#this book is from 2006 and that little line provides representation that a lot of current media still lacks

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Queer representation in the book Mr Monk Goes to the Firehouse? It’s more likely than you think.

#the gasp i let out when i saw the part about people who fall somewhere in between#this book is from 2006 and that little line provides representation that a lot of current media still lacks#monk#mr monk#adrian monk#natalie teeger#julie teeger#queer representation#gay representation#lesbian representation#nonbinary representation

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

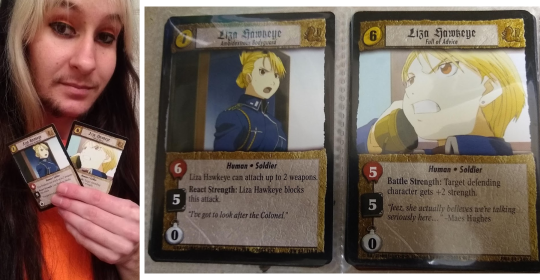

Some Incomplete Ramblings on “Liza / Riza Hawkeye”

One thing I’ve always found fascinating about FMA character / location names is that it’s like a game of telephone from European languages --> Japanese --> (in my case) English. As is such, with telephone, information has the potential to get distorted.

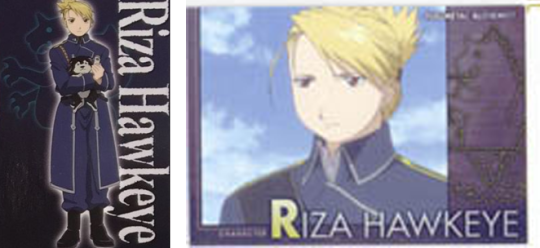

I own lots of FMA guidebooks in English and Japanese, and frequently entertain myself with the name variations. Liore / Leole / Reole / etc. is one of the most entertaining spelling conundrums, official sources constantly varying the name, and never honing in on a consensus over the many years’ passings. But while I could yab on about Martel and Ling and Dolcetto and Kimblee and many other names, I’m here to smile about Riza Hawkeye.

Official sources in English and Japanese almost exclusively spell her name as “Riza Hawkeye.” Over and over, it’s Riza Hawkeye. Compared to many characters, her name’s very consistent. But in some of the earliest materials from the franchise, she’s sometimes labeled as “Liza Hawkeye.” For instance, there’s an early Bandai figure with that name - a figure that would have been developed (and its label created) through Japan.

The English version of the Fullmetal Alchemist Trading Card game sometimes calls her Liza, too. Because I’m a linguist who (as my career probably implies) loves Little Language Things... I had to nab a few FMA trading cards with that variant name! I don’t collect cards, but these were irresistible! These cards came in my mail yesterday!!! Tadaaaa!

It’s hard to see in the photograph, but these cards are copyright 2005. I’ve tried to find more information on when in 2005 they were printed (no success yet), but the date 2005 is interesting. This isn’t long after the first anime’s English dub began premiering in the USA starting November 2004.

These cards may also have preceded the first official English manga publications. The manga received two official printings in English, one by Viz Media in the USA and one by Chuang Yi in Singapore. Viz Media published Vol. 1′s First Edition in May 2005; Chuang Yi was November 2005. I doubt there’d be any coordination between different companies in different parts of the world creating cards and manga and anime. Different name interpretations were far more likely to happen with FMA being turned into English for the first times. There was no established precedent for how-to-spell-what. As everyone in 2005 was working through their stuff independently or semi-independently, they were giving our girl a different first name.

Now, Riza’s name had been published in the Roman alphabet as “Riza Hawkeye” earlier than when my cards came out. The Japanese company Bandai (that gave us the Liza Hawkeye figure)... also gave us a 2003 card calling her “Riza Hawkeye.” That is, within the same company within a short amount of time, they printed two different spellings of a character’s name. There’s another card set, from 2004, that lists her as “Riza Hawkeye” as well.

After FMA’s nascent years, Hawkeye’s Roman-spelled name quickly became solidified as “Riza.” Almost all “Liza” materials I’ve seen are 2005 or earlier. The latest material I’ve seen listed as “Liza” is a card with a copyright of 2007.

The English release of the two most important FMA franchise materials - the manga and the anime - would have solidified Hawkeye’s first name as “Riza.” On September 17, 2005, Riza’s full name was stated on screen for the first time in the English airdate... as “First Lieutenant Riza Hawkeye.” This was in Ep. 27 “Teacher.”

Viz Media worked alongside all this. Viz Media published both the English anime book materials (like Fullmetal Alchemist Anime Profiles, printed in English in 2006) and the manga itself. I believe the first time Riza’s first name was given in the manga was Chapter 24, when Riza introduced herself to Winry. Viz Media printed Vol. 6 (which contains Ch. 24) in February 2006. By this point, for English-speaking fans (especially in the Western Hemisphere), all major FMA materials would have called her “Riza.”

I imagine that by then, that now-iconic name would have been foolish to change. One of the most popular characters was branded firmly as “Riza” by the start of 2006. Couldn’t change that now. Unlike the earliest merchandise, now everything about Riza - both English and Japanese materials - called her Riza. All my Japanese guidebooks that never got English translations call her “Riza.” (And these are guidebooks that continue to have Roman alphabet spelling variations between other characters - even when all published in the same year). None variation left beef for Riza. I want to buy the Perfect Guidebooks, which are older than all the guidebooks I currently own, and see what they say for her name... but for now... everything I’m holding that’s in Japanese is post-2006 and all say “Riza” when they print her name in Roman letters.

I don’t know what Arakawa intended, especially as the earliest Japanese merchandise gives us both Riza and Liza. If the earliest merchandise all said one name, we could have guessed that Arakawa gave the approval. But that’s not the case. The names vary in early Japanese Bandai merch. Nor can we trust major English translated sources as hints of Arakawa’s intentions. It doesn’t seem like they asked Arakawa for explanation on everyone’s intended names. Viz doesn’t provide a good representation on what Arakawa wanted, given as they messed up majorly on other names and are only correcting them NOW, in 2018 and 2019, in their Fullmetal Edition of the manga (in the trade paperbacks, they called Kyle Halling “Khayal,” spelled Kimblee’s name two different ways, wrote “Isvharlan” in Vol. 2, gave the country’s name as “Ishbal” above drawings from the manga that wrote “Ishval,” misinterpreted Xerxes as “Cselkcess,” and lots of other fun oddities...).

And while some names get written in English in the manga artwork proper, I’ve only seen Hawkeye’s last name.

I know far from everything. There’s still lots I have to check. Don’t take my word as law.

THAT SAID.

From the information I know... I find it fascinating it’s VERY possible Arakawa’s initial inspiration was “Liza Hawkeye.” NOT Riza. There’s in fact good linguistic reason to suppose this.

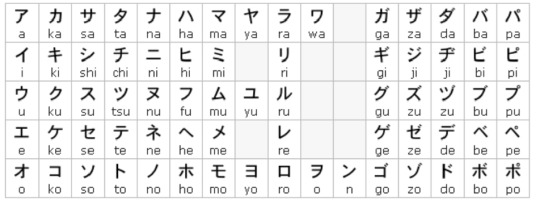

For people who aren’t familiar with Japanese typography / orthography, the Japanese writing system is composed of kanji and kana. Kanji are characters with semantic complexity to them; the kanji are usually included in a word for meaning-related reasons, but the pronunciation of the kanji can vary depending upon whether the word it contextually represents is a native Japanese word, a Chinese loan word, the first or second kanji in a compound, etc. Kana, unlike kanji, are basically read the same way every time. Instead of being symbols depicting semantic content, kana depict pronunciation content. Kana are written in a syllabary system. A syllabary is like an alphabet except that every symbol represents a syllable you pronounce (or, in Japanese, a mora). Japanese kana are two sets of syllabaries, the hiragana and katakana. Katakana is used to spell recently adopted loan words.

Because FMA characters’ names are (almost) all taken from European names, their names are written in katakana. But because Japanese is a different language than European languages, it has different sounds in it. This means that, when European loan words get imported into Japanese, pronunciation changes happen. The pronunciations allowed in European languages are altered into acceptable sound structures Japanese allows - its phonetics and phonology and phonotactics.

Now, Arakawa doesn’t always spell European words “typically” for katakana. Japanese has over the last few decades adopted many English loanwords. For instance, there’s a loan word for “mustang,” which is 「 ムスタング 」. Roughly, ム = mu, ス = su, タ = ta, ン = n, and グ = gu. So, the Japanese word for “mustang” is musutangu. Arakawa actually gives Colonel Mustang a different spelling than that - he’s masutangu 「 マスタング 」.

