#nude on the railway

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Angel Constance

469 notes

·

View notes

Text

Naked on rails

#muscular#gay#model#body#hot#posing#pose#outdoors#railway#railroad#tunnel#sexy pose#gay men#nude pose

1 note

·

View note

Text

Masterlist:

BUY ME A COFFEE

Artist of the Month Masterlist

Lesson Recommended Readings

Uni Lectures Masterlist

Essays on Exhibitions/Other:

✨Crown to Courture Exhibit, Crown to Courture Photos: 1, 2 ✨Alphonse Mucha Exhibition, iMucha Photos: 1, 2 ✨Sargent and Fashion Exhibition, Photos: 1, 2, 3

University Writings:

✨The Execution of Lady Jane Grey, Paul Delaroche, 1833 ✨The Toilet of Venus ("The Rokeby Venus"), Diego Velazquez, 1647 - 51 ✨Chapter Critique: The Role of Women in the Iconography of Art Nouveau ✨Exhibition Catalogue: Reflecting Upon Nude Veritas ✨Q1: What is left out of Visari's history of art? (Exam Question) ✨Q2: 'Attention to visual form is an essential component to art history.' Discuss. (Exam Question) ✨Cambridge: Fitzwilliam Museum. Institution Analysis: 500 words ✨Presentation of two (or more) case studies: Fitzwilliam Museum vs British Museum ✨Decolonising: Two Institutional Approaches (British Museum and Fitzwilliam Comparison)

Books/Other used in Uni work:

✨The Role of Women in the Iconography of Art Nouveau, Jan Thompson, 1971 - 72 (Art Journal) ✨The Wilderness of Mirrors, Albert Cook, 1986 (Academic Journal) ✨Vienna Sucession, Roberto Rosenman ✨A Painting - Manet's The Railway (Exhibition Catalogue) ✨A Painting - Mantegna's Adoration of the Magi (Exhibition Catalogue) ✨A Drawing - Hepworth Fenstration of the Ear (Exhibition Catalogue) ✨A Manuscript - The Chronicles of England (Exhibition Catalogue) ✨Mahler and Klimt: Social Experience and Artistic Evolution, Carl E. Schorske, 1982 ✨Two Austrian Expressionist, Alfred Werner, 1964 ✨'Heil the Hero Klimt': Nazi Aesthetics in Vienna and the 1943 Gustav Klimt Retrospective, Laura Morowitz, 2016 ✨Avoidance and Resolution of Cultural Heritage Disputes: Recovery of Art Lootes During the Holocaust, Lawrence M. Kaye, 2006

Recommended Video Essays: Link to Playlist

✨How Artists Respond to Political Crisis ✨A Lecture on J.M.W.Turner and Colour

Other:

✨Jobs ✨Concept/Comic Art: 1, 2, 3 ✨Visual Analysis Tips: Checklist ✨The Anatomy of a Painting ✨More detail about Blog ✨Key words and Symbolism ✨Where to Begin with Art History... ✨Checklist For Essay Writing

#writing#art gallery#art hitory#essay#masterlist#art#paintings#art show#art exhibition#essay writing#video essay#book recommendations#lecture#life lessons#experience#culture#artwork#updating

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ask box might be closed

Due to the influx of art requests and TTTE related questions, we are considering closing the ask box temporarily.

Let us remind you all that this blog is for the Norwegian childrens bookseries "Norske Jernbanehistorier" (Norwegian Railway Stories). It has no affiliation to TTTE or any of that franchise at all. It is its own franchise. We do understand that is is easy to mix up due to both franchises featuring locomotives with faces, but please do not ask us things related to other franchises here on this blog.

This is for questions about the Norwegian Railway Stories. Not everything else.

Also please don't send us your nudes. We don't need to see those.

We try our best to answer everyone's asks, but sometimes we choose to delete some.

The author does not do art requests, and especially not requests related to Thomas the tank engine or OCs related to that franchise. If you really want her to draw you something, wait for her to open up commissions.

We're sorry.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

@Studiorassias presents the workshop "Railways Nude" @studiorassias by @vangelis_rassias_photogtraphy (concept and lighting) with @kanhada90 creative art model.

The workshop will take place on 22/10 in Athens using the ruins of industrial archeology... supported by @photometron_@hasselblad @omsystem.cameras

For info: insta @vangelis_rassias_photography fb messenger studio rassias e-mail [email protected]

#newproject

#studiorassiasworkshop#vangelis_rassias_photography#industrial#railways#industrialarchaelogy#outdoors#artnude#sensualbeauty#body#fitness#perspectivephotography#outdoorslighting#seminary#kanhada90#model#bodyshape

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Please tell me more about this 600mm French narrow gauge tramway...

What 600mm gauge tramway?

