#general Leslie groves

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Meeting General Leslie Groves @manicpixieginger

#oppenheimer#j Robert oppenheimer#Robert oppenheimer#cillian murphy#matt damon#Leslie groves#general Leslie groves#chris nolan#Christopher nolan#oppenheimer imax#oppenheimer movie#oppenheimer gifset#gifset#my gifs

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Atomic Secrets: The Scientists Who Built The Atom Bomb 💣

Science and the military converged under a cloak of secrecy at Los Alamos National Laboratory. As part of the Manhattan Project, Los Alamos — both its very existence and the work that went on there — was hidden from Americans during World War II.

Many of the thousands of scientists on the project were not officially aware of what they were working on. Though they were not permitted to talk to anyone about their work, including each other, by 1945 some had figured out that they were in fact building an atomic bomb.

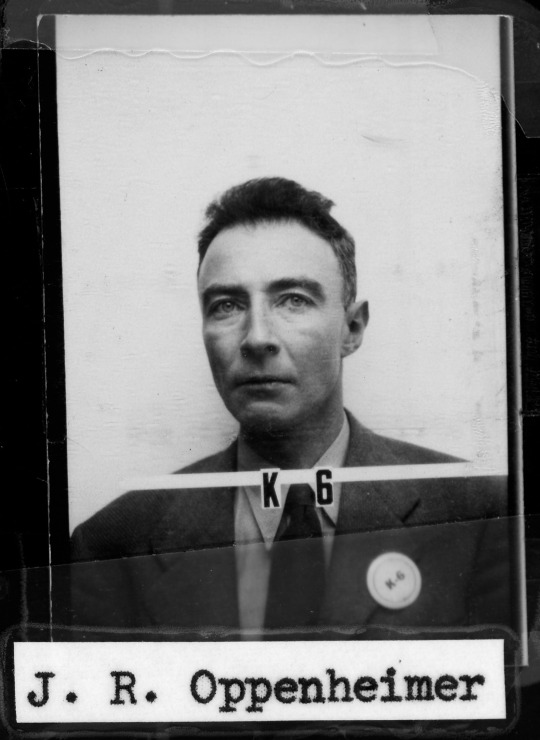

In 1943 J. Robert Oppenheimer was named the director of the Bomb Project at Los Alamos, a self-contained area protected -- and completely controlled -- by the U.S. Army. Special driver's licenses had no names on them, just ID numbers. Credit: Courtesy of the Los Alamos National Laboratory Archives

Robert Oppenheimer's wife Kitty was not above scrutiny. All who were affiliated with the project -- and their spouses -- were thoroughly screened and had a security file with the FBI. Credit: Courtesy of the F.B.I.

Less than a year after Oppenheimer proposed using the remote desert site for the laboratory, Los Alamos was already home to a thousand scientists, engineers, support staff… and their families. By the end of the war the population was over 6,000, and the compound included amenities like this barber shop. Credit: Time Life/Getty Images

Atomic Bomb Project employees having lunch at Los Alamos. Though food was often in scant supply, residents made the best of life in their isolated community by putting on plays and organizing Saturday night square dances. Some singles’ parties in the dormitories reportedly served a brew of lab alcohol and grapefruit juice, cooled with dry ice out of a 32-gallon GI can. Credit: Copyright Bettmann/CORBIS

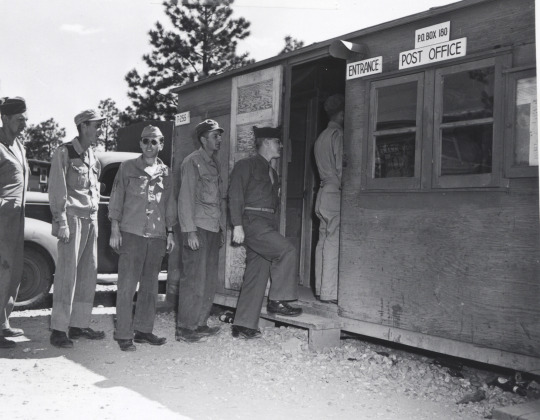

Completely self-contained, the Los Alamos facility did not officially exist in its early years except as a post office box. Scientists’ families were mostly kept in the dark about the nature of the project, learning the truth only after the bomb was dropped on Hiroshima. Credit: Courtesy of the Los Alamos National Laboratory Archives

Credited with inventing the cyclotron, University of California-Berkeley physicist Ernest Lawrence (squatting, center) looks on as Robert Oppenheimer points out something on the 184” particle accelerator. Harvard University supplied the cyclotron that was used to develop the atomic bomb. Credit: Copyright CORBIS

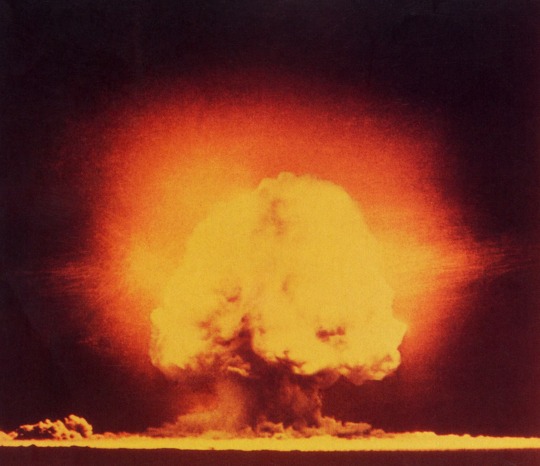

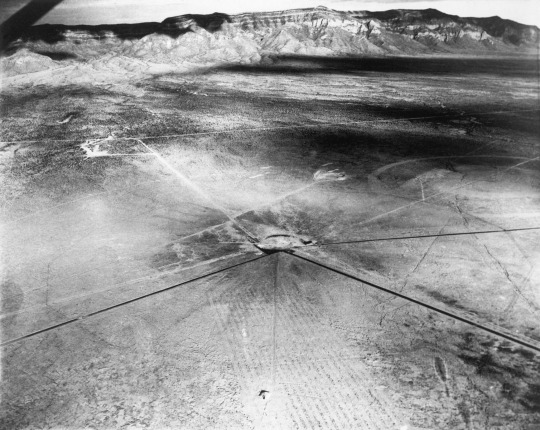

The Trinity bomb was the first atomic bomb ever tested. It was detonated in the Jornada del Muerto (Dead Man’s Walk) Desert, near Alamogordo, New Mexico, on July 16, 1945. The test was a resounding success. The United States would drop similar bombs on Japan just three weeks later. Credit: Courtesy of the Los Alamos National Laboratory Archives

