#it really speaks to my experience as a lesbian in the midwest

Note

Hey makenzie I have a question, how did you become a sex educator?

I mean, the dummy simple answer is that I just. started educating people about sex.

the less simple answer is a lot longer, but I’ll try to condense it down and keep it reasonably spaced out for readability:

at age 17 I was learning baby’s first feminism, and for some reason or another latched on pretty hard to the realization that American sex education is overwhelmingly inadequate, misogynistic, and exclusionary to anyone who’s not cis and straight (although I’ll be honest and say that at the time I was far from well-educated in issues pertaining to trans identities). I started going out of my way to educate myself where I could, with a lot of help from youtubers like the since-disgraced Laci Green and the still-excellent Dr. Lindsey Doe.

when I was 18, near the start of my second semester of college, I posted some screenshots of a conversation between myself and my younger sister, who was then enduring our high school’s infamously unhelpful sex education and seeking some better information. I was a nobody with no followers but thought people might like to see it, and boy was I right. overnight I had more asks than I had ever thought possible, asking for info on the clit, pubic hair, masturbation, navigating relationships, and more.

being an 18 year old virgin, I didn’t have wise personal insight to offer an all - or even most - of those questions. but you’d be amazed how far some basic research skills and a little common sense will get you. here’s a diagram to show you exactly where the clitoris is, here’s a Teen Vogue article explaining several different ways to remove your pubes if you want to, no you probably shouldn’t keep masturbating like that if it hurts, dump him, etc.

so a thing I was interested in started to become a thing I was actively advising other people about, and that started to expand into my real life. when I wasn’t on tumblr I was serving on the executive boards of my campus’ LGBTQ student org and a feminist org that I co-founded with a dear friend, and those were both GREAT platforms to start leading presentations about sex ed and sexuality. so I did! and my public speaking skills fucking flourished.

sex ed also crept into my academics, because academia is really about finding a niche you don’t hate and riding it for everything it’s worth. I spent an entire semester doing independent research under my advisor’s supervision identifying sources of sexual stigma in family, media, and education and how that shame perpetuates cyclically across generations.

I also spent an entire summer depressed out of my mind researching the social construction of virginity and how it fails to adequately encompass the experiences of many queer people, and that turned into a lot of thinking which turned into the very first workshop I ever took to a conference - shout out to the Midwest Bisexual Lesbian Gay Transgender and Asexual College Conference 2018!

in my final semester of undergrad, my advisor organized for me to shadow an Our Whole Lives class, an amazingly comprehensive, body-friendly, inclusive sex ed program from kids in grade four through six. it was probably the coolest thing I had ever done, and I knew I had to get certified to lead classes myself - which I did, about a year ago! and I taught my first class last fall.

anyway, now I’ve graduated with a BA in sociology and gender studies, I work part time as a program assistant in my university’s LGBT student services office and part time in a public library, I’ll teach local OWL classes whenever they’re offered and give workshops whenever I’m able (shout out again to MBLGTACC 2019, that was dope!), and of course I’m still sex educating here on bluehell dot com.

I really hope you weren’t asking for a step-by-step guide to becoming a sex educator yourself, because this is pretty much impossible to replicate.

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

Work Safety

It is very neat to feel safe at work.

[Content warning: mild transphobia, misunderstanding, and internalized transphobia. Mentions of the Supreme Court.]

Context: A little over a month ago, I moved from my hometown in the midwest to New Orleans, LA. I knew I loved the city from past visits, but I didn’t actually know what I was getting into. Two days into being here, I walked into a small grocery store and applied for a job. I’ve been there now for three weeks.

There is a lesson here in allyship, and in living your truth loudly enough that other people grab your wavelength. On my second day of training, I’d spent enough time with my coworker to figure he was safe. He’s well over six feet tall, built like a mountain, hands big enough to grab whole sealed meats from the deli case one-handed without dropping them. He’s also incredibly friendly, very outgoing, and he has the voice.

When I told him my pronouns, he jumped right on it and asked if it was okay to spread the word around. I agreed. I was excited by his support and help here (I’d gotten that sort of support from my college roommates, but never from anyone else, and I figured they were sort of a fluke in that regard. The kind of perks you get from found family, not from strangers).

But the next day I notice other people making the effort, stumbling occasionally, but correcting themselves. Which has never happened before.

And a few days later, when someone messes up and doesn’t notice, I somehow find the guts to speak up. They say something along the lines of “SHE’ll help you out--” and I go to help, of course, but also chime in an audible, “THEY. But yes.”

Anytime I corrected pronouns in front of my parents, my mother would roll her eyes and go off about how I was her little girl, and I can’t expect my family to just change their view of me like that, I can’t expect them to change their language, just let it go, they’re family. I have an otherwise good relationship with my mother, so I never pushed too hard. Besides brief rants from my father about “the way God made us” and “there’s only two genders” and “taking it out of God’s hands” I never heard much from him, but I knew his opinions. My grandmother would claim support, but would also corner me to whisper about how “nobody ACTUALLY wants to be a woman, you just have to pretend,” and would go off on screaming homophobic rants when she was drunk. Never told her I was a lesbian, or bisexual, or anything. She’ll find out I’m trans when there’s no more hiding it.

So those were the responses I was used to. At my last job, as a nurse’s aide in an old folks home, any mention of pronouns or corrections at all were met with a chuckled, “Oh right, my bad, of course,” but my coworkers were far too busy with other things to remember beyond the conversation. The few who did would persistently get my pronouns wrong, saying things like, “Don’t call [Name] a girl, she’s a THEY.” As if they were a noun all to itself, a new way of being a person. Like how they used to say “she’s a he-she” “she’s a queer” “she’s a butch” turning something into a descriptor where it doesn’t belong, making you feel a bit... odd. Even if queer or butch or they are ways you describe yourself, when someone takes your word and frames it that way around you, you still feel off.

But that doesn’t happen here. Coworkers here, even supervisors, say, “Right, I’m sorry,” and correct it. Every time.

I wasn’t expecting the chef I worked for to give two singular fucks about my pronouns, let alone about me. I expected a chef to be like a nurse-- busy, superior, a bit callous and with a hundred more important things to care about than what I had to say. I just wipe the butts/chop the vegetables/scrub the dishes. Who cares what kind of gender-freak I am while I do it, so long as I get my job done. Who cares what they call me. They don’t owe me anything, right?

But he’s gone out of his way to be careful about it. Correcting pronouns, every time, and he’s told me twice now that he’s “really trying to pay attention to it, and to let other people know too” and he “doesn’t want to slip up.” This is a mid-forties rocker dude who wears bandanas and cargo shorts and signs along badly to the Beasty Boys. Past experience has taught me not to trust these men. He’s changing his mind.

And maybe I’m feeling a little burgeoned by the Supreme Court’s decision, even though I know it’s rather arbitrary. A friend of mine has been working in the factories back home since he finished high school, and any time words gotten out that He’s not just a butch woman, he’s been out the door by the end of the week. If they can’t fire you for being trans, they’ll come up with another excuse.

Regardless, I’ve been feeling brave. Maybe it’s the testosterone. Maybe it’s the camaraderie. Maybe it’s my girlfriend’s support, or the Supreme Court, or the uprisings, or nine hundred miles between me and my parents--

But yesterday, when a coworker slipped up with the “he/she/they” situation for at least the fifth time that day, I laughed loudly and yelled, “She? Just you wait till I grow a beard, then you’ll stop with this SHE business!”

And they laughed. And the chef added, “Yeah, or the voice drop,” because I’ve mentioned it several times before. I’m just so excited for these new changes, excited to be put together correctly, excited for less people to fuck up about me. And I don’t want to drive my girlfriend crazy talking about it, so I gush at my coworkers, explaining the voice drop, the facial hair (maybe), the masculinization, the fact that a lot of things will be underway at the five month mark, which is conveniently right in time for Christmas (God help us).