Perhaps this was because Arakawa saw the name “Mustang” in Roman letters and did her own import into kana. In the process of her changing “Mustang” from Roman letters to katakana, she might have chosen “ma” instead of “mu”. Perhaps this was because she thought this would make his name sound cooler, look unique, or make her metaphoric name more subtle. Or, perhaps this arose in foresight with the eventual “Madame Christmas” wordplay (“Christmas” in Japanese is 「 クリスマス」kurisumasu, which makes her full name kurisu masutangu - get how that works perfectly?). Whatever the reason(s), we know that Arakawa’s katakana spelling of imported European words isn’t always what Japanese’s loan word katakana spelling officially does.

Riza’s name in the Japanese could be another instance of this.

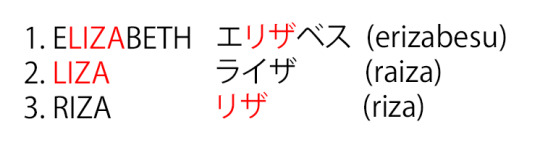

To explain what I mean, let’s take a look at my graphic:

Each line is a name in Roman letters (acceptable in English) with its corresponding Japanese spelling. In parentheses is a rough pronunciation of how that katakana’s pronounced.

First: There are indications that Riza’s full given name is Elizabeth. Some fans say it’s just her code name, akin to how “Jaqueline” is Havoc’s code name. It’s true we hear Roy call her “Elizabeth” in that code name setting. However, it’s also interesting that he calls her “Elizabeth” when he’s visiting Madame Christmas. In his home environment, where he’s dropping his walls and being far more honest and open to family, where he’s even blabbing about being romantically interested in Hawkeye OUT LOUD, he calls her “Elizabeth.” You could argue that it might be another instance of intentional code naming to protect her identity, but it’s still very interesting that this is a second, different, emotionally open, trusting context in which Roy names her “Elizabeth.”

Linguistically, her name seems derived from “Elizabeth,” too. Again: while spellings and pronunciations are slightly altered when Arakawa imports European names into Japanese, she’s still taking those names from a European source. But I don’t know of a common Western European name that’s essentially Riza. Go to baby names websites. You don’t get a long list of female names that are Riza, especially not in Western Europe, where Arakawa took most names. Where’d she get this?

A shortening of “Elizabeth” is likely.

Look at Line #1 of my graphic. I have the word “Elizabeth” in Roman letters alongside the katakana spelling of “Elizabeth.”

That first line is how “Elizabeth” is usually spelled in Japanese writing. It’s 「エリザベス」. エ = e, リ = ri, ザ = za, ベ = be, and ス = su. So the Japanese version of “Elizabeth” is more or less erizabesu. Note that the same symbol 「リ」is used for both r+i and l+i. This could be a long linguistics explanation in itself, but more or less: Japanese doesn’t have separate “r” and “l” sounds. They have one sound that’s like an “r.” But, it has pronunciation variation based upon dialect, and, within a single dialect, where said “r” is placed in relation to other sounds surrounding it. The “r” can make lots of sounds (allophones), including what English speakers would call an “l.” So when imported words from European languages which have separate r and l sounds (phonemes), these r’s and l’s get reduced in Japanese into one thing, interpreted as that single “r” sound their language has.

Now, let’s go to Line #2. A common nickname for “Elizabeth” is “Liza.” Notice the spelling. Elizabeth contains the actual, unaltered spelling of Liza. However, pronunciation changes occur. The “i” in “Elizabeth” is a different sound than the “i” in “Liza.” The spelling’s the same between full name and nickname; the first vowel just sounds different.

The Japanese katakana spelling of “Liza” is based upon the pronunciation. NOT the spelling! See my visual. The way “Liza” is spelled in Japanese is 「ライザ」- that is, raiza. ラ = ra, イ = i, and ザ = za. As a result, the name “Elizabeth” in katakana does not contain the unaltered spelling of “Liza” inside it.

Note, however, that the name **RIZA** is DIRECTLY spelled inside the Japanese spelling of “Elizabeth.” 「エリザベス」 contains 「リザ」. That is, erizabesu can be truncated to riza without any spelling changes!

That’s what we see in Line #3. Note that, in red, I have highlighted where the spellings stay the same within full name and nickname.

Ergo, “Riza” is directly derived from “Elizabeth” in the katakana spelling of “Elizabeth.” That’s indirect indication that, when Arakawa was giving Riza her name, she was looking at “Elizabeth.”

In which case, “Liza” WOULD be a correct reading for Hawkeye’s first name.

Similar to the Chris Mustang thing I mentioned, making a spelling change for an “Elizabeth” nickname makes sense in Japanese. Japanese readers might not be familiar that “Liza” is a nickname for “Elizabeth.” The fact that raiza for “Liza” is spelled very different in Japanese kana compared to erizabesu for “Elizabeth” ...would make it hard to connect the dots between the two names. But giving the spelling riza makes the connection easier-to-see: for them, in katakana, they can see riza spelled inside erizabesu. Just like, in English, we can see “Liza” directly inside “Elizabeth.”

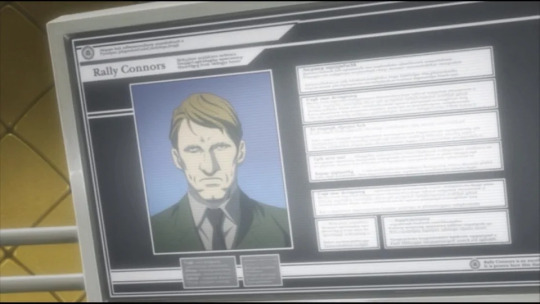

So, from what I know, I postulate that Arakawa initially envisioned “Liza Hawkeye.” It all makes linguistic sense, and the fact that early FMA merchandise from Japan sometimes uses “Liza” only helps my case. That they sometimes also called her “Riza” is a common phenomenon of Japanese publications not knowing when to make something an R and when to make something an L. I mean, in the Death Note anime, you see someone’s name listed as “Rally” instead of “Larry.” The L/R confusion is common and appears commonly in officially released Japanese materials.

I mentioned at the start of this ramble that translating names multiple times is like a game of telephone. Thus far, it seems like we went from Liza --> リザ. Then, when North American native English speakers got the Japanese 「リザ」, they had to figure out what to do with it. Because the character’s name was spelled 「リザ」 - NOT the standard「ライザ」 Japanese use to spell “Liza” - then translators wouldn’t have thought this was an intended “Elizabeth” nickname. It doesn’t help that Roy doesn’t call Riza “Elizabeth” as code until several volumes after we’re given riza (Ch. 37 Vol. 9, I believe). So, translators were left with a really oddly spelled, indeterminate name... something that could have been spelled “Leeza” or “Reeza” or “Riza” or “Leaza” or who-knows-what. But “Liza” would have, to them, seemed like a phonetically poor choice - English readers would see “Liza” and pronounce it very differently from how the Japanese would pronounce 「リザ」. If Arakawa had intended “Liza,” she would have spelled it markedly differently, right? So “Liza” would have been an unintuitive translation option for Japanese --> English translators. On the other hand, English readers would see “Riza” and pronounce it close to how the character’s name was spelled in Japanese. So even though “Riza” isn’t a normal Western European name, that’s what seemed to make sense. Ergo, “Riza” became the “intuitive” choice for translators, and that’s what they put.

It’s not unfeasible that this “Riza” choice was made independently with several groups of people - the manga translators and the English dub script workers, namely. “Riza” seems the most default “sensible” choice. And once both Viz Media and Funimation Entertainment gave English consumers, consistently, “Riza” - well that was that! It probably influenced Japanese publishers with their next materials. It would have influenced all other English products. Thus, henceforth, Japanese or English origin, we’d only see her name as “Riza”.

Don’t take this as a flawless or conclusive analysis. Opening the Perfect Guidebooks, after I buy them, might tweak or solidify some of my thoughts. There’s many materials, other merchandise, I haven’t seen the packaging to, or seen inside of, or know what year it was made. I might not have accurately remembered / researched the first instances in which names were given across the animes, manga, etc. I don’t know hoards about the Trading Card game. I’m not fluent in Japanese, just a beginner. I’m a linguist but academically I spent little time with Japanese in my studies and research. I definitely can’t mind read Arakawa. Other fans may know more(?). This is meant as a happy ramble of thoughts, not a conclusion. And I wrote this overnight instead of getting sleep. Because this is a wise use of time, right?

I will always call her “Riza.” The name fits her. It’s a unique name. It’s a cool name. I think it sounds better than “Liza Hawkeye.” I grew up with “Riza.” I’m attached to Riza.

But I find it so fascinating to acknowledge and study the background of when she was labeled “Liza.”

I’m quite happy to be hold cards from 2005 - in my hand - that label her such.

