#Dividends of democracy

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

The earnings of the ultra-rich are literally unearned. This isn’t a value judgment: it’s the US tax agency’s term for money made through “investment-type income such as taxable interest, ordinary dividends and capital gain distributions”. While Astor and Rockefeller surely followed the wealth-maximising maxim of buy low, sell high, and put money in trusts, charities and other vehicles to minimise taxation, we’ve seen this logic taken to the next level, without policy changes to correct for it. Most of us pay tax on our incomes at double-digit rates; if we’re fortunate enough to own assets, we pay tax on the profits when we sell them. Billionaires, on the other hand, “can borrow against their growing investments year after year without owing a dime in taxes, allowing them to pay lower tax rates on their income than ordinary Americans pay on theirs”. That statement doesn’t come from Bernie Sanders, by the way, but from the achingly centrist White House, which in 2022 proposed a 20% minimum tax on households worth more than $100m. It went nowhere, in part because its subjects so strongly opposed it. The impending arrival of the trillionaire signals another step backwards in the fight for a more balanced economy and healthier democracy. The billionaire class, after all, skews the balance of power in the marketplace, in politics and in society. Its members own newspapers that shape public opinion. They donate to politicians who pass the laws that they want. According to one study, 11% of the world’s billionaires have held or sought political office, with the rate of “billionaire participation” in autocracies hitting an astounding 29%. Another study shows they tend to lean to the right: positions that typically help them keep their own wealth, and that of their peers, intact.

140 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tax Time!

We filed our taxes on Tuesday, once again with the help of a professional (thank goodness).

As part of the tax prep package we receive a year-over-year comparison of 2022 vs 2023.

2022 was the last year for which I was compensated as a full time employee, in 2023 I did some consulting for most of the year before briefly returning to full time work in November. Not surprisingly, my Adjusted Gross Income (AGI) declined by a whopping 91%.

In 2022 I was in the 37% tax bracket and my effective tax (the ratio of the tax I paid to my AGI) was 33.3%. In 2023 I slid to the 24% tax bracket and my effective tax was a lowly 11.5%.

Why was my effective tax rate so low? Well for starters, a significant part of my income came from qualified dividends which are taxed at a lower rate. I was also able to itemize deductions so I got a break on my home mortgage interest expense.

I'm sharing this with you in hopes that you will resist being drawn into the latest effort to distract voters with the latest social issue hysteria while rich people continue to protect preferential tax treatment like capital gains and home interest deduction.

I guarantee that continuing the current concentration of wealth in this country is a much greater risk to our democracy than drag queens, gender neutral bathrooms and unfettered access to reproductive healthcare for women.

66 notes

·

View notes

Text

In Tale of Two Pegasi, I said:

Socializing capital is much harder. Capital income is not rent. Paying land income does not incentivize the creation of more land, but paying capital income does incentivize the creation of more capital. [...] It’s clear that capital differs from land in an important way. If you tax land income at a rate of 100%, the amount of land in the world will remain the same. If you tax capital income at a rate of 100%, society would soon find itself with much less capital. Land cannot be created, so giving money to its owners does not incentivize the creation of new land. Giving money to owners of capital and labor, however, does incentivize the creation of new capital and labor. So the solution for land does not work as a solution for capital. There must be an incentive to invest money into profitable firms rather than spending it on consumption. The task for the wannabe socialist then, is to find a way to create a more equal distribution of capital ownership while preserving this incentive.”

I mention one of the simplest and oldest solutions to the problem of the distribution of capital ownership: worker co-operatives. After investigating the literature on co-operatives, I don’t think they serve as a sufficient solution. Here’s why:

A co-operative is an enterprise where the workers and the owners are the same people. Each individual contributes their labor-power to the firm, as well as an equal share of the firm’s capital. Capital income is thus distributed evenly across the firm’s members, rather than accruing to distant capitalists. Let’s assume the following co-operative into existence: one with one hundred employees and ten million dollars worth of capital. Each employee provides 50,000 dollars worth of labor a year, and owns a share of the company equal to 100,000 dollars, paying some yearly dividend, which the firm votes on whether to reinvest or to distribute as income.

If the firm is considering hiring a new worker, a dilemma suddenly arises: Where does the new worker’s share come from? If the firm chooses the first horn of the dilemma, it gives the new worker an equal share of the firm’s capital, meaning that now each of the 101 employees has a share worth 99,009.90. Each employee lost a thousand dollars in order to hire this new employee. So the firm is incentivized not to hire new workers, even if it would increase the total revenue of the firm, because it would dilute the capital share of each pre-existing member of the co-operative. This is not a problem of democracy mind you. The issue is that the workers are required to give away something valuable for free. It’s the same issue as taxing capital income at 100%. Capital is not being priced, so it’s not being allocated effectively. Its owner can only ever either give it away for free, or keep it for themselves, so they will always do the latter unless taken by a fit of altruism. Jaroslav Vanek is pretty confident that this “never-employ force” was responsible for the chronic extremely high unemployment rate in Yugoslavia, which had an economy consisting of worker co-operatives. I think he is probably right.

The second horn of the dilemma is if the co-operative tries to price capital, and says, fine, we’re not giving away capital for free. From now on, new members must buy their share of capital. This is how Mondragon, the largest and most successful co-operative in the world, operates. Here is how the system is described in “Making Mondragon”:

Neither members nor outsiders own stock in any Mondragon cooperative. Rather a cooperative is financed by members’ contributions and entry fees at level specified by the governing council [elected management board] and approved by the members. It is as if members are lending money to the firm. Each member thereby has a capital account with the firm in his or her name. Members’ shares of profits are put into their accounts each year, and interest on their capital accounts is paid to the members semi-annually in cash. […] Members share in the remaining profits in proportion to hours worked and pay level. […] From 1966 to the present, all shares in profits have gone into members’ capital accounts. […] Those unfamiliar with accounting terminology might assume that a member’s capital account consists of money deposited for the member in a savings bank or credit union […]. On the contrary, capital accounts involve paper transactions between the members and the firm. Real money is, of course, involved because management is obligated to manage the cooperative with sufficient skill and prudence so that the firm can meet its financial obligations to members if they leave the firm or retire. In practice, however, the financial contributions of members are not segregated from other funds but are used for general business expenses.

A similar system is in place in most other successful co-operatives. In the worker-owned pickle company Real Pickles, each employee has to buy a whopping 6,000 dollar membership share to join the co-operative. The problems with this horn are obvious. It’s no surprise that this system of corporate governance has not seen much success. Most unemployed people looking for work don’t have 6,000 dollars to spend. And the ones that do would be much wiser to invest that money in a different firm, to reduce risk. Worse still, the member-owner cannot sell their share until after they leave the company. They can’t just sell it on a secondary market and use the money gained for consumption like any other stockholder can. The second horn, if scaled up to a whole economy, would be nothing more than just capitalism again, except people are forbidden from buying shares in any company unless they work for said company, in which case buying a share is now mandatory. There is no benefit to this system whatsoever to anybody.

Except for this: management in worker co-operatives is elected by the workers, rather than by shareholders, meaning that the firm is run in the interest of the workers rather than the capitalists. In the spherical cow textbook economic model, this shouldn’t make any difference at all, because in the spherical cow world labor and capital are on entirely equal footing. In the real world however, the capitalists hold an enormous amount of market power that the workers don’t have. It's very easy to switch investments if you don’t like the returns a firm is giving you. It’s much harder to switch jobs when you don’t like how your boss is treating you. Selling labor has much much higher transaction costs. There is clearly an enormous advantage in providing management rights to those who provide labor to the firm rather than those who provide capital, even as a social-democratic reform in a capitalist society. The capital market could look the same as it does now, except all shares of companies would be non-controlling shares. This would accomplish the same things unions accomplish, but more elegantly. The workers would no longer even need to bargain for better conditions and pay. They could make the decision themselves, democratically, if doing so was in their interest. Also, economic profit and schumpeterian rents exist, and in a labor managed firm those rents would go to the workers, which is Good For Utility. This wouldn’t be socialism, but I think it would be an improvement over the current state of things.

