#this is just a gender thing not an actual change in the distro

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Fedora distro update: Oops! No longer a binary distro! 🟨⬜🟪⬛ Binary packages will still be available and we're committed to support all your favorite architectures: he/she/they/any

#nonbinary#this is just a gender thing not an actual change in the distro#linux#linuxposting#fedora linux

119 notes

·

View notes

Text

So, I have a bunch of plans for 2022. One is to archive both of my old podcasts (Nobody Cares About Your Stupid Zine Podcast and PDX Witch Guild) and hopefully start a new witch podcast with a good chunk of the old PDX witch guild, possibly with a new name. 4 of us actually hung out on the solstice and had a blast. Our lives have all changed a lot from romantic partnerships, living arrangements, spiritual endeavors, best friend disappointments, job situations, gender identities, experiences with the legal system, and on and on. If you stay in one place, you aren't living life. But we all support each other and had a great time.

I'm also renaming the PBW Witch Shop to encompass all of the catalog of things under one name. It used to be Portland Button Works and then I added a zine distro so it was Portland Button Works and Zine Distro or sometimes PBW Zine Distro so I added PBW Witch Shop to keep it all in theme. I worry that it is all just confusing. Now I have a new name I'll be revealing next year. I'll still keep Portland Button Works for the custom button biz, but all of the catalog items will be under a new name.

Also, I, started making custom buttons in 2000 with a business I ran with my ex-husband, then started Small World Buttons in, like 2007. In 2012 I collaborated with a friend (who quickly left) to start Portland Button Works. That means 2022 in May Portland Button Works will be 10 years old! I'll be offering some birthday sales but on May 1st We'll be hosting a porch sale! I'll bring out the zines and bookshelves and button bins and other curiousities and will invite some friends to sell their wares. We'll have jewelry, plants, seeds, and maybe pottery, maybe invite our friend with a box truck shop that sells records. Who know! But, if you are in Portland on May Day (May 1, 2022) stop by and check it out. I'll post more about it later.

I'm also going to be in Chicago in April for the Midwest Perzine Fest and hope to have another zine ready for that. I want to practice with my band again and play some shoes. I was fucking around on drums a few weeks ago since they are in our basement so I want to make time for that too.

I turn 45 in June and hope to do something fun for that, even if it's just sitting around with friends and listening only to records that are played at 45 rpm.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

zine ideas

What is a zine?

A zine (pronounced zeen) is an independently or self-published booklet, often created by physically cutting and gluing text and images together onto a master flat for photocopying, but it is also common to produce the master by typing and formatting pages on a computer. The publication is usually folded and stapled.

Historically, zines have been around since 1776 when Thomas Paine self-published Common Sense and used it as an instrument in promoting the ideas that contributed to the U.S. War for Independence. Just a perfect example to demonstrate the free spirit of zine culture.

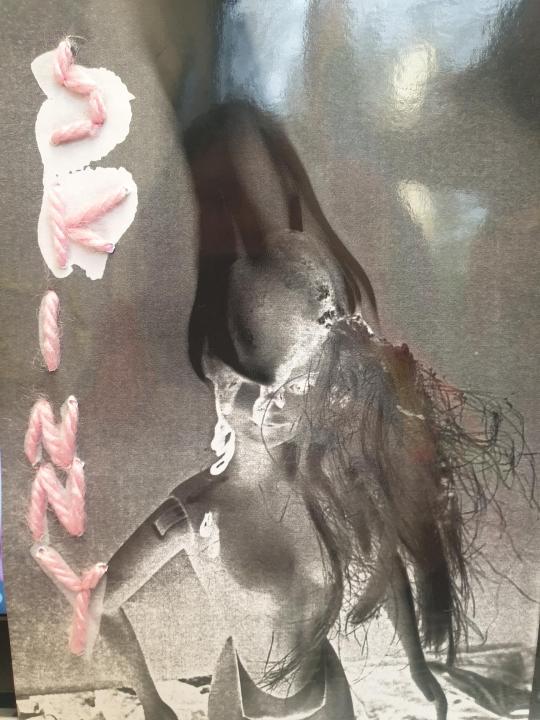

key words: Body image, beauty standards, perfect, society.

I found this zine on a teen mental health website, im going to use this as my main influence for my zine.

http://teentalk.ca/resources/zines/body-image/#prettyPhoto[gal_2]/14/

other zines that helped me understand what a zine is :

https://museumcrush.org/the-fanzines-that-celebrate-diy-politics-art-and-rocknroll/

Pintrest board

https://pin.it/4lczsZL

Riot grrrl

Riot grrrl is an underground feminist punk movement that began during the early 1990s within the United States in Olympia, Washington and the greater Pacific Northwest. It also expanded to at least 26 other countries. Riot grrrl is a subcultural movement that combines feminism, punk music and politics

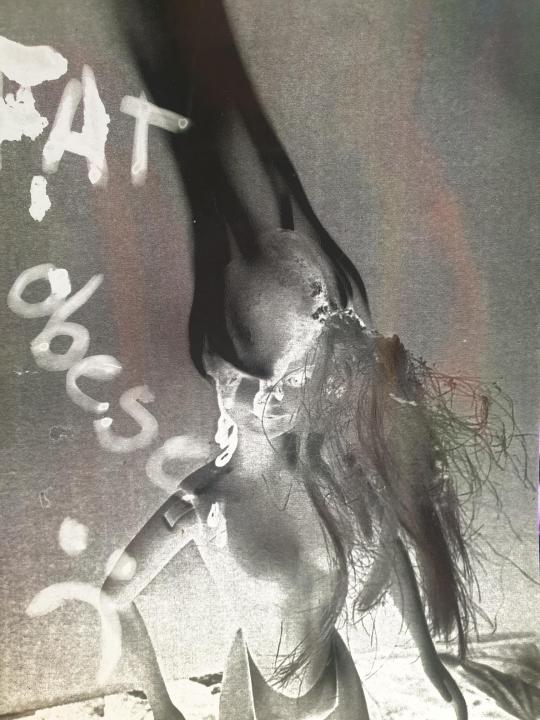

i was a fan of the riot grrrl manifesto and i want to incorporate that scrap book punky style in to my zine about body image, i also want to include the black and white with pops of colour to make certain things stand out more than others

Barbra Kruger

Barbara Kruger is an American conceptual artist and collagist associated with The Pictures Generation. Most of her work consists of black-and-white photographs, overlaid with declarative captions, stated in white-on-red Futura Bold Oblique or Helvetica Ultra Condensed text

Her use of words and pictures convey a deeper meaning. Her artwork shows the viewer how fast people label others in society. The work shows how another person’s view can impact society as a whole by letting the hierarchy in society manifest our culture. Barbara went beyond this to get a reaction from society by raising this social awareness in her art. Through her works she expresses gender, sexuality and other stereotypical issues that are developed within a mainstream culture.

