#jivin' in be-bop

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

There are some good ‘80s bops in the original Chess album. I already liked “One Night in Bangkok”, but I hadn’t heard “The Arbiter” or “Nobody’s Side” before, and I’m jivin’ to both.

13 notes

·

View notes

Note

i would love some song recs from you, what are you listening to lately?

Of course! Lemme direct you to these^^^ few posts I’ve made recently, they’ve got a bunch of stuff that sum up my recent listening habits. As for some individual songs, I think my song of the week is Road Rage by Mower. Yes it’s like a minute and change, but it hits like a 2x4 to the back of the head in a good way. If you’re into some more chill stuff I would recommend their alter-ego band Slower (it’s lounge jazz instead of hardcore groove punk rap or whatever the fuck). It’s not even a joke, they’re so good, especially their cover of Road Rage. Very reminiscent of Lou Evil by Primer 55 (another very good song). Pretty much anything from Primer is fresh as fuck, but they only have three albums. Another really good one is The Union Underground, and they only have ONE album! And a live EP. You may know them from the best Monday night Raw theme of all time, Across the Nation. Fucking 🔥🔥🔥

Also check out my featured tags and filter the SOTW one, I’ve done one rec a week for a while.

here have too many random-ass recs-

These are all bops/bangers/jams/etc…

0 notes

Video

youtube

Performed by: Uncredited lindy hoppers

Number: “Dynamo A”

Style: Lindy Hop

From: Jivin’ in Be-Bop (1946)

#dance#lindy#lindy hop#dynamo a#dizzy gillespie#dancers#dancing#swing#jazz#swing dancing#swing dance#swing dancers#vintage#retro#1946#1940s#jivin' in be-bop

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

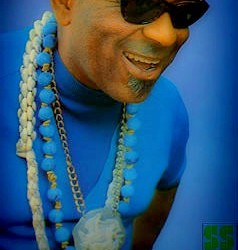

Jazz on Film: Jivin' in Be-Bop (Alexander Productions, 1946)

Dizzy Gillespie & his Orchestra, Helen Humes, ...

14 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Model: Madeleine Sahji Jackson Photographer: Unknown https://www.flickr.com/photos/41717361@N03/7108156057/ #YOUTUBE #KOBO #AALBC #RMEBOOK #RMEBOOKS Where I learned who she was, the flickr source did not cite properly https://www.lipstickalley.com/threads/15-unsung-vintage-black-pinup-models.1268738/ she was a singer for two year in argentina, any more information, please note http://afrodiaspores.tumblr.com/post/59611635806/isitscary-exotic-dancer-madeline-sahji Jivin' in Be-Bop 1947 is a film she danced in , it star Dizzy Gillespie side his band, she dance in it 32:25 to 35:01 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZjIWIJTPwu4 TWo dance numbers from her, both from the film above https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=diz0giFWxT0&feature=youtu.be

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

Helen Humes

Helen Humes (June 23, 1913 – September 9, 1981) was an American jazz and blues singer.

Humes was a teenage blues singer, a vocalist with Count Basie's band, a saucy R&B diva, and a mature interpreter of the classy popular song. Along with other well-known jazz singers of the swing era, Humes helped to shape and define the sound of vocal swing music.

Early life

She was born on June 23, 1913, in Louisville, Kentucky, to Emma Johnson and John Henry Humes. She grew up as an only child. Her mother was a schoolteacher, and her father was the first black attorney in town. In an interview, Humes recalled her parents singing to each other around the house and in a church choir.

Humes was introduced to music in the church, singing in the choir and getting piano and organ lessons given at Sunday school by Bessie Allen, who taught music to any child who wanted to learn. Humes began occasionally playing the piano in a small and locally traveling dance band, the Dandies. This constant involvement in music would lead to her singing career in the mid-1920s.