What I’m saying here is that things are good, and this city is good. I didn’t think it would make such a difference. I spent so much time around people who thought I was some sort of defect or odd-ball or attention seeker that I started to believe them, and to be treated like a normal person? To say something and have people listen? To be given respect?

I almost can’t believe it’s possible.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ngowo - November 16th, 2019

Ngowo: Growing up as a little girl in Cameroon, where I'm originally from, there were clear expectations of what a girl grew up to be, what a boy grew up to be. I never saw reflections of myself. But it was something that I felt is something that was real. And it was something that I just knew existed deep down inside of me. But I kept it a secret from everyone because you don't see people that look like you, and you don't see reflections of what you're feeling. It's hard to express that to the larger community. And I think [that fear] is all Christianity-based.

Going back with my wife, there are Africans in their 60s and 70s, who are so cool with how I present myself to the world with my Queerness. My great aunts are so welcoming to my wife and myself. And they're like, ‘thank you for coming back home’ because it was a time when I stayed away. When I came here, I stayed away for fear of just, you know, the homophobia that can exist in the [African] continent. And not everyone is. But I'm so glad that I got to go back. Because I wanted to experience the continent as a Queer African boi. And there's plenty [of us], and we do exist, and we do live in the continent. We're not out and proud about it, but we're there. And I mean, just this past summer when we were there, I ran into people and, you know, you make that little like eye contact and it's just like, ‘Hey, I see you. I see you.’ You know what I'm saying? So, yeah.

Nancy: So, one, you know, who am I sitting across from? Can you tell everyone your name, pronouns, where you're from and what brought you your family to The West?

Ngowo: Yeah. So my name is Ngowo Nessa and originally from Cameroon, born and raised til I was 18. Pronouns she/her/hers. What brought me here was my parents felt, I grew up in Cameroon until I was 18. Because my dad wanted us to have that African upbringing. But he also felt like he wanted us to experience another side of the world. So, I came here for college. And that's what brought me here. But what brought me to Minneapolis is work.

Nancy: And what do you do [in life]?

Ngowo: I am a senior web designer for Best Buy corporate. And I'm also on the Pride Leadership Team. So, outside of my daily responsibilities of being creative and coding, I'm also a part of a team that is really invested in creating a culture that's inclusive for the LGBTQ community on campus.

Nancy: And have you returned back home?

Ngowo: I'm going to give you a quick history. So, I knew I liked women in Cameroon, but I never— I did act on it, but I didn't tell anyone. And so when I came here, I reignited a relationship with an old friend of mine. And then it— because I didn't know what these feelings were I knew, ‘okay, I liked women,’ but it's not talked about I don't see other relationships like mine. So when I came here, I figured, ‘oh, okay, you're a lesbian, and you like women, and it's a taboo in Africa. Therefore, if you go back, you're going to get killed or you're going to get in trouble.’ So, I stayed away for like, 10 years. I did go back like after college in my late 20s. But I concealed my identity, you know, I'm masculine presenting, but I tone it down and I just— I was there for three weeks and spent time with my family. That time away was very difficult for me.

It was a period in my life where you can't deny where you're from. I felt like I was running away from the core essence of who I was as an African. I told myself— I’ve just felt a pull to go back home. And I said, ‘You know what, you just have to face it. Go back and see it for yourself. And if something happens, oh well.’ So, I went back, I came here, and then I went back five years later, and then I need to go back for like 10 years. And then — yes, that was a huge gap, a really huge gap.

And then when I finally went back, I had all these feelings inside of me —nervousness, excitement. I was already living into my, you know, masculine-presenting self. And so I didn't tone it down completely, but I just did t-shirts and pants. It was the most transformative journey I've been on because you hear the stories of, ‘Oh, don't go back. It's illegal. You're going to get killed. You know, folks are going to know that you look different. You'll stand out.’ None of that happened. None of it happened. And it just really affirmed who I was to the core, you know, I got to walk the streets of Cameroon as an African queer Boi, you know what I'm saying? I interacted with the population. I had folks who we would just strike up a conversation, I walk in somewhere and I haven't forgotten the language, it's just something that you don't forget.

Ngowo: So, I would just have conversations with random folks on the street. And honestly, I had to re-learn what it is to be African. Africans are just trying to exist. Folks aren't looking out to see who's Queer or who isn't. And I happen to know a lot of Queer Africans who live in the continent. And so, I think that the homophobia that exists feels, to me — speaking from my experience — feels fear-based. I mean, you're going to get I did get a few looks here and there. But that happens here. It happens anywhere, right? But I never felt unsafe at any point while I was there.

And so I actually have visions of going back and living longer than just a vacation. You know, even if it's like a dual kind of thing where I live there part time — like this time of the year was really cold. Run out and get some heat. I mean, like it's something that's in the works where I can go back, you know, in the winter months here and then come back. When you go back, it's like such an eye-opening experience. Like, I'm kind of mad at myself that I took the continent for granted. You know, when you're in college, you're like,’ Oh, it's just home. Yeah, who cares?’ But now that I'm much older, it's like, ‘oh my god, you could have capitalized on way more than you did’. And your dad is right: the quality of life there [is better]. And when you talk about the quality of life, and you talk about just walking around and being seen and not feeling like you're constantly on guard of this feeling of being watched, you know, it's so freeing, you know, like, the minute we land is just like this deep breath of ‘I can finally breathe. I'm home.’ I'm home, right? It's funny, cuz when we were just there this summer, we were out. We drove like four hours out to this beach resort area. And my brothers had the music playing really loud. And we're at this cabin, and it's like midnight, and Junauda, my sister and I, we're visiting and we're like, oh my god, it's funny how we're all kind of waiting for the cops to pull up and say, ‘Who are these [queer people]? You know, who are these?’ And none of that happened. But that was in our subconscious. You know what I'm saying? And it's not a good place to be in constantly. You know, it's not a good mind frame to be in and I find myself doing that. I find myself shifting, like shifting. You know what I'm saying? I don't want to have to shift. I just want to be my whole self. All the time. Every single minute of the day. That never happens there. It just never happens. Yeah, I have visions. I have dreams of also of doing the dual living thing.

Nancy: Do you know what it takes to be a dual citizen? Are you allowed to be a dual citizen to Cameroon?

Ngowo: I'm gonna get a Cameroonian ID so pretty much I'm not gonna present my American passport. But because I was born there, I just need an ID and my birth certificate and I'm fine. So yeah, I'm like, you know what? We're doing that, it's going down.

Nancy: You already talked about this. I’m really excited that you framed it in this way. So, I want to talk a little bit about borders and how it can change your definitions of home, identity and belonging. Can you describe a what would a world without borders looks like?

Ngowo: Hmm, that’s a good question. By borders, do you mean in terms of expressing all facets of who I am? Or are you talking about the borders of, say, immigration where you're not allowed to maybe transplant to this country because of who you are? Any of it, both?

Nancy: How we are bordered and contained but also stifled from moving

Ngowo: I think that's a colonial mastermind. Personally, because I just feel like if all Black people in the Diaspora were allowed to move back onto the continent, we would be one big, massive force to be reckoned with. Do you know what I'm saying? I feel like borders were put in place to keep us apart. Definitely to keep us apart. Because when I go to New Orleans, when I go to the South, even here [in the Midwest], like, we're the same people. We are the same people. My wife and I actually went on the slave trade path in Cameroon. Mind you, I didn't know about that [history about Cameroon]. Like, we never learned about the slave trade in Cameroon as a kid in our educational system. You know what I'm saying? So I personally feel like as Black people, we have to do our own research and really figure out ways of [traveling to Africa]. Even if you don't plan on moving back to the continent, at least go back to visit. Right? Because I feel like borders are limiting. It limits us and we're limit-less folks. You know what I'm saying? Even if you look at the way Africa was divided, there's no rhyme or reason. I'm really curious around what would happen if all the African countries just like the Europeans did become one union. The AU, right. Like, we will be so powerful. Nobody can touch us. No one. And that's where I lament about the borders that have been created. And how we have bought into that idea that ‘Oh, you're from Uganda. Therefore, we can't be cool.’ You know, we're not family. It's like no, my African-Americans folks here, that's my family. You're my family. We're all one Africa. Right? And I live for the day where we can see through that lie. I know that we were born to be great. And that's why there's a consistent policy to keep us down. Right? I mean, we don't see that. Call me crazy, but I have visions of being a president in some African country and just being like, ‘Get rid of these borders. Get rid of it. Now.’ Nigerians, you can move into Cameroon.

