#André Bazin

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Como la muerte, el amor se vive y no se representa –no sin razón se llama la pequeña muerte, o al menos no se representa sin violar si naturaleza–. Esta violación se llama obscenidad. La representación de la muerte real es también una obscenidad no ya moral, como en el amor, sino metafísica. No se muere dos veces.

—André Bazin, «Muerte todas partes» en ¿Qué es el cine? Traducción de José Luis López Muñoz.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

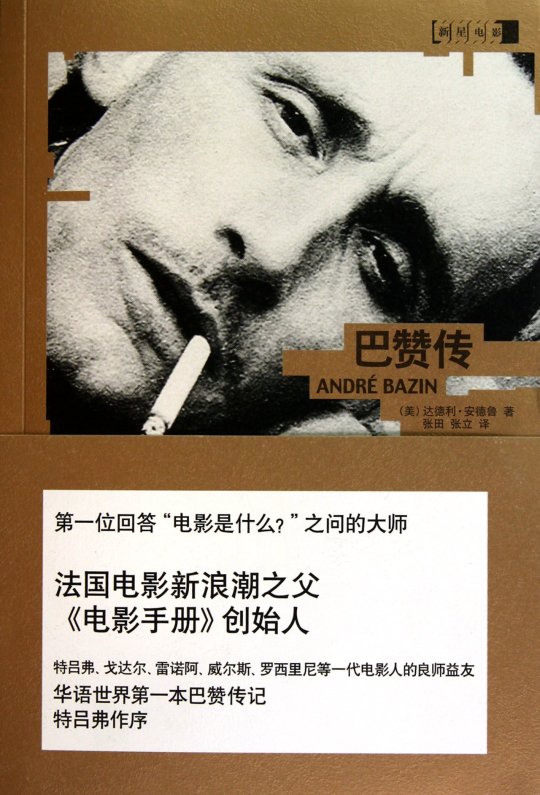

André Bazin, April 18, 1918 – November 11, 1958.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

In una psicanalisi delle arti plastiche la pratica dell’imbalsamazione potrebbe essere ritenuta come un fatto fondamentale della loro genesi. All’origine della pittura e della scultura, ci sarebbe così “il complesso” della mummia.

André Bazin

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Le Mépris (1963), Les Carabiniers (1963), Masculin Féminin (1966) Weekend (1967)

Dir. Jean-Luc Godard

#jean luc godard#french new wave#nouvelle vague#60s#contempt#le mépris#le mepris#jean pierre leaud#french cinema#cinema#masculin feminin#weekend#les carabiniers#andré bazin

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

"If the origins of an art reveal something of its nature, then one may legitimately consider the silent and the sound film as stages of a technical development that little by little made a reality out of the original "myth." It is understandable from this point of view that it would be absurd to take the silent film as a state of primal perfection which has gradually been forsaken by the realism of sound and color. The primacy of the image is both historically and technically accidental. The nostalgia that some still feel for the silent screen does not go far enough back into the childhood of the seventh art. The real primitives of the cinema existing only in the imaginations of a few men of the nineteenth century, are in complete imitation of nature. Every new development added to the cinema must, paradoxilcally, take it nearer and nearer to its origins. In short, cinema has not yet been invented!" André Bazin, What Is Cinema (1967)

1 note

·

View note

Text

Renowned film critic André Bazin with cat friend, 1950. Source.

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

“Why is dialogue so emotionally exaggerated in Japanese film?” one reddit user asked.

The response HarryMcFann gave is an incredible primer to understanding Japanese performance style and the media influenced by it (I’m looking at you, BLs and Kdramas).

“Not claiming to be an expert or have a definitive answer here, but these are my two cents based off of what I know about Japan and Japanese film. This is a very general overview. It’s important to note that culture is complex and full of nuances, but this should give a general understanding as to why Japanese films are somewhat exaggerated.

As u/scytheavatar pointed out, Japanese film is influenced by Japanese theater, but that doesn't fully answer your question. For example, you may ask about Western theater as it relates to Western films, and so on (Western theater is exagerated, but films today aren’t). So let’s look at Japanese theater.

The three main forms of Japanese theater are Kabuki, Noh, and Bunraku, and each of these forms influenced Japanese films in different ways. Now what is important to note here is that back in the early years of cinema, those in France and the rest of the West saw film as a new form of photography, while the Japanese viewed film as a new form of theater. Just think about that for a second, and what the implications are. Back in the late 19th and early 20th century the big thing about photography was it’s ability to capture realism, and that realism was a huge concern for many Western filmmakers. The famous French film critic, André Bazin, wrote extensively about how he believed the essence of cinema is its ability to reproduce reality (there were, of course, Western filmmakers who rejected this notion, such as the Soviet formalists and German expressionists, but going into that would require a lot more words). In Japan this was not the case, and from its inception, the Japanese rejected the Western idea of cinematic “realism.”

