#Apparently only Griffith's dreams are worth considering

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

"Casca deserves better!!!!" Yet some of yall think Guts is still good enough to be shipped with Griffith.

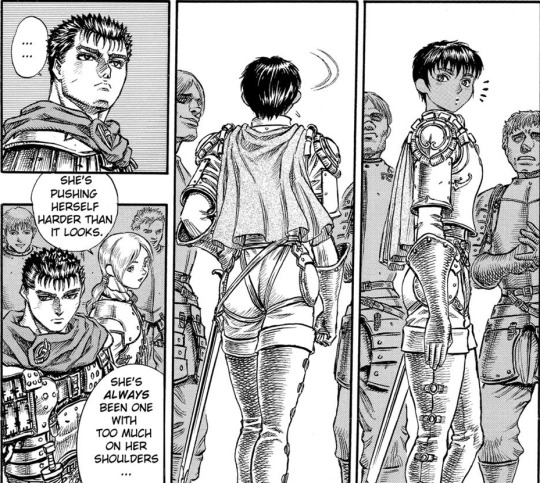

Post eclipse 97% of the series Guts is devoted to protecting and avenging her and SHE knew this when she woke up. Lost an eye and an arm her AND willing to lose more. Which is why she's STILL head over heels in love with him because she knows his true character.

Casca of all people knows what it's like too be mentally ill and she still loves him dispite his lows. But of course Casca's feelings needs to be ignored come on there is TOXIC YAOI at stake here!!!

You are NOT feminist ignoring Casca's feelings for Guts. It's always men's feelings > women's feelings for fujoshis. Then to LIE and say you care about Casca... The same people who are hating her current arc where she grows and comes to terms with the eclipse and Griffth's betrayal.

#Casca DOES deserve better which is why Guts does everything to be a better man for her.#All SA is wrong and Guts knows that which is why he won't allow himself to get to a point to be that way again.#Guts the man you are ... can't say the same for the other man#Anti berserk fujoshis that pretends to care about Casca.#“Casca should leave Guts” straight out of the fujoshi handbook#Apparently only Griffith's dreams are worth considering#Anti griffguts#Gutsca#Guts#Casca#Berserk#anti griffith

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rambles about The Golden Age Arc - Part 2

As a sidenote, I don’t much care for the 1997 anime. I actually like the OVAs better because to my mind neither is great as an adaptation, but at least the OVAs are fanservicey eyecandy.

The big issue I have with the 97 anime is that it adds some stuff and it takes some stuff out, which is normal for an adaptation, but it does kind of change the tone and flow of the story and the relationships... which again is normal for an adaptation BUT...

Because so many people consider it to be an extremely accurate adaptation sometimes I wonder if the interpretations devised through watching the 97 anime get stuck in people’s brains when reading the manga or at least color their interpretations.

Just my pre “read more” thought of the day. Now, on to...

Rambles about The Golden Age Arc - Part 2

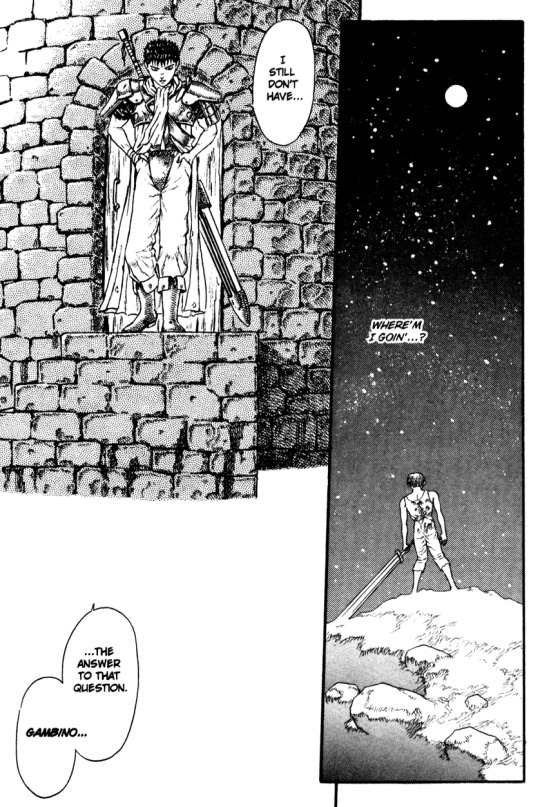

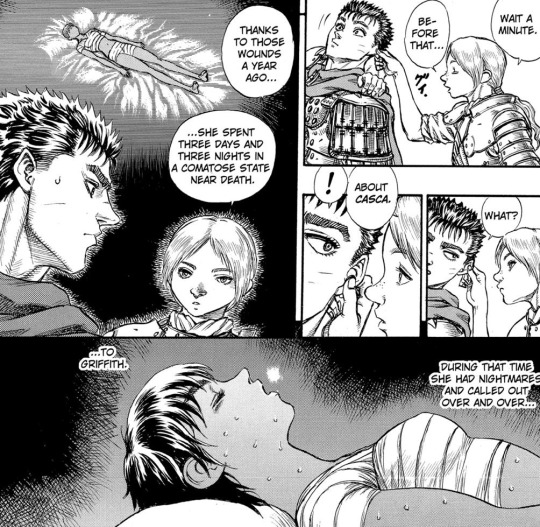

1. The nightmares are another thing I rather miss - I think the big difference between early Berserk and later Berserk for ME isn’t so much the quality as the emphasis. Early berserk spent a lot more time on characters’ inner worlds and struggles whereas later Berserk has a lot more i guess camaraderie and adventure. One of the things that really breaks my heart about Miura’s passing - one of many things - is that I did feel like they were starting to trend back a bit toward dealing with these things (e.g. Casca’s mindscape and then her flashbacks), not to mention that the last chapter he wrote was the one that brought the primary relationship back into focus after what, 15 years? He had given an interview where he stated this as well - that it was time to start bringing the focus back to Guts and Griffith. Well I can’t think about this too much since it’ll just depress me, but anyway I...

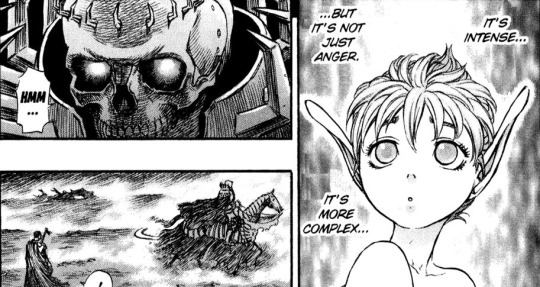

Appreciate the dream logic he uses in these sequences - the way Guts’ self image is revealed through the imagery, e.g. here we see that he still sees himself as something of a vulnerable child seeking help and approval -- all of which is pretty important for the things to come.

2. The thing with Casca lying in bed with him is also VERY ODD if you consider that Miura didn’t intend to get them together at this point?? He did mention that a lot of times things just come together as though he meant to do them even though he didn’t. In any case I do think it’s noteworthy that the reason she can touch him is because she’s a woman - obviously this comes up later during their sex scene.

Also Griffith is weird, he could have just piled blankets on Guts, you know? What the hell, Griffith.

3. Anyway, straight up, day one, Griffith is already being weird about Guts. Apparently even just asking to talk to him alone is strange considering everyone seems surprised by it.

4. And this is something that comes up when Guts leaves in a few volumes, but I do think it’s very much worth noting: The Band of the Hawk was an undefeated monster of a merc group before Guts even got there. Obviously Guts is by far the strongest individual asset in the group, but I don’t really think they accomplished anything with him that they absolutely couldn’t have done without him... well maybe Boscogn but I do wonder if he couldn’t have been taken down by say an alliance of Griffith and Casca, for example. In any case, sure it would have taken longer and resulted in more casualties probably, but in the end... what really ended the war was Doldrey, and Doldrey was won by Griffith’s manipulation of Gennon’s obsession with him more than anything else.

This is important to remember because so many people seem to think that Griffith only saw Guts as a tool and was angry because he lost his best soldier, but that’s kind of ridiculous on multiple levels, not all of which I’m going into here, but for now I will say: the Hawks were already the scourge of the battlefield before he arrived, and by the time Guts left most of the fighting was over anyway so why would Griffith need a soldier that badly?

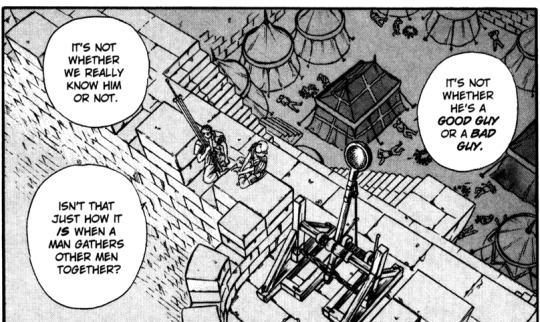

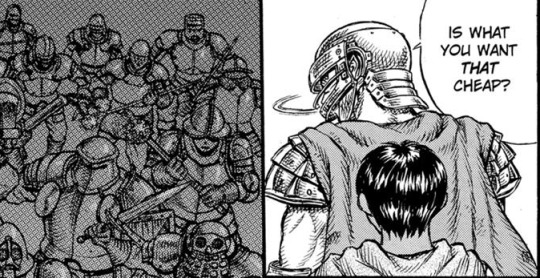

What actually makes the Hawks undefeated is, obviously, Griffith. It’s pointed out that his strategies are absurdly effective, but also here you can discern that from the fact that they have become so successful at, by the Guts’ estimation as a veteran of multiple merc bands, an extremely young age.

