#I’m not trying to be racist I’m only observing how the game itself uses skin tone

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

My Ballot for They Shoot Pictures, Don’t They?’s 25 Favourite Films Poll

The following is my ballot for They Shoot Pictures, Don’t They?’s poll for their readers’ 25 favourite films of all-time. It contains a dozen or so favourites, several compromises, and a handful of personally foundational texts.

Seven Chances (1925, Buster Keaton): It ain’t easy to only choose one Keaton. This is one of Keaton’s films with a racist blackface character, which gave me some reservations. Still, this is a solid contender as his funniest picture, and, more importantly, this is Buster as I love him the most. Keaton’s characters were always the most cerebral and lost, keen observers with no understanding. An inability to communicate one’s emotions drives the need to convert it into a physical experience; Keaton inevitably becomes the object that cannot be stopped. His full forced desperation and athleticism, he is a master of locomotion. Featuring the finalization of the chase gag, along with a generous serving of his brand of surreal.

City Lights (1931, Charles Chaplin): Comedically and emotionally devastating.

Trouble in Paradise (1932, Ernst Lubitsch): Lubtisch’s portrayal of Continental aristocracy on the cusp. Containing love, melancholy, desire, rivalry, loyalty, betrayal, criminals, and thieves-- all saved by his grace alone, achieving a rare bliss of comedy and romance. Normally, I’d say that, in a temporal world, perfection exists only as a process, but then how would I explain this?

La grande illusion (1937, Jean Renoir): In the best of Renoir’s films, I find a type of harmony I find lacking in the rest of the world.

La règle du jeu (1939, Jean Renoir): In making this list, I never doubted either of these Renoir films having a place. Now, trying to write about my list, I find myself becoming frustrated at not finding the words to explain why I chose them. I’ve never been a great communicator, and I doubt that’s Renoir’s fault. I think it’s best for me to move on before I start misplacing my frustrations with my inability to write onto the film itself.

How Green Was My Valley? (1941, John Ford): Possibly the greatest movie ever made under Hollywood’s Studio System, and perhaps the closest we’ll ever get to seeing what Hedy Lamarr might have seen in John Loder. More than any other actor, Sara Allgood carries this film, in her role as the matriarch of the Morgan household. This is chock full of great character actors and moments as you’d expect from Ford. It’s the magic of childhood, the safety of the womb, the cyclical nature of a town where nothing ever seems to change, and the devastation of entropy. I lost track of how many times I cried.

To Be or Not to Be (1942, Ernst Lubitsch): This is my choice for a comedy from the 1940s, despite stiff competition from Hellzapoppin’, and the 11 movies Preston Sturges released over the decade. I had the privilege of seeing this at my local Cinemateque with an introduction by Kevin McDonald. I was late, and the audience had already begun to talk back. He rolled, and we were soon laughing before the “projectionist” could hit ‘play’ on the Blu-Ray. My friend came later. It was a packed house, so we weren’t able to sit together. I enjoyed hearing the variances in people’s response*, and the timing of their laughter. Trying to pinpoint my friend’s laughter from the crowd, I couldn’t help but hear our host’s generous laughter throughout the film. What a joy it was for all of us to experience this film together. I guess I haven’t had a chance to share those other movies the way that I was with this one. *A nice change of pace, as this usually makes me self-conscious

Shadow of a Doubt (1943, Alfred Hitchcock): I find Hitchcock’s women’s pictures to be some of his richest texts. Besides which, any film asking me to sympathize with Theresa Wright already has a lot going for it. Alongside The Wrong Man as Hitchcock’s most tragic film.

Brief Encounter (1945, David Lean): My favourite romance, whatever that says about me. A passionate extramarital affair between Laura Jesson (Celia Johnson) and Dr. Alec Harvey (Trevor Howard), told in flashback. I don’t think I’ve ever seen this placed among noirs, but I think this could be an example of a women’s film noir. There’s a thick sense of transgression and fatalistic mise-en-scene, along with an inability to escape, which ends the film on an unconvincing return to safety. After the two lovers part for the final time, Johnson returns home. Her husband, Stanley Holloway, asks for nothing, and expresses gratitude for her return. However, for all of that loveliness, Johnson has learned that the world is far more fragile than she ever dreamt. The husband is portrayed as a bit childlike, and, coupled with the affably stiff upper-lipped nature of their marriage, Johnson is unable to confess what’s occurred, which only preserves her turmoil. Unable to consummate, sustain, or forsake her romance with Howard, she may find some refuge with her husband, but salvation eludes her.

Out of the Past (1947, Jacques Tourneur): RKO Pictures, film noir, Jacques Tourneur, and Robert Mitchum– These are a few of my favourite things. As a prude, I don’t care to admit that I love cigarette smoke in B&W pictures as much as I do, and it’s deployed here to its zenith, courtesy of Nicholas Musuraca’s cinematography. Daniel Mainwaring’s script, along with Tourneur and Mitchum, use underplay in order to create a heightened effect. Mitchum’s somnambulism grants his portrayal of Jeff Bailey an omniscient cool, which extends to his character’s bisexuality. There’s such delight in hearing Mitchum, one of the best voices in movies, deliver the film’s lyrical dialogue in his disaffected baritone.

The Big Heat (1953, Fritz Lang): Perhaps Lang’s most cynical film? The culmination of all his conspiracies. The law vs. criminals, no longer as separate from one another, but as sides of the same coin: the establishment. Sergeant Bannion (Glenn Ford) engages in total war against Lagana’s (Alexander Scourby) crime syndicate. Those caught in between end up as collateral damage, pawns in their game. Each dismantles the family unit, Lagana disposes of Bannion’s wife (Jocelyn Brando), and Bannion displaces his child, so that both sides can carry on unfettered. The happy ending finds Bannion happily back at work in the homicide department, where they’re informed of a grisly murder. Oh boy, here we go again! Gloria Grahame, a sister under the mink, reigns as my favourite actress in all of film noir.

The Sun Shines Bright (1953, John Ford): It’s not easy to film a miracle, a feat for which I’d pair this with Carl Th. Dreyer’s penultimate film, Ordet. Speaking of Dreyer, if you have 15 minutes to spare, here’s a great video of Jonathan Rosenbaum discussing this movie alongside Dreyer’s final film, Gertrud. The responsibilities and limitations of society. Communities are built through sacrifice, as we give of ourselves, which accounts for the film’s sometimes funereal tone. One’s resting spot as the place to make a stand, but what good is taking a stand if it doesn’t lead anywhere? Our redemption lies not in preserving ourselves, but in guiding the world to a place that no longer needs us. Thus, not a dying world to save, but an understanding that we must pass in order to bring about renewal. Funerals become parades, and parades become funerals, as we walk the strait and narrow path between tradition and progress. Don’t take a stand while the world marches on, but lead us into thy rest.

The 5,000 Fingers of Dr. T (1953, Roy Rowland): This is a musical written and designed by Dr. Seuss, which is to say that I think you oughta see it. Still, it’s hard to justify why I chose this over The Band Wagon. I’d probably better enjoy watching The Band Wagon, which I’d wager is Hollywood’s greatest musical, but there’s something about The 5,000 Fingers of Dr. T that gets under my skin. I saw it on television when I was very young. Old enough to remember seeing it, but too young to remember more than three details: twins joined at the beard, the nightmare-inducing elevator operator, and a large piano requiring an exponential amount of fingers. This forgotten foundation, along with its Seussian imagery, grants the film a dreamlike feeling. Just as every good boy deserves fudge, every Hans Conried deserves a role like the one he has here, playing the titular Dr. T.