How did this manifest itself in early Japanese cinema? One thing the Japanese directly took from theater was the presence of a narrator. Japanese silent films were always accompanied by someone called a Benshi (fun fact, Kurosawa’s brother was a benshi), who would narrate the film. Japanese silent films would then have few intertitles, because the benshi would be there to explain the plot, and so on. What’s more, audiences would often attend a film based off of which benshi was performing. The benshi where local celebrities in many ways, and they would try to one-up one another. So naturally, to give a good show, the benshi would have to exaggerate in order to give more life to the performance (these guys would voice characters and play all the different roles). Directors would make their films knowing that there was going to a benshi present. So popular was the benshi, that much of the resistance to transitioning into talking films was from those lamenting the loss of the benshi narrators. Japan actually finally made the transition into talking films much later than the rest of the world.

It is also important to understand that “realism” is a relative term (cue some 15-year-old calling me pretentious). Yes, Western theater is also exaggerated and not particularly realistic, but traditional Western theater really doesn’t compare to Japanese theater. In fact, the famous German playwright, Bertolt Brecht, based many of his ideas of modernism in theater on traditional Japanese theater. This is why Ozu is seen as the most “traditional” of Japanese filmmakers while also being viewed as an early “modernist.” (It’s all really confusing and requires a bunch of quotation marks). Anyway, the Japanese don’t really have the 4th wall in theater the same way we do here in the West. In Japanese theater, audience interaction is huge, and stagehands (albeit often wearing black) walk freely on stage and move props and scenery around the actors, and so on. The key difference here between Japanese theater and Western theater is that while the West try to disguise and mask the artifice of the stage, the Japanese embraced it. A quick example of the way a Japanese actor performs in theater would be the Mie. The Mie is a powerful and emotional pose struck by an actor, who then freezes for a moment. This pose is more for the audience than the drama of the play, and often times reveals important information about that character. This idea of the artificiality of the performance in theater can also be seen in Japanese film.

Finally, it is worth noting how the Japanese view nature vs how the West does. In the West, we look at the natural as being something untouched by people. Interestingly, this isn’t really the case in Japan. In Japan there’s a belief that something only becomes “natural” when it has been in some way shaped by a person. Weird, right? To quote Donald Richie:

“To most Japanese, the Western idea of “realism,” particularly in its naturalistic phase, was something truly new. All early Japanese dramatic forms had assumed the necessity of a structure created through mediation. The same was true of Japanese culture in general: the wilderness was natural only after it had been shaped and presented in a palpable form, as in the Japanese garden, or flowers were considered living (ikebana) only after having been cut and arranged for viewing. Life was thus dramatically lifelike only after having been explained and commented on. Art and entertainment alike were presentational, that is they rendered a particular reality by way of an authoritative voice (be it the noh chorus or the benshi). This approach stood in marked contrast to the representational style of the West in which one assumed the reality of what was being shown.”

I want to make it clear that not all Japanese films are like this. If you watch films by a director like Hirokazu Koreeda, you will not see the same sort of exaggeration.”

#bl drama#performance studies#Japanese bl#Thai bl#ql drama#korean bl#kdrama#anime#the world is wide#and history is long

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

iwtv 2.02 ‘do you know what it means to be loved by death’ / andré bazin ‘ontology of the photographic image’

#it’s a reduction 🕺🕺#so when is louis gonna meet bazin#iwtv#iwtv spoilers#does this count as revision#😔😔😔

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

'I’ll be looking at the moon, but I’ll be seeing you.’ Alkazi Foundation

Hari Katragadda, in collaboration with writer and artist Shweta Upadhyay, won the prestigious Alkazi Grant for their ingeniously intense photobook titled 'I’ll be looking at the moon, but I’ll be seeing you.’ Hari said the project was inspired by the opening scene in Jean Luc- Godard’s Le Mépris (1963) and the Billie Holiday song, I’ll Be Seeing You (1944).

"The cinema substitutes for our gaze a world more in harmony with our desires."

