#we were not meant to interpret every thing via words that are two centuries old

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Tags via @sleepythyme

Idk if this was an actual question or just a rant but iirc the founding fathers did not put so many direct stipulations that would apply towards prohibiting criminals in office because

1) They believed that if the time occurred for a change of rules or needed clarification, we would simply do so, and

2) They did not think there would be a time in our country where a criminal could ever get that far, nor did they think anyone in their right mind would elect such a person

A majority of the founding fathers’ oversight was that they genuinely could not fathom a nation that would allow such corruption running amok because it was still fresh on their minds why that was a Bad Thing™️. Many of them weren’t that insightful (though a few did consider that there could be problems in the future, they just hoped we would take care of it and uh…yeah)

I like how indicting Trump did fuck all at the end. Functional democracy

#this is not in defense of them btw#the founding fathers#were idiots through and through#they just happened to be smart for their time#and made *some* good decisions#this is also why originalism is stupid and bad#we were not meant to interpret every thing via words that are two centuries old#it was meant to be an every transformative document#not a static bible of nationalist dogma#just American tingz#civics lesson

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

Folk the Author

Hi all, I’m stealing a little time from moving in to revisit my folktale metas before hiatus is over and my classes start up again (I accidentally signed up for a Maymester this summer and did a semester of coursework in six weeks and am mentally still spongy. Hard not to try to apply Bloom’s taxonomy to Supernatural watching, like where do I fall, am I a lower-order watcher, how can I put Bloom’s descriptors into a lesson plan about Supernatural, help.)

Here’s a quick discussion of the season 14 finale and some thoughts about where folklore as a theme has taken us In Light of New Information™. If you haven’t read the previous posts on this topic, they’re tagged under “the folklore of supernatural.” Moriah lends itself better to deconstructivist and postmodernist readings, but I’m gonna try to dig some folklore themes outa that sumbitch so here we go.

I’ve been talking about folklore a lot this season, but let me recap the different kinds of “folk tales” I’ve been thinking about. The first, purest form is the oral folk tale, conceived completely as spoken word and delivered via performance for an audience; by its nature it is ephemeral, exists in the moment, and persists only in the memories of those there when it was performed. Then we have stories that are transcribed during their telling, a la the Brothers Grimm. Was something lost when the stories were written down? Facial expressions, strategic pauses, laughter or gasps from the audience, that would bring drama or pathos or hilarity to the tale? Then we have literary fairy tales, stories like “Sun, Moon, and Talia,” “Beauty and the Beast” and “The Nightingale,” which are constructed with the architecture of folklore but are written works-- even if it was based on an oral tale, such as SM&T, the structure and prose is that meant for a reader. Oftentimes, “folk” themes are scrubbed (or are completely retooled) as these are meant for an aristocratic or at least literate audience. Think about how the wolf eating Red Riding Hood and Grandma is often Sanitized for Your Protection by having the wolf knock Grandma unconscious or something in retellings of the story. (In case you don’t know, the wolf eats Grandmother and eventually Red Riding Hood, too, and a woodcutter comes by, hears their cries, and cuts them out of the wolf’s belly.) Another kind of folklore exists that I’ve touched on, that of written literature that reentered oral tradition-- an example of this kind is the Grimm Brothers’ Little Briar Rose, ostensibly collected as an oral folktale but inspired heavily by the aforementioned “Sleeping Beauty in the Woods” by Charles Perrault.

This interplay between folk/oral tradition and the literary one is set up directly by the ending of Supernatural’s season 14. We’ve known Chuck to be a writer ever since his entrance into the series in season 5 but he was framed as a prophet of the Lord, a mere recorder of the Winchesters’ actions, and it was assumed at the time that his works were reflections of the visions he received as prophecy. His narration and disappearance in Swan Song placed all of that in question, but there was never anything in canon that did more than hint at his larger role.

Knowing now that Chuck is God/The Author (instead of just “the author” as he has been introduced as, like in Fan Fiction) quadruple-charges the folk/auteur dynamic. Chuck is pitting himself as the chief architect of the world’s narrative against his own characters, who he had essentially allowed to run away with the plot. Another way of looking at this is through the lens of postmodernist theory, where the author becomes irrelevant once the work is published, and interpretations are the sole domain of the reader/audience-- Chuck versus TFW becomes a grand collision between old-school literary theory versus “death of the author.” (This has huge implications for meta writers and the problem with taking a break from fandom is that I don’t know what was discussed about this, but it’s exciting.) I’m still parsing the interplay between God the Author as both auteur and audience, the actual TV audience (us!), and the characters-- which are now all characters! and authors! and audiences! The deconstructivist reading writes itself.

But back to the program. This sudden rivalry between God and the Winchester clan can, on another level, be seen as the tension between a narrative constructed by a literary writer versus the motifs and characters that make up the folk tradition. What I want to talk about, then, is a reading of the series post- season 5 as folklore, and Chuck as a writer who is trying to bend the ending of the tale for his own gratification.

