#picaresque-hero

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Ways The Vampire Lestat is like an 18th century novel

slippage between "fact" and fiction. Early novels like Robinson Crusoe were often taken to be (and marketed as) true accounts since audiences were less familiar with long form narrative fiction. Lestat of course flips this concept on its head by publishing his life story as fiction.

Picaresque plot. Lestat is a lovable scamp who stumbles into a series of scrapes and episodic adventures, much like Daniel Defoe's Moll Flanders or Henry Fielding's Tom Jones.

Also like Moll Flanders and Tom Jones, Lestat engages in a smidge of incest (though in his case it's not an accidental oopsie).

Lestat is a sentimental hero, an 18th century Man of Feeling--his many, many tearful breakdowns recall a common motif of heroes crying at moments of realization/climax/emotional significance (lookin' at you, Young Werther).

Overall, it has a real sense of abundance about it, that "more is more" feeling you often find in novels of the period--particularly in works with a satirical bent like Sterne's Tristram Shandy and Voltaire's Candide, and even the vicious, pitch-black fictions of the Marquis de Sade with horrors layered upon horrors until the effect becomes comic. You just do not know wtf is gonna happen from one page to the next.

Of course, it also has a lot of gothic novel DNA in there. The eroticized horror of Matthew Lewis's The Monk comes to mind.

It has first-person narration, as was common for early novels, which were often epistolary. (Side note: how fun would it be if TVL was a series of increasingly unhinged letters to Louis?)

I'm sure I could think of a few more examples if I really dug into the ol' bookshelf lol. Lestat is a man of his time, and the way he presents his story reflects that in some interesting ways!

#thank you for indulging my rant#vc meta#the vampire lestat#lestat de lioncourt#amc iwtv#the specialest boy#vc#vampire chronicles

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

All of us tell ourselves some kind of story about our lives. Sometimes our story will weave the fragments of our experience into a greater whole, in a way that reveals relationship, connection, a clearer context. But sometimes our story is such a distorted narrative that it doesn’t serve to bear our sorrows -- instead it serves to extend them. Our theme might be the pursuit of money, sex, or prestige; it might center around love or spirituality. Some of us figure as a hero in the story, some as an anti-hero. Our story might be picaresque, romantic or tragic. We might frame ourselves as optimists or as pessimists, winners or losers. How we interpret our own experiences gives rise to the narratives to which we then usually dedicate our lives.

— Sharon Salzberg, Faith: Trusting Our Own Deepest Experience

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

🫀ART REQUESTS ARE OPEN🫀

My YouTube channel

▄▀▄▀▄▀▄▀▄▀▄▀▄▀▄▀▄▀▄▀▄▀▄▀▄▀▄▀▄▀▄▀▄

"Ladies and Gentlemen, we proudly present a picaresque score of passing fancy "

Sup, faggot I am Deimos Breakfrost and this is my gay-ass blog!

▄▀▄▀▄▀▄▀▄▀▄▀▄▀▄▀▄▀▄▀▄▀▄▀▄▀▄▀▄▀▄▀▄

Alter-egos?

💋 @totalswap-official

💗 @ripper-fanclub

❗ @positive-mlm-total-drama-takez

▄▀▄▀▄▀▄▀▄▀▄▀▄▀▄▀▄▀▄▀▄▀▄▀▄▀▄▀▄▀▄▀▄

(My Mutuals ♥️♥️)

@straw-shark-berry @waykner @fire-feather-flies @c4ndyl0l @chocot0rro

@r4bidcherry @pawzofchaos @lung-worm2023 @wheredidalltheusersgo @gallonwghost

@marrfixated @averagehorrorlover @cinnam0nspider @estrelarabiscada @frontallobotomy03

@larryzstars @i-wanna-show-you-off @the-passer-outer @turtlealliebrainrot @mizukiakiyama-tdi

@horrorgator-terrordile @artic-star @thymosnova @notquitehuman-creations @sweatyparadiseearthquake

@sometimesieatexpiredcatfoof @bowlia @cunt-removal @maddythesadone @littlegoblininyourshoe

@verybald @saccgiriangel @kokodree @ukiharavara @35centtoothpaste

@aoxql @miraculousloverandhater @lycanpunk666 @st4rzl1k3c0nf3t1 @strawbsswift13-2

@theangelcatalogue @autistictojisuzuharafan11

▄▀▄▀▄▀▄▀▄▀▄▀▄▀▄▀▄▀▄▀▄▀▄▀▄▀▄▀▄▀▄▀▄

Learn more about me...

GET THE F*CK AWAY FROM ME/DO NO INTERACT:

Pedos,

Zoophiles,

Proshippers,

Racists/RCTAS,

Furrys that are 18+,

Therians(NO EXCEPIONS),

Anti-Furrys,

Catemoji Fans,

People that get on likes to make fandom dramas/fandom discourses

people that get mad at GAY MEN for saying the f slur.

▄▀▄▀▄▀▄▀▄▀▄▀▄▀▄▀▄▀▄▀▄▀▄▀▄▀▄▀▄▀▄▀▄

Basic information:

my real name is Bernard

I'm a minor (13-14 years old)

gay cis and I use He/him (respect me, bitch!)

Brazilian and half Italian I speak Portuguese PT-BR🇧🇷 and English EN-AM🇺🇸

Green Day, My chemical romance, Pierce the Veil, Fall out Boy, Falling in Reverse, Ice Nine Kills fan

Emo/scene/Punk/Rock/Sigilcore music enjoyer

I FUCKING LOVE HORROR PUNK, DEAD MEAT, KILL COUNTS, THE MISFITS AND ICE NINE KILLS

My birthday is on 20/06

Owen, Noah, Sam, Scott, Shawn, Rodney, Beardo, Lorenzo, Chet, Spud, Ripper and Chase are my favorites😭😭

Joining the TDI and JJBA fandoms! (More active on TDI but I know pratically every thing about JJBA!)

Less active but kinda knows about it on the; Pokemon, Ace attorney, Evangelion, Danganronpa fandoms (I am slowing re-liking Danganronpa help)

▄▀▄▀▄▀▄▀▄▀▄▀▄▀▄▀▄▀▄▀▄▀▄▀▄▀▄▀▄▀▄▀▄

Unnecessary informations:

Ronnie Radke's real son, trust/j

Yes I LOVE fat men and I'll go insane if I don't draw one per day😻

I hate tøp, like, for YEARS and idk why

if you like alenoah/Jacnoah oh my god get the fuck out/j /not joking

I'm not a hero by fir is literally me

I fucking love nightmare on elm street

yeah if you're a therian get the fuck ou please. You guys make me extremely uncomfortable and unsafe, go away.

▄▀▄▀▄▀▄▀▄▀▄▀▄▀▄▀▄▀▄▀▄▀▄▀▄▀▄▀▄▀▄▀▄

#intro post#introductory post#tdi#total drama#total drama 2023#jjba#jojo bizarre adventure#ace attorney#pokemon#evangelion#idk what else to tag#Spotify#ice nine kills#ink#mcr#my chemical romance#green day

71 notes

·

View notes

Note

Does Asheera have a favorite genre of book to read? >:3

Thank you for this fun Asheera question! 💜

Absolutely.

If we're talking about novels then... she loves adventure stories about larger-than-life heroes but she's got a soft spot for a picaresque that turns into a redemption story for the brash, unpleasant protagonist. She's not as much into the smutty stuff like Shadowheart, but there's the occasional genre crossover. They might share books now and again if it's something worth exploring later.

But what she really loves to read is poetry, especially romantic poetry that's bordering on completely overwritten. Sometimes the real deal that's way over the edge into purple territory. She just loves cheesy romance written from the perspective of someone pining for an unrequited love or, even better, a mushy, sappy poem about how much the writer adores their subject.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

One of the most unfortunate notions to have emerged from the afterbirth of the very odd resurgency of Puritanical morality (in regards specifically to literature as well as to fictive works of film and/or television) is the idea that characters must be inhuman in their goodness.

Not in that they must be angels, or that they must be without moral quandary, but that they must, in the end, transmute these struggles into redemption, or, at the very least, into qualities which render them more sympathetic than condemnable.

That, however, renders a disservice unto readers. As poetry, if one were to align one's views with Wordsworth, the purpose of a literary work is to contain "the spontaneous overflow of feelings," and thus to evoke such in those who consume it.

There must be catharsis. A good character is not so necessarily because he is morally good, or because he is an embodiment of our most noble and admirable traits (though well-written and well-rounded characters certainly can be so), or because he serves to bolster a work whose exigesis would extoll the virtues of a parable, but because he is deeply human; because he is multi-faceted; because he is flawed.