#long post#non-dragons#Riza Hawkeye#FMA#Fullmetal Alchemist#Fullmetal Alchemist Brotherhood#Fullmetal Alchemist: Brotherhood#FMA 2003#Fullmetal Alchemist 2003#analysis#my analysis#linguistics#close enough#I've thought about this for a while and chatted in private with irl or url friends on this#first time I'm posting some of my name variation thoughts online#I seriously#have thought#LOTS#about the name variations and telephone game in FMA#looooooooots#I love it so much it's just INTERESTING#UPDATE: I fixed a major typo#whooooops#watch the old version circulate more though hahaha that's always how it works XD

666 notes

·

View notes

Text

Everything A Real Estate Agent Doesn't Want You To Know, A Year In Review 2006

Through 2006 I have written a number of articles known as the "Everything A Real Estate Agent Doesn't Want You To Know" series which has long been a consumer oriented series of information to help home purchasers and sellers protect themselves when conducting a real residence transaction. These articles are a natural extension of courses I have written known as "Everything A Real Estate Agent Doesn't Want Your house Buyer To Know" and "Everything A Real Estate Agent Doesn't Really want A Home Seller To Know". The first book written through 1990 was called "Everything A Real Estate Agent Doesn't Want You to definitely Know" and it had a fair degree of national success, extra than I thought it would, when I introduced it towards the media during 1991/92. We sold the book in each state in the U. S. including Alaska, Hawaii and since far as Pakistan and Japan. This was not a damaging performance for a self-published under-funded author. I wrote the book because I was a licensed real estate agent in the talk about of Ohio and, more importantly, I was a readily available mortgage banker for a few years and I saw a large number of home buyers and sellers experience financial damage as a result of dealing with inexperienced and unethical real estate agents. Many of the agents happen to be either totally incompetent or so self interested that they would certainly mislead buyers and sellers, anything to get them to indication a purchase offer or a listing contract. Many of these family home buyers and sellers who were cut through the neck and also didn't even realize they were bleeding because they lacked understanding and insight into how the real estate game is competed. These books have always caused friction between real estate agents and myself because many agents resent the heading of the books and the ill conceived premise that the position is that all agents are bad crooked people today, which is false. In fact , whenever I did a media gig I always made it a point to clarify this is NOT a baby blanket indictment against real estate agents. There are good, honest, knowledgeable, full time mum real estate agents in the business who are highly professional. The problem is they are the particular minority and not the majority. The major problem with the real estate market place as a whole is the ease with which a person can get a realty license. While the educational requirements vary from state to state, normally, anybody can get a license to sell real estate in about 90 days. This just doesn't make sense to me. Consider that many realtors are little old women who operate part-time, do not have business or selling background, go to school for 33 or 90 days and are licensed to represent home owners in property transactions from around $50, 000. 00 and up. I mean, a lawyer has to go to school for more effective years to get a license to write a fifty-dollar will or perhaps represent somebody in a petty traffic accident. But silly-sally can go to school for 30 days and list the $250, 000 house for sale? That does not compute in my thought process. What kind of representation will a seller get from a in someones spare time agent with one toe in the tub? And the full-time pros know what I am talking about. I have had many close interactions with agents while I was in the business and the the important point is that part timers are often the weakest relationship in getting a deal done, unavailable for showings, etc . The bottom line, part time agents give part time results if you are a buyer, seller or a full time agent attempting make a living. And the truth is that most people, especially first time residential buyers and sellers don't know what is going on... not really. How you find an agent to sell a home, the nature of contract law as well as negotiable elements of listing contracts, purchase contracts, etc . will be way beyond most first time buyers and sellers. The actual result is that sellers sign stupid long-term listing agreements with the wrong agents and the wrong companies and individuals pay way more for property then they would if they received more insight into the workings of real estate transactions including commissioned real estate sales agents. I didn't originate the problem, I identified the problems and the solutions for home buyers plus sellers. CAVEAT EMPTOR is legal jargon which means "buyer beware" and it means what it says. Whether you happen to be a home seller or home buyer, you better determine what you are doing when you are making decisions and signing contracts for the reason that, it is your duty to know and ignorance is no alibi under the law. If you do a stupid real estate deal, it will be your fault. Which is a shame because buying or selling a home is actually a BIG business decision. It is a business transaction composed of individuals, emotions, contracts and cash and those are all the compounds for legal and financial pain if you don't know what what you are doing, and most people don't. And how are people likely to get access to this information that will protect their legal and personal interests before they buy or sell a home in any case? THE POWER OF THE NAR OVER GOVERNMENT AND MEDIA The things many people don't know is the National Association of Realtors Ò (NAR) is one of America's largest special interest categories who have incredible lobbying power over our politicians to put in writing real estate laws that benefit the real estate industry, not even consumers. Thus, the caveat emptor clause... state as well as federal real estate laws are written in the interests of this local real estate company and not you. Something else people are un-aware of is the tremendous advertising influence the NAR seems to have over print and electronic media to manipulate the news you will read, hear and see because of their advertising dollar power. There may be an article written by Elizabeth Lesley of the Washington Journalism critique called Demand Happy News And Often Get It and it exposes the corruption and manipulation of the news consumers trust in to make decisions about buying or selling a home. I strongly encourage everyone to read this article. Real estate is like the stock market utilizing some ways. When you hear of a fad like "flipping" you may be probably at the tail end of that gimmick bubble, kind of like the dot. com days... everybody jumped in as they quite simply thought it was hot and it was really the end of the us dot. com bubble. A lot of people have gotten caught with their dirt bike pants down on the flipping angle. Home foreclosures are " up " across the U. S. because real estate agents and the lenders what person cater to them (the real estate industry has tremendous determine over the lending industry because the are the source of so many place loans) have qualified otherwise unqualified borrowers, by positioning them in gimmick loans. In the mad dash for you to milk the market, people have been steered in to interest primarily loans, negative amortization loans or attractive teaser borrowing products like low interest adjustable rate mortgage (ARM) and other mindless financing that is NOT in the best interest of the buyer. Consumers many of the foreclosures are happening. Naïve and gullible individuals were sold a bill of goods based on unrealistic place values. The market got hyped and the agents and providers were right there to exploit buyers and sellers. Does some people make money? Sure. But many people have found themselves with wall with too much "house", too big a payment along with a housing market that looks pretty bleak for a while... All you will need is one ripple in our fragile economy to turn the estate market into a landslide. Here's a news flash: Typically the economy is on shaky ground. The economy has long been kept strong by housing sales and corporate profit margins and both are an illusion. The real measure of typically the economy is durable goods, like automotive sales, which you'll find in the tank causing massive restructuring and layoffs. Individuals can't afford to buy cars because they are scraping the enameled off their teeth trying to make house payments... So , whoever you are, and you read my real estate articles, take into account the reason I have done what I have done, and will perform what I do, is because I am on the side of the consumer. Now i'm on the side of the person who wants to be a better, more up to date consumer. I am on the side of the person who wants to save a handful of thousand on their real estate transaction by being smart and about the more level playing field with real estate agents. And you really know what? By educating people and teaching them how to achieve deals more intelligently, how to weed out the piece timer agents from the pros and save a few dollars in the process, I am actually helping the professional full time providers. The truth is that honest agents won't have a problem with my place because it will get rid of the riff raff.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Moore`s Law, Golf, and Your Business Tools

In the past 50 years, golf devices has actually enhanced tremendously. Yet in spite of clubs that struck the sphere farther and straighter, despite the surge of swing instructors, videos, as well as much better training methods, the ordinary rating for a round of golf remains at around 100, where it has actually rested for decades.

Credit: Jeff the Trojan

The average gamer's driver is qualified of hitting the ball 60-70 yards farther today. Irons are much more forgiving, regardless of where effect is made on the clubface. Golf rounds go further without any loss of feeling or spin.

My preferred breakthrough is GPS. From this, you get the precise distance to the opening, and also to the threats. How has it allowed us? Well, it helps some gamers keep in mind which hole they're playing after the draft beer cart has made one a lot of visits.

Some pros do effectively by pressing the equipment guidelines to their restrictions. Unidentified Matt Every started this year with a putter that looked like a black metal train line connection. Transforms out the 'Black Swan' putter has some rather innovative engineering integrated in: the highest possible 'putter momentum of inertia in putter record,' as well as a 'wonderful area 3 balls vast'! Every led the Sony Open entering into the final round, however dropped back a bit, choosing a tie for sixth, and also $178,062.50. A little bit much better compared to my $62.50 in life time golf earnings.

Why, with all the hardware in the bag, do not amateurs' average ratings boost? A few reasons:

Practice and technique imply a great deal more to racking up efficiency compared to equipment.

Commitment and passion feed right into practice as well as technique.

The 10,000 hours rule: You're not getting there playing 10 rounds a year (that would certainly take you 200 years - as well as arthritis postures an actual trouble at this moment.)

Strategy: Top pros 'believe their way around the training course.' Golf provides a collection of challenges with each opening. Not trying to fix them gnaws at your score, bit by bit.

