#petromodernity

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

"Modern consumerism relies on the subject believing that they are in control, while their thoughts and actions are progressively delimited by a fossil infrastructure that molds the ostensible user in its own corrosive image, leading to an inversion of user and used."

49 notes

·

View notes

Photo

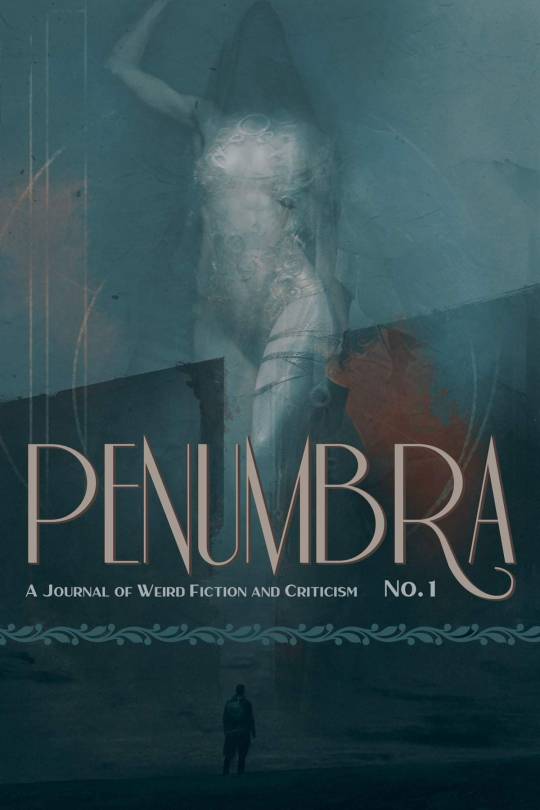

Penumbra: A Journal of Weird Fiction and Criticism, No. 1, edited by S. T. Joshi, Hippocampus Press, 2020. Cover art by George C. Cotronis, cover design by Daniel V. Sauer, info: hippocampuspress.com.

Penumbra is a new annual journal that seeks to present cutting-edge articles on weird fiction as well as original weird fiction by some of the most talented contemporary writers in the field. This first issue contains scintillating new fiction by such veterans as Mark Samuels and Michael Aronovitz, as well as by new and up-and-coming writers such as Curtis M. Lawson, Manuel Arenas, Belicia Rhea, and others. As a “classic reprint,” we present a rare story by Gertrude Atherton. Among the works of criticism and scholarship, Matt Cardin studies a story by Thomas Ligotti; John Tibbetts supplies a detailed overview of the ghost stories of Edith Wharton; James Goho analyzes the work of Simon Strantzas; Darrell Schweitzer assesses the eccentric tales of John Collier; and Nancy Holder demonstrates the frequency with which Sherlock Holmes has entered weird fiction over the decades. Other essays touch on the work of Edgar Allan Poe, Lord Dunsany, China Miéville, Jean Ray, and William Hope Hodgson. Mark Samuels translates a little-known essay on weird fiction by Stefan Grabinski, while Jason V Brock provides an essay on zombie films. We also feature verse by such leading contemporary as Wade German, Adam Bolivar, John Shirley, Darrell Schweitzer, Nicole Cushing, and Leigh Blackmore. All told, Penumbra is a rich feast of weird fiction, poetry, and criticism, showing the vibrancy of a genre that is enjoying immense popularity in the present day.

Contents: Editorial Fiction If Destiny Still Reigns – Mark Samuels The Truth about Vampires – Curtis M. Lawson Las Llorasangres – Michael Parker Static – Belicia Rhea The Slug – Jon Bockes Counter-Current – Michael Aronovitz The Crazy Mountains – Dylan Henderson The Hell of Mirrors – Manuel Arenas Door Skin – Belicia Rhea Classic Reprint The Caves of Death – Gertrude Atherton Nonfiction Icy Bleakness and Killing Sadness: The Desolating Impact of Thomas Ligotti’s “The Bungalow House” – Matt Cardin The Cosmic Scale of Elfland – Michael D. Miller The Idea of the North in the Fiction of Simon Strantzas – James Goho I Walked with a Zombie: The Tragicomic World of the Firefly Clan – Jason V Brock “The Terror of Solitude”: The Supernatural Fiction of Edith Wharton – John C. Tibbetts Finding Sherlock Holmes in Weird Fiction – Nancy Holder Confessions – Stefan Grabinski “The Weird Dominions of the Infinite”: Edgar Allan Poe and the Scientific Gothic – Sorina Higgins The Psychic Sleuth Who Survived – Lee Weinstein The Resurgence of a Fallen Angel: Echoes of The Ghost Pirates in “The Mainz Psalter” – Hubert Van Calenbergh Monstrous Tourism: Petromodernity in China Miéville “Covehithe” – Rhonda Knight John Collier: A Weird Fantasist in Jester’s Motley – Darrell Schweitzer Poetry Mormo – Wade German To Live at the Edge of a Black Hole – John Shirley Et In Arcadia Jack – Adam Bolivar The Mysteries of the Worm – Darrell Schweitzer Delirium Vivens – Nicole Cushing The Fantastic Flame – Leigh Blackmore Notes on Contributors

