#IMAGINARY LANDSCAPES

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

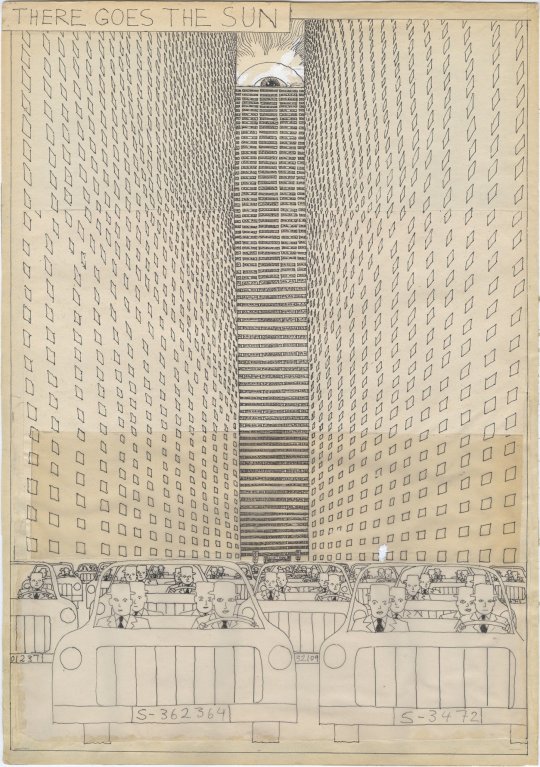

Hariton Pushwagner's visual novel ‘Soft City’ (1969–1975)

The narrative of Soft City is deeply connected to traditional dystopian science fiction. "Astounding depictions of dystopian, alienating reiteration." While it evokes Fritz Lang’s Metropolis and the social division of Blade Runner, as well as the imagery of Hilberseimer’s Großstadt, the primary inspiration for Terje Brofos.

Silkscreen prints from the series 'One Day in the Life of the Mann Family', which arose from a lengthy visual/literary collaboration between Pushwagner and the author Axel Jensen. The series was printed by the screen printer Gunner Fredriksen in 1980.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

LARRY CARLSON

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

#queue of angles#art#artist: noah-kh#god of the forest#living woods#magical#imaginary landscapes#(probably?)#saved: 20100209#(saved date is probably wrong)#2010

0 notes

Text

Landscape with Overthrown Statue by Carel Willink

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

In fact, far more Asian workers moved to the Americas in the 19th century to make sugar than to build the transcontinental railroad [...]. [T]housands of Chinese migrants were recruited to work [...] on Louisiana’s sugar plantations after the Civil War. [...] Recruited and reviled as "coolies," their presence in sugar production helped justify racial exclusion after the abolition of slavery.

In places where sugar cane is grown, such as Mauritius, Fiji, Hawaii, Guyana, Trinidad and Suriname, there is usually a sizable population of Asians who can trace their ancestry to India, China, Japan, Korea, the Philippines, Indonesia and elsewhere. They are descendants of sugar plantation workers, whose migration and labor embodied the limitations and contradictions of chattel slavery’s slow death in the 19th century. [...]

---

Mass consumption of sugar in industrializing Europe and North America rested on mass production of sugar by enslaved Africans in the colonies. The whip, the market, and the law institutionalized slavery across the Americas, including in the U.S. When the Haitian Revolution erupted in 1791 and Napoleon Bonaparte’s mission to reclaim Saint-Domingue, France’s most prized colony, failed, slaveholding regimes around the world grew alarmed. In response to a series of slave rebellions in its own sugar colonies, especially in Jamaica, the British Empire formally abolished slavery in the 1830s. British emancipation included a payment of £20 million to slave owners, an immense sum of money that British taxpayers made loan payments on until 2015.

Importing indentured labor from Asia emerged as a potential way to maintain the British Empire’s sugar plantation system.

In 1838 John Gladstone, father of future prime minister William E. Gladstone, arranged for the shipment of 396 South Asian workers, bound to five years of indentured labor, to his sugar estates in British Guiana. The experiment with “Gladstone coolies,” as those workers came to be known, inaugurated [...] “a new system of [...] [indentured servitude],” which would endure for nearly a century. [...]