26 notes

·

View notes

Note

If the workers themselves do not directly control the means of production, such as the land and the machines used to produce food and other machines, then it is not a communist society.

If the state does not directly control the means of production, then it is not a socialist society.

If neither the state nor the workers directly own the means of production, but instead the means of production are owned by business owners and share holders, then you have a capitalist society.

These are the basic economic principles that define the difference between socialism, communism, and capitalism.

Now lets look at Nazi economic policy, with key points of interest in bold.

After the Nazis took power, industries were privatized en masse. Several banks, shipyards, railway lines, shipping lines, welfare organizations, and more were privatized. The Nazi government took the stance that enterprises should be in private hands wherever possible. State ownership was to be avoided unless it was absolutely necessary for rearmament or the war effort, and even in those cases "the Reich often insisted on the inclusion in the contract of an option clause according to which the private firm operating the plant was entitled to purchase it." However, the privatization was "applied within a framework of increasing control of the state over the whole economy through regulation and political interference," as laid out in the 1933 Act for the Formation of Compulsory Cartels, which gave the government a role in regulating and controlling the cartels that had been earlier formed in the Weimar Republic under the Cartel Act of 1923. These had mostly regulated themselves from 1923 to 1933.

The month after being appointed Chancellor, Hitler made a personal appeal to German business leaders to help fund the Nazi Party for the crucial months that were to follow. He argued that the experience of Weimar Republic had shown that "'private enterprise cannot be maintained in the age of democracy.' Business was founded above all on the principles of personality and individual leadership. Democracy and liberalism led inevitably to Social Democracy and Communism." In the following weeks, the Nazi Party received contributions from seventeen different business groups, with the largest coming from IG Farben and Deutsche Bank. Many of these businesses continued to support Hitler even during the war and even profited from persecution of the Jews. The most infamous being firms like Krupp, IG Farben, and some large automobile manufacturers. Historian Adam Tooze writes that the leaders of German business were therefore "willing partners in the destruction of political pluralism in Germany." In exchange, owners and managers of German businesses were granted unprecedented powers to control their workforce, collective bargaining was abolished and wages were frozen at a relatively low level. Business profits also rose very rapidly, as did corporate investment.

The Nazis granted millions of marks in credits to private businesses. Many businessmen had friendly relations to the Nazis, most notably with Heinrich Himmler and his Freundeskreis der Wirtschaft. Hitler's administration decreed an October 1937 policy that "dissolved all corporations with a capital under $40,000 and forbade the establishment of new ones with a capital less than $200,000," which swiftly effected the collapse of one-fifth of all small corporations. On July 15, 1933 a law was enacted that imposed compulsory membership in cartels, while by 1934 the Third Reich had mandated a reorganization of all companies and trade associations and formed an alliance with the Nazi regime. Nonetheless, the Nazi regime was able to close most of Germany's stock exchanges, reducing them "from twenty-one to nine in 1935," and "limited the distribution of dividends to 6 percent." By 1936 Germany decreed laws to completely block foreign stock trades by citizens. These moves showed signs of Antisemitism and a move toward a war economy, with the belief that the stock market was being operated by Jews.

From this it is clear to see that Nazi economy does not fit into any of the previous categories of socialist, communist, or capitalist. While the Nazi party started as a greatly capitalist industry, it did eventually move towards more government control, to which it had previously been the antithesis of. However, It also employed Union Busting to stop the expansion of workers rights, much like as occurred in America at the same time, and froze wages, much as America has done these past 20 years. But to say Nazis are socialist, is historically factually incorrect, as many businesses that were privatized continued to thrive unimpeded.

As much as I appreciate your ability to copy and paste from wikipedia, you should know that wikipedia is actually not the definitive source on this issue. It's not like anyone can just go on there and edit it lol. If everything you know comes from wikipedia that explains why you don't know much.

Look, I've already thoroughly responded to all these points and I'm not going to keep having the same argument with people who can only repeat themselves or copy and paste from wikipedia without actually responding to what I say.

You do not understand how "privatization" worked in Nazi Germany but you should do some reading about it. You can read the wikipedia page on the term "Gleichschaltung" to get you started.

Anyway, your privately owned business isn't really privately owned if it has to follow certain rules set by the regime and can be shut down by them if you don't support them or break their rules.

It's historically factual to say the Nazis were socialist because they were and you only having the understanding of the different economic systems that don't go any deeper than a google definition and not knowing how "privatization" worked in Nazi Germany and the fact that you can't discuss this issue if you can't copy/paste your entire argument from wikipedia hardly makes a case against that fact.

Only people who are liars or historically ignorant say the Nazis weren't socialists.

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chapter VI. Fourth Period. — Monopoly

2. — The disasters in labor and the perversion of ideas caused by monopoly.

Like competition, monopoly implies a contradiction in its name and its definition. In fact, since consumption and production are identical things in society, and since selling is synonymous with buying, whoever says privilege of sale or exploitation necessarily says privilege of consumption and purchase: which ends in the denial of both. Hence a prohibition of consumption as well as of production laid by monopoly upon the wage-receivers. Competition was civil war, monopoly is the massacre of the prisoners.

These various propositions are supported by all sorts of evidence, — physical, algebraic, and metaphysical. What I shall add will be only the amplified exposition: their simple announcement demonstrates them.

Every society considered in its economic relations naturally divides itself into capitalists and laborers, employers and wage-receivers, distributed upon a scale whose degrees mark the income of each, whether this income be composed of wages, profit, interest, rent, or dividends.

From this hierarchical distribution of persons and incomes it follows that Say’s principle just referred to: In a nation the net product is equal to the gross product, is no longer true, since, in consequence of monopoly, the selling price is much higher than the cost price. Now, as it is the cost price nevertheless which must pay the selling price, since a nation really has no market but itself, it follows that exchange, and consequently circulation and life, are impossible.

In France, twenty millions of laborers, engaged in all the branches of science, art, and industry, produce everything which is useful to man. Their aggregate annual wages amount, it is estimated, to twenty thousand millions; but, in consequence of the profit (net product and interest) accruing to monopolists, twenty-five thousand millions must be paid for their products. Now, as the nation has no other buyers than its wage-receivers and wage-payers, and as the latter do not pay for the former, and as the selling-price of merchandise is the same for all, it is clear that, to make circulation possible, the laborer would have to pay five for that for which he has received but four. — What is Property: Chapter IV. [17]

This, then, is the reason why wealth and poverty are correlative, inseparable, not only in idea, but in fact; this is the reason why they exist concurrently; this is what justifies the pretension of the wage-receiver that the rich man possesses no more than the poor man, except that of which the latter has been defrauded. After the monopolist has drawn up his account of cost, profit, and interest, the wage-paid consumer draws up his; and he finds that, though promised wages stated in the contract as one hundred, he has really been given but seventy-five. Monopoly, therefore, puts the wage-receivers into bankruptcy, and it is strictly true that it lives upon the spoils.

Six years ago I brought out this frightful contradiction: why has it not been thundered through the press? Why have no teachers of renown warned public opinion? Why have not those who demand political rights for the workingman proclaimed that he is robbed? Why have the economists kept silent? Why?

