#how they all justify their actions — both socially moral and socially in-moral �� to themselves

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

tim drake would rather die than kill innocent people and tim drake killed hundreds of supervillain henchpeople with long-range detonation explosives that one time are two separate headcanons that, contrary to what the fandom discourse would have you believe, can actually coexist at the same time.

there’s even a psychologist term for it.

it’s called compartmentalization!

#let’s be honest#the entire batfamliy “stuffers” from this#and while that’s not something generally talked about#I just find the concept so interesting#how they all justify their actions — both socially moral and socially in-moral — to themselves#particularly how they all justify their actions to themselves in different ways#and for more evidence about their compartmentalization: there’s obviously the fact that they all have superhero and civilian identities too#also#this might need to be a separate post#but#the fandom’s perception of each member of the batfamily as individuals#often read more like they have bought into the characters’s “masks” they wear due to trauma#the “masks” being how the batfam are completely willing to be only perceived as one-thing#because that’s easier than being a real human#with blood and pain and fears and failures#they’d much rather be#the nice one#or the funny one#or the smart one#(etc. etc.)#dc#dc comics#dc characters#batman comics#batfam#the batfamily#tim drake#robin#robin dc#red robin

789 notes

·

View notes

Text

Digging Graves for your Morals; Or, The Ethical Problem of Outlawry

Hello, yes, I am here again. This one is shorter, I swear (it’s under four thousand words, even). If this is the first post from me you’re seeing, this is a follow-up to my prior essay posted here on the game The Coffin of Andy and Leyley, although it should be able to mostly stand alone.

At the end of my last essay, I touched on both the game’s nearly uncompromising moral scepticism and relativity, but I didn’t really dig into it. I outlined that the game only textually frames actions as ‘morally bad’ in the context of a morality set by the society and the world that has treated them as no better than farm animals raised for the slaughter. Well, I have a lot to say on the topic of ethics on the topic of The Coffin of Andy and Leyley, so buckle in, this one’s going to talk about the social contract, moral scepticism and everyone’s favourite topic: Mrs. Graves.

As usual, this was originally posted and formatted for on Sufficient Velocity and you can perhaps more easily read it there. Spoilers abound, and my content warning from last time still applies.

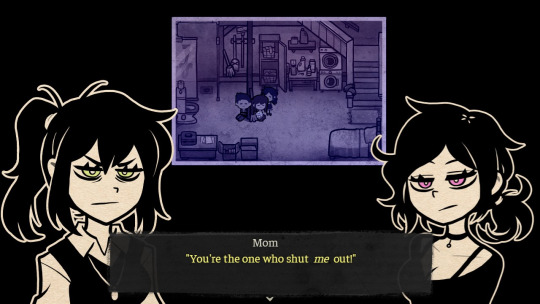

She’s not too hot on either ethics or her mother

The Meat of the Matter

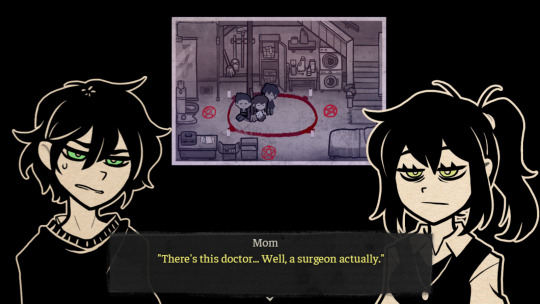

Since a lot of this is optional or otherwise missable information, let’s review the premise the game gives us. If you’re already aware of all of this, I apologise, it won’t take long.

First off the bat, the quarantine at the start of the game was a hoax-driven money-making scheme of which you can pick up more-or-less all the relevant details of. This is entirely missable and by the time it’s possible to discover, our protagonists have better things to dwell on and have dialogue about, so I’ll give you a summary of what you can deduce from reading the notes and thinking about it.

The quarantine is an organ harvesting operation, as per some documents you can discover in the wardens’ office. They entrap the residents, test their blood types and starve to death those they deem surplus to requirements — alternatively the starvation itself could be their method of ‘preparing the harvest’, there’s evidence in both directions and it hardly matters — harvesting the organs of the others for sale. As our protagonists are AB-typed, the ‘universal recipient’ or ‘most selfish blood type’, they’re some of the first on the chopping block.

If you read through the newspapers and the documents in Mr. Washing Machine’s car, you can discover that ultimately ToxiSoda are responsible, and a similar thing is happening in a different city under the guise of a ‘chemical leak’. Should you further investigate matters, you will find mentions of the ‘man behind it all’, the doctor, or the Surgeon, as the fandom have been referring to him — you may recall Mrs. Graves mentioned someone similar! Yeah, he’s the guy who runs ToxiSoda, who are themselves partners with the water company that faked the parasite outbreak in the first place.

It’s all a life insurance scam, apparently

How much the details of the operation matter is something open to interpretation — it might just be something for players to figure out and Episode 3 will not cover the Surgeon at all, or he might play a major part; it's not particularly relevant to this essay. What matters is that it happened at all — indeed, it’s fairly easy to justify Ashley and Andrew in everything they did in Episode 1 (flashbacks aside), arguing that if they’d made any other decisions they’d have died — an argument that the victims dug their own graves, even if the Graves siblings put them in them. How correct that is is a matter of debate, but that you can make the argument at all matters, and we’ll be returning to this later. In my last essay (and again in the introduction here), I made an analogy to farm animals, raised without love and for slaughter. Let’s put a pin in the ‘for slaughter’ part for now and take a look at the ‘without love’ part.

That’s right, it’s time to meet the parents.

As Andrew notes, there are significantly more compelling reasons for you to say that

They Fuck You Up, Your Mum & Dad

They really do.

Our charming protagonists are, as with many things depicted in this game, an exaggerated, almost farcical example of this phenomenon — one that’s just grounded enough to still feel very real, just like the siblings themselves.

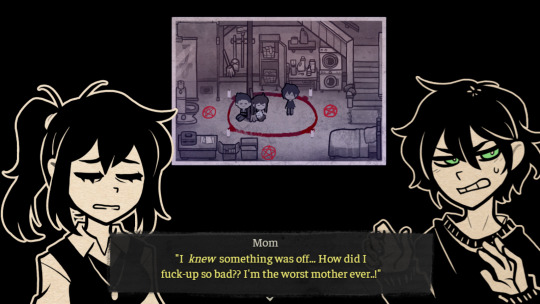

The late and lamentable Mrs. Graves is just the same: originally a teen mother, hopelessly out of depth with two difficult children — even if one was good at masking it — and an unreliable, emotionally unavailable (at least to their children) partner who can’t hold down a job, ends up foisting them off on each other and doing a Parental Negligence because she simply Cannot Cope. That’s the real part. The part where she gets paid off by an organ harvesting operation to leave them to die, that’s the borderline-farcical exaggeration that throws all the nooks and crannies of her character into sharp relief.

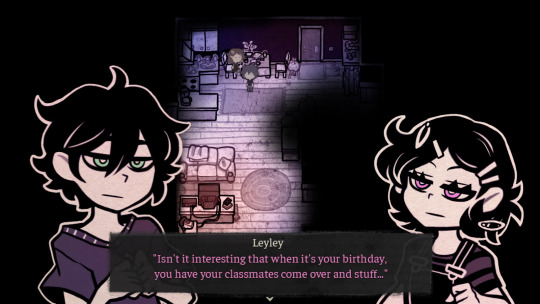

Mrs. Graves does not have a good relationship with either of her kids. Having self-admittedly fobbed the job of raising Ashley off on her son, to the degree that they did not even celebrate her birthday as kids, both of them hold differing degrees and types of resentment for her.

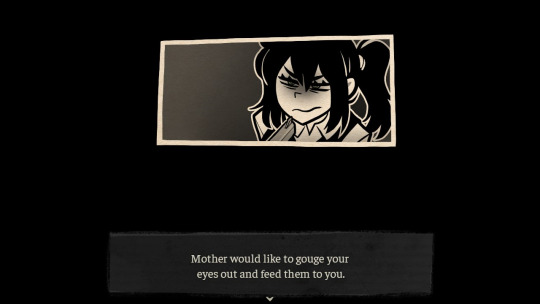

For Ashley, it’s hate — perhaps not quite so clear cut as that, as it’s her that calls for the eulogy and she shows some potential signs of discomfort while cleaning up her parents’ corpses, but by and large, it’s fairly simple and straightforward, as usual for Ashley. The sentiment is not exactly unreturned, either.

