#the economy is meant to serve society

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

also: holy shit- you guys still have Woolworths?!?! they alll closed up in Canada back in the 90s. We have ZERO competition any more.

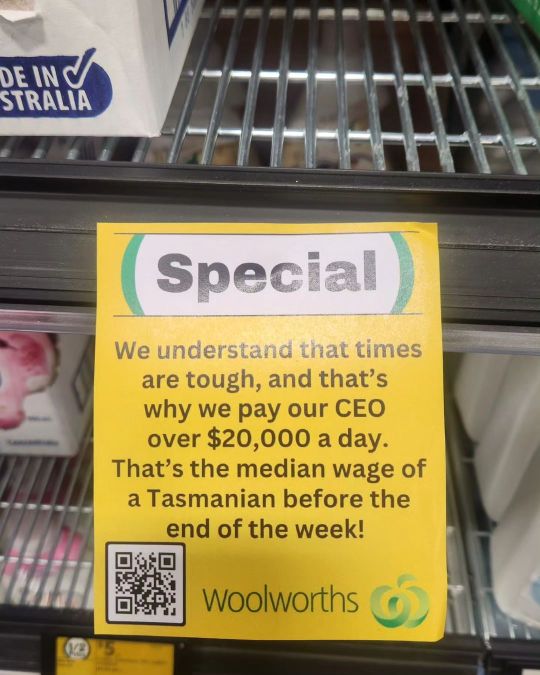

Activists in Tasmania have stuck up more honest promo stickers inside Coles & Woolworths stores, the two dominant supermarket chains in Australia.

#artificial inflation#greedism#the economy is meant to serve society#the economy doesn't have rights#capitalism is killing us#how will you resist?#food is a human right#food security#current events

122K notes

·

View notes

Note

Damian being a gen alpha implies in gen alpha Jon too ...

[at a sleepover]

Damian, whispering: Jon?

Jon: Yeah?

Damian: Our planet is doomed.

Jon: Yeah, it is.

Jon: Wanna sneak downstairs for snacks?

Damian: Sure.

———————

Steph, as a Batburger cashier: Sorry ma'am, that product was discontinued months ago.

Jon: *secretly starts recording*

Margie: You didn't even bother to check! What kind of lazy service is this? No wonder the world is the way it is with your generation. I should call the corporate hotline right now and report you for refusing to serve a paying customer. See how you like it when you lose your job.

Damian: Hey Karen, she said they don't have it anymore. Either get something else or leave. Some of us have places to be.

Margie: And who do you think you are?

Damian, pointing to Jon's camera: The best friend of someone with 150,000 followers.

Jon: Say hi to the internet!

———————

Damian and Jon: *putting up hand-drawn posters around town*

Comm. Gordon: What are you kids doing?

Damian: Advertising our joint channel.

Jon: We're gonna have an epic Cheese Viking and Fortnite mashup tournament.

Damian: Proceeds go to the Wayne Foundation.

Comm. Gordon: *scribbles a note and hands it to them*

Comm. Gordon: If anyone asks you for a permit, it's on me.

———————

Damian and Jon: *huddled around the Batcomputer*

Jon: I think we should sort it by distance instead.

Damian, typing code: Good idea.

Barbara: What's that?

Jon: Our new website.

Damian: It allows people to report stray animals they see without the risk that comes with physical contact.

Barbara: Oh, cool. Carry on.

———————

Kara: What do you want to drink?

Jon: Mountain Dew. Dami, you want one?

Damian: Depends. Is it vegan?

Kara: *starts typing into Google*

Jon: Hey Alexa, is Mountain Dew vegan?

———————

[texting]

Jon: Dami, get on Discord.

Damian: Why?

Jon: Live-action One Piece streaming in the Gay Minecraft server.

———————

Jon: Ms. Kyle, check it out!

Selina: What is it?

Damian: TikTok added a set of Catwoman stickers.

Selina: Show me.

———————

Kate: I still think you are far too young for things like Instagram.

Damian and Jon: *snicker*

Kate: What?

Jon: Well, Ms. Kane, how should we put it...

Damian: No one uses Instagram anymore.

———————

Jon: *takes a 0.5 of him and Damian with Dick in the background*

Damian: You're in our BeReal now. Deal with it.

Dick: What's a BeReal?

———————

Damian, handing Jon a rock: I would like to buy this playhouse.

Jon: Too bad, the economy just disappeared.

Lois: What are you doing?

Jon: We're playing Society.

———————

Damian: Alfred, we're hungry.

Alfred, on the phone: *makes the thumb and pinky gesture and mouths "I'm busy"*

Jon: Huh?

Alfred: I'm on the phone, boys.

Damian: I think he meant this.

Damian: *puts his palm to his ear*

———————

Jon: Parkour!

Jon: *hops over a log*

Jon: Parkour!

Jon: *climbs a tree*

Damian: *recording*

Clark, to Bruce: That's one way to play.

Bruce: Mhm.

Clark: Do you ever get worried about, you know, how these kids are turning out?

Jon: Parkou—

Damian: Wait, stop, there's a bird's egg here. I wonder what species it is.

Jon: I have an app that can scan it.

Bruce, to Clark: I think they're gonna be alright.

#damian wayne#robin#jon kent#superboy#super sons#bruce wayne#batman#clark kent#superman#alfred pennyworth#lois lane#dick grayson#kate kane#selina kyle#kara danvers#james gordon#barbara gordon#stephanie brown#superfamily#batfamily#batfam#batboys#batbros#batkids#batsiblings#batman family#incorrect batfamily quotes#incorrect quotes#incorrect dc quotes#dc comics

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

The full Bennet Family Finances endnote from Ch33

I’ve been doing some more maths (ch26 has the initial discussion) on the savings that our characters might do/should’ve done since it’s fascinating to me and some of the comments I’ve been getting have been making me think more about it. One of the common themes is surprise at just how negligent the Bennets were at saving, instead of merely being stretched thin by expenses. I understand this completely, as it isn’t something that’s explicit in an easily recognisable way for modern audiences.

So, where could they have been more economical? They don’t go to London, no one has a gambling addiction, all travelling (which was EXPENSIVE) is done cost effectively, and they certainly didn’t spend all the money on tutors and the like for their daughters. I’m sure there’s actual academic papers by historians on this (I miss my uni access to those so much) but I can take some educated guesses.

We know Mrs Bennet is just bad with household management. Part of which might mean ordering too much food (it’s mentioned she keeps a good table, so this is as close to canon as we can get) and perhaps not being efficient with what she does order, ie wanting different meats from night to night, instead of having the leftovers served as stews or whatnot, not keeping an eye on the prices of sugar, salt, etc to buy when they’re cheap, making special orders instead of purchasing what’s readily available, etc. We know none of the Bennet women assist in the kitchen (as the Lucases do) so that’s more work for servants and thus likely to contribute to the need of an extra servant or higher wages. Household management could also be more innocuous things like always buying the expensive bees-wax candles, instead of using tallow when guests aren’t around or in out-of-the-way rooms. And being inefficient with candle usage (this is likely a Mr Bennet flaw too, if he enjoys reading in his library at night) in order to have a room better lit than strictly necessary. There was a reason families all tended to gather in one room after dark, and the Bennets notably don’t. Also having fires in all the principal rooms instead of just the ones likely to be used that day. If there’s ways to be inefficient with funds when it comes to cleaning, I’m sure they found a way there, too. Basically, anything that requires forward planning to help with economy would be lacking.

But that’s all ‘essentials’ just done inefficiently, what luxuries might they have had? They have the income to warrant their carriage, horses, and it seems Mr Bennet does hunt, but that’s also a standard expense for his wealth, so let’s focus on what might be pushing them to their limits. Other than the over-provisioned dining table, which we’ve mentioned, nothing about their socialising habits seems excessive. Mrs Bennet’s love of fashion could be pushing her wardrobe bill up, Mr Bennet’s love of books could be a VERY expensive hobby, and of course – five daughters out at once. Having five daughters out (especially unnecessarily as Lydia and even Kitty were quite young to be out) cost a LOT of money. Lady Catherine was rude as anything, but her surprise at the fact was warranted. Other than money, it also meant the daughters were in direct ‘competition’ for the same limited amount of suitors, which theoretically might hurt the elder girls’ chances. Five distinct wardrobes for young women which needed gowns for all occasions, going through dance shoes and gloves very quickly, bonnets, etc, all added up. At the start of the book multiple hundreds of pounds a year would be going to keeping their daughters looking the part while mixing in society.

