#if people spent this same amount of energy on their local elections and school board races

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

I think the most important part of the Dr*p*ut statement is a reminder that they can’t do much and calling your reps/donating money does WAY MORE to help the actual people who are being killed

#like really people there’s far bigger fish to fry#fandom wank#the disk horse#if people spent this same amount of energy on their local elections and school board races#we’d be a much better country

0 notes

Text

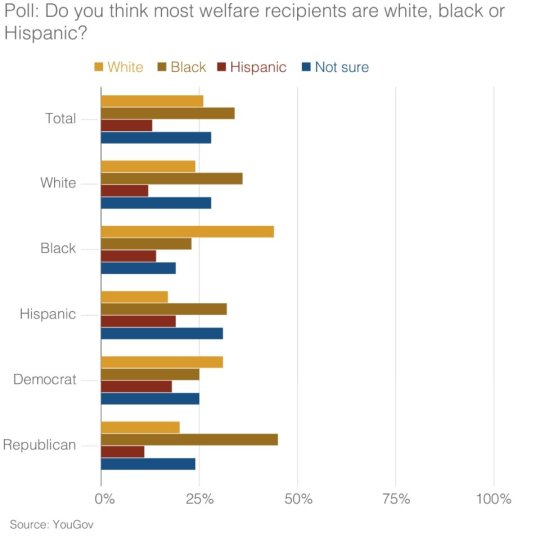

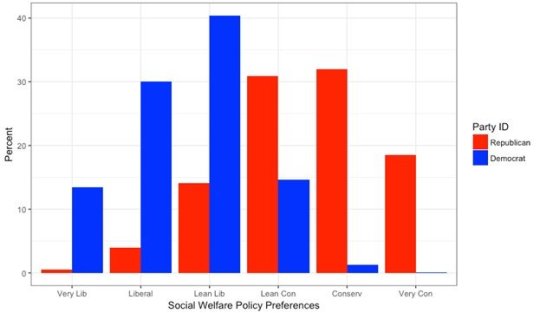

What Percentage Of Republicans Are On Welfare

New Post has been published on https://www.patriotsnet.com/what-percentage-of-republicans-are-on-welfare/

What Percentage Of Republicans Are On Welfare

Democrats Return The Favor: Republicans Uninformed Or Self

Republican States Are Mostly on Welfare

The 429 Democratic voters in our sample returned the favor and raised many of the same themes. Democrats inferred that Republicans must be VERY ill-informed, or that Fox news told me to vote for Republicans.;;Or that Republicans are uneducated and misguided people guided by what the media is feeding them.

Many also attributed votes to individual self-interest whereas GOP voters feel Democrats want free stuff, many Democrats believe Republicans think that I got mine and dont want the libs to take it away, or that some day I will be rich and then I can get the benefits that rich people get now.

Many used the question to express their anger and outrage at the other side.;;Rather than really try to take the position of their opponents, they said things like, I like a dictatorial system of Government, Im a racist, I hate non-whites.;

Average Spending Of Welfare Recipients

Compared to the average American household, welfare recipients spend far less money on all food consumption, including dining out, in a year. As families with welfare assistance spend half as much on average in one year than families without it do, there are some large differences in budgeting. Families receiving welfare assistance spent half the amount of families not receiving welfare assistance in 2018.

The Gop Push To Cut Unemployment Benefits Is The Welfare Argument All Over Again

The White House is on the defensive over accusations from Republicans that expanded federal unemployment benefits, which were extended through Sept. 6 as part of Bidens $1.9 trillion coronavirus relief package, are too generous. The GOP argument is that people receiving the $300 weekly benefit have little incentive to return to work. The criticism from Republicans has gotten louder in the wake of a disappointing jobs report.

Its an argument that echoes similar claims conservatives have been making about government assistance programs for decades that people are taking advantage of the system in ways that allow them to collect checks while sitting back and relaxing.

As Washington pays workers a bonus to stay unemployed, virtually everyone discussed very real concerns about their difficulties in finding workers, Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell said Monday. Almost every employer I spoke with specifically mentioned the extra-generous jobless benefits as a key force holding back our recovery.

But Democrats counter that millions of Americans need that money to get by. More than 20 million jobs were lost in the early months of the pandemic; 10 million American workers are currently unemployed, the Labor Department says.

Democrats say the sudden demand for more workers from businesses is outpacing the number of workers that can get back into those jobs, especially since many schools arent fully open, and many workers cant afford child care.

You May Like: When Did The Democratic And Republican Parties Switch Platforms

The Politics And Demographics Of Food Stamp Recipients

Democrats are about twice as likely as Republicans to have received food stamps at some point in their livesa participation gap that echoes the deep partisan divide in the U.S. House of Representatives, which on Thursday produced a farm bill that did not include funding for the food stamp program.

Overall, a Pew Research Center survey conducted late last year found that about one-in-five Americans has participated in the food stamp program, formally known as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program. About a quarter lives in a household with a current or former food stamp recipient.

Of these, about one-in-five of Democrats say they had received food stamps compared with 10% of Republicans. About 17% of political independents say they have received food stamps.

The share of food stamp beneficiaries swells even further when respondents are asked if someone else living in their household had ever received food stamps. According to the survey, about three in ten Democrats and about half as many Republicans say they or someone in their household has benefitted from the food stamp program.

But when the political lens shifts from partisanship to ideology, the participation gap vanishes. Self-described political conservatives were no more likely than liberals or moderates to have received food stamps , according to the survey.

Among whites, the gender-race gap is smaller. Still, white women are about twice as likely as white men to receive food stamp assistance .

How Democrats And Republicans Differ On Matters Of Wealth And Equality

A protester wears a T-shirt in support of Bernie Sanders, an independent from Vermont who is part of … a group of Democrats looking to beat Trump in 2020. Photographer: John Taggart/Bloomberg

If youre a rich Democrat, you wake up each day with self-loathing, wondering how you can make the world more egalitarian. Please tax me more, you say to your elected officials. Until then, the next thing you do is call your financial advisor to inquire about tax shelters.

If youre a poor Republican, however, you have more in common with the Democratic Party than the traditional Wall Street, big business base of the Republican Party, according to a survey by the Voter Study Group, a two-year-old consortium made up of academics and think tank scholars from across the political spectrum. That means the mostly conservative American Enterprise Institute and Cato were also on board with professors from Stanford and Georgetown universities when conducting this study, released this month.

The fact that lower-income Republicans, largely known as the basket of deplorables, support more social spending and taxing the rich was a key takeaway from this years report, says Lee Drutman, senior fellow on the political reform program at New America, a Washington D.C.-based think tank.

Across party lines, only 37% of respondents said they supported government getting active in reducing differences in income, close to the 39% who opposed it outright. Some 24% had no opinion on the subject.

Also Check: Democrats News

Bases Of Republicans Antidemocratic Attitudes

shows how Republicans antidemocratic responses in the January 2020 survey were related to education, political interest, and locale. These relationships provide only modest support for the hypothesis that allegiance to democratic values is a product of political activity, involvement and articulateness, as McClosky had it . Although people with postgraduate education were clearly less likely than those with less education to endorse violations of democratic norms, the overall relationship between education and antidemocratic sentiments is rather weak. Similarly, people in big cities were only about 5% less likely than those in rural areas to endorse norm violations, while people who said they followed politics most of the time were about 7% more likely to do so than those who said they followed politics hardly at all. Given the distributions of these social characteristics in the Republican sample, the most typical antidemocrats were not men and women whose lives are circumscribed by apathy, ignorance, provincialism and social or physical distance from the centers of intellectual activity , but suburbanites with some college education and a healthy interest in politics.

Social bases of Republicans antidemocratic attitudes.

Key indicators of latent dimensions

Political bases of Republicans antidemocratic attitudes

Translation of ethnic antagonism into antidemocratic attitudes in Republican subgroups

Welfare Accounts For 10% Of The Federal Budget

Many Republicans claim that social services expenditures are crippling the federal budget, but these programs accounted for just 10% of federal spending in 2015.

