#Big Squaw Mountain

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

BlockONE: Convenient Living Close to Campus

Living near your school makes everything easier, and BlockONE puts ISU students right where they need to be. With studio through 4-bedroom floorplans, you’ll find the perfect setup for your lifestyle. These off-campus housing near Iowa State University options keep you close to class while giving you the freedom of apartment living. You can walk to campus in minutes, skip the hassle of a long commute, and enjoy on-site parking and bike storage for extra convenience. Need a quick bite or some essentials? The street-level retail makes errands simple. Whether you prefer biking, walking, or driving, getting around is stress-free. BlockONE gives you the best of both worlds—independence and easy access to everything you need.

Move-In Ready Living

Renting a fully furnished apartment saves you time, money, and hassle. At BlockONE, you get more than just a place to live—you get a space that’s set up for comfort from day one. These furnished apartments near Iowa State University come with everything you need, so you can skip the furniture shopping and heavy lifting. Each apartment includes a full-size bed, desk, chair, and dresser drawers in every bedroom. The living room is ready for movie nights with a sofa, chair, coffee table, end table, entertainment stand, and an HDTV. Whether you’re studying or relaxing, your space is designed to fit your lifestyle. With floorplans ranging from studios to four bedrooms, you’ll find the perfect setup for your needs. Just bring your essentials and make it home.

The Geography of Ames, Iowa

Ames sits right in the middle of Iowa, surrounded by open farmland and rolling fields. The landscape is pretty flat, but you’ll find some gentle hills here and there. The Squaw Creek runs through town, adding a bit of natural beauty and the occasional flood risk after heavy rains. Parks and green spaces are scattered throughout, giving you places to walk, bike, or just enjoy the outdoors. Weather-wise, you get all four seasons—hot summers, cold winters, and everything in between. The city itself is fairly compact, making it easy to get around, whether by car, bike, or bus. While it might not have mountains or oceans, Ames has a charm of its own with its mix of small-town feel and university life, all set against the classic Iowa countryside.

Hilton Coliseum in Ames, IA

If you’re into sports or live events, Hilton Coliseum is the place to be. It’s home to Iowa State basketball, wrestling, and volleyball, and the energy inside is something you have to experience. Fans are loud, especially during big games, and the atmosphere can be electric. Even if you’re not a die-hard sports fan, the coliseum also hosts concerts, speakers, and other events throughout the year. The seating is good from almost anywhere, and parking is usually manageable if you arrive early. Grabbing some snacks or merch before the game just adds to the fun. Whether you’re cheering for the Cyclones or just enjoying a live event, Hilton Coliseum gives you a real taste of Ames’ excitement and community spirit.

Independent News Website Launching Soon In Ames

This could be a game-changer for local news in Ames. With The Ames Tribune cutting back on original reporting, the launch of the Ames Voice feels like a much-needed response. People want reliable, in-depth coverage about their own communities, not just content pulled from a bigger paper in another city. The focus on local agriculture, small businesses, and Iowa State makes sense—those are the topics that actually impact daily life here. Plus, the transparency around funding is a good sign. Trust in media isn’t exactly at an all-time high, so being upfront about who’s supporting the newsroom helps. It’ll be interesting to see how well they balance nonprofit sustainability with truly independent journalism, but if they stick to their mission, this could be a huge win for Story County.

Link to map

Hilton Coliseum 1705 Center Dr, Ames, IA 50011, United States Head west toward Center Dr 276 ft Turn left 0.1 mi Turn right onto Center Dr 0.2 mi Turn right onto Beach Ave 0.2 mi Turn left onto Lincoln Way 0.5 mi Make a U-turn at Stanton Ave Destination will be on the right 384 ft BlockONE 2320 Lincoln Way, Ames, IA 50014, United States

0 notes

Text

California Cabin Rentals for a Winter Wonderland Escape

Experience the magic of winter with California cabin rentals for the ultimate wonderland escape. Nestled in picturesque settings like Lake Tahoe, Big Bear, and Yosemite, these cozy retreats offer breathtaking views, snow-covered landscapes, and endless outdoor adventures. From rustic log cabins to luxurious modern lodges, you’ll find the perfect spot to relax and unwind. Enjoy skiing, snowboarding, and snowshoeing during the day, then return to a warm fire and serene surroundings in the evening. Many cabins feature hot tubs, fireplaces, and fully-equipped kitchens to make your stay even more memorable. Whether planning a romantic getaway or a family retreat, California’s winter cabin rentals promise an unforgettable experience. Book your escape today and embrace the beauty of the season.

Lake Tahoe: A Snowy Paradise

Lake Tahoe is a quintessential winter destination in california cabin rentals. Renowned for its crystal-clear waters and surrounding snowy peaks, the region offers a variety of cabin rentals. Choose from luxurious lakefront properties or rustic woodland retreats. Enjoy skiing, snowboarding, or snowshoeing at world-class resorts like Heavenly and Squaw Valley. After a day on the slopes, unwind by the fire with a view of the pristine lake.

Big Bear Lake: A Cozy Mountain Retreat

Nestled in the San Bernardino Mountains, Big Bear Lake is a haven for winter enthusiasts. Its charming cabins come equipped with modern amenities, hot tubs, and stunning mountain views. Big Bear Mountain Resort is a hotspot for skiing and snowboarding, while the surrounding trails are perfect for hiking and sledding. For a more laid-back experience, enjoy the quaint shops and restaurants in Big Bear Village.

Yosemite National Park: Winter’s Tranquil Beauty

Winter in Yosemite transforms the park into a serene wonderland. california cabin rentals near the park’s entrance offer a perfect base for exploring iconic landmarks like El Capitan and Bridalveil Fall, draped in snow. Experience activities like ice skating at Curry Village or cross-country skiing in the peaceful meadows. These cozy cabins allow you to disconnect and immerse yourself in nature’s beauty.

Mammoth Lakes: Adventure and Luxury Combined

Mammoth Lakes is a premier winter destination for adventure seekers. The area boasts upscale cabins and chalets that cater to families and groups. Skiers and snowboarders flock to Mammoth Mountain, one of the largest ski areas in California. Off the slopes, enjoy snowmobiling, ice climbing, or relaxing in natural hot springs. With luxurious cabin accommodations, your winter escape here promises to be unforgettable.

Shasta Cascade Region: Hidden Gems of the North

The Shasta Cascade region is a less-traveled winter destination with breathtaking landscapes and cozy cabins. Explore Mount Shasta, known for its excellent skiing and snowboarding. For a quieter retreat, the area’s secluded cabins offer stunning views of snow-covered forests and mountains. Nearby attractions include Lassen Volcanic National Park and scenic snowshoe trails, making this region ideal for nature lovers.

Julian: A Rustic Winter Experience

Julian, a historic gold mining town in Southern california cabin rentals, offers a unique winter getaway. Stay in charming cabins surrounded by apple orchards and rolling hills. The town’s mild snowfall adds a festive touch, perfect for a cozy retreat. Enjoy homemade apple pie, explore antique shops, or visit nearby Lake Cuyamaca for fishing and hiking. Julian’s tranquil atmosphere provides a rustic and romantic winter escape.

Mt Baldy: An Alpine Escape Close to Los Angeles

For those seeking a quick winter getaway from the city, Mt. Baldy offers an alpine experience just an hour from Los Angeles. Rent a cabin nestled in the San Gabriel Mountains and enjoy skiing, snowboarding, or snow tubing at Mt. Baldy Resort. The cozy cabins, coupled with the mountain’s serene environment, make it an ideal spot for a weekend retreat. Don’t miss the breathtaking sunset views over the valley below.

Conclusion

California’s diverse landscapes make it a premier destination for winter california cabin rentals escapes. From the iconic beauty of Lake Tahoe and Yosemite to the hidden gems of the Shasta Cascade and Julian, there’s a cabin rental to suit every preference. Whether you’re an adventure seeker or someone looking to relax by a roaring fire, these destinations offer something special for everyone. Embrace the season and create lasting memories in California’s winter wonderland.