Nancy: Intercontinental traveling is impossible. Even crossing our own borders is impossible. And even talking about that, how that distorts our collective identity and history and knowledge of self. Separating, segregating ourselves has taken us all further away from our innate wisdom.

Ngowo: It really has. It really, really has. I feel like it's our duty as Africans to figure out a way to get out of that. Get out of whatever it is because it's our duty to go back to the continent and figure out a way to invest in the continent. And that's a problem. Some of these companies are not owned by Africans, and that's another problem. Ghanaians are going back. The British Ghanaians are going back. But I implore every Black person in the [African] Diaspora to [go back]. Like, your dollar will go way further in the continent than it would go here [in the West]. Your quality of life will improve. There’s community there. And don't be afraid of this narrative around, oh, ‘Africans don't like Black Americans and vice versa.’

Nancy: Colonial mastermind? I love that word.

Ngowo: Yes. That is just meant to keep us apart. Same with Queerness. Like, when my parents found out that I was queer, my dad was like, ‘Oh, it's just a phase’. Or he went ‘Oh, I know people who were.’ And it's just like, ‘oh, so you know [Queer] people, you’re 80 something and how long ago was that? You know what I'm saying? And so it's a dual thing where I think Africans are okay with you being Queer if you're not public about it. Which can be problematic, right? Because you're okay with me being this person, but I can't show PDA. Right? Or I can't bring my girlfriend around, or if I bring her around, then that's just my friend. So, I still struggle with that. But again, a lot of that [logic] is Christian-based. Because my dad would tell you that one of his late cousins used to be a pastor. And he said when the colonial masters came to Cameroon, they threw out a lot of the whatever they practiced, and were told to ‘respect this Bible.’ You're no longer practicing — they call it witchcraft — which, I don't know what to call it, so I'm not gonna give it a name. But I know that we weren't raised on it because my parents weren't raised Christian, you know?

Nancy: Oh, interesting. they never shared it with anybody?

Ngowo: They never shared it because he wouldn't share with me because his great uncle didn't grow up Christian. He grew up on something else. Even as a kid, long time ago, he didn't have a name for the religion because my uncle didn't wanna impart that wisdom onto my dad. But he said that my uncle was like a clairvoyant in the village. And his gift got stifled by the Bible. They were like ‘you're no longer going to practice this. Whatever you're doing, and we're now following the Bible.’ And so all of his stuff got thrown out. All of it. Yes. And that's how Christianity — on my dad's side — he said that's how Christianity came into his family.

Nancy: Wow. My parents said the first thing that happens in war is they destroy your museums, your literature, your art, all your religion, then have it replaced with theirs. Yes. I don't hear the personal narrative of what that looks like, and undoing your prior self and then, someone giving you a mask and saying this is your flesh.

Ngowo: I remember as a kid, I was like eight, [my family] had this tradition long time ago where when somebody dies, you'd have a pot to represent that our ancestors are always with us, even though they might be gone physically or spiritually, they're always with us. And I just remember this ceremony where there’s a wooden bowl with dirt representing all the ancestors that have passed away. It is really cool. But it's just sad that none of that was recorded. We do know that stuff was destroyed, we don't know what they practiced but we knew that Christianity was imposed upon them.

Nancy: There was a question here that will expand on what you just said. So borders like we were talking about before, they can change who you are the moment we cross them. So, by definition, our identities are inherently fluid. We're all inherently Queer. You know, most times we don't have the agency to define ourselves against power dynamics and outer struggles. And this false sense of security in the West, ‘you leave home to find safety elsewhere,’ even though you find even more subjugation and unsafe conditions where you leave. Which is kind of this myth around immigration and US foreign policy, how it’s influencing our experiences everywhere on the planet. So, I think now my question is can you talk a little bit about what essentially keeps us [Queer/Trans immigrants] away from home? And what prevents people from being safe in the world? Being with their families and living independent, full lives. What are these kind of elements at play you talk about in Christianity? I’m more interested about the complexity around neocolonialism and how it still festers the world today.

Ngowo: I like what you're saying, because the goal was that I would come here for higher education and then go back, right? But it didn't quite happen that way. And the reason is — I hate to say this — but I think that speaking, especially for Cameroon, the economy, some of our heads of states in the continent aren't really ‘there’. They're really puppets. And therefore, that translates into an infrastructure that is non-existent, is not beneficial, is not lucrative to the citizens of that country. The reason I didn't go back is because twofold; I'm Queer, and also finding a job where I felt would be sustainable was not there. But my Queerness is what really kept me away. So I think there's ways that we could move away from whatever political agenda that the West [has in store]. Like I said, we could create our own Africa. And for me, that's my focus right now. Like, I'm not thinking barriers. I'm not thinking, ‘Oh, I'm Queer, therefore, I can't exist.’ I'm thinking it needs to happen now. The future is Africa. If I don't step in, as an Africa or even anybody from the diaspora, if we don't step in to the continent and create what we want to see in the world, someone else is going to do it. And that someone else is not going to look like us. And they're already doing it. So, yeah, China is doing it. Belgium is doing it. The French are doing it. It's sad that we're so rich in so many natural resources. I just found out Cameroon was one of the largest timber exporting countries. Oh, you knew that? I couldn't believe that. I'm like, oh my god, and where does that money go? It doesn't get funneled back into the economy. It doesn't. So, I don't know if I answered your question.

Nancy: You did. You're talking about all these conditions and all the things that don't create the necessary environments for us to live fully.

Ngowo: Yeah, that's what I was saying. I was afraid of being my true self as a Queer immigrant in the continent. And for some reason, that’s changing. I think that a lot of it was built on fear. The minute I stepped into the continent, with full ownership of myself, and just being like, ‘here I am, in all my glory, coming in peace and in love.’ I got nothing but love from the people. So like, that used to be my excuse, ‘oh, I can never go back because I could never live into my fullness, I could never live into my queerness.’ And all of that is fear. And I've overcome. It was hard, mentally, more so than actually living [physically] in the continent. So yeah, I think I'm saying that to say just go see for yourself.

Nancy: Okay, we're gonna pivot at something a little less heavy. How do you define Queerness?

Ngowo: Um, for me, I think Queerness is just a way of being. It's about being politically conscious, for me, being respectful to myself and others and also creating space with people that may not look like you. Giving room for that, right?

Nancy: And how you define community and what do you think people need it?

Ngowo: Well, I think community is anyone that rides for me, for you, you know, folks that are able to celebrate you and have you in their circles but can also give you the hardcore constructive criticism on certain things. It's like family. Community for me is family and family is unconditional love. So, people that will love you no matter what, and they will be truly honest with you about anything and would also celebrate you no matter what. That's community and you need that.

Nancy: You do need it.

Ngowo: You do. I mean, like nobody is an island. I can be an introvert sometimes but you still need community. It's uplifting right to feel seen and heard and celebrated and loved.

Nancy: And why do you think immigrants, especially Queer[and Trans] immigrants now need community more than ever?

Ngowo: When I tell you folks are not happy that we're out here and we're loud and proud. They're not! The people that I think invested in this whole [idea of] there are no gay people in Africa, church-based folks and it's like, nah, that's not the Africa I know. And that's not an Africa I want to be a part of, you know what I'm saying? And so immigrants I think sometimes might feel like they're the only ones, or might feel like, there’s no one they can confide in, like there's nobody else that would understand these feelings that they're having. So, finding that immigrant community to share those feelings with is so important. And so I'm noticing a lot of Queer immigrant communities and little groups here sprouting out right now. And I think that we're on the verge of impacting the continent.