Career

Early career

Her career began with her first vocal performance, at an amateur contest in 1926, singing "When You're a Long, Long Way from Home" and "I'm in Love with You, That's Why". Her talents were noticed by a guitarist in the band, Sylvester Weaver, who recorded for Okeh Records and recommended her to the talent scout and producer Tommy Rockwell. At the age of 14 Humes recorded an album in St. Louis, singing several blues songs. Two years later, a second recording session was held in New York, and this time she was accompanied by pianist J. C. Johnson. Despite this introduction to the music world, Humes did not make another record for another ten years, during which she completed her high school degree, took finance courses, and worked at a bank, as a waitress, and as a secretary for her father. She stayed home for a while, eventually leaving to visit friends in Buffalo, New York. While there, she was invited to sing a few songs at the Spider Web, a cabaret in town. This brief performance turned into an audition, which turned into a $35-a-week job. She stayed in Buffalo, singing with a small group led by Al Sears.

Cincinnati Cotton Club

While Humes was home in Louisville (she said she always returned home at least twice a year) she got a call from Sears, who was in Cincinnati. He wanted her to sing at Cincinnati's Cotton Club. The Cotton Club was an important venue in the Cincinnati music scene. It was an integrated club that booked and promoted a lot of black entertainers. Humes moved to Cincinnati in 1936 and sang with Sears's band again at the Cotton Club.

Count Basie first heard and approached Humes while she was performing at the Cotton Club in 1937. He asked her to join his touring band to replace Billie Holiday. He told her that she would be paid $35 a week, and she responded, "Oh shucks, I make that here and don't have to go no place!" Not long after this encounter, Humes moved in 1937 to New York City, where John Hammond, an influential talent scout and producer, heard her singing with Sears's band at the Renaissance Club. Through Hammond, she became a recording vocalist with Harry James's big band. Her swing recordings with James included "Jubilee", "I Can Dream, Can't I?", Jimmy Dorsey's composition "It's the Dreamer In Me", and "Song of the Wanderer". In March 1938 Hammond persuaded Humes to join Count Basie's Orchestra, where she would stay for four years.

The Count Basie Orchestra

In the Count Basie Orchestra, Humes gained acclaim as a singer of ballads and popular songs. While she was also a talented blues singer, Jimmy Rushing, another member of the orchestra at the time, held domain over the blues vocals. Her vocals with Basie's band included "Between the Devil and the Deep Blue Sea" and "Moonlight Serenade".

On December 24, 1939, Humes performed with the Count Basie Orchestra and James P. Johnson at the second From Spirituals to Swing concert at Carnegie Hall, produced by John Hammond. After this concert, most of her time with the Basie Orchestra was spent touring. In a 1973 oral history she described life on tour:

I used to pretend I was asleep on the Basie bus, so the boys wouldn't think I was hearing their rough talk. I'd sew buttons on and cook for them, too…in places where it was difficult to get anything to eat…down south. I wasn't interested in drinking and keeping late hours…but my kidneys couldn't stand the punishment of those long rides… then too I got tired of singing the same songs.

For these reasons, Humes left the group in 1942, as her health was not good and the stress of being on tour was too taxing.

Café Society and solo career

While home again in Louisville in 1942, Humes was called by John Hammond and invited to sing at Café Society in New York. She performed frequently there, accompanied by the pianists Teddy Wilson and Art Tatum. During that year, she also performed at the Three Deuces, at the Famous Door with Benny Carter (February), at the Village Vanguard with Eddie Heywood, and on tour with a big band led by the trombonist Ernie Fields.

In 1944, Humes moved to Los Angeles, California, where she spent a lot of time in the studio, recording solo work and movie soundtracks. Some of the soundtracks she recorded were Panic in the Streets and My Blue Heaven. She appeared in the musical film Jivin' in Be-Bop, by Dizzy Gillespie. She also performed and toured with Jazz at the Philharmonic for five seasons. In 1945, she recorded her most popular songs, two jump blues tunes, "Be-Baba-Leba" (Philo, 1945) and "Million Dollar Secret" (Modern, 1950). Despite this, her career stagnated. From the late 1940s to the mid-1950s she made a few recordings, working with different bands and vocalists, including Nat King Cole, but was not nearly as active as she had been. In 1950 she recorded Benny Carter's "Rock Me to Sleep". She bridged the gap between big-band swing jazz and rhythm and blues.

In 1956, Humes toured Australia with the vibraphonist Red Norvo. Their tour was well received, and she returned again in 1962 and 1964. She performed at the Newport Jazz Festival in 1959 and the Monterey Jazz Festival in 1960 and 1962. She toured Europe with the first American Folk Blues Festival in 1962.