I’ve spoken a bit before about the tale we know generally as Sleeping Beauty, as it made its way from folklore into the literary realm and back into folklore. At some point, an “early” version of the story was written down by a Neapolitan writer named Giambattista Basile in the seventeenth century as “Sun, Moon, and Talia,” and officially became a literary fairy tale. How far removed it is from the oral tradition is anyone’s guess, I think. Anyway, Charles Perrault, a French writer decades later, reworked the tale into “The Sleeping Beauty in the Wood,” and then this story made its way into the hands of storytellers in Germany and reemerged as the “folktale” “Little Brier Rose” and was harvested by the Brothers Grimm in the nineteenth century, and when they entered it into the written record it once more became a literary fairy tale. It’s a good metaphor for what is happening in 14x20. Chuck engineered Dean’s and Sam’s births and possibly also all of their lives’ events up to 5x22 Swan Song; it’s not really clear when he stepped out or to what extent he has remained involved. This changes the angels’ allegation that God has been gone for centuries-- he’s just been writing anonymously and mailing in the drafts. We’ve seen the power of writing in Meta Fiction when Metatron powered his own scribing with the Angel Tablet, which gave him god-like powers-- but then, as now, our folk heroes snatched their victories out of the typewriter of doom and changed the course of events... that was a ridiculous metaphor but I’m only a little sorry.

What we are being led to believe now, then, is that Chuck set up (“wrote”) the events leading up to the Apocalypse, and Sam and Dean and Castiel were turned loose in the plot and ended up acting as chaos agents, runaway literary devices as it were, and Chuck has been very amused to see what they’ve done with the shit that he’s slung at them. “You’re my favorite show!” he exclaims, bending the author/character relationship in Pirandellic ways, almost to the breaking point. However, it is clear that Dean, Sam, and (probably) Castiel still have free will and use it to deny Chuck his tragic ending-- that of Dean killing Jack-- as Sam instead tries to kill God himself.

“Alright. Story’s over. Welcome to the end,” Chuck says as he unleashes Hell and calls up a zombie horde to attack Sam, Dean, and Castiel; it is revealed to the audience that the ghosts which the Winchesters have dealt with through the years are returning, their own endings coming undone. This is a return to their roots, as their very first case in the Pilot was a ghost, so while it’s not clear yet if every monster has been reset, this is a way of the story to circle around back to the beginning. This is both a literary device and a folk one, as folk tales are almost universally about getting past recursions and to a new ending, such as the two times the little pigs’ houses failed until the third pig’s house is strong enough to withstand the wolf, and in literary stories the circular narrative features in novels like Huckleberry Finn, where the entrance into the story of Tom Sawyer reframes the entire plot, or Moby Dick where the ending makes sense of just about all the strange things that happened as a means to save Ishmael’s life.

Folk tale plots, where the monsters are handily defeated by an unlikely hero or heroine and the innocent go back to their lives, are now being confiscated by an author who is actively rewriting the stories to suit his own desires. As I’ve discussed before, most of TFW 2.0 are framed this season as folk characters, and we know since fairly early days that they had gone beyond even Choose Your Own Adventure™. (Sam is a special case of an author insert or a character running away with the story that I hope to talk about in another post, let’s just say his role has been very meta...)

I’ve been fascinated by the idea that the act of recording a story changes it since I was young, and I’ll link a couple of things to think about now. When I was little, and I’ve mentioned this before, I lived in Tennessee and was fortunate enough to go several times to the National Storytelling Festival in Jonesborough, where I learned that experiencing a story face-to-face is different than listening to the recording in a very important way. I listened live to a terrifying tale called “Tilly,” conveyed by the master storyteller the late great Jackie Torrence. It is a story that speaks brilliantly to the hearts and backbones of younger children. Later, we heard her tell W. W. Jacobs’ “The Monkey’s Paw” by on a recording of a live storytelling session (“Graveyard Tales” 1984,) from that same festival, and I learned, sitting in a darkened living room with parents and siblings seemingly as terrified as I was, that even when a storyteller’s aim is to frighten, there is something comforting and grounding about having the storyteller in front of you, guiding you through the story they are telling, and somehow the story from the record in the record player was infinitely more scary for having no one there at all in the room who knew how the story was going to end. I think that’s where we’re going to be at the premiere of season 15. We have an author who has undone the folktales that Sam and Dean have worked all their lives to craft, ones where the monster is slain and the good townsfolk get to go about their lives once more, and he’s bending it to his will instead of allowing the “folk” endings that we’ve come to expect.