0 notes

Photo

The Palisades Tahoe ski resort has a lot going for it: an idyllic location seven miles from Lake Tahoe’s western shore, a peak elevation of 9,050 feet with 2,850 feet of vertical, and 6,000 skiable acres spread over two bases and served by 43 lifts.The famed California destination, which is celebrating its 75th anniversary, has cool, swagger and a wealth of demanding terrain. The resort hosted the 1960 Winter Olympics when it was still called Squaw Valley, and is among the Alpine Ski World Cup’s few regular stops in the United States.Yet at times, it feels as if all people talk about is the weather.Take my first visit to the resort, this past February, which took place in a windy whiteout.On the first day, I rode up the tram from the Palisades base area, then felt my way down the blue runs off the Siberia Express and Gold Coast Express lifts in a sea of white on white. Palisades Tahoe is known for its bowls, chutes and gullies, especially off the KT-22 chair, but I was not ready to venture there essentially blindfolded.While I was trying to find my bearings on Emigrant Face — a bowl-like blue area off one of the highest lifts — a snowboarder zoomed by so fast that he didn’t see a ridge in the fog and took off like an eagle. An eagle that couldn’t fly, because he crashed.Still, against all odds, I was having fun.And so was Joan Collins, 60, from Madison, Wis., whom I met during lunch at the Alpine base area the next day, when it was marginally less foggy but snowing hard. “For me the hardest part was not seeing the horizon, snow blowing in your face so you can’t really see where you’re going,” said Ms. Collins. “But we’ve been hollering all the way down on some of those runs — it’s like a big, powdery playground.”As snow fell relentlessly, parts of the mountain were closed for avalanche mitigation. Several lifts were on hold because of winds that, I later learned, could reach 100 miles per hour on the ridge tops. By noon it was obvious I really should have refreshed my jacket’s waterproofing.My visit coincided with a big dump of snow after an alarmingly dry December and an average January. Not long after, in early March, a major storm dropped eight feet of snow on the resort. Which might sound amazing to powder hounds, except that the roads and lifts were closed.This year, true to form, good conditions allowed the resort to kick off its season five days early in November.First in line for stormsThis yo-yo pattern comes from the resort’s location, 200 miles east of San Francisco. The local mountains, part of the Sierra Nevada range, are first in line when moisture-laden storms travel eastward from the Pacific. And with nothing to slow it down, the unimpeded jet stream can hit Palisades Tahoe with hurricane force. The resort’s relatively low altitude, with a main base at 6,200 feet, helps create conditions that can vary drastically within a single day as well as between the upper and the lower mountains. At least the Palisades base has great easygoing terrain at the top, so beginners and intermediates can enjoy good snow quality instead of being stuck on scraped-out or wet runs at lower elevations.There are other big upsides. When it’s not snowing, “we have really nice weather for a Western ski destination,” said Bryan Allegretto, the Northern Sierra specialist at the forecasting and conditions site OpenSnow. “When the sun’s out, it’s warm relative to a lot of mountain areas, so you get this beautiful, amazing weather for skiing that isn’t super cold.” (The average daytime high in January is 36 degrees.)And in a good year, the season can extend well into the spring. “I ski as long as the resort is open — there’s been several years when I skied on July 4,” Stephanie Yu, 49, who lives in Sacramento, said in a phone interview after my trip.A long history and a new nameNo wonder Palisades Tahoe is among the most popular winter destinations in America, even if, technically speaking, it was born only three years ago.The mountain opened in 1949 as Squaw Valley and acquired its neighbor, Alpine Meadows, seven miles away, in 2011. The new entity went by the cumbersome umbrella Squaw Valley Alpine Meadows until it was rebranded as Palisades Tahoe in 2021, to avoid a term that is offensive to many Native Americans.The next year a gondola connecting the base areas at the two mountains was installed; there is also a free on-demand shuttle between the two.Yet part of the Palisades Tahoe draw is how distinct its two components have remained. Palisades is bigger and sleeker, with more and better dining options, an active après scene, activities like disco tubing (which adds party lights and pumping music to regular tubing), and big-time concerts — this year, Diplo was among the performers.The plentiful lifts include a tram and a hybrid known as the Funitel (a mash-up of the French words “funiculaire” and “téléphérique”), and there is an abundance of signature terrain, which, in addition to the KT-22-served runs, includes open steeps off the Headwall and Siberia lifts (unfortunately, among the first to close because of wind) and a bumps minefield named after the local Olympic freestyle skier Jonny Moseley.The Palisades side is so spread out that you can easily move on to another section of the mountain if one gets closed off or too crowded. After struggling with low visibility on my first day, I eventually found better conditions in the Shirley bowl on the back side. Then, to flee both the crowds and the increasingly strong wind, I headed to the Snow King area, tucked away to the far left of the mountain, as you look uphill. From the Red Dog and Far East Express lifts, I made laps on runs that meandered through trees.More complicated was securing a parking spot for my rental car. Palisades Tahoe is part of the Ikon multiresort pass and in recent years has experienced an increase in crowds and traffic. Palisades visitors who don’t stay on-mountain tend to favor Truckee, a town 11 miles away, but Route 89 from there to Palisades can easily turn into a long ribbon of vehicles. (I stayed seven miles from the resort in the other direction, in tiny Tahoe City, which offers an easier commute.)To deal with the crunch, Palisades Tahoe has started requiring parking reservations on Saturdays, Sundays and select holidays. You can book a spot for $30 or try your luck when free reservations open on the Tuesday before the weekend, with sign-up windows at 12 p.m. and 7 p.m. On my first attempt, I hadn’t even completed setting up my account before all the spaces were gone in 12 minutes. A few hours later, it took only six minutes for them to fill up, but I was ready and got a free spotUnassuming AlpineCompared with the Palisades side’s extroverted, big personality, Alpine still feels like an unassuming locals’ hill, with a trail map that looks underfed. Don’t underestimate it: “A lot of the best terrain is hike-to only, well hidden to where your average user won’t find it,” said Mark Fisher, who, with another local, runs a site called Unofficial Alpine that reports on the mountain.For a newcomer, though, the layout felt instinctive and easy, and I was able to have fun with the handful of lifts open on my visit, like the punishingly slow two-seater Yellow Chair — where a wild gust made me slide backward when I disembarked.I also got schooled on an innocent-looking blue run off Roundhouse Express, when my skis hopelessly sank into what looked like mounds of fluffy powder but felt like quicksand. Welcome to the notorious heavy snow known as Sierra cement.Yet something was happening. Trees offered shelter when I needed it, the runs were half empty, there were no lines anywhere, and the snow kept falling. I wasn’t even cold.Fine, count me in: There is something to be said about California skiing.Follow New York Times Travel on Instagram and sign up for our weekly Travel Dispatch newsletter to get expert tips on traveling smarter and inspiration for your next vacation. Dreaming up a future getaway or just armchair traveling? Check out our 52 Places to Go in 2024. Source link

