#(there *is* one called Edith too... but then she changes her name to Matilda) (no really) (and it's her husband's mother's name)

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

#yeah it would have been very convenient for his brother robert#but - oh no! - it was also convenient for his other brother who immediately set off for the treasury and then a hasty coronation#(robert had fucked off on the first crusade that's why he wasn't in the right place at the right time)#(he later ends up imprisoned by his bro in a castle where he learns welsh and writes some poems)#(say what you will about henry 1st he was at least VERY good at getting things from his older brothers)#okay it might have been an actual genuine hunting accident but i only read about dead monarchs for THE DRAMA let me have this#i always enjoy when a history book gets to this point and you find out if the author thinks it was an accident or an “accident”#the normans are french vikings and i've yet to come across one whose name is actually norman#idk if that name existed then but *I* would have named at least one son 'Norman of Normandy' just for giggles#btw every famous woman of this era is called Matilda. all of them. there's battles between competing English queens called Matilda.#i have yet to come across any explanation of why this is. i assume there's an OG Matilda who's famous maybe? possibly a saint?#(there *is* one called Edith too... but then she changes her name to Matilda) (no really) (and it's her husband's mother's name)#idk how you're supposed to write Norman Monarchy Femslash when all the women have the same name#what if i want to read about Queen Matilda's epic forbidden love for her husband's arch-enemy Queen Matilda? eh? eh? EH???#i should probably come up with a tag for my history-related nonsense i wouldn't want people to find it who seek Sensible Thoughts#history fandom#(there that'll do for a tag)

16 notes

·

View notes

Photo

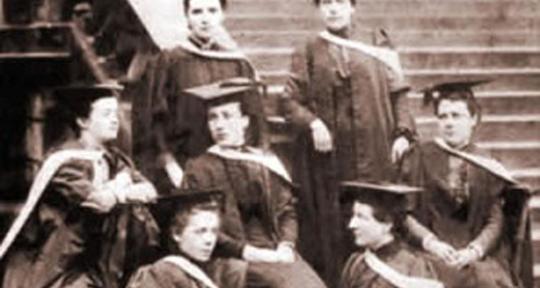

November 18th 1870 saw what has become known as the Surgeons' Hall Riot.

This is a follow on from last weeks post regarding Sophia Jex-Blake and her friend Edith Pechey, the first to female students to be admitted to study at The University of Edinburgh.

I'd just like to get another wee story out of the way before I get on to the main one, strictly speaking these were not the first women to study medicine, the first was called Margaret Ann Bulkley- but she has a remarkable story, the University and the medical fraternity knew Miss Bulkley as a man called James Barry. Born in Cork, Ireland Barry's entire adult life was lived as a man, Barry was named Margaret Ann Bulkley at birth and was known as female in childhood. Barry lived as a man in both public and private life, at least in part in order to be accepted as a university student and pursue a career as a surgeon, with Barry's birth sex only becoming known to the public and to military colleagues after death through autopsy.

Barry had risen to the rank of Inspector General in the British army the second highest medical office, she not only improved conditions for wounded soldiers, but also the conditions of the native inhabitants, and performed the first recorded cesarean section in Africa. Her birth sex only become known to the public and to military colleagues after death through autopsy, she lived as a man for over 6 decades. I will post a link afterwards about her/hm.

Back to Jex-Blake and Pechey. After these two made history by being accepted their numbers were added to over the year, Isabel Thorne, Matilda Chaplin, Helen Evans, Mary Anderson, and Emily Bovell joined them, they are now known as The Edinburgh Seven.

From the time the first two women matriculated they had been facing consistent opposition. They had people shouting at them in the streets, had to arrange to attend different lectures at the extra-mural medical college and in October 1870 they were denied permission to ‘walk the wards’ of the Infirmary. This was a decision apparently made to protect them, because the sights and illnesses in the hospital made it a place that would be too much for a faint-hearted woman to bear. The Edinburgh Seven had faced opposition every step of the way but it all culminated in the Surgeons’ Hall Riot, which would later be remembered as a turning point not just for their case but for women’s education as a whole. It all started when they were making their way to Surgeons Hall for their anatomy exam.