The Night of the Hunter (1955, Charles Laughton): A kid’s film featuring the personification of evil, not in Mitchum’s portrayal of the preacher Harry Powell, but in Evelyn Varden’s Icey Spoon. This movie is so full of indelible images that I sometimes forget LOVE/HATE tattooed on Powell’s knuckles. There’s a dreadful unease from the inability to fully save or preserve Ben & Pearl within a society whose systems turn on them so easily. Their safety is drawn and quartered at every turn, and so Ben & Pearl flee society, finding a guardian out yonder. Still, there’s a limitation to their newfound guardian’s protection. Their angel and their demon sing in harmony; evil becomes instructive to the children’s growth. It’s a hard world for little things, but there is hope. Mrs. Cooper (Lillian Gish) manages to find her redemption in protecting these children while she can. Perhaps we need them as much as they need us. This was Charles Laughton’s only film as a director, as well as the final of James Agee’s two films as a screenwriter. It isn’t right.

Sweet Smell of Success (1957, Alexander Mackendrick): This is my favourite film noir, possibly the nastiest as well. Of course, I cackle throughout the entire picture. Burt Lancaster and Tony Curtis at their bests; the tension between a malevolent god and his jester/would-be pretender played as flirtation, conducting assassinations as though they were composing poetry. Shot on location in New York by James Wong Howe, giving us a view of Babel from the gutters up. Also, I’m just a big ol’ softy for Emile Meyer, who plays Lt. Kello.

Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter? (1957, Frank Tashlin): As I see it, this is the best sex comedy of the ‘50s and ‘60s. Tashlin previously worked at Termite Terrace, making Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies, and did a brief stop making Screen Gem cartoons over at Columbia in the middle. After having brought feature film techniques to his cartoons, he brought cartoon imagery into his live-action films. This is a vehicle for Jayne Mansfield, who may have been the most cartoonish of the era’s blonde bombshells, and so it is a happy marriage indeed.

Playtime (1967, Jacques Tati): This is cinema. Ah! Tati, Ah! Modernity

Out 1: noli me tangere (1971, Jacques Rivette & Suzanne Schiffman): Rivette’s movies feel alive in a way that I haven’t found anywhere else. The films I’ve seen are about conspiracy, games, and the development of theatre troupes: things that exist only in our minds, and are dependant on our cooperation with others. Things get so twisted that you wonder how they’ll ever untie it all, only for the shared illusions to be revealed as a complex series of false knots. I broke my rule with this film, in choosing a film that I’ve only seen once. I didn’t make the time to revisit this or Céline et Julie vont en bateau, my other favourite Rivette film, so I went with the larger labyrinth to lose myself in.

F for Fake (1973, Orson Welles): This is Orson Welles’s most playful film. I love Welles, the personality, almost as much as I love Welles, the director, so I chose a movie that features both.

Mikey and Nicky (1976, Elaine May): Perhaps the most tense and dark comedy I’ve ever seen. May reaches her highest levels of drama here, and does so without any cost to her usual standards for humour.

It’s a Wonderful Life (1946, Frank Capra): I wasn’t sure about including this, given that it’s not even my favourite James Stewart Christmas movie, but what can I do? It’s a Wonderful Life is an institution in my family, we’ve watched this every Christmas Eve since I was grade 6. There was a year or two in the early ‘10s where we might have missed it, but, otherwise, we’ve been devout. This is also one of four sources that laid the foundation for my love of movies, and, in particular, older movies. I hope to continue to watch this every year. It just wouldn’t be Christmas. Growing up, my brothers and I used to be allowed to open one gift the night of Christmas Eve, which evolved into my brothers and I exchanging our gifts for each other. The first year my brother’s and I exchanged gifts, we happened upon CBC playing It’s a Wonderful Life in a 3-hour timeslot. Filling in the gaps of my memory with ego, I’d say that I instigated our watching it. I was always the biggest sucker for holiday specials, as well as being the most drawn to B&W. It was an instant hit with all of us, and so two traditions were born that night. For those curious as to what year this took place, I gave my oldest brother a 3 Doors Down CD. My older brother got me the Beast Wars transmetal Terrosaur figure. And. It. Freakin’. Ruled. CBC continued to air It’s a Wonderful Life every Christmas Eve, and we continued to tune in. My brothers and I continued to exchange gifts on Christmas Eve for about another decade, but now my family has a better Christmas Eve tradition to pair with our holiday movie: Chinese food, and, less dogmatically, vegetable samosas. Leftovers become brunch. We’ve watched the movie, I think, twenty times now, which includes one viewing of the unfortunate colourized version, and once in theatres. It’s a great movie to come back to each year. There are lots of little moments, lines, and details to zero in on, and each year I get to internally test and brag to myself about naming and recognizing the various character actors and bit players that pop up. Still, I sometimes find myself resisting its charms. A couple of years ago, my view of Frank Capra changed. I no longer saw him as the director I had previously thought him to be*. I wondered whether this movie stood on its own merits, or if I was holding onto it for sentimental reasons. I have since settled on this film being a genuine classic. Another source of resistance is that I’ve never watched this on its own, there’s a lack of an individual foundation to my relationship with the film. I’m so accustomed to viewing films on my own, I think there’s a relief in a taking a private experience, and having it succeed in a public forum. The two support each other, which is part of why a couple of films ended up on this list. However, when it’s a film I’ve only seen in the company of others, I become suspicious of my experience. I believe in the power of cinema when it’s to my benefit, only to doubt it when I fear that it has the power betray me. I guess that I lack faith. *The director I once thought Frank Capra was, I now find Leo McCarey to be.