0 notes

Photo

The Palisades Tahoe ski resort has a lot going for it: an idyllic location seven miles from Lake Tahoe’s western shore, a peak elevation of 9,050 feet with 2,850 feet of vertical, and 6,000 skiable acres spread over two bases and served by 43 lifts.The famed California destination, which is celebrating its 75th anniversary, has cool, swagger and a wealth of demanding terrain. The resort hosted the 1960 Winter Olympics when it was still called Squaw Valley, and is among the Alpine Ski World Cup’s few regular stops in the United States.Yet at times, it feels as if all people talk about is the weather.Take my first visit to the resort, this past February, which took place in a windy whiteout.On the first day, I rode up the tram from the Palisades base area, then felt my way down the blue runs off the Siberia Express and Gold Coast Express lifts in a sea of white on white. Palisades Tahoe is known for its bowls, chutes and gullies, especially off the KT-22 chair, but I was not ready to venture there essentially blindfolded.While I was trying to find my bearings on Emigrant Face — a bowl-like blue area off one of the highest lifts — a snowboarder zoomed by so fast that he didn’t see a ridge in the fog and took off like an eagle. An eagle that couldn’t fly, because he crashed.Still, against all odds, I was having fun.And so was Joan Collins, 60, from Madison, Wis., whom I met during lunch at the Alpine base area the next day, when it was marginally less foggy but snowing hard. “For me the hardest part was not seeing the horizon, snow blowing in your face so you can’t really see where you’re going,” said Ms. Collins. “But we’ve been hollering all the way down on some of those runs — it’s like a big, powdery playground.”As snow fell relentlessly, parts of the mountain were closed for avalanche mitigation. Several lifts were on hold because of winds that, I later learned, could reach 100 miles per hour on the ridge tops. By noon it was obvious I really should have refreshed my jacket’s waterproofing.My visit coincided with a big dump of snow after an alarmingly dry December and an average January. Not long after, in early March, a major storm dropped eight feet of snow on the resort. Which might sound amazing to powder hounds, except that the roads and lifts were closed.This year, true to form, good conditions allowed the resort to kick off its season five days early in November.First in line for stormsThis yo-yo pattern comes from the resort’s location, 200 miles east of San Francisco. The local mountains, part of the Sierra Nevada range, are first in line when moisture-laden storms travel eastward from the Pacific. And with nothing to slow it down, the unimpeded jet stream can hit Palisades Tahoe with hurricane force. The resort’s relatively low altitude, with a main base at 6,200 feet, helps create conditions that can vary drastically within a single day as well as between the upper and the lower mountains. At least the Palisades base has great easygoing terrain at the top, so beginners and intermediates can enjoy good snow quality instead of being stuck on scraped-out or wet runs at lower elevations.There are other big upsides. When it’s not snowing, “we have really nice weather for a Western ski destination,” said Bryan Allegretto, the Northern Sierra specialist at the forecasting and conditions site OpenSnow. “When the sun’s out, it’s warm relative to a lot of mountain areas, so you get this beautiful, amazing weather for skiing that isn’t super cold.” (The average daytime high in January is 36 degrees.)And in a good year, the season can extend well into the spring. “I ski as long as the resort is open — there’s been several years when I skied on July 4,” Stephanie Yu, 49, who lives in Sacramento, said in a phone interview after my trip.A long history and a new nameNo wonder Palisades Tahoe is among the most popular winter destinations in America, even if, technically speaking, it was born only three years ago.The mountain opened in 1949 as Squaw Valley and acquired its neighbor, Alpine Meadows, seven miles away, in 2011. The new entity went by the cumbersome umbrella Squaw Valley Alpine Meadows until it was rebranded as Palisades Tahoe in 2021, to avoid a term that is offensive to many Native Americans.The next year a gondola connecting the base areas at the two mountains was installed; there is also a free on-demand shuttle between the two.Yet part of the Palisades Tahoe draw is how distinct its two components have remained. Palisades is bigger and sleeker, with more and better dining options, an active après scene, activities like disco tubing (which adds party lights and pumping music to regular tubing), and big-time concerts — this year, Diplo was among the performers.The plentiful lifts include a tram and a hybrid known as the Funitel (a mash-up of the French words “funiculaire” and “téléphérique”), and there is an abundance of signature terrain, which, in addition to the KT-22-served runs, includes open steeps off the Headwall and Siberia lifts (unfortunately, among the first to close because of wind) and a bumps minefield named after the local Olympic freestyle skier Jonny Moseley.The Palisades side is so spread out that you can easily move on to another section of the mountain if one gets closed off or too crowded. After struggling with low visibility on my first day, I eventually found better conditions in the Shirley bowl on the back side. Then, to flee both the crowds and the increasingly strong wind, I headed to the Snow King area, tucked away to the far left of the mountain, as you look uphill. From the Red Dog and Far East Express lifts, I made laps on runs that meandered through trees.More complicated was securing a parking spot for my rental car. Palisades Tahoe is part of the Ikon multiresort pass and in recent years has experienced an increase in crowds and traffic. Palisades visitors who don’t stay on-mountain tend to favor Truckee, a town 11 miles away, but Route 89 from there to Palisades can easily turn into a long ribbon of vehicles. (I stayed seven miles from the resort in the other direction, in tiny Tahoe City, which offers an easier commute.)To deal with the crunch, Palisades Tahoe has started requiring parking reservations on Saturdays, Sundays and select holidays. You can book a spot for $30 or try your luck when free reservations open on the Tuesday before the weekend, with sign-up windows at 12 p.m. and 7 p.m. On my first attempt, I hadn’t even completed setting up my account before all the spaces were gone in 12 minutes. A few hours later, it took only six minutes for them to fill up, but I was ready and got a free spotUnassuming AlpineCompared with the Palisades side’s extroverted, big personality, Alpine still feels like an unassuming locals’ hill, with a trail map that looks underfed. Don’t underestimate it: “A lot of the best terrain is hike-to only, well hidden to where your average user won’t find it,” said Mark Fisher, who, with another local, runs a site called Unofficial Alpine that reports on the mountain.For a newcomer, though, the layout felt instinctive and easy, and I was able to have fun with the handful of lifts open on my visit, like the punishingly slow two-seater Yellow Chair — where a wild gust made me slide backward when I disembarked.I also got schooled on an innocent-looking blue run off Roundhouse Express, when my skis hopelessly sank into what looked like mounds of fluffy powder but felt like quicksand. Welcome to the notorious heavy snow known as Sierra cement.Yet something was happening. Trees offered shelter when I needed it, the runs were half empty, there were no lines anywhere, and the snow kept falling. I wasn’t even cold.Fine, count me in: There is something to be said about California skiing.Follow New York Times Travel on Instagram and sign up for our weekly Travel Dispatch newsletter to get expert tips on traveling smarter and inspiration for your next vacation. Dreaming up a future getaway or just armchair traveling? Check out our 52 Places to Go in 2024. Source link

0 notes

Photo

The Palisades Tahoe ski resort has a lot going for it: an idyllic location seven miles from Lake Tahoe’s western shore, a peak elevation of 9,050 feet with 2,850 feet of vertical, and 6,000 skiable acres spread over two bases and served by 43 lifts.The famed California destination, which is celebrating its 75th anniversary, has cool, swagger and a wealth of demanding terrain. The resort hosted the 1960 Winter Olympics when it was still called Squaw Valley, and is among the Alpine Ski World Cup’s few regular stops in the United States.Yet at times, it feels as if all people talk about is the weather.Take my first visit to the resort, this past February, which took place in a windy whiteout.On the first day, I rode up the tram from the Palisades base area, then felt my way down the blue runs off the Siberia Express and Gold Coast Express lifts in a sea of white on white. Palisades Tahoe is known for its bowls, chutes and gullies, especially off the KT-22 chair, but I was not ready to venture there essentially blindfolded.While I was trying to find my bearings on Emigrant Face — a bowl-like blue area off one of the highest lifts — a snowboarder zoomed by so fast that he didn’t see a ridge in the fog and took off like an eagle. An eagle that couldn’t fly, because he crashed.Still, against all odds, I was having fun.And so was Joan Collins, 60, from Madison, Wis., whom I met during lunch at the Alpine base area the next day, when it was marginally less foggy but snowing hard. “For me the hardest part was not seeing the horizon, snow blowing in your face so you can’t really see where you’re going,” said Ms. Collins. “But we’ve been hollering all the way down on some of those runs — it’s like a big, powdery playground.”As snow fell relentlessly, parts of the mountain were closed for avalanche mitigation. Several lifts were on hold because of winds that, I later learned, could reach 100 miles per hour on the ridge tops. By noon it was obvious I really should have refreshed my jacket’s waterproofing.My visit coincided with a big dump of snow after an alarmingly dry December and an average January. Not long after, in early March, a major storm dropped eight feet of snow on the resort. Which might sound amazing to powder hounds, except that the roads and lifts were closed.This year, true to form, good conditions allowed the resort to kick off its season five days early in November.First in line for stormsThis yo-yo pattern comes from the resort’s location, 200 miles east of San Francisco. The local mountains, part of the Sierra Nevada range, are first in line when moisture-laden storms travel eastward from the Pacific. And with nothing to slow it down, the unimpeded jet stream can hit Palisades Tahoe with hurricane force. The resort’s relatively low altitude, with a main base at 6,200 feet, helps create conditions that can vary drastically within a single day as well as between the upper and the lower mountains. At least the Palisades base has great easygoing terrain at the top, so beginners and intermediates can enjoy good snow quality instead of being stuck on scraped-out or wet runs at lower elevations.There are other big upsides. When it’s not snowing, “we have really nice weather for a Western ski destination,” said Bryan Allegretto, the Northern Sierra specialist at the forecasting and conditions site OpenSnow. “When the sun’s out, it’s warm relative to a lot of mountain areas, so you get this beautiful, amazing weather for skiing that isn’t super cold.” (The average daytime high in January is 36 degrees.)And in a good year, the season can extend well into the spring. “I ski as long as the resort is open — there’s been several years when I skied on July 4,” Stephanie Yu, 49, who lives in Sacramento, said in a phone interview after my trip.A long history and a new nameNo wonder Palisades Tahoe is among the most popular winter destinations in America, even if, technically speaking, it was born only three years ago.The mountain opened in 1949 as Squaw Valley and acquired its neighbor, Alpine Meadows, seven miles away, in 2011. The new entity went by the cumbersome umbrella Squaw Valley Alpine Meadows until it was rebranded as Palisades Tahoe in 2021, to avoid a term that is offensive to many Native Americans.The next year a gondola connecting the base areas at the two mountains was installed; there is also a free on-demand shuttle between the two.Yet part of the Palisades Tahoe draw is how distinct its two components have remained. Palisades is bigger and sleeker, with more and better dining options, an active après scene, activities like disco tubing (which adds party lights and pumping music to regular tubing), and big-time concerts — this year, Diplo was among the performers.The plentiful lifts include a tram and a hybrid known as the Funitel (a mash-up of the French words “funiculaire” and “téléphérique”), and there is an abundance of signature terrain, which, in addition to the KT-22-served runs, includes open steeps off the Headwall and Siberia lifts (unfortunately, among the first to close because of wind) and a bumps minefield named after the local Olympic freestyle skier Jonny Moseley.The Palisades side is so spread out that you can easily move on to another section of the mountain if one gets closed off or too crowded. After struggling with low visibility on my first day, I eventually found better conditions in the Shirley bowl on the back side. Then, to flee both the crowds and the increasingly strong wind, I headed to the Snow King area, tucked away to the far left of the mountain, as you look uphill. From the Red Dog and Far East Express lifts, I made laps on runs that meandered through trees.More complicated was securing a parking spot for my rental car. Palisades Tahoe is part of the Ikon multiresort pass and in recent years has experienced an increase in crowds and traffic. Palisades visitors who don’t stay on-mountain tend to favor Truckee, a town 11 miles away, but Route 89 from there to Palisades can easily turn into a long ribbon of vehicles. (I stayed seven miles from the resort in the other direction, in tiny Tahoe City, which offers an easier commute.)To deal with the crunch, Palisades Tahoe has started requiring parking reservations on Saturdays, Sundays and select holidays. You can book a spot for $30 or try your luck when free reservations open on the Tuesday before the weekend, with sign-up windows at 12 p.m. and 7 p.m. On my first attempt, I hadn’t even completed setting up my account before all the spaces were gone in 12 minutes. A few hours later, it took only six minutes for them to fill up, but I was ready and got a free spotUnassuming AlpineCompared with the Palisades side’s extroverted, big personality, Alpine still feels like an unassuming locals’ hill, with a trail map that looks underfed. Don’t underestimate it: “A lot of the best terrain is hike-to only, well hidden to where your average user won’t find it,” said Mark Fisher, who, with another local, runs a site called Unofficial Alpine that reports on the mountain.For a newcomer, though, the layout felt instinctive and easy, and I was able to have fun with the handful of lifts open on my visit, like the punishingly slow two-seater Yellow Chair — where a wild gust made me slide backward when I disembarked.I also got schooled on an innocent-looking blue run off Roundhouse Express, when my skis hopelessly sank into what looked like mounds of fluffy powder but felt like quicksand. Welcome to the notorious heavy snow known as Sierra cement.Yet something was happening. Trees offered shelter when I needed it, the runs were half empty, there were no lines anywhere, and the snow kept falling. I wasn’t even cold.Fine, count me in: There is something to be said about California skiing.Follow New York Times Travel on Instagram and sign up for our weekly Travel Dispatch newsletter to get expert tips on traveling smarter and inspiration for your next vacation. Dreaming up a future getaway or just armchair traveling? Check out our 52 Places to Go in 2024. Source link

