#what would the Conventionist do?

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Les Mis fandom, you know what to do!

24K notes

·

View notes

Note

Hey yuor the Skoodge guy!

Two questions:

1. What does Zim see in him?

2. What does he see in Skoodge?

Wait isn't this the same question phrased in two different ways

im gonna assume its "Zim see in him" and "He sees in Zim" for this!!!! ... im the skoodge guy.... you flatter me. far too much. eradicated.

and endeared.

i Want to answer this as unbiased as possible....... so im going to do so under the assumption that we are talking about Canon.

Zim... doesn't see a whole lot in Skoodge, I don't think. Maybe a pawn, maybe a loyal follower which he 'rightfully' deserves. But then again, Zim has been given the opportunity to have followers before, and he's never really... taken advantage of them. Mostly, Zim seems to want nothing to do with people worshiping and idolizing him! Gets all... jittery and weird. Space morons episode I think. Whichever one was the one where the alien cultists/conventionists found him.

So then if Zim doesn't see Skoodge as a follower, and pawn is still up in the air... does he see him as. A nuisance? Probably. But Zim ALSO has a tendency to regard Gir as a nuisance, despite the facts pointing towards him enjoying the robot's company/general existence.

There's not too much canon Zim-Skoodge interaction dialogue, but Hobo-13 establishes a strange dynamic of Zim bossing Skoodge around and Skoodge blindly accepting it. I don't know if that's because of the situation (Zim being the leader there) or if that's just their whole Thing, but I'm leaning towards the latter, because in Day of Da Spookies (script) their relationship remains pretty much the exact same. The only thing that changes is Zim is a lot more hostile? To Skoodge, for conquering his planet first (obviously jealous/upset that Skoodge has managed to beat his in record time, whereas Zim hasn't made much, if any progress, on Earth).

And with the Trial, too, it's clear that this is how the two have interacted with each other for a long while. I just. Have no idea why.

Skoodge just. Seems to blindly follow Zim, regarding him in just about the same light as a typical irken would the Tallest.

Taking his command with much less hesitation, too. He looks at the Tallest before going into the cannon, but whenever Zim has a plan, he takes it in stride. Even though he MUST be aware of the usually explode-y consequences that Zim's plans tend to generate. No irken wouldn't know. Is he just ignorant? I really doubt it. He's been there since the beginning. He was definitely there to see the second power outage on Irk, and the mayhem of OID1. He's just... that thoroughly blinded by his whatever that he has towards Zim.

And I really really want to call it a crush, but this is canon I'm talking about! Love doesn't exist in this show, yadda yadda, whatever! Who cares! If it isn't a crush, it's definitely the closest irken equivalent to it! Maybe Zim looks like a giant donut to Skoodge! Who knows. He's deranged. Just about as insane as Zim is. Thankfully, all his energy is directed towards surviving whatever Zim or the universe throws at him, instead of anything else. That might end up resulting in a bunch of casualties.

So. The questions. They remain!

What does Zim see in Skoodge?

I think he sees a tool. Something to be used at his disposal. Easily and readily accessible, because that's what Skoodge has molded himself to be.

And maybe, underneath that. Just the TEENSIEST tiniest bit. Zim sees an ally. (Or a friend.)

What does Skoodge see in Zim?

Everything.

Or at least way more than he should.

Or maybe he just sees someone interesting. A short irken with the complex of a taller one. Strong and commandeering despite his height. And he admires that.

thanks for letting me be insane about them. i love you dearly.

somehow this still ended up being about my specific interpretations of them. theres just so little in canon....... and i dont wanna just end it at ''zim hates skoodge and skoodge is okay with that'' because the tallest hate skoodge! and skoodge is okay with it! expects it! and the way skoodge reacts to the tallest and zim are different i think! he speaks out to purple! and obeys zim without question!

and zim....... is fine with him following him around. for the most part. he at least never kicks him out of the base. and that has to mean something

skoodge runs away a lot from things........ but he always comes back to zim

#zasr#yeah its going in there#even though that isnt the focus#actually it would be more of#if anything#zasf#but...... i have sick twisted priorities.#gerrnswers#iz analysis#i think#flop#punchbuggy#skoodge rant

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

// few thoughts, just…

For @betterto-die-thanto-crawl & @songandflame ❤️ (mostly)…

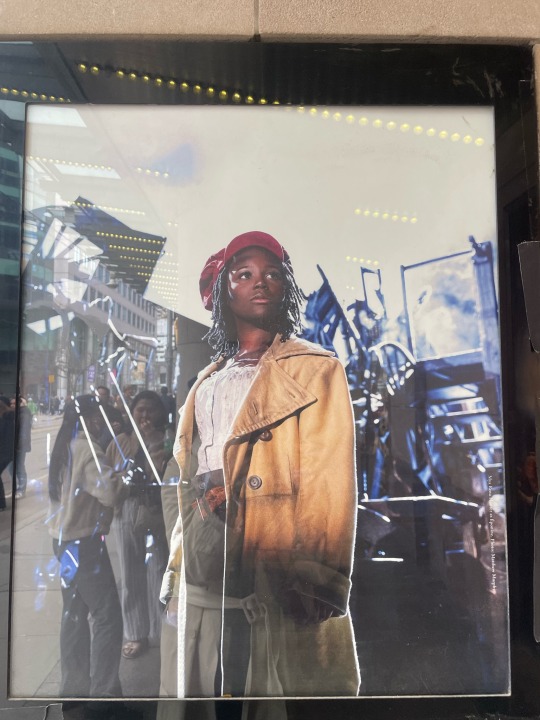

Les Mis changes/improvements (North American tour April 21, 2024 ~ Toronto)

In the prologue, they extensively play out and highlight Jean aka Madeline getting thrown out and the priests kindness changing him, if you know the book… a lot of time is spent on the priest, the radical conventionist and Jean the every man.

In “Lovely ladies” it is sung largely by the same people however the presence of an obvious pimp coercing the women (not just Fantine) changes the context to fit the novel context I would observe better.

“Don’t make it a change to have a girl who can’t refuse” sung by all women in Lovely ladies whilst the pimp remains silent and benefits from them and Fantine is silent on the floor robbed her voice.

Young! Cossette and Young! Eponine are understudied by the same young person (as though I can’t reiterate their similarities and differences enough).

Doll scene happens (everyone cheered!)

Cosette is blonde haired and white (per most casting of the show and contrary to her medium brown hair in the book juxtaposed by Fantine being blonde).