This 600mm gauge tramway:

Since you asked politely, that's probaply the Chemins de Fer du Calvados (abbr CFC) was a 600 mm (1 ft 11+5⁄8 in) narrow gauge railway, judging by the 40lb rail in the picture -- the line at Ouistreham carried tourists visiting the beach resorts of Riva Bella -- not to be confused with the nude beaches of the same name in Riva Bella, Corsica, France.

... Following the outbreak of World War II in 1939 (a too polite way to put it?), the CFC initiated heavy year-round service, for some reason. Heavy traffic of iron ore and coal for the French steel industry necessitated 30+ of the little trains per day. ... The CFC lines closed on 6 June 1944, after the track was destroyed during the D-Day landings (as seen top pic -- gee, wonder what could have happened). It is said that the first train of that fateful day, hauled by No. 10, was abandoned at Luc-sur-Mer, never to complete its journey. No. 10 was a 4-6-0T, one of six tank engines built 1905 for the CFC at Weidnecht Frères &Cie, the French version of Decauville, a WWI trench railway manufacturer.

This has been, too much train trivia with Tristan; tune in next time to hear Tristan say, "did you know that one of CFC's unique Crochat petrol railcars is preserved in the Musée des Transports de Pithiviers?"

Men of No 4 Commando engaged in house to house fighting with the Germans at Riva Bella, near Ouistreham. D-Day, 6 June 1944.

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Adelaide is Australia's fifth largest city

Adelaide is the only major metropolis in the world to have its city centre Adelaide, The CBD from across the Torrens River at Australia Adventurescompletely surrounded by parkland. Today, driving along King William Street towards the Torrens, the layout of this city is immediately evident. Are you a BIG lover of 2023 Nude Calendars, find a big collection of 2023 Nude Calendars here.

Past the Adelaide Oval, considered by many one of the finest-looking traditional cricket grounds in the world, you cross the Torrens River to arrive at North Terrace. (For children, a trip on Popeye, a launch that plies the river from near the Festival Centre to the Adelaide Zoo, is a great outing.) This tree-lined boulevard has many fine buildings: Government House, the State Library, the South Australian Museum, the Art Gallery of South Australia (which contains the larges collection of Aboriginal artifacts in the world and Adelaide University. A little further along, past the Royal Adelaide Hospital, are the Botanical Gardens and the State Herbarium, begun in 1855. These gardens include the oldest glasshouse in an Australian botanical garden, and the only Museum of Economic Botany; the Conservatory contains a tropical rainforest. The the west of King William Street is Parliament House, completed in 1939; a little further along, in what once was the Adelaide Railway Station is the Adelaide Casino.

Continuing along King William Street you come to Rundle and Hindley Streets - the former is the shopping heart of Adelaide, the latter is the night spot centre - then the town hall. A little further south is Victoria Square, with lawns and

a fountain, the terminus for the Glenelg tram, and the clock tower of the GPO. King William Street continues to South Terrace, where gardens and parks, including the rose garden and conservatory and the Himeji Gardens (a traditional Japanese garden), make up the southern perimeter of the city proper.

Being so close to the Barossa Valley and the wineries of the Vales to the south, it is no wonder that Adelaide boasts more restaurants per capita than any other city in Australia. Hindley and Rundle Streets in the heart of the city, Gouger Street, close to Victoria Square, and O'Connell and Melbourne Streets in North Adelaide are the best places to go.

Glenelg, on the coast just 10 km from the city centre, and a city in its own right, is the summer playground for Adelaide residents and visitors - the larges amusement park in the State, and many restaurants, are here. Port Adelaide, 25 minutes west of the city, is home to the South Australian Maritime Museum, the Historic Military Vehicles Museum, and the South Australian Historical Aviation Museum, among others. Here you can also cruise on an old sailing ketch, or take a steam train ride along the old Semaphore Railway.

The beaches south of Port Adelaide (including Glenelg) are ideal places to swim and many have a jetty where kids and adults can dangle a line. Further south the beaches are even better; surfers love the breaks in and around Christies Beach, Moana and Seaford. For divers there are the reefs and marine sanctuaries at Port Noarlunga or at Aldinga. The nearby Mount Lofty Ranges offer other nature experiences - seeing native animals close up at Cleland Wildlife Park, picnics and day bushwalks at Belair National Park, and rock climbing at Morialta Falls Conservation Park.

Any mention of Adelaide must include reference to its major international festival, the Adelaide Festival, held in March; artists from around the world come to perform here. There are a host of other festivals and events, including Adelaide Fringe Festival in February, the Oakbank Racing Carnival in April, the Royal Adelaide Show in late August/early September, and the International Rose Festival in October. In the Adelaide Hills, the Barossa Valley or down along the Fleurieu Peninsula there are many other festivals.

For the history buff there are the Mortlock Library of historical material, the Migration and Settlement Museum and the South Australian Police Museum, and the SA Theatre Museum, a magnificent complex of halls and theatres.

1 note

·

View note

Text

He's making a terrible impression. The worst feeling in the world is when you know you're crashing the train but you can't stop it. You can see the broken railway in front of you but christ...