Oppenheimer and General Leslie Groves inspect the melted remnants of the 100-foot steel tower that held the Trinity bomb. Ensuring that the testing of a bomb with unknown strength would remain completely secret, the government chose a location that was so remote they had to import their water from over 150 miles away. Credit: Copyright CORBIS

Oppenheimer and General Leslie Groves stand in front of a map of Japan, just five days before the bombing of Hiroshima. Credit: Copyright CORBIS

Though there was no evidence that Oppenheimer had betrayed his country in any way, several officials called his loyalty into question in the Cold War environment of 1954. After being subjected to months of hearings, “the most famous physicist in the world” eventually lost his government security clearance. Credit: Reprinted courtesy of TIME Magazine

#Atomic Secrets#Scientists#Atomic Bomb#American 🇺🇸 Experience#NOVA | PBS#Los Alamos National Laboratory#Manhattan Project#World War II#J. Robert Oppenheimer#Katherine Oppenheimer#New Mexico#Hiroshima | Nagasaki#University of California-Berkeley#Harvard University#Jornada del Muerto (Dead Man’s Walk) Desert 🐪#Alamogordo New Mexico#General Leslie Groves#Japan 🇯🇵#TIME Magazine

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

'Australian nuclear experts have reviewed Oppenheimer and say it is epic, intense and compelling – but not always accurate.

Its portrayal of the first atomic bomb detonation, for example, lacked the “violet hues” and heat wave of the real thing.

“Some characters even made comments like ‘quantum mechanics is hard’, which I disagree with – it’s only hard if someone hasn’t explained it properly,” says Dr Kirrily Rule, an instrument scientist who works with the thermal triple-axis spectrometer Taipan at the Australian Nuclear Science and Technology Organisation (Ansto).

Rule gives Christopher Nolan’s movie about the Manhattan project four stars, saying it’s exciting and suspenseful but the science is “brushed over”.

“As a physicist watching the movie, I think they could have been much clearer on the science involved … I believe Nolan used such high-level jargon as a confusing element to the film intentionally.

“It made the audience feel separated from these scientific giants. As a scientist and teacher, I think this is a poor way to represent science – it just continues to give people the impression that ‘science is too hard’.”

The Irish actor Cillian Murphy plays J Robert Oppenheimer, the theoretical physicist who led the Manhattan Project’s Los Alamos laboratory, which produced the bomb. It portrays his pride, his remorse and his downfall.

Dr Ceri Brenner (four stars), leader of Ansto’s Centre for Accelerator Science, says the one thing missing for her is an element of the 1945 detonation in New Mexico, which was codenamed Trinity.

“[When] the device went off, we got the flash of light and the silence, but I didn’t notice anyone reacting to the immediate experience of heat that accompanied the visual of the flash,” she says.

“The energy emitted from fission is radiative and carried long distances via electromagnetic radiation, which travels at the speed of light, compared to conductive or convective heat that propagates more like the sound wave boom that arrived shortly after.

“I saw a documentary where someone described it as being similar to opening an oven door and feeling the immediate bath of heat emerging.”

Dr Mark Ho (four stars), a nuclear analyst, says he would have liked to have seen the atomic explosion “more faithfully portrayed in violet hues”.

Major General Thomas Farrell, deputy to Manhattan Project director Leslie Groves (played by Matt Damon in the film), has described the detonation as “birth of a new age – the age of atomic energy”.

“The whole country was lighted by a searing light with the intensity many times that of the midday sun,” he said, according to the Conversation.

“It was golden, violet, grey and blue. It lighted every peak, crevasse and ridge of the nearby mountain range with clarity and beauty that cannot be described but must be seen to be imagined.”'

#Oppenheimer#Christopher Nolan#Cillian Murphy#General Thomas Farrell#Leslie Groves#Matt Damon#Dr. Mark Ho#Dr. Ceri Brenner#Dr. Kirrily Rule#The Manhattan Project#Los Alamos

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

On 20 July 1943 he sent the following telegram:

WAR DEPARTMENT, OFFICE OF

THE CHIEF OF ENGINEERS,

Washington, July 20, 1943

Subject: Julius Robert Oppenheimer.

To: The District Engineer, United States Engineer Office, Manhattan District, Station F, New York, N.Y.

I. In accordance with my verbal directions of 15 July it is desired that clearance be issued for the employment of Julius Robert Oppenheimer without delay, irrespective of the information which you have concerning Mr Oppenheimer. He is absolutely essential to the project.