5. There aren’t really any characters like Griffith that I can think of - kind of like there aren’t any characters like Guts that I can think of, unless you abstract them to “broody badass with big sword” and “charismatic bishie villain with big plans.” What I mean is they both have a lot more depth and nuance than most characters of their “type.” That said they do have a type, and I notice that a lot of the characters in the Griffith... sphere, I guess, are characterized as people who are made lonely by their own superiority - they stand on the top of a hill no one else can climb and so they are always alone. In some cases this leads to their downfall, e.g. that’s what took down Aizen, when for an instant he wished to be a normal Shinigami so that he wouldn’t be apart any longer.

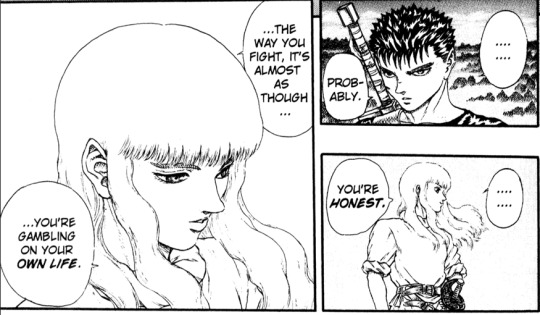

I’m going on about this because I was thinking about what it is that Griffith likes so much about Guts this early on, and it brings me back to that issue he has of isolation. His attraction to Guts comes from Guts’ competence, sure, but it also comes from his fiery determination, his willingness to face poor odds, and his ability to emerge from those odds intact. For Griffith, a person fighting impossible odds to achieve his goals, who gambles his own life and the lives of everyone under his command on the regular, there is a commonality there. Sure they don’t have the same goals, but they have the same grit, the same tendency to play the odds, and turn them in their own favor regardless of how long they may seem.

Also Griffith’s entire life is gambling his life and fighting to survive, and I don’t just mean in the literal battles - he has that same storm inside himself, as well. And this is something that obviously doesn’t become clear until much later... but I do think the recognition of a peer but also a kindred spirit who is struggling externally and internally was appealing to him.... even though we won’t find out that he IS struggling internally until the cave flashback.

As is pointed out by Casca (not to mention by... the plot?) in the end Guts and Griffith are... I guess I’d put it, they’re on the same wavelength even though they occupy different spaces on the wavelength. And there’s a lot of commonality there, if you look beneath their disparate presentations... staring with their mutual fear and dislike of being truly “seen,” which is the basis of Guts’ hostile reaction to Griffith’s spot on analysis of him.

As I recall, the actual line is “make me your soldier or fuck me in the ass.”

I mean hey, he said it not me.

Anyway going back to Griffith liking Guts because he sort of understands and sees their kindred spirits so to speak, here’s another one:

The extent to which Griffith is willing to do in order to win makes this pretty notable.

Also this is the most homoerotic sword fight in the history of anything.

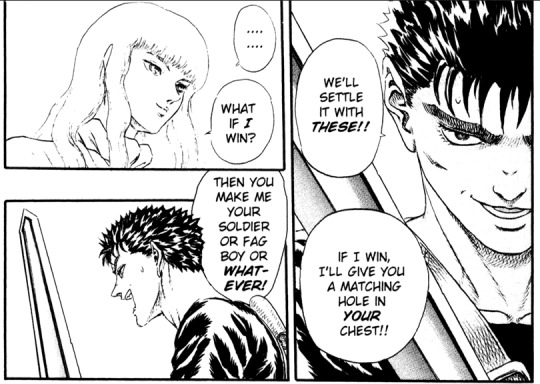

And putting aside the obvious innuendo coming off of Griffith in this whole scene, this moment is kind of... look, Guts can’t touch men, you know? And it’s not like Miura forgot about that - the advancement of his ability to have physical contact with men is a highlighted in the near future. So this always struck me as quite interesting - he doesn’t have any negative reaction at all, no panic, no rage. Obviously one can say it’s because he’s shocked that he lost or generally dazed by events, but Guts really never has a negative reaction to Griffith’s touch.

That makes their reactions to one another... mutually unusual, which s evident from the beginning of their acquaintance all the way to the present.

6. Corkus is a big issue. I wrote a whole meta about him at one point, but the general point of it was that he resents Guts for being so... well, Griffith-caliber, because (as we find out later) Griffith just ran like a hot knife through Corkus’s own band of thieves years ago and ate his dream whole. As a result, Corkus’s ego is dependent on believing that Griffith is uniquely special, because if he isnt then what is Corkus?

7. What’s really interesting to me, though, is that... despite being drafted by force, Guts does stay. Even when he overheards Corkus’ crew plotting to murder him and Casca tells him to go die in battle, he stays. And it’s not like he feels safe there - he definitely doesn’t, as evidenced by his choice to sleep sitting up with his sword. So why?

I’m going to say it’s uh, Griffith obviously - he’s interested in Griffith as a person but I think most importantly he’s held in place by his desire to be desired... such that even when it isn’t by choice, he can’t help but linger around when he feels wanted.

Also he’s injured.

But I think the thing that really nails it down is his first mission with the Hawks.

It would be remiss not to mention that he’s already taking in how impressive Griffith is - the faith the Hawks have in him, the way his plans take into account every possible thing, etc.

But I think more than that, he’s held in place by the fact that, Griffith gives him a pivotal role right out of the gate - one that shows respect for his capabilities, and trust that he will keep to his word. And that’s what Guts really needs, isn’t it? To feel wanted, respected, valued and trusted. There’s no way he can let that go, even if he doesnt fully understand that’s what he needs. It’s still everything he’s ever looked for. And then Griffith goes and does a crazy thing like come back and save his life and... what’s he supposed to do at that point?

And Guts knows It’s weird behavior for a commander. Look at that giant “........” not to mention he does it again at the fountain but anyway.

8. Anyway next up: some interesting forshadowing on Griffith’s relationship with the aristocracy, which is willing to use him and yet finds his extreme competence dreadful and threatening in a commoner. This obviously comes up a lot. But I think it’s worth remembering that we’re establishing here that just his abilities alone, his brilliance and the devotion he inspires in his people, is already considered terrible and disturbing.

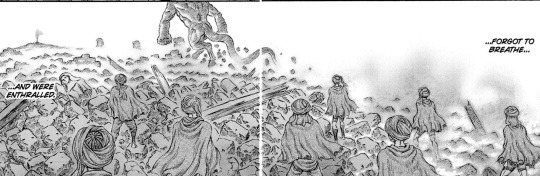

In fact, this whole page is really setting the stage as far as Griffith’s effect on people, their perception of him, etc. To the aristocracy he is a threat, and to his men he is an almost godlike figure - the way they talk about him sometimes... it’s worth remembering because these are things Griffith is sitting there hearing, you know? Understanding the weight of their vision of him, the pressure it creates and his need to live up to that is absolutely essential to understanding Griffith as a person and I do think... their love can be a burden at times. Because it isn’t a love for Griffith the man, it’s a love for Griffith the invulnerable hero, the inviolable symbol - undefeated and undefeatable. And that’s what he needs to be, to them. And it’s a lot.

9. I love the little detail of Guts’ reaction to all that closeness. And its again worth noting that until this point he’s still struggling with touch - in the previous pages he elbowed Pippin in the face for touching him. But...

As the celebration progresses and the Hawks share their trust with him, he visibly relaxes - another signifier that this is what he really needs and wants in his life - trust, belonging, and comrades. Even if he hasn’t admitted that to himself.

Even so, he’s obviously afraid to let it in.

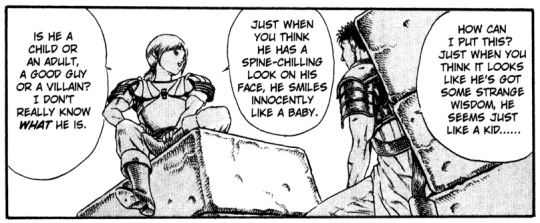

10. I reblogged (retumbled? lolz) a comment yesterday about how you have to let go of your good/evil indoctrination to have a chance of understanding Griffith and I really do believe that. Because he’s a complicated person and boiling him down to a monstrous sociopath is honestly insulting to Miura’s work, but it’s not like he’s a nice person either. At least not wholly. And by saying “I legit have no idea what hes actually like, he is impossible to understand” Judeau comes about as close as anyone inworld does to summing up his character accurately.

It’s just interesting to me that the story really lays out in words that he’s not easily pigeonholed into any specific category and yet people just love shoving him in a box, it’s like a compulsion or something, I don’t know.

11. Judeau says later that he was wrong, but he really wasn’t, was he? It’s more that Guts got his head screwed on backwards after Promrose.