Humans are not paragons of virtue. To hold a character to the standards of perfection expected of martyrs is to divest the character of his humanity, and, thus, of his use to us. Characters do not need to be role models, or motivational, or inspirational, they simply must speak to our humanity.

It is dishonest to claim that humans (at least, those worthy of respecting, according to those braying the loudest within communal spaces that they have never experienced an incorrect thought, nor held a questionable belief, nor behaved in a way they would wish to keep from being broadcasted across the Internet) do not possess traits which are reflected in well-crafted, realistic characters: in Byronic heroes, in Romantic heroes, in Picaresque heroes, in anti-heroes, in the wicked, in the cruel, in the sadistic, in the mad.

It is necessary to recognise these traits within ourselves and to endeavour to become truly, intimately familiar with them. You must know the darkness of yourself as well as the light, if you truly wish to grow into a functional, kind, and well-balanced individual: you must learn to deal with your shadow. Those who pretend it does not exist within themselves often struggle the most with its existence, and often are the most easily consumed by it.

Characters who are darkly relatable to us, in their quickness to anger or in their sardonic, mean-spirited wit, or in their selfishness, or in their impulsiveness, or in their stubbornness, or in their wrath, are the most instructive in conveying the importance of goodness.

There must be catharsis. There must be purgation. We must see the darkness behind our eyes reflected in the faces of these characters, and we must see them fail because of it. We must see them hurt those they love because of it. We must see them lose everything because of it. We must see them destroy themselves because of it.

We must be allowed to explore the darkness of humanity within fiction, because it is that acknowledgement of darkness that allows us to wrestle with it, to know it, and to best it. No monster in the closet has ever been defeated by refusing to look it in the face and to name it. You cannot heal if you do not identify and treat the wound.

It is through the morally upright and the morally contemptible characters that we find traces of ourselves, and that we are allowed to proceed forward on the path to becoming the well-rounded, mature, and critical-thinking individuals we aspire to be. To continue to strike down 'problematic' content and characters is to sit beside the book burners of Fahrenheit 451, to worship Big Brother in 1984.

The good and the bad aspects of oneself must be explored in equal measure to grasp reality by the shoulders and to sit upon the throne of your identity, confident in the knowledge that your mastery of yourself and your answer to who am I? can never be shaken by outside forces.

The best and safest way to explore these aspects is within the sheltering confines of literature, of music, of film, of television, to see ourselves in the faces of others and to know what that means. To know what it means in others. To grow empathy and compassion and acknowledgement that all are human, all are imperfect, all are light, and all are dark -- and to not only acknowledge these facts, but to accept them as being inescapable, as being inherent, and as being okay.

#literature is and should be problematic#literature#censorship#book banning#literary analysis#puritanism#neo puritanism#mine

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

The First Picaresque Novel

"My name is Lazarillo de Tormes"

A highly provocative opening sentence! Especially for an educated 16th century reader, who can understand what that name means. Like the heroes of chivalric romances, the narrator bears a name that denotes his destination; here, Lazarus determines his destiny – the patron saint of lepers and beggars*.

In a Spain obsessed with purity of blood, Lazarillo does not hesitate to confess his racially** and socially suspect origin: his father was a miller and had been convicted for "bleeding the sacks" of his customers' grain; his mother got in trouble for her relation with a black man of questionable morals*** who visited her repeatedly, resulting in the birth of Lazarillo's little brother: "a black baby boy, beautiful".

No noble titles, no property, no respectable origins: who is this man who boasts of his obscure descent, as if it were a badge of honour? A rogue! A pícaro!

In 1554, a short and anonymous autobiography gets published simultaneously in Burgos, in Alcalá de Henares, and in Antwerp: La Vida de Lazarillo de Tormes (The Life of Lazarillo from Tormes), an incredible work, which isn't about some shepherd's loves or some knight's feats, as was the trend, but about a poor man's life.

The book's biography is almost as adventurous as the protagonist's. After an initial triumph, it ended up in the list of forbidden books. A censored version was released in 1573, omitting all impious allusions to misbehaving clerics: such a critique, reminiscent of anti-clerical satires that were common in medieval fabliaux, hit differently after the 15th century, when Europe was in turmoil due to religious disputes.

— Annick Benoit & Guy Fontaine (ed), Lettres européennes: Manuel d'histoire de la littérature européenne (1992, Hachette Education)

NOTES:

* i.e. the beggar from the "rich man and Lazarus" parable, though other researchers think it's a different Lazarus, the famous one from Bethany who got resurrected; or perhaps the anonymous author didn't actually care to subvert chivalric tropes, and simply chose a random humble-sounding name

** newer research suggests that the early picaresque novels usually have protagonists and/or authors who were new Christians, i.e. of Jewish or Moorish descent: when the genre appeared, Spain had already expelled or forcibly converted all Jews and Muslims, and treated those who converted and stayed as second class citizens, so this is a distinct underclass

*** "questionable morals" because he brought her stolen food

**** image: album cover of Saurom's El Lazarillo de Tormes

#Annick Benoit#Guy Fontaine#Lazarillo de Tormes#spain#analysis#picaresque#rogues in fiction#trs#Lettres européennes: Manuel d'histoire de la littérature européenne#the Rogue school of translation gives exactly zero fucks#and quickly runs out of steam apparently

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

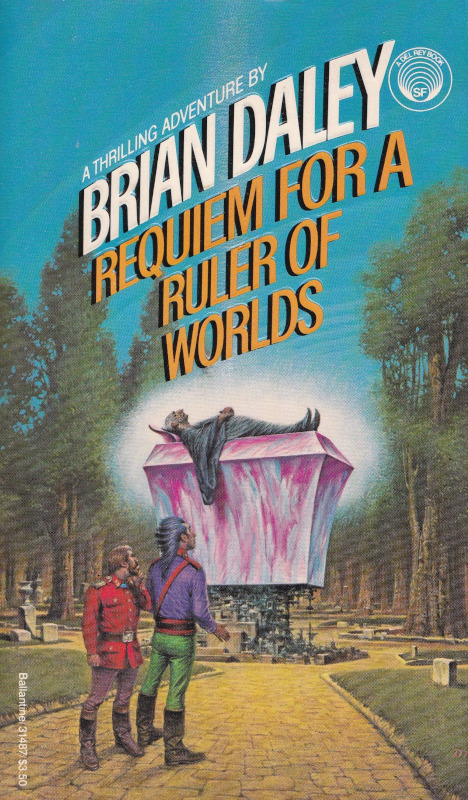

April 1985 to January 1987. One half of the pseudonymous "Jack McKinney" who wrote the prose ROBOTECH novels, Brian Daley is probably best known for his trio of delightful Han Solo novels, first published in 1979–1980, and for scripting the NPR radio adaptations of the STAR WARS movies. However, he also wrote a bunch of original sci-fi and fantasy novels, including this entertaining mid-'80s trilogy about the misadventures of Hobart Floyt and Alacrity Fitzhugh (a pseudonym, although his real name isn't revealed until the third book).

Centuries in the future, Hobart Floyt is a low-level functionary in the administrative bureaucracy of the oppressive Earth government. When he's unexpectedly named in the will of Caspahr Weir, the ruler of a minor but very wealthy interstellar empire (whom Floyt has never met), Earthservice decides Floyt must attend the reading of the will, expecting to confiscate whatever bequest he might receive. Since Floyt is a sheltered Terran who's never even contemplated going off-world, Earthservice coerces Alacrity, a young part-alien "breakabout" (starship crewman for hire), into becoming his guide. Thus begins a series of picaresque adventures through the diverse, colorful worlds beyond closed and xenophobic Earth. The first book focuses mostly on our heroes' journey to Weir's throne world, Epiphany, and the many ways they almost get killed prior to the Willreading. The second book deals with Floyt and Alacrity attempting to actually collect Floyt's inheritance — a starship to which Weir has left him title, but not actual possession — and figure out why Weir left it to him in the first place. The final volume shifts focus to Alacrity's quixotic quest to become the captain of the White Ship, a fabulously advanced starship intended to search for the secrets of an ancient alien race called the Precursors, which is also an object of fascination for Floyt and Alacrity's bitterest enemy: Dincrist, the father of the woman Alacrity falls in love with in the first book.

