#greek-mythology-lover

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

Deidamia has so much angst potential

Yes, she does!

Deidamia was just a girl who was most likely sheltered, considering her father only had daughters. Her mother is never present in the myths, I wouldn't be surprised if her mother was either dead or not a present figure. She probably spent her days without many worries, having a princess education and then spending the day having fun with her sisters (as, for example, Philostratus describes). And then she had feelings for this new girl Phyrra, and she probably felt horrible about it because it was definitely not well regarded (something similar to the poem attributed to Bion of Smyrna). But the girl wasn't even a girl, and so Deidamia was in love with someone she didn't really know as much as she thought she did. And they were two very young people without proper supervision and now she's pregnant (Deidamia even took a while to realize this in Euripides' version), but she's just a girl and this child isn't even a child of the marriage. And now she's being forced to grow up fast, because she has to be the mother of this unplanned child. And not only that, but the father is leaving because glory is more important to him than her or their child. Achilles will become a man through the glory of war, she will become a woman through motherhood. And they're trapped in these gender roles and they will never see each other again because his destiny is to die in Troy.

She raises this child as a single mother, although at least she has support (father, sisters, maybe Thetis). We never really get her point of view…how is she viewed because of this? In some versions, Achilles marries her, but in others he doesn't. How is she viewed because she's a princess who got pregnant before marriage by a boy who didn't even marry her and who will never come back? At first, did people even believe the story that the father was the famous prophesied son of a goddess? Phyrrus is so sweet, playing with the shepherds' children, having fun with his innocent toys and he will never be like his father, a boy who gave up the opportunity of a home for the opportunity of war (inspired by Philostratus and Quintus of Smyrna). But then the news that Achilles has died comes and Deidamia is mourning, but she is mourning a person she hasn't seen in years. A person she last saw as a boy, who now that he is dead is a man. Maybe her memories of him don't even match up with what he is like now, but she will never get to know that. She doesn't even have much time to mourn, because soon the same men who took Achilles are demanding her son. They took the man who was supposed to be her husband, and now they're taking her son. And no matter how much she or Lycomedes try to stop them, Phyrrus is too seduced by following the ghost of a father he never knew and who his mother probably doesn't even know anymore. And then her son goes away, and perhaps like his father he will not return. Like his father he will die young in a foreign land because the seductive glow of glory has taken over his senses.

But he doesn't die in a foreign land like his father, he is alive. But he isn't Phyrrus, he is Neoptolemus. He is no longer the child who played with toys and shepherds' children, he is the person who chased the elderly king of Troy into a temple of Zeus and killed him without mercy or respect for the gods. He is alive, yes, but Deidamia doesn't really have her son back. And so either we don't know Deidamia's fate or, as in Pseudo-Apollodorus' version, she is married to Helenus. She is then married to this man whose home was destroyed by both Achilles and Neoptolemus. And maybe she loves Helenus, but she also loves Achilles and Neoptolemus. And how can she deal with that? How can she love Achilles and still mourn him, if the person who was in Skyros no longer has the personality of the person who died in Troy? How can she be happy that her little boy has returned, if he is not even her little boy anymore? At least, not in personality. And how can she rejoice that Neoptolemus is alive, if for that Helenus had to lose his home and the people he loved?

And then Neoptolemus is dead, and she is sad. At the same time, she cannot want Helenus to share this grief. He has a right not to feel this way. And Andromache arrives in Epirus and Deidamia has to face directly the consequences of what Neoptolemus did, while thinking about how Achilles must have done similar things. And Andromache and Helenus have a connection that Deidamia will never understand, she can never truly know what it's like to be in their situation. She can only learn to face the fact that you loving someone doesn't make them inherently good to others. Helenus is taken by the presence of Apollo when he prophesies and she just has to learn to deal with the presence of this god, the same god who killed her son and her son's father. But, having lived with Helenus and Andromache, can she really find their deaths entirely unjust? She's still sad, of course, but can she really throw her hands up to the heavens and scream that it's injustice?

In a way, I think Deidamia is a good representation of what it was like to be a woman, although it is more specifically the reality of a princess. She has to deal with being an innocent girl, she has to deal with thinking about the possibility of liking another girl, she has to deal with the idea of sneaking around with a boy, she has to deal with an unplanned pregnancy, she has to deal with being abandoned by the man who was supposed to be her husband, she has to raise her son without a husband while constantly thinking that her son's father is going to die, she has to find out that her son's father really is dead, she has to watch her son go to the same fate, she has to deal with the anxiety that he doesn't come back, she has to deal with the relief of seeing her son again and the loss of him not being the same anymore, she has to deal with the consequences of the actions of the men she loves on the lives of other people she has grown to love. And most of this happens while she is on the island, looking at the sea and thinking that this is the same sea that Achilles and Neoptolemus set out on for a distant land. At least, that's how I interpret her situation.

She has SO much potential, but people ignore her potential. Most of the time, Deidamia is just used to say something about Achilles and Patroclus' relationship. It's really sad.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

love elizabeth s.

#original poem#original quote#love elizabeth s#writeblr#writers of tumblr#writblr#writblur#quotes#my poem#poetry#short poem#sylvia plath#dark acadamia quotes#love poetry#dead poets society#virginia woolf#poem of the day#spilled ink#spilled poem#love poems#love quote#book lovers#books#booklr#reading#greek mythology#mythology and folklore#poetry community#poetry corner#aesthetic

14K notes

·

View notes

Text

Sorry, not sorry but I see this too often and it bothers me :)

Before people get mad: Notice how I put “Me and Penelope fans” there? I know there's others. this ain't about you <3

edit: This is about how people in the fandom prioritize Odysseus and Telemachus (and even Diomedes, who is not in the Odyssey) despite the Odyssey also being HER story as well. I've seen many fics about Odysseus and Telemachus in their youth, and never really seen that for Penelope.

#penelope of ithaca#penelope#penelope odyssey#odyssey#the odyssey#odypen#epic penelope#epic the musical#Mad rambles#shot by odysseus#sighs#tagamemnon#greek mythology#Mad memes#I've noticed this mostly with Epic but even Tagamemnon fans are like this too. ;~;#will probably reblog this later with more to say on it but yeh :/ it's like genuinely sad for me.#like people will go on about how in history “Men only saw women as wives and babymakers” and then...Write women as only wives#and babymakers :') clearly she doesn't have anything outside of that going on for her does she?#People throw out canon for fanon all the time for other characters/plots but you can't do that for Penelope? Why? Why is that?#like for being “Odysseus lovers” He would HATE y'all for not giving a shit about her#You think the “Wifeman” will tolarate people not caring about his wife?

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

legend has it that the young witch circe and the once beautiful nymph scylla shared a complicated past...

#art#cirscylla#that's the ship name i like for them best anyway#circe#scylla#greek mythology#welcome to my greek mythos yuri#DOOMED YURI#circylla#epic the musical#do i even tag it as that? i think i should cuz epic is the reason im so into greek mythos#jorge said we might get a spinoff about their backstory and im insane over that#i know it's probably going to be about how circe loved that one guy but still a girl can dream#this is them but younger! before circe turns scylla into the horrific man-eating monster that even poseiden fears#there's just so much potential here#consider a younger and much warier circe landing on the island for the first time after being outcasted by her family for her magic#and she meets scylla there who back then is a much happier and playful person#enemies to lovers to enemies again#i don't know if they ever make it to lovers or if they were only an almost#they're about to have the worst breakup in greek history#im rambling in tags MY BAD

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

Apollo and his lovers pt. 1 ✨️💕

Lovers: Cyrene, Rhoeo, Hyacinthus, Admetus

Hopefully I will be able to post pt. 2 this month

#my back is killing me#lovers of apollo#apollo#Cyrene#Hyacinthus#rhoeo#admetus#greek myth art#greek gods#greek heroes#greek mythology#my art

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

So I’m a huge Achilles and Patroclus shipper

And I love them

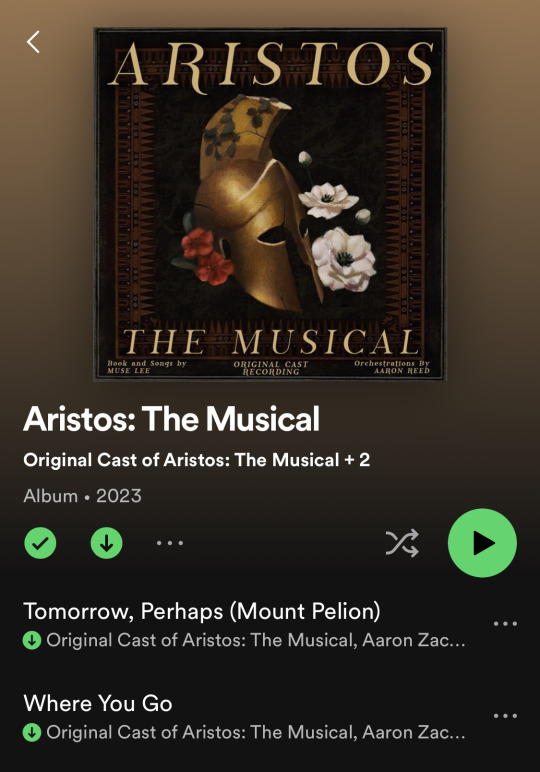

And recently, I found a musical about these two

It’s called: Aristos: The Musical

It is really good. I’m in tears when I’m listening to it.