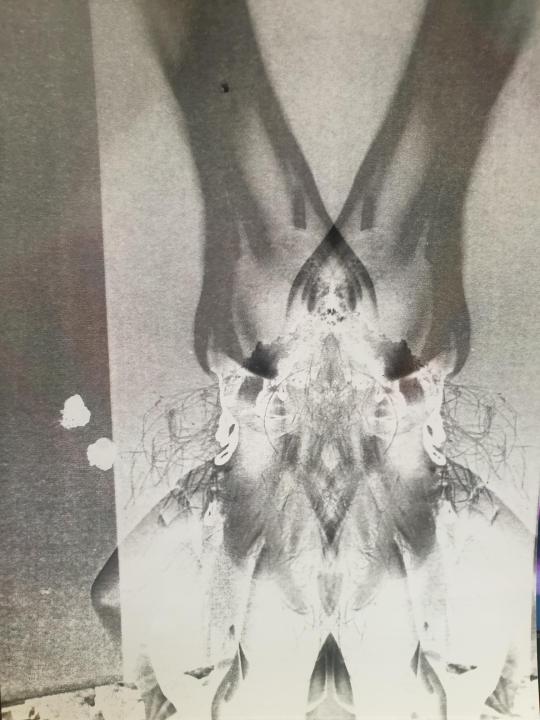

Dark room

to make our zines more unique and develop our skills, we did a dark room work shop and developed some images that we could include in our zine

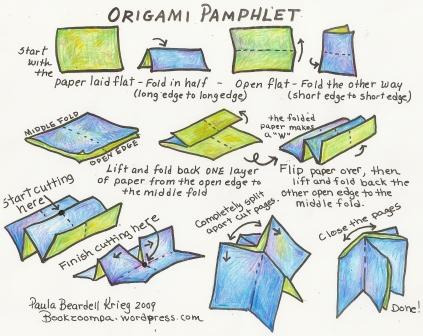

rigami book folding

this is the one i chose to do, my final one when i create the zine will be made with an a1 piece of pink sugar paper which when folded will be pages of a4

Format

After working on the zine for a good month or so now its time to start working on compiling all of the techniques learnt together and using my information on my topic to create the actual zine, I looked at zines and saw online is popular especially during the covid era, so I plan to digitise my zine as well as make print out copies, I wont be sending it away to get printed fancy or anything I will do my best to make it look as polished myself as its more personal I feel.

https://guides.douglascollege.ca/zines/print

I found a few ways with tutorials on how to format your zine, now I have to think about size, most zines are A5 but I feel like I can't fit enough stuff in to an A5 zine so im thinking of doing it A4.

My zine completed

First copy

First paper copy.

I printed off my first draft and sent it to my teachers and got feedback from it, I used the feedback and changed it to make it better. I changed the whole thing so it was digital, I used a website called flipsnack.com, I chose this website because it was free and it gave the pages a glossy look and the animation was like a page flipping which gave it a realistic feel.

Finished zine

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

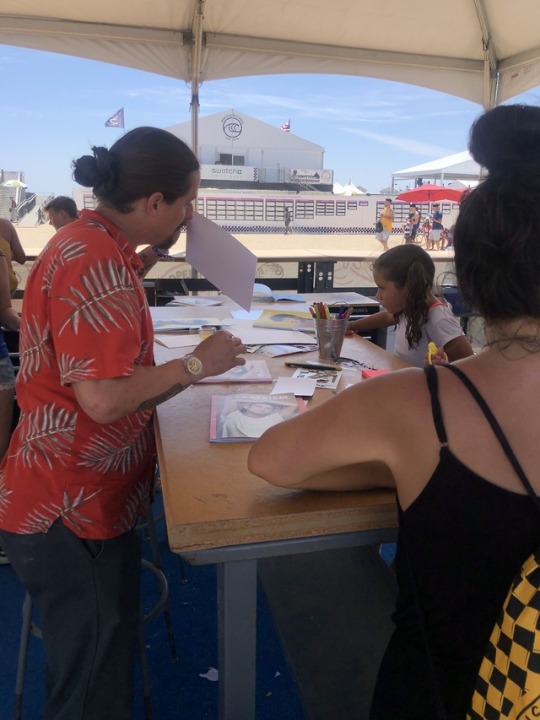

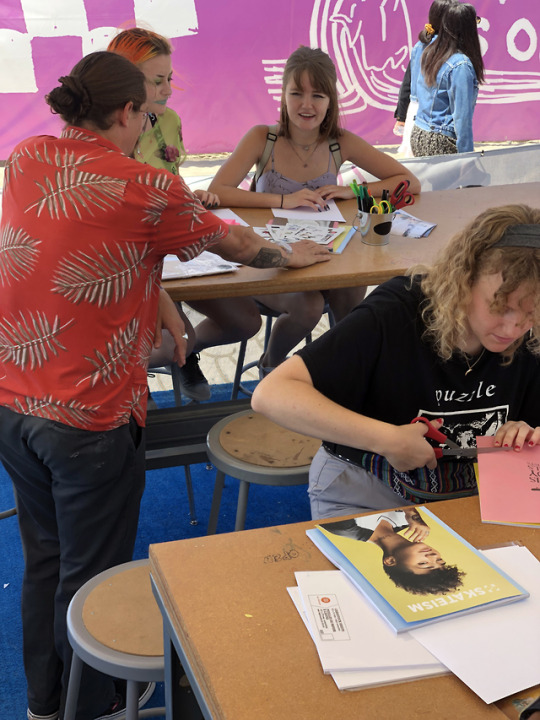

WORKSHOP SHOUT OUT | SKATEISM | VANS US OPEN

It’s the last weekend of the Vans US Open of Surfing, but we’re not ready to go just yet!

We’ve still got some of our favorite workshops over the week to share –like the fun folks over at SKATEISM who hosted a zine making workshop at Van Doren Village. We caught up with Tobias from SKATEISM to find out what folks created, more about the zine making process, and what special gift they're giving out on this final weekend.

Introduce yourselves and tell us a little bit about Skateism. My name is Tobias Coughlin-Bogue, and I’m the online editor for SKATEISM. The magazine was founded by Christos “Moch” Simos and Oisin “Osh” Tammas in Athens. It began as just a little local Athens skate blog in 2012, but when Osh signed on they started doing more English-language posts and international coverage. Moch is one of the only out skaters in Greece, and at some point he and Osh realized that the stories they were most interested in telling centered around that… as well as some other areas of skateboarding they felt had been neglected like skate charity, global scenes, and women’s skateboarding. They also realized they wanted to make a magazine, as a place for underrepresented populations in skateboarding to see themselves in a proper print publication. Two years and four issues later, that’s exactly what they’ve done and we’re very proud to present Issue #4 as the Pride issue, focusing on the experiences of LGBTQ+ skaters.

Take us through your workshop and what were you doing with attendees at the Vans US Open? Essentially we facilitated everything to make a zine except shooting photos or binding the final copies. We had prints of images on hand for people to cut and glue onto cardstock, creating what’s called a “master” page. Masters are what zinemakers make photocopies of that they then bind together into their final zine. We started the workshop by talking a little bit about what zines are and why we think they’re so cool. We covered the zinemaking process, and then dived right into it.

What about zinemaking do you think is super fun and accessible? Zinemaking was a fundamental part of the pre-internet skate culture. While it isn’t exactly a necessity anymore, when it comes to communicating our own unique visions of skateboarding it’s still super fun to do. It forces you to take all the things that catch your eye at an event like the US Open, that might be a quick Insta story or something, and put them all down on a page together in a thoughtful way. Plus we like writing about skating, and zines incorporate a lot more text than some of the forms of storytelling we do on social media these days.

As far as being accessible, well zines were kind of the social media in skateboarding (and punk and queer scenes too) before social media existed. They were cheap to make and there was a broad network of people sharing and exchanging them around the country, all interested in the same kind of subcultural topics. If you had an idea you wanted to share, you could just paste the images and words that capture it best to some backing paper and get to photocopying. Then mail it out to a distro or drop it off at the skate shop and — boom — you’re a publisher.

Obviously a lot more work goes into what we do with something like SKATEISM, which takes hours and hours of reporting and editing and designing to make, but I at least got into the world of skate media via zines, and I have a huge soft spot for them. For what I do, and what a lot of people getting into media these days do, learning to publish fast and loose is actually really helpful, because that’s the pace digital media operates at.

