#Bruce Jessen

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

To the “cruelty is the point” crowd, how long do we have to wait until we reach consciousness that cruelty is the profit margin?

James Mitchell and Bruce Jessen signed a $180mil contract with the CIA to devise the torture methods that formed part of the RDI programme. They received $81mil before the programme was terminated.

The dehumanization of all populations starts early. The “troubled teen” industrial complex that leads to reeducation fake schools and lethal wilderness camps are operated by global unregulated corporations, that receive up to $23bn in annual public funds.

Child protective services can be outsourced and a for-profit company named Maximus is operating vulnerable children as “income generators”, also squeezing cost at every corner and once being sued by its employees for failure to pay them. They received their first LA county contract on 1987 and by 1990 was already generating $19mil in revenue.

Arms manufacturers are also using Medicaid / Medicare and CPS contracts to generate revenue, namely Lockheed Martin and Northrop Gorman.

Prisons are used as cheap or slave labour. People deprived of their choices, their votes and their liberties are asked to work for private companies or for the state for a pittance, sometimes placing their own lives at risk. They produce on average $11bn in revenue each year.

The US is running on the commodification of human lives. Without cruelty, the US is losing a core part of what it is was literally founded on. Sit with that.

0 notes

Text

Parts Found in Sea

When I was a young teen, I was obsessed with the Toronto music scene, which is hilarious, because I was too young to get into any of the clubs where it was taking place, like the legendary Larry's Hideaway (believe me, I tried).

But I would obsessively note the names of the bands whose handbills were wheatpasted up and down Yonge Street and scour the bins at Sam the Record Man for their self-produced EPs and then play them over and over.

Some of those bands were...not good.

But I was absolutely obsessed with one band: Parts Found in Sea, whose name was taken from a newspaper headline about a plane crash (!). They were a damned hardworking act, playing - it seemed - every weekend at Larry's.

Since the Napster era, I have been periodically scouring the web for MP3s of the band, for sale, for free, whatever. I just wanted to hear them again.

Sometimes you revisit the music of your youth and realize that what made it good was that your own lack of sophistication - you didn't have the context to make the comparisons with other bands, didn't know that you were hearing a weak imitation of something amazing.

I feared that must be the case with PFIS: the fact that none of their music was available might mean that it just wasn't very good, and hadn't stood the test of time.

Then I discovered Stevy Zong's Youtube video of a live PFIS show at Larry's Hideaway and hearing that music again only renewed my ardor for the band. I also learned the name for their genre: "Darkwave."

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YNW89ZLKwSw

(It was also great to see them perform live, at last! The band was dissolved and Larry's was out of buiness by the time I was old enough to get into the club)

Inspired by that video, I bought a "Seat of the Writing Man," one of my favorite EPs by the band, on Ebay, and asked my friendly neighborhood archivist, Taylor Jessen, if he'd rip the vinyl for me, and he very kindly did, sending me the tracks last night.

And the band is every bit as good as I remember. I mean, just fucking great. Especially the Frank Lippai's bass-playing, which is just...wow. As far as I can tell, Lippai is living in London, Ont now, running something called "Artisans Almighty," but that's all I've got.

Frontman Steve Cowal graduated to a semi-famous Canadian band, Swamp Baby, and was featured in Bruce McDonald's "Hardcore Logo," but I can't find anything he's doing these days.

https://m.imdb.com/title/tt0116488/?ref_=m_nmfmd_msdp_1

The EP really showcases some spectacular talent, right down to the engineering by Ken Friesen, who is still working:

https://www.kenfriesen.com/

And while some of Cowal's lyrics are a little over-the-top emo, the songs are beautifully constructed, these long, jam-band-ish tracks that have two or three movements apiece, transitioning through different moods. They must have been amazing to dance to at a club.

I just couldn't keep this disc to myself. I've uploaded it for your listening pleasure, but only for 24 HOURS. Tomorrow morning (Pacific), I'll be deleting it. I figure that strikes a balance between celebration and misappropriation.

https://archive.org/details/pfi-s-sot-wm-lp-obverse

But if anyone out there is looking to reissue some wonderful audio unobtanium, they should track down the band and get these tracks into the stream of commerce.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Movie Review: The Report

Shortly after 9-11, the CIA and FBI implemented a program of torture for suspected terrorists. Years later, it was determined that these methods had not resulted in a single piece of actionable intelligence that the U.S. did not already possess. In the time between, dozens of people were subjected to such treatment as being doused naked in freezing water, kept awake for days, bound in contorted positions, and being sexually humiliated. Most knew nothing, and some were innocent of any crime. Those who were guilty offered nothing usable. These are facts, impervious to any political leanings. It is this attitude of dry, clinical truth, mixed with just the right amount of emotion from star Adam Driver, that makes The Report an engaging film.