L. R. GROVES, Brigadier-General,

CE

"Brighter than a Thousand Suns: A Personal History of the Atomic Scientists" - Robert Jungk, translated by James Cleugh

#book quotes#brighter than a thousand suns#robert jungk#james cleugh#nonfiction#july 20#20 july#telegram#leslie richard groves#40s#1940s#war department#engineers#washington#j robert oppenheimer#manhattan#new york#address#brigadier general#security clearance

0 notes

Note

Wait why do we hate John von Neumann

Well okay the reasons implicit in that particular post (software was a mistake, von Neumann's work enabled software to exist as it does, ergo,) are jokes, but there's this

Von Neumann was included in the target selection committee that was responsible for choosing the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki as the first targets of the atomic bomb. Von Neumann oversaw computations related to the expected size of the bomb blasts, estimated death tolls, and the distance above the ground at which the bombs should be detonated for optimum shock wave propagation. The cultural capital Kyoto was von Neumann's first choice,[333] a selection seconded by Manhattan Project leader General Leslie Groves. However, this target was dismissed by Secretary of WarHenry L. Stimson.[334]

>does extensive math to accurately predict and maximize destruction and death toll >first choice of target is civilian cultural capital

#I have memories of reading that he was like very gung-ho about Kyoto#and vague memories that the higher population (and in particular civilian) density was a key component of his motivations#but I can't find anything to that effect currently so idk‚ maybe I hallucinated it

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

saw a post that said "nuclear energy requires less mining and exploitation of the global south than wind and solar" and i don't really want to antagonize whoever said that but i do have some related study questions:

is there anything else that we use fissile material for?

do these applications affect the global south?

is there a name for the political doctrine describing the way these applications affect geopolitics?

does the electrical grid affect the pace of exploitation?

who are the common members of a) nuclear states, b) allied powers, and c) the UNSC P5? why?

would distributing reactor technology only to allies post-war affect the character of exploitation?

bonus questions: were the allied powers truly allies, in the longterm? general leslie groves said the purpose of the bomb was to subdue whom? who did the US government send aid to, in the leadup to the chinese revolution of 1949, and why?

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

On this day, August 13, in 1942 The Manhattan Project commences under the direction of US General Leslie Groves with the aim of developing an atomic bomb.

The above photo are the Calutron Girls' monitoring a mass spectrometer during the Manhattan Project. Gladys Owens, in the foreground, did not know what she was involved with until seeing this picture on a tour fifty years later.

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

two things I need to see in the oppenheimer movie, since there are actors credited for feynman and bohr:

that time feynman found a hole in the fence around the los alamos research center and thought, “it’s time to go… 🐭 mouse mode…” and kept popping through the hole and taking laps in and out of the facility. even though if security caught him they’d have killed him. any acknowledgment in general that the physicists involved in the manhattan project were so casual with security to the point they were actually risking their lives.

bohr as a comic relief character. we truly are siblings in arms as stupid science bitches. after denmark was invaded by the nazis, he was smuggled out of the country into sweden because he was jewish. the problem was, he wasn’t particularly interested in staying hiding, didn’t feel like staying put, and he kept picking up the phone and saying “hello 🙂 niels bohr here”. so the people who were hiding him said “hey. we need to get him out of stockholm immediately or he’s getting captured.” so he was evacuated on an aircraft called a mosquito, however, 1) his head was too big to fit any helmet and 2) while he was being given instructions of what to do on the plane, he just blabbed through them. he did not know that he needed to put on an oxygen mask after a certain altitude, and lost consciousness. the crew was freaking out and said, “oh fuck. oh shit. we killed niels bohr” (paraphrasing). when they landed, he woke up and told them, “I just had the most wonderful nap 🙂”. also, when he finally arrived in the US, he kept wandering off from his security detail, was too absent-minded to remember that he needed to use a pseudonym, and introduced himself to random people as, “hi. I’m physicist niels bohr”. Leslie grove basically had to drag him to new mexico by the collar of his shirt. and when he finally got there, he recalled that he’d talked about nuclear fission with werner heisenberg, but forgot most of the details on account of being a terrible listener. a role model if I ever had one…

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ground Zero showing the melted remains of the atomic bomb tower after the first atomic test viewed by Dr. J. R. Oppenheimer, Director of Los Alamos Atomic Bomb Project and Physicist (center with light hat) and Maj General Leslie R. Groves (center), Alamogordo, NM.

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

Barbenheimer Part 2: My thoughts on Oppenheimer.....

After a 50 min break after Barbie, I settle down to watch Oppenheimer in IMAX. I am a big fan of Nolan's movies. I haven't seen Following, but I either like or love every movie he has made. He's one of the few directors who is the star of his own movie, whether the lead actor is someone as famous as Leonardo DiCaprio or some unknowns like in Dunkirk. So I went in with high expectations and Nolan lived up to those expectations again.

Oppenheimer is a movie that leaves you shaken. I genuinely can't believe how a 3 hour movie which is all talk, ended up being so gripping that it just rushed by. This summer has seen its fair share of long movies, with a majority of summer blockbusters clocking in around 2.5 hours, but I felt the length with all of them. Not with Oppenheimer though. While I would hesitate to call it Nolan's best, its easily one of the best of the year.

What is amazing is the film is essentially two films at once. One is a movie about the construction of the bomb and the Trinity test and subsequent deployment of those bombs. The second is a courtroom drama of two legal proceedings happening at different points in time. Both movies are riveting and the structure of the movie is enthralling. The first act of the film basically acts as the first 2 acts of both movies. It sets up the characters, the various dynamics etc.... Then the second act is essentially the final act of the first movie, and the third act, if the final act of the second movie. It was a genius way to keep audience enthralled throughout.

The film is just filled with extraordinary work by everyone involved. The cinematography, costume design, product design, the practical effects, the performances, the directing etc... is all superb. I fully expect this film to get a lot of Oscar nomination come Oscar season. The characters are extremely well realized, and not just Oppenheimer or Strauss, but every single individual. There are so many known actors that appear in this film, sometimes just for a scene or two, but somehow every character is a fully realized character. I also like that Oppenheimer is portrayed as man. He has flaws, but he also has traits to be admired. Even Strauss is not portrayed as evil, just vindictive. Also, as someone who is in the Engineering field, the construction of the bomb was just fascinating to me. I loved watching legendary 20th century scientists, who are rockstars of the scientific community, depicted as people and I loved a lot of their individual interactions. The scenes between Oppenheimer and Einstein for example, were terrific. The final scene between them is genuinely terrifying. In general, the way Oppenheimer's mind is visualized is awesome.