What type of materials did you have on-hand for folks to work with? We shot a few photos of the first weekend of the event on Kodak Fun Savers (a very accessible and enjoyable way to source art for your zine!), and made photocopies of the best exposures. Plus, we had copies of some pages from past issues of SKATEISM… And of course all the scissors, glue, card stock, staplers, and other stuff folks needed to put together their own master pages. We encouraged attendees to supplement the images we’ve provided with writing and drawing that documents their own experience at the event!

Are there any rules to zinemaking? Have a good time doing it and don’t be hateful. That’s about it.

Any tips you’ve learned over the years for readers who may want to try creating a zine on their own? Just start doing it. To borrow a concept from Ira Glass, you know what you like to see on the page, so keep trying until the stuff you make starts to look like that. Don’t stress out too much if it doesn’t work out at first. Technically speaking, it’s really important to think in terms of spreads (two individual pages facing each other is one spread), and understand that a magazine is essentially a bunch of sheets of paper stacked up, stapled, and folded in half. Making sure that the individual pages in the spreads line up correctly can be tricky, so it might help to take a bunch of blank sheets of paper, bind them, write page numbers on them, then remove the staples and use them as a template for what to paste on each master page as you’re working.

What other zine techniques can people incorporate besides cutting and pasting? Doing it by hand is obviously the classic method, and will get you the most zine scene cred. But I am not ashamed to admit that, after two issues of cutting and pasting my first zine, I started scanning my photos and putting it all in InDesign. There is no shame in using layout software, and it will give you a whole new appreciation for how much thought and effort goes into every single print publication you ever read. It’s not just what they’re writing and which photos they’re publishing, but where on the page that stuff is, where it is in relation to the other stuff, what color and font things are, what angles they’re tilted at, what the background is, and so on... It’s definitely a different look and feel than handmade, but now that design software is so accessible, we think it’s every bit as DIY.

What did participants create and walk away with after the workshop? Well, besides hands on experience making zine master pages, we’re going to take our favorite masters and make a limited run of a compilation zine to give out on the final weekend of the event.

So we’d like anyone who enjoyed the workshop to come back and grab a copy of that! And failing that, just a better understand of the zinemaking, DIY ethos that skateboarding was built on. Skateboarders have always made their own spots, their own rules, and their own fun. That definitely applies to their media too.

Who are some of your favorite zine makers? In the areas we’re focused on, you can’t not mention Xem Skaters by the Swedish nonbinary skater Marie Dabbadie. They’ve been making a rad, unapologetically genderqueer zine for years, and have done loads to change the conversation around gender in skateboarding. Of course, The Skate Witches are killing it too. In terms of general zines that I like, I grew up volunteering at the Zine Archive and Publishing Project in Seattle, which had copies of really rare ‘90s skate zines like Pool Dust, so I tripped out on those a lot growing up. Not ‘cause I’ve ever actually skated a real pool, just because they had this really scrappy, no bullshit aesthetic and made skateboarding look so cool.

Recently, I was on a team for Thrasher’s “Zine Thing” Challenge in Seattle, which gave people two weeks to shoot a zine with Fun Savers; two weeks to do writing, editing, and layout; and then gave awards in different categories. Looking through the compilation book of all the entries still blows my mind. It’s a great reminder that skateboarding is full of cool, creative people, and everyone has a wildly different experience of it. I still can’t pick a favorite, although Leo Bañuelos' ’Skaters in Drag’ article is pretty legendary.

Three words that describe what Skateism is all about? The underground and overlooked. Sorry that's four!

Who or what were you most excited to check out at the Vans US Open? Personally, I’m excited to finally skate Cherry Park (nearby). But that’s just because my joints are falling apart and I can only skate low ledges. At the Open, I was excited to see all the pros skate the course, especially the women. Women’s skateboarding has been growing at an insane pace in the last few years, and the level of talent is out of control. When I started skating, I never thought I would see little girls back-smithing huge hubbas and female pros filming back-tail-kickflip-outs for their video parts, but here we are. The rate of progression is so exciting to me, and I feel like people will definitely be throwing down for the event.

FOLLOW SKATEISM | WEBSITE | INSTAGRAM

#Art#Vans#VANSUSOPEN#SKATEISM#ZINE#ZINE MAKING#WORKSHOP#HUNTINGTON BEACH#SKATE MAG#PRINTED MATTER#COLLAGE

14 notes

·

View notes

Link

In the wake of the murder of George Floyd and the ensuing protest, the racial biases that still plague countless industries have come to light, and skateboarding is no exception. Last week, Na-Kel Smith took to Instagram with fellow skaters Kevin White and Mikey Alfred to open up about his personal experiences of racism within the industry. Now, brands are stepping up with Palace pledging $1 million to Black Lives Matter and the Stephen Lawrence Charitable Trust, and Supreme pledging $500,000 between a number of charities.

Given skateboarding’s countercultural roots, brotherly spirit, and general hatred towards cops, it may come as a surprise that racism is still a serious issue. But, the sport has yet to shake the systemic biases that stem from its origins in ’60s surfer culture in California, when it was an activity practiced almost exclusively by white male Californians. It was only in the early ’90s, when vert skating declined due to lack of investment in parks and competitions, that people took to the streets and a new wave of skating surfaced. Street skating was accessible to anyone, and with it came an upward curve in the number of black participants, diluting the skater archetype of the white male antihero.

Although the participant demographic has changed significantly, the professional industry itself remains largely white. That’s not to say there hasn’t been positive change. The last 10 years have seen a significant increase in the number of brands and media owned by and created for skaters of all backgrounds, genders, and race, and even the launch of a Pushing Boarders, an annual conference focused on addressing the social and structural issues in skateboarding. In spite of this democratization, those pulling the (purse) strings remain mostly white and the comradely nature of skating serves, too often, as a veneer for harmful biases and behavior beneath.

Following the protests and spurred on by pro skater Na-Kel Smith’s honest recount, lifetime skater Patrick Kigongo was inspired to put together the Black List, a crowd-sourced database of black-owned skate organizations, brands, and media. Kigongo grew up in suburban New York, moving to Washington D.C. to study international affairs, and went on to work in the NGO sector. All the while, he maintained an active part in the independent music and skate scenes, playing in bands, shooting videos, and working as a writer for a number of online publications, including the early arts and fashion platform Brightest Young Things. He’s now based in LA, where he works as a digital product manager and continues to write on race, foreign policy, pop culture, and skateboarding. We caught up with Kigongo to talk about the list and the state of racism in the industry today.

Why did you create the Black List?

After that first weekend of protests here in LA, I really started to ask myself, “What more can I do?” Then Na-Kel Smith jumped on Instagram Live giving what was a foundational speech with Mikey from Illegal Civ and Kevin White. What that conversation really did was touch upon something that every black skater — whether you are just a fan like me or a sponsored skater — has experienced. We’ve all experienced microaggressions. We’ve all experienced being targeted by the police. He is coming to this understanding as a young man, that a lot of this is not okay. Being in a van with somebody who ironically or un-ironically listens to Screwdriver, riding for companies that may or may not sponsor people who have white nationalist ties. He opened the door for a pretty serious conversation that has been on the sidelines in skating but has never been thrust into the spotlight. And that really got me thinking.

The skateboarding industry is very small. There’s really only a handful of factories that make decks or wheels, and there are only a few foundries that make trucks. None of those major manufacturing plants are black-owned. But there are a handful of black-owned companies. All these folks on social media were sharing black-owned bookstores, restaurants, and clothing companies, so I figured, why not do it for skating and see how many black-owned companies I could find via crowd-sourcing? And, more importantly, reflect this back out to the world to show these companies that not only are they not producing their goods in a vacuum, but also that this could actually be a potential foundation for consolidating some sort of political power.