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Burnout: Paradise

youtube

1. Burnout. Spinning wheels without moving. Antipodean slang. The smell of burned rubber.

The blank word document is another rounded bend. A few cars here and there loaded in. Driving these virtual streets is seeing ideas, tangents, discourse, thoughts spill off. In front is always nothingness. An inability to grasp on to anything coherent. Yes this is synecdoche, yes this is consumerism, a shiny shell of petromodernity – an actual critical theory term that I now take seriously - yes this is me, my life, my phd in miniature, the imperfect totalising open-world game, or yes this is a microcosm of the entirety of trying to play through the letter “B” of my steam library, stop-start, hopeful then despairing, takes longer than it should, yes this game is a magnum opus and I wish so hard to fill my lungs and release until my fingers are pinching some inflated balloon perfectly full of a graspable idea, or yes this game is fundamentally empty, a comment on a comment; at the bottom of all searches for purpose we find searches for purpose, etc.

So I start and I start and I start again. I drive I drive I drive. Event after event ticks down, my license goes from learner to D to B to A and then I hit my goal, “Burnout license”, and still I don’t know what I’ll write. Something about driving, in general; driving as notionally relaxing, driving while thinking about other things. How do people write? Write things? My PhD is in pieces on the floor and in the computer and in my head. I drive around Paradise City and terrible emo from the mid-noughties plays, interspersed with long bouts of classical. Days pass, and in the game the day turns into night and back again, and I adjust the clock to make this happen slower, and the weather changes in Paradise City, a little – cycles of rain and cloud and sun - and here in Melbourne the weather changes too. It was the tail end of summer when I started, and we’ve been through the surprising highs and lows of autumn, now settling into winter, doing it all again. There are no roads leading in or out of Paradise City, and it’s a long drive back from the hills.

2. Burnout. A series of arcade-style racers made for various platforms by Criterion Games [official site] between 2001 and 2011.

It’s a little uncanny, this pocket of 2008. It just looks real good to my rusty, unfussy eyes, like in visual terms it hasn’t aged in ways other games from that year age (though my friend James vehemently disagreed). It does the trick. It does lots of tricks. And it seems rare too, to say of a 2008 game that it’s a masterpiece, that it’s the best of its class, though of Paradise this is surely true, if all reports are to be believed with regards to all other open-world arcade driving games that have come since, including everything else made by Criterion.

Any doubts about its age are firmly put to bed by the soundtrack, though, which despite prominently featuring that Guns N’ Roses song from 1987 just screams mid-2000s at me, abundant “rock” guitars, masc whine and all, very of its time, salvaged by one timeless Avril Lavigne banger, a chunk of classical, and (to a certain extent) personal nostalgia for a time when this sort of soundtrack just seemed vaguely synonymous with ��driving game”. There’s also the dated blemish of inane unmutable advice-slider DJ A(u)tomica, who at least has the good grace to (somehow) avoid repeating himself, even after seventeen hours of driving, at a clip of one quip every few minutes or so. There’s also the very 2008 nod to renewable energy via Paradise’s wind farm, harking back to that post- An Inconvenient Truth moment of progressive euphoria when we really all believed we could build towards a sustainable future that would also accommodate our oily desires, before another decade of resource-industry funded filibustering hadn’t proven this, again, impossible.

And yet Paradise stands up in ways that surpass the non-ironic soundtrack of fragile masculinity and the very 00’s DJ Atomica, despite or because of the people-less world, the flat and drab urban interior, the hardly even tokenistic ways of engaging with the city as function rather than form. I particularly like how B:P has not even the faintest hint of story, how even in terms of progression it purely becomes a game of exploration, winning events, checking boxes. It melds (excuse me for a second) form and function and manages not to get in the way of itself – the story is what the player does in the game, where the player goes. It’s kind of breathtaking, rare for any game before or since. (Hopefully it’s clear that I’m not advocating for the dissolution of narrative in games, only that the lack of narrative pretence here is very suited to this particular game, and very preferable to the kinds of irrelevant and bloated narratives that are thrown over e.g. other driving games).