Our revolutionary democracy is so noisy only because it fears revolutions: but, by ignoring the danger which it dares not look in the face, it succeeds only in increasing it. “We resemble,” says M. Blanqui, “firemen who increase the quantity of steam at the same time that they place weights on the safety-valve.” Victims of monopoly, console yourselves! If your tormentors will not listen, it is because Providence has resolved to strike them: Non audierunt, says the Bible, quia Deus volebat occidere eos.

Sale being unable to fulfil the conditions of monopoly, merchandise accumulates; labor has produced in a year what its wages will not allow it to consume in less than fifteen months: hence it must remain idle one-fourth of the year. But, if it remains idle, it earns nothing: how will it ever buy? And if the monopolist cannot get rid of his products, how will his enterprise endure? Logical impossibility multiplies around the workshop; the facts which translate it are everywhere.

“The hosiers of England,” says Eugene Buret, “had come to the point where they did not eat oftener than every other day. This state of things lasted eighteen months.” And he cites a multitude of similar cases.

But the distressing feature in the spectacle of monopoly’s effects is the sight of the unfortunate workingmen blaming each other for their misery and imagining that by uniting and supporting each other they will prevent the reduction of wages.

“The Irish,” says an observer, “have given a disastrous lesson to the working classes of Great Britain..... They have taught our laborers the fatal secret of confining their needs to the maintenance of animal life alone, and of contenting themselves, like savages, with the minimum of the means of subsistence sufficient to prolong life..... Instructed by this fatal example, yielding partly to necessity, the working classes have lost that laudable pride which led them to furnish their houses properly and to multiply about them the decent conveniences which contribute to happiness.”

I have never read anything more afflicting and more stupid. And what would you have these workingmen do? The Irish came: should they have been massacred? Wages were reduced: should death have been accepted in their stead? Necessity commanded, as you say yourselves. Then followed the interminable hours, disease, deformity, degradation, debasement, and all the signs of industrial slavery: all these calamities are born of monopoly and its sad predecessors, — competition, machinery, and the division of labor: and you blame the Irish!

At other times the workingmen blame their luck, and exhort themselves to patience: this is the counterpart of the thanks which they address to Providence, when labor is abundant and wages are sufficient.

I find in an article published by M. Leon Faucher, in the “Journal des Economistes” (September, 1845), that the English workingmen lost some time ago the habit of combining, which is surely a progressive step on which they are only to be congratulated, but that this improvement in the morale of the workingmen is due especially to their economic instruction.

“It is not upon the manufacturers,” cried a spinner at the meeting in Bolton, “that wages depend. In periods of depression the employers, so to speak, are only the lash with which necessity is armed; and whether they will or no, they have to strike. The regulative principle is the relation of supply to demand; and the employers have not this power.... Let us act prudently, then; let us learn to be resigned to bad luck and to make the most of good luck: by seconding the progress of our industry, we shall be useful not only to ourselves, but to the entire country.” [Applause.]

Very good: well-trained, model workmen, these! What men these spinners must be that they should submit without complaint to the lash of necessity, because the regulative principle of wages is supply and demand! M. Leon Faucher adds with a charming simplicity:

English workingmen are fearless reasoners. Give them a false principle, and they will push it mathematically to absurdity, without stopping or getting frightened, as if they were marching to the triumph of the truth.

For my part, I hope that, in spite of all the efforts of economic propagandism, French workingmen will never become reasoners of such power. Supply and demand, as well as the lash of necessity, has no longer any hold upon their minds. This was the one misery that England lacked: it will not cross the channel.

By the combined effect of division, machinery, net product, and interest, monopoly extends its conquests in an increasing progression; its developments embrace agriculture as well as commerce and industry, and all sorts of products. Everybody knows the phrase of Pliny upon the landed monopoly which determined the fall of Italy, latifundia perdidere Italiam. It is this same monopoly which still impoverishes and renders uninhabitable the Roman Campagna and which forms the vicious circle in which England moves convulsively; it is this monopoly which, established by violence after a war of races, produces all the evils of Ireland, and causes so many trials to O’Connell, powerless, with all his eloquence, to lead his repealers through this labyrinth. Grand sentiments and rhetoric are the worst remedy for social evils: it would be easier for O’Connell to transport Ireland and the Irish from the North Sea to the Australian Ocean than to overthrow with the breath of his harangues the monopoly which holds them in its grasp. General communions and sermons will do no more: if the religious sentiment still alone maintains the morale of the Irish people, it is high time that a little of that profane science, so much disdained by the Church, should come to the aid of the lambs which its crook no longer protects.

The invasion of commerce and industry by monopoly is too well known to make it necessary that I should gather proofs: moreover, of what use is it to argue so much when results speak so loudly? E. Buret’s description of the misery of the working-classes has something fantastic about it, which oppresses and frightens you. There are scenes in which the imagination refuses to believe, in spite of certificates and official reports. Couples all naked, hidden in the back of an unfurnished alcove, with their naked children; entire populations which no longer go to church on Sunday, because they are naked; bodies kept a week before they are buried, because the deceased has left neither a shroud in which to lay him out nor the wherewithal to pay for the coffin and the undertaker (and the bishop enjoys an income of from four to five hundred thousand francs); families heaped up over sewers, living in rooms occupied by pigs, and beginning to rot while yet alive, or dwelling in holes, like Albinoes; octogenarians sleeping naked on bare boards; and the virgin and the prostitute expiring in the same nudity: everywhere despair, consumption, hunger, hunger!.. And this people, which expiates the crimes of its masters, does not rebel! No, by the flames of Nemesis! when a people has no vengeance left, there is no longer any Providence for it.

Exterminations en masse by monopoly have not yet found their poets. Our rhymers, strangers to the things of this world, without bowels for the proletaire, continue to breathe to the moon their melancholy delights. What a subject for meditations, nevertheless, is the miseries engendered by monopoly!

It is Walter Scott who says:

Formerly, though many years since, each villager had his cow and his pig, and his yard around his house. Where a single farmer cultivates today, thirty small farmers lived formerly; so that for one individual, himself alone richer, it is true, than the thirty farmers of old times, there are now twenty-nine wretched day-laborers, without employment for their minds and arms, and whose number is too large by half. The only useful function which they fulfil is to pay, when they can, a rent of sixty shillings a year for the huts in which they dwell. [18]

A modern ballad, quoted by E. Buret, sings the solitude of monopoly:

Le rouet est silencieux dans la vallee: C’en est fait des sentiments de famille. Sur un peu de fumee le vieil aieul Etend ses mains pales; et le foyer vide Est aussi desole que son coeur. [19]

The reports made to parliament rival the novelist and the poet:

The inhabitants of Glensheil, in the neighborhood of the valley of Dundee, were formerly distinguished from all their neighbors by the superiority of their physical qualities. The men were of high stature, robust, active, and courageous; the women comely and graceful. Both sexes possessed an extraordinary taste for poetry and music. Now, alas! a long experience of poverty, prolonged privation of sufficient food and suitable clothing, have profoundly deteriorated this race, once so remarkably fine.

This is a notable instance of the inevitable degradation pointed out by us in the two chapters on division of labor and machinery. And our litterateurs busy themselves with the pretty things of the past, as if the present were not adequate to their genius! The first among them to venture on these infernal paths has created a scandal in the coterie! Cowardly parasites, vile venders of prose and verse, all worthy of the wages of Marsyas! Oh! if your punishment were to last as long as my contempt, you would be forced to believe in the eternity of hell.

Monopoly, which just now seemed to us so well founded in justice, is the more unjust because it not only makes wages illusory, but deceives the workman in the very valuation of his wages by assuming in relation to him a false title, a false capacity.

M. de Sismondi, in his “Studies of Social Economy,” observes somewhere that, when a banker delivers to a merchant bank-notes in exchange for his values, far from giving credit to the merchant, he receives it, on the contrary, from him.

