#named after one of the most influential movie stars of the 20th century

Text

sometimes i pull my life size skeleton out of his coffin and i set him up in the house b4 i go to bed so that the others can find him when they wake up

#spikes rambles#his name is skeleton btw#named after one of the most influential movie stars of the 20th century#skeleton#who played the most iconic roll in one of the best known films ever made#skeleton. in the 1959 classic house on haunted hill which also had some dude named vincent? idk

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

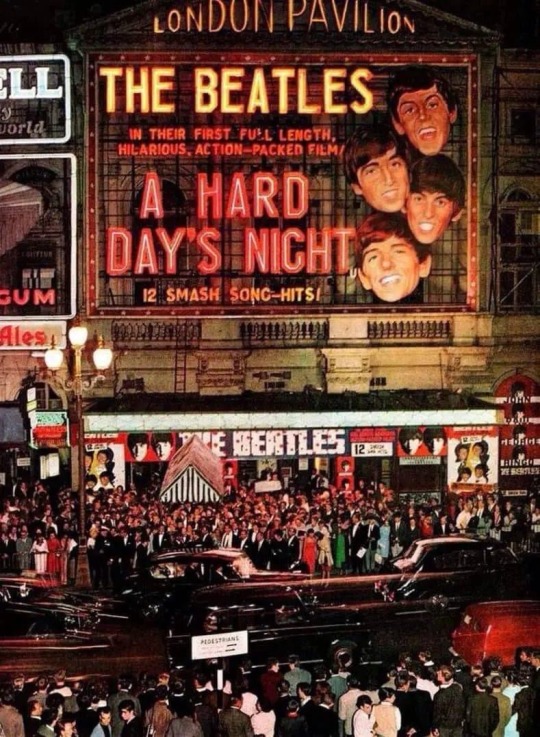

July 6, 1964 - The Beatles' first feature film, A Hard Day's Night, had its première at the London Pavilion.

A Hard Day's Night is a 1964 British musical comedy film directed by Richard Lester and starring the Beatles—John Lennon, Paul McCartney, George Harrison, and Ringo Starr—during the height of Beatlemania. It was written by Alun Owen and originally released by United Artists. The film portrays 36 hours in the lives of the group.

The film was a financial and critical success. Forty years after its release, Time magazine rated it as one of the all-time great 100 films. In 1997, British critic Leslie Halliwell described it as a "comic fantasia with music; an enormous commercial success with the director trying every cinematic gag in the book" and awarded it a full four stars.[The film is credited as being one of the most influential of all musical films, inspiring numerous spy films, the Monkees' television show and pop music videos. In 1999, the British Film Institute ranked it the 88th greatest British film of the 20th century.

The movie's strange title originated from something said by Ringo Starr, who described it this way in an interview with disc jockey Dave Hull in 1964: "We went to do a job, and we'd worked all day and we happened to work all night. I came up still thinking it was day I suppose, and I said, 'It's been a hard day ...' and I looked around and saw it was dark so I said, '... night!' So we came to A Hard Day's Night."

PLOT

Bound for a London show from Liverpool, the Beatles escape a horde of fans ("A Hard Day's Night"). Once they are aboard the train and trying to relax, various interruptions test their patience: after a dalliance with a female passenger, Paul's grandfather is confined to the guard's van and the four lads join him there to keep him company. John Lennon, Paul McCartney, George Harrison, and Ringo Starr play a card game, entertaining some schoolgirls before arriving at their desired destination ("I Should Have Known Better").

Upon arrival in London, the Beatles are driven to a hotel, only to feel trapped inside. They are tasked to answer numerous letters and fan mail in their hotel room but instead, they sneak out to party ("I Wanna Be Your Man", "Don't Bother Me", "All My Loving"). After being caught by their manager Norm (Norman Rossington), they return to find out that Paul's grandfather John (Wilfrid Brambell) went to the casino. After causing minor trouble at the casino, the group is taken to the theatre where their performance is to be televised. After rehearsals ("If I Fell"), the boys leave through a fire escape and dance around a field but are forced to leave by the owner of the property ("Can't Buy Me Love"). On their way back to the theatre, they are separated when a woman named Millie (Anna Quayle) recognizes John as someone famous but cannot recall who he is. George is also mistaken for an actor auditioning for a television show featuring a trendsetter hostess. The boys all return to rehearse another song ("And I Love Her") and after goofing around backstage, they play another song to impress the makeup artists ("I'm Happy Just to Dance with You").

While waiting to perform, Ringo is forced to look after Paul's grandfather and decides to spend some time alone reading a book. Paul's grandfather, a "villain, a real mixer", convinces him to go outside to experience life rather than reading books. Ringo goes off by himself ("This Boy" instrumental). He tries to have a quiet drink in a pub, takes pictures, walks alongside a canal, and rides a bicycle along a railway station platform. While the rest of the band frantically and unsuccessfully attempts to find Ringo, he is arrested for acting in a suspicious manner. Paul's grandfather joins him shortly after attempting to sell photographs wherein he forged the boys' signatures. Paul's grandfather eventually makes a run for it and tells the rest of the band where Ringo is. The boys all go to the station to rescue Ringo but end up running away from the police back to the theatre ("Can't Buy Me Love") and the concert goes ahead as planned. After the concert ("Tell Me Why", "If I Fell", "I Should Have Known Better", "She Loves You"), the band is taken away from the hordes of fans via helicopter.

From beatlesbible:

The première was attended by The Beatles and their wives and girlfriends, and a host of important guests including Princess Margaret and Lord Snowdon. Nearby Piccadilly Circus was closed to traffic as 12,000 fans jostled for a glimpse of the group.

“I remember Piccadilly being completely filled. We thought we would just show up in our limo, but it couldn't get through for all the people. It wasn't frightening - we never seemed to get worried by crowds. It always appeared to be a friendly crowd; there never seemed to be a violent face.”

~ Paul McCartney, Anthology

It was a charity event held in support of the Variety Club Heart Fund and the Docklands Settlements, and the most expensive tickets cost 15 guineas (£15.75).

After the screening The Beatles, the royal party and other guests including The Rolling Stones enjoyed a champagne supper party at the Dorchester Hotel, after which some of them adjourned to the Ad Lib Club until the early hours of the morning.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

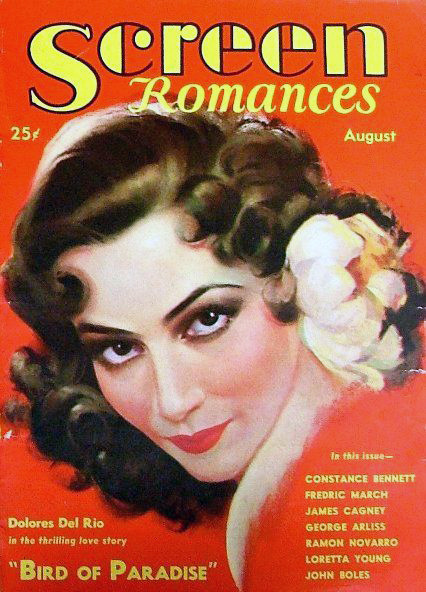

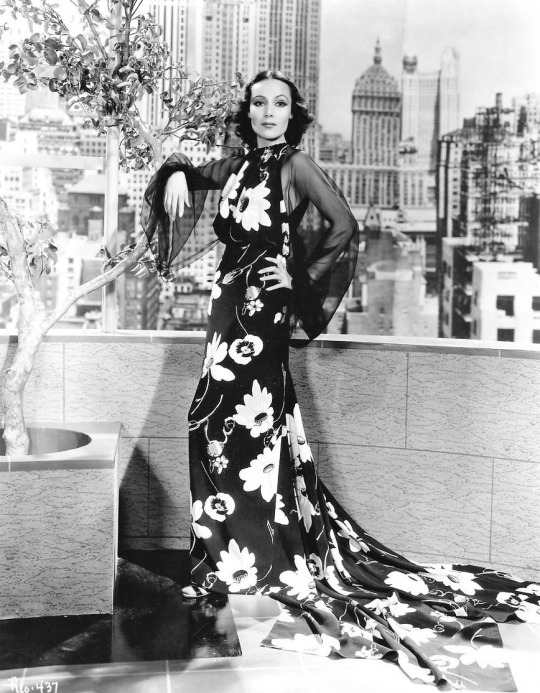

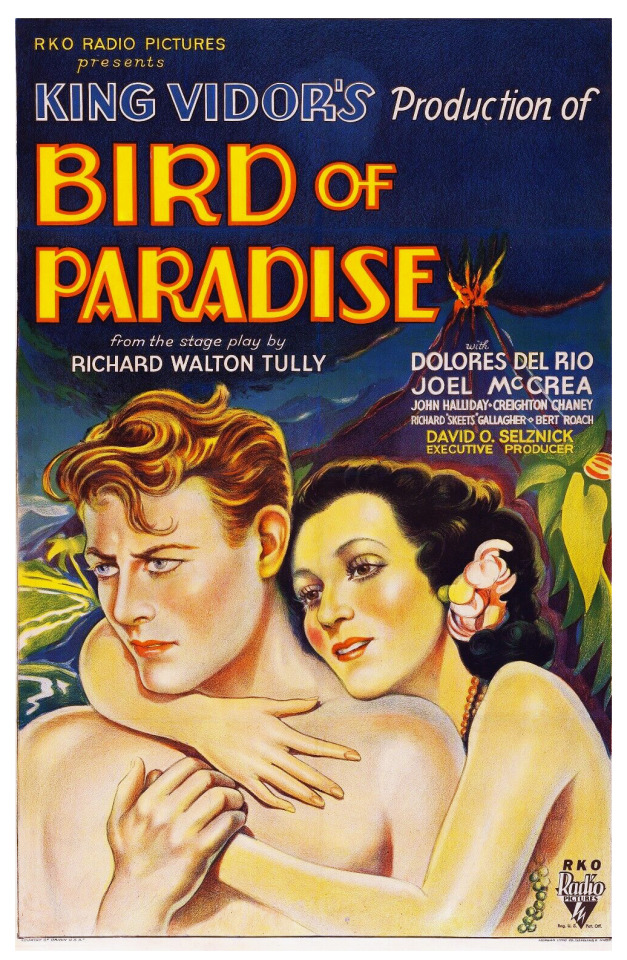

Dolores del Rio - Hollywood's First Latin Superstar

María de los Dolores Asúnsolo y López Negrete (born in Victoria de Durango, Durango on 3 August 1904), known professionally as Dolores del Río, was a Mexican actress whose career spanned more than 50 years. With her meteoric career in the 1920s/1930s Hollywood and great beauty, she is regarded as "Hollywood's First Latin Superstar."

