#loose iambic meter

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

d a y d r e a m

you’re a novel

on a summer day

when the afternoon

decides

that the sun is not

becoming,

and so behind the

thunder hides.

you’re a glass where

spirits dwell,

you’re a trellis

for the vine,

you’re the ears in which

the prophets tell

the fate of all mankind.

—rudysassafras

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

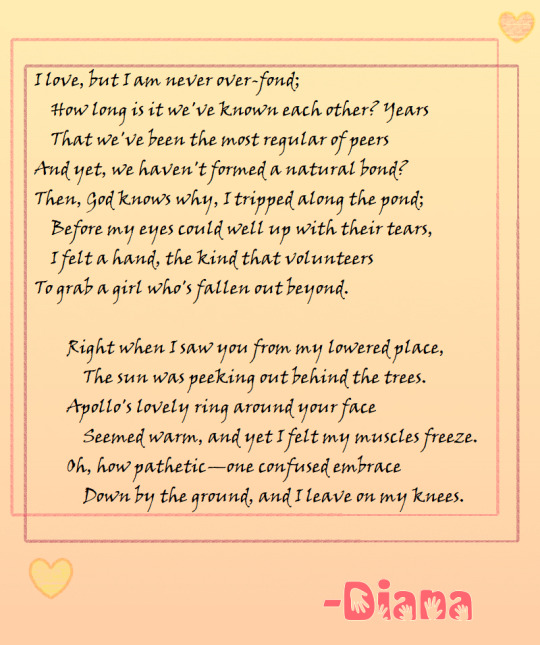

“Crossed Out” - a Petrarchan sonnet written 12/08/2022

#2022#college years#iambic meter#iambic pentameter#sonnet#love sonnet#petrarchan sonnet#pastiche poetry#italian sonnet#form poetry#classical poetry#poetess#this is based very VERY loosely off of a feeling ive been having lately that i would not classify as romantic#but the first time i tried writing a poem about that feeling today it ended up sounding very. mean. i sorta slipped into my usual voice#when writing poetry about relationships/men which is. not a very nice one. and i mean i'm not angry at the person. at all.#it had some good lines in it but it was ultimately not what i set out to write. so i tried to write a more first-off appreciative one#but i noticed it was taking a romantic tone very quickly but. eh. i let it happen. even though i kinda winced as i did it.#it's not LESS accurate than the one i wrote before for encapsulating the feelings i have. and i had some good ideas for a romantic scene#i naturally don't write a lot of unironic love poetry as i am. you know. your local aroace poetess. i write more romance-repulsed poetry#and god i hate it when ppl reblog it and tag it interpreting it as love poetry. i would rather you just not interact w my work honestly! if#that's what you're going to do. but anyway rant aside.#it was something of a challenge to not hate myself writing this. i'm not quite sure it even sounds like my voice#but the other one i wrote was *too* my voice.#and even if this is a sonnet narrated by no one. some random little lovesick girl. it's a good little pastiche piece.#a very TRADITIONAL sonnet you'd say.#from an untraditional poetess

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

@clingyduoapologist made a really cool “what if DSMP were a stage play” post and basically the instant I saw it I was struck by the muse but I don’t want to just chain reblog the dang thing or make one huge reblog with all my thoughts so instead here are all my thoughts on this concept

i don’t think it’s a musical. I think the tone of the story doesn’t fit. But if it were, it would have a Lot of scenes of unsung dialogue, and that dialoge? Would be rhythmic poetry. It’s Shakespeare Appreciation Time baby.

i do however think there would be a live score and an orchestra. A lot of the music would need to be recorded but there’s at least be a few musicians.

different characters speak in different poetic styles at different times to communicate character and plot development.

to elaborate on that: Characters switch from loose ABBA or ABAB rhyme schemes and vaguely rhythmic meter when chatting back and forth to strict perfect iambic pentameter for tense scenes or political speeches.

Techno speaks exclusively in unrhyming dactylic hexameter, an extremely common poetic form for Greek and Latin poetry. It’s what the Iliad was written in. This has the interesting effect of making Techno sound, at first glance, unpoetic. His speech doesn’t rhyme, and doesn’t follow a common English rhythm scheme, so it wouldn’t immediately register as structured. However, dactylic hexameter is actually significantly harder to write in English than expected because of our syllable stress patterns. Speaking like that would be, objectively, a sign of extreme intelligence, but could easily be overlooked as coarse uncultured behavior.

Techno’s chorus - composed of audience members, background extras, and people (in safety harnesses) sitting in the theater rafters - speak largely in Greek and Classical Chinese, quoting sections of the Art of War and Homer’s work. The major exceptions to this are ‘Blood for the Blood god,’ ‘no,’ and ‘do it.’ They all wear a hat or some form of headband that has a glowing LED eye, hidden, but activated when they speak. The audience plants are all in dark clothes, and when the lights go down they don medical masks/sunglasses. Anything to obscure their faces.

The Chorus, a group of robed masked people who broke the fourth wall and often entered the audience, was a vital part of early Greek theatre. I am an intolerable nerd, and the thought of sitting in a dark theatre only to hear an low distorted voice beside you start to comment on the play as a whole choir of voices echo around you, then turning to see your seat neighbor is a masked person with a glowing red eye in your forehead? Literally incredible.