Games often get harder when everyone has access to the exact same improved tools. To make up for the added size of players' drives, training course were extended, and given more 'teeth'.

Feel: You need to turn the club, which means a connection between mind, body, ball, circumstance, and area. Having scientists enhance 'rate as well as power' without readjusting various other variables might make you a worse player overall.

Forgiving clubs keep even more helpless players keep coming out. Such players don't even discover the basics like a right grasp. The typical rating suffers.

Leonardo da Vinci's Traveling Machine

When you hand over a wonder device to the general population, the wide divergence in responses to them is amazing.Casual golf players always made use of to make the excuse that unlike the pros, they really did not have a caddie who carried around a 'yardage book' for every space and cranny on the program. With the advent of GPS, that reason was gone.

So just what does the ordinary gamer do when provided the info that on a 370-yard hole, the water risk begins 230 backyards from the tee, and ends 260 yards from the tee? Pulls out his 'huge stick,' as well as aims to clear the water, or thinks/hopes 'I hardly ever struck that far, so at worst I'll comfy up 227 yards down the fairway'. And ... whack! 252 yards, a beautiful looking shot ... so ... that risk had not been there. Plop! All along, there was a much greater probability of racking up par by beginning with a shot of about 205 lawns, using a 205-yard club (most gamers will certainly score no differently from 95 lawns out as well as 165 backyards out).

In various other words, you provide an amateur a powerful tool, and he does not utilize it for any kind of constant, routed purpose. The gamer spends virtually no strategic initiative in order to take advantage of brand-new information he has at his disposal. The concern to be lookinged there was 'what should be done regarding the hazard'? The response was, by default: nothing. Keep playing the means you always do.

Moore's Legislation as well as the Cloud-Based Blister Economy/Bubble

In every area - perhaps in computer than others - we've seen spectacular increases in raw power as well as performance over the past fifty as well as 10 years. Moore's Regulation (not purely a scientific 'law'), the feverish press for boosts in computing rate (which drove Intel to terrific efficiency over the years), has actually equated into end results as well as financial makeovers that could not have happened without them.

Yet as a society we still encounter numerous obstacles. We do not face bandwidth shortage or material circulation expenses like we did twenty years ago, yet we still deal with several zero-sum video games, including those including precious commodities like water, breathable air, and also yes, also food.

Before the mania for 'computer in the cloud' really started to take off, but long after leaders had actually already assembled low-cost commercial property devices to launch their one-of-a-kind dreams and plans, I was struck to hear Google CEO Eric Schmidt reviewing the impressive company environment we live in today.

The 'expense of introducing a startup' was near zero, went the line. And on paper I understand this to be true.

The Eric Schmidt Perspective

The price of running some sort of technology startups dove - 90 to 98 percent, probably - in between 1996 and also 2006. So you could virtually do anything you set your mind to (presuming you have a computer science degree or more, a one-bedroom house, and a Net link.) This ended up being a preferred line at Google, delivered by other prominent Google keynote speakers. It was as if they and also others in Silicon Valley were component of a liberating army, eliminating expenses from the environment of chance, to enable the very best and also brightest triggers to spark without the burden of debt or massive VC fundraising efforts.

It's only been regarding fours years given that those remarks, but on representation, they plainly painting an extremely partial picture of the reality.

An 'unprecedented great environment for business' became a credit history press, a deep recession, as well as a recognition that much of the larger economic bubble that had actually been sustaining so much risk-taking was maintained by unsustainable financial need and also document degrees of home debt.

So that's something. Rental fee as well as food will certainly still cost you. And also to gain those, you normally need a job, not an amazing startup plan as well as totally free software.

And amusing point: the largest news to come was not concerning all the small start-ups somehow flourishing, but rather, just how a lot more financier cash was starting to pile right into young business to allow them at the seed rounds throughout to A, B, and also C rounds of venture financing as well as beyond. That doesn't count all the large media companies divesting (or just shedding) old assets as well as putting whatever funding they have actually left or can elevate right into a range of digital enterprises.

Web 2.0 Propaganda

Web 2.0 VC 'bubble' cash (after briefly running out in the crunch) fed smoothly into the next phase: a doubling-down into a massive technology IPO blister that compensated the boldest and also biggest players (and their investment bankers). Pandora, Groupon, LinkedIn, Zillow, Angie's Checklist, Zynga, TripAdvisor, (as well as, coming soon, Yelp and Facebook) elevated big amounts of resources in their attempts to go for broke as well as end up being 'classification killers' - high as Amazon.com had done (as it turned out, effectively) all those years ago.

Facebook, Zillow, and also Twitter incorporated raised at one billion bucks prior to going public.

So much for the concept that beginning a business is economical, as well as that practically anybody can do it without the aid of the economic markets. Impressive founders, remarkable teams, impressive capitalists, remarkable network effects with users, amazing media tales, and so on created a 'spiky' globe of brand-new technology giants with large customer followings, not a level, enjoyable world where everybody reached work with their animal projects.

So the availability of low-cost bandwidth, remote teamwork, as well as helpful SaaS devices - also ones that cost 90-98% much less compared to they did a decade ago - gets a lot more individuals to the very first tee currently, yet few struck it all right to be able to quit their day job.

True pioneers and enthusiasts could not be so different from normal people - approximately some commercial property books now tell us. Well, they're absolutely human. And also they're not reckless, always. They're usually enormous outliers in some way. You give them the devices, and also they are in a tiny minority of people who could spark those stimulates into a bonfire of development. [For more on this, see the section on Bill Gates' exceptional success in Jim Collins, Great By Choice: Uncertainty, Turmoil, and also Good luck - Why Some Thrive Regardless of Them All (HarperBusiness, 2011, pp. 162-166) .]

Limitations: Moore's Legislation as well as Economic situations of Scale

Moore's Regulation has actually definitely made a wide range of technical innovations feasible, as well as this has an effect not only on your lifestyle, but on all fields.

But such 'legislations' don't always appear to change our lot of moneys. Some environments aren't even suitable with such laws.

A Fish Out of Water - Credit rating: Julian Burgess

Golf comes with an integrated social and physical atmosphere that dictates a tempering of raw 'power.' We could not have Moore's Legislation in golf clubs - to name a few traits, training courses would ultimately get to the size of our planetary system. A 'club' has to do its trait within specific limitations. Gamers cannot push the round into orbit with rocket launchers. Probably that's just common sense. Then there is decorum to think about.

Moore's Law does not, on its own, make excellent business. Neither do cheaper, quicker tools generally.

If barriers to access on (for example) computing and also storage were lowered to zero, it would certainly could develop an entire new collection of challenges in any industry.

We can't all be cover girls...

Moore's Legislation does not suggest you can come to be Tiger Woods.

Moore's Law can't even exist in social environments that limit pure developments in rate, power, or outcome. Playing 'better,' or a lot more 'positively,' not 'larger, much faster, and also dirtier' is often absolutely the game you're playing ... something that gets lost in breathless media as well as coverage of the 'pure advancements' in things like chip innovation. [For a thoughtful counterpoint to out of breath technology as well as business media, see Umair Haque's sights on value cycles, sustainable sources, as well as the tech industry's propensity for producing 'thin worth'. Umair Haque, The New Capitalist Manifesto: Structure a Disruptively Better Company (Harvard Company Press, 2011) .]

Cloud computer will not turn all garage hackers right into Mark Zuckerberg.

Plus, you wouldn't want it to.

These are devices, ordinary and simple.

The devices are exceptionally powerful in the right-hand men. And also virtually ineffective in the wrong ones.

Making them less expensive, or totally free, does not constantly spur a sudden uptake of thankful users.

Most middle-class family members today can afford gym memberships, Nordic skating skis, and also personal trainers.

All family members can afford running shoes.

And yet the excessive weight epidemic shows no signs of abating.

Why Cost is Good

Where am I goinged with all this? I need to be right here to discuss marketing automation tools, which is mainly the subject of the Acquisio blog site, right?

I'll chat about all of that rather a bit in the coming year. Yet I just needed to obtain that off my chest.

I like that many of these devices are budget friendly to numerous people, that's for sure. I once created a write-up that lauded then-new Google Analytics for 'equalizing' actionable analytics, to put it accessible of the average business.

GA's complimentary power is a terrific instance of today's incredible as well as more level playing area for the smaller sized business, definitely. Nobody would certainly desire this video game to be playable just by a cartel of firms that could manage six figures a year for Internet Analytics, for example.

But some cost is good. Some expense (whether it remains in time, rush, or money) allows the much more passionate and also fully commited amongst us obtain a little a benefit over those that will not invest.

Back to the broad world of sporting activities: in my brief, inauspicious profession in high institution cross-country skiing, those people that lived in warmish environments spent a fair bit of time in the offseason doing exactly what was called 'dryland training': running up as well as down ravines in sweltering temperatures, and also strapping on very early 'roller skis' to pole around on dead-end streets.