Del Rio came from an aristocratic Mexican family whose lineage went back to Spain and the viceregal nobility. Her family lost all its assets during the Mexican Revolution. She developed a great taste for dance at a young age, which awakened in her when her mother took her to one of the performances of the Russian dancer Ana Pavlova.

In 1925, she met American filmmaker Edwin Carewe, an influential director at First National Pictures, who was in Mexico at the time. He convinced her to move to Hollywood. After a couple of years, United Artists became interested in her and signed her to a contract. Her career blossomed at the studio, and she made memorable films such as Ramona (1928) and Evangeline (1929). After her contract was terminated, she was hired by RKO Pictures ,then Warner Bros, and then 20th Century Fox.

Unfortunately, Latin stars had less opportunities in Hollywood then, and her career declined. She returned to her birth country, where she became one of the most important female figures in the Golden Age of Mexican cinema.

Del Río returned to Hollywood and made movies and TV shows. However, she continued to produce and star in Mexico in film and theater projects.

She died from liver failure at the age of 78 in Newport Beach, California. Her remains have been interred in the Rotonda de las Personas Ilustres in Mexico City since 2005.

Legacy:

Won the Silver Ariel Award (Mexican equivalent to the Oscars) for Best Actress three times: Las Abandonadas (1946), Doña Perfecta (1951), and El Niño y la niebla (1953); and was nominated two more times: La Otra (1946) and La Casa Chica (1949)

Awarded the Best Actress by the Instituto de Artes y Ciencias Cinematográficas de Mexico for Flor Silvestre (1943)

Named as one of the WAMPAS Baby Stars of 1926

Was the model of the statue of Evangeline in 1929 located in St. Martinville, Louisiana

Honored as one of the best dressed woman in America with the Neiman Marcus Fashion Award in 1952

Received a medal for her outstanding scenic work abroad from the Asociacion Nacional de Actores in 1957

Selected as the first woman to sit on the Cannes Film Festival jury, and even served as the Vice President, in 1957

Co-founded the Sociedad Protectora del Tesoro Artistico de México, responsible for protecting art and culture in México, in 1966

Given the Diosa de Plata Award by the Mexican Film Journalists Association twice: in recognition her contribution to Mexican film industry in 1965 and in commemoration of her 50-year career in 1975

Presented with a medal for her cultural contribution to the peoples of America by the Organization of American States in 1967

Was honored by Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes y Literatura and the Mexico's Screen Actors Guild in 1970 with a tribute titled Dolores del Rio in the Art, where her main portraits and a sculpture by Francisco Zúñiga were exhibited

Was a spokeswoman of UNICEF in Latin America in the 1970s

Received the Golden Ariel Honorific Award in 1975 for her contribution to Mexican cinema

Formed the union group "Rosa Mexicano", which provided a day nursery for the children of the members of the Mexican Actor's Guild in 1970

Helped found the Cultural Festival Cervantino in Guanajuato in 1972

Received the Mexican Legion of Honor in 1975

Received a diploma and a silver plaque for her work in cinema as a cultural ambassador by the Mexican Cultural Institute and the White House in 1978

Awarded the George Eastman Award, given by George Eastman House for distinguished contribution to the art of film in 1982

Has been the namesake of the Diosa de Plata (Dolores del Río) Award for the best dramatic female performance by the Periodistas Cinematográficos de México since 1983

Has murals painted on Hudson Avenue in Hollywood painted by the Mexican-American artist Alfredo de Batuc in 1990 and at Hollywood High School in 2002

Is the namesake of Teatro Dolores del Rio, built in 1992, in Durango

Chosen to be one of The Four Ladies of Hollywood, a sculpture at Hollywood-La Brea Boulevard in 1993

Realized a tribute by fashion designer John Galliano in his 1995 Fall/Winter collection, Dolores.

Stipulated that all her artworks be donated to the National Institute of Fine Arts and Literature of Mexico, for display in various museums in Mexico City, including the National Museum of Art, the Museum of Art Carillo Gil and the Diego Rivera & Frida Kahlo House-Studio

Included in a cameo in the Disney-Pixar animated movie Coco in 2017

Honored in three monuments in Mexico City: a statue located in the second section of Chapultepec Park, a bust located in the Parque Hundido, and another bust in the nursery that bears her name.

Honored with two streets named after her: Blvd. Dolores del Río, in Durango, Mexico, her hometown and Dolores del Rio Ave. in Mission, Texas

Honored with a Google Doodle on her 113th birthday in 2017

Has her star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame at 1630 Vine Street for motion picture

#Dolores Del Rio#Evangeline#Mexico#Latin#Latina#Hollywood's First Latin Superstar#Latin Actress#Mexican Actress#Mexicana#Silent Films#Silent Movies#Silent Era#Silent Film Stars#Golden Age of Hollywood#Classic Hollywood#Film Classics#Classic Films#Old Hollywood#Vintage Hollywood#Hollywood#Movie Star#Hollywood Walk of Fame#Walk of Fame#Movie Legends#Actress#hollywood actresses#hollywood icons#hollywood legend#movie stars#1900s

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Robe (1953)

Henry Koster’s The Robe, distributed by 20th Century Fox, appeared near the beginning of an era where religious epics and sword-and-sandal films became massive box office draws worldwide. Cecil B. DeMille’s Samson and Delilah (1949) and Mervyn LeRoy’s Quo Vadis (1951) had already laid the foundation on which Koster’s film, adapting Lloyd C. Douglas’ novel of the same name, would find its success. Despite The Robe being highly influential in Hollywood and becoming the highest-grossing film of 1953, the likes of DeMille’s The Ten Commandments (1956) and William Wyler’s Ben-Hur (1959) overtook it artistically and financially – no shame there, as those are two far superior films.

So what is The Robe’s claim to movie history beyond its initial theatrical earnings? When The Robe first came to theaters, 20th Century Fox advertised it as the first film ever made in CinemaScope. Created by Fox’s president, Spyros P. Skouras, CinemaScope was a format in which a widescreen camera lens contracted its widescreen shots onto regular 35mm film and, during theatrical projection, another lens would de-contract the image from the 35mm film in order to project a widescreen format. Theaters would only need to make minor, inexpensive modifications to their projectors in order to show a film in true CinemaScope, a 2:55:1 widescreen aspect ratio. Almost all other films were shot in the Academy ratio at the time (1.37:1, close to the 4:3 ratio – think: black bars on the left- and right-hand sides of a widescreen monitor – seen on many older standard computer monitors and televisions). With increasing competition from television, Fox executives believed CinemaScope could be a way to lure audiences back into theaters. Despite this overreaction from Fox’s executives (as well as the other major Hollywood studios), the legacy of CinemaScope’s innovation is still apparent today. Seven decades later, widescreen formats, not the Academy ratio, are the default in film and television.

Walking through the markets of Rome, returning Roman Empire tribune Marcellus Gallio (Richard Burton) reunites with his childhood sweetheart, Diana (Jean Simmons), who is now promised to Marcellus’ rival, Caligula (an always-sneering Jay Robison). Not long after, Marcellus – out of pettiness rather than financial sense – outbids Caligula for the Greek slave, Demetrius (Victor Mature). Marcellus immediately frees Demetrius, but Demetrius thinks of himself as honor-bound to stay by Marcellus. Elsewhere, an incensed Caligula reassigns Marcellus to Palestine – which, to the film’s Roman characters, might as well be the armpit of the Roman Empire. Marcellus and Demetrius go to Jerusalem, where they witness a man named Jesus enter the city, heralded by crowds of Jews greeting him with palms. Several days later, Judean Governor Pontius Pilate (Richard Boone) orders Marcellus to crucify Jesus on Calvary. Marcellus executes the order but, during and after the crucifixion, witnesses and experiences supernatural events. Demetrius, who has become a follower of Jesus during that week, obeys Marcellus when he asks him to fetch Jesus’ robe. The moment Marcellus dons the robe, he suffers something like a seizure. He falls out with Demetrius, and spends the rest of the film reckoning with his conscience over his role in Jesus’ crucifixion.

The film also stars Michael Rennie as Peter, Dean Jagger as Justus, Torin Thatcher as Senator Gallio, and Ernest Thesiger as Emperor Tiberius. Michael Ansara and Donald C. Klune are both uncredited as Judas Iscariot and Jesus, respectively.

The Robe has the misfortune of peaking in the first half. The adapted screenplay from Gina Kaus (1949’s The Red Danube), Albert Maltz (one of the blacklisted Hollywood Ten; 1950’s Broken Arrow), and Philip Dunne (1941’s How Green Was My Valley) is at its most interesting whenever Marcellus and Demetrius find themselves at odds with the other. In the scenes they share together, that happens often. But when Demetrius disappears after their disagreement over Jesus’ robe midway through, the film begins to sag with no foil for Burton to play off of.

For the entirety of this film, Richard Burton’s acting is overwrought. Burton, who had just arrived in Hollywood the year before to star in My Cousin Rachel (1952), is leaning too deeply into his theatrical roots here. His grandiose exclamations, stiff facial acting, and inconsistent line delivery result in a performance that is easily the weakest part of this film (Jean Simmons is also guilty, to a far lesser degree, of these same flaws in her performance). The Robe requires Burton’s Marcellus to undergo a spiritual conversion – becoming an adherent of Jesus despite following orders to crucify him, a developmental arc more dramatic than any other character’s in this film. Burton’s inability to convincingly sell this conversion (the stoic masculine tension, which some will interpret as coded homosexuality, between Burton’s Marcellus and Mature’s Demetrius does not help) weakens the film’s spiritual power.

Instead, it is Mature who is The Robe’s reliable scene-stealer. Mature, at one time likened to a “miniature Johnny Weissmuller”, has the classical Greek physique that, frankly, Burton does not. And in contrast to Burton at this time in their careers, Mature was more capable of a nuanced performance, as evidenced in his roles as Doc Holliday in My Darling Clementine (1946) and Nick Bianco in Kiss of Death (1947). As Demetrius, his soul hardened through his enslavement, there remains hope for a life free from the yoke of the Roman Empire and its callous slave masters. One sees it in his face during Holy Week, culminating with seeing Jesus dying on the cross. His faith is there, too, during a torture scene upon his return to Rome and an encounter with Peter. Amid miracles and cruelties, Mature’s Demetrius is simply the most compelling character of The Robe and the viewer – through Mature’s performance, especially in contrast to those of Jean Simmons and Richard Burton’s – can discern his genuine turn of faith. The Robe’s failure to showcase this inner awakening more believably is the fault of its two central actors and its screenplay; Mature’s performance and Demetrius’ characterization are all that saves the narrative.

One aspect of Christianity that The Robe captures confusingly (and oxymoronically) is the insignificance of Judea and the prominence of early Christianity in Rome in the time immediately following Jesus’ crucifixion. Oftentimes in Biblical epics, Judea is a centerpiece of the Roman Empire when, in truth (and in The Robe), it was a relative backwater. By Caligula’s reign between 37 and 41 CE, Christianity almost certainly would not have had a substantial presence in Rome at that time. So while Caligula would probably see Christianity as a threat, the film’s decision to treat the early Christians as a clear and present danger to his rule and the Roman state religion is the film’s glaring historical inaccuracy. The Robe – the book and the film – muddies the timeline from Jesus’ crucifixion to the film’s final scene in Caligula’s court. The relative suddenness of the Roman Empire seeing the early Christians as a very minor cult into becoming an Empire-wide menace is difficult to reconcile.

With few other post-silent film era Biblical epics as a guide, The Robe helps set the aesthetic of its fellow Biblical epics and sword-and-sandals movies going forward through its costumes and production design. The work of costume designers Charles LeMaire (1950’s All About Eve, 1956’s Carousel) and Emile Santiago (1952’s Androcles and the Lion, 1958’s The Big Country) is resplendent, regardless of either the Roman or Judean setting. Art directors Lyle R. Wheeler (1939’s Gone with the Wind, 1956’s The King and I) and George Davis (All About Eve, 1963’s How the West Was Won) and set decorators Walter M. Scott (All About Eve, 1965’s The Sound of Music) and Paul S. Fox (The King and I, 1963’s Cleopatra) all make full use of the CinemaScope format and color to enliven the scenery – a sumptuous visual treat for the viewer, and, to reiterate, setting a standard that the crew of The Ten Commandments and Ben-Hur both would study and surpass.

Of all of 20th Century Fox contracted stalwarts behind the camera, composer Alfred Newman was the studio’s most important figure. If Fox’s executives needed a composer to craft a score for what they would consider would be their prestige motion picture of the year, Newman – who composed the original 20th Century Fox fanfare and its CinemaScope extension (the extension, which is now inextricable from the fanfare, was first introduced in 1954’s River of No Return) – was almost always their first choice.

youtube

In one of Newman’s finest scores of his career, it is his choral compositions, with incredible help from his longtime choral supervisor Ken Darby, that form the score’s emotive spine. Jesus’ motif, shared between wordless choir and strings, appears almost immediately, in the opening seconds of the “Prelude”. During the many invocations of a Messiah before Jesus’ first physical appearance in The Robe, his motif shifts, changes form, and modulates – imparting not spiritual comfort or devotion, but a mysteriousness and otherworldliness. When Jesus (whose face we never see) first appears in Jerusalem on Palm Sunday, the cue “Passover/Palm Sunday” represents one of the rare juxtapositions of the brass-heavy martial music representing the Roman presence in Judea and Jesus himself. The modulation to a major key at 1:22 in this cue, with festive percussion, also includes one of the only instances of celebratory choral music in the score. Jesus’ motif in “Passover/Palm Sunday”, appears at 2:26 – cementing his (and Christianity’s) association with the cue, and appearing as the only instance in which one might consider this motif triumphant.

Choruses, which Western viewers so often associate in religious movies as angelic musical devices, become mournful in “The Crucifixion” – arguably the standout cue of Newman’s score. Even though one might be well aware of Jesus’ death and can anticipate a turn in the music (starting moments earlier in “The Carriage of the Cross”), it is startling to hear Newman’s composition change so rapidly. But it is in these several minutes depicting Jesus’ final moments that Newman, with modifications to his harmonies and orchestration, transforms Jesus’ motif to evoke its tragic dimensions. It is magnificent scoring from Newman, and this is not even mentioning his wonderful demarcation of Roman and Judean identities through his score.

In a film about faith – how it comforts, destroys, heals, and vexes – one wishes that the characterization of The Robe’s supposed lead characters in Marcellus and Diana could feel more plausible. The film’s final scene, possibly allegorizing of screenwriter Albert Maltz’s travails as a blacklisted figure in Hollywood, is decently powerful, but it needs far more storytelling support from numerous scenes preceding it.

As it is, the film’s expressive power lies within Demetrius and Victor Mature’s performance. So how fortunate that, because Fox also wanted to make a sequel to The Robe even before it finished production, Mature also signed a contract to appear in a sequel. Nine months after The Robe made its theatrical debut, Victor Mature starred in Demetrius and the Gladiators, directed by Delmer Daves and also seeing Michael Rennie and Jay Robinson reprise their roles as Peter and Caligula, respectively. Though it did not top the box office for that year like The Robe did, Demetrius and the Gladiators was a financial boon for Fox.

With Hollywood’s major studios always ready to respond to the box office successes of their rivals, The Robe helped make possible the decade of Biblical and sword-and-sandals epics to come – and the required viewings for many a Sunday School student in the years hence. These films were Studio System Hollywood in full maximalism, adopting human and tactile scales seldom seen today.

Yet outside of churchgoers, The Robe – for its CinemaScope and genre-specific innovations – has seen its standing slip gradually over the years, no thanks to the reputations of better movies of this tradition and, regrettably, decisions to keep 20th Century Fox’s valuable past under lock and key. 20th Century Fox’s refusal to distribute their classic films more often and more widely – before and after the studio’s 2019 takeover by the Walt Disney Company (and post-takeover, I believe the situation is now worse) – is resulting in films like The Robe slip through the proverbial cracks of film history, sights unseen for younger film buffs. That is unfortunate, especially as The Robe, almost incidentally (and no matter my aforementioned criticisms of the work itself), continues to quietly wield, by virtue of being the first CinemaScope film, a remarkable influence over cinema worldwide.

My rating: 6/10

^ Based on my personal imdb rating. My interpretation of that ratings system can be found in the “Ratings system” page on my blog. Half-points are always rounded down.

For more of my reviews tagged “My Movie Odyssey”, check out the tag of the same name on my blog.

#The Robe#Henry Koster#Richard Burton#Jean Simmons#Victor Mature#Michael Rennie#Jay Robinson#Dean Jagger#Torin Thatcher#Richard Boone#Michael Ansara#Leon Shamroy#Alfred Newman#Ken Darby#Charles LeMaire#Emile Santiago#Lyle R. Wheeler#George Davis#TCM#My Movie Odyssey

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The last of Oklahoma's "Five Moons" has set.

Marjorie Tallchief — one of the five Native American ballerinas from Oklahoma who rose to global fame in the 20th century — died Nov. 30 at her home in Delray Beach, Florida.

She was 95.

"Aunt Margie was one of the most humble, sincere and gracious people I have ever known," Russ Tallchief, Marjorie Tallchief's nephew and a writer and dancer based in Oklahoma City, told The Oklahoman.

"She told me that a great opportunity will present itself to every person at some point in time, but you have to be ready for that opportunity, just as she was when she stepped onto the world stage to represent her family, her Osage Nation and the United States as a world renowned ballerina.

From her start dancing in her father’s movie theater with her sister in their Oklahoma hometown, Tallchief performed around the world, achieving national and international acclaim.

The younger sister of famed fellow prima ballerina Maria Tallchief, Marjorie Louise Tallchief was born in Oct. 19, 1926, in Denver, Colorado, during a family vacation. Her parents were Alexander Joseph Tall Chief, a member of the Osage Nation, and his wife, Ruth Porter Tall Chief.

Her paternal great-grandfather had helped negotiate with the U.S. government for oil revenues that brought the Osage Nation vast wealth, and she grew up in Fairfax until her family moved to California when she was a girl so that she and her sister could further their ballet training.

She studied under prominent choreographers Ernest Belcher, Bronislava Nijinska and David Linchine, according to the Oklahoma Historical Society.

She accepted a position of leading soloist in the Original Ballet Russe, a traveling company that took ballet to small towns across America. She went on to perform with the Grand Ballet du Marquis de Cuevas and the Chicago Opera Ballet.

She joined the Paris Opéra Ballet in 1957, and she was the first American ever to become première danseuse étoile, or "star dancer," the highest rank a performer can reach in the legendary company.