But Jane’s only twenty-one or twenty-two at the start of the novel, and came out at fifteen at the earliest. Yet the Bennets still never saved money, and never overspent their income, so there were other expenses they were able to drop which had been preventing them from saving money for the first sixteen or so years of their marriage. I think it’s fair to assume there’s random, one-time bigger expenses that were undertaken with any substantial spare money: perhaps the hermitage Mrs Bennet mentions is a newer addition, was the coach (which are normally ordered around the start of a marriage) refitted more recently, how often is the décor of Longbourn updated (and on that note, are things like the sofa reupholstered or completely replaced), do they impulse buy vases and sculptures, make sure whatever alcohol they do buy (which appears to be a reasonable amount for their class) is the expensive stuff, etc. Whatever it is, it’s a both parent problem. Mrs Bennet is bad at money management and instead of changing her habits or preparing her daughters for financial hardship puts pressure on them to marry (preferably rich, but she doesn’t seem to have a complaint about Wickham in that regard). Mr Bennet is smart enough to see that there is a problem and how to fix it, but after his first idea fails (have a son to break the entail and thus provide for his widow and other children – which doesn’t even necessarily mean the girls would get a dowry, just that they would never live in poverty) does nothing to reassess the issue or find a solution. He essentially shrugs his shoulders and lets his daughters shift for themselves. One parent is too stressed about money and only addresses it negatively, and the other isn’t stressed enough and doesn’t address it seriously at all. Neither do anything productive, even though changing their habits would be enough to fix it. I love them, but MASSIVE parenting failure on their end; and hinted to occur because the parents were too used to comforts and different themselves to be able to work together and act on a solution.

Now for some actual MATHS! Which, yes, I realise I am strangely excited about.

The idea that most of the Bennets’ money is spent by having so many daughters out at once seems to keep popping up in my time on the internet. So, I thought it would be interesting to see what their dowries could be if that five-daughters-out-at-once money wasn’t spent on other things before any daughters were out. Costs of this could vary a bit between families, and though we know Lydia’s expenses were almost £100 per annum that includes board and food as well as little gifts from Mrs Bennet, so we can’t simply multiply that by five and be done with it. But, given Mrs Bennet’s desire for fashion and the poor financial management we see from her and some of her daughters, it’s quite possible clothes were being bought new rather than pulled apart and remade more than they ought to be, so spending £50 to £60 a year on each daughter being ‘out’ seems reasonable. For the purposes of this, let’s look at a total of £250 and £300 a year for all five, and in the 4%s because that’s where the money settled on Mrs Bennet apparently is. After sixteen years of marriage (when we will assume Jane comes out) that’s £5,456 or £6,547. Meaning that just doubled their dowry, even if they save nothing else after that. If the interest is left alone, that’s more than £1,000 that’s added to it before the novel even begins. Suddenly Mr Bennet dying at the start of the novel would leave his widow and daughters with between £11,500-£13,000 instead of the meagre £5,000 they actually have.

And the girls didn’t all come out at once, so just to put some numbers to it for math purposes, let’s say Elizabeth came out one year after Jane, Mary two years after her, Kitty another two years later, and Lydia the following year. For simplicity, each girl coming out is going to remove the same amount of money (when realistically it’s likely Jane, who needs everything new, and Lydia, who’s spoilt, would have cost the most). With the lower estimates of expenses, that’s £8,062 saved at the time of the novel, taking the total for Mrs Bennet and the girls to £13,602 or £2,612 each, assuming nothing else is saved. At the higher cost for the girls being out, that’s £9,676 saved and £14,676 that they’ll eventually inherit a share of. Still below what they should have as dowries, but a vast improvement, and proof of why having five daughters out at once was an additional strain but not THE strain. It was just another element in a mountain of problems.

“But what if it was in the 5%s?” asks no one but me. I think they would stick to the more stable bonds Mrs Bennet’s dowry is in, but if they didn’t, the same situation as above would save £9,243 (or £14,243 total) or £11,090 (£16,090 to share or £3,218 each).

For pure funsies, the numbers if Mr and Mrs Bennet had also saved the interest of the £5,000 settled upon her (which by itself would grow to £12,324 in the 4%s) in addition to these savings are:

£20,387 (£4,077 each at the start of the novel) with the £250 expenses estimate. At £300 for all five daughters out, we get to £21,998. Both of these numbers suddenly mean the Miss Bennets would never have to fear poverty when Mr Bennet died and they would individually each be as rich as their mother was, and though they wouldn’t be counted as rich themselves, would at least have something respectable. They might not cost their husbands money to marry.

AND THEN if everything is in the 5%s but that original £5,000, and the interest it gains is also moved to the higher interest account, the grand total would be either £22,528, again assuming the £250 expenses, and £24,376 at the £300 estimate.

I’ve been doing some equations for Darcy, too. So, let’s talk about that next chapter, to give me time to really figure it out.

154 notes

·

View notes

Text

At the end of the day the average civilian wishes to be catered to like an old money steel baron or perhaps one of those chaps from Downton Abbey. The entirety of modern society has come together to enable this, mass-producing cheap facsimiles of fortunes that should rightly either be built on child labor or perhaps serfdom.

Their lawns, taking up what could otherwise be used to grow crops or serve as "outdoor garage space," exist to ape the wide ranging estates meant for the nobility to chase down a fox while adorned in silly jackets. Their houses sport columns and stupid windows meant to imitate three different classical artforms at the same time because of something called "economies of scale." They even have male-centric social clubs meant for parlour games, discussing sports, and dining with friends, in this case franchised out under such names as "Buffalo Wild Wings."

This aping of the upper class continues to the hire of "artisans" to do relatively simple work deemed too complicated to warrant the time of the average citizen. It's not that the jobs are too taxing for your average person, but rather that the market has crystallized around the desire to live like budget royalty. Therefore they take their wafer-thin computers to artisans (now more commonly called "experts" or "Apple geniuses") for repair and have democratized the position of carriagemen to 22 year old dealership lube techs named Ryan who will turn a 15 minute job into a 30 minute endeavor thanks to frequent vape breaks and a brief brush with what the industry refers to as "a misplaced drain bolt."

The mid-40s project manager and mother of 3 is no less competent when changing oil than her grandfather before her who knew what "Valve Lash" is, but what separates the two is a series of wars in the 1900s that required an entire generation of men to become very familiar with operating and repairing machines better than the Germans and Japanese (an exercise that Chrysler would later abandon in favor of the phrase "if you can't beat em, join em").

This conflict ended with a surge of able-bodied men finding themselves returning to their project management jobs (like their granddaughters after them) but armed with captured German weapons and a comprehensive understanding of tubochargers. Just as a line can be drawn from troop drawdowns to political violence, there's a distinct correlations between GIs returning home and the violence with which Ford Flathead V8s were torn apart by inventive supercharging methods paired with landspeed record attempts.

Give a man a racecar and he'll crash it on the salt flats in a day. Teach a man to repair a racecar and it will sit in the garage of his suburban house for a few years in between complete engine rebuilds required by what can only be described as "vaporized piston rods."

Of course this hotrodder generation created the circumstances we live in today, as the market saw their fast cars cobbled together from old prewar hulks and simply stamped out new ones from factory, faster and more convenient for the next generation than building one from scratch. Now the project manager mother of 3 drives a 4wd barge with climate controlled seats boasting more computing power than the moon mission and an emissions-controlled powertrain with more horsepower than her grandfather's jalopy and her fathers factory muscle car combined. And she doesn't care at all.