Anyone who enjoys Daley's Han Solo novels will probably also like these books, which are similar in tone and style: droll, action-packed romps starring two likable schmoes who spend a lot of their time running for their lives, with richly detailed settings full of exotic alien creatures and engaging if rather two-dimensional characters. These novels' literary merits are modest, but Daley's object was lighthearted pulp fiction, as evidenced by an amusingly self-reflexive subplot in the second and third books: Our heroes' friend Sintilla, a freelance journalist, starts publishing a series of extremely popular penny dreadful novels starring heavily fictionalized versions of Floyt and Alacrity (without their knowledge or approval) in wild adventures even more outrageous than their real ones. This soon makes the real Alacrity and Floyt inconveniently notorious — leavened slightly by the fact that the handsome male models depicted on Sintilla's book jackets look nothing like them!

(Ironically, this is also true of the covers of more recent editions of these books. Darrell K. Sweet's covers for the original Del Rey paperbacks, shown above, are reasonably close to how the characters are described in the text — although the gawks they're riding on the cover of the third book are all wrong — but the current versions aren't even within walking distance of the right ballpark.)

#books#brian daley#darrell k sweet#requiem for a ruler of worlds#jinx on a terran inheritance#fall of the white ship avatar#hobart floyt#alacrity fitzhugh#the han solo adventures#space opera#the gawks (which are sentient herbivores) have six legs#and resemble a cross between a giraffe and a triceratops#what sweet painted is not that#although their hide seems about right#jack mckinney

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Legend of the Condor Heroes — Heroes?

I’m doing a re-read (okay, re-listen) to the 4-book Legend of the Condor Heroes series by Jin Yong to refresh my memory before the next book, A Past Unearthed, book 1 of the Return of the Condor Heroes comes out and while it’s still holding my attention, there are a number of things that really stand out for me, but not in a good way.

First, and perhaps foremost, with so many of the so-called heroes of the Wulin, it seems that the first ‘solution’ to dealing with members of other sects is to consider killing them, or make every effort to do just that. There are instances in which powerful experts readily take to the idea that they should kill someone before they reveal a weakness, or to obtain something the other possesses.

Greed plays a pivotal role in many of the encounters. The 6th Prince of the Jin covets another’s wife and sets in motion a plan that will allow him to get her husband killed. The 9 Yin Manual is the trigger for many attempts to kill someone — Guo Jing nearly loses his life just because The Hairy Urchin thinks it will be fun to ‘tease’ Apothecary Huang about what the boy knows (does emphatically not know), and let’s not even mention Viper Ouyang’s attempts. There’s barely an honorable character in these kung fu masters.

I’m not too keen on how Huang Rong (Lotus Huang) is portrayed, especially as her first actions upon meeting the veritable country bumpkin Guo Jing is to practically bankrupt him by demanding lavish dishes when he pities the poor beggar boy. (And proceeds to waste half because they’re cold.) There are many times when her attitudes towards other people are much closer to her father’s ’Break Legs, Cut Tongues, Imprison Till I Get What I Want’ approach and seem highly incompatible with Guo Jing’s pure hearted ways of dealing with issues. She may be the smarter half that he needs to get out of situations, but honestly, I really don’t like her half the time.

As for Guo Jing, his doggedness, his loyalty, and honesty are all good for the hero of the piece, but his general thickheadedness through much of the 4 books can be a little bit daunting. Good thing he meets up with the Beggar Chief, who’s one of the few really decent men in the story.

Two other characters who I despise, one we’re supposed to, the other maybe more of a ‘picaresque’ type we’re supposed to find amusing (?) are Ouyang Ke (Gallant Ouyang) who’s a serial sex offender in his 40s with a serious and persistent lech for 15-year-old Lotus. Ick. Boulders should fall on his head! And the second is the Hairy Urchin, Zhou Botong; his childish behaviors and ��pranks’ often have disastrous results. He’s more like a bad device used so Guo Jing can pick up some helpful kung fu techniques. Can we attribute it to his long imprisonment on Peach Blossom Island?

The point of this long rant is, I suppose, to puzzle out whether these character flaws are a reflection of the times in which the novel was written, or characteristics of the genre, or characterizations that would be interesting to the original audience. Are there cultural aspects that make them more appealing? I’m curious to see where the next books take the series.

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

oh, and for a less silly question, what can you tell us about Lazarillo de Tormes?

*cracks knuckles*

Alright, so Lazarillo de Tormes is a XVI century Spanish novel and foundational piece of the picaresque genre. Its' author is unknown, but its' influence has been huge. The story is narrated by the titular protagonist, Lazaro (called Lazarillo in the Spanish style of diminutives) who hails from a village on the river Tormes. Now an adult looking back on his peculiar upbringing, Lazaro recounts his life to the reader.

A bastard born in poverty, he had a reasonably happy life with his mother until she met his step-father with whom she had another son. Lazarillo was not mistreated by these and he was happy life they shared briefly, but when it was time for him to begin an apprenticeship he knew there was no longer a place for him back home.

Thus Lazarillo falls into the service of seven masters, each embodying one of the seven deadly sins. Among these are a greedy and cruel blind beggar, a proud nobleman who refuses to admit to his socialite friends that he has gone broke, a cruel priest who starved Lazarillo (maybe the priest was greed? Or wrath, because he beats the boy fiercely...) and uh... others who escape me right now.

It's a great story with some clever writing and scathing social commentary and crittique of all of Lazaro's so called "betters". The picaresque genre it embodies is one defined by a clever and rascally underdog of a protagonist (hero hardly applies, usually) who overcomes his oppressors through wits and exploiting their flaws and hypocrises, and can be a very satisfying read.

If tempted, I'd advise you get an anotated copy of Lazarillo de Tormes. Many of the references and symbolism can be lost if you're not a XVI century Spaniard.

Thank you for coming to my TED Talk.

5 notes

·

View notes

Quote

And that's life: it does not resemble a picaresque novel in which from one chapter to the next the hero is continually being surprised by new events that have no common denominator. It resembles a composition which musicians call: a theme with variations.

Immortality | Milan Kundera

#immortality#milan kundera#quotes#quote#quotebook#books#book#read#reading#literature#litblr#quoteblr#booklr#book quotes

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

All of us tell ourselves some kind of story about our lives. Sometimes our story will weave the fragments of our experience into a greater whole, in a way that reveals relationship, connection, a clearer context. But sometimes our story is such a distorted narrative that it doesn’t serve to bear our sorrows -- instead it serves to extend them. Our theme might be the pursuit of money, sex, or prestige; it might center around love or spirituality. Some of us figure as a hero in the story, some as an anti-hero. Our story might be picaresque, romantic or tragic. We might frame ourselves as optimists or as pessimists, winners or losers. How we interpret our own experiences gives rise to the narratives to which we then usually dedicate our lives. In defiance of Isak Dineson, that narrative is often remarkably self-disparaging.

Sharon Salzberg

21 notes

·

View notes

Note

HI! For the character bingo: Kisaki, Hanma and Hinata. Have a good day :)

Hii thanks for the ask! Hope all is well~ ♥️

I love these characters so much so let's gooo~ Going in order I'll start with Kisaki:

I guess I win lol? 4 bingos 😂 I simultaneously want to hug him and aggressively shake him in a snow globe ... I guess that's what happens when you appreciate a character that has committed heinous crimes. I love a character who never says what they are thinking, what can I say... It's such fun to speculate what he's thinking on a rewatch/reread of the series!!

Next is Hanma:

Currently putting him under a microscope because we don't know enough about him and yet the Picaresque chapter permanently changed my brain chemistry. I definitely spent too much time theorizing that he was a time leaper and I wish he did more in the Final Arc... I still love to theorize what he was thinking/planning/doing in many parts of the series

Finally, Hina:

I will take so many bullets for her she deserves the world!! Why doesn't she get enough screen time??? I feel like this goes without saying but I was very unhappy with how she was discarded/ignored in the Final Arc and even on her wedding day!!! Also I thought all her similarities and parallels with Takemichi would be formally addressed sometime and she'd save the day + be called a hero but that was overly optimistic I guess. I will put her in my pocket and run away with her now

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Clint Eastwood in The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (Sergio Leone, 1966)

Cast: Clint Eastwood, Eli Wallach, Lee Van Cleef, Also Giuffrè, Luigi Pistilli, Rada Rassimov, Claudio Scarchilli, John Bartha. Screenplay: Agenore Incrocci, Furio Scarpelli, Luciano Vincenzoni, Sergio Leone. Cinematography: Tonino Delli Colli. Production design: Carlo Simi. Film editing: Eugenio Alabisi, Nino Baragli. Music: Ennio Morricone.