In 1958, she also became the first American ballerina since World War II to perform in Moscow's Bolshoi Theatre, according to the Oklahoma Hall of Fame, which inducted Tallchief in 1991.

Tallchief performed for U.S. Presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson, as well as for French President Charles de Gaulle.

"The importance of Marjorie Tallchief to Oklahoma's artistic and cultural history cannot be overstated. As an Osage and native of Fairfax, she achieved success previously unthinkable in the world of ballet for someone of her background," Oklahoma Historical Society Executive Director Trait Thompson told The Oklahoman.

Artistic career continued after her retirement from the stage

Best known for her roles in ballets like "Romeo and Juliet," "Giselle" and "Idylle" — the latter was choreographed by her husband, George Skibine — Tallchief was prima ballerina with New York's Harkness Ballet from 1964 until 1966, when she retired from the stage.

She subsequently taught at the Dallas Civic Ballet Academy and acted as a dance director for the Dallas Ballet. In 1980, she helped her sister found and taught at the Chicago City Ballet.

From 1989 to 1993, Tallchief worked as director of dance at the Harid Conservatory in Boca Raton, Florida. She retired to Delray Beach, Florida, where she was a fixture at local yoga and Pilates studios well into her 90s.

She was presented with a distinguished service award from the University of Oklahoma in 1992 and named one of the “50 Most Influential Oklahomans of the 20th Century” in 2000.

Tallchief married to Skibine, an artistic director, ballet master and choreographer, in 1947. They had twin sons and remained married until his death in 1981 at age 60.

Tallchief is survived by her sons, Alexander and George Skibine, and her grandchildren, Alexandre, Nathalie, Adrian and Trevor Skibine.

Five Moons leave a lasting legacy

Tallchief was the last surviving member of the "Five Moons," five Native American dancers from Oklahoma who took the international ballet world by storm in the 20th century. Along with Marjorie Tallchief, the Five Moons included her sister, Maria Tallchief (1925-2013), Yvonne Chouteau (1929-2016), Moscelyne Larkin (1925-2012) and Rosella Hightower (1920-2008).

The moniker “Five Moons” evolved from the Oklahoma Indian Ballerina Festivals that took place in 1957 and 1967 to celebrate the 50th and 60th anniversaries of Oklahoma statehood. The 1967 festival included a ballet created by Cherokee composer Louis Ballard Sr. called "The Four Moons" performed by four of the five ballerinas —Maria Tallchief had retired from performing — featuring solos honoring each dancer's heritage.

Oklahoma Native American artist Jerome Tiger (Muscogee and Seminole) created a painting for the program cover titled "The Four Moons." Chickasaw painter Mike Larsen went on to depict the Five Moons in a state Capitol mural titled "Flight of Spirit," which was dedicated in 1991.

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Today we remember the passing of Marlon Brando who Died: July 1, 2004 at Ronald Reagan UCLA Medical Center in Los Angeles, California

Marlon Brando Jr. (April 3, 1924 – July 1, 2004) was an American actor and film director with a career spanning 60 years, during which he won the Academy Award for Best Actor twice. He is regarded as arguably the greatest and most influential actor in 20th-century film. Brando was also an activist for many causes, notably the civil rights movement and various Native American movements. Having studied with Stella Adler in the 1940s, he is credited with being one of the first actors to bring the Stanislavski system of acting and method acting, derived from the Stanislavski system, to mainstream audiences.

He initially gained acclaim and an Academy Award nomination for reprising the role of Stanley Kowalski in the 1951 film adaptation of Tennessee Williams' play A Streetcar Named Desire, a role that he originated successfully on Broadway. He received further praise, and an Academy Award, for his performance as Terry Malloy in On the Waterfront, and his portrayal of the rebellious motorcycle gang leader Johnny Strabler in The Wild One proved to be a lasting image in popular culture. Brando received Academy Award nominations for playing Emiliano Zapata in Viva Zapata! (1952); Mark Antony in Joseph L. Mankiewicz's 1953 film adaptation of Shakespeare's Julius Caesar; and Air Force Major Lloyd Gruver in Sayonara (1957), an adaptation of James Michener's 1954 novel.

The 1960s saw Brando's career take a commercial and critical downturn. He directed and starred in the cult western One-Eyed Jacks, a critical and commercial flop, after which he delivered a series of notable box-office failures, beginning with Mutiny on the Bounty (1962). After ten years of underachieving, he agreed to do a screen test as Vito Corleone in Francis Ford Coppola's The Godfather (1972). He got the part and subsequently won his second Academy Award in a performance critics consider among his greatest. He refused the award due to mistreatment and misportrayal of Native Americans by Hollywood. The Godfather was one of the most commercially successful films of all time, and alongside his Oscar-nominated performance in Last Tango in Paris, Brando reestablished himself in the ranks of top box-office stars.

After a hiatus in the early 1970s, Brando was generally content with being a highly paid character actor in supporting roles, such as Jor-El in Superman (1978), as Colonel Kurtz in Apocalypse Now (1979), and in The Formula (1980), before taking a nine-year break from film. According to the Guinness Book of World Records, Brando was paid a record $3.7 million ($16 million in inflation-adjusted dollars) and 11.75% of the gross profits for 13 days' work on Superman.

Brando was ranked by the American Film Institute as the fourth-greatest movie star among male movie stars whose screen debuts occurred in or before 1950. He was one of only six actors named in 1999 by Time magazine in its list of the 100 Most Important People of the Century. In this list, Time also designated Brando as the "Actor of the Century."

On July 1, 2004, Brando died of respiratory failure from pulmonary fibrosis with congestive heart failure at the UCLA Medical Center. The cause of death was initially withheld, with his lawyer citing privacy concerns. He also suffered from diabetes and liver cancer. Shortly before his death and despite needing an oxygen mask to breathe, he recorded his voice to appear in The Godfather: The Game, once again as Don Vito Corleone. However, Brando recorded only one line due to his health, and an impersonator was hired to finish his lines. His single recorded line was included within the final game as a tribute to the actor. Some additional lines from his character were directly lifted from the film. Karl Malden—Brando's co-star in three films, A Streetcar Named Desire, On the Waterfront, and One-Eyed Jacks—spoke in a documentary accompanying the DVD of A Streetcar Named Desire about a phone call he received from Brando shortly before Brando's death. A distressed Brando told Malden he kept falling over. Malden wanted to come over, but Brando put him off, telling him there was no point. Three weeks later, Brando was dead. Shortly before his death, he had apparently refused permission for tubes carrying oxygen to be inserted into his lungs, which, he was told, was the only way to prolong his life.

Brando was cremated, and his ashes were put in with those of his good friend Wally Cox and another longtime friend, Sam Gilman. They were then scattered partly in Tahiti and partly in Death Valley. In 2007, a 165-minute biopic of Brando for Turner Classic Movies, Brando: The Documentary, produced by Mike Medavoy (the executor of Brando's will), was released.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

RWRB Study Guide: Chapter 2

Hi y’all! I’m going through Casey McQuiston’s Red, White & Royal Blue and defining/explaining references! Feel free to follow along, or block the tag #rwrbStudyGuide if you’re not interested!

Cakegate (21): Reference to Watergate, a political controversy from the 1970s; the Watergate Scandal still holds quite a bit of prevalence in American culture. (More)

Situation Room (22): the John F. Kennedy Conference Room, AKA “the Situation Room”, is a secure conference room in the basement of the West Wing. (More)

The Sun (22): A British tabloid.

Deputy Chief of Staff (Zahra’s position, 23): The Deputy Chief of Staff is the top aide to the president’s top aide, and is responsible for ensuring that everything runs smoothly within the bureaucracy of the White House.

Howard (24): Howard University is a historically Black university just outside of Washington DC. It opened in 1867, just after the end of the American Civil War and is known for its STEM programs and law school. (More)

Equerry (24): A personal attendant to a member of the royal family (historically, someone who was in charge of their horses).

ITV This Morning (26): A British daytime cable show

SNL (26): Saturday Night Live, an American sketch comedy TV show that brings in a new celebrity host every week.

People (27): An American magazine that covers celebrity gossip.

Clintons (27): Bill Clinton has one child, Chelsea Clinton, and her parents worked to shield her from the press during his presidency.

Sasha and Malia (27): President Obama’s daughters, who were pre-teens and teenagers during his White House years and have faced rather invasive press coverage since.

Patsy Cline (28): An American singer from the 1950s, considered one of the most influential vocalists of the 20th century and one of the firsts artists to cross from country music to pop, (Listen here and here)

Op-Ed (28): “Opposite the Editorial”; a one-page piece of writing for a magazine or other news piece that is not associated with the views of the publication.

Essential Oils, Cabin in the Vermont Wilderness, LLB Vests, Patchouli (29): These are all markers that Nora’s parents are outdoorsy, maybe to the extent of being a bit detached from the “real world”.

Essential Oils: These are oils that can help people relax or create a positive atmosphere, but have little to no health benefits beyond that. Many people believe they can help cure serious or chronic illnesses.

Cabin in the Vermont Wilderness: Vermont’s wooded areas would be a very nice place for a cabin

LLBean vests: LLBean is a brand that sells high-end outdoors clothes

Patchouli: A type of essential oil

Mutton Pie (30): A small, double-crust meat pie native to Scotland but common throughout the UK

Oxford (30): Oxford University is the oldest university in the English-speaking world, and with a 17% acceptance rate in 2017, it is an incredibly difficult school to get into. For American applicants, they require a 3.7 GPA (based on a 4.0 system) and a 32/36 on the ACT. (More)

Eton (31): A posh boarding school for boys 13-18, founded in 1440. It is one of the most prestigious schools in the world.