She seems to soften up a bit though and Asa's just glad for that. Nods, taking another shallow breath. "I am sorry." He finally says, and looks back into the crowd. He'll either see one or the other. A different pang in his chest, depending. A different wound. This time it's Lee and he swallows.

"I'm. In truth, I just got some. Upsetting news." It's the best way to say it without being weird and uncomfortable to this poor person he's just met. "It's why I'm-" He's coming back down to earth, trying to center himself. His sister? Right. Thalia. "Blond... arresting features. She's in... um. I believe it's a peachy, almost nude color..." The hand on his arm centers him. Reminds him of Aria for some reason. "Thank you." He says honestly.

He laughs at Riley's description of him, and she's glad that he doesn't take it poorly, and she quirks half a smile. "Yeah, usually I hear from her when 'her old man friend is asleep'. Nice to put a face to the name." She's not expecting him to be so frantic about not seeing Aria though, and that makes the smile drop. "Okay, we don't have to." She doubts Aria wants to see her either. But she softens, understanding anxiety and being around crowds, and she gently puts a hand on his arm.

She ignores his backtracking, because she doesn't know this man. All he knows of her is what Aria has told him, and if he was willing to throw her off the balcony for it a few seconds ago, then she can connect those dots. Perhaps it's what she deserves after all. "What does your sister look like?"

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

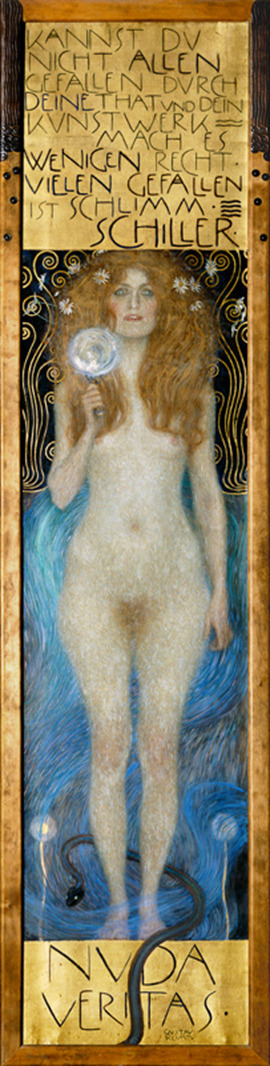

Exhibition Catalogue: Reflecting Upon Nude Veritas

Masterlist

BUY ME A COFFEE

Work written for University Assignment based on Catalogue Essays/Writings. Examples: A Painting - Manet's The Railway - A Painting - Mantegna's Adoration of the Magi - A Drawing - Hepworth Fenstration of the Ear - A Manuscript - The Chronicles of England

Painted during the end of the 19th century, by Viennese painter Gustav Klimt (1862-1918), the oil painting, Nude Veritas (Fig.1), comes from the era of the Vienna Secession, an art period closely related to Art Nouveau, roughly between the years of 1890-1914. Through mixed media this movement focused on combining the natural world with the man-made, using the fine arts, sculpture, and architecture for decorative motifs. Nude Veritas was created far before either world war and the artist died before the WWII.

Nude Veritas clearly has art nouveau links, with the displayed female nude, gold leaf decorative frame that’s bold and striking, and text that’s reminiscent of posters from the era. Drawing more on Art Nouveau, the painting is hung like a portrait, with a nonrepresentational background, presenting an idealised female nude. The body is flanked by decorative patterns of gold leaf and flowers which was another common motif of Art Nouveau.

While this work draws heavily on Art Nouveau, it lacks the finish that is most associated with the movement, like clean and bold contour lines, flat colours, and exaggerated curving patterns, which do feature in this work but only as a background decoration. Nude Veritas also features a “fuzzy” textural quality, thanks to Klimt’s use of oil on canvas achieving brushed out and light paint, allowing him to create this finish which draws on the Impressionist movement and contains traces of early Expressionism. Impressionism, approximately 1860 onwards, draws on saturated naturalistic colour to exaggerate emotion, with visible brushwork and painterly qualities. Paintings like these emphasised accurate depictions of light to form atmosphere, focusing on ordinary subject matter. Expressionism used distorted imagery of naturalistic scenes for a radically greater emotional effect, and to evoke moods and ideas. Whilst Nude Veritas conforms to some aspects of this movement, it largely draws on Art Nouveau and Impressionism.