Clint Eastwood's Man With No Name* may be the movies' most famous picaro, the roguish hero who wanders through an often hostile landscape, surviving by his wits -- and in this case, his skill as a gunman. The picaro's heart is generally in the right place even if he doesn't mind breaking a few laws to get his way. In the first two films of Sergio Leone's "Dollars Trilogy," A Fistful of Dollars (1964) and For a Few Dollars More (1965), he is a loner, but in The Good, the Bad and the Ugly he has picked up an unlikely (and untrustworthy) sidekick in Tuco (Eli Wallach), with whom he is working a scam: Tuco has a price on his head, which our hero collects by bringing Tuco in to justice, and then splits with Tuco after rescuing him from a hanging. Tuco is a more vicious Sancho Panza to No Name's more capable Don Quixote. Leone himself once admitted his debt to the picaresque tradition, and The Good.... was filmed in Spain, where the tradition began with Lazarillo de Tormes in 1557 and produced its most influential analog in Don Quixote. But who, in the mid-1960s, when Leone was making movies derided as "spaghetti Westerns," would have anticipated such analysis or the veneration those films receive today? Half a century ago, when Leone's trilogy was being released, critics were raving about films like A Man for All Seasons (Fred Zinnemann, 1966), Doctor Zhivago (David Lean, 1965), and Becket (Peter Glenville, 1964): "prestige" movies on high-toned subjects that have dated badly, while Leone's movies still get enthusiastic viewings. The Good.... is overlong, especially in its latest restoration, which runs for 177 minutes, and there's some confusion in integrating the Civil War's New Mexico Campaign scenes with the story of the titular triad. But there are few scenes in movies more dazzling than Tuco's dash through the cemetery and the subsequent three-way standoff. Lee Van Cleef is a suitably scary Bad guy; Eastwood demonstrates the growth as an actor that would continue as his career soared; Wallach gives one of his best performances: and the contribution of Ennio Morricone is breathtaking. Raw and unpolished as The Good, the Bad and the Ugly at times is, it remains memorable filmmaking, while the films more celebrated in its day are mostly forgettable. *Actually, he picks up a name in each of Leone's "Dollars Trilogy" films: In A Fistful of Dollars he is called "Joe," which is a generic name for an americano. In For a Few Dollars More he is known as Monco, the Italian word for "one-armed," in reference to his tendency to use his left hand while keeping his gun hand under his poncho. And in the third film he is dubbed "Blondie" by Tuco. (The color of Eastwood's hair seems to me like a minor characteristic, but "Tall Guy Who Squints and Smokes Cheroots" would have been a mouthful.)

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Russell Letson Reviews Lords of Uncreation by Adrian Tchaikovsky

October 5, 2023 Russell Letson

Lords of Uncreation is the third entry in Adrian Tchaikovsky’s Final Architecture sequence that began with Shards of Earth and Eyes of the Void, which introduced a menagerie of alien civilizations living and dead, allies and opponents of all species, and a galactic history of interstellar warfare, ruined worlds, and refugees on the run from inscrutable, unstoppable planet-killers. Which means the series is probably best seen as space opera, but with any number of extensions bolted onto that sturdy chassis. The result is a three-ring-circus extravaganza, juggling flaming chainsaws, kittens, and Fabergé eggs while pedaling a unicycle backwards across a pool of hungry crocodiles.

The books combine the cosmic vision of Olaf Stapledon and the cosmic horror of H.P. Lovecraft (or William Hope Hodgson), plus cross-cultural encounters, and adventures of the military and picaresque kind, along with other items from the Big Box of Narrative Components. But then, this is the omnivorous SF category we’ve come to call New Space Opera, a fictional environment encompassing deep galactic history, vanished civilizations, enigmatic aliens, metaphysical mysteries, world-saving (or destroying) McGuffins, monstrous monsters, gigantic battles, titanic devices (infernal and miraculous), and posthuman/nonhuman heroes and villains. Among other items of interest and amazement.

That Lovecraftian vibe is foregrounded in this climactic volume, though it has played a significant part from the beginning. Interstellar travel through ‘‘unspace’’ is so harrowing that it can drive travelers to suicide, thanks to the travelers’ sense that they are alone with a horrid, unseen, hostile presence, so everyone except Intermediaries (extensively and painfully altered navigators) travels sedated. And from unspace emerge the Architects, gigantic, relentless entities that reshape inhabited worlds into planet-size sculptural constructions. The first two volumes establish and elaborate the ways that a multispecies alliance (in which humankind is a junior but not insignificant member) manages to push back against the Architects. But ‘‘push back’’ is not the same as ‘‘defeat’’ or ‘‘eliminate,’’ and in Lords of Uncreation the Architects are back, and the allies must decide how to locate and stop the power behind them.

A partial list of the allied forces includes the genetically engineered, all female, human-based Parthenon military culture; the Council of Human Interests (the ‘‘Hugh,’’ remnant of the much-diminished human interstellar polity); the crab-like Hannilambra; the collective-AI-mind Hivers (former tools of humankind, now independent); and the powerful and once Architect-proof multi-species Essiel Hegemony, which behaves like a cross between an empire and a religious cult.

The viewpoint characters caught up in these plot machineries include survivors of the earlier books’ exertions, including the remnants of the crew of the salvage vessel Vulture God: the physically incomplete but extensively technologically enhanced engineer Olli; the business agent-lawyer-duellist Kris; the long-instantiated Hiver AI-swarm Medvig. At the center of everything remains the unusual pairing of the independent Intermediary Idris Telemmier, who can navigate unspace awake and bare-brained and communicate with Architects; and his one-time comrade-in-arms, the Partheni soldier Solace, who feels the strain of competing loyalties to her military society and her old friend. Also returning are the caught-in-the-middle Hugh intelligence agent Havaer Mundy; some extravagantly arrogant and persistent aristocratic human bullies; and the wonderfully named, nightmarish Essiel criminal and ‘‘rebel angel’’ The Unspeakable Aklu, the Razor and the Hook, along with one of its more durable (in fact, nearly indestructible) minions.

With multiple viewpoint characters and story lines to follow (and the ever-present threat of Spoiling), even a skeletal plot summary is going to strain at the limits of this column. I can report, however, that the occasionally comic episodic-adventure feeling of the first two volumes has shifted to something darker and more desperate as the new wave of Architects turn their attentions even onto the previously immune Essiel. Old alliances are strained almost to the breaking point, and long-running tensions among competing and cooperating powers generate not only diverging notions of how to combat the Architects but whether to do so at all. One group is planning on gigantic ark-ships on which to preserve a selection of humanity (with themselves at the top of the pyramid, of course), while both the Hugh and the Parthenon hierarchy harbor restless plotters with their own agendas. Accordingly, the story line is rich with plots and counterplots, betrayals and backstabbings, realignments of loyalty, and enough big special-effects set pieces to justify the ‘‘opera’’ part of the genre label.

In the spirit of movie trailers, though, there are snippets that give the flavor of this big, complex story. When, for example, the Architects move from mere planetary reconfiguration to using their infantry-equivalent forces, whose horrors are decidedly up-close physical:

a half a dozen other appendages peeled the portal back…. What came through first was something like a woodlouse, its raised underside all gleaming killer cutlery. Behind it stalked an absurdly delicate thing on spindly gazelle legs, its head a flower of teeth.

We see quite a bit more of the Essiel, who finally condescend to offer cooperation of a sort in the shape of The Uspeakable Aklu and his ship and minions. Olli (herself dependent on a range of prosthetic appendages) is partnered with one of the Essiel’s half-human, half-alien-symbiote assassin-agents and becomes, effectively, part of the Unspeakable’s organization–and finds it oddly fitting.

Aklu was her monster…. Something about the Razor and the Hook’s life in defiance of the [Essiel] Hegemony spoke to the rebel inside her that had never agreed to live with her inbuilt limitations.

Which leaves Idris at the center of a new team of oddballs and revenge-obsessed scientists, hoping to find a way to penetrate unspace and confront the powers behind all the destruction rising from its undepths. Frodo-like in his fragility and determination, he continues his desperate, draining efforts to get to the ‘‘kraken,’’ the enemy at the (metaphorical) bottom of unspace, toward a Lovecraftian moment.

It uncoiled. Vast, sightless, lazy. Its unreal tentacles reaching up through the lightless abyss to touch him…. He felt himself in the very shadow of the Presence, sneaking past the limitless expanse of its leathery flank. And beyond it, beneath it…. The abyss gazed back at him.