0 notes

Photo

The Palisades Tahoe ski resort has a lot going for it: an idyllic location seven miles from Lake Tahoe’s western shore, a peak elevation of 9,050 feet with 2,850 feet of vertical, and 6,000 skiable acres spread over two bases and served by 43 lifts.The famed California destination, which is celebrating its 75th anniversary, has cool, swagger and a wealth of demanding terrain. The resort hosted the 1960 Winter Olympics when it was still called Squaw Valley, and is among the Alpine Ski World Cup’s few regular stops in the United States.Yet at times, it feels as if all people talk about is the weather.Take my first visit to the resort, this past February, which took place in a windy whiteout.On the first day, I rode up the tram from the Palisades base area, then felt my way down the blue runs off the Siberia Express and Gold Coast Express lifts in a sea of white on white. Palisades Tahoe is known for its bowls, chutes and gullies, especially off the KT-22 chair, but I was not ready to venture there essentially blindfolded.While I was trying to find my bearings on Emigrant Face — a bowl-like blue area off one of the highest lifts — a snowboarder zoomed by so fast that he didn’t see a ridge in the fog and took off like an eagle. An eagle that couldn’t fly, because he crashed.Still, against all odds, I was having fun.And so was Joan Collins, 60, from Madison, Wis., whom I met during lunch at the Alpine base area the next day, when it was marginally less foggy but snowing hard. “For me the hardest part was not seeing the horizon, snow blowing in your face so you can’t really see where you’re going,” said Ms. Collins. “But we’ve been hollering all the way down on some of those runs — it’s like a big, powdery playground.”As snow fell relentlessly, parts of the mountain were closed for avalanche mitigation. Several lifts were on hold because of winds that, I later learned, could reach 100 miles per hour on the ridge tops. By noon it was obvious I really should have refreshed my jacket’s waterproofing.My visit coincided with a big dump of snow after an alarmingly dry December and an average January. Not long after, in early March, a major storm dropped eight feet of snow on the resort. Which might sound amazing to powder hounds, except that the roads and lifts were closed.This year, true to form, good conditions allowed the resort to kick off its season five days early in November.First in line for stormsThis yo-yo pattern comes from the resort’s location, 200 miles east of San Francisco. The local mountains, part of the Sierra Nevada range, are first in line when moisture-laden storms travel eastward from the Pacific. And with nothing to slow it down, the unimpeded jet stream can hit Palisades Tahoe with hurricane force. The resort’s relatively low altitude, with a main base at 6,200 feet, helps create conditions that can vary drastically within a single day as well as between the upper and the lower mountains. At least the Palisades base has great easygoing terrain at the top, so beginners and intermediates can enjoy good snow quality instead of being stuck on scraped-out or wet runs at lower elevations.There are other big upsides. When it’s not snowing, “we have really nice weather for a Western ski destination,” said Bryan Allegretto, the Northern Sierra specialist at the forecasting and conditions site OpenSnow. “When the sun’s out, it’s warm relative to a lot of mountain areas, so you get this beautiful, amazing weather for skiing that isn’t super cold.” (The average daytime high in January is 36 degrees.)And in a good year, the season can extend well into the spring. “I ski as long as the resort is open — there’s been several years when I skied on July 4,” Stephanie Yu, 49, who lives in Sacramento, said in a phone interview after my trip.A long history and a new nameNo wonder Palisades Tahoe is among the most popular winter destinations in America, even if, technically speaking, it was born only three years ago.The mountain opened in 1949 as Squaw Valley and acquired its neighbor, Alpine Meadows, seven miles away, in 2011. The new entity went by the cumbersome umbrella Squaw Valley Alpine Meadows until it was rebranded as Palisades Tahoe in 2021, to avoid a term that is offensive to many Native Americans.The next year a gondola connecting the base areas at the two mountains was installed; there is also a free on-demand shuttle between the two.Yet part of the Palisades Tahoe draw is how distinct its two components have remained. Palisades is bigger and sleeker, with more and better dining options, an active après scene, activities like disco tubing (which adds party lights and pumping music to regular tubing), and big-time concerts — this year, Diplo was among the performers.The plentiful lifts include a tram and a hybrid known as the Funitel (a mash-up of the French words “funiculaire” and “téléphérique”), and there is an abundance of signature terrain, which, in addition to the KT-22-served runs, includes open steeps off the Headwall and Siberia lifts (unfortunately, among the first to close because of wind) and a bumps minefield named after the local Olympic freestyle skier Jonny Moseley.The Palisades side is so spread out that you can easily move on to another section of the mountain if one gets closed off or too crowded. After struggling with low visibility on my first day, I eventually found better conditions in the Shirley bowl on the back side. Then, to flee both the crowds and the increasingly strong wind, I headed to the Snow King area, tucked away to the far left of the mountain, as you look uphill. From the Red Dog and Far East Express lifts, I made laps on runs that meandered through trees.More complicated was securing a parking spot for my rental car. Palisades Tahoe is part of the Ikon multiresort pass and in recent years has experienced an increase in crowds and traffic. Palisades visitors who don’t stay on-mountain tend to favor Truckee, a town 11 miles away, but Route 89 from there to Palisades can easily turn into a long ribbon of vehicles. (I stayed seven miles from the resort in the other direction, in tiny Tahoe City, which offers an easier commute.)To deal with the crunch, Palisades Tahoe has started requiring parking reservations on Saturdays, Sundays and select holidays. You can book a spot for $30 or try your luck when free reservations open on the Tuesday before the weekend, with sign-up windows at 12 p.m. and 7 p.m. On my first attempt, I hadn’t even completed setting up my account before all the spaces were gone in 12 minutes. A few hours later, it took only six minutes for them to fill up, but I was ready and got a free spotUnassuming AlpineCompared with the Palisades side’s extroverted, big personality, Alpine still feels like an unassuming locals’ hill, with a trail map that looks underfed. Don’t underestimate it: “A lot of the best terrain is hike-to only, well hidden to where your average user won’t find it,” said Mark Fisher, who, with another local, runs a site called Unofficial Alpine that reports on the mountain.For a newcomer, though, the layout felt instinctive and easy, and I was able to have fun with the handful of lifts open on my visit, like the punishingly slow two-seater Yellow Chair — where a wild gust made me slide backward when I disembarked.I also got schooled on an innocent-looking blue run off Roundhouse Express, when my skis hopelessly sank into what looked like mounds of fluffy powder but felt like quicksand. Welcome to the notorious heavy snow known as Sierra cement.Yet something was happening. Trees offered shelter when I needed it, the runs were half empty, there were no lines anywhere, and the snow kept falling. I wasn’t even cold.Fine, count me in: There is something to be said about California skiing.Follow New York Times Travel on Instagram and sign up for our weekly Travel Dispatch newsletter to get expert tips on traveling smarter and inspiration for your next vacation. Dreaming up a future getaway or just armchair traveling? Check out our 52 Places to Go in 2024. Source link