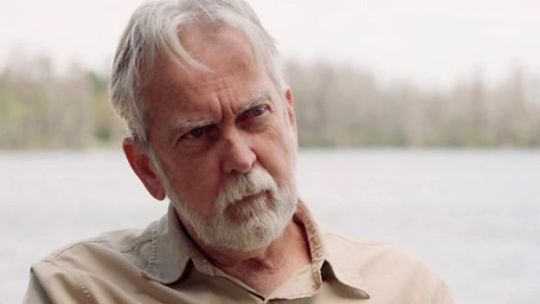

If your definition of “engaging” equates with “exciting”, you’ll want to scroll on by. Driver plays Daniel Jones, who, at the behest of Senator Dianne Feinstein (Annette Bening), led the investigation into the black sites where torture was performed after the CIA destroyed their tapes, which is not generally something people with nothing to hide do. He is a detail-oriented man: he reads through every page of every document available, insists on investigating even the smallest possible leads, and has a very difficult time giving up on a point when he knows he’s right. In other words, he’s exactly the kind of person you want if you’re going to go poking at an organization that is notorious for being secretive and defensive. He is not, as some will say, anti-American, having changed his classes to National Defense the day after the attacks. Driver’s removed style of acting, in which any display of emotion always comes as a surprise, fits the character well.

We know very little of his personal life, beyond the fact that he once had a relationship, which he no longer does due to spending his time at work. He’s eventually helped in his work by a disgusted and unwilling participant in the program (Tim Blake Nelson) and Ali Soufan (Fajer Al-Kaisi), a counter-terrorism expert whose years of experience and conviction that only relationship building yields good info are dismissed by the people calling the shots. Opposing him: a bevy of rotating CIA officials, all of whom seem aware of the flaws in the program but only care about protecting their tribe. These include a number of notable actors: Maura Tierney as a stand-in for Gina Haspel, Michael C. Hall, Jennifer Morrison, and Ted Levine. The latter, as real-life CIA director John Brennan, actively tries to smear Jones’ name in an effort to discredit his work, framing him for hacking into CIA servers.

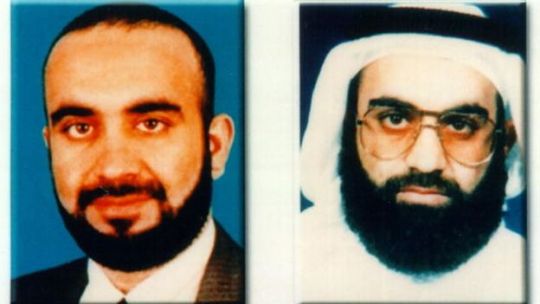

The things that took place at the black sites are shown in incredible detail, to the point where the squeamish may have a difficult struggle with the film. The “enhanced interrogation techniques”, the government’s euphemism for torture, do not consist of the stuff you see in movies---there are no beatings, no fingernails are ripped out. Prisoners such as Abu Zubaydah (Zoudi Boueri) are bound naked, placed in spaces too small for humans, screamed at constantly, kept awake with heavy metal music, drenched with freezing water. The two people behind most of the torture are psychologists who swear their methods work, even though none of their training is in interrogation. James Mitchell (Douglas Hodge) and Bruce Jessen (T. Ryder Smith) at first seem like they might really believe abuse works in getting information. This impression crumbles as the movie continues and they take evident pleasure in heaping pain on detainees, insisting the torture continue long after it has been proved useless. When confronted by investigators and asked point-blank why they are continuing if it hasn’t worked, Mitchell all but confesses it is more about revenge than effectiveness. Later, the two toast their success, and it is clear they aren’t talking about all the information they haven’t gotten. I find in digging into the true story that they made tens of millions of dollars as contractors doing this. Imagine having people like these for your psychologist.

Writer-director Scott Z. Burns and his team of producers, which include Steven Soderbergh, have gone to incredible lengths to accurately portray both the torture and the investigations. Some liberties have been taken---19 senate staffers have been reduced to Jones and a few composite characters, and of course some lines are there for dramatic effect---but digging into the real details shows a surprising level of accuracy. One gets the sense they are going against the cultural grain. The irony is they’ve made a movie accurately depicting the uselessness of torture, and it is usually movies and their dramatic exaggerations that make us think torture works. The movie flies in the face of a political ideology that equates violence with strength, and does so by sticking to the facts. Is it entertaining? It’s my job to answer that question. I would say it is effective. Those who need to see it probably won’t, and may not believe it if they do.

Verdict: Recommended

Note: I don’t use stars, but here are my possible verdicts.

Must-See

Highly Recommended

Recommended

Average

Not Recommended

Avoid like the Plague

You can follow Ryan's reviews on Facebook here:

https://www.facebook.com/ryanmeftmovies/

Or his tweets here:

https://twitter.com/RyanmEft

All images are property of the people what own the movie.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

“‘James Mitchell and Bruce Jessen conceived, designed and executed the first officially recognized torture program in U.S. history,’ Margulies said in an email. ‘It is one thing that they are utterly unapologetic; that is a commentary on them. But it is something else altogether that so much of the rest of the country is utterly indifferent; that is a commentary on us. A wrong that escapes public condemnation is no wrong at all. Worse, it invites not simply repetition, but expansion. Yesterday, we tortured men in cages because we thought they had done something wrong; today, we torture children at the border knowing they have done no wrong at all.’