When the women were approaching Surgeon’s Hall they were met with a crowd of several hundred people – the majority of which were onlookers – that was big enough to stop traffic for an hour. Their male peers, several of whom were drunk and holding whisky bottles, were gathered outside shouting verbal abuse at them, throwing rubbish at them and blocking their entrance. When they were eventually ushered in by janitors and sympathetic peers they were able to get to the exam hall. However the exam was once again disrupted by the students releasing the Royal College’s pet sheep at the time ‘Poor’ Mallie into the room. After the exam the women were escorted home by a group of sympathetic Irish students who were given the name the ‘Irish Brigade’. By this point they were already covered in mud but they were also hostilely met by more screaming and mud throwing as they left the building. Not only did the women have to endure the riot itself but in January 1871 Sophia Jex-Blake had to go to court to defend herself in a defamation case filed by Mr Craig – the student she identified as being the leader of the riot. A student who interestingly was Professor Robert Christison’s classroom assistant, who was a known opponent of the Edinburgh Seven and this supported the theory that some members of faculty were in support of the riot. Mr Craig won the trial, but he was only awarded one farthing of the thousand he initially requested. This resulted in the trial being considered a silent victory for the women, the kind of covert support which was still so rare at the time. The Surgeons’ Hall Riot was an appalling event but its shocking nature was exactly what made it such an instrumental point in the women’s fight for change. The riot gained a lot of media coverage, and a particularly notable article was that written in The Scotsman which urged “all…men…to come forward and express… their detestation of the proceedings which have characterised and dishonoured the opposition to ladies pursuing the study of medicine in Edinburgh.” Although the event was a mere culmination of the abuse and opposition they had been facing for over a year, it was able to showcase the magnitude of injustice these women were facing.In 2015 a plaque to commemorate the Edinburgh Seven as part of the Historic Scotland Scheme �� and under the recommendation of one of our tutors, Jo Spiller – was put up outside Surgeons’ Hall on Nicholson Street. The plaque hangs where the Edinburgh Seven where once thrown with mud and prevented from entering an anatomy exam, and where now hundreds of female medical students walk on their way to their classes. Even though the women made it through their three year course the law disallowed them from graduating or becoming doctors.

Some of you are no doubt interested in what became of The Edinburgh Seven:

Sophia Jex-Blake had a bitter struggle, which divided the faculty and ended with her suing the University unsuccessfully in the Court of Session, she moved to Berne to qualify.

In 1889, however, largely as a result of her struggles, an Act of Parliament sanctioned degrees for women. She was one of the first female doctors in the UK. A leading campaigner for medical education for women, she was later involved in founding two medical schools for women: one in London (at a time when no other medical schools were training women) and one in Edinburgh, where she also started a women's hospital.

Edith Pechey proved her academic ability by achieving the top grade in the Chemistry exam in her first year of study, the women's abilities meant nothing, In 1873 the women had to give up the struggle to graduate at Edinburgh. One of Edith's next steps was writing to the College of Physicians in Ireland to ask them to let her take exams leading to a license in midwifery. Edith worked for a time at the Birmingham and Midland Hospital for Women then she went to the University of Bern, passed her medical exams in German at the end of January 1877 and was awarded an MD with a thesis 'Upon the constitutional causes of uterine catarrh'. Just at that time the Irish college decided to licence women doctors, and Edith passed their exams in Dublin in May

.During the next six years Edith practised medicine in Leeds, involving herself in women's health education and lecturing on a number of medical topics, including nursing. Partly in reaction to the exclusion of women by the International Medical Congress she set up the Medical Women's Federation of England and in 1882 was elected president.

Edith then spent more than 20 years in India as a senior doctor at a women's hospital and was involved in a range of social causes, following which she and her husband returned to England in 1905 and she was soon involved in the suffrage movement.

