#2012 wild Rust my beloved

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

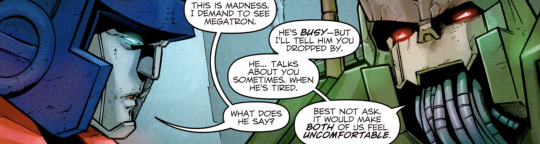

Spotlight: Orion Pax - Because Hasbro was Getting Antsy About Their Golden Boy Having Faffed Off into Space

Oho, you thought we were done with Optimus Prime, did you?

You fools.

This is Transformers- we’re legally obligated to have Optimus Prime in some form or fashion running around at all times. This is just Hasbro catching up.

Fun fact: this was published on December 12th, 2012!

Our issue opens up with Orion Pax strapped to the top of a shuttle that’s careening towards a city.

But that’s the hook, so we won’t get to see what that’s all about just yet. No, first we’ve got to see just what all led to this point.

Earlier in the day, Orion Pax got refitted with a hot new bod, courtesy of Wheeljack, and now he’s showing off his new look to historical constant Rung and Kaput, who are here to assist in acclimation.

This is Kaput’s first appearance in the comics, but it’s not his first entry into the IDW continuity. He was introduced in the Last Stand of the Wreckers prose story Bullets, where he diagnosed Ironfist with dead, in so many words. Kaput’s here currently because he specializes in sparks, and he’s going to make sure that Orion’s doesn’t explode in his chest thanks to the frame change. No word on whether the wheel was something he came into the world with or a modification.

But enough medical nonsense, let’s see the star of the show.

That’s not how reflections work!

Orion’s first point of contention is the fact that his lucky faceplate is missing. Wheeljack replaced it with a proper face, because that’s the new hotness right now. I guess when you’re a race of space robots who can change their bodies the way humans change their clothes, fashion is a lot more work. I wonder if faces out out of vogue in the present- there’s a lot of guys without one on the Lost Light.

Rung offers Orion some reading materials to help him cope with the sudden change, but it isn’t necessary. Orion fully intends to switch back to his old bod after his mission is over.

If you couldn’t tell by this point, this whole “frame change” thing is a plot contrivance to explain away some of the design clashing between comics set during this time period.

This is Zeta.

Yes, really, they’re the same guy. I don’t think Senator Shockwave would have had him modified for Matrix carrying if he’d known how tacky he was going to be about it.

Zeta Prime seems to think that haute couture is exploding a Galapagos turtle and then strapping the smoking remains to your back.

Zeta leads Orion over to where Nightbeat’s waiting with a slideshow he spent hours on. Nightbeat, at the time of this story, is a hostage negotiator, and today his mission, as well as Orion’s, is to retrieve our beloved Ratchet from a Decepticon terrorist cell hiding somewhere in the Rust Spot. The Rust Spot’s some heavy duty danger, hence the reformat for Orion.

They’ll also be bringing on Alpha Trion, #1 Rust Spot navigator, philosopher, polymath, polyglot, historian, and all-around grandpa.

His beard gets a D+, however.

Note the quotation marks on “he” here; it looks like even Roberts was sick of the Furmanism that is “genderless robots that all appear to be male”. We’ll get more into that sticky situation later on. What I want to focus on right now is our artist for the issue, Steve Kurth.

Kurth is from Wisconsin, and doesn’t have a ton of pencil credits to his name in the Transformers franchise. He mostly does work for Marvel, and while it appears his art blog hasn’t been updated in a few years, the publishing company still has a tag for him. He’s done the Avengers, if that’s your thing.

Anyway, so nobody knows who’s in the back.

I gotta say, Alpha Trion, you got some brass fucking balls to insinuate that the cops forgot to put the hostage tradeoff in the trailer, in front of said cops.

The fellas transform and roll out, Orion pulling the trailer because anything else would be blasphemy, as Alpha Trion guides them to the meet up point. As they drive, the old man regales the young whippersnappers with his tales of friendship and adventure alongside Metroplex the Titan. They were, like, best friends. Seriously.

Storytime gets interrupted however, as our heroes are attacked from beyond the mists.

You know, when I was a kid, my mom had a car that looked exactly like Nightbeat here, paint job and all.

Alpha Trion got so wrapped up in blathering away, he forgot to mention that they were in Slicer territory, and might want to be on the lookout. Thanks, Alpha, way to be a pal.

Nightbeat refers to the creatures as “throwbacks”, something that’s never elaborated on, but I’m going to guess it means something along the lines of being primitive, or perhaps animalistic.

Holy fucking shit, that’s terrifying.

These awful things start swarming Orion, Nightbeat, and Alpha Trion, who all start punching and shooting with wild abandon, making short work of the mass. Orion gets a few paper cuts for his troubles, but they’re all more or less alright.

The trailer can’t say quite the same though; the door’s popped off, and the contents have either escaped or never existed in the first place.

Schrodinger wept.

Alpha Trion pulls the prisoner out of the fog… and then so does Nightbeat.

It’s a two-for-one sale at the Hostage Emporium.

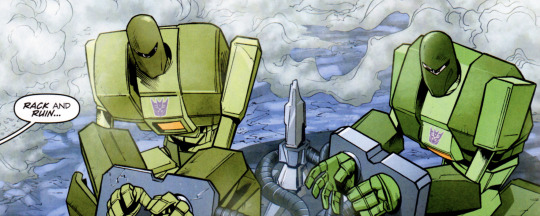

Rack and Ruin haven’t really done anything to warrant being worth a whole entire Ratchet, so Orion decides to have a little chat and see what’s up.

Oh, that’s what Nightbeat meant by Ruin being the ugly one.

Orion’s chat reveals these two chumps to be even bigger losers than they first appeared to be- their only talent seems to be instantaneous conversion, which involves shutting off all the safety protocols for one’s transformation cog for a faster switch.

Orion switches trains of thought, asking about the Decepticon cause and its whole deal. This is a bit after the events of the heist, so the rhetoric has become a bit more violent by this time, and he wants to know what the hell happened.