She returned to the United States in 1967 to take care of her ailing mother. At this point Humes viewed her singing career as a part of her past. She took a job at a local ammunition plant, sold her record player and her records and stopped singing. From 1967 to 1973, she did not work as a singer, until Stanley Dance persuaded her to perform at the Newport Jazz Festival in 1973. This performance led to a revival of her career in music. The festival was followed with multiple European engagements and some albums made in France for Black and Blue. She sang regularly at the Cookery in New York City from 1974 to 1977.

Humes subsequently performed occasionally in America and at European venues and festivals, including the prestigious Nice Jazz Festival in the mid-1970s. She recorded her final album, Helen, for Muse Records in 1980. She received the Music Industry of France Award in 1973 and the key to the city of Louisville in 1975.

Humes said of her career, "I'm not trying to be a star! I want to work and be happy and just go along and have my friends – and that's my career."

Death

Humes died of cancer in Santa Monica, California, in 1981, at the age of 68. Her family requested donations for cancer research instead of flowers at her funeral. She is buried at the Inglewood Park Cemetery, in Inglewood, California.

Style and reviews

Humes's vocal range was from G3 to C5, as she stated in a letter to the arranger Buck Clayton in preparation for a European tour, along with a list of her preferred songs. According to many critics, her voice was versatile, suiting pop songs and ballads as well as blues. She was compared to Ethel Waters and Mildred Bailey from early in her career and was often recorded singing the blues after her association with Basie. In an interview with the jazz critic Whitney Balliett, Humes explained, "I've been called a blues singer, a jazz singer, and a ballad singer – well, I'm all three, which means I'm just a singer." A review from Downbeat Magazine of her albums Talk of the Town, Helen Comes Back, and Helen Humes with Red Norvo and His Orchestra said the following about her collaboration with Red Norvo:

Norvo's sparkling vibes are the ideal compliment to Helen's lithe, light timbered clarity…Helen is in particularly fine voice…[with] an uncanny resemblance to early Ella [Fitzgerald] in her sound and phrasing.

The review of Helen Comes Back was not as positive but did not fault the singer:

Blues dominates [the album]…[and] although her voice is delightful, the material is too simple to challenge her…Helen is a great deal more than a blues shouter.

Reviews in the Washington Post of her last performances, in Maryland in 1978 and Washington, D.C., in 1980, described her as "beaming and genial at 65" (in 1978) and gave insight into her versatile vocals: "her characteristically light voice [turning] rough as she belted out…'You Can Take My Man But You Can't Keep Him Long'." The reviews also described her use of back phrasing, reminiscent of Billie Holiday's signature style of phrasing a melody in an intimate, personal fashion.

Discography

Midnight at Minton's, Don Byas, 1941

Helen Humes, 1959

Tain't Nobody's Biz-ness if I Do, 1959

Songs I Like to Sing, 1960

Swingin' with Humes, 1961

Helen Comes Back, 1973

Let the Good Times Roll, 1973

Sneakin' Around, 1974

On the Sunny Side of the Street (live), 1974

Helen Humes, 1974

Midsummer Night's Songs (RCA, 1974) with Red Norvo and His Orchestra

Talk of the Town, 1975

Deed I Do (live), 1976

Helen Humes and the Muse All Stars, 1979

The New Year's Eve, 1980

Helen, 1981

With the Count Basie Orchestra

The Original American Decca Recordings (GRP, 1937–39), 1992

With Harry James and His Orchestra

"Jubilee" / "I Can Dream, Can't I?" (78 rpm single, Brunswick 8038, 1937)

"It's The Dreamer In Me" (78 rpm single, Brunswick 8055, 1938)

"Song Of The Wanderer (Where Shall I Go)" (78 rpm single, Brunswick 8067, 1938)

Awards

Hot Club of France Award for Best Album of 1973

Key to the City of Louisville, 1975, 1977

Wikipedia

11 notes

·

View notes

Link

A FINE DOCUMENTARY ABOUT THE REMARKABLE TRUMPETER

Dizzy Gillespie was not only one of the greatest trumpeters of all time and a co-founder of both bebop and Afro-Cuban jazz but was always an enthusiastic educator who taught the jazz world how to play bop.