Fantine and Eponine were both played brilliantly by mixed black women (so potential commentary on exploitation of black bodies and for Eponine colourism as she’s not considered “good enough” or “pretty” in the novel cause malnutrition and abuse etc here it can be read as colourism bonus points cause black people have been in France since the 17th century).

Eponine extra song that sounds (to me) like pining - she briefly highlights their similarities and differences and longs to be acquainted again as she feels remorse for her mothers actions and longs to be supportive of Cossette (did I mention I love Eponine?)

Enj being a flirt with girls of the Les Amis de ABC (all the bis cheered!)

Drink with me - Grantaire and Enj nearly kiss - Enj starts it!

Empty chairs takes place in something like the 1830s equivalent of a catacomb (ouchie).

The ending is functionally the same, but not, they break then 4th wall in the finale calling back to “do you hear the people sing?” And “one day more” asking quite bluntly the audience to consider what they’ve learned and to join them (the Amis de ABC) in improving the world despite or perhaps because sacrificing everything for a better tomorrow cause in empty chairs “but tomorrow never came.”

#ooc / vanquishing scruples#muse: enjolras#muse: éponine#music / aren’t brainy people obtuse!#les mis meta#les mis letters#les mis musical#les miserables#victor hugo#meta

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

I think it’s interesting that Sister Simplice’s honesty permits her to transcend age (no one can tell how old she is) and gender (”a person - we dare not say a woman���) when honesty’s importance is so mixed in the novel as a whole and in this section in particular. Of course, many instances of lying in this book are obviously harmful. We’ve just seen how the Thénardiers lie to Fantine in their letters to try to get as much money as possible out of her while separating her from Cosette. However, we’ve also seen the consequences of a focus on honesty above all else. Madeleine’s factory only requires “honesty” from the workers, but that demand is what got Fantine fired. Fantine may not have been hired at all if she’d told the truth about having a child outside of marriage, and then she wouldn’t have ever experienced the financial stability she had while working at the factory. Similarly, Jean Valjean relies on lies to stay safe. In theory, it’d be wonderful if he could tell the truth of his life, but false identities are what keep him out of prison.

I don’t want to imply that Sister Simplice’s honesty is a form of privilege. Hugo specifies that her name comes from a martyr who chose to die rather than lie, suggesting that she too would tell the truth even if it cost her her life. I think it’s instead a sign that there are multiple ways to be “good” and that they all have their flaws. We saw this with the bishop as well. His commitment to charity and compassion undoubtedly makes him good and admirable, but his avoidance of politics makes it difficult for him to address the systemic aspects of these issues. In contrast, the Conventionist was working for political change, but that came at the cost of violence. Even though he was opposed to monarchy, he specified that he didn’t vote for the death of the king, and while he did feel that the violence of the old order explained the violence of the Revolution, the fact that he spent so much time on this question indicates that it’s a difficult issue to navigate.

In addition to allowing multiple systems of morality to co-exist, I think Hugo is pointing out the difference between actually adhering to a moral code and paying lip service to it. Everyone in Montreuil-sur-Mer seems fixated on honesty, but most of them (such as Mme Victurnien) are hypocritical about it as well. Sister Simplice, however, is genuinely honest. When she preaches the value of this trait, she’s not doing so to harm others, but out of a real belief that it’s right.

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

Here is ~2500 words of Petit-Gervais and the Conventionist’s shepherd boy fic. There may be more at some point, if I ever write it, but my current writing pace suggests that it’ll be a while, if it happens at all. So I thought I’d share this chunk, for posterity and because I quite like it.

@pilferingapples

~*~

The week after the prime part of Petit-Gervais' fortune had been stolen from him, a storm raged through the area. Petit-Gervais had lingered, ashamed to go home without his money and hoping against hope that the gendarmes would bring in the villain who had robbed him. But as the days went by this seemed less and less likely, and Petit-Gervais had resolved to be on his way the very day the tempest hit.

The rain quickly tore through the shelter he had built, and he wasted only a few moments staring mournfully at the wreckage before setting off to find something sturdier. There was a town nearby; perhaps someone would take pity on him and let him inside. Perhaps they would even have food to share! The thought bolstered his step and made him nearly cheerful as the marmot on his back screamed into the wind.

Unlike in Paris, the rain in this country fell hard but not long. By the time Petit-Gervais finally stumbled across a dwelling-place, the worst had passed and only a drizzle remained. Petit-Gervais and his marmot were soaked to the bone.

He nearly tripped over the hut before he noticed it. It was a rude structure, built into a hillside and hidden from view by a strategic thicket. Petit-Gervais wouldn't have found it at all save for the slight break in the vegetation that signaled a path branching off of the main road.

"Maybe a hermit," he said aloud in his own language. The marmot chittered unhappily on his back and Petit-Gervais laughed. "There's only one way to find out," he declared, and took the path.

It was not a hermit who answered Petit-Gervais' knock but a boy, no older than Petit-Gervais, with a mop of sandy hair falling into his eyes. His face, furrowed with wariness, cleared into honest surprise when he saw Petit-Gervais. "What were you doing out in the storm?" he asked, in French. He had an accent Petit-Gervais had never heard before.

"Trying to find shelter from it," Petit-Gervais said. "I'm Petit-Gervais. Can I come inside and dry off? I can make her dance for you." He half turned, showing off the marmot.

The boy considered this request, then nodded and stepped aside to let Petit-Gervais inside. "Welcome to my home," he said. "I'm called Jean-la-Liberté." This last pronouncement held a note of challenge.

Petit-Gervais burst out laughing. "What are you, a Revolutionist?"

"Yes." Jean-la-Liberty spoke stiffly, coldly even. He'd drawn himself up to his full height, barely taller than Petit-Gervais. "Is that a problem?"

Petit-Gervais shrugged. "It's all politics," he said. "King, no King, it doesn't affect me."

"Under the Republic we were free." His voice was still stiff. "Good men spilled blood to deliver us from tyranny."

"And I was robbed last week," Petit-Gervais countered, the insult to both pride and livelihood still fresh enough to sting. "Would the Republic have stopped that?"

Jean-la-Liberté hesitated. "All men were held to the same laws," he said finally. "A rich man who robbed you would be punished just as harshly as a poor one."

"Well this one wasn't rich," Petit-Gervais said. "So I guess it doesn't matter. Can I still come in?"

Jean-la-Liberté hesitated a moment longer, muttered something to himself that Petit-Gervais didn't catch, and nodded.

"Thank you," Petit-Gervais said.

It took a moment or two for his eyes to adjust to the gloom inside. When they did, Petit-Gervais saw a rough-hewn table, with crumbs liberally scattered across its surface, and two chairs. A bed sat in one corner, with a sort of chair on wheels next to it and a straw pallet on the floor at its feet. The other side of the room held a crude kitchen, more than Petit-Gervais and his comrades had had in Paris but less than what he remembered his mother having at home. Apart from a half loaf of bread sitting out, it didn't seem to have been used in a while.

"Are you on your own here?" Petit-Gervais asked, taking it all in.

Jean-la-Liberté nodded. "My teacher passed into the care of the Supreme Being two years ago."

"And you've been here ever since? Alone?" Petit-Gervais couldn't hide his horror at this prospect. All his life he had been in company, first among his family and then, in Paris, among his fellow migrants. Even the trip home had been mostly spent with others, fellow workers going home or rival urchins to be merrily insulted. To be alone seemed to him a fate almost worse than death. At least in Heaven you had company.

"I have the sheep." Jean-la-Liberté sounded defensive again, and this time Petit-Gervais' heart filled with pity. No wonder he was so prickly, with only sheep for company.

"Well I'm glad I came by then," Petit-Gervais said. He moved towards the hearth, where a smoldering fire gave off more heat than light. He swung the marmot cage off his back and set it down in front of the hearth, then held out his own frozen hands towards the warmth.

Jean-la-Liberté hadn't answered, and when Petit-Gervais glanced over he found the other boy looking at him with an odd expression. "What?" he asked.

"No one's been glad to come here in a long time," Jean-la-Liberté said finally.

Petit-Gervais shrugged philosophically. "There's a first time for everything," he said, and, for the first time, Jean-la-Liberté smiled.

They stayed silent for a time, Petit-Gervais drying off and Jean-la-Liberté watching him, until Petit-Gervais' stomach loudly reminded him of the other thing he'd been hoping to find that evening.

Jean-la-Liberty jumped. "I'm sorry!" he said. "I've been a bad host. Are you hungry?"

"Always," Petit-Gervais said cheerfully.

Jean-la-Liberté moved to the kitchen corner and took out half a loaf of bread and a piece of cheese. These he put on the table, then went back for a jug of something and two cups to complete the meal. He paused, as thought realizing something, and looked over at the marmot. "Does it..." he began.

"She eats what I do," Petit-Gervais assured him. Jean-la-Liberté relaxed.

"Will you join me for a meal?" he asked. Petit-Gervais, now warmly damp rather than soaked and frozen, did not need to be asked twice.

"Where are you traveling from?" Jean-la-Liberté asked as they sat. He tore off a piece of bread for himself and passed Petit-Gervais the loaf. It was several days old, by the feel of it, but nowhere near the hardest loaf Petit-Gervais had ever eaten. He took a piece for himself and passed part of it down to the marmot, who grabbed for it eagerly.

"Paris," Petit-Gervais said. He peered into the jug, found it to be filled with wine, and poured himself a generous serving. Through a mouthful of bread he added, "Do you want to hear about it?"

Jean-la-Liberté did, and so Petit-Gervais launched into stories, telling Jean-la-Liberté about living in the city, about the adventures he'd had and the fights he'd been in and, laughing at his own stupidity, about the bumbling mistakes he'd made when arriving as an ignorant four-year-old fresh from the mountains. Jean-la-Liberté was an avid listener. He asked questions at all the right times and was suitably impressed by Petit-Gervais' worldliness. He himself had never gone farther than his summer pastures, and his sheep were far less interesting companions than Petit-Gervais' fellows. After they'd finished eating, Petit-Gervais pulled out his hurdy-gurdy and the marmot, rejuvenated by warmth and food, danced willingly to its melody. Jean-la-Liberté laughed with delight at the spectacle. Eventually the last light of the fire sputtered out, and the two boys retired, pressed together to conserve warmth on Jean-la-Liberté's pallet, Petit-Gervais' ragged blanket added to the top for extra insulation.

*

Petit-Gervais woke late the next morning. The winter sun had already been up for an hour, melting the night's frost coat. His head ached from the undiluted wine and his throat felt scratchy from sleep, but he rose anyway. Jean-la-Liberté was nowhere to be seen, and so Petit-Gervais busied himself with redoing his pack, pausing often to wipe his nose with the back of his hand.

Jean-la-Liberté came back inside just as Petit-Gervais was finishing his packing. "You're awake!" he said. Then, seeing the packed bag, "You're leaving already?"

"Won't get anywhere if I don't," Petit-Gervais said.

"There's another storm brewing," Jean-la-Liberté said, frowning. "You'll be far from anywhere when it hits."

"Not much that can be done about that," Petit-Gervais pointed out.

"You could stay here until it passes," Jean-la-Liberté suggested. "The house is sturdy enough to keep out the weather."

It was a tempting offer. Still. "There's likely another storm tomorrow too. I can't stay here forever."

Jean-la-Liberté shook his head confidently. "It won't rain tomorrow."

"How do you know that?"

"The sheep."

Petit-Gervais considered this. He wasn't so far removed from his roots that he disbelieved in animals' ability to divine the weather, nor so used to life on the road to turn down a roof when one was offered. "All right," he said. "I'll stay."

They spent the day idly. Jean-la-Liberté, who had already been to see his sheep, fiddled with a half finished wood carving, while Petit-Gervais, less hungry than usual, tried to teach his marmot new tricks with some of his uneaten bread. As Jean-la-Liberté had predicted, thunder started booming in early afternoon, and soon enough they heard the sound of another downpour.

"Does it always do this?" Petit-Gervais asked as the rain pounded down like pelting stones.

"Often enough," Jean-la-Liberté said. "Why, how does it rain in your country?"

Petit-Gervais started to answer, then stopped, struck. "You know," he said, "I don't remember." Then, because this seemed unsatisfactory, he added, "In Paris it stays grey and raining for days. It turns the soot to mud."

Jean-la-Liberté made a face. "That sounds unpleasant."

Petit-Gervais shrugged. "You get used to it."

They lapsed into silence, Jean-la-Liberté going back to his carving and Petit-Gervais staring at the fire. He hadn't thought much about what it would be like to go home. He'd known he would, of course, if his work didn't kill him or cripple him first, but it had always been an abstract thought. Home was a legend kept alive by boys who hadn't seen their villages since they were five or six, or by men who'd left for Paris at that same age and never gone back. Petit-Gervais carried the name of his village in his mind like a talisman, but it wasn't much more than a name. If he concentrated, he could recall his mother's face; he'd lost her voice long ago.

At last, Jean-la-Liberté broke the silence. "If I wasn't a shepherd, I'd go to Paris." From his tone, Petit-Gervais wasn't the only one whose thoughts had turned maudlin.

"What does being a shepherd have to do with it?" Petit-Gervais asked. "Surely there are others who could take your sheep."

"I have no other trade," Jean-la-Liberté said. "I can't very well herd a flock down the boulevards."

"There's plenty who'd pay to see that," Petit-Gervais said, grinning as he pictured it. Jean-la-Liberté didn't smile, and Petit-Gervais sobered. "You could learn a trade. You're too old for the chimneys, but you could apprentice to someone." He nodded at the piece of wood in Jean-la-Liberté's hands. "Carpenters take on boys your age."

Jean-la-Liberté snorted. "This? It's taken a year just to get this far. My teacher tried, but I have no talent for artisanry."

"Then what can you do?"

"I can mind sheep. I can read and write French. I can make cheese." He sounded disgusted with what, to Petit-Gervais, sounded like a perfectly reasonable skillset. Jean-la-Liberté grimaced when he said as much. "No one needs extra shepherds," he said. "Why would they take a foreigner when they have plenty of their own to mind their flocks?"

"Why leave here if you don't have to? You have a home, a livelihood, I'm sure you'll be able to find a wife without too much trouble when you want one. Are you restless?"

Jean-la-Liberté snorted. "I couldn't find a wife here," he said.

"Are all the girls around here really that ugly?"

"It's not that." Jean-la-Liberté sighed. "I suppose you might as well know. My teacher was a member of the Convention."

He spoke the word as though it ought to be self-explanatory, but Petit-Gervais only frowned. "Of... shepherds?"

Jean-la-Liberté stared at him. "This isn't a joking matter," he said, tone somewhere between severe and hurt.

"I'm not, but I also don't know what you're talking about. What Convention?"

"The Revolution? The Assembly of Citizens?"

Petit-Gervais shook his head.

Jean-la-Liberté seemed stunned. "But... you were in Paris!" he said.

"I told you, politics don't make any difference to me," Petit-Gervais said. He was beginning to regret pursuing this line of conversation.

"In 1789, as reckoned by the old calendar, the people rose up against tyranny," Jean-la-Liberté said. He sounded as though he were reciting a lesson learned by heart.

"I know that," Petit-Gervais said, although he wouldn't have been able to name the year, in any calendar. Jean-la-Liberté ignored him.

"Having freed themselves, the people formed their own government, headed by a Convention of elected citizens, who..."

"They killed the King!" Petit-Gervais interrupted, having finally figured out where this was going. "Your teacher was a King killer!"

"He wasn't!" Jean-la-Liberté snapped, his voice slipping back into its normal cadence. "Anyway, the King was plotting to overthrow the Republic!" He scowled. "I shouldn't have told you. You're no better than anyone else."

"Why did you tell me then?" Petit-Gervais demanded. His headache had intensified throughout the day rather than fading, and he had no patience to spare for Jean-la-Liberté's defensive streak. "How did you think I was going to react? And what does this have to do with not getting married?"

"Because everyone here also knows," Jean-la-Liberté said. "And they don't want anything to do with me."

This brought Petit-Gervais up short. "Oh."

"You understand now?" Jean-la-Liberté asked. He reminded Petit-Gervais of a threatened street cat, fur all puffed up to disguise how skinny it really was.

"I understand," he said. "But why do you expect anywhere else to be different? Will you change your name? It does give you away, you know."

"Of course I won't! But I thought maybe Paris remembered better. The peasants here don't know anything. Even the Bishop, the one everyone loves, he never came here until my teacher was dying, and all he did was insult us."

This, to Petit-Gervais, seemed about right for a Bishop, but that didn't feel like the right thing to say. He stayed silent.

"I thought Paris would be different. But you've just come from there, and you're just like the peasants."

"I am a peasant," Petit-Gervais said, mildly affronted. Then, because he was starting to like Jean-la-Liberté despite his prickliness -- and because Jean-la-Liberté was letting him stay in his home -- he added, "Although I'm not upset that he was a King killer. I was just surprised."

Jean-la-Liberté laughed a little. "He voted no," he said. "But thank you." They lapsed back into silence. When conversation started up again, it was about the weather.

#this fcking book though#achievement unlocked: completed piece of fiction#it's not a complete fic#but that's the tag#petit gervais

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dan Povenmire posted this and that prompted my partner and I to cast Rocky Horror from the adults of Phineas and Ferb, so here we go!

Doofenshmirtz is Frankenfurter obv

Linda and Lawrence are Brad and Janet and yes I do mean Linda is Brad and Lawrence is Janet thank you

Magenta will be played by Major Monogram, Columbia by Carl, and Riffraff by Perry (the platypus)

Eddie will be played by the members of Love Händel, yes all of them

Charlene, Dr. Doof's ex wife, is Dr. Scott

Background Unconventional Conventionists include Mrs. Garcia-Shapiro, the 'what, did you think it would fall right out of the sky?!' couple, Dr Diminutive, Aloyse von Roddenstein, and various O.W.C.A agents

And finally, the one you've been waiting for, Rocky is...

Norm!

Tell me I'm wrong I dare you

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

OH BOY YOU GOT LES MIS IN MY TOLKIEN! YOU GOT TOLKIEN IN MY LES MIS!

I would say that in Tolkien, for all that his characters live in a world crafted by songs and still affected by them, and that, for instance, Frodo and Sam talk about the songs that will be made about them in time to come, being a metaphor is something separate from being a person--metaphor and allusion and song can shape how someone is perceived and remembered, but it's not a part of a living person's identity, in a way that it very much is for Hugo.

And that a lot of Hugo's genius is in writing characters who are metaphors, who are doomed by the narrative at levels intrinsic to the worldbuilding, while still also being psychological real people with histories, and who deal having with the traits and histories the narrative requires of them in the way real people would.

What would it be like to be--not just in one's own conception, but at a supremely literal level--an empty vessel for Authority? What mental gymnastics would be required to maintain that emptiness, that dedication, in an age when actual Authority was being constantly shuffled and reassigned and reimagined? What combination of character and history would make a person choose that, and keep choosing it? What would it do to them? (Destroy them, first by inches, under the surface, and then all at once.)

Some characters are more or less aware of the metaphorical and allegorical shape of the world and their part in it (the Bishop, the Conventionist, Enjolras, Gavroche); others only get occasional glimpses (Jean Valjean, Eponine); Marius thinks he's in some other genre entirely; Cosette is so completely aware of it that she doesn't realize there's something there to be aware of, in a fish-not-seeing-water way. The narrator is more aware than the characters but not entirely omniscient--he has characterized the narrative as a struggle between Providence and Fatality and has a lot of thoughts on how the interplay between these forces makes history, and how they work in the lives of people, but he doesn't always know for certain which of them is at work in a particular event.

Tolkien is working through a whole range of narrative modes, from the low comic realism of the Shire to the mythic and epic; they sort of average out at the Romantic, but the book spends comparatively little time actually in that mode. While Hugo is a Romantic, and the Romantic is aspirational for him--the barricade fighters turn into epic heroes when they start losing and dying; falling into other narrative modes, as the entire denoument does, represents a loss.

And it's fascinating to me that the narrative shape of the world is so much more present, as a set of internal and external constraints that characters have to deal with, in the book more nominally set in the real world. Frodo and Sam can only speculate about the songs that will be made about them, and the difference between Bilbo's actual experience and the story he makes of it is a constant tension throughout The Hobbit and into LotR; but Hugo's wisest and luckiest characters are able--and in fact the signal of wisdom and blessedness is the ability--to see the story one is living at the moment, and to use that narrative momentum.

Meeting Tom Bombadil this morning, braced for impact, but like bro it’s fine it’s just the scop’s song from Beowulf (etc). My guy is just singing all the histories. He got to the start of the universe and the Hobbits were all :/ about it and stopped following which is annoying bc I want to know which versions he likes!!

Enjoyed Tom Bombadil vs Old Man Willow galdor battle.

I guess I should add that just bc I keep going “IS THAT— IS THAT FROM—“ doesn’t mean I think of the story as a series of straightforward references to early medieval stuff; it’s its own story from that storyworld and it’s just fun to recognise (or think I recognise) genre beats. Also I cannot shut up and I’m having the time of my life.

311 notes

·

View notes

Text

Brickclub 4.11.2 ‘Gavroche on the March‘

This chapter is all obscure prophesy; Hugo says so outright when he compares the four old women to the three witches in Macbeth.

And everyone is talking about dogs.

Gavroche is carrying his “dogless” (hammerless) pistol and complaining that the mouchards are dogs. We’ve seen the police as dogs many times before, but we haven’t had as much reason to worry about police spies as we’ll have soon. Identifying mouchards and dogs may also be foreshadowing Javert’s role--not “mouchards are dogs” but “the dog is going to be a mouchard.”

The old women--prophetic as Macbeth’s witches but even more ominous, because there are four--talk about how dogs and cats are enemies, and how there have been times the streets were so overrun with dogs it made the papers, but that cats’ fleas don’t bite people. We already know cats are revolutionaries and dogs are police (though both, we’ve learned, are able to turn into lions).

The old women, as Gavroche points out, should be on the side of the revolution--it would help them be less starving--but they’re not. One of them promises to see Gavroche guillotined (a VERY bad omen).

Instead of supporting any form of revolution, they talk about their favorite former heirs to the throne who died before they could rule: the king of Rome (Napoleon’s son), the duc de Bordeaux (son of the assassinated duc de Barry), and Louis XVII (son of Louis XVI; this was the boy who died in prison during the revolution.)

Some Things are going on here.

1) We’re looking at the very poor sympathizing with royalty over what would seem like their own best interests. These women seem dissatisfied with the government they have, but instead of concluding it’s a problem with monarchy, they latch onto the princes who didn’t last long enough to do anything wrong.

2) I sense another dig at Napoleon III. Their hope that one of these deposed lines of succession will reemerge is realized years after this, with horrible results. They are prophesying Napoleon III.

3) We learned from the Conventionist to identify the death of the innocent child Louis XVII by the revolution with the all the innocent children the monarchy killed just as horribly and tragically. The witches are mourning the one, but the other is standing right in front of them. They didn’t get the message.

4) They’re talking in portents about children with great birthrights killed before they could attain them. Gavroche isn’t a prince, but he is Paris, and potential, and revolution. He’s Macbeth passing by the witches, and they’re telling him exactly what he’s about to lose.

And then, finally, the chapter ends with our final dog, which is simply a real dog, skinny and starving, that happens to be passing by. And Gavroche, who just helped up a fallen National Guardsman, pities the dog too.

He learned the Conventionist’s lesson of separating compassion from social station and political faction, even if the rest of the world hasn’t.

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Brickclub 4.11.5, “The Old Man”

Once again, Gavroche is singing and I have no idea what to make of it--except that it seems ominous. It’s hard to follow whether all the animal references refer to the same animal, but it sounds like it’s about a tiger eating, or at least glad at the prospect of eating, two drunken sparrows, who either become or are called wolves while intoxicated. This... seems like a bad omen.

The chorus of the song lists places--two customs tollgates (Passy and Pantin, which is argot for Paris), and two things I think are villages? (Chatou and Meudon)--with nonsense rhymes and the refrain “I have only one God, one king, one sou, one boot.”

The king is also interesting--Gavroche has sung about kings before, but it’s surprising to hear him owning one, even in a fairly nonsensical song.

I really don’t know what to do with this song; if anyone has ideas or links I’ve love to see them.

I also cannot find any reference to the Rue Bassompiere that Enjolras & co. escape down. The Boulevard Bourdon, where the Amis are when the dragoons charge, is the portion of the Boulevard that continues south of the Elephant of the Bastille, next to the canal; the Rue Lesdiguières, where they meet Mabeuf, is parallel to it with no intervening parallel streets, and the connection between them is the end of the Rue de la Cerisaye. The 1830 map I’m getting all of this from does not list a Rue Bassompiere anywhere in the key--there is a Rue Basse-Saint-Pierre, which would have been pronounced as Bassompiere, but it’s all the way over by the Champs-Elysées. Gavroche’s progress down from Ménilmonant follows the map, but as soon as the Amis appear the geography starts getting weird--in the next couple of chapters, they’re somehow going to miss Saint-Merry despite going right past it, and the Rue de la Chanvrerie where they build the barricade is Hugo’s own spelling for what the map calls the Rue de la Chanverrie and Hugo will insist was originally the Rue de la Champverrerie.

And then there’s Mabeuf.

He’s weaving in the street like a drunken man, not seeing where he’s going. Courfeyrac tells him they’re going to fight, there’s going to be cannon-fire and saber cuts, and Mabeuf just says “Good.” And then--after establishing that they’re going to die--he asks where they’re going. Courfeyrac says they’re going to overthrow the government, and Mabeuf says “Good,” and his face gets blanker, but “Suddenly, his step became firm.”

The rumor spreads that he’s a Conventionist, an old regicide. He’s the farthest thing from it--but he’s found his way to the Revolution.

I am always surprised that we learn in passing that Courfeyrac has accompanied Marius to Mabeuf’s many times. In Marius’s POV, we never heard anything about this--his two friends were always contrasted with each other and kept quite separate. It’s one of a lot of examples where the narrator makes it sound like Marius hasn’t spoken to a living human being in months and then casually drops in a perfectly normal exchange with one of the Amis, and it really makes me question the reliability of everything else we see solely or mostly through Marius’s eyes--he’s so depressed and checked out that in his own POV, he’s completely alone and other people (besides Cosette) just aren’t making an impression; but clearly at least until the last few months, when he started to pull away from everyone including Mabeuf, he was still managing to keep up at least some social ties.

17 notes

·

View notes

Note

Joly for the ask thing!

FOR SCIENCE :D

First impression

wow he’s just a total sweetheart??

Impression now

yes, definitely a total sweetheart!

Favorite moment

**standing in the middle of a battle zone, having just lost two of his dearest friends, hungry and thirsty and with no certainty about what’s coming ** “ LOOK A KITTY, obviously God is real and also Good if there are cats”

#relatable tbh

Idea for a story

…If I could fic, which I cannot, I would love to do something with how he and Bahorel got to apparently being gossip-and-feels buddies. They’re so obviously different, but they get one of the bigger bits of conversation that doesn’t involve Grantaire! when and how did they Click? And how illegal was what they were doing at the time? :D

Unpopular opinion

Not so much an Unpopular thing as just one that is maybe uncommon..?

There’s this line from the Conventionist when he’s talking with Myriel:

“L’homme ne doit être gouverne que par la science.”“Et la conscience”, ajouta la eveque.“C’est la même chose. La conscience, c’est la quantité de science innée que nous avons en nous.”

Man must be governed by science; Conscience is the amount of science innate within us.

From that lens, what Enjolras sees as Joly’s gift of science takes on a much deeper resonance–and one that works with what we see of him on-page , too. Joly’s focus on science all comes with a human-scale focus; no doubt he can get excited about trains and telegraphs too , but the science that occupies him is all on a much more intimate scale. It may go off on what we now think of as wacky tangents, but none of Joly’s experiments that we’re told of are harmful –much less than a lot of the standard medicine of his day, in fact. It’s all based on being immediately aware of surrounding environment and circumstance. And it’s all about human health and comfort, on a personal, workable scale.

Keeping an eye on your own weakness, treating it with compassion and an eye to how external factors are affecting it, while always being open to trying new things to be better,healthier (and of course, always remembering that You Are Mortal)–does that not sound like an approach Bishop Myriel might recognize? Even to seeing the goodness of God in the presence of small, easily overlooked creatures?

Joly’s a goofy good-natured nerd, and a lot about him is easy to read as silly– he is silly! But like the Amis as a whole, I think it’s a mistake to think he’s just silly. His cheerful, optimistic involvement is a promise that the Amis would never have lost their conscience in cold absolutism–would never have forgotten that innate science in themselves. No wonder Enjolras thinks it’s Joly’s greatest gift.

Favorite relationship

With Bossuet, obviously! I wish we saw more of them, but I love that their Dynamic is so clear from the little we do see–the constantly high-energy fussbird who wants to poke at everything and the laid-back-to-the-point-of-becoming-a-mural guy, Goofballs United:D. (Granted Joly is also part of one of one of the few heteromances in the book that seem at all potentially good though; I really appreciate that even when he’s fighting with Musichetta he has nothing bad to say about her, he’s just sad about the fight– I just don’t see enough of Musichetta for it match the onpage relationship with Legle.) Either way , though, what a good bean.

Favorite headcanon

aah I have a lot– but the one that I am always loyal to and thus I suppose My Favorite is that he is chronically ill, but with something like allergies that happens in Episodes and which no one in his era has yet figured out, so he sometimes gets obviously super sick and then…it Goes Away and no one knows why. The social and personal issues attending an undiagnosed Mystery Condition (and which yes, I am unfortunately familiar with) are things that I think play into Joly’s character as we’re shown it very well.

#Joly talk#this gets kinda tinhats in the middle sorry XD#thank you!#firing the headcanons#Hey Nonny Nonny#answereds

22 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“The bishop realized that time was pressing. He had come as a priest; from extreme coldness he had grown gradually to extreme emotion; he glanced at those closed eyes, he took that old, wrinkled, icy hand and drew close to the dying man.

“This is the hour of God. Do you not think it would be sad if we had met in vain?”

The conventionist reopened his eyes. Calm was imprinted on his face, already touched with shadow.

“Monsieur Bishop,” he said with a deliberation that came perhaps still more from the dignity of his soul than from the waning of his strength, “I have spent my life in meditation, study, and contemplation. I was sixty years old when my country called me and ordered me to take part in her affairs. I obeyed. There were abuses, I fought them; there were tyrannies, I destroyed them; there were rights and principles, I proclaimed and professed them. The soil was invaded, I defended it; France was threatened, I offered her my breast. I was not rich; I am poor. I was one of the masters of the state, the vaults of the bank were piled with coins, so we had to strengthen the walls or they would have fallen under the weight of gold and silver; I dined in the Rue de l’Arbec-Sec at twenty-two sous for the meal. I succored the oppressed, I solaced the suffering. True, I tore the drapery from the altar; but it was to dress the wounds of the country. I have always supported the forward march of humanity toward the light, and I have sometimes resisted a progress that lacked pity. On occasion, I have protected my own adversaries, your friends. At Peteghem in Flanders, at the very spot where the Merovingian kings had their summer palace, there is a monastery of Urbanists, the Abbey of Sainte Claire in Beaulieu, which I saved in 1793; I did my duty according to my strength, and what good I could. After that I was hunted, hounded, pursued, persecuted, slandered, railed at, spit upon, cursed, banished...”

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

1.1.11

I like that the discussion of what the bishop’s political views are like, immediately follows from the meeting with the Conventionist. And in this chapter we are confronted with the opulence of Napoleon and his convention of bishops which is shown in stark contrast to the bishop’s humble life. Hugo is taking a swipe at the opulence of great men and suggesting that the bishop should be poor if he lives near and cares about the poor. I love the bishop’s very visible annoyance about/with Napoleon from 1813 to 1815. I do wonder whether the bishop’s feelings about being a Royalist and Hugo spending some time dwelling on it, is more to talk about his own past as a Royalist and as Bonapartist, and try to maybe justify it, like he does about 1848 later. It feels very much in that vein. Also, here in these chapters and in most of the book, Hugo’s foremost concern isn’t politics/political issues but social issues, which he feels are more important for progress which is interesting, I wonder if you can separate the politics from progress.

I find it interesting that Hugo writing about Napoleon after the fact seems to invoke Providence all the more, with his line about ‘Waterloo seems to be lying in wait’ for Napoleon line and since in the actual digression, Hugo also points to some aspect of the defeat being due to Providence/weather, I wonder how much he believes in it and uses it throughout this book.

Although now I can’t help wondering if underneath his ‘if you are not a persistent critic during a great man’s success, you should remain silent during times of a man's downfall,’ may also be a jab at Louis Napoleon III or people not criticising NIII as vocally as he was, as Hugo had been a strong opponent of his for quite some time now. Admittedly that may be a stretch to make here, but Hugo’s talk of great men and success always reminds me of his very valid feud with NIII.

Nevertheless, we know that the bishop has not changed his politics radically after the meeting with Conventionist G, I would like to know what he thought, I feel that he liked G individually, but he still has not fully confronted what the French Revolution means to him, because it is personally associated with a time in his life that he may not wish to return to. The only after effect we can see is that he does try to be even kinder to everyone- and probably almost reaches towards perfection (he helps a man who was ruined because he is loyal towards Napoleon during Louis XVIII’s time). His being more or less neutral in his political opinions is written as a failing/flaw here, but also as an aged bishop in a small town, I can hardly hold him accountable, he does try to help in whichever way he is able to, and he helps anyone regardless of their politics.

I also love his persistent sassiness directed towards Napoleon, which even the people have come to accept, and I love the throwback to the comparisons of great man and good man in the previous chapters, Napoleon with his deeds of war and as an Emperor may have caused people to admire him, (Hugo uses the word flock for them, the people of the village are perhaps admiring Napoleon out of their simplicity) but they know the bishop and love him, which makes all the difference in the world, to Hugo as well as to us as readers.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

I’m still trying to comprehend the last paragraph of today’s chapter:

“This is what floats up confusedly, pell-mell, for the year 1817, and is now forgotten. History neglects nearly all these particulars, and cannot do otherwise; the infinity would overwhelm it. Nevertheless, these details, which are wrongly called trivial,—there are no trivial facts in humanity, nor little leaves in vegetation,—are useful. It is of the physiognomy of the years that the physiognomy of the centuries is composed. In this year of 1817 four young Parisians arranged “a fine farce.””

Aside from the more blatant transition/foreshadowing of the last sentence, this whole chapter seems to purely be context for 1817. And to an extent, it is. These are the kinds of events the characters would have been thinking about. At the same time, I’m interested in Hugo’s assertion that while “ History neglects nearly all these particulars,” they are not “trivial.” So much of this book is based on that philosophy: Hugo rarely spares any details about characters’ lives (we know so much about the bishop’s finances); he concentrates on those neglected by history (the poor, the outcast); he stresses the value of small moments (one man’s kindness transforming Valjean).

The positioning of this chapter in light of this, then, seems crucial. After reading about Valjean’s crisis, the reader may suspect that we’re concentrating on his story because he’s somehow exceptional. But in emphasizing that nothing is “trivial” and that all details are “useful,” he’s reminding us that his intent isn’t to show us a unique story, but to rather illuminate the lives of ordinary people. Perhaps their stories are extraordinary in some ways, but only because each person is capable of extraordinary acts of compassion.

I’m also curious about the pass Hugo seems to give history when saying that it neglects these specifics because “the infinity would overwhelm it.” Although he says this, he’s just presented us with the exact opposite of that philosophy: he’s overwhelmed us with the variety of “headlines” present in a single year.

I don’t know how to fully articulate this, but something about this section reminds me of the Conventionist saying that while it is a tragedy that royal/noble children died during the French Revolution, poor children need to be grieved more because they’re more likely to be forgotten. Perhaps it’s simply because that chapter was really memorable and any reference to what’s forgotten or neglected in this book makes me think of that, but it does feel like Hugo’s adopting a similar attitude towards events in 1817. At the same time, all of these events were considered noteworthy in that year. It’s only with distance that they’ve come to be forgotten, unlike the children mentioned by the Conventionist, who were ignored by broader historical narratives from the beginning.

#les mis letters#lm 1.3.1#1817#I'm very confused by this chapter#but that's OK#the plot will be back soon#and hopefully the next digression will be friendlier

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

BrickClub 1.1.10

It’s super super interesting to me that Myriel, for all he is aware of injustice and makes himself poor to help people and gets snarky at rich people who don’t care that others aren’t so lucky, is still horrified by the fact that there even ARE people who think something like the Revolution could be justified. Such an odd thing, to want to help the poor and still be a royalist, but it would be even more odd, I guess, to be a Bishop and question the divine right of kings, and furthermore Myriel had to flee from the Revolution, so there’s that.

But Myriel does go to G, because he is dying. And then he doesn’t shake his hand, and then he doesn’t know what to do with any of what G says, and we are repeatedly told that he doesn’t know what he’s feeling except, from a certain point onward, A Lot. And he doesn’t know how to behave at all, and he’s kind of rude? And then. Myriel treats the rich and the poor the same, but when someone treats him merely with the respect afforded to any stranger, he has a whole situation about it.

I feel like he sort of. Externalizes the crisis he’s having? He abruptly starts asking questions and being accusatory in a way that I’m pretty sure he would otherwise not be, because he wants someone else to solve this for him, this entire moral issue of “I think everything this guy has ever done is deeply wrong, but I also know everyone deserves my attention/compassion/etc.” And he gets answers! G is dying and still manages to argue with the Bishop and be convincing enough that Myriel is changed at least a little.

“What have you come to ask of me?”

“Your blessing.”

HOO BOY.

(Another thing: Myriel never tries to argue that he isn’t rich, that he gives away all that money, that he doesn’t live in a palace. That’s a little way into the conversation, of course, but still. He doesn’t try to defend himself, he only argues insofar as he thinks there is fault with what G believes and has done.)

I’m so glad this is a chapter where I don’t have to disagree with Hugo. Yay for the good opinions reappearing...? I would love to have insightful commentary about what the conventionist says, but all I have is exclamation marks and many emotions. There’s another line that repeats the preface, I think? And the passage with the “I will weep for the children of kings with you, if you will weep with me for the children of the people.” That entire passage always gets me. Every time.

Anyway also I cried.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Listen I've got some of The Symptoms so I'm being quarantined inside our quarantine. It's a good thing I got my old parents' home office as a buffer from the rest of the house (from way back when they worked from home). So I am stuck inside, with all my art suplies and a bad wifi signal that can't handle netflix, which means I guess I have to draw now

(EDIT: oh and BTW the second one is based on Rosso Fiorentino's Descent From The Cross, it's a beautiful painting if you want to check it out)

It's interesting how these two chapters are divided into acts. The Flag is taken as a drama in itself.

Mabeuf was sitting behind the counter on the ground floor of the Corinth. Courf and others kept checking up on him, telling him it was dangerous, asking him to leave, but he was dazed. He didn't hear them.

When the grapeshot stopped he came outside, and when Enjolras asked for volunteers he approached and grabbed the flag. He climbed up the steps they had made from paving stones while people kept crying "the conventionist!" (the insurgents assumed he is an old conventionist, and as someone who has seen very old people in protests, that's very real. You assume older people are veterans from the movements that came before. Most of the time they're just people but in the moment you really assume).

He cried "Vive la révolution! Vive la république! Fraternity! Equality! And death!". The voice asked again "Who goes there?" He repeated "Vive la république!" "Fire!"

-

So he fell back, arms wide like a cross. Enjolras was impressed with "these regicides" and Courf pulled him aside to explain Père Mabeuf isn't a regicide, just a brave blockhead. "Blockhead and Brutus heart." Enjolras responds. (Happy late ides of March!). This is the line that made me cry yay!

Enjolras approached and told everyone about the great example this patriarch had given them. "Now let us protect his corpse, let everyone defend this old man dead as he would defend his father living, and let his presence among us make the barricade impregnable!". He kissed Mabeuf on the forehead. Delicately removed his red-stained coat and said to all of them: "There is our flag now."

Like I said in the last chapter: Enjolras already knew this would happen, someone would die to raise the flag up. He knew he was making a martyr because he understands what a revolution needs. He executed a murderer without hesitation and he made a martyr. He has also commended Rousseau for abandoning all his children in the name of focusing on the cause before. You may call this selfish and a bit cynical and you would be right. If I knew an Enjolras in my life I would slap him. But Enjolras is as Enjolras does. He Loves his friends. He Loves Patria. He loves the Revolution and he will commit any and all sacrifices he needs to fullfil what he thinks is his destiny. Doubt is not a factor in his mind. The reason he was put on this Earth is to forward mankind, even if that means he will become the executioner and make the decisions that will morally "taint" him. He thinks that he is a necessary evil to bring humanity happiness and that he has no place in a happy world, like he said in the chapter about Le Cabuc. If he survives he'll become like the conventionist in the first volume, alone and an outcast. But he will know he did what he did for the love of humanity and he will take refuge in knowing (at least he thinks so) that he was doing what is right.

Sketching Les Mis Chapter 4.14.2 - The Flag: Act Two

214 notes

·

View notes

Note

what if you do every question with the number 1 in it?

U might be kidding but I am gonna do all of them watch

1) I have no clue who I last held hands with. I don’t hold hands often (ever)10) The last person I had a deep conversation with was my older brother11) The most recent text I sent says “Oh. Yeah 100%, as already stated I have no self control”

12) Top 5 fav songs rn are: Michael in the Bathroom from Be More Chill, The Squip Song from Be More Chill, The Smartphone Hour from Be More Chill, Do You Wanna Ride from Be More Chill, and The Pants Song from Be More Chill. I have no chill.13) I do like it when people play with my hair, yeah. 14) In actuality I don’t believe in miracles but luck is a thing? Like, rolling a die. It’s random. Ur lucky…?15) A good thing that happened this summer was… I got to work on a farm for three weeks and it was in a hella pretty place and it was awesome.16) I’ve never kissed someone so yes I would kiss no one again.17) I do think there is life on other planets18) No I don’t talk to my first crush19) I don’t know if I like bubble baths… Probably not.21) Bad habits? Biting my nails. Being a moron.31) Yeah my hair is long enough for a ponytail41) I think the vast majority of people deserve a second chance… Not… Everyone.51) Yes I’ve wished I were someone else lol61) I’ve never been expelled or suspended I’m a good child71) I’m craving going home. I’ve been gone over a month :\ also peanut butter81) favorite TV show ever is atla, rn it’s Brooklyn 9991) There’s always someone I wanna punch in the face100) I’m feeling tired and also homesick101) I type… Fastish?102) I regret lots of shit from my past, yeah!103) My spelling is god awful104) Yes I miss people from my past.105) Yeah I’ve been to a bonfire party I think..?106) Don’t think I’ve ever broken someone’s heart107) Yes I’ve been on a horse. And fallen off.108) Right now I shouldn’t really be doing anything lol109) yeah my older brother is being irritating110) I don’t think I’ve ever liked someone so much it hurts??? Maybe. Eh probably111) I don’t think I have trust issues112) The last person I cried in front of? A bunch of strangers on a public bus lmao113) My nickname is Talia?114) I am currently out of my state, so yeah115) Yeah I play the Wii. Not often116) No I’m not listening to music right now117) I like chicken noodle soup, yes118) I like Chinese food, yes119) Les Miserables is my favorite book120) I’m not afraid if the dark121)I can be mean, lol122) cheating isn’t ok. 123) I, personally, could never keep white shoes clean.124) I don’t believe in love at first sight.125) true love? Don’t know what that means lol126) yes, I’m currently very bored127) wind turbines make me happy128) I don’t really want to change my name, nah.129) my zodiac sign is Leo130) I despise Subway131) if my “best friend of the opposite sex” liked me, I’d remind them that nothing will ever happen between us lmao132) REPEATED QUESTION133) Favorite lyrics right now? Aaaa idk lol134) I could hypothetically count to one million. Not now. I won’t…135) I’ve told some p dumb lies136) I sleep with my door closed. Security comes first137) I’m 5'7" I think? Maybe 8?138) I got curlyish hair139) Brown hair, yo140) Summer 300%. Winter’s a bitch.141) I like day. But also night. Idk.142) June is my fav month143) I only eat chicken and fish (in terms of meat) so I’m almost a vegetarian lmao144) milk chocolate145) coffee over tea146) today was… An ok day147) Snickers over Mars148) fav quote? “When I’m dead, just throw me in the trash”-Frank Reynolds.149) I don’t really believe in ghosts…?150)“it was the turn off the conventionist to be haughty and the bishop to be humble.” The first line on the 42nd page of the nearest book to me!

1 note

·

View note