Great Expectations (31): a 1860-61 novel by Charles Dickens, where a young boy rises above a lowly birth to be “worthy of” a rich girl he falls in love with, (More)

Khakis vs. Chinos (32): Chinos are tighter than khakis and tend to be a bit more dressy. (More)

Gap vs. J. Crew (32): Gap is a relatively inexpensive brand; J. Crew is a more expensive alternative.

SeaWorld San Antonio (32): SeaWorld is a theme park/aquarium known in the past ten years or so for inhumane treatment of its animals.

Walrus Mustache (32): A thick, bushy mustache that falls over the wearer’s mouth. (More)

Land Rover (33): A British brand of car that offers only premium and luxury sport vehicles.

Shaan (33): Hindi name meaning “Pride”.

Aston Martin (33): A sports car favored by James Bond.

Kensington Palace (33): A relatively modest palace surrounded by Kensington Gardens, the traditional home of royal children.

Millionaire who wants to hunt you... (35): A reference to the short story “The Most Dangerous Game”, in which a rich man lures the protagonist to his private island and hunts him for sport.

Texas Panhandle (35): A rural area of northern Texas.

Waterboarded (36): Tortured; this is a reference to America’s history of torturing people in Guantanamo Bay.

Helados (37): Fruit-flavored ice cream bars from Mexico.

Nate Silver (38): American statistician and writer who created an algorithm to predict baseball players’ future success. He has more recently switched to highly accurate political predictions.

GW (38): George Washington University, a college in Washington DC where Alex goes to school.

Data Czar (39): A position in a company where the person who holds it manages that company’s data and reports directly to its top management.

PPOs (39): Private Patrol Officers or bodyguards

Cornettos (39): A British ice cream cone with nuts and chocolate, similar to an American drumstick.

Signet ring (40): A ring with the king’s seal; traditionally that seal would be pressed into wax and would serve as a substitute for the king’s signature. It signifies royal power

Beans and white toast (41): This is... a genuine British breakfast. Just plain beans and white toast. Beans are a staple in both Mexican and Texan/Tex-Mex foods, but they are typically heavily seasoned.

Yellow pill (41): From what I could find, this could be a pill used to deal with anxiety/symptoms of anxiety, such as Clonazepam.

Jolly old England (41): A very English way to refer to England.

Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust (44): A specialist cancer treatment hospital in London.

Alliance Starbird (44): The symbol of the Rebel Alliance in the Star Wars movies.

Caipirinhas (50): Brazil’s national cocktail; it is made in large batches and contains a sugar-based hard liquor, sugar, and lime.

Pancreatic cancer (51): A type of cancer that is typically not caught until it has progressed to the point of being incurable. (More)

-------

If there’s anything I missed or that you’d like more on, please let me know! And if you’d like to/are able, please consider buying me a ko-fi? I know not everyone can, and that’s fine, but these things take a lot of time/work and I’d really appreciate it!

Chapter 1 // Chapter 3

#rwrb study guide#rwrb#red white and royal blue#henry fox mountchristen windsor#henry fox mountchristen windsor x alex claremont diaz#alex claremont diaz#bea fox mountchristen windsor#nora holleran#june claremont diaz#pez okonjo#the white house trio#super six#study guide#casey mcquiston#FirstPrince

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

Film Allusions in Crimson Peak

Hi, all! So because I am deep in my horror movie feels at present and, as horror is a genre that some of you are new to/unfamiliar with, want you all to have some more context for Crimson Peak as an intertextual Gothic pastiche, I thought make a little list of films (mostly horror) that CP references, alludes to, or visually echoes (other than Jane Eyre or any iteration of “Bluebeard,” that is). This list is certainly not exhaustive, but I hope will give you a starting place at understanding the scale of the intertextual web this movie is weaving (also maybe give you some movie recs if you’re into horror/classic cinema. I’ll try to include links to films in the public domain).

Nosferatu (1922) and other early 20th century cinema

Del Toro makes use of a lot of the aesthetics and techniques of film from the late Victorian period/early 20th century (appropriate since Crimson Peak is set in the 1890s - incidentally one of the peaks of Gothic literature). One of these is iris shots/iris transitions (shown above in this screenshot from Nosferatu). Iris transitions are when a circular black mask over the shot shrinks, closing the picture to a black screen (very common in early horror film and 1920s cartoons, ie Betty Boop). If you’d like some very iconic, silent vampire cinema, you can watch Nosferatu here at archive.org for free.

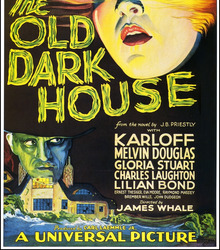

The Old Dark House (1932) | Watch free on Archive.org

Seeking shelter from a storm, five travelers are in for a bizarre and terrifying night when they stumble upon the Femm family estate.

A trope codifier for the haunted house movie, complete with oodles of Gothic weirdness, including those ooky spooky, co-dependent Femm siblings.

Rebecca (1940) | Watch free on Archive.org

A self-conscious bride is tormented by the memory of her husband's dead first wife.

Based on Daphne Du Maurier’s novel of the same name (itself heavily based on Jane Eyre), this Gothic variation on “Bluebeard” was Alfred Hitchcock’s first American film, won two Academy Awards, and is still considered one of the best psychological thrillers of all time. Features an overbearing female figure who directly interferes with our protagonist’s marriage to her, er, Prince Charming in the form of a Sapphic housekeeper obsessed with keeping the memory of the first Mrs. De Winter alive.

Notorious (1946) | Watch free on Youtube

A woman is asked to spy on a group of Nazi friends in South America. How far will she have to go to ingratiate herself with them?

Don’t drink the tea! Also, butterfly-backed chairs. Allll the butterfly-backed chairs.

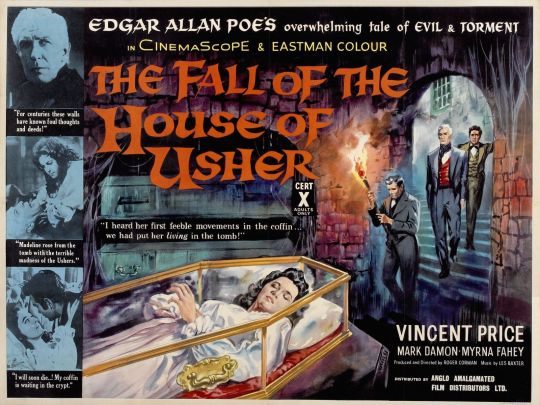

The Fall of the House of Usher (1960)

Upon entering his fiancée's family mansion, a man discovers a savage family curse and fears that his future brother-in-law has entombed his bride-to-be prematurely.

Two prongs here: Crimson Peak is very much playing with Edgar Allan Poe’s short story (incest siblings! Gothic manors sinking into the earth!) and evoking a particular aesthetic associated with a number of 1960s/70s “schlock” Gothic horror films like those made by Roger Corman who applied his use of vivid color and psychedelic surrealism to a number of Poe’s works.

AESTHETIC!!!!! Speaking of aesthetic excess...

The Brides of Dracula (1960) and other Hammer Horror films

Vampire hunter Van Helsing returns to Transylvania to destroy handsome bloodsucker Baron Meinster, who has designs on beautiful young schoolteacher Marianne.

Known for a series of Gothic horror films made during the 1950s - 1970s featuring well-known characters like Count Dracula, Baron Frankenstein, and The Mummy, Hammer film productions hooked audiences with its use of vivid color, gore, sexy damsels in nightgowns, sexy women with fangs, sexy mummy girls, sexy... you get the idea. It left an indelible aesthetic mark on horror cinema since (including Crimson Peak). Also famous for catapulting the careers of Christopher Lee and Peter Cushing or, as you might know them, Count Dooku and Grand Admiral Tarkin from Star Wars.

The Innocents (1961)

A young governess for two children becomes convinced that the house and grounds are haunted.

Frequently listed as one of the best horror films of all time, The Innocents (one of Del Toro’s direct inspirations -- clock the nightgown in the screencap) is a loose adaptation of Henry James’ seminal Gothic novella The Turn of the Screw.

So many more under the cut...

The Leopard (1963)

The Prince of Salina, a noble aristocrat of impeccable integrity, tries to preserve his family and class amid the tumultuous social upheavals of 1860's Sicily.

Another of Del Toro’s direct intertexts, which influenced Crimson Peak’s party scenes.

Suspiria (1977), the films of Mario Bava, and giallo cinema

An American newcomer to a prestigious German ballet academy comes to realize that the school is a front for something sinister amid a series of grisly murders.

A cult horror classic, Italian director Dario Argento’s Suspiria plays fast and loose with Gothic horror and fairy tale tropes, making for a slasher film quite unlike any other. Notable for its dreamlike surrealism, use of highly-stylized colorization, and sheer amounts of gore, Suspiria remains one of the most aesthetically influential horror films of all time and, looking at screenshots, you can maybe see its visual influence on films like Crimson Peak:

Guillermo Del Toro has also cited Mario Bava, another of the key figures in the golden age of Italian horror, as inspiration for his use of color and set design in Crimson Peak.

From Bava’s Black Sabbath (1963):

From Blood and Black Lace (1964):

Bava’s film, Blood and Black Lace, belongs to the giallo genre, which refers (at least, in English-speaking countries) to (largely 1970s) Italian horror thrillers/slashers notorious for their combination of intense, stylized violence and eroticism. Very much a precursor to the American slasher film.

The Shining (1980)

A family heads to an isolated hotel for the winter where an evil spiritual presence influences the father into violence, while his psychic son sees horrific forebodings from both past and future.

As film that also loosely adapts “Bluebeard,” it’s perhaps unsurprising that there are so many allusions to Stanley Kubrick’s adaptation of Stephen King’s novel of the same name in Crimson Peak.

And, man, does it have it all! Snowed in, Gothic entrapment! Threats of domestic abuse! Secrets locked away in forbidden rooms! Ghosts! So many ghosts!