This brings Ashley’s heart great delight!

The most clear incident raising her from everyday ‘neglectful’ to ‘wow she wanted nothing to do with this kid’ is the optional ‘birthday cake’ scene, obtained by finding the present in Ashley’s first ‘transitory world’ dream, in which we see Ashley’s birthday and the founding of a lemon cupcake tradition between Leyley and Andy. She has received nothing from her family, notes that her ‘friends’ would say they were busy before she even told them the schedule and Andy takes her out to buy cupcakes with his pocket money.

This scene gets a callback in Andrew’s dream later. Just remember to Ask Nicely, rather than Kill Her.

Parents of the year, everyone.

So with Ashley it’s as straightforward and obvious as she herself is — she hates her mother, her mother hates her. With Andrew, as with Andrew himself, it’s a fair bit more complicated. His mother is a much more nuanced figure, who is believable in her role as an unfortunate teen parent who was trying her best. He has a degree of trust in her against, seemingly, his own good judgment In her conversation with Andrew, she acknowledges her fault in raising him and seemingly sincerely tries to offer him a ‘way out’, an olive branch.

I think many people have had relationships where they might say this

This scene in particular intrigues me, because she is acknowledging fault in a way that Andrew strictly avoids doing — and well, there’s nothing Andrew likes more than a good way to avoid acknowledging any fault of his own. With her dominant relationship over their father as a model for Andrew to draw comparisons to his own relationship with Ashley with, it’s no surprise that the narrative resonates with him to the point of ‘Accept’ being many people’s first completion.

Of course, that’s not all there is to it. There is a fascinating contrast with her later conversation with Ashley, where she — despite accusing Ashley of brainwashing Andrew — refers to Leyley and Andy as ‘two psychos’ and states that she always knew they were responsible for Nina’s death and that, implicitly, they owe her for not turning them in.

There's something about mother-daughter relationships here that I just do not have the time or reading to dig into, unfortunately.

Meanwhile, when Andrew interrogates her on her possession of their death certificates, she has… an interesting, plausible story about a life insurance scam and claims that she really did think they died in the fire, implicitly denying the claim that she sold them. It’s entirely possible that she’s describing the details of the ‘scam’ correctly — you can even buy that she genuinely does care for Andrew in some way, if not Ashley, but her claim about being an honest, grieving parent shocked at their deaths… doesn’t add up?

This is a very normal reaction to your supposedly dead children showing up in your house.

As Andrew himself notes after hearing her story, she’s full of shit. This gets into speculation, because there are a few ways to read this, but the most plausible ‘gist’ is that she and her partner were paid off in money and jobs to not raise a fuss — the surgeon she mentioned is almost certainly the founder of ToxiSoda, remember?

The overwhelming difference in presentation between how she speaks to Andrew and Ashley invites investigation — and when Andrew turns down her offer and tells her he isn’t interested in her offer in Decline, her reaction isn’t… despair, it’s shock — and well, there’s a good reason for that.

Why do you think she did it in the first place?

This is the happiest we see her

Well — it’s so she can finally fit into society. That white picket fence, that idyllic 1950s life — hell you can call it the American Dream. She wants that, or as close to it as she can get — the working-class teen mother, living in poverty, aspiring to the middle-class. It’s a very common, very real and very grounded motivation.

And to that end, she effectively sold off her children. It’s no wonder she can’t fathom why Andrew wouldn’t choose the same.

That’s the part that makes you think — just like the deaths in Episode 1, well- maybe the siblings are justified here, too. It’s a weaker argument, but it’s still one you can make under many common moral paradigms today — what goes around comes around, all that jazz. Just look at how awful she was to Ashley.

She’s finally found what she’s been striving for.

Here’s the thing, here’s the thing though — what, reasonably, could she have done? Andrew and Ashley briefly highlight this in conversation about Ashley’s ‘friends’ in Episode 1 — was she supposed to fight gunmen to try and break them out? Throw food to the balcony from four stories?

Moreover, as she herself says to Andrew… would anyone really have been able to do better than her in her position? She was seventeen when Ashley was born, living in poverty with a partner who couldn’t even remember Andrew’s name when he was a kid. Anyone would have had difficulty, let alone with these kids.

Her evils are — they’re not any deliberate action, but rather… prompted inaction. She didn’t have the emotional energy, resources or plain capability to properly parent her children, she didn’t have any solutions to their murder of Nina in a state so blatantly hostile to its underclass, she didn’t have a way to connect with Ashley and she took the money rather than fight a futile and likely suicidal battle against a corporation and its armed goons in a dystopian setting.

Ashley, notably, does not deny this.

Her sin is the one we’re all, I think, guilty of — that of not trying hard enough, that of inaction in the face of difficult tasks, of not standing up on principle because it’s just too much that day and you don’t have the spoons, you’ll do it tomorrow (no you won’t). It’s a petty, everyday kind of evil — that of not doing enough.

Is that enough to condemn her? Certainly, there’s a pretty manipulative read of her that likely has some truth to it — in the locked door in Ashley’s dream in ‘Decay’ you can discover that she has a ‘not-hatched’ tar soul — but consider that lens — the game won’t make up your mind for you, so you’ll need to choose that for yourself.

The dad is interesting in terms of negative space — but he’s mostly important in that he doesn’t matter, so I decided to not fit him in here. He has art, though — just no sprite, because, well, he’s never mattered to either sibling.

The Contract We Call Society

Right, it’s time to get a little bit Theoretical in here. Not much, but a little. Social contract theory is a complex topic with a lot of nuance, much of which I will be eliding in the name of not writing a twenty thousand word paper on semiotics, law, and anthropology, but the short analogy is… the idea that as long as you play by society’s rules, as long as you are a good citizen, a good person, the state, or the community, will take care of you.

In a number of ways, the harshest penalty levied by many historical states and legal codes was not death, but rather the criminal status of outlawry, a practice that’s cropped up a number of times in history — the practice of no longer being protected by the law. This meant one could be killed or worse with impunity — you were no longer protected by mob justice and, while overexaggerated as a term of reference, certain texts from Medieval England refer to outlaws as bearing a wolfshead, ‘for the wolf is a beast hated by all folk’. Never minding that wolves are actually delightful, this was a time when wolves were actively hunted and sold by people — and the same was intended to happen to outlaws. They were ‘fair targets’ as far as society was concerned, no longer to be treated as your fellow citizens.

This was the gravest punishment on the books, for most of these legal codes — something saved for those who had broken the social contract so completely that there could be no turning back (civil outlawry is… a bit different, that’s not the topic here). Among others, a modern critique of the concept is that it offers no incentive for improvement, no incentive to change or to cease harming society — if an outlaw has none of the social contract’s protections, what reason do they have to obey… any of the social contract? If that seems familiar, well, let me ask you this:

What if the state or community fails its end first? What responsibility does the innocent outlaw have to that contract?

It’s an interesting phrasing, that the world is better off.

It’s time to talk about the incest, and part of why it’s there. The cannibalism too, but that’s less impactful here. If you’ve seen me elsewhere, you might have seen me say that the incest is a load-bearing narrative pillar — in large part due to it being a critical facet of the siblings’ relationship, but in another large part due to it being an equally critical part of how the game uses taboo.

A taboo is in this context something that is considered repulsive and to be avoided by society. It’s a more complex term than that — you can also use it for certain sacred actions or utterances that are only permitted to certain people, for example — but that’s what it is here. Swearing, premarital sex, BDSM and murder are, approximately from weak to strong, some example taboos held in modern Anglospheric society.

Strong taboos are a staple of horror — they shock, they disgust, they draw people’s attention and it’s that last one that’s critical here. Incest is a very strong taboo — while I am absolutely not segueing into its historical context, the very well-established Westermarck effect gives it a certain timelessness and immunity to desensitisation that most other taboos don’t have — murder, to contrast, is a taboo we’re largely desensitised to in modern media and works of modern media have to put in actual work to make a murder seem horrifying — through atmosphere, cinematography, evocative prose etc.