---

Bonaparte [...] agreed to sell France's claims [...] to the U.S. [...] in 1803, in [...] the Louisiana Purchase. Plantation owners who escaped Saint-Domingue [Haiti] with their enslaved workers helped establish a booming sugar industry in southern Louisiana. On huge plantations surrounding New Orleans, home of the largest slave market in the antebellum South, sugar production took off in the first half of the 19th century. By 1853, Louisiana was producing nearly 25% of all exportable sugar in the world. [...] On the eve of the Civil War, Louisiana’s sugar industry was valued at US$200 million. More than half of that figure represented the valuation of the ownership of human beings – Black people who did the backbreaking labor [...]. By the war’s end, approximately $193 million of the sugar industry’s prewar value had vanished.

Desperate to regain power and authority after the war, Louisiana’s wealthiest planters studied and learned from their Caribbean counterparts. They, too, looked to Asian workers for their salvation, fantasizing that so-called “coolies” [...].

Thousands of Chinese workers landed in Louisiana between 1866 and 1870, recruited from the Caribbean, China and California. Bound to multiyear contracts, they symbolized Louisiana planters’ racial hope [...].

To great fanfare, Louisiana’s wealthiest planters spent thousands of dollars to recruit gangs of Chinese workers. When 140 Chinese laborers arrived on Millaudon plantation near New Orleans on July 4, 1870, at a cost of about $10,000 in recruitment fees, the New Orleans Times reported that they were “young, athletic, intelligent, sober and cleanly” and superior to “the vast majority of our African population.” [...] But [...] [w]hen they heard that other workers earned more, they demanded the same. When planters refused, they ran away. The Chinese recruits, the Planters’ Banner observed in 1871, were “fond of changing about, run away worse than [Black people], and … leave as soon as anybody offers them higher wages.”

When Congress debated excluding the Chinese from the United States in 1882, Rep. Horace F. Page of California argued that the United States could not allow the entry of “millions of cooly slaves and serfs.” That racial reasoning would justify a long series of anti-Asian laws and policies on immigration and naturalization for nearly a century.

---

All text above by: Moon-Ho Jung. "Making sugar, making 'coolies': Chinese laborers toiled alongside Black workers on 19th-century Louisiana plantations". The Conversation. 13 January 2022. [All bold emphasis and some paragraph breaks/contractions added by me.]

#abolition#tidalectics#caribbean#ecology#multispecies#imperial#colonial#plantation#landscape#indigenous#intimacies of four continents#geographic imaginaries

463 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pages 1 and 2 out of 7!

Will link future pages here as a master post as I complete them in the future.

Had my own thoughts on the whole Astarion + The Last Unicorn thing, and ended up drawing a whole comic about it. So yeah, hope you guys enjoy and stay tuned!

The Unicorn

Next page!

Page 4

Page 5

Page 6

Page 7

#art#fanart#comic#fancomic#bg3#astarion#the last unicorn#baldur's gate 3#astarion ancunin#designing the unicorn was fun#it's based heavily on how it's described in the book#but i took some liberties here and there in terms of palette and other small details#when you think about it the way it's described unicorns are kind of nightmare horses lol#and if you think it looks normal now#wait.#imaginary landscaping is my passion

167 notes

·

View notes

Text

Giorgio de Chirico. La grande ciminiera, 1958.

oil on canvas

95 notes

·

View notes

Text

Zdravko Ćosić (1941-2006) — Imaginary Landscape [oil, canvas, 1973]

73 notes

·

View notes

Text

Landscape with Grotto and a Rider, Joos de Momper the Younger, ca. 1616

#art#art history#Joos de Momper#Joos de Momper the Younger#landscape#landscape painting#imaginary landscape#Mannerism#Mannerist art#Northern Mannerism#Baroque#Baroque art#Flemish Baroque#Flemish art#17th century art#oil on canvas#Yale University Art Gallery

363 notes

·

View notes

Photo

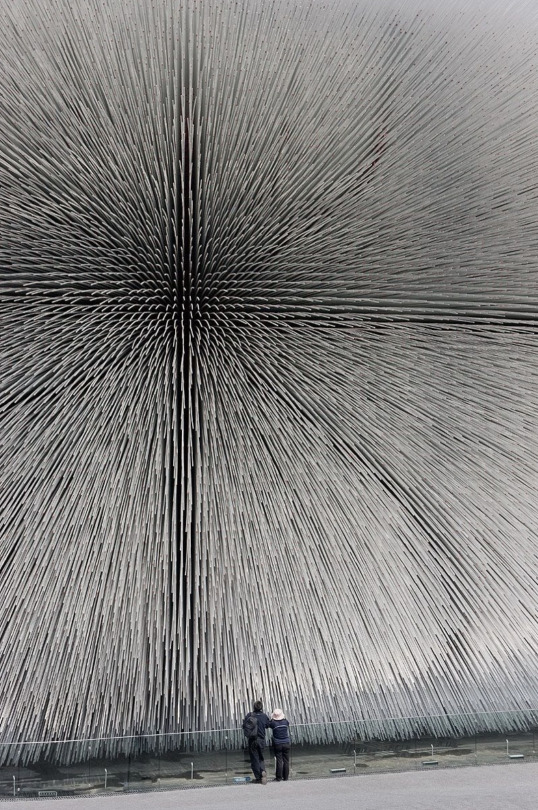

HEATHERWICK STUDIO THE SEED CATHEDRAL, 2010 Expo Shangai, China Images © Iwan Baan

#architecture#design#designer#ignant#thisispaper#artwork#imaginary#mulitmedia#details#expo#exhibition#construction#structure#material#Pavilion#artistic expression#landscape#urban#photography#form#architectural form#space#juliaknz

395 notes

·

View notes

Text

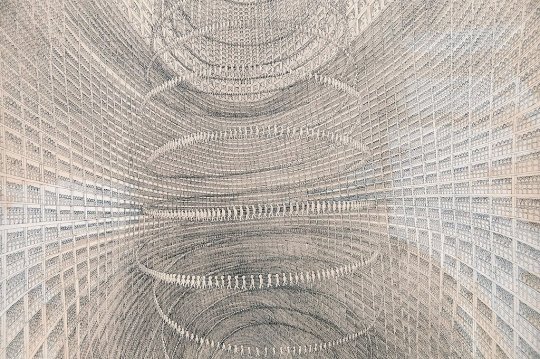

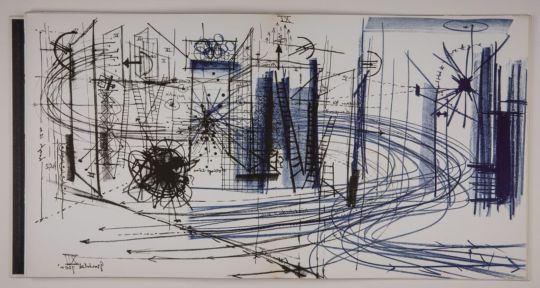

New Babylon, Constant Nieuwenhuys

New Babylon is an anti-capitalist city perceved and designed in 1959-74 as a future potentiality by visual artist Constant Nieuwenhuys.

Origin of the name

Initially known as Dériville (from "ville dérivée", literally, "drift city"), it was later renamed New Babylon.

Henri Lefebvre explained: "a New Babylon -- a provocative name, since in the Christian tradition Babylon is a figure of evil. New Babylon was to be the figure of good that took the name of the cursed city and transformed itself into the city of the future."

A utopian blueprint

In 1956, Western countries were at the dawn of a magmatic period that would reach its peak in the socio-political turmoil of 1968. During that year, the avant-garde Dutch artist Constant Nieuwenhuys started to work on an utopical project named New Babylon: a radical attempt to re-imagine the urban landscape and to question fundamental principles of architecture. New Babylon was a speculative city envisaged through media like collages, litographs and maps. This imaginary city was designed as:

“A decentered, multi-layered space for living, with underground and ground levels, as well as numerous layers above ground and terraces as the final icing. Configured as a rhizomatic network of huge links, it was made of a series of interlocking platforms raised above the Earth’s surface upon pilotis. These were built into various autonomous yet connected units—called sectors.” (Source)

This vision was born from a milieu of different perspectives, such as early cybernetics, 60’s urban subcultures, and artistic avant-garde movements, such as the Situationist group, to which Constant belonged to. New Babylon was planned for a ‘ludic’ society, where humanity is free from waged work and free to engage in all kinds of creative activities.