Dream is the only character dressed in even remotely modern clothes.

Dream is first seen as someone (again, in modern clothes) sneaking around backstage in a black hoodie: most of the audience probably assumes he’s a stagehand and not meant to be seen. Then, at some point, he moves from behind a set piece and enters the scene as an actual character, revealing his mask.

interestingly, this is really similar to what I believe is a bit of myth about why ninjas are dressed in all black in modern media. They wouldn’t have been irl, they would’ve dressed like civilians. But stagehands in Japanese theatre would dress in all-black, and were often completely visible onstage moving sets - it was common courtesy to ignore them. Then one day some playwright had the brilliant idea of having one of the stagehands enter the story as an assassin, and suddenly every actor in all-black was a threat. For the life of me I can’t remember where I read that but it’s a cool thought :D

Dream canonically can interact with set pieces, lighting, and curtains.

Dream actively directs lighting in scenes he is not in, sitting above the stage kicking his feet.

Dream is often used to hand off props to characters instead of having them pull them from a pocket and pretend they were pulled from their ‘inventory.’ This begins to get confusing when Dream is acknowledged later on as the he person giving, say, TNT to Wilbur, or wither skulls to Techno.

characters address the audience as ‘Chat,’ (English’s first fourth-person pronoun my beloved) almost constantly, especially for comedic purposes- most of their monologues are addressed directly to the audience as well. For Wilbur, it’s a sign of instability when he stops addressing ‘Chat’ and start addressing the sides or back of the stage.

philza enters from the lower audience, right by the stage, probably after pooping up from the orchestra pit and taking a reserved seat halfway through so no one sees the wings.

Tommy has by far the least structured or rhyming dialogue - if it weren’t for how carefully crafted it was it would sound like normal prose.

Tommy speaks to the audience by FAR the most. Wilbur only addresses them when soliloquizing. Techno barely addresses them at all: they address him. Ranboo speaks to the audience only when alone, and it’s usually phrased like he’s writing in his memory journal. Tommy speaks to the audience at first like a loud younger brother. As he gets older, it sounds more and more like a plea for help, a prayer for intervention that will never come. Exile is one long string of desperate begging aimed our way.

Tommy stops speaking to the audience so much after Doomsday. He starts again when Dream is imprisoned. He stops for good when he dies in there, beaten, alone.

Sam and the Warden are meant to be played by different actors, ideally siblings or fraternal twins. They wear identical stage makeup and costumes, but the difference is there. None of the characters acknowledge this.

the Stage would need to be absolutely massive and curve almost halfway around the central audience, largely because it should be able to be split at times into two separate stages to show different things happening at the same time. This could possibly also work if there were two stages, but getting people to easily turn from one stage to the other without loosing sight of what was happening would be rough.

Doomsday taking advantage of the scaffolding in the rafters and using them as the ‘grid’ for the tnt droppers.

actual trained dogs for Doomsday my beloved. Would cost a fortune but could you imagine.

the entire revolution arc ripped off Hamilton, we all know that, I think we can afford to have a stagehand step forward in that frozen moment in time when Tommy and Dream have that duel, grab the arrow, and carry it slowly across the stage right into Tommy’s eye. For morale.

throughout the execution scene Techno keeps slipping out of poetic meter, especially when he sees/is worried about Phil. After the totem (which would be freaking amazing as some sort of stage effect with like lights and red and green streamers or smthn dude-) he stops speaking in poetry. The scene with Quackity is entirely spoken dialogue. Chat is silent. It’s only when he gets back and sees evidence that his house has been tampered with that Chat starts up again (kill, blood, death, hunt, hunt, hunt-) and he starts speaking in rhythm again.

Every canon death, Dream marks a tally on something in the background. Maybe it’s in his arm? Like a personal scorecard. Or maybe it’s on the person themselves, a little set of three hearts he marks through with a dry-erase marker or something.

phil and techno have a lot more eastern design elements and musical influences than the rest of the cast, except for Techno’s war theme which is just choir, bagpipes, and some sort of rhythmic ticking or thumping. Phil’s also got a choir sting but it’s a lot harsher, the ladies are higher and them men lower, and the chords are really dissonant (think murder of crows)

Tommy’s theme has a lot of drums, but its core is actually a piano melody. The inverse of Tommy’s theme is Tubbo’s, but Tubbo’s is usually played on a ukulele. Wilbur is guitar, obv, and Niki’s is on viola.

Quackity is a little saxophone lick. He and Schlatt both have a strong big band/jazz influence.

None of the instruments that play dream’s theme play anywhere else in the music. I’m thinking harp, music box, and some kind of low wind instrument.

#I have more thoughts but apparently there’s a character limit on lists or smthn it wouldn’t post if it were longer :/#molten rambles#technoblade#mcyt#philza#dsmp#theatre#musical theatre#Shakespeare mention#tommyinnit#dream#wilbur soot#dream smp

111 notes

·

View notes

Text

First Night's Hunger

A sestina* written using prompts provided by @whickberstreetwriters and @ineffablyruined.