One more thought about “writers” that comes from this episode. I’ve been upset for a couple of seasons now that we’re not hollering more about Dabb and Singer (and possibly Ross-Leming) dispensing half-truths and bogus assertions-- like Singer’s claim that we would “never guess” who was going to possess Dean, when meta writers excitedly postulated that it would be one of the Michaels, and this season Dabb stating that Dean wasn’t secretly possessed when it was clear that there was still a tether to AU!Michael who had been wiretapping him all along so that Dean might as well have been secretly possessed. It is a ham-fisted way of managing our expectations so that ostensibly the gotcha in that episode would still be a surprise. Spirit of honesty, in practicality it’s just short of prevaricating. It’s the kind of thing the writers should probably just keep mum about, imho. And then in the season 15 finale, Castiel (sometimes a liar himself but is nonetheless held up in this episode to be The Voice Of Truth) says bluntly, “Writers lie.” (It’s easy to forget about Metatron uploading “all” of human media into his head, so there is no better authority about fiction in the room than he.) In an abstract sense, yes, a writer creates what are essentially lies-- fictions, tall tales, things that never really happened to characters that don’t really exist-- but here we’re faced with the possibility that we can’t trust them to be truthful outside of their own fictions, either. I found Dabb’s tweets throughout the season to be cryptic but in many ways very spot-on to how they related to the episode he was tweeting about, but I think we’ve been warned. About the writers: Supernatural is always about the “twist” at the end, and in this way they’re professional liars-- they lead us in one direction, or in no direction, as Sam and Dean try to figure out the MOTW or the angelic double-cross or whatever. And then yikes it’s a ghost or Metatron is the homeless guy or something. Steve Yockey leaving the writer’s room has left me gutted, although I have high hopes for Jeremy Adams, who has been a writer for Scooby Doo, and is thus probably quite clever at writing episodes with a “reveal” at the end, and which in the Scoobyverse are always satisfying-- like, that’s the requirement, that [redacted] actually being the Miner Forty Niner is, like, yeah, gooood stuff. I hope that we’ll be thanking the authors for the experience they’re taking us on with their weekly fabrications instead of screaming that we’ve been sold a bill of goods about any given theme in season 15. So mote it be lol. Anyways, there’s my ruminations on the writers as a bonus.

I think that exploring the season through the lens of folklore paid off in spades in the finale as it set up a “folk/author” clash that will be interesting to watch going forwards. I don’t know that this theme will carry on, and make no predictions if it does, that’s not what themes in a serial text do necessarily. I mean, clearly, we’ve got some author/character shenanigans to look forward to, but whether we’ll be dealing with more folklore, whether the theme will transmute to literature or even absurdism, or to reader-as-author is something I’d like to see but can only hope for. I think it will be a wild ride and while I see a lot of Gloom ‘N Doom around this last season, I’m really looking forward to it. For me, this season’s writers have been providing that yeah gooood stuff so far, and remember how subtext (and btw I don’t mean destiel subtext) in a serial text works? I think these guys are all really good at delivering subtext (well, most of them) and we’ll have a surprising and satisfying twenty episodes.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Green Knight Ending Explained

https://ift.tt/3ig4m5i

This article contains The Green Knight spoilers.

A man who would be king lies crouched, cowering on his hands and knees. It is the day he’s feared all year and, seemingly, the hour of his death. And yet, within this moment, after he’s seen his life flash before his eyes, Dev Patel’s Gawain has never appeared taller or more free from the terror of self-doubt. The character is still not technically a knight, but as he throws away a magical green sash and asks his executioner, a Green Knight made of bark and flower, to do his worst, Gawain truly has achieved the greatness he’s striven for in King Arthur’s shadow.

This is why Ralph Ineson’s imposing emerald warrior leans down and whispers like a kindly grandfather his approval. That’ll do, Gawain, that’ll do. “Now little knight,” he adds, “off with your head.”

I’m sure that jarring and abrupt final line has left many an audience shocked and maybe even a bit confused. After all that, did the vision Gawain had of himself assuming Arthur’s throne come to naught? And did the flawed hero we’ve watched for two hours only achieve true chivalric virtue in the same minute as his death, which the Green Knight promises is about to occur off-screen? Also why did any of this happen?

There is much to unpack about David Lowery’s poignant and often surreal interpretation of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, but there is sound reason for why the absolute happiest ending for poor Gawain is the one that concludes with his swift decapitation.

The Ending of the Original Green Knight Poem

Perhaps the most striking thing about the ending of The Green Knight is how it both complements and changes the resolution of the 14th century epic poem upon which it’s based. Tackling a ballad that profoundly affected him when he first read it as a teenager, and even more so when he chose it to be the template for a film, Lowery is unsurprisingly close to many of the smallest details in the 800-year-old story.

For instance, the first line of dialogue spoken by a character in the film—when Alicia Vikander’s Essel says “Praise the Lord, Jesus Christ was born”—is taken from how the anonymous author describes Gawain’s first thoughts every morning he’s awakened. However, in Lowery’s The Green Knight, that awakening occurs on the actual Christmas morning and the person who speaks the words to Gawain is a prostitute whom he spent Christmas Eve with. It’s hardly an auspicious time to be talking about Christ, but then again, Essel is arguably the most virtuous character in the film due to her guileless practicality.