It surprised me that how little people knows about this brilliant musical.

It is completed, and have 18 songs.

I highly recommend this to anyone who loves Achilles and Patroclus or just simply interested in greek myth.

Whether you’re a fan of the iliad or the song of Achilles, I’m sure you’ll love this musical.

#the song of achilles#tsoa#tsoa achilles#Aristos: The Musical#Patroclus#achilles#achilles x patroclus#ancient greek#greek mythology#greek myth#musical#recommend#musical recs#the iliad#patrochilles#song of Achilles#madeline miller#gays#gay lovers#Greek gays#hades game#hades#aristos the musical

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

“He saw darkness in her beauty and she saw beauty in his darkness.”

— about Hades and Persephone

#hades#persephone#ancient greek mythology#greek mythology#greek gods#greek tumblr#greek quotes#love language#in love#lovers#love story#love quotes#love#true love#foryou#tumblrpost#source: tumblr#quotes#literature#quoteoftheday#poems and poetry#poetry#beautiful quote#romance

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

"Zeus and Ganymede" (0001)

(The Queer Affair of Zeus Series)

#ganymede#zeus#male lovers#men loving men#gay love story#greek mythology#greek myths#long haired men#long hair#gay redhead#ai men#ai generated#ai artwork#ai art community#gay ai art#gay art#gay romance#art direction#fashion illustration#queer romance#male form#male figure#male art#homo art#homoerotic

468 notes

·

View notes

Text

I think I'm going to start drawing Apollo's children because I love them and they don't have enough appreciation.

So here is some Idmon and Aristaeus for the soul!

And some happy family bonus (they don't know that one of them is going to die)

#aristaeus#idmon#apollo#cyrene#apollo x cyrene#greek gods#greek mythology#toa apollo#apollo toa#toa#trials of apollo#art#They are my tragic babies#I know that canonically in pj Apollo does not have immortal lovers#so Aristaeus lose is brother when he go to te Argo and later lose is mother because he is inmortal

355 notes

·

View notes

Text

Terrible Fic Idea #92: Percy/Apollo, but make it The Trojan War

Into every fandom, a time travel fic must fall - or in this case a second one, because I somehow got to thinking about the delightful PJO trope of Percy being thrown back in time to The Trojan War and realized that doing so misses out on a fantastic opportunity.

Or: What if post-TOA Percy Jackson and Apollo time travel to shortly before The Trojan War?

Just imagine it:

Everything follows canon through TOA, with one exception: rather than struggle to catch up in the mortal world following the Second Gigantomachy, Percy elects to stay at Camp Half-Blood. There he can homeschool at his own place with programs tailored towards ADHD children and still visit his family on the weekends - and not get into any more ridiculous situations in the mortal world when one of the gods kidnaps him or sends him on a quest to find their sneakers.

This, naturally, stresses his relationship with Annabeth - who, now that she's no longer living at camp full time, calls it the easy way out. But Percy is tired and struggling in mortal high school where everyone thinks he's a delinquent idiot when another option exists seems foolish. Percy and Annabeth break up and drift apart.

Enter Apollo, fresh from his latest stint as a mortal. He's trying to do his best by his children, which includes popping by camp as often as he can get away with - which in turn means spending a lot of time with Percy, who at this point is unofficially running CHB because it's not like Dionysus or even Chiron have done a brilliant job of it in recent times.

(First aid, strategy, and mythology classes are made mandatory. Percy personally ensures every demigod knows enough about self-defense to be able to survive long enough to run away or for help to arrive. Bullying is cracked down on so hard that it's this, not Percy's generally parental nature, that has people calling him Camp Mom.)

Percy and Apollo become friendly. Enough so that some of Apollo's kids assume they're dating and keeping it on the down-low so as not to draw Zeus' ire. Or Poseidon's. Or anyone else's. It's on one of their not-dates that they're yeeted into the past, without warning or explanation.

And so 19-year-old Percy Jackson and post-TOA Apollo find themselves in Ancient Greece c. 1220 BCE, roughly thirty-five years before the destruction of Troy.

The time travel is immediately obvious, as Apollo becomes the closest thing a god might experience to being high the moment they land in the past - being a powerful god in modern times is nothing like being a powerful god at the height of his power in ancient times. It's overwhelming (and somewhat alarming from Percy's POV, but kind of funny in retrospect.)

The specific date is harder to determine, but made clear when Hermes shows up and starts going on about you'll never believe what father's done now: he seduced the Spartan queen as a swan and she's laid an egg. Hera is furious - especially as they're saying the girl that hatched from it is the most beautiful in the world, even though she's only a few days old. It's nuts. By the way, where have you been? You missed the last two council meetings. Do you want Dad to punish you?

Apollo at this stage is very high. He's also been USTing over Percy for quite some time and is worried what the gods of this era might do to Percy without divine protection (smiting or seduction, it's all on the table). But mostly he's very high, and so to keep Percy close and safe he declares he's been off having the dirtiest of dirty weekends with his latest lover and that Hermes' presence is ruining the mood. So if he would kindly leave, please and thank you, he'd really rather get back to it without an audience.

This, naturally, is a surprise to Percy, but he rolls with it because 1) he doesn't have any better ideas on how to get rid of Ancient Greek Hermes so they can figure out what the hades is going on and 2) he's been USTing over Apollo ever since he recovered enough from Tartarus to start feeling attraction again.

Fueled by mutual UST, they put together a cover story that should hold the next time a god with too much prurient interest shows: Percy is now Prince Persē of Gadir - a Phoenician colony that will grow into the future Cadiz - well past the edge of the Greek world at this stage but not beyond belief for Poseidon to have visited, as it's obvious who his father is. They claim his mother is the King of Gadir's youngest sister and as such Persē had a royal upbringing, but was far enough down the line of succession that he was free to chose to sail east and explore his father's homeland. Apollo caught sight of him on his journey, one thing led to another, and here they are.

(Are there easier, more sensible cover stories? Possibly. But the UST refuses to let them consider any of them now that a fake relationship is on the table.)

Deciding what to do about The Trojan War is much harder. On the one hand, it's a lot of senseless death and destruction. On the other, without it we don't get The Iliad and The Odyssey - two of the most influential works of literature in western civilization - and Aeneas doesn't go off to Italy (leading to the founding of Rome, which would change the history of western civilization a lot). In the end, they decide to let the war happen but do their best to mitigate the worst parts of it.

And so Percy goes off and becomes a hero of Ancient Greece while pretending to be in a relationship with Apollo.

This stage of things is filed with angst from both parties, as both Percy and Apollo want a real relationship with each other but think they're abusing the other's trust by eagerly faking their relationship. There's a lot of PDA, a lot of feelings, and limited communication. It goes on for quite a while and would probably exasperate quite a few people if everyone in the know didn't think they were already in a relationship.

It's also filled with modern day Percy being confronted by realties of life in Ancient Greece. It's not just mortals knowing about - and interacting with - the gods: it's everything. It's food and clothes and language and culture and housing and travel. He can play a lot off it as being a traveler from the edge of the known world, but some of it has him asking Apollo if he's being rick rolled.

Apollo, meanwhile, is having troubles of his own. He is not the god he used to be and it's hard pretending otherwise. He tries to walk the line of doing enough to be believable and holding back enough not to despise himself, but it's a fine line, he fails often, and he spends a not insignificant amount of time worried he's backsliding.

And so it goes until 7-year-old Helen of Troy is kidnapped by Theseus to be his wife.

This, naturally, does not fly with Percy, who by this time has built up something of a reputation as a hero. He teams up with the Dioscuri to rescue Helen.

One would think this would earn him Zeus' favor. It doesn't. Instead, Zeus sends monsters to harry him for refusing to let Castor and Pollux take Helen's captors' loved ones captive and raze Aphidna for Theseus' crime. Percy manages to hold his own for quite a while but eventually, exhausted from the near-constant fighting, is gored and left for dead by the reformed Minotaur.

