers then returned to the Philippines to prepare for the Philippines campaign. At this time, Intrepid was assigned to Task Group 38.2. In addition to targets in the Philippines themselves, the carriers also struck Japanese airfields on the islands of Formosa and Okinawa to degrade Japanese air power in the region. On October 20th, at the start of the Battle of Leyte, Intrepid launched strikes to support Allied forces as they went ashore on the island of Leyte. By this time Halsey had reduced the carriers of TG 38.2, commanded by Rear Admiral Gerald F. Bogan aboard Intrepid, to just Intrepid, Cabot, and the light carrier Independence. Between the 23rd and 26th of October, the Japanese Navy launched a major operation to disrupt the Allied landings in the Philippines, resulting in the Battle of Leyte Gulf. On the morning of October 24th, a reconnaissance aircraft from Intrepid spotted Vice Admiral Takeo Kurita's flagship, Yamato. Two hours later, Intrepid and Cabot launched a strike on Kurita's Center Force, initiating the Battle of the Sibuyan Sea; this included eight Curtiss SB2C Helldiver dive bombers from Intrepid. One 500-pound (230 kg) bomb struck the roof of Turret No. 1, failing to penetrate. Two minutes later, the battleship Musashi was struck starboard amidships by a torpedo from a Grumman TBF Avenger, also from Intrepid. The Japanese shot down two Avengers. Another eight Helldivers from Intrepid attacked Musashi again at around noon, scoring two more hits, with two Helldivers shot down. Further strikes from Essex and Lexington inflicted several more bomb and torpedo hits, 37 aircraft from Intrepid, the fleet carrier Franklin, and Cabot attacked Musashi, hitting her with 13 bombs and 11 torpedoes for the loss of three Avengers and three Helldivers. In addition to the loss of Musashi, many of Kurita's other ships, including battleships Yamato, Nagato and Haruna, and heavy cruiser Myōkō were damaged in the attacks, forcing him to break off the operation temporarily. After Kurita's force began to withdraw, Halsey ordered TF 38 to steam north to intercept the aircraft carriers of the Northern Force, commanded by Vice Admiral Jisaburō Ozawa. Bogan correctly perceived that Ozawa's force was intended to lure TF 38 away from the landing area to allow Kurita to attack it, but Halsey overruled him and several other Task Group commanders who voiced similar concerns. Early on October 25th, aircraft from Intrepid and the other carriers launched a strike on the Japanese carriers. Aircraft from Intrepid scored hits on the carrier Zuihō and possibly the carrier Zuikaku. Further strikes throughout the morning resulted in the sinking of four Japanese aircraft carriers and a destroyer in the Battle off Cape Engaño. Halsey's preoccupation with the Northern Force allowed Kurita the respite he needed to turn his force back to the east, push through the San Bernardino Strait, where it engaged the light forces of escort carriers, destroyers, and destroyer escorts that were directly covering the landing force in the Battle off Samar. Kurita nevertheless failed to break through the American formation, and ultimately broke off the attack.