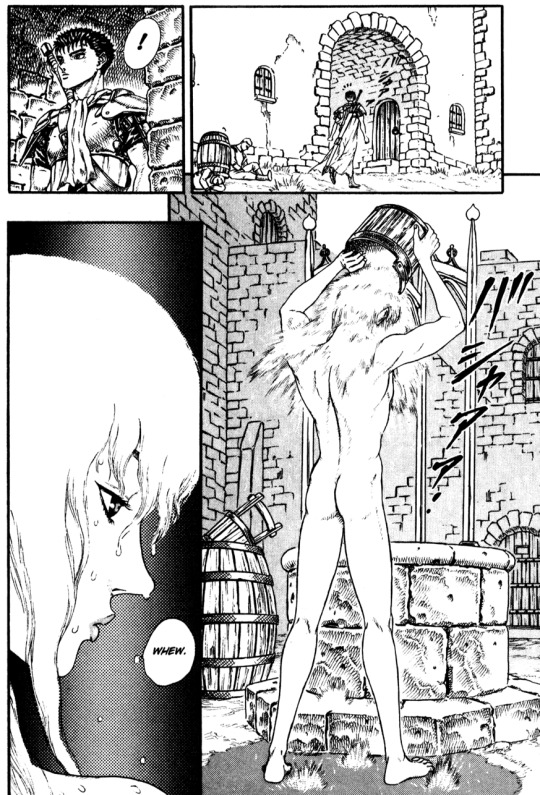

12. So the naked waterfight.

First of all, he really just said “wanna get naked and wet with me?”

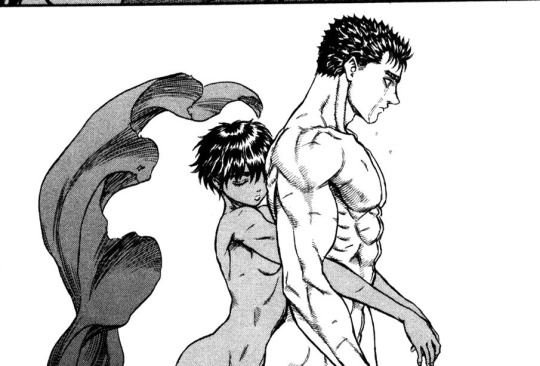

Anyway narratively the fight I think serves a few purposes - Griffith’s nudity foreshadows his vulnerability and lack of defenses with Guts.

But it also shows us why Griffith ends up defenseless to him. Guts is exactly what he thought Guts would be - a peer. Someone who treats him like a person instead of a god. Someone who is willing to throw things at him and get cheeky with him and generally just... see him as he is. We even get equivalent splash sequences - in short they are peers in age, similar in ability, and made of similar stuff.

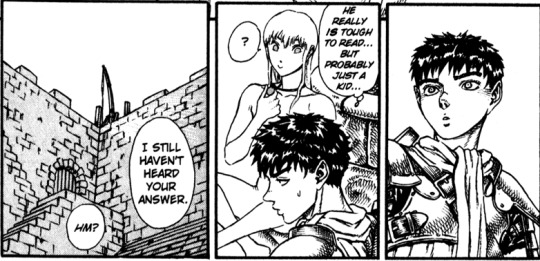

And when faced with Griffith’s sometimes inscrutable personality, Guts is just like, "Yeah hes definitely weird, but tbh probably just a kid.”

Obviously, it also serves as a reminder of who this is and where it’s going with the first appearance of Griffith’s Crimson Behelit.

The doomsday clock hanging over them.

And then the groundwork for Griffith’s irrationality where Guts is concerned.

You know... I personally think Guts was as much into Griffith as Griffith was into Guts (well I have a bunch of thoughts on the specifics of Guts’ feelings about Griffith but that’s another story for another day). And I have always argued that, and always stood by it. The first time I read this series, when I knew nothing at all about the fandom or the popular perspectives on the characters, I was honestly just like... these two are absolutely in love, and this is the saddest freaking near miss in the history of the world. I was kind of shocked when I looked up fan discussions and found that the most popular views were things like “Griffith is a psychopath” and “Guts hates him so much omg.” Checking out Japanese fandom was like a sanity saver for me because they do have a different perspective and I suspect that the chasm in the reactions have to do with cultural tics and dealbreakers, e.g. Japan isn’t as touchy about some subjects in fiction as say America is, and of course we’re talking individualist vs a collectivist cultures as well which .means there’s a whole different set of... expectations and understandings about what kind of behavior is acceptable or not, and what kind of behavior is sympathetic or not.

But anyway, that’s a bit of a ramble getting to this: Although I’ve personally always argued that Guts was as attracted to Griffith as the other way around, I do understand the disagreement on that. Like I can completely see how people see his feelings differently than I do.

But I will never in my whole entire life ever understand how anyone on this planet can read this series and not think Griffith is in love with Guts. I literally can’t think of any other explanation for his behavior, dialogue, thought narration, etc. where Guts is concerned (not to mention CASCA’S actions and comments about/to Guts) and every other potential explanation, including the ones people love to push (eg. guts was his best weapon!!!) is explicitly ruled out by the text in black and white. Even here, where Griffith gives that explanation himself, Guts clearly thinks he’s bullshitting - and he calls him on it later, too.

It is beyond me.

Anyway,

13. Then comes Griffith’s big “Ima be a King my guy” line, and Guts looks like he’s seen the Messiah or something (which, I mean, technically...) but what I really want to note is...

Just like that, Griffith has thrown Guts’ world into a tailspin. It’s not the last time that happens, really - it happens again after Zodd and again when he overhears the stupid Promrose speech. Griffith’s words hit Guts like a hammer to the head over and over again, and in this he gets swept up in what Judeau talked about earlier:

Griffith’s charisma, his conviction, his drive. The thing that pulls the Hawks together from all their different backgrounds and gives them something to believe in and aim for.

But of course, with Guts, it is a little different, too.

But for now I’m going to shut up because the three year timeskip is the perfect time to go do something else.

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Gold Rush (1925); AFI #58

The next film that we had for review is a classic comedy from the 1920s, The Gold Rush (1925). This movie is often considered to be Charlie Chaplin’s best work and what he considered to be the film he most wanted to be remembered for. I watched the original cut that is a little bit longer than later versions and has a simple piano score. The movie was re-released in 1942 with an orchestral score that was nominated for Best Song and Best Score at that year’s Academy Awards. We will go over the plot and it probably doesn’t need a spoiler warning since the movie is a century old and there have been so many parts of this film that other movies and TV shows have paid homage too...but it is better to be safe than sorry:

SPOILER WARNING!!! PLOT POINTS FOR A 95 YEAR OLD MOVIE COMING UP!!! THIS WARNING IS SLIGHTLY SARCASTIC BUT I DON’T WANT MAIL ABOUT IT!!!

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The movie begins with establishing shots of men hiking through the snow to represent the Alaskan gold rush. Vast uninhabitable plains are suddenly full of people trying to find gold. Amongst this group is Big Jim, a prospector that found a gold deposit on his claim when a blizzard strikes. Another is a little tramp, who is credited as The Lone Prospector (Charlie Chaplin), a simple man who is just wandering and trying to find his fortune. Both of these men run into a sudden blizzard and are driven into the cabin of Black Larsen, a man who is a wanted criminal. Larsen tries to throw them out, but he is overpowered and the three settle in for the storm.

The storm goes on so long that one of the three needs to leave to find food. They pick cards and Larsen loses, so he is sent out to go find food. Larsen runs into and kills two policemen then finds the claim of Big Jim. Larsen decides to wait out the storm then flee with the gold before Big Jim can come back. Hopefully he will die of starvation in the cabin.

Speaking of starvation, the tramp and Big Jim have run out of food and the big man is starting to hallucinate that the little tramp is a chicken. The big man chases the little tramp around the cabin going in and out of a ravenous haze with a shotgun. A bear breaks in while the two are fighting and the tramp is able to shoot it so the two men now have food. This sounds like a horror movie or something out of The Revenant, but it is done in a very comical way.

The two leave the cabin once the storm subsides to find their fortunes. Big Jim goes to his claim and runs into Larsen, who knocks out Big Jim with a shovel. Larsen attempts to leave with some gold but is killed in a sudden avalanche. Big Jim comes to eventually, but he stumbles away until he gets to a town and can’t remember how he got there. He also can’t remember how to get to his gold, so he decides he must find the little tramp and the cabin which will jog his memory about the location of his claim.

The tramp wandered until he found a boom town that apparently was built overnight. He enters a happening dance hall and sees a beautiful girl who is bored and trying to avoid the advances of the local ladies man. Her name is Georgia and she tells Jack, the ladies man, that she would rather dance with the most deplorable looking tramp and proceeds to grab the lone prospector and dances with him. The little guy is smitten and, after a few chance encounters, invites Georgia and her group of friends to have New Year’s Eve dinner with him. She accepts as a joke and completely forgets. The tramp did not forget and scrounges up enough money for a nice meal and waits for the girls to celebrate. He waits so long that he falls asleep and dreams of a successful dinner party in which he entertains the girls with a puppet dance involving forks and bread rolls.

He wakes up and walks the streets feeling depressed and lonely. Georgia, however, does remember the invitation and goes to the house at which the tramp is staying. She finds a set table with a meal and presents and suddenly feels bad for treating the tramp so badly. She mentions to her friends and Jack that she wants to find the tramp, which angers Jack and inspires him to write a note that says she wants to talk. The tramp is given the note when he returns to the dance hall, but is intercepted by Big Jim, who promises to make the tramp into a millionaire if he can help him find his claim. The tramp tells a confused Georgia that he got the note and will return to take her out of this life.

Big Jim and the prospector get to the cabin, but there is another blizzard (it’s the Klondike, it happens a lot) and they are not able to go out for the gold right away. During the night, the cabin is blown to the edge of a cliff and is teetering on the edge. There is some humor about not tipping the house until the two are able to successfully escape and they happen to have ended up right next to the claim.