Such is one example of how the film follows the plot of the poem while adding often challenging context and subtext to its medieval values. Which in the film’s climax comes when we meet Vikander again in the role of a different character: the Lady of a manor married to a jovial Lord played by Joel Edgerton. They live in high Middle Ages luxury with an unexplained older woman who is apparently blind and mute, and they ensnare Gawain into an odd game: Edgerton’s Lord will gift any animal he kills in his hunts during the day, and Gawain will share with his Lord any gift he might receive in the house. When that gift comes in the unexpected form of seduction from the Lord’s wife, Gawain is forced to reluctantly kiss his host on the lips, all while still hiding that he received an allegedly magical green girdle as a present from her.

These events all occur in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, however they occur with a different meaning here. On the page, Gawain is able to resist the Lady’s advances on three separate occasions, as opposed to instantly capitulating on-screen. And while he proudly kisses his Lord on the mouth in the poem, he still hides that the Lady gave him a magical sash which will keep him safe from the Green Knight’s axe. This becomes crucial at the end of the poem since when Gawain encounters the Green Knight again in the Green Chapel, his grassy-hued foe reveals he’s the same Lord of the manor played by Edgerton in The Green Knight!

As it turns out, the Lord was turned by magic into the indestructible Green Knight by Morgan le Fay, King Arthur’s half-sister who also via magic disguised herself as the old blind woman living in that strange manor. Further, this entire charade was never meant for Gawain; it was orchestrated in the hopes of a king’s man beheading the Green Knight, who would then not die. It’d be such a shocking sight, Morgan thought, it would scare Queen Guinevere to death.

In 14th century Arthurian lore, Morgan le Fay was not yet the chief antagonist of the tales, but she was still an ambiguous presence. Gawain’s journey into learning that even for all his virtue he was still fallible since he hid the green sash from the Lord is almost narrative happenstance.

That is how Sir Gawain and the Green Knight ended in the 14th century. But is that actually what’s occurring at the end of the 2021 movie, with the Lord and Lady in league with an unseen Morgan le Fay? Yes… and no.

The Game Being Played By Gawain’s Mother

While the ending of The Green Knight’s source material reveals the titular character is Edgerton’s Lord in disguise, that’s obviously not what Lowery’s film is about. Indeed, we see how the Green Knight is summoned by Gawain’s unnamed mother in the film, risen from the weeds of the earth as if he were the pagan deity we call “the Green Man” made flesh.

There is definitely a pagan witchiness to the woman played by Sarita Choudhury. She openly refuses to go to her kingly brother’s Christmas Day feast and instead uses Wiccan-like magic to summon a champion born from nature. We know she is in league with the Green Knight, but it is not immediately clear to what end. All that’s evident is when she hides beneath a blindfold, she is at the Camelot feast in spirit when the Green Knight intrudes.

In Arthurian lore, Gawain’s mother is named Morgause, and she is one of Arthur’s several estranged half-sisters. In fact, before the sorceress Morgan le Fay was depicted by post-19th century texts as the ultimate villain of Arthurian tales, even birthing Arthur’s would-be usurper Mordred, it was Morgause who gave birth to both Gawain and Mordred in Le Morte d’Arthur, the latter by incest after sleeping with her half-brother Arthur.

When we spoke with writer-director Lowery about The Green Knight, we asked if he intentionally blended the Morgan le Fay of the original Sir Gawain and the Green Knight tale with Gawain’s mother.

Says Lowery, “Very pointedly we did not give any of the characters, other than Gawain, Essel, and Winifred, a name. No one is named. King Arthur is just ‘the King.’ Merlin is just ‘the Wizard.’ So Morgan le Fay in our story is Gawain’s mother. And we wanted to embrace what the original poem did, which was have Morgan le Fay be the character who is behind it all, but I wanted to make her aim, her plot integral to Gawain’s journey.”

He continues, “In the original poem, Gawain sort of just accidentally intercepts this devious plot to scare Guinevere to death, and he gets in the way. But he was not meant to play a role in what Morgan le Fay was conjuring that day, that Christmas morning. So I wanted to honor her role in the story but also make it still revolve around Gawain. And the way I ultimately realized I could do that was to combine the character of Gawain’s mother with Morgan Le Fay and make them one and the same.”

Read more

Movies

Old: Why M. Night Shyamalan Channeled Agatha Christie Mysteries

By Rosie Fletcher

Movies

Why Twilight: Breaking Dawn – Part 2’s Twist Ending Works

By Kayti Burt

The alteration also changes why the Green Knight came to Camelot that day, as well as what the green sash really means for Gawain. In the original text, it really did not matter who attempted to behead the Knight in the Yuletide game, but in The Green Knight, Gawain taking the challenge may or may not be the entire crux of his mother’s plan.