The combination of space operatics, horrors nameless and all-too-physical, alien cultural encounters, eye-crossing intrigues, serviceable villains, desperate heroics, durable loyalties, and strange but satisfying transformations makes for a complex, exhilarating ride. Save the kittens, and watch out for the crocodiles.

1 note

·

View note

Text

By Barrett Brown; MCD, 416 pages, $30.

His talents in full flower and basking in public admiration, gonzo journalist and inveterate anti-establishment troublemaker Barrett Brown is jailed in his native Texas on various federal felony charges.

It is 2013, and Brown’s adventures have included helping anonymous hacktivists publicly expose private U.S. intelligence contractors engaged in deep-state power abuses.

Brown has done this in swashbuckling style — often in a drug- altered state, chatting with executives whose hacked emails have been dumped online while on opiate maintenance medication.

Brown was in withdrawal from antidepressants and opioids, he would later testify, when he threatened an FBI agent in a video posted to YouTube.

“I wanted to become famous for overthrowing things,” Brown writes in his memoir, “My Glorious Defeats: Hacktivist, Narcissist, Anonymous.”

Mainstream press coverage at the time of Brown’s prosecution was uneven, and sometimes just plain inaccurate.

Beyond seeking to set the record straight, the book snapshots a pivotal moment in online activism and pulls no punches.

Brown is a showman, a gifted writer in the tradition of William Burroughs and Hunter S. Thompson.

He also has a knack for self-sabotage and has struggled with heroin addiction and depression.

He is currently in Britain engaged in a legal struggle for political asylum.

A self-described “anarchist revolutionary with a lust for insurgency,” Brown became a cause celebre of press freedom champions a decade ago, a hero of stick-it-to-the-man radicals.

But this is far from a happily-ever-after story.

Having alienated many who once held him in high esteem, Brown attempted suicide in 2022, alerting the world on Twitter.

The memoir’s last chapter was difficult to pen.

“I was deeply wounded by much of what I discovered about the last decade when it became my job to see all this completely and accurately,” he writes. —

This Hacker’s Story Is Deranged, Hyperbolic and True

In his picaresque memoir, “My Glorious Defeats,” the Anonymous-movement activist Barrett Brown takes us on a journey of pure, joyous solipsism.

July 12, 2024

The image portrays the author, Barrett Brown, dressed in a black coat and jeans, standing on stairs surrounded by protesters holding signs.

Barrett Brown describes the movement Anonymous as a “machine that focused attention” on social problems.

MY GLORIOUS DEFEATS: Hacktivist, Narcissist, Anonymous: A Memoir, by Barrett Brown

When readers express a desire for “truth” in memoir, they generally mean they want it only to include the falsehoods we have collectively agreed to accept — the stability of memory, of personhood, of childhood dialogue perfectly recalled.

Memoirists, striving toward this view of truth, often neglect the literary demands of self-characterization.

One needn’t build a character; one is simply oneself, however shrouded in self-delusion.

This is decidedly not the situation we find ourselves in with Barrett Brown’s extraordinary new book, “My Glorious Defeats: Hacktivist, Narcissist, Anonymous.”

Brown is an activist associated with the hacker group Anonymous, and a political prisoner recently denied asylum in Britain, all of which sounds a bit dreary until we hear tell of it through Brown’s unhinged self-regard.

“The institution of bed-makery was among the first clues I’d encountered as a child that the society I’d been born into was a haphazard and psychotic thing against which I must wage eternal war,” he writes early on.

“There was no reason, and could be none, that a set of sheets must be ritually configured each morning before the affairs of man can truly begin.”

A “machine” that focuses attention on little-known social issues, Anonymous has gone after the Church of Scientology, Koch Industries, websites hosting child pornography and the Westboro Baptist Church.

The public tends to be confused by nebulous digital activities, so it was, in the collective’s heyday, helpful to have Brown act as a translator between the hackers and mainstream journalists.

“The year 2011 ended as it began,” he writes, “with a sophisticated hack on a state-affiliated corporation that ostensibly dealt in straightforward security and analysis while secretly engaging in black ops campaigns against activists who’d proven troublesome to powerful clients.”

This particular corporation was Stratfor, a company that spied on activists for the government.

Shortly after the attack, the F.B.I. showed up at Brown’s mother’s house, where he was, and asked whether he had laptops to surrender.

He declined;

his mother hid his laptop on top of some pans in a kitchen cabinet.

The F.B.I. returned, just before Brown was scheduled to appear on CNN, and dozens of agents searched the house.

His mother cried.

Brown waited for the feds to come back and drag him to jail.

He also says he tried to get off suboxone in order to avoid the painful possibility of prison withdrawal, and stopped taking Paxil, inducing a manic state, all of which is given as explanation for his regrettable next move, which was to set up a camera and start talking.

The feds had threatened his mother, he told the internet, and in response he was threatening Robert Smith, the lead agent on his case.

youtube

He found himself in custody the same night.

Brown was then subjected to the kind of nonsense the Department of Justice is prone to inflicting on those involved in shadowy internet activities that, in fact, almost no one in the legal process understands.

He was charged with participating in the hack of Stratfor, though he was not really involved and cannot code, and although the whole thing was organized by an F.B.I. informant.

Brown had also retweeted a Fox News host’s call to murder Julian Assange;

the prosecution presented this as if he were himself calling for the murder of Assange.

But generally, Brown’s primary victim is himself.

“My thirst for glory and hatred for the state,” he writes, “were incompatible with an orthodox criminal defense, in which the limiting of one’s sentence is the sole objective.”

In his cell, with an eraser-less pencil he needs a compliant guard to repeatedly sharpen, he writes “The Barrett Brown Review of Arts and Letters and Jail.”

His mother types it up; The Intercept publishes.

He develops the character he will play in his memoir: a self-aware narcissist and addict.

He wins a National Magazine Award, and is especially pleased that his column “Please Stop Sending Me Jonathan Franzen Novels,” wins while Franzen is in attendance.

While Brown is in jail reading letters from the kinds of people who write to people in jail, things go awry.

“Donald Trump was about to take office, having been elected president with the assistance of my chief enemy, Palantir founder Peter Thiel, and my chief ally, Julian Assange.”

Brown breaks with Assange, and loses associates.

Many, many people disappoint him.

A member of Anonymous reveals himself to be a Nazi.

After Brown is released, The Intercept announces that it is closing down the Snowden archive, and Brown burns his National Magazine Award certificate in protest.

The reader may be forgiven for losing the thread.

This is a book in which the stakes are both incredibly high (a state throws you into prison) and very low (a “Hobbity-looking” fellow writes a piece you don’t like in Gizmodo).

Brown’s looping, musical sentences are flirtations, bending reason toward satire, hovering always on the fine edge between absurdity and profundity, as if Thomas De Quincey (another fan of opium-derived compounds) had taken upon himself the problems of the post-9/11 military-industrial complex.

The state is an afterthought here — a litany of absurdist horrors too stupid to appall.

Of course Brown would be denied his constitutional right to a lawyer after a thin-skinned prison official decided to punish him for talking to a journalist.

Of course Brown, newly released from prison, would find himself holding a “Cops Kill” sign that somehow gets rearranged to “Kill Cops” such that he is once again incarcerated.

Brown plays up the impetuous narcissism for comedic effect, but how many revolutionaries, softened by history into noble bores, were precisely the self-promoting, self-centering semi-narcissists their societies needed at the time?

We’re left with a man who refuses to look away from the deep structure of the world, an unstable position from which there is no sanctuary.

“My Glorious Defeats” is deranged, hyperbolic and as true a work as I have read in a very long time.

MY GLORIOUS DEFEATS: Hacktivist, Narcissist, Anonymous: A Memoir | By Barrett Brown | MCDxFSG | 402 pp. | $30

Summer 2014

The old brick building to which we were being led had served as an internment center for German nationals during World War II.

Now it mostly held Americans.

I wondered briefly whether I should write this down the next time I managed to get hold of a pencil.

There were eight of us being escorted across the compound of Federal Correctional Institution Seagoville, which had been put on lockdown as a result of our actions;

prison inmates, confined to whatever building they’d happened to be in when the incident began, stared at us through the windows.

I’d never seen the yard before, having spent the preceding months in the prison’s jail unit along with others who were awaiting trial or sentencing or transfer.

Our own building had been modern, purpose-built for incarceration, and we never really saw it from the outside.

Out here, on the other side of the tall barbed-wire fence that bisected the compound and divided the jail from the prison proper, the whole place had the look of a college campus—albeit a third-rate college in a second-tier state, never producing any really successful graduates who might be inclined to write an endowment check.