...and when Apollo arrives, frantic, to heal him, Percy ascends instead, becoming the greek version of Saint Sebastian - a minor god of heroes, strength in the face of adversity, and athleticism; sort of halfway between Hercules and Chiron.

Then and only then do Percy and Apollo finally get their act together, confessing to each other how much they care for the other and how much they don't want this to be fake any longer.

History proceeds apace - albeit with Persē being a second immortal trainer of heroes.

24 years after their arrival in the past, 16 years after Percy's ascension, The Trojan War begins. Despite their best efforts, there's only so much they can do - war is war and gods are gods. They are able to stop some of the worst excesses on both sides, but in the end Apollo still sends the plague that causes Agamemnon to take Briseis for his own, which caused Achilles' departure from the field, Patroclus' death, &c - not because Apollo was trying to maintain the timeline, but because in the instant he sent it he was angry and reverted to his old ways.

Troy falls...

...but when Zeus tries to use this as an excuse to ban gods from interacting with their demigod children, Apollo is able to say that's a bit extreme isn't it? with enough backing from the rest of the council that Zeus is forced to amend his ruling so that the gods are only allowed to freely visit their children on the "cross quarter days" that fall between each solstice and equinox (1 February, 1 May, 1 August, and 1 November).

This changes everything and nothing.

Time continues its inevitable march. Greece has its golden age before being conquered by Rome, which splits apart under its own weight and forms several smaller countries, which eventually spread their cultures around the world...

Apollo and Percy are there for it all. Persē is a minor figure in mythology, but never forgotten. He is ever-present in Apollo's temples - though the Church will later try to rewrite their myth so that they were merely sworn fighting partners, rather than lovers who eventually had a quite lovely wedding on Olympus (and then, at Poseidon's insistence, an even bigger ceremony on Atlantis). Percy takes over day-to-day operations of CHB from practically the moment the Trojan War ends.

...and so Persē is there the day Sally Jackson tries to get her son to camp, and is able to intervene when the Minotaur attacks on their border. He's able to meet her and her young son, Perseus ("Mom named me after you and the guy that killed Medusa since you're the only two heroes to have happy endings!"), and guide him through the trials that come with being a child of prophecy.

One day that Percy will hand Luke - who was never happy with the limited attention the gods were allowed to give their children - a cursed dagger so that Kronos can be defeated. That child will be offered godhood, turn it down, and go on to have a happy life with his eventual wife, Annabeth. He will never have his memories erased and be sent to Camp Jupiter. Gaia will not rise until long after that Percy's grandchildren are dead, and Zeus will not be quite so bullheaded when the proof of it is brought before him. That Second Gigantomachy is swift, well-coordinated, and fought without another Greek/Roman war brewing in the background.

And when they finally arrive at the day Apollo and Percy were originally sent back in time, Percy admits that while he is happy some version of him was better prepared for the war he was asked to fight in and allowed his peace afterward, he would change nothing about his own life, for it brought him to Apollo. The sunrise the next morning - on the first morning of the rest of their lives - is particularly spectacular.

Bonuses include:

Gaslighting Poseidon into believing that he's met Percy before the first time they're introduced. ("What do you mean you don't remember me, Father? You were present when I came of age! You gifted me this trident! Have I displeased you in some way?") It's an absolute masterclass that eventually manages to convince Poseidon that, yes, of course he knows Percy - and, maybe, he should check in on all his other demigod children to make sure he's not missed someone. (Two. He lost track of two of the others. Maybe he should be more careful about siring children in the future.) Apollo practically has to stuff his fist in his mouth to keep from laughing.

As much historical accuracy as can be crammed into the Percy trying to make sense of Ancient Greece chapters as possible. Think Of a Linear Circle - Part III by flamethrower levels of historical research. As much as can be shoehorned in without bogging down the plot.

Percy and Dionysus bonding over their mutual dislike of Theseus, though Percy generally gets along with his other half-siblings, especially the ones who come to camp young enough to keep from getting big heads over being the children of Poseidon.

Though Percy adores all the children in Cabin 7 (most of whom are born via blessing this time around), he and Apollo have at least one child of their own - maybe a demigod born before Percy's ascension to sell their fake relationship? Maybe a minor god who's later attributed a different parentage by mortals? Dealer's choice on details.

It never being made clear who, or what, or how, Percy and Apollo were sent into the past. All of Percy's oddities are attributed to him being foreign or formerly mortal, all of Apollo's to the fact that he's in love with someone who didn't die before their first anniversary, and no one ever guesses time travel is responsible for their eccentricities. Or that time travel was ever an option.

And that's all I have. As always, feel free to adopt, just link back if you ever decide to do anything with it.

More PJO Ideas | More Terrible Fic Ideas

#plot bunny#fic ideas#percy jackson#percy jackson and the olympians#heros of olympus#trials of apollo#pjo#hoo#toa#riordanverse#time travel#apollo#percy x apollo#perpollo#fake relationship#trojan war#greek gods#greek mythology#mutal pining#unrequited love#requited love#camp half blood#ancient greece#ancient greek mythology#god percy#idiots in love#idiots to lovers

205 notes

·

View notes

Note

What does your version of Achilles do to Troilus?

It took me ages to answer, sorry! But, well, here's the answer! And not for you, but for some person who decides to read this… I'm not an academic lol take this as purely a reader's opinion.

GREEK TEXTUAL SOURCES

The oldest textual source we have on the subject is Homer, who honestly doesn't give many details. In Book 24 of The Iliad, Troilus is counted among Priam's dead sons. He is still killed by Achilles, but we don't have details of how, although in this version Troilus is a warrior. Here, he isn’t Apollo's son and there is also no mention of a sexual context. In Caroline Alexander's translation, Priam says:

He spoke, and drove the men off with his staff; and they went out before the old man’s urgency. And to his own sons he shouted rebuke, railing at Helenos and Paris and brilliant Agathon and Pammon and Antiphonos and Polites of the war cry and Deïphobos and Hippothoös, too, and noble Dios. To these nine, the old man, shouting his threats, gave orders: “Make haste, worthless children, my disgraces. I would the pack of you together had been slain by the swift ship instead of Hector. Woe is me, fated utterly, since I sired the best sons in broad Troy, but I say not one of them is left, Mestor the godlike and Troilos the chariot fighter and Hector, who was a god among men, nor did he seem to be the son of mortal man, but of a god. War destroyed these men, and all these things of shame are left, the liars and dancers, and heroes of the dance floor, snatchers of lambs and kids in their own land. Will you all not prepare a wagon for me at once, and place all these things in it, so that we can go upon our way?”

The Homeric scholia, written many years later and so the commentator probably knew more versions than Homer, gave more details about this death. It’s mentioned that Sophocles presented a version in which Troilus was ambushed by Achilles while exercising his horses near Thymbraion and was murdered (he’s talking about the lost play Troilus). Furthermore, the scholiast commented on the tendency of later authors to present Troilus as a boy (about age), but the scholiast interprets that Homer didn’t write Troilus as a boy. In Alan Sommerstein's translation:

Scholia to Iliad 24.257: (T) On the basis of this passage Sophocles in Troilus says that he [Troilus] was ambushed by Achilles when exercising his horses near the Thymbraion, and killed. One may infer [from the Homeric text] that … Troilus was more than a boy, since he is listed among the leading warriors. (A) “Troilus the chariot-fighter”: note that on the basis of his being called a “chariot-fighter” later authors had him pursued [by Achilles] when riding a horse. And they [or some] suppose him to be a boy, but Homer by means of this epithet presents him as a grown man, since no one who is not is called a horse-fighter.

In The Cypria, attributed to Stasinus of Cyprus, Achilles apparently kills Troilus before taking Briseis as a prize, something that happened in the early years of the Trojan War. Although what we have of The Cypria are fragments from other authors and not the entire epic, it still doesn't change the fact that the author who tells of Troilus' death at no point felt the need to specify that Troilus was sexually assaulted. Without sufficient evidence to prove otherwise at this point, I’ll assume that in The Cypria he was murdered, but not sexually assaulted. In H.G. Evelyn-White's translation:

The Achaeans next desire to return home, but are restrained by Achilles, who afterwards drives off the cattle of Aeneas, and sacks Lyrnessus and Pedasus and many of the neighbouring cities, and kills Troilus. Patroclus carries away Lycaon to Lemnos and sells him as a slave, and out of the spoils Achilles receives Briseis as a prize, and Agamemnon Chryseis.