Read:

0 notes

Text

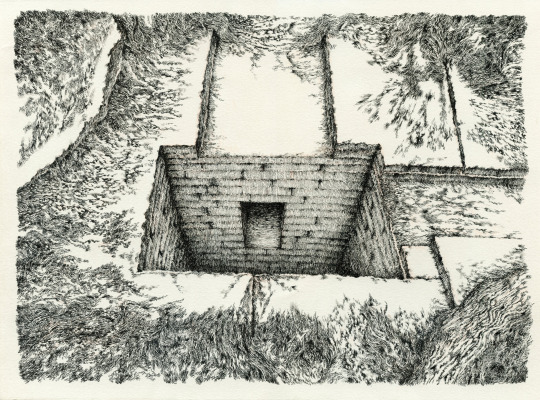

My most recently finished drawing. This one employs a perspectival view that's unusual for me. I hadn't thought of it, but I suppose the scale here is somewhat ambiguous: there could be brickwork in the pit or gigantic stonework. Up to how you want to see it.

#ink art#ink drawing#hole#subterranean#moss#architecture#organic architecture#new york artist#linework#detailed art#imaginary landscape#monochrome#monochromatic#grotesque

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rocky Landscape: Gorge with Ruins, 1830 by Karl Friedrich Lessing

#carl friedrich lessing#karl friedrich lessing#art#landscape#nordic#ruins#rhineland#germany#german#rocky#gorge#castle#romantic#romanticism#europe#european#nature#castles#history#imaginary#fanatasy#legends#myths

891 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tallying every single tree in the kingdom. Endangered South Asian sandalwood. British war to control the forests. European companies claim the ecosystem. Failure of the plantation. Until the twentieth century, the Empire couldn't figure out how to cultivate sandalwood because they didn't understand that the plant is actually a partial root parasite, so their monoculture approach of eliminating companion species was self-defeating. French perfumes and the creation of "Sandalwood City".

---

Selling at about $147,000 per metric ton, the aromatic heartwood of Indian sandalwood (S. album) is arguably [among] the most expensive wood in the world. Globally, 90 per cent of the world’s S. album comes from India [...]. And within India, around 70 per cent of S. album comes from the state of Karnataka [...] [and] the erstwhile Kingdom of Mysore. [...] [T]he species came to the brink of extinction. [...] [O]verexploitation led to the sandal tree's critical endangerment in 1974. [...]

---

Francis Buchanan’s 1807 A Journey from Madras through the Countries of Mysore, Canara and Malabar is one of the few European sources to offer insight into pre-colonial forest utilisation in the region. [...] Buchanan records [...] [the] tradition of only harvesting sandalwood once every dozen years may have been an effective local pre-colonial conservation measure. [...] Starting in 1786, Tipu Sultan [ruler of Mysore] stopped trading pepper, sandalwood and cardamom with the British. As a result, trade prospects for the company [East India Company] were looking so bleak that by November 1788, Lord Cornwallis suggested abandoning Tellicherry on the Malabar Coast and reducing Bombay’s status from a presidency to a factory. [...] One way to understand these wars is [...] [that] [t]hey were about economic conquest as much as any other kind of expansion, and sandalwood was one of Mysore’s most prized commodities. In 1799, at the Battle of Srirangapatna, Tipu Sultan was defeated. The kingdom of Mysore became a princely state within British India [...]. [T]he East India Company also immediately started paying the [new rulers] for the right to trade sandalwood.

British control over South Asia’s natural resources was reaching its peak and a sophisticated new imperial forest administration was being developed that sought to solidify state control of the sandalwood trade. In 1864, the extraction and disposal of sandalwood came under the jurisdiction of the Forest Department. [...] Colonial anxiety to maximise profits from sandalwood meant that a government agency was established specifically to oversee the sandalwood trade [...] and so began the government sandalwood depot or koti system. [...]