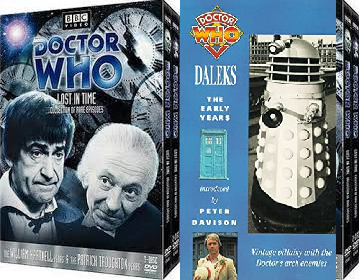

Doctor Who: The Lost in Time Collection (1963-69, various): This was a last minute decision that ended on a mistake. I ought to have chosen Daleks: The Early Years instead, which has the proper framing of a retrospective documentary. Daleks: The Early Years is a VHS release hosted by Peter Davison, featuring interviews with key people from ‘60s Dalek stories, cannibalizing clips from Dalekmania (another documentary on Daleks in the ‘60s), and orphan episodes and snippets from otherwise lost ‘60s Dalek serials. It’s also one of the VHS tapes that I grew up with, and my introduction to the fact that, at the time, over 100 episodes of ‘60s Doctor Who were missing and presumed lost. This was my introduction to the concept of lost media. Since then, a further 12 episodes have been found, and the number of missing episodes has dropped to 97. Instead, I chose The Lost in Time Collection, which is a 3-disc collection of orphan episodes and surviving clips from otherwise missing ‘60s serials, not actually a feature in itself. It’s a really nice sampling of the Doctor Who’s best era, and the episodes and clips are sometimes more interesting without the rest of their serial for context. While I didn’t get this collection until I was an adult, I had managed to see most or all of its contents growing up, mostly on various VHS compilations, as well as some clips online. As the deadline for submissions approached, I chose the one I enjoy more, rather than the one that first changed me. I suspect that Doctor Who was the first work of science-fiction that I got into, as it predates me in our household. My brothers and my getting into Transformers predates my memory, but it does not predate my being around. Doctor Who also served as my first exposure to B&W viewing. I was really into science-fiction growing up, and the genre was really my first interest in older films. The interest didn’t really bridge its way from my youth into my present. Heck, I wasn’t even particularly a movie person until into my twenties. In early adulthood, after fading for a bit, my fondness for science-fiction was more directed towards video games and books. So while it didn’t lead into my love of film and B&W, it laid a lot of the groundwork for what I’d eventually come to love. My oldest brother remembers staying up late with our parents to watch Doctor Who, and my older brother has memories of trying to stay up with them, but it was no longer airing on any of the stations we had by the time I was kicking. Loved, but unseen, it developed a sort of mythic reputation in my young mind. Over the years, we managed to see a bunch of serials on VHS through our local library system, and we eventually got 5 VHS releases of our own before the decade ended. We got a book, The Doctor Who Yearbook, which had listings and synopsises of every serial ever made. The classic Doctor Who series lasted 26 seasons, consisting of 153 serials, and just shy of 700 episodes. No matter how many episodes of Doctor Who I managed to see when I was growing up, it was only ever the tip of the iceberg. My younger self liked daydreaming about all of the adventures, planets, aliens, robots, and monsters, but that would begin to dissipate with age. While I loved Star Wars for the many of the same reasons as I did Doctor Who, the advent of more Star Wars wasn’t all that fulfilling, with Episode I: Racer for the N64 PC as a noted exception. More than the fact that I was caught up in the cultural backlash against George Lucas, the lack of a well defined characters and society in the original trilogy was a virtue. The toys and books really capitalized on this. I was the kid that wanted to know every weirdo and background character’s life story. I was such a mark. The more movies they made that added to the lore, the smaller their galaxy seemed to be, in opposition to an expanded universe. Each piece promising to add to the larger picture only seemed to reveal a smaller whole. More movies telling the same stories with different versions of the same characters. A galaxy that once seemed so vast now revealed to be comprised of maybe two dozen people, many of which are related or connected to each other in some tired and unnecessary way. Eventually, I got really into Jonathan Rosenbaum, and began to project my ego all over his preferences, to which Star Wars became a victim. I gave up on the series after sitting through a showing of Episode VII. Fires subside, and, these days, I’m mostly indifferent towards the series. Undergraduates can be a bit much, y’know? While the new Doctor Who series also fell out of favour with me, it was easier for me to divorce it from the original series. Having seen the series only in disparate pieces, rather than a linear narrative may have helped. I have no illusions that the original series is anything more than a silly kid’s show that mostly takes place in corridors, which is a fine thing to be. It’s enough to be a delight. The deceit of nostalgia is that I can return to these works I once loved with the same feelings and wonder that I had as a child. While I remain fond of Doctor Who, the whole of a serial is often less than the sum of its parts. After all, being a serial, half of the adventure is meant to take place in your head during the week between episodes. It’s the opposite of binge-watch material. It’s hard to commit to working your way through such a bulky series at a deliberately slow pace. Besides, even spacing the episodes out some, it’s still not going to capture my mind the way it would when I was a child. The virtue of the Lost in Time Collection is that you’re never seeing a serial as a whole, only as individual pieces. The collection consists of 18 complete episodes from 12 serials, with clips and bits from an additional 10 serials. Only one serial has more than two episodes featured, The Daleks’ Master Plan, a 12-part epic, which has its 3 known surviving episodes on the set. Freed from the responsibilities of being part of a larger story, you get to enjoy the pleasures of each episode as its own entity. Charm exists outside of context, and what may have been stretched and strained over half a dozen episodes can easily be sustained in the single episode or two that remains. A piece of Starburst may not keep its flavour any longer than a piece of Hubba Bubba, but at least it has the decency not to overstay its welcome. The less that remains of a serial, the more interesting it becomes. For some serials, the only surviving clips are the scenes that were cut by censors, and so you’re only seeing the juiciest bits. Protected by obscurity, just as recording in B&W protected this era of the series against its lack of budget, the childlike sense of wonder remains. Any missing serial could have been great. We lack evidence to prove otherwise. What little remains from these serials is enough to imagine what may have been, and it’s easy to give the benefit of the doubt to an old friend. No longer just a science-fiction adventure, the series has grown into a larger and more engaging adventure in film & television preservation. Thanks to its cultural status and following, questions as to how these stories were lost, why years of episodes were junked, how they were returned, in which disparate places were episodes found, who has been hunting for them, what were their methods, to what lengths did they go, what places remain to be searched, what remains to be found, what’s trapped in the hands of private collectors, and what has been lost forever have all been thoroughly explored, though some answers continue to elude us. For those interested, Youtuber Josh Snares has an extensive series of videos that breaks down many of these questions as best as one can with what’s publicly known, and, despite being on yotube, I don’t think he’s annoying. Doctor Who best represents my film lover’s sense of discovery, combining the joys of hearing about a film that piques my interest, trying to track a film down, discovering or rediscovering a new favourite, learning about film history, and the efforts of film preservation. Hearing about films I’d like to see can be nearly as rewarding as actually watching the films themselves. The more that I see, the more there is that I’d like to see. The harder something is to find, the more interesting it can become. Film is a physical object, so there is a battle against time for us to discover, recover, restore, and preserve works before they’re lost to time. The good news is that many efforts are being undertaken, both by professionals and by amateurs. The advent of crowdfunding has really helped to create more opportunities for completing these endeavours. Following an Indiegogo campaign, Netflix stepped in and completed Orson Welles’s The Other Side of the Wind. Many of Marion Davies’s silent films have been restored in recent years. Thanks to the efforts of Ben Model and his team, I will soon have the pleasure of seeing eight Edward Everett Horton shorts that haven’t been in circulation since the silent era. Steve Stanchfield (Thunderbean), Jerry Beck (Cartoon Research), Tommy Stathes (Cartoons On Film), and their cohorts are doing God’s work in finding and restoring old cartoons, and giving them an audience once more. I don’t think there’s ever been a more exciting time to be so out of touch.