How has the response been?

Overwhelming. It’s been very positive, people have been overwhelmingly kind. I even got to speak with a couple of legends who’ve reached out to say thank you. And more importantly, it’s been very humbling. It really shows how far skating has come.

Talking about Na-Kel’s speech, what do you think prevented him and other skaters that may have had similar experiences raising them earlier?

I think it’s two things. Number one, not having the vocabulary to describe what’s happening to you, and number two, the fear of consequences and repercussions within the industry. A lot of young skaters may only have a high school diploma and they’ve never held down any other type of job, so this is really the only thing they’ve got going for them. There is a fear that you will be blackballed, or that folks will look at you and say, “Oh, come on, man. He was just kidding. I’ve got lots of black friends. I thought we were bros.” There’s that real fear, that people won’t take you seriously.

Then there are black skaters who feel as though, “I’m just trying to do me, and work my way through this.” They just don’t know how many other black folks are working in the industry. They don’t know that they actually have power, and a voice, and also a huge audience. But now you’re starting to see the gears turning in a lot of these young people’s heads.

You’ve been skating for many years — how have you seen the skater demographic change?

I started skating the summer of 1994/95. This was a period where you had this twin explosion in skating and streetwear culture. You had this sudden wave of young black skaters in the videos and turning pro. For young people like me who grew up skating in crews where I was the only black kid, it was amazing watching videos like World [Industries], Blind, and 101’s 20 shot sequences, or any of the first Girl and Chocolate videos, and seeing a lot of black and brown faces. That was incredibly empowering.

But there were still only a couple of black-owned companies. And even if they were black-owned, the distributors who are getting those boards and clothes into shops all over the world were still white, and the shops were still mostly white-owned. It wasn’t until the early aughts where people stopped saying skateboarding was a white boy thing. You can really thank, first of all, Tony Hawk, pro-skater, for putting guys like Kareem Campbell on it, and also people with crossover appeal, like Stevie Williams. If you fast forward to 2011 with the rise of Odd Future, all of a sudden you saw a whole new generation of young, black kids, who were completely unbound by hip-hop or traditional skateboard culture.

Now, we’re really seeing that skating has smashed through a lot of those racial barriers, at least in terms of sponsorship and in terms of visibility. Not only are there black skaters all over the country, but we’re also all over the world. In Kampala, Uganda, a bunch of kids built a DIY park. When I was a kid when we would go to visit relatives, I couldn’t bring my skateboard. Where was I going to go? The streets were in awful condition, the war had only ended in 1986. It’s still a very poor country, but our kids, because of smartphones and the internet, have been exposed to skating. And this is not just in Uganda, it’s in Ethiopia, it’s in Eritrea, it’s in Ghana, it’s in South Africa, Morocco, Algeria. It’s all over the world. That’s a very, very humbling thing, to see how far skating has come.

What do you think are the main barriers preventing more people of color working in the skate industry?

Firstly, there’s no formal network of transition out of being a sponsored skater, so we don’t have a system for people to ease out of being a pro skater, into being a designer, becoming a sales rep, becoming a distributor. The best you can hope for is maybe getting a job in the warehouse.

Secondly, I think for some people it just comes down to racism. I don’t think that it’s nearly as frequent [in skating] as in other walks of American life, but there are racists everywhere, so I’m going to assume that there are some people in distro companies and work for certain board or shoe companies who are racist and say, “They don’t really fit our image.”

Thirdly, I think it’s difficult to create a sense of real, actionable solidarity within skating. In the 1990s, there was some discussion about creating some sort of a skaters union, off the model of the NBA player’s union, something to get people health insurance, to negotiate fair wages, and maybe even normalize the funding for contests. And it didn’t go over so well. There was an incredible amount of opposition, because again, skating has deep roots in libertarian, right-wing California. And it’s very, very difficult to shake that.

And if it stays that way, the white-dominated industry will see no change.

Mmm-hmm. I’m 100 percent sure it is very similar in streetwear. One of the real difficulties in effecting any sort of change in skateboarding is that there’s no oversight and there’s no accountability within the industry. They’re so used to being able to operate in a way in which there’s not much public scrutiny. For this debate all of a sudden to not only be public but be keyed into what’s happening on the streets right now is a mindfuck. Especially compared to where skating was in the early to mid-’90s, when it was thoroughly a real subculture. But skateboarding is about to go into the Olympics. These guys are no longer going to be able to operate in a vacuum somewhere.

The conversation around skateboarding becoming more mainstream often focuses on the negatives, but the positives are that it is becoming more inclusive and diverse.

Right. All you have to do is go to any skate park in LA. What a radical shift to see lots of brown and black kids, lots of women, even non-binary people. Skating has shed a lot of its mean guy culture, and it will always retain a certain sense of camaraderie. Now, you roll up at a skate spot and it’s like, “Hey, what’s up? Good morning. Where you from, man?” You’re just saying, “Hey, I’m a human being. That’s a human being.” It’s beautiful. What’s really powerful is that in terms of getting into skating, anybody can do it. That’s why a lot of the non-profits like Skateistan or SkatePal in Palestine are becoming more successful, because there are no rules. Skating is really positive for kids because it normalizes failure. How many people who are pushing 40 are regularly trying to go out there and fail? It really humbles you.

I think it’s worth accepting what’s happening right now in terms of discussion about skating and race, and also skating and gender, as part of growing pains. We are being dragged kicking and screaming into the 21st century. And that’s a really, really good thing. You don’t want skating to become viewed as this macho artifact, because then it just becomes embarrassing.

What would you like the knock-on effects from the conversations happening now to be, and more specifically, The Black List?

In the immediate short-term, I want some of these brothers and sisters to get paid. Start supporting these companies. Buy a shirt, buy a board, buy some hardware, buy something. If you’re a store owner, get them into your shop. The list continues to grow, which is a very, very beautiful thing.

In terms of what I hope happens next, I really hope that we can have a skate culture where people will not immediately shirk away from having small P political discussions, and that skaters in the skate industry will embrace one of the most important tenants of punk rock and hardcore, which is that the personal is political. How and where you spend your dollars is an inherently political act, and one of the most empowering and important decisions that you make every single day. And so that, instead of people saying “Oh, I’m not really political.” That they will understand off the rip that they as a consumer, they as a skater, have a certain amount of power.

I also want there to be more shine for skaters of color. Black History Month this year came and went, and although there’s actually a rack of skate podcasts now, where was the Black History episode? Where were the episodes with Lavar McBride or Kareem Campbell? I want that celebration. I want that feeling like this is something that’s super important. And I’m not just talking about an Instagram post. You want the skate media to actually be able to grapple with these kinds of questions.

What else do you think will facilitate these changes?

I think more things like Pushing Boarders. We need more spaces for these conversations to happen in a formalized space within the industry. That’s important. Going forward, you want to make it so that skating can enjoy the same bloom that basketball continues to have as it grows bigger around the world. Something where everybody can get into it, everybody loves it, and everybody is proud of it. Being an NBA fan, you compare players now to the late ’90s, early aughts, where you still have fights, you still had the commissioner beefing with players about, like, “I don’t want you guys to dress like thugs.” To see now, most ballers are serious, they’re investors, they’re part of the community, they’re speaking out on issues such as Black Lives Matter. You’re really proud.