Nancy: Yeah. Two more questions for you. Next question is what gives you joy?

Ngowo: I think living my authentic self brings me joy. I wasn't always comfortable in my skin. And now I get to put my middle finger up and I'm like this is who I am. Take it or leave it. And that brings me a lot of joy and it's taken a lot of work for me to get here. But I'm glad I'm in this space right now. Family and community gives me love. My wife and my little daughter, they bring me joy. And my immediate family, we went through it. When I tell you we went through, we went through it! But they've come around. So, all of that brings me a lot of joy. But I truly will not feel joyful until all my Queer immigrants and Queer folks in the world can live into the same kind of, you know, their authentic selves, their realness, like I'm doing. It eats me up. It does. Yeah.

Nancy: And to wrap this up, final question. So this is about cultural shifts and structural change. So If you could address the most influential public figures and decision makers in the state, what would you say about elevating the standards for LGBTQIA+ immigrants of color in the [Twin] Cities?

Ngowo: Man, my goal is to provide housing at some point down the road for Queer immigrants in Minneapolis. Even if it means renting out a room in our house. It's not going to happen now but think that I'm working on something in the near future. And no one should have to experience homelessness just by way of who they are. Especially not in a state where we know that housing can be made available to folks. Right. But I would like to have a program where people could maybe offer up their homes for these Queer immigrant youth that may be homeless. Offer their homes for like three months at a time where they can live with you. How do we create spaces for Queer immigrant youth that could be experiencing homelessness? I don't play the lottery, but if I came up on some money, hey, I would want to buy up a whole block. And just be like, let's Queer it up! You know what I mean? I'm just saying that to say, yeah, I think that we need to take care of our youth. Our youth is the future.

Nancy: Anything else you want to add? I that's all I have.

Ngowo: Thank you for this interview. Yeah, I appreciate you. Really. I’m glad I was able to lend my voice some way, shape or form.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

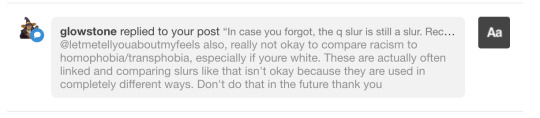

glowstone replied to your post “In case you forgot, the q slur is still a slur. Reclaim it as an...”

@letmetellyouaboutmyfeels the q slur is still a slur. Op is I'm comfortable being called such and many other people are as well. It's historically a slur and still is to this day and many people are still called it. Just because you live in a blue state where it's being reclaimed doesn't mean everyone does. Your experiences are not universal. Think about how people who live in the south feel being called that when the only times they have heard it b4 was being shouted at

not sure how to link two replies on the same post yet...

Well first of all, congratulations. You had to do some research on my blog to find out I currently live in a blue state, since I don’t mention that on my blog profile or about page. I appreciate it when people go through my entire blog finding out things about me so they can give me a “proper take down.” Here’s your gold star.

Here’s the thing, glowstone. You’re seventeen. And I well remember being seventeen, being full of fire, full of salt and vengeance, and ready to take on the world and thinking I knew everything. I hope you never lose that fire and that determination, because they’re wonderful things. And I hope you never stop trying to challenge people when you think that they’re mistaken or being hurtful.

But you are also seventeen. And you have a lot to learn.

I have literally gotten a degree studying queer literature. That is what my degree is in. That is what I spent an entire year doing research on for my final, culmination-of-my-entire-degree presentation. And as I pointed out, academia does not use slurs for the titles of their courses. I was not comparing racism to transphobia or homophobia, I was using it as an example of how academia does not use slurs as the titles of courses. A slur is a slur is a slur, no matter which demographic that slur might be aimed at, and so it’s a perfectly apt example.

I would consider actually doing research on queer history (yes, that is what it is called, you do not speak to LGBT Professors, you speak to “Professors of Queer Studies,” I don’t know how much more obvious I can be here). I think it would really open your eyes to how the word is being used.

Here are some links to book recs to help you start.

I would also be careful to put me or anyone in a box because “I live in a blue state.” I spent many years living in the Midwest, and in Florida. I have also traveled extensively, and while tumblr does tend to be very U.S.-centric, around the world queer is not considered the slur that you feel it is. In the Netherlands, for instance, it’s a perfectly accepted word by the community. People reclaim queer all over the country, all over the world, and the academic label of “queer studies” is universal.

As I said in my original post, if a person is not comfortable with being called queer, then that’s fine! All they have to do is say so. Just like I would tell someone I’m not comfortable being called pan because I feel that I’m bi. Pan doesn’t fit me as a label.

I would talk to queer people of color as well, people who are genderfluid, trans, etc, and not just people your age but older people too. I would specifically talk to activists, lawyers, academics, people who study and defend our community for a living. They are, in my experience, the ones calling themselves queer and they’re also (how fascinating) the ones people tell to “check themselves” and that “q is a slur and you can’t use it.”

It’s almost as if there are people in our community who are using “q is a slur” to silence the nonbinary, the noncis, the nonwhite, and so on. I’m not saying that you are doing that, not at all, dear glowstone, but I would do some research and ask around. Acephobia, biphobia, transphobia, and so on are alive and well in parts of our community and to police people in our community about using queer smacks strongly of that phobia, of gatekeeping, of “this is how you have to be or you’re not really a part of our community.” There are testimonies of people who say how they embraced queer and the queer community when the gay/lesbian community said they didn’t belong. Those testimonies are even here, on this very website, I’ve seen them.

Queer is a beautiful umbrella term. Some people are sitting here thinking, “I’m asexual genderfluid panromantic but wow that’s a lot to explain and I’m still not sure that fully encapsulates myself as an individual human” so they use ‘queer’ instead. I remember a friend talking about how they were treated like a boy by their parents despite being AFAB, and how their relationship with gender has always been rather interesting as a result, but they don’t identify as trans, so they use ‘queer’ instead. I have friends who drift between feeling like they’re demi, ace, and bi, so they use ‘queer’ because they still aren’t sure which box they fall into.

I may be white, and I make no effort to hide that or to hide my ignorance. But I’m not speaking for myself here. I am literally repeating what POC people in my life have told me. I do not quote them directly and am not tagging them, since they have asked not to be, but I am saying what they have said to me dozens of times. I personally feel that as a white person it’s my responsibility to speak up for POC when they are not comfortable or do not feel safe speaking up for themselves. I am repeating to you their words. Their statements. Their chosen identity. Please do not erase them by claiming I am speaking from my point of view, because I’m not.

There are literally articles out there (feel free to look them up I’m starting to feel lazy) that talk about the difference between queer identity and gay/lesbian identity. They talk about why some people are going to identify as queer as opposed to “picking a label.” Gay/lesbian/etc is, frankly, mainstream, and new. And those in our community who have always been on the outside--the people of color, the genderfluid, the trans, and so on--do not appreciate (and have said so repeatedly on tumblr and elsewhere) being policed about this word. Identifying as queer is a cultural movement that is being silenced by our current gay/lesbian framework and it’s not okay.

And frankly? Queer POC are not interested in us white people, especially young white people, telling them they can’t use that word because uwu it’s a slur when queer has been used as the title of a literal cultural movement. Which you would know if you studied... wait for it... Queer History.

Queer is the title of our entire cultural movement, our history, our literature. If you don’t want to use it for yourself, then you don’t have to!

But please, continue your education. Speak to our elders, read articles, contact your local university and ask to speak to the queer studies professors, go to a local queer activist chapter or queer activist lawyer. I personally recommend Dean Spade’s work as a good place to start, he’s a trans activist and professor who is (le gasp) from the south. But there’s a wealth of information out there for you. Please access it. Tumblr is a great space for our community but it is not university, it is not history, it is not the end all be all.

I hope you have a beautiful day, glowstone. Make yourself a nice hot chocolate and take a walk. And everyone else have a beautiful day too.