Fig 1. Gustav Klimt, Nude Veritas, 1899, Oil on canvas painting, 240 x 64.5 cm, Austrian Theatre Museum, Vienna, Austria

The text featured on this oil painting reads as follows: “KANNST DU NICHT ALLEN GEFALLEN DUCH DEINE THAT UND DEIN KUNSTWERK – MACH ES WENIGEN RECHT: VIELEN GEFALLEN IST SCHLIMM” (“if you cannot please everyone with your actions and your artwork – please only a few: to please many is bad”). “NUDE VERITAS” (“nude truth”)

Holding what appears to be a mirror or looking glass, the subject faces the viewer, challenging them head on, despite a blank and indecipherable stare. With full frontal nudity, and addition of pubic hair, the form becomes less idealised and far more confrontational. As our eyes travel lower, following her body down, we find a snake tangled at her ankles. Once again being confronted by “Nude Truth”, we find the snake obscuring the words possibly representative of an obstruction of truth. Perhaps the woman is the embodiment of truth, her nakedness linked to the word “nude” before truth and being on display for all to see. Or perhaps she is telling us to see a naked truth, once more linked to her bareness on display.

With this in mind, we must understand Klimt’s work and background to understand how this piece is recontextualised in WWII by the Nazis. There is a forgotten history here, as Nude Veritas and many others feature in an exhibit held by the Third Reich Party in 1943. Klimt’s work predominantly features women, due to the nature of the movements he was a part of. “Whenever he was free to choose his sitter, Klimt preferred the dark-haired, Mediterranean type of woman to the blonde, Nordic type so pre- dominant in the German lands.”[1]

Although The Kiss is highly regarded and known today, his other work falls into relative obscurity. Around the time Nude Veritas (1899) was finished, Klimt was commissioned to paint ceilings (1900). Philosophy, one of these paintings “was attacked as "painted lunacy," "pathological," and "immoral."”[2] While this highlights that his work was ridiculed during his life and was seen as controversial, it raises interesting questions about what the Viennese public of the 1940’s thought, under Hitler’s rule, as this work and many others of Klimt’s were displayed. However, his works were not in a degrading exhibition that the Nazis had been known to make, where they displayed artworks to humiliate and condemn certain artists and styles.

“The majority came only to jeer, but a counter-protest was staged by a small minority.”[3] These provocative pieces Klimt painted emphasize a set of conservative sensibilities, yet “writing of the Klimt era, the German Meier- Graefe said: "Woman influenced all this art, good and bad alike […] the worship of women is an integral part of the national culture."[4] How can Klimt works be considered part of a sexual revolution when the Nazi party advocated for a specific archetype of woman. The hypocrisy of the Nazis is laid bare by this contradiction, reinforced by Nude Veritas herself, inviting us to see a naked truth.

It has been well documented that “close to 16,000 works [that were] deemed degenerate were sold, burned, or ridiculed in exhibits set up precisely for that purpose.”[5] The amount of art destroyed under the Nazis, as well as the art that was condemned as degenerate, in some respects overshadows the work they did endorsed. Furthermore, there’s an estimated “100,000 artworks stolen by the Nazis [that] have still not been located”.[6] It is perhaps this we should be focusing our attention on as well, in addition to trying to understand what they were endorsing, and what they wanted the public to take away from their encounters with endorsed works, like Nude Veritas.

It's safe to say that there were a lot of factors against Nude Veritas and Klimt in general, for his work to be endorsed by the Third Reich. Just by looking at Klimt’s work, it’s clear that he does not paint archetypal Aryan women, in fact he seems to avoid them. Moreover, he had a well-documented history of Jewish patronage in Fritz Waerndorfer and his wife Lili. So, despite Klimt being dead by the time his painting was hung on display in the exhibit in 1943, it’s impossible to erase the history he left behind, and the documentation of his life. Yet despite these reasons and the fact that “Adolf Hitler had a tight grasp on the art that was promoted by the Third Reich Party, not one to delegate the task.”[7] it’s a surprise to see Klimt, an artist who succeeded in Vienna where Hitler had failed, being so readily endorsed.

It is precisely all these reasons that make Klimt’s work so interesting to observe from the lens of the Third Reich and their propaganda. Nude Veritas becomes such an intriguing piece to witness as she demands a reflection of the truth, and a self-reflection from the viewer.

Nude Veritas stand upright (240 x 64.5 cm), at just over two and half meters tall; the painting is incredibly large and imposing with a presence demanding to be looked at. This demand for attention is reinforced by Klimt’s use of goldleaf all around the frame, which exudes luxury and material wealth, something the Nazis were fond of: “The U.S. government has estimated that German forces and other Nazi agents before and during World War II seized or coerced the sale of approximately one-fifth of all Western art then in existence.”[8]

While most nudes of women are painted with sensuality highlighting a show of vulnerability, and for the pleasure of the viewer, this painting she stands tall and domineers, despite being a woman in the nude, the space she is presented in and the canvas she is painted on. Her nudity can be read as a primal exposure. This motif of primality is strengthened by her wild unkempt hair, as it bunches all around her head in a voluminous mass, intertwined with what appears to be wild daisies, giving her an untamed appearance. This nudity becomes a far more provocative work because of the fierce undertones it presents for a woman at the time. Moreover, this wildness she carries in her physical appearance, linked with the possible interpretation that she is a physical representation of truth, she reflects the true nature of a human, or women, which is unexpected for contemporary viewers.