To paper I touch ink, Scribbling words feral, Fierce with hunger. My brow blossoms dew, Betraying memories wanton, A heart unraveled.

A heart unraveled And writ upon with fiery ink Casts down thoughts wanton. The deed recorded feral As the first day's dew, The first night's hunger.

The first night's hunger, Angelic restraint unraveled. Loss of it slicked my face as dew. Gluttony painted in gristled ink Summoned from you a look feral, Ignited in me a flame wanton.

Ignited in me a flame wanton, A temptation stoked eternal hunger, Caused cravings feral. Divine bonds unraveled. A new concord would itself ink Across my spirit as covering dew.

Across my spirit as covering dew Blossomed a blasphemy wanton. Beside Her name, 'nother in blazing ink Engraved by indelible hunger. The shame of it proved me unraveled. I feared myself a Fallen feral.

I feared myself a Fallen feral. Tears shed, a mourning dew. Terror showed my Faith unraveled. Then, comfort from source of appetite wanton. Crowing not for kindling hunger, A confidant scribing secrets in lemon juice ink.

I now ink this ancient hunger to a page, as wanton As 'twas that burning night you unraveled my feral greed. As the dew yet clings to Eden's walled-in green, it shall never dry.

~~~~~~~

*A sestina is a poem that dates back to twelfth century Europe. It has a strict form, involving the repetition of six words in a specific rotating order over six stanzas. It's often written in iambic pentameter and ended with a three-line stanza containing all six words. This was a new form for me, and I may have played fast and loose with the meter and the last stanza.

#good omens#good omens poetry#whickber street writers association#ineffable prompt a thon#sestina#a companion to owls#aziraphale#poetry#my poetry#original poem#fan poetry

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

It's weird that there are two famous poets named Yeats and Keats. No take here. Just strange. Anyway I was reading some Yeats yesterday and is it just me or is his meter really frustrating. He's too loose with it, so like maybe a third of his lines aren't actually iambic pentameter. It's like a slightly irregular staircase, you keep stumbling

17 notes

·

View notes

Note

You literally made a language, made its fucked up classical form, THEN WROTE A WHOLEASS POEM IN SAID CLASSICAL FORM. Are you aware of the power you wield?

i stared into the abyss and the abyss stared back anyway here's how to write a saporian lágha:

twelve lines of six syllables, divided into two stanzas of six lines each

the first stanza (the nȉtȧnē) is five lines in iambic trimeter followed by a single line of trochaic trimeter, and the second stanza (the càidh) reverses that, so five lines in trochaic trimeter followed by a final line in iambic trimeter. so the metrical structure of the lágha is:

uS/uS/uS uS/uS/uS uS/uS/uS uS/uS/uS uS/uS/uS Su/Su/Su

Su/Su/Su Su/Su/Su Su/Su/Su Su/Su/Su Su/Su/Su uS/uS/uS

[because fuck you that's why]

no rhyme scheme because i'm not a fucking sadist, but i think if there were a rhyme scheme it'd be ab c ab d ba c ba d (i think sorchā def wrote a rhyming lágha using that scheme once just to prove she could, but--well i'd say i'm not going to torture myself to write it but i also used to say i absolutely would not write any actual poetry in actual saporian and then the urge hit and here we are

the nȉtȧnē introduces a thought or idea which is then defended or interrogated in the càidh, following the loose thematic structure of either statement-and-proof or thought-and-reversal; the càidh is an unfolding of or elaboration on the nȉtȧnē, and i think there is a style of lágha heavily identified with sorchā (thus: the sorchān lágha) that is characterized mainly by the càidh being witheringly cynical hsdkfb

ideally the development of the idea from the nȉtȧnē to the càidh is done through wordplay/creative composition/double entendre/punning (esp with contrastive stress, although that is. a lot harder in english than in saporian hsdbhkgs) or using a device i have tentatively decided to call linguistic obversion which is a thing you can do in saporian that involves taking a word (e.g. pàta /ˈpæta/ "skin, flesh") and negating it in a way that implies not the opposite but rather the removal or failure or loss of the root word (e.g. lȧpàta /laˈpæta/ "hide, leather, vellum" but literally "skin/flesh that was flayed away")--saporian is a very flexible and malleable language that lends itself to taking a word or phrase and totally unravelling it and reweaving it into a new context and that is i think the Essence of what the lágha is about.

which makes them goddamn hard to write in english hsdkbhks the amount of time i spent banging my head against the keyboard trying to figure out a way to translate cȧthȅthīrȧdāchēs without losing the essence of its meaning or breaking the meter was too much. bc that word is like—ok it's a triple compound:

cathay+ȅthīr+adách-[locative case] = cȧthȅthīrȧdāchēs

cathay means carcass and ȅthīr means a quarry or pit or other manmade hole in the ground, so cȧthȅthīr pretty straightforwardly means "corpse-pit" or maybe "catacomb"

but adách is a bound root that can mean all sorts of things depending on what grammatical case you attach to it; as a root it loosely means "given shape" and belongs to a family of words that can, broadly, refer to both sculpture and education with specific meaning being largely dependent on context. so adách can mean:

- "pedagogy"/"sculpture" in the nominative case [adáchȧ] - also in the accusative [adáchȧs]

but also:

- "pupil"/"statue" in the genitive or dative cases [adáchaegh/adáchan]

but also:

- "school"/"workshop" in the locative, lative, & ablative cases - [adáches, adáched, adáchet] positioning adách at the end of the compound allows it to receive the locative ending and makes it primarily read as "a place of learning"/"a place where statues are made" but also, the way nominal composition works in saporian is each noun in a compound functions as an adjective describing the preceding noun(s); so a very literal translation of cȧthȅthīr would be "carcasses, which have been dumped in a pit" and a very literal translation of ȅthīrȧdāchēs would be "a quarry, where things are given shape [sculpted and/or taught]", and thus a very literal translation of cȧthȅthīrȧdāchēs would be "carcasses, which are [statues/students/things given shape], and which have been dumped in the pit where other things are [given shape/sculpted/taught]"

so cȧthȅthīrȧdāchēs despite being literally just three nouns strung together can also function as a completed thought all by itself: you could translate this single word as "the university, a mass grave where individuality dies, as students are sculpted and molded like statuary until it kills them."

(this is how lágha get away with being so brief: you can say a hell of a lot in just seventy-two syllables if you're writing in a language that allows you to cram entire complex metaphorical sentences into a simple six-syllable compound word.)

which is all well and good but of course in english there just. isn't a good way to convey all of that in six syllables of iambic meter lmao "The girl thus/digs, and dies; among all/the corpse-pit effigies" is i think probably the closest i'm going to get without violating the meter. the reason i hate poetry is it gnaws on my brain like a goddamn terrier and refuses to let go

18 notes

·

View notes

Note

Which are the best latin-to-english translations for those of us who want to read the classiques without having to learn Latin (latin looks so HARD), which translations would you recommend?

i can't say which ones are best (except for mine; any translations i publish will be the best ones), but here are some concerns & considerations to keep in mind when you choose a translation:

meter: occasionally english translations will try to preserve the latin meter but more often they use an english meter (e.g. iambic pentameter). older translations tend to be metered and sometimes rhyme (such as john dryden's aeneid). i love when they rhyme but it does mean the translator has taken far more liberties

looseness: some translations stick closely to the literal, while others stray further, often to fit the meter and/or sound more poetic. this isn't easy to tell when you only have the one translation, but it might be worth comparing different translations to see what's been added or removed

bilingualism: "bilingual editions" have the original text juxtaposed with the translation (i like these very much)

age: you will often find translations (esp. online) that are from the early 20th century or before and it shows! there can be a charm to these, but sometimes they sound more stilted and uncomfortable than anything, in which case you might prefer a more modern edition

political context: translation is not a neutral act! often the agenda of the translator is evident in the choices that they make (easier to see in "controversial" texts like catullus or explicitly political ones like caesar). this is another reason why reading multiple translations can be advantageous, to see how different lights & framing change the text

availability: there are translations of many latin texts freely & legally available on the internet, which is super convenient! sites like perseus and theoi are amazing for this, or even googling "[text] english translation". these translations tend to be older (and therefore in the public domain), so more recent translations might have to be purchased (or otherwise acquired). if you're looking for physical editions, i would suggest prioritizing ones that you can't find online!

for the most part, i use the "read what i can find online" strategy for translations, so i don't have real recommendations there, but i can tell you what books i have here at school if that helps:

david ferry: vergil's aeneid

peter green: the poems of catullus

rolfe humphries: ovid's metamorphoses

david west: horace's odes and epodes

john davie: horace's satires and epistles

these are all lovely and competent editions that i have enjoyed reading. i have read other translations of each of these works and enjoyed them too. every translation is a work of art, and i wouldn't worry about finding the best one. find what you love, and read that.

finally: i won't pretend latin isn't hard, because it is! and if you have no interest in learning and prefer to read translations, that is a good choice for you and i support that—however, if you are at all interested in learning latin, i'd encourage you not to let the thought that it's hard put you off. it's a beautiful and rewarding language, and if you want to learn it, you can & should go for it!

15 notes

·

View notes

Audio

Meter and rhyme. Though so much of contemporary American poetry chooses to forgo these trusty, rusty tools, they remain the first things many of us think of when we think of poetry. And Brad Leithauser thinks of them more than most, dedicating two chapters to the subject in his recent Rhyme’s Rooms: The Architecture of Poetry—part guide and part exuberant ode to poem-making. The marriage of meter and rhyme, he tells us, is a “remarkably stable” one, flourishing in English-language literature since the Age of Chaucer and still playing by rules that Chaucer himself would recognize. But every marriage has its tensions, and in the passage below Leithauser walks us through one of poetry’s most memorable stanzas to reveal how those moments of dissonance are often the most delectable of all.

______________

There are days, as I say, when “Stopping by Woods” seems the most beautiful poem ever written. Or Housman’s “Loveliest of Trees.” Or any one of a dozen verses whose beauty is synonymous with simplicity and impeccability of finish, verses of a sufficiency so tranquil and surfeited as to declare on its face the folly of adding or subtracting anything. On most days, though, I prefer the poem that trails sensations of something unfinished or unresolved, the presence of what I think of as the right sort of wrongness. Such poems leave you restless, eager to tinker, to amend and to placate. [Consider] the closing stanza of one of America’s best-loved poems, Frost’s “The Road Not Taken.” Laid out in four cinquains, the poem sports a loose iambic tetrameter—but never more loose and indeterminate than in its final line: I shall be telling this with a sigh Somewhere ages and ages hence: Two roads diverged in a wood, and I— I took the one less traveled by, And that has made all the difference. When I’ve asked students to read the poem aloud, they diverged most while delivering the last line. It was sometimes read: And that has made all the diff e rence. And sometimes: And that has made all the diff e rence. And sometimes: And that has made all the diff erence. (The problem with this last interpretation is that rhyme is pulling you contrariwise, urging you to land prominently on the last syllable.) The poem deposits us into a familiar zone, indeed a wonderful zone: an arena where rhyme and meter are in constant and fertile contention. In his old age, Frost crystallized his life as a “lover’s quarrel” with the world. But isn’t the phrase equally applicable to Frost’s dual apprentices, rhyme and meter, in their behavior here? They come into full fruition only when challenging each other. How to read the final line? Rhyme is voicing its demands. And so is meter. And you are a couples therapist, vainly trying to reconcile them. As reader, your task is humble: How do I read the final line of Frost’s “The Road Not Taken”? And your task is dauntingly immense: What do I do when my medium to the universe, language, is caught here and there, betwixt and between? Frost in “The Road Not Taken” is summing up his life, and if there are notes of contentment and self-congratulation, we lack the fixity necessary for complacency; prosodically, we seek in vain some sort of stable perch and purchase. Ironically, all these challenges and ambiguities can be made to disappear with one flick of the poet’s wand. Let’s rewrite the line: And that has made the difference. With the erasure of one tiny word, the problems associated with the final line—of sense, of metrics, of music—vanish on the instant. Here now is our final cinquain: I shall be telling this with a sigh Somewhere ages and ages hence: Two roads diverged in a wood and I— I took the road less traveled by, And that has made the difference. But if the difficulty in the stanza has been removed, so has much of the beauty. It pleases me to think that in a hundred years, two hundred, long after anyone alive today who loves the poem still walks the planet, new readers will find themselves wondering why these simple lines are so uneasily haunting.

More on this book and author:

Learn more about Rhyme’s Rooms by Brad Leithauser.

Browse other books by Brad Leithauser.

Visit our Tumblr to peruse poems, audio recordings, and broadsides in the Knopf poem-a-day series.

To share the poem-a-day experience with friends, pass along this link.

#LeithauserAudio#rhyme's rooms#rhymes rooms#excerpt#poem#poetry#poem-a-day#knopf poetry#brad leithauser

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

So one thing I’ve recently done in my research is trace all the chapter epigraphs to their sources. I thought it would be interesting to give a bit more context in the footnotes. Onegin is such a deeply metaliterary text, and there are a lot of references I didn’t get when I first read it as a teenager. So part of my philosophy in translating it now is to go track down the things Pushkin references. Especially with poetry references, I like to find an illustrative passage to add to the footnotes, and (if it’s not an English poem) translate. It’s all well and good for the original to just say: “go read Prince Vyazemsky’s poem on snow”, but that’s not useful to someone reading Onegin in translation.

Anyway, this led to an interesting discovery. It turns out all the editions I’ve managed to get my hands on so far* make the same mistake with the Petrarch quote at the top of Ch.6. It should be:

Là, sotto i giorni nubilosi e brevi, Nasce una gente, a cui ’l morir non dole.

[Where skies cloud over and days are brief, There lives a people untroubled by death.]

…but everybody seems to print it with l’morir instead. Does this trace back to the manuscripts? The first publication? Or did it get introduced later? I don’t know (yet). My own oldest edition is from the late 19th century and also has the mistake, so there’s that at least.

Here’s my understanding of why it should be ’l morir, at least to just jot it down somewhere. Disclaimer that I am not fluent in Italian. I worked through some self-teacher books in my teens, and I can read it well enough for casual research, but it’s not one of my main languages.

1. The article l’- is for nouns that start with a vowel. If we’re using morir [shortened form of morire, “to die”] as a (masculine) noun, I would expect the proper form to be il morir [the act of dying].

2. From what I’ve seen of it, Italian poetry looks like it has syllabic meter. In this poem, we seem to be looking at 11 syllables to the line:

Là, | sot- | -to i | gior- | -ni | nu- | -bi- | -lo- | -si e | bre- | -vi, Na- | -sce u- | -na | gen- | -te, a | cui ’l | mo- | -rir | non | do- | -le.

Of course, take my analysis here with a grain of salt. I’m really going by what I know of Spanish poetry. Part of how syllabic meter works in Spanish is that there’s something called sinalefa where you merge adjacent vowels into the same syllable. As far as I can tell, Italian poetry seems to do something similar. I also know that in Spanish, 11-syllable meter (endecasílabo) is pretty common, and kind of a loose parallel to pentameter in languages that use stress-based meter (ex: English, Russian).

3. In contractions, an apostrophe marks a missing letter. That’s why English has “do not” --> “don’t”, “you are” --> “you’re”, etc. So it looks like here we have: cui il --> cui ’l (pronounced as one syllable) to fit the meter more neatly.

…And in case anyone’s curious, here’s my translation of a slightly longer excerpt from the source (Petrarch’s Canzone I to Giacomo Colonna). I followed the original rhyme scheme, and went with iambic pentameter for the reasons mentioned above.

There is a place on earth with no release From winter, endless ice and frozen snow; The sun’s path lies too far to bring relief: Clouds fill the sky, and days are short below; The people are by nature foes of peace, And death, to them, is no great pain or grief.

*[How many different editions of Onegin will I have by the time I finish my translation? The answer is… let’s just say I have a designated shelf at this point. Sometimes it’s about the illustrations, sometimes it’s about the commentary and bonus material. They’re all useful.]

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Robert Frost, 1874-1963, is rightly regarded as one of the great poets of the 20th century. There are so many excellent poems in his collection, both famous and under-regarded. I will examine five of these: 'Nothing Gold Can Stay', 'In Hardwood Groves', 'Stopping By Woods on a Snowy Evening', 'The Road Not Taken' and 'Fire and Ice'. Many common threads connect these poems: firstly the general technical skill, the precise rhythm and gentle rhyme; then a common perspective on the world, Frost's curious mix of pessimism and contentment where the future is somewhere between complicated and apocalyptic but the present is not yet condemned.

What makes his poetry worth examining is that they are very good, and pleasant to read. The most loosely after all structured is 'In Hardwood Groves', which is only made of three stanzas each containing one line with 8 syllables, two with 9 and one with 10 in an ABCB rhyme scheme. But it is not merely the technical ability to stick to a strict rhyme and meter, but also the knowledge of when to break it for maximum effect that makes his work memorable. 'Nothing Gold Can Stay', for example, is written in iambic trimeter —e.g. "Nature's first green is gold"— until the final, title line, which has only five syllables. This difference makes the line more memorable. The last line sticks in the mind longer. 'Stopping By Woods on a Snowy Evening' uses an AABA rhyme scheme where the B of each stanza is the A of the next. This gives the impression that the structure of the poem is reaching forwards to the future, and ties it all together, and means that when the final stanza is AAAA it feels closed off and ominous. 'The Road Not Taken' breaks traditional rules of punctuation with its two and a half stanza, twelve line opening sentence. The prolonged enjambment gives the poem a stream-of-consciousness feel despite the iambic pentameter and ABAAB rhyme, drawing the reader into the narrator’s decision-making process. It creates a powerfully introspective tone in the poem. Frost’s poetry contains not just a knowledge of the conventions of poetry but also the ability to use and break them when necessary. His work is not rule-bound despite its use formal structure, but rather both neat and alive, so that minor variations in form alter the tone of the text more significantly than would occur in less structured works.

Frost’s works tend to treat the future as a source of anxiety. 'In Hardwood Groves' is the most optimistic of the poems considered, with death required before the fallen leaves can “fill the trees with another shade”, but even here there is a sense that he wishes the world were not as it is: “in some other world” it might be different, but here “in ours” the journey back to life is long and filled with death. 'Nothing Gold Can Stay' is fundamentally about how the future is inevitably worse than the past, as the best ('gold') things will always disappear in the end. The line "So Eden sank to grief" extends this, alluding to the fallen Biblical paradise of a primordial past, thus extending the trajectory beyond the transitory into the inevitable. In 'Stopping By Woods on a Snowy Evening' the future is "miles" long and full of "promises to keep". The dark, cold woods—in the depths of winter, the season when nothing grows, when simply being outside can kill—stand for the darkness of an unnatural death, and they cannot be seen from the village more than any human can look beyond the grave. When the narrator calls them "lovely, dark and deep" as a whole shows the narrator flirting with the idea of dying rather than endure the world. 'The Road Not Taken' casts the future as fixed: that whatever path we take, we will end up wishing things had been different. There is a fundamental cynicism about human nature here: that even when our choices are each "as just as fair" as the other we will still end up thinking of that decision "with a sigh" in times to come. 'Fire and Ice' of course is about the end of the word—not as something that might happen, but rather that “the world will end” in ice or fire. Everything will end, eventually. The future is not merely dark but outright apocalyptic. In each case, the future is far from an unalloyed utopia. Instead it is full of death, regret, and hardship.

It is easy to look at Frost's biography and decide that this pessimism derives straightforwardly from his long struggle with depression, from the continual death and privation that marked his early years. But Frost lived to be 88, with a full life to the end, including a significant role in the election of Kennedy as the president of the United State. To reduce his life to the difficulties is to ignore the material reality of his history, and to ignore the nuances of his work too. For while there is great negativity about the future in his work, the present is not such a source of anxiety.

'In Hardwood Groves' offers a clue at why. The fallen leaves "must go down into the dark decayed", but also will be "put beneath the feet of dancing flowers", a much more positive image. There are two concurrent possible perspectives on 'Stopping By Woods on a Snowy Evening': that his stop by the woods represents suicidal ideation, or that the speaker merely rests from his busy life in a peaceful forest. In the latter interpretation, we can see that even in a difficult world there are chances to rest, rejuvenate before carrying on in a world that still contains some beauty. Dawn is linked to such beauty in 'Nothing Gold Can Stay', which appears each morning, as are the first leaves that grow every spring. Indeed, the ‘unfallen’ state of leaves is called flowers: hardly rare phenomena. And of course flowers and woods and leafy shade are all emanations of nature. The woods themselves in 'The Road Not Taken' are perfectly pleasant: grassy, brightly coloured and unspoiled – not “trodden black”. This is the link among these, that if there is hope in this world it comes not from the works of humanity, but from nature.