Yet Amongst the average civilians there walks a rare breed: people who know how to change their own oil. We the chosen move among you silently, bucking the system, operating outside the cultural helplessness and trading in forbidden knowledge in almost-abandoned forum threads (flame wars over conventional vs synthetic).

While we do have a marked air of superiority about this, I can't say I haven't stooped to imitating the rich myself. I've been known to wear a silly jacket from time to time.

237 notes

·

View notes

Photo

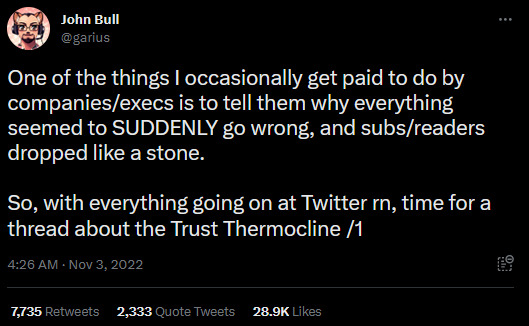

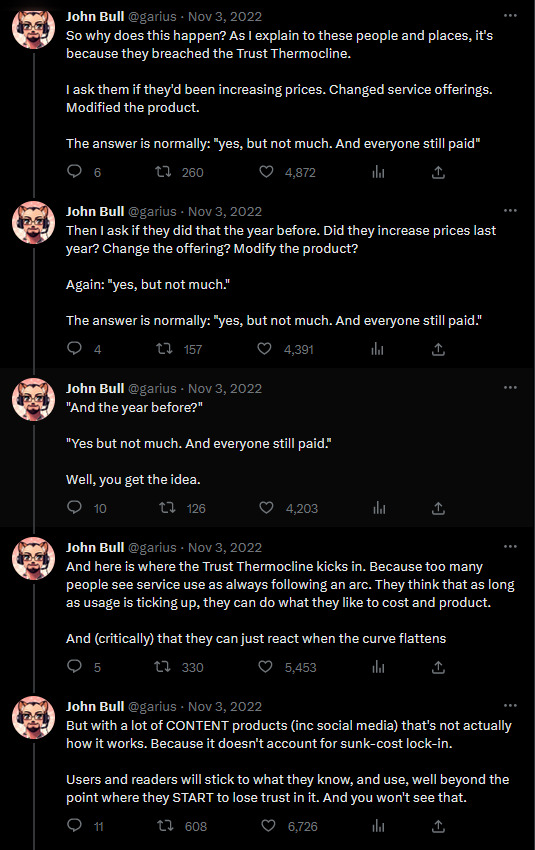

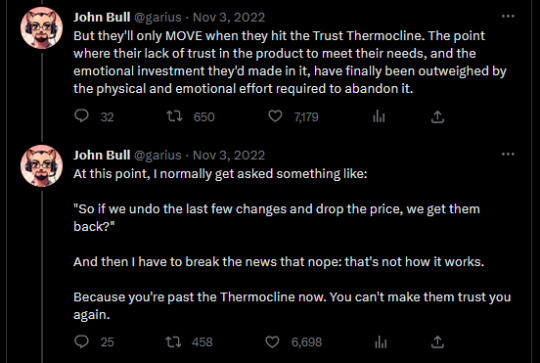

infinite growth is unsustainable. corporate CEOs have no idea what they're doing. (no really.)

the FIRST time someone inconveniences you, is rude, or selfish, you'll likely shrug and give them another chance.

the SECOND time- you take note. and start looking for the exit.

Really good Twitter thread originally about Elon Musk and Twitter, but also applies to Netflix and a lot of other corporations.

Full thread. Text transcription under cut.

Keep reading

#peak capitalism#greedism#it's the capitalists#executives are incompetent.#Business#Capitalism#social engineering#Trust#growth is not linear#limitless growth is a lie#the economy is meant to serve society

62K notes

·

View notes

Text

F.8.1 What social forces lay behind the rise of capitalism?

Capitalist society is a relatively recent development. For Marx, while markets have existed for millennium “the capitalist era dates from the sixteenth century.” [Capital, vol. 1, p. 876] As Murray Bookchin pointed out, for a “long era, perhaps spanning more than five centuries,” capitalism “coexisted with feudal and simple commodity relationships” in Europe. He argues that this period “simply cannot be treated as ‘transitional’ without reading back the present into the past.” [From Urbanisation to Cities, p. 179] In other words, capitalism was not a inevitable outcome of “history” or social evolution.

Bookchin went on to note that capitalism existed “with growing significance in the mixed economy of the West from the fourteenth century up to the seventeenth” but that it “literally exploded into being in Europe, particularly England, during the eighteenth and especially nineteenth centuries.” [Op. Cit., p. 181] The question arises, what lay behind this “growing significance”? Did capitalism “explode” due to its inherently more efficient nature or where there other, non-economic, forces at work? As we will show, it was most definitely the second — capitalism was born not from economic forces but from the political actions of the social elites which its usury enriched. Unlike artisan (simple commodity) production, wage labour generates inequalities and wealth for the few and so will be selected, protected and encouraged by those who control the state in their own economic and social interests.

The development of capitalism in Europe was favoured by two social elites, the rising capitalist class within the degenerating medieval cities and the absolutist state. The medieval city was “thoroughly changed by the gradual increase in the power of commercial capital, due primarily to foreign trade … By this the inner unity of the commune was loosened, giving place to a growing caste system and leading necessarily to a progressive inequality of social interests. The privileged minorities pressed ever more definitely towards a centralisation of the political forces of the community… Mercantilism in the perishing city republics led logically to a demand for larger economic units [i.e. to nationalise the market]; and by this the desire for stronger political forms was greatly strengthened … Thus the city gradually became a small state, paving the way for the coming national state.” [Rudolf Rocker, Nationalism and Culture, p. 94] Kropotkin stressed that in this destruction of communal self-organisation the state not only served the interests of the rising capitalist class but also its own. Just as the landlord and capitalist seeks a workforce and labour market made up of atomised and isolated individuals, so does the state seek to eliminate all potential rivals to its power and so opposes “all coalitions and all private societies, whatever their aim.” [The State: It’s Historic role, p. 53]

The rising economic power of the proto-capitalists conflicted with that of the feudal lords, which meant that the former required help to consolidate their position. That aid came in the form of the monarchical state which, in turn, needed support against the feudal lords. With the force of absolutism behind it, capital could start the process of increasing its power and influence by expanding the “market” through state action. This use of state coercion was required because, as Bookchin noted, ”[i]n every pre-capitalist society, countervailing forces … existed to restrict the market economy. No less significantly, many pre-capitalist societies raised what they thought were insuperable obstacles to the penetration of the State into social life.” He noted the “power of village communities to resist the invasion of trade and despotic political forms into society’s abiding communal substrate.” State violence was required to break this resistance and, unsurprisingly the “one class to benefit most from the rising nation-state was the European bourgeoisie … This structure . .. provided the basis for the next great system of labour mobilisation: the factory.” [The Ecology of Freedom, pp. 207–8 and p. 336] The absolutist state, noted Rocker, “was dependent upon the help of these new economic forces, and vice versa and so it “at first furthered the plans of commercial capital” as its coffers were filled by the expansion of commerce. Its armies and fleets “contributed to the expansion of industrial production because they demanded a number of things for whose large-scale production the shops of small tradesmen were no longer adapted. Thus gradually arose the so-called manufactures, the forerunners of the later large industries.” [Op. Cit., pp. 117–8] As such, it is impossible to underestimate the role of state power in creating the preconditions for both agricultural and industrial capitalism.