He added: ‘Do not be seduced by linguistic lightfootedness and ask whether this really is torture. I refuse to play that game. Instead, I encourage people to ask themselves this: Would you recoil in horror if you saw the same things done to a dog? If you saw a dog strapped to a board and nearly drowned, again and again, would it make you cringe and wince? Would you turn away and demand that it stop? If so, then it is torture, and we should call it what it is.’”

From “Waterboarding of detainees was so gruesome that even CIA officials wept”, in the LA Times.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Los arquitectos de la tortura, la historia de los dos psicólogos que diseñaron los interrogatorios secretos de EE.UU.

Los arquitectos de la tortura, la historia de los dos psicólogos que diseñaron los interrogatorios secretos de EE.UU.

La teoría de la “indefensión aprendida” sostiene que se puede romper la voluntad de una persona sometiéndola a acontecimientos incontrolables y adversos. En esta teoría se basaron los psicólogos James E. Mitchell y John ‘Bruce’ Jessen para diseñar el programa de torturas de EEUU. La CIA los fichó por su experiencia en el ejército de EEUU entrenando a militares a soportar todo tipo de abusos en…

View On WordPress

1 note

·

View note

Text

U.S. Supreme Court questions claim of secrecy over post-9/11 torture

WASHINGTON

Supreme Court justices on Wednesday questioned the U.S. government's refusal to confirm the CIA tortured an alleged al-Qaida detainee in Poland, despite sweeping public information that made the government stance "farcical," as one justice called it.

They also questioned why the detainee, Saudi-born Palestinian Abu Zubaydah, remains held incommunicado in the U.S. military "War on Terror" prison in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, never having been charged after nearly two decades in U.S. custody.

In a case focused on "state secrets," Abu Zubaydah, 50, wants the U.S. high court to force two psychologists who ran the CIA's brutal interrogations of suspects after the September 11, 2001 attacks to testify in his case against Poland, where he was held in 2002-2003 as an alleged high-level al-Qaida official involved in the attacks.

A 2014 U.S. Senate report and statements by Polish officials have documented the torture and the location.

Abu Zubaydah's lawyer, David Klein, wants the two psychologists, both former contractors to the CIA, to confirm the details of his treatment, including the location.

But the CIA and the U.S. Justice Department argued that "state secrets privilege" allows them to block the testimony, to protect national security-related information including Poland's cooperation with the CIA.

U.S. intelligence partners will see the testimony by the two "as a serious breach of trust," making it harder to get more cooperation in the future, argued government attorney Brian Fletcher.

But justices asked what the harm was, since the information was already public and hardly a state secret, even if the CIA refuses to confirm it.

Moreover, the two psychologists, James Mitchell and Bruce Jessen, have already testified on aspects of the interrogation program in two other venues, including a Guantanamo case.

"At a certain point it becomes a little farcical," said Justice Elena Kagan of the claim of state secrets privilege.

"If everybody knows what this secret is, I guess we should rename it," she said.

At the same time, justices asked Klein why he needs the testimony if what happened is no longer secret.

"We're looking for eyewitness testimony... I want to shine a light inside it," he said of the torture program.

Abu Zubaydah, whose full name is Zayn Al-Abidin Muhammad Husayn, was the first of a number of detainees to be subjected to CIA "enhanced interrogation" in the wake of 9/11.

He was water-boarded 83 times, according to the Senate report, and suffered other physical abuse.

He was sent to Guantanamo in 2006 and never charged. The Senate report said the CIA conceded he was never a member of al-Qaida and not involved in planning the 9/11 attacks.

U.S. courts have rebuffed his habeas corpus petitions since then, and the U.S. military justice system has refused to release him, so in 2010 he sued in Poland to hold the government there responsible for his treatment.

Justice Neil Gorsuch questioned why Abu Zubaydah cannot testify himself to his treatment, which is blocked by Guantanamo regulations.

"What is the government's objection to the witness testifying on his own treatment, and not requiring any admission from the government of any kind?" Gorsuch said.

"I don't understand why he's still there after 14 years," added Justice Stephen Breyer.

Alka Pradhan, an attorney for another Guantanamo detainee, said that the psychologists' testimony is necessary.

The suggestion that Abu Zubaydah testify instead "shows a lack of understanding about torture effects," she wrote on Twitter.

"As the torture victim, AZ's memory cannot be relied upon in lieu of other testimony/accurate reports," she said.

0 notes

Link

One declassified cable, among scores obtained by the American Civil Liberties Union in a lawsuit against the architects of the “enhanced interrogation” techniques, says that chief of base and another senior counterterrorism official on scene had the sole authority power to halt the questioning. She never did so, records show, watching as Zubaydah vomited, passed out and urinated on himself while shackled. During one waterboarding session, Zubaydah lost consciousness and bubbles began gurgling from his mouth. Medical personnel on the scene had to revive him. Haspel allowed the most brutal interrogations by the CIA to continue for nearly three weeks even though, as the cables sent from Thailand to the agency’s headquarters repeatedly stated, “subject has not provided any new threat information or elaborated on any old threat information.” At one point, Haspel spoke directly with Zubaydah, accusing him of faking symptoms of physical distress and psychological breakdown. In a scene described in a book written by one of the interrogators, the chief of base came to his cell and “congratulated him on the fine quality of his acting.” According to the book, the chief of base, who was identified only by title, said: “Good job! I like the way you’re drooling; it adds realism. I’m almost buying it. You wouldn’t think a grown man would do that.” Haspel was sent by the chief of the CIA’s counterterrorism section, Jose Rodriquez, the “handpicked warden of the first secret prison the CIA created to handle al-Qaida detainees,” according to a little-noticed recent article in Reader Supported News by John Kiriakou, a former CIA counterterrorism officer. In his memoir, “Hard Measures,” Rodriquez refers to a “female chief of base” in Thailand but does not name her. Kirakou provided more details about her central role. “It was Haspel who oversaw the staff,” at the Thai prison, including James Mitchell and Bruce Jessen, the two psychologists who “designed the torture techniques and who actually carried out torture on the prisoners,” he wrote.