Because the bad boy stuff was fun, but those stories always ended up the same with, “I spent all my money,” or “I burned so many bridges that I have no friends left in the game.” And now, you watch your team, you watch your favorite players, you’re really proud of them. I want skaters to be really, really proud of its subculture. I still want it to be rebellious — skating will always be inherently rebellious because street skating is all about challenging norms between your individual self and private property/public property. But I really want it to be something that’s inclusive, that people can look at and be like, “Why can’t you all be like them skateboarders, man?,” and that doesn’t have a toxic culture. I don’t use that term lightly, but in some ways, back in the day, it was toxic. You were constantly being policed by other people and it was cliquish and judgmental. It’s a lot more open now and I want it to continue to build on that openness, and remind people that this is a subculture, yes, but it is something that is open, and it is inclusive, and everybody has a home here. Except for racists, and hateful people in general.

#the black list#Patrick Kigongo#skateboarding#na-kel smith#kareem campbell#Black-Owned Skate Businesses#minority businesses#sneaker blog#streetwear blog

1 note

·

View note

Text

Setting Fire to Social Justice

Call-out culture refers to the tendency among progressives, radicals, activists, and community organizers to publicly name instances or patterns of oppressive behaviour and language use by others. People can be called out for statements and actions that are sexist, racist, ableist, and the list goes on. Because call-outs tend to be public, they can enable a particularly armchair and academic brand of activism: one in which the act of calling out is seen as an end in itself.

What makes call-out culture so toxic is not necessarily its frequency so much as the nature and performance of the call-out itself. Especially in online venues like Twitter and Facebook, calling someone out isn’t just a private interaction between two individuals: it’s a public performance where people can demonstrate their wit or how pure their politics are. Indeed, sometimes it can feel like the performance itself is more significant than the content of the call- out. This is why “calling in” has been proposed as an alternative to calling out: calling in means speaking privately with an individual who has done some wrong, in order to address the behaviour without making a spectacle of the address itself.

In the context of call-out culture, it is easy to forget that the individual we are calling out is a human being, and that different human beings in different social locations will be receptive to different strategies for learning and growing. For instance, most call-outs I have witnessed immediately render anyone who has committed a perceived wrong as an outsider to the community. One action becomes a reason to pass judgment on someone’s entire being, as if there is no difference between a community member or friend and a random stranger walking down the street (who is of course also someone’s friend). Call-out culture can end up mirroring what the prison industrial complex teaches us about crime and punishment: to banish and dispose of individuals rather than to engage with them as people with complicated stories and histories.

It isn’t an exaggeration to say that there is a mild totalitarian undercurrent not just in call-out culture but also in how progressive communities police and define the bounds of who’s in and who’s out. More often than not, this boundary is constructed through the use of appropriate language and terminology – a language and terminology that are forever shifting and almost impossible to keep up with. In such a context, it is impossible not to fail at least some of the time. And what happens when someone has mastered proficiency in languages of accountability and then learned to justify all of their actions by falling back on that language? How do we hold people to account who are experts at using anti-oppressive language to justify oppressive behaviour? We don’t have a word to describe this kind of perverse exercise of power, despite the fact that it occurs on an almost daily basis in progressive circles. Perhaps we could call it Anti-Oppressiveness.

Humour often plays a role in call-out culture and by drawing attention to this I am not saying that wit has no place in undermining oppression; humour can be one of the most useful tools available to oppressed people. But when people are reduced to their identities of privilege (as white, cisgender, male, etc.) and mocked as such, it means we’re treating each other as if our individual social locations stand in for the total systems those parts of our identities represent. Individuals become synonymous with systems of oppression, and this can turn systemic analysis into moral judgment. Too often, when it comes to being called out, narrow definitions of a person’s identity count for everything.

No matter the wrong we are naming, there are ways to call people out that do not reduce individuals to agents of social advantage. There are ways of calling people out that are compassionate and creative, and that recognize the whole individual instead of viewing them simply as representations of the systems from which they benefit. Paying attention to these other contexts will mean refusing to unleash all of our very real trauma onto the psyches of those we imagine to only represent the systems that oppress us. Given the nature of online social networks, call-outs are not going away any time soon. But reminding ourselves of what a call-out is meant to accomplish will go a long way toward creating the kinds of substantial, material changes in people’s behaviour – and in community dynamics – that we envision and need.

How do you begin to say, “I think we’ve been going about this all wrong?” Howdo you get out of a dead-end without going in reverse? It seems like in the last fifteen years, rape has gone from being an issue that was only talked about by feminists and downplayed in other radical communities, to one of the most commonly addressed forms of oppression. Part of this change might be owed to the hard work of feminist and queer activists, another part to the spread of anarchism, with its heavy emphasis on both class and gender politics, and another part to the antiglobalization movement, which brought together many previously separated single issues.

Despite all the changes in fifteen years, its just as common to hear the sentiment that rape is still tacitly permitted in radical communities or that the issues of gender and patriarchy are minimized, even though in most activist or anarchist conferences and distros I know about, rape culture and patriarchy have been among the most talked about topics, and it wasn’t just talk. In the communities I have been a part of there have been cases of accused rapists or abusers being kicked out and survivors being supported, along with plenty of feminist activities, events, and actions.

All the same, every year I meet more people who have stories of communities torn apart by accusations of rape or abuse, both by the shock and trauma of the original harm, and then by the way people have responded and positioned themselves. One option is to blame a passive majority that toe the line, giving lip service to the new politically correct doctrine, without living up to their ideals. In some cases I think that is exactly what happened. But even when there is full community support, it still often goes wrong.

After years of thinking about this problem, learning about other people’s experiences, and witnessing accountability processes from the margins and from the center, I strongly believe that the model we have for understanding and responding to rape is deeply flawed. For a long time I have heard criticisms of this model, but on the one hand I never found a detailed explanation of these criticisms and on the other I was trained to assume that anyone criticizing the model was an apologist for rape, going on the defensive because their own patriarchal attitudes were being called out. After personally meeting a number of critical people who were themselves longtime feminists and survivors, I started to seriously question my assumptions.

Since then, I have come to the conclusion that the way we understand and deal with rape is all wrong and it often causes more harm than good. But many of the features of the current model were sensible responses to the Left that didn’t give a damn about rape and patriarchy. Maybe the biggest fault of the model, and the activists who developed it, is that even though they rejected the more obvious patriarchal attitudes of the traditional Left, they unconsciously included a mentality of puritanism and law and order that patriarchal society trains us in. I don’t want to go back to a complicit silence on these issues. For that reason, I want to balance every criticism I make of the current model with suggestion for a better way to understand and deal with rape.

When I was in a mutually abusive relationship, one in which both of us were doing things we should not have done, without being directly aware of it, that resulted in causing serious psychological harm to the other person, I learned some interesting things about the label of “survivor.” It represents a power that is at odds with the process of healing. If I was called out for abuse, I became a morally contemptible person. But if I were also a survivor, I suddenly deserved sympathy and support. None of this depended on the facts of the situation, on how we actually hurt each other. In fact, no one else knew of the details, and even the two of us could not agree on them. The only thing that mattered was to make an accusation. And as the activist model quickly taught us, it was not enough to say, “You hurt me.” We had to name a specific crime. “Abuse.” “Assault.” “Rape.” A name from a very specific list of names that enjoy a special power. Not unlike a criminal code.

I did not want to create an excuse for how I hurt someone I loved. I wanted to understand how I was able to hurt that person without being aware of it at the time. But I had to turn my pain and anger with the other person into accusations according to a specific language, or I would become a pariah and undergo a much greater harm than the self-destruction of this one relationship. The fact that I come from an abusive family could also win me additional points. Everyone, even those who do not admit it, know that within this system having suffered abuse in your past grants you a sort of legitimacy, even an excuse for harming someone else. But I don’t want an excuse. I want to get better, and I want to live without perpetuating patriarchy. I sure as hell don’t want to talk about painful stories from my past with people who are not unconditionally sympathetic towards me, as the only way to win their sympathy and become a human in their eyes.