Some of the most important state actions from the standpoint of early industry were the so-called Enclosure Acts, by which the “commons” — the free farmland shared communally by the peasants in most rural villages — was “enclosed” or incorporated into the estates of various landlords as private property (see section F.8.3). This ensured a pool of landless workers who had no option but to sell their labour to landlords and capitalists. Indeed, the widespread independence caused by the possession of the majority of households of land caused the rising class of capitalists to complain, as one put it, “that men who should work as wage-labourers cling to the soil, and in the naughtiness of their hearts prefer independence as squatters to employment by a master.” [quoted by Allan Engler, The Apostles of Greed, p. 12] Once in service to a master, the state was always on hand to repress any signs of “naughtiness” and “independence” (such as strikes, riots, unions and the like). For example, Seventeenth century France saw a “number of decrees … which forbade workers to change their employment or which prohibited assemblies of workers or strikes on pain of corporal punishment or even death. (Even the Theological Faculty of the University of Paris saw fit to pronounce solemnly against the sin of workers’ organisation).” [Maurice Dobb, Studies in Capitalism Development, p. 160]

In addition, other forms of state aid ensured that capitalist firms got a head start, so ensuring their dominance over other forms of work (such as co-operatives). A major way of creating a pool of resources that could be used for investment was the use of mercantilist policies which used protectionist measures to enrich capitalists and landlords at the expense of consumers and their workers. For example, one of most common complaints of early capitalists was that workers could not turn up to work regularly. Once they had worked a few days, they disappeared as they had earned enough money to live on. With higher prices for food, caused by protectionist measures, workers had to work longer and harder and so became accustomed to factory labour. In addition, mercantilism allowed native industry to develop by barring foreign competition and so allowed industrialists to reap excess profits which they could then use to increase their investments. In the words of Marxist economic historian Maurice Dobb:

“In short, the Mercantile System was a system of State-regulated exploitation through trade which played a highly important rule in the adolescence of capitalist industry: it was essentially the economic policy of an age of primitive accumulation.” [Op. Cit., p. 209]

As Rocker summarises, “when absolutism had victoriously overcome all opposition to national unification, by its furthering of mercantilism and economic monopoly it gave the whole social evolution a direction which could only lead to capitalism.” [Op. Cit., pp. 116–7]

Mercantilist policies took many forms, including the state providing capital to new industries, exempting them from guild rules and taxes, establishing monopolies over local, foreign and colonial markets, and granting titles and pensions to successful capitalists. In terms of foreign trade, the state assisted home-grown capitalists by imposing tariffs, quotas, and prohibitions on imports. They also prohibited the export of tools and technology as well as the emigration of skilled workers to stop competition (this applied to any colonies a specific state may have had). Other policies were applied as required by the needs of specific states. For example, the English state imposed a series of Navigation Acts which forced traders to use English ships to visit its ports and colonies (this destroyed the commerce of Holland, its chief rival). Nor should the impact of war be minimised, with the demand for weapons and transportation (including ships) injecting government spending into the economy. Unsurprisingly, given this favouring of domestic industry at the expense of its rivals and the subject working class population the mercantilist period was one of generally rapid growth, particularly in England.

As we discussed in section C.10, some kind of mercantilism has always been required for a country to industrialise. Over all, as economist Paul Ormerod puts it, the “advice to follow pure free-market polices seems … to be contrary to the lessons of virtually the whole of economic history since the Industrial Revolution … every country which has moved into … strong sustained growth . .. has done so in outright violation of pure, free-market principles.” These interventions include the use of “tariff barriers” to protect infant industries, “government subsidies” and “active state intervention in the economy.” He summarises: “The model of entrepreneurial activity in the product market, with judicious state support plus repression in the labour market, seems to be a good model of economic development.” [The Death of Economics, p. 63]

Thus the social forces at work creating capitalism was a combination of capitalist activity and state action. But without the support of the state, it is doubtful that capitalist activity would have been enough to generate the initial accumulation required to start the economic ball rolling. Hence the necessity of Mercantilism in Europe and its modified cousin of state aid, tariffs and “homestead acts” in America.

#faq#anarchy faq#revolution#anarchism#daily posts#communism#anti capitalist#anti capitalism#late stage capitalism#organization#grassroots#grass roots#anarchists#libraries#leftism#social issues#economy#economics#climate change#climate crisis#climate#ecology#anarchy works#environmentalism#environment#solarpunk#anti colonialism#mutual aid#cops#police

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Everywhere Europeans looked, the indigenous people they happened upon had their own ideas of how men and women should behave. Chief among them were notions about the kind of work men and women should each perform. These differences were deeply unsettling to the colonists.

…English migrants in the 17th century were not trying to re-imagine what it meant to be male or female. Instead, these first European settlers hoped their culture and their working lives could be easily transplanted. Immigrant women and men would each perform their customary duties; husband and wives would find their roles and their relationships appreciably unaltered.

…Almost every woman who left England for Virginia or Maryland in the early 17th century would have expected to work--and work hard--from the moment she reached her destination. Between 80 and 90 percent of the English folk who emigrated to that region, and virtually all of the women, came as indentured servants. …At first, these young women toiled for men who were their masters. After their debts had been satisfied, they might work alongside their husbands on small plantations. In either case, their labors would be shaped by the broader goal of the regions’ economy: extracting from the soil the maximum possible volume of tobacco, the intoxicating leaf Londoners were craving.

…Conditions in the Chesapeake were mean--even by the standards of those who, like most indentured servants, came from the lower rungs of English society. The average planter was likely to inhabit an unpainted wooden dwelling no larger than 25 by 18 feet--about the size of a modern two-car garage. …The indentured servant’s clothing and meals were likely to be as rude as her dwelling place. Her skirts and aprons would have been fashioned of a blend of the coarsest linen and wool. And her diet, as one traveler to the region reported, consisted mainly of a ‘somewhat indigestible soup’ of ground corn. Not surprisingly, serving girls eking out this kind of meager existence often succumbed to the Chesapeake’s many endemic diseases. Malaria, pellagra, dysentery, and deadly ‘agues and fevers’ killed off many during the crucial first six months of ‘seasoning,’ as getting used to the climate was called.

…On the positive side, it meant that virtually every female migrant would eventually find a husband--should she live long enough to attain her freedom. (Indentured servants, male and female, were forbidden to marry.) But it also meant that English notions of the proper sexual division of labor simply could not apply. In a colony where land was abundant and labor was scarce, a certain degree of flexibility regarding one’s day to day tasks was an absolute necessity.

…For men and women alike, the workday stretched from sunrise to sunset, with time off during the heat of the day in the warmer months. In the winter--the beginning of the tobacco production cycle--an Englishwoman would have spent those hours helping her master or her husband plant crops and enrich the seedbeds. By late April, she might have been called upon to transplant the tiny seedlings to the main fields--a delicate task that demanded the intensive effort of the whole plantation labor force over a period of several months. In June, July, and August, her deft hands would hoe and weed the tiny hills surrounding each plant and keep the plants free from worms. September brought the arduous labor of cutting and curing the mature leaves; this was typically men’s work.

…At first, few women could be found among the enslaved labor force of the southern colonies. Most 17th-century planters thought that strong male hands made better investments. Until the 1660s, two African men were imported for every African woman. But as white settlers began to turn the servitude of blacks into chattel slavery--a lifelong, even hereditary state--the logic of enslaving more women became clear. Enslaved men could labor only so many hours in the course of a day. But, as the masters saw it, enslaved women were always working, even when they were feeding their families or delivering babies.

…Slave women deemed incapable of field labor--the very young, the infirm, and the very old--might be put to work in household service. In the first half of the 18th century, these indoor workers accounted for a distinct minority of female slaves, well under 20 percent. And being assigned to the plantation household was not necessarily desirable. …Slave women who worked in their mistresses’ homes were always on call. Their duties ranged from hard, physical labor like doing laundry and toting water, to such routine drudgery as emptying chamber posts and making beds.”

Jane Kamensky, “To Toil the Livelong Day: Working Lives” in The Colonial Mosaic: American Women, 1600-1760

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

I'm in the process of LEAVING RBC because of this..

it's shockingly convoluted and difficult to move my (Federal) Registerd Disability Savings Plan without financial penalty.

It's not as shocking that's it's been 6 weeks since the Credit Union filed the paper work and the money is still trapped with RBC tho.

A group of demonstrators gathered outside the RBC branch on Main Street Saturday to protest the organization’s support of oil and gas projects. A 2023 report called Banking on Climate Chaos revealed RBC invested over 40 billion in the fossil fuel industry in 2022. “That’s not ok,” says Kirby Cote, one of the organizers behind the demonstration. “We need to hold them accountable for the money that they’re giving people who are destroying our planet.” Cote says the rally is also meant to show solidarity with Indigenous land defenders.