The Muppet Movie (1979, James Frawley): The Muppets’ movies were a staple of our household growing up, and this ranks alongside The Great Muppet Caper as the best of them. This movie has a very self-aware humour to it, exemplified by the introduction. The camera wanders through a studio backlot, following a car carrying Statler & Waldorf, who provide us with the first dialogue of the film, announcing their intent to heckle the film. Inside, the Muppets are waiting for a private screening of The Muppet Movie to begin. It’s a disaster. A monster tears out one of the seats, the visibly deranged Crazy Harry blows up another, people are dancing in the aisles, and chickens are flying about. Objects being thrown include, but are not limited to, popcorn, Lew Zealand’s boomerang fish, and paper airplanes. A full-sized Muppet looms in the background, a giant colourful bird with enormous unblinking eyes, leaning a bit from side to side. An acknowledgement that somebody has let the animals in charge of the zoo. Still, a coziness remains amidst all of the chaos. Kermit attempts to introduce the movie to his peers, the lights go down, and he takes his seat. The movie opens in the heavens, where the credits and a rainbow appear. It clears onto a long, long shot of a swamp, slowly zooming in to reveal a frog on a log, playing a banjo, singing Paul Williams and Kenneth Ascher’s The Rainbow Connection. We’re taken away. One of the most vital aspects of the Muppets is that they exist in our world, something that gets lost in their 90’s trend of literary adaptations. An entire world of Muppets isn’t much of a utopian vision, but the idea that these animals, monsters, and whatevers belong in society alongside ‘real’ people is. This trend was part of a larger regression throughout the years with the Muppets. What began as a self-aware humour turned into a self-depreciating humour, and, eventually, a self-loathing humour. The Muppets used to take on the world, but, in later years, they seemed unable to dream of anything more than getting back together once more, so that they could reaffirm their lack of success. Bring them back to life so they can take one more dying breath. This Muppet movie is filled with celebrity cameos, in part a tribute to their variety show, as well as to the vaudevillian origins of most of their shtick. Here, the cameos serve the Muppets. Later, the Muppets would take a backseat, and become vehicles for others, not even allowed to star in their own movies. I wish they were given better opportunities to shine. As good as this film is, I have to admit that this film’s treatment of Miss Piggy is embarrassingly sexist. While they don’t look like Presbyterians to me, at their best, I think the Muppets have almost as much hope to offer as any religion.

Transformers: The Movie (1986, Nelson Shin): Watching this movie gives me the feeling I always hope that I’ll feel whenever I’ve bought concert tickets. I don’t watch this so much as I sing along to it. I even knew Vince DiCola’s score down to a ‘T’. With all due respect to Storefront Hitchcock, this is my personal Stop Making Sense.