As for the other person, I don’t know what was going on in their head, but I do know that they were able to deny ever harming me, violating my consent, violating my autonomy, and lying to me, by making the accusation of abuse. The label of “survivor” protected them from accountability. It also enabled them to make demands of me, all of which I met, even though some of those demands were harmful to me and other people. Because I had not chosen to make my accusation publicly, I had much less power to protect myself in this situation.

And as for the so-called community, those who were good friends supported me. Some of them questioned me and made sure I was going through a process of self-criticism. Those who were not friends or who held grudges against me tried to exclude me, including one person who had previously been called out for abuse. In other words, the accusation of abuse was used as an opportunity for power plays within our so-called community.

For all its claims about giving importance to feelings, the activist model is coded with total apathy. The only way to get the ball of community accountability rolling is to accuse someone of committing a specific crime. The role of our most trusted friends in questioning our responses, our impulses, and even our own experiences is invaluable. This form of questioning is in fact one of the most precious things that friendship offers. No one is infallible and we can only learn and grow by being questioned. A good friend is one who can question your behavior in a difficult time without ever withdrawing their support for you. The idea that “the survivor is always right” creates individualistic expectations for the healing process. A survivor as much as a perpetrator needs to be in charge of their own healing process, but those who support them cannot be muted and expected to help them fulfill their every wish. This is a obvious in the case of someone who has harmed someone else it should also be clear in the case of someone who has been harmed. We need each other to heal. But the others in a healing process cannot be muted bodies. They must be communicative and critical bodies.

The term “perpetrator” should set off alarm bells right away. The current model uses not only the vocabulary but also the grammar of the criminal justice system, which is a patriarchal institution through and through. This makes perfect sense: law and order is one of the most deeply rooted elements of the American psyche, and more immediately, many feminist activists have one foot in radical communities and another foot in NGOs (Non-Governmental Organizations). The lack of a critique of these NGOs only makes it more certain that they will train us in institutional modes of thinking.

The current method is not only repulsive for its puritanism and its similarity to the Christian notions of the elect and the damned; it is also a contradiction of queer, feminist, and anarchist understandings of patriarchy. If everyone or most people are capable of causing harm, being abusive, or even of raping someone (according to the activist definition which can include not recognizing lack of consent, unlike the traditional definition which focuses on violent rape), then it makes no sense to morally stigmatize those people as though they were especially bad or dangerous. The point we are trying to make is not that the relatively few people who are called out for abuse or even for rape are especially evil, but that the entire culture supports such power dynamics, to the extent that these forms of harm are common. By taking a self-righteous, “tough on crime” stance, everyone else can make themselves seem like the good guys. But there can’t be good guys without bad guys. This is the same patriarchal narrative of villain, victim, and savior, though in the latter role, instead of the boyfriend or police officer, we now have the community. The term “survivor,” on the other hand, continues to recreate the victimization of the standard term, “victim,” that it was designed to replace.

One reason for calling someone a “survivor” is to focus on their process of overcoming the rape, even though it defines them perpetually in relation to it. The other reason is to spread awareness of how many thousands of people, predominately women, queer, and trans people, are injured or killed every year by patriarchal violence. This is an important point to make. However, given the way that rape has been redefined in activist circles, and the extension of the term “survivor” to people who suffer any form of abuse, the vast majority of things that constitute rape or abuse do not have the slightest possibility of ending someone’s life. This term blurs very different forms of violence.

Hopefully, the reader is thinking that an action does not need to be potentially lethal to constitute a very real form of harm. I absolutely agree. But if that’s the case, why do we need to make it sound like it does in order to take it seriously? Why connect all forms of harm to life-threatening harm instead of communicating that all forms of harm are serious?

As for these crimes, their definitions have changed considerably, but they still remain categories of criminality that must meet the requirements of a certain definition to justify a certain punishment. The activist model has been most radical by removing the figure of the judge and allowing the person harmed to judge for themselves. However, the judge role has not been abolished, simply transferred to the survivor, and secondarily to the people who manage the accountability process. The act of judging still takes place, because we are still dealing with punishment for a crime, even if it is never called that.

The patriarchal definition of rape has been abandoned in favor of a new understanding that defines rape as sex without consent, with whole workshops and pamphlets dedicated to the question of consent. Consent must be affirmative rather than the absence of a negative, it is cancelled by intoxication, intimidation, or persistence, it should be verbal and explicit between people who don’t know each other as well, and it can be withdrawn at any time. The experience of a survivor can never be questioned, or to put it another way an accusation of rape is always true. A similar formulation that sums up this definition is, “assault is when I feel assaulted.”

I don’t want to distinguish rape from other forms of harm without talking about how to address all instances of harm appropriately. One solution that does not require us to judge which form of harm is more important, but also does not pretend they are all the same, would have two parts. The first part is to finally acknowledge the importance of feelings, by taking action when someone says “I have been hurt,” and not waiting until someone makes an accusation of a specific crime, such as abuse or rape. Because we are responding to the fact of harm and not the violation of an unwritten law, we do not need to look for someone to blame. The important thing is that someone is hurting, and they need support. Only if they discover that they cannot get better unless they go through some form of mediation with the other person or unless they gain space and distance from them, does that other person need to be brought into it. The other person does not need to be stigmatized, and the power plays involved in the labels of perpetrator and survivor are avoided.

The second part changes the emphasis from defining violations of consent to focusing on how to prevent them from happening again. Every act of harm can be looked at with the following question in mind: “What would have been necessary to prevent this from happening.” This question needs to be asked by the person who was harmed, by their social circle, and if possible by the person who caused the harm.

The social circle is most likely to be able to answer this question when the harm relates to long-term relationships or shared social spaces. They might realize that if they had been more attentive or better prepared they would have seen the signs of an abusive relationship, expressed their concern, and offered help. Or they might realize that, in a concert hall they commonly use, there are a number of things they can all do to make it clear that groping and harassing is not acceptable. But in some situations they can only offer help after the fact. They cannot be in every bedroom or on every dark street to prevent forms of gender violence or intimate violence that happen there.

In the case of the person who caused the harm, the biggest factor is whether they are emotionally present to ask themselves this question. If they can ask, “what could I have done to not have hurt this person,” they have taken the most important step to identifying their own patriarchal conditioning, and to healing from unresolved past trauma if that’s an issue. If they are emotionally present to the harm they have caused, they deserve support. Those closest to the person they hurt may rightfully be angry and not want anything to do with them, but there should be other people wiling to play this role. The person they have hurt deserves distance, if they want it, but except in extreme cases it does no good to stigmatize or expel them in a permanent way.

If they can ask themselves this question honestly, and especially if their peers can question them in this process, they may discover that they have done nothing wrong, or that they could not have known their actions would have been harmful. Sometimes, relationships simply hurt, and it is not necessary to find someone to blame, though this is often the tendency, justified or not. The fact that some relationships are extremely hurtful but also totally innocent is another reason why it is dangerous to lump all forms of harm together, presupposing them all to be the result of an act of abuse for which someone is responsible.

If their friends are both critical and sympathetic, they are most likely to be able to recognize when they did something wrong, and together with their friends, they are the ones in the best position to know how to change their behavior so they don’t cause similar harm in the future. If their friends have good contact with the person who was hurt (or that person’s friends), they are more likely to take the situation seriously and not let the person who caused the harm off the hook with a band-aid solution. This new definition is a response to the patriarchal definition, which excuses the most common forms of rape (rape by acquaintances, rape of someone unable to give consent, rape in which someone does not clearly say “no”). It is a response to a patriarchal culture that was always making excuses for rape or blaming the victim.