Credit: Daniel Malmhall

The investment in odd (as well as somewhat costly) devices settled in performance. And also would not you understand, dryland training becomes an additional spectacular instance of just how approaches that offer you a side in one age come to be simple 'tablestakes' in another.

All expert hockey players, as an example, train throughout the summer season. Being 'in shape' isn't much of an advantage in pro hockey today.

Despite the reality that others will at some point reach your business use of brand-new tools and also methods, maybe that's simply it.

An 'side' is never ever for life. Those that seek an edge are frequently rewarded.

The tools will never literally be your side, but if you locate on your own leveraging their power when others are active with something else, opportunities are your enthusiasm to uncover effective brand-new tools is a sign of your individual commitment to remarkable performance.

How dedicated can you be? To be really fantastic at anything, you need a degree of commitment that is - to place it gently - unbalanced. As the great David Feherty put it: 'If you're great at this video game, there's something seriously incorrect with you. [...] If you have dinner with Vijay Singh and also a pea rolls right into his mashed potatoes, he's got a fork in his hand, however he's checking out a shelter shot.'

#affiliate marketing#business#business plan#digital marketing#internet marketing#marketing#marketing companies#marketing strategy#online marketing

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Dhandho Investor’s Guide to Calculating Intrinsic Value

One of the best books I’ve ever read on investing, and one written in a simple language, is Mohnish Pabrai’s The Dhandho Investor.

Mohnish explains in the introduction –

Dhandho (pronounced dhun-doe) is a Gujarati word. Dhan comes from the Sanskrit root word Dhana meaning wealth. Dhan-dho, literally translated, means “endeavors that create wealth.” The street translation of Dhandho is simply “business.” What is business if not an endeavor to create wealth?

The premise of Dhandho investing is, as is repeated time and time again in the book is simple – Heads, I win; tails, I don’t lose much.

One of my favourite chapters from the book is “Dhandho 102: Invest in Simple Businesses.” Here, Mohnish explains the concept of intrinsic value and also why, for most investors, it pays to identify simple businesses and then buy them at prices that provide sufficient margin of safety.

I would recommend you read this book in its entirety, and especially this chapter for it explains one of the most critical aspects of the investment process i.e., intrinsic value calculation, in its simplest sense. Though I am sure a lot of readers would not like such a simplistic approach to calculating values, for our minds generally don’t accept things that are simple and rather search for things that are complex (which make us look and feel smart). Else, Confucius wouldn’t have said that life is really simple, but we insist on making it complicated.

Anyways, coming back to this chapter from Mohnish’s book, he expands on John Burr Williams’ concept of calculating intrinsic values by discounting future cash flows. He quotes Williams’ concept thus –

Per Williams, the intrinsic value of any business is determined by the cash inflows and outflows—discounted at an appropriate interest rate—that can be expected to occur during the remaining life of the business. The definition is painfully simple.

He then goes on to explain this concept using the example of a gas station –

To illustrate let’s imagine that toward the end of 2006, a neighborhood gas station is put up for sale, and the owner offers it for $500,000. Further, let’s assume that the gas station can be sold for $400,000 after 10 years. Free cash flow—money that can be pulled out of the business—is expected to be $100,000 a year for the next 10 years. Let’s say that we have an alternative low-risk investment that would give us a 10 percent annualized return on the money. Are we better off buying the gas station or taking our virtually assured 10 percent return?

I used a Texas Instruments BA-35 calculator to do these discounted cash flow (DCF) calculations. Alternately, you could use Excel. As Table 7.1 demonstrates, the gas station has an intrinsic value of about $775,000.

We would be buying it for $500,000, so we’d be buying it for roughly two-thirds of its intrinsic value. If we did the DCF analysis on the 10 percent yielding low-risk investment, it looks like Table 7.2.

Not surprisingly, the $500,000 invested in our low-risk alternative has a present value of exactly that—$500,000. Investing in the gas station is a better deal than putting the cash in a 10 percent yielding bond—assuming that the expected cash flows and sale price are all but assured.

The stock market gives us the price at which thousands of businesses can be purchased. We also have the formula to figure out what these businesses are worth. It is simple.

Mohnish then uses this concept to a real-life retail business that is Bed Bath and Beyond (BBBY). Here is how his explanation goes –

As I write this, BBBY has a quoted stock price of $36 per share and a market cap of $10.7 billion. We know BBBY is being offered on sale for $10.7 billion. What is BBBY’s intrinsic value?

BBBY had $505 million in net income for the year ended February 28, 2005. Capital expenditures for the year were $191 million and depreciation was $99 million. The “back of the envelope” net free cash flow was about $408 million. (FCF = Net Income plus Depreciation, which is a non-cash expense minus Capital Expenditure)

It looks like BBBY is growing revenues 15 percent to 20 percent and net income by 25 percent to 30 percent a year. It also looks like it stepped up capital expenditure (capex) spending in 2005. Let’s assume that free cash flow grows by 30 percent a year for the next three years; then grows 15 percent a year for the following three years, and then 10 percent a year thereafter. Further, let’s assume that the business is sold at the end of that year for 10 to 15 times free cash flow plus any excess capital in the business. BBBY has about $850 million in cash in the business presently (see Table 7.3).

So, the intrinsic value of BBBY is about $19 billion, and it can be bought at $10.7 billion. I’d say that’s a pretty good deal, but look at my assumptions—they appear to be pretty aggressive. I’m assuming no hiccups in its execution, no change in consumer behavior, and the ability to grow revenues and cash flows pretty dramatically over the years. What if we made some more conservative assumptions? We can run the numbers with any assumptions. The company has not yet released numbers for the year ended February 28, 2006, but we do have nine months of data (through November 2005). We can compare November 2005 data to November 2004 data. Nine month revenues increased from $3.7 billion to $4.1 billion from November 2004 to November 2005. And earnings increased from $324 million to $375 million. It looks like the top line is growing at only 10 percent annually and the bottom line by about 15 percent to 16 percent. If we assume that the bottom line growth rate declines by 1 percent a year—going from 15 percent to 5 percent and its final sale price is 10 times 2015 free cash flow, the BBBY’s intrinsic value looks like Table 7.4.

Now we end up with an intrinsic value of $9.6 billion. BBBY’s current market cap is $10.7 billion. If we made the investment, we would end up with an annualized return of a little under 10 percent. If we have good low-risk alternatives where we can earn 10 percent, then BBBY does not look like a good investment at all. So what is BBBY’s real intrinsic value? My best guess is that it lies somewhere between $8 to $18 billion. And in these calculations, I’ve assumed no dilution of stock via option grants, which might reduce intrinsic value further.

With a present price tag of around $11 billion and an intrinsic value range of $8 to $18 billion, I’d not be especially enthused about this investment. There isn’t that much upside and a fairly decent chance of delivering under 10 percent a year. For me, it’s an easy pass.

Now, the objective of this exercise, as Mohnish writes in his book is not to figure out whether BBBY is a stock worth investing into at the current valuation of $11 billion. It is to show that even as the method of calculating intrinsic value using the formula given by John Burr Williams and then later talked about by Warren Buffett is simple, calculating it for a given business may not be so.

So, even with a simple business like BBBY that sells bedding, bath towels, kitchen electrics, and cookware, you will end up with a pretty wide range of its intrinsic values.

Those bent on precision in calculating intrinsic values will junk such a process. But those bent on Ben Graham will use this process and then add a margin of safety to cover for any risk that may arise from the intrinsic value calculations (even wide ranges) going haywire.

Anyways, here is an excel sheet I have created using the process explained by Mohnish in his book. It contains not just the process – that I have termed “Dhandho IV” – outlined in the book, but also a reverse process – that I have termed “Reverse Dhandho IV” – where I find the stock market’s free cash flow growth rate assumption embedded in the stock’s current market cap. This is like the Reverse DCF process that I explained in an old post on how to value stocks using DCF.

Before you see the excel, please note that the examples of Infosys and Asian Paints I have used are just for representation purposes and do not suggest my view on these stocks. I have also explained some cells using comments. Please read the same before you start using the excel.

And before I end, here’s my usual disclaimer – It’s good to work on spreadsheets, but please avoid twisting spreadsheets to fit your version of reality. In fact, if you need spreadsheets to tell you whether you should buy or avoid a stock based on the numbers the sheet throws at you, you are doing something wrong in your investment process.

For most of us, searching for simple businesses that don’t require answering difficult questions, and then buying them at valuations that could be performed back of the envelope – or like Mohnish did, on a calculator – is going to be profitable enough. And so will be reading Mohnish’s book – The Dhandho Investor.

The post The Dhandho Investor’s Guide to Calculating Intrinsic Value appeared first on Safal Niveshak.