“This credit,” adds M. de Sismondi, “is in truth so short that the merchant scarcely takes the trouble to inquire whether the banker is worthy, especially as the former asks credit instead of granting it.”

So, according to M. de Sismondi, in the issue of bank paper, the functions of the merchant and the banker are inverted: the first is the creditor, and the second is the credited.

Something similar takes place between the monopolist and wage-receiver.

In fact, the workers, like the merchant at the bank, ask to have their labor discounted; in right, the contractor ought to furnish them bonds and security. I will explain myself.

In any exploitation, no matter of what sort, the contractor cannot legitimately claim, in addition to his own personal labor, anything but the IDEA: as for the EXECUTION, the result of the cooperation of numerous laborers, that is an effect of collective power, with which the authors, as free in their action as the chief, can produce nothing which should go to him gratuitously. Now, the question is to ascertain whether the amount of individual wages paid by the contractor is equivalent to the collective effect of which I speak: for, were it otherwise, Say’s axiom, Every product is worth what it costs, would be violated.

“The capitalist,” they say, “has paid the laborers their daily wages at a rate agreed upon; consequently he owes them nothing.” To be accurate, it must be said that he has paid as many times one day’s wage as he has employed laborers, — which is not at all the same thing. For he has paid nothing for that immense power which results from the union of laborers and the convergence and harmony of their efforts; that saving of expense, secured by their formation into a workshop; that multiplication of product, foreseen, it is true, by the capitalist, but realized by free forces. Two hundred grenadiers, working under the direction of an engineer, stood the obelisk upon its base in a few hours; do you think that one man could have accomplished the same task in two hundred days? Nevertheless, on the books of the capitalist, the amount of wages is the same in both cases, because he allots to himself the benefit of the collective power. Now, of two things one: either this is usurpation on his part, or it is error. -What is Property: Chapter III.

To properly exploit the mule-jenny, engineers, builders, clerks, brigades of workingmen and workingwomen of all sorts, have been needed. In the name of their liberty, of their security, of their future, and of the future of their children, these workmen, on engaging to work in the mill, had to make reserves; where are the letters of credit which they have delivered to the employers? Where are the guarantees which they have received? What! millions of men have sold their arms and parted with their liberty without knowing the import of the contract; they have engaged themselves upon the promise of continuous work and adequate reward; they have executed with their hands what the thought of the employers had conceived; they have become, by this collaboration, associates in the enterprise: and when monopoly, unable or unwilling to make further exchanges, suspends its manufacture and leaves these millions of laborers without bread, they are told to be resigned! By the new processes they have lost nine days of their labor out of ten; and for reward they are pointed to the lash of necessity flourished over them! Then, if they refuse to work for lower wages, they are shown that they punish themselves. If they accept the rate offered them, they lose that noble pride, that taste for decent conveniences which constitute the happiness and dignity of the workingman and entitle him to the sympathies of the rich. If they combine to secure an increase of wages, they are thrown into prison! Whereas they ought to prosecute their exploiters in the courts, on them the courts will avenge the violations of liberty of commerce! Victims of monopoly, they will suffer the penalty due to the monopolists! O justice of men, stupid courtesan, how long, under your goddess’s tinsel, will you drink the blood of the slaughtered proletaire?

Monopoly has invaded everything, — land, labor, and the instruments of labor, products and the distribution of pro ducts. Political economy itself has not been able to avoid admitting it.

“You almost always find across your path,” says M. Rossi, “some monopoly. There is scarcely a product that can be regarded as the pure and simple result of labor; accordingly the economic law which proportions price to cost of production is never completely realized. It is a formula which is profoundly modified by the intervention of one or another of the monopolies to which the instruments of production are subordinated. — Course in Political Economy: Volume I., page 143.

M. Rossi holds too high an office to give his language all the precision and exactness which science requires when monopoly is in question. What he so complacently calls a modification of economic formulas is but a long and odious violation of the fundamental laws of labor and exchange. It is in consequence of monopoly that in society, net product being figured over and above gross product, the collective laborer must repurchase his own product at a price higher than that which this product costs him, — which is contradictory and impossible; that the natural balance between production and consumption is destroyed; that the laborer is deceived not only in his settlements, but also as to the amount of his wages; that in his case progress in comfort is changed into an incessant progress in misery: it is by monopoly, in short, that all notions of commutative justice are perverted, and that social economy, instead of the positive science that it is, becomes a veritable utopia.

This disguise of political economy under the influence of monopoly is a fact so remarkable in the history of social ideas that we must not neglect to cite a few instances.

Thus, from the standpoint of monopoly, value is no longer that synthetic conception which serves to express the relation of a special object of utility to the sum total of wealth: monopoly estimating things, not in their relation to society, but in their relation to itself, value loses its social character, and is nothing but a vague, arbitrary, egoistic, and essentially variable thing. Starting with this principle, the monopolist extends the term product to cover all sorts of servitude, and applies the idea of capital to all the frivolous and shameful industries which his passions and vices exploit. The charms of a courtesan, says Say, are so much capital, of which the product follows the general law of values, — namely, supply and demand. Most of the works on political economy are full of such applications. But as prostitution and the state of dependence from which it emanates are condemned by morality, M. Rossi will bid us observe the further fact that political economy, after having modified its formula in consequence of the intervention of monopoly, will have to submit to a new corrective, although its conclusions are in themselves irreproachable. For, he says, political economy has nothing in common with morality: it is for us to accept it, to modify or correct its formulas, whenever our welfare, that of society, and the interests of morality call for it. How many things there are between political economy and truth!

Likewise, the theory of net product, so highly social, progressive, and conservative, has been individualized, if I may say so, by monopoly, and the principle which ought to secure society’s welfare causes its ruin. The monopolist, always striving for the greatest possible net product, no longer acts as a member of society and in the interest of society; he acts with a view to his exclusive interest, whether this interest be contrary to the social interest or not. This change of perspective is the cause to which M. de Sismondi attributes the depopulation of the Roman Campagna. From the comparative researches which he has made regarding the product of the agro romano when in a state of cultivation and its product when left as pasture-land, he has found that the gross product would be twelve times larger in the former case than in the latter; but, as cultivation demands relatively a greater number of hands, he has discovered also that in the former case the net product would be less. This calculation, which did not escape the proprietors, sufficed to confirm them in the habit of leaving their lands uncultivated, and hence the Roman Campagna is uninhabited.

“All parts of the Roman States,” adds M. de Sismondi, “present the same contrast between the memories of their prosperity in the Middle Ages and their present desolation. The town of Ceres, made famous by Renzo da Ceri, who defended by turns Marseilles against Charles V. and Geneva against the Duke of Savoy, is nothing but a solitude. In all the fiefs of the Orsinis and the Colonnes not a soul. From the forests which surround the pretty Lake of Vico the human race has disappeared; and the soldiers with whom the formidable prefect of Vico made Rome tremble so often in the fourteenth century have left no descendants. Castro and Ronciglione are desolated.” — Studies in Political Economy.

In fact, society seeks the greatest possible gross product, and consequently the greatest possible population, because with it gross product and net product are identical. Monopoly, on the contrary, aims steadily at the greatest net product, even though able to obtain it only at the price of the extermination of the human race.

Under this same influence of monopoly, interest on capital, perverted in its idea, has become in turn a principle of death to society. As we have explained it, interest on capital is, on the one hand, the form under which the laborer enjoys his net product, while utilizing it in new creations; on the other, this interest is the material bond of solidarity between producers, viewed from the standpoint of the increase of wealth. Under the first aspect, the aggregate interest paid can never exceed the amount of the capital itself; under the second, interest allows, in addition to reimbursement, a premium as a reward of service rendered. In no case does it imply perpetuity.