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Psicólogos que vendieron a la CIA técnicas de tortura

Cuando Jalid Sheij Mohammed, el pakistaní considerado autor intelectual de los ataques del 11-S, volvió a cruzar el martes los pasillos de la corte militar de Estados Unidos en la Base Naval de Guantánamo, se encontró por primera vez en muchos años con un viejo conocido. Allí estaba también el psicólogo estadunidense James E. Mitchell, quien junto a su colega Bruce Jessen fue el responsable de idear —y en muchos casos, probar, implementar y evaluar— las técnicas de tortura que utilizó la CIA en sus bases secretas contra los detenidos tras el ataque a las Torres Gemelas de Nueva York. Y quien, según admitió durante la audiencia, las supervisó y practicó a muchos de los detenidos, entre ellos el propio Mohammed. "Fue muy chocante que la gente que él mismo torturó estuviera en esa sala y que (Mitchell) dijera delante de ellos que los volvería a torturar de nuevo", cuenta Julia Hall, experta de Amnistía Internacional que asiste a las audiencias en Guantánamo. Hubo un cambio de roles: esta vez fueron los acusados los que escuchaban mientras el psicólogo respondía. Por primera vez desde que comenzaron las audiencias en Guantánamo en 2002 —y por dos semanas—, Mitchell y su colega Jessen son cuestionados por los abogados de los detenidos sobre las técnicas que idearon en los primeros años de la llamada "guerra contra el terror". "James Mitchell entró y fue claro: dijo que no se arrepentía del programa o de la forma en la que estuvo involucrado. No se disculpó, no mostró ninguna forma de arrepentimiento y reconoció en la corte que él mismo había practicado waterboarding (un método que hacen sentir a la persona que se ahoga) y otras técnicas de abusos", agrega. Algunas organizaciones de derechos humanos esperan que los testimonios traigan luz sobre la escala del programa de tortura, así como sobre la culpabilidad de altos funcionarios o el papel del FBI, uno de los grandes secretos de estos años. "Su testimonio puede revelar detalles adicionales sobre el programa de tortura de la CIA", comenta Wells Dixon, abogado del Center for Constitutional Rights, una organización de defensa legal en la que se dedica a desafiar lo que considera detenciones ilegales en Guantánamo. "En mi opinión, cada pequeño paso adelante para comprender lo que sucedió es importante y necesario si alguna vez queremos lograr algún tipo de responsabilidad", agrega.

James E. Mitchell, de 68 años, se unió a la Fuerza Aérea en 1974 y se especializó en desactivar bombas antes de doctorarse en psicología Pero los expertos también dudan de la legitimidad de estas audiencias o de sus posibles impactos, dado que se realizan en una corte militar que ha sido profundamente cuestionada en los últimos años. "El objetivo de las comisiones militares nunca ha sido lograr el progreso, y ciertamente tampoco la justicia o la responsabilidad por actos terroristas como el 11 de septiembre. Más bien, el propósito ha sido y sigue siendo preservar el status quo, evitar la liberación de los exdetenidos de la CIA y encubrir los detalles de su tortura y, en última instancia, que la CIA evite la responsabilidad por la tortura", indica Dixon. En criterio del experto, el testimonio de Mitchell ahora es simplemente un recordatorio de cuánto tiempo ha llevado llegar a este punto en el que una de las principales personas responsables de tortura sea llevada a testificar en el tribunal de Guantánamo. "También un recordatorio de cómo todavía no se ha tenido en cuenta lo que sucedió con las víctimas de tortura de la CIA. Todavía no ha habido ninguna responsabilidad significativa", afirma. "Indudablemente, esta es la razón por la cual Mitchell se ofreció a testificar, porque aparentemente no tiene nada que temer y es una oportunidad para defender sus acciones que son, seamos honestos, completamente indefendibles por cualquier estándar legal o moral", agrega.

La "guerra contra el terrorismo"

Los ataques de septiembre de 2001 llevaron a EE.UU. a la campaña más larga y costosa de su historia: la llamada "guerra contra el terrorismo". Las operaciones internacionales, apoyadas por países aliados y la OTAN, conllevaron no solo a abrir frentes de batalla en varias naciones de Medio Oriente, sino también a una cacería de los principales líderes y miembros de lo que EE.UU. consideraba "organizaciones terroristas". Desde inicios de la década del 2000, las cabezas de supuestos miembros de Al Qaeda, el Talibán y otros grupos extremistas comenzaron a figurar en la lista de los más buscados del mundo. Y en ella, los presuntos responsables detrás del 11-S ocuparon los primeros escaños. Desde enero de 2002, comenzaron a llegar a Guantánamo los primeros presos y poco a poco la cárcel improvisada en una base militar en el oriente de la isla de Cuba se llenó con algunos de los hombres más peligrosos del mundo.