#glowstone#I'm a little snarky at the beginning but#I just can't help myself#*salty grandma mutterings about kids these days*#can you tell I put my Big Sister Hat on guys?#queer#queer history#lgbtq community#lgbt+ politics

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

VUD paladin headcanons!!!!

BTW this is based off of @voltronuniversaldefender ‘s reboot!!! CHECK THEM OUT THEYRE DOING GOD’S WORK

also i have read approx 2 headcanons and baRELY understand this AU so if there are similarities to anyone else or inconsistencies iT IS AN ACCIDENT AND IM SORRY

anyway this is just about the 4 confirmed paladins BET ill be doing more about Fa’rah/Takashi/Zahi/Ashanti once i know a bit more about their roles in the team!!

Alvaro Garcia Valladares

he has a twin. i don't make the rules, but he has a twin.

he has a big family. the biggest family. we’re talking, his mom has 8 siblings and his dad has 9 and there’s a 10 year age gap between him and his oldest sibling and he loves them all so much

natia is his best friend. i repeat, NATIA IS HIS BEST FRIEND!!!!

he’s also quite close with kiki. Natia and Kiki are the only two that he met before their great space adventure

he wasn't really sure of his sexuality at first. (i say this because i wasn't sure of my sexuality at first - im bi btw - and all the media i saw told me that any lgbt+ character was 100% sure of their sexuality form the day they were born, which made me doubt myself bc i didn't figure it out till recently, so i wanna see that in some media!! sometime!!) he probably figured it out halfway through having a crush on someone

the someone is akio, and he definitely tells Natia about it first

“natia... natia listen.... I have a crush on akio. freakin akio.... what do i do??? I’m bi, natia... I'm bi. what does this mean -”

“alvaro, I'm so proud of you, but this is a public bathroom and akio is right outside -”

GUARANTEE that the first time he saw Akio he just basically wanted to fight him but also flirt with him and had a slight moral crisis and ended up doing nothing

he is a goddamn sharpshooter, okay. he straight up becomes famous for it throughout the galaxy.

yet despite that he’s still insecure, and those insecurities prevent him from really getting together w akio until much later

he comes off as very suave and extroverted when you first meet him, but underneath it all, he’s actually really warm, personable and funny: not that anyone outside the team know that

aliens on social media, probably: god, the blue paladin is so cool... i bet he’s amazing and awesome and eloquent...

meanwhile, alvaro: do u guys think i could fit my whole hand in my mouth or nah?

enjoys memes, and shares this love with kiki

basically an all around great guy. because he often felt like a seventh wheel at the beginning of the formation of the team, he always tries to include everybody as best as possible, going way out of his way to ask after people, even if they forget to ask about him sometimes :’)

Natia Nanai

first off: what a gorgeous name. seriously. incredible kudos, my dude. anyway on to the head canons for this gorgeous girl

probably alvaro’s soulmate. already mentioned this, but it needs reiteration. they are best friends

had a large family too (not as big as alvaros tho) and probably major relate to him with that big family dealio

v close with kiki. they complete each other on a technological level.

natia is very, very creative. she and her sweet engineering know how are always instrumental in getting the Team out of tough situations

Akio: theres no way out of this we’re going to die -

Natia: bet?

she does say “bet” a lot. like, almost too much? but she's always right and valid when she says it

the villain: i’ve got you now!!!!

natia, under her breath: bet

the paladins, thinking: thank god, we’re saved

very soft but also badass as hell. she has a unique duality.

pulls a violet baudelaire: she puts that GORGEOUS hair up in a ponytail when doing work or whenever she has an idea

everyone on the team, regardless of sexuality, is low-key in love with her because she’s just so nice. no one can hate her. she's way too solid of a friend

speakinG of being a great friend: natia is 100% the secret keeper up in this bitch. everyone comes to her because they know she’s got the best advice around and will take their secrets to the grave

akio: idk man... alvaro is just rlly cute, u know?? but i can't tell him...

natia, thinking of alvaro literally whining to her about akio not even five minutes ago: christ

the mom friend. she always has all the things everyone needs on hand or in her lion, and she’s got it all going in terms of chore charts and family meals. she is the queen of figuring out times for team bonding and everyone loves her more for it

definitely started a board game night asap

she has a silent bravery about her that no one else can match. despite her trepidation, natia will always do what has to be done for the greater good.

she is guided by her heart and her morals, and is easily the kindest person on the team

bc of this kindness, she is often the diplomat when conflicts arise between people on the team

she is seen by the general public (aka the galaxy) as a strong, morally righteous woman. kind of like rosie the riveter-esque??? she’s the symbol of justice and fairness.

aliens: she's so... peacekeeping :0

natia, at kiki: throw me that wrench, or so help me god -

basically, a queen who always considers everyone and works really hard to create a family, even when they're all so far from home :’)

Kiki Evans

generally over it tbh

“always tired, but always inspired” - kiki, on being asked why there were dark circles under her eyes

kind of standoffish. she’s not really about being nice, she's about getting the job done, and that can rub people the wrong way, since she is always the first to offer up the cold, logical solution

but underneath that, she’s just a computer science nerd who is loyal to a fault

she really is loyal. its almost dangerous sometimes, because she would put the universe in danger to save her friends, which actually comes into conflict with her typical cold, logical approach.

she has 0-1 sibling. she's every bit the single child. she cannot relate to living in a big family setting, and at first its hard for her to deal with before she warms up to everyone else on the team

she's a genius, and thus found school to be tedious. in fact, she got fairly bad grades, as she wouldn't do the work that she saw as pointless and boring

she is a meme connoisseur, and loves to quote vines, often assisted by alvaro

kiki, as they approach a giant black hole: HZZK

alvaro, catching on immediately: is... is that real???

she is a conspiracy theorist, for sure. the government is watching us all, trying to make sure we don't learn too much.... she’s sure of it, and akio is too

tbh, the first proper conversation she had with akio was about cryptids and how the government had hidden them from the public

she was friends w natia and alvaro from before, but it is akio she becomes closest with the fastest. in some ways, she feels more distant from natia/alvaro bc of how close they are with each other and bc all of them have known each other for so long while akio is someone she got to know recently: he has no preconceptions about who she used to be, and she has none about him

plus, she and akio relate on many levels: both trans, both gay, both autistic, both theorists, and both loyal to a fault. she finds a real blood brother in akio :D

very openly gay. very. she's a space lesbian, and theres no denying it

kiki, meeting some random space girl: oh

kiki, moments later to akio: god I'm gay

akio, downing a glass of water but acting like its vodka or smthg: god, same

the public sees her as the cold and calculating techie, the brains of the operation

natia is her partner in crime. they finish each others sentences. they've got a tech connection going, babey

kiki: if we just cross-reference the zaiforge tunnel with the -

natia, nodding: particle consummator, of course we’ll get the perfect -

them, together: amount of energy!!!

everyone else: sorry wot

basically, she's a tech goddess with a splash of genius. she's uneasy and a bit awkward, but thats just bc she’s never been in a situation like this before. after literally 1 second with her, she opens up and is such a loyal friend. :’)

Akio Himura

wow this boy is gay and he knows it

he loves his parents (zahi, takashi, and ashanti) but god he will never admit it. not ever

alvaro, after listing his parents, 20 aunts and 100 cousins: and i love them all so much, with all my heart. what about ur family akio?

akio, not wanting to show weakness: they're nerds.

alvaro: um okay cool good talk haha :)

akio, internally: but i love them nd would die for them tbh... but i can't show weakness

he's so guarded after his biological parents left/died/disappeared. poor boy

definitely a single child, and definitely adopted

his parents love him SO MUCH. so much.

akio: why do i have three parents, dad?