Ghosts in the bathtub!

Ludicrously enormous amounts of blood! Innocent waifs with the ability to commune with the dead! Intrepid third parties who heroically make an attempt to reach the isolated Gothic hellscape to help our damsel in distress only to get immediately merc’d! It’s all here, y’all.... except the incest, of course.

Flowers in the Attic (1987)

Children are hidden away in the attic by their conspiring mother and grandmother.

Ok, this is something of a cheat, as Crimson Peak is alluding more to V.C. Andrews’ infamous novel of the same name, not the 1987 film (which is an abysmally terribly adaptation and hilariously bad flick). Anyway, abused siblings are locked away in an attic... and... well... things get all... Sharpe family values, if you know what I mean.

Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1992)

The centuries old vampire Count Dracula comes to England to seduce his barrister Jonathan Harker's fiancée Mina Murray and inflict havoc in the foreign land.

If you liked Crimson Peak, I think you’ll enjoy this too, as, like CP, this movie is a sincere horror film, but also a pastiche/celebration of the Gothic and vampire cinema. It’s visually sumptuous and very high-energy (if you didn’t like CP or Moulin Rouge!, this one is probably not for you).

Sleepy Hollow (1999)

Ichabod Crane is sent to Sleepy Hollow to investigate the decapitations of three people, with the culprit being the legendary apparition, The Headless Horseman.

This is another one that, if you liked CP, you might enjoy. Based on Washington Irving’s "The Legend of Sleepy Hollow,” Tim Burton’s film evokes a number of genres and horror aesthetics, most notably the Gothic horror flicks of the 1950s/60s, to create a kind of Hammer Horror film for American Gothic.

The Devil’s Backbone (2001) and Del Toro’s other films

After Carlos -- a 12-year-old whose father has died in the Spanish Civil War -- arrives at an ominous boys' orphanage, he discovers the school is haunted and has many dark secrets that he must uncover.

Crimson Peak is not Guillermo Del Toro’s first foray into Gothic horror, as ghost stories and dark fairy tales are very much his specialty (as we shall see again in Shape of Water later this semester). I highly recommend his ghosts-as-a-reflection-on-the-trauma-of-war film The Devil’s Backbone and his take on portal fantasy, Pan’s Labyrinth (2006), as they’re both excellent and you can see echoes between them and the effects/visuals of Crimson Peak.

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

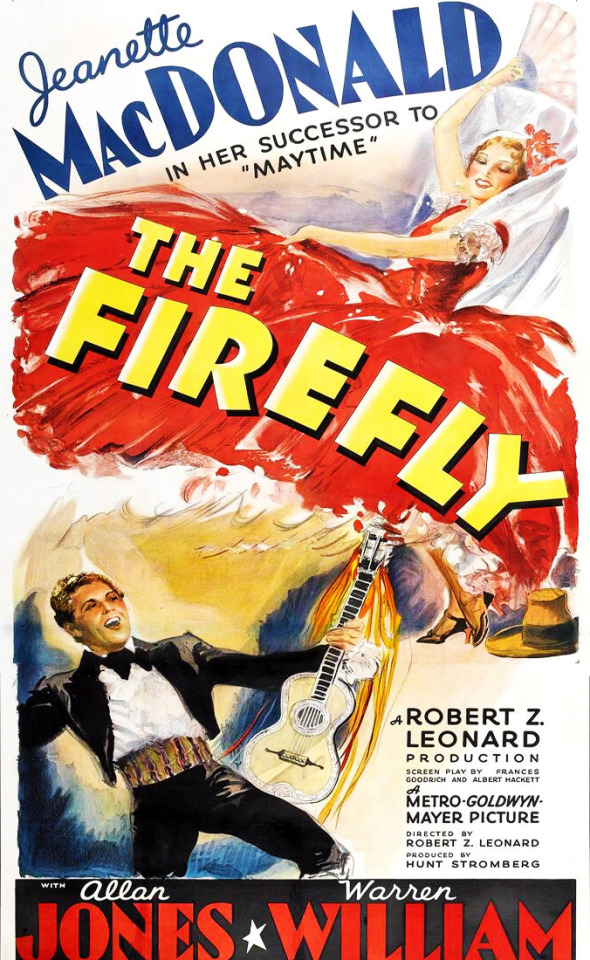

Jeanette MacDonald - The Iron Butterfly

Jeanette Anna MacDonald (born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania on June 18, 1903) was an American actress best remembered for her musical films in the 1930s. MacDonald was one of the most influential sopranos of the 20th century, introducing opera to film-going audiences and inspiring a generation of singers. She became known as "The Iron Butterfly", for she was one of the most lady-like and beautiful women in Hollywood, but when it came to contracts, she was tough and kept unwanted advances in check, rarely making a misstep in her career.

She was the third daughter of Scottish-American parents and the younger sister to character actress Blossom Rock ( who was most famous as "Grandmama" on the 1960s TV series The Addams Family), whom she followed to New York for a chorus job on Broadway in 1919.

After working her way up from the chorus to starring roles on Broadway, she was casted as the leading lady in Paramount Studios' The Love Parade (1929), a landmark of early sound films. Despite making many successful films with Paramount, she next signed with the Fox.

MacDonald then took a break from Hollywood in 1931 to embark on a European concert tour, performing at the Empire Theater in Paris and at London's Dominion Theatre. She was even invited to dinner parties with British Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald and French newspaper critics. She returned to Paramount the following year and made more films.

In 1933, MacDonald left again for Europe, and while there signed with MGM, which brought her together with Nelson Eddy. The pair made eight pictures together, including Maytime (1937), arguably the best musical of all time. From then on, they were forever known as America's Singing Sweethearts.

In 1943, she left MGM and began pursuing other interests. She made her opera debut singing Juliette in Gounod's Roméo et Juliette in Montreal at His Majesty's Theatre. After the war, MacDonald made two more films, but quit the movies altogether in 1949. The 1950s found MacDonald in the Las Vegas nightclub circuit, on television, in sold-out concert tours, in studio recordings, and on musical stage productions.

In her final years, MacDonald developed a serious heart condition. She died in Houston, Texas while awaiting heart surgery; she was 61 years old.

Legacy:

Won the Screen Actors Guild award for Maytime (1937)

Crowned as the Queen of the Movies in 1939 by 22 million filmgoers in a New York Daily News survey as presented by Ed Sullivan

Has 2 RCA Red Seal gold records (one for "Indian Love Call" (1936) and another for "Ah, Sweet Mystery of Life" (1935)

Has 1 RIAA gold record for Favorites in Hi-Fi (1959)

Was one of the highest-paid actresses in MGM in the 1930s

Listed by the Motion Picture Herald as one of America’s top-10 box office draws in 1936

Co-founded the Army Emergency Relief and raised funds on concert tours in 1941 to support American troops

Awarded an honorary doctor of music degree from Ithaca College in 1956

Named Philadelphia's Woman of the Year in 1961

Is the namesake of the USC Thornton School of Music built a Jeanette MacDonald Recital Hall built in 1975

Has a bronze plaque unveiled in March 1988 on the Philadelphia Music Alliance's Walk of Fame

Honored with a block in the forecourt of Grauman's Chinese Theatre in 1934

Co-wrote an autobiography, Jeanette MacDonald Autobiography: The Lost Manuscript, in the 1950s and which was eventually published in 2004

Honored as Turner Classic Movies Star of the Month for March 2006

Has two stars on the Hollywood Walk of Fame: 6157 Hollywood Boulevard for motion picture and 1628 Vine Street for recording

#Jeanette MacDonald#The Iron Butterfly#Silent Films#Silent Movies#Silent Era#Silent Film Stars#Golden Age of Hollywood#Classic Hollywood#Film Classics#Classic Films#Old Hollywood#Vintage Hollywood#Hollywood#Movie Star#Hollywood Walk of Fame#Walk of Fame#Movie Legends#Actress#hollywood actresses#hollywood icons#hollywood legend#movie stars#1900s

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

New Post has been published on http://lifehacker.guru/10-castles-in-europe-were-ready-to-check-into/

10 Castles in Europe We're Ready to Check Into

Visiting a castle is one thing, but how about staying the night in one? Across Europe, there’s a plethora of castles that open their doors to visitors as overnight accommodation. Feel like royalty in medieval manors surrounded by lush gardens or even a moat. Here are ten castles in Europe we’re ready to check into. Which would you book?

Dromoland Castle, Ireland

Credit: shutterupeire/Shutterstock

A magical pile with a history as long as your arm, Dromoland Castle is grandeur personified. There’s been a castle on this site since the 16th century, though the present structure dates from 1835. It’s now a five-star hotel with a fantastic golf course. In recent years it has attracted a host of celebrity guests including musicians Johnny Cash and Bono, actors John Travolta and Jack Nicholson, former U.S. presidents George W. Bush and Bill Clinton, Nelson Mandela and Richard Branson. While you’re here, you can try clay pigeon shooting, archery, falconry and horse riding. Or just wander the grounds and marvel at the stunning 450-acre estate.

Fortaleza do Guincho, Portugal

Credit: LuisPinaPhotography/Shutterstock

Built in the 17th century as a fortress, Fortaleza do Guincho has been renovated into an exquisite five-star hotel with Michelin-star restaurant thrown in for good measure. But it’s the castle’s isolated location at Cabo da Rocha, Europe’s most westerly point, which provides that extra touch of modern-day drama. Nature has to try that little bit harder, of course, when it rivals such luxury and comfort. Stone staircases, wrought iron chandeliers and sumptuous textiles all add atmosphere to this Portuguese jewel.