Overall Frost’s poetry tells us that while the future is almost certainly going to suck, there is hope for the good and the wonderful to be found, mostly in simple events like a flower, a walk in the woods, and the break of dawn. In our present, there are still sunrises and forests and flowers. Even if Anadarko seems likely to start drilling our seas for oil and no one is doing much of anything against climate change, there are still beautiful things worth protecting, and nature is worth protecting, and we still have snow, at least for now.

0 notes

Text

Ode to Country Music

The fiddle is a violin

The violin, a fiddle

The banjo once a fretless gourd

With skin stretched o’er it’s middle

From foreign lands these tools did come

To set aglow the parlor

To give the plaintive voice a home

And accompany the squalor

For country life is dirty work

Beneath a sapphire dome

It grinds yer nails down to the quick

But there‘s no greater home

So come ye healthy, come ye sick

And sing your hearts content

Sing of pain and love and truth

If you’ve an idyllic bent

—rudysassafras

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chapter 2, 'Fever Dreams'. See if you can spot the limitation I used here? Not sure if it works, but it was fun to try! Woke up early for no particular reason and got this done before work.

More to come, let's see what I can put together tonight :P Rating: Gen

Pairing: Paul/Chris

Words: 129

Tags: Sickfic, Nightmares, Bathing Together (in addition to the above tags)

********************

‘I’ve got you.’

Cold, Chris mumbles. Someone stirs. The sound of fever dreams and restless sleep were well familiar here.

The water runs across the hall - a bath might help to cool the fire that he’s feeling in his bones. But Paul still feels the chill on Chris’s skin. A pyre without flames, the heat’s a ghost, from when his body knew it should be warm. Paul waits and holds his love against his chest.

The door is creaking open, several arms are helping Paul and Chris climb off the bed, and shuffle to the wrought enamel tub.

It works though, don’t you think? Paul said to Chris, when Chris remarked, now that’s some gothic shit, and Paul replied, we are undead. I guess we’ll look the part.

Paul gently dips them both beneath the bubbly water, careful not to injure Chris’s bruisy skin. He leans against the edge, and reaches out to brush the hair from Chris’s face.

Answer below the cut:

I like it better as prose, but I think I still managed to make it scan:

‘I’ve got you.’ Cold, Chris mumbles. Someone stirs. The sound of fever dreams and restless sleep were well familiar here. The water runs across the hall - a bath might help to cool the fire that he’s feeling in his bones. But Paul still feels the chill in Chris’s flesh. A pyre without flames, the heat’s a ghost, from when his body knew it should be warm. Paul waits and holds his love against his chest.

The door is creaking open, several arms are helping Paul and Chris climb off the bed, and shuffle to the wrought enamel tub. It works though, don’t you think? Paul said to Chris, when Chris remarked, Now that’s some gothic shit, and Paul replied, We are undead. I guess we’ll look the part. Paul gently dips them both

beneath the bubbly water, careful not to injure Chris’s bruisy skin. He leans against the edge, and reaches out to brush the hair from Chris’s face.

(it's iambic meter, loosely pentameter/blank verse . i was gonna sneak in a sonnet form but that was too difficult for the wee hours).

It's supposed to be poetic but not like A Poem if that makes sense, I'm still just writing a story here.

Hey, a little vampire drabble since we’re just over week away from Halloween! Not sure if I want this to be part of the bigger vampire universe I’ve been daydreaming, but I wanted to do a sickfic sort of thing here.

I’ll post it on ao3 when im not on mobile since tagging on mobile sucks lol.

Fangs for reading!

Title: One/Another

Rating: Gen

Pairing: Paul/Chris

Words: 100

Tags: Vampires, Established Relationship, Sickfic, Fluff, Comfort

Paul is a vampire, and Chris is becoming one. A story about healing and sickness.

**********

‘I don’t wanna get you sick.’

‘Too late for me, remember?’ He wants to say, I’d live anyway, but. Not technically. ‘Had your juice?’

‘Yeah. Stayed down.’

‘I’m sorry baby, it’s gonna suck for a bit.’

At least he’d got some food in. Nursing fledglings was an art, especially the in-betweens when the body didn’t know if it was more alive or undead.

Paul crawls under the covers, cuddles Chris close. If he can’t lend heat, he can at least give comfort.

‘Get some sleep,’ he says softly. And when he kisses Chris’s forehead, it’s a degree cooler than before.

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Seven poems

1. It was a tradition in that family that the oldest child in each generation had a word from the poem as their middle name. In the days after the birth, the parents would go to this or that poet, as the times dicatated, consulting on what the next word of the poem should be, and what would make the most auspicious name. But times changed. After a few hundred years, the first line of the poem became awkward and old-fashioned. The modern poets tried to rescue it with changes to the meter and to the rhyming scheme amongst the younger generations. But the poem branched, spreading itself between successive sets of twins; then for a hundred years it became immoral and was propagated only through initials and code; and then the first verse was lost entirely in the flight from the old country. Today it is headless and meandering, and many of those who are its hosts are unaware. But still it continues.