The Dhandho Investor’s Guide to Calculating Intrinsic Value published first on https://mbploans.tumblr.com/

0 notes

Text

The Dhandho Investor Guide to Calculating Intrinsic Value

One of the best books I’ve ever read on investing, and one written in a simple language, is Mohnish Pabrai’s The Dhandho Investor.

Mohnish explains in the introduction –

Dhandho (pronounced dhun-doe) is a Gujarati word. Dhan comes from the Sanskrit root word Dhana meaning wealth. Dhan-dho, literally translated, means “endeavors that create wealth.” The street translation of Dhandho is simply “business.” What is business if not an endeavor to create wealth?

The premise of Dhandho investing is, as is repeated time and time again in the book is simples – “Heads, I win; tails, I don’t lose much.”

One of my favourite chapters from the book is “Dhandho 102: Invest in Simple Businesses.” Here, Mohnish explains the concept of intrinsic value and also why, for most investors, it pays to identify simple businesses and then buy them at prices that provide sufficient margin of safety.

I would recommend you read this book in its entirety, and especially this chapter for it explains one of the most critical aspects of the investment process i.e., intrinsic value calculation, in its simplest sense. Though I am sure a lot of readers would not like such a simplistic approach to calculating values, for our minds generally don’t accept things that are simple and rather search for things that are complex (which make us look and feel smart). Else, Confucius wouldn’t have said that life is really simple, but we insist on making it complicated.

Anyways, coming back to this chapter from Mohnish’ book, he expands on John Burr Williams’ concept of calculating intrinsic values by discounting future cash flows. He quotes Williams thus –

Per Williams, the intrinsic value of any business is determined by the cash inflows and outflows—discounted at an appropriate interest rate—that can be expected to occur during the remaining life of the business. The definition is painfully simple.

He then goes on to explain this concept using the example of a gas station.

To illustrate let’s imagine that toward the end of 2006, a neighborhood gas station is put up for sale, and the owner offers it for $500,000. Further, let’s assume that the gas station can be sold for $400,000 after 10 years. Free cash flow—money that can be pulled out of the business—is expected to be $100,000 a year for the next 10 years. Let’s say that we have an alternative low-risk investment that would give us a 10 percent annualized return on the money. Are we better off buying the gas station or taking our virtually assured 10 percent return?

I used a Texas Instruments BA-35 calculator to do these discounted cash flow (DCF) calculations. Alternately, you could use Excel. As Table 7.1 demonstrates, the gas station has an intrinsic value of about $775,000.

We would be buying it for $500,000, so we’d be buying it for roughly two-thirds of its intrinsic value. If we did the DCF analysis on the 10 percent yielding low-risk investment, it looks like Table 7.2.

Not surprisingly, the $500,000 invested in our low-risk alternative has a present value of exactly that—$500,000. Investing in the gas station is a better deal than putting the cash in a 10 percent yielding bond—assuming that the expected cash flows and sale price are all but assured.

The stock market gives us the price at which thousands of businesses can be purchased. We also have the formula to figure out what these businesses are worth. It is simple.

Mohnish then uses this concept to a real-life retail business that is Bed Bath and Beyond (BBBY). Here is how his explanation goes –

As I write this, BBBY has a quoted stock price of $36 per share and a market cap of $10.7 billion. We know BBBY is being offered on sale for $10.7 billion. What is BBBY’s intrinsic value?

BBBY had $505 million in net income for the year ended February 28, 2005. Capital expenditures for the year were $191 million and depreciation was $99 million. The “back of the envelope” net free cash flow was about $408 million. (FCF = Net Income plus Depreciation, which is a non-cash expense minus Capital Expenditure)

It looks like BBBY is growing revenues 15 percent to 20 percent and net income by 25 percent to 30 percent a year. It also looks like it stepped up capital expenditure (capex) spending in 2005. Let’s assume that free cash flow grows by 30 percent a year for the next three years; then grows 15 percent a year for the following three years, and then 10 percent a year thereafter. Further, let’s assume that the business is sold at the end of that year for 10 to 15 times free cash flow plus any excess capital in the business. BBBY has about $850 million in cash in the business presently (see Table 7.3).

So, the intrinsic value of BBBY is about $19 billion, and it can be bought at $10.7 billion. I’d say that’s a pretty good deal, but look at my assumptions—they appear to be pretty aggressive. I’m assuming no hiccups in its execution, no change in consumer behavior, and the ability to grow revenues and cash flows pretty dramatically over the years. What if we made some more conservative assumptions? We can run the numbers with any assumptions. The company has not yet released numbers for the year ended February 28, 2006, but we do have nine months of data (through November 2005). We can compare November 2005 data to November 2004 data. Nine month revenues increased from $3.7 billion to $4.1 billion from November 2004 to November 2005. And earnings increased from $324 million to $375 million. It looks like the top line is growing at only 10 percent annually and the bottom line by about 15 percent to 16 percent. If we assume that the bottom line growth rate declines by 1 percent a year—going from 15 percent to 5 percent and its final sale price is 10 times 2015 free cash flow, the BBBY’s intrinsic value looks like Table 7.4.

Now we end up with an intrinsic value of $9.6 billion. BBBY’s current market cap is $10.7 billion. If we made the investment, we would end up with an annualized return of a little under 10 percent. If we have good low-risk alternatives where we can earn 10 percent, then BBBY does not look like a good investment at all. So what is BBBY’s real intrinsic value? My best guess is that it lies somewhere between $8 to $18 billion. And in these calculations, I’ve assumed no dilution of stock via option grants, which might reduce intrinsic value further.

With a present price tag of around $11 billion and an intrinsic value range of $8 to $18 billion, I’d not be especially enthused about this investment. There isn’t that much upside and a fairly decent chance of delivering under 10 percent a year. For me, it’s an easy pass.

Now, the objective of this exercise, as Mohnish writes in his book is not to figure out whether BBBY is a stock worth investing into at the current valuation of $11 billion. It is to show that even as the method of calculating intrinsic value using the formula given by John Burr Williams and then later talked about by Warren Buffett is simple, calculating it for a given business may not be so.

So, even with a simple business like BBBY that sells bedding, bath towels, kitchen electrics, and cookware, you will end up with a pretty wide range of its intrinsic values.

Those bent on precision in calculating intrinsic values will junk such a process. But those bent on Ben Graham will use this process and then add a margin of safety to cover for any risk that may arise from the intrinsic value calculations (even wide ranges) going haywire.

Anyways, here is an excel sheet I have created using the process explained by Mohnish in his book. It contains not just the process – that I have termed “Dhandho IV” – outlined in the book, but also a reverse process – that I have termed “Reverse Dhandho IV” – where I find the stock market’s free cash flow growth rate assumption embedded in the stock’s current market cap. This is like the Reverse DCF process that I explained in an old post on how to value stocks using DCF.

Before you see the excel, please note that the examples of Infosys and Asian Paints I have used are just for representation purposes and do not suggest my view on these stocks. I have also explained some cells using comments. Please read the same before you start using the excel.

And before I end, here’s my usual disclaimer – It’s good to work on spreadsheets, but please avoid twisting spreadsheets to fit your version of reality. In fact, if you need spreadsheets to tell you whether you should buy or avoid a stock based on the numbers the sheet throws at you, you are doing something wrong in your investment process.

For most of us, searching for simple businesses that don’t require answering difficult questions, and then buying them at valuations that could be performed back of the envelope – or like Mohnish did, on a calculator – is going to be profitable enough. And so will be reading Mohnish’s book – The Dhandho Investor.

The post The Dhandho Investor Guide to Calculating Intrinsic Value appeared first on Safal Niveshak.