Château de Mirambeau, France

Credit: @chateaudemirambeau

French castles come in the form of fancy châteaux, and they don’t come much fancier than this Renaissance gem. The manor’s elegance and serenity belies a checkered history that has seen numerous attacks, devastating fires and a spell of State ownership after the French Revolution. Count Charles Nicolas Duchâtel rebuilt the place in the early 19th century and a major 21st-century renovation saw the castle become one of Sorgente Group’s most sought-after properties.

Schloss Leopoldskron, Austria

Credit: canadastock/Shutterstock

Palatial Schloss Leopoldskron was the work of Prince Leopold Anton Freiherr von Firmian – how’s that for a name? – when he built it as his family home in the 18th century. More famously, in 1918 it was bought by theater impresario Max Reinhardt, who lovingly restored it and came up with the idea of a Salzburg Festival within its walls. Fittingly, it was a filming location for the iconic movie The Sound of Music and features on many of the city’s themed tours. But to venture inside, you need to book a stay at this magnificent castle located at the edge of one of Austria’s most enchanting cities.

Castello dal Pozzo, Italy

Credit: @castello.dalpozzo

Castello dal Pozzo sits on top of a hill overlooking Lake Maggiore and the interiors of this boutique hotel more than match up to the delightful setting. The Visconti family built this romantic castle in the 18th century. The Dal Pozzos have owned it for six generations and go out of their way to ensure that anyone who stays there feels like family. Glittering chandeliers, lavish curtains and cut glass crystal at the table create a luxurious feeling that ensure every guest at this hotel is pampered as befits their location.

Dalhousie Castle, Scotland

Credit: Agent Wolf/Shutterstock

Scotland’s oldest castle started life as the ancestral seat of the Ramsay Clan. Over its 700-year history, Dalhousie Castle has enjoyed Royal patronage – King Edward I and Queen Victoria have both stayed here – as well as a who’s who of the well-to-do and the influential, from Oliver Cromwell to Sir Walter Scott. These days, it could be you who gazes out over its turrets and towers and discovers its passageways, secret hiding places and even its dungeon.

Thorskogs Slott, Sweden

Credit: Nihayet Marof/Shutterstock

Thorskogs Castle lies in a verdant setting, amidst English-style gardens near the Göta Älv River just north of the city of Gothenburg. It opened its doors as a hotel in the mid-1980s with a guest list that reads like a who’s who of world statesmen: George Bush, Mikhail Gorbachev, John Major, Benazir Bhutto and FW de Klerk. There’s been a manor house on this site since the 18th century, but the current building was originally the home of successful shipping magnate Petter Larson and dates from 1892.

Hever Castle, England

Credit: Richard Melichar/Shutterstock

Hever Castle dates back to the 13th century and today remains one of England’s finest castles. It’s everything you dream a castle should be: crenellated, moated and of course, haunted. Anne Boleyn, second wife of King Henry VIII, lived here as a child. A tour of the castle’s fascinating interior will reveal treasures such as fine tapestries, antique furniture, a wonderful collection of Tudor portraits and even Anne’s own prayer books. We can thank William Waldorf Astor for restoring the house and opening the Astor Wing for visitors to stay and become part of English history.

Parador de Cardona, Spain

Credit: joan_bautista/Shutterstock

Around 85km from Barcelona you’ll find the Parador de Cardona. This beautiful hotel occupies a mediaeval 9th-century castle positively dripping with secrets from the past. The castle boasts a resident ghost – if you’re easily spooked, don’t book room 712 where a poltergeist has a penchant for moving the furniture. Décor has been carefully thought through so that heritage features such as the towers and gothic adornments are allowed to shine, but they’re knocked out of the park by the incredible view over the town and surrounding countryside.

Stahleck Castle, Germany

Credit: kamienczanka/Shutterstock

If you’ve read this far and are bemoaning the fact that your paltry travel budget won’t stretch to castle living, Stahleck Castle will be your lifeline. This 12th-century castle, perched on a crag overlooking the breathtaking Lorelei Valley, is actually a hostel. Outside, there’s even a moat, a rare sight when it comes to German castles. Though it looks authentic, the castle is a sympathetic 20th-century reconstruction, but with dorm beds going for less than €25, who’s complaining?

(C)

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Franco Zeffirelli dies at 96

Franco Zeffirelli, the Italian director and designer who reigned in theater, film and opera as the unrivaled master of grandeur, orchestrating the youthful 1968 movie version of “Romeo and Juliet” and transporting operagoers to Parisian rooftops and the pyramids of Egypt in productions widely regarded as classics, died June 15 at his home in Rome. He was 96.

A son, Luciano, confirmed the death to the Associated Press but did not cite a cause.

Mr. Zeffirelli — a self-proclaimed “flag-bearer of the crusade against boredom, bad taste and stupidity in the theater” — was a defining presence in the arts since the 1950s. In his view, less was not more. “More is fine,” a collaborator recalled Mr. Zeffirelli saying, and as a set designer, he delivered more gilt, more brocade and more grandiosity than many theater patrons expected to find on a single stage.

“A spectacle,” Mr. Zeffirelli once told the New York Times, “is a good investment.”

From his earliest days, he seemed to belong to the opera. Born in Italy to a married woman and her lover, he received neither parent’s surname. His mother dubbed him “Zeffiretti,” an Italian word that means “little breezes” and that arises in Mozart’s opera “Idomeneo,” in the aria “Zeffiretti lusinghieri.” An official mistakenly recorded the name as “Zeffirelli.”

Mr. Zeffirelli grew up mainly in Florence, amid the city’s Renaissance riches, and trained as an artist before being pulled into theater and then film by an early and influential mentor, Luchino Visconti. Mr. Zeffirelli matured into a sought-after director in his own right, staging works in Milan, London and New York City, where he became a mainstay of the Metropolitan Opera.

His first major work as a film director was “The Taming of the Shrew” (1967), a screen adaptation of Shakespeare’s comedy, starring Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton. But Mr. Zeffirelli was best known for the Shakespearean adaptation released the next year — “Romeo and Juliet,” starring Leonard Whiting and Olivia Hussey in the title roles.

He reportedly reviewed the work of hundreds of young actors before selecting his two stars, both of whom were still in their teens. With a lush soundtrack by Nino Rota, and with its equally lush visuals, the film won the Academy Award for best cinematography and was a runaway box office success. Film critic Roger Ebert declared it “the most exciting film of Shakespeare ever made.”

It “is the first production of ‘Romeo and Juliet’ I am familiar with in which the romance is taken seriously,” Ebert wrote. “Always before, we have had actors in their 20s or 30s or even older, reciting Shakespeare’s speeches to each other as if it were the words that mattered. They do not, as anyone who has proposed marriage will agree.”

In the opera, an art form already known for its opulence, big voices and bigger personalities, Mr. Zeffirelli permitted himself to be deterred by neither physical nor financial constraints. “Opera audiences demand the spectacular,” he told the Times.

Mr. Zeffirelli had notable artistic relationships with two of the most celebrated sopranos of the 20th century, Maria Callas and Joan Sutherland. But certain Zeffirelli sets seemed to excite the opera world even more than the performers who sang upon them.

One such example was his production of Puccini’s “La Boheme,” an extravaganza set in 19th-century Paris and famous for its exuberant street scene and magical snowfall. After its 1981 premiere at the Met, it was said that the audience lavished on Mr. Zeffirelli a grander ovation than the one reserved for conductor James Levine and the singers who played the opera’s bohemian lovers.

“For the first time,” Mr. Zeffirelli told the Times, “audiences will have a sense of the immensity of Paris, and the smallness of this little group’s place — the actual space of a garret. The acting is now intimate and conversational, which is exactly what Puccini wanted. Since the garret is raised, every whisper and gesture will come across clearly in the theater.”

His production of Verdi’s “Aida,” performed at Milan’s La Scala in 1963 with soprano Leontyne Price and tenor Carlo Bergonzi, featured 600 singers and dancers (including scantily clad belly dancers), 10 horses, towering idols, palm trees and sphinxes littering the expanse of the stage. “I have tried to give the public the best that Cecil B. DeMille could offer,” Mr. Zeffirelli told Time magazine, referring to the Hollywood director’s biblical epics, “but in good taste.”

It was sometimes said that Mr. Zeffirelli was beloved by everyone except music reviewers, some of whom disparaged his style as excessive to the point of taking attention away from the music. Writing in the Times, Bernard Holland panned Mr. Zeffirelli’s set for Puccini’s “Turandot,” set in China, as “acres of white paint and gold leaf topped by the gaudiest of pagodas” and quipped that “if the gods eat dim sum, they certainly do it in a place like this.”

In time, the Metropolitan Opera replaced some of Mr. Zeffirelli’s productions, although the modernistic newcomers — notably Luc Bondy’s dreary “Tosca” in 2009 — did not always prove as popular.

“It’s like somebody decides that the Sistine Chapel is out of fashion,” Mr. Zeffirelli told the Times. “They go there and make something a la Warhol. . . . You don’t like it? O.K., fine, but let’s have it for future generations.”

As for those who had criticized his direction of “Romeo and Juliet” for similar reasons, he retorted, “In all honesty, I don’t believe that millions of young people throughout the world wept over my film ... just because the costumes were splendid.”

Mr. Zeffirelli was born in Florence on Feb. 12, 1923. His father, Ottorino Corsi, was a Florentine businessman, and his mother, Alaide Garosi, was a fashion designer. Her husband was a lawyer, and he died before Mr. Zeffirelli was born.

His mother continued a fraught relationship with Corsi, once attempting to stab him with a hat pin. “The opera? My destiny?” Mr. Zeffirelli observed in a 1986 autobiography, “Zeffirelli.” “I think there is a case to be made.”

After the death of his mother when he was 6, he became the charge of an aunt. He recalled his upbringing in the 1930s in the semi-autobiographical film “Tea With Mussolini” (1999), which he directed and which starred Maggie Smith, Judi Dench and Joan Plowright as English expatriates in Florence who take in a parentless child during the era of fascist rule.