And this is important because the use of taboo I’m covering in this essay is that the incest is used to invite judgment — it is so ingrained as a ‘wrong thing’ in people’s brains almost regardless of background that it forces the player to engage with the work morally. And that’s where the fun starts.

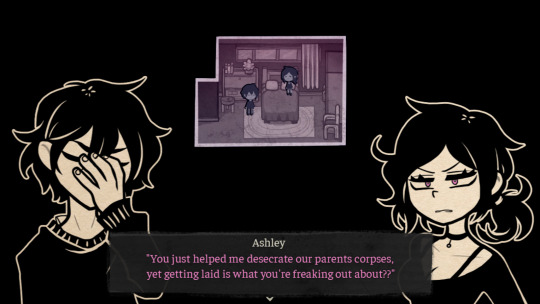

I’ve mentioned before, very briefly, about the juxtaposition of tone between the Burial & Decay endings, contrasting with the very monstrous difference in morality. Burial is remarkably light-hearted — they play around with the drain blockage, they joke about their mother’s personality and this is further exaggerated on the Love path, where Andrew is much more comfortable with casual contact and the two make a game out of how far they can throw their parents’ skulls, the humour is directly contrasted against their abhorrent actions.

I’ll be real Ashley is far more merciful than I, I’m shuddering at the thought of that gunk in my hair

In comparison, Decay is… bleak. I’ve seen it being referred to as being ‘emotionally sandblasted’ and, yeah I think that’s fair — it’s uncomfortable, it’s heavy and it’s just not fun. And this is the route in which, if you chose Trust into Accept, Andrew has bought into the narrative that his mother’s offered — that he can fit just fine into society if he wasn’t stuck, if not for Ashley — the route that ‘fits’ most closely to the social contract, to Andrew feeling the guilt that we think he should and hating the monsters that they’ve become, as the social contract deems them. Given the pains the game takes to attach the player to the protagonists, this normative moral ending is very easily interpreted as the bad ending.

And well, isn’t it?

Thing is, as mentioned above, the social contract has never held up its end for them. The game takes careful pains to point out to a viewer that they’ve never had the life that society promises people, so why do its moral standards apply?

The game invites you to judge the characters, and in the same motion, asks you from what principles you judge them, making a pretty good guess in that, like most people who haven’t spent a large amount of time navel-gazing and reading some very boring books by very dusty old men, they come from the society around you.

Love even has Ashley express this sentiment directly after the incestuous dream — she asks you — well, Andrew, but this is also something for the player to mull over — why this is what’s engaged your morality or sense of revulsion, rather than the desecration, cannibalism or murder.

Andrew and Ashley are both very funny and very fascinating in this scene.

And that’s the framing that it casts all of its own moral judgement in — even the ‘tar-soul’ aspect is… well, it’s unclear what it even means. Mrs. Graves was a ‘not-hatched’ tar soul, after all. Other than that, it’s society and the world being better off without them, rather than any kind of assertion of objective morality. Due to the present of ‘soul colour’, we’ll presumably see the game make some moral statements in Episode 3, but as it stands?

It’s nearly completely morally sceptical, in and of itself — it’s not interested in moral assertions or education, it’s interested in making you question your own morals. Deconstructive (not that kind), rather than dialectic, to be mildly pretentious.

It uses taboo and shock to invite moral judgement, but then uses tone, charm and our instinct to look for the happiest end for our blorbos to get you to recognise that these are principles you yourself brought into the game, rather than any it’s handed you.

To summarise: you’ve brought these principles in from society, but what do the siblings, the protagonists, the villains to the world, owe society? Enough that they should follow them? It failed them first, after all.

Closing Thoughts

This one is a bit less energetic than the last, tragically — my sleeping schedule is the stuff of nightmares recently, I love windy weather. Wait, no the opposite. Huge thank you to everyone who commented on the last one, you are the wind beneath my wings and the main reason I managed to get this out this week.

This essay is a bit more interpretative than my last one — certainly, there are alternative readings and I’ve been toying with the idea of deliberately taking a reading I don’t like very much and writing from that perspective as a demonstrative exercise recently — mostly that you shouldn’t just take my word for things!

Otherwise, if the last bit at the end seemed murky, I apologise — I did try to write a more detailed version, but firstly, it was three thousand words and secondly, I re-read it the next day and I could not understand what the fuck I was talking about. Personally, I blame Derrida — suffice to say that I strongly recommend playing through it with an eye towards considering culpability, morality and why you think certain characters are more or less forgivable than others, and for what deeds. See what you get out of it.

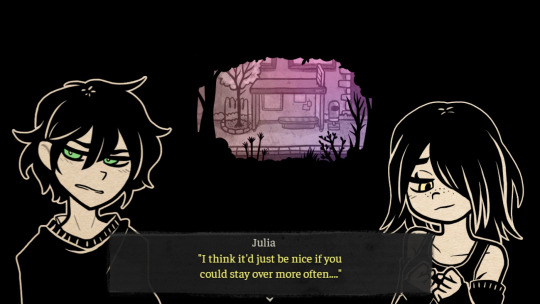

I managed to keep one particular thread open to wrap up with here — I try to keep speculation on Episode 3 content to a minimum in the main essays, but it should be fine here — you might have noticed that I refer to Episode 1 and Episode 2 being on something of a spectrum of justifiability, with the siblings’ actions being ‘more’ justifiable in Episode 1 and ‘less’ justifiable — but still justifiable if you try — in Episode 2.

To continue the thought of the happiest ending being the one in which they step the furthest away from common morality and to further jar the viewers’ sense of morality by contrasting societal morality and blorbo-oriented morality, Episode 3: Burial could continue this trend in having a major victim be someone who, well, has done nothing wrong and isn’t even guilty of bystander syndrome.

I wonder if there’s any good candidates, someone who’s sweet, harmless and will indisputably be an innocent victim…

…I’m sure she’ll be fine

#the coffin of andy and leyley#tcoaal#analysis#essay#ashley graves#andrew graves#mrs graves#nnnnot sure what the next topic will be#might do a deranged take on purpose#this one and the last one have been very grounded#I'll get to my asks tomorrow#probably#I've been busy sorry

472 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Bias of Charm: How Marauders Fans Justify Bullying and Overlook Class Dynamics in the Harry Potter Fandom

Fans of the Marauders frequently justify or downplay their bullying of Snape, often casting Snape as the villain to avoid confronting the darker implications of their heroes’ actions. This tendency reveals a problematic side of fandom, where fans prioritize the Marauders’ charm and charisma over the moral weight of their actions. Rather than acknowledging the classist and systemic nature of the bullying, fans often portray Snape as deserving of his treatment, turning him into a flat antagonist in order to shield the Marauders from criticism. This approach disregards the nuances of both Snape’s character and the social dynamics at play, simplifying a complex situation into a narrative where “cool, popular kids” rightfully victimize an “undesirable” outcast.

By villainizing Snape, fans avoid grappling with the uncomfortable reality that the Marauders, particularly James and Sirius, weaponized their privilege in a way that was deeply harmful. This fan perception reinforces the social hierarchies within the narrative itself, essentially suggesting that it’s acceptable to mistreat those who don’t fit the mold of wealth, looks, and popularity. For example, James is often defended as “just a teenager” or “a prankster,” while Snape’s own teenage flaws are held against him as evidence of inherent malice. This double standard reflects how class and charisma influence perceptions of morality, as fans are more willing to forgive or ignore the actions of characters they find relatable or attractive.

This selective empathy is problematic because it mirrors real-world attitudes that excuse harmful behavior based on social status. It also perpetuates harmful stereotypes by casting Snape, who comes from a disadvantaged background, as a natural antagonist whose suffering is somehow justified by his flaws. In doing so, the fandom misses an opportunity for deeper analysis of how class, power, and privilege affect behavior and relationships. Instead of acknowledging that Snape’s bitterness and resentment are largely products of his environment and experiences, fans often frame these traits as intrinsic, validating the Marauders’ treatment of him as somehow deserved.

