#jakaltek

Text

Exploring the Rich Culture of the Jakaltek People and Jakaltek Language

Jakaltek: Unveiling the Mysteries of a Mayan Language

View On WordPress

#Guatemala Culture#indigenous languages#Jakaltek#Jakaltek Phonology#Language Preservation#Linguistic Diversity#Mayan language#Mayan Linguistics

0 notes

Photo

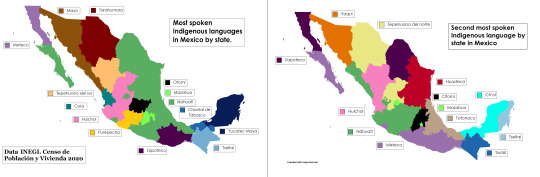

First and Second Most spoken Indigenous languages in Mexico by state

by mexidominicarican8

<div class="md"><p>60 Most spoken Indigenous languages in Mexico (ones that appear on the map are in bold)</p> <ol> <li><strong>Nahuatl</strong> (Nahuatl, Nahuat, Nahual, Macehualtlahtol, Melatahtol): 1,651,958 speakers</li> <li><strong>Yucatec Maya</strong> (Maaya t'aan): 774,755 speakers</li> <li><strong>Tzeltal Maya</strong> (K'op o winik atel): 589,144 speakers</li> <li><strong>Tzotzil Maya</strong> (Batsil k'op): 550,274 speakers</li> <li><strong>Mixtec</strong> (Tu'un sávi): 526,593 speakers</li> <li><strong>Zapotec</strong> (Diidxaza): 490,845 speakers</li> <li><strong>Otomí</strong> (Hñä hñü): 298,861 speakers</li> <li><strong>Totonac</strong> (Tachihuiin): 256,344 speakers</li> <li><strong>Ch'ol Maya</strong> (Winik): 254,715 speakers</li> <li>Mazatec (Ha shuta enima): 237,212 speakers</li> <li><strong>Huastec</strong> (Téenek): 168,729 speakers</li> <li><strong>Mazahua</strong> (Jñatho): 153,797 speakers</li> <li>Tlapanec (Me'phaa): 147,432 speakers</li> <li>Chinantec (Tsa jujmí): 144,394 speakers</li> <li><strong>Purépecha</strong> (P'urhépecha): 142,459 speakers</li> <li>Mixe (Ayüük): 139,760 speakers</li> <li><strong>Tarahumara</strong> (Rarámuri): 91,554 speakers</li> <li>Zoque: 74,018 speakers</li> <li>Tojolab'al (Tojolwinik otik): 66,953 speakers</li> <li><strong>Chontal de Tabasco</strong> (Yokot t'an): 60,563 speakers</li> <li><strong>Huichol</strong> (Wixárika): 60,263 speakers</li> <li>Amuzgo (Tzañcue): 59,884 speakers</li> <li>Chatino (Cha'cña): 52,076 speakers</li> <li><strong>Tepehuano del sur</strong> (Ódami): 44,386 speakers</li> <li><strong>Mayo</strong> (Yoreme): 38,507 speakers</li> <li>Popoluca (Zoquean) (Tuncápxe): 36,113 speakers</li> <li><strong>Cora</strong> (Naáyarite): 33,226 speakers</li> <li>Trique (Tinujéi): 29,545 speakers</li> <li><strong>Yaqui</strong> (Yoem Noki or Hiak Nokpo): 19,376 speakers</li> <li>Huave (Ikoods): 18,827 speakers</li> <li>Popoloca (Oto-manguean): 17,274 speakers</li> <li>Cuicatec (Nduudu yu): 12,961 speakers</li> <li>Pame (Xigüe): 11,924 speakers</li> <li>Mam (Qyool): 11,369 speakers</li> <li>Q'anjob'al: 10,851 speakers</li> <li><strong>Tepehuano del norte</strong>: 9,855 speakers</li> <li>Tepehua (Hamasipini): 8,884 speakers</li> <li>Chontal de Oaxaca (Slijuala sihanuk): 5,613 speakers</li> <li>Sayultec: 4,765 speakers</li> <li>Chuj: 3,516 speakers</li> <li>Acateco: 2,894 speakers</li> <li>Chichimeca jonaz (Úza): 2,364 speakers</li> <li>Ocuilteco (Tlahuica): 2,238 speakers</li> <li>Guarijío (Warihó): 2,139 speakers</li> <li>Q'eqchí (Q'eqchí): 1,599 speakers</li> <li>Matlatzinca: 1,245 speakers</li> <li>Pima Bajo (Oob No'ok): 1,245 speakers</li> <li>Chocho (Runixa ngiigua): 847 speakers</li> <li>Lacandón (Hach t'an): 771 speakers</li> <li>Seri (Cmiique iitom): 723 speakers</li> <li>Kʼicheʼ: 589 speakers (1.1 million in Guatemala)</li> <li>Kumiai (Ti'pai): 500 speakers (110 in USA) </li> <li>Jakaltek (Poptí) (Abxubal): 481speakers</li> <li>Texistepequeño: 368 speakers</li> <li>Paipai (Jaspuy pai): 231 speakers</li> <li>Pápago (O'odham): 203 speakers</li> <li>Ixcatec: 195 speakers</li> <li>Cucapá (Kuapá): 180 speakers (370 in USA)</li> <li>Kaqchikel: 169 speakers (440,000 in Guatemala)</li> <li>Mochoʼ: 126 speakers</li> </ol> </div>