Her mirror or looking glass only serves to reinforce the narrative of truth. The favoured interpretation is that of the looking glass, perhaps she is implying we inspect what we are shown, or told as truth, more closely and with greater scrutiny. That there is more than meets the eye, to study and dissect the painting and to carry that scrutiny and translate it into the world around us. Although her face is indecipherable, her eyes look glassy and distant, perhaps blind to truth, but desperate to see it and seek it out as she clutches her looking glass close and almost protectively.

More on the snake, toward the bottom of the painting; snakes are seen representative of duplicity and cunningness. A sign of danger and deception even from a Christian perspective with the garden of Eden, the woman here could possibly be interpreted as Eve. The snake literally is covering the truth up, it also travels towards and around the woman, encircling her legs. Possibly to physically stop her from seeing the truth or deciphering it, and potentially restraining her.

While it is hard to gauge what a contemporary audience would have taken away from this piece, as a modern audience we have a retrospective of the work. We know historically that the Nazis hid concentration camps from the wider world, and destroyed a great many more prized artworks, books, manuscripts etc. Nude Veritas gains another layer of meaning to us, if we were to place ourselves in the contemporary context, the hidden truth of the Nazis, relating their presence to the snake deceiving truth, and a physical showing of wealth and material power by possessing this, and other artworks.

Bibliography:

Morowitz, Laura, 'Heil the Hero Klimt!': Nazi Aesthetics in Vienna and the 1943 Gustav Klimt Retrospective, (Oxford Art Journal, Vol. 39, No. 1, 2016) pp. 107-129 [accessed 12 February 2024]

Kaye, M. Lawrence, Avoidance and Resolution of Cultural Heritage Disputes: Recovery of Art Looted During the Holocaust, (Willamette Journal of International Law and Dispute Resolution, Vol.14, No. 2, 2006) pp. 243-268 [accessed 9 February 2024]

Werner, Alfred, Two Austrian Expressionists, (The Kenyon Review, Vol. 26, No. 4, 1964) pp. 599-616 [accessed 10 February 2024]

#art#art gallery#artwork#writing#art tag#essay#paintings#art exhibition#art show#painting#drawings#drawing#in this essay i will#essay writing#personal essay#short essay#my essays#mini essay#art history#artists#writers#history#writeblr#writers and poets#writers on tumblr#creative writing#historical#lecture#academic writing#dark academia

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

WE ARE PRESENTING NEW WORKSHOP "RAILWAYS NUDE" 📸📸📸 @studiorassias by @vangelis_rassias_photogtraphy (concept and lighting) with @kanhada90 creative art model.

The workshop will take place on 22/10 in Athens using the ruins of industrial archeology... supported by @photometron_@hasselblad

For info: insta @vangelis_rassias_photography fb mesenger studio rassias e-mail [email protected]

#studiorassiasworkshop#vangelis_rassias_photography#industrial#railways#industrialarchaelogy#outdoors#artnude#sensualbeauty#body#fitness#perspectivephotography#outdoorslighting#seminary#kanhada90#model#bodyshape#newproject#beauty#art#photography#female

0 notes

Photo

“Nude Finn Nearly Frozen,” Toronto Star. August 23, 1940. Page 02. ---- Iroquois Falls, Aug. 23. - Almost frozen in 37 degree weather, a nude Finn was taken from the northbound T. and N.O. freight at Porquis Jct., at 6 a.m. today by Provincial Constable George White and Chief Ed Olaveson here. Of sandy complexion, almost six feet tall, he weighs about 180 pounds. He is not identified.

#iroquois falls#porquis junction#freight train#frozen to death#northern ontario#riding rod#riding the rails#nude in winter#close call#unknown man#temiskaming and northern ontario railway#canada during world war 2#finnish canadians#finnish immigration to canada

0 notes

Photo

In 1973, Ken Howard was sent by the Imperial War Museum to cover the Troubles in Northern Ireland as a war artist in all but name. (In the political rhetoric of the day, the province’s violence did not constitute warfare.) To Howard’s surprise, he found that his habit of painting en plein air made him friends on both sides of the sectarian divide. “If you used a camera, you were in trouble,” he said. “If you sat on the street and drew, and they could see what you were doing, then you weren’t in trouble.”

An IRA man in the Falls Road biddably blew up a car to make it more picturesque for his brush, Howard claimed. It was a small boy he saw swinging from a lamp post who would become the focus of his best known work, however.

Ulster Crucifixion (1978), now in the Ulster Museum, of the National Museums Northern Ireland, is made in the style of a gothic altarpiece, with a central panel, folding wings and a predella. The raw paint of its background both depicts and echoes the graffitied walls of west Belfast. Its child subject hangs from the post as though from a cross.