On October 27th, TG 38.2 returned to operations over Luzon; these included a raid on Manila on the 29th. That day, a kamikaze suicide aircraft hit Intrepid on one of her port side gun positions; ten men were killed and another six were wounded, but damage was minimal. A Japanese air raid on November 25th, struck the fleet shortly after noon. Two kamikazes crashed into Intrepid, killing sixty-nine men and causing a serious fire. The ship remained on station, however, and the fires were extinguished within two hours. She was detached for repairs the following day, and reached San Francisco by December. In the middle of February 1945, back in fighting trim, the carrier steamed for Ulithi, arriving by March. She set off westward for strikes on Japan on March 14th, and four days later launched strikes against airfields on Kyūshū. That morning a twin-engined Japanese G4M "Betty" kamikaze broke through a curtain of defensive fire, turned toward Intrepid, and exploded 50 ft (15 m) off Intrepid's forward boat crane. A shower of flaming gasoline and aircraft parts started fires on the hangar deck, but damage control teams quickly put them out. Intrepid's aircraft joined attacks on remnants of the Japanese fleet anchored at Kure damaging 18 enemy naval vessels, including battleship Yamato and carrier Amagi. The carriers turned to Okinawa as L-Day, the start of the most ambitious amphibious assault of the Pacific war, approached. The invasion began on the 1st of April. Intrepid aircraft flew support missions against targets on Okinawa and made neutralizing raids against Japanese airfields in range of the island. On April 16th, during an air raid, a Japanese aircraft dived into Intrepid's flight deck; the engine and part of the fuselage penetrated the deck, killing eight men and wounding 21. In less than an hour the flaming gasoline had been extinguished; three hours after the crash, aircraft were again landing on the carrier. On April 17th, Intrepid retired homeward via Ulithi. She made a stop at Pearl Harbor on 11 May, arriving at San Francisco for repairs on May 19th. On June 29th, the carrier left San Francisco. On August 6th, her aircraft launched strikes against Japanese on bypassed Wake Island. Intrepid arrived at Eniwetok on the next day. On August 15th, when the Japanese surrendered, she received word to "cease offensive operations." Intrepid got under way on August 21st to support the occupation of Japan.

In February 1946, Intrepid moved to San Francisco Bay. The carrier was reduced in status to "commission in reserve" in August, and she was decommissioned on March 22nd, 1947. After her decommissioning, Intrepid became part of the Pacific Reserve Fleet. On February 9th, 1952, she was recommissioned. Intrepid later severed as an attack carrier (CVA), and then eventually became an antisubmarine carrier (CVS). In her second career, she served mainly in the Atlantic, but also participated in the Vietnam War. She was the recovery ship for a Mercury and a Gemini space mission. She was decommissioned for the second time in 1974, she was put into service as a museum ship in 1982 as the foundation of the Intrepid Sea, Air & Space Museum Complex in New York City. Intrepid earned five battle stars and the Presidential Unit Citation during World War II, and a further three battle stars for Vietnam service.

#second world war#world war 2#world war ii#wwii#military history#american history#naval history#naval warfare#aircraft carrier#intrepid museum#pacific campaign#pearl harbor#us navy

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

“I hate you! I don't ever wanna see your face again!”

Over 1 year later…

“Pete, I know you just got back, but that's no excuse to leave your mess all over the house.”

Having just come home from work, Ice had to bypass Mav’s jacket and horrendous cowboy boots in the middle of the hallway, an empty beer bottle and crumbs of chips leading him to the other man lounging on the couch.

“But you still love me.”

Mav was tiredly smiling up at him, making Ice shake his head fondly.

“Sometimes I wonder why. Even Bradley wasn't-”

Groaning frustratingly, Ice pulled his ringing cell phone out of his pocket, frowning at the unknown number on the display.

“Ignore it…”

“You know I can't… Kazansky, hello?”

“Hello, my name is Gracie Bushman. I’m a nurse at St. Joseph’s Rehabilitation and Care Center in Maryland. Am I speaking to Rear Admiral Thomas Kazansky?”

“Speaking. How may I help you, ma’am?”

“I was referred to you because I’m looking for someone called ‘Mav’ or ‘Maverick’? Also someone possibly nicknamed ‘Ice’?”

“Maverick, Commander Pete Mitchell, is my… wingman from my active days as a naval aviator. That's his callsign, mine was Iceman. But why-?”