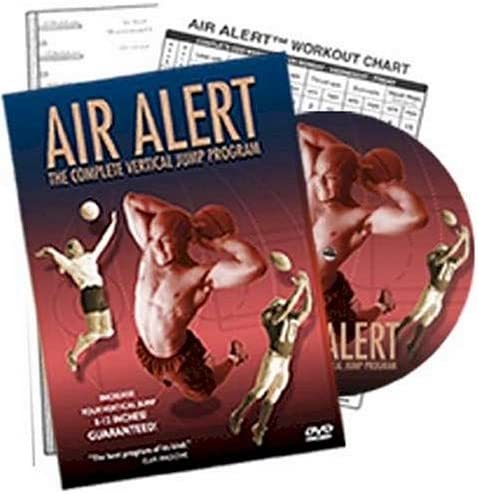

Air Alert V. 4 (late 2000’s, TMT Sports): First, and most importantly, I do not recommend Air Alert nor any other paid for vertical jump program. I cannot stress that enough. They’re not designed by people who really know what they’re doing, the marketing is predatory, they’re unjustly hard on your joints, and they’re methods are not in conjunction with their promises of wild vertical gains. While I hope to stop finding that people have also done Air Alert, I immediately feel a strong kinship with those I learn have also been misled. Air Alert is a 15-week vertical jump program that makes the dubious promises of adding 8-14 inches to yer vertical leap to everyone, regardless of their current physical condition. It promises to add explosiveness to yer hops, but its means are an exponentially increasing amount of jump exercise repetitions. This is to say that, in practice, Air Alert actually builds jumping endurance, which teaches yer muscles to conserve energy, rather than to expend it in an explosive manner. Like all jump programs, it also fails to address that much of your jumping’s height comes from a combination of your core and upper body strength, as well as technique. The version I got also came with an advertised-as-new Air Alert Advanced, a further 6 weeks of yet more intensive exercise routine to add another 3-6 inches to yer leap. I did the 15 weeks of Air Alert, and, like everybody else I’ve known, I got 2-3 inches added to my vertical. After the recovery week suggested following completion of the program, I tried dunking at the church. You had better believe that I told my dad to bring his digital camera, ’cause this was gonna be a big deal. Being able to dunk was surely going to usher in a whole new era in my life. Now, I had been wrong about these sorts of things before. I had become skinny, I got a couple of nice shirts, I listened to what I though was the right unpopular music, and I had stolen some jokes, but my life largely remained the same. It seemed as though my life couldn’t be redeemed by vanity and trivialities, J still wasn’t dating me, but this would be so much more. This was dunking. This was going to be different. We went to the church, and I had the same problems as before. I could get high enough, but I couldn’t throw down. The further you extend a limb from your core, the less strength it has at its disposal. I had little upper-body strength to begin with, and, fully extended, my hand is pretty far from my body. I’d always lose the ball on the way up, or lose height putting more of my strength onto the ball. Legs can only take you so far. At my best, I’ve brought the ball to the rim, lost it, and, thanks to momentum, had the ball go off of the backboard and in. A lay-up isn’t a dunk. My knees have been crunchy ever since. After a further month of letting my joints recover, I tried my hand at Air Alert Advanced. After the first week, which consisted of 3 days of 2000 individual jumps, some of my friends reunited to play soccer at our old high school. I was proud to see that the goals we had rescued were still on the field. However, I found that my joints were so worn down that I could only run at a steady pace in a straight line. Turning, accelerating, and decelerating were all, sadly, out of the picture. I decided not to continue onto the subsequent weeks. I was still a fatuous pauper, single, and working at a shoe store while friends had gone on to do other things, so what did I manage to accomplish? Well, for starters, I gained some athletic ability for the first time in my life, which was neat. I gained a lot of leg strength, endurance, and quickness, as well as the previously mentioned 2-3 inches to my vert, all of which I treasured. Despite being the skinniest guy on the court, my legs were strong enough to anchor me in the key, and contend with guys up to double my weight. I went from being a guy who showed up to Dunkball, to becoming a guy that people wanted on their team. While others got tired throughout the night, slowly losing their vertical, I managed to jump just as frequently and just as high in my last game of the night as I could during my first. As both the tallest and the lankiest guy at Dunkball, my height advantage now increased in the air. I’d let people box me out, only to jump and reach over them. I felt so free. I was, and remain, Dunkball’s most improved player. Of course, it helps to have the advantage of having started out lower than everybody else. Once, somebody brought a friend who was taller than me. It was awful. As for dunking? Well, I could dunk small balls at the church, if I could close my hand on them. I managed to dunk a flat soccer ball on an outdoor net at a school yard once, but I never verified its height. I could dunk at the Academy chapel with the rim fully raised, though that rim sags in the front, so I’m guessing that rim was about 9’10”. Still, that won me a game of H-O-R-S-E or two. Sometimes, when warming up for Dunkball, someone would instigate a dunk competition, and I managed to develop a trademark dunk which nobody could replicate or stomach: the underhanded dunk. Norm was the only person not to loathe it, bless his heart. While I never managed to dunk on a proper 10’ net, I was able to goaltend, which has no use outside of being a dick to a friend. I was smarmy enough to do it once. Even at Dunkball, I never became much of a dunker, except on turnovers or tip-ins, or unless I had a guard who could do the work of setting me up. I’m more opportunistic than aggressive, besides, who am I going to beat off of the dribble? On my worst nights, I was still a tall guy who could jump, so I always drew the interest of a defender. I’ve always preferred defence to offence, and my favourite offensive play is to box out their post-player, either to be in a better position to rebound, or in order to prevent them from goaltending. Defence is where Air Alert made the most difference for me. They either had to box me out in order to stop me from goaltending, or try banking it in. I could sit low enough to the ground to defend outside players without losing speed. With a lower net, some players didn’t arc their shots as much, allowing me to swat them away with ease. There was nothing better than blocking a dunk. Some people took it personally, and would try coming at you on the next play; we all loved blocking Joseph. Still, the best was blocking Norm’s dunks, even if it meant landing on my back. It was summertime, the final game of the night, with uneven teams and lopsided match-ups, but, somehow, it’s neck and neck. Not only are we still in it, we’ve had the lead. Will is shooting, Nathan is hustling, and I’m blocking everything. My greatest defensive game ends prematurely after I block one of Norm’s dunks, landing horizontally, with all of my weight squarely on my tailbone and elbows. I call it a night, and, in the morning, learned that we had lost immediately after I left. At this point, I had memorized Air Alert’s number of sets and routines, and so I lent the DVD to Graham. He promised to return it soon. This was in 2010. I learned how to juggle that August, but that didn’t save me either. I kept up my jumping exercises, doing week 4 as maintenance, losing consistency once I started university that fall. Dunkball slowly lost consistency, too, and so I eventually took up the reigns of organizing it. People changed wards, got married, moved, and started families. It was hard to motivate people to come out without a guarantee. At some point, I became one of the veterans. As Dunkball continued to lose consistency, and as I went through occasional bouts of burn-out withorganizing things, Dunkball changed from being year-round into seasons, and, later, patches, of activity. The benefit of being the one to organize Dunkball is that it allowed me to filter out the jerks between patches of activity. There aren’t a ton of rules, you can make a pass off the wall, you can charge, you can play it in the hall, and goaltending is a way of life, but life is too long to spend it with people who can’t play sports without yelling. We weren’t as athletic as we once were, but the new players were generally pretty skinny, so we were still able to push them around. I stopped buying bus passes after my first year of university, which helped me to maintain most of my leg strength. While I was in university, I managed to keep most of my vertical, but my confidence became precarious, which affected my intensity. I wasn’t soaking through my shirts anymore, I started to let people push me around. After I dropped out of university, I grew into a much more sedentary lifestyle. The leg strength I had used to define myself diminished. I’ve had a really hard coping with that. At times, the prospect of playing Dunkball felt more embarrassing than motivating. I felt lost out on the court. I didn’t feel strong enough to bump around in the key, and I felt sluggish trying to play on the outside. Still, I had now been around long enough that I was able to lead a team, if necessary. I’d hide from my refuge until I felt strong enough to return. Volunteering and winter each got me walking again. Collin organized a soccer team the summer before the pandemic, which got me running and jumping again. I felt more determined, and began to feel better. No longer trapped by where I was, or where I felt I should have been, I was content with making progress. I think that I handled the early months of the pandemic better than most people. With our usual routines in disarray, I stumbled out of the feedback loop I was caught in. Finding some self-compassion and focus, I created structure to my quarantine in order to work on some goals. I was going to come out of the quarantine dunking. I was joking this time, but I need to dream about something while exercising. Otherwise, I’m just jumping in place, staring at the door. I went through weeks 1-7 of Air Alert, ending with the rest week that marks the halfway point. After which, I returned to doing week 4 to maintain strength. With churches closed, activities cancelled, and others on lockdown, I started secretly meeting Nik on Saturdays to shoot the ball around. This was back when we were allowed to keep small circles of contacts. The benefit of having keys. The only downside was that the building didn’t have any air circulation outside of facilities management’s offices. Regarding the pandemic, our city still didn’t have any cases of community transmission. Two of us shooting the ball around became three, and soon we were playing 2-on-2. Dunkball was back, baby! Sans the titular Dunkball, which had gone missing, stolen by missionaries. I knew that it was only a matter of time before they got rid of the Academy chapel, so I was really motivated to play as much as we could while it was still safe. It took us a little bit before we managed to get six players out on the same day, and we still ended up playing 2’s some nights. We weren’t getting many guys out, but we always had good games. Everyone who came out hustled and was a solid atmosphere guy. We’d mostly play best-of-5 or 7 game series, maybe switching teams up for a final game or two. The series managed to stay pretty tight, with nobody ever reaching a dynasty. Facilities management leaves the building at 5:30, and, with nobody else around, our secret combination was free to schedule Dunkball whenever we pleased. We were playing twice some weeks. We were able to accommodate people’s schedule. Marvin, my favourite teammate, was able to come out. I hadn’t been able to play with him in years. A high percentage of our small group of players were relatively new to the game. It was really exciting to see them develop, even if Jason blocked me that one time. I had found my place again, having regained some of my leg strength and quickness. My core and upper-body strength, elusive at the best of times, had become memories, but I worked around that. My game is mostly designed with those absences in mind anyways. Consequently, my play became much more lateral, rather than vertical, after the 4th and, later, 5th game, as Collin noted. I also managed a new trick or two, like learning to bait people into banking their shot, and then blocking it off of the backboard for a quick turnover. My intensity was up, or at least the A/C was down. I was soaking through my shirts again, and I was happy. It was a hot and humid summer. I missed Jason’s birthday, so I brought some blackout chocolate banana bread to celebrate. As it turns out, a thick moist cake is not refreshing when you’re exhausted and sitting around in a hot and stuffy room you’ve spent the past 2-3 hours further heating up with yer friends. Collin became the MVP the following week when he brought a box of freezies with him. All my life, I had never seen their true worth or potential. I took them for granted in my youth, and turned my nose up at them as I grew older. Now I understood. I had Dunkball, I had friendly players who responded when I tried organizing things, we had freezies, and, as the Ward Clerk, I had convinced my Bishop that we should buy a new ball (despite the fact that playing at the Church was still verboten.) I was grateful, but I still longed for a day where we had more than 4-6 players, so that we could have subs between games. It’s nice to be able to switch up teams between games, rather than trying to push Arles all night. It’s even nicer to sit down every once in a while, especially after failing to push Arles around. Our province was still fairly safe, but that was beginning to change. Two regulars had at risk family members, and we began seeing community transmission. I planned to end what was to be the penultimate season of Dunkball after Labour Day. I was concerned what would happen once the school year started. Before then, we had eight* people come out to Dunkball one morning. Four pairs of family members, in fact. This gave us rotations between games, and a variety of playing styles, leading to more interesting match-ups and dynamics. Whoever loses would get to take a break; excitement was in the air! I questioned Collin’s choice of shoes. He reminded me that I’m solely responsible for their condition. I lend Collin my shoes. He likes the shoes, and I like his freezies. *the ideal amount is 8-9 people Shoot for teams: Graham, Collin, and I hit our shots. Collin has speed, Graham has range and strength, I have the height, and we all rebound. We win the first game easily, manage to survive the second, and win our third. Dynasty! Shoot for teams again, and I’m back on the floor with David and Marvin. David anchors the key, allowing me to cheat on defence, while Marvin generates offence and creates mismatches. We all defend. Three more wins, and it’s another dynasty! Marvin and I sit this time, and watch as Jacob (handles), Graham, and Jason (positioning) steal the game. Marvin and I go back on with Limhi, a guard heavy team playing an post-player’s game. They shoot and pass, drawing out the defence, while I set picks, prevent goaltending, and try to clean up on the boards. They cover the outside, while I guard the inside. When the other team goes to the inside, I make their post-player turn away from the net, where either Marvin or Limhi, cheating off of their man, are waiting to strip them of the ball. We win the first game, taking back the floor. They carry me through the second. Last game of the day, and the other team starts to fall apart. As per tradition, we extend the game, but only to to 15, because only Graham and I want to play to 21. We stumble as they regroup, but Jacob gets frustrated, and their chemistry falters. I assume that I’m to blame, become self-conscious, and begin calling fouls on myself whenever I make any contact with the other team. Of course, this happens on every play, because I’m trying to box out my brother. I get some weird looks as David sighs, he just wants it to be over. I get a clean stop, Limhi scores, and the day ends on a third dynasty. I remain undefeated. Freezies for everyone! That was the third to last time we played Dunkball. We had another night with six players, and ended the season with a morning of playing 2-on-2, after which we ran out of freezies. I was optimistic that we’d be back playing sometime in the New Year. We barely registered a first wave of the pandemic, but restrictions ended prematurely, and school started back up. Cases kept climbing. I was scared in October, but that was only the beginning. When we first started playing Dunkball that summer, our province was first in the country. By Christmas, we had become the worst. We began to curb the number of new cases, but restrictions were eased before hospitals finished dealing with the second wave. In May, we began transferring patients to other provinces. For some reason, the plan is to reopen in July. For some reason, a duo tried organizing ball in March. I declined. Our congregation was changing buildings, so Nik and I went over to grab some stuff. I found that our Dunkball had gone missing again, but I found the original Dunkball, which hasn’t held air since 2015, and brought it home. In April, facilities management began clearing out the Academy chapel, in anticipation of listing the building for sale. They didn’t inform our Bishop until later that week. He went over to pack anything worth keeping, only to have found that they had already junked everything belonging to our congregation, as well everything belonging to the Yazidi community group that had been meeting there prior to the pandemic. I don’t know the building’s current status. Nik and I kept our keys in the hopes of playing again, but it’s unlikely that things will be safe to go back to normal in time. Dunkball exists as a time and a place: Thursday nights after Institute class at Academy. Last fall, they moved institute classes over to the stake centre. The Academy building is being sold now, and Dunkball is over as we know it. As I previously mentioned, I lent Graham, the Gordie Howe of Dunkball, my Air Alert DVD and booklet back in 2010. For the past ten years now, he has meant to return it, only for it to slip his mind. I usually forget about it, myself, only for him to remind me when he apologizes. In the moment, I sorta feel guilty that he worries about it. I mean, it’s fine, I don’t need it. He’s put it on his desk, he’s placed it by the door, and though he’s either seen me or a member of my family at least once a week for the past decade, my copy of Air Alert still hasn’t made its way back to me. I’m not even sure that I want it back, but I appreciate his sincerity. It’s become tradition for him to maintain this false tension between us. At this point, I’d hate to see it go. What if this tension is what’s sustained our friendship throughout all these years? What if Graham’s only been coming out to Dunkball because he feels guilty? I won’t see him at Dunkball anymore, and, as of this week, he won’t be seeing me at church anymore. It’s things like this that keep us alive. I hope that Graham never returns my copy of Air Alert, but I hope that he always tries. ”There is no end to matter, There is no end to space, There is no end to Dunkball, There is no end to race.” - If You Could Hie to Kolob Dunkball, by W.W. Phelps.

I could have gone on about my legs, honestly. Now, I only included those formative texts that I’m willing to admit are still a part of me. I did not include those works whose influences I feel that I have repented of, which is why the 1967 Patterson-Gimlin footage of Bigfoot from Bluff Creek, California, The Weezer Video Capture Device, Newsies, The Ultimate Showdown of Ultimate Destiny, nor anything related to Dorm Life or MST3K are not included on my ballot. In any case, I’m sorry not to have found room for Johnny Guitar.

#buster keaton#seven chances#city lights#trouble in paradise#ernst lubitsch#la grande illusion#grand illusion#la regle du jeu#the rules of the game#how green was my valley?#john ford#Shadow of a doubt#to be or not to be#brief encounter#out of the past#the big heat#the sun shines bright#the 5000 fingers of dr. t#the night of the hunter#will success spoil rock hunter?#sweet smell of success#playtime#f for fake#mikey and nicky#it's a wonderful life#Daleks: the early years#Lost in Time Collection#Transformers: the movie#The Muppet Movie#air alert

10 notes

·

View notes

Note

Who do you think is more unknowable and eldritch: The Radiance or The Pale King?

With respect, I’m about to hijack this question, but you’ve activated my trap card. (I will drop a follow-up post that is actually Hollow Knight meta, though, since you are asking for that)

To be a bit less flippant about it: I have a lot of emotions about unknowable and eldritch. Overwhelmingly they tangle together with my feelings on normal.

I don’t think that these are useful terms to use the way that we often use them.

Let’s take a bit of a history walk.

The concept of the eldritch is often conflated very closely with the concept of the lovecraftian horror- established, of course, by Howard Phillips Lovecraft. Lovecraft illustrated in lavish detail the idea of things that are literally unknowable- that to try and hold them in our mind, to try and make sense of them, will destroy us. And that these things will inevitably encroach, move closer into us, and we will end, we will be ended and destroyed because these things will come into our minds, into our lives, and tear them apart for the irreconcilability.

This is what a lovecraftian horror means: it is something that we cannot reconcile with ourselves in any way.

Here is the important, vital thing about Howard Phillips Lovecraft:

He was a horribly racist man.

This is vital.

Because here’s the thing that I resent about a lovecraftian horror: it is not horror. We hear about “incomprehensible eldritch beings” all the time in games and stories.

How do they act?

They are almost invariably hostile. They come after you. They’re here to destroy you.

This is not horror.

This is a reassurance.

Because we are put in the position of someone who destroys that incomprehensible being. We are definitely never put in a position where our lack of context hampers us. They are incomprehensible because they do not need to be comprehended. We don’t have to think about them. We don’t have to think about their feelings or ever try to understand because they don’t need to be understood. And, yet, we understand enough to say for sure that they are bad. They are bad, but we don’t understand how to talk to them. We don’t understand how they’re thinking. But we know they’re bad.

In this way, Lovecraft has designed a beautiful, perfect system of the world specifically for bigots. Because if you are bigoted, you are forced eventually to reconcile with the fact that your models of humanity are ignorant. That people, shockingly, remain people, no matter their background, spoken language, genetics, physiology, disability, or neurodivergence. That if I forced a white man from New York onto a deserted island with his only company being an aborigines man from Australia, without any spoken language between them and few experiences in common, unless one of them actively ended the situation with violence, they would come to understand each other, and have qualities in common.

Incomprehensible eldritch horror does not exist. It is rooted in a feigned weakness of the human mind, that was dreamed, in part, by a white bigot who was terrified of anything unlike him, and terrified especially that he would see ignorance and selfishness in the pedestal he created to elevate himself and others he thought of as worthy peers above all other kinds of human being.

Here is the reason this matters to me so much: I am not, in fact, an eldritch monster wearing skin. But we don’t have a lot of those running around. We do, however, have neurodivergent human beings. I’m one of them.

From an early age, I was told that my brain is strange. That I do not think like normal people. That my thinking is disordered. This seemed strange to me. My brain does not hurt. I am not filled with suffering. Some things are hard for me. But there are things hard for everyone.

But, I was told, many times, over and over again, my brain is not normal. I am not a normal human. I need to look at the normal humans, the real humans, and study them, and understand them, and become like them. Any time something seemed hard or frustrating it was proof I had to try harder to become a real human.

In a sense, I lived Lovecraft’s horror story. I was, from my own perspective, a lone mote of humanity cast adrift in an alien world, a world I could not understand, a world that was upsetting and strange and hurt me.

I was not, however, broken to pieces by it. Nor was I filled with hatred or repulsion for the strange creatures I saw. I observed and I came to understand. When they were happy, I wanted to be happy too. Being the only normal person was lonely. I envied the way they slipped sinuously through barriers that stalked me. I wondered if I, too, could have those features, could build approximations, could emulate them, could seem like them. Now that I have grown, I am praised by my alien peers, for how much like them I seem. That I am so good at speaking the way they expect me to speak. That I thrive in this environment.

Now, if you’re following, you may have taken pause at the fact that I call myself the normal one here. After all, I’m neurodivergent! Neurodivergent isn’t normal. Autistic people like me aren’t normal. People like you are normal!

That’s the kicker, though.

Normal is not real, and this, this is the inherent failure of cordoning off characters as incomprehensible.

Because every single character is normal. Everybody on the planet is normal.

Developmentally, psychologically, “normal” is a set of blinders we put on. Because when our early primordial ancestors walked into the same meadow they usually came to, they were beset by a maelstrom of sensory information. And they have only so much energy, so much effort to look and listen and smell and feel. They cannot see, in full excruciating detail, the same buttercup that has been there every day they have come to this meadow. They cannot ruminate deep on the color yellow, the shape of the petals, until it has hewn itself deep in their mind.

They cannot, because that patch of orange at the edge of the meadow was not there yesterday. And it is not in the same place as it was an hour ago.

Our brains recognize patterns. They do this to keep us safe and help us navigate the universe at all. In that sense, there is no holiness to normal. Normal is not ever guaranteed to be good for us. Normal is just the thing that our brain filters out, does not look very hard at unless we consciously fight that reflex. It is the background against which we contrast unknown.

I am normal. My autism is normal. If I had been raised on some kind of colony of exclusively autistic people, and you showed me a neurotypical person, I would have laughed at them. What a silly weird bizarre person! Why are they STARING like that? Why don’t they shake or flap or rock when they’re happy? Are they afraid of emotions, so they lock ramrod straight like that? This poor soul, you know, I took them to the fabric store and they didn’t touch anything, didn’t feel all the lovely textures and patterns. Could you give this creature a bouquet? Do they know how to appreciate any of their senses? A pitiful beast! Someone teach them how to be normal!

Normal becomes a rub. It becomes a sticking point, however, because we chose to live together, and we made rules, and in these rules, we betrayed our hand, our sense of normal.

The truth is if I abandoned Howard Phillips Lovecraft on a deserted island with Cthulu, I really sincerely believe that he would get over his mind-breaking wretched horror. He would find, to his shock and revulsion, that perhaps the first time he looks upon this creature’s visage it hurts. But the tenth time, or twelfth time, or twentieth time, it is merely a face.

Normal is a structure assembled by our minds for convenience and we act as if it is a god, when in reality it is merely a tool and one we can slap off the table and send clattering to the floor as if it is a doll we no longer want to play with.

Because my entire life, I have been told that I have a monster’s brain, a disordered brain, a brain twisted in a curious shape that harms my ability to understand others.

In my life I have met and imagined countless people, countless creatures, some very wildly different from me in priorities and behavior.

I have never in my life met an incomprehensible creature. But I have met plenty of things that I thought were incomprehensible- until I spent any time with them at all.

I have followed and spoken to and heard the stories of schizophrenic people. They were, surprisingly, not monsters.

I work with babies. They are not monsters either.

I have never met an incomprehensible monster. And every time I think I may have, I have been wrong, and I have needed to try harder.

So, to me, to call something truly alien in a sense that we can’t know what’s going on in their head, I remember that “lovecraftian” carries the name of a racist, inextricably embedded in its etymology.

164 notes

·

View notes

Photo

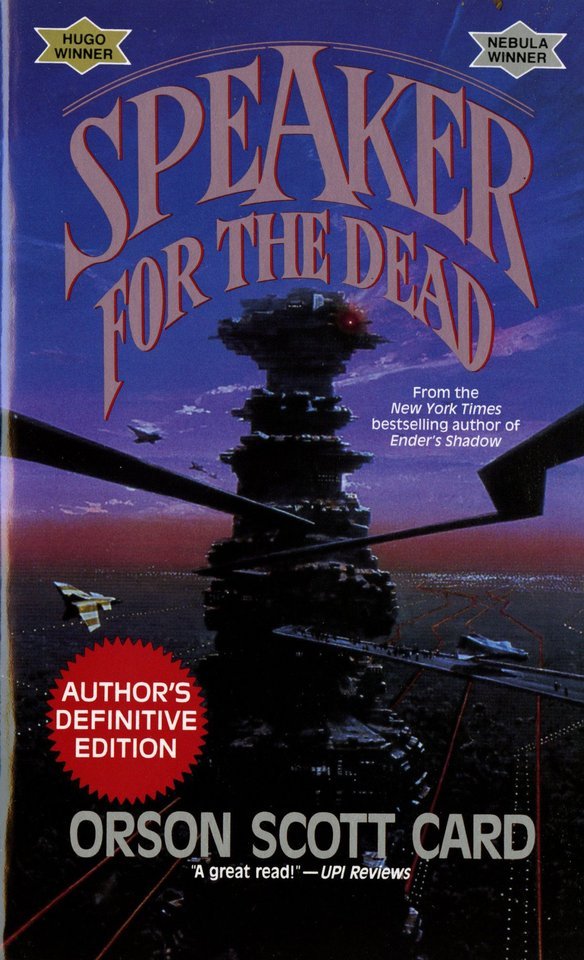

I loved this book when I first read it 3 1/2 years ago. I found it deliciously creepy, gripping, humanistic (I guess) and... baffling. How could someone who wrote a whole book about the power of empathy be homophobic? (This was just after the Ender’s Game movie came out and people were boycotting it so the subject of his homophobia was in the air.)

Upon rereading it, I’m appalled that I ever found it any of those things. This is a profoundly, nauseatingly narcissistic book; the lip service it pays to the power of empathy is actually worship of its protagonist, Ender Wiggin, and through him its author, Card himself. A quick summary: The world of Lusitania, largely Portuguese and Catholic (black Portuguese, specifically, which I bring up because he skirts around race in the weirdest way when he’s not being outright racist), is home to a small human colony and the first sentient alien species discovered since the Buggers (I cannot believe they are called the Buggers, the Buggers!) were exterminated three thousand years ago: the porquinhos, or piggies. The piggies are small bipeds with porcine faces (thus the nickname), separated from humans by a high fence that causes unbearable agony on contact (someone compares it to your fingers being filed off). This is supposed to protect them from cultural contamination, but it’s actually as much—or more—meant for humans, who fear what they don’t understand. The only humans who are allowed contact with the piggies—xenologers, or alien scholars—must try to learn as much about the piggies as they can while revealing as little of themselves as possible: they can’t even ask the questions they’re most want answered, for fear that they’ll give something of themselves away. This policy backfires tragically when the beloved xenologer Pipo is tortured to death by the piggies, and the young orphaned biologist Novinha, who loved him as a father, sends out a call for the nearest Speaker for the Dead — which happens, of course, to be none other than Ender Wiggin himself.

Ender and his kind play the role of secular priests, who investigate and then “speak” peoples’ lives, warts and all. They “[hold] as their only doctrine that good or evil exist entirely in human motive, and not at all in the act” (35), a doctrine of which I am deeply suspicious but that undergirds the whole book. Ender is the original speaker: three thousand years ago, he wrote a book called The Hive Queen and the Hegemon that spoke the Buggers’ death and taught humanity that they were worth mourning. Now, he wanders the worlds, just thirty-five years old because of the way space flight works, seeking a home for the last living Bugger hive queen and an end to the guilt that eats him up inside: guilt for the xenocide that made him the universe’s most hated man. When he hears that the piggies have tortured a human to death, he knows he must answer Novinha’s call. (He’s also attracted to her even though she’s twelve or thirteen years old, but whatever.) This is his chance to make peace between human and alien — to earn redemption for the role he played in the human/alien war that left all but one alien dead. So off he goes to Lusitania. When he arrives — two weeks later for him and like twenty years later for the colony — Novinha is grown, freshly widowed by a physically abusive man, and consumed by a secret guilt of her own; her household is tearing itself apart from the inside; and the piggies have murdered Pipo’s son and successor, Libo. It’s Ender’s job to make sense of all this in time to prevent intergalactic war and — most importantly — to redeem himself.

Rereading this, I realized what a blatant author surrogate Ender is. Not only he is literally a writer, his book is powerful enough to literally become the piggies’ religion. His word is God. He’s also flawless. Yes, he murdered countless aliens, and he’s wracked with guilt, but his redemption feels inevitable from the start — and not only that, the one surviving Bugger forgives him, because she understands his motives in slaughtering her species. Motives, as we know, are all that matter in the moral universe Card has created, and because we know Ender’s, he’s also redeemed in the reader’s eyes; his guilt is nothing more than a narrative hoop for him to jump through. (Not only that, he makes the hoops; as Speaker for the Dead, he first acts as his own accuser, then as his own judge, ruling — unsurprisingly — his favor.) Moreover, most of the characters worship him. Some literally. The AI Jane — the most ancient, knowledgeable, and powerful being in the known universe — refers unironically to his “genius” (62): “his genius — or his curse was his ability to conceive events as someone else saw them” (65). In other words, he has... empathy. Something that most humans have (and something that women have more of than men, I might add). However, in Ender, empathy is almost supernatural; it gives him the godlike ability to know (“no, not guess, to know” [65]) people without even speaking to or spending time with them. (“It was as if he were so familiar with the human mind that he could see, right on your face, the desires so deep, the truths so well-disguised that you didn’t even know yourself that you had them in you” [234–35].) Just like the author knows his characters. He can also make them worship him — again, some of them literally. Ender’s sister Valentine refers breathlessly to her brother’s “brilliant understanding of human nature” (75). His nieces and nephews think of him as “something of a savior, or a prophet, or at least a martyr” (82). Novinha’s feral children fall in love with him — as does, of course, Novinha herself (“his eyes were seductive with understanding. Perigoso, she thought. He is dangerous, he is beautiful, I could drown in his understanding” [129]. Gag me). Jane, the AI, is bored by literally every other human in the universe (”when she tried to observe other human lives to pass the time, she became annoyed with their emptiness and lack of purpose” [175]). Take this appalling passage:

Through his eyes [Jane] no longer saw humans as scurrying ants. She took part in his effort to find order and meaning in their lives. She suspected that in fact there was no meaning, that by telling his stories when he spoke people’s lives, he was actually creating order where there had been none before. But it didn’t matter if it was fabrication; it became true when he spoke it, and in the process he ordered the universe for her as well. He taught her what it meant to be alive. (175)

And the piggies, though they reject Christian scripture, turn The Hive Queen and the Hegemon into their bible. It’s like... jaw-droppingly blatant, isn’t it? Even when characters hate him, they elevate him, like the Bishop who claims he’s “as dangerous as Satan” (298).

Card’s message in Speaker for the Dead is clear: “When you really know somebody, you can’t hate them” (370). For him, to know is to love, whether you’re knowing the alien who tortured your father to death or the husband who beat you for years or the man who slaughtered your entire species.

[W]hen it comes to human beings, the only type of cause that matters is final cause, the purpose. What a person had in mind. Once you understand what people really want, you can’t hate them anymore. You can fear them, but you can’t hate them, because you can always find the same desires in your own heart. (370)

The problem is, he’s created a story in which this must be true. The piggies who tortured Libo to death didn’t know they were torturing him; they thought they were giving him their highest honor. Ender was a child when he slaughtered the Buggers, and he thought it was them or us, that he was dooming humanity if he didn’t. Card makes empathy easy, uncomplicated, for his characters and the reader, and in this way robs it of all its power: he makes it the simplest and most obvious choice. That’s because this book isn’t truly about empathy at all: it’s about deifying himself in fictional form.

Stray observations:

Because Novinha blames herself for Pipo and Libo’s death, she endures her husband’s physical abuse as a form of punishment (“It’s no more than I deserve” [125]). The Bishop sanctions this as her “penance” for adultery later on. Foul.

Most of the Lustanians are supposedly black, but none of the characters are described as black (except Bishop Peregrino, whose face had “a pinkish tinge under the deep brown of his skin” [155], which to me seems like a profound misunderstanding of how dark skin works?), and Novinha’s hair reads as a white woman’s hair to me, or at least not a black woman’s, though I guess he’s not explicit about it. Oh and also, Ender is lily-white, startlingly white, in a way that evokes unsavory white savior imagery. (When he’s speaking Novinha’s husband’s death, in front of a huge crowd, “his white skin made him look sickly compared to the thousand shades of brown of the Lusos. Ghostly” [257].) He’s also compared to Pizarro.

The colony is very conservative, which Card actually celebrates: “If there were no powerful advocate of orthodoxy, the community would inevitably disintegrate. A powerful orthodoxy is annoying, but essential to the community” (158). Etc. Marriage and monogamy are highly valued.

The piggies are super sexist. Theirs is supposedly a matriarchal society, in which the females have all the power, but in fact they get pregnant, give birth, and are eaten by their babies in their own infancy. The matriarchs are sterile, which is why they survive to adulthood. When a character suggests helping the fertile females survive as well, Ender replies “To do what? They can’t bear more children, can they? They can’t compete with the males to become fathers, can they? What are they for?” (325). A female named Shouter supposedly rules the tribe, but a male named Human is Ender’s ambassador; he — again, a male — is the most important piggy in this story. Piggy society is a misogynistic man’s idea of matriarchy — on other words, not a matriarchy at all.

1 note

·

View note