Khalid Sheikh Mohammad fue capturado por primera vez en Pakistán en 2003. Pero no fue la única: Estados Unidos comenzó a crear centros de detención secretos en numerosos países del mundo, donde los prisioneros eran interrogados para obtener información sobre Al Qaeda y potenciales "ataques terroristas". "El informe de tortura del Senado muestra que la CIA estaba completamente mal equipada para detener e interrogar a los detenidos después del 11 de septiembre", recuerda Dixon. "La agencia estaba desesperada y agitada tras su fracaso para evitar los ataques (incluso por no alertar al FBI de que algunos de los secuestradores estaban en EE.UU. antes de los ataques) y, sospecho, la CIA querían venganza, por lo que recurrieron a Mitchell y Jessen, quienes ofrecieron soluciones rápidas y fáciles", agrega.

Psicología del terror

Según el abogado, fue entonces cuando los dos psicólogos que habían hecho carrera en las fuerzas armadas, comenzaron a colaborar con la Agencia Central de Inteligencia para diseñar "técnicas de interrogatorio severo". "Mitchell y su colega Jessen fueron psicólogos militares que la CIA contrató para interrogar a los detenidos después del 11 de septiembre, aparentemente para obtener información de inteligencia importante, que, como sabemos ahora, no pudieron obtener", indica. Ambos trabajaron como contratistas por meses para la agencia y crearon una compañía privada en 2005 ( Mitchell Jessen y Asociados, con oficinas en el estado de Washington y Virginia) para proveer a la agencia con los métodos y los mecanismos para sacar información a los presos de la "guerra contra el terror". El programa se llamó, eufemísticamente, "interrogatorio mejorado". "Ese programa buscaba que los interrogados proveyeran información que la CIA consideraba valiosa de los detenidos a través de severas técnicas de tortura y fueron justificados con una serie de memos que aseguraban que los efectos serían mínimos o a corto plazo", señala Hall.

La llamada "guerra contra el terrorismo" ha arrojado muchas sombras sobre los métodos utilizados por las autoridades para obtener confesiones. Entre otras técnicas, además del ahogamiento simulado, los reos eran encerrados en pequeñas cajas, sometidos a condiciones de aislamiento extremo, privación del sueño, manipulación de la dieta, desnudez forzada o abuso rectal. "Todas esas técnicas, desde un punto de vista legal, son consideradas sin lugar a duda formas tortura y el propio presidente Obama lo reconocería", afirma Hall. Según datos de una investigación del Senado, la CIA pagaba a Mitchell y Jessen US$1.800 por día y la compañía que crearon recibió US$80 millones por sus servicios hasta que se rescindió su contrato en 2009. Esto ocurrió después de que la CIA ya había aceptado pagar un contrato de indemnización de US$5 millones que cubría, entre otras cosas, procesamientos criminales. Según el contrato actual, la agencia está obligada a pagar gastos legales de la empresa hasta 2021.

Falta de capacidad

Según un informe del Senado, "ninguno de los dos psicólogos tenía experiencia dirigiendo interrogatorios, ni tampoco conocimiento específico sobre Al Qaeda, experiencia en la lucha contra el terrorismo o conocimientos culturales o lingüísticos relevantes". Aunque en un inicio sus nombres fueron mantenidos en secreto y aparecían en los informes con los pseudónimos de Dr. Grayson Swigert y Dr. Hammon Dunbar, desde que se conoció su identidad, muchas organizaciones han pedido que sean llamados a testificar sobre sus acciones. La Asociación Estadounidense de Psicología los expulsó de sus filas y rechazó públicamente sus métodos por "violar la ética de la profesión y dejar una mancha en la disciplina". "Eran charlatanes, que cometieron actos atroces de crueldad y barbarie al amparo de una pseudociencia por la que el gobierno de Estados Unidos pagó US$80 millones", indica Dixon.

Los grupos defensores de derechos humanos han realizado innumerables protestas solicitando infructuosamente el cierre de Guantánamo. Sin embargo, ambos psicólogos aseguran que actuaron por el bien de su país y que las técnicas que implementaron estaban diseñadas para reducir al máximo el sufrimiento de los reos, a la que vez que ayudarían a obtener información valiosa. Un informe posterior del Senado, no obstante, mostró que existían dudas de que las técnicas empleadas hubieran servido realmente para obtener alguna información decisiva que contribuyera a la seguridad nacional de Estados Unidos. "Una de las cosas que volvió a confirmar este caso es que la tortura no es solo inmoral e ilegal, sino también inefectiva", señala Hall.