Continue Reading.

Tagging: @politicsofcanada

#Evil bank is evil#the economy is meant to serve society#Royal Bank of Canada#evil financial empire#banking on Climate chaos#current events

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

Africa is poor because its exploi and its creditors with their local puppets are unspeakably rich.

The so call aid help or debt is a fraud...Afrikan resources have been converted by western societies for generations upon generations

Imperialist are not helping any african but rather furthering their own agendas."

We must denounce those whose life goal is to serve the imperialist corporations with absolute obedience and dutifulness.

Neo-imperialism is a deceptive,thieving,world resources.the earth need revolution & instincts;we have nothing to lose,stand up,rebel,revolt.

There is no way someone who robbed you off your land full of natural resources can claim that you owe him anything!.

Imperialist only care for exploi Africa resources.They don't care about the African people.They never did& that's not about to change twitter.com/conelle

Africans fighting to win material benefits,to live better&in peace,to see their lives go forward,to guarantee the future of their children;

African leaders destroy Africa by enforcing a policy of mass alienation and economical thievery of imperialist capitalis greedy.

Imperialist funding IMF is designed to take over World economy milk its resources, then have it pay tributes to the Wall Street machine.twitter.com/conelle

Racism denies people's access to life, liberty, to the pursue of happiness, to proper education, to control over their own resources etc.

Imperialist is the enemy of the Africa Nations: robbing it, exploiting it,and oppressing it.impossed corrupt leaders on it.

As long as the African people continue to refuse to deal with their past,they will continue being ruled by the colonial masters

twitter.com/conelle

Africa can only move forward,if Africans stop holding unto colonial ways.serious deconstructing is needed.

I believed then as I believe now, that the African§Blacks Race has never really gained freedom and independence.

African resources and labour were used to develop Europe and its satellites.

imperialism/colonialism/racism has been aided by Africans who were recruited into the armies of their imperialist/colonialist/racist masters.

“Neo-colonialism is also the worst form of imperialism; it means exploitation without redress.Neo-colonialism, like colonialism.

twitter.com/conelle

No people will save themselves until they know themselves and are willing to make sacrifices on behalf of themselves." John Henrik Clarke.

“The oppressors do not favor promoting the community as a whole, but rather selected leaders.”― Paulo Freire, Pedagogy of the Oppressed.

"One the information is given, there are no longer victims, only volunteers."

"You cannot destroy slavery by becoming a part of your Master’s cultural incubator." - John Henrik Clarke

Collectivization will liberate Africa from the parasitic influence of imperialist organizations like the IMF and World Bank Greedy.

Africans must revolt against the theivery economics of the filthy imperialist capitalist upper class,world Banks,wall-streets ,IMF etc.

twitter.com/conelle

"We cannot have the oppressors telling the oppressed how to rid themselves of the oppressor." Kwame Ture

twitter.com/conelle

Since Africa was invaded, the only visible development of her people is poverty which is meant to eliminate them.

Most Dangerous Blacks in the world are many of those brothers&sisters who finished graduate & yet operate against the interest of Africa.

Imperialist never brought peace,prosperity,democracy to the peoples of Asia,Africa,or Latin America,In the future,as in the past5 centuries.

twitter.com/conelle

Only the completely brainwashed could deal with the history of the European's genocidal hatred of the Afrikan without emotional pain.

The struggle of Africans is the struggle of all citizens who are pathologically oppressed by the imperialist capitalist interests.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

"“The Fascist conception of the State is all-embracing,” Benito Mussolini declared in 1919; “outside of it no human or spiritual values can exist, much less have value.” If he had left out the reference to fascism, his statement would apply perfectly to the world every state strives to create. Over the centuries, functions that local communities, religious establishments, and systems of mutual aid used to serve have gradually been absorbed into the State and transformed into agencies, nonprofit institutions, or businesses, all operating subject to law: in other words, as quasi-arms of the State. The boundaries of the State are theoretically limitless, and once it acquires a certain set of powers or resources, it does not give them up.

Here again, the State and the digital operating system resemble each other. The developers of operating systems like Windows or macOS started with an idea. They envisioned systems that could establish a comprehensive platform for executing any and every task that could possibly be carried out on a computer and then could scale up, creating a total environment that was versatile enough to absorb more and more of the activities we carry out in daily life and that could be refashioned as action via software. The State’s drive for totalization aims for something similar when, for example, it encounters a people or population who practice a different form of economic organization. The result in most cases is an ongoing war of the State and its dominant groups against Indigenous and migrant peoples and against labor. For instance, Germany’s right-wing power brokers, and then Hitler, spent the years between the world wars doing everything they could to break the country’s left working-class culture, which they regarded as a permanent revolutionary threat. Forty years later, Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher declared war on Britain’s radical mine workers because they similarly represented an obstacle to her plans to remake the economy along neoliberal lines. The aspirations of the modern State in all its varieties include a drive for cultural and economic uniformity, which it achieves through three basic tools: surveillance, control of public spaces, and deception. The history of the State is in part the history of its use of these tools against countervailing social formations—such as Indigenous societies, traditional cultural or social patterns of governance, organized religion, organized labor, and organized crime. The State tries to assimilate or suppress them, push them to the margins, or eliminate them by more violent means. A very recent example is the 2020 decision of the U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs to revoke the reservation status of the Mashpee Wampanoag, established only thirteen years earlier, which meant that a portion of their lands was no longer held in trust for the tribe." -The operating system: An anarchist theory of the modern state

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

By: C.R. Hallpike

Published: Apr 1, 2024

In an age when Western science is condemned as an expression of colonialism and white supremacy, it’s not surprising that these feelings of moral outrage have extended to anthropology. Traditionally, anthropology has had a special interest in studying tribal or “primitive” societies. These are small, face-to-face communities with subsistence economies and simple technologies, without writing, money, or centralized governance. They have a very limited division of labour and are organised primarily on the basis of kinship, age, and sex. Far from being isolated or insignificant oddities, they have, for most of history, represented the predominant type of human society across the globe. However, they have been increasingly dominated by the great empires of the ancient world and, in more modern times, subjected primarily to European colonisation.

While there were occasional descriptions of these societies by government officials, missionaries, and assorted travellers, the absence of writing in tribal societies meant that a detailed examination of them required professional anthropologists to live among them for one or two years of fieldwork. These anthropologists had to learn the unwritten indigenous languages and compare their findings with those of their peers to develop a general theoretical understanding of how such societies functioned. This was a vital contribution to our understanding of what it means to be human, and for a hundred years or so anthropological fieldworkers, mainly from Europe and America, accumulated a vast store of ethnographic data. This work not only greatly contributed to our knowledge but also served as a priceless record of these societies in their traditional states before they were radically transformed by the various forces of modernization.

In the nature of things, anthropologists were only able to carry out fieldwork in these societies when law and order had been imposed by colonial governments, which has led many contemporary academics in our highly politicized landscape to accuse anthropology of being a colonialist enterprise. The Pitt Rivers Museum recently proclaimed, “Coloniality divides the world up into ‘the West and the rest,’ and assigns racial, intellectual and cultural superiority to the West.” The very obvious fact that human societies exhibit differing degrees of complexity was described as the creation of “Racialised hierarchies linked to intelligence.” Instead, it argues, modern anthropology’s goal should be to foster “an inclusive space welcoming to all” (cited in Hallpike 2024).

Consequently, traditional anthropology is now viewed as a threat to the dignity and well-being of tribal societies, and a continuation of colonial oppression of the powerless. For example, an American anthropologist recently criticized the practice of making audio recordings during fieldwork, even when the indigenes themselves have sold these recordings, as perpetuating an “extraction mindset” akin to mining companies extracting mineral resources from the land. As a result, she decided not to record any of the interviews she obtained in her fieldwork to avoid continuing “the legacy of extraction” (cited in Weiss 2022).

This “extraction mindset” has, rather more graphically, been described as “stealing with the eyes.”