Isobel Thorne won first prize in an anatomy examination and was one of the women who re-grouped at the London School of Medicine for Women. Her diplomatic temperament meant she was a more acceptable honorary secretary on the executive (although she never actually qualified in medicine) than Sophia Jex-Blake whose nomination had threatened to stir up controversy. Thorne gave up her own ambition to be a doctor in order to commit herself to helping the school run smoothly; to become more solidly established.

An exemplary Victorian Thorne's dedication to duty and service was a precursor for the more violent campaigns of the suffragettes to achieve full enfranchisement for women.

Isabel travelled through China during the Talping Rebellion. She became convinced of the need for women to have female doctors for themselves and their children, especially women ln China and India. When the family returned to England in 1868 she started midwifery training at the Ladies Medical College, London, later describing the teaching there as inadequate.

Matilda Chaplin gained high honours in anatomy and surgery at the extramural examinations held in 1870 and 1871 at Surgeon's Hall, before a judgment in 1872 finally prohibited women students.

She also studied medicine in London and Paris and during her studies Matilda maintained connection with Edinburgh, attending some of the classes open to her there.

In 1873 Matilda obtained a certificate in midwifery from the London Obstetrics Society, the only medical qualification then obtainable by women in England, and shortly afterwards She then travelled to Japan with her husband, where she opened a school for midwives and was an author of anthropological studies. In 1879 Matilda gained the degree of M.D. at Paris, and presented as her thesis the result of her Japanese studies. She then became a licentiate of the King and Queen's College of Physicians in Ireland, and, although the only female candidate, came out first in the examination. In 1880 she lived in London, chiefly studying diseases of the eye at the Royal Free Hospital.

Helen Evan got married and did not complete her studies but her link with Edinburgh continued and she remained friends with Sophia Jex-Blake. Helen was active in promoting the care of women by women doctors. She also took a keen interest in education being "one of the first lady members of St. Andrews School Board, a position she held for 15 years". In addition to this she was a member of the council for St Leonards School for girls (now co-ed).

in 1876 her husband Alexander died suddenly from a heart attack leaving her with three children and she was unable to return to study.

When Sophia Jex-Blake began the process of founding another medical school for women in Edinburgh, Helen, with others, formed an executive committee to find suitable premises.

In 1900 and 1901 along with Miss Du Pre, Helen was a vice president of the committee of the Edinburgh Hospital and Dispensary for Women and Children, the hospital in Whitehouse Loan and the dispensary in Torphichen Place.

Mary Anderson in 1879 she received her medical doctorate from the Faculté de médecine de Paris, where she wrote her thesis on mitral stenosis and its higher frequency in women than in men. She became a senior physician at the New Hospital for Women, Marylebone. That's about all I could find on her.

Emily Bovell moved to Paris to continue her studies, when it was no longer possible to continue at Edinburgh, and eventually qualified as a doctor in Paris in 1877. The subject of her medical thesis was "Congestive Phenomena following Epileptic and Hystero-epilectic Fits"

She and her husband (physician William Allen Sturge) set up practice together in Wimpole Street, London, and Emily renewed her relationship with Queen's College, lecturing on physiology and hygiene, and running ambulance classes for ladies.

In recognition of her contribution to the medical profession, in 1880 Emily was nominated by the French Government for the "Officier d'Academie", an award very rarely conferred upon women.

The University of Edinburgh tried to right the wrongs of the past by awarding a posthumous MBChB on Saturday 6th July last year (2019). Seven present day women students accepted the degrees in their honour, as seen in the publicity pic. More on that here https://www.ed.ac.uk/edit-magazine/supplements/representing-the-edinburgh-seven

And you can read about James Barry/Margaret Ann Bulkley below. https://hekint.org/2020/04/03/a-surgeon-and-a-gentleman-the-life-of-james-barry/

39 notes

·

View notes