André Bazin, French film critic

This famous quote shines brightly on-screen in the opening sequence of Le Mépris. The idea of desire is the thematic crux of Hari and Shweta’s photo book. Hari conceived the idea and translated it into this photo series through the expressions of the protagonist, his partner Shweta. The series is a tribute to the ephemeral moments filled with memories of loves lost and a yearning for the reawakening of love. It attempts to capture ways of seeing and perceiving one’s lover, desire, the lack thereof, and the heartache that follows a search for the elusive other...

#Hari Katragadda#Shweta Upadhyay#'I’ll be looking at the moon#but I’ll be seeing you.#photobook#photobooks#books

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

MOVIES I WATCHED THIS WEEK #211:

SABELLE HUPPERT X 3:

🍿 ISABELLE HUPPERT, A LIFE TO PLAY is a wonderful biography shot in 2001. The director followed her for a whole year during her work with Chabrol on 'Nightcap', just before her 'Piano teacher' premiere and winning in Cannes, and documents her preparations for the live performance as Madea on stage in Avignon. Pure pleasure to anybody who loves to see her anywhere.

🍿 THE SWINDLE (1997), an old-fashioned grifter caper and my 12th crime comedy by Claude Chabrol. Huppert and her much older partner Michel Serrault con small time dentists and insurance men at conventions, but then they move on unto bigger and more dangerous scams. Chabrol's accomplished handle of the story is a joy to behold. 8/10.

Chabrol directed Huppert in 7 movies, of which I've seen three. But I must see them all, with the first being 'Violette Nozière'!

🍿 Narrated by Isabelle Huppert, FRANÇOIS TRUFFAUT, MY LIFE, A SCREENPLAY is the new documentary about the auteur "Frank Truff". It was a project he started himself, before dying too young at 52. As such, it's not great: fragmentary, unfinished and it jumps randomly from period to period. But it offers many wonderful clips from his personal life, with some new insights as to what influenced him the most: His pained relationship to both his parents, how important were children to his world view, his early friendship with Jean Genet and André Bazin. Recommended at any Truffaut fan. (I need to hunt down the last few of his films that I didn't see, especially 'Mississippi Mermaid', which is hard to find). (Ending Scene From His 'Les Quatre Cents Coups' Above).

🍿

First watch: MIRROR, my 6th or 7th poetic film by Andrei Tarkovsky, and without any doubt my favorite film by him. I can't understand why I waited so long to see it. An emotional and visual masterpiece, about fragments of dreams and small pains of memories. Why is this film so magnificent? The boy's mother, who was Tarkovsky's real-life wife, was angelically beautiful. I am going to re-watch this film again and again. 💯 score on Rotten Tomatoes. 10/10.

🍿

"Basically, I show up at work in the morning and ask: Who's dead?"

What goes into creating the right, balanced obituary? I did not expect to find the 2017 documentary OBIT so engrossing. It's a straight-forward, talky look into the writers of the small obituary desk at the New York Times, and how they do their work. The journalists interviewed were intelligent and reflective people, with insights and stories to tell. It turned into thoughtful study of fame and mortality. And their enormous, defunct "Morgue" of paper files! The NYT of today is just a shadow of what it was only a decade ago, and I'm sure most of all these smart people are no longer there. 9/10. [*Female Director*]

🍿

2 BY WILD HUNGARIAN PAINTER MILORAD KRSTIĆ:

🍿 MY BABY LEFT ME (1995) is a psychedelic, erotic vision of having sex in all the most explicit ways, but drawn in a cubist, surrealistic style. 1940's Picasso would have loved it! A must see for anybody who loves abstract pornography.

🍿 "My nightmares are getting stronger and stronger..."

How come I've never heard of his first eccentric feature film RUBEN BRANDT, COLLECTOR from 2018?? Not too crazy about animation, especially when mixed with crime-Noir trops like kung-fu fighting, car chase, action killings Etc. But this original pop-art story of kleptomaniac, circus-trained acrobat art thief Mimi is rich with so many throwaway references and avant-garde Easter eggs, that I was compelled to watch this extraordinary Art History Course twice back-to-back.

The beauty starts around 0:12, and doesn't stop until the end. The end credit mentions some of its inspirations: CIA subliminals, Warhol's Double Elvis, Hitchcock ice-cube cameo, Joan Miró soup, Peckinpah’s 'Convoy', 'Oops, I Did It Again', Soviet propaganda, the black cat from Manet's Olympia, hundreds more...

This will surely become my January's most memorable viewing: Highly recommended - 9/10 and 10/10.

EXTRA: So I had to watch my other Hungarian animation favorite, Réka Bucsi's SYMPHONY NO. 42 - again, for the 15/20 time... I think I'll just put it on every week, like a record of a song you love.

🍿

2 JAPANESE DRAMAS:

🍿 THE INHERITANCE (1962), my 4th jazzy Noir thriller by Masaki Kobayashi. A dying industrialist wants to divide his $7M estate between his young wife and 3 heirs he bore out of wedlock, and everyone around him schemes to get a piece of it. The corrupting influence of greed, lust, betrayal and selfishness. It includes a rape scene which radicalizes the only impartial character, the CEO's loyal secretary, and turns her into another revenging vulture.

Next on my list - his nearly 10 hour epic 'The Human Condition'.

🍿 MEGANE (GLASSES) (2007) is my second film by Naoko Ogigami, and a companion piece to her 'Kamome Dinner', which I enjoyed so much last week. It even features 2 of the same 3 actresses who played 'lost in Helsinki' in the previous story. But the super-minimalist, "eclectic" plot of an anti-social woman on vacation on a tiny, remote resort inn, where nearly nothing happens, and where everybody takes comfort in doing nothing, bore me for 25 minutes. ⬇️Did Not Finish⬇️ - Sorry! [*Female Director*]

🍿

ETERNITY AND A DAY (1998), my first Greek Magical Realism work by Theo Angelopoulos. It's a story about me, memories of an old poet who's about to die, remembering the many people in his life who are no longer there, and regretting all the decisions that brought him to where he is now. In the end, the only person sharing this last day in his life is a random boy, an Albanian "Squeegee kid" whom he rescues from the police. ''My only regret, Anna... is to not have finished anything. I left all as a draft, shattered words here and there.''

🍿

3 WITH TILDA SWINTON:

🍿 CAPRICE (1986), my first by Joanna Hogg, was also Swinton's very first film, credited here as "Matilda Swinton", made while they were both in art school. An Alice in Fashion-land trifle about a young woman who enters and lives inside a fashion magazine. British New Wave /Duran Duran style nonsense. [*Female Director*]

🍿 THE SLUGGARD (Also 1986, starts at 38:00) was a wordless artsy film school-type attempt at symbolism. She plays a dirty slob.

🍿 Joshua Oppenheimer's new apocalyptic THE END was hailed by David Ehrlich and other critics, as a ground-breaking achievement and the best musical of 2024. So I was excited to finally be able to see it. It opens with a TS Elliot quote, and it stars oil tycoon Michael Shannon and wife Tilda Swinton who fortified their family in a salt-mine luxury bunker 25 years after everybody on the surface of the earth perished. A bold and ambitious project, like 'The umbrellas of Cherbourg', it combines a meditation on the lies and the guilt of being left behind, with characters who burst out singing whenever they want to underscore a painful emotional point. But in the end, it didn't work for me; Except of one beautiful song, If only I, the rest of the score, as much as it tried to emulate Stephen Sondheim, was forgettable, and at the end of the 2.5 hour run, the dramatic interactions of the family felt like an unfocused soap opera. 5/10.

(I was going to follow up with his 'The Look of silence', the companion piece to the masterful 'The act of killing', but never got to it.)

🍿

"You took your shot, now I'm taking mine".

When Taylor Ramos and Tony Zhou, of 'Every Frame a Painting' fame, stopped producing terrific videos 8 years ago, they penned a thoughtful 'Postmortem’ piece. When they returned last September with new essay, THE SUSTAINED TWO-SHOT, they teased of their first live-action narrative short.

THE SECOND is that short, and it feeds on all the insightful knowledge seen in their videos. How exciting!

It dropped yesterday together with another essay, WHERE DO YOU PUT THE CAMERA. It all makes sense now!

And then, they also posted a bonus video of 'Behind the scenes - Animatic vs. Final'.

More: IN PRAISE OF CHAIRS.

🍿

2 BY ISRAELI DIRECTOR SHIRA HAIMOVICI:

🍿 THE HISTORY OF LONELINESS (2013) tells of a young woman who's addicted to attending 'Shiva' sittings. Like Harold of 'Maud's, she clips death announcements from the papers, and visit the homes of the grieving families. Until that time...

🍿 SUMMER SHADE (צל בקיץ) (2020) starts as an un-interesting story about a vacationing teenage girl cooling off alone in a waterhole in the mountains. But then it becomes very interesting when 4 ultra-orthodox Jewish young men arrive at the little pond for a ritual immersion "tevilah", and chase her off. [*Female Director*]

🍿

METRONOM (2022) is an anxiety-filled Romanian drama taking place in Ceaușescu's oppressive Bucharest of 1972. The first half is an unfocused story of an ordinary teenage girl who's boyfriend is about to leave the country with his family. It's a drab and noisy world, boring and joyless.