Tras el juicio en Guantánamo

Según los expertos consultados, los testimonios de Mitchell y Jessen pueden ser vistos como una de las señales de que el juicio contra los acusados de los atentados del 11-S nunca se realizará. Las audiencias están programadas para enero del próximo año, pero muchos dudan que Guantánamo esté preparado para entonces a nivel de infraestructura para acoger un evento de ese tipo.

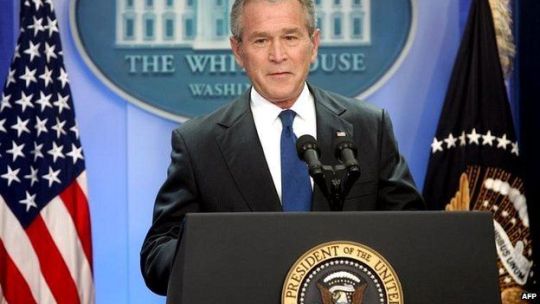

George W Bush era el presidente de EE.UU. cuando se aprobó el programa. Según Dixon, parece muy probable que el testimonio de Mitchell tenga poco efecto práctico, tanto en términos de avanzar el caso del 11 de septiembre como de obtener responsabilidad de la CIA por la tortura de la CIA. Sin embargo, cree que puede revelar detalles adicionales sobre el programa de tortura. "Tomó muchos años responsabilizar a torturadores como Pinochet y otros por sus crímenes durante la Guerras Sucias en América Latina y en otros lugares. Tenemos un largo camino por recorrer en términos del programa de tortura de la CIA, pero estoy seguro de que llegaremos allí", agrega.

Pese a las polémicas que la rodean, la prisión de Guantánamo sigue albergando prisioneros. Hall también duda que los testimonios de Mitchell y Jessen vayan a aportar algún elemento decisivo en Guantánamo, pero cree que el hecho de que hayan sido llamados a testificar puede servir para recordar lo que sucedió en las cárceles secretas de EE.UU. y el impacto que tuvo en el resto del mundo. "Lo que hicieron estos psicólogos significó una involución dramática en la lucha global contra la tortura, porque los métodos de interrogación que defendieron han tenido un efecto en todo el mundo", señala. "Y lo más chocante ha sido ver a Mitchell tan desafiante, diciendo que lo haría todo de nuevo". Read the full article

#Blog#Blogger#Emprendedores#Emprendimientos#Facebook#Google#Instagram#KharonteTechnologySolutions#Microsoft#Noticias#Outsourcing#social#Tecnología#Twitter

0 notes

Link

0 notes

Text

Los psicólogos que le enseñaron a la CIA técnicas para torturar - Más Regiones - Internacional

Los psicólogos que le enseñaron a la CIA técnicas para torturar – Más Regiones – Internacional

Cuando Jalid Sheij Mohammed, el pakistaní considerado autor intelectual de los ataques del 11-S, volvió a cruzar el martes los pasillos de la corte militar de Estados Unidos en la Base Naval de Guantánamo, se encontró por primera vez en muchos años con un viejo conocido.

Allí estaba también el psicólogo estadunidense James E. Mitchell, quien junto a su colega Bruce Jessen fue el responsable…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Note

whats the black site list?

The black site list is a list of locations where programming occurs. The sites are denied by the United states government. The Black Sites are where terrorists are taken and held with no legal protections.

The sites are also where TBMC continues to occur.

I’ll give a list below.

Oz

First quotes from documents confirming the existence of black sites.

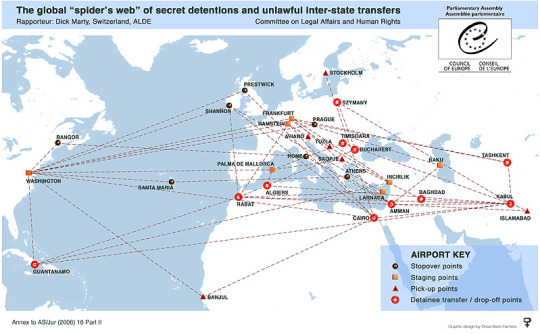

“Assurances have, in some circumstances, proved unreliable. With regard to the CIA’s extraordinary rendition of detainees from CIA-run ‘black sites’ in European States, it was submitted to the ECHR that by 2005”

“I am certain that the HVD programme has its general origins in the 17.09.2001 Finding, because our sources were unanimous on the question of the latitude this document afforded to the CIA. However we were also told separately of the existence of further classified documents (thought to have been signed in 2002) that actually use the term “black sites” in relation to specific facilities.”

“Indeed, even when the revelations of secret detentions in “several democracies in Eastern Europe” first emerged in November 2005,6 the publication responsible for breaking the story, The Washington Post, made a decision not to publish the names of the states which had hosted CIA “black sites”, although it was aware of this information.”

“There is nothing on the face of the intelligence reports that would alert the recipient agency to the fact that the detainee was subjected to torture to obtain the information contained in the report. Nor are there any indications in the reports that the CIA had engaged in extraordinary rendition, with these 39 detainees often moved around to several CIA black sites before appearing in detention at Guantanamo Bay”

“ECHR judgments describing the roles played by Lithuania and Romania in CIA black sites and rendition in their own countries “to avoid disturbing their relationship with the United States, a crucial partner and ally”. Abu Zubaydah v Lithuania”

The List of some black sites

“First we have received concurring confirmations that United States agencies have used the island territory of Diego Garcia, which is the international legal responsibility of the United Kingdom”

“Second we have been told that Thailand hosted the first CIA “black site,” and that Abu Zubaydah was held there after his capture in 2002.”