Of the $3.7 trillion the U.S. government spent that year, the largest expenditures were Social Security , health care , and defense and security , according to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities .

Several safety net programs are included in the 10% spent on social services:

Supplemental Security Income , which provides cash support to the elderly and disabled poor

Assistance with home energy bills

Programs that provide help to abused and neglected children

In addition, programs that primarily help the middle class, namely the Earned Income Tax Credit and the Child Tax Credit, are included in the 10%.

Don’t Miss: How Many Registered Democrats And Republicans Are There

At Least 60 Afghans And 13 Us Service Members Killed By Suicide Bombers And Gunmen Outside Kabul Airport: Us Officials

Two suicide bombers and gunmen attacked crowds of Afghans flocking to Kabul’s airport Thursday, transforming a scene of desperation into one of horror in the waning days of an airlift for those fleeing the Taliban takeover. At least 60 Afghans and 13 U.S. troops were killed, Afghan and U.S. officials said.

Welfare Spending By President And Congress From 1959 To 2014

Republicans’ Facts About Welfare Are “Not Factually True”

America faces many problems today. The current economic recovery has been the slowest since the Great Depression, the national debt has surpassed $18 trillion, and the federal government continues to spend more than it collects. While its not unusual, unethical, or unconstitutional for the federal government to operate with deficits at times, the question is why does Washington continue to overspend? Is there a legitimate reason or is it neo-politics? In this article, well take a look at spending on welfare programs during each presidents term from J.F.K. to Obama. Well also look at the party in control of Congress. Which one was the biggest spender as it pertains to welfare programs?

The Dark Side of Social Benefits

Politicians love to sing their own praises and for a very good reason. Otto von Bismarck, the first Chancellor of Germany, made an astute political observation in the 1880s when he stated, A man who has a pension for his old age is much easier to deal with than a man without that prospect. Bismarck openly acknowledged that this was a state-socialist idea and went on to say, Whoever embraces this idea will come to power. Thus, the strategy of using legislation to gain votes was forever embedded in the political landscape.

Welfare Spending

Lets take a thorough look at federal welfare spending from 1959 through 2013. The following graph includes spending for two data points:

Democrats in control: 13.7%

Republicans in control: 3.5%

Don’t Miss: What Republicans Voted Against The Repeal Of Obamacare

What Is Governments Role In Caring For The Most Needy

Nearly six-in-ten Americans say government has a responsibility to take care of those who cannot take care of themselves. Do these views vary depending on whether the respondent has personally benefited from a government entitlement program?

These data suggest the answer is a qualified yes. Overall, those who have received benefits from at least one of the six major programs are somewhat more likely than those who havent to say government is responsible for caring for those who cannot help themselves .

When the analysis focuses just on just the respondents who have received benefits from at least one of the four programs that target the needy, the gap between entitlement recipients and other adults increases to eight percentage points .

Some larger differences in attitudes toward governments role emerge when the results are broken down by specific program, though in every case majorities of both recipients and non-recipients affirmed that government has the obligation to help those most in need.

For example, nearly three-quarters of those who ever received welfare benefits say government has a duty to care for those who cannot care for themselves. In contrast, less than six-in-ten of those who have never been on welfare agree.

Similar double-digit gaps surface between non-recipients and those who ever received food stamps and Medicaid .

How Come We Are Red And Blue Instead Of Purple

Republicans to live outside of urban areas, while Democrats tend to prefer living inside of urban areas.

Rural areas are almost exclusively Republican well strong urban areas are almost exclusively democratic.

Republicans also tend to stress traditional family values, which may be why only 1 out of 4 GLBTQI individuals identify with the GOP.

63% of people who earn more than $200k per year vote for Republicans, while 63% of people who earn less than $15k per year vote for Democrats.

64% of Americans believe that labor unions are necessary to protect working people, but only 43% of GOP identified votes view labor unions in a favorable way.

The economics of the United States seem to have greatly influenced how people identify themselves when it comes to their preferred political party. People who are concerned about their quality of life and have a fair amount of money tend to vote Republican. Those who have fallen on hard times or work in union related jobs tend to vote for Democrats. From 2003 to today, almost all of demographic gaps have been shifting so that Republicans and Democrats are supported equally. The only true difference is on the extremes of the income scale. The one unique fact about Democrats is that they are as bothered by their standard of living as Republicans tend to be.

Don’t Miss: When Did Republicans Turn Against Nixon

States Have Shifted To The Right

Democrats are floating a plan to tax stock buybacks.

Even excluding health insurance which some experts argue should not count people in this patch of Appalachia draw between a fifth and a third of their income from the public purse.

Perhaps the politics of welfare is changing up to a point. Democrats made big gains this year in elections for the House and several statehouses, running largely on the promise that they would protect the most recent addition to the safety net: the Affordable Care Act, including the expansion of Medicaid in many states. But championing the safety net does not necessarily resonate in the places that most need it.

Take Daniel Lewis, who crashed his car into a coal truck 15 years ago, breaking his neck and suffering a blood clot in his brain when he was only 21. He is grateful for the $1,600 a month his family gets from disability insurance; for his Medicaid benefits; for the food stamps he shares with his wife and two children.

Every need I have has been met, Mr. Lewis told me. He disagrees with the governors proposal to demand that Medicaid recipients get a job. And yet, in 2016, he voted for Mr. Trump. It was the lesser of two evils, he said.

About 13 percent of Harlans residents are receiving disability benefits. More than 10,000 get food stamps. But in 2015 almost two-thirds voted for Mr. Bevin. In 2016 almost 9 out of 10 chose Mr. Trump.

Program Goals And Demographics

Larger group differences emerge when the results are broken down by age and income levelsdifferences that are often directly related to the goals of specific benefits programs.

For example, adults 65 and older are nearly three times as likely to have received an entitlement benefit during their lives as those adults under the age of 30 . Thats not surprising, since nearly nine-in-ten older adults have received Social Security and78% have gotten Medicare benefits. Both programs were specifically created for seniors with age requirements that limit participation by younger adults.

Similarly, Americans with family incomes of less than $30,000 a year are significantly more likely as those with family incomes of $100,000 or more to have gotten entitlement help from the government . Again, this difference is not surprising, as assisting the poor is the primary objective of such financial means-tested programs as food stamps, welfare assistance and Medicaid.

Also Check: Why Do Republicans Wear Blue Ties

Which Party Are You

The average Republican is 50, while the average Democrat is 47.

55% of married women will vote Republican.

GOP candidates earn 59 percent of all Protestant votes, 67 percent of all white Protestant votes, 52 percent of the Catholic vote, making them a Christian majority party.

Only 1 out of 4 Jewish voters will support Republicans.

If you are white and have a college education, there is a 20% greater chance that you will be a Republican instead of a Democrat.

American Republicans have been found to be among the most generous people on earth, and not just financially. Republicans also provide more volunteer hours and donate blood more frequently.

Here is what we really come to when it comes to political party demographics. It doesnt matter if youre a Republican or a Democrat. What matters is that everyone is able to take advantage of the diversity that makes the United States so unique. Instead of trying to prove one way is the only correct path, both parties coming together to work together could create some amazing changes for the modern world. Until we learn to compromise, however, the demographic trends will continue to equalize and polarize until only gridlock remains. If that happens, then nothing will ever get done and each party will blame the other.

Taking The Perspective Of Others Proved To Be Really Hard

The divide in the United States is wide, and one indication of that is how difficult our question proved for many thoughtful citizens. A 77-year-old Republican woman from Pennsylvania was typical of the voters who struggled with this question, telling us, This is really hard for me to even try to think like a devilcrat!, I am sorry but I in all honesty cannot answer this question. I cannot even wrap my mind around any reason they would be good for this country.

Similarly, a 53-year-old Republican from Virginia said, I honestly cannot even pretend to be a Democrat and try to come up with anything positive at all, but, I guess they would vote Democrat because they are illegal immigrants and they are promised many benefits to voting for that party. Also, just to follow what others are doing. And third would be just because they hate Trump so much. The picture she paints of the typical Democratic voter being an immigrant, who goes along with their party or simply hates Trump will seem like a strange caricature to most Democratic voters. But her answer seems to lack the animus of many.;;

Democrats struggled just as much as Republicans. A 33-year-old woman from California told said, i really am going to have a hard time doing this but then offered that Republicans are morally right as in values, going to protect us from terrorest and immigrants, going to create jobs.