“I think you need to come to Maryland as soon as possible.”

~~~

“Thank you for coming so fast.”

Mav and Ice had taken the first flight to Washington, their minds still reeling with what they had heard, now following Gracie through the hallways of the rehab center.

“No problem at all. So, this patient…”

“He had been admitted to hospital as a John Doe after being involved in a car accident. There had been nothing on him to identify him. He had suffered severed head injuries, leaving him in a coma and a vegetative state for several weeks before he was transferred here. He’s been with us for over three months when he slowly started showing signs of awareness. A few weeks ago he started to mumble words, but they didn't make any sense to us at first. But he seemed persistent, so I started researching…”

“And that's how you found us.”

Pete’s voice was barely audible when they finally stopped in front of a door.

“Yeah. Now, before going in, you need to know that he sustained severe scarring in the accident as well. It might take him a while to focus on you. Whatever happens, try not to stress him too much.”

Mav and Ice could only nod as Gracie knocked on the door.

“Hey, honey, you got some visitors today…”

The young man in the bed didn't look up at first. He was pale and thin, red scars all over his face, but there was no doubt…

“Oh my God, Bradley…”

They couldn't hold themselves back anymore. Soon enough Mav was almost crawling onto the bed, wrapping Bradley into his arms as Ice grabbed his boney hands and didn't let go.

“Oh baby goose…”

Very slowly Bradley’s eyes started to take them in and suddenly a loud sob ripped through him. Floods of tears were running down his cheeks.

“Da… Pop…”

There was no single dry eye in the room at this moment.

“Yeah, baby, we’re here… we’re here.”

#pete maverick mitchell#tom iceman kazansky#bradley rooster bradshaw#icemav#iceman x maverick#top gun maverick#top gun angst#top gun drabble

341 notes

·

View notes

Text

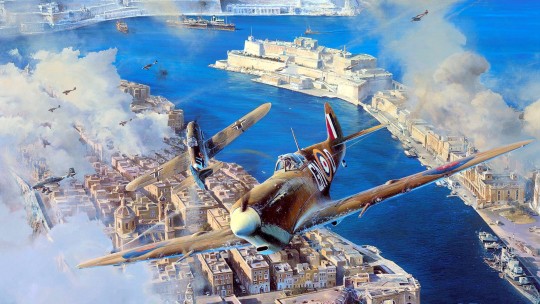

1942 04 Spitifires over Malta - Robert Taylor

Between the summer of 1940 and the end of 1942, Malta became one of the most bombed places on earth. The Royal Air Force's desperate fight to retain control of the diminutive Mediterranean island is one of the epic stories of World War Two.Crucial to the Allies in their battle with the Axis forces in North Africa, Malta's naval dockyards and airfields provided the only base from which ships and aircraft could attack the convoys supplying Rommel's desert forces. The German High Command, fully aware of its importance, made every effort to bomb the island out of existence. By April 1942 the RAF was down to just six serviceable Spitfires and Hurricanes, Allied convoys were being decimated unopposed, and Malta was in danger of starvation. Two and a half years of relentless bombing had blitzed the dockyards out of operation, prompting Axis Commander-in-Chief Field Marshal Kesselring to tell Hitler that Malta was neutralized.But the Field Marshal failed to take into account the heroism of a tiny force of RAF fighter pilots, the British Merchant Navy, the decisive role played by the British aircraft carriers Eagle and Furious, the American carrier Wasp, and the iron will of the people of Malta.In the spring of 1942, when Spitfires flown from the decks of carriers HMS Eagle and USS Wasp, arrived at the island's battered airstrips, the battle took a new turn. At last, though still heavily outnumbered, the volunteer pilots from Britain, Australia, America, Canada, New Zealand, and other Commonwealth countries were able to put up a meaningful defense. Never again would the Axis raids be met only with token resistance and gradually the Spitfires began to dominate the sky above the beleaguered island. They had arrived in the nick of time.Robert Taylor's magnificent tribute to the gallant pilots who fought against such overwhelming odds, and the people of Malta, depicts Australian John Bisley of 126 Squadron dog-fighting with an Me109 from JG-53 during one of the intense aerial air battles over Valetta in April 1942. NOTE: The Maltese people had withstood the siege with such resolve, King George VI, by way of recognition, awarded the island of Malta the George Cross - the highest decoration for civilian gallantry. Such was the sacrifice made by the people of this tiny island.

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

Memorial Brooch to Rear Admiral McKerlie, Died 12th Septr 1848. Aged 74 years, 1848

Rear Admiral John McKerlie (1774-1848) entered the Royal Navy as a volunteer in April 1794 having been at sea in the Atlantic and Baltic merchant service from a young age. Rated Able Seaman, he was sent from the receiving ship Royal William to join the elite frigate force based at Falmouth that cruised the Channel countering the activities of French commerce raiders. McKerlie was assigned to the frigate Arethusa (38) commanded by one of the most successful frigate captains of the day, Captain Sir Edward Pellew.

In early 1795 McKerlie followed Pellew into the 44-gun heavy frigate Indefatigable with the rate of Quarter-Gunner. Owing to a sound Scottish education and his knowledge of the sea McKerlie was soon acting as Indefatigable’s schoolmaster instructing the other eighteen ‘young gentleman’ of the gunroom in the specifics of their profession, having himself been appointed a midshipman. Throughout 1795 and 1796 he participated in the capture of the numerous French prizes which brought further fame and glory to Sir Edward Pellew. It was however early the next year that Indefatigable fought what is generally regarded as one of the boldest frigate actions of the French Revolutionary War.

On the dark and stormy night of 13 January 1797 the French 74 Droits de l’Homme was sighted off the Brittany coast. Pellew, recognizing that he was heavily outclassed, saw that the waves prevented his opponent from opening the lower gun ports and that the severe weather had caused the loss of the enemy’s topmasts. Seizing the initiative, Indefatigable closed followed by the frigate Amazon and raked the French ship of the line at every opportunity. The enemy replied with 4,000 canon balls over the next few hours until finally driven in to Audierne Bay irreparably damaged by British gunfire and the unabated gale. The sight of distant breakers however threatened the destruction of all three ships. Indefatigable, though with masts damaged and with four feet of water in her hold, alone just had time to alter course and escape.

For Pellew the action was a triumph, Lord Spencer at the Admiralty acknowledging that for two frigates to destroy a ship of the line was ‘an exploit which has not I believe ever before graced our naval Annals’. For McKerlie the action was a trauma, costing him his right arm and a severe wound to the thigh. McKerlie's sacrifice was deeply felt Sir Edward Pellew whom he followed to his subsequent command, the mutinous ship of the line Impetueux. While serving aboard the Impetueux, McKerlie participated in numerous boat actions during the Quiberon expedition in 1800, and was present during the planning of a proposed attack on Belleisle. Marshall’s Royal Naval Biography relates how McKerlie ‘…not having heard how he was to be employed, went up to Sir Edward, interrupted him in a conversation with Major-General Maitland, and asking what part he was to act in the event of a debarkation taking place? The answer was “McKerlie you have lost one hand already, and if you loose the other you will not have anything to wipe your backside with; you will remain on board with the first lieutenant and fight the ship as she is to engage an 8-gun battery.”’

The loss of an arm did little to impede McKerlie’s career. He was regarded as a talented surveyor and draftsman, working at onetime with the celebrated civil engineer Thomas Telford. He was also considered a first class shot. He received his lieutenant’s commission in 1804 and served in H.M.S. Spartiate at the Battle of Trafalgar on 21 October 1805. He was present in the capture of Flushing and the Walcheren expedition, and commanded a squadron of ships stationed off Heligoland; oversaw the defence and retreat from Cuxhaven; and was responsible for destroying enemy shipping on the Braak.

Unable to get a command after 1813, McKerlie returned to his native Galloway where he married, Harriet, daughter of James Stewart of Cairnsmuir, had one daughter, Lillias (1821-1915), to either or both of whom the present brooch no doubt belonged. In a post service career McKerlie served as a local magistrate and operated commercial vessels from the port of Garlieston. After almost twenty years ashore, he made an unlikely returned to the Royal Navy as captain of the experimental frigate Vernon between 1834 and 1837. He was awarded a Pension for Wounds on 8 May 1816.

Despite the ever growing kudos that was accorded to Trafalgar veterans in the early Victorian age, it is perhaps with greater pride that Admiral McKerlie recalled his service under Pellew (or Lord Exmouth, as he became); and in 1847 was one of only eight surviving veterans who had lived long enough to apply for the Naval General Service Medal with a clasp for the Droits de L’Homme engagement. The following year, in 1848, he died at Corvisel House, Newton Stewart, at the age of seventy-three.