While it is open to interpretation, I think the Green Knight was personally intended for Sean Harris’ enfeebled King Arthur, who is the only man at the Round Table eager to meet the challenge. He’d have done it too, if not for the weakness in his hands (also a change from the original story). So there’s a scenario that could’ve occurred where Arthur beheaded the Green Knight and then was doomed to spend a year getting his affairs in order before meeting the foe again next Christmas.

However, there is the other added wrinkle in the movie that the Green Knight gives Gawain an out. He explicitly says that it’s Gawain’s choice to strike him as hard as he wishes or to leave but a scratch. Arthur cautions his nephew to remember “it’s just a game,” and Guinevere is clearly heartbroken when Gawain lops the Green Knight’s head clean off. The royals knew that was the losing strategy.

I would argue, then, that is why Choudhury’s Morgan gives her son his first green sash. She intends for her son to be king, just as how modern interpretations of Morgan le Fay have her angling for Mordred to usurp Arthur. (It should also be noted The Green Knight implies Mordred exists in this film’s universe since Arthur asks Gawain to take an empty chair next to him, intended for another who’s left.)

Who Is Alicia Vikander’s Lady of the Manor?

The green sash is supposed to be Gawain’s salvation, which brings us back to Vikander and Edgerton’s Lord and Lady. By the time that Gawain reaches their home, he has lost the girdle, and much of his integrity, while on the quest. Ergo, the house’s waiting occupants are there to tempt Gawain’s virtue, as opposed to test it.

As Lowery says, Morgan le Fay has much the same function here as she does in the original story, and that includes her being the mastermind disguised as a frail old woman. Consider that the blind woman Gawain always sees in the presence of Vikander’s Lady wears the exact type of blindfold Gawain’s mother wore while summoning the Green Knight. She is there to ensure her son receives a second green girdle that will have magical properties to keep him safe.

Which brings us to the actual seduction. In the text, Vikander’s Lady is there to test Gawain’s virtue. On the screen, she is determined to shatter it, hence the curious dual casting of Vikander as both Essel, the prostitute who Gawain maybe loves, and the courtly Lady who so easily dissuades him of his concerns about coveting another man’s wife.

A surface level reading might be about the limited ability Gawain has to adhere to the Chivalric Code, in which men strive to be noble and all women are reduced to wilting flowers and possessions for their lordly masters. In this sense, all women look somewhat the same to Gawain. Indeed, such assumptions are repeatedly challenged on screen as he’s bested by multiple women, beginning with the pair of thieves who actually capture him and steal his first green sash, and now again by the woman who gives him another sash by appealing to his lustful desires.

But such a reading misses the larger themes at work, as well as the implicit magic at play in Vikander and Edgerton’s home. Their castle is more than just a refuge, and her Lady is more than just a seductress. In the scene where she climbs atop Gawain, she only breaks his (meek) protestations by asking if he believes in witchcraft and magic. Like any good man of the Middle Ages, he says of course.

Only when she mentions magic and offers a green sash like Gawain’s witchy mother did, does Gawain abandon any pretense of virtue, succumbing to the lady’s beauty and her magic. He is surrendering to a fear of death as much as lust, knowing on a primal level if he gives in to her, the magic she promises will save his life from the Green Knight’s blade.

This entire house was designed by his mother and her coven as a trap to seduce and protect Gawain via his foibles. If you pay attention early on in the film, one of the nameless weird “sisters” who help Morgan summon the Green Knight has the same hairstyle Vikander does when Gawain first arrives at that house. As Gawain’s mother has taken on the countenance of an old blind woman, another witch (and possibly Gawain’s actual sister) has taken on the appearance of the woman Gawain loves but is too foolish to wed. He refuses to take Essel as a wife because of her lowly stature, yet allows himself to be beguiled by her face when it belongs to a highborn “Lady,” despite said Lady being another man’s wife.

Gawain’s mother wants her son to have the sash as it will keep him safe, and allow him to return to Camelot as a hero and true heir to Arthur. Which is why Gawain’s final decision is so significant.

cnx.cmd.push(function() { cnx({ playerId: "106e33c0-3911-473c-b599-b1426db57530", }).render("0270c398a82f44f49c23c16122516796"); });

The End of Brave Sir Gawain

All of which brings us back to the Green Chapel and Gawain’s decision to confess he is wearing a magical green girdle—and to then throw it away. Moments before this, Gawain has a vision of what his life would be if he survived the Green Knight’s axe, either by magic or cowardice. He runs away and returns home, claiming to have survived his quest with honor.

In silent montage, we see what kind of honor playing political games and giving into ambition provides him. He becomes king and marries a woman he doesn’t love. Meanwhile, the woman he does love, Essel, is abandoned after Gawain steals their son from her. In the end, he lives a life of feigned honor, hidden behind the false security and protection the green sash gives him. Unlike his uncle, he does not offer Camelot a golden age: There is only death and ignominy from such a cautious self-serving path. And in 20 years’ time or so, he still will lose his head.