From the 1860s the [British] government briefly experimented with a survey tallying every sandal tree standing in Mysore [...].

Instead, an intricate system of classification was developed in an effort to maximise profits. By 1898, an 18-tiered sandalwood classification system was instituted, up from a 10-tier system a decade earlier; it seems this led to much confusion and was eventually reduced back to 12 tiers [...].

---

Meanwhile, private European companies also made significant inroads into Mysore territory at this time. By convincing the government to classify forests as ‘wastelands’, and arguing that Europeans would improves these tracts from their ‘semi-savage state’, starting in the 1860s vast areas were taken from local inhabitants and converted into private plantations for the ‘production of cardamom, pepper, coffee and sandalwood’.

---

Yet attempts to cultivate sandalwood on both forest department and privately owned plantations proved to be a dismal failure. There were [...] major problems facing sandalwood supply in the period before the twentieth century besides overexploitation and European monopoly. [...] Before the first quarter of the twentieth century European foresters simply could not figure out how to grow sandalwood trees effectively.

The main reason for this is that sandal is what is now known as a semi-parasite or root parasite; besides a main taproot that absorbs nutrients from the earth, the sandal tree grows parasitical roots (or haustoria) that derive sustenance from neighbouring brush and trees. [...] Dietrich Brandis, the man often regaled as the father of Indian forestry, reported being unaware of the [sole significant English-language scientific paper on sandalwood root parasitism] when he worked at Kew Gardens in London on South Asian ‘forest flora’ in 1872–73. Thus it was not until 1902 that the issue started to receive attention in the scientific community, when C.A. Barber, a government botanist in Madras [...] himself pointed out, 'no one seems to be at all sure whether the sandalwood is or is not a true parasite'.

Well into the early decades of twentieth century, silviculture of sandal proved a complete failure. The problem was the typical monoculture approach of tree farming in which all other species were removed and so the tree could not survive. [...]

The long wait time until maturity of the tree must also be considered. Only sandal heartwood and roots develop fragrance, and trees only begin developing fragrance in significant quantities after about thirty years. Not only did traders, who were typically just sailing through, not have the botanical know-how to replant the tree, but they almost certainly would not be there to see a return on their investments if they did. [...]

---

The main problem facing the sustainable harvest and continued survival of sandalwood in India [...] came from the advent of the sandalwood oil industry at the beginning of the twentieth century. During World War I, vast amounts of sandal were stockpiled in Mysore because perfumeries in France had stopped production and it had become illegal to export to German perfumeries. In 1915, a Government Sandalwood Oil Factory was built in Mysore. In 1917, it began distilling. [...] [S]andalwood production now ramped up immensely. It was at this time that Mysore came to be known as ‘the Sandalwood City’.

---

Text above by: Ezra Rashkow. "Perfumed the axe that laid it low: The endangerment of sandalwood in southern India." The Indian Economic and Social History Review, Volume 51 (2014), Issue 1, pages 41-70. First published online 10 March 2014. DOI: 10.1177/0019464613515533 [Bold emphasis and some paragraph breaks/contractions added by me. Italicized first paragraph/heading in this post added by me. Presented here for commentary, teaching, criticism purposes.]

#a lot more in full article specifically about#postindependence indian nationstates industrial extraction continues trend established by british imperial forestry management#and ALSO good stuff looking at infamous local extinctions of other endemic species of sandalwood in south pacific#that compares and contrasts why sandalwood survived in india while going extinct in south pacific almost immediately after european conques#abolition#ecology#imperial#colonial#landscape#indigenous#multispecies#tiger#tidalectics#archipelagic thinking#intimacies of four continents#carceral geography#geographic imaginaries#haunted

246 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thirsty Canyon, 2024

Mixed media: coffee and colour wax crayons

have a good one on your end*

#balluprojects#portugal#originalartwork#naturelovers#nature#art#mindscapes#landscapes#canyon#orange#artists on tumblr#landscape#imaginary#spaces#waiting#rainy season#illustrations#drawings#wax crayons#coffee#mixmedia#experiments#reactions

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Haley Hughes. Paradise 2, 2016.

oil on canvas

226 notes

·

View notes