But monopoly, confounding the idea of capital, which is attributable only to the creations of human industry, with that of the exploitable material which nature has given us, and which belongs to all, and favored moreover in its usurpation by the anarchical condition of a society in which possession can exist only on condition of being exclusive, sovereign, and perpetual, — monopoly has imagined and laid it down as a principle that capital, like land, animals, and plants, had in itself an activity of its own, which relieved the capitalist of the necessity of contributing anything else to exchange and of taking any part in the labors of the workshop. From this false idea of monopoly has come the Greek name of usury, tokos, as much as to say the child or the increase of capital, which caused Aristotle to perpetrate this witticism: coins beget no children. But the metaphor of the usurers has prevailed over the joke of the Stagyrite; usury, like rent, of which it is an imitation, has been declared a perpetual right; and only very lately, by a half-return to the principle, has it reproduced the idea of redemption.

Such is the meaning of the enigma which has caused so many scandals among theologians and legists, and regarding which the Christian Church has blundered twice, — first, in condemning every sort of interest, and, second, in taking the side of the economists and thus contradicting its old maxims. Usury, or the right of increase, is at once the expression and the condemnation of monopoly; it is the spoliation of labor by organized and legalized capital; of all the economic subversions it is that which most loudly accuses the old society, and whose scandalous persistence would justify an unceremonious and uncompensated dispossession of the entire capitalistic class.

Finally, monopoly, by a sort of instinct of self-preservation, has perverted even the idea of association, as something that might infringe upon it, or, to speak more accurately, has not permitted its birth.

Who could hope today to define what association among men should be? The law distinguishes two species and four varieties of civil societies, and as many commercial societies, from the simple partnership to the joint-stock company. I have read the most respectable commentaries that have been written upon all these forms of association, and I declare that I have found in them but one application of the routine practices of monopoly between two or more partners who unite their capital and their efforts against everything that produces and consumes, that invents and exchanges, that lives and dies. The sine qua non of all these societies is capital, whose presence alone constitutes them and gives them a basis; their object is monopoly, — that is, the exclusion of all other laborers and capitalists, and consequently the negation of social universality so far as persons are concerned.

Thus, according to the definition of the statute, a commercial society which should lay down as a principle the right of any stranger to become a member upon his simple request, and to straightway enjoy the rights and prerogatives of associates and even managers, would no longer be a society; the courts would officially pronounce its dissolution, its nonexistence. So, again, articles of association in which the contracting parties should stipulate no contribution of capital, but, while reserving to each the express right to compete with all, should confine themselves to a reciprocal guarantee of labor and wages, saying nothing of the branch of exploitation, or of capital, or of interest, or of profit and loss, — such articles would seem contradictory in their tenor, as destitute of purpose as of reason, and would be annulled by the judge on the complaint of the first rebellious associate. Covenants thus drawn up could give rise to no judicial action; people calling themselves the associates of everybody would be considered associates of nobody; treatises contemplating guarantee and competition between associates at the same time, without any mention of social capital and without any designation of purpose, would pass for a work of transcendental charlatanism, whose author could readily be sent to a madhouse, provided the magistrates would consent to regard him as only a lunatic.

And yet it is proved, by the most authentic testimony which history and social economy furnish, that humanity has been thrown naked and without capital upon the earth which it cultivates; consequently that it has created and is daily creating all the wealth that exists; that monopoly is only a relative view serving to designate the grade of the laborer, with certain conditions of enjoyment; and that all progress consists, while indefinitely multiplying products, in determining their proportionality, — that is, in organizing labor and comfort by division, machinery, the workshop, education, and competition. On the other hand, it is evident that all the tendencies of humanity, both in its politics and in its civil laws, are towards universalization, — that is, towards a complete transformation of the idea of society as determined by our statutes.

Whence I conclude that articles of association which should regulate, no longer the contribution of the associates, — since each associate, according to the economic theory, is supposed to possess absolutely nothing upon his entrance into society, — but the conditions of labor and exchange, and which should allow access to all who might present themselves, — I conclude, I say, that such articles of association would contain nothing that was not rational and scientific, since they would be the very expression of progress, the organic formula of labor, and since they would reveal, so to speak, humanity to itself by giving it the rudiment of its constitution.

Now, who, among the jurisconsults and economists, has ever approached even within a thousand leagues of this magnificent and yet so simple idea?

“I do not think,” says M. Troplong, “that the spirit of association is called to greater destinies than those which it has accomplished in the past and up to the present time... ; and I confess that I have made no attempt to realize such hopes, which I believe exaggerated.... There are well-defined limits which association should not overstep. No! association is not called upon in France to govern everything. The spontaneous impulse of the individual mind is also a living force in our nation and a cause of its originality....

“The idea of association is not new.... Even among the Romans we see the commercial society appear with all its paraphernalia of monopolies, corners, collusions, combinations, piracy, and venality.... The joint-stock company realizes the civil, commercial, and maritime law of the Middle Ages: at that epoch it was the most active instrument of labor organized in society.... From the middle of the fourteenth century we see societies form by stock subscriptions; and up to the time of Law’s discomfiture, we see their number continually increase.... What! we marvel at the mines, factories, patents, and newspapers owned by stock companies! But two centuries ago such companies owned islands, kingdoms, almost an entire hemisphere. We proclaim it a miracle that hundreds of stock subscribers should group themselves around an enterprise; but as long ago as the fourteenth century the entire city of Florence was in similar silent partnership with a few merchants, who pushed the genius of enterprise as far as possible. Then, if our speculations are bad, if we have been rash, imprudent, or credulous, we torment the legislator with our cavilling complaints; we call upon him for prohibitions and nullifications. In our mania for regulating everything, even that which is already codified; for enchaining everything by texts reviewed, corrected, and added to; for administering everything, even the chances and reverses of commerce, — we cry out, in the midst of so many existing laws: ‘There is still something to do!’”

M. Troplong believes in Providence, but surely he is not its man. He will not discover the formula of association clamored for today by minds disgusted with all the protocols of combination and rapine of which M. Troplong unrolls the picture in his commentary. M. Troplong gets impatient, and rightly, with those who wish to enchain everything in texts of laws; and he himself pretends to enchain the future in a series of fifty articles, in which the wisest mind could not discover a spark of economic science or a shadow of philosophy. In our mania, he cries, for regulating everything, EVEN THAT WHICH IS ALREADY CODIFIED!.... I know nothing more delicious than this stroke, which paints at once the jurisconsult and the economist. After the Code Napoleon, take away the ladder!...

“Fortunately,” M. Troplong continues, “all the projects of change so noisily brought to light in 1837 and 1838 are forgotten today. The conflict of propositions and the anarchy of reformatory opinions have led to negative results. At the same time that the reaction against speculators was effected, the common sense of the public did justice to the numerous official plans of organization, much inferior in wisdom to the existing law, much less in harmony with the usages of commerce, much less liberal, after 1830, than the conceptions of the imperial Council of State! Now order is restored in everything, and the commercial code has preserved its integrity, its excellent integrity. When commerce needs it, it finds, by the side of partnership, temporary partnership, and the joint-stock company, the free silent partnership, tempered only by the prudence of the silent partners and by the provisions of the penal code regarding swindling.” — Troplong: Civil and Commercial Societies: Preface.

What a philosophy is that which rejoices in the miscarriage of reformatory endeavors, and which counts its triumphs by the negative results of the spirit of inquiry! We cannot now enter upon a more fundamental criticism of the civil and commercial societies, which have furnished M. Troplong material for two volumes. We will reserve this subject for the time when, the theory of economic contradictions being finished, we shall have found in their general equation the programme of association, which we shall then publish in contrast with the practice and conceptions of our predecessors.