“One CIA source told us: “in Thailand, it was a case of ‘you stick with what you know’;” however, since the allegations pertaining to Thailand were not the direct focus of our inquiry, we did not elaborate further on these references in our discussions. The specific location of the “black site” in Thailand has been publicly alleged to be a facility in Udon Thani, near to the Udon Royal Thai Air Force Base in the north-east of the country.”

“The CIA brokered “operating agreements” with the Governments of Poland and Romania to hold its High-Value Detainees (HVDs) in secret detention facilities on their respective territories. Poland and Romania agreed to provide the premises in which these facilities were established, the highest degrees of physical security and secrecy, and steadfast guarantees of non-interference.”

As was already shown in my report of 12 June 2006 (PACE Doc 10957), these partners have included several Council of Europe member states. Only exceptionally have any of them acknowledged their responsibility – as in the case of Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Some European governments have obstructed the search for the truth and are continuing to do so by invoking the concept of “state secrets”. Secrecy is invoked so as not to provide explanations to parliamentary bodies or to prevent judicial authorities from establishing the facts and prosecuting those guilty of offences. This criticism applies to Germany and Italy, in particular. It is striking to note that state secrets are invoked on grounds almost identical to those advanced by the authorities in the Russian Federation in its crackdown on scientists, journalists and lawyers, many of whom have been prosecuted and sentenced for alleged acts of espionage. The same approach led the authorities of “the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia” to hide the truth and give an obviously false account of the actions of its own national agencies and the CIA in carrying out the secret detention and rendition of Khaled El-Masri. Detention sites:

BLACK - Romania

BLUE - "Quartz" - Stare Kiejkuty, Poland

BROWN - Afghanistan

COBALT - "Salt Pit" - Afghanistan

GRAY - Afghanistan

GREEN - Thailand

INDIGO - Guantanamo

MAROON - Guantanamo

ORANGE - Afghanistan

VIOLET - Lithuania

RED - This could be an additional site in one of the above countries, or someplace entirely different. It is mentioned only once in the report, on page 140 of 499, and the entry is almost entirely redacted.

Companies:

Company Y - Mitchell, Jessen & Associates, based in Spokane, Washington. The "Associates" are David Ayers, Randall Spivey, James Sporleder, Joseph Matarazzo, and Roger Aldrich.

It should be noted that there is no "Company X" in this report, I found this peculiar. It seems that there should be one, and as it happens there are several shady "Companies' known: "Premier Executive Transport Services" Incorporated in Dedham Massachusetts, is known to have been part of the CIA rendition program. The names of its officers include "Coleen Bornt," "Brian Dice" and "Tyler Edward Tate." These are fictitious people.

Other companies suspected of involvement in rendition include: "Stevens Express Leasing" "Richmor Aviation" "Rapid AirTrans" "Path Corporation"

Businesses:

Business Q - Associated with Zubair, associated with Hambali Torture Doctors:

"Grayson Swigert" - James Mitchell "Hammond Dunbar" - Bruce Jessen

CIA Officers:

CIA Officer 1 - COBALT Site manager - Matthew Zirbel. Zirbel's corrupt CIA boss (Convicted) Kyle Dusty Dustin Foggo overruled the 10 day suspension Zirbel received in the murder of Gul Rahman (innocent). CIA Officer 2 - Torturer at COBALT and BLUE - Albert El Gamil - retired from CIA in 2004.

Ron Czarnetsky, CIA Chief of Station on Warsaw, Poland from 2002 to 2005. This would make him responsible for site BLUE.

[no mention] Alfreda Frances Bikowsky - Made herself involved in Waterboarding in Poland (BLUE) in March of 2003. Took trip unassigned and on own dime. Was "scolded" and told it "wasn't supposed to be entertainment." Would have been there at the same time as Mitchell and Jessen.

Assets:

Asset X - Directly involved in the capture of KSM. Asset Y - Reports on Janat Gul

Persons:

Person 1 - al-Ghuraba group member, with an interest in airplanes and aviation. "intelligence indicates the interest was unrelated to terrorist activity." Detainees:

Detainee R - Held by foreign government, rendered to CIA custody Detainee S - Held by foreign government

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

I Was Tortured for Days Thanks to Bruce Jessen and James Mitchell

https://www.newsweek.com/tortured-jessen-mitchell-rabbani-sorry-guantanamo-1483100 Comments

0 notes

Text

"Volvería a hacerlo": un 'arquitecto de torturas' de la CIA defiende sus prácticas

El psicólogo James E. Mitchell creó e implementó, junto con John 'Bruce' Jessen, las llamadas "técnicas avanzadas de interrogatorio" puestas en práctica tras los atentados del 11-S.