The Dhandho Investor Guide to Calculating Intrinsic Value published first on http://ift.tt/2ljLF4B

0 notes

Text

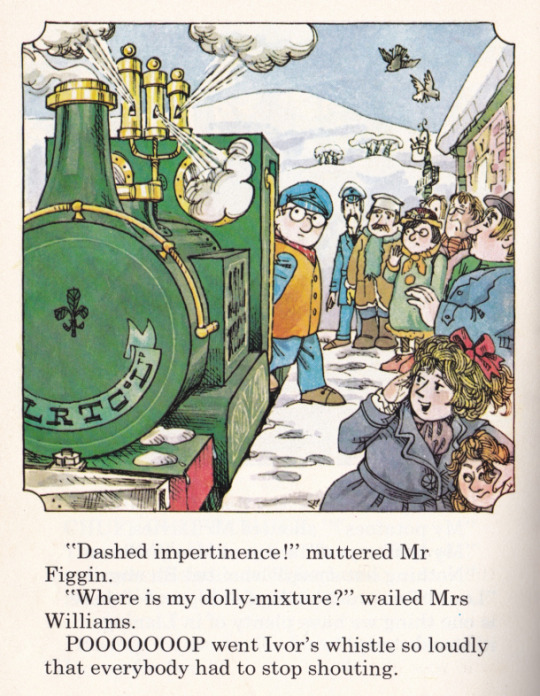

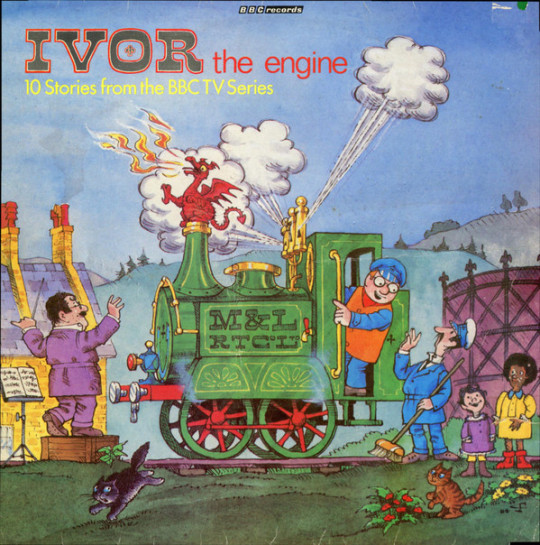

Ivor the Engine

There is a moment in most parents’ lives when their children discover trains. Having been a budding trainspotter myself — and briefly, if less glamorously, a bus-spotter — I’m at a loss to fully explain the magic that things on wheels possess. To be honest, I’m still slightly magicked.

Most magical of all trains is, of course, the steam engine. With its belly of fire and snout of steam (the mechanics of which appear reasonably and appealingly explicable to a young ‘un), it’s the closest most kids will get to coming face-to-face with a mythical beast.

Trains are also all about rules. While cars and trucks are unwieldy and unpredictable, capable of going anywhere, a train (and to a lesser extent, a bus) is confined to a fixed course. I suspect there is a comfort in that.

Signals and junctions and forks and turntables provide kids with a whole language of control. As a six-year-old, I used to plot extravagant courses with marker pen and butcher’s paper and run my Matchbox trains to a strict timetable. Clearly, I had issues.

Thomas the Brown Noser

For Child One, the train obsession really took off when she was two. It sprang from her early love of books. We found a beautiful volume of Thomas The Tank Engine stories in a Chapel Street op shop, which tickled her bibliophilia and my nostalgia bone. While One enjoyed the stories (except the distressing one where Henry was bricked into a tunnel), it didn’t take me long to realise the Thomas stories are pretty seriously unpleasant.

Leaving aside the issues around gender representation (the later books attempt to redress this somewhat, but even then it’s often a female engine a) causing trouble or b) trying to prove she’s almost as good as the boys), there’s a real well of nastiness to Thomas.

The engines are constantly bickering and attempting to “pay each other out”. Their sole purpose to is to become “really useful engines” — rather literal cogs in the machine. The Fat Controller is a cruel headmaster figure, frequently delivering extreme scolding and punishments.

If you went to an English boarding school in the 1950s, it would likely feel grimly familiar. Likewise if you went on to work in a bullying corporate environment. I quite enjoyed a recent theory that argued that the Isle of Sodor is actually set in a dystopian parallel universe.

Ivor the Engine

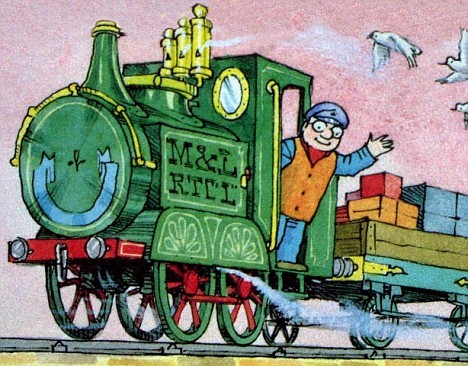

Looking to cater to One’s new obsession with steam, I remembered Ivor The Engine. As a child, I’d had two Ivor books — The Elephant and The Dragon. Written by Oliver Postgate and illustrated by Peter Firmin (the duo behind Bagpuss, Noggin the Nog and Clangers), these lyrical tales are a perfect antidote to Thomas’s brutal world of bureaucracy, backbiting and workaholism.

In one of the stories, Ivor and his driver take the day off to go fishing. When Thomas tries his hand at angling, it nearly kills him and he learns to keep his mind on the job.

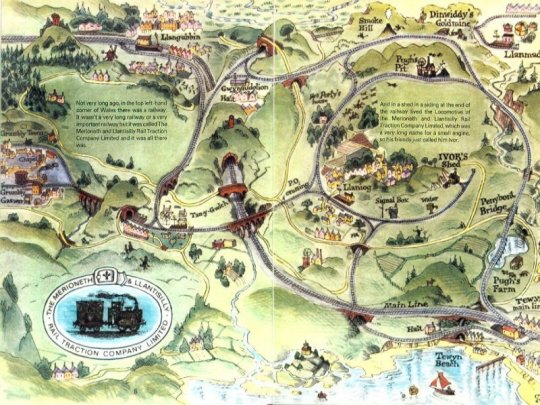

Ivor doesn’t have a face or a voice. He doesn’t even have a name (Ivor is a nickname because “the Locomotive of the Merioneth and Llantisilly Rail Traction Company Limited… was a long name for a little engine”). But through his whistled interactions with driver (and interpreter) Jones the Steam, he is given more depth and humanity than any of Awdry’s trains.

Ivor lives in rail shed attached to a railway in the top left-hand corner of Wales, a branch line that is described as being neither long nor important. When he proves himself useful, it’s as a member of the local community rather than through ruthless efficiency. He helps lure pigeons from a villager’s roof, assists a wounded elephant, saves lost sheep and runs packages to the needy up and down his branch line. When hunters threaten the lives of a local family of foxes, Ivor and Jones effect a clever escape.

While Thomas and “friends” are in constant competition to prove themselves the fastest, prettiest or most efficient worker, Ivor instead takes pleasure from his surroundings, his friends and, well, just being alive. There's mindfulness for you.

POOP POOP POOPETY-POOP went Ivor’s whistle as they rounded the bend above Llaniog. He wasn’t whistling a warning. He wasn’t whistling a signal. He was whistling for the joy of being alive and steaming, for the joy of seeing the cows in the fields and the sheep on the hills and the big wheel of the Pit spinning in the sunshine.

I don’t think it’s a stretch to see a touch of Dylan Thomas’s Under Milkwood to the writing here, which embraces its Welsh setting through a conversational style peppered with colourful turns of phrase. Even if a parent isn’t bold enough to attempt a Welsh accent, these books are a joy to read aloud.

Rail Against The Machine

Bureaucracy is often the enemy here. In the first story, Ivor decides he wants to join the local choir, so Dai the Station has to check if it’s against regulations. (Head office ultimately sign off on it.) In The Dragon (star Idris is “not one of your lumping great fairy-tale dragons… [but] a small trim, heraldic Welsh dragon, glowing red-hot and smiling”), Dai tries to force Ivor’s scaly new friend out of his firebox and into the “proper container for carrying livestock”. Later, Idris is forced to flee from the railway after an “investigation” is launched into his existence.

“NO!” cried Idris. “No! Dragons are mythical! No, I must not be investigated! No! No! No!”

Thankfully, the local community come together to shield Idris from the excoriating gaze of authority.

Most frighteningly, Ivor himself is threatened when the owners of his railway decide to sell off to a national company that plans to replace him with a diesel. (Not quite as frightening as when Thomas’s cronies are threatened with the scrapyard.) His salvation comes not by proving himself a vital asset to the functioning of the marketplace, but rather as repayment for his past kindnesses.

There is a joy and a magic to these tales that doesn’t undermine the background texture of social realism — the mines, the gasworks, the fish and chip shop. Thomas might depict society as it often is, but Postgate and Firmin offer a glimpse of community as it should be. People who delight in their interactions, who tolerate eccentricity and who find pleasure in their work but are not crushed by the weight of material aspirations.

Compassion and Contentment

The real star, Ivor aside, is Jones the Steam. He is a man in his element, happy in himself and his work and seemingly wanting nothing more. He doesn’t aspire to be a station master or to run his own railway. Although he enjoys performing his errands, Jones’s greatest pleasure is making his morning cup of tea from Ivor’s boiler.

He is compassionate and sensitive, always keen to help, and blind to his own quirks. It’s left to us to decide whether Ivor has an intelligence (I think he does) or whether Jones merely ascribes one to him. Other characters rib him for talking to Ivor, but affectionately so. There is no cruelty here. Only once do we see Jones lose his temper, when dealing with a truculent elephant.

I first encountered these stories as books, without realising they were sprung from a television series that originally screened in the 1950s and 1960s. (The books are far from the usual afterthought cash in, each story lovingly rewritten and reillustrated by the original team.)

