#A Grief Observed full text pdf

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

“How Often Does Such a Bright Moon Come Around?” (水調歌頭 · 明月幾時有) Translation

(Another year, another Mid-Autumn Festival, another poem translation. This particular poem is very famous because of the first and last lines, which are frequently referenced in popular culture. Happy Mid-Autumn Festival!)

How often does such a bright moon come around?

By Su Shi (Song dynasty, 1076 AD)

Mid-Autumn of the year Bingchen (2), drank all night in celebration, became heavily inebriated. Composed this poem to commemorate this occasion, and in dedication to Ziyou (3). (4)

How often does such a bright moon come around? With wine in hand, I ask the heavens.

Wondering what year it is for this day in heaven (5), in the palace high above.

Wishing to ascend on the wind, yet I cannot stand the chilly air around those lofty towers of jade.

Dancing and amused at my own crisp shadow, the frigid heavens surely cannot compare to the mortal realm below.

Rounding the vermilion building, hanging low near the intricate windows, the moon casts light over the sleepless (6).

The moon should not feel bitter jealousy, so why is it only full on parting?

Humans feel grief and joy, partings and reunions, just as the moon waxes and wanes.

For both of these heartening things (7) to happen together is very rare indeed.

May we be blessed with longevity, so that even when thousands of li (8) apart, we can still gaze upon this wonderful moon together.

—————————-

Notes:

This poem is in the Ci/词 format, and follows the rhyme scheme (Cipai/词牌) called Shuidiaogetou/水調歌頭/水调歌头.

Bingchen/丙辰 is a year in the Chinese Sexagenary Cycle, which is known in Chinese as Tiangandizhi/天干地支 ("Heavenly Stems and Earthly Branches") or simply Ganzhi/干支 ("Stems and Branches"), and is used to record time. This system has been in use since at least the Shang dynasty around 3000 years ago (oracle bone artifact bearing inscriptions of ganzhi has been found at Yinxu/殷墟, the archaeological site of the ancient capital of Shang dynasty; however, during Shang dynasty the Ganzhi system was used to track days and not years, unlike how it has been used in later times). Because there are 60 years in one cycle, it is possible to trace back to specific years. In this case, Bingchen would be exactly 1076 AD.

Ziyou/子由 is the courtesy name of Su Shi's brother, Su Zhe/蘇轍.

This section is a short introduction to the poem, which begins after this section.

This may be a reference to the concept that "a day in heaven is a year on earth" ("天上一天,地上一年"; famously included in Journey to the West), which in turn is a reference to the ecliptic plane (called Huangdao/黄道 in Chinese), since for an observer on Earth, the Sun appears to move in an elliptical path throughout the year. This means that it takes a year (i.e. "a year on earth") for the Sun to "complete" one round in this elliptical path (i.e. "a day in heaven").

Here, "the sleepless" is a reference to the poet himself.

"Both of these heartening things" refers to reunion with family and/or friend, and the occurence of a full moon.

Li/里 is a traditional unit of distance. During Su Shi's time (Northern Song dynasty, 960 AD - 1279 AD), 1 Li ≈ 576 meters = 0.576 km or 0.36 miles (Note: link leads to pdf).

—————————-

Original Text (Traditional Chinese):

《 水調歌頭 (1) · 明月幾時有 》

[宋] 蘇軾

丙辰中秋,歡飲達旦,大醉,作此篇,兼懷子由。

明月幾時有?把酒問青天。不知天上宮闕,今夕是何年。 我欲乘風歸去,惟恐瓊樓玉宇,高處不勝寒。起舞弄清影,何似在人間。

轉朱閣,低綺戶,照無眠。不應有恨,何事長向別時圓? 人有悲歡離合,月有陰晴圓缺,此事古難全。但願人長久,千里共嬋娟。

#mid autumn festival#midautumnfestival#chinese poem#poetry#how often does such a bright moon come around#my translation#明月几时有#苏轼

186 notes

·

View notes

Text

Energetic Influence of Ayahuasca

Energetic Influence of Ayahuasca as Measured Using Bio-Well Technology (GDV) during an Ayahuasca Ceremony.

Konstantin Korotkov, PhD., Professor and Michael Borkin, N.M.D.

Introduction

Energetic Influence of Ayahuasca Ayahuasca is a very special herbal medicine that originated with the Indigenous peoples of Amazonian Peru. Evidence from pre-Columbian rock drawings suggests hundreds of years of Ayahuasca use in the Amazon, although Western scientists and explorers have only been exposed to the brew over the last 150 years. Ayahuasca is a powerful psychedelic, capable of producing profound states of altered consciousness, and is not a recreational drug. Some who consume the brown-reddish, bitter tasting brew have experiences of universal love, bliss. However, the real effects manifest approximately two days after the first ceremony when the transformation is in its final stage, when a tenfold increase of DHEA sulfate is experienced.