In the “Epic Cycle Fragments” edition, which includes The Cypria, The Aethiopis, The Little Iliad, The Sack of Illium, Nostoi and The Telegony, only The Cypria mentions Troilus and, unfortunately, his parentage isn’t mentioned. I don’t know if his father is Priam or Apollo here. Since he doesn’t appear in the summaries/fragments of any of the other epics, I also don’t know if his parentage was mentioned in any of them. This is kind of sad because I think it would be interesting to know.

By the way, to make this clear, I've seen some people question where this idea that Achilles had sexual interest in Troilus came from. Well, in terms of written sources, I think the one that is mainly used for this argument is Lycophron's Alexandra. This poem tells the prophecies of the Trojan princess Cassandra, who is in a prophetic trance and describes the fate of all those involved in the Trojan War while alluding to previous events. At one point, in A.W. Mair's translation, Cassandra laments:

Ay! me, for they fair-fostered flower, too, I groan, O lion whelp, sweet darling of thy kindred, who didst smite with fiery charm of shafts the fierce dragon and seize for a little loveless while in unescapable noose him that was smitten, thyself unwounded by thy victim: thou shalt forfeit thy head and stain thy father’s altar-tomb with thy blood.

It’s a somewhat enigmatic passage, although it’s easy to identify that it’s in fact Troilus because of the last part. Apollo, in some versions (but not all and not even the oldest), is the father of Troilus. Troilus, in many visual representations, is shown as having been decapitated by Achilles, who holds his head in his hands. Furthermore, Alexandra is also, if I’m not mistaken, the oldest source on record to link the death of Achilles by Apollo with the death of Troilus by Achilles. This text received a scholia from the Byzantine Ioannis Tzetzes, who explained:

Alas, alas, I groan, alas, alas, I groan" and your fresh and well-nurtured age, my brother Troilus, "O cub" and most royal offspring, delightful entanglement of the brothers who, having wounded Achilles with the erotic arrow of your beauty, that is, having attracted him so as to fall in love with you, you not having fallen in love with him "beheaded" and your head cut off in the tomb and temple of Apollo by Achilles who fell in love with you and in the beheading "you will stain" the temple with blood. For they say that "alas, alas, I groan" Achilles, having fallen in love with Troilus, the son of Priam, and pursuing him was about to catch him, but he took refuge in the temple of Thymbraean Apollo. But Achilles, forcing him to come out since he did not obey, approached and killed him on the altar. Whom, they say, Apollo also avenged there and prepared for Achilles to be killed. Troilus was said to be by nature the son of Apollo, but by law of Priam. And "wild dragon" Achilles. And these indeed so babble about Troilus but I know this Troilus and having a deep voice and dark-skinned. I do not know, however, if the Thessalian Achilles was so erotic as to even fall in love with those of deeper voice and much older than this; for Troilus was young and beautiful but dark-skinned and deep-voiced and unworthy of Achilles' love. But after the killing of Memnon, having left Troy, he encounters Achilles and is killed by him and there was great mourning in Troy for him like for Hector. "Fire-bearing" but erotic because such passion is hot by nature. The mind; whoever wounded Achilles with your love "the one who was struck" that is, Achilles. But "O cub" "delightful" or dearest of the brothers: for they say that Troilus and Cassandra were twins.

Although there is a comment about Troilus being “unworthy of Achilles’s love” this is clearly Tzetzes’s personal opinion. In the end, it doesn’t change the fact that Tzetzes, as a schoalist, was clearly familiar with the version in which Troilus was attacked in part for sexual reasons. The name of the scholia, if you want to look it up, is Ad Lycophronem. The poem Alexandra subverts the character of Achilles, as it’s intended to emphasize the sympathetic aspects of the Trojans since it happens from Cassandra’s point of view. Achilles, being an very famous Achaean symbol, is the main target of subversions such as the way Lycophron tells the Skyros episode, a version that doesn’t match any other. However, Achilles’ interest in Troilus doesn’t seem to be a subversion of Lycophron. This is because there are other older sources, more specifically visual sources, that are often ignored. I’ll discuss these later. Tzetzes also seems to know versions in which Troilus was a warrior, as in other part he says that he was better than Deiphobus in war.

In Fabulae, attributed to the Roman Hyginus, there are Greek myths being presented to a Roman audience. The author lists Troilus among the sons of Priam, but there is no further comment on this and there is no mention of Apollo's involvement. There is therefore no reason to suppose that Fabulae sees Troilus as a son of Apollo; here he is the son of Priam. He is also listed among the dead princes, with Achilles being named as his murderer/killer. However, there are no details. So all we know is that Achilles at some point murdered/killed Troilus, one of Priam's sons. Again, there is no mention of sexual violence. In Mary Grant's translation:

SONS AND DAUGHTERS OF PRIAM TO THE NUMBER OF LV: Hector, Deiphobus, Cebriones, Polydorus, Helenus, Alexander, Hipposidus, Antinous, Agathon, Dius, Mestor, Lysides, Polymedon, Ascanius, Chirodamas, Evagoras, Dryops, Astynomus, Polymelus, Laodice, Ethionome, Phegea, Henicea, Demnosia, Cassandra, Philomela, Polites, Troilus, Palaemon, Brissonius, Gorgythion, Protodamas, Aretus, Dolon, Chromius, Eresus, Chrysolaus, Demosthea, Doryclus, Hippasus, Hyperochus, Lysianassa, Iliona, Nereis, Evander, Proneos, Archemachus, Ilagus, Axion, Binates, Hippothous, Deiopites, Medusa, Hero, Creusa.

THOSE WHO KILLED PRINCES: Apollo [killed] Achilles under the guise of Alexander. Hector, Protesilaus, and likewise Antilochus. Agenor, Elephenor, and likewise Clonius. Deiphobus, Ascalaphus, and likewise Antonous. Ajax [killed] Hippodamus, and likewise Chromius. Agamemnon, Iphidamas, and likewise Glaucus. Locrian Ajax, Gargasus, and likewise Gavius. Diomedes, Dolon and likewise Rhesus. Eurypylus [killed] Nireus, and likewise Machaon. Sarpedon, Tlepolemus, and likewise Antiphus. Achilles, Troilus. Menelaus, Deiphobus. Achilles [killed] Astynomus, and likewise Pylaemenes. Neoptolemus, Priam.

Pseudo-Apollodorus, in Book 3 of Library, lists Troilus as one of Hecuba's sons, adding that some say Troilus is the son of Apollo. Therefore, Pseudo-Apollodorus seems to have been aware of both versions, Troilus as the son of Priam and as the son of Apollo. In J.G. Frazer's translation:

After him Hecuba gave birth to daughters, Creusa, Laodice, Polyxena, and Cassandra. Wishing to gain Cassandra's favours, Apollo promised to teach her the art of prophecy; she learned the art but refused her favours; hence Apollo deprived her prophecy of power to persuade. Afterwards Hecuba bore sons, Deiphobus, Helenus, Pammon, Polites, Antiphus, Hipponous, Polydorus, and Troilus: this last she is said to have had by Apollo.

In the Epitome, he tries to create a sort of chronological timeline. He describes the Greeks arriving at Troy and Protesilaus being the first of them to disembark, and also being the first to die after being killed by Hector. After the death of Protesilaus, Achilles led the Myrmidons and made them disembark and continue the attack, which caused the Trojans to flee out of fear. As the Trojans fled, Achilles took advantage of this to ambush Troilus and murdered him in the temple of Apollo. At night, he captured the Trojan Lycaon. He then attacked Aeneas, who was probably unaware since the Greeks hadn’t arrived long ago, but Aeneas escaped. All this, as can be seen, happened in a short period of time. Troilus' death is said to have been at the very beginning of the war.

Of the Greeks the first to land from his ship was Protesilaus, and having slain not a few of the barbarians, he fell by the hand of Hector. His wife Laodamia loved him even after his death, and she made an image of him and consorted with it. The gods had pity on her, and Hermes brought up Protesilaus from Hades. On seeing him, Laodamia thought it was himself returned from Troy, and she was glad; but when he was carried back to Hades, she stabbed herself to death. On the death of Protesilaus, Achilles landed with the Myrmidons, and throwing a stone at the head of Cycnus, killed him. When the barbarians saw him dead, they fled to the city, and the Greeks, leaping from their ships, filled the plain with bodies. and having shut up the Trojans, they besieged them; and they drew up the ships. The barbarians showing no courage, Achilles waylaid Troilus and slaughtered him in the sanctuary of Thymbraean Apollo, and coming by night to the city he captured Lycaon. Moreover, taking some of the chiefs with him, Achilles laid waste the country, and made his way to Ida to lift the kine of Aeneas. But Aeneas fled, and Achilles killed the neatherds and Nestor, son of Priam, and drove away the kine.