If Ulster Crucifixion was to be Howard’s most noted work, it was far from his most typical. Its flavour was, distantly, of Francis Bacon; a far more usual tang was of Claude Monet. To the horror of highbrow critics and a younger generation of British artists, Howard, who has died aged 89, was happy to describe himself as “the last impressionist”. He was, he said, “a painter of light”, in the squares of west London – his habit of sketching in the street led locals to dub him “High Street Ken” – in Mousehole, Cornwall, and in Venice, each of which place he kept a studio in.

Typical of this practice would be works such as Honesty and Charlotte (1990), made in his Chelsea studio. Painted contre-jour, against daylight, the canvas’s dappled colours take their cue from the titular vase of white seed pods in the centre of the composition. The glance of light off wallpaper, cloth, glass and flesh becomes the picture’s subject; its Sickertian nude seems almost incidental. So, too, with the subjects of Howard’s many depictions of Venice and Mousehole. “Mousehole is the one place in the world that’s close to Venice in terms of light,” he said.

His uplands had not always been so sunlit. Born in the north-west London suburb of Neasden, the younger of two children of Frank, a mechanic from Lancashire, and Elizabeth (nee Meikle), a Scot who worked as a cleaner, Howard recalled “painting properly from the age of seven and drawing and painting before I could write”.

An art teacher at Kilburn grammar school encouraged the young Ken to apply to the nearby Hornsey College of Art, where he studied from 1949 to 1953. This was followed by national service in the Royal Marines, then two years at the Royal College of Art (1955-57).

By then, Howard had already been through the prevailing trends of social realism – “I painted Neasden and power stations,” he recalled – and kitchen-sink painting. Both had brought him a degree of success. The first work he sold was of the shipyards at Aberdeen, where he had been taken by a lorry-driving uncle just after the war: the painting was bought by David Brown, the future owner of Aston Martin.

For all his later taste for sunlight and sea, Howard insisted that it was this early grounding in industrial grime that had shaped his art. “I was brought up surrounded by the horizontal and vertical structures of railway yards and factories,” he said. “I am not a landscape painter, but rather a vertical and horizontal painter.”

While this was clear in the composition of Ulster Crucifixion, it was less so in Howard’s many images of beaches, churches and Venetian canals. When he went to the Royal College, his fellow students were in thrall to abstract expressionism. “America had arrived just before I did,” Howard recalled. “I began to feel a bit out of kilter.”

He would remain outside the fashionable mainstream for the rest of his life. Whatever its linear underpinnings, his art was both figurative and unapologetically pleasant; to critics such as the late Brian Sewell, saccharine. His work with the British Army apart, it also seemed never to change, as Howard happily agreed. “I’m one of those people who always bangs away at the same nail,” he said. Despite showing in the Royal Academy’s Summer Exhibition for many years, he was nearing 60 before he was made a full Academician.

Above all, he admired Turner, and not just for what he termed the master’s “visual genius”. “I like the idea that, like Turner, I come from a working-class background,” Howard said.

In the 2010s, he retraced his hero’s trips through Switzerland in five journeys of his own, producing 100 monumental canvases of Swiss mountains and lakes and a book called Ken Howard’s Switzerland: In the Footsteps of Turner. In 2004, he had also followed Turner in being appointed the Royal Academy’s professor of perspective, a position he held until 2010. In 2017, he was made a patron of the Turner’s House Trust.

All this made the dismissal of critics such as Sewell easier to bear, as did the awarding of an OBE in 2010. Financial success also softened the blow. If Howard’s work never achieved the kinds of prices enjoyed by his more avant-garde contemporaries, he made up for it by being both prolific and popular. “I’ve probably got more pictures on people’s walls than any other painter living today,” he liked to say. Short, merry and given to theatrical capes and hats, he was not prone to introspection.

He also had a good eye for property. In 1973, Howard rented his Chelsea studio – once the atelier of the Edwardian society portraitist William Orpen – for six pounds a week. Over the next 30 years, he bought not just it but the large house in which it stood, worth several million pounds by the time of his death. “My mother always used to say that if I fell down the loo, I’d come up with a bar of chocolate,” Howard laughed. “I think that just about sums it up.”

He married three times: first, in 1962, to Annie Popham, a dress designer (they were divorced in 1974); then, in 1990, to the Hamburg-born painter Christa Gaa Köhler, whom he had met in Florence in the 1950s (she died of cancer in 1992); and last, in 2000, to the Italian photographer Dora Bertolutti. She survives him, along with a stepson and two stepdaughters.

🔔 James Kenneth Howard, painter, born 26 December 1932; died 11 September 2022

Daily inspiration. Discover more photos at http://justforbooks.tumblr.com

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lady’s Concept and Reference sheet -

Hello everyone! I’m back. :)

I’ve realized that I never made a full reference for my humanized Lady, so here it is! The first one here is actually several months old, and the first fully drawn out piece of her I’ve done.

Recently, I lost ALL of my concept art of her and a couple of other humanizations due to my iPad being reset and switched to a new phone service (dammit-). So, I have put together a mix of different designs I had of her before that happened. Forgive my messy note-taking. Haha! Also, slight TW for a nude back and scars...