A word only as to silent partnership.

One might think at first blush that this form of joint-stock company, by its expansive power and by the facility for change which it offers, could be generalized in such a way as to take in an entire nation in all its commercial and industrial relations. But the most superficial examination of the constitution of this society demonstrates very quickly that the sort of enlargement of which it is susceptible, in the matter of the number of stockholders, has nothing in common with the extension of the social bond.

In the first place, like all other commercial societies, it is necessarily limited to a single branch of exploitation: in this respect it is exclusive of all industries foreign to that peculiarly its own. If it were otherwise, it would have changed its nature; it would be a new form of society, whose statutes would regulate, no longer the profits especially, but the distribution of labor and the conditions of exchange; it would be exactly such an association as M. Troplong denies and as the jurisprudence of monopoly excludes.

As for the personal composition of the company, it naturally divides itself into two categories, — the managers and the stockholders. The managers, very few in number, are chosen from the promoters, organizers, and patrons of the enterprise: in truth, they are the only associates. The stockholders, compared with this little government, which administers the society with full power, are a people of taxpayers who, strangers to each other, without influence and without responsibility, have nothing to do with the affair beyond their investments. They are lenders at a premium, not associates.

One can see from this how all the industries of the kingdom could be carried on by such companies, and each citizen, thanks to the facility for multiplying his shares, be interested in all or most of these companies without thereby improving his condition: it might happen even that it would be more and more compromised. For, once more, the stockholder is the beast of burden, the exploitable material of the company: not for him is this society formed. In order that association may be real, he who participates in it must do so, not as a gambler, but as an active factor; he must have a deliberative voice in the council; his name must be expressed or implied in the title of the society; everything regarding him, in short, should be regulated in accordance with equality. But these conditions are precisely those of the organization of labor, which is not taken into consideration by the code; they form the ULTERIOR object of political economy, and consequently are not to be taken for granted, but to be created, and, as such, are radically incompatible with monopoly. [20]

Socialism, in spite of its high-sounding name, has so far been no more fortunate than monopoly in the definition of society: we may even assert that, in all its plans of organization, it has steadily shown itself in this respect a plagiarist of political economy. M. Blanc, whom I have already quoted in discussing competition, and whom we have seen by turns as a partisan of the hierarchical principle, an officious defender of inequality, preaching communism, denying with a stroke of the pen the law of contradiction because he cannot conceive it, aiming above all at power as the final sanction of his system, — M. Blanc offers us again the curious example of a socialist copying political economy without suspecting it, and turning continually in the vicious circle of proprietary routine. M. Blanc really denies the sway of capital; he even denies that capital is equal to labor in production, in which he is in accord with healthy economic theories. But he can not or does not know how to dispense with capital; he takes capital for his point of departure; he appeals to the State for its silent partnership: that is, he gets down on his knees before the capitalists and recognizes the sovereignty of monopoly. Hence the singular contortions of his dialectics. I beg the reader’s pardon for these eternal personalities: but since socialism, as well as political economy, is personified in a certain number of writers, I cannot do otherwise than quote its authors.

“Has or has not capital,” said “La Phalange,” “in so far as it is a faculty in production, the legitimacy of the other productive faculties? If it is illegitimate, its pretensions to a share of the product are illegitimate; it must be excluded; it has no interest to receive: if, on the contrary, it is legitimate, it cannot be legitimately excluded from participation in the profits, in the increase which it has helped to create.”

The question could not be stated more clearly. M. Blanc holds, on the contrary, that it is stated in a very confused manner, which means that it embarrasses him greatly, and that he is much worried to find its meaning.

In the first place, he supposes that he is asked “whether it is equitable to allow the capitalist a share of the profits of production equal to the laborer’s.” To which M. Blanc answers unhesitatingly that that would be unjust. Then follows an outburst of eloquence to establish this injustice.

Now, the phalansterian does not ask whether the share of the capitalist should or should not be equal to the laborer’s; he wishes to know simply whether he is to have a share. And to this M. Blanc makes no reply.

Is it meant, continues M. Blanc, that capital is indispensable to production, like labor itself? Here M. Blanc distinguishes: he grants that capital is indispensable, as labor is, but not to the extent that labor is.

Once again, the phalansterian does not dispute as to quantity, but as to right.

Is it meant — it is still M. Blanc who interrogates — that all capitalists are not idlers? M. Blanc, generous to capitalists who work, asks why so large a share should be given to those who do not work? A flow of eloquence as to the impersonal services of the capitalist and the personal services of the laborer, terminated by an appeal to Providence.

For the third time, you are asked whether the participation of capital in profits is legitimate, since you admit that it is indispensable in production.

At last M. Blanc, who has understood all the time, decides to reply that, if he allows interest to capital, he does so only as a transitional measure and to ease the descent of the capitalists. For the rest, his project leading inevitably to the absorption of private capital in association, it would be folly and an abandonment of principle to do more. M. Blanc, if he had studied his subject, would have needed to say but a single phrase: “I deny capital.”

Thus M. Blanc, — and under his name I include the whole of socialism, — after having, by a first contradiction of the title of his book, “ORGANIZATION OF LABOR,” declared that capital was indispensable in production, and consequently that it should be organized and participate in profits like labor, by a second contradiction rejects capital from organization and refuses to recognize it: by a third contradiction he who laughs at decorations and titles of nobility distributes civic crowns, rewards, and distinctions to such litterateurs inventors, and artists as shall have deserved well of the country; he allows them salaries according to their grades and dignities; all of which is the restoration of capital as really, though not with the same mathematical precision, as interest and net product: by a fourth contradiction M. Blanc establishes this new aristocracy on the principle of equality, — that is, he pretends to vote masterships to equal and free associates, privileges of idleness to laborers, spoliation in short to the despoiled: by a fifth contradiction he rests this equalitarian aristocracy on the basis of a power endowed with great force, — that is, on despotism, another form of monopoly: by a sixth contradiction, after having, by his encouragements to labor and the arts, tried to proportion reward to service, like monopoly, and wages to capacity, like monopoly, he sets himself to eulogize life in common, labor and consumption in common, which does not prevent him from wishing to withdraw from the effects of common indifference, by means of national encouragements taken out of the common product, the grave and serious writers whom common readers do not care for: by a seventh contradiction.... but let us stop at seven, for we should not have finished at seventy-seven.

It is said that M. Blanc, who is now preparing a history of the French Revolution, has begun to seriously study political economy. The first fruit of this study will be, I do not doubt, a repudiation of his pamphlet on “Organization of Labor,” and consequently a change in all his ideas of authority and government. At this price the “History of the French Revolution,” by M. Blanc, will be a truly useful and original work.

All the socialistic sects, without exception, are possessed by the same prejudice; all, unconsciously, inspired by the economic contradiction, have to confess their powerlessness in presence of the necessity of capital; all are waiting, for the realization of their ideas, to hold power and money in their hands. The utopias of socialism in the matter of association make more prominent than ever the truth which we announced at the beginning: There is nothing in socialism which is not found in political economy; and this perpetual plagiarism is the irrevocable condemnation of both. Nowhere is to be seen the dawn of that mother-idea, which springs with so much eclat from the generation of the economic categories, — that the superior formula of association has nothing to do with capital, a matter for individual accounts, but must bear solely upon equilibrium of production, the conditions of exchange, the gradual reduction of cost, the one and only source of the increase of wealth. Instead of determining the relations of industry to industry, of laborer to laborer, of province to province, and of people to people, the socialists dream only of providing themselves with capital, always conceiving the problem of the solidarity of laborers as if it were a question of founding some new institution of monopoly. The world, humanity, capital, industry, business machinery, exist; it is a matter now simply of finding their philosophy, — in other words, of organizing them: and the socialists are in search of capital! Always outside of reality, is it astonishing that they miss it?