Again, no mention of a sexual element, although Pseudo-Apollodorus has addressed non-consensual cases before. All we know is that Troilus was the son of Hecuba and Priam or Apollo and was murdered in Apollo's temple, ambushed by Achilles.

In Dictys Cretensis, a source that is best known for its Latin translation but has a Greek original, Troilus also appears. In Book 4,Troilus and Lycaon are captured by the Greeks as hostages after the Trojans retreat during a battle, but both are killed on the orders of Achilles who is angry with Priam. Although Troilus's beauty is emphasized, there is no sexual aspect to his death. Achilles' intention is to affect Priam, knowing that Troilus is dear to him. Unlike the other versions, the death doesn’t occur in a temple and Lycaon is killed upon his capture (in the others, he is enslaved and later freed. Only later is he killed by Achilles after Patroclus has died). In R.M. Frazer's translation:

After a few days the Greeks took up arms and, having gone onto the field, challenged the Trojans to come out and fight, if they dared. Alexander and his brothers, in answer to this challenge, set their army in order and led it forth. But before the battle lines could meet or spears be thrown, the barbarians broke formation and took to flight. We rushed upon them, from this side and that, slaughtering great numbers, or hurling them headlong into the river; they had no way to escape. And two of Priam’s sons were captured, Lycaon and Troilus, the throats of whom, when they had been brought forth into the center, were cut, by order of Achilles, who was angry with Priam for not having seen to that business they had discussed. The Trojans raised a cry of grief and, mourning loudly, bewailed the fact that Troilus had met so grievous ad death, for they remembered how young he was, who, being in the early years of his manhood, was the people’s favorite, their darling, not only because of his modesty and honesty, but more especially because of his handsome appearance.

Troilus is never mentioned again. There is also no connection between him and Apollo, he’s here exclusively indicated as the son of Priam. Personally, I interpreted Troilus here as being supposed to be a warrior, although this isn’t explicitly stated. After all, why else would he be on the battlefield? Lycaon, who was captured with him, was a warrior,

In Posthomerica, Troilus was the son of Priam and was immensely young when he was killed by Achilles. However, he entered the battle as a warrior of his own free will, presumably motivated by his great courage. There is no sexual context. The armor Troilus was wearing when he was killed by Achilles became a prize at the funeral games in honor of Achilles, offered by Thetis. In A.S. Way's translation:

Then Peleus' bride gave unto him the arms of godlike Troilus, the goodliest of all fair sons whom Hecuba had borne in hallowed Troy; yet of his goodlihead no joy she had; the prowess and the spear of fell Achilles reft his life from him. As when a gardener with new-whetted scythe mows down, ere it may seed, a blade of corn or poppy, in a garden dewy-fresh and blossom-flushed, which by a water-course crowdeth its blooms -- mows it ere it may reach its goal of bringing offspring to the birth, and with his scythe-sweep makes its life-work vain and barren of all issue, nevermore now to be fostered by the dews of spring; so did Peleides cut down Priam's son the god-like beautiful, the beardless yet and virgin of a bride, almost a child! Yet the Destroyer Fate had lured him on to war, upon the threshold of glad youth, when youth is bold, and the heart feels no void.

Fun fact: the Byzantine Syrian Ioannis Malalas offers a similar version, saying that Troilus is the son of Priam, is in the army and was killed by Achilles like Lycaon. Again, no sexual context and no Apollo.

In the Suda, a Byzantine encyclopedia, it’s said that a Greek named Strattis wrote a play inspired by Troilus with the same name. However, the play hasn’t survived. It’s in the Suda entry sigma 1178, for those interested. From what I have researched, the Greek Phrynichus supposedly also wrote a play, also lost. Furthermore, there is a surviving Epigram of Callimachus that says “For truly Troilus wept less than Priam” in a clear allusion to Troilus’ death, although there are no details. Considering, however, that Priam’s grief is the focus here, I wouldn't be surprised if he was Troilus’ father in this version. Usually when Apollo is the father, the mourning is focused on him. This is G.R. Mair’s translation, by the way.

Another lost play about Troilus was written by Sophocles and was called… Troilus! The plot was about Achilles ambushing Troilus and Polyxena and it’s possible to deduce that Troilus was also killed and mutilated (there is a term that specifically refers to mutilation, but I’ll return to that) in a temple. However, the details of the plot are lost. In Alan Sommerstein's translation, some fragments:

A (620) - “For the queen, cutting off my testicles with a knife…” = This line is said to be from Troilus's eunuch paidagogos, that is, the slave who was responsible for educating him. It’s theorized that it’s part of the prologue and that the eunuch is telling his own story, hence the reference to cutting off testicles.

B (629) - “Unbarbaric” = This line was again attributed to the eunuch. In Sommerstein's interpretation, he was perhaps praising Troilus and the use of this word perhaps meant that the slave is Greek.

C (618) - “He married as he married, a marriage in which there was no talking, when he eventually got a wrestling hold on Thetis as she changed into every shape.” = Clearly someone is talking about Peleus. Considering that Achilles is an important character in this story, Sommerstein interprets that the eunuch is telling information about Achilles.

D (trag. adesp. 561 = Strattis Fr. 42.1 K-A) - “Never come together with her, child of Zeus!” = The most relevant child of Zeus from the Trojan War is certainly Sarpedon, which led Sommerstein to theorize that perhaps Troilus was warning Sarpedon about Polyxena in an attempt to ward off possible romantic interest. However, it’s unclear who said this, who they said it to, and which woman they were talking about.

E (619) - “I have lost my adolescent master” = A servant is giving news about Troilus' fate. Perhaps it’s the eunuch, perhaps it’s another servant.

F (621) - “We were making for the flowing springs of drinking water” = The servant is telling what happened to his master, beginning the story by claiming that they were going to get water.

G (634) - “bodyguard” | H (626) - “bows without their leather cases” | J (630) - “defences” (in sense of armour) = Sommerstein suggests that it may refer to the Trojans trying to save Troilus, something that has been depicted in certain visual representations.

K (625) - “he will mow down” (in sense of slaughter) = A very likely reference to what Achilles will do, although it isn’t known who said it.

L (623) - “full of cut-off body parts” = This is a description of a type of mutilation called maschalismos (I'll explain more later). Considering the visual depictions of Achilles with Troilus mutilated, this is probably the same case here.

M (624) - “(his) hair is oiled” = Sommerstein theorizes that it is a description of Troilus dead.

N (631) - “iai!” | O (632) - “of wailing” = Someone is mourning Troilus, for these are typical laments.

There are other passages, but they’re difficult to understand in context. The general idea, then, is that Troilus, Polyxena and a servant went to fetch water, but at some point Achilles attacked them. Upon learning of this, the Trojans tried to save Troilus, but were too late. After Achilles killed Troilus, he mutilated him. Because of the extremely fragmented state of the play, it isn’t possible to know who Troilus' father is, whether he was killed in the temple (although elements of this play are consistent with visual representations that show him dead in the temple) or whether there was sexual context on Achilles' part. Honestly, in my opinion the most mysterious fragment is the one about Zeus' son. If it were “child of Thetis”, I would assume that it’s Troilus trying to ward off Achilles' interest in Polyxena, who isn’t explicitly mentioned in any fragment but there are visual representations of her going to fetch water with Troilus and so it’s generally assumed that the unnamed woman is her. However, Achilles isn’t the son of Zeus, something that is made quite clear considering that one of the fragments is about Peleus and Thetis. Therefore, it isn’t even possible to know if in this version Achilles has an interest in Polyxena. Like Sommerstein, I can only think of Sarpedon, although I’m not sure how he would be involved in this. Sommerstein theorizes that Sarpedon had a marital interest in Polyxena and that Troilus wanted to prevent this because he had incestuous feelings for his sister, something that Sommerstein believes would be possible because it could be that the play represents the Trojans as a barbarian stereotype, although possibly the Greek eunuch praises Troilus as not being barbaric. While I can understand where he's coming from, I don't think I have much faith in that argument. Either way, it's still Sarpedon's possible involvement that intrigues me the most, since he's not usually part of this myth.