Energetic Influence of Ayahuasca Research

Previous studies of Ayahuasca have concluded that the DMT and MAOi present in the brew increase Catecholamine levels and receptor activity, and furthermore, the increases in Serotonin, Dopamine, GABA levels are responsible for the heighted state. HRV studies in the same environment under similar conditions showed a remarkable increase in High Frequency signals, indicating an increase in sympathetic arousal. This was also observed within the Endocrine activities with a tenfold increase of DHEA sulfate observed forty-eight hours after baseline recording. (Baseline was 8am on the morning prior to the ceremony.) Symptoms experienced were also reflective of the high level of arousal. .

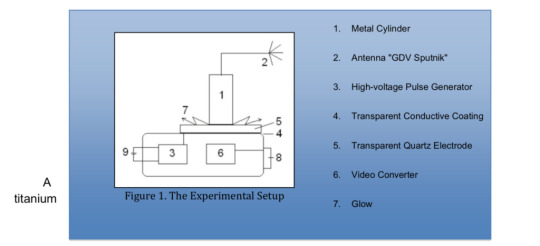

Energetic Influence of Ayahuasca Materials and Methods A device with a specially designed sensor called the “Sputnik Antenna” is used to monitor the energy of the environment and its effects on emotional status. The Sputnik Antenna is a specialized Bio-Well device that measures the environmental energy in a room, and enables the observer to witness energetic variance when people meditate, pray or listen to a presentation . This is a factor of Electrophotonic Imaging Technology . The physical principle of sensor activity is based on measuring the electrical capacitance of a space by using two grief and anger, as well as other powerful emotions. Its hallucinogenic effects begin to be felt and oneness. However, for many, Ayahuasca reveals startling new perspectives on life that can result in overwhelming feelings of about 20 to 30 minutes after ingestion, and usually peak in about two hours, lasting for a total of four to six hours. Connected resonance contours. A schematic representation of the experimental setup is shown in Figure 1.

Energetic Influence of Ayahuasca

Full text PDF: Energetic Influence of Ayahuasca

Energetic Influence of Ayahuasca

See also: Ayahuasca Kirlionics Research

Read the full article

#Ayahuasca#AyahuascaCeremony#Bio-Well#Bio-Welldevice#Bio-WellSputnik#Bio-WellTechnology#DMT#EnergeticInfluence#EnergeticInfluenceofAyahuasca#GDVSputnik#HRVstudies#InfluenceofAyahuasca#KonstantinKorotkov#SputnikAntenna

0 notes

Text

What the United 3411 Incident is Really About

by Brice Ezell

If you've followed the news at all in the past week, a recap of the events of United Express flight 3411 is unnecessary. For those who limit their news intake or even avoid the news – in this political climate, not an unreasonable move as far as stress and mental health are concerned – here's a recap: 3411, a plane leaving Chicago's O'Hare Airport for a short-haul flight to Louisville, Kentucky, was overbooked the day of its departure, Sunday 9 April. Overbooking is problem enough for paying customers, but in the case of 3411 there was an additional complication. United had several employees that needed to be on the plane, as they had to work on a flight in Louisville the next day.

With the flight being overbooked, United offered to give a night's stay in a hotel plus $400 USD to any customer willing to give up their seat. When no one took that offer, United upped the offer to $800. No one was enticed by that, a clearly considerable sum that likely outweighed the cost of the original plane ticket. According to some reports, United ended up offering $1000. When no one accepted these cash incentives, United randomly selected four passengers to be removed from the plane to accommodate the United staffers that needed to be in Louisville the next day. Three left the plane, undoubtedly frustrated, but without making much of a scene. The fourth, one Dr. David Dao, a practicing physician, refused to leave on the grounds that (a) he paid for his seat and (b) he needed to be at the hospital the next day to tend to patients. Despite the reasonability of those claims, United called the airport police on Dao, who was physically yanked out of his seat and dragged off the plane, leaving him bloodied.

Since then, United has faced a hailstorm of media criticism, and with good reason. As it turns out, using state-sanctioned violence to take from someone a service he had paid for makes for bad PR. It didn't help that the official Twitter statement by Oscar Munoz, the CEO of United, sounded like it was drafted by a corporate jargon bot, like horse_ebooks attempting to give an apology. United presumably compensated Dao and the other individuals removed from the plane, and in a surprisingly classy move, the airline did later refund all passengers on the plane the price of their ticket. Yet in examining how this thoroughly terrible event came to pass, it doesn't take long to figure out that this is but a single manifestation of a much larger problem, and that United could have saved itself a lot of grief by acting sensibly.