Ah, 2008. It was just there! And yet so far. I played Burnout Paradise for a running total of seventeen hours over nearly three months. During this time, I also played forty-two hours of Tetris99. Everything in its place. Criterion recently announced they’ll shut down the Burnout Paradise’s online servers in August, though Paradise lives on in Remastered (2018) glory, Origin only.

3. Burnout. The act of refuelling the boost capacity of an engine by running out of boost.

Despite the time I’ve spent with it, the fact that I managed to complete its main in-game objective, and the running thoughts on time and place and representation of cultural norms, I feel I’m struggling to say much of definition about Paradise that fits easily into the scrapbook nature of this blog. Perhaps in some ways it's too close to life; a series of arbitrary checklists through which feeling happens (nebulously) around. I "liked" it but do not feel moved to thought, and I'm aware that that is the point – it’s a game that allows you to drive, endlessly, if you want to, think and do whatever. It won’t get in the way (barring DJ Automica butting in every couple of minutes – he literally cannot be switched off).

I do not drive much these days. Last year when Lauren and I moved to Canberra, we drove nearly 4000 kilometres across the country. The landscapes wound by, at the time fleetingly, but they piled on and left deep rivulets in my head, and though it was just five days and nothing really happened – we leant on the accelerator, stopped every hour, listened to music, stayed in nothing-motels quite literally hundreds of kms from anywhere else and ate forgettable takeaway - it feels immense, now. Driving is funny like that - you are never quite in a place, separated from it by machine noise and windows and infrastructure, the one activity you can do to facilitate thinking about something else. Still, impressions, motion, the sense of having moved, of having journeyed. Here in Australia, the fossil fuel lobby has won its third straight election in a row. Hope is eroding into nothing.

Probably my favourite hour or two in Paradise City was spent mucking around in the online section with Roy and James, trying to check off a few of the game's multiplayer challenges. These involved such serious exercises as trying to do barrel a series of barrel rolls, or try and land on top of each other, or smash into each in mid-air, or drive on top of a parking lot to jump a ramp onto a shopping centre. It was very good, if a little eerie and dystopic, strewn with outdated real-and-paid-for advertising billboards, branded vehicles, quaint echoes of paused time and uncanny dilapidation.

The mill of the game I could never quite settle on - I “liked” it, I think, but it wasn’t without problems. I found the single-player events to be mindlessly enjoyable, ploughing other cars into crash barriers, or effortlessly holding down "boost" to accelerate down a straight and into a finish line, celebratory cutaway shot ensuing. Sometimes I crashed into too many grey girders that my eyes hadn't picked out and got frustrated, or sometimes I missed a critical turnoff and got frustrated. Sometimes they just felt like chores, and it was certainly sometimes annoying to not be able to restart events that I had botched, and it took me ten hours to learn you could opt out of races, stunt runs etc just by letting the car idle for a few seconds. And knowing this probably would have saved me a lot of time in the early game, because like I said it’s a long way back from the hills, where like three out of eight events end up at, and committing to staying in a race which after a couple of botched turns and unseen barriers you’re definitely not going to win, whose distant finish line is going to land you a long way from the nearest event (once you finally get there) can feel pretty dire, really, though there was also part of me that admired how Burnout refused to let you jump around the map, forced you to drive, take your time, see the city, see the sights.

I did appreciate the cracky coloured collectms of Paradise City, how they brought the city to life, sort of, or gave it the impression of being a well designed and thought-through playground, though I never got too completionist about them, the core exercise of the whole thing. Both John Walker of RPS and Chris Donlan of Eurogamer have written about Paradise’s fluoro crash gates, the impulse to reinstall the game every year and knock them all down from scratch. Along the way to getting my “Burnout license” I unlocked 36 of the 75 vehicles, jumped 35 of the 50 super jumps, broke 79 of 120 neon red billboards, and smashed through 353 of 400 aforementioned glowing yellow crash barriers. The game puts me at 55% completed. No steam achievements (woulda been nice, perhaps, given that Burnout Paradise is fundamentally a collectmup; nothing but metres and percentages). I’ve driven a little over 1000 miles, supposedly, which is certainly more than I’ve IRL driven over the past few months.

4. Burnout. noun Physical and emotional exhaustion; breakdown caused by overwork. Commonly associated with “crunch”, “the video game industry”.