Sommerstein also mentions fragments and scholias concerning Ibycus, in which he says:

Dictys is evidently blending elements from the “battle” and “murder” versions of the story. Our first literary evidence for the latter – and the only written source for it that gives any direct indication of Polyxene’s involvement – comes from a papyrus fragment that gives us six or seven words of a poem by the sixth-century lyricist Ibycus (SLG 224 = GL 282B [v]) and a few tattered lines from its scholia. The scholia make it clear that the passage related to Troilus, and the surviving words of text speak of him as a boy “like the gods” and as being killed “outside the citadel of Troy”, the scholia also refer to a sister (adelphē), and an isolated word surviving from a slightly later part of the text appears to be kasis “sibling” and to be glossed as adel[phos] “brother” or adel[phē] “sister”. In Ibycus’ poem, then, Troilus was killed somewhere outside the city, and a sister of his (surely, in view of the artistic evidence, Polyxene) was somehow involved in the episode; furthermore, the scholia speak of someone, evidently Achilles, “watching out” (epitērēsās) evidently for Troilus’ approach, and of a “murder” (phonos) committed in the sanctuary of Apollo Thymbraios. These details could in principle have been derived by the scholiast from later texts rather than from that of Ibycus; but they fit so exactly with the evidence of artistic representations from Ibycus’ own time, which are most unlikely to have been known to the scholiast, that it is hard to resist the inference that Ibycus was narrating – perhaps at length, perhaps allusively – a version of the story essentially identical to that which underlies these representations.

Thus, Ibycus' text is the oldest written version on record that has the typical elements of visual records (I’ll address this later), that is, the presence of Polyxena and the murder of Troilus in a temple of Apollo.

So, to recap, the written sources analyzed here are:

The Iliad by Homer

The Cypria attributed to Stasinus of Cyprus

Troilus by Sophocles

Alexandra by Lycophron

Fabulae attributed to Hyginus

Library attributed to Pseudo-Apollodorus

Dictys Cretensis by anonymous

Ad Lycophronem by Ioannis Tzetzes

Posthomerica by Quintus of Smyrna

Fragments by Ibycus

ROMAN TEXTUAL SOURCES

There are Roman mythology versions of Troilus, of course! Hyginus isn’t the only one (Fabulae, by the way, which is a Greco-Roman source). I usually don't consider the Roman versions for the simple reason that I don't feel that I'm familiar enough with Roman mythology, but in some cases I feel that it's interesting to consider the Roman versions. For example, in cases where I feel that the surviving Greek versions are too fragmented or summarized and sometimes doing a post on Greco-Roman mythology instead of Greek mythology sounds a little less incomplete. I do something similar when I talk about Achilles at Skyros, because unfortunately the surviving Greek sources mention the moment and don't show it per se, unlike some of the Roman sources. The Roman frescoes of the Skyros episode are also an interesting source. With Troilus, I particularly find it interesting to see it from a Greco-Roman perspective rather than just a Greek perspective because, as seen, in the surviving Greek versions he is mostly mentioned.

In Virgil's Aeneid, Troilus is a warrior, but he is young and Achilles isn’t exactly a fair match for him. He was killed by Achilles while in his chariot, apparently. There is no sexual context. Considering that the events are being recorded in chronological order, it’s likely that Troilus' death occurred in the early years of the war. From what I understand, he is Priam's son since the situation is earlier described as "the sons of Atreus, of Priam, and Achilles angered with both". In A.S. Kline's translation:

[...] While, waiting for the queen, in the vast temple, he looks at each thing: while he marvels at the city's wealth, the skill of their artistry, and the products of their labours, he sees the battles at Troy in their correct order, the War, known through its fame to the whole world, the sons of Atreus, of Priam, and Achilles angered with both. He halted, and said, with tears: 'What place is there, Achates, what region of earth not full of our hardships? See, Priam! Here too virtue has its rewards, here too there are tears for events, and mortal things touch the heart. Lose your fears: this fame will bring you benefit.' So he speaks, and feeds his spirit with the insubstantial frieze, sighing often, and his face wet with the streaming tears. For he saw how, here, the Greeks fled, as they fought round Troy, chased by the Trojan youth, and, there, the Trojans fled, with plumed Achilles pressing them close in his chariot. Not far away, through his tears, he recognises Rhesus's white-canvassed tents, that blood-stained Diomedes, Tydeus's son, laid waste with great slaughter, betrayed in their first sleep, diverting the fiery horses to his camp, before they could eat Trojan fodder, or drink from the river Xanthus. Elsewhere Troilus, his weapons discarded in flight, unhappy boy, unequally matched in his battle with Achilles, is dragged by his horses, clinging face-up to the empty chariot, still clutching the reins: his neck and hair trailing on the ground, and his spear reversed furrowing the dust. [...]

In a scholia of the Aeneid, Servius gives more details. Unfortunately, I couldn't find it translated, so I won't include excerpts here. However, I'll try to give a general idea of what he says. Basically, he says that in one version Achilles used doves to lure Troilus, who was enchanted by the animals and wanted to hold them. Taking advantage of Troilus's distraction, Achilles killed him. According to Servius, Virgil changed this because it wouldn't be typical of a heroic epic (the hero here being Troilus, who in Aeneid died fighting), although this is Servius's theory of what Virgil may have meant. The doves suggest a possible sexual context, since they were considered a kind of courtship gift (this isn’t said by Servius, it is an interpretation of modern academics. Doves were indeed common gifts). Also according to Servius, an oracle said that three things were relevant to the fate of Troy: the life of Troilus, the Palladium (the statue of Athena) and the tomb of Laomedon (a previous Trojan king). Therefore, it’s possible that the version known to Servius includes Achilles deciding to kill Troilus because of the prophecy. Furthermore, Servius also mentions the presence of the temple.

Horace alludes to the Trojans mourning Troilus, but not excessively (something he compares to Nestor's mourning of Antilochus). He doesn't give any details, however. But, well, we know he's dead, and considering Achilles is almost always the killer, I imagine it must have been him here too. That’s in “Stop Weeping,” a poem that was apparently about not letting yourself be overcome by grief. It says "Troilus’s Trojan parents and sisters", so I imagine Troilus' father here is Priam. In Kline's translation:

[...] Yet Nestor, who lived for three generations, didn’t mourn his beloved Antilochus, every moment, nor were the youthful Troilus’s Trojan parents and sisters, always weeping. [...]

Statius, in Silvae, says that Troilus was killed by Achilles when he was struck by his spear while running around Troy. There is no mention of a temple, and it’s also not possible to be certain who his father is here. Statius is comparing someone else to the beauty of characters like Achilles and Troilus, claiming that this person is more handsome than them, but there isn’t really a sexual context to Troilus' death necessarily. In A.S. Kline's translation:

[...] I saw him, and see him still, a fairer shape than Achilles when Thetis hid him on the maiden-haunted shore, that he might beware of battle; or Troilus, when the lance from the hand of Achilles overtook him as he sped round the walled town of merciless Phoebus. [...]

Also, there is this: “and so would Troilus sweep round in a nimbler ring and baulk the menacing chargers of the foe”. Maybe Troilus was a warrior here too?

Seneca the Younger wrote Agamemnon, which tells the story of Agamemnon's return to Mycenae. At one point, Cassandra prophesies her own death, to which she says, "thee, Troilus, I follow, to early with Achilles met" in Frank Miller's translation. Although there are no further details, it is clear that Troilus was killed by Achilles. However, whether the "to early" refers to Troilus being young (a typical Troilus trait) or to his death early in the war (as is the case in some of the versions here), I’m not sure. It isn’t clear who Troilus' father is, and the sexual context isn’t stated, although some have theorized that the "met" may imply something sexual.

Asonius wrote epitaphs, one of which was for Troilus. In Evelyn-White's translation:

THOUGH Hector was laid low, and though in strength of arm and heavenly aid ill-matched, I, Troilus, met the fierce son of Aeacus face to face, and, dragged to death by my own steeds, am linked in glory with my brother, whose example made my sufferings light.

Similar to the Aeneid, here Troilus died trapped in his own chariot. He didn't run away from Achilles or try to hide from him, but directly confronted him, eventually being defeated. There is no way of knowing the location of his death or who Troilus' father is. Considering that Troilus confronted Achilles, there is a chance that this isn’t the version in which Troilus seeks protection from Apollo.

There is also Dares Phyrigius. It has been theorized that it may actually be a Latin translation of a Greek original, similar to what happened with Dictys Cretensis. However, as no concrete evidence has been found for this, I’ll assume that it’s a Roman source. Troilus is described as the youngest of Priam's sons, but still a warrior and someone who is brave. Furthermore, he had a great position in the army hierarchy. In R.M. Frazer's translation:

When news was brought to Priam [...] He returned to Troy, along with his wife, Hecuba, and his children [...] Troilus [...]

But Troilus, who, though youngest of Priam’s sons, equalled Hector in bravery, urged them to war and told them not to be frightened by Helenus’ fearful words.

Troilus, a large and handsome boy, was strong for his age, brave, and eager for glory.