Before getting to the crux of what 3411 represents, there is one particularly bad argument that is worth addressing right out of the gate. I've seen it crop up across social media, but one grating iteration of it appears in the post called "I Know You're Mad at United but… (Thoughts from a Pilot Life about Flight 3411)", by Angelia J. Griffin. An early paragraph in Griffin's post features this confession, "If a federal law enforcement officer asks me to exit a plane, no matter how royally pissed off I am, I’m going to do it and then seek other means of legal reimbursement. True story."

This kind of argument is popular any time there is an instance of accused (or even likely) abuse of power by a law enforcement officer. "If only that unarmed black man who wasn't doing anything wrong at all simply did exactly what the officer told him, he would still be alive today!" This mindset is a curious thing to exist in America, a country founded on rebellion from the government that’s also home to the most guns per capita by a long shot – almost one gun per American (skip to page 47 of that PDF). Thee "if an officer says, you do" mentality is a whisper away from total fascism, if not an outright capitulation to it. I know that in the era of Donald Trump it's popular to bandy the word "fascism" about the minute something bad happens, but I do not use the term lightly here.

Just so it is crystal clear: a badge and a gun do not prima facie put an officer in the right. The presence of a badge does not mean that everything an officer says or does is correct. Asserting the high standing of the law does not negate the fact that many officers of the law fail to uphold their obligations to the law, and in some cases even abuse the law. Respectfully questioning an officer, or standing your ground when you know you are within your rights, does not make you a criminal or a degenerate. It makes you a human being, one that does not let the mere presence of power take away your dignity. Griffin's tone in her piece turns her seemingly "I don't want to cause any trouble" point into something closer to, "Shut up and obey orders when you're told." I and I don't think most Americans want to live in a society where that is the default response to authority figures.

Dao was not in the wrong for insisting that he needed to tend to patients the next day. I'm willing to bet that his reason for needing to be in Louisville the was better than most of the others' on board.

While the initial response to Dao's injuries was widespread sympathy and outrage, it wasn't long before a certain disingenuous brand of argumentation reared its head in opposition to the outrage. Basically, it boils down to this: "But the rules!" United Airlines, like all airlines, has each passenger sign a contract of carriage with each ticket – though, of course, most passengers click "I accept" on this contract without ever actually reading it. One stipulation of most if not all contracts of carriage is that airlines can in fact deny boarding to paying customers, given a particular set of circumstances. This brief primer by USA Today illustrates some of the myriad reasons why one might be denied entrance to a plane even after she has bought a ticket. (The article also notes that a contract of carriage runs up to 37,000 words.)

Descriptively, the "play by the rules" argument is valuable, for it reminds airport passengers of just how much legal scaffolding exists for the process of air travel. United and the other major airline carriers have their asses covered, and the minute you cry foul, they will let you know of that. Given that most customers don't have time to parse through 37,000+ words of text every time they need to buy a plane ticket, it is good to know what stipulations come in the contract of carriage.

As a claim against Dao's sympathizers, however, the "play by the rules" argument – espoused by Griffin and many others – is nothing more than pedantry. Yes, it is true that airlines have contracts of carriage that come with certain rules. Yes, it is true that people should be better informed about these things. But the fact that rules exist isn't the substance of the matter for those angry about what happened on 3411. In the battle of Single Paying Customer versus Giant Corporate Airline With Its Army of Lawyers and Whatnot, everyone knows that the latter will always win out, even if slight concessions are granted. The outrage isn't that rules exist at all; it's that the rules set by the airlines are fundamentally unjust and result in pernicious outcomes like 3411's.

It is first of all worth noting that the "rules are rules" line of reasoning might not even exonerate United in the case of 3411. As many have already observed, there is a distinction in contracts of carriage between being denied boarding and being refused transport. The former is what the "rules are rules" crowd is leaning on: if a plane is overbooked or there are airline employees in need of transportation, it is true that passengers can be denied boarding. However, being denied transport – that is, an airline's refusal to fly a customer to his destination after she has boarded the airline – is a different situation. Were Dao denied boarding prior to getting on the plane, legally United would have been in the clear, but since Dao was violently removed from the plane having already been boarded and seated, United's legal footing is a lot less sure. There is ambiguity in the contract of carriage on the line between "denied boarding" and "refusal of transport," but in contract law, ambiguity in a contract stipulation works against whoever drafted the contract – in this case, United.