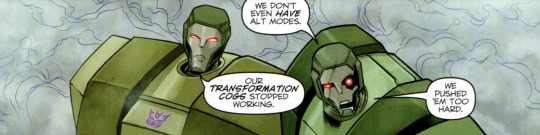

But there’s no time for philosophic musing, because that’s when the Decepticons show up. Thundercracker escorts our group to the hideout to meet Bludgeon, and the exchange is made, albeit with a pro bono thrown in.

Well, shit.

This was why the Decepticons wanted to meet in the Rust Spot; because they knew only Alpha Trion would be able to guide the cops to the tradeoff point. But what are they going to do with robot grandpa? Why, use him to find Metroplex, of course!

There’s a rumor that Titans have the capabilities to create space bridges inside them- we as the reader know this to be true thanks to the 2012 MTMTE Annual, but let’s not tell Bludgeon about all that, yes?

Orion, please, this is hardly the time.

Luckily for Alpha Trion, Orion stuffed some guns into the bottom of the trailer, as is made apparent when he starts throwing them to his buddies. Why he and Nightbeat weren’t carrying any weapons on their person isn’t addressed, but at least the idea here is kind of cool.

Alpha Trion easily escapes his bonds, because a noose isn’t really worth much to a species that doesn’t breathe and can literally survive not having a head.

We are just laying it on THICK today, aren’t we?

Rack and Ruin lead the other not-Decepticons into the tunnels towards safety- not sure how exactly, considering they’ve got their sensory deprivation helmets back on- as Orion Pax is dogpiled into submission.

Bludgeon might need a hobby. Might I suggest jigsaw puzzles?

Orion’s about to hit the loop that was created by the first page of this issue, so he tries to stall for time to think of a way out of all this. He halfway succeeds, in that he gets a little more time, but doesn’t come up with anything. Down on the ground, all his friends watch the shuttle shoot into the sky, probably wondering what all that’s about.

Bludgeon was aiming for this shuttle to hit a populated area, but it would appear that he’s an idiot and overshot by a wide margin. Cool beans.

Ah wait, we still have another three pages of story to this.

Hey, y’all remember Hoist’s tragic backstory, where he wandered the Rust Spot alone until he almost died of exhaustion?

Yeah, that was Orion’s fault.

The Fault of Our Star, if you will.

(I’ve never read anything written by John Green, what the hell am I doing?)

Because he just bounced off the underside of Hoist’s shuttlecraft, Orion’s hurtling towards the downtown section of Iacon, which is absolutely a populated area and exactly what Bludgeon was going for. Orion’s going to have to think fast if he’s going to get out of this one. Good thing Rack and Ruin told him their super secret transformation technique.

Thinking quickly, Orion transforms into a truck, breaks his bonds, somehow manages to not fly off the side of the shuttle due to wind pressure, transforms back to root mode, shuts off the autopilot, slams into a wide open field just outside of town, and survives well enough to be more concerned about Wheeljack being mad he scuffed up his new body than his own safety. Good on you, Orion! You saved the day!

To celebrate, he takes an old hubcap or something and shoves it over his face, because I guess only he gets to know how he’s feeling.

Don’t look at me like that, it’s not my fault the story just kind of ends here.

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

KELLY REICHARDT’S ‘WENDY AND LUCY’

© 2018 by James Clark

The truest way to the heart of Kelly Reichardt’s film, Wendy and Lucy (2008), may turn out to be its penultimate moment. This was not always my approach, as a reading of the Wonders in the Dark blog from February 15, 2012—A Dangerous Devotion: Lars von Trier’s “Dancer in the Dark” and Kelly Reichardt’s “Wendy and Lucy”—would show. There I was intent upon engaging the protagonists of each work having risked everything (like Joan of Arc) for the sake of getting to the bottom of a dilemma unfortunately even beyond their very alert and brave powers. What, specifically, drives such souls to the brink of destruction?

There are ways of taking a closer look at the phenomenon, and Wendy and Lucyshows the way. Like Mouchette, a classic film figure under heavy fire, Wendy can no longer stand her emotionally violent, Midwestern blue-collar family and neighbors and their Rust Belt home base spanning Muncie and Fort Wayne, Indiana. Unlike Mouchette, the famous waif, she does not choose suicide as a meaningful change (nor is she destined to be immortalized by a forum of movie buffs). She hits the road with 500 dollars in savings from unspecified jobs, and a clunker supposedly capable of reaching that land of fool’s gold, Alaska. (Where others dream of gold, she—speaking volumes—dreams of a job in a cannery which, at least, does not resemble Indiana.) However, she does also bring a stunningly vast fortune in the form of her golden retriever, Lucy (a born retriever of buried treasures).

Right from the get-go we know Wendy will precipitate some kind of screw-up. Getting to that late and primary revelation mentioned above, there is Lucy in the back yard of a suburban Portland, Oregon, home, having become a foster-home for her as the upshot of Wendy’s jail time for shoplifting. (Perhaps before beginning with that end of their era together, in that tranquil yard, we should notice that, in the course of Wendy’s return to freedom she distributes posters including a photo, around the area where Lucy was last seen. “I’m lost!” the tag-line runs. When Mouchette is confronted in a forest by a figure suspicious about her intent, she defends herself by blurting out, “Lost, Sir! Lost!” The truly lost, Wendy, having found where her beloved had landed, proceeds there to confirm her incurable lostness. (And Lucy proceeds to confirm her genius.) The subversion of mainstream sentimental film reunions here is an important gift.

Wendy first sees Lucy gazing at a flock of seagulls circling her new and possibly very short-term yard. Calling out to her and saying, “You miss me, Lu?” Wendy passionately clings to the chain-link fence. Lucy forgets the seagulls and rushes to the only familiar aspect of a life having undergone a shock we never fully see, this being a remarkable hallmark of Reichardt’s narratives. “I’m sorry, Lu,” is a recognition that Wendy sees her friend as having smashed out the cliché ceiling where jerks come up smelling of roses in the hands of infinite forgiveness. “I know… I know, Lu” the wanderer emotes. But does she in fact comprehend that when, at the entrance of the grocery store she was about to rip off (after not entirely sincere calming kisses and caresses), Lucy could read her friend’s being a disappointment as spiked by, after Lucy’s desperate barking a warning, undergoing Wendy’s marching up to the leashed-secured companion, clamping down her snout and angrily telling her, “Don’t be a nuisance! I don’t need that?”

The beginning of Lucy’s painful realization that she doesn’t need the felon includes the frenzy on seeing her partner brought back to the store by a clerk and then taken away in a squad car (all the more disturbing in never seeing the back-door departure while left to puzzled and desperate staring at the front door). However, the generally supposed-to-be dull-one’s real struggle is left for us to reconstruct. As now newly composed, Lucy listens to Wendy’s solicitude and her heart is both joyous and something else, very hard to undergo. “Don’t be mad, Lu… Here, I got you this!” [a stick, to fetch]. She throws it toward where the seagulls were. “Such a good catch! Drop it! Good dog! Good girl!” Lu happily plays, with old-time and not old-time energy. (Lucy’s flagging and once prominent lodestar [with funds having dwindled by way of the shoplifting fine, the car disposal and a theft/ assault in the woods] had become a lachrymose spent force like Mouchette; while Lucy had become a form of another cinema figure—unforgettable to a choice clientele—namely, Baltazar, the donkey, carelessly regarded as “The Mathematical Donkey.”) “I’m sorry, Lu,” is followed with a defeated cry. “I lost the car…” comes next, followed by the rather hasty, wishful thought, “That man seems very nice…” Suddenly it’s, “You be good… I’m gonna make some money, and I’ll be back! OK, Lu, be good…”

How good Lucy could be in face of that collapse requires inference about how she weathered the abandonment. After Wendy’s release, she looks for Lucy at the pound. Though she comes up empty, we can imagine her dog going through the fear and depression seen in all the inmates on hand. We can imagine Lucy’s sense of being ripped away from not only a person of great interest but the infrastructure by which they had been sustained. Missing the interpersonal love intrinsic to that stemming would not be the end of Lucy’s heavy reflections. The moment of their kiss and caress through the fence out in the suburbs, fathoming how much is left and how much is gone, offers a wider range of action whereby other entities (seagulls, for instance; and the sea itself) offer creative love more resilient than that of Wendy.

From that perspective, accessible only to those who, with passions unstinting, beat back lostness, Wendy’s way of concluding the interplay is far more breathtaking and chilling than any gun battle. The intensity of this kinship should not be allowed to filter down as a sentimental highlight of melodramatic, advantage-addicted presences bending to the dubious powers of physics, religion and morality. Wendy, by and large, seems common and flighty. But, as we are about to investigate and define, her awkwardness and suspicion (and responsiveness to generosity) stem from an aristocratic spell. She does not cherish many others of her species for the very good reason –but too bluntly rendered—that they are far more remote from her energies than Lucy.

In the subsequent Reichardt film, Meek’s Cutoff (2010), Emily (played by actress, Michelle Williams, who also puts Wendy on the map) sees her real world shrink to one American Indian heading for the hills without her. She had considerably come to the point of being enraptured, from which to chart a difficult and seldom seen course. Here it is Lucy who sustains what Emily is about to undergo, while Wendy more closely approximates Emily’s game but uninspired husband, Solomon. While Wendy was spinning her wheels to little effect, Lucy was bringing lucidity to the matter, lucidity in the sense that effective love requires effective hate. That shocker, in the context of a sweet pup, requires incisive explanation. Creatures great and small, as our film makes efforts to highlight, find themselves intent upon many objectives. But their most remarkable action, namely, participating along with creativity itself (mustering the energy to complete its presence) is not widely accomplished among humankind. Wild creatures, including pets more fluent with carnality and its paradoxes, put together far better numbers of this sort. Though much of the world’s humans hunker down in finalities seeming to them consummate, from the perspective of that other way (being about kinetic coordination, rather than a stand) there comes to pass a state of impasse massively hindering forward momentum. By the same token, wild creatures (including some humans) feel at war; but also—through agencies of daring and reflection—a kind of peace. As the reservoir of coming to grips with impasse veers to more sanguine areas, there is the possibility of oscillating overtures amongst the options, especially in the syntheses of blithe percolation, increasingly putting heat on the opposition by attractive ways careening (like happy wolves) as part of a delicate wolf pack. Thereby, the problematicness of such a pragmatic inertia, never to be dislodged, can paradoxically flourish in ways integral to a cogent primordiality.

The power of the scene where Lucy and Wendy go their separate ways derives from that unique, compelling infrastructure. Such a smash-up, between those who have travelled where so many haven’t, elicits a post-mortem (where no one has actually died) for the sake of casting light upon a skill with consequences far beyond domestic viability. When it comes to breathing down Wendy’s neck to discern what’s the matter, we can begin by availing ourselves of Reichardt’s previous film, Old Joy (2006), where a couple of incompatible guys waste the beauties of rural Oregon and spend a bonfire night worsening their intrinsic depressiveness. In the course of Wendy’s joyless playing fetch-a-stick with Lucy where we first see them along a forested path in Oregon, the retriever stumbles upon a tribe of runaways spending the night around a bonfire. Actor, Will Oldham, who, in Old Joy, joylessly goes through the motions of play with the dog of the hour—Lucy, in fact—comes back to haunt Wendy and Lucy as once again a nocturnal presence proud of making a statement against those who work with a will. A (strategically significant) responder to Lucy’s neglect—an unwashed young girl with a large ring through one nostril and looking more affectionate than Wendy—readily becomes the leading light, eclipsing the loudmouth (Icky), though another boy, weighted down with a sense of his own errancy, also outperforms the medicine man. Wendy eventually comes into the picture, a picture of wanting to be somewhere else. She—a mixture of shyness and mistrust—divulges her travel plan, which prompts Lucy’s new friend to call out, “Hey. Icky, this lady’s going to Alaska!” That sets off Wendy’s having to hear the know-it-all recommend a company to work for (later we see her jotting down the particulars), without any recognition that she has anything in common with him. Increasing the alienation is Icky’s follow-up boasting about totaling a two-hundred-thousand-dollar earth mover there, when stoned, of course (Oldham’s playing the part of a stoner, in Old Joy). “They couldn’t pin it on me… I was gone!”) Her rather brittle body language here is a case of being all to the good and yet all to the bad. Before Lucy rushes ahead to that intriguing underworld, there is a play of twilight in the trees, smudges of vivid color—forming a dynamic incentive leaving Wendy far behind.

Following directly upon that wake-up call where a bonfire has a hard time priming Icky and Wendy toward some semblance of viability, there is Wendy’s parking her car on a quiet street; and a blurry pink figure, due to car and house lights springs, up by her window. “Sleep, girl,” she tells Lucy; but wakening is the keyword. Next morning our protagonists are wakened by a security officer, who informs her, “You can’t sleep here, Ma’am…” Almost simultaneously, a pigeon flashes skyward by that same window touched the night before. Its joining the patterns of exhortation constitutes a final bon voyage before Wendy’s limitations take over.

Her malaise and hard eyes in spying at the periphery of Icky’s campsite, before joining Lucy being treated well, bespeak more fear than alertness. The prompt death of her car (an Accord, of all things) while being told by the officer to move it sends her into an anxiety attack hardening into crude defensiveness. That same morning of ignition not happening brings the revelation that Lucy’s food bag contains 10 small kibbles. Rather than dip into her puny war chest to care for her partner, we have Lucy on a tight leash and Wendy scavenging for bottles and cans (an occupation of Oldham’s Kurt, in Old Joy). In their constriction (Lucy on the lookout for anything edible on the ground), Wendy ties her friend to a fixture at a strip mall while she goes off to a public washroom. She brushes her teeth, gives herself a sponge bath (attending to an injury at her Achilles heel) and fills a bottle with water; but Lucy does not become a beneficiary of that exercise, exposing how patently hopeless the master of rugged and woozy individualism amounts to. On the other hand, with the lady going to Alaska chewing on some nondescript scrap and Lucy at a loss to find even a scrap, their peril, pain and stoicism disclose that this is no mere folly but an enduring and profound love, however disastrous.

The dead car having changed a rout into a massacre, Wendy attempts to shoplift a can of I AMS (and sundry snacks), and the young stock boy who intercepts her proves to be an instance of all she hates and carelessly hopes to hide from. (The shoplifting scene in Greta Gerwig’s film, Lady Bird [2017], where two young check-out girls regard the effort as a laughable farce, seems to be more Icky than Wendy—a somewhat inadvertent underlining of how uniquely pitched our film has been composed.) The clerk may be a schoolboy part-timer, but his rhetorical apparatus, as fortified by a crucifix, comes to us as redolent of a fanatical opportunism able to override the far more rounded and easy-going manager. So well on top of her subject, Reichardt endows the moralist with a voice recalling smug Eddy in Leave It to Beaver; and also Kurt in Old Joy and Icky in our film today. Not leaving the experience with that, she shows us that Wendy herself has little trouble slipping into that murder-inciting register. “Excuse me, Ma’am? I think you’re forgetting something…” More an Inquisition than a secular mishap, Andy, the born cop, impressively hounds his boss, Mr. Hunt, who had begun with the modulated outlook, “OK, well, what are we talking about here?” Having nothing to do with grey zones, the upstanding choir boy invokes an egalitarian axiom being hard to deny. “The rules apply to everyone equally.” With the can of I Ams on the desk as Exhibit A, the clean-up drive puts forward another indubitable truth, “If a person can’t afford dog food, they shouldn’t have a dog.” Wendy, who had only too quickly put out the fabrication that she was intending to pay for the loot after checking on how her dog, tied outside, was doing (far worse, in fact, than Wendy was able to comprehend), expertly directs her smarts and phony sincerity to the generous motives of Mr. Hunt. “I’m very sorry… This isn’t going to happen again…” (The frenzy, despair and hopelessness of Lucy, on seeing her being ushered back in, comprising what we can imagine to be far from a unique error.) Andy presses on, with, “The food is not the issue. It’s about setting an example, right?” Wendy’s being as annoying a sophist as Andy kills any hope she might have had. “I’m not from around her, so I couldn’t be an example…” This brings Hunt to say, “We have a policy, Ma’am.”

Film stories about troubled humans and their dogs seem to invite the clientele to an evening of strong feelings everyone can easily appreciate. Wendy and Lucyis a film far from easy to fathom. In their first walk seen together, after a rather routine fetch-and-drop ramble, Lucy upgrades to that remarkably rough-hewn young girl who, when Wendy finally catches up, tells her, “Great dog!” [greatness being measured not by looks but by another kind of presence]. Learning of her name, the nomad declares happily, “You’re a sweetheart, Lucy!” What she sees, even if she can’t begin to explain it, is depth. She asks Wendy about Lucy’s breed, not as if it matters. The question catches the owner only half-listening, “I don’t know… a mix of hunting dog and retriever…” That verbal fumble becomes one of a series of sloppy assertions in Reichardt’s films, exposing the speaker as lacking articulative grip but unable to admit any shortfall in mastery within a troubling preoccupation. (Propped upon that bemusing skid, there is the nearly magical dialectic of hunt and retrieve, the “greatness” of which Wendy misplays and Lucy embraces.) Another form of elegant and ironic composition comes our way here in the form of a reprise of hugging Lucy, this time by Wendy. On realizing that collecting empty drink containers is not going to fit the bill, Wendy, outside the grocery store, performs a preamble to theft she has repeated frequently. She, too, caresses Lucy, and Lucy, as with the person the night before not having any ulterior motives, licks her face, always having been on the lookout for Wendy being as heartfelt as herself. Why would the supposedly advanced discernment need to prepare the lower form toward passivity, unless the latter has been treated to Wendy’s dark side, again and again? (Here, once again, the Shirley Temple, Depression Era concomitants of this duo lead first only to the shattered, for the sake of harder and deeper gifts.) “Don’t bother anyone, OK?” is the remarkably cynical patter on account of providing for her dear one’s breakfast. Lucy begins to wail and swish her tail fiercely in a vain gesture to make the coming outrage devolve to some kind of creative lift. Wendy turns back in anger and scolds, “What did I say?” She clamps Lucy’s snout and we wonder at the crude hysteria by which she would suppose to attain to innovative distinction.

After paying the $50 fine, Wendy returns to the scene of the crime and the scene of the end of her partnership. The bus that drives her there (a conduit of freedom) contains an ad which runs, “It’s not too late to sleep like a baby.” That seems the right time to attend to the sizeable unemployment and poverty constituency at that moment of truth. Having scandalized so many other expectations, this film is very apt to transcend political and moral bromides. All the scavengers flocking about the bottle returns depot are unfailingly gracious. When Wendy, seeing fit to retire from that trade after an hour or so, contributes to the cache of a man in a wheelchair, he describes her generosity as “cool.” Right from that first walk, ending with Icky and associates having more in common with the scavengers than marauders, a murmuring, lullaby motif of a woman’s voice wafts over moments of promise. Accordingly, it comes to light during the first moments of her bottles pick-ups. Its maintaining a sensuous balance, where imbalance so overtly threatens, combines with Lucy’s vigorous command of emotions (and capacity to be still) to expose sleeping-like-a-baby inertia as decadence, not accomplishment. Wendy, for all her gross incompetence, has had the drive to leave Rust Belt Fort Wayne. But choosing an extravagant (“cool”) destination she clearly cannot afford, from the points of view of money and maturity, leaves her floundering in distraction and melancholy similar to the casualties of the defunct saw mill which pushed a modicum of self-confidence to the total loss of such a state. (There is a startling and thrilling cinematic delivery apropos of this vale of anxiety. The district repair shop is closed for Sunday and a dispirited Wendy cups her hands to the shop’s window to see its interior free of reflection. In Mark Romanek’s Never Let Me Go [2010]—where a “Miss Lucy” is fired from her teaching job for siding with school children having been being bred for body parts—the schoolgirl protagonist and her friends cup their hands to a travel bureau window in order to ascertain that an employee within is the mother [the “origin”] of the doomed protagonist.)

Two other fixtures of that Portland exurb are the grandfatherly Walgrens parking lot minder who is mindful of Wendy; and a demented, self-pitying and rather far-seeing thief who steals about half of her meagre liquid assets. The man who said a mouthful when he said, “You can’t sleep here, Ma’am,” does in fact demonstrate alertness to Wendy’s predicament and that of those meek undead. Though he never deals with Lucy, the parking monitor functions in this distressed-dog movie the way Edmund Gwenn calms the maelstrom in Lassie Come Home (1943). Here, once again, good-will folk wisdom and cliched expectation in the foreground are no match for that nature in the background which Reichardt knows to be paramount. In response to Wendy’s counting on the local pound to eventually produce a Lucy Come Home, the Gwenn figure recommends the more active strategy (seemingly proven in his family history) of leaving on the ground items of her clothing to induce the missing loved-one to the happy fate befalling Lassie. Her departure from him includes his gift of a few dollars, all he can spare on a minimum wage salary, while making sure his granddaughter (having a body language in league with Andy) doesn’t see what is transpiring. (Just before that, we found Wendy angrily stalking about, demanding Lucy to appear and stop spoiling her excellent life. She catches up with Andy, being picked up by his mother after work, and punk-style, howls, “Have a great night, OK? Your son’s a real hero! [“Lucy! Come now!”].) A sweetheart, like Gwenn; but careful not to disrupt mainstream family priorities. Gwenn’s independence as a tinker provides food for thought. Waiting for news of Lucy, Wendy—perhaps feeling the need to do justice to the greenery she has denied herself—thinks to spend a night in the forest nearby the train tracks, where a golden patch of foliage only slightly steadies her. But her bid for bracing solitude exposes her to, like so many other of her overtures, a down side of the open road. The soporific aura of that hard-luck, wrong-side-of-the-tracks constituency seems to confirm her assumption that risk inheres in a field readily and quite pleasantly consumed. With her elderly friend (spending numbing days standing on the dead cement, and counting it a great improvement over his previous all-night job), she hears him declare, “It’s all fixed!” [needing a job to find a job]. “That’s why I’m going!” [to another type of numbing]. Suddenly highlighting the meaning of true risk is a predator who tells her, “Don’t look at me!” as he loots that portion of her money she hasn’t kept in her money-belt. The real plus of this episode consists in the sociopath very closely seeing-eye-to-eye with Wendy. “I don’t like this place… It’s the fuckin’ people that bother me… I’m out here trying to be a good boy, but they don’t want to let me… They treat me like having no rights… They can smell the fear… Fuck! I killed more than 700,000 people with my bare hands! Fuck if I know!”

“They can smell the fear,” is a brief sentence presiding over many horrific missteps. (Lucy can smell the fear.) In the aftermath of the car trouble, Wendy calls back to Indiana and her sister and her sister’s husband, on the vague supposition they might be interested in her troubled life to date. The far more sanguine husband picks up the call and kindly listens about the end of the vehicle. “It’s kinda bad here, actually…” “What does she want us to do about that?” the sister loudly asks, being like one of those the invader imagines killing with his bare hands. Wendy comes back with, “I don’t want anything,” [from the likes of you]. But countenancing the likes of her—and him—makes, as Lucy knows, more sense than going to Alaska. As with the complaining mugger and the whole town, it seems (and maybe the whole planet), vividly addressing sleeping babies seems to be a forgotten, or perhaps never found, skill. (Andy’s rabidity being merely a variant of falling prey to a gigantic creative exigency no one wants to pay the cost of.)

Lucy, on the other hand, has shown us what succeeding-to-thrive looks like. (A recent Time magazine expose, of the very smart and the very workaholic hogging material wealth, prescribes ways of letting others in on that rational advantage binge. That would be way down the track where Lucy thrives.) Wendy hops a freight going North, and as she slouches on the floor with a scowl on her face she looks out at the countless conifers (the most primordial trees), pulled along like toffee, into a mysterious weave by the speeding train. Lucy, too, is carried along, by the vicissitudes of foster care. Wendy is crushed by the countless obstacles. Lucy, by her own lights, knows of a fluid, mysterious range she is acute enough to recognize as being her real home. Lucy Come Home.

0 notes

Text

Shaun Johnston is back onstage in Annapurna at Shadow

You can always tell when Shaun Johnston is in a theatre. Yes, there’s his beloved Chevy pick-up (c. 1990) outside the Varscona, a four-inch layer of snow on the cab. In a world of constant flux and starry oneupmanship, there’s something highly consoling about this.

The effect is enhanced when you catch sight of a mysterious round red machine in the cargo bed. It’s the same one you asked Johnston about last time he went AWOL from TV-land to be onstage here, four years ago. After all, you never know when someone might need an air compressor, as he points out.

There’s one upgrade to this image of constancy. “OK, I’m not in love with those, but…” says the man himself, affable as ever, apologetically pointing out rust concealer thingies around the fenders. Johnson, incidentally, remains the only actor of my acquaintance who habitually moves through the world with a tire gauge in his shirt pocket. After all, you never know….

“I know where everything is! And I use it all!”

Johnston has brought his lanky frame back from television — where he’s the salty patriarch Jack Bartlett in the long-running CBC series Heartland — in honour of the 25th anniversary season of the theatre company he co-founded with U of A theatre school mate John Hudson.

Johnston’s Shadow Theatre homecoming this time is Annapurna, a two-hander relationship reunion/mystery of the ignitable type by well-known American playwright Sharr White. In Hudson’s production, opening Thursday at the Varscona, Johnston is a cowboy-poet living a ragged, much-reduced sort of life in a crumbling trailer in the Colorado wilds. Shadow leading lady Coralie Cairns is the wife the wife he hasn’t seen since she walked out on him in the middle of the night 20 years ago.

How has she tracked him down? And why? The exchanges are acrimoniously witty. “All’s fair,” says the actor. “There are no Geneva Convention rules in this relationship.”

“It’ll be a shocker when the lights come up!” grins Johnston, who’s just startled the baristas into conversation by trying to pay for a a couple of coffees with a hundred dollar bill.

In his time Johnston has played a succession of striding cowboy heroes, deviants, miscreants, psycho killers, sheriffs, good ol’ boys, first in theatre and then mostly film and TV. The last time he was onstage here, Johnston was the grizzled Old Man drinking Jim Beam in Shadow’s 2012 revival of Sam Shepard’s Fool For Love, the same scorcher in which he’d played the restless rancher/visionary Eddie in 1982. And there’s something about Shepard’s laconic visceral style that suits Johnston to a T.

This time, an actor who looks born to wear jeans and boots, on whom cowboy hats do not look like an affection, will be wearing … an apron. Only an apron — if you don’t count the oxygen tank in a backpack. “Well, that’s a new experience for everyone,” he laughs amiably. “Don’t sit in the front row.”

“This show’s a freight train, two hands on deck the whole time,” he says, cheerfully mixing his transportation metaphors. “I do love the dialogue, the ‘cowboy-poet’ (designation). But it goes way beyond that. My character is a smart guy, a highly educated, highly intelligent person. But he hasn’t let that academic strain affect the truth of who he is….”

“I’m using Shaun’s voice, Shaun’s dialect,” he says of his take on Ulysses, the surprisingly erudite cowboy-poet who has somehow — in one of the play’s mysteries — been reduced to terminal squalor. “Not some cowboy extravaganza.”

Shaun’s “dialect,” incidentally, is the idiom of the Ponoka jock farm kid who came to theatre improbably, and late at that at 26, via working on the rigs, freelance trucking, and every other kind of construction job. It is entirely likely that he was the only actor in his theatre school class who might plausibly say of his younger self that “I could have plumbed your house. And welded your railing too.”

Life experience was his strong suit. When the drama department auditioning team asked “do you have any questions for us?” he was probably the only hopeful who stepped up: “So, do I get in?” He’s amused by his memory of theatre luminary Tom Peacocke, now professor emeritus, saying briskly, with a smile, “You’re the one! Every group has a bad one!”

Back to Annapurna, named for a Himalayan peak of formidable challenges for climbers. “I bite at Coralie’s character,” says Johnston of Ulysses. “Each of them holds a card. Or each one thinks the other one does. And they take a lot of shots to see if they can catch a look at the card…. It has the momentum of a thriller, without being one. As well as the emotions of life and love.”

“I knew I’d love it; John picked it,” Johnston says of his Shadow co-founding father. “He knows me as well as any theatre and film pro in the business…. My affection for John has remained the same from the get-go,” he says of the Shadow-y origins of the company. Its official history starts with the 1992 premiere of Johnston’s own Catching The Train, a gritty drug-fuelled tale (with live rock band) inspired by growing up in the mean streets of Edmonton.

“We founded Shadow together, but it was John’s conception. And it was simply this: if you do good theatre people will come.”

Ironically, Annapurna brings Johnston back to Edmonton precisely at the moment he doesn’t have a place to stay in his home town. He and Sue, his wife of three decades, have always lived in Edmonton with their two boys even though Johnston spent much time doing TV and movies in Vancouver or Calgary (where Heartland shoots). Until now.

They’ve just sold their place here, and bought one in Kelowna. Why Kelowna? “It was where we had our honeymoon, and it kinda grabbed me,” says Johnston. “I didn’t have enough money for Paris or Hawaii,” he grins. “I had to hawk my camera to buy a wedding ring.”

He credits “my entire career to Sue. She’s the reason I stayed with it, the reason I was able to succeed in my craft.”

That craft of acting “is the same on film as onstage, of course,” Johnston says. “You have to inhabit a character, and keep relationships real.” But in comparison to the 7 1/2 day shoots per episode of Heartland, for example, “theatre is all-consuming. You rehearse all day for weeks; at night you do your homework….”

Ah, except for the 7 a.m. pick-up hockey games he plays every Wednesday and Friday he’s in Edmonton.

What he likes about Annapurna is the relationship that is gradually revealed in the course of the play: “the efforts of two people to solve the mysteries of love…. I’m a dad. I know what it’s like to love so deeply you’d be willing to die for someone.”

PREVIEW

Annapurna

Theatre: Shadow

Written by: Sharr White

Directed by: John Hudson

Starring: Coralie Cairns, Shaun Johnston

Where: Varscona Theatre, 10329 83 Ave.

Running: Thursday through Feb. 5

Tickets: 780-434-5564 or TIX on the Square (780-420-1757, tixonthesquare.ca)

Source

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Neil Young: Trans

It’s the end of the world. The sky is an ominous shade of red, and the air is thick with poisonous fumes. Some people are silhouetted with an eerie glow while others are dying of radiation poisoning. “It shoulda been me that died,” Neil Young says, riding a bike alongside actor Russ Tamblyn. Tamblyn shrugs him off, and the two make plans for the evening. Tomorrow may never come, but tonight they’ll take their dates to the drive-in, where Tamblyn begs Neil not to play his ukulele or to sing “in that high squeaky voice.” So goes the opening scene of the 1982 film Human Highway, an apocalyptic comedy written and directed by Neil Young under his long-standing nom de plume Bernard Shakey. It’s a muddled and paranoid work, filled with forced slapstick humor and wild jams with Devo. In one scene, the members of the Ohio new wave group haul toxic waste in a flatbed truck down a lonesome highway. “I don’t know what’s going on in the world today,” Devo’s Booji Boy says to himself as images of skulls flash across his bandmates’ faces, “People don’t seem to care about their fellow man.”

This is where Neil Young’s head was at the top of the ’80s. Human Highway—Young’s third picture, following the psychedelic Journey Through the Past and his quasi-concert film Rust Never Sleeps—shares a title with a song from 1978’s Comes a Time. “Take my head, and change my mind,” he sang in its chorus, “How could people get so unkind?.” With its gentle acoustic guitars and fantasies of misty mountains, “Human Highway” plays like a eulogy to a specific type of Neil Young song. The Canadian hippie who sings in a high squeaky voice about packin’ it in and buyin’ a pick-up is only one side of Young. In fact, a decade into his solo career, Neil Young had developed a reputation more like an actor, someone remembered more for the parts he played than the unifying presence behind them all. After Comes a Time, he stepped away from his role as a ’70s folk singer, with 1979’s Rust Never Sleeps introducing a decade of restless exploration. The world was getting meaner, and Neil Young was tired of being typecast as merely an observer: He wanted to take part in the madness.

Although they both speak to the increasingly uneasy state of Young’s mind, “Human Highway,” the song, never appears in Human Highway, the film. Instead, the movie is mostly soundtracked by a record called Trans, released that same year. In the film, Young gets into character by contorting his face, wearing a pair of dorky glasses, and slapping motor oil on his cheeks. On Trans, he transforms himself by setting his songs in a distant future and filtering his voice through a variety of synthesizers, most notably (and infamously) a vocoder. The warped new wave of Trans suits the movie’s otherworldly (if endearingly chintzy) backdrops. You believe that this is the music that would play in the film’s shoddy roadside diner, where Dennis Hopper cooks sausage patties and swats at radioactive, laser-pointer flies. In fact, the movie might be the best context to hear Trans—an album that’s often treated more like a symbol (for artistic reinvention, for failed experimentation, for creative self-sabotage) than an actual entry in a body of work characterized by prolificacy and versatility.

Part of what makes Neil Young’s discography so rewarding for new listeners is that it’s filled with great entry points: the classic rock radio staples with more depth than you imagined (After the Goldrush, Harvest); the intimate passages that, even after all these years, feel like uncovered secrets (Tonight’s the Night, On the Beach); and the bizarre left-turns like Trans that inspire cult fandom just for existing. And while Trans sits comfortably along with Lou Reed’s Metal Machine Music and Bob Dylan’s Self Portrait in a lineage of puzzling-if-fascinating failures, its mythology is only part of the appeal. Reed and Dylan always felt like provocateurs—for Dylan, even finding Jesus felt like a means of snapping back at critics. But Young’s transformations have always felt less divisive, more natural and earnest and instinctual. Even when he followed Trans with Everybody’s Rockin’, a slight collection of anti-capitalist rockabilly songs, he held the latter record in high esteem: “As good as Tonight's The Night, as far as I'm concerned,” he’s said.

Young has made similar claims about Trans. “This is one of my favorites,” he said grimly, holding the album art to the camera during a 2012 interview, “If you listen to this now, it makes a lot more sense than it did then.” Even if Trans is still confusing, it’s a point well taken. In the context of Young’s discography—rich with remakes and sequels, major reunions and minor pet projects—Trans has only grown more triumphant and singular as it’s aged. He would do new wave again, he’d mess with his voice some more, and he’d even return to the idea of full-on concept albums. But he would never make anything quite so conceptually confrontational—a challenge to even his most ardent followers’ understanding of what a Neil Young album sounds like. “If I build something up, I have to systematically tear it right down,” he’s said, referring to his penchant for moving quickly from one project to another, carrying with him few traces of the previous work. It’s remarkable, then, that Trans—an album ostensibly designed to “tear down” a specific image of Neil Young—ends up standing for exactly what’s great about him.

Like so many of Neil Young’s albums, Trans is filled with mysteries and unanswered questions (Why is his 1967 Buffalo Springfield song “Mr. Soul” on here? Why is a track called “If You Got Love” listed in the lyric sheet but not on the actual album?) It’s hard to think of an artist with as many classic albums who has wrestled so constantly against the medium: even his canonized work has a raw, unfinished quality to it. “If anything is wrong, then it’s down to the mixing,” he’s said about Trans, “We had a lot of technical problems on that record.” Fittingly, much of Trans concerns man’s fight against technology. A song called “Computer Cowboy (aka Syscrusher)” details a team of rogue computers robbing a bank, with Young’s voice zapped down to a digital squelch. In “We R in Control,” a choir of robots lists the aspects of daily life—traffic lights, the FBI, even the flow of air—in which humans no longer have a say. Thematically, these songs—with their dystopian images of a world run by screens and numbers, where humans have everything at their fingertips but remain unhappy—have aged pretty well.

It’s the sound of the record that makes it more of an ’80s relic. No matter what format you listen to the album on (and it’s still never been released on CD in the U.S.), you feel as though you’re hearing it from the tape deck of a passing car. Even with longtime collaborators like producer David Briggs, guitarist Ben Keith, and drummer Ralph Molina, these songs sound very little like Young’s timeless ’70s work. The goofier, beat-centric tracks from his previous release, 1981’s shaky Re-ac-tor, certainly set a precedent. But despite its reputation for being aggressive and inscrutable, Trans is, at its heart, a pop record. It’s filled with hooks and beats and synths informed equally by krautrock and MTV. In “Sample and Hold,” guitarist Nils Lofgren—whose solos added an element of bluesy desperation to Tonight’s the Night but would soon light up football stadiums on Bruce Springsteen’s Born in the U.S.A. tour—points to future hits like Dire Straits’ “Money for Nothing” and Oingo Boingo’s “Weird Science.” When the Trans Band played “Sample and Hold” during the album’s comically over-the-top tour—an endeavor that Young claims in Jimmy McDonough's authorized biography Shakey lost him $750,000 (“And we sold out every show,” he adds)—Neil and Nils stalk the stage with rock star charisma, trading solos and bleating into their talkboxes. In the sweet, melodic “Transformer Man,” Neil’s vocoder actually adds an element of purity to his voice, as layers of wordless choruses shower him. Listening to these songs, it’s not impossible to imagine that Trans could have maybe, possibly, in another world, been a pop hit.

But that world is in a galaxy far from this one. While the critical reception to Trans was not nearly as harsh as legend would have you think (Rolling Stone compared it to Bowie’s Berlin Trilogy; Robert Christgau gave it a higher mark than Harvest), it was a commercial dud—a rough start for the fledgling Geffen Records label, who also released Joni Mitchell’s adult contemporary turn Wild Things Run Fast the same year. Trans wasn’t the album that convinced David Geffen to sue Neil Young for making uncharacteristic records—that would be its follow-ups Everybody’s Rockin’ and Old Ways, the country record that plays like a made-for-TV adaptation of Harvest. But the idea had to be floating through David Geffen’s head when he first heard this record. At once Young’s coldest sounding album and his most vulnerable, Trans makes its flaws immediately apparent as soon as you press play—from the murky production to the mixed-bag tracklist.

When you listen to Trans, you’re really only hearing two-thirds of it. Only six of the album’s nine songs were intended for the actual project. The other three came from a different album entirely, one that concerned young love and ancient civilizations. It was to be titled Island in the Sun, and Geffen Records quickly steered him away from the concept. Album opener “Little Thing Called Love” stems from those sessions, and it’s the record’s clearest connection to Young’s more celebrated talents. Its chorus riffs on the title of one of his most beloved songs (“Only love,” he barks in a chipper tone, “Brings you the blues”) and the ensuing chord progression would eventually find a new home in the title track of 1992’s Harvest Moon. While demonstrating the fluidity of Neil’s catalog, the song also makes for a striking introduction in its own right: a singalong before the apocalypse, when human connection would become as archaic as LaserDisc copies of the Solo Trans live show are today.

The Island songs also help highlight a major theme of Trans: it’s an album about affection. At the start of the decade, Neil Young and his wife were enrolled in intensive therapy with their son Ben, who had been diagnosed with cerebral palsy. The program’s long hours slowed Young’s hectic work schedule and opened him up to writing about fatherhood. His struggles to communicate with his child and the technology that connected them inspired the lyrics of Trans and even informed the way he recorded his vocals: “You can’t understand the words, and I can’t understand my son’s words,” he explained in Shakey. In that context, Young’s naked voice in respective side-openers “Little Thing Called Love” and “Hold on to Your Love” represents the catharsis of an emotional breakthrough. You understand the words he wants you to understand—and most of them just say, “I love you.”

Even with Human Highway serving as a vehicle for the album, Trans was originally conceived with a different film project in mind. “I had a big concept,” Young said in Shakey, “All of the electronic-voice people were working in a hospital, and the one thing they were trying to do is teach this little baby to push a button.” That metaphor pops up a few times throughout the record, most squarely in “Transformer Man,” a song Young's openly dedicated to his son. “You run the show,” he sings to him, “Direct the action with the push of a button.” The Trans film might not have moved the album to the commercial heights Neil and Geffen imagined, but available evidence suggests that it would have at least made its digital world feel warmer, more grounded and productive—the qualities fans had come to expect from Young’s work. Instead, the songs would have to stand on their own, their meaning buried inside them, like a constellation of stars you have to connect based on your own perception.

Near the end of Human Highway, a concussed Young enters a long, inscrutable dream sequence in which he, among other things, gets bathed in milk, attends a desert ritual, and becomes a world-renowned rock star. When Russ Tamblyn wakes him, they celebrate the mere fact that he’s alive. For the film’s final 10 minutes, Neil lives with a newfound sense of purpose and ambition (“We could do it,” he says, “We could be rhythm and bluesers, we could go on the road!”). Even with the fiery explosion on its way to squash his dreams and reduce the world to a pile of ash, it’s a brighter ending than what Trans leaves us with. In the lost paradise of “Like an Inca,” Young envisions himself in the aftermath of a nuclear bomb, crossing the bridge to the afterlife, at once happy and sad and totally alone. It’s a fitting finale for a heavy album, one whose only brief glimmers of hope come from our connection to one another. “I need you to let me know that there’s a heartbeat/Let it pound and pound,” Young sings in “Computer Age.” His voice is masked beyond recognition, but the pulse—steady and wild—is unmistakably his own.

0 notes