[...] Priam made Hector commander-in-chief of these leaders and their armies. Second-in-command were Deiphobus, Alexander, Troilus, Aeneas, and Memnon.

On the next day the Trojans led forth their army. And the forces of Agamemnon came opposite. A horrible slaughter arose. Both armies fought fiercely; Troilus slaughtered many Greek leaders, as the battle lasted seven days.

[...] Diomedes and Ulysses answered that Troilus was the bravest of men and the equal of Hector. [...]

When the time for fighting returned, Agamemnon, Menelaus, and Ajax led forth the army. The Trojans came opposite. A great slaughter arose, a fierce and raging battle on both sides. Troilus, having wounded Menelaus, pressed on, killing many of the enemy and harrying the others. Night brought an end to the battle.

On the next day Troilus and Alexander led forth the Trojans. And all the Greeks came opposite. The battle was fierce. Troilus wounded Diomedes and, in the course of his slaughter, attacked and wounded Agamemnon himself.

And there are several other examples. Troilus is repeatedly described as one of the leaders of the Trojan army and as being a threat to the Greeks. However, he is eventually killed by Achilles in a battle against the Myrmidons. Achilles kills him because Troilus had killed a lot of his Myrmidons.

On the seventh, the battle still raging, Achilles (who until then had stayed out of action because of his wound) drew up his Myrmidons and urged them bravely to make an attack against Troilus. Toward the end of the day Troilus advanced on horseback, exulting, and caused the Greeks to flee with loud cries. The Myrmidons, however, came to their rescue and made an attack against Troilus. Troilus slew many men, but, in the midst of the terrible fighting, his horse was wounded and fell, entangling and throwing him off; and swiftly Achilles was there to dispatch him. Then Achilles tried to drag off the body. But Memnon maintained a successful defense, wounding Achilles and making him yield. When, however, Memnon and his followers began to pursue Achilles, the latter, merely by turning around, brought them to halt. After Achilles’ wound had been dressed and he had fought for some time, he slew Memnon, dealing him many a blow; and then, having been wounded himself, yielded from combat again. The rest of the Trojan forces, knowing that the king of the Persians was dead, fled to the city and bolted the gates. Night brought an end to the battle.

As you can see, this is a... very different version. In fact, there are numerous differences here besides Troilus. Achilles, for example, doesn’t get to face Penthesilea and Neoptolemus is the one who does so. Andromache sails away with Helenus, rather than them being enslaved by Neoptolemus. Protesilaus dies late, although he's usually the first Greek to die. Patroclus is pretty useless most of the time, honestly. Castor and Polydeuces tried to go after Helen, but were thrown off course by a storm. Etc. Etc. Dares Phyrigius is a generally ignored source precisely because it has so many changes that many people consider common themes of the Trojan War myth to have been somewhat lost, but I've included it here for the sake of completeness.

Plautus mentions three conditions for the fall of Troy in the play Bacchides, in which one of the characters says: “I have heard that there were three destinies attending Troy, which were fatal to it; if the statue should be lost from citadel, whereas the second was the death of Troilus; the third was when the upper lintel of the Phrygian gate should be demolished”. Again, the death of Troilus is a condition for Troy to be destroyed. There are no other details, no hint of sexual context, no mention of who Troilus' father is, etc.

Finally, Cicero in Tusculan Disputations says “Though Callimachus does not speak amiss in saying that more tears had flowed from Priam than his son”, referring to the Epigram of Callimachus in which he says that Troilus wept less than Priam. Translated by C.D. Yonge.

So, to recap, the written sources analyzed here are: (+Fabulae, anteriormente analisada) são:

Fabulae attributed to Hyginus

Aeneid by Virgil

Scholia of Aeneid by Servius

Odes by Horace

Silvae by Statius

Epitaphs by Asonius

Dares Phrygius by anonymous

Bacchides by Plautus

Tusculan Disputation by Cicero

GENERAL IDEA OF THE TEXTUAL SOURCES

Finally, I’ll add another written source that I didn’t add before because it isn’t exactly Greek or Roman. However, it seems that whoever wrote it had contact with at least Greek scholia and some Latin texts (like Aeneid), so I’ll consider it as a Greco-Roman mythology source, although I don’t know exactly the nationality of the writer. I’m referring to the so-called First Vatican Mythographer. Surprisingly, I found a Brazilian translation more easily than an English translation, so I’ll use that. I won’t include excerpts because… well, it’s in Portuguese. But I’ll summarize!

In the third book attributed to this person, there is a section on genealogy in which Troilus is explicitly stated to be the son of Priam and Hecuba along with other characters such as Helenus, Cassandra, Hector, etc. In a section specifically about Troilus, it’s said that he led the horses out of Troy, but was ambushed by Achilles. Troilus returned to Troy tied to the horse. It’s then said that there was a prophecy that Troilus would not be able to reach the age of 20, or else Troy wouldn’t be destroyed, which was the motivation for his death. The translator of the text, Ana Paula Silva Santos, mentions the similarity of the death scene to the Aeneid and also mentions the scholia of Servius in the section referring to the prophecy. Notably, Troilus isn’t the son of Apollo, there is no mention of him dying in a temple and there is no sexual context.

Therefore, in a more or less chronological order (because it isn’t possible to be 100% sure of all the dates), we have that in the written sources of Greek mythology:

The Iliad by Homer (8th century BC) - Troilus is the son of Priam, probably a warrior (more specifically, a “chariot fighter”), and he was killed by Achilles. We don’t know his age or when he died, although scholia argue that he wasn’t a boy to Homer. There is no sexual context.

The Cypria, attributed to Stasinus of Cyprus (possibly 7th century BC, but some suggest 6th century BC) - Troilus was killed by Achilles early in the war. There are no further details, not even certain of his parentage or age. There is no sexual context. The reason for the lack of details is that the original text of the epic is lost.

Troilus by Sophocles (5th century BC) - Extremely fragmentary, making it difficult to be certain of the details. It’s certain that Troilus is young here, as one of the surviving descriptions refers to him as young. He was killed by Achilles and most likely mutilated. It isn’t possible to be certain of the motive for the murder.

Epigrams by Callimachus (3rd century BC) - Troilus is dead and Priam mourns him. There are no other details.

Alexandra by Lycophron (possibly 2nd century BC) - Troilus is the biological son of Apollo and the “adopted” son of Priam. Because he was described as a "cub" he appears to be young. He was killed by Achilles in the temple of Apollo, who was angry with Achilles for this death. It’s very possible to interpret a sexual context.

Fabulae, attributed to Hyginus (1st century) - Troilus is the son of Priam and was killed by Achilles. We don’t know anything else, not even his age or the place of the murder. There is no sexual context.

Library, attributed to Pseudo-Apollodorus (1st/2nd century AD) - There is a version in which he is the son of Priam and a version in which he is the son of Apollo, but in both he is the son of Hecuba. He was killed by Achilles at the beginning of the war inside a temple of Apollo. By the birth order of Hecuba's sons, he was one of the youngest. There is no sexual context.

Dictys Cretensis, author unknown (date uncertain, but fragments of the original Greek have led some to theorize that it may have been from the 1st or 2nd century AD) - Troilus is the son of Priam and fought on the battlefield, but was captured by the Greeks. He then had his throat slit on Achilles' orders as a way of retaliating against Priam. He was young and there is no mention of Apollo in his parentage. There is no sexual context.

Posthomerica by Quintus of Smyrna (4th century AD) - Troilus was killed by Achilles in battle, since Troilus was a warrior. He was the son of Priam and there is no sexual context.

Ad Lycophronem by Ioannis Tzetzes (12th century AD) - Tzetzes says that Troilus was second best in war after Hector, not Deiphobus. He also says that Lycophorn's version is that Achilles fell in love with Troilus, who did not reciprocate the feeling. This angered Achilles, causing Troilus to flee and take refuge inside the temple of Apollo. Achilles tried to persuade him to leave, but Troilus obviously didn’t want to comply. So Achilles killed him inside the temple, later beheading him. In Lycophorn's version, Troilus was the son of Apollo. Tzetzes, however, doesn’t seem to believe this version very much, because in his opinion Troilus wasn’t worth of Achilles’ love (yes, that is the argument). He then goes on to mention a version in which, after Achilles killed Memnon, he killed Troilus.

Scholia of The Iliad by various authors (various centuries) - There is no sexual context. The scholia says that he wasn’t a boy in Homeric poetry, but became a boy in later depictions. It is said that in Sophocles' version Troilus was exercising the horses when he was ambushed.