0 notes

Photo

The Palisades Tahoe ski resort has a lot going for it: an idyllic location seven miles from Lake Tahoe’s western shore, a peak elevation of 9,050 feet with 2,850 feet of vertical, and 6,000 skiable acres spread over two bases and served by 43 lifts.The famed California destination, which is celebrating its 75th anniversary, has cool, swagger and a wealth of demanding terrain. The resort hosted the 1960 Winter Olympics when it was still called Squaw Valley, and is among the Alpine Ski World Cup’s few regular stops in the United States.Yet at times, it feels as if all people talk about is the weather.Take my first visit to the resort, this past February, which took place in a windy whiteout.On the first day, I rode up the tram from the Palisades base area, then felt my way down the blue runs off the Siberia Express and Gold Coast Express lifts in a sea of white on white. Palisades Tahoe is known for its bowls, chutes and gullies, especially off the KT-22 chair, but I was not ready to venture there essentially blindfolded.While I was trying to find my bearings on Emigrant Face — a bowl-like blue area off one of the highest lifts — a snowboarder zoomed by so fast that he didn’t see a ridge in the fog and took off like an eagle. An eagle that couldn’t fly, because he crashed.Still, against all odds, I was having fun.And so was Joan Collins, 60, from Madison, Wis., whom I met during lunch at the Alpine base area the next day, when it was marginally less foggy but snowing hard. “For me the hardest part was not seeing the horizon, snow blowing in your face so you can’t really see where you’re going,” said Ms. Collins. “But we’ve been hollering all the way down on some of those runs — it’s like a big, powdery playground.”As snow fell relentlessly, parts of the mountain were closed for avalanche mitigation. Several lifts were on hold because of winds that, I later learned, could reach 100 miles per hour on the ridge tops. By noon it was obvious I really should have refreshed my jacket’s waterproofing.My visit coincided with a big dump of snow after an alarmingly dry December and an average January. Not long after, in early March, a major storm dropped eight feet of snow on the resort. Which might sound amazing to powder hounds, except that the roads and lifts were closed.This year, true to form, good conditions allowed the resort to kick off its season five days early in November.First in line for stormsThis yo-yo pattern comes from the resort’s location, 200 miles east of San Francisco. The local mountains, part of the Sierra Nevada range, are first in line when moisture-laden storms travel eastward from the Pacific. And with nothing to slow it down, the unimpeded jet stream can hit Palisades Tahoe with hurricane force. The resort’s relatively low altitude, with a main base at 6,200 feet, helps create conditions that can vary drastically within a single day as well as between the upper and the lower mountains. At least the Palisades base has great easygoing terrain at the top, so beginners and intermediates can enjoy good snow quality instead of being stuck on scraped-out or wet runs at lower elevations.There are other big upsides. When it’s not snowing, “we have really nice weather for a Western ski destination,” said Bryan Allegretto, the Northern Sierra specialist at the forecasting and conditions site OpenSnow. “When the sun’s out, it’s warm relative to a lot of mountain areas, so you get this beautiful, amazing weather for skiing that isn’t super cold.” (The average daytime high in January is 36 degrees.)And in a good year, the season can extend well into the spring. “I ski as long as the resort is open — there’s been several years when I skied on July 4,” Stephanie Yu, 49, who lives in Sacramento, said in a phone interview after my trip.A long history and a new nameNo wonder Palisades Tahoe is among the most popular winter destinations in America, even if, technically speaking, it was born only three years ago.The mountain opened in 1949 as Squaw Valley and acquired its neighbor, Alpine Meadows, seven miles away, in 2011. The new entity went by the cumbersome umbrella Squaw Valley Alpine Meadows until it was rebranded as Palisades Tahoe in 2021, to avoid a term that is offensive to many Native Americans.The next year a gondola connecting the base areas at the two mountains was installed; there is also a free on-demand shuttle between the two.Yet part of the Palisades Tahoe draw is how distinct its two components have remained. Palisades is bigger and sleeker, with more and better dining options, an active après scene, activities like disco tubing (which adds party lights and pumping music to regular tubing), and big-time concerts — this year, Diplo was among the performers.The plentiful lifts include a tram and a hybrid known as the Funitel (a mash-up of the French words “funiculaire” and “téléphérique”), and there is an abundance of signature terrain, which, in addition to the KT-22-served runs, includes open steeps off the Headwall and Siberia lifts (unfortunately, among the first to close because of wind) and a bumps minefield named after the local Olympic freestyle skier Jonny Moseley.The Palisades side is so spread out that you can easily move on to another section of the mountain if one gets closed off or too crowded. After struggling with low visibility on my first day, I eventually found better conditions in the Shirley bowl on the back side. Then, to flee both the crowds and the increasingly strong wind, I headed to the Snow King area, tucked away to the far left of the mountain, as you look uphill. From the Red Dog and Far East Express lifts, I made laps on runs that meandered through trees.More complicated was securing a parking spot for my rental car. Palisades Tahoe is part of the Ikon multiresort pass and in recent years has experienced an increase in crowds and traffic. Palisades visitors who don’t stay on-mountain tend to favor Truckee, a town 11 miles away, but Route 89 from there to Palisades can easily turn into a long ribbon of vehicles. (I stayed seven miles from the resort in the other direction, in tiny Tahoe City, which offers an easier commute.)To deal with the crunch, Palisades Tahoe has started requiring parking reservations on Saturdays, Sundays and select holidays. You can book a spot for $30 or try your luck when free reservations open on the Tuesday before the weekend, with sign-up windows at 12 p.m. and 7 p.m. On my first attempt, I hadn’t even completed setting up my account before all the spaces were gone in 12 minutes. A few hours later, it took only six minutes for them to fill up, but I was ready and got a free spotUnassuming AlpineCompared with the Palisades side’s extroverted, big personality, Alpine still feels like an unassuming locals’ hill, with a trail map that looks underfed. Don’t underestimate it: “A lot of the best terrain is hike-to only, well hidden to where your average user won’t find it,” said Mark Fisher, who, with another local, runs a site called Unofficial Alpine that reports on the mountain.For a newcomer, though, the layout felt instinctive and easy, and I was able to have fun with the handful of lifts open on my visit, like the punishingly slow two-seater Yellow Chair — where a wild gust made me slide backward when I disembarked.I also got schooled on an innocent-looking blue run off Roundhouse Express, when my skis hopelessly sank into what looked like mounds of fluffy powder but felt like quicksand. Welcome to the notorious heavy snow known as Sierra cement.Yet something was happening. Trees offered shelter when I needed it, the runs were half empty, there were no lines anywhere, and the snow kept falling. I wasn’t even cold.Fine, count me in: There is something to be said about California skiing.Follow New York Times Travel on Instagram and sign up for our weekly Travel Dispatch newsletter to get expert tips on traveling smarter and inspiration for your next vacation. Dreaming up a future getaway or just armchair traveling? Check out our 52 Places to Go in 2024. Source link

0 notes

Text

Bridge of the Gods in Cascade Locks Oregon

The bridge road is this grate so you can see the river under you as you walk over the bridge.

No side walks on this bridge, watch out for the vehicles that you share the bridge with,

We walked over the bridge on May 16, 2022

Sherrylephotography May 16, 2022

Cascade Locks Oregon. Views from the Bridge of the Gods.