(Don’t worry, she’s got some leggings on in her Guardian garment!)

I should elaborate more on what I have planned for her and my human AU that will come more in depth sometime soon. For now, I’ll just state some headcanons on how Lady and the realm of the Magic Railroad function here.

(One thing to note, this is both a human and engine AU.)

Lady’s clothes are completely made out of Gold Dust. When not in her engine form, she can picture herself however she likes and just make it appear with some magic! Think of it like a typical magical girl transformation but it happens in like an instant.

She has three long scars running down the lower right side of her back. These came from the encounter that she and D10 had long ago that was mentioned by Burnett in TATMR. She has tried removing them with magic, but to no avail.

Though she may look like it, Lady does NOT consider herself any higher in status or a ruler of any sort. As the natural guardian of all the magic the engines have and the Magic Railroad, she can’t help having a certain look to her that gives it away. As much as she would love to make friends on Sodor, she has to tend to the realm of the railway most of the time.

That’s all for now! I’m excited to share more later on. :D

#thomas and friends#thomas the tank engine#thomas and the magic railroad#tatmr#ttte lady#lady the magical engine#ttte humanized#ttte human au#ttte#ren’s artwork

170 notes

·

View notes

Photo

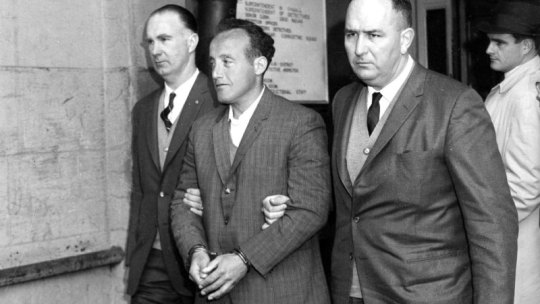

William 'The Mutilator' Macdonald

MacDonald was born Allen Ginsberg in Liverpool, England, in 1924. In 1943, at the age of 19, MacDonald was enlisted in the army and transferred to the Lancashire Fusiliers. One night, MacDonald was raped in an air-raid shelter by one of his corporals. The experience traumatised him, and the thought preyed on his mind for the rest of his life. Discharged from the army in 1947, he was diagnosed as having schizophrenia and committed for several months to a mental asylum where daily he was treated with electroconvulsive therapy.

MacDonald changed his name, then emigrated from England to Canada in 1949 and then to Australia in 1955. Shortly after his arrival, he was arrested and charged for touching a detective's penis in a public toilet in Adelaide. For this he was placed on a two-year good behaviour bond. After moving to Ballarat, MacDonald then moved to Sydney in 1961 as a construction worker. He found accommodation in East Sydney, where he became well known in the parks and public toilets that were surreptitious meeting places for homosexual men, due to the criminalisation of same-sex sexual activity.

The murders began in Brisbane in 1961.MacDonald befriended a 63-year-old man named Amos Hugh Hurst outside the Roma Street Railway Station. After a long drinking session at one of the local pubs, they went back to Hurst's apartment where they consumed more alcohol. When Hurst became intoxicated MacDonald began to strangle him. Hurst was so intoxicated that he did not realise what was happening and eventually began to haemorrhage. Blood poured from his mouth and on to MacDonald's hands. MacDonald then punched Hurst in the face, killing him. MacDonald then placed Hurst onto his bed, took off his trousers and shoes and pulled the sheets up over Hurst's head and tucked them in around all sides. MacDonald then waited there a while then turned off the lights and left the apartment.

On 4 June 1961, police were summoned to the Sydney Domain Baths. A man's nude corpse had been found, savagely stabbed over 30 times, and with the genitalia completely severed from his body. Alfred Reginald Greenfield became the second victim claimed by the killer soon to be dubbed "the Mutilator".

Greenfield, 41, had been sitting on a park bench in Green Park, just across the road from St Vincent's Hospital in Darlinghurst. MacDonald offered Greenfield a drink and lured him to the nearby Domain Baths on the pretext of providing more alcohol. MacDonald waited until Greenfield fell asleep, then removed his knife from its sheath and stabbed him approximately 30 times. The ferocity of the first blow severed the arteries in Greenfield's neck. MacDonald then pulled down Greenfield's trousers and underwear, severed his genitals, put them in a plastic bag and threw them into Sydney Harbour.

Similar to the second victim, Ernest William Cobbin, a 47-year-old male (possibly 36 or 37 years old) was stabbed repeatedly and mutilated. His body was found in a public toilet at Moore Park. On this night, MacDonald was walking down South Dowling Street where he met Cobbin. MacDonald lured his victim to Moore Park and drank beer with him in a public toilet. Just before the attack, MacDonald put on his plastic raincoat. Cobbin was sitting on the toilet seat when MacDonald, using an uppercut motion, struck Cobbin in the neck with a knife, severing his jugular vein. Blood splattered all over MacDonald's arms, face and his plastic raincoat. Cobbin tried to defend himself by raising his arms. MacDonald continued to stab his victim multiple times, covering the toilet cubicle with blood. MacDonald then severed the victim's genitals, placed them into a plastic bag along with his knife, and departed the scene.