takashi, almost crying: its simple. u deserve so much love, that it couldn't be contained in just two people. we needed three. its how its gotta be, my beautiful, sweet summer child

a yeehaw kind of guy. he grew up in the midwest riding horses before his biological parents died and theres a piece of him that will always be a southern boy

the kind of kid in school that pretends he’s a delinquent, but actually just has the aesthetic of a delinquent, and is truly soft

akio: hell yeah I'm a rebel. i logged onto disney.com without my parents permission

kiki, choked up: so brave

mothman is his love. his passion. all cryptids, for that matter. kiki is more of an all around conspiracy theorist: akio is in it for the cryptids

he’s a bit awkward, and doesn’t totally understand all social cues/jokes. because of this, he stays away from memes, and is very guarded when meeting new people, especially after experiences with light bullying for not only his social ineptitude, but his upbringing.

considering that, his first meeting with alvaro was supremely awkward, and akio accidentally fought with him multiple times before they established a solid friendship

akio, having a gay panic: you are the light of my life

alvaro: sorry what??

akio, panicking more: I said, you wanna fiGHT WITH A KNIFE???

he pined after alvaro from basically day one, but had the foresight to actually know that he was pining, unlike alvaro who just floundered

of course he would never say anything

he is a stabby boi. he is unrivaled in swordplay, and enjoys routine. his natural affinity for picking up new skills plus his unrivaled work ethic basically DESTROYED everyone else when it came to swords

he’s loyal af and is always the first one to take action. akio is a “do something. do anything, but do it fast before we lose a chance to do something” kind of guy

the general public sees him as the fiery one: he’s the one with the fanciest footwork in a fight, and he’s very good with battle tactics. he can come thru with that strategy at the perfect times

he's a low-key emo. for sure. he loves MCR, but strangely dislikes other similar artists like p!atd and fob.

kiki: but...brendon urie, akio....

akio, sipping tea: as a gay, i can appreciate the aesthetic. but no one can compete with MCR

kiki, exasperated: its not a competition -

basically, a slightly guarded boy with a real talent for defending the universe and his friends, but also an emo cowboy mess who is in love with alvaro and loves everyone :’)

WELL THAT ENDED UP LONGER THAN I EXPECTED. I HOPE U ENJOY AAAA

ALSO FOLLOW @voltronuniversaldefender !!!! its amazing, guys, really check it out :D

#vud#voltron universal defender#i love them asadjkdflkKL#vud headcanons#I HOPE YALL LIKE THIS#alvaro valladeres#natia nanai#kiki evans#akio himura

222 notes

·

View notes

Text

On Tonight's Survivor:

I am a transgender woman, only out to a couple family members and all of you online. I’m pre-transition but about to start, which is to say that I have not yet begun to know the struggles I will likely go through in life to be myself.

On tonight’s episode of Survivor: Game Changers (Season 34!), a closeted trans-man named Zeke was outed, both publicly and on the show, by a fellow contestant at Tribal Council. This contestant, Jeff Varner, was likely to be eliminated from the game and announced to the tribe that Zeke was trans, ostensibly as a ploy to make people distrust Zeke.

The initial response by both Zeke’s fellow tribemates and the host Jeff Probst was stunned silence followed by intense anger and sadness directed at Varner. All five tribemates lambasted Varner as Zeke sat in shock.

My reaction was the same as Zeke’s. I couldn’t believe that someone I had watched on my local news for years, someone who I had loved on two previous seasons, someone who was an openly gay man, could do something so mindlessly cruel to another person. I expect those type of comments from ignorant assholes and spineless politicians, but certainly not from someone like Jeff Varner. I also realize that Varner surely regretted saying it once the words actually came out, but that doesn’t undo his actions. I know I have said stupid things in my life, but I can’t say I’ve ever stooped that low as an adult.

Despite all of this, somehow the overall feeling I have tonight is joy. Something so tragic could’ve left me feeling shaken and sad, but the way Zeke turned the moment into a beautiful one amazes me the more I think about it.

After regaining his composure at Tribal Council, Zeke found the strength to say this:

“Being trans and transitioning, it’s a long process, it’s a very difficult process, and there are people who know. But then I sort of got to the point where I stopped telling people, because when people know that about you, that’s sort of who you are. There are questions people ask, people who want to know about your life, they want to know about this and that, and it sort of overwhelms everything else that they know about you. You’re no longer Zeke, you’re ‘the trans person’.

I think I’ve been fortunate to play Survivor as long as I’ve been playing it and not have that label, and one of the reasons I didn’t want to lead with that is that I didn’t want to be 'the Trans Survivor Player’, I wanted to be Zeke, the Survivor player. And I feel like I am! So I’m okay. I knew someone might pick up on it or it might be revealed, so I am prepared to talk about it, to have it be a part of my Survivor experience. It’s kind of crappy the way it’s happened, but, you know.

'Metamorphosis’ is the word of the episode, and I feel like I’ve seen such a metamorphosis of myself over the past 52 days I’ve played Survivor. I don’t know if the scared kid who hit the mat in the marooning of (Season) 33 would be as calm as I am right now, but I’ve started two fires with just bamboo, I’ve won challenges, I’ve been part of blindsides, I’ve done all kinds of crazy stuff and I am a changed, stronger, better man today than I was then. So you know what Varner, it was really not cool, but you know, I’m fine.

You know Jeff, I’m certainly not anyone who should be a role model for anybody else, but maybe there’s someone who’s a Survivor fan, and me being out on the show helps him, or helps her, or helps someone else, and so maybe this will lead to a greater good.”

As incredible as it was to hear these words delivered so eloquently by Zeke, and on national television no less, it was the words from another tribemate that amazed me the most.

Sarah, a conservative cop on the tribe, was the most reserved person at Tribal Council while the chaos caused by Varner’s words unfolded behind her, sitting deep in contemplation. What she finally said blew me away.

“I’m just thankful that I got to know Zeke for who Zeke is. I’ve been with him for the last eighteen days, and he’s, like, super kick-ass. I’m from the Midwest and I come from a very conservative background, so it’s not very diverse when it comes to a lot of gay and lesbian and transgender things like that. So I’m not as exposed to it as much as most of these people are, and the fact that I can love this guy so much, and it doesn’t change anything for me, it makes me realize that I’ve grown huge as a person.

Of course we want to come away with the million dollars, but the metamorphosis that I’ve even made as a person that I didn’t realize until this minute is invaluable. I’m sorry it came out that way, but I’m glad it did. I’m so glad I got to know you for Zeke, and not for what you were afraid of us knowing you as, and I’ll never look at you that way.”

Seeing someone who has obviously never had to confront feelings like this so directly, and quickly realizing that she still loved Zeke for Zeke, with his being transgender not changing anything, gives me hope. It makes me realize that most people, when given the opportunity, will treat you with kindness and compassion. And maybe what they need to explore these feelings is to have a personal moment of realization like Sarah did. Zeke, and Varner I suppose, gave millions of people the opportunity that Sarah had tonight.

Some people will hold onto their prejudices regardless and demonize Zeke to fit their worldview. Perhaps they’ll never become accepting of LGBTQ people, or maybe it will take someone directly in their life coming out to change. But I know that some people watching tonight, who rooted for Zeke every week not knowing he was trans, are spending tonight reconsidering their values. That’s progress. And what a beautiful thing it is.

On a personal level, the handling of this moment by both Jeff Probst and the producers/editors involved in it make me proud to be a “superfan” of this show. It could have gone haywire and turned into a purely rotten situation, but instead became a truly important focus on what it means to be true to yourself in this world. I have always wanted to be on this show, roughing it in the rain with people scheming against me, trying miserably to untie knots underwater because I want to be treated to Adam Sandler’s latest film, feeling the euphoria of making it onto the jury, and even the slim possibility of winning a million dollars. I had never truly thought I could make it onto the show, and coming out as transgender initially made me think that I had even less of a chance.

Zeke changed that for me.

I want to make an audition tape now. I feel like if he can do it, and do it so well, then why the hell cant I? I know millions of people have had that same thought, but I’ve never once felt this sense of drive in my young life. I owe that to Survivor first and foremost, but also to Zeke and the, dare I say it, heroism he showed on tonight’s episode.