A year passes according to a dialogue card, but the little tramp was not able to find Georgia. He and Big Jim take a boat back to the continental states. The press is there and a member wants to get a picture of the tramp in his old mining outfit. He puts on his old clothes and has a mishap while posing for a picture and falls down some stairs right next to Georgia. She is taking the boat and assumes he is a stowaway and tries to save him from the ship’s crew. She is made aware that he is now a millionaire and she joins him for a picture in which the two kiss.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

While writing the synopsis from my notes and comparing it to other online summaries, I realize that there are parts of this film that sound like a horror film. Two men are fighting for survival out on the Klondike during a storm with nothing to eat and start considering cannibalism like something from the Donner Party. In the midst of a fight over a shotgun in which a very large man is attempting to kill a much smaller man, a bear (and this is a real trained bear in some of the scenes) breaks into the cabin and the two must now kill it. I think I have seen this movie and it wasn’t a comedy. This film has murder, assault, bear attacks, sexual harassment, and dog kicking. I am not sure it could be made today and I am sure that many aspects would be cut. But this is why these films are so interesting, it was a creation from a previous time and it reveals what was socially acceptable in a different era. I find it fascinating.

As old as this film is, some of the more famous scenes have been copied in film and TV more recently. The quick little dance with the dinner roles has been copied by Curly from The Three Stooges in 1935, Robert Downy Jr. in 1992, Johnny Depp in 1993, Grandpa Simpson in 1994, and Amy Adams in 2011. A Walter Lantz character named Chili Willy the Penguin had a couple of adventures that very closely imitated the “starving in the cabin” scenes with Chaplin and Big Jim. I have not seen the films, but IMDB and Wikipedia claim that the hanging cabin scene has been used in a couple of Bollywood movies - Michael Madana Kama Rajan (1990) and Welcome (2007).

There are two more films on the AFI list starring Charlie Chaplin, so I don’t want to go too in depth into his life at this point. I do want to mention that he cofounded United Artists distribution with D.W. Griffith, Mary Pickford, and Douglas Fairbanks. This allowed him to have complete control over all aspects of his films, so everything you see is 100% his vision. He wrote, directed, produced, edited, scored, and starred in almost all of his films. We don’t see that much these days because there is some studio meddling in almost every film, so it is refreshing to see a creative work from a single source.

So does this film deserve to be on the AFI 100? Beyond a shadow of a doubt. This is a very simple movie that comes from the very infancy of the media, yet I consider it to be better than most current films. It has a good story despite having no dialogue and set pieces that are still copied a century later. This is truly the work of a genius. Would I recommend it? I am upset if you haven’t seen it yet. It is only 75 minutes, it is very entertaining, and it is an easy to digest piece of American culture. Go watch it right now. If you have already seen it, go watch it again with somebody who hasn’t seen it. This is the kind of film that the AFI Top 100 movies was created around, basically a reason to go back and review quality film from the past. Well worth the time and I can’t recommend it enough. Please give it a view.

#charlie chaplin#the gold rush#1920s#black and white#silent film#film critique#afi top 100 movies#movie spoilers#introvert#introverts#movie review

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Movies watched in 2017 (11-20)

Continuing my 2017 film journal. So far, I’ve continued to find some real gems!

Three Came Home (dir. Jean Negulesco, 1950)

Documenting the true story of the American Agnes Newton Smith, a writer interred with her son in a Japanese POW camp during WWII, Three Came Home is a decent film, with solid performances and a few standout scenes. It is a movie which the censorship codes held it back from being a more powerful work; you always get the sense that the filmmakers wanted to show more of the graphic and harrowing side of Smith’s ordeal, which included torture and almost being raped. nevertheless, the filmmakers go as far as they could at the time, even allowing star Claudette Colbert to get in front of the camera sans make-up. Everyone is coated in sweat and grime. Sessue Hayakawa is there too as the sympathetic Colonel Suga. He gets one strong scene toward the end of the movie, where he evokes immense grief and guilt without words, a reminder of his power as a performer and his heyday as one of the best starring actors in Hollywood during the 1910s. (7/10)

BBC Sunday-Night Theatre: Nineteen Eighty-Four (1954)

Peter Cushing as Winston Smith—who can resist that? Once again, this man proves he is one of the most underrated actors to have ever stood before a camera. Despite the obvious low budget, this is a great adaptation of Orwell’s novel, much superior to the American feature adaptation made a few years after. In fact, I would say the low budget and cramped sets add to the desolate, gloomy, claustrophobic atmosphere of Oceania’s dystopian world. Everything is dingy and depressing. The ending retains the bleak outlook of Orwell’s novel and Cushing’s great depiction of brokenness only makes it all the creepier. I also want to highlight the great work Yvonne Mitchell does as Julia; she’s pretty and sensual, but not at all a glamorous starlet like the American ‘50s adaptation. Overall, a great version. If you love the book and care about your adaptations being accurate, then you’ll probably enjoy this picture. (9/10)

Reaching for the Moon (dir. Edmund Goulding, 1930)

I wouldn’t really call this movie good and the only folks I can recommend it to are old movie buffs like me, but if you are into pre-code movies, art deco, Bebe Daniels, and/or Douglas Fairbanks Sr., then Reaching for the Moon is worth watching once. The plot is frivolous and forgettable, the pace is slow even for a 70 minute picture, and poor Fairbanks is kind of wasted. He spends some time doing his usual acrobatic thing, but it always feels slapped on and not organic to the scenes. Apparently the movie was originally supposed to be a musical, but the studio cut most of the songs at the last minute since audiences were getting tired of musicals in mid-1930. To be honest, I wish they had kept them in, because the musical numbers are the most energetic and engaging parts of the film. I especially enjoyed Bing Crosby and Bebe Daniels in the jazzy, very Depression-era number “When the Folks High Up Do the Mean Low Down.” Easily, that scene and the art direction are the best assets the movie has to offer; William Cameron Menzies does lovely work on the art deco sets, which are like a dream of 1920s glamor. (6/10)

The Eternal Mother (dir. DW Griffith, 1912)

Like the Griffith short I watched in the last batch, not an essential among his early work. Mabel Normand and Blanche Sweet are wasted as a wanton woman and a virtuous wife. The plot is incredibly thin and silly: a man leaves his good wife for a tart; the tart bears his child and dies on cue. The wife is so good that she takes in the child and the husband spends his years alone until he and the wife reunite as elderly folks. Not much of interest on the technical or story scale. (4/10)

Three Outlaw Samurai (dir. Hideo Gosha, 1964)

I got interested in this one after figuring out Rian Johnson used it as an influence on the next Star Wars movie. I’m guessing most of the influence came from the way Gosha shoots the swordplay, which is very kinetic and rough, but there may be some of the film’s cynical treatment of justice and honor in the new Star Wars too… maybe, since Star Wars is rarely cynical when it comes to good and evil, but we shall see. Regardless, it is a good film, an essential if you like chambara. (8/10)

The Dentist (dir. Leslie Pearce, 1932)

To say WC Fields is weird is an understatement. I would not say I am a fan, but I do adore his surreal and deadpan Yukon parody The Fatal Glass of Beer and generally like The Bank Dick. The Dentist isn’t as impressive as either of those, but it has plenty of good, misanthropic laughs as well as some very risqué humor for 1932 (but then again, this is from the pre-code era). (7/10)

The Fall of the House of Usher (dir. JS Watson Jr. and Melville Webber, 1928)

While not as good as the later Watson and Webber offering, Lot in Sodom, their surreal adaptation of Edgar Allan Poe’s short story is still dazzling. It actually feels quite modern. It is a modern dress adaptation and conjures more of the dreadful, claustrophobic spirit of the original story rather than sticking closely to the letter. It also has a lot more obvious Caligari influence than the later Lot in Sodom. (9/10)

Fire Over England (dir. William K. Howard, 1937)

I’ve been reading a lot about the Tudors lately and Elizabeth is my favorite of the bunch. After watching the pretty poor Cate Blanchett movie, I went sixty years back to this 1937 adventure film produced by Alexander Korda. While not focusing exclusively on Elizabeth, it does tell a rousing yarn about an English spy (playing by a young and totally adorable Laurence Olivier) out to do business in Philip II’s court before the legendary English victory over the Spanish Armada in the 1580s. It’s a fun swashbuckler complete with broad characters, a hiss-worthy villain, swordplay, and daring escapes, also of historical interest since the conflict between England and Spain is meant to reflect the then-contemporary conflict between most of Europe and the Nazi Germany. Flora Robson is a great screen Elizabeth, commanding and charismatic while also sporting a fierce temper. And though given little to do, Vivien Leigh is ravishing, and even in this early film, she and Olivier are wonderful together. (8/10)

Ruka [The Hand] (dir. Jiri Trnka, 1965)

I was turned onto the work of Czech animator Jiri Trnka by the Brows Held High episode on his 1959 feature adaptation of Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream. That film is a charming fantasy and heartfelt look at the power of art; however, Trnka’s most famous film, the short “Ruka,” is much darker and proved to be his swan song before he passed away in 1969. It is a political satire about the suppression of artistic expression in totalitarian regimes. It is both darkly hilarious and incredibly bleak. Considering Trnka’s work is usually characterized as nostalgic and whimsical, his final film is strikes a sad, but still powerful chord and remains incredibly relevant even today. (10/10)

Big Deal on Madonna Street (dir. Mario Monicelli, 1958)

So freaking funny! I watched this one because Martin Scorsese recommended it as one of his choices for essential foreign cinema. Though Big Deal is a parody of 1950s heist pictures such as The Asphalt Jungle and Rififi, it is nothing like the pathetic cinematic parodies we get now, like Meet the Spartans or Fifty Shades of Black. Like Airplane or Blazing Saddles, it still understands that it needs to work as an original story with characters we enjoy watching and good gags that don’t really on references to popular culture alone. Big Deal is also interesting in its presentation of everyday life and urban poverty, seeing as our heroes are a mix of sad sack, small time criminals and lower class working folk; in many ways, it feels like a comic romp set in the same universe as The Bicycle Thieves or Umberto D. (9/10)

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

My Big Gay Berserk Analysis 3

Casca’s Role

Part One Part Two

In this post I’m going to discuss how Casca’s narrative role as a love interest overlaps with her narrative role as a substitute for Griffith, how those roles ultimately serve the main story that is the love/hate relationship between Guts and Griffith, and how Miura utilizes her as an emotional/sexual conduit between the two while also conveniently no-homoing them. Plus some additional straightforward stuff on Guts and his crush on Griffith here and there.