United also promised federal regulators in 2014 that all ticketed passengers were guaranteed seats, but unsurprisingly a "promise" from a large corporation without any legal apparatus behind holds as much water as the notion of Southwest Airlines being a budget carrier.

Furthermore, there is a practical consideration in the case of 3411. Given that the flight was full of paying customers and the airline did have a need to send employees to Louisville for work the next day, the easy solution would have been to rent a car for the four employees and have them drive to Louisville, a four and a half hour trip which would have put them in Louisville with time enough for sleep. Airline employee's unions do require certain standards of accommodation for employees, and considering that I am unaware of them I might be speaking out of turn here. But on the surface, at least, this solution would have met the airline's need of getting its employees to their next work location without depriving paying customers of their seats.

But suppose United was legally in the clear, and that at best Dao would get a tiny settlement in going after the airline through legal means. I'm not one to elevate late night talk show hosts as beacons of reason, Jimmy Kimmel made an excellent point in his televised remarks on 3411: in no other industry would customers tolerate the policy of overbooking. Imagine, Kimmel suggests, going to an Applebee's and after having ordered your food, you are removed for other paying customers who wanted to sit down. Applebee's would be out of business in a heartbeat. (That is, unless people really love riblets.) Yet for some reason, with airlines overbooking comes with the cost of soaring through the skies. No federal or state law prohibits overbooking.

In the first instance, it makes sense why airlines overbook flights. Air travel, even when an airline has economies of scale, is an expensive enterprise, and all airlines have the financial prerogative to ensure that every seat is filled. Any unfilled seat represents wasted space and lost revenue. Hedging on the possibility that some travelers won't make the flight for which they've bought a ticket – which given the expense of a plane ticket strikes me as a low possibility – air carriers overbook flights such that if a seat becomes empty, a passenger on the wait list can board, and the airline is then ensured of its revenue. I am thinking in the aside of that last sentence that most travelers wouldn't outright skip a flight; I am aware there are other reasons to miss flights, including the not insubstantial number of people who miss flights due to TSA security delays. However, I have yet to see compelling statistical data that shows that missed flights pose such a profit problem for airlines that the practice of overbooking becomes necessary.

It is incumbent upon airlines to prove the financial need for overbooking. Even with the practice of overbooking in place, airlines remain almost systemically unprofitable, and it is implausible that missed flights by some customers would constitute absolute financial ruin for air carriers, above and beyond the harms caused by the already problematic standard operating procedures in the industry. But logical scrutiny and good business are not correlated, so for the time being it appears that the outrage over 3411 will fizzle out in the short term, and airlines will go back to doing whatever they want in the long term because they know air travel is a necessity in a globalized business world.

The fact that airlines know that necessity has in large part enabled the industry to become anything but the free market many would like to think it is. Alex Pareene puts it directly and astutely in the title of his article “Airlines Can Treat You Like Garbage Because They are an Oligopoly.” An oligopoly (think “oligarch”) is a market controlled by a few core players, in this case the “Big Four” of commercial American aviation: American, United, Delta, and Southwest.

Central to an oligopoly is the limitation of competition, and in the aviation game, there is little of it. If you go on Kayak or any airfare aggregator like it, you’ll find that with few exceptions, most airlines stay within a predictable cost range for their flights. For example, I can fly to New York City from Austin round-trip -- if I buy well in advance -- for around $200-$250, and in most cases I can have my choice of American, United, or Delta. (As for Southwest: see my previous comment about it being definitely not cheap.) I could go to a budget airline like Spirit (or Frontier if I was heading west), but those airlines are only deceptively cheap. The budget flights on those airlines usually only exist for select airports, and even for those fares that are comparatively lower than those of the Big Four there is a well-known nickel-and-diming that occurs after the initial ticket purchase. (For reasons that remain opaque to me, it costs more on Frontier and Spirit to bring a carry-on bag -- which the major carriers don’t charge for -- than it is to check a bag.) This may seem odd on face: wouldn’t each member of the Big Four want to stake out the most competitive rates, thereby ensuring that they draw more customers?

Well, as it turns out, no. The Big Four appear quite happy with the sky oligopoly. (Skoligopoly?) As Pareene puts it,

This is called oligopoly, and, for airline shareholders, this is great! It truly is a new golden age of aviation, for people who fly in private jets but own stock in airlines. For the rest of us, this is most of why flying sucks now (the rest of it is the ever-expanding and largely incompetent security state), and also why United is not that worried about you sharing that video of a man being brutally dragged off their plane. They are not embarrassed, and you will not embarrass them. Airlines feel no need to perform the dance of corporate penitence. If you’ve chosen to fly somewhere, it’s probably because you don’t have a good alternative to flying...