When we arrived at the brick metaphor for American decline, situated at the other end of the yard from the jail unit that had lately made up my universe, we were taken through the main door and then down a stairwell to the receiving area, where we were divided into pairs.

As our turn came, two of us were placed in one of the holding cells at the foot of the stairs.

The cell gate was locked behind us, and my companion and I took turns backing up to the bars so that the guards could remove our handcuffs through a little rectangular gap.

“What’s got you so mad, white boy?” an intake guard asked me.

I declined to respond.

I wasn’t mad anymore; the regret had already begun to set in.

Also the guard himself was white, which I found confusing.

We stripped and threw out our jail uniforms.

In exchange we were handed bright yellow spandex pants, flimsy boxer shorts, white T-shirts, and blue slip-on shoes, and then left to wait.

The corridor was made of concrete.

All the light came from naked bulbs.

There was a light switch in the cell, and I turned it on.

“Leave it dark,” drawled my companion. “That bulb’s gonna make it hotter.”

“We’re gonna have to get used to that,” I retorted.

“Oh, that’s right!”

He said this with great cheerfulness, and I liked him for it.

I’d barely known him back in the unit, where we’d played chess a couple of times.

Now we would be living together for twenty-three to twenty-four hours a day in a small concrete room for at least a month or two over the course of a Texas summer, with no air-conditioning and little to occupy our time.

He had already accepted this.

I hadn’t.

The adrenaline rush I always get from confrontations with unjust authority had played itself out, and now I regretted the loss of my books, the spacious corner cell I’d shared with the old Vietnam vet, my phone calls, my little radio.

I’d been held in the Special Housing Unit once before, upon arriving at another prison, but only for a few days while I waited for space to open up in the jail unit.

That time, I’d been able to bring books into the hole, along with paper and pens.

Now I had nothing.

And so I went over the events of the last few hours, wondering if it had been worth it and deciding that it hadn’t.

Nothing had really been accomplished by what we’d done; the elderly man we’d been trying to defend had been brought to the SHU along with us, which was the very outcome we’d set out to prevent.

Probably he’d be in more trouble now.

And I wouldn’t have any coffee for days and days and days.

My new friend and I were cuffed back up and taken to a cell about halfway down the corridor.

The door was already open; we walked in; the door was closed and locked; we backed up against it to be uncuffed through the rectangular slot located at hip level, which was then closed and locked from the outside.

We dropped our blankets on our mattresses and appraised our quarters.

The bulk of it was taken up by the bunk bed, a stainless-steel sink-and-toilet unit, and a metal desk affixed to the wall.

A window with a tightly laced metal grille sat in the wall opposite the door; it had a rotating lever that could be used to draw the glass in, which I knew to be an unusual feature, representative of the more easygoing approach to prison design that marked mid-twentieth-century facilities.

The window looked out upon a courtyard, and a tree.

Regret gnawed upon my soul, as it does each time it occurs to me that my past self has sold out my present self, depriving him of later comfort in exchange for momentary satisfaction.

Previously this had taken the form of heroin addiction.

Now it was the impulse to defy authority without clear strategic advantage.

“Is that you, Brown?!” someone shouted from down the hall.

I went back to the steel door, which featured a metal lattice grille over a rectangular gap, situated vertically and at face level, two feet above the horizontal chute.

I pressed my cheek against the grille and shouted out confirmation that I was myself and could be no other.

“I’ll send you some coffee tonight! You’re awesome, Brown!”

It was a Hispanic fellow I’d vaguely known from the jail unit, where newspaper and magazine articles about my adventures on the outside had circulated for some time before my arrival.

Now he was offering tribute.

Julian the Apostate, raised to Caesar but not yet Augustus, and wavering in the face of necessary civil war, must have been likewise affected when a Gaulic auxiliary shouted out from the ranks that he must follow his star.

Even Emma Goldman had had her moment of doubt and pain, only to be rallied back to her natural strength through the stray words of some admiring fellow prisoner.

I had no idea how this fellow proposed to give me coffee from his cell down the corridor, but that was rather secondary.

For was it not I myself who had decided, from adolescence on, that there could be no middle ground?

Had I not filled teenage journals with inane yet consistent juvenilia to the effect that I would be Caesar or nothing?

Had I not since taken a thousand conscious steps away from the sordid path of the postwar Westerner, in revolt against the passive mediocrity of our age?

Had I not pledged myself to the life of the revolutionary adventurer, and to the unfinished work of the Enlightenment?

Each of the great men who had formed my psychological pantheon from childhood on had suffered for his efforts.

And the road to the palace often winds through the prison.

Yes, I had been cast into the crevasse.

So had any number of those giants who once roamed the earth; they emerged, cast now in bronze.

But it wasn’t the example of my personal deities that drove me on.

There are lives, and fragments of lives, that we may look to for direction as the faithful look to saints.

Two girls, as later reported by Solzhenitsyn, were held in an early Soviet prison where talking was forbidden; they sang songs on the subject of lilacs, and continued singing as guards pulled them down the hall by their hair.

These accounts merely shame me, as they should shame you.

But shame is not sufficient groundwork for the things that I would have to do if I were to prevail in a cause that was not only just but entirely compatible with my own eternal cause, which is me.

Duty is enough for some.

I require glory.

And now I saw the way forward, once again.

Yes, I was in the crevasse.

But my soft power, cultivated over several high-stakes years, extended even here, in the form of an inmate’s deference.

Someday it would extend everywhere and take other forms.

I had miscalculated today.

But I’d miscalculated before while still managing to make many such failures the foundation of some future victory.

This situation, too, could be turned to my ultimate advantage.

And if the guards dragged me down the hall by the hair, I would take the opportunity to sing my own praises.

That night, a guard came by, opened the chute, and passed through a blank envelope.

It was sealed.

I opened it.

It was filled with instant coffee.

One is awoken by the clang of the metal door slot as it’s unlocked and falls into its resting position.

A breakfast tray is slid onto the now-horizontal slot, to be taken up by one of the inmates and replaced by a second tray, which is also taken up, followed by four plastic bags of milk and two apples or bananas or, if you’re unlucky, pears.

As long as the guard is there, one might ask him to hit the light switch that sits outside one’s door.

It’s about 5:30 a.m.

They return after some ten or fifteen minutes to take back up the trays, and, if it’s a weekday, to ask who wants to go outside for their allotted hour of recreation later that morning.

They must know this in advance so that the duty officer can plan things such that incompatible inmates who may be inclined to attack each other on sight aren’t placed in the same recreation cage.

I already knew all these basics from my original three-day stint in the hole at the Fort Worth Federal Correctional Institution, which, like all institutions run by the Bureau of Prisons, operates under a series of program statements composed out of the national office and officially applicable to federal facilities from California to Maine.

But rules have no importance in a country such as ours.

It’s quite enough to know the whims of those they’ve placed in charge.

“Get that cup off my windowsill!” shouted some sort of fascist.

I stood up and glanced through the door grate. It was a pig I’d never seen before.

His name tag read Mack.

He was in charge here.

After I removed the offending foam cup from the fascist’s windowsill, he explained to me, in somewhat less aggressive tones, that no objects must be placed on the windowsill, which was his.

The Ballad of Barrett Brown

He was a “preppy anarchist” who went to jail for his fight against the surveillance state. Was it all for nothing?

Barrett Brown spends much of his day on an exercise ball in a small bedroom he shares with his fiancée, Sylvia Mann, and a parrot named Esteban.

Freed from his cage, Esteban flaps across the room, his green wings gusting open books and causing visitors to duck their heads.

Brown sings to him and offers a peanut.

Mann enters and the parrot zips over to her, nestling his beak into her collarbone.

She edits the radical journal Freedom, is involved in London leftist protest politics, and tends to bring home creatures of mysterious provenance.

My arrival in December at their house in Bournemouth, on England’s southern coast, was preceded by that of some small turtles, which rested in the bathtub for a few days before being spirited elsewhere.

“My girlfriend is an ecoterrorist,” Brown says, laughing but not joking.

The couple lives with Mann’s mother; a mellow Alsatian; a black-tufted, jacket-wearing cat; another parrot; and four human lodgers: a Ph.D. student from Beirut, who arrived as an Airbnb guest years earlier and never left, and a Czech activist, plus their partners.

In winter, Bournemouth is a dreary town, quiet compared with its summer high season, and the house, filled with a catholic mix of books and artwork and this human-animal family, has a tumbledown feel.

It wasn’t supposed to turn out this way for Brown, an “unapologetic seeker of fame and glory,” as he describes himself.