Mr. Zeffirelli attended art school before studying architecture at the University of Florence. His studies were put on hold during World War II, when he fought alongside antifascist partisans. His interests shifted more toward film, particularly after he saw Laurence Olivier star in the 1944 Technicolor film adaptation of Shakespeare’s “Henry V,” which Olivier also directed.

“The lights went down and that glorious film began,” Mr. Zeffirelli recalled in his memoir. “I knew then what I was going to do. Architecture was not for me; it had to be the stage.”

He met Visconti while working in Florence as a stagehand. Visconti, with whom he lived for a period, gave him his push into professional work, hiring him to work as a designer for an Italian stage production of Tennessee Williams’s “A Streetcar Named Desire” in 1949.

Mr. Zeffirelli soon began designing and directing at La Scala and later the Met. He designed, directed and adapted from Shakespeare the libretto for the production of Samuel Barber’s “Antony and Cleopatra” that opened the Met’s new opera house at Lincoln Center in 1966.

Mr. Zeffirelli said he found it invigorating to shift from one art form to another. His theatrical productions starred top-flight actors including Albert Finney and Anna Magnani. On television, he directed “Jesus of Nazareth,” an acclaimed 1977 miniseries with a reported price tag of $18 million and a cast that included Robert Powell as Jesus, Hussey as the Virgin Mary, Olivier as Nicodemus, Anne Bancroft as Mary Magdalene and James Earl Jones as Balthazar.

Mr. Zeffirelli received a best director Oscar nomination for “Romeo and Juliet.” (He lost to Carol Reed for the musical “Oliver!”) He also garnered a nomination for best art direction for his 1982 film adaptation of Verdi’s opera “La Traviata,” starring Teresa Stratas and Plácido Domingo, one of several such operatic film adaptations he made.

His other notable films included “Hamlet” (1990) starring Mel Gibson and Glenn Close. Less acclaimed was “Endless Love” (1981), starring Brooke Shields and Martin Hewitt in a tragic story of teen romance, which Mr. Zeffirelli admitted was “wretched.”

Politically, Mr. Zeffirelli positioned himself on the right, serving as a senator in the political party Forza Italia. “I have found it an irritating irony that those who espouse populist political views often want art to be ‘difficult,’ ” he wrote in his memoir. “Yet I, who favor the Right in our democracy, believe passionately in a broad culture made accessible to as many as possible.”

He described himself as homosexual, preferring not to use the word “gay.” In 2000, he adopted two adult sons, Pippo and Luciano, both former lovers, according to the newspaper the Australian. A complete list of survivors was not immediately available.

Looking back on his life and career, Mr. Zeffirelli once told The Washington Post that he was struck by “how much is risked to become something” — “to make something of his life,” he continued, speaking of himself in the third person. To show that “he’s not a bastard.”

Daily inspiration. Discover more photos at http://justforbooks.tumblr.com

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

News and important updates on POS System Equipment & POS.

Scenes from The Searchers (1956), starring John Wayne and set during the Texas-Indian Wars. The film is considered one of the most influential Westerns ever made.

“It just so happens we be Texicans,” says Mrs. Jorgensen, an older woman wearing her blond hair in a tight bun, to rough-and-tumble cowboy Ethan Edwards in the 1956 film The Searchers. Mrs. Jorgensen, played by Olive Carey, and Edwards, played by John Wayne, sit on a porch facing the settling dusk sky, alone in a landscape that is empty as far as the eye can see: a sweeping desert vista painted with bright orange Technicolor. Set in 1868, the film lays out a particular telling of Texas history, one in which the land isn’t a fine or good place yet. But, with the help of white settlers willing to sacrifice everything, it’s a place where civilization will take root. Nearly 90 years after the events depicted in the film, audiences would come to theaters and celebrate those sacrifices.

“A Texican is nothing but a human man way out on a limb, this year and next. Maybe for 100 more. But I don’t think it’ll be forever,” Mrs. Jorgensen goes on. “Someday this country’s going to be a fine, good place to be. Maybe it needs our bones in the ground before that time can come.”

There’s a subtext in these lines that destabilizes the Western’s moral center, a politeness deployed by Jorgensen that keeps her from naming what the main characters in the film see as their real enemies: Indians.

In the film, the Comanche chief, Scar, has killed the Jorgensens’ son and Edwards’ family, and abducted his niece. Edwards and the rest of Company A of the Texas Rangers must find her. Their quest takes them across the most treacherous stretches of desert, a visually rich landscape that’s both glorious in its beauty and perilous given the presence of Comanche and other Indigenous people. In the world of the Western, brutality is banal, the dramatic landscape a backdrop for danger where innocent pioneers forge a civilization in the heart of darkness.

The themes of the Western are embodied by figures like Edwards: As a Texas Ranger, he represents the heroism of no-holds-barred policing that justifies conquest and colonization. While the real Texas Rangers’ history of extreme violence against communities of color is well-documented, in the film version, these frontier figures, like the Texas Rangers in The Searchers or in the long-running television show The Lone Ranger, have always been portrayed as sympathetic characters. Edwards is a cowboy with both a libertarian, “frontier justice” vigilante ethic and a badge that puts the law on his side, and stories in the Western are understood to be about the arc of justice: where the handsome, idealized male protagonist sets things right in a lawless, uncivilized land.

The Western has long been built on myths that both obscure and promote a history of racism, imperialism, toxic masculinity, and violent colonialism. For Westerns set in Texas, histories of slavery and dispossession are even more deeply buried. Yet the genre endures. Through period dramas and contemporary neo-Westerns, Hollywood continues to churn out films about the West. Even with contemporary pressures, the Western refuses to transform from a medium tied to profoundly conservative, nation-building narratives to one that’s truly capable of centering those long victimized and villainized: Indigenous, Latinx, Black, and women characters. Rooted in a country of contested visions, and a deep-seated tradition of denial, no film genre remains as quintessentially American, and Texan, as the Western, and none is quite so difficult to change.

*

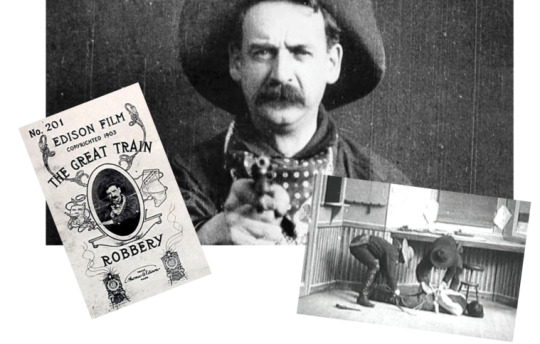

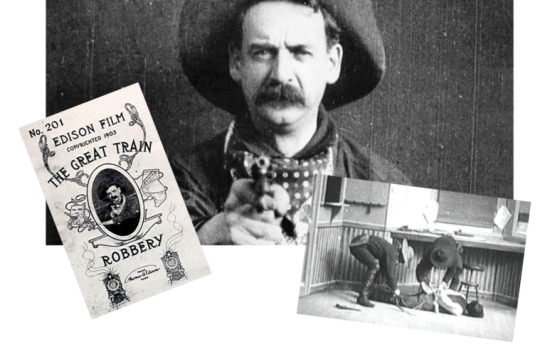

With origins in the dime and pulp novels of the late 19th century, the Western first took to the big screen in the silent film era. The Great Train Robbery, a 1903 short, was perhaps the genre’s first celluloid hit, but 1939’s Stagecoach, starring Wayne, ushered in a new era of critical attention, as well as huge commercial success. Chronicling the perilous journey of a group of strangers riding together through dangerous Apache territory in a horse-drawn carriage, Stagecoach is widely considered to be one of the greatest and most influential Westerns of all time. It propelled Wayne to stardom.

During the genre’s golden age of the 1950s, more Westerns were produced than films of any other genre. Later in the 1960s, the heroic cowboy character—like Edwards in The Searchers—grew more complex and morally ambiguous. Known as “revisionist Westerns,” the films of this era looked back at cinematic and character traditions with a more critical eye. For example, director Sam Peckinpah, known for The Wild Bunch (1969), interrogated corruption and violence in society, while subgenres like spaghetti Westerns, named because most were directed by Italians, eschewed classic conventions by playing up the dramatics through extra gunfighting and new musical styles and creating narratives outside of the historical context. Think Clint Eastwood’s The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly (1966).

The Great Train Robbery (1903), a short silent film, was perhaps the first iconic Western.

In the wake of the anti-war movement and the return of the last U.S. combat forces from Vietnam in 1973, Westerns began to decline, replaced by sci-fi action films like Star Wars (1977). But in the 1990s, they saw a bit of rebirth, with Kevin Costner’s revisionist Western epic Dances With Wolves (1990) and Eastwood’s Unforgiven (1992) winning Best Picture at the Academy Awards. And today, directors like the Coen brothers (No Country for Old Men, True Grit) and Taylor Sheridan (Hell or High Water, Wind River, Sicario) are keeping the genre alive with neo-Westerns set in modern times.

Still, the Old West looms large, says cultural critic and historian Richard Slotkin. Today’s Western filmmakers know they are part of a tradition and take the task seriously, even the irreverent ones like Quentin Tarantino. Tarantino called Django Unchained (2012) a spaghetti Western and, at the same time, “a Southern.” Tarantino knows that the genre, like much of American film, is about violence, and specifically racialized violence: The film, set in Texas, Tennessee, and Mississippi, flips the script by putting the gun in the hand of a freed slave.

Slotkin has written a series of books that examine the myth of the frontier and says that stories set there are drawn from history, which gives them the authority of being history. “A myth is an imaginative way of playing with a problem and trying to figure out where you draw lines, and when it’s right to draw lines,” he says. But the way history is made into mythology is all about who’s telling the story.