107 notes

·

View notes

Text

Languages of the world

Jakaltek (jabʼ xubʼal)

Basic facts

Number of native speakers: 33,000

Recognized minority language: Guatemala

Also spoken: Mexico

Script: Latin, 30 letters

Grammatical cases: 0

Linguistic typology: agglutinative, VSO, ergative-absolutive

Language family: Mayan, Q'anjobalan-Chujean, Q'anjobalan, Kanjobal-Jacaltec

Number of dialects: 2

History

1980s - government persecution

Writing system and pronunciation

These are the letters that make up the script: a b' ch ch' e h i k k' l m n n̈ o p q r s t t' tx tx' tz tz' u w x ẍ y '.

Jakaltek is one of the only two languages in the world that uses n̈.

Stress is placed at the beginning of words.

Grammar

Nouns are marked for number (singular and plural) and for possession (person and number of their possessor) using suffixes.

Jakaltek also contrasts inalienable (my photo [in which I am depicted]) and alienable (my photo [taken by me]) possession. The language makes use of four systems of numeral classifiers according to whether the object is animate or inanimate and to its shape.

Verbs are marked for tense, aspect, person (both subject and object), and number. Unlike person and number which are marked using affixes placed before the root, tense and aspect markers are placed both before and after the stem in the form of prefixes and suffixes.

Dialects

There are two dialects: Eastern and Western. They are more or less mutually intelligible in speech, but not in written form.

25 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Between May 5 and June 9, more than 2,000 immigrant families were stopped at the U.S.-Mexico border. Government agents and agencies have failed to identify Indigenous individuals and families after apprehension and because many Indigenous migrants speak neither English or Spanish, language barriers can lead to human and Indigenous rights violations and increase the risk for family separations.

According to a 2015 report by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), K’iche’, Mam, Achi, Ixil, Awakatek, Jakaltek and Qanjobal — Mayan dialects spoken in what is currently Guatemala and southern Mexico — were “represented within the ICE family residential facilities.” In Latin America, at least 560 Indigenous languages are spoken by 780 different tribal and ethnic groups.

For ICE, Indigenous languages pose a challenge for interpreters. However, data on Indigenous language speakers encountered by law-enforcement officials at the border are held by Customs and Border Protection, which did not respond to requests for those statistics.

“There’s certainly been an increase (in Indigenous language speakers),” said John Haviland, an anthropological linguist at University of California, San Diego and Tzotzil interpreter. “No question at all.” [...]

