#I know you meant ''Visual Concepts made both games'' rather than specific teams of people. I just like thinking about this sort of thing LOL

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

Do you know the people who made Floigan Bros also made claymates

IDK if it was the same people (too lazy to pull up & compare credits right now, but they employed a lotta people & worked on multiple projects at a time; I see Greg Thomas mentioned on both sometimes but he was one of the founding members so IDK if he was just doing #FloiganInterviews or if he worked on it) & Visual Concepts did a lot of video games (they did & still do a loooooot of sports titles) but yes I know they were by the same development company ^_^

#I know you meant ''Visual Concepts made both games'' rather than specific teams of people. I just like thinking about this sort of thing LOL#They also did the first ''ClayFighter'' game(s?) with Interplay before Interplay started doing them all

68 notes

·

View notes

Text

June '20

Trials of Mana

Maybe not the highest profile remake Square-Enix have put out in recent memory, but one that was pretty exciting for me. I played a fan translation of the Super Famicom original some 20 years ago, so while it's not particularly fresh in my head, there's just enough there to enjoy some infrequent little pangs of nostalgia. The move to 3D has made for some welcome changes to to combat - jumping adds a vertical element to combat that wasn't present before, and enemy specials being clearly telegraphed and avoidable puts a little more control in your hands. There's still a good amount of 16 bit jank though - combo timing feels unreliable, the camera's often a pain, there's plenty of questionable hit detection, and you definitely wouldn't want to leave your fate solely in the hands of your party's AI. Willing to put most of this aside, what actually mattered more to me was that it still had the kind of playful, breezy nature, it looks and plays nicely, and that it progresses at a nice clip. Party selection will change the way you fight moment-to-moment, but only provides minor and very brief deviance from the main storyline, most of which is the kind of schlocky cartoon villainy that will have you looking for a skip button before it would illicit any kind of emotional response. But you know what? Overall, I still enjoyed it a lot.

So while it may not be revolutionising the action RPG, what it does show is that Square-Enix is capable of acknowledging their history of previously untranslated works, and that they also now have a pretty good template for getting a B-tier remake of such titles out in a reasonable timeframe. Where do I send my wish list in to, team?

Sayonara Wild Hearts

As a one-liner found on the back of the box, 'A pop album video game' is about as on-the-nose as it gets. The old "it's not for everyone" adage is definitely applicable, and its defiance of traditional video game metrics is not in any way subtle. How sophisticated is the gameplay? Not particularly. How long is it? Not very. But how does it make you feel? Now you're talking. It presents a simple but deeply relatable story of a broken heart, and leads from there with a catchy tune into a fast and colourful onslaught of new ideas, perspectives, and concepts. That is to say: it has the potential to make you feel all kinds of things.

One especially celebratory note was how well the game is structured to fit into the album structure it boasts about. Stages flow quickly into one another, and while shorter, more compounding numbers are often about introducing new ideas and themes, moving on to the next is a few simple button presses and a brief, well-hidden loading window away. Inevitably there are more standout stages, those that feel like the hit singles; the longer, verse-chorus-verse type joints that grant the space for more fleshed out visual story telling, and that smartly synchronise their percussive hits, soaring vocals and the like to appropriate beats of play. A lot of the gameplay can easily (and cynically) be reduced to "it's an endless runner", but to liken this to a cheap re-skin of a confirmed hit-maker is to wilfully dismiss so much of what it does better and so much beside. You can play it on damn near everything, and for the time it takes, it's well worth doing.

Twinkle Star Sprites

I've meant to play this countless times before. I've almost certainly passed it by while strolling through arcades, the Saturn version has never been hoovered up into my collection, and the PS2 collection this particular version belongs to - ADK Damashii - is no longer a cheap addition to anyone's library. The digital version of it for PS4 however was however recently on sale at a point that saw me receive change from a fiver. David Dickinson would be proud.

Having now credit-fed my way through the game's brief arcade mode, there's no doubt in my mind that the nuance of its systems are going to be glossed over in this rather ham-fisted appraisal. At least at face value, there's plenty of character and charm to appreciate in its colourful and cutesy style. As a two-player, vertically split-screen title, its a pretty clean break from a lot of a shooter's typical characteristics - rather than 6(ish) stages of hell, its a series of one on one battles - and all the better suited to 2 players for it. As enemy waves come at you, taking them out in chains can generate attacks to the other player; however if these attacks are too small then it's entirely possible they'll be killed off again, and an even bigger attack will come straight back at you. Think of a bit like competitive Tetris, but with shooting rather than puzzling. It's a neat and curious little game, that's likely best experienced properly, with a friend on the other side of the sofa to hurl abuse at.

Blasphemous

Let's get the lazy-but-effective description out of the way: it's a 2D MetroidVania Souls-like. You've got "that" type of map, definitely-not-bonfires and definitely-not-Estus Flasks. You are encouraged to return to your body upon death, the combat system is very reliant on parries and dodge-rolls, and there's even a dedicated "lore" button to use on every item you pick up.

While this likely sounds dismissive, it's more about addressing the elephant in the room. To give some context, these are both types of games that I love, and the end product here has done a pretty good job of bringing them together. The exploration is pleasantly open - gatekeeping is typically done less by specific items and abilities, and more by just which areas you're brave enough to poke your head into. It's a little bit of a shame that most of the new abilities have to be switched out for others rather than adding to a core arsenal of moves, but at the same time its base setup gives you plenty of ways to deal with any number of combat scenarios. This is of course best demonstrated by the boss encounters, which are wonderful affairs - big, gruesome, thoughtful variations on approaches to combat, which drop in at a nice pace to keep you from ever getting too cocky. The theming in general is wonderful, and the name is certainly appropriate - there's a lot of deep catholic inspiration in its gorgeous backdrops and environments, but then layered on top are some chilling elements of religious iconography, along with a cast of disturbing devotees and martyrs to sufficiently unsettle you. It's arguably a small intersection of the gaming population that it'll appeal to, but if you're in there, it's a real treat.

Death Come True

The first thing you see upon starting is the game's central character breaking right through the fourth wall to tell you directly not to stream the game or to share anything that might spoil the story. The first rule of Death Come True, and so on. I consider myself fairly well versed in such etiquette, so to then have the screenshot function entirely disabled for the whole game felt a little like being given a slap on the wrists for a crime I had no intention of committing. I don't envy the team trying to market it, that's for sure.

The reasoning behind this is clear at least - it's a game that is in total service of its plot. Consider a mash-up of a 'Choose your own adventure' book and a series of full-motion videos, and you're mostly there. Unless you were to walk away from the controller or perhaps fall asleep, there seems very little chance that your play time will deviate from the 3 hour estimate - which will certainly put some people off, but is understandable given the production values, and personally, quite welcome in the first place. In terms of replay value, there are branching paths that a single route will obviously skip: as an example of this, in looking up a screenshot to use in lieu of taking my own, I found a promotional image of the central cast, only to not recognise one of them at all. One thing that such a short run-time does ensure though, is that minute-for-minute, there's plenty of action; without wanting to speak about the story itself (rather than in fear of reprise for doing so, I might add), it kicks off with plenty of intrigue, shortly thereafter switching to full-on action, and then strikes a pretty fine balancing act between the two for its run time. It doesn't get quite as deep or as complex as I would've hoped given the team's pedigree, but I do like it, and think it'd actually be a pretty fun title to play with folks who normally don't concern themselves with games. By the same token, it's probably not for the 'hardcore' types looking for something to string out over dozens of hours.

Persona 5: Dancing in Starlight

After the generous main course that was Persona 5 Royal, I figured that I'd follow up with dessert. I did however wait until a weekend where I knew my girlfriend would be away, so as not to trigger any unpleasant flashbacks to looped battle themes, and the chirpy, indecipherable voices of Japanese schoolkids that made it so painful to endure as a non-gaming cohabitant.