Legend of Bridge of the Gods

Long before recorded history began, the Native American legend of the Bridge of the Gods says the Great Spirit built a bridge of stone that was a gift of great magnitude. The Great Spirit, named Manito, placed a wise old woman named Loo-Wit, on the bridge as its guardian. He then sent to earth his three sons, Multnomah, the warrior; Klickitat (Mount Adams), the totem-maker; and Wyeast (Mount Hood), the singer. Peace lived in the valley until beautiful Squaw Mountain moved in between Klickitat and Wyeast. The beautiful woman mountain grew to love Wyeast, but also thought it fun to flirt with his big brother, Klickitat. Soon the brothers began to quarrel over everything, stomping their feet and throwing fire and rocks at each other. Finally, they threw so many rocks onto the Bridge of the Gods and shook the earth so hard that the bridge broke in the middle and fell in to the river.

Klickitat, who was the larger of the two mountains, won the fight, and Wyeast admitted defeat, giving over all claim to beautiful Squaw Mountain. In a short time, Squaw Mountain became very heartbroken for she truly loved Wyeast. One day she fell at Klickitat’s feet and sank into a deep sleep from which she never awakened. She is now known as the Sleeping Beauty and lies where she fell, just west of Mount Adams.

During the war between Wyeast and Klickitat, Loo-Wit, the guardian of the bridge, tried to stop the fight. When she failed, she stayed at her post and did her best to save the bridge from destruction, although she was badly burned and battered by hot rocks.

When the bridge fell, she fell with it. The Great Spirit placed her among the great snow mountains, but being old in spirit, she did not desire companionship and so withdrew from the main range to settle by herself far to the west. Today you will find her as Mount St. Helens, the youngest mountain in the Cascades.

Scientists say that about 1,000 years ago, the mountain on the Washington side of the Columbia River, near what is now the town of Stevenson, caved off, blocking the river. The natural dam was high enough to cause a great inland sea covering the prairies as far away as Idaho. For many years, natural erosion weakened the dam and finally washed it out. These waters of the inland sea rushed out, tearing away more of the earth and rocks until a great tunnel was formed under the mountain range leaving a natural bridge over the water. The bridge was called “The Great Cross Over” and is now named “The Bridge of the Gods.”

LEGEND: an unverifiable story handed down by tradition from earlier times and popularly accepted as historical

Material for this article provided by the Port of Cascade Locks, Oregon

Click here for more information on the bridge and the Legend of the Bridge of the Gods

#information from https://columbiagorgetomthood.com/2020/07/04/legend-bridge-of-the-gods/#photographers on tumblr#sherrylephotography#landscape photography#my photography#bridge of the gods#ledgend#oregon#lock cascade

113 notes

·

View notes

Text

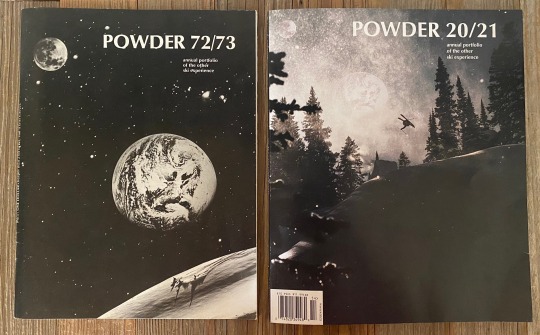

Powder Magazine

(Written by Sam Cox - December 28, 2020)

Growing up in Montana, my winter free time was consumed by skiing. Big Sky was the destination when I was barely old enough to walk. Eventually we made the move to Bozeman and Bridger Bowl became my second home. During the early years, my family made the trek to a handful of Warren Miller movies when they were on tour in the fall and Snow Country was the magazine subscription that landed on the coffee table. I was vaguely aware of Jackson Hole, Snowbird and Squaw Valley and my father would occasionally regale me with tales of skiing (read Après) in Germany when he was in the Army. At some level, I already understood that there was something special about Bridger, but realistically, my sphere of outside influence was quite small. Christmas of 1989 turned my entire world upside down. My aunt and uncle are longtime Salt Lake City residents and Brighton skiers. Typically they would send a package each year with the customary cookies, toffee and a card. However, this year they sent two VHS tapes and a magazine - Ski Time, Blizzard of Aahhh’s and a copy of Powder. Things would never be the same for me. Scot Schmidt became my hero, Greg Stump was taking skiing into uncharted territory and above it all, Powder created an eloquent voice for our sport and was the fabric that held things together. Even at my young age, everything that I’d intuitively sensed before was distilled into a potent desire to devote myself to the simple pursuit of being a skier.

Johan Jonsson, Engelberg, Switzerland - Photo: Mattias Fredriksson/POWDER

Powder was founded in Sun Valley by the Moe brothers in 1972 as an annual portfolio of The Other Ski Experience. After several years of running the magazine, Jake and David Moe sold Powder to the owner of Surfer Magazine. A repurposed aircraft hangar in San Juan Capistrano became the new home of skiing’s most prestigious publication. Over time, there was an ebb and flow to the size of staff and cast of characters, each person leaving their unique mark. For decades Powder weathered corporate acquisitions, office relocations and the constant metamorphosis of the ski industry - never losing its voice, Powder remained the benchmark. It was a source of creativity, inspiration and a defacto annal of history. For many it was also a shining beacon, a glimpse into a world filled with deep turns and iconic destinations - even if this world could only be inhabited inside the constructs of your imagination.

My story and the impact Powder had on the direction I would take is hardly unique. The magazine left an indelible impression on countless skiers. When the news broke this fall that operations were being suspended indefinitely, a heartbroken community took to social media to pay homage to the magazine and how it changed their lives and in some cases, careers. This is my version of a tribute and it’s definitely not perfect. In order to gain some perspective, I reached out to former staff members - a collective I admire and respect. It’s an attempt to articulate the essence of Powder, capture its influence on the skiing landscape and give credit to the people who made it come to life.

Bernie Rosow, Mammoth Mountain, CA - Photo: Christian Pondella/POWDER

HANS LUDWIG - The Jaded Local

“Skiing has always been really tribal and one of the last vestiges of having an oral history. Powder was a unique concept, because they weren’t really concerned with the family market. They were just concerned about being really into skiing. Growing up in Colorado and skiing moguls, my coaches Robert and Roger were featured in the early Greg Stump films. Being in their orbit, I knew a little bit about skiing culture and what was going on out there, but didn’t have the whole picture. The Stump films resonated with me, but Ski/Skiing Magazines didn’t really do it for me. Powder was the door that opened things culturally, it was the only entry point before Blizzard of Aahhh’s.”

“Something that nobody gives Powder credit for, is sponsoring the Greg Stump, TGR and MSP movies and giving them full support right from their inception. It legitimized those companies and helped them become one of the catalysts for change and evolution in skiing. Ultimately this change would have happened, but at a much slower pace without the support of Powder. Getting support from Powder meant they’d weeded out the posers and kooks and what they were backing wasn’t something or someone that was “aspiring” they were a cut above.”

“Powder brought a lot of things into the mainstream, raised awareness and helped to legitimize them: Jean-Marc Boivin, Patrick Vallencant, Pierre Tardivel, telemarking, monoskiing, snowboarding, the JHAF, Chamonix, La Grave, Mikaela Shiffrin, fat skis pre McConkey, skiing in South America….the list goes on.”

“I had some rowdy trips with Powder. Writing “Lost In America,” I went Utah-Montana-Fernie-Banff-Revelstoke via pickup truck, only backcountry skiing and camping in the mud. It was a month plus. I did another month plus in Nevada, which was after back to back Jackson and Silverton. Total time was two plus months. That was fucked up, I was super loose after that whole thing. So many sketchy days with total strangers”

“People forget that Powder was around long before the advent of the fucking pro skier. Starting in 1996, the magazine was in the impact zone of the ski industrial complex. There is limited space for content each season. It was a challenge to balance the pressure coming from the athletes and brands to cover something that was going to make them money vs. staying true to the Moe brothers original intent and profiling an eccentric skier, a unique location or even fucking ski racing.”

Full Circle - Photo: MJ Carroll

KEITH CARLSEN - Editor

“When I was young, Ski/Skiing didn’t do anything for my spirit, but Powder lit me up. It ignited a passion in diehard skiers and gave them a voice and community. It was focused on the counter culture - the type of people who rearrange their lives to ski. This was in direct opposition to other magazines that were targeting rich people, trying to explain technique, sell condos or highlight the amenities at a ski area.”