Thus M. Blanc asks for State aid and the establishment of national workshops; thus Fourier asked for six million francs, and his followers are still engaged today in collecting that sum; thus the communists place their hope in a revolution which shall give them authority and the treasury, and exhaust themselves in waiting for useless subscriptions. Capital and power, secondary organs in society, are always the gods whom socialism adores: if capital and power did not exist, it would invent them. Through its anxieties about power and capital, socialism has completely overlooked the meaning of its own protests: much more, it has not seen that, in involving itself, as it has done, in the economic routine, it has deprived itself of the very right to protest. It accuses society of antagonism, and through the same antago-nism it goes in pursuit of reform. It asks capital for the poor laborers, as if the misery of laborers did not come from the competition of capitalists as well as from the factitious opposition of labor and capital; as if the question were not today precisely what it was before the creation of capital, — that is, still and always a question of equilibrium; as if, in short, — let us repeat it incessantly, let us repeat it to satiety, — the question were henceforth of something other than a synthesis of all the principles brought to light by civilization, and as if, provided this synthesis, the idea which leads the world, were known, there would be any need of the intervention of capital and the State to make them evident.

Socialism, in deserting criticism to devote itself to decla-mation and utopia and in mingling with political and religious intrigues, has betrayed its mission and misunderstood the character of the century. The revolution of 1830 demoralized us; socialism is making us effeminate. Like political economy, whose contradictions it simply sifts again, socialism is powerless to satisfy the movement of minds: it is henceforth, in those whom it subjugates, only a new prejudice to destroy, and, in those who propagate it, a charlatanism to unmask, the more dangerous because almost always sincere.

#organization#revolution#anarchism#daily posts#communism#anti capitalist#anti capitalism#late stage capitalism#anarchy#anarchists#libraries#leftism#social issues#economy#economics#climate change#anarchy works#environmentalism#environment#solarpunk#anti colonialism#mutual aid#the system of economic contradictions#the philosophy of poverty#volume i#pierre-joseph proudhon#pierre joseph proudhon

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

i love how the self-titled Effective Altruists and cuntbags like musk believe that the “demographic crisis” of the 21st century is like a massive insane problem that we need to solve by farting out babies 24/7, as they said in that recent Kurzgesagt propaganda video they produced

it is capitalism that’s the problem, again. growth for the sake of growth is the ideology of a cancer cell. we ‘grow’ when we produce more, and our investments are based around potential growths rather than what is needed - so when alleged ‘potential’ can’t materialise, the economy collapses

we will be able to produce less when there will be less workers. future spacex neuralink hyperloop tech might soften the blow but won’t be able to change that fact

this is coming towards capitalism like a high-speed train. most executives are essentially wagies visàvis their positions as gods of the world, so systemically cannot respond to a problem more than twenty years ahead of time. but oligarchs like musk and formerly bankman-fried, with their oligarchic status seemingly made permanent (lol), become weird nutters who’ve given themselves messiah complexes about “solving” it. we must increase production always at all costs, so we must increase babies at all costs

growth for the sake of growth is the ideology of a cancer cell. the economy is going to shrink and we must not let this cause a world-eating depression under capitalism. we have to accept that we’re peaking, stop investing resources into growth and start investing resources into efficiency, systemic resilience, and services, and drop dead-weight unsustainable overproduction that’s killing the planet. stop even trying to grow the economy during a period of global decline - the global Very Long Boom and global Baby Boom gave a economic dividend that must be repaid

socialistic economics, redistribution, and economic democracy can let this pressure. we have to do managed decline, work towards working better with less workers and less labour, and support untold masses of pensioners. capitalism simply cannot do this. if under capitalism the economy was recessing massively, but don’t worry, in many years the ageing recession will cease and growth should resume with stability - investment simply will not go towards what is needed to improve life under the status quo and will be hedged until growth resumes, and so nothing good will ever come

that’s why the so-called “effective altruists” and muskists are so bothered about preventing what they see as demographic collapse - should it occur it’ll wreak a huge economic recession, be it slow or as a crash, and lead to a world of impoverished pensioners starving on the street. so their solution is babies at all costs, when instead we could have a world where a period of managed decline spurs reinvestment in what we have, a silver age of planet earth, a global new deal beyond measure. and when the massive wave of pensioners dies, we will have good services and sustainable economics, and enriched communities with fruitful childhoods and good educations, and yeah, we can use our growth potential to not just prevent environmental destruction (capitalism’ll’ve already triggered a lot) but do our level headed best to fix it, become the stewards of Earth that we’re abdicating ourselves as, and fuck it, have enough money to reshape the world into a happy and good place to live a life

but capitalism cannot do that. because capitalism cannot accept decline. because capitalism must have growth at any costs, and will continue to beat the dead horse until the skies darken with soot and until the baby boomers who built the longest boom are left to rot without care or food and their children are enslaved to keep the fires burning. and to bring back the boom times, it must be babies at any cost

footnote: this was mostly about economics but there’s one more angle that would’ve made a bit of a tangent. musk’s side of the coin has a massive, massive misogynistic basis. musk, the individual, is famously a total creep. people with breeding kinks can breathe a sigh of relief because he is not one of you - his is a breeding perversion. he has an obsession with creating as many of his own children as possible and subscribes to the belief that a Man’s worth can be measured with his spawn. and so many of his ilk believe the same. this is how he can have child after child despite obviously not caring for them and doing his duty as a parent - parenting ten children should basically be a full time job. it takes a village: this is a village. and i don’t mean to point fingers, but with his first wife he had a set of twins via ivf and then a set of triplets via ivf, and many more children later, including after the birth of the human person he calls “X Æ A-Xii”, he had a second child with Grimes via surrogacy. this worldview undoubtedly affects his everyday misogyny and transphobia - women’s utility is as utility, trans men do iRrEvErSiBlE dAmAgE to their mere utility, and trans women go against womanhood due to having no utility. he abandoned his own fucking daughter for being trans. creepy, disgusting, indefensible - and this man is one of the gods of our world, enacting his poisonous worldview without oversight

and ragging on cunts like musk isn’t letting the ““effective altruists”” off the hook. their circles, as organisations or just general society, has an oft-reported massive sexism problem. multiple EA members have been accused of creating a toxic atmosphere hostile to women, of sexual misconduct, and of grooming with intention to form poly relationships. an ideology of reducing humans to utility, of stressing population growth, and of getting ants in your pants about demographic crisis does not combine well with latent misogyny and the patriarchal, male near-exclusive echelons of capitalism

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

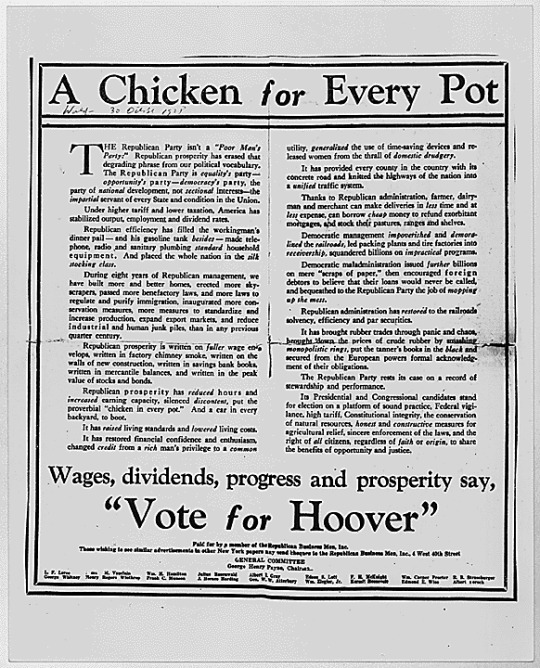

"A Chicken in Every Pot" political ad and rebuttal article in New York Times

Collection HH-HOOVH: Herbert Hoover PapersSeries: Herbert Hoover Papers: Clippings File

This is the advertisement that caused Herbert Hoover's opponents to state that he had promised voters a chicken in every pot and two cars in every garage during the campaign of 1928. During the campaign of 1932, Democrats sought to embarrass the President by recalling his alleged statement. According to an article in the New York Times (10/30/32), Hoover did not make such a statement. The report was based on this ad placed by a local committee -- which only mentions one car!