But here there is also pure hesitation. Procrastination. The fear of moving on, even at the end of this little step of what has ballooned into an impossible project. I can see the next letter waiting there, a new chapter, a chance for renewal. The one disappearing behind us has drawn out so far, encompassed a few years and a fair bit of change, and now almost petered into nothing at the final gate. I want to hit the ground running but I'm not sure I'm ready, and in the meantime various other deadlines swirl around, make it difficult to see the clear path ahead that I crave. And so it is that the temptation has been there to keep driving the streets of Paradise, its anonymous suburbs and abstract goals, continue delaying the inevitable, or the nearly inevitable, or the not-inevitable-at-all of writing this post and moving on to the next chapter, because it turns out this is a project I once made a choice to begin, and could at one point choose to stop.

There are nagging questions, of course. Who blogs, anymore? Who reads blogs anymore? How does one find a blog they like and then continue to follow it for the span of its natural life? Does anyone use “bookmarks”? What’s an RSS feed? I'm not even sure, in a broader sense, that I know where to find the kinds of writing about games that I want to read at the moment, at least not reliably, outside of say the occasional check-through of Critical Distance or Unwinnable. I look at the slate of games coming out and find it hard to be excited by anything much, the hype and the saturation. It is bountiful until it is not. The guilt element of playing games – something inherited from childhood that I’ve never been entirely able to dissociate - has become more and more prominent. I've increasingly used games as a tool for procrastination and a coping mechanism, a distraction from various (work/study and other) anxieties. I've also been aware of myself doing this, and in turn the kinds of gaming experiences I've relied on have been more focused on short term, low-investment distraction (hence the sudden unyielding devotion to Tetris, which really was just filling the hole left by an earlier act of self-discipline AKA uninstalling Rocket League; more recently, as I’ve managed to put the Switch away for longer periods, I’ve turned back to another simple but deceptive time-filler in Mini Metro. Choose your poison, basically). For a while it seemed Burnout would not only fill this role but do it responsibly: it seemed great for dropping into in short bursts - win a race or two, unlock a new car maybe – without quite the same dangerously addictive pull for me as those other games. But then I heard the GnR song "Paradise City" one too many times (it's mandatory with startup), or got sick of the menu loading times, and it lost this specific part of its appeal.

And then there's the subjective nature of this particular Sisyphean project - the knowledge that here I am pushing a rock up a mountain of my own making, one that exists only for me, entirely built out of and defined by the games and bundles I chose and continue to choose to buy, the rules I chose to set. Life is short, this task is absurd, and at the moment it's not even a joke I feel particularly happy about sharing. Sometimes I get to play great games here, games I may never have gotten around to; at other times I am playing shit games for this blog, and in the process there are inevitably other things I'm not doing. One choice erases another. Increasingly it feels like an isolated pursuit - playing games in general, not just the writing and making of this here blog. It seems like I know fewer people who play games these days, between falling out of touch with friends, seeing lots of other old friends give up games in one way or another, and playing games less frequently with those who I still know. I’ve accidentally become something of a game hermit. For years I've loved the camaraderie and easy familiarity of social gaming experiences even when I haven't loved the games that conduct them - the feeling of being connected to people even in a transient, shallow, goal-oriented sense, but even these I'm not sure I believe in anymore, or I find myself less and less willing to invest in the "right" titles to facilitate it.

I’m into my thirties now, and maybe this is just a feeling of age, life, I dunno, priorities finally shifting to where people told me they should’ve years ago. One of my oldest friends is about to have a baby, though he more or less quit video games over a year ago now. I'm extremely happy for him. Two of my younger cousins just had children, several hours away by plane – my uncle, a new grandfather to two babies, makes posts on facebook claiming climate change is a socialist hoax, and I can’t help but think of the kind of world his grandchildren are going to inherit. I'm mulling over a missed deadline that's been a thorn in my brain now for months, the single-largest hitherto unsaid reason why this post has taken so long to dig its way to the surface. This month marks the five year anniversary of another cousin’s sudden/unexpected passing; he was five years older than me, and though I’ll never be able to make sense of it, I feel like I get that there’s something sort of vulnerable about this age, when the things you want don’t quite work out, or when you’re a bit aimless and stuck in your patterns and feel like things aren’t going to change. He was so kind and gentle, a beautiful soul and a terrible Zerg, and I miss him so much. And one year ago I drove from Canberra to Melbourne and slept on the floor of this house I now call home while I waited for a truck with rest of my stuff to arrive. I’m very aware of the calendar, of change and inertia, of patterns and decay, of newness sprouting underfoot, but I don’t know how games fit at the moment, or I’ve lost the thread of feeling like they’re actually important, or why, amongst all the noise.