“Skiing has always been my outlet and mechanism to get away from things in life. My two talents are writing and photography, so I enrolled at Western State with the direct goal of landing an internship at Powder. Even at 19, I had complete focus on the direction I wanted to take. If it didn’t work out, my backup plan was to be a ski bum. 48 hours after graduating, I was headed to southern California to live in my van and start my position at Powder. When the decision was made to close the magazine, it was really personal for me. Powder had provided me direction in life for the last 30 years and I needed some time to process it. In a way, it was almost like going to a funeral for a good friend - even though it’s gone, the magazine lives on in all of us and can never be taken away.”

“It was, and will always remain, one of my life’s greatest honors to serve as the editor-in-chief for Powder Magazine. It was literally a dream that came true. I’m so grateful for everyone who came before me and everyone who served after me. That opportunity opened literally hundreds of doors for me and continues to do so today. I owe the magazine a massive debt of gratitude. Every single editor was a warrior and fought for the title with their lives. They were doing double duty - not only from competition with other publications, but the internal struggle of budget cuts, staff reductions and trying to do more with less. Powder never belonged in the hands of a corporation. The magazine spoke to an impassioned community and never made sense to an accountant or on a ledger.”

Trevor Petersen, Mt. Serratus, BC - Photo: Scott Markewitz/POWDER

SIERRA SHAFER - Editor In Chief

“Powder celebrated everything that is good and pure in skiing. It highlighted the old school, the new and the irreverent. The magazine also called bullshit when they saw it. It was a checkpoint, a cultural barometer and an honest reflection on where skiing has been and where it’s going.”

“My involvement with Powder came completely out of left field. I was never an intern or established in the ski industry. My background was strictly in journalism, I was a skier living in Southern California and editing a newspaper. I knew that I wanted to get the fuck out of LA and Powder was that opportunity. It was a huge shift going from my job and life being completely separate to work becoming my life. Literally overnight, Powder became everything - friends, connections and part of my identity. It derailed my trajectory in the best possible way.”

Brad Holmes, Donner Pass, CA - Photo: Dave Norehad/POWDER

MATT HANSEN - Executive Editor

“Keith Carlsen was a man of ideas, he had tremendous vision and influence. He came up with the ideas for Powder Week and the Powder Awards in 2001. In some respects those two events saved the magazine.”

“Powder was the soul of skiing and kept the vibe, it changed people’s lives and inspired them to move to a ski town. As a writer I always wanted to think it was the stories that did that, but in truth it was the photography. Images of skiing truly became an art form, 100% thanks to Powder Magazine and Dave Reddick. Dave cultivated and mentored photographers, he was always searching for the unpredictable image from around the world and pressed the photographers to look at things from a different angle.”

“It sounds cliche, but writing a feature about Chamonix was the highlight for me. Sitting on the plane, things were absolutely unreal. I linked up with Nate Wallace and the whole experience from start to finish was out of my comfort zone. Ducking ropes to ski overhead pow on the Pas De Chèvre, walking out of the ice tunnel on a deserted Aiguille du Midi right as the clouds parted, late nights in town that were too fuzzy to recall. The energy of the place taught me a lot. I didn’t have a smartphone and there was no Instagram - I had time to write, observe, take notes and be present with who I was and with the experience. As a writer it didn’t get any better.”

“The true gift of working for Powder, was the once in a lifetime adventures that I wish I could have shared with my family, I was so lucky to have had those opportunities. It almost brought tears to me eyes.”

Peter Romaine, Jackson Hole, WY - Photo: Wade McKoy/POWDER

DAVE REDDICK - Director of Photography

“Just ski down there and take a photo of something, for cryin’ out loud!” “I’ve found that channeling McConkey has been keeping it in perspective. Powder’s been shuttered. That sucks. What doesn’t suck is the good times and the people that have shared the ride thus far and I’m just thankful to be one of them. There’s been some really kind sentiments from friends and colleagues, but this must be said - Every editor (especially the editors), every art director (I’ve driven them nuts), every publisher and sales associate, every photographer, writer, and intern, and all the others behind the scenes who’ve ever contributed their talents get equal share of acknowledgment for carrying the torch that is Powder Mag. There’s hundreds of us! No decision has ever been made in a vacuum. Always a collective. At our best, we’ve been a reflection of skiers everywhere and of one of the greatest experiences in the world. It’s that community, and that feeling, that is Powder. I’m not sure what’s next and I’m not afraid of change but” “There’s something really cool about being scared. I don’t know what!”

Scot Schmidt, Alaska - Photo: Chris Noble/POWDER

DEREK TAYLOR - Editor

“Powder was the first magazine dedicated to the experience and not trying to teach people how to ski. It was enthusiast media focused on the soul and culture. It’s also important to highlight the impact Powder had outside of skiing - today you have the Surfer’s Journal effect where every sport wants that type of publication. However, prior to their inception, everybody wanted a version of Powder.”

“Neil Stebbins and Steve Casimiro deserve a lot of credit for the magazine retaining its voice and staying true to the core group of skiers it represented.”

“Keith Carlsen is responsible for the idea behind Super Park. This was a time when skiing had just gone through a stale phase. There was a newfound energy in park skiing and younger generations, this event helped to rebrand Powder and solidify its goal of being all inclusive. Racing, powder, park, touring - it’s all just skiing.”

Joe Sagona, Mt. Baldy, CA - Photo: Dave Reddick/POWDER

JOHNNY STIFTER - Editor In Chief

“What did Powder mean to me... Well, everything. As a reader and staffer, it inspired me and made me laugh. I learned about local cultures that felt far away and learned about far away cultures that didn’t feel foreign, if that makes sense.”

“But I cherished those late nights the most, making magazines with the small staff. Despite the deadline stress, I always felt so grateful to be working for this sacred institution and writing and editing for true skiers. We all just had so much damn fun. And it didn’t hurt meeting such passionate locals at hallowed places, like Aspen and Austria, that I once dreamed of visiting and skiing. The Powder culture is so inclusive and so fun, I never felt more alive.”

Doug Coombs, All Hail The King - Photo: Ace Kvale/POWDER

HEATHER HANSMAN - Online Editor

“Powder is a lifestyle and an interconnected circle of people. It’s about getting a job offer at Alta, opening your home to random strangers, locking your keys in your car and getting rescued by a friend you made on a trip years ago. Through the selfish activity of skiing, you can create a community of people you cherish and can depend on through highs and lows.”

Ashley Otte, Mike Wiegele Heli, BC - Photo: Dave Reddick/POWDER

The contributions of so many talented individuals made the magazine possible. I would like to express my sincere gratitude to everyone who shared their experience at Powder with me. Also, I want to thank Porter Fox and David Page for crafting inspiring feature stories that I enjoyed immensely over the years.

After the reality set in that the final issue had arrived, a void was created for generations of skiers. I’ve been focused on being thankful for what we had, rather than sad it’s gone. It’s a challenging time for print media and I wholeheartedly advocate supporting the remaining titles in anyway you can. In a culture driven by a voracious appetite for mass media consumption and instant gratification - I cherish the ritual of waiting for a magazine to arrive, appreciating the effort that went into creating the content and being able to have that physical substance in my hand. Thanks for everything Powder, you are missed, but your spirit lives on.

Captain Powder - Photo: Gary Bigham/POWDER

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

hunting

Website: https://www.squawmountainranch.com/

Address: 2576 Squaw Mountain Rd, Jacksboro, TX 76458

Phone: +1 (830) 275-3277

Today, SMR is offering some of the best Texas Trophy Whitetail Hunting and Exotic Hunting opportunities in all of Texas, along with Bird, Turkey, Hog, Varmint, and More Hunts including: Trophy Elk, Axis Deer, Scimitar Oryx, Blackbuck Antelope, Fallow Deer, Addax, Aoudad, Buffalo, White Buffalo, Corsican Rams, Black Hawaiian, Bongo, Blesbok, Catalina Goats, Eland, Four-Horned Sheep, Gazelle, Gemsbok, Himalayan Tahr, Impala, Hybrid Ibex, Kudu, Markhor, Mouflon Ram, Nyala, Nubian Ibex, Red Stag, Red Lechwe, Sable, Spanish Goats, Springbok, Texas Dall Ram, Transcaspian Urial, Wildebeest, Zebra and other African game to the discriminating hunter. Located in Jack County, less than 2 hours from the Dallas/Fort Worth Metroplex, Squaw Mountain Ranch offers premier Big Texas Whitetail Hunting Operation providing an experience of a lifetime to all hunters.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Native Americans: Yellowstone Renames Mountain Linked to Massacre of Native Americans

Peak renamed First Peoples Mountain was known as Mount Doane after Gustavus Doane who led attack that killed 173 people in 1870

— Victoria Bekiempis | Tuesday 14 June 2022

Yellowstone national park. Photograph: Matthew Brown/AP

Yellowstone national park has renamed the peak that was once known as Mount Doane to First Peoples Mountain, in a decision to strip from the famed wildlands an “offensive name” evoking the murders of nearly 200 Native Americans, officials said.

