Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

The Burberry Chavs

The Burberry case mentioned the struggle the brand was having with the “so-called Chav” social group. Here is the Urban Dictionary definition of a Chav (posted in 2010): “male chavs wear fake burberry (bought from sketchy market stalls), trainers, fake gold jewelry, and anything they can get from the sports soccer sale. they are seen with cigarettes, drugs and cheap alcohol(eg strongbow or tesco value lager)… make sure you don't make eye contact or they'll yell at you in your face, you won’t understand what their saying though.” For example, see below.

Further, in the early 2000s, many pubs in the U.K. banned patrons from wearing Burberry in an effort to cut down on “alcohol-fueled violence” (see here and here). Not exactly a positive brand association.

Despite that, I do wonder how much of a negative impact this actually has on the brand. From 2003 to 2006, sales grew at 8% annually and operating profit at 12%, both strong results. Further, I imagine this trend would have less of an impact outside of the U.K. like in the China and U.S. markets where consumers would likely have few (if any) associations between Burberry and Chavs.

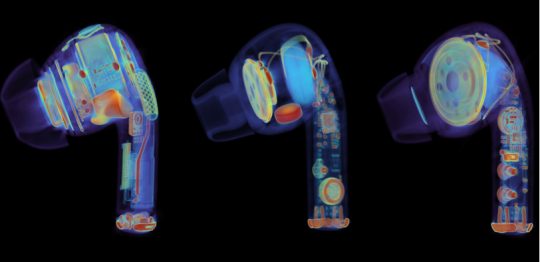

Even if it isn’t currently (as of the case) having a massive impact on Burberry financially, it does create a threat to the brand going forward. While preventing counterfeit items (in an effort to cut down on Chavs wearing Burberry items) would be nearly impossible, if Burberry can find ways to create meaningful quality differentiation between the real and counterfeit items that would support the brand. While not a perfect comparison, I think about the x-ray image of real AirPods vs counterfeits that I’ve seen on social media in the past that makes the quality differences obvious (real AirPod on the left).

Another option would be to rebrand/reposition Burberry away from the styles the Chavs wear to the extent the can shift from the check pattern without sacrificing important parts of their brand image. Over time this would likely help reduce the brand’s association with the Chavs, though comes at the risk of losing some of Burberry’s iconic fashion status.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

AI in Retirement Planning: The Need for Friction

The wealth management and retirement planning industry is likely primed for some level of disruption from AI. Finance, investing, and retirement planning are complicated topics that many people don’t have a strong understanding of. As such, this create an area for AI to provide advice to people on how to best prepare for retirement, with potential examples being what investments to make, how much money to save, and how to best structure investments to save money on future taxes. Further, wealth management and tax experts traditionally are relatively expensive (for example, according to US News, a typical wealth management advisor fee is 1% of client assets each year), meaning that AI solutions could provide customers significant cost savings in addition to making retirement planning more accessible to less-wealthy individuals. In addition, for years already companies like Fidelity have offered Robo Advisors that will likely continue to improve in the future as AI capabilities are added (see image below).

With that in mind, when implementing AI in the wealth management industry, there is a strong need for “good frictions” to create better customer experiences (with emphasis on their investment outcomes). There are several areas/examples where frictions will be important, depending on how AI tools are implemented. For instance:

Requiring customers to spend meaningful time inputting data based on their goals. Goals in retirement are different for each person, and these goals should directly influence investment decisions to maximize a client’s probability of being able to achieve them. For a future AI tool, slowing down the onboarding process to ensure data on goals is correct will be vital to determining optimal investment decisions. Additionally, an AI tool could be supplemented with human involvement to have more personal conversations to better understand a client’s goals (and make sure they are properly accounted for) and ask questions that make sure the client has the correct understanding of their own goals (in case what they think their goal is isn’t what their actual goal is)

Find ways to increase transparency into customer options and costs. According to the reading, having transparency along the customer journey is essential for customer loyalty and trust. AI wealth management tools will require transparency improvements beyond what is requirement by regulations (ex: the famous “past performance is not indicative of future returns…”) to help customers understand what they are paying for, how decisions are made, and what risks are involved.

Being mindful that in the investment world, what happened in the past is not what will necessarily happen in the future. Many AI and machine learning models rely heavily on data from things that happened in the past. As a result, people implementing AI tools in the wealth management space will need to be extremely mindful that future investment return outcomes may not be like those in the past. For example, over the past 30+ years, U.S. equities have performed extremely well. However, basing investment decisions predominately off this data from the past could cause an AI tool to recommend a portfolio that is under-diversified from a country and asset class perspective. According to academic paper “Stocks for the long run? Evidence from a broad sample of developed markets,” researched estimated that a diversified equity investor with a 30-year investment horizon would have a 12% chance to lose relative to inflation. This type of outcome could be devasting for someone saving for retirement. However, data looking solely at the last 30+ years of U.S. equity returns may cause an AI tool to come up with a portfolio that over-invests in U.S. equities if not implemented with the proper oversight, potentially increasing the risk of underperformance and not meeting retirement goals.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Experimentation Risks + Simplicity of Nudging

Reflecting on the reading, “The Discipline of Business Experimentation,” while I generally agree with the premise of the importance of experimenting and beta testing for businesses before making changes, I felt that not enough emphasis was put on the potential costs of experimentation. As an example, the reading mentions the success of Kohl’s determining that it was better to open stores an hour later, but does not mention potential risks in experimenting with new opening hours. For one, such an experiment could confuse customers on what business hours are, potentially leading to lost sales. Further, if reduced hours are found to be worse off for the business, it could be challenging to change back as customers may have learned the old (shorter) hours and employees may resist new hours if it means working different shift times. Lastly, it’s possible too that competitors’ reactions to changes made due to an experiment wouldn’t be properly accounted for and could be underappreciated (ex: a Kohl’s competitor opening their store earlier in response to Kohl’s opening later and poaching customers).

With that said, in the context of the Nudging reading, many potential options to nudge consumers have relatively low risks from an experimentation standpoint. For instance, when booking a flights, consumers are typically offered the opportunity to purchase travel insurance that includes the simple nudge about other customers protecting their trip (see screenshot below: “96,107 American Airlines customers protected their trip in the last 7 days”). This nudge is extremely easy to implement and test, low risk, and ultimately likely leads to higher sales of travel insurance (though by how much is unknown). As such, there are many low risk ways for companies to nudge consumers (and experiment to improve these nudges) into desired behavior that increases their value as customers.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Heineken in flux

Reading the case, it’s clear that Heineken’s lack of a cohesive branding strategy created a vulnerability for other beer companies (like Modelo) to exploit. Brand images and perceptions can take years to establish in the minds of consumers even with consistent company messaging. With that in mind, Heineken underwent significant changes in the late 1980s and 1990s. For instance, they changed advertising agencies multiple times, acquired their U.S. importer, and changed leadership (eliminating institutional knowledge). Further, ads/marketing has numerous changes, with ads that 1) focused on high quality (1991), 2) portrayed competing beers as faddish (1988), and 3) building in humor and not mentioning product status (1996), while they also tried new beer packaging in 1994. I imagine that this organizational flux and changes in advertising strategy made it harder for Heineken to cultivate a brand that would do well with U.S. consumers and compete with players like Modelo. On the other hand for Corona, their traditional “Fun, Sun, Beach” messaging was much more consistent through time and likely resonated with consumers better because of it.

Now, nearly 25 years after the case, I wonder if anything has changed. Doing a quick google image search on Heineken ads and Corona ads (see below), I notice that the Corona ads have a consistent image around the beach (similar to the branding from the late 1990s) that help build a positive association for me with Corona beer while the Heineken ads consist mostly of pictures of a beer bottle that don’t elicit any emotions for me. I also know that Modelo and Corona beers have vastly outsold Heineken in the U.S. in recent years. It’s hard to imagine these branding choices aren’t at least part of the reason for Modelo and Corona’s success.

Lastly, I have a personal anecdote. Michael Foley of Heineken said that “beer is all marketing” and that “there’s no mystery about brewing beer” in the case. With that said, in my whole life the only mass-produced beer I’ve disliked was the Heineken I drank at the Málaga airport in Spain. Maybe beer isn’t all marketing after all.

2 notes

·

View notes