0 notes

Text

Los arquitectos de la tortura: la historia de los dos psicólogos que diseñaron los interrogatorios secretos de EEUU

La teoría de la "impotencia aprendida" sostiene que se puede romper la voluntad de una persona sometiéndola a acontecimientos incontrolables y adversos. En esta teoría se basaron los psicólogos James E. Mitchell y John ‘Bruce’ Jessen para diseñar el programa de torturas de EEUU. Recibían hasta 1.800 dólares al día por aplicar su programa de torturas y después formaron una empresa que recibió 81 millones de dólares de la CIA. Relacionada: www.meneame.net/story/ai-asistira-audiencia-previa-psicologos-responsa

etiquetas: tortura, estados unidos, psicólogos

» noticia original (www.eldiario.es)

0 notes

Photo

Guantanamo Bay Torture Psychologists Set for First Public Testimony on ‘Perverse’ CIA Work James Mitchell and Bruce Jessen designed the "enhanced interrogration" program used against detainees during the initial stages of the War on Terror. Source: Guantanamo Bay Torture Psychologists Set for First Public Testimony on 'Perverse' CIA Work

0 notes

Text

I Was Tortured For Days Thanks To Bruce Jessen And James Mitchell. A "Sorry" Would Be Nice | Opinion

I am a nobody: an innocent taxi driver from Karachi, Pakistan, held without charges in Guantanamo Bay, tortured, forever separated from my son. But I hope the two psychologists responsible for what was inflicted on me will stop by my cell. I'll be waiting.

I understand that Bruce Jessen and James Mitchell will be testifying this week at the Guantánamo military commissions about their torture project. Of course they don't call it that—the methods devised by these mercenary psychologists are, we are told, only "enhanced interrogation techniques"—but I have been on the receiving end, and I prefer to be honest.

Even though I am a nobody, a taxi driver from Karachi, I am a "forever prisoner" down here in this awful Cuban prison, 17 years into my detention without trial. If they appear in person, I hope they will stop by my cell in Camp Six. I am still waiting for an apology.

Jessen and Mitchell helped to bring torture into the Twenty-First Century. They formed a company that was paid $81 million to operate the interrogation program that was used on me and others. They have been unapologetic about this—defiant, even. Their lawyer, James T. Smith, says his clients were "public servants whose actions ... were authorized by the U.S. government, legal and done in an effort to protect innocent lives."

I doubt many innocent people were saved by torturing me. I was minding my own business in Karachi when I was kidnapped and sold to the U.S. for a bounty by Pakistani authorities, with the assurance that I was a terrorist called Hassan Ghul. The U.S. later captured the real Ghul, but rather than admit their mistake, they took me to the "Dark Prison" in Kabul and applied some of the methods promoted by Jessen and Mitchell.

The two "doctors" assured the military men who hired them and the lawyers and politicians who signed it off that their techniques were entirely "painless". Let me take you through the one described as "a technique in which the detainees' wrists were tied together above their heads and they were unable to lean against a wall or lie down." I was put down a hole, suspended by my wrists from two chains that were locked to a horizontal metal bar at a height where my feet could barely touch the ground. I was left in total darkness for days—perhaps a week. Without food. Standing on tiptoe in my own excrement.

Later I learned that this was something Jessen and Mitchell picked up from the Spanish Inquisition, who called it strappado. The Inquisition did this to make people suffer (normally fellow Christians who were deemed heretics and tortured into admitting it) and were at least more honest than Jessen and Mitchell (whose technique was practiced entirely on Muslims). I felt my shoulders gradually dislocating. The pain was excruciating.

Jessen and Mitchell also advocated the use of waterboarding. I have heard that some years back, Dr. Mitchell said most people would prefer to have their legs broken than to be waterboarded, but he appears to have changed his mind when he got his $81 million contract. "I don't know that it's painful," he said more recently. "I'm using the word distressing." The right word is torture.

They encouraged the CIA to destroy video footage that was made of the interrogations because it was too graphic: "I thought they were ugly and they would, you know, potentially endanger our lives by putting our pictures out so that the bad guys could see us," Mitchell explained.

I am told Jessen and Mitchell have been "indemnified"—perhaps by as much as $5 million—for the nuissance of being sued for torturing people. They apparently got to keep all their $81 million. And for what? For permanently damaging the reputation of the United States as a country built on laws and sworn to defend freedom. For inflicting hideous physical and psychological pain on scores of innocent men like me. For making it almost impossible to bring the alleged masterminds of 9/11 to justice—19 years later, the lawyers are still arguing whether their treatment has been so uncivilized that the whole case should be dismissed.

In common with their handlers at the CIA and the politicians in charge, Jessen and Mitchell have suffered no consequences. Meanwhile, simply for being in the wrong place and the wrong time, a victim of mistaken identity, I have suffered not only physical torture but the deep and lasting pain of being separated from my son. Jawad is 17 years old now, and I have never met him, let alone touched him.

The past cannot be undone but we can try to build a better future. As a start, I would like the two men to stop by my cell this week and say that simple word "sorry". I am not allowed to go anywhere. I will be waiting.

Ahmed Rabbani is a taxi driver from Karachi, sold to US forces for a bounty and held as prisoner without charge for 17 years (and counting.)

— By Ahmed Rabbani. The views expressed in this article are the author's own.

— Newsweek | January 20, 2020

0 notes