There is not much in terms of flaws. The film is talky. For some, that may be boring. I can maybe say that the actual portrayal of the explosion, while exciting, was not as bombastic and horrifying as it could have been. There are moments in the courtroom drama part of the film, where it feels like it could have been edited down a little. And it took me about 15 minutes to get a handle on the structure of the film and the back and forth time jumps. But honestly, can't think of too much else apart from that.

The performances are incredible across the board. Cillian Murphy should be a top contender for best actor. The guy has been excellent in supporting roles for a while, but he kills it here. Apart from scenes from the Lewis Strauss confirmation hearing, he is on screen for every scene. RDJr finally breaks out of his Tony Stark skin and delivers a superb turn here. He really bursts into top gear in the final act of the film. Emily Blunt is lovely. She is largely in the background but she shines superbly when she has to be front and center towards the end. Matt Damon is immensely likable as Leslie Groves, one of Oppenheimer's true supporters outside of the scientific community. The film is littered with so many other excellent performances. Benny Safdie as Edward Teller, Josh Hartnett as Ernest Lawrence, Kenneth Branaugh as Niels Bohr, Jason Clarke as Roger Robb, Tom Conti as Albert Einstein, Florence Pugh as Jean Tatlock, and David Krumholtz as Isidor Isaac Rabi are all highlights in the movie. Casey Affleck walks in for a couple of scenes and sent chills down my spine with his performance. Alden Ehrenreich has a superb mini arc of his own as aide to Strauss and he has some of the most satisfying scenes in the movie where he converts to an Oppenheimer supporter as he figures out the things Strauss has done. But there are so many excellent performances in this movie that I could go on and on.

As a director, Nolan has really outdone himself. I can't make an assessment as to where this film lands in Nolan's filmography but it is towards the top of an already excellent set of films. I suspect nothing will outdo TDK trilogy and Inception for me, but this might land right behind those. All in all, a 9/10 movie.

#barbenheimer#oppenheimer#christopher nolan#cillian murphy#robert downey jr#emily blunt#matt damon#benny safdie#alden ehrenreich#florence pugh#david krumholtz#kenneth branagh#josh hartnett#jason clarke#robert oppenheimer#kitty oppenheimer#leslie groves#lewis strauss#jean tatlock#ernest lawrence#casey affleck#niels bohr#albert einstein#tom conti#isidor isaac rabi#edward teller

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

Left: New York Times journalist William Laurence and J. Robert Oppenheimer at the Trinity site in September 1945. Right: Oppenheimer and General Leslie Groves examining the Trinity detonation site after the successful detonation

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tina Cordova and her mother, Rosalie, relax at Bonito Lake, New Mexico, in 1960. Cordova says the lake—which lies within the estimated radioactive fallout zone—was a water source for area towns, including Carrizozo, Alamogordo, and Ruidoso. Courtesy of Anastacio and Rosalie Cordova

U.S. Lawmakers Move Urgently to Recognize Survivors of the First Atomic Bomb Test

The 1945 Trinity test produced heat 10,000 times greater than the surface of the sun and spread fallout across the country.

— By Lesley M.M. Blume | Published September 21, 2021 | July 29th, 2023

Barbara Kent joined Carmadean’s dance camp in the desert near Ruidoso, New Mexico, in the summer of 1945. During the day, she and nine other girls learned tap and ballet. At night, they slept in a cabin by a river. Early in the morning on July 16, 1945, Kent says that she —then 13—and the other campers were jolted out of their bunk beds by what felt like an enormous explosion nearby. Their dance instructor rushed the girls outside, worried that a heater on the premises might have burst.

“We were all just shocked … and then, all of a sudden, there was this big cloud overhead, and lights in the sky,” Kent recalls. “It even hurt our eyes when we looked up. The whole sky turned strange. It was as if the sun came out tremendous.”

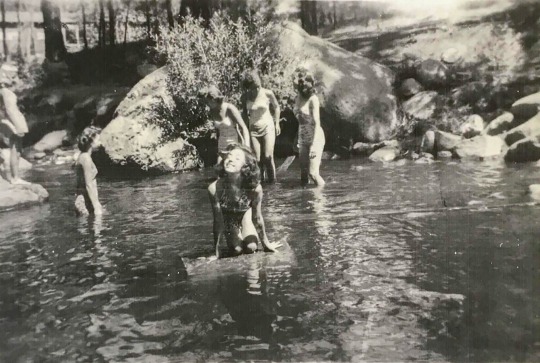

A few hours later, she says, white flakes began to fall from above. Excited, the girls put on their bathing suits and, amid the flurries, began playing in the river. “We were grabbing all of this white, which we thought was snow, and we were putting it all over our faces,” Kent says. “But the strange thing, instead of being cold like snow, it was hot. And we all thought, ‘Well, the reason it’s hot is because it’s summer.’ We were just 13 years old.”

Thirteen-year-old Barbara Kent (center) and her fellow campers play in a river near Ruidoso, New Mexico, on July 16, 1945, in the hours after the bomb’s detonation. Fallout flakes drifted down that day and for days afterward. “We thought [it] was snow," Kent says. “But the strange thing, instead of being cold like snow, it was hot." Courtesy of Barbara Kent

The flakes were fallout from the Manhattan Project’s Trinity test, the world’s first atomic bomb detonation. It took place at 5:29 a.m. local time atop a hundred-foot steel tower 40 miles away at the Alamogordo Bombing and Gunnery Range, in Jornada del Muerto valley.

The site had been selected in part for its supposed isolation. In reality, thousands of people were within a 40-mile radius, some as close as 12 miles away. Yet all those living near the bomb site weren't warned that the test would take place. Nor were they evacuated beforehand or afterward, even as radioactive fallout continued to drop for days.

The Trinity test took place at 5:29 a.m. local time on July 16, 1945. It was three to five times more powerful than its creators had anticipated, producing heat 10,000 times greater than the surface of the sun. The explosion cloud may have reached a height of 70,000 feet. Photograph By Science History Images/ Alamy

In 1990, the U.S. Congress passed the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act (RECA), which has since dispensed over two billion dollars to more than 45,000 nuclear workers and “downwinders”—a term describing people who have lived near nuclear test sites conducted since World War II and may have been exposed to deadly radioactive fallout.