There were people to save, governments to overthrow, hegemonies to dismantle.

Yet here he is, drying out in a country he admits he can’t stand.

As we sit on his bed chatting, he pops a Suboxone pill; he’s off heroin, he says.

He vapes tobacco from a Heet device, a smooth oval of aquamarine plastic that he fiddles with between puffs, and reaches for a glass of red wine.

A former “preppy anarchist” — blazer, dress shirt, bottomless contempt for authority — Brown, 42, now looks tired, his face slouching toward hangdog.

Once a gregarious social presence, he doesn’t stray far from his English burrow.

“I’ve got plenty to contemplate,” he says. “And a lot of it is hard for people to relate to.”

He has few regrets and a lifetime of enemies.

As a one-time associate of the hacktivist group Anonymous who went to prison for four years for his efforts to expose what he has called the “cyber-intelligence complex,” he has many erstwhile friends and colleagues who support the cause but not the man.

They praise Brown’s writing, for which he once won a coveted National Magazine Award, and practically smile through the phone when recalling his knack for finding interesting people to collaborate with on investigations — everyone from filmmakers and journalists to sex workers and hackers.

“Barrett brought a lot of people together,” says Gregg Housh, an activist and a core Anonymous participant who was close with him.

Roger Hodge, his editor at The Intercept before Brown pulled his column, says, “The columns were wonderful. I would read them aloud to the newsroom.”

Some of these people speak of their desire to reconcile but don’t want to go on record for fear of antagonizing him.

Others dismiss Brown as a paranoid junkie riding political persecution and old glories — helping Tunisian activists topple their government, uncovering a dirty-tricks program that private-intelligence contractors used to discredit WikiLeaks, and generally playing David to the American empire’s Goliath — past their sell-by dates.

“Some of Barrett’s behavior is a result of addiction, paranoia, PTSD and not enough postprison support, but systemic contributing factors don’t excuse a pattern of behavior,” says Emma Best, a member of the whistleblower group DDoSecrets who worked with Brown on 29 Leaks, an archive of communications from a London “company mill” that registered more than 450,000 shell companies in various tax havens.

“Especially not when there’s no real acceptance of responsibility, no making amends.”

Brown isn’t particularly interested in making amends at the moment.

He has a memoir, My Glorious Defeats: Hacktivist, Narcissist, Anonymous, coming out from FSG in July, but he’s mostly reading and gaming while waiting to hear about his quixotic bid for political asylum in the United Kingdom, which he feels is the only way to protect himself from the long, vindictive reach of the U.S. government.

“A lot of people who could have used a path like this are already dead,” he tells me, a grim summation of the fate of a whole generation of radical hacker-activists who, like him, rose to prominence in the age of Edward Snowden and Julian Assange and once seemed on the brink of changing the world.

Now, what may be called the “transparency movement” — the unofficial confederation of government whistleblowers, digital-rights organizations, free-speech lawyers, leakers, and mercurial trolls in Guy Fawkes masks — is in tatters, undone by FBI infiltration, public indifference, wanton self-destruction, and the sheer folly of taking on an enemy with limitless power.

After publishing his book, which reads as one last cri de coeur against the monstrous union of corporate and state power squelching dissent and empowering fascism, Brown wants out. “I’ll leave them alone, and they’ll leave me alone,” he says, “and then I can live out my days just in quiet.”

Growing up in Dallas in the 1980s and ’90s, Brown was a precocious writing talent, becoming his school’s poet laureate and winning essay contests, but his young life was defined by an almost pathological resistance to authority and by the roguish example of his father, Robert Brown.

“I come from southern-gothic dirt,” Brown tells me.

When Barrett was in elementary school, Robert was charged in a real-estate-fraud scheme, but the charges were eventually dropped.

At age 17, losing interest in high school (and his school losing patience with him), Barrett learned some Swahili and moved with his father to Tanzania, where the elder Brown had gotten a concession to harvest a certain wood coveted by high-end furniture-makers.

But the project went south and father and son beat a swift retreat back to Texas.

After his mom kicked him out, Barrett bummed around with his ne’er-do-well dad.

In his memoir, Brown recalls “days spent moving office furniture for some bizarre enterprise disguised as a Pentecostal church or editing investor letters in support of some real-estate deal that would invariably fail, nights spent writing and querying and submitting, my motivation rekindled by pure terror.”

Brown describes himself as a drug addict “since early adolescence.”

Ritalin led to suicidal ideation, which led to Zoloft, “which allowed me to function like a regular person and even renewed my interest in other human beings,” he writes.

He moved to Brooklyn to write and discovered heroin.

Somehow, he managed to carve out a freelance career and co-author a satirical book mocking proponents of creationism.

(Alan Dershowitz contributed an admiring blurb.)

He gave a talk at Rutgers after a night of smoking crack and showed up high at the offices of the New York Observer.

His work started to dovetail with other obsessions.

Smart, prankish, and fuming at injustice, Brown came up through online forums and chat rooms that valued irreverence as much as anonymity.

People were starting to use a combination of humor, trolling, denial-of-service attacks, and hack-and-leak operations in the service of anti-authoritarian and left-wing causes.

In 2010, Chelsea Manning leaked classified materials to WikiLeaks exposing the brutal violence of the war on terror, including a video of a U.S. helicopter firing on and killing Reuters staffers.

That same year, a 29-year-old Brown joined one of the Internet Relay Chat servers of Anonymous, then a volatile petri dish where these new forms of resistance were being cultivated.

Some Anonymous operations were little more than harassment, but over time they took on more deserving targets, starting with the Church of Scientology in 2008.

As part of Project Chanology, Anonymous-affiliated hackers broke into Scientology computer systems and leaked church materials.

They launched denial-of-service attacks and tied up church phone and fax lines.

Beginning in February 2008, Anonymous helped inspire masked protests outside Scientology buildings in dozens of cities around the world, while a church video of Tom Cruise extolling the special powers of Scientologists went viral.

“Anonymous was a machine that focused attention — a sort of spotlight that could be turned toward whatever needed to be exposed, and attacked,” Brown writes.

During the Arab Spring, Anonymous launched denial-of-service attacks against Tunisian government websites as part of Operation Tunisia.

Brown helped create a manual for would-be revolutionaries to document government atrocities, mitigate the effects of tear gas, and block streets with debris.

“The Anonymous Guide to Protecting the North African Revolutions” was translated into French and Tunisian Arabic and distributed in local coffee shops.

As their compatriots stormed the streets, Tunisian anons hacked police computer systems and promised more cyberattacks until the government expanded civil liberties.

Among these activists was Slim Amamou, a Tunisian anon who eventually became his country’s youth and sports minister in the postrevolutionary government.

With a small assist from Anonymous, some guy Brown knew only as slim404 in an IRC chat helped overthrow a regime and then form a provisional one.

The moment was freighted with a profound sense of revolutionary possibility.

In its ability to combine cyberattacks with on-the-ground protest while generating viral interest and mainstream-media coverage, Anonymous was practicing a new kind of digitally infused activism that would be adapted by various political actors in the coming years.

Brown’s work brought him into contact with many of the transparency movement’s leading lights.

With Aaron Swartz, Brown investigated “persona management” programs that they said would allow government agencies to operate hordes of fake identities on social platforms;

this was years before “bots” became the subject of public concern.

With national-security reporter Michael Hastings, he developed a pipeline into mainstream media, helping get Anonymous stories in front of readers of publications like BuzzFeed.

“He had a curiosity in what people were doing,” says Maggie Mayhem, an activist for sex-worker rights and reproductive justice.

“He was able to curate just a fascinating network of people.”

In interviews, Brown was sometimes identified (erroneously, he says) as an Anonymous spokesman or a hacker himself, which put him in the crosshairs of a Justice Department that was beginning to take hacktivists seriously.

In March 2012, the FBI raided Brown’s mother’s home in Dallas.

She was charged with obstruction of justice for putting two of her son’s laptops in a kitchen cabinet.

(She pleaded guilty to a lesser charge of obstructing a search warrant.)

Brown lost it.

Giddy with fury (and possibly in withdrawal from antidepressants and Suboxone), he posted videos threatening to “ruin” the life of an FBI agent who was investigating him.

The FBI said Brown went further, claiming (falsely, according to him) he had promised violence, and arrested him the next day while he was on a video stream with several associates.

Brown was charged with making internet threats and intending to publish “restricted personal information” about a federal employee.

The government eventually added other charges in connection with an Anonymous offshoot’s 2011 hack of Stratfor, a private-intelligence firm.