In a 9 June announcement, National Park Service authorities also said they might weigh similar renamings in the future.

The 10,551-ft mountain had been named after Gustavus Doane, a US army captain. Doane was a “key member” of an 1870 expedition before Yellowstone became the country’s first national park, authorities said.

But earlier the same year of the expedition, Doane helmed an attack on a band of Piegan Blackfeet in retaliation for the purported murder of a white furrier. This assault, now known as the Marias Massacre, resulted in the killing of at least 173 Native Americans, authorities said.

The victims included numerous women, elders and children who contracted smallpox. “Doane wrote fondly about this attack and bragged about it for the rest of his life,” the National Park Service said.

The new First Peoples name was “based on recommendations from the Rocky Mountain Tribal Council, subsequent votes within the Wyoming Board of Geographic names, and [support] of the National Park Service,” officials added. These entities ultimately forwarded this name to the US Board on Geographic Names this month.

That board, which is responsible for maintaining uniformity in geographic name usage across the federal government, voted 15-0 to affirm the renaming, officials said. Yellowstone recently reached out to the 27 tribes associated with the park and “received no opposition to the change nor concerns”.

“Yellowstone may consider changes to other derogatory or inappropriate names in the future,” officials also said in their announcement.

This renaming comes as the US Department of the Interior ramps up efforts to rename hundreds of geographic formations deemed to be offensively titled. The interior secretary, Deb Haaland, the first Native American to hold a cabinet secretary position, issued an order in November 2021 that officially declared “squaw” to be a “derogatory” word.

Haaland’s order required that the Board of Geographic Names come up with a process to remove that word from federal use. The department, in February of this year, released a list of potential replacement names for more than 660 geographic sites which included the word.

She also issued an order that created a federal advisory committee “to broadly solicit, review, and recommend changes to other derogatory geographic and federal land unit names”.

“Words matter, particularly in our work to make our nation’s public lands and waters accessible and welcoming to people of all backgrounds,” Haaland said. “Consideration of these replacements is a big step forward in our efforts to remove derogatory terms whose expiration dates are long overdue.”

The renaming of geographic formations comes amid a push to remove Confederate symbols across the US in the wake of George Floyd’s murder in May 2020. More than 200 Confederate monuments and memorials have been renamed, removed, or relocated, according to the New York Times.

0 notes

Link

0 notes

Photo

We get out of dodge one step ahead of the next big storm coming into the mountains. (at Squaw Valley, Lake Tahoe) https://www.instagram.com/p/CcajSEWrXuE/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

0 notes

Text

Some of the Largest Ski Resorts

Ski Resorts are towns and villages in winter sports areas that provide housing, equipment rental, ski schools, and ski lifts for skiing and snowboarding. There are many ski resorts in the United States. As of 2021, there were 470 skiing locations in the United States in operation. New York State has the highest number of ski resorts in the United States, with 49 ski resorts. Michigan comes in the second position, with 39 ski resorts. Wisconsin and Colorado come in the third position with 30 ski resorts each. Here are the largest ski resorts in the United States. Park City, Utah, is one of the ski areas in the United States. Park City, Utah, is the classic ski town due to its close access to a major airport, its array of pubs and restaurants, and its ability to appeal to the wealthy and the average person. Vail bought Park City Mountain Resort in 2015 and united it with Canyons Resort, resulting in the largest ski area in America (about 7,300 acres). The second-largest ski resort in the United States is the Big Sky resort in Montana. Big Sky, Montana's ski resort, was formerly the largest in the United States, but Park City, Utah's expanding ski resort, has surpassed it. Big Sky did something similar to Park City a few years back when it absorbed its defunct neighbor Moonlight Basin, resulting in a 5,800-acre ski resort with the moniker "America's Biggest Skiing." Big Sky is connected to a 2,200-acre ski resort by lifts and ski slopes. It now has 8,000 acres, making it the largest in the United States and the second-largest in North America. The catch is that the Yellowstone Club owns the added acres. To become a member of the Yellowstone Club, one will have to invest millions of dollars in the property. The next on the list is the Vail resort in Colorado. Vail, Colorado, was formerly the third-largest ski resort in North America and the second-largest ski resort in the United States but fell to fourth following Park City's $50 million expansion. It has a total area of 5,289 acres. The fourth-largest ski resort in the United States is the Heavenly Mountain Resort in California. With 4,800 acres, Heavenly Mountain Resort, another Vail Resorts ski resort that straddles the California-Nevada border. The Mt Bachelor in Oregon comes in fifth place. Mt Bachelor in Oregon recently expanded its terrain by 500 acres. It has grown to 3,683 acres, putting it in the fifth position in the United States and eighth in North America in terms of size. Mt Bachelor has twelve ski lifts in operation. Tubing, snowshoeing, and dog-sledding trips are also available at the resort. The Squaw Valley Ski Resort in California is the sixth largest ski resort in the United States and the ninth position in North America. It has a landmass of 3600 acres. The seventh-largest ski resort in the United States is Mammoth Mountain in California. It is also the tenth-largest ski resort in North America. The Mammoth Mountain has a landmass of 3500 acres, only 100 acres smaller than the Squaw Valley resort.

0 notes

Text

Tahoe Chips

Toga Chip Gal and I went on a vacation, felt more like a second honeymoon, to Lake Tahoe, which is truly God's country. While there, in the breezeway of a local super market chain, Raley's, we discovered a display for Tahoe Chips. I contacted the owner of the company, Tom Keefer, to learn about his company.

Tom, along with his brother Mike and their childhood friend Dan Brinker have created many brands, including Wild California, but Tahoe Chips was Tom's creation. Since he was five years old, Tom has lived, worked and played in Lake Tahoe. In 2015, Tom developed Tahoe Chips to celebrate his favorite place with the hope that the company will be successful enough that he will be able give back by donating a portion of the proceeds to a local charity. This explains the company's name, Friends of Tahoe.

The product has been on the market since 2017. The chips come in the following four flavors: Bar-B-Que, Jalapeno, Salt & Vinegar and Sea Salt,

The company's motto is "Crisp as the Lake." Tom explained that when you jump into Lake Tahoe, its cold and that feeling inspired the tagline. The bags display some of the major the activities in the Lake Tahoe area: biking, hiking, sailing, and skiing.

Currently the chips are available at select Raley's and Safeway grocery stores as well as about 60 independent stores in the San Francisco Bay area of California. The company's billing name is Blue Water Foods, as Lake Tahoe is one of the bluest lakes in the world. The AAA Nevada Tour Book provides the following description of Lake Tahoe.

Lake Tahoe was named "big water" by the Washoe Indians. According to Washoe legend, it was created during the pursuit of an innodent Native American man by an Evil Spirit. In an attempt to ward off the Evil Spirit, the Great Spirit bestowed upon the pursued man a branch of leaves, promising that each leaf dropped would magically produce a body of water that would impede the Evil Spirit's chase. The man, however, dropped the entire branch in fright, creating the giant lake.

It is estimated that Lake Tahoe holds enough water to cover the entire state of California to a depth of 14 inches, its average depth is 989 feet; the deepest point is 1,645 feet, making Tahoe the third deepest lake in North America. The water is remarkably clear, deep blue and also 97 percent pure - nearly the same level as distilled water. The first 12 feet below the surface can warm to 68 F in summer, while depths below 700 feet remain at a constant temperature of 39 F.

Twelve miles wide and 22 miles long, this "lake in the sky" straddles the California/Nevada line at an elevation of 6,229 feet. It lies in a valley between the Sierra Nevada range and an eastern offshoot, the Carson Range. The mountains, which are snow-capped except in late summer, rise more than 4,000 feet above Tahoe's resort-lined shore. Most of the surrounding region is covered by the Eldorado, Humboldt-Toiyabe and Tahoe national forests.

Immigrants and miners were lured to the rugged Sierras by tales of fortunes made during the California gold rush. The discovery of the Comstock Lode increased traffic and depleted the Tahoe Basin's natural resources to a dangerously low level. Between 1860 and 1890 lumber was needed for fuel and to support the web of mines constructed beneath Virginia City, Nev. The subsequent decline of the Comstock Lode spared many thousands of trees.