Immediately, it's clear that very little has changed since Persona 4's take on the rhythm action genre. The core game, while still functional and fairly enjoyable, hasn't changed a lick. Perhaps the most notable improvement to the package as a whole is in scaling back on a dedicated story mode, and instead just having a series of uninspired but far less time-consuming set of social link scenes that pad things out. The biggest flaw is repeated wholesale though, in that trying to stretch out noteworthy tracks from a single game's playlist into a dedicated music game leads to repetition - and there is a much less prolific gathering of artists involved in remixes this time. I'd be willing to wager that it's a very similar story once again with Persona 3: Dancing in Moonlight, but I'm not about to ruin a perfectly good dinner to start with the sweet just to find out, if you'll excuse a second outing of the metaphor. Still, again compare these to Theatrhythm though - where Square-Enix plundered the Final Fantasy series in its entirety, along with spin-offs and other standalone titles to put together a library of music worthy for the one single game. Cobble the tunes from Personas 3-5 together into one game, and you're still coming up very short by comparison.

#trials of mana#seiken densetsu 3#sayonara wild hearts#twinkle star sprites#blasphemous#death come true#persona 5 dancing in starlight

1 note

·

View note

Text

Last week, in a tiny hidden bar typical of Melbourne’s inner east, Nintendo gave us hands-on time with Super Smash Bros. Ultimate.

Nintendo Australia had hoped to get us in front of a newer build of the game (we would have loved to try King K. Rool and Simon Belmont!); however, the build was identical to the one we played at E3 some two and a bit months ago. However, where our time with the game at E3 was rushed and hectic, this time we had a solid two hours in a laid back environment which allowed us to get comfortable and explore more of what it had to offer.

And what a difference that makes to perspective.

To sum things up, we had a smashing good time, and we’re now more excited than ever to add Smash Ultimate into our gaming libraries. Our Publications Director David Johnson and Special Projects Director Shona Johnson were at the event. Here are a few of our thoughts on the game:

Shona Johnson, Special Projects Director

As a long-time Smash player — I’ve been with the series since the Nintendo 64 — playing Ultimate with a big group over food and drink was instantly familiar, taking me back to happy times when I played Melee for hours on end with friends or, more recently, Smash Wii U parties. Although it’s been a while since I last fired up a game of Smash, and I haven’t played since the demo at E3, my Smash instincts and muscle memory kicked in, throwing me into that wonderfully chaotic place where some of my favorite characters are beating each other up.

At E3 there were a limited number of play slots available (strictly one per person), and I signed up to play it competitively, which meant that part of my attention was given to attempting to win, meaning I played it safe with characters I knew well, in addition to checking out what was new and different. Fortunately, towards the end of the second day of E3, the lines died down to the point where the wait wasn’t hideous, so I was able to get in a few rounds of fun play where I could at least try out some of the new characters. I had fun and walked away from E3 feeling incredibly impressed by the game’s polish, but spending two hours with the demo gave me a chance to try out a lot more and really get a feel for the gameplay.

The demo for Smash Ultimate had 23 out of the game’s 103 stages to select from.

Also 30 characters of the roster were present, but a few classic fighters were held back.

Matches were limited to two-minute free-for-alls with up to four players playing solo or in teams. Items were on, and we couldn’t change any of the settings. A roster of 30 characters was available, and we could choose from 23 stages. I was able to play most of the characters and stages available. The event had multiple stations, most of which had Pro controllers, but a couple had GameCube controllers. It’s nice to see the GameCube controllers being carried through, as many Smash veterans are familiar with these, and, at the end of the day, each player will be able to set up their preferred controller configuration.

Existing characters feel familiar, and most of the changes to their moves are subtle if any have been made at all. Most of them appeared to be fairly well balanced, although it’s hard to say given that I was swapping characters a lot and playing against people of varying skill levels. Ridley and the Inkling were the new characters in the demo, and both had their own unique movesets that took some time to get used to (and honestly, I didn’t play them enough to get used to them). Ridley is slow and heavy, and I struggled with him a bit because I struggle with that sort of character more in general, and I found that the pace of the gameplay made it hard to spend time effectively splattering paint over everyone as the Inkling. That said, in one match while playing a different character I kept getting trapped in paint by another Inkling which was somewhat annoying for me but great for them I imagine!

The list of stages we had to choose from included both new and returning ones. A big difference in Ultimate is that players choose the stage before choosing characters, with the idea that players can choose a character to suit a stage, although that never really crossed my mind because it’s something I’ve never considered before; for me, it’s more the stages in general that I love or hate rather than playing on them with specific characters. And at this event, I was much more in the mindset of wanting to see everything and try it all out, so I never even thought about the stage while I was selecting my character.

All of the stages look amazing. Of the new ones, the Great Plateau Tower from Breath of the Wild is a fairly small one where the roof collapses in occasionally, and surprisingly this isn’t a hazard; it just looks cool. Moray Towers is the new Splatoon stage, and it’s a series of sloping levels stacked vertically above each other. I found this one hard to fight on because players were more spread out and on different levels which made it hard to land hits. I imagine this will be better suited to people who like slightly slower gameplay and having more chances to recover, or it might be more fun with eight players. Conversely, I cannot imagine how chaotic eight-player Smash is going to be on the Great Plateau Tower!

In Ultimate, having items turned on didn’t feel quite as chaotic as they have in past games, and I think they’ve been nerfed a fair bit. The once-almighty hammer — I got one and the guy next to me said “uh oh” as soon as he heard the music — didn’t produce the KOs or near-KOs I would have expected in the past. Likewise, Smash Balls didn’t always guarantee KOs like that did in Smash Wii U/3DS. They’re also harder to grab, although they also sometimes just land on the ground and stay still; the first time this happened we were all wary of the Fake Smash Balls and ran away from it until someone hesitantly kicked it and realized it was a real one!

I felt that I had to be very accurate when landing blows and dodging. It should lend to a technical playstyle that will suit competitive players and those who play for fun.

Overall, the gameplay feels faster and more precise. Thankfully there’s no Brawl-style random slipping and tripping, and I felt that I had to be very accurate when landing blows and dodging. Fast characters like Fox and Sonic covered ground incredibly quickly, and some of the heavier characters like Donkey Kong felt more agile. If you’re not paying attention, you can be sent flying off screen and not realize where you are at first! It should lend to a technical playstyle that will suit both competitive players as well as those who play for fun (because the core concept of Super Smash Bros. is fun).

Two hours of the one style of match flew by, so I can only imagine how many hours I’m going to get out of the game playing with different modes and rules. And that’s before I even consider any possible single-player modes, which I hope there will be for the times when I take my Switch with me on the go by myself. I didn’t want my time with Ultimate to end, and now more than ever I eagerly await December when I can get the full version into my hands.

David Johnson, Publications Director

Super Smash Bros. Ultimate has all the potential to be the best Smash Bros. game to date. Thus far, everything Nintendo has shown oozes with that careful attention to detail that Nintendo is simply known for. While we don’t know all of its secrets yet — there’s this maybe “Spirits” mode on the main menu that we know nothing about that may be a major single-player component to the game(?) — I can’t help but be extremely excited for the series to make its way to the Switch.

How can I describe Ultimate? Well, the short answer is that it feels very much like Smash Bros. More specifically, it feels a lot like Melee, though admittedly I haven’t pulled out my GameCube to play it in quite some time. While there is a good dose of beautiful chaos in the game caused by items, assist trophies, and Poké Balls, it’s all a manageable sort of chaos. It just feels good to dart into piles of characters, take some pot shots (or get hit trying!), and then escape to go at it again.