This phrase emerged from the experience of a young man named Will Buckingham who became interested in anthropology at university and decided to study the work of traditional sculptors in the Tanimbar Islands of Indonesia. Despite his lack of formal qualifications in anthropology and limited knowledge of Indonesia and its language, he surprisingly received permission from the Indonesian Government to carry out his research in 1994-1995. His book, titled Stealing with the Eyes, published in 2018, was inspired by his meeting with the native sculptor Matias Fatruan:

Matias held up his hand. He spoke softly. “I do not think that you have come to steal with the hands,” he said. “I think that you have come to steal with the eyes.” Matias’s gaze was steady. I looked away guiltily. Curi mata: stealing with the eyes. The accusation was inescapable. What else did Westerners do, the whole world over, if not this? They roved here and there, taking other people’s lives and homes as things to be photographed, consumed, ferried back home. Wasn’t anthropology itself no more than a vast enterprise of stealing with the eyes? Wasn’t the entire world, under the guise of knowledge and science, a cabinet of curiosity for the West? (Buckingham 2018: 54).

However, readers of his book may well question his credentials to critique anthropology at all. When Buckingham went to Tanimbar, he lacked any qualifications in anthropology and had only a basic understanding of Indonesian. He spent just a few months there, and his book, which largely focuses on his meetings with various individuals, is an amateurish piece of ethnography that provides scant insight into Tanimbar society and culture. Despite calling anthropology a “queasy enterprise at the tag end of colonialism,” its moral ambiguities troubled him so deeply that he became seriously ill, leading to vomiting, giddiness, headaches and fever. Doctors could not help him, and he only recovered by abandoning anthropology altogether and writing books of popular philosophy instead.

Here, it is essential to inject some ethnographic reality into his notion of “stealing with the eyes.” Professor James Fox, from the Australian National University and a leading authority on Indonesia, has this to say about it:

The problem I have with Buckingham is that curi mata does not have the literal meaning that he has imposed upon it. An approximation of curi mata in English might be “to steal a look”: hence, in different contexts, it might mean “to glance” or “to preview” or possibly even “to spy.” He obviously didn’t have enough command of eastern Indonesian Malay to understand his informants and therefore as a philosopher has been able to erect his argument based on his misunderstanding.

Obviously, observing people in alien societies and writing down one’s experiences—so-called “stealing with the eyes”—is not stealing in any meaningful sense of the word because it doesn’t deprive anyone of anything. As it stands, this phrase is merely a morbid and fantastical expression of liberal guilt. However, the American anthropologist’s refusal to record interviews, alongside Buckingham’s aversion to collecting ethnographic data, both point to a deeper issue: the belief that extracting information from native informants for the anthropologist’s professional gain constitutes a form of exploitation, with individuals from wealthier countries benefiting at the expense of those in poorer countries by publishing books and earning professional acclaim from their experiences.

This is a trivial and sentimental view that simply fails to understand the realities of the fieldwork situation. Local participants are not obligated to share information with anthropologists and are perfectly free to ignore them, tell them to mind their own business, or tell them off if they are offended. Often, they find the strange anthropologist an interesting novelty and in many cases approve of what they are doing. So when the Konso of Ethiopia asked me why I had come to live with them, I replied that I would write a book that would tell their grandchildren how they had lived. This pleased them very much and has subsequently become true and my book is a much valued record of their traditions.

I always paid informants for texts they dictated to me, for objects they sold to me, and for many other services. I also gave them a good deal of medicine. Upon leaving the village where I first lived, the elders gave me back a month’s rent because they said they had enjoyed having me there, and hoped I would become a big man in my country. The Tauade of Papua New Guinea were interested in having me live with them primarily for access to commodities like sugar and tobacco. Most of them had no interest in giving me texts, but I had one very intelligent informant who was most interested in what I was doing and gave me a tremendous amount of information without which I could never have succeeded in writing my detailed account of Tauade society. Over a couple of years he was paid a significant amount of money, and gave me his grandfather’s skull as a farewell gift.

In general, people enjoy talking about their own society and customs with those who take a sincere and intelligent interest in them, and welcome the opportunity to explain them to outsiders. On the other hand, one must obviously behave with tact and politeness, and respect their customs. For example, I spent some time in my early months among the Konso mapping the large village where I was living, when I was told that people were becoming upset, I immediately stopped and waited until I had a better command of the language. Then I called the elders together and told them that the wise men in my country would want to see a map of the village to proved that I had lived there. They were quite happy with this explanation and told me to do as much mapping as I wanted to.

On another occasion, it came on to rain heavily after dark in the growing season, and some of the men ran out naked into the fields to check the irrigation channels. I went out with them but they felt that this was an intrusion, as they conveyed to me tersely the next morning by saying, “The day is yours; the night is ours.”

It is also quite normal to quarrel with people if they behave offensively. In one instance with the Tauade, a man brought along his wife to see me because her arm had been broken by a man who had hit her with his axe. I bound up her injury and wrote a letter to the Assistant District Commissioner explaining the case, and the culprit was jailed. Later, her husband held a small pig-killing to celebrate his wife’s recovery, as was traditional.As the distribution of pork proceeded it became clear that I was not going to receive any, as I was entitled to. I was absolutely furious and challenged her husband: “Anamara, why have you not given me pork today? I know your customs. I bound up your wife’s wound and wrote a letter to the kaubada, why have you not given me pork?” He was speechless. So I continued, “I’ll tell you why. You are just a wild pig.” I then turned and walked away. He rushed after me, waving a ten dollar bill, with Amo, my chief informant, who said that Anamara wanted to wipe out the insult. We returned to the kiava, where he presented the money to me. I told him that this settled the matter and returned home. Amo soon joined me, roaring with laughter, and told me that I was a real Tauade. This experience brought me closer to the people and improved my standing among them because I had behaved as one of their own.

Writing ethnographies of tribal societies was inevitably something only literate outsiders could accomplish in the first instance, but it was always inherently collaborative because it depended on the cooperation of the people being studied. As time passed and education spread, it became possible for the native peoples to began contributing significantly to their own ethnographies. So on returning to the Konso in 1997, thirty years after my initial study, I discovered that an educated Konso had written a valuable history of their people, which I frequently cited in the revised edition of my own book on the Konso (Hallpike 2008). He and all the other Konso who helped me would have found the accusation of “stealing with the eyes” not just absurd but incomprehensible.

In summary, writing an accurate account of a people who lack written records or literature enables them to leave a voice behind them in human history, instead of vanishing, silent and anonymous, into the mists of time. It also greatly contributes to our understanding of the human race by illustrating how we think and behave under a wide variety of conditions and helps explain how we reached our present circumstances.

Anthropology has been one of the most humane endeavors in the history of Western scholarship, and I am very proud to have contributed to it.

--

About the Author

Christopher Hallpike is Emeritus Professor of Anthropology at McMaster University, Canada. He studied anthropology at Oxford under Evans-Pritchard and Rodney Needham, and then carried out extensive fieldwork among the Konso of Ethiopia and the Tauade of Papua New Guinea. He is the author of many books not only on the Konso and the Tauade but on the major topics of anthropology, such as The Foundations of Primitive Thought and The Principles of Social Evolution. You can find out more about his work on his website.

==

Postmodernism has completely rotted out some people's brains.