The colour episodes are available on DVD and were some of the first television we showed to Child One. There is an enchanting simplicity to the cut-out animation and a leisurely pace to the storytelling that makes them feel very much like a picture book brought to gentle life.

Postgate does most of the voices himself. He is a perennially comforting, sedate presence. As Charlie Brooker once wrote: “there is no more calming sound in the world than the voice of Oliver Postgate. With him narrating your life, you'd feel cosy and safe even during a gas explosion. It floated above all these stories, that voice; wound its way through them.”

The episodes are also available (in pretty terrible quality) on YouTube and, thanks to Postgate’s tender narration, make for delightful audiobooks if you leave the screen off. By a stroke of luck, I recently found a copy of ten of the stories on vinyl.

BOOKS

The Ivor books are all out of print, but readily available via eBay or Abe’s Books.

Ivor The Engine Storybook (published 1982). This is the perfect starter, containing four tales. The First Story, Snowdrifts, The Elephant and The Dragon. Hardbound. Each story takes about 10 minutes to read.

The First Story

Snowdrifts

The Elephant

The Dragon

Ivor’s Birthday

The Foxes

All released in hardback in the early 1990s.

DVD

The Complete Ivor The Engine (Universal Pictures, 2006, 186 minutes)

All the colour episodes of the classic Sixties and Seventies children's series. Enjoy once again the adventures of Welsh steam engine Ivor, Jones the Steam and the good people at the Merioneth and Llantisilly Rail Traction Company - not to mention the dragon and his chestnut barrow!

AUDIO

Ivor The Engine And Pogles Wood by Vernon Elliott

Not sure how much the kids will enjoy this, but it’s pretty delightful. Woodwind and brass score, which (like the sound effects from the TV show) has the benefit of being easily imitated by non-musical parents

MERCHANDISE

Not a lot. There’s a board game I haven’t played, some resin models of Ivor and — perhaps most tempting — a plush Idris the Dragon (not baby safe). Etsy has a few handmade treasures.

THE SHORT STUFF

Age and stage: 2+

Gender stuff: not great. There's a female vet, female shopkeepers and a batty old woman or two, but that's about it. I tend to read the dragon as female, but he's described as being male.

Drama: minimal, with few moments of tension. When younger, Child One was only distressed by the fox hunting sequence in The Foxes (spoiler: the fox lives).

Outdated bits: leaving aside the old school tech and above-mentioned gender issues, it's hard not to feel uneasy about the stereotyped Indian elephant keeper. There's otherwise a distinct lack of diversity.

Themes: community, individuality, compassion, anti-bureaucracy, mindfulness, tolerance, contentment, mythology, the wonder of steam.

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Dhandho Investor’s Guide to Calculating Intrinsic Value

One of the best books I’ve ever read on investing, and one written in a simple language, is Mohnish Pabrai’s The Dhandho Investor.

Mohnish explains in the introduction –

Dhandho (pronounced dhun-doe) is a Gujarati word. Dhan comes from the Sanskrit root word Dhana meaning wealth. Dhan-dho, literally translated, means “endeavors that create wealth.” The street translation of Dhandho is simply “business.” What is business if not an endeavor to create wealth?

The premise of Dhandho investing is, as is repeated time and time again in the book is simple – Heads, I win; tails, I don’t lose much.

One of my favourite chapters from the book is “Dhandho 102: Invest in Simple Businesses.” Here, Mohnish explains the concept of intrinsic value and also why, for most investors, it pays to identify simple businesses and then buy them at prices that provide sufficient margin of safety.

I would recommend you read this book in its entirety, and especially this chapter for it explains one of the most critical aspects of the investment process i.e., intrinsic value calculation, in its simplest sense. Though I am sure a lot of readers would not like such a simplistic approach to calculating values, for our minds generally don’t accept things that are simple and rather search for things that are complex (which make us look and feel smart). Else, Confucius wouldn’t have said that life is really simple, but we insist on making it complicated.

Anyways, coming back to this chapter from Mohnish’s book, he expands on John Burr Williams’ concept of calculating intrinsic values by discounting future cash flows. He quotes Williams’ concept thus –

Per Williams, the intrinsic value of any business is determined by the cash inflows and outflows—discounted at an appropriate interest rate—that can be expected to occur during the remaining life of the business. The definition is painfully simple.

He then goes on to explain this concept using the example of a gas station –

To illustrate let’s imagine that toward the end of 2006, a neighborhood gas station is put up for sale, and the owner offers it for $500,000. Further, let’s assume that the gas station can be sold for $400,000 after 10 years. Free cash flow—money that can be pulled out of the business—is expected to be $100,000 a year for the next 10 years. Let’s say that we have an alternative low-risk investment that would give us a 10 percent annualized return on the money. Are we better off buying the gas station or taking our virtually assured 10 percent return?

I used a Texas Instruments BA-35 calculator to do these discounted cash flow (DCF) calculations. Alternately, you could use Excel. As Table 7.1 demonstrates, the gas station has an intrinsic value of about $775,000.

We would be buying it for $500,000, so we’d be buying it for roughly two-thirds of its intrinsic value. If we did the DCF analysis on the 10 percent yielding low-risk investment, it looks like Table 7.2.

Not surprisingly, the $500,000 invested in our low-risk alternative has a present value of exactly that—$500,000. Investing in the gas station is a better deal than putting the cash in a 10 percent yielding bond—assuming that the expected cash flows and sale price are all but assured.

The stock market gives us the price at which thousands of businesses can be purchased. We also have the formula to figure out what these businesses are worth. It is simple.

Mohnish then uses this concept to a real-life retail business that is Bed Bath and Beyond (BBBY). Here is how his explanation goes –

As I write this, BBBY has a quoted stock price of $36 per share and a market cap of $10.7 billion. We know BBBY is being offered on sale for $10.7 billion. What is BBBY’s intrinsic value?

BBBY had $505 million in net income for the year ended February 28, 2005. Capital expenditures for the year were $191 million and depreciation was $99 million. The “back of the envelope” net free cash flow was about $408 million. (FCF = Net Income plus Depreciation, which is a non-cash expense minus Capital Expenditure)

It looks like BBBY is growing revenues 15 percent to 20 percent and net income by 25 percent to 30 percent a year. It also looks like it stepped up capital expenditure (capex) spending in 2005. Let’s assume that free cash flow grows by 30 percent a year for the next three years; then grows 15 percent a year for the following three years, and then 10 percent a year thereafter. Further, let’s assume that the business is sold at the end of that year for 10 to 15 times free cash flow plus any excess capital in the business. BBBY has about $850 million in cash in the business presently (see Table 7.3).

So, the intrinsic value of BBBY is about $19 billion, and it can be bought at $10.7 billion. I’d say that’s a pretty good deal, but look at my assumptions—they appear to be pretty aggressive. I’m assuming no hiccups in its execution, no change in consumer behavior, and the ability to grow revenues and cash flows pretty dramatically over the years. What if we made some more conservative assumptions? We can run the numbers with any assumptions. The company has not yet released numbers for the year ended February 28, 2006, but we do have nine months of data (through November 2005). We can compare November 2005 data to November 2004 data. Nine month revenues increased from $3.7 billion to $4.1 billion from November 2004 to November 2005. And earnings increased from $324 million to $375 million. It looks like the top line is growing at only 10 percent annually and the bottom line by about 15 percent to 16 percent. If we assume that the bottom line growth rate declines by 1 percent a year—going from 15 percent to 5 percent and its final sale price is 10 times 2015 free cash flow, the BBBY’s intrinsic value looks like Table 7.4.

Now we end up with an intrinsic value of $9.6 billion. BBBY’s current market cap is $10.7 billion. If we made the investment, we would end up with an annualized return of a little under 10 percent. If we have good low-risk alternatives where we can earn 10 percent, then BBBY does not look like a good investment at all. So what is BBBY’s real intrinsic value? My best guess is that it lies somewhere between $8 to $18 billion. And in these calculations, I’ve assumed no dilution of stock via option grants, which might reduce intrinsic value further.

With a present price tag of around $11 billion and an intrinsic value range of $8 to $18 billion, I’d not be especially enthused about this investment. There isn’t that much upside and a fairly decent chance of delivering under 10 percent a year. For me, it’s an easy pass.

Now, the objective of this exercise, as Mohnish writes in his book is not to figure out whether BBBY is a stock worth investing into at the current valuation of $11 billion. It is to show that even as the method of calculating intrinsic value using the formula given by John Burr Williams and then later talked about by Warren Buffett is simple, calculating it for a given business may not be so.

So, even with a simple business like BBBY that sells bedding, bath towels, kitchen electrics, and cookware, you will end up with a pretty wide range of its intrinsic values.

Those bent on precision in calculating intrinsic values will junk such a process. But those bent on Ben Graham will use this process and then add a margin of safety to cover for any risk that may arise from the intrinsic value calculations (even wide ranges) going haywire.