Recommended Reading: Did Trump Say Republicans Were Dumb

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The best $2,000 I ever spent: many, many rounds of bingo

Dana Rodriguez for Vox

It’s the one activity where money becomes more magical and less weighty.

The one time in my life, aside from sleeping, when I’m not obsessing about money is when I’m playing bingo. I know that sounds ironic, but bingo is my mental escape, offering a few hours where the numbers in front of me all start with a letter, not a dollar sign.

I’ve been in debt my entire adult life, first with student loans from undergrad and the law school I never graduated from, then from living above my means — not hard to do on a $40,000 New York City salary.

In my 20s and 30s, I ignored my debt, thinking it would somehow eventually resolve itself (how, I’m not sure, but I assumed more money would simply materialize the older I got). When, at 40, I realized that wasn’t quite how real life worked, I dedicated myself to earning as much as I could as a freelancer, with a mix of book royalties, articles, and a part-time copywriting gig.

The downside of self-employment is I never feel like I can truly be “off.” There’s always a potential story at my fingertips, and thereby a way to chip away at my looming debt, which hovers at a little over $50,000.

My local bingo hall is my happy place, somewhere I can go any night of the week and know I’ll leave with a smile on my face no matter what the outcome. It’s the one activity that lets me escape, well, me, where money becomes more magical and less weighty.

I live within walking distance of a bingo hall that offers games every evening, plus an additional 10:30 Tuesday night game, and Friday morning and Sunday afternoon games. Over the last four years, I’ve attended almost all of them, and win or lose, each was money well spent.

Entry costs $5, for the bare minimum number of two boards for 12 rounds, but I never play the minimum. You can buy extras for a dollar or two, depending on the value of the round; most offer $100 or $200 jackpots, with some rounds for larger amounts ranging from $1,000 to over $4,000, depending on how much has been bet. The first night I attended I spent around $30 and won $200, thus turning me into an instant convert. Now, I usually spend around $50 each time I go.

Lately, that’s every few months, but after the 2016 election I played bingo several times a week to help me forget about the news. I was a drag queen bingo regular in the East Village in the ’90s, but there we were competing for Queer as Folk DVD box sets and giant glasses filled with margaritas. This is serious, adult bingo, the kind where you’ll get shushed for talking too loudly.

The bingo hall is a place where I can forget about myself for two hours. For that small slice of time, I’m not a failed adult riddled with debt. I’m simply a middle-aged white lady with a dabber in her hand. All those money worries and existential angsty thoughts that rush to the surface whenever I have a free moment — Will be able to retire someday? Will I ever be a mom? What if [insert horrible catastrophe befalling anyone in my family]? — I can push to the back burner and focus solely on getting five stamps in a row, or a pyramid or four corners, or whatever variation of the game we’re playing at that particular moment.

I’d be lying if I said the prospect of winning doesn’t motivate me to settle in alongside women 30 and 40 years my senior, who come armed with special bingo bags that hold a rainbow array of dabbers and tape to fasten their boards together. Money, of course, is the main reason any of us lurk at the bingo hall. Another reason I stopped going to casinos is that the only games I like, slot machines, have the lowest odds. After reading that, I couldn’t quite bring myself to revel in their blinking lights and beckoning noises.

With bingo, I’ve never stopped to look up the odds (please don’t tell me if they’re bad). Instead, I let myself sink into a fantasy world where I fully believe that I just might walk away with a stack of cash. All that’s required of me is to stamp red or green or purple blobs of ink onto a piece of pre-printed paper. I love the sense of excitement that washes over me at the start of each new round — all those blanks squares, all those possible chances.

With bingo, I’ve never stopped to look up the odds. Instead, I let myself sink into a fantasy world where I fully believe that I just might walk away with a stack of cash.

When my boyfriend and I moved within 10 minutes of Atlantic City, I worried that the lure of the casinos would be impossible to resist. Yet one evening in a smoky local casino cured any romanticism I might have had. I don’t know how to play casino games like poker or craps, and I don’t care to. I don’t want to think too much when I’m hoping to catch a financial windfall, or for it to feel like work, but I do want my mind to be occupied.

Bingo fills that purpose perfectly. There’s no free time to stare dazedly at Twitter. I can’t slack off or I’ll miss a number being called. The avid players know to look up at the TV screens to see which number will be called next before it’s actually spoken. Bingo makes me feel like I’m an active participant who, with a combination of luck and alertness, has a chance of winning. Bingo is full of colorful markers, breathless anticipation, and quick reflexes, surrounded by people who are a little more relaxed than the average casino-goer. Regular players give advice to newcomers, call out happy birthday to each other, and root for their friends as much as themselves. What I’ve learned is that I don’t actually love gambling; I love bingo.

I allow myself to be fully immersed in the drama. I double and triple check my cards, mentally noting which ones are close to winning and which ones are duds. I rub the orange hair of the troll doll I bought on my first visit. I silently chant “I-18” or “G-57” until the combination echoes in my mind. There’s a ripple of energy that races around the room when someone is about to hit bingo, knowledge that is transmitted either through a small gasp passed as if playing an almost-silent game of telephone or a collective Spidey sense shared by the players.

The few times my good-luck tactics have actually “worked” and I’ve looked up at the screen to see my number about to be called, I’ve felt euphoric. It’s what I imagine winning a game show — my ultimate bucket list item — would be like. I don’t care whether it’s luck or chance or fate. In that moment, I’m not, for once, thinking about the money. My entire being is focused simply on hearing that magic letter and number spoken into the microphone by the person sitting behind that spinning wheel, at which point I can shoot my hand in the air and call out as loud as I can, “BINGO!” There are no other moments in my life where I get to literally yell out a victory.

There are no other moments in my life where I get to literally yell out a victory

That possibility is truly why I play bingo. For $50, I get to spend an afternoon or evening utterly caught up in the dramatic highs and lows of being three away, then two, then one. I know going in that I have just as much of a chance as anyone else in the room.

While the result may be just as predetermined and out of my control as playing the lottery, bingo feels more active, like if I pay close enough attention, I just might win. History has shown that I truly might; I’ve won four times, out of approximately 40 visits, totaling $1,350 (with one momentous Super Bowl payout of $1,000). I’ve spent around $2,000 by my estimation, so my total losses are $750.

Given those numbers, you might assume I’m just sinking myself deeper into debt, and technically, you’d be right. But I’m purchasing much more than that potential chance to become a champion. I’m buying myself a temporary shortcut to mental health, a reprieve from that constant inner refrain that loops from you’ll never be good enough to why even bother trying. Unlike casinos, I never sense that the people around me are gambling with their rent money in a last-ditch effort to get rich. We’re all playing bingo, with an emphasis on play. With bingo, I don’t have to be smart or ambitious. I’m not being measured by my net worth, or anything else.

In lottery player parlance, I’m a dreamer, someone who sees their gambling as the “chance to fantasize about winning money.” A bingo victory feels likely enough that it makes sense to try, while knowing that what I could potentially win during any given round, while exciting, wouldn’t change my life. At best, I’d pay down a small fraction of my debt. Competing for a welcome but not mind-boggling amount of money, though, feels more sane and satisfying than wondering if I’ll win the next Mega Millions.

Plus, bingo is more communal, and more fun; in that room, I’m a dreamer surrounded by dreamers. I know that someone in the same room as me will be walking away the big winner. I can say congratulations, and see the look on their face when they win — and know it might be me next time.

Rachel Kramer Bussel writes about sex, dating, books, culture, and herself. She is the editor of over 60 anthologies, including the Cleis Press Best Women’s Erotica of the Year series.

from Vox - All https://ift.tt/35fkdb5

0 notes

Text

The best $2,000 I ever spent: many, many rounds of bingo

Dana Rodriguez for Vox

It’s the one activity where money becomes more magical and less weighty.