Burnout: Paradise is at the start, in the middle, and right at the end of all these things. It's a great game, part of me feels, or wants to say I feel. Playful, irreverent, childishly violent, simultaneously full of stuff and empty of matter. I'm happy I've played it, happy I can say that I've played it, happy to understand on an experiential level most of what it offers, happy I'll be able to remember it later, nod in some hypothetical conversation where someone brings up Burnout: Paradise and say I know what they mean, yeah. I get it. When we were playing it online together briefly, a couple of months back now, Roy told me that Burnout Paradise is the only game he ever one hundred percented twice - once on 360, once on PC - and that it was almost three times, because the first time he was almost done with it, someone broke into his house and stole his Xbox and all his games, and that Paradise was the only game that he re-bought with the insurance money, so determined he was to tick every box the game left open to tick, even if it meant doing it all again.

But maybe – counterpoint - I don’t get it. I’m finding it harder and harder to make good sense of this kind of experience, or feel like this kind of thing is (in some arbitrary way) a net positive, or that it’s okay to keep glossing over the emulation of destruction that games of so many different kinds fundamentally rely on. Outside there is so much suffering, so much to be upset about, and I no longer feel like there is time enough to sink into mindless (rather than meaningful, perhaps?) distraction. Or I’m finding it harder to get beyond the thought that this is an extension of the distraction/avoidance behaviour that I realised might actually be a problem in my life.

“Burnout” is, you’ll know, here in the great mess of the year 2019, a buzz word, particularly in the games industry. Games company employees have perpetually been expected to work unsustainable hours out of some sort of devotion to the industry, creating a cycle of talent depletion and toxic work cultures. But as is often the case with games, it’s a tip-off of what happens elsewhere, across the board. The mass casualisation of careers across all industries, the gig economy, pressures caused by un- and under- employment, the dissipation of viable faith, social-media and political stresses: all of these are leading to burnout, everyone has burnout, we are inundated with burnout. There is something ripe about the words or the idea of Burnout: Paradise, the very conceptual juxtaposition that seems to be two sides of the same coin, that feels very reflective of this moment, what we are all experiencing versus what we were promised. But what does this have to do with Burnout: Paradise, the game in which you pretend drive fake person-less cars around a virtual city, have horrific, visceral crashes from which you immediately respawn and “beat” by achieving a long series of arbitrary victories, collecting all there is to collect? Something, nothing, I don’t know.

“Burnout” means a lot of things, and the meaning of “burnout” the game adopts isn’t the other ones I’d associate with cars – a burnt out engine, or the smell of burning rubber - but one that exists only for the series, so far as I can tell: getting to keep using your boost because you’ve been continually using your boost. Keep going at all cylinders or bust, basically – except not, because the consequences for interrupting the boost are slim even on the relative scale of things that can go right or wrong, in this game where there is never really all that much on the line for the player anyway.

Paradise. n. Heaven. A place to await judgement. An enclosed park. Eden.

In Paradise City the grass is trim; the girls (all humans actually) are non-existent, unless you happen to be riding a motorcycle, presumably because a motorcycle without a rider would look very weird.

In Paradise City the cars are peopleless and drive themselves, so maybe it is an early vision of the tech bro version of Paradise. Or maybe the cars are driven by people who can only exist on the outside of the world of Paradise City, looking in across the matrix. Or maybe in Paradise City the people are the cars. This is Cars, the movie, sans dialogue.

In Paradise City all the cars emulate brands and models that exist in "the real world" but are called by names that exist only in the Burnout franchise.

In Paradise City all the cars ostensibly run on petrol, which is infinite but unnecessary, because going through a petrol station merely refills the car's boost capacity, whatever that is, rather than imply that your car would stop running if you at some point failed to “fill up”. It's very important that you know, though, that the cars run on petrol, because otherwise it wouldn't be a realistic representation of cars. Even in Paradise.

In Paradise City cars exist and then don't exist.

In Paradise City a lot more cars suddenly exists if someone decides they want to flip their car over and see how much monetary damage they can cause.

In Paradise City cars crash and crumple in a hyper-realistic way, but it's okay because the cars have no drivers and anyway all cars are all miraculously fine again after a few moments.

In Paradise City the railway has been shut down to give cars more places to hang out.

In Paradise City the whole city runs on wind energy, because it's important to care about the environment too, because you can have both, promises the radio, though seeing as there's nobody there in all of Paradise's buildings it's unclear, anyway, what such energy would actually be running.

onward to Caesar 3

#game70#burnout: paradise#burnout#criterion games#EA#cars#open world#humble origin bundle#2008#petrol

1 note

·

View note

Photo

0 notes