This 1990 documentary has a generous amount of footage of Gillespie being interviewed (not only in 1988 but at earlier periods), and performance excerpts from several decades, from 1946’s “Things To Come” (along with other clips from that year’s Jivin’ In Bebop film) and his 1962 quintet to rehearsing a European big band that includes Jan Garbarek in 1971 on “Manteca.” There are brief interviews with Milt Jackson, John Lewis, Red Rodney, Max Roach, Johnny Griffin, Dexter Gordon, Kenny Clarke, and James Moody, mostly talking about Dizzy’s big band of 1946-49.

The colorful documentary’s spotlight stays on Gillespie, showing what aspects of his career and life were like rather than being a straight chronological study of his career.

-Scott Yanow

0 notes

Text

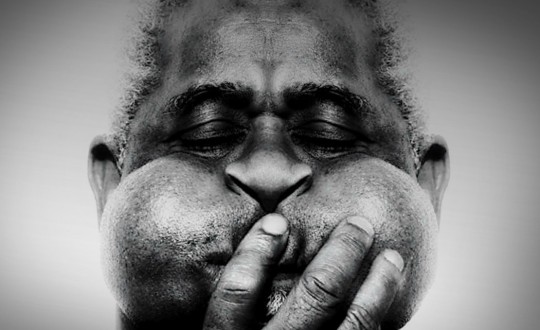

Dizzy Gillespie

John Birks "Dizzy" Gillespie (/ɡᵻˈlɛspi/; October 21, 1917 – January 6, 1993) was an American jazz trumpeter, bandleader, composer, and singer.

AllMusic's Scott Yanow wrote, "Dizzy Gillespie's contributions to jazz were huge. One of the greatest jazz trumpeters of all time (some would say the best), Gillespie was such a complex player that his contemporaries ended up copying Miles Davis and Fats Navarro instead, and it was not until Jon Faddis's emergence in the 1970s that Dizzy's style was successfully recreated [...] Arguably Gillespie is remembered, by both critics and fans alike, as one of the greatest jazz trumpeters of all time."

Gillespie was a trumpet virtuoso and improviser, building on the virtuoso style of Roy Eldridge but adding layers of harmonic complexity previously unheard in jazz. His beret and horn-rimmed spectacles, his scat singing, his bent horn, pouched cheeks and his light-hearted personality were essential in popularizing bebop.

In the 1940s Gillespie, with Charlie Parker, became a major figure in the development of bebop and modern jazz. He taught and influenced many other musicians, including trumpeters Miles Davis, Jon Faddis, Fats Navarro, Clifford Brown, Arturo Sandoval, Lee Morgan, Chuck Mangione, and balladeer Johnny Hartman.

Biography

Early life and career

Gillespie was born in Cheraw, South Carolina, the youngest of nine children of James and Lottie Gillespie. James was a local bandleader, so instruments were made available to the children. Gillespie started to play the piano at the age of four. Gillespie's father died when he was only ten years old. Gillespie taught himself how to play the trombone as well as the trumpet by the age of twelve. From the night he heard his idol, Roy Eldridge, play on the radio, he dreamed of becoming a jazz musician. He received a music scholarship to the Laurinburg Institute in North Carolina which he attended for two years before accompanying his family when they moved to Philadelphia.

Gillespie's first professional job was with the Frank Fairfax Orchestra in 1935, after which he joined the respective orchestras of Edgar Hayes and Teddy Hill, essentially replacing Roy Eldridge as first trumpet in 1937. Teddy Hill's band was where Gillespie made his first recording, "King Porter Stomp". In August 1937 while gigging with Hayes in Washington D.C., Gillespie met a young dancer named Lorraine Willis who worked a Baltimore–Philadelphia–New York City circuit which included the Apollo Theater. Willis was not immediately friendly but Gillespie was attracted anyway. The two finally married on May 9, 1940. They remained married until his death in 1993.

Gillespie stayed with Teddy Hill's band for a year, then left and free-lanced with numerous other bands. In 1939, Gillespie joined Cab Calloway's orchestra, with which he recorded one of his earliest compositions, the instrumental "Pickin' the Cabbage", in 1940. (Originally released on Paradiddle, a 78rpm backed with a co-composition with Cozy Cole, Calloway's drummer at the time, on the Vocalion label, No. 5467).