But those exposed during the Trinity test and its aftermath have never been eligible.

For years, Senator Ben Ray Lujan, a Democrat from New Mexico, and other members of Congress have attempted to amend RECA, due to expire on July 11, 2022. In light of this looming deadline, on September 22, Lujan, along with Senator Mike Crapo, Republican of Idaho, and eight co-sponsors introduced Senate bill S. 2798 to extend RECA and expand it to make those in the estimated Trinity fallout zone eligible, as well as other downwinder communities in Colorado, Idaho, and Montana. The proposed legislation also would expand eligibility for people who have worked in uranium mines and mills or transported uranium ore. Also on September 22, Representative Teresa Leger Fernandez and 15 co-sponsors introduced a similar bill, H.R. 5338, in the House.

The plutonium bomb—nicknamed the Gadget—was set atop this hundred-foot steel tower, which vaporized in the explosion. "From the Trinity test,” a 2010 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention report noted, “it was learned that detonating a nuclear explosive device [that] close to the ground increases the radioactive fallout from the event." Photograph Via CORBIS/Getty

Manhattan Project leaders—including General Leslie Groves (center) and, to his right, physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer—scrutinize the remnants of the tower at ground zero. Upon seeing the detonation, Oppenheimer thought of a line from the Bhagavad Gita: "Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds." Photograph Via CORBIS/Getty

“The fact that there had not been a recognition of the impact of the very first atomic detonation in New Mexico was really simply wrong,” says Representative Teresa Leger Fernandez, a Democrat from New Mexico and co-sponsor of the House bill. “We hear their voices, we see their pain, and we must act.”

This is an especially urgent and consequential moment for those living in Trinity’s estimated fallout zone—some of whom have been waiting 76 years to be acknowledged. “We have been denied justice long enough,” says Bernice Gutierrez, who was a newborn when the bomb exploded. Her family lived in Carrizozo, about 50 miles from the blast site. “It’s not like we haven’t given our all to our country. What more can you give?”

‘A Very Serious Hazard’

The blast from the plutonium implosion device, nicknamed the Gadget, produced heat 10,000 times greater than the surface of the sun and was significantly more powerful than its creators had expected. It carried aloft hundreds of tons of irradiated soil and sent a mushroom cloud up to 70,000 feet in the sky. In this experimental atomic detonation, only three of the 13 pounds of plutonium at the bomb’s center underwent fission. The rest dispersed in the fallout cloud.

A tiny fraction of that three pounds of plutonium—about the weight of a raisin—was enough to release “three times the destructive force of the largest conventional bomb used in World War II,” says Robert Alvarez, associate fellow at the Institute of Policy Studies and former senior policy advisor to the U.S. Secretary of Energy. (The Gadget released an explosive force equivalent to about 21,000 tons of TNT.)

Right after detonation, the cloud divided into three parts. One part drifted east, another to the west and northwest, and the rest to the northeast, across a region a hundred miles long and 30 miles wide, “dropping its trail of fission products” the entire way, according to a 2010 report by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The fallout eventually spread over thousands of square miles and was detected as far away as Rochester, New York.

Nineteen counties in New Mexico were in the downwind area, including 78 towns and cities, and dozens of ranches and pueblos. Radiation levels near homes in some “hot spots” reached levels “almost 10,000 times what is currently allowed in public areas,” according to the CDC.

“There is still a tremendous quantity of radioactive dust floating in the air,” wrote Stafford Warren to U.S. Army General Leslie R. Groves, head of the Manhattan Project, five days after the blast. Warren, the project’s chief medical officer, added that “a very serious [radiation] hazard” existed within a 2,700-square-mile area downwind of the test.

He also advised that future atomic tests be done only where there were no people within a radius of 150 miles. (Nearly half a million people in New Mexico, Texas, and Mexico lived within a 150-mile radius of the Trinity test.)

“We didn’t know what the hell we were doing,” Louis Hempelmann—the director of the Los Alamos Health Group, a team tasked with managing radiation within the Manhattan Project—reflected in a 1986 interview uncovered by sociologist James L. Nolan, Jr., in his book Atomic Doctors. “Nobody had had any experience like this before, and we were just hoping that the situation wouldn’t get terribly sticky.”

The leaders of the Manhattan Project knew that civilians had been “probably overexposed,” Hempelmann said. “But they couldn’t prove it and we couldn’t prove it. So we just assumed that we got away with it.”

Many civilians living within the estimated fallout zone were unwittingly exposed and sickened. According to Alvarez, even minute quantities of plutonium can inflict disease. “Particles of plutonium less than a few microns in diameter can penetrate deep in the lungs and lymph nodes and can also be deposited via the bloodstream in the liver, on bone surfaces, and in other organs,” he says. “If inhaled, extremely small amounts can lead to cancer.”

How is it, asks Senator Lujan, that RECA covered people living downwind of the Nevada Test Site but left out “the community where the first nuclear bomb was tested on American soil? There’s not been a good answer given to me nor to the downwinders in New Mexico. There’s no question of the exposure that resulted from the Trinity test.”

The explosion seared the desert sand surrounding the tower into a green, glass-like substance, named Trinitite. Photograph Via Bettmann/Getty

Something Felt Terribly Awry

Several people living near the test site later reported that they thought they were experiencing the end of the world. The strange, snowlike substance that fell from the sky for days coated everything: orchards, gardens, livestock, as well as cisterns, ponds, and rivers—the main sources of drinking water because local groundwater was “unsuitable for human consumption,” according to the 2010 CDC report.

One family in Oscuro, New Mexico, about 45 miles from the site, hung wet bedsheets in their windows against the fallout. They felt that something was terribly awry when their chickens and their dog died. Thirty miles away from ground zero, along Chupadera Mesa, burns appeared on the hides of cattle, whose fur eventually grew back gray and white in the burned patches.

A health care provider in Roswell, a hundred miles away, noted a surge in infant deaths there—35 in August 1945 alone. When she wrote to Warren, stating her concerns, his medical assistant replied that there were no “pertinent data” and assured her that “the safety and health of the people at large is not in any way endangered.”

“They Lied To Us. I Didn’t Learn The Truth Until Years Later.” — BatbaraKent, Trinity Test Survivor

For General Groves, getting the bomb ready—in secrecy—for wartime use had trumped all other considerations, including public safety.

Yet he realized that a blast whose flash was seen in at least three states and two countries could not be wholly concealed. He ordered the commanding officer of the Alamogordo Air Base to feed a cover story to the Associated Press that “a remotely located ammunition magazine containing a considerable amount of high explosives and pyrotechnics exploded.” There had been, the report went on, “no loss of life or injury.” Local newspapers reprinted the announcement without challenge.

Barbara Kent recalls that the day after the explosion, her camp’s dance instructor took the girls into Ruidoso, where government officials were to make an announcement about the source of the blast.

“It was so crowded downtown—everyone was shoulder to shoulder,” Kent says. “What they told us—there was an explosion at a dump. They said, ‘No one worry about anything, everything’s fine, just go along with your own business.’ Everyone was confused. Some people believed it, but some people thought they couldn’t imagine that a dump explosion would do this." She continues: "They lied to us. I didn’t learn the truth until years later.”

As time passed, Kent says she began to hear disturbing reports that her fellow campers were falling ill. By the time she turned 30, she says, “I was the only survivor of all the girls at that camp.” She adds that she has suffered from lifelong illnesses: She had to have her thyroid removed and has survived several forms of cancer, including endometrial cancer and “all kinds of skin cancers.”

In this photograph from 1962, three-year-old Tina Cordova (bottom right) is pictured with her father, Anastacio (holding her baby brother, Matthew), and mother Rosalie. The young family lived in Tularosa, about 40 miles from the blast site. Everything they ate, Tina recalls, “was raised or grown or hunted," adding that the bomb’s “ash got everywhere, in the soil, in the water—everything was contaminated." She says her mother and father developed cancers, and she was diagnosed with thyroid cancer when she was 39. Courtesy of Anastacio and Rosalie Cordova

Tina Cordova is a fifth-generation resident of Tularosa, about 40 miles from the blast site. Thanks to an extensive ditch system in the area, the town was an oasis in the desert, and Cordova’s family’s home, like many others, had an orchard and garden.

“You could literally go out into your yard in the summer and eat peaches, apricots, cherries, figs, dates, pecans, walnuts—everything you could think of,” she says. Local people harvested and canned their fruit and collected rainwater for drinking from rooftop cisterns. Milk came from local dairies. People made their own butter and butchered farmyard animals or hunted wild animals for meat, including deer, quail, rabbit, and pheasant.

“Everything that people were consuming in 1945 was contaminated,” Cordova says. “But they didn’t know [the fallout was] dangerous. They went about their lives.”

After the test, she says, health problems began to plague her family, all of whom lived in and around Tularosa. According to Cordova, two of her great-grandfathers died of stomach cancer, and both of her grandmothers developed cancer. Two aunts had breast cancer, and one died from it. A cousin developed a brain tumor. Her mother had mouth cancer, and her sister has skin cancer. Her father, who was four at the time of the blast, suffered from various cancers, including prostate cancer and tongue cancer. Doctors had to remove part of his tongue and his lymph nodes. The cancer eventually spread to his neck and became inoperable. Cordova says he weighed about 125 pounds at his death in 2013 at the age of 71. She says that she herself was diagnosed with thyroid cancer in 1997, when she was 39.

‘When Are They Going To Hold Our Government Accountable?’

After the U.S. leveled Hiroshima with a uranium bomb on August 6, 1945, the secret history of the creation of atomic weapons was released and widely publicized. Many New Mexicans now realized that the blast that had shattered their windows and blanketed their homes in warm ash was not, after all, an ammunition dump explosion. Although they still hadn't been informed by the government about the nature of that ash or monitored for adverse health effects, they were encouraged to be proud of the part they’d unknowingly played in bringing about the dramatic new atomic age.

“When I was a child, the government fed us propaganda about how much pride we should take in the part we played in ending World War Two,” Cordova says. “We still did not know what that meant from a health consequence perspective. Our mom actually took us to the [Trinity] site for a picnic. We brought home as much Trinitite as we could and played with it.” (The Trinity Site is now a National Historic Landmark, open to visitors twice a year, and anyone can go online and buy radioactive fragments of Trinitite—a green glass created from sand and other materials that melted in the immediate blast zone.)

The U.S. Army erected this monument at ground zero in 1965. Ten years later, the National Park Service designated Trinity Site as a National Historic Landmark. It’s open to visitors twice a year, on the first Saturdays in April and October. Photograph By Tony Korody, SYGMA Via Getty

In 2004, Cordova read a letter from another Tularosa resident, Fred Tyler, to the editor of a local newspaper. She says that the letter changed her life. “He said, ‘When are they going to hold our government accountable for the damage they did to us?’ ” Cordova says. “I called him and said, ‘I feel the same way you do. It’s time to start an organization to more fully push the government about this issue.’ ”

In 2005, Cordova and Tyler founded the Tularosa Basin Downwinders Consortium (TBDC) as an advocacy organization for Trinity test downwinders.

At that time, she recalls, they weren’t aware that the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act had been in place for 15 years and already had provided onetime, $50,000 compensation to other downwinders who “may have developed cancer or other specified diseases after being exposed to radiation from atomic weapons testing or uranium mining, milling, or transporting.” Downwinder eligibility initially was limited to those within specified areas around the Nevada Test Site, 65 miles north of Las Vegas, where a hundred aboveground tests were conducted before a moratorium on atomic testing took effect in 1992.