#Christopher Hallpike#anthropology#stealing with the eyes#extraction mindset#postmodernism#science#colonialism#white supremacy#religion is a mental illness

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

just some thoughts under the cut.

this is a mixed bag of a post.

it's true that the idea of a husband going to work and the wife just staying home is definitely a very very modern idea.

but the rest of the first paragraph is a bit questionable. the system before "the factory ate up humanity"? not sure what's meant by this. before the industrial revolution? before capitalism? what is the system that preceded these? you mean agrarian feudalism? where most people (like 90%, depending on the region) were farmers?

yeah most men, throughout history, did NOT "have his own business or enterprise". as i said, most men would have been peasant farmers. maybe a tiny percentage were lucky enough to be yeomen/freeholders. but yeah, men and women, for most of this period, would have both been doing lots of work around the farm. in urban areas, maybe the women would work as laundry workers, chamber maids, prostitutes, weavers, brewers, midwives, etc.

yeah if a woman was lucky enough to be married to a man who did operate his own enterprise she most definitely would have helped him with it but this wasn't a common situation. it'd be the premodern equivalent of being upper class.

in fact, this is one of the things that makes america so special because it actually broke this mold. from america's founding onward we have had a high rate of independent (family run) businesses, yeomen farmers, homesteaders, land ownership, etc. so yeah what she's describing here only would have really been relatively common in america (post-industrial revolution).

also, i don't know how true it is that people has less debt. debt has been an issue since time immemorial. but i also don't believe less debt necessarily means wealthier? in fact, in reality it seems like the opposite. many of the richest people in the world have lots of debt. most of the richest countries also have lots of debt. debt almost seems like a prerequisite for debt.

had more freedom? in what sense?

their work was meaningful? according to what metric? and compared to what? i live in a town that has a pretty strong manufacturing base and i know the factory works are very proud of and find a lot of meaning in their work.

they had more time with each other? perhaps.

"The "trads" lament that women must go to work instead of being with their families. But they have no problem with men suffering this fate. The reality, the true traditional reality, is that this "office work" is for neither man nor woman. It is an inhuman modern invention for organizing work and it serves mainly those who want to make money from interest."

i mean, yeah, obvious i support people in general, both men and women, getting more time to spend with their families. but like in "traditional" societies everyone is still working. even the kids for the most part. it's not like everyone is just chilling together all day. and even in premodern times there were still office jobs and clerical/administrative roles and bureaucracy and all that. that stuff isn't any more inhuman or modern than pretty much any other job short of hunting and gathering. like, i've seen people say agriculture is inhuman/unnatural. i personally think that's silly but you do you.

again, i'm in favor of reducing the amount of work people do and increasing time spent with family and for recreation and stuff. but this just seems no better than the idiotic prattle of other trads.

speaking as someone who has spent my life doing backbreaking manual labor and whose body is already breaking down as i approach the age of 30 i'd love having an office job. in fact in premodern times having an "office job" would have been "making it". the way everyone wants their kids to become doctors and lawyers and computer programmers, premodern folks wanted their kids to become priests and scribes and accountants and so on. there's a reason why people are leaving their "traditional economy"-based countries and rushing to becoming office workers in modern economies.

not saying office jobs are extremely fulfilling or anything. but digging ditches or pulling weeds ain't that fulfilling either. most jobs in general are just shit. lmao. if they were fun times you wouldn't have to be paid to do them.

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

I wish we could finally abandon the notion that people are meant to serve as cogs and wheels in an economy at all. Consumers, laborers, economic functions. I think people are getting upset about all the wrong things in this tired little argument. They're either taking it too personally or are being too cold or detached to see how they both miss the point. Let the poor person take it personally when they're overlooked for that $600 or are denied outright. Let them feel that. We, who are a bit removed from the immediacy of that context, even if we're just as poor, have to try to fix the problem, not just tit-for-tat the sociopathic-sounding rich people. It's true, the economy only works if people are spending money! But the solutions aren't to ensure that people are consuming. The money given to poor people might as well only superficially be charitable, because the moment it's spent it's become profits for the middle and upper-classes. That's how even the middle class can be trapped into living paycheck to paycheck, except for the lower classes it's worse than merely worrying about rent or bills. Once we establish how insufficient financial assistance for the poor truly is, and how it basically subsidizes unjust establishment inequality-- then we can begin to acknowledge how much worth and value there is in facets of society and material conditions which are not commodities and can support and uplift people without benefiting at their expense. Systems, practices, and designs which nobody can easily manipulate for selfish gain, ranging from urban food forests to the open source software development community and developed technology.

So poor people don’t deserve to have money?!

112K notes

·

View notes

Text

Ownership & Misconceptions

CW: Mild politics, educational sexual topics, etc.

I think people who have not experienced what being transgender is like don't understand the extents to which the concept of femininity has been corrupted. Even if you disagree with the notion, looking at gender from the perspective of someone who thinks it is purely performative how do you expect young trans women to act? You promote and prop up a media ecosystem that shoves the Kardashians in our face and tells us 'this is what femininity looks like — this is what you should aspire to be,' and then wonder why these girls/women are trying to be the most promiscuous they can possibly be, buying lip fillers, false eyelashes, and all sorts of products to conform to a male euro-normative standard of excessive beauty and attractiveness. Then we have the topic no one wants to discuss. Whilst I can't speak for other countries, in the United States it is pretty clear what a large portion of men think of women in our society. A large amount of you think they are literally and unironically property without rights meant to be barefoot and pregnant. You think women exist purely to serve men. And I would even venture to extrapolate or guess, a lot of women co-signed this narrative with their vote. There is no subsection on your ballot that includes categories such as the economy, global peace, world hunger or whatever other topic that is making you a one issue voter. All of you basically just told me with your vote over half of you do not care about lying, cheating, stealing, sexism or racism so long as it saves you "a few dollars" on eggs. So to get back to the point, the question still remains why are cis conservative men surprised when trans women (the same as your daughters at puberty) choose to go to the most hyper sexualized extremes of what society has told us to believe is "feminine"? You act surprised when they have a thing for being subservient. Now, I know I'm gonna have some ladies attack me for these comments and I hope you can pardon my cartoonish approach to this argument. I titled this post "Ownership & Misconceptions" because I think nosey straight white men need to take some ownership of the standards they've set for us. However, the honest truth is that cis women are horny too. I have cisgender heterosexual friends who are just as kinky (if not worse) than I am. I'm merely illustrating for those of us unfamiliar why you'll see the trans girl "trad wife" blogs. Admittedly I went through my own "stepford" phase until my dom basically shoved me away and told me he couldn't bring himself to "be with a trans woman". But my overall point is they're doing with trans people what they did with the gays in my parents day. They're making us the "other" and saying that we lack discipline and self control and therefore we need to be controlled. "Look at their wild sexuality! We must do something!". We don't give a sh*t about your children, or your bathrooms, or your libraries. We just want to be treated like human beings. Stop calling us pedophiles just because it fits your narrative.

0 notes

Text

How Has the Role of IAS Officers Evolved Since Independence?

The Indian Administrative Service (IAS) has long been hailed as the backbone of India's bureaucratic framework. Since its inception post-Independence, the role of IAS officers has transformed significantly. The service is known for its ability to adapt to changing political, economic, and social landscapes. From playing a key role in nation-building to addressing contemporary challenges like digitization and sustainability, IAS officers have evolved in multifaceted ways.

The Origins of IAS: A Colonial Legacy Recast

The IAS was established in 1946, just before India gained Independence, as a successor to the Indian Civil Service (ICS) — the bureaucratic machinery of British India. While the ICS served colonial interests, the newly-formed IAS was tasked with nation-building, carrying the heavy responsibility of steering India from a colonized state to a democratic republic. The early years after Independence saw IAS officers working closely with political leaders, focusing on the administration of newly-formed states, maintaining law and order, and implementing the five-year plans introduced to boost India’s economy.

IAS officers were seen as key agents in stabilizing the newly-independent nation, playing an instrumental role in public administration and policy execution. Their responsibilities in the early years primarily revolved around governance, development planning, resource management, and overseeing elections.

Nation Building: The Initial Decades

In the 1950s and 60s, IAS officers were primarily focused on nation-building efforts. The newly-formed Indian government leaned heavily on the bureaucracy to implement economic policies and reforms aimed at poverty alleviation and industrial development. The "commanding heights" philosophy of the Indian economy meant that IAS officers were entrusted with major responsibilities, including managing large public sector undertakings and implementing land reforms.

IAS officers were the connecting link between the government’s ambitious developmental goals and the on-ground implementation at state and district levels. Their responsibilities were wide-ranging, from overseeing public welfare schemes to managing infrastructural projects.

Bank exam coaching center in Coimbatore institutions often look up to these civil servants as role models for leadership and governance, citing examples of how efficiently they executed nation-building policies during this period. The skill set required to manage such high-stakes responsibilities was vast, setting the stage for future reforms and further expansion of the IAS's role.