The one time in my life, aside from sleeping, when I’m not obsessing about money is when I’m playing bingo. I know that sounds ironic, but bingo is my mental escape, offering a few hours where the numbers in front of me all start with a letter, not a dollar sign.

I’ve been in debt my entire adult life, first with student loans from undergrad and the law school I never graduated from, then from living above my means — not hard to do on a $40,000 New York City salary.

In my 20s and 30s, I ignored my debt, thinking it would somehow eventually resolve itself (how, I’m not sure, but I assumed more money would simply materialize the older I got). When, at 40, I realized that wasn’t quite how real life worked, I dedicated myself to earning as much as I could as a freelancer, with a mix of book royalties, articles, and a part-time copywriting gig.

The downside of self-employment is I never feel like I can truly be “off.” There’s always a potential story at my fingertips, and thereby a way to chip away at my looming debt, which hovers at a little over $50,000.

My local bingo hall is my happy place, somewhere I can go any night of the week and know I’ll leave with a smile on my face no matter what the outcome. It’s the one activity that lets me escape, well, me, where money becomes more magical and less weighty.

I live within walking distance of a bingo hall that offers games every evening, plus an additional 10:30 Tuesday night game, and Friday morning and Sunday afternoon games. Over the last four years, I’ve attended almost all of them, and win or lose, each was money well spent.

Entry costs $5, for the bare minimum number of two boards for 12 rounds, but I never play the minimum. You can buy extras for a dollar or two, depending on the value of the round; most offer $100 or $200 jackpots, with some rounds for larger amounts ranging from $1,000 to over $4,000, depending on how much has been bet. The first night I attended I spent around $30 and won $200, thus turning me into an instant convert. Now, I usually spend around $50 each time I go.

Lately, that’s every few months, but after the 2016 election I played bingo several times a week to help me forget about the news. I was a drag queen bingo regular in the East Village in the ’90s, but there we were competing for Queer as Folk DVD box sets and giant glasses filled with margaritas. This is serious, adult bingo, the kind where you’ll get shushed for talking too loudly.

The bingo hall is a place where I can forget about myself for two hours. For that small slice of time, I’m not a failed adult riddled with debt. I’m simply a middle-aged white lady with a dabber in her hand. All those money worries and existential angsty thoughts that rush to the surface whenever I have a free moment — Will be able to retire someday? Will I ever be a mom? What if [insert horrible catastrophe befalling anyone in my family]? — I can push to the back burner and focus solely on getting five stamps in a row, or a pyramid or four corners, or whatever variation of the game we’re playing at that particular moment.

I’d be lying if I said the prospect of winning doesn’t motivate me to settle in alongside women 30 and 40 years my senior, who come armed with special bingo bags that hold a rainbow array of dabbers and tape to fasten their boards together. Money, of course, is the main reason any of us lurk at the bingo hall. Another reason I stopped going to casinos is that the only games I like, slot machines, have the lowest odds. After reading that, I couldn’t quite bring myself to revel in their blinking lights and beckoning noises.

With bingo, I’ve never stopped to look up the odds (please don’t tell me if they’re bad). Instead, I let myself sink into a fantasy world where I fully believe that I just might walk away with a stack of cash. All that’s required of me is to stamp red or green or purple blobs of ink onto a piece of pre-printed paper. I love the sense of excitement that washes over me at the start of each new round — all those blanks squares, all those possible chances.

With bingo, I’ve never stopped to look up the odds. Instead, I let myself sink into a fantasy world where I fully believe that I just might walk away with a stack of cash.

When my boyfriend and I moved within 10 minutes of Atlantic City, I worried that the lure of the casinos would be impossible to resist. Yet one evening in a smoky local casino cured any romanticism I might have had. I don’t know how to play casino games like poker or craps, and I don’t care to. I don’t want to think too much when I’m hoping to catch a financial windfall, or for it to feel like work, but I do want my mind to be occupied.

Bingo fills that purpose perfectly. There’s no free time to stare dazedly at Twitter. I can’t slack off or I’ll miss a number being called. The avid players know to look up at the TV screens to see which number will be called next before it’s actually spoken. Bingo makes me feel like I’m an active participant who, with a combination of luck and alertness, has a chance of winning. Bingo is full of colorful markers, breathless anticipation, and quick reflexes, surrounded by people who are a little more relaxed than the average casino-goer. Regular players give advice to newcomers, call out happy birthday to each other, and root for their friends as much as themselves. What I’ve learned is that I don’t actually love gambling; I love bingo.

I allow myself to be fully immersed in the drama. I double and triple check my cards, mentally noting which ones are close to winning and which ones are duds. I rub the orange hair of the troll doll I bought on my first visit. I silently chant “I-18” or “G-57” until the combination echoes in my mind. There’s a ripple of energy that races around the room when someone is about to hit bingo, knowledge that is transmitted either through a small gasp passed as if playing an almost-silent game of telephone or a collective Spidey sense shared by the players.

The few times my good-luck tactics have actually “worked” and I’ve looked up at the screen to see my number about to be called, I’ve felt euphoric. It’s what I imagine winning a game show — my ultimate bucket list item — would be like. I don’t care whether it’s luck or chance or fate. In that moment, I’m not, for once, thinking about the money. My entire being is focused simply on hearing that magic letter and number spoken into the microphone by the person sitting behind that spinning wheel, at which point I can shoot my hand in the air and call out as loud as I can, “BINGO!” There are no other moments in my life where I get to literally yell out a victory.

There are no other moments in my life where I get to literally yell out a victory

That possibility is truly why I play bingo. For $50, I get to spend an afternoon or evening utterly caught up in the dramatic highs and lows of being three away, then two, then one. I know going in that I have just as much of a chance as anyone else in the room.

While the result may be just as predetermined and out of my control as playing the lottery, bingo feels more active, like if I pay close enough attention, I just might win. History has shown that I truly might; I’ve won four times, out of approximately 40 visits, totaling $1,350 (with one momentous Super Bowl payout of $1,000). I’ve spent around $2,000 by my estimation, so my total losses are $750.

Given those numbers, you might assume I’m just sinking myself deeper into debt, and technically, you’d be right. But I’m purchasing much more than that potential chance to become a champion. I’m buying myself a temporary shortcut to mental health, a reprieve from that constant inner refrain that loops from you’ll never be good enough to why even bother trying. Unlike casinos, I never sense that the people around me are gambling with their rent money in a last-ditch effort to get rich. We’re all playing bingo, with an emphasis on play. With bingo, I don’t have to be smart or ambitious. I’m not being measured by my net worth, or anything else.

In lottery player parlance, I’m a dreamer, someone who sees their gambling as the “chance to fantasize about winning money.” A bingo victory feels likely enough that it makes sense to try, while knowing that what I could potentially win during any given round, while exciting, wouldn’t change my life. At best, I’d pay down a small fraction of my debt. Competing for a welcome but not mind-boggling amount of money, though, feels more sane and satisfying than wondering if I’ll win the next Mega Millions.

Plus, bingo is more communal, and more fun; in that room, I’m a dreamer surrounded by dreamers. I know that someone in the same room as me will be walking away the big winner. I can say congratulations, and see the look on their face when they win — and know it might be me next time.

Rachel Kramer Bussel writes about sex, dating, books, culture, and herself. She is the editor of over 60 anthologies, including the Cleis Press Best Women’s Erotica of the Year series.

from Vox - All https://ift.tt/35fkdb5

0 notes

Text

The best $2,000 I ever spent: many, many rounds of bingo

Dana Rodriguez for Vox

It’s the one activity where money becomes more magical and less weighty.

The one time in my life, aside from sleeping, when I’m not obsessing about money is when I’m playing bingo. I know that sounds ironic, but bingo is my mental escape, offering a few hours where the numbers in front of me all start with a letter, not a dollar sign.

I’ve been in debt my entire adult life, first with student loans from undergrad and the law school I never graduated from, then from living above my means — not hard to do on a $40,000 New York City salary.