In 2000, an amendment to RECA expanded eligibility to include some uranium miners and millers in New Mexico. Military and government workers who were “on-site participants” in the Trinity test were also eligible for compensation, but civilian downwinders remained ineligible.

Cordova, like Senator Lujan, says she has “never been able to get a straight answer” about why civilian downwinders were excluded from the legislation: “Even from people who were serving in Congress at the time, I’ve been told, ‘Well, no one was connecting the dots that anybody was harmed.’ ”

Bill Richardson—a Democrat who served as New Mexico’s governor from 2003 to 2011 and was a representative for the state’s Third Congressional District in 1990 when RECA was enacted—says, “I don’t think there was opposition [to their inclusion], just perhaps a lack of awareness. I didn’t know about their claims until I started reading about it when I was governor, and I was sympathetic.”

To raise awareness, Cordova and her colleagues at the consortium began to gather testimonies from and distribute health surveys to downwinders who were alive at the time of the Trinity test, along with their descendants who have lived in areas surrounding the test site. To date, the consortium has collected more than 1,000 surveys, and Cordova says that 100 percent of those questioned describe adverse health conditions—from thyroid disease to brain cancer—that can result from radiation exposure. Often participants describe similar cancers that have ravaged many family members over several generations.

‘A Now-or-Never Moment’

Cordova describes this effort to extend and expand RECA as a “now-or-never moment.” Senator Mike Crapo, an Idaho Republican and co-sponsor of the Senate bill, says there’s a “dire need for Congress to extend RECA … [and] to include victims in states across the West.”

“It is beyond time for the federal government to right a past wrong that caused harm to countless innocent Americans,” he wrote in a letter on March 24, 2021, to the chairman and members of the House Judiciary Committee.

“We Hear Their Voices, We See Their Pain, and We Must Act.” — TeresaLeger Fernandez, Representative to Congress, New Mexico

“When [RECA] was first introduced, no one considered the impact on the first downwinders,” Representative Fernandez says. “But we are in a place now where we recognize an injustice when we see it.” Her family lived in San Miguel and Guadalupe Counties in New Mexico, areas of potential exposure. She says her mother and sister—both nonsmokers—died of lung cancer. Her father died of esophageal cancer, she says, and her grandmother, who grew up near the Trinity site, died of leukemia.

Fernandez and Lujan say they’re also going to push for new epidemiological and environmental studies of the Trinity test’s aftermath and possible long-term effects.

Assessing Trinity’s exact “fingerprint” based on current fallout levels is “complicated and subject to large uncertainties,” says health physicist Joseph Shonka, co-author of the 2010 CDC report. He notes that residents of New Mexico have higher positive plutonium levels in their tissues than residents of any other state but says that tracing those levels back specifically to Trinity fallout might be difficult.

New Mexicans also may have internalized plutonium from various additional sources, he says, including general global fallout, releases from New Mexico’s Los Alamos plutonium operations, and fallout that drifted down from Nevada’s Test Site. The CDC recommended prioritizing Trinity’s aftermath for future studies.

Last year, the National Cancer Institute (NCI) released its findings from a nearly seven-year study of the Trinity nuclear test. The study’s lead investigator, Steven Simon, calls it the “most comprehensive study conducted on the Trinity test and its possible ramifications for cancer risks in the estimated fallout area.”

The researchers concluded that up to a thousand people may have developed cancer from the Trinity test fallout and that “only small geographic areas immediately downwind to the northeast received exposures of any significance.” They also said that the “plutonium deposited as a result of the Trinity test was unlikely to have resulted in significant health risks to the downwind population.”

The researchers also acknowledged their study’s limitations. Calculating exposure for those alive at the time of the detonation is “complex and is subject to uncertainties,” Simon explains, “because all of the needed data is not available."

Shonka says the new NCI study “failed to address early fallout adequately.” He says he questions some of the methodology and is preparing a counter-article addressing what he says are inconsistencies with previous findings. Other critics of the NCI study say it doesn’t address ongoing family cancer clusters and the reported 1945 spike in infant deaths in the region, documented in a 2019 paper in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, co-authored by Robert Alvarez.

The NCI responds that its researchers focused on exposures received among “New Mexico residents alive at the time of the test,” and that they didn’t investigate the infant mortality because it was “not a cancer effect.”

Senator Lujan calls the NCI study “limited” and says that he wants to “make sure that there’s accurate data that truly is looking at the exposure that families face.”

“How can someone say that families in proximity to a nuclear blast were not exposed?” he asks. “It goes against everything that I’ve learned and data sets that I’ve seen from different parts of the world where this has happened, whether it’s been from meltdown of nuclear energy generation facilities or where weapons were deployed.”

Lujan continues, “People died as a result of the Trinity test—that’s a fact. People are still suffering—that’s a fact. The U.S. needs to come forward to address this liability, this wrong.”

Cordova says she and her community will be closely watching the RECA bills’ progress. The new legislation asks to expand compensation for individuals from $50,000 to $150,000. But beyond financial restitution, Cordova says, they’re also hoping simply for a government apology.

“We’ve never had an opportunity to live normal lives,” she says. “They can never say that they didn’t know ahead of time that radiation was harmful or that there was going to be fallout. We don’t ask if we’re going to get cancer; we ask when it’s going to be our turn. We are the forgotten collateral damage.”

— Lesley M. M. Blume is a New York Times best-selling historian, journalist, and author of Fallout: The Hiroshima Cover-up and the Reporter Who Revealed It to the World.

#United States 🇺🇸#US Lawmakers#Atomic Bomb 💣#Survivors#Lesley M.M. Blume#Barbara Kent#Ruidoso New Mexico#Manhattan Project’s Trinity Test#Alamogordo Bombing and Gunnery Range#Jornada del Muerto Valley#U.S. Congress#Radiation Exposure Compensation Act (RECA)#Two Billion Dollars 💵#Downwinders#New Mexico’s Senator Ben Ray Lujan (D)#Senator Mike Crapo (R—Idaho)#Rep. Teresa Leger Fernandez#Colorado Idaho and Montana#General Leslie Groves#J. Robert Oppenheimer#Serious Hazard#Louis Hempelmann#Los Alamos Health Group#Sociologist James L. Nolan Jr.#Terribly Awry#Government Accountable#Trinity Site#National Historic Landmark#Bill Richardson Governor New Mexico (D)

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

'Oppenheimer has become the highest-grossing biopic of all time, surpassing previous record-holder Bohemian Rhapsody.