All of that flashes before Gawain’s eyes at the moment of his greatest fear: the Green Knight’s axe falling. Up to this point, he’s attempted to look as majestic as a knight (or king), but throughout the film he has failed time and again to be truly virtuous. He was taken by a band of ruffians in the wood where he begged for his life; he first requested payment from the ghost of a murdered girl instead of simply helping her find peace; and then he received the green sash through a moment of monstrous infidelity and carnal surrender.

As Vikander’s Lady says, red is the color of passion, and green the color of passion the morning after. His green sash represents both life and death, bloom and decay, and it’s stained with the literal seed of his sin. To wear it might allow him to cheat death today, but it instills a lifetime of cowardice. A stain on his honor.

Read more

Movies

A24 Horror Movies Ranked From Worst to Best

By David Crow and 3 others

Movies

Old: M. Night Shyamalan’s Twist Ending Explained

By Rosie Fletcher

Likely his mother suspected second-guessing, which is why she also took the shape of a fox to warn her son that he may face his doom if he meets the Green Knight—we know the fox is really Morgan because in the animal’s final scene it speaks with the voice of Gawain’s mother.

So in the movie’s final moments, Gawain understands all of this, and the ignoble road his nature is leading him on, and he finds the courage his mother feared: He takes off the sash and faces the Green Knight’s axe fair and square.

This is the thematic crux of the original text, too. As Lowery tells us, “He ultimately fails [in the poem], Gawain does not live up to the Chivalric Code to which he’s bound. When he kneels before the knight with the girdle on, he is approaching his state with cowardice in his heart. So I wanted to take that fallibility and present a more binary version of it and have a character who is not yet the knight of legend but who has room to grow into that.”

And yet, Lowery has also changed the meaning of that ending, including Gawain’s fate. In the poem, Gawain does not tell the Green Knight he wears the sash (just as he hid it from the Lord), because he fears death in spite of all his virtue. In the film, Gawain is a man who spends Christmas morning in a brothel and has lived his whole life without real honor. But in the moment where it most counted, he became a true knight by taking the girdle off.

It is a complete reversal of the poem’s ending, turning this into a story about living in peace with yourself, as opposed to an impossible Code thrust on you by society. In many ways, it’s like Vikander’s Lady also saying she changes the stories she reads when she sees room for improvement—although Lowery tells us that line was not intended to be self-referential about how he adapted the poem.

“I knew I would get in trouble for it,” the director laughs. “I don’t know what was going through my head when I wrote that, but Alicia just fell in love with it.” He even almost cut the line in post-production until Vikander convinced him to keep it in.

Intentional or not, the Lady’s admission is what the entire ending of the movie is about. Gawain has found grace and true nobility, improving himself and his story. Unfortunately for Gawain, true chivalric virtue is no shield, and by finding it he’s also found his last act. Thus the Green Knight’s final line. “Now little knight, off with your head.”

If you can live with yourself, you can also die in peace. That’s chivalrous.

The post The Green Knight Ending Explained appeared first on Den of Geek.

from Den of Geek https://ift.tt/3BUNDwx

1 note

·

View note

Text

PENTAGRAM/PENTACLE DEFINED FOR BEGINNER WICCANS

Symbols are constantly recycled in society and religion. Their meanings evolve over time and can differ from belief system to belief system. A pentacle/pentagram is one of those symbols that has picked up a whole lot of baggage over the years. Beginner Wiccans often come to our religion having to ‘reprogram’ their own way of thinking about the pentagram. For years, pop culture, media hysteria and other religions have drilled the idea into our heads that Pagan symbols are bad, and the pentagram is evil.

Unfortunately, in a lot of books aimed at Wicca for beginners, more misinformation about the pentagram is spread. This time, it errs on the side of trying to make the pentagram look good, attaching to it all kinds of romanticized ideas that are just not factual.

What is a pentagram? What is a pentacle? Is there a difference? Let’s have a closer look at the history of this symbol, and the meaning of the pentagram today.

WHAT IS A PENTAGRAM?

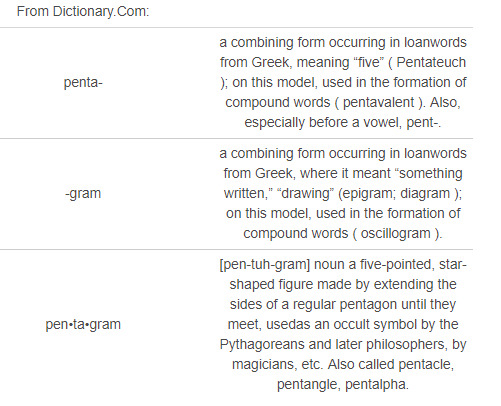

A good place to begin anytime you’re trying to understand a word and its usage is to hit the dictionary and look up the entomology of the word. The word pentagram is rooted in the Greek.

Instead of giving you my own interpretations, I’ll take the meaning directly from the dictionary:

MEANING OF A PENTAGRAM: A BRIEF HISTORY

The earliest use of the pentagram we know of is from ancient Sumeria-- but it wasn't a religious Pagan symbol. It was a word in their language that meant a corner or angle (due to the 5 sharp angles in the figure).

In the 6th century BCE, Pherecydes of Syros used it to illustrate the five recesses of the cosmology. Pentagram figures occasionally turned up in the far East as well, due to the 5 Chinese elements: wood, fire, earth, metal, water.

Pythagoras went on to use the pentagram as the symbol of man. Partly it was because the shape represented a human standing with his arms spread wide (the top point being the head, the to outer points the arms, and the bottom two points the legs). It was also considered to represent the 5 elements that the Greeks believed made up the physical body: Earth (matter), Air (breath), Fire (energy), Water (fluids) and Aether (the psyche or soul). When Pythagoras’ school was driven underground, students used the pentagram as a secret symbol to identify each other.

In ancient Judaism it was a symbol found in mysticism, related to the top portion of the Tree of Life in the Kabbalah, it stood for the 5 books of the Torah (what Christians refer to as the Pentateuch in the Old Testament of the Bible) and the symbol was featured in a seal representing the secret names of God.

Early Christians into the middle ages used the pentagram heavily as a symbol for Christ’s five wounds. The star of Bethlehem that lead the wise men to the baby Jesus was believed to be the pentagram. In Authorial legends, you’ll often see the symbol of the Pentagram inscribed on knight’s shields and other things—these were actually Christian, not Pagan, references. Christians thought of the pentagram as a protective amulet, and it was the primary symbol of Christianity back then, even more common than the cross.

So the pentagram had a long, ancient history of uses as a Pagan symbol and Judeo-Christian symbol. It had no single meaning. It represented perfection in mathematics, the human body, words, and was also used in religious ritual and magic.

BUT WHAT ABOUT WITCHES, WICCANS, AND SATANISTS?

So I’ve mentioned that just about everyone had used the pentagram back then, except I haven’t mentioned Witches, Wiccans and Satanists. What about them?

The fact is, they didn’t really exist yet. The only “witches” at the time were the kind of folklore and rumor. Oh, don’t get me wrong—there were people who did magick, but they would not have identified with the term “witch”.

WHEN THE PENTAGRAM BECAME ASSOCIATED WITH “EVIL”

The 14th and 15th century saw the rise of occult practices that were rooted in Judeo-Christian symbolism and mysticism, and they borrowed liberally from many of the symbols, including the pentagram. They also borrowed from Gnostic and Paganism symbols. It’s no small surprise Ceremonial Magicians were accused by the Christian church of heresy. And heresy, to a medieval Christian, barrels down to Paganism, Satan worship and witchcraft.

Anything liberally used by Ceremonial Magicians became associated with anything considered heretical. If you don’t want to be associated with such things, you don’t use their symbols.

By Victorian times, the witch hunt craze was ending, and people started to forget how pentagrams were once very common, prominent Christian symbols. It’s now associated with paganism, Satan and witchcraft, and seen as an evil symbol.

The love of romanticized myth and history drive a new movement: the Pagan revival, and the pentagram gets turned around again. This is where it gets confusing, because misinformation and false histories begin to fly liberally from the late 19th to mid-20th century.

This is the time the Pagan Revival begins (mostly a re-invention than a re-construction of “Old Ways”). This is when Margaret Murray published her theories on ancient Witch cults being peaceful Pagan religions—though her works have been completely debunked since. This is when Gerald Gardner founded Wicca, and people came crawling out of the woodwork claiming to be ‘hereditary Witches’, or claiming their coven was ancient, or claiming some unbroken line to the Pagan religions of antiquity. This is also when a few ‘reverse Christian’ groups popped up, with practices specifically designed to mock and rebel against Christianity (those these groups were pretty rare and the NeoPagan community did their best to distance themselves from such groups).

One thing most of these groups have in common, though, is that they adopt the pentagram.

Hollywood – new on the scene in the mid-20th century – adopts the pentagram as well. Hollywood is not interested in accuracy; it’s interested in the shock value of things. They adopt it as a symbol for evil magic and reverse-Christian style devil worship and stick it into just about every horror movie conceivable. This fuels the antics of a lot of bored, rebellious people, particularly teens, who like to spray paint it on park walls and carve it into trees for the shock value.

By the late 20th century, the pentagram is being used and abused all over the place, but it is Hollywood who manages to make an indelible imprint on the social consciousness—and this is further driven by the media with sensationalized reporting during the 1970’s “Satanic Ritual Abuse” hysteria (which has also been debunked).

It’s only the tail end of the 20th century and the beginning of the 21st century in which the pentagram is finally gaining some understanding. Though mainstream society hasn’t completely lost the ‘kneejerk reaction’ to it, the growth of the Pagan Revival and the availability of information via the Internet have helped to quell some of the shock value and fears over it.

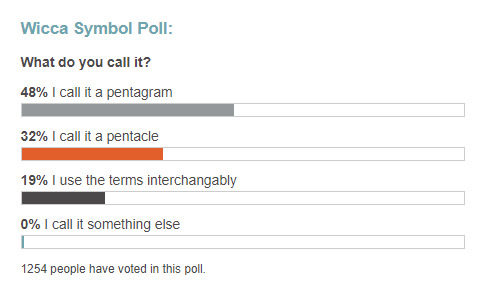

WICCAN SYMBOLS: PENTAGRAM VS. PENTACLE

More misconceptions abound, considering the Pagan community more commonly refers to the symbol as a ‘pentacle’ rather than a ‘pentagram’. Many books and websites have tried (and failed) to make the distinction clear. Some assertions I’ve read in passing are:

The pentagram is evil with one point down

the pentacle is good with one point up

The pentagram is just the star

the pentacle is the star with a circle around it

The pentagram is 2-D; the pentacle is 3-D

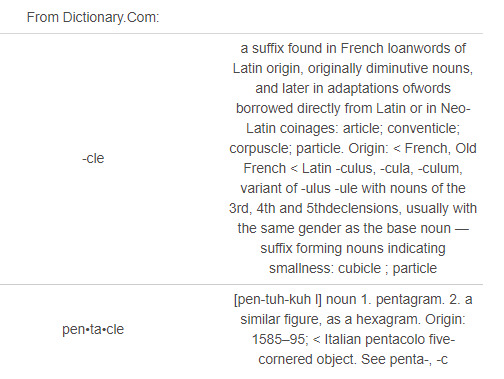

Actually, all of these answers would be technically incorrect. If you look at the definitions provided above, pentagram and pentacle are synonymous, and have nothing to do with which way the points face, or whether or not they have a circle around them.

A look at the dictionary's answer to pentacle and you see that the only real difference is one is derived from the Greek, the other from the Latin:

DICTIONARY MEANING OF A PENTACLE:

THE PENTACLE: NOT JUST A FIGURE, BUT A TOOL

A tool arose out of ceremonial magic. This tool was a flat, round disc or paper that was inscribed with protective symbols (a pentagram could be inscribed on it, but there were other symbols they used as well). It is used as an amulet of warding and power because a large part of Ceremonial Magic is invoking and commanding various entities from Judeo-Christian beliefs.

It was called the pentacle or sometimes pantacle. On the Tarot (a Christian-origin divination system), the symbol is used for the suit of coins, and it represents the Element of Earth.

Wicca and other NeoPagan religions borrowed this tool from Ceremonial Magic. They kept the name, but re-defined its purpose since Wiccans don’t believe in Judeo-Christian entities and is not concerned with calling or commanding spirits.

The pentacle (the disc) was adopted as an altar tool, and is used to symbolize the Element of Earth on the altar. It’s also used as a tool for placing sacred items upon it when cleansing, consecrating or charging them.

The Wiccan symbol of choice for this round disc was the pentagram/pentacle. To further confuse things, this tool does not have to be inscribed with a pentagram/pentacle.

TYPICAL MEANING OF A PENTAGRAM/PENTACLE IN WICCA

As far as Wiccan symbols go, the pentagram isn't a representation of good vs. evil. It’s a symbol of our faith, a symbol of the 5 Elements (one for each point), and the circle (the universe) contains and connects them all. No matter which way it’s facing, circle or no circle, there’s nothing ‘bad’ about it.

Another misconception about the pentagram in Wicca is which way it points. Again, you will find common misinformation that says the pentagram is “evil” if point down and “good” if point up. The point down is most commonly associated with Satanism, because the largest branch of Satanism (Church of Satan, est. 1966) adopted the inverted pentagram with a goat head inside of it as their symbol.

It’s traditionally used both point up and point down. Point up pentagrams are more common; but point down pentagrams are not considered evil at all.

The point-up pentagram represents the spirit ascending above matter. The top point represents the Element of Spirit, the other four points represent the four Spiritual Elements.

When a pentagram is point-down, it represents spirit descending into matter. This is most traditionally used in lineage covens during second degree initiations, because it’s at this point of one’s spiritual path that one turns “inward”. You face and challenge your ‘dark side’ – your base emotions, fears, ignorance, prejudices, etc., you deal with them and develop mastery over yourself.

#pagan#wicca#wiccan#witchcraft#witches of Tumblr#witch#magick#pentagram#pentacle#spell#easy spell#the craft#paganism#amethyst#moon#full moon#eclipse#nature#neo wiccan#neo pagan#gif#fashion#art#food#landscape#vintage#design#quote

2K notes

·

View notes