The tendency to gloss over the Marauders’ flaws and project all moral blame onto Snape perpetuates a shallow understanding of the characters, effectively erasing the social commentary Rowling embedded within their interactions. This unwillingness to critically examine favorite characters reflects a broader issue within fandom culture, where uncomfortable truths about beloved characters are ignored in favor of an idealized, sanitized view. Consequently, Snape becomes a scapegoat, and the Marauders are preserved as untouchable heroes, depriving the narrative of its complexity and turning a nuanced story of prejudice, trauma, and class into a simple tale of “good vs. bad.”

Ultimately, this biased interpretation hinders meaningful engagement with the text and reinforces a mindset that excuses bullying when it comes from socially accepted figures. By failing to confront the class-based bullying Snape endured, fans inadvertently reinforce the same attitudes the Marauders themselves embodied, upholding a shallow, elitist perspective that undermines the moral depth of the story. This approach not only diminishes Snape’s character but also restricts the fandom’s capacity to engage with the story’s social critiques, resulting in a fandom culture that favors charm over accountability and surface-level narratives over meaningful reflection.

#severus snape#pro severus snape#pro snape#james potter#sirius black#marauders#severus snape fandom#harry potter#severus snape defense#harry potter meta#hp meta#marauders fandom#the marauders#marauders era#marauders fans

95 notes

·

View notes

Text

1. The Revolution Is a Relationship

[…] Something that worries me about social justice communities is that we tend to conceptualize “revolution” as a product, as a place and time that we expend all of our energy and anger to create – often without regard to the toll this takes on individuals and our relationships. [...] In our – often justified – anger and disappointment at the failure of ourselves and our communities to uphold the dream of revolution, we lash out. [...] What if revolution isn’t a product, some distant promised land, but the relationships that we have right now? What if revolution is, in addition to – not instead of – direct action and community organizing, the process of rupture and repair that happens when we fuck up and hold each other accountable and forgive?

2. The Oppressor Lives Within

[…] I’ve started to believe that I can’t engage in authentic activism, I can’t create positive change without recognizing and naming my own participation in the oppressive systems that I’m trying to undo. Coming from this position, I’m forced to have compassion for the people around me who I see also participating in oppression, even as I’m also angry at them. With compassion comes understanding, and with understanding comes belief in the possibility of change. When we become capable of holding that contradiction in our hearts – when we can be angry and compassionate at the same time, at ourselves as well as others – entirely new possibilities for healing and transformation emerge.

3. Accountability Starts in the Heart

[…] I often wonder how different things would look if it were more of a cultural norm to understand accountability as a practice that comes from within the individual, instead of a consequence that must be forced onto someone externally. What if we taught each other to honor the responsibility that comes with holding ourselves accountable, rather than seeing self-accountability as a shameful admission of guilt? What if we could have real conversations with each other about harm, in good faith? In a culture of indispensability, I cannot ignore someone when they tell me I have harmed them – they are precious to me, and I have to try to understand and respond accordingly. […]

4. Perpetrator/Survivor is a False Dichotomy

There is an intense moral dynamic in social justice culture that tends to separate people into binaries of “right” and “wrong.” […] “Perpetrators” are considered evil and unforgivable, while “survivors” are good and pure, yet denied agency to define themselves. Among the many problems of this dynamic is the fact that it obscures the complex reality that many people are both survivors and perpetrators of violence (though violence, of course, exists within a wide spectrum of behaviors). Within a culture of disposability – whether it be the criminal justice system of the state or community practices of exiling people – the perpetrator/survivor dichotomy is useful because it appears to make things easier. It helps us make decisions about who to punish and who to pity.

5. Punishment Isn’t Justice

[…] It isn’t inherently wrong to want someone who hurt you to feel the same pain – to want retribution, or even revenge. But as Schulman also writes, punishment is rarely, if ever, actually an instrument of justice – it is most often an expression of power over those with less. How often do we see the vastly wealthy or politically powerful punished for the enormous harms they do to marginalized communities? How often are marginalized individuals put in prison or killed for minor (or non-existent) offenses? As long as our conception of justice is based on the violent use of power, the powerful will remain unaccountable, while the powerless are scapegoated.

6. Nuance Isn’t an Excuse for Harm

[…] [I]ndispensability means that everyone – especially those have experienced harm – are precious and require justice. In other words, we cannot allow the fact that something is complicated or scary prevent us from trying to stop it. Trapped in the perpetrator/survivor dichotomy of understanding harm, it might seem like we have only two options: to ignore harm or to punish perpetrators. But in fact, there are often other strategies available. They involve taking anyone’s – everyone’s – expressions of pain seriously enough to ask hard questions and have tough conversations. They involve dedicating time and resources to ensuring that anyone who has been harmed has the support they need to heal.

7. Healing Is Both Rage and Forgiveness

If the revolution is a relationship, then the revolution must include room for both rage and forgiveness: We have to be able to tolerate the inevitability that we will be angry at one another, will commit harm against one another. When we are harmed, we must be allowed the space to rage. We need to be able to express the depth of our hurt, our hatred of those who hurt us and those who allowed it to happen – especially when those people are the ones we love. It is up to the community to hold and contain this rage – to hear and validate and give it space, while also preventing it from creating further harm. […]

8. Community Is the Answer

[…] Perhaps the reason we tend to recreate disposability culture and trauma responses over and over is because we are all, secretly, that frightened runaway kid, constantly searching for a home, but not really believing we can find one. Maybe we don’t create communities of true interdependence – of indispensability, of forever-family – because we are terrified of what will happen if we try. But I believe, have to believe, that true community is possible for me and for all of us. The truth is, we can’t keep going on the way we have been. We need each other, need to find each other, in order to survive. And I have faith that we can.

394 notes

·

View notes

Text

TERFs dni

“Mutual abuse” does not exist. Dynamics of abuse are fundamentally about a power imbalance in which the abuser consistently uses harm to gain and maintain power and control over their victim. It does not become “mutual abuse” when the victim responds with violence or harm.

I’ve seen that many of y’all are capable of understanding that a cop hitting a protestor is different from a protestor hitting a cop because there is a massive power dynamic that makes a cop able to act with impunity and places immense restrictions on the protestor.

I’ve also seen folks recognize that using harm to take maintain that power and reacting to harm inflicted on you with violence have a distinctly different moral weight/impact.

But you see that same shit play out in an abusive relationship and throw your analysis out the window.

The question to ask is not what individual actions everyone involved has done, it’s a question of where the power is. You cannot understand abuse and how it functions unless you start asking where the actual power is and until you learn how to see it.

Since some of y’all are clearly struggling with this I’m gonna help you out: the term “toxic relationship” exists for a reason. There are plenty of relationships in which the people are just shitty to each other. Not all bad relationships are abusive ones. Abuse is about POWER.

^^ that said: don’t assume that from an outsider’s perspective that you have the ability correctly and consistently determine that a relationship is toxic rather than abusive. Because folks defaulting to saying harm in a relationship is “just toxic” similarly silences many survivors. (source)

“Mutual abuse” is the adult version of a principal telling a kid defending themselves from a schoolyard bully, “Well, it’s really the second punch that starts the fight.” Utter bullshit. This false equivalence messaging sides with the oppressor, and tells weaker or oppressed people turn the other cheek and not to defend themselves. Unsurprisingly, this “both sides are equally guilty” narrative is most often trotted out in defense of white men, especially in cases of domestic abuse.

It reminds me of when I used to hear the old phrase, “Well, everyone’s a little bit racist” that was used to equate the justified rage of Black oppression with white supremacy. Again, the problem with this argument was denying the POWER imbalance. Black people absolutely can express prejudice against white people, but because it is white people who control the criminal justice system, Hollywood, social media platforms, banks and lending institutions, the education system, etc., the collective “prejudices” of Black people will never be the equivalent of white racism and anti-Blackness. If every Black person in America got pissed off at white people on next Tuesday, not one damn thing would change for white Americans. You wouldn’t see more white people missing out on job promotions, you wouldn’t see more white people getting stopped and frisked by the police, and you wouldn’t see more whites getting denied home loans or entrance into elite colleges. Nothing would change for them because they control all of those institutions.

It’s not precisely the same thing, but in both cases, dismissing or ignoring the POWER imbalance is exactly the same.

#amber heard#johnny depp#mutual abuse#false equivalencies#dv#domestic violence#darvo depp#darvo#power imbalances

77 notes

·

View notes

Text

saw across the spider verse finally and this is my first post of many to excise this conflict the movies of miles have left in me since the very first one:

the copaganda wasn't subtle the first time neither was it this time but it did surprise me that gwenvs dad implied he quit like telling us that maybe his morals cannot come from abiding a code he doesn't have a say in? and i think they planted the seeds with hobie too, like there's even the scenes that try to justify the cops existing in a spider story as staples of his myth, those things felt more like that, justification for still talking about them in relation to heroism, because honest to god the movie doesn't seem able to come up with examples of cops helping lmfao, did they even notice? like did the writers notice? but honestly with both hobie and that line from gwen's dad i had a glimmer of hope

but that keeps falling short when i have to look at jefferson, like in the comics his stints with the law are more a contract to his desire to be good to the people he loves, like a tool almost, the fact that the movies went a step further to make him loyal to it is profoundly disgusting specially when i look at how rio who was supposed to be the one most heroic to miles, a nurse, was reduced in favor of raising jefferson the cop to stardom, like fuck, that has always felt so superficial and trite for a spider man myth, but it used to be that the conflict was because it put into question the morality from the law as something incomplete and rigid and ultimately useless against the threats the heroes come against, which are representative of the society the heroes and all their ills are meant to embody

heroism is what these cops are meant to represent for the writers and animators like that's the issue, that's why we fuckers of color complain, because today right now, people and cops and professionals and people with power keep pretending that cops can be called heroes, that they can take up the mantle of one of the most precious parts of society which is communicating the morals of a time as if they could be the only ones that could in their hands the understanding of the myth of good and evil in the time they inhabit, but it's all a lie like are people this blind to themselves, they're just human, they're just fucking people like us, they can't hold nothing for shit because they're also people who have been told to use power as their life and truth, a hero is so many fucking things but he who holds all truths, he's not, often the hero shows us the journey to be able to inhabit, create, mold and be those truths, but also that we could inhabit the lies so easily, if the hero falls so do the people so does the nation, and cops want to be entrusted with that story but they don't see it, they don't that they're not asking like people or heroes but like gods like myths, and it's crazy that this world wants to keep pretending that when someone says they are a cop, as if they truly were it, they're but playing mockeries of human beings, because all they do is enforce power they do not understand, and just because this movie managed once again to try to put the cops against the spider scenes people are eating it? when the text it self could only give us good actions of the cops in relations to their kids and families? when the writers comfortably ignored the social impact of the story of spider this time around in favor of the personal conflict which ended up falling short for me and other fuckers of color because of how many fucking times they couldn't stay away from implying cops are just good people and not the bunch of fucking criminals the state has sanctioned as executors of its will specially against black and brown kids in the us like you have got to be disconnected from reality to be able to ignore all that frfrfrfr

it's just not the story of our times you know? that cops are do gooders... they can't literally be, they're meant to embody power, and power is just power too, it all depends on who wields it, which tells you what being a cop really is, and ofc the military and other things that have to defer to command to call themselves functional, they're naught but tools, extensions of the state, when it comes to exercising power in today's society is all about functionality and quality and maintaining a machine, and thus we got eugenics and racism and discrimination so that people can form themselves into tools to enforce systems of oppression to others so that wr can become, we call this all morality and capitalism and whiteness keep pretending there's only one way to be and define ourselves and what we learn, perverts all into becoming money and abuses to protect the power gives participants in our dehumanization, we have to consider the story of this world fr, that there are abuses in place today because of history that they're tied to skin, that they're tied to identity and the disparities represent our inability to compromise into making life fair and humane for all, those who are not deemed are those who are not picture perfect functions of the system, race usually comes tied to a perception of less humanity, of ableism, of being born as less because of it, do people not see it or are they just good st ignoring their own words?

it's insidious that the story keeps pretending that jefferson morales is able to stand for the entire police and on top of that they imply that that's what would happen with jefferson dead like rio didn't die in the comics and it just made miles want to do good like as much as i enjoyed the twist by the end it doesn't sit right with me but at the same time they sort of implied that it's all about the superhero, so like idk part of. me think there's actually a division in the writing room, and by the end what's given me hope for that story to maybe break was hobie and gwen's storylines, albeit gwen's a bit more ambiguous it feels close to what jefferson should represent how miles does things that jefferson finds conflict and how maybe he cant keep supporting power but i just don't know how many people understand that either, cops are a job, they just follow rules, how many times have people working companies or for a living have had to do horrible shit to themselves and others because we were taught to endure it, cops are the most advanced and finalized version of that able to mutilate themselves and kill others in service of power coated in a story made to make them feel good

like fuck is there any way to leave this clearer? miguel has created what is basically rick and morty's fucking citadel abd just as fascistic as that one bitch thinks he can control time and space because of his dark story, miles breaks away from that, so does hobie, so does gwen by the end, right now maybe i want to leave it clearer, for me, that the story is a disaster due to the implication that cops are just like masked vigilantes and that the only difference is the legality of the act, when we know, maybe mostly by those that inhabit a reality marginalized, that cops just maintain divisions that are meant to protect a status quo, the two lines the story followed should have been used to contrast different moralities, those enforced by power and those sought out from a place of kindness and that much i can tell fell flat for me because of that fucking contrast nowhere to be seen, what i hate right now is have to wait to the next movie because in my head i keep replaying hobie looking with pride and miles breaking apart miguel little bitch o'hara, and gwen's dad saying he quit, because it meant hurting his own daughter, and theres a ray of hope there but idk people need a reality check, cops are killers, cops are murderers, cops are your enemy because they make you one, you don't get to choose your role when you're in a situation with them, and the writers need to leave that clearer because otherwise it is truly off putting to have this movie like this right now when atlanta's fucking cop.city is looking to become a model of fascism everywhere on the fucking world like do i sound insane or hyperbolic? i don't think so, we know history i hope, what this movie has done with the cops and heroism and race is truly atrocious but there's hope if they can be knocked into sense and that starts with looking at reality from those whose faces are put onscreen for us to see ourselves like can we really not make better mirrors of ourselves that empty tools of the state in the forms of cops? like can we really not be better than a glorified pencil. pusher crunching people for the state? is that all heroes can be too? how depressing man....

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

Israel’s Historic Permanent Scar

Stephen Jay Morris

5/28/2024

©Scientific morality.

The polemics of morality can lead to moralistic fallacy. For example, Israel has the right to defend itself against terrorist attacks, so killing women and children is a defensive action and, as such, is justified. Well? Is it? Believe it or not, it is justified by fables in the First Testament. In that context, God is absolutely evil and bad tempered. He gives ultimatums like: ‘Would you show your loyalty to me by killing your baby boy?’ He floods the earth, causing a genocide, but saves animals. He condemns women because Adam ate the apple offered by Eve. Come on now! There are horror movies in which young kids are evil. What’s up with that shit?

What is it with innocence that Prime Minister Bennjamin Netanyahu finds so distasteful? Suppose the shoe was on the other foot and Hamas declared the Likud Party a terrorist group? How would they locate Likud Party members in a state with millions of people? So, Hamas starts bombing Israeli day care centers, schools, and hospitals. Why not? Doesn’t Palestine have a right to defend itself? You will find this type of sophistry with a shyster lawyer. This antisemitic stereotype of lawyers is what Bennjamin Netanyahu is perpetrating and it sets the Jews back 500 years!

Bennjamin Netanyahu doesn’t care about Israel or worldwide Jewry. He cares only about himself and his career as a Jewish dictator. Someone who is so heartless as not to shed a single tear for any Palestinian child or mother is a straight up sociopath! He is cold and calculating and speaks in a monotone voice, so you know we are dealing with a sick-in-the-head monster! He has his supporters and they are in the IDF. These monsters make videos of themselves taking the clothes and toys of dead Palestinians, putting them on and playing with them, laughing and mocking their victims’ pain and suffering, and post them all over social media!

America’s support is unconditional because President Biden stands absolutely and without question with Israel. Why? Since when are Revisionist Zionists Israel? Can you imagine if Christian Nationalists represented the USA? Would Canada stand with America? Maybe Biden doesn’t know a fake Israeli from a true Israeli? Does Biden stand with Judeo-Fascists? Bennjamin Netanyahu and the Likud Party is not Israel! Nor is MAGA America!

What Bennjamin Netanyahu has done with Israel is no different from what Jewish gangsters did in America the 1930’s, or Jewish landlords in 1950’s. He has placed a permanent scar on Israel’s history. The Gaza genocide will be known for countless generations to come. The videos of the reactionary settlers throwing humanitarian food and aid off flatbed trucks and doing a dance of the Hora is sickening! This is not a war. A war has bullets flying in both directions. This war launches bullets from only one.

I am fucking sick of self-righteous Chuds saying how wonderful Bennjamin Netanyahu is! He is a cold-hearted butcher and should be sitting in a prison cell. He is evidence that there is No God!

#stephenjaymorris#poets on tumblr#american politics#youtube#anarchism#baby boomers#anarchopunk#anarchocommunism#anti zionisim#war crimes#israel

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

I really don’t like the “Balance between Good and Evil” trope. Derivatives like “Balance between Light and Darkness” is good, because “Light” and “Dark” can be interpreted in multiple ways, giving virtuous and negative qualities to both. “Balance between Law and Chaos” is similarly good, which is me letting my SMT nerd out and OSR if half of those games didn’t just define “Law” as “Good”. But “Balance between Good and Evil” always sounded really dumb, like the “what if we put half of the babies into woodchippers” meme but unironic and it’s also the premise of an entire work’s story and metaphysics.

Part of this is because, while “Law and Chaos” or “Light and Dark” or “Yin and Yang” have some room for interpretation (Is Law a peaceful community led by a just ruler or is it theocracy devoid of free will? Is Chaos a chill anarchist paradise or is it eternal war and space monsters?), “Good” and “Evil” are self-defined and very uncomplicated. Good is Good. Evil is Evil. This is fundamentally pretty cringe for numerous reasons. One, “Good” and “Evil” being cosmic forces implies that there is an objective morality in this universe. I have never in my life seen “objective morality” handled in a way that wasn’t really weird or shitty (it’s very apparent that early D&D considers “kill the orc babies so they don’t grow up evil” to be the morally correct, Good option, or at least Gygax did). Two, our opposing forces are “Good” and “Evil”. You couldn’t be more on-the-nose unless you outright have the good guys refer to themselves as “the good guys” and the bad guys refer to themselves as “the bad guys” in-universe. And third, combining elements of the previous two, it’s very easy to slip into self-justifying behavior or protagonist-centered morality with a set-up like this. “When they slaughter our soldiers, it’s abhorrent. When we wipe out the enemy troops, it’s heroic. When they torture our men, that’s vile. When we used enhanced interrogation techniques on their lieutenants, we’re just getting work done. When they try to kill all the elves, it’s genocide. When we kill all the orcs, it’s Good Triumphing Over Evil.”

But while “Good” and “Evil” is a bad dichotomy, let’s discuss the middle ground, Neutral. Neutral in regards to Law and Chaos means freedom and order, everyone has free will, but everyone follows the social contract and treats each other well. Neutral is the point of Yin and Yang, because neither are bad or good and it’s unbalance that’s destructive. But what does Neutral mean in regards to Good and Evil? Does it mean saving half of the orphans from the burning building and collapsing the roof on whoever’s left inside? Sending soldiers to save one city from Goblin Attack but then doing your best to prevent anyone from saving the second city because we’ve filled up our life-saving quota today? Petting a kitty but then punting a puppy over a fence? Being Good but also being kind of a grumpy prick about it? What are its motives, its foundations? “Does Good acts and balances them out with Evil acts or vice versa” describes either a mentally unwell person or an Evil one, the same way “randomly switches between being Lawful and being Chaotic” actually just describes Chaotic. Furthermore, “Good is Good, but Evil has to exist or flourish to some extent because uhhhhhhhhhhhh“ is stupid no matter how you slice it. Even putting aside the fact that this sounds EXACTLY like something an Evil person would say while they’re currently losing, allowing the world to become an objectively worse place to live in out of some sense of fairness or neutrality-for-its-own-sake is heinous. There’s no reason, really, and to be Neutral in this regard is to allow the world to become objectively worse through action or inaction, which is indistinguishable from Evil.

You could make political commentary out of this! No, don’t.

Finally, and in addition to the above, part of what makes Law vs. Chaos so cool is that you can side with any of Law, Neutral, or Chaos, and it can be good or it can be bad. Law is security and tyranny. Chaos is freedom and eternal conquest. Neutral is balance but it delays the inevitable cosmic clash of Law vs. Chaos. Good/Neutral/Evil is completely asymmetrical. A world of Evil would just be a horrible nightmare world, if not the end of the world. A world of Neutral has evil in it for poorly explained reasons. Meanwhile there’s no downsides to a world of Good. “But if Evil is eliminated, then Good will turn on itself in the belief that people aren’t being Good enough” I hear you say, to which I retort that persecuting other people for petty reasons isn’t Good, it’s Evil. “But Evil had to be contained, if it’s destroyed then a greater Evil will take its place” isn’t a problem with Good either, it’s a problem of Evil reappearing. The worst you can say about Good is that it always has to defend itself against the forces of Evil, but acting like Good taking over will lead to a dystopia because Good taken too far is just as bad as Evil is some “I’m 14 and this is deep” stuff.

20 notes

·

View notes

Note

tbc, i'm not trying to justify abuse. if this comes off like that, just delete this pls so i don't trigger other folks but. how can i justify judging my abuser by all their abusive actions towards me and others when i don't judge everyone else for the shitty things they've done all the time?

how is it okay for me to go "ok i don't want anything to do with you bc of xyz you've done over the years" when i wouldn't want ppl looking at me and constantly going "oh it's fucked up so many times over the years, what a loser" or some shit.

like. is that me holding them to a standard i shouldn't? its not like i bring up different shit they've done all the time, even if it bothers me, but i'd hate it if someone was constantly judging me for shit i've messed up on [though, tbc, i have not abused anyone] throughout my life. is it different bc i've apologized n changed wherever and whenever i could in situations that i fucked up and they haven't? or is that me making excuses for holding them to a higher standard i don't do to everyone else?

sorry if this doesn't make sense. im just feeling a bit conflicted rn. - mc

Hey there ❤️ I understand what you mean, don't worry.

I think there's a difference between judging someone and not wanting them in your life.

When you judge someone for the bad things they've done, that can serve a purpose. For example, it can help you understand where you draw the line on what things you think are okay to do. It can help you reflect on which things you would want someone to apologise for. But judging a person can also be unfair—like if, for example, you judge someone solely based off of something wrong they did many years ago, or like if you keep a list of how many times a person has made a mistake so you can hold it against them. That is, indeed, holding someone to an unfair standard by demanding moral perfection from them.

Deciding you don't want anything to do with another person serves a different purpose. Sometimes it's about maintaining a social image, or about clashing personalities. But, in the case of abuse, it's about keeping yourself safe from a person who has hurt you, or who you know could hurt you because they've already hurt someone else. It's about prioritising your safety and well-being by setting and enforcing boundaries.

You can do both things at once (judge someone for being an abuser, and cut someone out for being an abuser), but they're not the same thing. And I do think "I don't want people to judge me for my past mistakes" and "I don't want this abusive person in my life" can absolutely coexist.

Ultimately, you always have a right to decide who you do and don't want to have in your life, for any reason. Yes, there are people out there who only want to surround themselves with people who they deem have perfectly clean moral slates. Personally, I wouldn't give my time of day to those people. But there is plenty of middle ground between that, and giving an infinite amount of chances to an abuser on the off chance you might be unfair to them if you don't.

You don't have to justify wanting to cut someone out of your life. It's your right. They'll get other chances at relationships where they'll be able to prove they've changed, if they indeed have. You don't have to be the one to give them that chance. It's your right to prioritise your own boundaries, safety, and peace of mind.

I hope that helps. Sending a virtual hug ❤️

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

alicent is positioned as an antagonist to rhaenyra, because that is her narrative role in the story, but many viewers chose to interpret this as her being in the wrong and/or a villain. however, there is nothing inherently moral about being a protagonist or an antagonist, they are just lenses through which stories can be conveyed.

we are used to stories in which the protagonists are the "good guys", but you can write smth from the perspective of a morally-bankrupt character who paints themselves as a wronged victim, all the while being absolutely not justified in pulling their shit.

asoiaf is especially rife with these kinds of POVs and fans seem to fall for it every single time. tyrion is not a hero in any way, for example, but bc he is a POV-character, people act like he is right in nearly all his actions. jaime is generally despised by readers until they reach book 3 and he receives POV-chapters, then he suddenly becomes a fan favourite. the same happened in the show, his popularity sky-rocketed after S3 when he got more screen time; before that, he was an evil lannister. the vile deeds and thoughts jaime and tyrion commit are subsequently swept under the rug, because their prolonged exposure to the audience has proven them to be charismatic and funny, so all (or most) is forgiven.

making rhaenyra the protagonist and not alicent is not bad, it's just a narrative choice. either focus has its advantages and its drawbacks. they are not divided by such a strong dichotomy of hero/villain, they are merely two characters opposing each other. both see the other as villainous, but neither is wholly correct in their interpretation. they both have legitimate grievances with the other caused by a breakdown in trust and communication, aggravated by the systemic expectations placed on them by their social and political roles. it is also worth pointing out that a pseudo-medieval society is not the best place to handle mental health issues and interpersonal relationships in a measured and 100% fair way. most people don't even manage to do this in real life with all the information and the developments in the field of psychology at our disposal.

so, yes, probably if they were more honest with each other and explained themselves better, this conflict never would have happened. but they literally don't know how. they don't have the language, the concepts or the resources to be so insightful.

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Coping Mechanisms in MDZS

TLDR: Explaining the JC debate from a psychological perspective. Its all about coping mechanisms.

CW: SH, Trauma

*For context, I am a psychology student (nerd) & wanted to understand why people see the same characters differently. I personally like JC & can appreciate why he acts the way he does but I can also appreciate why so many people think he's an asshole. Interpretation is up to the reader, so think whatever you want. I just thought it was an interesting topic :)

I also know there is a million different things that affect people's interpretations of characters but I thought it was an cool theory*

I keep seeing all of this fighting in the canon JC tag and I thinks its super interesting the way that people interpret characters so differently after consuming the exact same book/show. I am sure that everybody has their own reasons for what they believe either way.

Now most characters in MDZS are both objectively good and bad, like they all believe they are doing the right thing based on their own moral compass/circumstances but that means they often have to sacrifice others to serve their own ends. I mean nobody wins in war. However, I think part of the reason that people like or don't like certain characters comes down to the way that they express themselves/coping mechanisms.

Characters like LWJ & LXC literally abandon their duties as leaders of the Lans, abandon their families & engage in self-harming behaviours. But they are pretty universally well-liked both in the story & in the fandom. I am not bashing these characters, I quite like them actually. But I am bringing them up because they use different, but still not great, coping mechanisms to deal with their trauma.

Then we compare this to characters like JC & JL. They are aggressive, can be violent & have public emotional outbursts. Also not great coping mechanisms.

But one set of characters is praised & one set is criticized, both by people within the story & fandom. Why? (Well one of the reasons anyway). The Lan Brothers internalize their emotions whilst JC & JL externalise them.

"Internalising behaviours are directed inwards and include fearfulness, social withdrawal and anxiety, while externalising behaviours are directed outwards and include physical aggression, disobedience and substance abuse" (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

There are many studies that have shown that their is social stigma directed towards externalising behaviours. I mean they can be quite antisocial and, by definition, affect everyone around (external to) the person.

However, that doesn't mean that internalising behaviours are inherently better. As I previously mentioned, the Lan brothers both engage in behaviour that negatively impacts themselves and their community. But because their negative emotions, and subsequent behaviours, are directed towards punishing themselves, they are viewed less critically. There is less of an obvious social impact to their behaviours and so, as social creatures, we inherently view them as less problematic.

But here comes the truly interesting part:

If their JC & JL's behaviours are more stigmatised by society, why some people still like them? Well, in part, it comes down to an individual's own behaviours. Those who also externalise their emotions, have less stigma (& probably more empathy) for those who also externalise their emotions. It's hard to understand someone else's actions when you would never consider acting the same way.

Now does this justify JC & JL actions? No.

Does this make any of these characters reactions to trauma less valid than the other? Also no.

But can I understand why people hate characters like this? Absolutely.

Every character in MDZS goes through some level of trauma. There is no therapists and few resources to support them through it, so yeah they are kinda messed up by it all and don't really healthily cope with anything.

If you want to read into this a little further (or see how I came to this conclusion), check out:

Donati, G., Meaburn, E., & Dumontheila, I. (2021). Internalising and externalising in early adolescence predict later executive function, not the other way around: a cross-lagged panel analysis. Cognition & Emotion, 35(5), 986–998. Doi: https://10.1080/02699931.2021.1918644

Lau, A. S., Guo, S., Tsai, W., Nguyen, J., Nguyen, H. T., Ngo, V., & Weiss, B. (2016). Adolescents’ stigma attitudes toward internalizing and externalizing disorders: Cultural influences and implications for distress manifestations. Clinical Psychological Science, 4(4), 704���717. doi: https://10.1177/2167702616646314

If you are affected by anything in this post & need support, check out this link to find mental health resources in your area: https://www.helpguide.org/articles/therapy-medication/directory-of-international-mental-health-helplines.htm

#jiang cheng#canon jiang cheng#anti jiang cheng#lan wanji#mdzs#mxtx mdzs#mdzs lwj#the untamed#cql#psychology#psychoanalysis#not coping well#trauma coping#trauma#stigma#i spent so long on this

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

A must-read for anyone who played Girls' Monachopsis. I fear this visual novel will be mostly overlooked due to its short runtime but it will burrow its way into your mind and your heart and nest there if you allow it

In watching the discourse around Girls' Monachopsis unfold I made the observation that there seem to be two categories of reviews for the game:

Camp A: mostly trans women who almost immediately became evangelical about the game and rushed to social media to tell everyone about it

Camp B: a small amount of critics who complained about the writing style, story pacing, and the "romanticization of abuse" in the game

I find it interesting that both camps came to wildly different conclusions about the same elements of the game. Camp A views the writing style as a convention that adds to the story's immersion, while Camp B writes it off as laziness. Camp B thinks the ending left too much unresolved, Camp A appreciates the uncertainty for its familiarity.

It is just another case of a piece of art steeped in layers of cultural context breaching containment. We've seen this happen before with other cultures and niche communities in the past, this isn't really new. I do think there is one thing worth lingering on, though.

I read a post that basically called Monachopsis a game for "white trans femcels" and I honestly cackled a little bit considering that a black trans woman was heavily involved in the making of the game. It feels like "white trans femcels" or some other variant is just something people say when they mean "mentally ill trans women." This is already getting pretty long so I won't waste time explaining the problem here. There's the implication there that "media made for mentally ill trans women has less (if any) value," which is a self-indicting belief when you put it next to the overwhelmingly positive reception the visual novel has received from that very demographic who clearly is not used to seeing themselves represented in media in such a raw and unsanitized way. I think it is wholly unfair to say that any demographic does not deserve to feel seen in media or have media made specifically for them. We all deserve to feel seen, we all deserve to feel understood, and I think it's fairly obvious how the game's themes are relevant here.

The alternative option is alienation, and alienation is always a recipe for disaster. Generally speaking, no one isolated has ever come to any optimistic or generally positive conclusions about the answers to life's many questions. Social alienation tends to bring out the worst in people, and often when it does many of us like to pretend that such a thing could never happen to us. Many of us might like to believe that we are immune to the socially and morally stunting effects of prolonged social isolation, and more importantly that we ourselves are incapable of doing harm.

I think this piece is especially important because it highlights an uncomfortable truth for the average person. Olivia never fully reckoning with the gravity of her actions, combined with Thistle forgiving her way too easily, is a disturbingly accurate portrayal of abuse that may slip under the radar because most people hold a very specific mental image of what abuse looks like. Some people can use this mental image to justify the "subtle" ways that they may engage in abusive behavior, but most people just use it as a way to distance themselves from any perceived capacity to do harm and thus absolve themselves of any need for self-reflection. I think the mantra "anyone is capable of doing harm, even me," is a hard thing to internalize for many people. I think it's even harder to add "even someone they care about. ESPECIALLY someone they care about." We don't want to think about it, but keeping the truth out of sight and out of mind doesn't prevent harm from being done.

Lastly, ostracizing and demonizing groups of people for traits that are out of their control is bound to create more problems in the long run. If we fail to think critically, those problems can look like a vindication of the decision to isolate those people. I can use the stigmatization of neurodivergent people (and I don't just mean autism, I'm talking about BPD and other personality disorders) as an example of this. Queer people who are "too weird," people who find enjoyment in taboo kinks whether as a way of coping with trauma or whatever other reason. It shouldn't have to be justified either way. If two adults lay down clear boundaries and communicate effectively, the activities they consent to is no one else's business besides any other parties they decide to include. Two consenting adult lesbians calling one another "sister" should not make people as rabid as it does. However, when we ostracize queer and neurodivergent people who do not fit our sanitized view of what those things mean, we run the risk of banishing them into spaces that are actually abusive. Sometimes the institutions that we create for ourselves in response to a society that has largely abandoned us can be just as poisonous as the very society we're trying to shelter ourselves from. Your queer community, if left without the tools to facilitate healthy dynamics, can be exploitative. It can be self-sabotaging. It can be just as toxic as the outside world. Sometimes our own institutions fail us too. I feel like this idea is expressed brilliantly in Malcatras' Maiden in addition to Monachopsis. Oftentimes they fail us while trying to do their very best to give us what we need. On an interpersonal level, our partners can do the same. We can also fail our partners while trying to do our very best. Anyone who thinks otherwise is more dangerous than anyone who works to keep that in mind. It is that very line of thinking, "I am incapable of doing harm, I don't have to worry about hurting anyone because I am not a bad person," that increases the possibility of someone getting hurt.

Wrote down some thoughts about Girls' Monachopsis development. Sincere thank you to weird freaks for enjoying this game. https://lunaticker.itch.io/girls-monachopsis/devlog/809599/girls-monachopsis-developer-ramblings

251 notes

·

View notes

Text

The View from Below - Family

It will come as no surprise to anyone that Ishgard’s recent history has been largely consumed by a variety of conflicts. The other City-states have had their warlike periods, whether driven by the actions of Garlimald or solely by an avaricious need to expand into lands that belong to other people in the belief that it more fairly belongs to you. Few kingdoms take the warlike martial virtues to heart like the Ishgardians, nor do they pursue them with such a single-minded devotion.

All such civilizations like their stories of wars and heroes, and often spend as much time documenting them as fighting them. The hero’s virtue is defined as much by how well known his or her deeds might be as by the deeds themselves. The Lords are reserved and refined, the knights heedlessly bold, and the Templars devotedly dour, but all hire scribes as their personal finances permit. What good is it, after all, to be the pinnacle of humility if it is not widely known just how humble you truly are?

For all that, even the devoted historian of Ishgard would not be faulted for not knowing of Moreau’s rebellion. Few that were not directly involved have a reason to care about a minor noble house rising up against its proper liege-lord, fighting a dirty war, before eventually being defeated. This is doubly so when you find that the rebellion was finally put down in 1572, the year the Calamity came to Ishgard and froze the life and hearts of most who lived there.

The scribes being busy with more pressing matters, it was left to those who did the fighting to documents their own deeds to a land that was for once more worried about having enough food to survive than any knightly virtues. Their writings say much more than the normal professional sanitized propaganda ever could.

Being no historian, I will summarize the details of the rebellion itself. Event he summarized tale is long though, and not without its own moral turns.

The records show that House Moreau had its lands foreclosed upon by House Harcourt for some great offence against feudal obligations, perhaps backed by charges of cowardice or any other social structure offence that serves mostly to offend the hearer. House Moreau appealed, and due to court politics, bribes, or perhaps the general tendency of nobility to not care about anyone of even a marginally lesser station to themselves, their appeals were denied and they were cast out of lands that had been theirs for generations.

This accomplished however, Lord Harcourt discovered that like the glutton that chokes on a chunk of meat greedily bitten off but too large to swallow, that his aggression would bring more woe to him than favor. The four Moreau siblings retreated to the hills briefly, before starting a rebellion that was as much as gratuitous demolition of everything they could find as it was an attempt to change social structures.

No mere raiders, their driven and justified crusade absorbed all who had complaint with any aspect of the rank-based society that had ever done them wrong, and they became something like an army. Initially denounced as a rabble, they still chewed up House Harcourt’s men-at-arms, knights, and estates. Ishgard responded eventually with some Army soldiers, and during the height of the conflict even Temple Knights were involved. The Moreau forces took on anyone who opposed them, paying no attention to rank or family.

Finally in a battle so pitched and vicious that few would have believed civilized people could descend to such a level of violence, the eldest of the Moreau brothers and the youngest sister were wounded and captured. The eldest brother then held the House Moreau family title by primogeniture. The sister, who had only seen sixteen summers, had equal to any of her brothers proven herself not a woman to be trifled with. Attempting to warn others of the price of rebellion, they were both subjected to tortures that would have been out of place in a far more brutal age, followed an execution so appalling that even its use as an example could only be seen as an ignoble substitute for justice.

For a time, that sufficed to handle the rebellion. Lacking the eldest’s clear leadership, the rag-tag army mostly dispersed and for a time there was a heavily policed peace in the land.

Then the killings started.

No longer an open revolution, what remained of House Moreau eschewed armies and pitched battles and instead took up a campaign of terror. Any who would dare to take up a manor in House Moreau’s prior lands were likely to awaken initially with their fields burned and their livestock poisoned. Those who remained despite these violent warnings would be found weeks later slaughtered in their beds, with little regard given to guilt, innocence, or age. It was as if a goal was no longer in mind, save that all who walked on the land must bleed.

The armies of Ishgard and its Temple Knights were again called upon, fumbling their initial attempts to deal with what was essentially a murder spree rather than a revolution they deployed as best they could, hoping for an opportunity to strike back against an elusive foe that refused to take the field against them.

The revolt, or whatever it had become at this point, came to a head one night with an attack on a manor house where Lord Harcourt and most of his family were sleeping. Guarded as it was, the house was a hard target, but the swift, organized attack succeeded nonetheless. When all was over the only living heir to the Harcourt title was a child barely old enough to walk, and she only remained alive as she was in another location at the time of the attack.

Given the bloody nature of this affront, pursuit was immediate and the elezen racing after the remaining raiders followed them to an isolated cave complex. The air was growing colder as the full repercussion of The Calamity, an event occurring far away and beyond any of the combatant’s considerations, began to take hold. As they descended into the cave complex the knights could not help but feel it as a change not just in their life, but to life in general.

The resulting battle was one of grappling fights in the darkness with short blades and sudden deaths. The defenders had the advantage of knowing the terrain and having no reason to give or expect any quarter. The attackers had equipment and numbers on their side, along with the knowledge that victory here might end a war that had gone beyond anything any sane person would have expected or wanted.

The final claustrophobic battle found several Temple Knights facing off against the two surviving Moreau brothers and a third warrior than none of them knew. The two brothers fought well enough but were no match for dedicated and experienced temple knights. The third warrior fought like a voidspawn possessed by a more powerful and enraged voidspawn. Fighting on after enduring what any observer would consider mortal wounds, his final kill was to bare-handedly choke the life out of a celebrated temple night while five other temple knights stabbed him in a desperate attempt to end his life. When the light finally died in his eyes, he had still managed to stab another knight twice with his own dagger. His corpse lying on the ground still looked angry and none of the remaining knights would go near it until it was cold.

It was a victory, but the price paid for it was entirely out of proportion with the results achieved. It wasn’t war. It wasn’t even battle. It was murder compounding on the costs of earlier murders, but executed on a grand scale.

The survivors of the battle wrote of their experiences in the hopes that when the world again made sense a scribe could come explain what they had experienced. Only an incomplete judgement was to come, since from the perspective of most Ishgardians the world has yet to really make sense again.