What does United care if the internet is mad at it? The airlines divvied up the sky between themselves, and if you live or work in United territory, at some point you’ll face the real “choice” offered to consumers in a post-consolidation industry: flying with them, flying a more time-consuming and circuitous route with some other, probably equally horrible airline (if such a route is available), or not flying anywhere. Do you need to get from Fargo to Denver in a hurry? Congratulations, you are now a United customer.

So long as each airline can generate profit and earn regional advantage in certain places, these companies have no incentive to compete for the purpose of lowering prices. The utter hilarity of the “trickle-down” notion of profit-seeking is also illustrated by the airline oligopoly. Writing for Vox, Alex Abad-Santos points out,

Flights are still expensive, even though the cost of jet fuel, a reason commonly cited by airlines for raising prices and adding fees, has gone down — in 2016, jet fuel prices were a third of what they were in 2014, but ticket prices didn’t decrease in kind. It’s cheaper for airlines to operate now than it was a few years ago, but they haven’t passed any savings on to customers.

To boil it down to its essence: United, along with the three other members of the Big Four controls the skies. Who cares what passengers want? What power do they have against the airlines?

In response to the outrage following 3411, many in the “rules are rules” crowd also touted the classic “hit ‘em with your wallet!” line of reasoning. “If you don’t like it, don’t give your money to United! That will show them what their customers prioritize, and if enough people do it United will change its behavior.” This argument is predicated on the notion that the airline industry resembles anything like a free market, and that airlines are responsive to customer inputs in the way a market competitor theoretically would be. But since the skies are ruled by just four airlines, corporations like United don’t have to care about customers in the way a business freely competing with others would. Many have touted the heavy airline deregulation instigated under the Carter administration in the late 1970s -- prior to that, airlines were highly regulated by the government -- as an example of giving choice and lower prices to the consumer, thereby making air travel more democratic. In seeing the corporate merger-driven oligopoly that now controls the air, I cannot help but think of the classic line from the film No Country for Old Men, a question I think well applies to more than one stipulation of United’s contract of carriage: “If the rule you followed brought you to this, of what use was the rule?”

This is the heart of the matter when it comes to 3411. The anger following Dao’s horrible mistreatment is not about what the rules are, but rather why the rules are, why the airlines are in such a place that they can treat customers in this way. The airlines are able to implement policies like their overbooking practices because there is no regulation that forbids it -- or, seemingly, even tempers it -- and there is no means by which customers can hold these companies to account. This compounds the initial frustration of 3411 further: it’s not just that airlines behave in a way anathema to good customer relations, but they also have no incentive to change.

Some will instinctively backpedal at the slightest hint of regulation, suggesting that deregulation led to lower fares and greater choice for consumers when shopping for plane tickets. Given the increasingly non-competitive airline marketplace, one wonders how competition will be fostered by the status quo. But more importantly, knee-jerk anti-regulation relies on a fundamental misunderstanding of coercion. Matt Bruenig writes,

What’s amusing about libertarians and laissez-faire people (and the loose way certain economists talk) is that they will describe my choice to pay rent as non-coerced and voluntary while describing my choice to pay income taxes as coerced and involuntary. But there is no neutral construction of “coercion” that would ever support such a distinction. As [Robert] Hale aptly demonstrates, coercion occurs when there are “background constraints on the universe of socially available choices from which an individual might ‘freely’ choose.”...

...When we talk about the economy, we are not arguing about whether we want coercion. We are arguing about what coercion we’d like.

The same holds true for airlines. There will always be rules for flying on a commercial airliner, and customers should know those rules. But wanting a different set of rules isn’t tantamount to a new imposition of coercion; instead, it’s a question of how coercion ought to function in an airline-to-customer transaction. Looking at how United’s overbooking policies -- which are similar if not the same to the other contracts of carriage in the Big Four -- resulted in Dao being yanked out of his seat and bloodied in the process, I think it’s high time those rules be reconsidered. So long as things stay the same, let’s not pretend that the air is just another competitive marketplace.

In thinking on 3411 and all the follies of American capitalism it represents, I've come up with what I call the Greenspan Rule, the name of which is inspired by this classic observation of Noam Chomsky's, which he delivered in response to one of former Federal Reserve chairman Alan Greenspan’s characteristic panegyrics on the free market. The Greenspan principle is simple: if you hear a businessman, CEO, corporation, or pro-corporate politician singing the praises of the free market, you can almost be certain that the market they envision is anything but free.

Some further reading on Chomsky's response to Greenspan's claims about the virtues of the free market can be found here. See specifically the section "Saint Greenspan and the transistor."

5 notes

·

View notes