In my 20s and 30s, I ignored my debt, thinking it would somehow eventually resolve itself (how, I’m not sure, but I assumed more money would simply materialize the older I got). When, at 40, I realized that wasn’t quite how real life worked, I dedicated myself to earning as much as I could as a freelancer, with a mix of book royalties, articles, and a part-time copywriting gig.

The downside of self-employment is I never feel like I can truly be “off.” There’s always a potential story at my fingertips, and thereby a way to chip away at my looming debt, which hovers at a little over $50,000.

My local bingo hall is my happy place, somewhere I can go any night of the week and know I’ll leave with a smile on my face no matter what the outcome. It’s the one activity that lets me escape, well, me, where money becomes more magical and less weighty.

I live within walking distance of a bingo hall that offers games every evening, plus an additional 10:30 Tuesday night game, and Friday morning and Sunday afternoon games. Over the last four years, I’ve attended almost all of them, and win or lose, each was money well spent.

Entry costs $5, for the bare minimum number of two boards for 12 rounds, but I never play the minimum. You can buy extras for a dollar or two, depending on the value of the round; most offer $100 or $200 jackpots, with some rounds for larger amounts ranging from $1,000 to over $4,000, depending on how much has been bet. The first night I attended I spent around $30 and won $200, thus turning me into an instant convert. Now, I usually spend around $50 each time I go.

Lately, that’s every few months, but after the 2016 election I played bingo several times a week to help me forget about the news. I was a drag queen bingo regular in the East Village in the ’90s, but there we were competing for Queer as Folk DVD box sets and giant glasses filled with margaritas. This is serious, adult bingo, the kind where you’ll get shushed for talking too loudly.

The bingo hall is a place where I can forget about myself for two hours. For that small slice of time, I’m not a failed adult riddled with debt. I’m simply a middle-aged white lady with a dabber in her hand. All those money worries and existential angsty thoughts that rush to the surface whenever I have a free moment — Will be able to retire someday? Will I ever be a mom? What if [insert horrible catastrophe befalling anyone in my family]? — I can push to the back burner and focus solely on getting five stamps in a row, or a pyramid or four corners, or whatever variation of the game we’re playing at that particular moment.

I’d be lying if I said the prospect of winning doesn’t motivate me to settle in alongside women 30 and 40 years my senior, who come armed with special bingo bags that hold a rainbow array of dabbers and tape to fasten their boards together. Money, of course, is the main reason any of us lurk at the bingo hall. Another reason I stopped going to casinos is that the only games I like, slot machines, have the lowest odds. After reading that, I couldn’t quite bring myself to revel in their blinking lights and beckoning noises.

With bingo, I’ve never stopped to look up the odds (please don’t tell me if they’re bad). Instead, I let myself sink into a fantasy world where I fully believe that I just might walk away with a stack of cash. All that’s required of me is to stamp red or green or purple blobs of ink onto a piece of pre-printed paper. I love the sense of excitement that washes over me at the start of each new round — all those blanks squares, all those possible chances.

With bingo, I’ve never stopped to look up the odds. Instead, I let myself sink into a fantasy world where I fully believe that I just might walk away with a stack of cash.

When my boyfriend and I moved within 10 minutes of Atlantic City, I worried that the lure of the casinos would be impossible to resist. Yet one evening in a smoky local casino cured any romanticism I might have had. I don’t know how to play casino games like poker or craps, and I don’t care to. I don’t want to think too much when I’m hoping to catch a financial windfall, or for it to feel like work, but I do want my mind to be occupied.

Bingo fills that purpose perfectly. There’s no free time to stare dazedly at Twitter. I can’t slack off or I’ll miss a number being called. The avid players know to look up at the TV screens to see which number will be called next before it’s actually spoken. Bingo makes me feel like I’m an active participant who, with a combination of luck and alertness, has a chance of winning. Bingo is full of colorful markers, breathless anticipation, and quick reflexes, surrounded by people who are a little more relaxed than the average casino-goer. Regular players give advice to newcomers, call out happy birthday to each other, and root for their friends as much as themselves. What I’ve learned is that I don’t actually love gambling; I love bingo.

I allow myself to be fully immersed in the drama. I double and triple check my cards, mentally noting which ones are close to winning and which ones are duds. I rub the orange hair of the troll doll I bought on my first visit. I silently chant “I-18” or “G-57” until the combination echoes in my mind. There’s a ripple of energy that races around the room when someone is about to hit bingo, knowledge that is transmitted either through a small gasp passed as if playing an almost-silent game of telephone or a collective Spidey sense shared by the players.

The few times my good-luck tactics have actually “worked” and I’ve looked up at the screen to see my number about to be called, I’ve felt euphoric. It’s what I imagine winning a game show — my ultimate bucket list item — would be like. I don’t care whether it’s luck or chance or fate. In that moment, I’m not, for once, thinking about the money. My entire being is focused simply on hearing that magic letter and number spoken into the microphone by the person sitting behind that spinning wheel, at which point I can shoot my hand in the air and call out as loud as I can, “BINGO!” There are no other moments in my life where I get to literally yell out a victory.

There are no other moments in my life where I get to literally yell out a victory

That possibility is truly why I play bingo. For $50, I get to spend an afternoon or evening utterly caught up in the dramatic highs and lows of being three away, then two, then one. I know going in that I have just as much of a chance as anyone else in the room.

While the result may be just as predetermined and out of my control as playing the lottery, bingo feels more active, like if I pay close enough attention, I just might win. History has shown that I truly might; I’ve won four times, out of approximately 40 visits, totaling $1,350 (with one momentous Super Bowl payout of $1,000). I’ve spent around $2,000 by my estimation, so my total losses are $750.

Given those numbers, you might assume I’m just sinking myself deeper into debt, and technically, you’d be right. But I’m purchasing much more than that potential chance to become a champion. I’m buying myself a temporary shortcut to mental health, a reprieve from that constant inner refrain that loops from you’ll never be good enough to why even bother trying. Unlike casinos, I never sense that the people around me are gambling with their rent money in a last-ditch effort to get rich. We’re all playing bingo, with an emphasis on play. With bingo, I don’t have to be smart or ambitious. I’m not being measured by my net worth, or anything else.

In lottery player parlance, I’m a dreamer, someone who sees their gambling as the “chance to fantasize about winning money.” A bingo victory feels likely enough that it makes sense to try, while knowing that what I could potentially win during any given round, while exciting, wouldn’t change my life. At best, I’d pay down a small fraction of my debt. Competing for a welcome but not mind-boggling amount of money, though, feels more sane and satisfying than wondering if I’ll win the next Mega Millions.

Plus, bingo is more communal, and more fun; in that room, I’m a dreamer surrounded by dreamers. I know that someone in the same room as me will be walking away the big winner. I can say congratulations, and see the look on their face when they win — and know it might be me next time.

Rachel Kramer Bussel writes about sex, dating, books, culture, and herself. She is the editor of over 60 anthologies, including the Cleis Press Best Women’s Erotica of the Year series.

from Vox - All https://ift.tt/35fkdb5

0 notes

Link

Written by R. Ann Parris on The Prepper Journal.

Editors Note: Another guest contribution from R. Ann Parris to The Prepper Journal. A timely subject with so many of those who serve us daily having to forgo a paycheck this week because of the children we elect (repeatedly) to represent us.

No-buy and pantry-only challenges can make great assessment tools for preppers. Go ahead and do one – any month, although there’s some added value to certain seasons. It’ll take a little prep work to avoid unnecessary expenses and allow accurate tracking, but the data gathered can be invaluable for identifying gaps in our supplies and challenges we’ll face.

Apply Ratios

When you trial what it’s like to live and eat off of your storage, make sure you maintain whatever duration and pacing or proportion is stocked. That means if I only have enough coffee and tea for a daily cup in my six months of storage, that’s all I get during my test run.

That in-stock equivalency ratio applies to everything.

What are your cooking options? How much fuel do you actually have for cooking, for heating, for light? How much water does it take to wash dishes and laundry, and keep clean? Brush teeth? Water gardens and pets and livestock? How much time and effort would you spend collecting that water if nothing came out of your faucet tomorrow?

Be honest with yourself, and test it, whatever “it” is. Otherwise, you’re guessing and gambling. We spend an awful lot of money and time on preparedness to let it be riding on pulling the right card.

Hiccups & Hitches

Daily modern life has requirements we can’t wedge into our no-buy, pantry-only challenges. Things like school projects, repairs, and travel can all interfere with our test.

That’s okay. After all, the most common disasters we’ll face are personal and local, many of which will still require work, appointments, educated children, and good/decent hygiene.

Please don’t go under a 2-4 week supply, in case something does happen. (You’ll have savings from not spending for replacements, but we’re trying to avoid empty pantries if a snowstorm, flood, etc. limits travel and resources in your area.)

Please keep your tanks topped off, again, in case something does happen.

Please see a doctor/veterinarian immediately, don’t wait just to try and get to the end of the challenge month.

Track any hiccups and hitches. They’re exactly what we want for formulating good plans.

Non-Grocery Preps

Skip new movies, TV, books and magazines, and find an alternative for entertainment. Depending on your situation, there’s liable to be a household riot if you unplug the internet for even a week or two, but track the hours spent there.

Yes, we’re likely to have busier lives. Everything will take longer to accomplish if we’re limiting or eliminating powered assistance like gas/electric stoves and tools, and if we’re using books for how-to instead of popping up 3,000 results on the internet in 0.015 seconds.

Part of what is normally our down-time reading and surfing and game playing will end up replaced by tasks. That doesn’t mean our need for entertainment and distraction goes away.

Throughout history we have had entertainments.

Some of the games we play and recreations we enjoy started with knights and peasants in castle eras, or got handed down to us from various native peoples. Colonists of all phases still had time for their varied gatherings, homestead games, and reading.

We may take longer to accomplish things than Medieval Europeans, Iroquois, and Incas. We’re not used to doing some of the tasks, or doing them by hand, and we lack the community and infrastructure that made their lifestyles work.

Even so, it’s unlikely we’ll never have some time to kill, or always sleep when the sun is down or it’s pouring rain.

And, again, there are a lot of things that can go big-time wrong – like job loss, fuel shortages or price skyrocketing, big bills – where our households or even the whole country is affected to one degree or another, but we still have expectations of a fairly “normal” existence.

Things like small crafts even for older kids and adults, new/different games and books, small “finger-diddle” gadgets and puzzles, tabletop and carpet versions of some of our sports, jigsaw puzzles, board games, and other distractions can help alleviate some of the “loss” from our impacted lives, lift moods, and combat stress.

Knowing what we gravitate to in our free time will let us better choose those alternative preps.

Biggies on the “non-grocery” side of the house are our electricity, heating/cooling, indoor plumbing, and waste disposal. A lot of our health, safety, and abilities revolve around them.

How many times do we flush? Do we actually have enough kitty litter or waste processing built into our plan? One way to find out is to cut the water to it and line it, or put one of those geriatric toilets with buckets and liners between it and the door to make sure it’s actually getting tracked.

How many degrees of warmth do we add to our homes autumn, winter, and spring? What’s the burn time and heat output of our alternatives? Can we create much smaller spaces to heat?

Most of us can track meters for energy use. Many already have them available for water, too. Some will have to install them or work out of tubs/tanks they can track instead.

Right now most of us have garbage men coming through or drive to a dump. Various pests are going to become a problem when trash builds up. Is there a plan for those?

Let the trash build up an extra week or two. Yes, some of what we throw away will go away or be reused in a disaster, but it’s going to be dependent on storage types and emergency systems. It’s also going to be an adjustment, not automatic.

Don’t forget that women, babies, and regularly seniors have additional daily and monthly needs that also generate laundry or waste.

Over-the-counter meds, cooking fuels, and animal feed needs – without normal scraps and treats – are others that seem to regularly escape our notice, both in budgeting and anticipating needs.

Replacements for Food Storage

I’m not talking about busting through actual storage foods – unless it’s time to rotate. We can pretty easily find facsimiles, or skip the extra packaging steps.

Instead of MREs, hit the various nuke-‘em pouches, tubs and canned stews, pasta, and rice meals and add commercial sweets and crackers.

There are all kinds of boxed and bagged noodle and rice meals that can help avoid busting into any expensive bucket and can kits. Many are nearly as fast and easy to heat. They make a decent one-to-one exchange on the Wise and Augason Farms meals for the most part.

To replicate a Mountain House meal instead, snag some of those just-add-water or frozen dinner kits that includes the meats. I’m inclined to say stick to cans, because it’ll be closer to storage foods than pre-cooking and freezing them will be.

A lot of kits have soups. Bear Creek makes a whole line that’s actually pretty good, and regularly goes on sale two for $3-$5 in our areas, so they’re already a common storage item for us. There are other options in any supermarket.

Match any “flavored” oatmeal in your storage with packets from Walmart. Same for granola and for fruits – canned for freeze-dried or if you can’t find the dehydrated versions at Dollar Tree, Ollie’s, or Walmart.

For a good test, if you don’t have extra seasonings, sweeteners, cream, etc., in your storage, make sure you’re not adding any to the challenge week/month.

Supermarket Coolers

If you’re not harvesting meat, produce, eggs, and milk products from home, make sure to switch for shelf-stable, wet-pack canned, and dried equivalents for them, too. If you can’t or you’re on your own within a household of non-preppers, make extra sure you keep track. That way, the right amount of shelf-stable alternates can be stocked.

Be aware that many of the dry and dehydrated versions, or substitutions like TVP (Textured Vegetable Protein) and beans are far lower in calories and especially fats.

Supermarket Snacks

One of the biggies to keep track of, are the treats. That’s stuff like the soda, beer, candy, bakery rolls, cakes and frosting, nummy crackers, pudding, chips, popcorn, trail mix, nuts – even the non-local fruits. Don’t forget coffee and tea, cocoa, flavored milk, and soft drinks.

You’ll need to stock equivalents or alternatives to account for the calories they contribute to your diet, and you might consider some for a pick-me-up here and there or to ease transitions from “normal” to long-term disaster eating.

Keep track of sugar consumed, too. For storage planning, sit down to make a list of how much sugar a lot of the goodies we munch require to make at home or from scratch. (That goes for water bath canning jams and fruits, too.)

Non-Grocery Goodies

That “goody” might also be non-food items – my silly routine of certain music while I do my physical therapy and Pilates or before bed, tennis balls for my dog, or my father adding to his Lego collection every 2-4 weeks and taking half the day for his weekly shopping instead of 2-3 hours because he’s chatty and likes to look (at everything).

Many of us are accustomed to – if not hooked on – news and information, connectivity, gaming, and social media. “Goodies” can also be time spent on sports, reading, watching TV and movies, or outings that would no longer be safe or affordable in a crisis.

Our bodies and our minds are adapted to having certain things. Many people will react just like an addict in withdrawal if their goodies are eliminated, regardless of their form. If we can ease that, we can ease the stresses.

Some of those activities, outings, and routines are also already the ways we de-stress. Eliminating that relief while adding other stressors is a recipe for problems.

The basics take precedence, but prepping to retain and replace some “goodies” is worth consideration.

Track the Results

“Track it” keeps getting repeated. And by track it, I mean, track it. Write it down. Write down your feelings and your observations of others’ ongoing personalities and opinions as well.

It’s important.

A trial of a week or two will open some eyes. A trial of a month will give you a lot more information. We can use the data we gather to better plan for all aspects, from transition phases from “normal” to “okay, this is going to be longer than expected” all the way out to disasters we know from the outset are going to be huge and life-altering.

We only have that data to apply if we try it – and if we adequately track it. Otherwise, we’re making our plans based on guesses and somebody else’s say so. Those kinds of preparations are better than nothing, but do we really want to gamble health, safety, and survival on them?

Follow The Prepper Journal on Facebook!

The post No-Buy & Pantry-Only Challenges appeared first on The Prepper Journal.

from The Prepper Journal Don't forget to visit the store and pick up some gear at The COR Outfitters. How prepared are you for emergencies? #SurvivalFirestarter #SurvivalBugOutBackpack #PrepperSurvivalPack #SHTFGear #SHTFBag

0 notes

Link

The latest report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) makes it vividly clear that averting catastrophic climate change means rapidly reducing the use of fossil fuels, getting as close to zero as possible, as soon as practicably possible. The US needs to fully decarbonize by mid-century or shortly thereafter.

Big Oil, at least with its public face, has acknowledged that reality and is supporting a revenue-neutral carbon tax in the US (one that, not incidentally, would shelter the industry from legal threats based on climate change). It is attempting to act, or at least to be seen as acting, as a reasonable partner in the federal climate effort.

Down at the state level, where media pays less attention? Not so much.

Take what’s happening in Washington and Colorado. In those states, citizens who are tired of waiting for their elected officials to act are resorting to direct democracy: with ballot initiatives, up for votes on November 6, that would directly take on fossil fuels. (Washington’s would put a price on carbon emissions; Colorado’s would radically reduce oil and gas drilling.)

Shutterstock

According to their public records, in just those two states, just this year, oil and gas — both directly and through PACs — has dumped $47 million into efforts to crush the initiatives. That number could easily top $50 million by the time of the election. On two underdog state initiatives!

Climate hawks often debate whether it works to frame Big Oil as the villain in the climate fight. But it’s not really a “messaging” question here. In these state fights over fossil fuels, Big Oil is playing the villain in a very non-metaphorical, non-symbolic way, in the form of spending outrageous amounts of money to fight off climate action.

These initiatives illustrate, if it wasn’t already obvious, that state-by-state climate policy is going to be an uphill battle. In each state, support for the climate side comes from underfunded citizen and public-interest groups — and for the most part, only the ones inside the state. Meanwhile, Big Oil, backed by ideologically aligned billionaires like the Koch brothers, has effectively unlimited funds to spend on every one of these fights. It’s overwhelmingly asymmetrical.

Let’s take a quick look at each one.

I-1631, the initiative on Washington’s ballot this year, would charge a fee for carbon pollution (“fee” is not just a clever euphemism for tax; it’s actually a fee under state law).

It would start at $15 per ton in 2020 and rise $2 a year (plus inflation) until 2035, where it would reach around $55. If state carbon targets are being reached, it would stay there; if not, it would continue upward.

That is a comparatively mild carbon price compared to, say, what Canada just implemented nation-wide, or even what oil companies are supporting at the federal level.

The revenue would be spent on clean energy, water, and forestry projects across the state, with around 30 percent of the investment targeted toward the most vulnerable communities. (You can read a longer piece I did on 1631 if you want the details.)

Ballot initiatives are always an uphill climb, but Big Oil is taking no chances. As of this writing, the No on 1631 campaign has raised $26.2 million. That is more money than has ever been marshaled for an initiative campaign, ever, in Washington history. (The previous record-holder was $22.45 million spent by opponents of a GMO food-labeling initiative in 2013.)

And almost all of that money is coming from oil companies outside the state. According to the Public Disclosure Commission, donations and in-kind contributions have come from BP ($9.5 million), Valero, and, of course, Koch Industries. Here are the top dozen donors:

PDC

Meanwhile, Clean Air Clean Energy WA, the group backing 1631, has not quite reached $15 million, mostly from state environmental groups and civic-minded billionaires like Michael Bloomberg and Bill Gates.

PDC

This extreme funding imbalance has resulted in a blizzard of misleading No on 1631 ads on local television. (I can testify — during the World Series, it was relentless, and I didn’t see a single Yes on 1631 ad.)

The ads claim the carbon fee is too big (it will crush families!) and that it’s too small (it won’t reduce carbon emissions at all!), that it exempts the state’s biggest polluters (it exempts one, which is already scheduled to close), and that the revenue will go into an unaccountable slush fund (it won’t).

One of the ads features Rob McKenna, identified only as a “Consumer Advocate & Washington State Attorney General 2005-2013.” It fails to mention that the law firm he works for, Orrick, Herrington, and Sutcliffe, lobbies for Chevron, which has donated $500,000 to the No on 1631 campaign. Washingtonians for Ethical Government has filed a complaint with the state bar association.

The deluge of out-of-state corporate money flooding into Washington this year has gotten so bad that state lawmakers are talking about new campaign-finance laws. Still, Big Oil has more than enough money to bulldoze past any complaints and run out the clock. It’s easier to flood the zone now and apologize afterward.

Washington is seeing the asymmetry between Big Oil and its opponents play out in real time, and the same thing is happening in Colorado.

In Colorado, something pretty wild is happening: Proposition 112, a ballot initiative that would effectively take a sledgehammer to the state’s oil and gas industry, gathered enough signatures to get on the ballot.

Currently, the state requires new oil or gas wells to be set back 500 feet from homes and 1,000 feet from schools. Prop 112 would increase that setback to 2,500 feet from any occupied building or “vulnerable” area like waterways or green spaces. At a stroke, it would increase the off-limits land around a qualifying structure from 18 to 450 acres.

Ah, the joy of Democrats campaigning in ballot initiative states. @BernieSanders is in Colorado today; every speaker in Boulder faced chants of “endorse 112,” an anti-fracking measure that Dems are skittish about.

— Dave Were-ghoul (@daveweigel) October 24, 2018

According to state legislative analysis, 112 would put about 85 percent of Colorado’s non-federal land off-limits to drilling — 94 percent in the five most oil-heavy counties. (Federal land is exempted, and covers 36 percent of the state’s total surface area, but that’s almost entirely in the west and very little east of the Rockies, were many wells are located.)

Opponents say 112 would devastate the industry, eliminate thousands of jobs, and reduce state tax revenue. Proponents point out that natural resource extraction jobs are less than 1 percent of state jobs, the industry gets more in state subsidies than it pays in taxes, and the health benefits will outweigh the costs.

Whatever the merits, it has Big Oil completely freaked out. Protect Colorado, the group leading the opposition, has raised $35.6 million so far, overwhelmingly from the oil and gas industry, companies like PDC Energy, Anadarko Petroleum, SRC Energy, and Noble Energy.

Noble is a particularly notable case. It is funneling millions of dollars into TV ads in the state, in a way that it says bypasses disclosure laws. David Sirota and Chase Woodruff report: “The maneuver — which pioneers a novel way for corporations to circumvent disclosure statutes and inject money directly into elections — has been blessed by the office of Colorado Secretary of State Wayne Williams, who has led a Republican political group bankrolled by [Noble].”

Sounds totally above-board!

[embedded content]

Meanwhile, Colorado Rising, the group backing the initiative, has raised [checks notes] a little more than $800,000 (just $34.8 million to go!). The initiative has proven too bold and sweeping for the tastes of mainstream environmental groups and the Democratic Party, neither of which have coughed up a penny. It’s just some individual donors, Food & Water Watch, and, intriguingly, Google co-founder Sergey Brin’s family foundation.

It’s not exactly a fair fight.

So, $47 million, on just these two initiatives, just this year.

That’s the tip of the iceberg. Koch money, especially as funneled through state groups like Americans for Prosperity, killed a bold public-transit initiative in Nashville this year — just the latest in more than two dozen local- and state-level transit efforts they have rallied against, including an important one in Phoenix. They’ve also joined in a fight against a clean-energy initiative in Arizona, against which the state utility has now spent $22 million.

The current effort to repeal the recent gas tax increase in California — the disastrously misguided Proposition 6 — is backed by a vaguely named group Reform California. It’s unclear who’s funding that group, but … c’mon.

This is no great revelation: Despite its recent happy talk to the contrary, the oil and gas industry is going to fight the transition to a cleaner, less polluted economy every step of the way, on the ground, in local communities, where the rubber hits the road.

Big Oil — the wealthiest companies in the world, ideologically committed billionaires, and the Republican Party that does their bidding — has a lot of money to spend, with fewer and fewer restraints imposed by campaign finance law. (And a newly robust conservative majority on the Supreme Court, sure to further loosen what restraints remain.)

The only counterweight to this enormous financial advantage is people power — organized citizen resistance. But it takes an enormous amount of people power, and right now, the climate side of these fights is fragmented, siloed, and woefully underfunded.

If direct democracy holds any hope of overcoming the power of fossil fuel incumbents, the left is going to have to bring its full, coordinated, organized weight to bear in each one of these fights, as Big Oil does. Small, scrappy citizen groups, as much as we may romanticize them, simply aren’t equipped to win battles at this scale.

Original Source -> Big Oil is using brute financial force to kill 2 state sustainability initiatives

via The Conservative Brief

0 notes

Text

The battle for Hillcrest

Tippi McCullough and Ross Noland square off to represent perhaps the House's most progressive district.

On May 22, voters will decide between Tippi McCullough, a longtime teacher and activist, and Ross Noland, an attorney and nonprofit director, in a race to represent downtown and midtown Little Rock in the state legislature. Actually, only Democratic voters will decide the race, but in House District 33, which stretches across Little Rock's midsection, from Reservoir Road to the River Market, south of Riverdale and mostly to the north of Interstate 630, there's not much distinction between Democratic voters and all voters. It's perhaps the state's most reliably liberal district.

After serving three terms, Democratic Rep. Warwick Sabin announced last year he would not seek re-election, but would instead explore running for Little Rock mayor. The winner of the Democratic primary will win the November election by default; no Republican or Libertarian candidate filed to run.

At a debate sponsored by the Pulaski County Democratic Party held Monday at Philander Smith College, McCullough and Noland substantively agreed on all policy questions: Both oppose Governor Hutchinson's proposal to reduce income tax rates on the state's highest earners, think charter schools should not be able to grow unchecked, believe that public schools are underfunded, argue that the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences needs more state funding and support the preservation of War Memorial Park as green space.

McCullough and Noland live one street apart in Hillcrest, but their backgrounds and policy priorities separate them, each candidate said in an interview.

McCullough, 54, has taught English at Little Rock Central High School for the last four years. Before that, she spent 14 years at Mount St. Mary Academy, which fired her in 2013 for marrying her longtime partner, Pulaski County Deputy Prosecuting Attorney Barbara Mariani. The Catholic girls' school said McCullough had violated a morality clause in her contract, though according to McCullough, her relationship with Mariani was no secret at the school. The firing led to a public outcry; McCullough and Mariani traveled around the country sharing their story on behalf of the Human Rights Campaign's advocacy for LGBT rights.

The experience "opened my eyes a little bit" to politics, McCullough said. She became president of the Stonewall Democrats in 2014, which in turn got her more involved in state Democratic politics. It was a natural transition from LGBT advocate to political activist. "LGBT people are people — they have the same issues everyone else does" with housing, jobs and health care, she said. In January 2017, she became the chair of the Pulaski County Democratic Party. (She stepped back from active leadership during the campaign and plans to resume her duties after the election.)

On the campaign trail, McCullough likes to say, "I've lived in Little Rock for nearly 20 years, and I'm fortunate to live in Hillcrest, but I didn't grow up there." She was raised by a single mother in Hot Springs. She was the first in her family to get a college education, thanks, McCullough says, to her basketball skills, which landed her a scholarship at Ouachita Baptist University in Arkadelphia. After graduation, she got a job coaching basketball and teaching English in Kingston (Madison County) and later Mountain Pine (Garland County) and Newport. She was the first woman to be president of the Arkansas Basketball Coaches Association. (Asked in the debate Monday how she would govern in the minority party, she cited that leadership, saying the association looked a lot like the legislature, which drew laughs from the audience.)

Coaching and teaching all over the state makes it easy for her to relate to people, she said. She's witnessed the "struggles" of her students and their families, "whether it was because they were homeless or hungry or suffering abuse." That experience, along with her involvement in the Arkansas Education Association, which she said "strives to improve students' lives at school and also the teaching profession as a whole," gives her an edge in the campaign, she said. "Every door I knock on, when I ask them the most important issue to them, they say, 'Education.' "

McCullough is vice president of the Hillcrest Residents Association. When the Hillcrest Merchants Association considered shuttering the popular Hillcrest HarvestFest, she volunteered to step in to run the fest.

Noland, 37, is a lawyer who divides his time between his firm, specializing in environmental litigation, and serving as executive director of the Buffalo River Foundation, a nonprofit dedicated to cooperative conservation in the Buffalo River watershed. He cites his Arkansas bona fides on the campaign trail. He was born and raised in Little Rock and graduated from Central High School in 1999 as "Mr. Tiger Spirit." He received his undergraduate and law degrees from the University of Arkansas at Fayetteville, before completing a master's degree in environmental law at George Washington University in Washington, D.C. After working at a private firm in D.C., he returned to Little Rock to clerk for Pulaski County Circuit Judge Mary McGowan. Then he joined U.S. Sen. Blanche Lincoln's staff as legislative counsel to Senate Committee on Agriculture, Nutrition and Forestry, which Lincoln chaired. After she was defeated by John Boozman, Noland returned to Little Rock and worked primarily on environmental litigation for the McMath Woods law firm for five years before going into solo practice and taking on the leadership position with the Buffalo River Foundation.

Noland says his experience gives him the edge in the campaign. He's seen the inner workings of government, from his time at the U.S. Senate to working as an attorney in Little Rock and writing bills that have become law and rules that became regulations.

His knowledge of environmental issues also separates him from McCullough, he said. "There is no leader out on environmental issues down there. If there's one thing that affects us all — rich or poor, black or white, north or south of the interstate — it's the air that we breathe and the water we drink. To me, it's one of the most important issues facing the state and the nation right now, and I don't think we have enough emphasis on it. ... As far as what I can get done, I'm fully aware that I'm running to be a freshman in the lower house in the minority party."

But Noland said issues he's campaigning on have broad-based appeal. He wants to make renewable energy more accessible to the average person. "We need to make it easy for retail customers to deploy solar, whether it's through access to financing or making sure they get a fair price when they put energy back into the grid," he said. "There's a freedom association to producing your own energy" that Republicans should appreciate. He also said the playbook for state conservation could be used in passing other environmental measures in the legislature.

"We have a strong outdoor recreation movement in Arkansas. It's key for the environmental and conservation movement to tie what you like to do outdoors on the weekend to the fact that you need clean air and water to do it — whether it's duck hunting or floating or whatever." Outdoor activity is a "huge economic engine" throughout the state, he said.

Noland is married to Ali Noland; they have two children, the oldest of whom is in pre-K in the Little Rock School District. "The fundamental role of the legislature is to perform oversight of its executive agencies," he said. "We've got to get a plan to return to local control of the school board," he said. Expanding pre-K throughout the state is also one of his priorities.

Noland said he supports the Seventh Amendment right to a jury trial and strongly opposes Issue 1, the legislatively referred constitutional amendment that would limit the amount of compensation juries can provide for noneconomic damages, such as in injury or wrongful death cases.

After years of being a "policy person," Noland said he decided to get involved in politics because of the political climate. "The time to act is now. If you're not pissed off about what's going on out there now, you're not paying attention," he said.

The battle for Hillcrest

0 notes

Link

The latest report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) makes it vividly clear that averting catastrophic climate change means rapidly reducing the use of fossil fuels, getting as close to zero as possible, as soon as practicably possible. The US needs to fully decarbonize by mid-century or shortly thereafter.

Big Oil, at least with its public face, has acknowledged that reality and is supporting a revenue-neutral carbon tax in the US (one that, not incidentally, would shelter the industry from legal threats based on climate change). It is attempting to act, or at least to be seen as acting, as a reasonable partner in the federal climate effort.

Down at the state level, where media pays less attention? Not so much.

Take what’s happening in Washington and Colorado. In those states, citizens who are tired of waiting for their elected officials to act are resorting to direct democracy: with ballot initiatives, up for votes on November 6, that would directly take on fossil fuels. (Washington’s would put a price on carbon emissions; Colorado’s would radically reduce oil and gas drilling.)

Shutterstock