The old definition and the old culture are abhorrent. But the new definition and the practice around it do not work. We need to change these without going back to the patriarchal norm. In fact, we haven’t fully left the patriarchal norm behind us. Saying “assault is when I feel assaulted” is only a new way to determine when the crime of assault has been committed, keeping the focus on the transgression of the assaulter, then we still have the mentality of the criminal justice system, but without the concept of justice or balance. At the other extreme, there are people who act inexcusably and are totally unable to admit it. Simply put, if someone hurts another person and they are not emotionally present in the aftermath, simply put, it is impossible to take their feelings into consideration. You can’t save someone who doesn’t want help. In such a case, the person hurt and their social circle need to do what is best for themselves, both to heal and to protect themselves from a person they have no guarantee will treat them well in the future. Maybe they will decide to shame that person, frighten them, beat them up, or kick them out of town. Although kicking them out of town brings the greatest peace of mind, it should be thought of as a last resort, because it passes off the problem on the next community where the expelled person goes. Because it is a relatively easy measure it is also easy to use disproportionately. Rather than finding a solution that avoids future conflict, it is better to seek a conflictive solution. This also forces people to face the consequences of their own righteous anger which can be a learning process.

Finally, the most important question comes from the person who was hurt. The victimistic mentality of our culture, along with the expectation that everyone is out to blame the victim, make it politically incorrect to insist the person who has been hurt ask themselves, “what would have made it possible to avoid this?” but such an attitude is necessary to overcoming the victim mentality and feeling empowered again. It is helpful for everyone who lives in a patriarchal world where we will probably encounter more people who try to harm us. Its not about blaming ourselves for what happened, but about getting stronger and more able to defend ourselves in the future.

I know that some zealous defenders of the present model will make the accusation that I am blaming the victim, so I want to say this again: it’s about preventing future rapes and abuse, not blaming ourselves if we have been raped or abused. The current model basically suggests that people play the role of victims and wait for society or the community to save them. Many of us think this is bullshit. Talking with friends of mine who have been raped and looking back at my own history of being abused, I know that we grew stronger in certain ways, and this is because we took responsibility for our own health and safety.

In some cases, the person who was hurt will find that if they had recognized certain patterns of dependence or jealousy, if they had had more self-esteem, or they had asserted themselves, they could have avoided being harmed. Unless they insist on retaining a puritan morality this is not to say that it was their fault. It is a simple recognizing of how they need to grow in order to be safer and stronger in a dangerous world. This method focuses not on blame, but on making things better.

Sometimes, however, the person will come to the honest conclusion, “there was nothing I could have done (except staying home / having a gun / having a bodyguard).” This answer marks the most extreme form of harm. Someone has suffered a form of violence that they could not have avoided because of the lengths the aggressor went to in order to override their will. Even shouting “No!” would not have been enough. It is a form of harm that cannot be prevented at an individual level and therefore it will continue to be reproduced until there is a profound social revolution, if that ever happens.

If we have to define rape, it seems more consistent with a radical analysis of patriarchy to define rape as sex against someone’s will. Because will is what we want taken into the realm of action, this idea of rape does not make the potential victim dependent on the good behavior of the potential rapist. It is our own responsibility to depress our will. Focusing on expressing and enacting our will directly strengthens ourselves as individuals and our struggles against rape and all other forms of domination.

If rape is all sex without affirmative consent, then it is the potential rapist, and not the potential victim, who retains the power over the sexual encounter. They have the responsibility to make sure the other person gives consent. If it is the sole responsibility of one person to receive consent from another person, then we are saying that person is more powerful then the other, without proposing how to change those power dynamics.

Additionally, if a rape can happen accidentally, simply because this responsible person, the one expected to play the part of the perfect gentleman, is inattentive or insensitive, or drunk, or oblivious to things like body language that can negate verbal consent, or from another culture with a different body language, then we’re not necessarily dealing with a generalized relationship of social power, because not everyone who rapes under this definition believes they have a right to the other person’s body.

Rape needs to be understood as a very specific form of harm. We can’t encourage the naive ideal of a harm-free world. People will always hurt each other, and it is impossible to learn how not to hurt others without also making mistakes. As far as harm goes, we need to be more understanding than judgmental. But we can and must encourage the ideal of a world without rape, because rape is the result of a patriarchal society teaching its members that men and other more powerful people have a right to the bodies of women and other less powerful people. Without this social idea, there is no rape. What’s more, rape culture, understood in this way, lies at least partially at the heart of slavery, property, and work, at the roots of the State, capitalism, and authority.

This is a dividing line between one kind of violence and all the other forms of abuse. It’s not to say that the other forms of harm are less serious or less important. It is a recognition that the other forms of harm can be dealt with using less extreme measures. A person or group of people who would leave someone no escape can only be dealt with through exclusion and violence. Then it becomes a matter of pure self-defense. In all the other cases, there is a possibility for mutual growth and healing. Sympathetic or supportive questioning can play a key role in responses to abuse. If we accept rape as a more extreme form of violence that the person could not have reasonably avoided, they need the unquestioning support and love of their friends.

We need to educate ourselves how systematically patriarchy has silenced those who talk about being raped through suspicion, disbelief, or counter accusations. But we also need to be aware that there have been a small number of cases in which accusations of rape have not been true. No liberating practice should ever require us to surrender our own critical judgement and demand that we follow a course of action we are not allowed to question. Being falsely accused of rape or being accused in a non-transparent way is a heavily traumatizing experience. It is a far less common occurrence than valid accusations of rape that the accused person denies, but we should never have to opt for one kind of harm in order to avoid another.

If it is true that rapists exist in our circles, it is also true that pathological liars exist in our circles. There has been at least one city where such a person made a rape accusation to discredit another activist. People who care about fighting patriarchy will not suspect someone of being a pathological liar every time they are unsure about a rape accusation. If you are close to someone for long enough, you will inevitably find out if they are a fundamentally dishonest person (or if they are like the rest of us, sometimes truthful, sometimes less so).

Therefore, someone’s close acquaintances, if they care about the struggle against rape culture, will never accuse them of lying if they say they’ve been raped. But often accusations spread by rumors and reach people who do not personally know the accuser and the accused. The culture of anonymous communication through rumors and the internet often create a harmful situation in which it is impossible to talk about accountability or about the truth of what happened in a distant situation.

Anarchists and other activists also have many enemies who have proven themselves capable of atrocities in the course of repression. A fake rape accusation is nothing to them. A police infiltrator in Canada used the story of being a survivor of an abusive relationship to avoid questions about her past and win the trust of anarchists she would later set up for prison sentences. Elsewhere, a member of an authoritarian socialist group made an accusation against several rival anarchists, one of whom, it turned out, was not even in town on the night in question. Some false accusations of rape are totally innocent. Sometimes a person begins to relive a previous traumatic experience while in a physically intimate space with another person, and it is not always easy or possible to distinguish between the one experience and the other. A person can begin to relive a rape while they are having consensual sex. It is definitely not the one person’s fault for having a normal reaction to trauma, but it is also not necessarily the other person’s fault that the trauma was triggered.