After a notorious altercation between the two men, Calloway fired Gillespie in late 1941. The incident is recounted by Gillespie, along with fellow Calloway band members Milt Hinton and Jonah Jones, in Jean Bach's 1997 film, The Spitball Story. Calloway did not approve of Gillespie's mischievous humor, nor of his adventuresome approach to soloing; according to Jones, Calloway referred to it as "Chinese music". Finally, their grudge for each other erupted over a thrown spitball. Calloway never thought highly of Dizzy, because he didn't view Dizzy as a good musician. Once during a rehearsal, a member of the band threw a spitball. Already in a foul mood, Calloway decided to blame this on Dizzy. In order to clear his name, Dizzy didn’t take the blame and the problem quickly escalated into a fist fight, then a knife fight. Calloway had minor cuts on the thigh and wrist. After the two men were separated, Calloway fired Dizzy. A few days later, Dizzy tried to apologize to Calloway, but he was dismissed.

During his time in Calloway's band, Gillespie started writing big band music for bandleaders like Woody Herman and Jimmy Dorsey. He then freelanced with a few bands – most notably Ella Fitzgerald's orchestra, composed of members of the late Chick Webb's band, in 1942.

Gillespie avoided serving in World War II. In his Selective Service interview, he told the local board, "in this stage of my life here in the United States whose foot has been in my ass?" He was thereafter classed as 4-F. In 1943, Gillespie joined the Earl Hines band. Composer Gunther Schuller said:

... In 1943 I heard the great Earl Hines band which had Bird in it and all those other great musicians. They were playing all the flatted fifth chords and all the modern harmonies and substitutions and Gillespie runs in the trumpet section work. Two years later I read that that was 'bop' and the beginning of modern jazz ... but the band never made recordings.

Gillespie said of the Hines band, "People talk about the Hines band being 'the incubator of bop' and the leading exponents of that music ended up in the Hines band. But people also have the erroneous impression that the music was new. It was not. The music evolved from what went before. It was the same basic music. The difference was in how you got from here to here to here ... naturally each age has got its own shit".

Then, Gillespie joined the big band of Hines' long-time collaborator Billy Eckstine, and it was as a member of Eckstine's band that he was reunited with Charlie Parker, a fellow member. In 1945, Gillespie left Eckstine's band because he wanted to play with a small combo. A "small combo" typically comprised no more than five musicians, playing the trumpet, saxophone, piano, bass and drums.

Rise of bebop

Bebop was known as the first modern jazz style. However, it was unpopular in the beginning and was not viewed as positively as swing music was. Bebop was seen as an outgrowth of swing, not a revolution. Swing introduced a diversity of new musicians in the bebop era like Charlie Parker, Thelonious Monk, Bud Powell, Kenny Clarke, Oscar Pettiford, and Gillespie. Through these musicians, a new vocabulary of musical phrases was created. With Parker, Gillespie jammed at famous jazz clubs like Minton's Playhouse and Monroe's Uptown House. Parker's system also held methods of adding chords to existing chord progressions and implying additional chords within the improvised lines.

Gillespie compositions like "Groovin' High", "Woody 'n' You" and "Salt Peanuts" sounded radically different, harmonically and rhythmically, from the swing music popular at the time. "A Night in Tunisia", written in 1942, while Gillespie was playing with Earl Hines' band, is noted for having a feature that is common in today's music, a non-walking bass line. The song also displays Afro-Cuban rhythms. One of their first small-group performances together was only issued in 2005: a concert in New York's Town Hall on June 22, 1945. Gillespie taught many of the young musicians on 52nd Street, including Miles Davis and Max Roach, about the new style of jazz. After a lengthy gig at Billy Berg's club in Los Angeles, which left most of the audience ambivalent or hostile towards the new music, the band broke up. Unlike Parker, who was content to play in small groups and be an occasional featured soloist in big bands, Gillespie aimed to lead a big band himself; his first, unsuccessful, attempt to do this was in 1945.

After his work with Parker, Gillespie led other small combos (including ones with Milt Jackson, John Coltrane, Lalo Schifrin, Ray Brown, Kenny Clarke, James Moody, J.J. Johnson, and Yusef Lateef) and finally put together his first successful big band. Gillespie and his band tried to popularize bop and make Gillespie a symbol of the new music. He also appeared frequently as a soloist with Norman Granz's Jazz at the Philharmonic. He also headlined the 1946 independently produced musical revue film Jivin' in Be-Bop.