But in the evening she goes to a party and they dance to the corrupting music of Jim Morrison. It is being transmitted from an off-shore 'Free Europe' station which was illegal at the time, and everybody's life changes dramatically when the Romanian secret police bursts in and arrests all the kids for treason against the state. It turns sharply depressing very quickly.

🍿

MY FIRST TWO WITH ROBERT TAYLOR:

🍿 THE LAST HUNT was a hard watch. A revisionist western about the genocide of the American Indians, told via a story of two buffalo hunters, one evil and one who had a nominal change of heart. The American original sin, even before importing black slaves from Africa, was the deliberate extinction of all Native Americans. When not slaughtered outright, their way of life was destroyed through the annihilation of the massive herds of buffaloes which sustained them. This movie shows some of the killings, simulated or not, and is generally very unpleasant, even for meat-eaters. It was made in 1956, and unsurprisingly did not do well in the box office.

Robert Taylor plays the Bad Guy as a cruel, self-loathing sadist, an open racist and a mean rapist. But he ends up frozen to death, in a similar position to the one Jack Torrance found himself.

🍿 THE HOAXSTERS (1952) was a shameless piece of American Cold-War, anti-communist propaganda, a "Documentary" made during the height of McCarthyism's reign of Red Terror Scare. Wow! The virulent demagoguery is hysterically prescient. Capitalism version of "Triumph des Willens". You have to see it to believe it.

Robert Taylor was one of the narrators. It's strange that his real-life good friend Ronald Reagan didn't participate.

🍿

SPLASHBACK (2024) is a black-and-white, old-fashioned comedy about a "Milton"-type mousey guy who works in the supply room at Cape Canaveral during the Apollo 11 launch, and who invent the "pee net" you put in the urinals. It looks like an elaborate American production, but it's actually a small-time Croatian gig done on a shoestring. The best part was the title sequence done in 100% Saul Bass style. 3/10.

🍿

THE ONLY LAUREL & HARDY PREQUEL-SEQUEL COMEDIES:

🍿 "He who filters your good name, steals trash."

TIT FOR TAT (1935) was apparently the only sequel these two made, a perfectly excellent 2-reel comedy. A feud between two neighboring store owners with a fine escalation of grievances, while a customer helps himself to free goods from the store which they neglect. 7/10.

🍿 THEM THERE HILLS, made 5 months earlier, was so successful, that they went ahead and followed it with 'Tit for tat'. But that was of distinctively lower quality. Oliver Hardy was really abusive to his pal, here and actually, always.

🍿

THE GRANDMOTHER (1970) is my 7th or so film by David Lynch. I swear that it was on my planned watch-list for this week, even before the news of his death broke. It's a 33 min. experimental short about an abused boy who "grows" a grandmother from a "seed". I'm sorry that he dies, but I never liked any of his films too much, and didn't like this one either. 1/10.

RIP, David Lynch!

🍿

THIS WEEK'S SHORT FILMS:

🍿 NIGHT BUS (2019), a strange and nightmarish Taiwanese animation with a mysterious plot that get weirder, more violent and uglier for 20 straight minutes. Atmospheric score and unusual visual style. CW: Monkey death, brutal vengeance, unrequited love.

🍿 In WILD LIFE (2011), a young Englishman moves to the Canadian prairie province of Alberta in 1909. A wonderful short by Canadian animator duo Wendy Tilby and Amanda Forbis, and their first of two nominations for the Academy Award. Brilliant imagination, extremely well told. This is my third shot by them, after 'The flying Sailor' and 'When the day breaks'. 9/10 - Recommended! [*Female Directors*]

🍿 A STAR IN THE NIGHT, Don Siegel'e directorial debut, earned him one of the two Oscars he won in 1946 (The other was for his documentary short 'Hitler Lives'.) It's a modern day retelling of the Nativity story plus some elements from 'A Chris!mas's Story' thrown in. 3 cowboys riding in the desert and find a motel somewhere in Arizona or so, with Nicky, its mean owner with the thickest Italian accent you ever heard. I've never seen a more sentimental hogwash in all'a my life! But it worked! 8/10.

🍿 A PURE SPIRIT (2004), my 5th by Mia Hansen-Løve , and her very first short. Basically, it's just a poetic exercise of a young woman walking in the park. [*Female Director*]

🍿 THE WINDSHIELD WIPER won the 2022 Oscars, and I'm sure I disagree. Interesting Rotoscope cell animation, but otherwise it's a collage of unrelated snippets about modern dating. There's some hipster sitting at a cafe, smoking a whole pack of cigarettes and asking himself 'What is love?'. 2/10.

🍿

THROW-BACK TO THE ADORA ART PROJECT:

The whole Adora Art Project!

🍿

(ALL MY FILM REVIEWS - HERE).

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

André Bazin, April 18, 1918 – November 11, 1958.

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

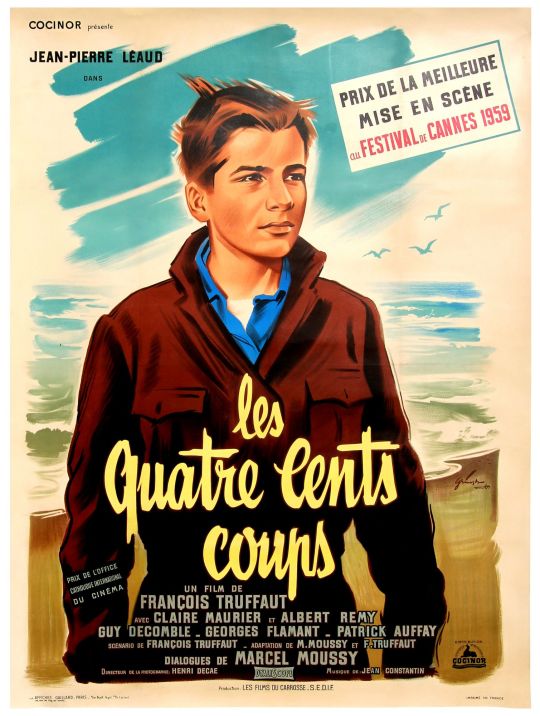

The 400 Blows/Les Cuatre Cents Coups (1959)

By Cris Nyne

The directorial debut of pioneering French filmmaker, François Truffaut’s The 400 Blows, left a lasting imprint on the timeline of international cinema. To know Truffaut’s history before becoming director makes the film even more of a remarkable achievement. His life began as a troubled youth, engaging in petty crimes and was well on his way to a path of self-destruction. It was in his late teenage years when recognized film critic André Bazin would take Truffaut under his wing and give him a job as critic for the film magazine Cahiers du cinéma. During this time, Truffaut would become recognized as a brutal critic of French films. His infamy stretched to Festival de Cannes, where he would be denied accreditation in 1958. The following year in 1959, Truffaut would get his revenge by being crowned Best Director for The 400 Blows at Cannes. This all by the age of 27. Truffaut would continue to turn the film industry on its head and help pave the way for what today is known as French New Wave.

“If the New Wave marks the dividing point between classic and modern cinema (and many think it does), then Truffaut is likely the most beloved of modern directors -- the one whose films resonated with the deepest, richest love of moviemaking.” -Roger Ebert August 8, 1999

The 400 Blows is a semi-autobiographical tale that follows the young star Jean-Pierre Léaud as the mischievous Antoine Doinel. Antoine is humiliated by his teacher, skips school, steals, and smokes cigarettes while contemplating a better life A life away from his father’s failures and his mother’s affairs. Both parents find themselves exhausted of all options for their son (or the lack of attention they care to provide) and send him off to a school for troubled children. From the beginning of the film, his parents seem to have other priorities in filling the hole in their marriage, and Antoine is essentially a victim of having too much unsupervised time on his hands. By the end of the film, Antoine is contemplating his life outside of the observation center for delinquent youth. He makes a dash for it.

Source: Blu-ray.com

“The movie is full of actual incidents from Truffaut’s childhood, including his fabricating his mother’s death as an excuse for truancy. Few movies have been so personal.” -J.Hoberman, The New York Times September 21, 2022

The movie was well received by audiences and critics alike. He won Best Director at Cannes in 1959, as well as a nominee for the Palme d’Or, the highest prize awarded at Cannes. The French regional newspaper Nice-Matin claimed The 400 Blows to be “A Masterpiece”. The chemistry between Léaud and Truffaut was strong. They would go on to make three more feature films with Léaud revising his role as Antoine Doinel, Stolen Kisses (1968), Bed and Board (1970), and Love on the Run (1979). Currently, Rotten Tomatoes lists The 400 Blows with a rating of 94%.

Original Movie Release Poster

The film is in black and white and is shot in a very personal manner. There are lots of close-space encounters that make you feel as if you are squeezing into the room with them. The house that Antoine lives with his mother and father is very small. During one scene as Antoine is sleeping, his mother, Gilberte Doinel (played by Claire Maurier), comes home after a long night and cannot open the door all the way as it is stopped by the mattress that Antoine sleeps on. There are many fun street scenes shot from different angles- subterranean, street-level, and roof tops, that portray Antoine and his friends plotting and scheming around the streets of Paris. There are a few scenes that follow the main character along a stretch of blocks, and I found myself thinking about how smooth the camerawork was.

youtube

During its filming and release date, The 400 Blows took the idea of conventional filmmaking and shredded the blueprint. The director was only known as a stubborn critic and the main star of the film was completely unknown. The script was a unique story, one that, for the most part, Truffaut had lived and had made it through to tell the tale of a rebellious and delinquent child on a bad path. A child that by today’s standards would probably be diagnosed with an attention deficit disorder and prescribed medication. What was once an extremely unconventional approach to filmmaking has now become a standard in delivering a storyline. Truffaut’s confidence in leaping from critic to auteur has left a rippling effect that you can still see over 7 decades later.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

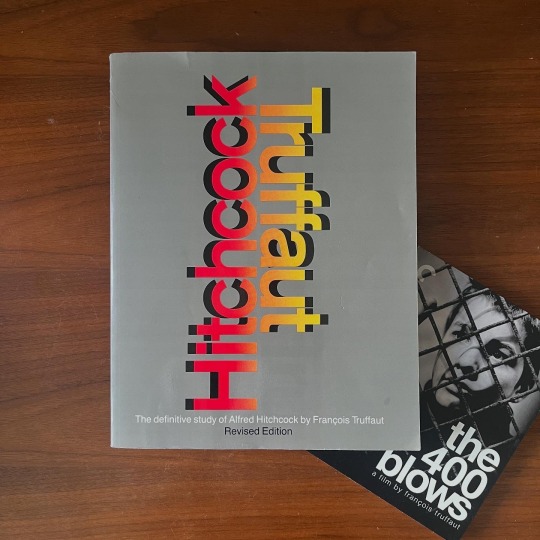

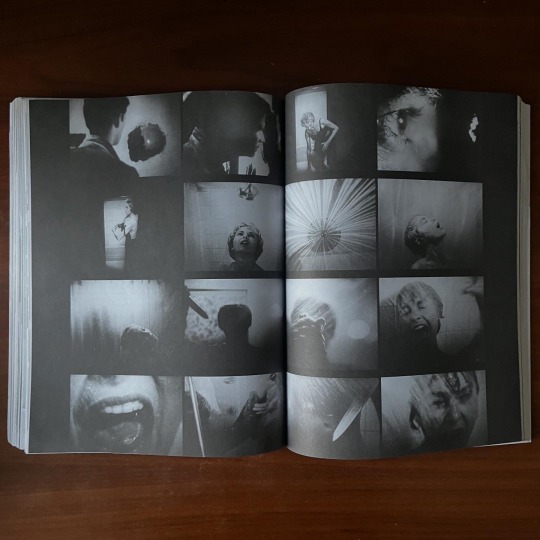

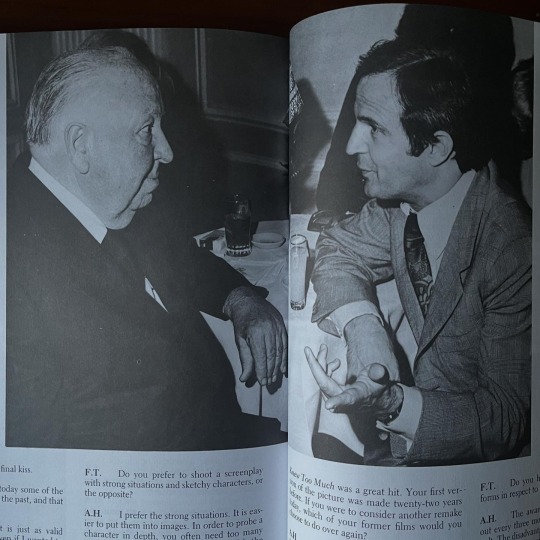

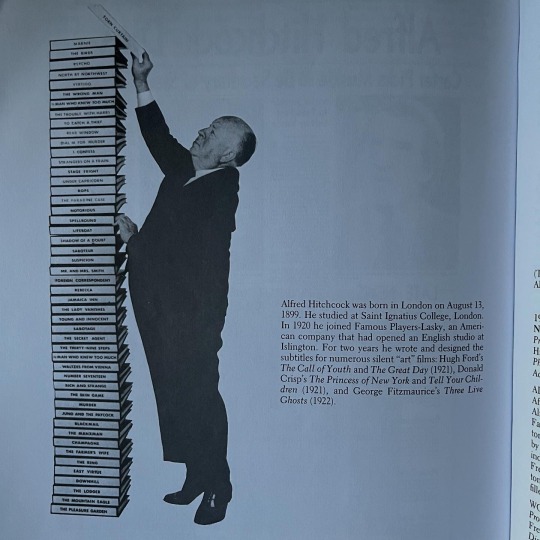

#finishedbooks Hitchcock Truffaut by François Truffaut. This is a re-read, I had read this back in 2007 as one of my first film books. It was this book, then Donald Richie's 100 Years of Japanese film, and a random French New Wave book that kinda started my cinephile ...I don't know journey lol. Guess to explain Hitchcock, there was a great essay by André Bazin in his best work, "What is Cinema?" where he essentially cites two types of auteur directors. One that makes films with the audience in mind and one that makes films for themselves. Neither bad but the former he used Hitchcock as an example and think Godard was the latter...but that's what Hitchcock does and with this book you essentially are given a chance to sit in on one of the greatest conversations on film by two of the greatest minds in cinema representing these opposite motivations. It was well known that Cahiers du Cinema, who Truffaut wrote for before making films himself, loved Hitchcock at a time when he was seen as a camp director certainly not to be taken seriously. Reading the book back in '07 I remember my biggest takeaway that Truffaut highlighted was Hitchcock's lack of plausibility in his films, most notable being for example in say "Birds" where there happens to be a bird expert in the room right before the birds attack lol. The truth though is that he is rarely implausible. What he does is hinge a plot around a striking coincidence which provides him with a master situation where his treatment from there consists in feeding maximum tension and plausibility into the drama...building toward a paroxysm then boom he like lets go suddenly and allows the story to unwind swiftly. I never been much of a fan of plot in favor of what prefer in story for the possibilities and more realistic rhythms of reality it represents...but I love his plots because they are so absurd often utilizing what became none as a macguffin (an intentionally meaningless device to advance a plot). But more importantly is how he avoids being a simple storyteller nor an esthete...he is one of the greatest inventors of cinematic form like a Murnau to me or Eisenstein who I am always surprised doesn't draw more comparison when thinking of say the staircase scene in Potemkin. They share this mind in which the analytic and synthetic are simultaneously at work making its way out of the fragmentation of shooting, cutting, and the overall montage of film. Hitchcock then to me underlies this genuine artistry of anxiety that I can only relate to in literary terms a Kafka, Dostoevsky or Poe... as absurd as it would seen with Hitchcock. Another underrated point is his general economical approach that I always compare to Ozu. Take "Rear Window," opening scene is a slow pan of the apartment and through one shot it established the film's entire background. We see he is a photographer, he has done a lot, he shot a race and had an accident, he has a girlfriend we see in a photo, we see his room, and boom we end up on him on a wheel chair with his cast on and camera in hand looking out his rear window before his girlfriend enters the apartment. We get everything without a single word spoken...that is he showed instead of saying which is cinema...a purely visual language. I find these directors that came into silent films toward the end (late 20s) who all peaked post war especially because they truly understood the significance of this as silent films directors. A comparable Ozu scene would be from say "Late Spring" in the middle of the film where we realize the father might be marrying and leaving the daughter through precisely 20 scuts during a noh performance they are attending where a single word is never uttered. The cuts simply reveal her observing her father and his potential suitor watching the play, to cuts of her suddenly realizing, ensuing sadness, then a cut to the tree that is painted on noh stage wall, and finally a cut to a real tree blowing in the wind that in haiku symbolizes a permanent change. This is why I love cinema haha, I could ramble on but ya, this is a must have book.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

#TalkieTuesday Jacques Tati in a 1958 interview with André Bazin and Truffaut on inspiration, Buster Keaton. He slightly misremembers the scene - thanks to @DannyDrinksWine on Twitter!

#talkie tuesday#buster keaton#jacques tati#quote#kathryn mcguire#donald crisp#the navigator#1920s#silent era#silent movies#vintage hollywood#ibks#the international buster keaton society#buster keaton society#the damfinos#damfino#damfamily

4 notes

·

View notes