Brown didn’t participate in the Stratfor hack — he didn’t even know how to code.

(In fact, the attack was directed by a hacker named Sabu who turned out to be an FBI informant working on a government-provisioned laptop.)

In an Anonymous IRC chat, someone posted a link to a zip file of pilfered Stratfor data.

Brown copied the link and shared it in a group chat he maintained with other journalists and activists.

He didn’t know what was in the archive, and it had already been posted online, but it contained Stratfor customer credit-card numbers.

For sharing the link, Brown was initially charged with 11 counts of aggravated identity theft and another of “access device fraud.”

(Federal prosecutors later dropped the identity-theft charges.)

Brown spent 26 months in pretrial detention dealing with innumerable hearings, legal filings, fundraising challenges, prison transfers, unstable inmates, and power-hungry guards.

He received a firsthand education in how the legal process is skewed against defendants.

“It became clear that, going to trial, I would lose, regardless of what the facts are,” he says.

“Sometimes you have to give them a win when you have a sense of how terrible they are.”

Facing a possible prison sentence of 105 years, he pleaded guilty to reduced charges and was incarcerated for four years in total.

(He was also ordered to pay $890,000 in restitution.)

“The main sticking point was I would not plead guilty to anything involving fraud,” he says, which he calls a “moral crime.”

“I have no problem admitting to an absurd crime,” Brown says.

“My job was not to stay out of jail. It was to cause severe damage to this industry,” by which he means the private-intelligence industry.

Brown did not treat prison as a setback.

“We had these huge victories,” he says.

His brand of accountability activism was bleeding into the mainstream — it still seemed like a viable path to provoking a response from moldering institutions and an apathetic public.

Hastings had published accounts of General Stanley McChrystal, the head of the U.S. armed forces in Afghanistan, mouthing off to White House and other government officials, leading to McChrystal’s ouster (the general later apologized).

Snowden, their contemporary, had shared NSA secrets with Glenn Greenwald, Laura Poitras, and other reporters, igniting a global debate about mass surveillance.

The culture was starting to bend toward Brown’s views.

Perhaps jail would just be a blip.

He went in expressing a satirical optimism.

“For the next 35 months, I’ll be provided with free food, clothes, and housing as I seek to expose wrongdoing by Bureau of Prisons officials and staff and otherwise report on news and culture in the world’s greatest prison system,” he said in an announcement.

In his memoir, he expresses his longtime admiration for Abbé Faria, a “convict-monk” in The Count of Monte Cristo who tells Edmond Dantès about how prison allowed him to develop his mind.

“Dantès wonders aloud how much else this sage would have accomplished had he been a free man,” Brown writes. “The Abbé retorts that he would have accomplished very little.”

Brown certainly developed his mind, reading hundreds of books.

He also wrote biting, insouciant columns for The Intercept under the heading of “The Barrett Brown Review of Arts and Letters and Prison.”

Brown wrote some of his pieces with pencil and paper and mailed them to his mother, who typed them up for Hodge.

They were slashing works of satire that read as if written by candlelight, the midnight musings of a droll Texan who “lives in a prison.”

Among the most memorable was Brown’s meta-review of Jonathan Franzen’s novel Purity, which featured an anti-hero resembling Assange.

Brown, whose literary tastes mostly ended at the 19th century, wasn’t impressed.

“I was interested enough in WikiLeaks, state transparency, and emergent opposition networks to do five years in prison over such things,” he wrote, “but I wasn’t interested enough that I would have voluntarily plowed through 500 pages of badly plotted failed-marriage razzmatazz by an author who’s long past his expiration date simply in order to learn what the Great King of the Honkies thinks about all this.”

Brown’s writing can be great insult comedy — your most savage friend cracking you up at the bar — but it’s in service to a cause.

This review finished with the kind of sweeping indictment that showed Brown at his best:

“We live in a sort of silly cultural hell where the columns are composed by Thomas Friedman, the novels are written by Jonathan Franzen, the debate is framed by CNN, and the fact-checking is done by no one. Franzen’s nightmare — a new regime of technology and information activists that will challenge the senile culture of which he is so perfectly representative — is exactly what is needed.”

Brown didn’t learn he had won a National Magazine Award until he was released from one of several periods of what amounted to solitary confinement.

(He had passed the time reading Robert Caro’s multivolume Lyndon Johnson biography.)

Hodge, who this month left The Intercept, says he had hoped to hire Brown full time after his prison release.

It didn’t turn out that way.

Jailed since 2012 for his investigations, #BarrettBrown has finally been released from prison,” tweeted Snowden on November 29, 2016.

“Best of luck in this very different world.”

A lot can happen in four years. Donald Trump had just been elected president.

Snowden was living in exile in Russia, while Assange was four years deep into his bleak stay in the Ecuadoran embassy in London.

WikiLeaks, which had released a trove of Hillary Clinton’s campaign emails, was being blamed for her loss.

James Comey and the FBI had undermined Clinton, but soon the country’s intelligence agencies would be recast as deep-state heroes investigating Russiagate and Trump’s perfidy.

The shock over the mass domestic surveillance conducted by the NSA, FBI, and other agencies during the Bush and Obama administrations, with the lucrative cooperation of private-sector partners, had seemingly been swept away as a matter of concern as people eagerly gave all kinds of private information to Facebook, Google, and Amazon.

Those who had given up their freedom to call attention to this institutional corruption were either forgotten or dismissed as traitors.

With Sylvia Mann and Esteban and Freedle.

Despite his bravado in the face of incarceration, Brown was transformed by prison life.

He mostly dodged the rampant violence, but he certainly observed it, along with its racial castes.

“An American prison is many things,” Brown writes, “and among them is a Nazi training camp.”

He had gotten clean from heroin while incarcerated and began regularly taking Suboxone, which was smuggled in as thin strips that could be eaten or broken down and snorted, but he developed other maladies, including complex PTSD, which he says took years to fully manifest.

As friends and colleagues told me, it seemed as if Brown didn’t have much postprison support.

“I definitely had concern for his well-being because he’d been through an enormous amount,” said Alex Winter, who directed Relatively Free, a short documentary about Brown’s daylong drive with his parents from prison to a halfway house on the other side of Texas.

youtube

On probation in his native Dallas, Brown bounced between freelance-writing commitments and antagonizing the authorities.

He started the Pursuance Project, a continuation of previous efforts to build digital tools and communities for activists, whistleblowers, and journalists to collaborate on investigations.

In April 2017, after giving some interviews about his incarceration, Brown was arrested and held for four days for allegedly violating a ban on talking to the media.

(He says he was released without charge and calls it an illegal confinement.)

“I would call the people who did this a bunch of chicken-shit assholes that are brutalizing the Constitution,” said Jay Leiderman, Brown’s lawyer at the time.

“All these enemies I’ve made are still out there,” Brown says in Relatively Free, though it increasingly seemed as if his enemies extended well beyond the surveillance state to include people he had once considered friends and allies.

After Brown wrote for D Magazine about the murder of Botham Jean, who was killed in his apartment in 2018 by an off-duty Dallas police officer, Brown began receiving death threats.

When The Intercept shut down its archive of Snowden documents in 2019, Brown burned his National Magazine Award certificate in protest.

Hodge told me Brown’s actions were “incomprehensible,” saying he was prone to the kind of “propaganda of the deed that doesn’t really accomplish any goals, either journalistic or activist.”

Brown denounced The Intercept for insufficiently protecting the identity of whistleblower Reality Winner.

youtube

In an email to the site’s staff criticizing what he called a cover-up regarding the Snowden archive, he reminded them that he had “won the outlet their first National Magazine Award from a fucking segregation cell during a prison term that stemmed from my attempts to stop firms like Palantir from going after people like Glenn” Greenwald.

He believes right-wing tech oligarch Peter Thiel — the archvillain of Brown’s personal cosmology — is in cahoots with The Intercept’s original funder and fellow PayPal mafia member Pierre Omidyar.

Brown also fell out with Greenwald, whom he criticized as a tool of Thiel’s.

The institutions around Brown seemed irredeemably rotten.

He spent four years in federal prison for a cause he believed in, and now strangers were calling in bomb threats to the magazine publishing his work.

The media wasn’t up to the task of fighting the rise of fascism.

As he writes in his memoir, “It takes years of direct experience with the press to grasp the real extent of its failures, to recognize the patterns of incompetence, laziness, careerism, and cowardice that may be easily confused with complicity, given that the end result is the same.”

He left the United States vowing never to return and moved to Antigua to live in a house rented for him by a wealthy patron.

It didn’t last long.