Maybe you’ll see me on a future season of Survivor, maybe not. But I know that I got something life-changing out of the show tonight, and I’m sure I’m not alone. If eight year old me, sitting there enthralled by the very first season of Survivor, could know just how big an effect this show would have on her, she wouldn’t believe it. Mostly because she was eight and didn’t know anything about anything, but still.

Tonight, send your love to Zeke Smith for bravely confronting what could have been ruinous and transforming it into something worth celebrating. Send your love to Sarah Lacina, Ozzy Lusth, Tai Trang, Andrea Boehlke, and Debbie Wanner for speaking up on Zeke’s behalf, being true allies to trans people everywhere, and showing that there will always be people in this world who will have your back when the bullies try to knock you down. And send your love to Jeff Varner, who made a terrible mistake, and has by all accounts suffered ten times over for it. Allow him to learn from this and become a better person as a result. He will be most capable of doing this with your love and support. Do not excuse his actions and similar actions of others worldwide, but fight to turn the negatives into positives whenever possible.

We can do this.

Love always,

Claire.

#survivor#survivor game changers#survivor season 34#survivor s34#transgender#trans#LGBT#lgbtq#zeke#Varner#jeff probst#textpost#mine#hidoggy

246 notes

·

View notes

Text

Happily Single: Why Marriage Wasn’t a Good Fit for Me

“I’m not sad about any of my life. It’s so unconventional. It doesn’t look anything like I thought it would.” ~Edie Falco

I knew what was coming. My co-worker Rose was midway through her second chocolate martini and feeling loose enough at our after-work get-together to stop talking about her marriage and instead, start talking about my non-marriage.

“I don’t get it. Why haven’t you ever been married?” she asked, in a disbelieving tone.

I sighed. “You know, this is the third time you’ve asked me that. Remember? We had that whole conversation about it at the office Christmas party last year.”

Looking deeply perplexed, she sipped at her drink, not ready to drop the subject. “I just mean…you’re so attractive and you have such a great personality. How is it that you’ve never been married?”

That’s what she said. What she meant was: What’s wrong with you? Are you some kind of a freak? Couldn’t you get a man? Are you man hater? Or a lesbian? (Not that there would be anything wrong with that—and actually, it’s no longer a valid excuse to be single, now that same-sex marriage is legal).

It’s possible that I was imagining more subtext than Rose intended, and to be fair, she was not the first person who’d put me on the spot about my single status.

On a regular basis, people I meet express astonishment at my never having tied the knot, taken the plunge, walked down the aisle to what is widely assumed to be a happily ever after existence. I am expected to explain myself—to defend my life choices—often to people I’ve just met.

Well-mannered folk who would almost never consider prying into the private lives of a brand new acquaintance have no reluctance in doing so when they find out that she’s an old maid. (Yeah, I’m owning that term.)

I’ve experienced this with bosses, co-workers, a man at a class reunion whom I hadn’t seen in thirty years, dental hygienists, a stranger sitting next to me on an airplane, manicurists, and various random strangers at parties.

A polite conversation can suddenly turn awkward if I let slip that I am an old maid. (I did recently have a different experience with a hair stylist who is divorced and struggling to raise two kids with no financial help from her ex. When she found out that I’d never been married, she said, “How’d you get so lucky?” But that reaction is the exception.)

People want an explanation. A story. Something that makes you make sense to them. After all, isn’t everybody supposed to grow up and get married?

For years, I’d stammer out some cliché intended to put people at ease, like, “I never met the right guy,” or “I moved around a lot for my career.” While that may have satisfied their curiosity, it invariably made me feel worse. Why did I have to apologize for who I was? Assure others that I was normal (in most respects)?

As I grew older, people became even more inquisitive and judgmental. After all, the bloom was off the rose. Even if I came to my senses and made a determined effort to find a spouse, I had aged out of my peak mate-attracting years.

Eventually the questions took a toll on my self-esteem, causing me to question myself and my choices.

Had I made a horrible mistake by not prioritizing getting married? Did everyone else know something I didn’t know? Would I someday deeply regret not having “Mrs.” in front of my name?

Seeing one friend after another get married multiplied my doubts and made me wonder: “Is there something wrong with me?”

I’d wake up abruptly in the middle of the night, overwhelmed by a sick feeling of dread, thinking: “I FORGOT TO GET MARRIED!”

When I was young, I did assume that someday I’d get hitched and have a family. I didn’t have a clear picture of what that would look like, although I was definite about not wanting to do a lot of housework, like my mother did. (I still don’t; I pay someone to clean my house). I had no interest in cooking—another of her daily chores—and as for motherhood urges, I preferred Barbies to baby dolls.

Marriage is a wonderful institution, for many people. I have lots of friends who enjoy sharing their lives with loving spouses—and I’m happy for them—but marriage is not a good fit for everyone. Those who do not, for whatever reason, get married should not be subjected to “single shaming.”

For my part, it took the hindsight reached after decades as a singleton to realize that I’d been deeply ambivalent about matrimony all along. I saw marriage as a choice that would affect all other choices, a partnership with many benefits but one that would tie me down and limit—at least to some extent—my ability to follow my own dreams.

What I really wanted was adventure. My parents’ traditional marriage worked for them, but it didn’t appeal to me, a child of the sixties and seventies who saw new doors swinging open for women, offering us opportunities that had not been available to my mother when she was coming of age.

I wanted an interesting career—preferably something outside of the mainstream—and I knew that marriage would restrict my options. When I was a kid, I wanted to be a spy. That didn’t happen, which is just as well for America, since I can’t keep a secret. Perhaps predictably, I went in a direction that allowed a lot of communication and became a radio personality.

Had I been married, I would not have been able to advance my career by moving all around the country, bringing comedy and commentary to listeners in various states. I got to broadcast from the back of an elephant in a circus, a hot air balloon high in the sky, and a pace car making the rounds at a racetrack. I introduced bands like REO Speedwagon and The Judds at concert venues and made guest appearances on local TV shows.

Early in my career, when I’d worked my way up from teeny tiny markets to a merely small market, I got a job offer from a radio station in San Francisco. San Francisco! In one move, I could more than double my salary, which at that time kept me just above the poverty level.

Of greater importance to me was the opportunity to work with major market personalities and reach many more listeners than I ever could in Champaign, Illinois. Additionally, I could go from the Midwest to an exciting city in California.

I thought about it for a hot second, and then said, “Yes!”

I didn’t have to ask a husband if he wanted to move. If he would be able to transfer or find a new job in the Bay Area. If he would be willing to leave behind friends and family, forego the recreational softball team for which he’d played third base for so many summers, abandon the garden he’d lovingly hewed out of the wilds of the backyard.

I was able to make a major decision based solely on what I wanted to do, and it was exhilarating. With the exception of the job interview I’d flown in for, I’d never even been to San Francisco, but I was thrilled as I packed up and hit the road for a new position in an unfamiliar city.

Ironically, that job turned sour pretty quickly, for reasons that had nothing to do with its location. After a year, I left for greener pastures (okay, Chicago) just as easily as I’d headed for San Francisco. And that wasn’t my last move, by the way.

Imagine if I’d uprooted a husband, convinced him to go to the Bay Area to start a whole new life there, and then turned around in a year’s time and told him that I’d changed my mind. If he had objected to moving yet again—which would have been completely reasonable on his part – I might have been stuck indefinitely in a job I hated. I would likely have brought that bitterness home from work every day, where it would have affected my marriage.

Being single enabled me to make the career decision I needed to make at that time. Not all of my decisions have been brilliant; I haven’t always had a lot of money, but what I do have is mine to do with as I wish, as is my time. Whatever actions I take or choices I make are done without having to consult with, negotiate with or ask permission from anybody, and I enjoy the hell out of that.

I go where I want to go on vacations, sleep in late when I feel like it and commit to time-consuming projects that appeal to me. I act in plays and sing in a band. I’ve run half marathons, traveled through Europe, and worked as a personal assistant to a movie star. My annual Halloween costume party is legendary.

I’m constantly learning new things; my current efforts include speaking Italian, playing the bass guitar, and sewing.