Advance warning: this is long. Looooooong. Also be warned that I do touch on the hound and the Eclipse, but only in one section of this post.

I also want to make clear upfront that I love Casca but I dislike the Guts/Casca romance subplot, for many reasons including my general dislike of most het, Guts’ awful treatment of her, and the sense I get that she’s been inserted as a buffer between Guts and Griffith, but mostly because I think the romance was added almost entirely to set up the destruction of Casca as a character for the sake of Guts’ manpain.

So yeah going in you should be aware that this is Guts/Casca negative. I don’t consider their romantic feelings for each other a valuable part of Berserk, and I spend a lot of time calling the legitimacy of those feelings into question. If that sounds like it’ll piss you off but you still want more Guts/Griffith content, you can totally just skip to part 4 without missing any necessary information for that part.

Ok that said, let’s get into it.

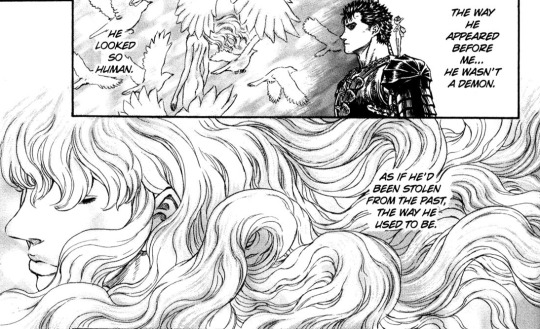

We’ll go back to the Golden Age eventually but I’m going to jump ahead first and start at chapter 130, during Guts’ night of self-reflection after he returns to Godo’s cave and finds Casca missing.

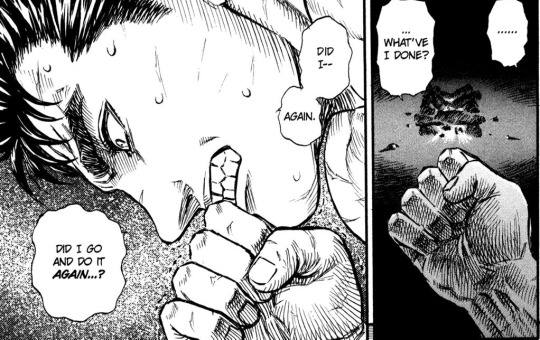

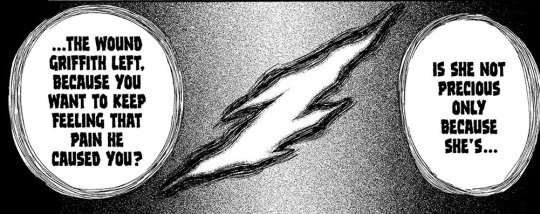

Guts is basically having an internal debate about whether or not his revenge rampage was worth abandoning Casca. He eventually emphatically concludes that it was in fact not worth it and he fucked right up when he draws this connection:

Again again again again. I’m starting here because it’s one of the most clear and straightforward examples of Guts viewing Casca as a replacement for Griffith. The connection is drawn explicitly - he considers abandoning Casca to be the equivalent of abandoning Griffith and drawing that parallel is what motivates him to save her.

But despite wanting to start atoning for past mistakes, he still intends to abandon her in a cave again after he gets her back.

“Actually, I only half mean it.”

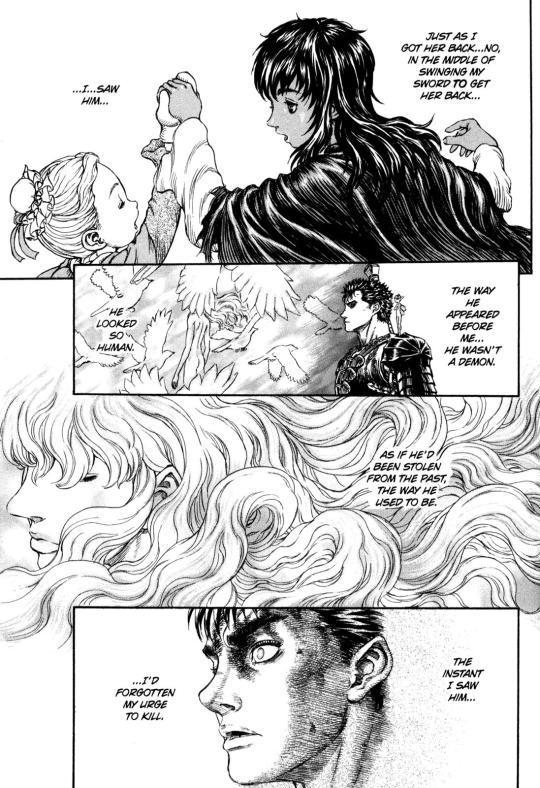

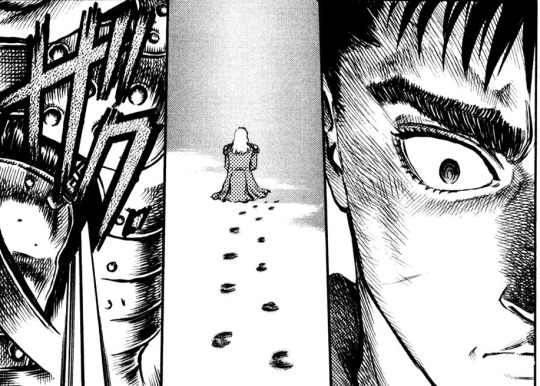

Cue this #iconic page:

Now I talk about this page all the damn time because of how off the charts gay it is, but more importantly right now is that it draws a strong contrast between Casca and Griffith. It begins with “Just as I got her back... no, in the middle of swinging my sword to get her back...”

In the middle of getting her back... he... saw him. By framing Griffith’s appearance as an interruption that rips his attention away from rescuing Casca, Guts expresses the feeling that he’s torn between them. And of course he is, we see this throughout the rest of the manga, in his internal struggle not to toss Casca aside (or worse) and run after Griffith to, “give him... a heap of raw iron.”

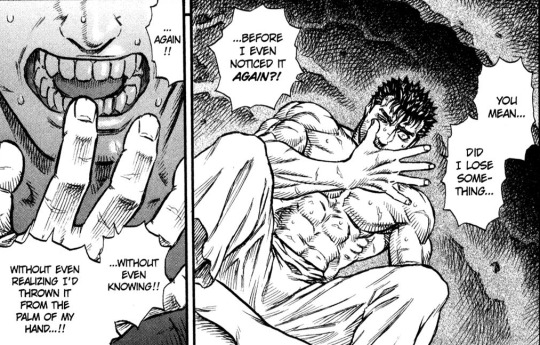

We also see this inner conflict during NeoGriffith’s appearance when this happens:

But as of right now, Griffith has won the fight for Guts’ attention.

Guts’ half truth, as far as I can tell, is that he’s going to help make Godo’s cave a little homier and then take off again after Griffith.

As we saw in chapter 130 he decided to dedicate himself to getting Casca back, and we can assume that he fully intended to give up his revenge quest at that point. Godo tore him a new one over abandoning her to fight monsters, Guts realized he’s been being a dick, and he’s figured that maybe staying and helping take care of Casca is a better way of dealing with his issues than going back on a rampage, especially since last time he saw Femto he couldn’t even come close to touching him.