Haviland provides interpretation services for Homeland Security, court proceedings and medical situations. He said that because of language barriers, child separation — at least in the case of Indigenous families who speak no Spanish or English — had been a common practice, at least anecdotally, even before the Trump administration’s policy.

“A massive number of family law cases basically end up with children being taken away,” said Haviland. “They do it more often with Indigenous migrants than with Spanish migrants, and the reason is very simple: Nobody can actually contradict the claim that can be made by social services that an Indigenous mom is an incompetent mom, because basically, they can’t talk to the mom.”

People are logged in the system by nationality, not tribal affiliation. That means Indigenous legal frameworks, international standards and human rights can be ignored by federal agencies.

“The question of Indigeneity in Latin America is very different than it is in the countries that were colonized by Great Britain,” said Rebecca Tsosie, regents’ professor of law and faculty co-chair of the Indigenous People’s Law and Policy Program at the University of Arizona. “We see a community that still speaks their Indigenous language, that still dresses the way they have always dressed. That’s the demarcation that, culturally, they’ve remained distinct.”

In the U.S., she said, Indigeneity is seen more as a political identity.

“So, if you’re not an enrolled member of a federally recognized tribe, eyebrows go up: Are you really Indigenous?” she said. “There are politics around Indigeneity, and it revolves around the United States’ framework. So, the idea is one of exceptionalism.”

This becomes an issue when applying international standards, like the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People, which the United States endorsed in 2010. Under the declaration, Indigenous peoples have a collective status and hold rights as a collective people. It also states that Indigenous people have a right to stay in their family unit without impairment.

“The Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People would say that is a violation of their human rights,” said Tsosie. “They have a right to exist in their family unit without the government breaking that up.”

Indigenous immigrants face unique challenges at the border: Language barriers mean Indigenous families may be more likely to be split up.

#linguistics#mayan languages#k'iche'#mam#achi#ixil#awakatek#jakaltek#qanjobal#indigenous languages#indigenous peoples#us politics#american politics#ice#homeland security#john haviland#rebecca tsosie#linguistic discrimination#declaration on the rights of indigenous people#immigration

273 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Tzeltal Mayan ethnomedical syndrome cha’lam tsots and the Mixe mäjts baajy represent regional variations of “second-hair” illness found in several Mesoamerican cultures. Glossed “second hair” or “two hairs,” cha’lam tsots is a complex Tzeltal Mayan ethnomedical syndrome identified by the presence of short, spiny hairs growing close to the scalp, under the normal layer of hair. It is a serious, potentially fatal condition that is believed by the Tzeltal to be caused by physical trauma to individuals, mostly children. Hair loss, diarrhea, fever, edema, loss of appetite, and general debility are primary elements of cha’lam tsots.

An illness nearly identical to cha’lam tsots has been reported among the Mixe of Oaxaca, Mexico. The Mixe mäjts baajy, or “two head hairs,” primarily afflicts infants and is marked by diarrhea, anemia, a swollen body, puffed cheeks, and “numerous, fine shining ahirs, or ‘small spines,’ growing on the head.” As with the Tzeltal Mayan cha’lam tsots, mäjts baajy is considered a serious and potentially fatal illness, primarily affecting children. Similar “second-hair” illnesses have also been identified among the Cakchiquel Maya of Guatemala and the Jacaltecos and Motozintelcos of the Guatemala-Mexico border region. In all cultures, the core ethnomedical description of the illnesses, its primary sufferers, prognosis, and modes of treatment are nearly identical.

- George E. Luber, “‘Second-Hair’ Illness in Two Mesoamerican Cultures: A Biocultural Study of the Ethnomedical Diagnosis of Protein-Energy Malnutrition” in Nutritional Anthropology 25(2): Fall 2002 (link)

#george e. luber#frontpage#tzeltal#maya#mexico#mixe#kaqchikel#guatemala#jakaltek#motozintleco#free#article#nutritional anthropology

0 notes