In 1948 Gillespie was involved in a traffic accident when the bicycle he was riding was bumped by an automobile. He was slightly injured, and found that he could no longer hit the B-flat above high C. He won the case, but the jury awarded him only $1000, in view of his high earnings up to that point.

On January 6, 1953 Gillespie threw a party for his wife Lorraine at Snookie's in Manhattan, where his trumpet's bell got bent upward in an accident, but he liked the sound so much he had a special trumpet made with a 45 degree raised bell, becoming his trademark.

In 1956 Gillespie organized a band to go on a State Department tour of the Middle East which was extremely well received internationally and earned him the nickname "the Ambassador of Jazz". During this time, he also continued to lead a big band that performed throughout the United States and featured musicians including Pee Wee Moore and others. This band recorded a live album at the 1957 Newport jazz festival that featured Mary Lou Williams as a guest artist on piano.

Afro-Cuban music

In the late 1940s, Gillespie was also involved in the movement called Afro-Cuban music, bringing Afro-Latin American music and elements to greater prominence in jazz and even pop music, particularly salsa. Afro-Cuban jazz is based on traditional Afro-Cuban rhythms. Gillespie was introduced to Chano Pozo in 1947 by Mario Bauza, a Latin jazz trumpet player. Chano Pozo became Gillespie's conga drummer for his band. Gillespie also worked with Mario Bauza in New York jazz clubs on 52nd Street and several famous dance clubs such as Palladium and the Apollo Theater in Harlem. They played together in the Chick Webb band and Cab Calloway's band, where Gillespie and Bauza became lifelong friends. Gillespie helped develop and mature the Afro-Cuban jazz style.

Afro-Cuban jazz was considered bebop-oriented, and some musicians classified it as a modern style. Afro-Cuban jazz was successful because it never decreased in popularity and it always attracted people to dance to its unique rhythms. Gillespie's most famous contributions to Afro-Cuban music are the compositions "Manteca" and "Tin Tin Deo" (both co-written with Chano Pozo); he was responsible for commissioning George Russell's "Cubano Be, Cubano Bop", which featured the great but ill-fated Cuban conga player, Chano Pozo. In 1977, Gillespie discovered Arturo Sandoval while researching music during a tour of Cuba.

Later years

His biographer Alyn Shipton quotes Don Waterhouse approvingly that Gillespie in the fifties "had begun to mellow into an amalgam of his entire jazz experience to form the basis of new classicism". Another opinion is that, unlike his contemporary Miles Davis, Gillespie essentially remained true to the bebop style for the rest of his career.

In 1960, he was inducted into the Down Beat magazine's Jazz Hall of Fame.

During the 1964 United States presidential campaign the artist, with tongue in cheek, put himself forward as an independent write-in candidate. He promised that if he were elected, the White House would be renamed the Blues House, and he would have a cabinet composed of Duke Ellington (Secretary of State), Miles Davis (Director of the CIA), Max Roach (Secretary of Defense), Charles Mingus (Secretary of Peace), Ray Charles (Librarian of Congress), Louis Armstrong (Secretary of Agriculture), Mary Lou Williams (Ambassador to the Vatican), Thelonious Monk (Travelling Ambassador) and Malcolm X (Attorney General). He said his running mate would be Phyllis Diller. Campaign buttons had been manufactured years before by Gillespie's booking agency "for publicity, as a gag", but now proceeds from them went to benefit the Congress of Racial Equality, Southern Christian Leadership Conference and Martin Luther King, Jr.; in later years they became a collector's item. In 1971 Gillespie announced he would run again but withdrew before the election for reasons connected to the Bahá'í Faith.

Dizzy Gillespie, a Bahá'í since 1968, was one of the most famous adherents of the Bahá'í Faith. It brought him to see himself as one of a series of musical messengers, part of a succession of trumpeters somewhat analogous to the series of prophets who bring God's message in religion. The universalist emphasis of his religion prodded him to see himself more as a global citizen and humanitarian, expanding on his already-growing interest in his African heritage. His increasing spirituality brought out a generosity in him, and what author Nat Hentoff called an inner strength, discipline and "soul force". Gillespie's conversion was most affected by Bill Sears' bookThief in the Night. Gillespie spoke about the Bahá'í Faith frequently on his trips abroad. He is honored with weekly jazz sessions at the New York Bahá'í Center in the memorial auditorium.

Gillespie published his autobiography, To Be or Not to Bop, in 1979.

Gillespie was a vocal fixture in many of John Hubley and Faith Hubley's animated films, such as The Hole, The Hat, and Voyage to Next.

In the 1980s, Gillespie led the United Nation Orchestra. For three years Flora Purim toured with the Orchestra and she credits Gillespie with evolving her understanding of jazz after being in the field for over two decades. David Sánchez also toured with the group and was also greatly influenced by Gillespie. Both artists later were nominated for Grammy awards. Gillespie also had a guest appearance on The Cosby Show as well as Sesame Street and The Muppet Show.

In 1982, Gillespie had a cameo appearance on Stevie Wonder's hit "Do I Do". Gillespie's tone gradually faded in the last years in life, and his performances often focused more on his proteges such as Arturo Sandoval and Jon Faddis; his good-humoured comedic routines became more and more a part of his live act.

In 1988, Gillespie had worked with Canadian flautist and saxophonist Moe Koffman on their prestigious album Oo Pop a Da. He did fast scat vocals on the title track and a couple of the other tracks were played only on trumpet.

In 1989 Gillespie gave 300 performances in 27 countries, appeared in 100 U.S. cities in 31 states and the District of Columbia, headlined three television specials, performed with two symphonies, and recorded four albums. He was also crowned a traditional chief in Nigeria, received the Ordre des Arts et des Lettres; France's most prestigious cultural award. He was named Regent Professor by the University of California, and received his fourteenth honorary doctoral degree, this one from the Berklee College of Music. In addition, he was awarded the Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award the same year. The next year, at the Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts ceremonies celebrating the centennial of American jazz, Gillespie received the Kennedy Center Honors Award and the American Society of Composers, Authors, and Publishers Duke Ellington Award for 50 years of achievement as a composer, performer, and bandleader. In 1993 he received the Polar Music Prize in Sweden.

November 26, 1992 at Carnegie Hall in New York City, following the Second Bahá'í World Congress was Gillespie's 75th birthday concert and his offering to the celebration of the centenary of the passing of Bahá'u'lláh. Gillespie was to appear at Carnegie Hall for the 33rd time. The line-up included: Jon Faddis, Marvin "Doc" Holladay, James Moody, Paquito D'Rivera, and the Mike Longo Trio with Ben Brown on bass and Mickey Roker on drums. But Gillespie didn't make it because he was in bed suffering from cancer of the pancreas. "But the musicians played their real hearts out for him, no doubt suspecting that he would not play again. Each musician gave tribute to their friend, this great soul and innovator in the world of jazz." In 2002, Gillespie was posthumously inducted into the International Latin Music Hall of Fame for his contributions to Afro-Cuban music.

Gillespie also starred in a film called The Winter in Lisbon released in 2004. He has a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame at 7057 Hollywood Boulevard in the Hollywood section of the City of Los Angeles. He is honored by the December 31, 2006 – A Jazz New Year's Eve: Freddy Cole & the Dizzy Gillespie All-Star Big Band at The John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts.

Death and legacy

A longtime resident of Englewood, New Jersey he died of pancreatic cancer January 6, 1993, aged 75, and was buried in the Flushing Cemetery, Queens, New York City. Mike Longo delivered a eulogy at his funeral. He was also with Gillespie on the night he died, along with Jon Faddis and a select few others.

At the time of his death, Gillespie was survived by his widow, Lorraine Willis Gillespie (d. 2004); a daughter, jazz singer Jeanie Bryson; and a grandson, Radji Birks Bryson-Barrett. Gillespie had two funerals. One was a Bahá'í funeral at his request, at which his closest friends and colleagues attended. The second was at the Cathedral of Saint John the Divine in New York City open to the public.

As a tribute to him, DJ Qualls' character in the 2002 American teen comedy film The New Guy was named Dizzy Gillespie Harrison.