2. It was a found poem. The place it was found was several hundred miles from where it had been lost and, because of this, the local newspaper ran a heartwarming story about the benefits of microchipping your poems. It turned out that the poem had been written in the dust on the back of a van and had been photographed in a distant city before the rain came, subsequently surviving on the kind attention of strangers.

3. This poem was parasitic upon lovers, worming its way in through their eyes or ears and living in their twisting guts, where it waited and grew. The culmination of its lifecycle was the wedding. The poem's hosts would read it to the assembled crowd or the crowd would read it to themselves. In this way it was able to spawn in a dozen more twisting guts, surviving into a new generation.

4. The poem was initially iambic. But it found itself in a library where the custodian was careless with shelving, and as a result many of the iambs got loose and ran off to graze on the lawn outside. There was an incident with a wolf. When the poem's lines were reassembled, it turned out than many of them had lost feet, and others were now unusually stressed. The poem was put out to pasture, where it remains.

5. Then there was the poem that by accident swallowed its own tail, becoming shorter year by year as the process of digestion got to work. After a while, all that remained were a sequence of poem droppings, somewhat resembling full stops. But the old bones of the poem were still there inside the droppings, ready to be extracted by a determined hand with a microscope, tweezers, and a puzzler’s brain.

6. The poem-hunters finally tracked it down at the back of the corner shop after dark, behind the bins. They held a knife at its throat and demanded all its rhymes. But the poem had none, having gone completely blank from terror. Later on a few limp words were spotted draped over a lamppost, but they were eaten by gulls before the police could investigate.

7. It was a respectable poem and had a respectable job. It was minding its own business, as usual, when someone opened it up and stored some plums inside. Never mind, thought the poem. At least I will be able to have something other than sincere appreciation for breakfast. But it was not to be.

84 notes

·

View notes

Text

POETRY ANAYLSIS #2

William Butler Yeats “The Second Coming”

This poem is considered to be written in iambic pentameter with very loose meters. This is also one of Yeats’s popular poems because of the imagery and language. It honestly took me a while to fully understand the main concepts of this poem but after reading it several times, I think I got the gist of it. The 1st stanza speaks about the world and the conditions that are being presented and the 2nd stanza speaks of the second coming that is going to take place. In some ways, Yeats believed that something apocalyptic was going to occur. Everything was falling apart and the new age was coming.

Robert Frost “The Road Not Taken”

This poem is a very well known poem throughout Literature. I really enjoy this poem because it deals with 2 roads which have different outcomes. I feel like this poem is very relatable in our modern day life. You take one path where you have struggles but you succeed or you can take another path where you don't struggle but you don't succeed. I feel like this poem brings attention to the choices that you make in life because they can either make or break your life. It’s important to realize that whatever you choose, you’ll always lose other opportunities. So, although the choice isn't difficult, it also isn't easy.

0 notes

Text

I put an extra word in a line when I was trying to remember the Ballad of Reading Gaol and I made it much funnier but it turns out my brain was just trying to compensate for the fact that the line was not iambic and the poem is supposed to be iambic and usually is but Wilde was playing real fast and loose with meter and with the number of syllables per line (for most of the poem the idea for each stanza is 8 syllables per line and 6 syllables per line alternating but a loooot of lines don’t fit exactly)

Anyway I thought it was “...the prison walls around us both / Did suddenly seem to reel” which I thought was funny like “You know what? Come to think of it, the prison walls around us both DID suddenly seem to reel!”

But I can’t make that joke because the actual line is just “Dear Christ! The very prison walls / Suddenly seemed to reel” so actually I got quite a few words wrong

In my defense I have not read the Ballad in a few years because while it’s great at convincing people to give a shit about prisoners it’s not...a very good poem... none of his poems in fact are very good poems...it was not his strong suit

#imho hes GREAT at novels and hes GREAT at plays and hes a very disappointing poet#also imho hes better as a prose writer than a playwright#no one describes settings like he does

0 notes

Text

Eh, the verse translation is already pretty loose with the meter. It's * mostly* in iambic pentameter (a common choice for translators when working with Greek dactylic hexameter), and its not line accurate (the translators note said he averaged about 15 lines for every 12 of the original.) So I'm not sure that it being in verse is to blame here.

But it still may be less accurate than the Oxford translation. The Penguin edition seems to be adding in some extra bits here and there (like Phoebus Apollo instead of just Phobeus) to help out readers who aren't as deeply familiar with the content.

Here is a side by side, by the way, of the Oxford World's Classics copy of the Argonautica I bought that was PRINTED IN PROSE, and the Penguin Classics copy written in verse.

I just...why would anyone prefer it written in prose? Like, it does make the book fewer pages, since you can fit more text per page. But lord, in terms of readability? Awful.

116 notes

·

View notes