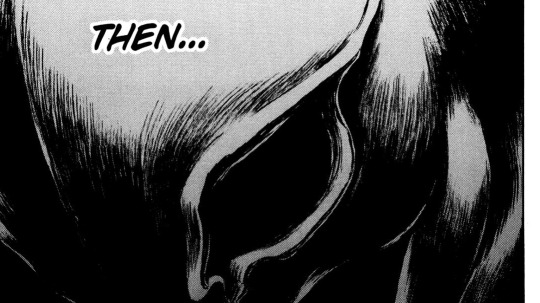

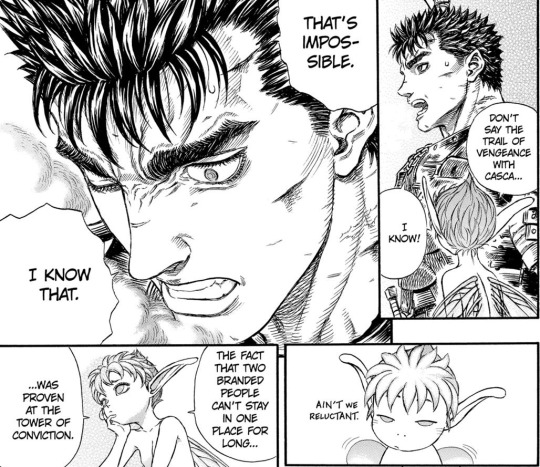

But then Skull Knight tells him the Godhand are going to be around, there’s going to be another version of the Eclipse, and we see Guts conflicted again:

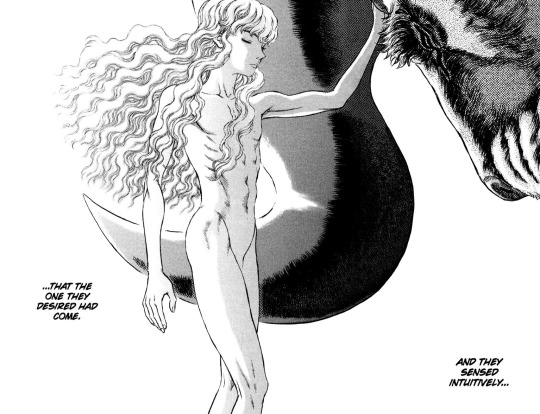

Anyway Isidro ultimately saves Casca, she and Guts are reunited, and Griffith appears. Maybe Guts’ original plan was to stay with Casca and forget revenge, but now Griffith is reachable, he’s on the same plane of existence, and to top it all off, he’s hot again!

And no I’m not joking, I absolutely think that Guts’ sexual attraction to Griffith is, for the first time since Promrose Hall, being clearly visually conveyed again. I already posted that iconic page in which Guts pictures Griffith’s ass and gets distracted from revenge, but there’s more where that came from.

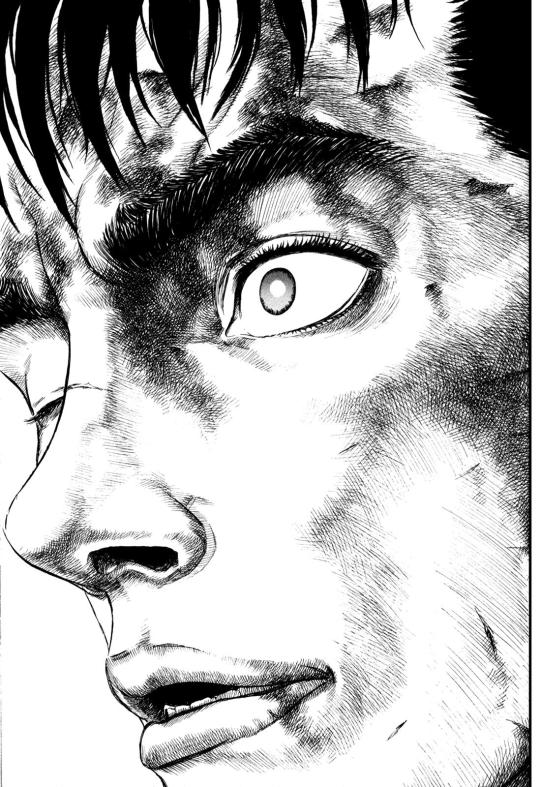

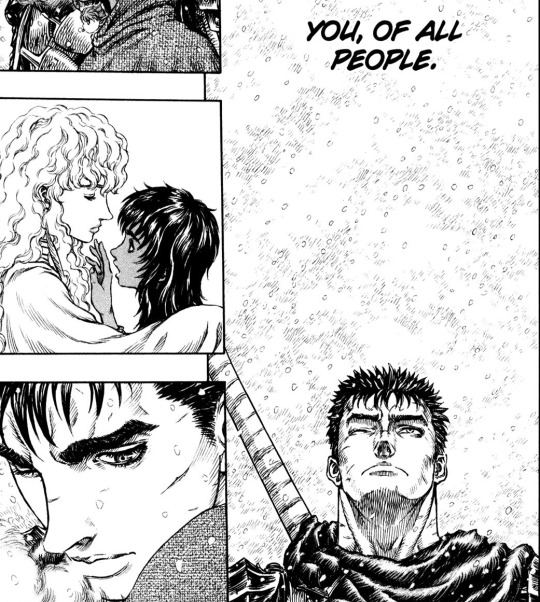

Griffith's sexiness is genuinely an important plot and thematic point lol, but it’s Guts eyes we’re shown that through, and holy shit does his gaze get a lot of attention in this scene. And why? Because Griffith’s reachable again. When he’s monstrous and demonic he’s out of reach on a whole nother plane of existence and shown as distant and untouchable:

When he’s incarnated as a physical being again he’s said to be “the desired,” he’s so beautiful no one can shut up about it, and imo Guts’ temptation to pursue him now that he’s “where [his] sword can reach,” is tied to the sexual temptation on display here.

Basically, while he’s certainly not intending to pursue Griffith so he can literally fuck him, there are blatant sexual undertones to his desire for revenge that ramp up hard and fast real soon, and they start with Griffith’s sexy as fuck rebirth.

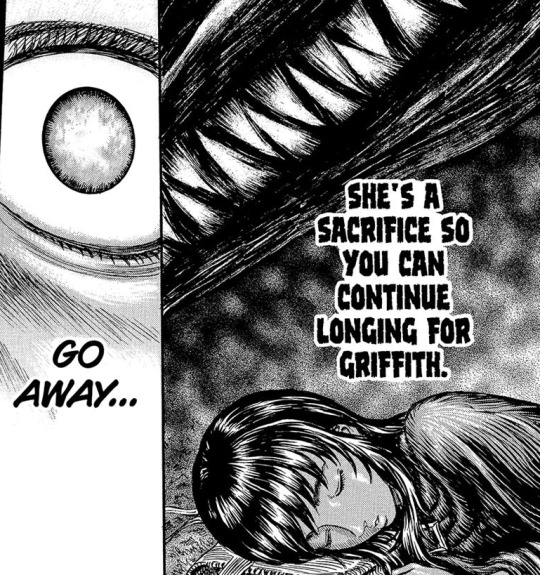

And to elaborate on how the depiction of Griffith is a huge contrast here to the depiction of Casca:

Casca is shown at her least sexualized. She’s wrapped in a shapeless cloak and mirroring Erika, depicted as utterly childlike.

And this is Griffith:

Griffith is the temptation, he’s the one Guts wants to pursue, and Casca is the responsibility, and this is shown loud and clear through Griffith’s intense desirability and Guts’ enthrallment at the sight of him vs Casca’s desexualized childishness.

As for the Hill of Swords reunion

“More like someone out of a fairytale.”

Not overly relevant but it’s a fun detail that “He was so pretty” is on Guts’ face while “someone out of a fairytale” is on Griffith’s image.

That sound - like Griffith’s apparent acknowledgement, at long last, is a physical blow. Love it.

But of course then Griffith’s like, I came to see you to test my capacity for emotion, and it looks like this whole emotionless demon thing was a success. And this is Guts’ reaction - not rage, or at least, not solely rage, but so much hurt too:

Look at those sad eyebrows man. This scene thoroughly shows us how emotionally conflicted and confused Guts is. He’s angry, he’s hurt, he’s full of longing both for revenge and for “the way he he used to be,” and after everything he still wants acknowledgement, he still wants Griffith to look at him.

“I’ll not betray my dream. That is all.”

And it’s now that Guts finally attacks. So far he’s let Rickert hold him back, then shoved him away only to scream “you don’t feel anything?!” instead of rushing him. But when NeoGriff tells Guts in no uncertain terms that his dream is not only more important, but his sole priority, Guts snaps.

I do think it’s really easy to read this scene as Guts looking for a hint that Griffith still cares about him, along with the hope that he feels regret for what he’s done. Guts had a lot of misconceptions about Griffith’s feelings, but by the time of the Eclipse he’d realized that Griffith loved him - he’d left to seek something (love and respect and affection, friendship and equality) he already had and, in leaving, lost it.

Scroll back up to that first picture I posted, he says it right there: “Did I lose something before I even noticed it again?! Without even realizing I’d thrown it from the palm of my hand!” There’s a small part of him that was still hoping, now that Griffith is un-demonized, that his heart and his love had returned with his human body, that it’s not lost forever. But in declaring that he’s free, NeoGriffith shoots that hope down.

Anyway big fight, cave collapses, Griffith’s heart starts doing shit unbeknownst to Guts, he mysteriously saves Casca and takes off, and Guts

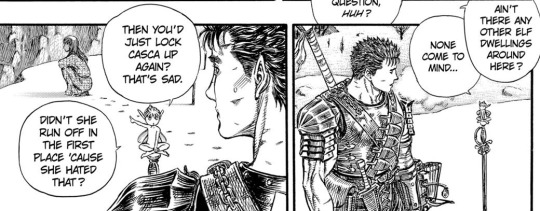

says he won’t abandon Casca again and decides to escort her to Elfhelm, with his dickish reluctance handily pointed out by Decent Person Puck lol.

Now look at this shit:

“Weren’t those Godo’s parting words?” Says Guts to Rickert to convince him to stay with Erika.

“You should have known. This is the man I am.”

Don’t abandon what you can’t replace. He finally learned that lesson when he compared abandoning Casca to abandoning Griffith. He frames his choice to stay with Casca as making up for it. Guts once deserted Griffith, now Griffith has deserted him, so he’s promising not to desert Casca. Given that Guts’ mind is solely on deserting and being deserted by Griffith, as opposed to that time when he left Casca in a cave for two years and she wandered off, “I won’t desert you anymore. This time... I won’t lose you,” is given a double meaning of applying to Casca while also referencing losing Griffith.