A Chicken for Every Pot [handwritten] World[?] 30 October 1928 [/handwritten] The Republican Party isn't a [italics] "Poor Man's Party:" [/italics] Republican prosperity has erased that degrading phrase from our political vocabulary. The Republican Party is [italics] equality's [/italics] party -- [italics] opportunity's [/italics] party -- [italics] democracy's [/italics] party, the party of [italics] national [/italics] development, not [italics] sectional [/italics] interests-- the [italics] impartial [/italics] servant of every State and condition in the Union. Under higher tariff and lower taxation, America has stabilized output, employment and dividend rates. Republican efficiency has filled the workingman's dinner pail -- and his gasoline tank [italics] besides [/italics] -- made telephone, radio and sanitary plumbing [italics] standard [/italics] household equipment. And placed the whole nation in the [italics] silk stocking class. [/italics] During eight years of Republican management, we have built more and better homes, erected more skyscrapers, passed more benefactory laws, and more laws to regulate and purify immigration, inaugurated more conservation measures, more measures to standardize and increase production, expand export markets, and reduce industrial and human junk piles, than in any previous quarter century. Republican prosperity is written on [italics] fuller [/italics] wage envelops, written in factory chimney smoke, written on the walls of new construction, written in savings bank books, written in mercantile balances, and written in the peak value of stocks and bonds. Republican prosperity has [italics] reduced [/italics] hours and [italics] increased [/italics] earning capacity, silenced [italics] discontent, [/italics] put the proverbial "chicken in every pot." And a car in every backyard, to boot. It has[italics] raised [/italics] living standards and [italics] lowered [/italics] living costs. It has restored financial confidence and enthusiasm, changed [italics] credit [/italics] from a [italics] rich [/italics] man's privilege to a [italics] common [/italics] utility, [italics] generalized[/italics] the use of time-saving devices and released women from the thrall of [italics] domestic drudgery. [/italics] It has provided every county in the country with its concrete road and knitted the highways of the nation into a [italics] unified [/italics] traffic system. Thanks to Republican administration, farmer, dairyman and merchant can make deliveries in [italics] less [/italics] time and at [italics] less [/italics] expense, can borrow [italics] cheap [/italics] money to refund exorbitant mortgages, and stock their pastures, ranges and shelves. Democratic management [italics] impoverished [/italics] and [italics] demoralized [/italics] the [italics] railroads,[/italics] led packing plants and tire factories into [italics] receivership, [/italics] squandered billions on [italics] impractical [/italics] programs. Democratic maladministration issued [italics] further [/italics] billions of mere "scraps of paper," then encouraged foreign debtors to believe that their loans would never be called, and bequeathed to the Republican Party the job of [italics] mopping up the mess. [/italics] Republican administration has [italics] restored [/italics] to the railroads solvency, efficiency and par securities. It has brought rubber trades through panic and chaos, brought down the prices of crude rubber by smashing [italics] monopolistic rings,[/italics] put the tanner's books in the [italics] black [/italics] and secured from the European powers formal acknowledgment of their obligations. The Republican Party rests its case on a record of stewardship and performance. [full transcription at link]

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

2008 2012 2016 2020 2024 2028 Will Be The Year!

Some early polling has been released on how Jews plan to vote in 2024, and the big surprise is there's no surprise: Jews will, as in every other year, overwhelmingly support the Democratic candidate. In a Biden/Trump matchup, Jews favor Biden by a crushing 72/22 margin.

Other highlights:

Biden enjoys a healthy 63/33 approval rating. Trump is absolutely toxic at 19/80. But Ron DeSantis is barely better, clocking in at 21/76. Oh, and Netanyahu? Not such a hot commodity himself, at 28/62.

What's the biggest issue that concerns Jewish voters? "The future of democracy". 37% of Jewish voters placed that in their top two most important voting issues. Other issues which got flagged by at least 20% of respondents include inflation/the economy, abortion, climate change, and guns.

Israel, for what's worth, got top two billing by just 6% of respondents. But 72% of respondents still maintain an "emotional attachment" to Israel. This does not stop them from viewing the Netanyahu's judiciary proposals extremely negatively -- 61% say they will have a negative effect on Israel's democracy.

Abortion continues to be the 900 lbs monster of Jewish politics: 88% of Jews believe it should be legal in most or all cases. There's no other issue area that sees that level of agreement.

I also want to flag in particular the questions regarding "Who do you trust more to fight antisemitism?" Democrats hold a significant advantage over Republicans -- 57/22. And the gap has climbed considerably in the past year -- in April 22, that margin was 45/20. It appears that most of the gain has come from a ten point drop in the percentage of people who responded "trust neither party". This, to me, suggests that Biden's public and aggressive push to get out on front on antisemitism has paid dividends, "bringing home" more centrist-y Democrats who had been ambivalent or displeased about Democrats' commitment on the issue in years prior.

In any event, major condolences to the Republican Jewish Coalition on yet another imminent failure. But I have no doubt 2028 will be the year that Jews finally flock en masse to the GOP!

via The Debate Link https://ift.tt/wTDAPFI

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

My position on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, if anybody's wondering about it:

In the short term, Israel should stop bombing Gaza and allow more humanitarian relief in. In the longer term...

The "Israel is an apartheid state" talking point is basically correct: Israel's functional policy toward its Palestinian minority is to make them a subaltern class with less rights and make them live in shitty Bantustans; I consider that morally unacceptable. There's also no realistic morally acceptable way for Israel to get rid of the five million Palestinians who live in Gaza and the West Bank. The Israelis are stuck with the Palestinians and have a moral obligation to reach a mutually acceptable settlement with them that allows both nations to thrive.

By the same token, the Palestinians are stuck with the Israelis. Whatever your opinion on how this state of affairs came to be, the important fact is there are now millions of Israelis living in the territory of the state of Israel, there is no realistic and morally acceptable way to remove them from that territory, and it's quite reasonable for the Israelis to demand that any final settlement includes some kind of arrangement to protect them from the morally unacceptable means of removing them or from other retaliation.

The Israelis are the side with more power in this dynamic, therefore primary moral responsibility for improving the situation belongs to the Israelis. Have some Palestinians done bad things? Are some Palestinians violently antisemitic? Sure. Is Hamas bad? Probably, I guess. But if every Palestinian became a committed pacifist tomorrow, it's likely this would result in little or no change in their material conditions. The Israeli government by contrast could create enormous material changes in the situation tomorrow by making different choices. The Israelis have more freedom of action, and therefore more responsibility.

I've been talking about morality, but I'll also offer the points that:

1) The occupation inflicts great costs in blood, treasure, tears, sweat, and insecurity on both sides; it's really obviously hugely negative-sum and there's a big peace dividend (in far more than simply a financial sense) waiting for both sides if they can reach a mutually acceptable settlement and make it work.

2) A society where approximately half the population is a subaltern caste with less rights who are forced to live in shitty Bantustans is an inherently unstable arrangement.