Economic Liberalization: A Paradigm Shift

The 1990s brought about a drastic shift in India’s economic policies with the introduction of liberalization, privatization, and globalization (LPG) reforms. With these came an entirely new set of challenges for IAS officers. The role of the bureaucracy needed to adapt from managing a controlled economy to one that embraced open markets. This transformation had profound effects on the responsibilities of IAS officers, as they were no longer just policymakers but facilitators of a growing private sector.

IAS officers had to ensure that the new economic policies were implemented efficiently while also balancing the demands of a globalized market economy. They became key players in formulating strategies to attract foreign investment, ensuring that reforms translated into inclusive growth, and managing the repercussions of privatization on public-sector employees.

The liberalization era also saw a shift in the perception of governance. IAS officers now had to engage more with stakeholders from the private sector, civil society, and international organizations. They had to manage large-scale infrastructure projects and navigate the complexities of modern-day financial governance.

Expanding Scope: Social Sector Reforms and Technology

Post-2000, the role of IAS officers further expanded with the introduction of various social sector reforms aimed at improving education, healthcare, and rural development. The launch of schemes like the National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (NREGA), Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan, and mid-day meal programs saw IAS officers take on more focused roles in ensuring that these benefits reached the grassroots level.

This period also marked a major shift towards the digitalization of government services. The introduction of e-governance initiatives meant that IAS officers had to adopt technology and ensure that administrative processes became more transparent, accountable, and efficient. The Digital India initiative was a major milestone in this regard, pushing IAS officers to spearhead the integration of technology in service delivery.

IAS officers began to lead initiatives that used big data analytics, digital platforms, and social media tools for better public governance. This transformation helped bridge the gap between government policies and citizens, ensuring that information dissemination and policy implementation were more effective.

Bank exam coaching center in Coimbatore often cites the importance of digital tools for modern governance, providing students with case studies on how IAS officers have efficiently used technology to combat corruption and improve service delivery across sectors like education, health, and infrastructure.

Contemporary Challenges: Climate Change and Sustainability

In recent years, IAS officers have found themselves at the forefront of dealing with global challenges like climate change and sustainability. With India being one of the most vulnerable nations to climate change, the role of IAS officers has evolved to include environmental governance. They are now key stakeholders in implementing the Paris Agreement and ensuring that India meets its climate change goals.

From managing the fallout of extreme weather events like floods and droughts to promoting renewable energy and sustainable agricultural practices, IAS officers are responsible for driving India’s sustainability agenda. They are tasked with implementing policies that balance economic growth with environmental protection, a role that has gained prominence in the 21st century.

IAS Officers as Agents of Social Change

Beyond economic development and environmental sustainability, IAS officers have become agents of social change. In recent years, they have been tasked with implementing policies related to gender equality, the empowerment of marginalized communities, and addressing social inequalities. The role of the IAS officer today is not just about governance; it is about ensuring social justice and promoting inclusiveness in all areas of life.

Through their efforts in rural development, education, healthcare, and women’s empowerment, IAS officers play a pivotal role in creating a more equitable society. Their focus has shifted from simply implementing policies to driving change, fostering community participation, and ensuring that the benefits of development reach every corner of the country.

Adapting to Political and Social Complexities

In a diverse country like India, political and social complexities can often lead to challenges in governance. IAS officers have increasingly found themselves managing sensitive issues such as regionalism, caste-based conflicts, and religious tensions. Their role has expanded to being conflict mediators and social integrators, ensuring that development reaches all communities without discrimination.

Moreover, IAS officers have had to navigate the changing political landscape, maintaining the delicate balance between working with elected representatives and safeguarding the autonomy of the civil service. Their role has become even more significant in states with coalition governments, where navigating political differences becomes part of their administrative responsibilities.

Conclusion

Since Independence, the role of IAS officers has evolved dramatically. From being the administrative backbone of a newly-formed republic to becoming agents of social, economic, and environmental change, IAS officers today are expected to be multi-faceted leaders. They are no longer just bureaucrats; they are technocrats, policy advisors, conflict managers, and social change-makers.

As India continues to face new challenges in the 21st century — from climate change to digital governance — the IAS will continue to evolve, adapting to the nation’s needs. Aspiring civil servants, such as those preparing at Bank exam coaching center in Coimbatore, can look to the evolving role of IAS officers for inspiration and guidance on how to navigate the complexities of modern governance.

#IASLeadership #IndianAdministrativeService #BankExamCoachingCenterInCoimbatore

0 notes

Text

G.1.2 What about their support of “private property”?

The notion that because the Individualist Anarchists supported “private property” they supported capitalism is distinctly wrong. This is for two reasons. Firstly, private property is not the distinctive aspect of capitalism — exploitation of wage labour is. Secondly, and more importantly, what the Individualist Anarchists meant by “private property” (or “property”) was distinctly different than what is meant by theorists on the “libertarian”-right or what is commonly accepted as “private property” under capitalism. Thus support of private property does not indicate a support for capitalism.

On the first issue, it is important to note that there are many different kinds of private property. If quoting Karl Marx is not too out of place:

“Political economy confuses, on principle, two very different kinds of private property, one of which rests on the labour of the producer himself, and the other on the exploitation of the labour of others. It forgets that the latter is not only the direct antithesis of the former, but grows on the former’s tomb and nowhere else. “In Western Europe, the homeland of political economy, the process of primitive accumulation is more of less accomplished … “It is otherwise in the colonies. There the capitalist regime constantly comes up against the obstacle presented by the producer, who, as owner of his own conditions of labour, employs that labour to enrich himself instead of the capitalist. The contradiction of these two diametrically opposed economic systems has its practical manifestation here in the struggle between them.” [Capital, vol. 1, p. 931]

So, under capitalism, “property turns out to be the right, on the part of the capitalist, to appropriate the unpaid labour of others, or its product, and the impossibility, on the part of the worker, of appropriating his own product.” In other words, property is not viewed as being identical with capitalism. “The historical conditions of [Capital’s] existence are by no means given with the mere circulation of money and commodities. It arises only when the owner of the means of production and subsistence finds the free worker available on the market, as the seller of his own labour-power.” Thus wage-labour, for Marx, is the necessary pre-condition for capitalism, not “private property” as such as “the means of production and subsistence, while they remain the property of the immediate producer, are not capital. They only become capital under circumstances in which they serve at the same time as means of exploitation of, and domination over, the worker.” [Op. Cit., p. 730, p. 264 and p. 938]

For Engels, ”[b]efore capitalistic production” industry was “based upon the private property of the labourers in their means of production”, i.e., “the agriculture of the small peasant” and “the handicrafts organised in guilds.” Capitalism, he argued, was based on capitalists owning ”social means of production only workable by a collectivity of men” and so they “appropriated … the product of the labour of others.” Both, it should be noted, had also made this same distinction in the Communist Manifesto, stating that “the distinguishing feature of Communism is not the abolition of property generally, but the abolition of bourgeois property.” Artisan and peasant property is “a form that preceded the bourgeois form” which there “is no need to abolish” as “the development of industry has to a great extent already destroyed it.” This means that communism “derives no man of the power to appropriate the products of society; all that it does is to deprive him of the power to subjugate the labour of others by means of such appropriation.” [Marx and Engels, Selected Works, p. 412, p. 413, p. 414, p. 47 and p. 49]

We quote Marx and Engels simply because as authorities on socialism go, they are ones that right-“libertarians” (or Marxists, for that matter) cannot ignore or dismiss. Needless to say, they are presenting an identical analysis to that of Proudhon in What is Property? and, significantly, Godwin in his Political Justice (although, of course, the conclusions drawn from this common critique of capitalism were radically different in the case of Proudhon). This is, it must be stressed, simply Proudhon’s distinction between property and possession (see section B.3.1). The former is theft and despotism, the latter is liberty. In other words, for genuine anarchists, “property” is a social relation and that a key element of anarchist thinking (both social and individualist) was the need to redefine that relation in accord with standards of liberty and justice.