But what’s with that interlude up there of Guts remembering Griffith saving Casca? The man Guts “knows” NeoGriffith is, the man who dgaf about anything except his dream, isn’t the man who would randomly decide to save Casca from falling rocks. Guts is shown thinking about that apparent contradiction immediately before “I won’t leave you behind. I won’t... desert you anymore.”

Taken all together, to me this scene comes across as so utterly Griffith centric that it makes Casca feel like an afterthought, conveniently there so Guts can take some form of action in response to his extremely Griffith-centred emotions.

Guts charlie brown walks away because Griffith “deserted” him. Guts draws a comparison between abandoning Griffith and abandoning Casca, and being abandoned by NeoGriffith and refusing to abandon Casca. Guts remembers NeoGriffith saying he knows what kind of man he is right before recalling him saving Casca.

Then he declares he won’t desert her again - and I have to wonder if part of what gives him the willpower to take a break from his revenge quest despite NeoGriffith residing so temptingly in his plane of existence now is the ambiguity of NeoGriffith’s actions here, casting “the kind of man” he is now into doubt and deflating Guts’ rage boner the same way he says seeing NeoGriffith looking “so human... the way he used to be” makes him forget his “urge to kill.” It hardly seems like a stretch given how much of Guts’ decision here is explicitly shown to be about Griffith.

So far, post-Eclipse, Casca’s been treated as a prop for Guts’ internal conflict between revenge and not being a dick - a symbol of his lingering humanity. She exists to be put into peril so Guts can decide to save her and then waver between her and Griffith. She’s the poster girl for failing to pass the sexy lamp test. It’s real depressing, and it’s about to get worse.

Enter Beast of Darkness.

Now we’re at the really bad shit, but also the actual most explicit verbal suggestion of Guts’ sexual attraction to Griffith, so it’s impossible to skip in a post on the topic. Plus there’s no point pretending that Casca isn’t done incredibly dirty by both the narrative and Guts.

It’s important to understand that the Hound is Guts. It’s not an evil malicious spirit trying to manipulate and possess Guts (which I have seen suggested before), it’s simply Guts’ dark emotions given substance. Just on the off chance this statement requires support for you, here’s a post on the subject. This scene is pretty much Guts arguing with his id.

And the way it’s framed with “dreams of him?” “let’s go to him” coming first on the image of an eager, excited puppy, followed by the teeth and “heap of raw iron” feels so deliberate to me. Guts wants violent revenge but it’s a feeling complicated by the fact that he loved Griffith, that he once strove to be his equal, to be considered his friend, and now he strives to kill him.

Like Guts facing Femto in the Black Swordsman arc, like Guts pleading for a shred of regret from NeoGriffith, there’s still an element of Guts wanting Griffith’s acknowledgement here.

More direct comparisons between Casca and Griffith and how Guts feels about them. Who’s more precious, your love interest or your arch nemesis?

And I’m not here to say that Guts doesn’t care for Casca and only cares about Griffith. As this scene shows, he’s torn between them, but he’s chosen Casca now, and he’s trying to get his doubts and his rage and his suppressed attraction to Griffith that’s now coming to the surface, coloured by hate, to shut the fuck up. But these are his own doubts.

“The wound Griffith left, because you want to keep feeling the pain he caused you?” Okay, certainly an eyebrow raising description here but all right, this is about Guts’ motivation to kill Griffith. The Hound is suggesting he values Casca only as fuel for his rage. Which certainly seems like a relevant suggestion after Guts’ “I'd forgotten my urge to kill. And that... can’t be.” His rage needs fuel. So while that’s surely not all there is to his feelings for Casca, the Hound isn’t making shit up. Again, this is essentially Guts internally debating what his true motivations are.

Longing. Hell of a word choice. Granted I can’t double check the translation with others because I’m incapable of tracking down old raws (tho I did a cursory search on skullknight.net to see if anyone had criticized the translation of this scene and didn’t find anything) but this is such a boldly romanticized choice of phrasing that I feel it’s safe to assume the undertones are there in the original Japanese. You don’t accidentally describe someone’s urge to kill a dude as “longing” for him. That’s a blatantly deliberate double entendre.

And on top of that it fits right in with the Hound’s first eager, excited words to Guts in this scene. Again, it’s an illustration that Guts’ vengeful feelings are complex, and intertwined with his original feelings for Griffith.

And then the Hound tells Guts to rape Casca so he can get closer to Griffith and I throw up my hands.

There’s so much innuendo and homoeroticism in the lead up to this (including earlier, w/ Griffith’s sexy rebirth scene and the reunion on the Hill of Swords, ft Guts thinking about Griffith’s ass), and then this scene just doubles down as hard as possible. “Let’s give him... a heap of raw iron,” “because you want to keep feeling the pain he caused you,” “she’s a sacrifice so you can continue longing for Griffith,” “you’ll get closer and closer to Griffith.” The innuendo in this scene makes it one of the most homoerotic scenes in the manga.

Like, tl;dr Guts’ vengeful pursuit of Griffith is tied so thoroughly to sex in this nightmare that tbh I have a hard time calling this subtext.

And while it is absolutely homophobic for one of the gayest scenes in the manga to basically tie Guts’ desire for Griffith to his desire for revenge and a suggestion to rape and kill Casca, it’s also worth noting that this isn’t exactly Guts’ desire for revenge being given a dark sexual element.

This is the Beast of Darkness using Guts’ pre-existing desire for Griffith to try to tempt him into sticking a sword in him. Still fucked up, obviously, but it’s at least deeper and more interesting than the alternative.

The earlier parallels I described, Guts comparing leaving Griffith and leaving Casca, etc, draw an emotional connection between Guts and Griffith through Casca as, essentially, a bridge. Guts is assuaging his desire to go back and fix his mistakes by replacing Griffith with Casca and refusing to leave her. Casca has become an outlet for Guts’ feelings about missed opportunities with Griffith.

This chapter draws a very direct sexual connection between Guts and Griffith through Casca as a bridge. By raping the woman Femto raped, Guts can get closer to him.

And it is, of course, not the first time the manga has done this. Femto’s unwavering stare into Guts’ eye(s) during the Eclipse rape scene isn’t subtle, though I don’t intend to go into it in detail as this is about Guts’ sexual desire, not Griffith/Femto’s. I feel like the stare (the fucking stare omg) speaks for itself.

I mention this only to make the point that there’s an established precedent for Casca bearing the brunt of these dudes’ repressed feelings for each other, whether it’s genuinely intended to be interpreted as repressed sexual desire or whether it’s meant to be platonic spite/longing to get closer and closer to Griffith no homo. It’s not fair, it’s bad writing on several levels, it’s both misogynist and homophobic, but there you go.

Ultimately my main takeaway here is that Berserk would be about 500x less fucked up and offensive if Guts and Griffith just cut out the middlewoman and fucked each other.

Okay, that’s enough of that. Let’s go back to the Golden Age.

So far I’ve done my best to show that, post-Eclipse, Guts’ relationship with Casca largely revolves around his feelings for Griffith, both regretful and vengeful, and the fucked-up sexual component of his relationship with her also relates to the sexual component of his relationship with Griffith. So what about pre-Eclipse? Does the same principle hold true then, back when Casca was an actual character and not just a plot device and projection screen for Guts?

And I would argue that it does. It’s less in-your-face about it, but tbh not by a whole lot.

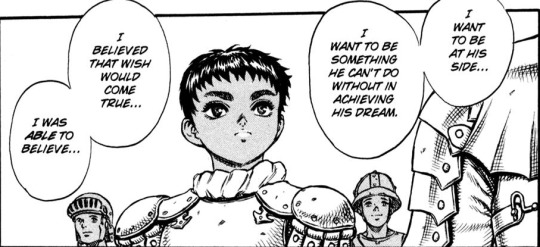

Casca and Guts start off as romantic rivals for Griffith’s affection. Only Casca is aware of this, since Guts’ attraction to Griffith is subconscious and repressed imo, but that’s their early dynamic. Their first emotionally intimate scene together, when they finally stop hating each other and start to bond as friends, is when Casca tells Guts her backstory, which happens to be almost entirely about Griffith.

The Casca chapters end with Casca crying about Griffith having fallen in love with Guts and not her (”Why... why did it have to be you?”), but all Guts manages to get out of Casca’s story is that she’s into Griffith, so after he decides to leave he starts trying to be a good bro and set them up. Finally, right before Guts leaves, Judeau introduces him to the concept of hooking up with Casca.

During the course of this conversation Guts does a kind of 180:

to

“The one who has her eye... is Griffith. That’s why... right now... I’m no good for her... like this.”

This is presented like part of Guts’ motivation for becoming Griffith’s equal is to be worthy of Casca, but we’ve seen his thought process for wanting to be Griffith’s equal, and Casca has never figured into it. He’d completely written her off before this chat with Judeau, as we see at the start, and he certainly never seemed to be consciously aware of the possibility of getting with her.

He’s been trying to set her up with Griffith for several chapters - pushing her into his arms, mentioning her dress to him, suggesting she ask him to dance, carrying her down to see him after Doldrey, saying “good luck with Griffith,” to her as he heads out, and now telling Judeau he expects them to get together.

There are three possible explanations for this behaviour:

1. Guts just wants to be a good bro and help his friends be happy together. 2. Guts is sublimating his unconscious desire for Casca into trying to hook her up with Griffith. 3. Guts is sublimating his unconscious desire for Griffith into trying to hook him up with Casca.