We have that in the written sources of Roman mythology:

Fabulae, attributed to Hyginus (1st century) - Troilus is the son of Priam and was killed by Achilles. We don’t know anything else, not even his age or the place of the murder. There is no sexual context.

Bacchides by Plautus (1st century BC) - The death of Troilus was one of the requirements for the fall of Troy. No further details.

Tusculan Disputations by Cicero (1st century BC) - Just a reference to Callimachus.

Aeneid by Virgil (1st century BC) - Troilus was killed by Achilles while trying to escape from him in his chariot, probably very early in the war. He was young and probably the son of Priam. There is no sexual context.

Odes by Horace (1st century BC) - Troilus was killed. His killer isn’t named, but I wouldn't be surprised if it was Achilles. No details, but he was young. There is no association of kinship with Apollo, although there is an association with the Trojans. Most likely the son of Priam here. There is no sexual context.

Agamemnon by Seneca the Younger (1st century) - Troilus was killed by Achilles very early in the war. There is no detail as to who the father is and no mention of sexual context.

Silvae by Statius (1st century AD) - Troilus was outside the walls of Troy when he was pursued by Achilles. He tried to escape, but Achilles struck him with his spear. There is no sexual context and it isn’t possible to be certain who his father is.

Epitaphs by Asonius (4th century AD) - Troilus was killed by Achilles in battle. There is no sexual context, it isn’t possible to know the location, it isn’t known who Troilus' father is.

Scholia of the Aeneid by Servius (4th/5th century AD) - Troilus was killed by Achilles in the temple. Although the sexual context isn’t stated, it’s quite likely that there is such a context because of the nature of the gifts (doves, often associated with gifts with erotic intentions). It isn’t possible to know who Troilus' father is. Troilus' death was prophesied to be the fall of Troy.

Dares Phrygius by ? (? AD. Perhaps 5th century AD) - Troilus was a young but talented and strong son of Priam. He wasn't killed at the beginning of the war, but considerably later. He died in a battle against the Myrmidons after his horse was wounded, which allowed Achilles to kill him more easily. There is no sexual context or association with Apollo.

So, here I have taken into consideration, in alphabetical order, the following written sources:

Alexandra (Lycophron)

Ad Lycophronem (Ioannis Tzetzes)

Aeneid (Virgil)

Agamemnon (Seneca the Younger)

Bacchides (Plautus)

Dares Prygius (?)

Dictys Crentesis (?)

Epigrams (Callimachus)

Epitaphs (Asonius)

Fabulae (Hyginus or Pseudo-Hyginus)

First Vatican Mythographer (?)

Library (Pseudo-Apollodorus)

Odes (Horace)

Posthomerica (Quintus of Smyrna)

The Cypria (Stasinus of Cyprus)

The Iliad (Homer)

Troilus (Sophocles)

Tusculan Disputations (Cicero)

Scholia of Aeneid (Servius)

Scholia of The Iliad (vários autores)

Silvae (Statius)

Fragments of Ibycus (Ibycus)

So, let's look at the general details of the written sources of Greco-Roman mythology:

Of 22 sources, 11 indicate/suggest Priam as Troilus’ father (The Iliad, Epigrams, Tusculan Disputations, Fabulae, Aeneid, Library, Dictys Cretensis, Dares Phrygius, Posthomerica, scholia of The Iliad, First Vatican Mythographer), 3 indicate/suggest Apollo as Troilus’ father (Alexandra, Ad Lycophronem, Library) and in 8 it isn’t possible to know/deduce (The Cypria, Horace’s Ode, Seneca’s Agamemnon, Epitaphs, Silvae, Bacchides, Ibycus’ fragments, Troilus)

Of 22 sources, 5 explicitly state that there is a temple in the scene (Alexandra, Ad Lycophronem, Library, Servius’ scholia, Ibycus’ fragments), 16 either don’t place the location in a temple or don’t state the location explicitly (Aeneid, Silvae, Dictys Cretensis, Dares Phrygius, scholia of The Iliad, First Vatican Mythographer, The Iliad, The Cypria, Callimachus, Tusculan Disputations, Fabulae, Horace’s Ode, Epitaph, Seneca’s Agamemnon, Posthomerica, Bacchides) and 1 is very possibly in the temple but is uncertain (Troilus). In any case, it’s obviously outside Troy.

Of 22 sources, 3 indicate/suggest sexual context (Alexandra, Ad Lycophronem, Servius' scholia), 18 don’t indicate/suggest sexual context (Ibycus' fragments, The Iliad, The Cypria, Fabulae, Epigrams, Tusculan Disputations, Library, Dictys Cretensis , Aeneid, Horace's Ode, Seneca's Agamemnon, Epitaphs, Silvae, Dares Phrygius, scholia of The Iliad, Posthomerica, First Vatican Mythographer, Bacchides) and 1 is very uncertain (Troilus).

Of 22 sources, 3 indicate a prophecy (Servius’ scholia, First Vatican Mythographer, Bacchides)

Troilus is always young, although the age itself varies (sometimes a child, sometimes a teenager. In the case of Homer and his scholia, possibly a young adult). Most of the time, it isn’t possible to know at what point he was killed, although the time is commonly placed at the beginning of the war in sources that mention some chronology. He wasn’t infrequently portrayed as a warrior, although he was also emphasized as more weaker than Achilles in the vast majority of cases, making any idea of fighting doomed to Troilus' defeat. In Sophocles, it’s possible to learn that Troilus was mutilated after his death. The vast majority of written versions don’t mention the presence of Polyxena (Ibycus and possibly Sophocles, yes, though), although it was a recurring theme in visual art. Troilus is also associated with horses, something present since the earliest written source (The Iliad) and in some versions his corpse is still tied to the horses/chariot (for example, Aeneid).

NOTE: I chose to say “indicate/suggest” because in some cases it isn’t possible to say for sure. For example, we don’t have the epic The Cypria to be sure of its content.

VISUAL SOURCES

Another very important aspect is the visual sources. I won't list all the ones I know, just enough to cover the general themes and possibilities. To start, I'll bring here what is probably the artistic representation that I see most being shared.

Here we have a reconstruction of a 5th century BC Greek artwork that shows Achilles forcibly pulling Troilus from his horses and preparing to kill him on an altar, which suggests that this artwork depicts Troilus being murdered in the temple of Apollo. Note that Troilus is depicted here as a child, and not as a teenager as is sometimes the case. In general, Troilus isn’t an adult, although whether he is a child or a teenager varies. This particular artwork is on a cup, which is interesting. While researching this, I found this:

Why was this image of Achilles killing a Trojan boy depicted on the inside of a drinking cup? Ancient symposia were usually organized by wealthy men, who would drink, engage in discussions on a variety of serious and not-so-serious topics, sing songs, engage in sexual behaviour, and so forth. Wine flowed freely, so things could naturally get rowdy. The kylix dates from the early fifth century BC, when practices such as pederasty were commonplace, at least in ancient Athens, where this cup was made. Among the Greeks, the image of Troilus could have been used as the starting off point to celebrate youthful beauty in a general sense or to sing the praises of a living youth in particular. But while the cup was produced in Greece, it was consumed by Etruscans. Pederasty isn’t clearly attested in Etruria, so the image may have had a different meaning to them. Joshua Hall suggested to me that the Troilus scene appealed to the Etruscans because it shows Achilles carrying out a divine commandment with physical force, a popular theme in Etruscan myth.

Achilles’ slaying of Troilus by Josho Brouwers.

Here, Brouwers suggested a possible sexual context because of the kylix's date of production and also because it was a kylix that was likely used in symposia. He didn't mention this, but another characteristic that I've seen pointed out as supporting this interpretation is the way Achilles drags Troilus by his hair in a manner similar to how Ajax the Lesser's attack on Cassandra is often depicted, and we know that Ajax was sexually motivated. However, it seems that this particular kylix was more likely made with the Etruscans in mind, and the Etruscans didn’t have the same pederastic culture as Classical Greece as far as we can tell, which makes it more likely that this art had another meaning for them. Hall suggested that they simply liked the idea of Achilles carrying out a divine order through violence, a common theme among the Etruscans. But the idea that the Etruscans saw it this way implies the existence of the myth of Troilus' prophecy as early as the 5th century BC, something that we cannot confirm from the surviving written sources and we can only theorize. After all, the version in which Achilles kills Troilus to fulfill something greater is related to the prophecy.

However, the idea of grabbing someone by the hair isn’t inherently sexual. In fact, it’s probably less about sexual interest and more about subjugation. This subjugation, of course, can be sexually motivated, as is the case with the times when Ajax the Lesser is depicted pulling Cassandra by her hair, but not necessarily. Regarding this, a profile called Academic Writing shared: