#jean froissart

Text

Madness of Charles VI: crossing the forest of Le Mans on an expedition against Pierre de Craon, the king, brandishing a sword, mistakes the members of his retinue for enemies and attacks them.

— Froissart's Chronicles

#charles vi#king#france#madness#mad#insanity#forest#le mans#french#medieval#middle ages#knights#knight#armour#jean froissart#chronicles#chroniques#hundred years war#art#history#europe#european#house of valois#valois#miniature#illuminated manuscript#mediaeval#sword

112 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Marriage of Henry of Lancaster and Mary de Bohun (1380/1)

From: Chronicles of England, France and Spain and the Surrounding Countries, by Sir John Froissart, Translated from the French Editions with Variations and Additions from Many Celebrated MSS, by Thomas Johnes, Esq; London: William Smith, 1848. *

Humphry, earl of Hereford and Northampton, and constable of England, was one of the greatest lords and landholders in that country; for it was said, and I, the author of this book, heard it when I resided in England, that his revenue was valued at fifty thousand nobles a-year. From this earl of Hereford there remained only two daughters as his heiresses; Blanche the eldest, and Isabella** her sister. The eldest was married to Thomas of Woodstock, earl of Buckingham. The youngest was unmarried, and the earl of Buckingham would willing have had her remain so, for then he would have enjoyed the whole of the earl of Hereford’s fortune. Upon his marriage with Eleanor, he went to reside at his handsome castle of Pleshy, in the county of Essex, thirty miles from London, which he possessed in right of his wife. He took on himself the tutelage of his sister-in-law, and had her instructed in doctrine; for it was his intention she should be professed a nun of the order of St. Clare***, which had a very rich and large convent in England. In this manner was she educated during the time the earl remained in England, before his expedition into France. She was also constantly attended by nuns from this convent, who tutored her in matters of religion, continually blaming the married state. The young lady seemed to incline to their doctrine, and thought not of marriage.

Duke John of Lancaster, being a prudent and wise man, foresaw the advantage of marrying his only son Henry, by his first wife Blanche, to the lady Mary: he was heir to all the possessions of the house of Lancaster in England, which were very considerable. The duke had for some time considered he could not choose a more desirable wife for his son than the lady who was intended for a nun, as her estates were very large, and her birth suitable to any rank; but he did not take any steps in the matter until his brother of Buckingham had set out on his expedition to France. When he had crossed the sea, the duke of Lancaster had the young lady conducted to Arundel castle; for the aunt of the two ladies was the sister of Richard, earl of Arundel, one of the most powerful barons of England.**** This lady Arundel, out of complaisance to the duke of Lancaster, and for the advancement of the young lady, went to Pleshy, where she remained with the countess of Buckingham and her sister for fifteen days. On her departure from Pleshy, she managed so well that she carried with her the lady Mary to Arundel, when the marriage was instantly consummated between her and Henry of Lancaster. During their union of twelve years, he had by her four handsome sons, Henry, Thomas, John and Humphrey, and two daughters, Blanche and Philippa.

The earl of Buckingham, as I said, had not any inclination to laugh when he heard these tidings; for it would not be necessary to divide an inheritance which the considered wholly as his own, excepting the constableship which was continued to him. When he learnt that his brothers had all been concerned in this matter, he became melancholy, and never after loved the duke of Lancaster as he had hitherto done.^

Notes:

* Johnes notes that this is from "only one of [his] mss. [manuscripts] and not in any printed copy". Chris Given-Wilson (Henry IV, Yale University Press, 2016): "This story comes from a variant manuscript of Froissart's chronicles used by Johnes, but subsequently destroyed by fire."

** Johnes: "Froissart mistakes: their names were Eleanor and Mary." Presumably, Johnes then corrects their names for the rest of the narrative?

*** Jennifer C. Ward (translator and editor), Women of the English Nobility and Gentry: 1066-1500 (Manchester Medieval Sources, Manchester University Press, 1995): "This is probably a reference to the convent of the Minoresses outside Aldgate in London where Isabella, daughter of Thomas and Eleanor, later became a nun."

**** Ward: "Joan de Bohun, Mary’s mother, was the sister of Richard FitzAlan, earl of Arundel." Given-Wilson argues the role Froissart assigns to Mary's aunt was actually played by Joan.

^ The veracity of Froissart's account has tended to be questioned, with some historians generally concluding there was probably some truth, mostly revolving around the falling out between John of Gaunt and Thomas of Woodstock over the marriage. The secretive nature of it is almost certainly untrue, given Gaunt had received a royal grant for Mary's marriage. Given-Wilson:

Froissart claimed that ‘the marriage was instantly consummated’, but this was precipitate. He also got several other details of the story wrong, such as calling the two sisters Blanche and Isabel and saying that it was their ‘aunt’ who carried Mary away from Pleshey, but the essentials of his story are corroborated by other sources and undoubtedly correct. Countess Joan was complicit in the plot, presumably hoping to give her daughter a life outside the convent. She probably commissioned a pair of illuminated psalters for the marriage.

The psalters were probably made by the de Bohun-sponsored workshop at Pleshey, one of Woodstock's principle residences. It's possible, presumably, that Joan commissioned them after the wedding but if they were commissioned before/finished by the time of the wedding, it's hard to imagine that Woodstock's household were entirely unaware that a move was being made to marry Mary to Henry.

#mary de bohun#henry iv#jean froissart#joan de bohun countess of hereford#eleanor de bohun duchess of gloucester#thomas of woodstock duke of gloucester#john of gaunt#primary source#froissart's chronicles

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Staff Pick of the Week

The Hundred Year’s War is a slight misnomer; it was actually a series of multiple wars occurring between the years 1138 and 1450 with an occasional peace treaty in between periods of intense battles. Contemporary accounts of the events happening during these years are essential for historians to gain a better understanding of the time period, even if they are exaggerated or clearly biased recordings of the events at hand. One of the many historical accounts from this time is that of Frenchman Sir John Froissart. While not born into nobility, Froissart spent much time surrounded by nobles as he chronicled the happenings of the first half of the War, and his Chronicles are a vital resource for historians about that time. He also wrote a variety of poetry and even an Arthurian Romance, along with his historical accounts.

Today’s Staff Pick of the Week is an edited version of the English translation of The Chronicles of Froissart by John Bourchier, Lord Berners (1467-1533), edited by the English classical scholar G. C. Macaulay (1852-1915). John Bourchier was an English translator, as well as a soldier and statesman. His translation of the book was said to have made a significant advancement in English historical accounts and made the book accessible to a much wider audience than simply those educated to read and understand French.

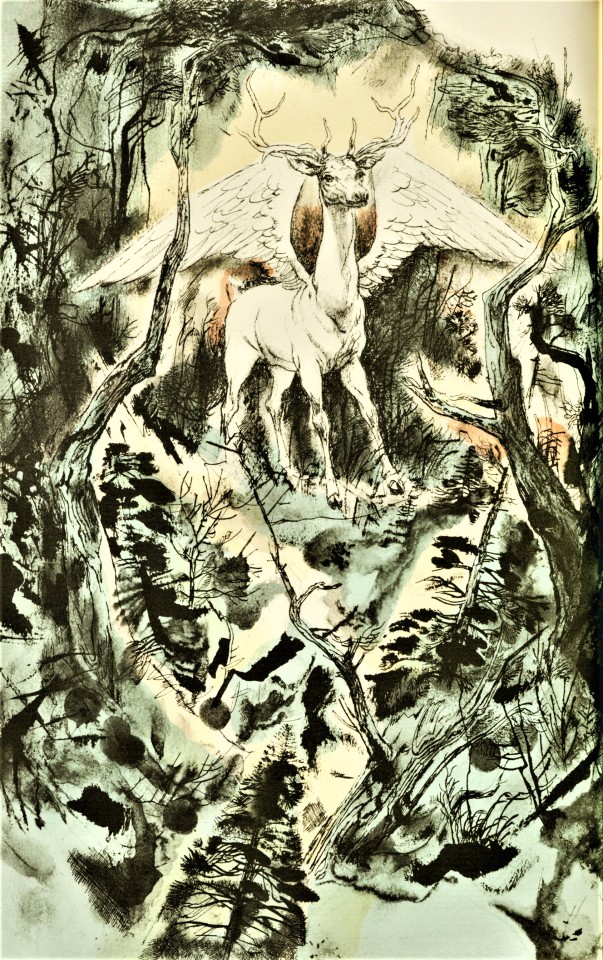

The edition shown here is the 1959 Limited Editions Club (LEC) production of Froissart's Chronicles, printed by Peter Beilenson (1905-1962) of the Peter Pauper Press, with illustrations by American artist Henry C. Pitz (1895-1976), in an edition of 1500 copies signed by the illustrator. Pitz's marginalia illustrations appear to emulate those of medieval illuminated manuscripts. There are a wide variety of people depicted in clothing of the time of the Hundred Year’s War, as well as shields, weapons, animals, and buildings which are most likely meant to add a visual link to the time in which this account was originally recorded and published. Besides these marginalia, there are 16 full page-spread illustrations reproduced from Pitz's line-and-wash paintings, hand-colored through stencils at the Walter Fischer Studio.

– Sarah S., Special Collections Graduate Intern.

View more Staff Picks.

#staff pick of the week#Jean Froissart#john froissart#Henry C. Pitz#john bourchier#G. C. Macaulay#gc macaulay#chronicles of froissart#limited editions club#LEC#Peter Beilenson#Walter Fischer Studio#marginalia#hand colored prints#illustrated books#hundred years war#The Chronicles of England France Spain and Other Places Adjoining#Sarah S.

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

history nerds <3

#les mis fanart#les amis de l'abc#les amis#les miserables#jean prouvaire#enjolras#marius pontmercy#victor hugo#marius is in napoleonic uniform#which with rendering ended up becoming a bit greener than I originally intended#enjolras is of course saint just#and jehan prouvaire’s clothing is based off an illuminated manuscript of the “Chroniques de Jehan Froissart”#my art

337 notes

·

View notes

Photo

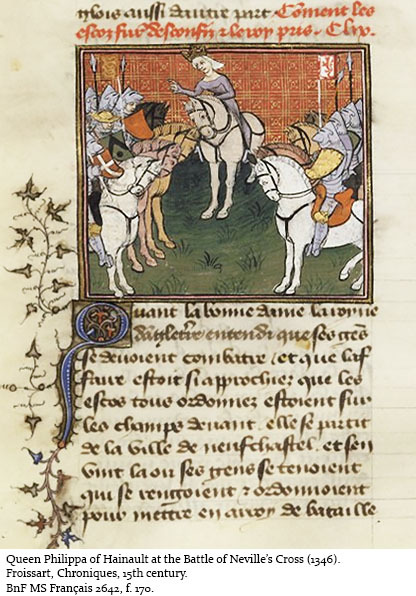

15 August 1369 ✧ Philippa of Hainault dies at around the age of 55, at Windsor.

Philippa was a pious, wise, and generous lady, a most affectionate mother, a steadfast wife, and greatly loved by her people, due to her gentleness and compassion. When faced with many trials during her life, the balance between her familial and royal duties remained stable. She was the patron of the religious community and hospital, St Katharine by the Tower, of many scholars; Queen’s College, Oxford, was founded in her honour. The queen also influenced the king to take an interest in the nation's commercial expansion, and acted briefly as his regent in 1346. For forty-one years, Philippa fulfilled her duty as queen consort, by serving the crown diligently and faithfully — amidst a turbulent and stirring time in English history — proving to be the very model of Medieval queenship.

Despite their suffering and hunger, the people of England found time to mourn their queen. The chancellor of England pointed out how ʻno Christian king or other lord in the world ever had so noble and gracious a lady for his wife (...)ʼ Jean Froissart called Philippa ʻthe most courteous, noble and liberal queen that ever reigned in her timeʼ, and had stated on an earlier occasion how the English exclaimed ʻLong live the good Philippa of Hainault [la bonne Phelippe de Hainnau], queen of England, our dear and dread lady, who brought to us and to England honour, profit, grace and tranquility.ʼ The author of the Brut wrote that Philippa was ʻa full noble and good womanʼ. He tended to refer to her as ʻthe good lady and queen.ʼ – Kathryn Warner

(The paragraphical text in the gifs is from Philippa's Latin epitaph by Froissart, which hung beside her tomb, and had been translated into English a hundred years later, before it was eventually destroyed.)

#on this day in history#our darling <3#historyedit#philippa of hainault#history#medieval history#english history#14th century#house of plantagenet#queens#our creations#our gifs

223 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Joan, Countess of Kent (29 September 1326/7 – 7 August 1385), known to history as The Fair Maid of Kent, was the mother of King Richard II of England, her son by her third husband, Edward the Black Prince, son and heir apparent of King Edward III. Although the French chronicler Jean Froissart called her "the most beautiful woman in all the realm of England, and the most loving", the appellation "Fair Maid of Kent" does not appear to be contemporary. Joan inherited the titles 4th Countess of Kent and 5th Baroness Wake of Liddell after the death of her brother John, 3rd Earl of Kent, in 1352. Joan was made a Lady of the Garter in 1378.

112 notes

·

View notes

Note

Is the last will of Elizabeth of York still exist?

Hi! Elizabeth of York left no surviving last will, but I don't think there ever was one tbh. It was not the custom for married women to write wills (since in their condition of 'femmes couvert' their goods/properties were ultimately their husbands'). This is why in this period we only commonly find widows writing last wills, because they were no longer under the 'couverture' of any man (they were 'femmes sole') and could legally dispose of their goods/properties as they saw fit without someone else's approval. Queens consort occupied a somewhat ambivalent area because they responded to no man (so they could engage in selling, purchasing, engaging with properties etc without needing their husbands to represent them under the law) but they were still ultimately subordinated to the king and were not officially 'femmes sole'.

(An interesting example is that Catherine Valois, whilst married to Owen Tudor, did write her own last will. It seems her condition as queen dowager still elevated her over all men but the king, even her second husband).

You will not find the wills of Anne of Bohemia, Elizabeth of York, Philippa of Hainault, Jane Seymour and others who died while they were still the reigning king's wife. But we know for example that Philippa of Hainault did informally ask her husband to fulfil a set of (necessarily informal) requests on her deathbed. If Elizabeth of York did the same, her words were not registered anywhere as Philippa's were by the chronicler Jean Froissart.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

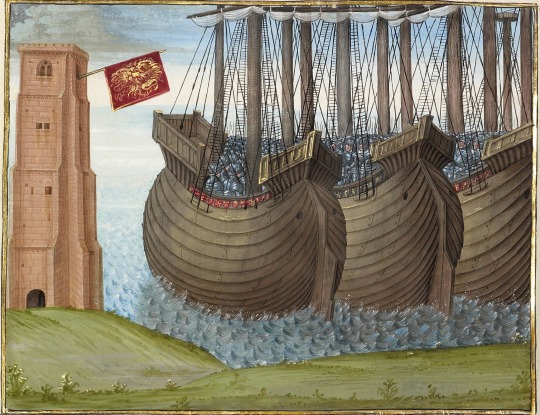

The English Fleet in Flemish Waters, from Jean Froissart’s Chronicle, Flemish, ca. 1480-1483

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Book Review: Siege Warfare During the Hundred Years War

In writing Siege Warfare during the Hundred Years War, which was published in 2018 by Pen & Sword Books, Peter Hoskins sought to correct what he perceived as an overemphasis on the role of pitched battles in the Hundred Years War. The author argues that, while not insignificant, the effects of the major field battles for which the Hundred Years War is known (Poitiers, Crecy, and Agincourt being the most famous examples) were ephemeral compared to the many sieges which brought towns and castles under a force’s control.

Hoskins begins his work with a preface, which helps to contextualize his intentions for the book, and glossary of terms, which provides a useful vocabulary to anyone unfamiliar with the finer points of late medieval warfare. From this point, the work is divided into nine chapters, the first of which provides a brief overview of the Hundred Years War, examining the underlying causes and beginning of the war and discussing each section through to the Treaty of Tours and the final English defeat.

The second chapter contextualizes siege warfare. Here the author outlines the fundamentals of a siege: when one occurs, how it is conducted from the points of view of both strategy and medieval convention, and the costs associated with a siege. The third chapter provides further context, discussing the particulars of the attack and defense of fortifications. Techniques employed by both the attackers and defenders feature heavily in this chapter, as does the organization of siege warfare.

Chapters four through nine cover many of the more important sieges of the war in great detail, advancing chronologically from the Siege of Cambrai in 1339 to the Siege of Bordeaux in 1453. These chapters discuss “The English Ascendancy, 1337-1360”, “The French Recovery, 1369-1389”, “From Harfleur to the Death of Henry V, 1415-1422”, “From the Death of Henry V to the Siege of Orleans, 1422-1429”, From Orleans to the Truce of Tours, 1429-1444”, and “The Expulsion of the English from France, 1449-1453” respectively. In all, these six chapters cover over 80 sieges which occurred over the course of the Hundred Years War.

Over these chapters one of the essential changing elements of sieges that is emphasized is the development and growing importance of gun-powder artillery. This point is reaffirmed in the book’s conclusion, which reiterates the author’s view of the importance of sieges over pitched battles and re-emphasizes the role of artillery. The conclusion is followed by two appendices which provide a series of graphs which show the outcomes of the sieges discussed in the book and provide a discussion on the duration of sieges in the period.

One odd decision the author makes is to include his notes on each chapter in a separate appendix at the end of the book. Additionally, this is where the author’s discussion on sources is included. This decision, while ensuring the flow of the primary text is not interrupted, makes examining the author’s text in the context of his use of the sources challenging. Hoskins does make clear, however, that he utilized a number of English and French primary sources, with a particular emphasis on the works of prominent chroniclers such as Jean Froissart.

Hoskins relies most heavily on secondary source material, however. The bibliography which he includes at the end of the book includes an impressive array of scholarship in both English and French and includes scholarship published as recently as 2017, and as far back as 1727.

While this work is thorough and well written, its reliance on secondary scholarship and lack of explicit historiographical discussion renders it of limited use to historians. However, students at both the graduate and undergraduate level, as well as enthusiasts with an interest in the Hundred Years war, will likely find this book and its insights into siege warfare extremely useful.

#book review#review#siege warfare during the hundred years war#art#history#hundred years war#medieval#middle ages

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

Yet it is during the twelfth and thirteenth centuries that all the inhabitants of the duchy became known under the name of Bretons, despite their linguistic diferences. Hence, at the beginning of the thirteenth century, the German poet Wolfram von Eschenbach ascribed in his Parzival the war cry "Nantes!" to the Bretons. The terms Brittany and Bretons were now applied to all the territories and inhabitants under the authority of the dukes of Brittany, and now the Romance-speaking area – future Brittany gallo or Upper Brittany –was clearly the dominant part of the duchy both politically and linguistically. It is striking to note that the same phenomenon happened in Scotland. Originally, only the Gaelic speakers considered themselves and were considered as "Scots" until c. 1260 when the other linguistic communities politically united with this kingdom (English speakers, North "Welsh" speakers, etc.) also began to be named and to name themselves as "Scots". The "French" part of Brittany was now the leading part of the duchy, and, revealingly, the medieval custom composed for the whole duchy c. 1300 (La très ancienne coutume de Bretagne) was written in French and never translated into Breton. Consequently, the Breton speakers who needed to go outside Brittany bretonnante or had an activity that implied contacts with Bretons gallos and/or foreigners absolutely needed to learn French. They were usually sent to a family of Brittany gallo in order to do so. Jean Froissart even met a "Breton bretonnant originating from Vannes [who] knew well at least three or four languages: Breton, French, English and Spanish". However, not everybody was as gifted as this man and most of them were not totally at ease with French, as Alain Bouchart, himself originating from a bretonnant region, explained in 1514 to the readers of his Grande Chroniques de Bretaigne: "I beg them to be lenient if they find any language badly embellished by lack of elegance or pleasant style, because he is a native of Brittany. Breton and French are two languages which are very challenging to pronounce easily by one mouth." More than a century later (1637), Albert le Grand would write almost exactly the same remark for the readers of his Vie des saints de la Bretagne.

Guilhem Pépin, Does a Common Language Mean a Shared Allegiance? Language, Identity, Geography and their Links with Polities: The Cases of Gascony and Brittany

#*cries in bad grammar carried over from english/french and false cognates with german* oh alain bouchart we are in it now ( ╥﹏╥)#fourteenth century#fifteenth century

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

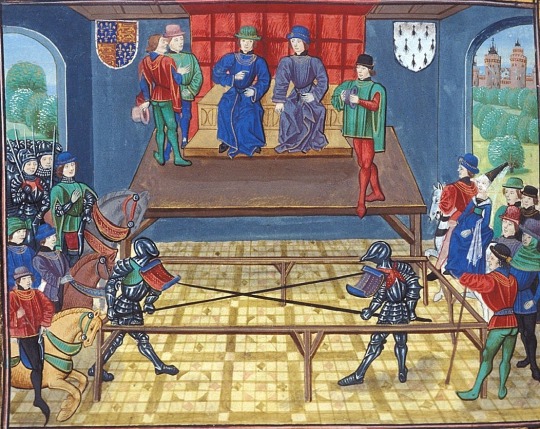

Jousting in Vannes, Brittany. The Earl of Buckingham (Thomas of Woodstock) and the Duke of Bretagne (John IV/V "The Conqueror")

Chroniques de Jean Froissart

#jousting#joust#knights#vannes#brittany#france#europe#european#history#medieval#england#knight#art#jean froissart#earl of buckingham#duke of bretagne#john the conqueror#thomas of woodstock#john iv#john v#combat#duel#chivalry#chivalric#coat of arms#heraldry

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

My heart frolics breathing the rose

And rejoice looking at my lady.

One is better to me than the other;

My heart beats as it breathes in the rose.

The smell is good to me, but the look I dare not

Playing too loud, (I) swear to you on my soul;

My heart frolics breathing the rose

And rejoice looking at my lady.

Jean Froissart (1337-1405)

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

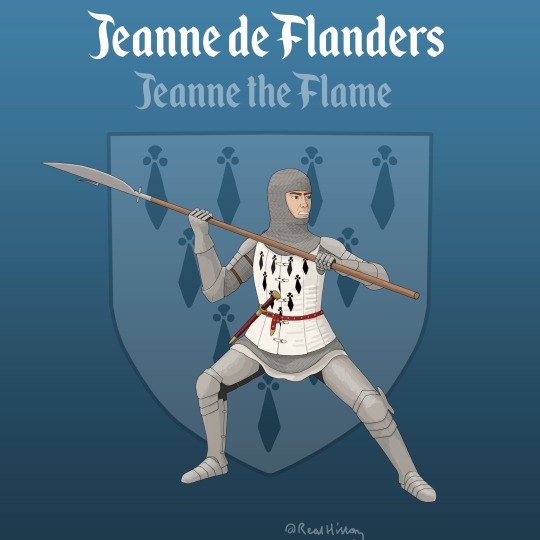

Jeanne de Flanders was the Duchess of Brittany in the 14th century.

Her husband, John de Montfort, was the son of Duke Arthur II of Brittany and the half-brother of John III.

When his brother died without a male heir, de Montfort resorted to military force to make his claim to the Duchy in the War of Breton Succession.

When her husband was imprisoned by King Philip VI of France, Jeanne declared their infant son the leader of the Montfort cause. She raised an army and marched to the town of Hennebont.

Charles of Blois besieged the town in 1342. Jeanne herself commanded the defence of the town, dressed in armour and fully armed.

At one point, she observed from a tower that Charles’ camp was lightly guarded, so she led 300 men in an assault on the camp. They destroyed supplies and burned down many tents. The besiegers attempted to cut her off from the city, so she and her men rode to Brest instead. In Brest, she gathered more soldiers, slipped out and into Hennebont with a force larger than she is left with.

As a result, she became known as Jeanne la Flamme or Jeanne the Flame.

The siege was eventually lifted after the arrival of English reinforcements. Jeanne herself later sailed to England to seek further aid from King Edward.

When her fleet was attacked en route by Louis of Spain, Jeanne led the defence of her ship against a boarding action while wielding a sharp glaive.

By 1345, the Montfort cause in Brittany was essentially taken over by the English.

That same year, Edward had Jeanne confined at in England. It was said the reason for her confinement was that she had become insane, but there is no evidence for this. It is more likely that Edward wanted to more firmly secure Brittany under his power.

She spent the rest of her life in captivity, living long enough to see her son become Duke John IV of Brittany before she died in 1374.

Jeanne de Flanders is a member of the relatively small club of identifiable female individuals who fought in combat. The chronicler Jean Froissart commented that she “had the courage of a man and the heart of a lion.”

Scottish philosopher David Hume described her as the “most extraordinary woman of her age.”

#history#real history#military history#medieval#middle ages#medieval history#medieval europe#warrior#warrior women#powerful women#historical women#woman#warrior woman#women

45 notes

·

View notes

Photo

In addition to the debate of medieval queenship, it does well to remember Queen Philippa of England’s doings, her perceptions as queen and how she set a model to those who came after her in an almost stark contrast to her predecessor, Queen Isabel. In saying so, here’s an excerpt of “The Red Prince”, by historian Helen Carr. [pp.10-11]

“In 1319, when negotiations were in place for Edward and Philippa’s marriage, Bishop Walter de Stapledon, an ambassador for King Edward II, was sent to Hainault to inspect the future Queen of England.

In his register, he provides a detailed report of her appearance; she had dark hair, a ‘high and broad’ forehead, with ‘broad’ nostrils, but ‘no snub nose, full lips and was ‘brown of skin all over’.

The chronicler John Hardyng predicted Philippa would bear many children. He described her as having ‘good hippes’, necessary to successfully carry twelve babies to term. With just thirteen months between John of Gaunt and Edmund of Langley, it is questionable whether the relentlessly virile Edward ever left his wife alone. Philippa was a portrait of maternal femininity. She did what all good Queens were expected to do: give birth to heirs. Her children were her absolute priority.

Philippa of Hainault took on the responsibility of other children as well as her own. She adopted orphaned children of the nobility into the nursery such as Joan of Kent, after her mother died and her father was beheaded for treason. Philippa also cared for the children of those in her service, such as Katherine and Philippa de Röet, whose Flemish father, Pan de Röet, had died on campaign in France.

She extended her interests further into rural industry by opening mines in Tyndale and Derbyshire, providing opportunity and industry for local communities and even prompting the English to use their wool to manufacture their own garments--where cloth was previously bought in from Flanders. In 1341, she also enhanced the growth of Oxford University by supporting the foundation of The Queen’s College, Oxford. The chronicler Jean Froissart worked for the Queen as her secretary from 1361 to her death in 1369 and described her as ‘courteous, humble, devout...and tall’.

Where Philippa of Hainault was humble, caring, loyal and dutiful, Edward III was confident, ambitious and hot headed. (...)”.

Fancast: Alba Galocha Vallejo as Queen Philippa.

#Philippa of Hainault#Queen Philippa of England#Edward III#John of Gaunt#Alba Galocha Valejo#fancast#Plantagenet dynasty#The Plantagenets#medieval England#middle ages#queenship

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dance of the Wodehouses ... from the Chronicles of Jean Froissart at the British Library, XV century ... wild men dancing and jumping around while their outfits seem to be on fire: small nests of flames can be seen all over their green suits.

... just wondering how the music would have sounded. Notice the musicians in the upper right corner with brass instruments.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

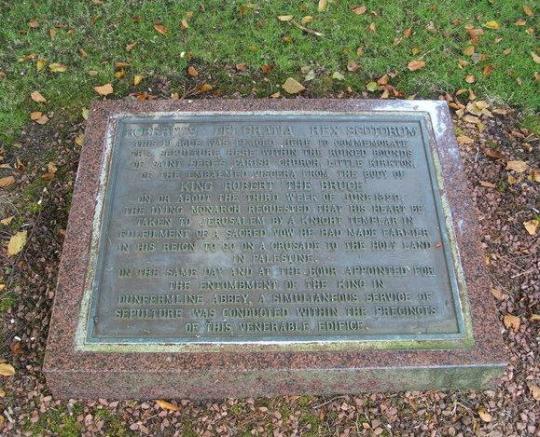

On 7th June 1329 Robert the Bruce died at his manor near Cardross, Dumbarton.

The Bruce “house” was more likely a fortified property and although it is long gone historians say it was a piece of land called Pillanflatt, which lay between the extreme south end of modern Renton and what is now Dalmoak farmsteading.

The Bruce spent the last 3 years of his life. He hunted in the area with hawks, and seemingly kept a lion in a cage, which, as historian Dr I. M. M. MacPhail once wrote, was “armorially appropriate“ for the King of Scotland. A plaque was commissioned and unveiled at the old medieval churchyard of Cardross, in Levengrove Park, Dumbarton, on the 1st September, 2001, it reads;

ROBERTUS DEI GRATIA REX SCOTORUM

THIS PLAQUE WAS PLACED HERE TO COMMEMORATE

THE SEPULTURE HERE WITHIN THE RUINED BOUNDS

OF SAINT SERF'S PARISH CHURCH, LITTLE KIRKTON,

OF THE EMBALMED VISCERA FROM THE BODY OF

KING ROBERT 'THE BRUCE'

ON OR ABOUT THE THIRD WEEK OF JUNE 1329.

THE DYING MONARCH REQUESTED THAT HIS HEART BE

TAKEN TO JERUSALEM BY A KNIGHT TEMPLAR IN

FULFILMENT OF A SACRED VOW HE HAD MADE EARLIER

IN HIS REIGN TO GO ON A CRUSADE TO THE HOLY LAND

IN PALESTINE.

ON THE SAME DAY AND AT THE HOUR APPOINTED FOR

THE ENTOMBMENT OF THE KING IN

DUNFERMLINE ABBEY, A SIMULTANEOUS SERVICE OF

SEPULTURE WAS CONDUCTED WITHIN THE PRECINCTS

OF THIS VENERABLE EDIFICE.

I think most of you will know that The Bruce’s heart never made it to The Holy Land, the ever-restless Douglas stopped to support Spain’s Alfonso XI in his campaign against the Moors and was killed in battle. According to legend, he threw the casket holding Bruce’s heart ahead of him before entering the fray, declaring,

“Lead on brave heart, I’ll follow thee.”

Bruce’s heart was ultimately retrieved and interred at Melrose Abbey, while the rest of his body was laid to rest in the royal mausoleum at Dunfermline Abbey. The king’s epitaph declared Bruce

'Here lies the unconquered Robert, blessed king. Who reads his deeds lives again all the battles he fought. By his integrity he brought to freedom the kingdom of the Scots; now he dwells in Heaven's heights.' .”

The brass effigy placed over the burial site in 1889, gifted to the abbey church by the Bruces of Elgin. Only part of Bruce was buried at Dunfermline. His entrails were buried at Cardross. The appeal of being buried in so many different places was that the religious communities in those places would pray and say masses for his soul following his death, interceding to God to reduce Bruce's time in Purgatory. During the course of his long and dramatic career, Bruce had committed some whopping sins in pursuit of his ambitions, so he could probably do with all the help he could get! Bruce himselh chose Dunfermline, some say as early as 1314, as his last resting place, due to it’s connection with previous Scottish monarchs, he is said to have wanted to be with his 'royal ancestors' St Margaret, Malcolm III, Edgar, Alexander I, David I and Alexander III. It was also the ancient capital of Scotland, only last month was it officially elevated to that of City status.

Following his death in the west, Bruce's body was proceeded eastwards to Dunfermline, making stops at Dunipace and Cambuskenneth (and possibly Culross). Some 8,000 lbs of wax candles were burned in the abbey as the king's body was processed into the choir in a canopied hearse made of imported Baltic wood. The procession of mourners was led by the king's grandson Robert the Steward - who would have been about thirteen at the time - perhaps because the king's five year old son was deemed too young. The only source to offer a date for Bruce's funeral is Jean Froissart's Croniques, which implausibly states that this took place on 7th November 1327, - Ha! Spot the discrepancy with the date? Precisely one year and seven months before his death! It shows even those old chroniclers got things wrong, or perhaps it was what we call now a typo.

During his life, King Robert paid for an ornate tomb to be built for him at Dunfermline, ordering marble from as far afield as Italy. Unfortunately, the ornate tomb was destroyed during the Reformation and the exact site of Bruce's burial site was lost. A skeleton was uncovered in 1818 was initially believed to be King Robert's primarily because the sternum had been cut open, strongly suggesting the heart had been removed, and had clearly been buried in a privileged position within the abbey church.

However, Dr Michael Penman of the University of Stirling has recently raised doubts about this conclusion. Firstly, separate heart burials were not uncommon in medieval Scotland (although they had become less common by the time of Bruce's death), so the fact that the heart had apparently been removed is not necessarily unusual. Furthermore, while we would expect Bruce to enjoy a prominent position within the abbey church, the space directly in front of the altar would more likely have been reserved for King David I, who had founded the abbey and whose mother St Margaret was buried directly behind the altar. In fact, Bruce was probably buried in the Lady Chapel in the north transept of the abbey church. This is where his nephew Thomas Randolph, Earl of Moray, his sister Christian, and his great-grandson Robert Stewart, Duke of Albany chose to be buried, their decision likely based on a desire to be buried close to King Robert.

In November 1819 the skeleton was put on display to the public before being re-interred where it had been found in a coffin engraved with the phrase 'ROBERT BRUCE, 1329, 1819'. In 1889 the Bruces of Elgin paid for a brass effigy to be placed over the spot where the skeleton had been buried. Several casts were made of the skull, if you’ve visited the Abbey you will have no doubt seen one of them at the tomb, this leads me to point out that if it is King David’s remains, well all those reconstructions of how Robert would have looked are also actually how David may have looked! But it may still be oor Robert, acording to the article below it’s a 50% chance.

Pics are the tomb at Dunfermline and a depiction of how the original may have looked, the third pic is the plaque at Cardross.

https://www.thecourier.co.uk/fp/news/fife/1856128/bruce-tombskeleton-of-robert-the-bruce-may-actually-be-king-david-i/

23 notes

·

View notes