A mutual and dynamic definition of consent as active communication instead of passive negation would help reduce triggers being mislabeled as rape. If potential triggers are discussed before the sexual exchange and the responsibility for communicating needs and desires around disassociation is in the hands of the person who disassociated then consent is part of an active sexual practice instead of just being an imperfect safety net. If someone checks out during sex, and they know they check out during sex, it is their responsibility to explain what that looks like and what they would like the other person to do when it happens. We live in a society where many people are assaulted, raped or have traumatic experiences at some point in their lives. Triggers are different for everyone. The expectation that ones partner should always be attuned enough to know when one is disassociating, within a societal context that does not teach us about the effects of rape, much less their intimate emotive and psychological consequences — is unrealistic.

Consent is empowering as an active tool, it should not be approached as a static obligation. Still, the fact remains that not all rape accusation can be categorized as miscommunication, some are in fact malicious.

There is a difficult contradiction between the fact that patriarchy covers up rape, and the fact that there will be some false, unjustified, or even malicious rape accusations in activist communities. The best option is not to go with statistical probability and treat every accusation as valid, because a false accusation can tear apart an entire community make people apathetic or skeptical towards future accountability processes. It is far better to educate ourselves, to be aware of the prevalence of rape, to recognize common patterns of abusive behavior, to learn how to respond in a sensitive and supportive way, and also to recognize that there are some exceptions to the rules, and many more situations that are complex and defy definition.

The typical proposal for responding to rape, the community accountability process, is based on a transparent lie. There are no activist communities, only the desire for communities, or the convenient fiction of communities. A community is a material web that binds people together, for better and for worse, in interdependence. If its members move away every couple years because the next pace seems cooler, it is not a community. If it is easier to kick someone out than to go through a difficult series of conversations with them, it is not a community. Among the societies that had real communities, exile was the most extreme sanction possible, tantamount to killing them. On many levels, losing the community and all the relationships it involved was the same as dying. Let’s not kid ourselves: we don’t have communities. In many accountability processes, the so-called community has done as much harm, or acted as selfishly, as the perpetrator. Giving such a fictitious, self-interested group the power and authority of judge, jury, and executioner is a recipe for disaster.

What we have are groups of friends and circles of acquaintances. We should not expect to be able to deal with rape or abuse in a way that does not generate conflict between or among these different groups and circles. There will probably be no consensus, but we should not think of conflict as a bad thing. Every rape is different, every person is different, and every situation will require a different solution. By trying to come up with a constant mechanism for dealing with rape, we are thinking like the criminal justice system. It is better to admit that we have no catch-all answer to such a difficult problem. We only have our own desire to make things better, aided by the knowledge we share. The point is not to build up a structure that becomes perfect and unquestionable, but to build up experience that allows us to remain flexible but effective.

The many failings in the current model have burned out one generation after another in just a few short years, setting the stage for the next generation of zealous activists to take their ideals to the extreme, denouncing anyone who questions them as apologists, and unaware how many times this same dynamic has played out before because the very model functions to expel the unorthodox, making it impossible to learn from mistakes. One such mistake has been the reproduction of a concept similar to the penal sentence of the criminal justice system. If the people in charge of the accountability process decide that someone must be expelled, or forced to go to counseling, or whatever else, everyone in the so-called community is forced to recognize that decision. Those who are not are accused of supporting rape culture. A judge has a police force to back up his decision. The accountability process has to use accusations and emotional blackmail.

But the entire premise that everyone has to agree on the resolution is flawed. The two or more people directly involved in the problem may likely have different needs, even if they are both sincerely focused on their own healing. The friends of the person who has been hurt might be disgusted, and they might decide to beat the other person up. Other people in the broader social circle might feel a critical sympathy with the person who hurt someone else, and decide to support them. Both of these impulses are correct. Getting beaten up as a result of your actions, and receiving support, simply demonstrate the complex reactions we generate. This is the real world, and facing its complexity can help us heal.

The impulse of the activist model is to expel the perpetrator, or to force them to go through a specific process. Either of these paths rest on the assumption that the community mechanism holds absolute right, and they both require that everyone complies with the decision and recognize its legitimacy. This is authoritarianism. This is the criminal justice system, recreated. This is patriarchy, still alive in our hearts.

What we need is a new set of compass points, and no new models. We need to identify and overcome the mentalities of puritanism and law and order. We need to recognize the complexity of individuals and of interpersonal relationships. To avoid a formulaic morality, we need to avoid the formula of labels and mass categories. Rather than speaking of rapists, perpetrators, and survivors, we need to talk abut specific acts and specific limitations, recognizing that everyone changes, and that most people are capable of hurting and being hurt, and also of growing, healing, and learning how to not hurt people, or not be victimized, in the future. We also need to make the critical distinction between the forms of harm that can be avoided as we get smarter and stronger, and the kinds that require a collective self-defense.

The suggestions I have made offer no easy answers, and no perfect categories. They demand flexibility, compassion, intelligence, bravery, and patience. How could we expect to confront patriarchy with anything less?

0 notes

Text

Linux adds a code of conduct for programmers

If you follow Linux development closely, you know Linux kernel discussions can be very heated. Recently, Linus Torvalds has admitted the Linux Kernel Mailing List (LKML) and other Linux development spaces are hostile to many. Torvalds announced he’d change his behavior and apologized to the “people that my personal behavior hurt and possibly drove away from kernel development.” It was never just Torvalds. So, the Linux community announced it’s adopting, for the first time, a “Code of Conduct.”

Also: How to choose a Linux distro for your old PC CNET

Linux developers had a code before, but the earlier “Code of Conflict,” failed to make the kernel community a more civil group. As Greg Kroah-Hartman, a leading Linux kernel developer wrote, the “Code of Conflict is not achieving its implicit goal of fostering civility and the spirit of ‘be excellent to each other.’ Explicit guidelines have demonstrated success in other projects and other areas of the kernel.”

This new code is straightforward. It opens:

“In the interest of fostering an open and welcoming environment, we as contributors and maintainers pledge to making participation in our project and our community a harassment-free experience for everyone, regardless of age, body size, disability, ethnicity, sex characteristics, gender identity and expression, level of experience, education, socio-economic status, nationality, personal appearance, race, religion, or sexual identity and orientation.”

Moving ahead, the Linux code maintainers will be be charged with encouraging welcoming behavior and eliminating sexualized language, trolling, harassment, and other unprofessional behavior. You would think this new code wouldn’t cause too much conflict. You would be wrong.

Also: How to find the right Linux distribution for you TechRepublic

This new code is based on the Contributor Covenant. This open-source code of conduct is already being used by such projects as Eclipse, Kubernetes, and Rails. It was created by Coraline Ada Ehmke, a software developer and open-source advocate.

The use of her Contributor Covenant has caused a bad-tempered outbreak on Twitter and Reddit. There are claims the Linux community is becoming politicized and is being taken over by so-called Social Justice Warriors (SJW). Some examples concerning the new Code of Conduct include: “In practice [will be] abused tools to hunt people SJWs don’t like. And they don’t like a lot of people.” And, “Yes as long as are authoritarian left wing minded, and/or censor your self you can participate.”

Also: Opera is available in a Snap on Linux

For all the ranting about SJWs on Twitter and Reddit, things are quite calm on the LKML Itself. It’s very telling that the people actually working on Linux are not freaking out about the new code of conduct.

As for what happens next? Sage Sharp, a developer who left the Linux community because of its toxic environment, tweeted it best: “The real test here is whether the community that built Linus up and protected his right to be verbally abusive will change. Linus not only needs to change himself, but the Linux kernel community needs to change as well.”

We’ll see what happens.

Related stories:

The post Linux adds a code of conduct for programmers was shared from BlogHyped.com.

Source: https://bloghyped.com/%e2%80%8blinux-adds-a-code-of-conduct-for-programmers/

0 notes