The Christopher Nolan film, which was released in July, follows the story of J. Robert Oppenheimer – dubbed the “father of the atomic bomb” – and the secretive Manhattan Project which created the first nuclear weapons during World War 2.

The feature has now grossed more than $912.7million (£736million) at the global box office, taking it past Queen biopic Bohemian Rhapsody‘s $910.8million (£734.5million) haul to make it the most successful biopic at the box office.

Bohemian Rhapsody was released in 2018 and stars Rami Malek (who also appears in Oppenheimer as nuclear physicist David L. Hill) as Freddie Mercury – a role for which he won the Academy Award for Best Actor.

Oppenheimer has already broken a number of box office records throughout its run, recently becoming the most successful World War 2-related film ever, and is the third highest-grossing film of 2023 behind Barbie and The Super Mario Bros. Movie.

It is also director Nolan’s third highest-grossing film behind Batman blockbusters The Dark Knight and The Dark Knight Rises.

Oppenheimer stars Cillian Murphy as the central character, with Emily Blunt as Kitty Oppenheimer, Matt Damon as General Leslie Groves, Robert Downey Jr. as Lewis Strauss and Florence Pugh as Jean Tatlock.

In NME‘s five-star review of the film, we said: “Not just the definitive account of the man behind the atom bomb, Oppenheimer is a monumental achievement in grown-up filmmaking.

“For years, Nolan has been perfecting the art of the serious blockbuster – crafting smart, finely-tuned multiplex epics that demand attention; that can’t be watched anywhere other than in a cinema, uninterrupted, without distractions. But this, somehow, feels bigger.”'

#Oppenheimer#Christopher Nolan#Cillian Murphy#Emily Blunt#Kitty#Matt Damon#Leslie Groves#Robert Downey Jr.#Lewis Strauss#Florence Pugh#Jean Tatlock#Rami Malek#The Dark Knight#The Dark Knight Rises#Bohemian Rhapsody#The Manhattan Project#David Hill#Queen

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

In this rare interview, J. Robert Oppenheimer talks about the organization of the Manhattan Project and some of the scientists that he helped to recruit during the earliest days of the project. Oppenheimer discusses some of the biggest challenges that scientists faced during the project, including developing a sound method for implosion and purifying plutonium, which he declares was the most difficult aspect of the project. He discusses the chronology of the project and his first conversation with General Leslie Groves. Oppenheimer recalls his daily routine at Los Alamos, including taking his son Peter to nursery school.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Manhattan Project // Spencer Reece

First, J. Robert Oppenheimer wrote his paper on dwarf stars—“What happens to a massive star that burns out?” he asked. His calculations suggested that instead of collapsing it would contract indefinitely, under the force of its own gravity. The bright star would disappear but it would still be there, where there had been brilliance there would be a blank. Soon after, workers built Oak Ridge, the accumulation of Cemesto hutments not placed on any map. They built a church, a school, a bowling alley. From all over, families drove through the muddy ruts. The ground swelled about the ruts like flesh stitched by sutures. My father, a child, watched the loads on the tops of their cars tip. Gates let everyone in and out with a pass. Forbidden to tell anyone they were there, my father’s family moved in, quietly, behind the chain-link fence. Niels Bohr said, “This bomb might be our great hope.” My father watched his parents eat breakfast: his father opened his newspaper across the plate of bacon and eggs, his mother smoked Camel straights, the ash from her cigarette cometing across the back of the obituaries. They spoke little. Increasingly the mother drank Wild Turkey with her women friends from the bowling league. Generators from the y-12 plant droned their ambition. There were no birds. General Leslie Groves marched the boardwalks, yelled, his boots pressed the slates and the mud bubbled up like viscera. My father watched his father enter the plant. My shy father went to the library, which was a trailer with a circus tent painted on the side. There he read the definition of “uranium” which was worn to a blur. My father read one Hardy Boys mystery after another. It was August 1945. The librarian smiled sympathetically at the 12-year-old boy. “Time to go home,” the librarian said. They named the bomb Little Boy. It weighed 9,700 pounds. It was the size of a go-kart. On the battle cruiser Augusta, President Truman said, “This is the greatest thing in history.” That evening, my father’s parents mentioned Japanese cities. Everyone was quiet. It was the quiet of the exhausted and the innocent. The quietness inside my father was building and would come to define him. I was wrong to judge it. Speak, Father, and I will listen. And if you do not wish to speak, then I will listen to that.

#poetry#Spencer Reece#American poetry#Manhattan Project#J. Robert Oppenheimer#Oppenheimer#Niels Bohr#Truman#war crimes#Hiroshima#Nagasaki#suffering#war#nuclear bomb#fathers & sons

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

butterflypoo69

•10 mo. ago

From "thebulletin.org" -

"The Gilbert U-238 Atomic Energy Lab was an actual radioactive toy and learning set sold in the early 1950’s. The $49.50 set came with four samples of uranium-bearing ores (autunite, torbernite, uraninite, and carnotite), as well as a Geiger-Mueller radiation counter and various other tools.The set also came with a comic book featuring Dagwood from the popular Blondie comic strip. It was titled "Learn How Dagwood Splits the Atom" and written in conjunction with General Leslie Groves, director of the Manhattan Project.Radar Magazine dubbed the Atomic Energy Lab one of "the 10 most dangerous toys of all time" in 2006."

FYI the $49.50 price tag in 1950 equates to @$612.00 today, which made this an expensive toy for some lucky boys and girls :)

10 notes

·

View notes