The Marvel Comics current Hawkeye comic written by Matt Fraction features Gillespie's music in a section of the editorials called the "Hawkguy Playlist".

Also, Dwight Morrow High School, the public high school of Englewood, New Jersey, renamed their auditorium the Dizzy Gillespie Auditorium, in memory of him.

In 2014, Gillespie was inducted into the New Jersey Hall of Fame.

Style

Gillespie has been described as the "Sound of Surprise". The Rough Guide to Jazz describes his musical style:

"The whole essence of a Gillespie solo was cliff-hanging suspense: the phrases and the angle of the approach were perpetually varied, breakneck runs were followed by pauses, by huge interval leaps, by long, immensely high notes, by slurs and smears and bluesy phrases; he always took listeners by surprise, always shocking them with a new thought. His lightning reflexes and superb ear meant his instrumental execution matched his thoughts in its power and speed. And he was concerned at all times with swing—even taking the most daring liberties with pulse or beat, his phrases never failed to swing. Gillespies’s magnificent sense of time and emotional intensity of his playing came from childhood roots. His parents were Methodists, but as a boy he used to sneak off every Sunday to the uninhibited Sanctified Church. He said later, ‘The Sanctified Church had deep significance for me musically. I first learned the significance of rhythm there and all about how music can transport people spiritually.'"

In Gillespie's obituary, Peter Watrous describes his performance style:

"In the naturally effervescent Mr. Gillespie, opposites existed. His playing—and he performed constantly until nearly the end of his life—was meteoric, full of virtuosic invention and deadly serious. But with his endlessly funny asides, his huge variety of facial expressions and his natural comic gifts, he was as much a pure entertainer as an accomplished artist."

Wynton Marsalis summed up Gillespie as a player and teacher:

"His playing showcases the importance of intelligence. His rhythmic sophistication was unequaled. He was a master of harmony—and fascinated with studying it. He took in all the music of his youth—from Roy Eldridge to Duke Ellington—and developed a unique style built on complex rhythm and harmony balanced by wit. Gillespie was so quick-minded, he could create an endless flow of ideas at unusually fast tempo. Nobody had ever even considered playing a trumpet that way, let alone had actually tried. All the musicians respected him because, in addition to outplaying everyone, he knew so much and was so generous with that knowledge..."

Bent trumpet

Gillespie's trademark trumpet featured a bell which bent upward at a 45-degree angle rather than pointing straight ahead as in the conventional design. According to Gillespie's autobiography, this was originally the result of accidental damage caused by the dancers Stump and Stumpy falling onto the instrument while it was on a trumpet stand on stage at Snookie's in Manhattan on January 6, 1953, during a birthday party for Gillespie's wife Lorraine. The constriction caused by the bending altered the tone of the instrument, and Gillespie liked the effect. He had the trumpet straightened out the next day, but he could not forget the tone. Gillespie sent a request to Martin to make him a "bent" trumpet from a sketch produced by Lorraine, and from that time forward played a trumpet with an upturned bell.

Gillespie's biographer Alyn Shipton writes that Gillespie probably got the idea for a bent trumpet when he saw a similar instrument in 1937 in Manchester, England, while on tour with the Teddy Hill Orchestra. According to this account (from British journalist Pat Brand) Gillespie was able to try out the horn and the experience led him, much later, to commission a similar horn for himself.

Whatever the origins of Gillespie's upswept trumpet, by June 1954 he was using a professionally manufactured horn of this design, and it was to become a visual trademark for him for the rest of his life. Such trumpets were made for him by Martin (from 1954), King Musical Instruments (from 1972) and Renold Schilke (from 1982, a gift from Jon Faddis). Gillespie favored mouthpieces made by Al Cass. In December 1986 Gillespie gave the National Museum of American History his 1972 King "Silver Flair" trumpet with a Cass mouthpiece. In April 1995, Gillespie's Martin trumpet was auctioned at Christie's in New York City, along with instruments used by other famous musicians such as Coleman Hawkins, Jimi Hendrix and Elvis Presley. An image of Gillespie's trumpet was selected for the cover of the auction program. The battered instrument was sold to Manhattan builder Jeffery Brown for $63,000, the proceeds benefiting jazz musicians suffering from cancer.

Wikipedia

13 notes

·

View notes