On 31 March 1962, in suburban Darlinghurst, New South Wales, the mortally wounded Frank Gladstone McLean was found by a man walking with his wife and young child. He was the victim of an unfinished assault committed by MacDonald. The man found McLean still breathing, but bleeding heavily, and went to get police. On this day MacDonald bought a knife from a sports store in Sydney. That night MacDonald left the Oxford Hotel in Darlinghurst and followed McLean down Bourke Street past the local police station. MacDonald initiated conversation with McLean and suggested they have a drinking session around the corner in Bourke Lane. As they entered Bourke Lane, MacDonald plunged his knife into McLean's throat. McLean tried to fight off the attack but he was too intoxicated to do so. He was then stabbed again in the face and punched—forcing him off balance. The assault was interrupted by a young family approaching. MacDonald hid himself on hearing the voices and the sound of a baby's cry. Once the man and his family had left, MacDonald returned to the barely-alive McLean, pulled him further into the lane and stabbed him again. A total of six stab wounds were inflicted. He then pulled down McLean's trousers, sliced off his genitals and put them into a plastic bag which he took home and disposed of the next day.

The police at one stage thought that the killer could have been a deranged surgeon. The manner in which McLean's genitals were removed seemed to be done by someone with years of surgical experience. Doctors at one stage found themselves under investigation.

On the night of Saturday 6 June 1962, MacDonald went to a wine saloon in Pitt Street, Sydney, where he met 37-year-old Patrick Joseph Hackett, a thief and derelict who had just recently been released from prison. They went back to MacDonald's new residence where they continued to drink alcohol. After a short period, Hackett fell asleep on the floor. MacDonald then got out a boning knife that he used in his delicatessen. He stabbed Hackett in the neck, the blow passing straight through. After the first blow, Hackett woke up and tried to shield himself, pushing the knife back into MacDonald's other hand and cutting it severely. MacDonald then unleashed a renewed attack, eventually striking the knife into Hackett's heart, killing him instantly. He continued to stab his victim until he had to stop for breath. Hackett's blood was splattered all over the walls and floor.

The knife having become blunted, MacDonald was unable to sever his victim's genitals and fell asleep. When he awoke the following morning he found himself lying next to the victim's body covered in sticky, drying blood. The pools of blood had soaked through the floorboards and almost on to the counter in his shop downstairs. He cleaned himself and went to a hospital to have the wound in his hand stitched. He told the doctor that he had cut himself in his shop. After cleaning up the blood, MacDonald dragged Hackett's corpse underneath his shop. Believing the police would soon come looking for his victim, he fled to Brisbane.

Three weeks later, neighbours noticed a putrid smell coming from the shop and called the health department, who in turn called the police. On 20 November 1962 police discovered the rotting corpse, which was too badly decomposed to be identified. An autopsy determined that the body was of someone in their forties, which tallied with records of the missing shop owner, Brennan (MacDonald's alias). In late July, the police had still made no connection between the case and the three previous Mutilator killings, and had profiled the killer as operating in Sydney's inner eastern suburbs, which were many miles distant from Concord.

After investigations, the victim was incorrectly identified as Brennan and a notice published in a newspaper obituary column. This was read by his former workmates at the local post office, who attended a small memorial service conducted by a local funeral director. At this time, MacDonald was living in Brisbane and then moved to New Zealand, believing that the police would still be looking for him. He felt the need to kill again, but for some reason he had to return to Sydney to do it. Returning to Sydney, he met former workmate John McCarthy, who said, "I believed you had died," at which MacDonald replied, "Leave me alone," and ran away, travelling to Melbourne soon after.

McCarthy went straight to the police. At first they did not believe him and accused him of having had too much to drink and he was told to go home and sleep it off. They even said that he was crazy. He went back again the next day and tried to explain what had happened, but they still didn't believe him. This persuaded McCarthy to go to the Daily Mirror newspaper where he spoke to crime reporter Joe Morris. McCarthy explained how he bumped into the "supposed to be dead" Brennan. The reporter saw the account as credible and filed a story under the headline "Case of the walking corpse" Publication forced the police to exhume the corpse. The fingerprints identified the body as belonging to Hackett and not MacDonald. Closer examination found that the body had several stab wounds and mutilation of the penis and testicles, potentially linking the crime to the notorious Mutilator.

Under questioning, MacDonald readily admitted to the killings, blaming them on an irresistible urge to kill. He claimed he was the victim of rape as a teenager, and had to disempower the victims chosen at random. A man with schizophrenia, MacDonald said that he heard voices in his head telling him that his victims were the corporal who raped him as a teenager.

14 notes

·

View notes