I think maybe Miura wants us to think it’s #2. Hence Guts’ awkward sweatdrop when Judeau brings her up, hence Guts complimenting her dress before mentioning it to Griffith, hence Guts carrying her down to him bridal style after Doldrey, hence Guts swiveling from “Less a woman I see her as... a comrade,” to “That’s why... right now... I’m no good for her... like this,” within seconds.

Yk, he’s subconsciously attracted to her now and acts on that attraction by trying to hook her up with Griffith to make her happy, but once Judeau tells him that’s not an option, he can admit that he’s attracted to her.

(And, just to throw something out there, once we establish that Berserk has subtextual, repressed sexual desire in this love triangle it only adds more validation to the other combinations. Even if we are genuinely meant to read Guts as unknowingly attracted to Casca, it puts unknowing attraction on the table. Who else might he be unknowingly attracted to? Casca also apparently took some time to recognize her feelings for Griffith as potentially romantic. Lots of subconscious desire wrapped up in this love triangle, I’m js. But lol I digress.)

That said, I’m here to argue that, whatever Miura’s intentions may be (and hell they may be exactly this), it comes across as option #3.

I’ve already gone through the first part of the Golden Age to highlight how Guts looks at him and how visuals suggest attraction. After Promrose, that fades away because Guts no longer views Griffith as reachable, rather, he puts him on a pedestal. Enter Casca, right at the point where Guts is deciding what to do with the “fact” that Griffith doesn’t give a fuck about him.

Suddenly he gets invested in setting Griffith up with Casca, who he views as more worthy of Griffith because she has a dream (be Griffith’s sword) and he doesn’t.

This is when Guts starts pushing them together. He’s encouraging Casca to take his place at Griffith’s side, whether he realizes the implications of that or not - at the very least he knows that Casca believes Griffith feels things for him she wishes he felt for her, even if Guts doesn’t believe that Griffith truly values him.

“Until that day. The day you showed up...”

What’s interesting to me is that Guts recognizes that Casca wants to fuck Griffith lmao. He’s hooking them up romantically, even though Casca never directly says she’s in love with Griffith, and only alludes to her feelings in terms of being pissed off at Guts for stealing Griffith away from her side.

Guts doesn’t believe he himself is close to Griffith after overhearing the Promrose speech, but he seems to realize that Casca is jealous of him, manages to interpret that (correctly) as Casca wanting to bone Griffith, and yet still doesn’t realize that Griffith’s feelings for him may be a lot more significant than he thinks. Feels like repression at work to me.

Guts wants Casca to take his perceived place at Griffith’s side, except Casca’s theoretically able to do so romantically bc she’s a woman, so there’s plenty of heteronormativity at work too, though whether that’s coming from Miura or Guts I can’t say.

So yeah after Judeau explains the plot of Berserk to him and keeps nudging him towards Casca, Guts agrees that maybe he could hook up with her... but only if he becomes Griffith’s equal first.

So the other way of looking at this is that, rather than suddenly changing Guts’ entire motivation out of nowhere from “become Griffith’s equal to be his friend” to “become Griffith’s equal to get with Casca,” and generally being bizarrely terrible writing, this instead neatly situates a future relationship with Casca, in which she sees him as just as good for her as Griffith, as proof that he’s on the road to achieving his goal of becoming Griffith’s equal.

Which holds true later on - Guts and Casca’s relationship is not an endgame for Guts, it’s not his goal, it’s another step. He still intends to go back out and keep pursuing his own dream. He’s still motivated by wanting to be Griffith’s equal.

So yeah, Judeau’s like, whatever, I tried, Guts ducks out, and shit proceeds to go down.

Fast forward a year.

Guts comes back. Casca, interestingly, has taken over Griffith’s most notable narrative role as leader of the Hawks. Everyone sits down around the campfire.

Rickert tries to explain things to Guts:

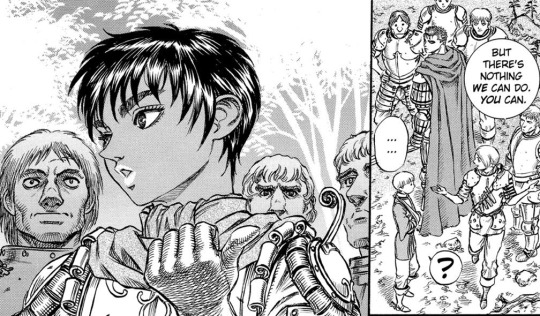

Look what Judeau does! He’s telling Rickert to shut up.

Judeau is... weirdly invested in Guts and Casca getting together. Setting them up is largely his motivation in the latter half of the Golden Age, as far as I can tell.

After this moment he changes the subject to:

Subtle, Judeau.

I think it’s telling that Guts never comes up with the idea of hooking up with Casca on his own. He’s led to it by resident shipper on board Judeau, every time. The same dude trying to avoid any mention of Griffith’s feelings for Guts now. Why? Because he wants Guts and Casca to leave together after they rescue Griffith, and he has a feeling Guts won’t want to if he figures out how Griffith actually feels about him.

Whether by accident of slapdash writing by Kentaro I actually hadn’t planned for Guts and Casca to get together, you know — it just occurred to me partway through that it’d be more dramatic that way Miura or design, Guts’ interest in Casca comes across as pretty damn narratively forced to me, and the fact that Judeau has to be there to constantly nudge Guts in that direction doesn’t help.

Waterfall time!

Hey here’s something interesting about this scene:

This is when Guts first starts trying to fix his mistakes by substituting Casca for Griffith, imo.

Casca attacks him while screaming that he ruined Griffith by leaving. As the point finally hits home, so does the point of Casca’s sword as Guts, shocked, lets her stab him.

Before Guts can really draw a useful conclusion from Casca’s diatribe, she offers a distraction from the subject at hand by trying to kill herself while bequeathing Griffith to him.

“I couldn’t be a woman. Or something invaluable. To keep on protecting the almost broken dream of someone who might not even be alive...“

Guts didn���t save the last Hawk leader who had a self destructive breakdown after dueling him.

Presented with another person who seems to need him, who is desperate and lost and needs comfort, this time he does something.

And what really makes me believe this is actually, for real the correct reading of this scene - that, to Guts, Casca is a substitution for Griffith here - is that Casca is doing the exact. Same. Thing.

Griffith is (seemingly) unreachable, (seemingly) emotionally and romantically unavailable, but Guts and Casca aren’t.

And they kiss for the first time right after Casca tells Guts how Griffith felt about him, right after Guts lets Casca stab him because of it, right after the memory of Griffith kneeling in the snow, and the beginnings of the realization that by leaving he lost what he set out to earn, hit him, right after Casca tells him that Griffith is his responsibility now. It’s hard not to take that as Guts using Casca as a substitution for Griffith, giving her what he’s now very slowly beginning to realize he should’ve given Griffith.

Guts and Casca getting together here is two people obsessed with the same person trying to offer the other what they couldn’t offer him: comfort. And sex.

Once again a scene that looks like it’s going to be about Casca and Guts, that should be if this was a typical romance, turns out to revolve around Griffith.

And on the subject of Guts leaving Griffith in the snow instead of kneeling down and kissing him the way he responds to Casca much later, how about Griffith going out and getting self-destructively laid while thinking about Guts after the duel? Thematically there’s a very well-defined empty space where Griffith and Guts connecting romantically would’ve fit, is what I’m saying, but they didn’t. They both sought out other sexual connections to compensate for the loss of each other.

Finally, here’s the straightforward account of how Guts and Casca are feeling three days later with Griffith’s imminent return to their lives. Casca confesses to Guts that she’s still jealous of Charlotte, Guts gets pissy, but then thinks:

I hate that you’re still hung up on Griffith but I’d be a huge hypocrite if I got mad because I’m even more hung up on Griffith.

Which pretty much sums it up.

And I think I can stop there. There’s a lot more to say in the lead-in to the Eclipse about Guts’ intense feelings for Griffith, but when it comes to sexual attraction specifically, and how Casca figures into it, I think I’ll call it a day.

I hope I’ve made a decent case for Guts’ feelings for Casca, both positive and hugely fucked up, being largely built out of redirected feelings for Griffith. Whatever the reasons for this - actual authorial intent, intended redirection of Guts’s platonic bro feelings but adding sex bc Casca’s a woman so it’s obligatory without realizing how gay that looks, me totally reading into a half-assed het subplot created for the sake of more Eclipse drama, whatever - this is earnestly how Guts’ relationship with Casca reads to me.

In the final part I’m going to conclude this epic adventure in homoeroticism with what is essentially a “why I ship them,” going into why I think it makes perfect sense, from both a character and a thematic perspective, for Guts to be sexually attracted to Griffith. Stay tuned.

shout out to @mastermistressofdesire bc we’ve had a few conversations about this subject and some of your ideas really helped me coalesce these thoughts. Ty!

Part Four

#griffguts#a#tbh this is so long that i think i've wasted some good observations by burying them in this monster lmao#i might cannibalize this thing a bit later on and repost some of these ideas so they're more easily accessible#this is late bc i had a headache last night and didn't feel like editing it#b#theme: love triangle#ship: gtsca#theme: repression#theme: heteronormativity#scene: hill of swords#ship: griffguts#character: guts#theme: parallels#character: judeau#character: casca

251 notes

·

View notes