The point is: I spend my free time doing what I love to do, without having to accommodate someone else’s wants, needs, or schedule.

Married women, of course, get a lot done as well, but their accomplishments are not shadowed by the big “but,” as in, “She climbed Mt. Everest and discovered a new solar system, but she never found the right guy. How sad.” An old maid could find a cure for cancer, figure out a way to reverse climate change in a week, and invent high heels that felt like cushy slippers but at her funeral, people would still whisper, “She never married,” as if that canceled everything else out.

What’s interesting about this is that as a society, our ideas about marriage and family have undergone profound changes in recent decades.

Biracial couples who might have raised eyebrows some time ago are commonplace now and are regularly featured in TV commercials. Same-sex marriages are being accepted—or at least tolerated—to a greater extent now. It may have taken Aunt Vivian awhile to accept the fact that her niece Carolyn will be exchanging vows with someone named Diane, but Viv wouldn’t think of missing the wedding.

But what about people who don’t get married to anyone? Now that’s radical.

Why would someone want to go through life uncoupled? After all, being single past a certain age means being lonely and miserable, right? In a society that relentlessly promotes coupledom as the normal and only desirable way for adults to live, that negative perception about single women (in particular) persists.

That negativity eventually got to me. I became convinced that I was the last unmarried woman over forty (ok, over fifty) on the planet, and that I had made a big mistake in taking the road less traveled. I couldn’t reconcile the happy, busy, friend-filled life I had with the perceptions of other people. That they were people who didn’t know me well didn’t seem to matter.

My friends loved and accepted me for who and how I am. Why wasn’t that enough?

Like everyone who feels alienated, I found myself looking for my tribe.

I discovered that there are plenty of “old maids” out there who are living their lives fully and enthusiastically, despite the annoying questions and side eye glances that come their way. Many are still open to the idea of marriage but they are not waiting for it, not keeping their dreams on hold until the perfect partner comes along. They are complete, just as they are.

Many of them (okay, many of us) thoroughly enjoy the freedom and autonomy that go along with being single.

It’s a tribe that’s growing in size. The percentage of single people in the U.S. is greater than ever before, with single men and women making up 47.6 percent of households in 2016, according to U.S. census data. More singletons were women: 53.2 percent compared with 46.8 percent who were men.

It took me awhile, but I reached the point where I no longer summon up clichés to explain myself to people who can’t think beyond the conventional. I’ve realized that it’s not my responsibility to reassure them that I’m normal. I am normal. I’m just not married.

About Maureen Paraventi

Maureen Paraventi is a Detroit-based writer of fiction, nonfiction, stage plays and songs. Her book, The New Old Maid: Satisfied Single Women, is available from Amazon and Chatter House Press. When she’s not writing, Maureen sings with McLaughlin’s Alley, a pop/rock/Irish band that plays in venues all over southeast Michigan. Find out more about her at maureenparaventi.com.

Web | More Posts

Get in the conversation! Click here to leave a comment on the site.

The post Happily Single: Why Marriage Wasn’t a Good Fit for Me appeared first on Tiny Buddha.

from Tiny Buddha https://tinybuddha.com/blog/happily-single-why-marriage-wasnt-a-good-fit-for-me/

0 notes

Link

Having had a cup of hot tea and written a bit — my mind sweetens on life once again.

The mercurial aspect of me! Why is it so extreme? No drug, not even aspirin, and yet my mood is as different from what it was 45 minutes ago as the Himalayas are from the Sahara. Why? What does it mean? Am I so utterly a creature of my juices? Entirely? It would seem so.

— Lorraine Hansberry, from her journal entry titled “Puzzle” March 15, 1964

¤

A RAISIN IN THE SUN playwright Lorraine Hansberry is one of the most noted names in US theater history. And yet it is only now, more than five decades since her death in 1965 at age 34, that we are beginning to uncover her influence beyond the stage. As a journalist, Hansberry was a social justice warrior whose work brought her under FBI surveillance. She was an activist who took on the Kennedys (both John and Robert); associated with the likes of Paul Robeson, Malcolm X, James Baldwin, and Langston Hughes; and in her personal life, challenged conventional mores of race, gender, and sexual politics: she married a man, but identified as a lesbian.

Born on the South Side of Chicago, the daughter of Southern migrants, Hansberry grew up in the gap between the black bourgeoisie and abject poverty. Her move from the Midwest to the Great White Way forms scholar Imani Perry’s Looking for Lorraine: The Radiant and Radical Life of Lorraine Hansberry, an American odyssey and intimate portrait of an artist — young, restless, gifted, and black — at a crossroads between craft and justice; between life and dreams; between self-care and sacrifice.

“One of the great lessons from that period is what it really meant to invest one’s self in the struggle,” said Perry on the phone from her home in Philadelphia. “You think about how young she was when her passport was taken; she was under surveillance — this was her early 20s. Same with [W. E. B.] Du Bois, same with Paul Robeson. Now everybody loves Baldwin, but they were talking about him being too political after the deaths in ’68 when he was like: ‘I think we need to give up on this place.’ Then he wasn’t right anymore; he wasn’t smart anymore. You can say the same for King.

“But the point is, they were willing to give up everything for their investments and struggles for justice. We have to get to a way of celebrating not just their achievement, but their courage and their sacrifice because it really poses the question for us: What will we stand for? What are we willing to risk?”

¤

JANICE RHOSHALLE LITTLEJOHN: In the book’s introduction, you wrote that Hansberry’s “is a story that remains in the gap,” and you go on to discuss the various people who are going into those gaps to reveal who she was and her impact on culture. What is it about this particular time that has prompted this kind of interest in Lorraine Hansberry, her story and what it means to us now?

IMANI PERRY: A piece of it is definitely the renewed interest in black women’s history, in particular, and attention to the submerged histories of black women. Combined with the fact that she’s this figure who sits at the crossroads of so much: she identifies as a lesbian, she’s a woman who comes of age in Chicago in the midst of this period of intense discrimination and upheaval and migration. There’s all of these forces that are part of her identity and her story that are in some ways very similar to the kinds of questions we’re talking about now, whether it’s about the inequality — just this morning on Twitter there was this robust conversation about violence and racial inequality and policing in Chicago, all of which were central to her life — or this kind public conversation about intersectionality, and for her she’s trying to figure out feminism and sexuality, race, class.

All of these issues are at the forefront of our minds right now. On the one hand, she speaks to the moment, and on the other, she’s this incredibly well-known figure, the most widely read — arguably — black playwright in the history of the United States, and yet there isn’t that much known about her life. There’s a natural curiosity that hasn’t been fully satisfied.

Tracy [Heather Strain] did an amazing job with the documentary [Sighted Eyes/Feeling Heart] giving us a picture of her life, and there’s just so much work to be done.

What kind of community has developed from those of you who have been exploring Lorraine Hansberry’s life? You mentioned Tracy Heather Strain along with others in the book. How often do you connect with each other to share stories or findings, or simply borrow from one another to fuel the work you’re each doing?

Working on her and being in a community with Tracy, [biographer] Margaret Wilkerson Sexton and [scholar] Soyica Colbert has been this extraordinarily beautiful experience. So often there’s this sense of competitiveness and selfishness and guardedness with respect to work on a figure, and my experience thus far is that we all have this sense of this being a collective endeavor in trying to give Lorraine her due. We have conversations. We did a panel together at the Schomburg [Center for Research in Black Culture in Harlem] in the spring that was really wonderful. We all bring different emphases to our work, so there’s room for many books about her. I’m also excited about the different sides of her that will emerge from the different bodies of work. Given how intensely competitive academia can be this is such a beautiful, refreshing experience to work with people where everybody is really motivated by the work and not self-aggrandizement or selfishness.

In the book, you do draw some of your personal parallels that you feel have connected you with Lorraine’s story. Can you talk a bit about those similarities? And, to piggyback on that, as you were “looking for Lorraine,” were you able to gain any insights on yourself?