At the event, they had a couple of stations with GameCube controllers set up, but I figured I would give the Switch Pro Controllers one more fair go, even though the default control scheme of every controller since the GameCube has made me want to cry. And while I still wasn’t 100% in love with the Pro Controller’s default setup, I did find myself hating it a lot less. But I still will either be using a GameCube controller or resorting to making a custom controller configuration for me when the game comes out.

Because we had two solid hours with the game, I went and truly experimented with characters both familiar and unfamiliar as well as played practically every stage that was on display. For the characters I was familiar with, I found the differences between the Ultimate fighters and their earlier incarnations rather subtle, though Marth especially seemed incredibly floaty, much more so than he was in Melee. (That said, I chalk this up as a good thing!) For characters I was unfamiliar with — Ridley, Inkling, and the host of DLC characters from Smash 4, they all felt incredibly unique from the cast of old, and that’s hugely refreshing. That said, the fact that many of the characters are becoming Echo Fighters (thus with the official salute that they’re “the same character” as some other), makes me happy; finally, we can hope to see so many characters truly become unique entities rather than carbon copies of one another.

And the stages were mostly fantastic. They look utterly fantastic, and they set the stage for a visually impressive game. And none of them felt like they detracted too much from the overall premise of the game: dominating over all your friends. That said, I still utterly despise the Mega Man stage brought forward from Smash 4, though I’m extremely relieved that not only can we trigger each stage’s Ω (omega) form but also simply play with the stages as is sans their various stage hazards. Finally, we can play the Dr. Wily stage without the Yellow Devil ruining an otherwise fun game.

The Smash Balls’ effectiveness has been nerfed quite a bit. In order to counterbalance that, the Assist Trophies seem much more powerful.

As far as the items go, there were only two major differences I’ve noticed in playing the game. First and foremost, the Smash Balls’ effectiveness has been nerfed quite a bit. Since Brawl, while it’s always been possible to survive a Final Smash, it was exceedingly unlikely. However, now the survivability has been greatly upped as the Final Smashes aren’t really so “final” any longer. Perhaps this is done in order to keep it in line with how short many of the moves have been made or just to allow them to not disrupt gameplay as much, but it really makes it feel much more balanced as a whole. (That said, the Smash Balls seemed extremely difficult to even get to as they moved far quicker than before!)

In order to counterbalance that, the Assist Trophies seem much more powerful. In previous games, Assist Trophies generally remained on-screen for no more than a few seconds at most. Now, many Assist Trophies have been modified to become temporary allies on the stage, giving you a not insignificant advantage. While the Assist Trophies are able to be defeated and don’t dish out overwhelming damage in one go, they possibly will be one of the more contentious design decisions for Smash Ultimate.

The gravity well item popped up quite a bit in the game, and its effects can be felt everywhere.

Thematically, Ultimate is full of so many little subtle details that show just how much Sakurai and his team love Nintendo and its entire legacy. The subtle changes to Link to bring about his Breath of the Wild form are carefully balanced by pushing Princess Zelda and Ganondorf to other parts of the timeline to showcase the breadth of the Zelda series. The fact that the Echo Fighters now exist allow for a greater depth of exploration into the various franchises without providing an overwhelming feeling of sameness permeating everything, such as when Dark Pit was announced as a separate character in Smash 4.

Outside of my hands-on experience, what I think impresses me the most about Ultimate is just how much variety there can be inside the ordinary Smash experience. Sure, there are tournaments and oodles of other features and modes, but having well over 60 characters to choose from and over 100 stages to fight on will give so many permutations of fighting that it’ll be impossible to play them all. Whenever I’m smashing it up with friends, there always comes to that point in the evening when I stray away from the characters I’m familiar with and start playing the characters I’m either terrible with or simply don’t play as much, and Ultimate will ensure that I’m always wanting to experiment and try another character again and again beyond that.

December 7 cannot come fast enough. Smash Ultimate, I’m desperately waiting for you.

Super Smash Bros. Ultimate will be released on December 7 for Nintendo Switch. Thank you to Nintendo Australia for inviting us to come and Smash!

Two hours with Super Smash Bros. Ultimate this might just be the best Smash so far Last week, in a tiny hidden bar typical of Melbourne’s inner east, Nintendo gave us hands-on time with

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

ANN Interview: Made in Abyss Composer Kevin Penkin

This is all originally from an Anime News Network interview.

Interview: Made in Abyss Composer Kevin Penkin

Interview Info: October 7th, 2014 By Callum May for Anime News Network

As a person who is aspiring to become a score composer (kind of an unrealistic dream that I can’t seem to let go), I found this really, really interesting. I left a lot of stuff in because I feel like there’s so much to unpack, and most of the information is interesting to me.

I did edit a few things out (mostly not music related), and I put in some square brackets for the sake of explanation and context.

It appears that all of your anime soundtrack work has been with Kinema Citrus. How did you come to work with them?

I met Kinema Citrus when we were attached to the same project called "Under the Dog"[...] Since then, we've enjoyed a wonderful relationship on other projects such as Norn9 and most recently, Made in Abyss.

Do you expect to be working on anime outside of Kinema Citrus in the future?

That would be lovely. It's not entirely up to me, but that would be lovely. I'm very grateful to get any work in anime, as I'm very, very passionate about this industry. If I do get the opportunity to work on another project from any company, I would consider it to be a great privilege.

What was your first reaction to Made in Abyss when you were approached with the project? How much of it did you get to read?

I was given the first 4 books as source material to read and was immediately taken by the world that Tsukushi Akihito had created. The early stages of production were just me going through the books and finding interesting scenes or artwork to write music to.

Who did you have the most contact with on the Made in Abyss staff? What sort of questions did you ask?

I have a music director named Hiromitsu Iijima, who I would talk to on a daily basis. Every couple of weeks after a large chunk of the soundtrack had been written, we'd set up a meeting with Kojima-san [Director, Storyboard, and Episode Director] and Ogasawara-san [Animation Producer who works with Kinema Citrus] to discuss the current state of the soundtrack. We'd discuss if there were any points of concern or if anything needed to be changed. We essentially repeated that process until we were ready to record, mix, and finalize the music.

What sort of instructions and materials were you given in regards to making tracks for Made in Abyss?

In addition to all the manga books, I got a lot of background and concept art that I could reference. Trying to match the visual colour palette and the musical "colour" palette was really important to me. For example, looking at how the foregrounds and backgrounds were so juxtaposed gave me ideas such as writing for a small ensemble of instruments, but recorded in a large space. This was meant to act as a metaphor for Riko and Reg exploring in this humongous, expansive cave system.

Could you elaborate on the idea of developing a musical "colour" palette? How do colours and music correlate?

It might be best for me to give some examples. Starting more broadly with Reg, he's a character made up of both organic and mechanical body parts. So combining organic and mechanical sound sources when writing for Reg felt perfectly natural.

Talking more specifically about colour correlation, there is a lot of information in colour that allows us to perceive essential things such as relationships and distances between objects. The sound has this as well. Depending on how you combine the essential components of sound (pitch, timbre, harmony, loudness, etc.) and controlling how they either complement or clash against each other is going to result in a specific listening experience.

“Depths of the Abyss” is another example of the musical key slowly “ascending” over time to act as a sonic metaphor for the Abyss rising up to surround and engulf our main characters. There's the flip side to this as well. The title track “Made in Abyss” features descending string passages to represent Riko and Reg's descent into the world of the Abyss. I've personally found that thinking about these sorts of concepts can be very helpful when trying to establish the palette of sounds (colours) that you think will complement and/or enhance what's being displayed on-screen.

How much did you know about how your music would be used? Did you know that Underground River would be used to introduce the world in a montage just six minutes into the first episode?

Syncing music to anime is a slightly different process than what I've experienced [...] In the limited amount of anime that I've done, I've typically been instructed to create music away from the picture, which is then matched to the desired scene(s) at a later stage of production. This might contribute to why a lot of anime music can feel like a music video at times. From what I've experienced and from what I can research, I've seen directors take large chunks of time out of an episode to let the music take over so that the audience can “breathe". Underground River is a good example of this. [In episode one] you're introduced to characters, their motivations, world building, monsters and action all in a very short amount of time. Taking a minute or two to let the viewer digest all this can be very effective, and music can help with that.

You're also known for your work on Necrobarista and Kieru, two Australian indie games. What draws you to working on Aussie games, even after making your debut internationally?

[Being an Aussie], there's a lot of pride in how interesting and unique Australian indie games are. I've always had a connection to games and Australia. So even though I'm currently living in the UK, the fact that I'm still able to work on games with friends who are living back home is something really special.

It's not common to see an Australian in the credits for anime. Do you think musicians from outside of Japan are becoming more common?

I [...] grew up watching Dragon Ball Z on TV. There are actually two scores composed for that series depending on [whether you are watching dub or sub]. So I actually grew up listening to Bruce Faulconer's music for DBZ, not Shunsuke Kikuchi's original score.

[In regards to other foreign anime score composers] There are also other examples such as Blood+ with Marc Mancina, Gabriele Roberto with Zetman in 2012, and Evan Call has done quite a few things as well [like Violet Evergarden]. So I think while it may be becoming more frequent to see musicians from outside of Japan being attached to anime projects.

How would you say composing for games differs to composing for an anime series like Made in Abyss?

Speaking for myself, composing for games, anime, or whatever typically starts the same. I feel that if you're able to nail the concept and/or tone of the project, that's a big part of the process already completed. Then it's just up to the individual needs of the project. Games are typically approached from an interactive point of view. If it's film or TV, you need to know if you're writing to picture or if you can write with no time contractions like I described before. You sort of go from there really.

How would you describe that concept/tone of Made in Abyss?

Made in Abyss offered the perfect opportunity to get really specific with instrumentation. We had analog synthesizers, field recordings, vocal samples, and much more that were heavily manipulated to create distinct electro-acoustic textures. Deciding where to record was also a really important discussion, and we ended up recording at a studio in Vienna.

[It was] a huge, state of the art recording facility just outside central Vienna. I asked for a custom chamber orchestra comprised of three violins, three violas, two celli, one double bass, two flutes, two clarinets, one bassoon, two french horns, one trumpet, one trombone, and one tuba. Totaling 19 musicians. Each musician had their own “solo" part, meaning that there was up to 19 different “lines” being played at the same time during a piece of music.

The concept behind such a setup was to represent the small company of characters exploring the Abyss. Everyone's in this massive underground cave system, so I felt having a small group of soloists in a space designed to fit over 130 musicians was the perfect sonic metaphor for this. It just so happened that we were also working with some insanely good musicians and an unbelievable technical team as well.

If you were given the chance to collaborate on a soundtrack with one composer working in anime today, who would it be?

That's an interesting question. To be honest, I think I'd rather be an understudy of someone really experienced, rather than write side by side with them. If I could be a fly on the wall while Cornelius was writing Ghost in the Shell Arise, or Yoko Kanno while she was writing Terror in Resonance, that would be so, so informative. That said, Flying Lotus just got announced as the Blade Runner 2022 composer so I'd do anything to get in on that, even though it comes out in a few days (laughs).

Made in Abyss is one of the most highly regarded anime of the year. What do you think about the reaction to it?

I can't tell you how happy I am about the reaction to Made in Abyss. Writing the soundtrack was tough. The music is experimental in nature, and it required a lot of time and effort from many, many people. Everyone came together to make this work, and I'm over the moon with how it turned out.

#made in abyss#anime composer#anime news network#anime interview#score composer#score composer interview#ann interview

1 note

·

View note

Text

So, You Want to Codesign?

by Elaine Fath, game designer

Hey, game dev’s! How do these phrases strike you?

“I just couldn’t grok that part.” “The playtest is next Wednesday.” “The rigging on that part’s really messed up.” “The FTUE is really coming along nicely.” “That level is totally unbalanced right now.”

How about these? “We need to set up a way to measure the proximal outcomes.” “I’m really concerned about what kind of far transfer this experience will have.” “We’re wondering about the overall journey map of this experience.”

Chances are, if you’re involved in game development, there was at least one phrase in the first set you were familiar with. That second set? Maybe not so much, depending on your field. These are actual quotes from actual teammates whose field of expertise is something other than making games. Those examples alone are taken from the past three months of collaboration on a health app with experts in Smoking Cessation and Weight Management. If you felt lost and confused, join the club: we were all speaking English, but none of us spoke the same language!

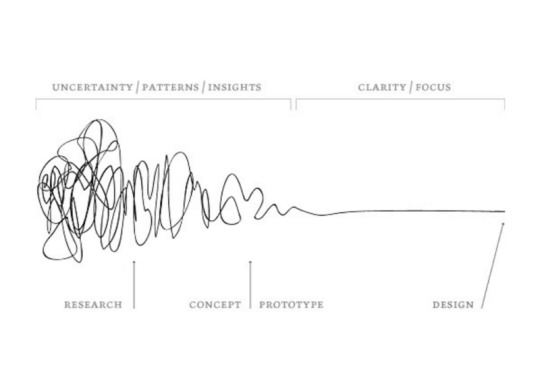

Not all games are made by a traditional game design team. A lot of games need experts outside of our wheelhouse: scientists, UX designers, parents, children, educators, researchers, professors...depending on your experience, it could be anything. If you’re not careful, all of those experts, including you, can get into a room, think they have a productive conversation... and then leave with totally different ideas of what is about to get made.

Enter codesign. Codesign is a field meant to help cross-discipline teams collaborate effectively and quickly. Codesign is a concept taken from UX research and design, and also the more-generalized field of “Design Thinking.” One major tenant of codesign is that meetings are artifact-based: together, always be making something concrete. For an overview of the idea of Design Thinking, I recommend Stanford’s D.School website!

I’ve run codesign sessions before, but running three to five sessions a week for three months in a game-specific context was all new to me. Over the course of the past three months, I learned a lot about what to do and not to do. I want to share some of those takeaways.

WHAT I LEARNED TO DO:

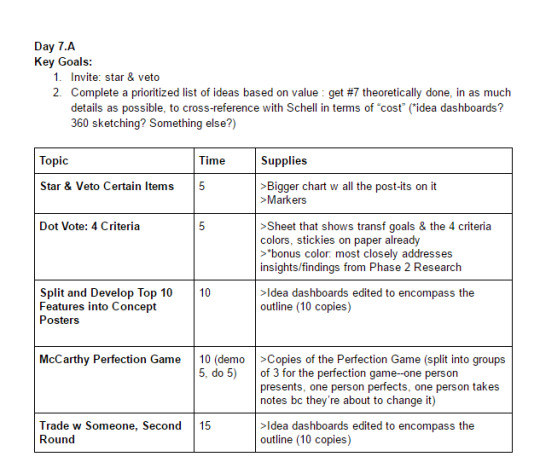

1. Keep a standard lesson plan format so that you don't go crazy every time you need to plan one.

When you’re running regular meetings in which you have to prep supplies, materials, and activities, you run into a common problem for beginner K12 teachers. Picture this: you’ve planned five separate lessons for the day (reading, math, social studies, science, and an essay project). You show up and realize that you’ve forgotten at least four supplies across the five subjects and the lesson plan for the fifth. That’s a recipe for a ruined day. How are you supposed to run the lessons as well as account for the supplies and gauge how everyone is doing?

Having to prepare so many fully-facilitated experiences and then showing up prepared can be a tremendous cognitive load. Especially since you’ll need the extra brain space to get creative during both planning and also during the facilitation. Try to keep a standard format for writing up what you’re doing and what you need and use it to track prep as well as look back on later for time estimates and activity ideas. Otherwise, it will feel like you’re reinventing the wheel every time.

2. Look to Design Thinking and codesign methods for activity-based, generative-focused meetings. Luma Institute's guide for action-based activities is a good introduction.

Often, you’ll have a goal in a meeting--”we need to prioritize these features,” “we need to see what everyone has in their heads about what this idea could look like,” “we need to generate as many ideas as possible,” “we need to narrow down to one idea,” “we need to understand what our goal is here”--but you won’t know how to get there. Starting to develop a sense of what activities exist out there for what goals was something I was grateful for doing, because they served as recipes that I could adjust as necessary rather than having to invent activities all the time.

3. Use the Transformational Framework topics. Write down your answers, then have your experts edit them.

I found that writing down my assumptions and then having the subject matter experts correct me where I was wrong with the workbook pages in front of them was a fast way to get something down early. For example, I discovered my assumption of the audience as 20-to-30 something gamers was completely incorrect. I also discovered that the way I was prioritizing our goals was totally wrong. But if I hadn’t tried to write them down, I wouldn’t have known.

4. Try to take risks by getting things in writing or concrete artifacts as much as possible, even if you think your take is wrong.

Most people can't articulate on a blank page, but can totally tell you where you messed up. A blank whiteboard can feel intimidating to non-designers. It can feel scary for your ego, but take one for the team. Type up the doc. Write an example of what you want to walk out of the meeting or the week with--if it’s a 6-page design doc, write a dummy doc with lorem ipsum in some places and show it to the team at the start of the week. Draw a picture of what you think the flow of the app will be and have others correct it. Bring materials for people to change it. Call out that it’s a draft, make it look sketchy and piecemeal so that people don’t feel bad marking it up or correcting it.

5. Use research papers in your transformation subject area to start developing a shared language between disciplines.

You’ll want to be able to have some shared vocabulary when making things together. A team I worked with published a paper about how to do this last year. The paper is about how to get a team of experts in different fields “speaking the same language” through a mix of reading the same papers, making things together using writing and simple paper supplies, and talking about what’s working using those prototypes.

6. Love & trust your teammates to be experts

Across disciplines, there can be a lot of mistrust that comes from not understanding their work. Here is an excellent GDC talk that includes our CPO Chuck Hoover that discusses tips for how to do this effectively. See: Production is Working at the Heart of the Team

7. Teach them about game techniques using a "video lit review"

If you’ve played a lot of games, it’s easier to “picture” an idea and how it will work in its final form. Something that you imagine with glitter, sparkles, pizzaz, and a universe of context might come across as flat or insane to an expert colleague who has never played Mario Kart. When you're talking about game design terms, it can help to do a 3 minute video of examples of that mechanic in practice in other places--that way, your team has seen examples before and can now talk about them, too. Encourage your other experts to do the same with their field. Maybe they have a talk or PowerPoint they always share, or a paper they wrote that sums up their expertise or what they want for the game.

8. When you’re behind, be brutally honest but don’t place blame.

Teams learning to design together move slowly at the start. It can be tempting to lay blame on people arriving late to meetings or those who don’t seem as checked in, or whatever seems to be happening from your frame of reference. Instead, I took a step back and just conveyed the facts: I had everyone collaboratively estimate how many hours of work remained and cross-reference it with the number of hours we had left together. Then, I asked: what can we do about the discrepancy? And we brainstormed ideas to try. I learned two things. One, there was a ton happening that had nothing to do with my frame of reference of the problem. Two, we picked three solutions to try as a team, and people were far more committed to trying them because nobody felt blamed. We made up the difference and hit the original deadline.

WHAT I LEARNED TO DON’T

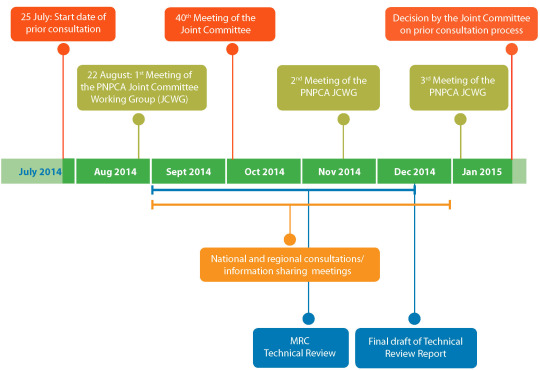

1. Don't put off making a visual roadmap of where you're going and WHY you're doing these sessions--people don't read the written outline as "big picture."

I’ve used everything from a post-it wall to sketches to Photoshop to google slides to make this. The format or structure matters less than the fact that it exists and that people understand it. Here are some examples, but generally all you need are dates, what you’re making on that date, and what you’re trying to accomplish/have at the end. I have a hunch that making it in front of everyone and then updating it/moving the “you are here” marker every meeting in a visible place is probably a good idea.

Courtesy of majorindependence.com

Courtesy of template.net

This was a major mistake I made: I got so deep into planning and prepping that I really never shared the big, long-term “why’s” with my clients, and they didn’t have a sense of progress as a result. I thought sharing a dummy outline of what we’d have at the end would be enough, and it just wasn’t. Every meeting, take two minutes to describe where you’ve been, what you’re doing that day, and how it fits into the larger plan.

2. Don't forget to schedule/budget time for open-ended question/discussion breaks at the end of meetings.

Or people will leave confused and feeling like they don't have enough wiggle room to discuss what matters to them. This process is unfamiliar and often people need to feel heard at the start and end of meetings in order to feel comfortable trying something new.

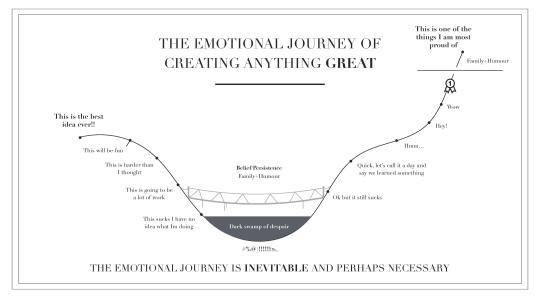

3. Don't forget to frame design as messy, generative, uncertain, full of bad ideas, and not about sitting on it until you get the "right" answer (Stanford's Design resources do a good job of this).

Again, so many disciplines are not steeped in the exact kind of uncertainty that design is, and many clients come from a work culture where you sit on an idea until it feels polished. This is very bad for the creative process because you don’t fully explore the possibilities! But on the other hand, people naturally have a fear of appearing stupid in meetings if they feel like they’re not coming up with “good” ideas or thinking on their feet well. Frame design as messy and be open about your own less-than-polished ideas. I totally forgot to frame the process as rough and changeable, and I had a lot of stressed-out clients for the first two meetings as I continuously pushed them to produce outside of their comfort zone. All I needed was to message that I, too, get heartbroken when we throw away stuff after pre-production, and so does everyone else! But it’s a necessary mess. Lean into it.

4. Don't forget to "test" meeting activities with your internal team when you haven't run something similar before.

We playtest games for all of the reasons it’s a good idea to playtest making activities.

5. Don't forget to give people choices about how to contribute --and if they have a suggestion for changing an activity, try to roll with it, at least sometimes.

I was good about this at the beginning, but when we got new teammates it was easy to forget to check in with them and allow them choice. People will be more creative if they feel like you aren’t steamrolling them with a plan.

6. Don't participate in all of the generative activities unless the content touches on your expertise.

One, because the cognitive load of facilitating means you probably won’t be very creative. Two, you may not have the know-how to generate good concepts until you learn more about the subject matter. Consider coming prepared with a couple examples at the beginning of each activity, or participating for the first minute or two, to level-set what the concepts or artifacts should look like.

Happy codesigning!

Elaine

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Weekly Report

Weekly Report Marcio Vilas Boas

Week 1

This week we were introduced to the brief along with what genres were available for us to develop a game, after the class voted on some of the ones they were the most interested in, the genres that came out on top were Racing and Platformer. Personally I was not very interested in making a racing game because of how much less room for creativity there is, however we as a group still came up with a few ideas for both genres. Here are the concepts we came up with :

1. You play as a slime who travels by flinging themselves across platforms to travel and can turn into different shapes to complete tasks

2. A game where typing is the main gimmick

3. A snail racing game where we can give the snails jetpacks and cool engines and stuff.

4. Pirate exploring a ship but you are a ghost and stepping into the moonlight allows you to interact with the environment differently

5. A game where you switch bodies with a companion

6. Play as a witch who unlocks different forms to get through puzzles

7. A platformer where you use an arsenal of explosives to blast yourselves to different platforms

8. A Paint style game where you have to use a paint gun to find platforms and different areas to help you get across the level

9. Thief platformer

10. Using time to effect the map in one way or another

We then as a group, created a poll and voted which of those concepts we liked the most so that we could start doing some of the development work for the project. The concept that we chose was the Thief Platformer (I also voted for this one), and we were all pretty happy with this. I was looking forward to working on this project because Enemies and AI were aspects that always put me off making games but I was ready to give them another chance. Since the concept is pretty simple it should be fairly easy to develop it in various ways like the narrative of the game and the characters.

Week 2

This week we started some of the early development work like deciding the name of the game as well as refining the original concept so that our game would have a core identity that we can all get behind. We chose a name for our playable which was Terry and we came up with this name from a play on the Tom and Jerry show. The group also had the idea to make the game in mostly black and white so that it would have a noir aesthetic and I quite liked the idea, mostly because I wasn't too worried about the visuals of the game since I should focus on coming with some simple scripts for the game, however that's not to say that I wouldn't contribute to the game with ideas since this was a project that I was looking forward to work on.

We also talked about how it would be interesting to make a game that takes place inside of a casino but since it's at night we could have it somewhat empty in terms of the population but we could add security guards to patrol around and spot the player if they are not sneaky enough.

Week 3

This week we assigned people to different roles in the group, so that each member could start on developing some aspects of the game and we also had the grey box testing session coming up, so we used that as our first milestone goal. Me and Harry were programmers so it was logical that we would work on creating various scripts for the game, Tom and Will would work on the Environment of the game and finally Jay would work on the UI elements of the game.

Since Me and Harry were in charge of programmers we decided to split some of the tasks between us so that it would be easier to cover more ground and we could speed up some of the development.I volunteered to work on the Enemy AI, and Harry was happy to work on the character controller. Early into development and because we had set our first milestone goal, I believe that it's better to have more scripts that are not as refined than less scripts that are more refined, this is because those scripts will probably be changed in some capacity anyways and the more ground we can cover, the quicker we can get an early build of the game.

Week 4

This week I started to work on some of the scripts to be used in the greybox version of the game. Since I was new to developing Enemies in a 3D game, I started by doing some research on what sorts of things I should have in the scripts of those Game Objects. Once thing I did notice was that there were a couple of ways to go about creating Enemies for the game since you can have them going on patrols which could be done using the Nav Mesh Agent in Unity or I could create a script that sent the Enemy on specific patrol points.

I chose to have a look at the Nav Mesh Agent because it sounded more interesting.

Week 5

This week I decided to go back to the drawing board with the Enemy Guard script because I was having trouble making the Nav Mesh Agent work since it was quite difficult to understand and it was not the easiest or most flexible way to create Enemies, so instead i'll do some research on other way to create Enemies that I can use, preferably with the ability to plan out their patrol route in the scene. Since we have to present a greybox prototype next week, it's better to start from the beginning than try to fix a script that is causing issues. Also I worked on a few scripts that were not related to the AI like for stuff like an outro scene script to help the player end the game so it would trigger an outro scene that thanked the player for testing our game

and a main menu to bind everything together for the prototype, most just making some of the UI assets that Jay made have the ability to load the game. the player for testing our game.

Week 6

This week it was grey box testing week, meaning that we had to show a prototype to the class and we were able to see other peoples progress as well. We had different class members come and try our game and there was also a questionnaire that we made to get people’s feedback after they played the game so we could get a sense of what ideas were working and which ones were not. The questionnaire covered a lot of room since in terms of what types of questions we had, but the ones that I was looking out for were if there were any mechanics people would like to see and how well did they think the game played out. This is because these were the aspects of the game that I could improve. OHH and bugs, those are very important too!

Overall we got pretty good feedback and this told us that we were moving in the right, we now needed to start working on what would be the final version of the game, and we had a lot of work to do.

Week 7

This week I figured, since we now had to start developing work for what would be the final build of the game, I would once again start the Enemy script from the beginning, this is because there were a couple of issues that I had with the script that I used in the grey box prototype, being that the script only made the Enemy move and didn't really punish the player for getting caught, it would mostly chase the player for a while and then once the player left its field of view it would go back to patrolling. The other issue was that it was really awkward to work with it and trying to plot its patrol route was a lot harder than it should be.

The new script that I develop should be able to have a really flexible script in order to allow me to tweek number for the guard like view distance and walking speed, as well as allow me to very easily assign him a patrol route or rather the beginning of one because I can then turn it into a prefab and each guard can have their own unique patrol routes. I also want to add a light to the guard to make it look like they are using flashlight and so that the player knows where the guards are looking at. If the Player gets caught in that light it would be nice if it turned red, and maybe there should even be a little bit of time for the player to not get caught straight away so they can quickly get away.

Weeks 8 - 12

These weeks were tough because of the Covid-19 Pandemic, it meant that our development took a bit of a hit since we had to stop working on it for a couple of weeks. We as a group were working out ways to solve this issue but early on people were moving places and preparing to initiate lockdown. This also meant that most of us lost access to the resources that we had at University and made it very hard to work on the game, especially me since I was a programmer but I heavily relied on the University computers to code.

Another reason why we held off on working on the game was because we were waiting for more information from the university in terms of what would happen to the modules, and was going to happen to our learning.

Eventually we got some information and Microsoft Teams was set up for our lectures to take place in. The main issue for me was still that my home computer was not equipped to handle Unity and so I would need to figure something out in order to finish the development work. We as a group started meeting in Discord calls to continue working on different aspects of the game.

Weeks 13-15

Since I was trying to figure out what I supposed to do with my situation of not being able to work on the game, I figured that i could shift my focus on starting to put together some of the documentation we needed for the game, collecting bits and pieces he had already done but putting them all together into one document as well as writing in more detail about our game. I wrote different things like the overview for our game, talked about some of the references that we used, wrote about parts of the game like starting out, what we were trying to convey to the player with the UI. I also Went over some of the mechanics in our game and also wrote a little about the challenges of importance.

As for the assets list I figured that this was something that would be better to do towards the end of development because we could put in there all the things we worked on. I also grabbed different parts of our Agile Documentation Plan and put it together like the Early Top Ten, Risk Assessment and User Stories.

Basically because I couldn't program I still tried to make myself useful by helping my group in other ways since lockdown was hard for us all.

Week 16

I was able to solve my computer issues by upgrading a couple of parts of my PC and so now I'm able to run Unity on my computer, it works well enough for what I have to do and so it's great that I can go back to making scripts for the game. This week I started off by revisiting the ideas that I had and trying to make them work. I also planned out other parts of the game that needed to be done, not necessarily the big mechanics but rather smaller things like collectables and planning when to work on polishing the game from different ends. I was able to create a script that I was happy with that contained all of the concepts I needed. For example I added a gizmos to show me in the editor the Guard Patrol Path and it was made in a way that I could add these points in the level and create a patrol route. The guards also had a view distance and I made it into a public float because we kept adjusting it so that it would feel fair to the player since nobody wants to get randomly caught. I also swapped out the capsule models that I was using for a better one of a cat, and the game really felt like it was coming together.

Week 17

This week I worked on the Spotlight Puzzle section of our game. Our game, despite taking place all in the same level, it’s divided into 4 sub sections, the last one there is a platforming puzzle where the player has to figure out the rhythm at which the spotlights are changing so he can safely make his way across without getting caught. This was really fun to work on because I also got Harry to help me with a few things but we essentially took parts of the guard script that would spot the player using a light and created a coroutine that would make the lights be On and Off. Then we tested it a few times to see if there was enough time for the player to complete this puzzle and tweaked some numbers until we were satisfied.

Week 18

This week I worked on a lot of much smaller scripts but these were very important to the game, starting with a Minimap. We as a group decided it would be a great idea if we had a minimap for the player to see the level from a different perspective so that they would feel like they had an advantage over the enemy guards. This was pretty easy to set up since it was a camera on top of the player that would follow him and then I took that camera and made it into a rendered texture that would display in the UI.

The other Scripts I worked on were collectables. I started off by taking an old reliable collectable script that I have used in the previous year and semester and modified it a little bit to suit our game. Because we had 3 types of collectables and all of them were displayed in the UI I figured that the easiest way would be to have 3 separate scripts, one for each collectable, and there is also a matching script that would update the score in the UI. For a little bit of polish, I also made the Diamonds rotate since they have a similar role like the stars in a Mario Game, specifically 64. I also added audio clips to them so that when the player would pick them up, it plays a little sound.

Finally I added a couple of things to the Main Menu and the Intro Info menu like music that my group picked to add more polish to the game and not make it sound super empty.

Week 19

This is the final week at pretty much everything that I set out to do is done. The only things left are a few more polishing bits here and there and making sure everything works as it should to make sure we don't have any surprises.

Looking back on this project, it's probably the most ambitious project I worked on but I think it we as group did a good job, and it only came out this way because we are able to work as a group and we were a group of people that all wanted to work with each other, which meant we kept bouncing off ideas from each other and exchanging feedback. I felt like I was a little bit better as a programmer by the end but not only that, but also as a Game Designer, this is because even if you are only a programmer, you are always designing a game.

0 notes

Text

A Virtual Experience That Made A Real Difference [part I]

War. One of the most popular and never depleted themes accompanying our widely understood (pop)culture. On the pages of fantasy books, it brought wealth and glory to victorious heroes. In real life however …

War is ugly and it mostly brought and still brings suffering and misery to (almost) all involved. But always, no matter if real or fictional, revived from the past or imagined in a distant future, war brings change. For us, fortunately, the war was virtual. But the change it brought was as real as it gets.

Back in 2014 we released »This War of Mine« – an »indie game« allowing players to experience a simulation of what it is like to be a civilian in a city torn by military conflict. It became a game changer for us. Not only because of the overall sales or critical acclaim, which were more than satisfying, but first and foremost because of the impact it created. It simply made people care. Not only about gameplay but also about the subject it touched. And for us it proved that games can evoke empathy and bring experiences that shouldn’t just be applied to a fun/not fun scale but rather rated, based on their overall impact.

From the publishing point of view, This War of Mine, being a somewhat niche survival simulator, allowed us to break through to the so-called »mainstream«, changing the way we think about advertising and game-focused communication as a whole.

»The Shelter« (Concept Development)

The first rough version of the game differed a lot from what you know as This War of Mine. It wasn’t even based on war as such. What welcomed you in the initial prototype was a post-apocalyptic wasteland and a half-destroyed bunker serving as a shelter for a group of anonymous survivors. So, »Shelter« became our internal codename for the game, that we used for a significant period of the development process. Visually, it was cool. Even as a basic prototype, we kind of liked how it looked. But emotionally… well, it just wasn’t enough. It lacked something. Even though all of the elements were kind of ok, the sum of them did not work for us. If we wanted to make it stand out from the crowd, we had to bring it to another level. The question was how? We had »the shelter« so the main question was who lived in it. Grzegorz, our CEO, suggested that it should be victims of war – regular people suffering from the conflict that broke out around them. That concept clicked with the team as it gave the missing layer to the game. We felt we could build upon.

What came after was basically a lot of research. A lot. Inspiration came from multiple articles, history we knew from school, as well as from stories told by our parents and grandparents. Being a Pole made the process a bit easier, as we could not complain about the lack of source material. History gave us much, and current news did the rest. Unfortunately, you do not have to try very hard to find »fresh« stories about conflicts affecting modern societies.

After few months of intense work, we landed with a new prototype. One much closer to the final shape of the game. Sure, it needed a lot of polishing – but it worked! At this point we felt we had something truly special. Something that, once you sucked your teeth into it, stuck with you. That became both a curse and a blessing. You obviously had to play it to realize its potential. Not having the track record nor established franchise, we had to build the buzz and interest way before the game appeared on digital shelves of Steam and other distribution platforms.

Shaping the Brand

The common perception is that to succeed you have to be innovative. Break the rules, they say, find your way. The truth is that »new« means difficult. People are afraid of new. They mostly prefer »same old« as predictable, safe and measurable. This is why, amongst a few other reasons, the AAA market is dominated by long running franchises. Investing a lot of money, you crave for as much predictability as possible. And new is far from being predictable. It can pay off, but there is no guarantee of that. With no benchmarks, no historical data, it basically is a bungee jump. On a freshly unpacked rope. So, we jumped. Making the knots in mid-air.

An early prototype of This War of Mine, internally codenamed “The Shelter”.

At this point we knew we had a good game, but we were the only ones with that knowledge. And that is the issue with every new brand/product appearing on the market. You have to build its perception from scratch. What is it? What does it offer? And first and foremost – why the hell should people care? You need an answer. You need a solid brand. Branding is mostly about building a well-defined, coherent presence on the market. Creating a perception and then preferably a purchase intent by associating particular feelings and connotations with your product, service or whatever you have to offer. In our case – a game. There are multiple methods of constructing a strong brand but no matter which path you choose, one thing stays invariable – you have to be relatable. To find something people can easily understand and, in a perfect scenario, have an opinion about. If that opinion is good or bad, that is secondary as sometimes negative feelings can work in your favour as well.

We had a war-themed game and »war« as such was at that time (and honestly not much has changed since then) a commodity in gaming. There were and are so many titles based around conflicts. Modern, historical, sci-fi, you name it. Just check the Steam tags. You are going to get hundreds of results for »war« alone, not to mention all the variations. That meant that the market was cluttered, but also full of potential. Especially considering the fact that the majority of these games shared a somewhat similar and slightly clichéd perspective. No matter the platform or genre, they usually allowed you as a player to embody a superhuman protagonist, running and gunning (alternatively moving units), trying to meet objectives that were different interpretations of winning by destruction. »Action & confrontation« were the core that everything was built around. No empathy involved. Not much of a reflection either (besides few gems like Ubisoft’s »Valiant Hearts: The Great War« or »Spec Ops: The Line« by Yager Interactive).

We decided to use that trend as a springboard for our communication strategy. This War of Mine was to be the »rebel« – questioning the well-established status quo by introducing gamers to a new perspective on war. A strong idea, as we felt, but an easy one to implement. To succeed we had to use all the means at hand to underline our dissidence and prove its value.

Keeping it Short

What made the process of bringing the initial strategy to life more difficult was the fact that English is not our native language. The struggle started with the game’s title. The first version we had had was War of Mine and honestly we were quite happy with it, till one of our English-speaking colleagues asked if we actually had »mines« in our game? And if miners literally fought each other? The answer was »no«. So, we had to iterate. The funny part is that what helped was Guns N’ Roses and their song »Sweet Child O’Mine«. Take that, all you teachers dissing our music tastes in the 90s!

After we had adjusted the title, it definitely worked better. The structure itself was catchy and it stood out among the other titles. To make things even, better it was descriptive and pulled all the right strings. »I am the game about war« it was saying, »but with a personal perspective«. Having this part laid out, we moved to the tagline. First of all, we felt it could become handy as part of planned activities and secondly, being able to enclose your whole premise in a short sentence organizes your communication and helps with the prioritization of what and how to say it. A good tagline should do for your communication what a good punchline does for a joke. Basically sum it up, but in a smart way. Being simple and being obvious are not the same things. We wanted people to easily understand what This War of Mine was and intrigue them a bit. As David Ogilvy (note: a former British advertising tycoon) once said »You can’t bore people into buying your product«.

We wrote a whole bunch of proposals. Some were too long (»In war there are those who fight and those who try to survive«) or too obvious. It took us a while but we ended up with: »In war, not everyone is a soldier«. It was memorable, had kind of a melody to it and most importantly, provided the shift of perspective we craved for. Also, you could easily fit it on the key visuals and that is always helpful.

The Value of Consistency

Having the whole foundation laid out, it was crucial for us to maintain a coherent tonality. We wanted our campaign to be recognizable. Remember, that having no track record, we had to build the game’s perception from scratch. Seeing the ad for the next »Call of Duty« you know what to expect. Buying the game from Paradox, you also can predict what it would offer in terms of experience. Encountering This War of Mine, you knew close to nothing, so establishing its’ identity was crucial. We wanted people to get more and more familiar with our game every time they encountered one of our marketing assets, so after some time they would be able to recognize This War of Mine on the spot. To achieve that, all the pieces, while not repetitive, had to have the same denominator – the premise laid out in the initial strategy. We not only had to maintain consistent aesthetics but also to focus on key features and values specific for our game. We decided that each and every piece we were about to produce had to be

– Serious – there was no space for jokes or winks. No breaking of the fourth wall. We were aware that we were touching serious matter, so we wanted to act respectfully.

– Non-military – This War of Mine was all about civilians. And we wanted to maintain that perspective all the time as this was one of the differentiators you could notice on the spot.

– Apolitical – while politics are highly subjective, human consequences are universal. Getting into politics you can way to easily divide people and trigger unnecessary conflicts. That was not our goal. We wanted to create and promote a human-centric experience people could relate to no matter what their views or beliefs.

– Insightfulness & humanism (two in one basically) – we wanted you, as a player, to identify and immerse. That was an important part of the experience which our game offered and we had to translate it into marketing, not losing anything in the process.

With that mainframe we were able to develop a sort of »language« that we tried to maintain for the whole campaign. It paid off, as every time we released a new piece of content (no matter the medium or format) it added to the overall perception of our game. With every release we stood out a bit more as people got a stronger and clearer image of what our game was and what it was not.

»Gamers just Wanna Have Fun«

Of course, sometimes being coherent meant we had to say »NO« to our gamers, and that is never easy. Especially when you have a committed and highly engaged community. For example, sometime after the release we started to receive requests for a zombie mode. It is understandable as »This War of Mine« has all the elements making it the perfect candidate for that sort of conversion. It is a survival game after all, with people crumped in half-destroyed buildings, trying to survive as long as possible. That’s something half of the zombie flicks are based on. But we did not want to do that as we strongly felt it would blur the identity of the game we had worked so hard on. Fortunately people understood our approach and respected our decision. The identity we created, while well-defined, was grim and quite far from what gamers are usually used to. That raised quite obvious questions about the »fun factor« of our game. But as Pawel – one of our writers – said while interviewed by Kotaku, with This War of Mine we never aimed at fun but rather a meaningful experience. We were ready to sacrifice what was necessary to maintain the big idea that fuelled the game. »Weren’t you scared?« , you may ask. Of course we were. But that was the only reasonable solution. There was no middle ground there if we were to achieve what we aimed for. I still meet people telling me that This War of Mine is their favourite game… they will never ever play again. And that is OK. Some people replay it multiple times. Some don’t. But they seldomly forget the experience they had with the game.

Putting the Cogs into Motion

Being indie meant that we had astrictly limited marketing budget, so our campaign relied mostly on widely understood digital media and key gaming events coverage. »Owned« and »earned« channels were crucial as we could afford only so much when it came to paid activities. Basically, we divided most of our attention between video production/distribution, social media presence, PR/e-PR activities and event coverage. Everything else followed but considering our headcount and the scale of the overall marketing investment, we couldn’t add much on top of these four pillars.

Video Marketing

Limited budget meant limited range of available touchpoints.

Video became the backbone of our production as the most appealing and most willingly consumed type of content at the time (and nowadays as well). It is no secret that game marketing heavily relies on videos. Trailers, »let’s plays«, »dev diaries«, you name it. Having that in mind, we planned all the key points in our campaign around some type of video content. Obviously we could not afford high fidelity, fully fledged cinematic trailers to which people have been accustomed by top tier AAA publishers, but a good idea works even when written on a napkin, as we believed. Over two years we released over a dozen if not more videos but few of them are especially worth mentioning. The announcement trailer aimed at introducing people to the core premise of the game. It was all about the new perspective on war. As it was the first one, we wanted to use a little trick basing on what our viewers were accustomed to. The idea was to open as if we had the next action-focused shooter and then make the shift introducing the civilians’ perspective. That way we could gain the necessary attention and present our idea in a clear and efficient manner. Simple as it was, it worked brilliantly. We didn’t show the gameplay, or even say what the genre was. The premise of the game proved to be enough to spark the conversation.

We introduced gameplay much later on in the campaign but even when our communication became much more gameplay-oriented, we stuck to the tonality and all the strategic assumptions. The stories we were telling and the features we were revealing were new every time but at the same time each video was expanding on the »civilians in a time of war« concept. No exceptions. Preparing our first gameplay trailer we decided to use Polish song, titled »Zegarmistrz wiatła Purpurowy« as a background to the story we were to tell. We were concerned about whether it’s gonna work, considering the fact that most of our audience doesn’t know the language, but finally we had decided that the emotional package it carries is language-neutral and should work universally. The reception of the video proved us right. The funny part is that our video enhanced the popularity of the song abroad and right now you can find a lot of comments on Youtube by people who actually found the song because of our trailer.

Another video, which we consider to be a milestone, happened not long before the release of the game. Some time into the campaign we received a message from Emir – a survivor of the siege of Sarajevo – who complimented the game and compared it to his own personal experiences. Fascinated by his story, we invited him to share it with us, and he happened to be kind enough to accept the invitation. Shortly afterwards, he visited us in Warsaw where we taped a video together that later, supplemented with elements of gameplay, became the launch trailer. The lesson here is that sometimes the universe works in your favour and gives you opportunities to learn, to create and to enhance whatever you do. What is crucial is to push all you have to make each and every one of these opportunities count. Not always will everything work but once it does – it does for real.

Patryk Grzeszczuk

is Marketing Director at 11 bit Studios,

focusing on game marketing and

digital communication

The post A Virtual Experience That Made A Real Difference [part I] appeared first on Making Games.

A Virtual Experience That Made A Real Difference [part I] published first on https://thetruthspypage.tumblr.com/

0 notes

Text

How the Iconic Wipeout Series Was Born

From Playstation Blog USA

“It’s only really many years later when you have the benefit of hindsight that you look at the idea, the art direction, the soundtrack, the platform… and it’s all just perfect timing. Those moments don’t come along very often.” – Nick Burcombe, co-creator, WipEout (1995)

WipEout hit 1995 with the force of an earthquake. Its sci-fi vision of armed anti-grav craft battling it out at 1,2000kph for gold and glory on twisting, vertigo-inducing race tracks couldn’t have been further removed from the quintessentially English pub in which it was conceived. Yet it felt perfectly in sync with the world it roared into like a supercharged sci-fi colossus.