#frederik van valckenborch

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Title: Stormy Landscape with Houses

Artist: Frederik van Valckenborch (1566-1623)

Age: ca. 1605–1610

Location: Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest

#art#paintings#renaissance#frederik van valckenborch#17th century#1600s#flemish culture#dutch culture#his landscape paintings have such dynamism in them

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

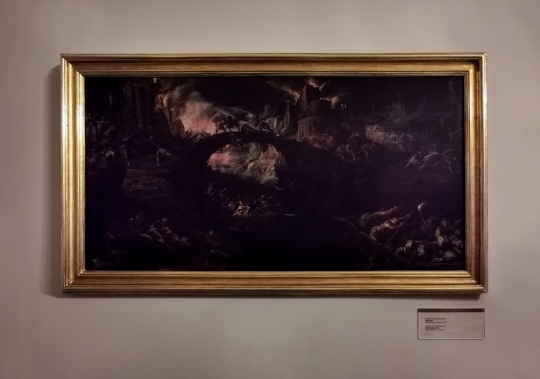

The Burning of Troy, Nuremberg (?), ca. 1610 — Frederik van Valckenborch (Flemish, 1566-1623)

#frederik van valckenborch#painting#baroque art#idk#dark academia#one of my favourite paintings ever#couldn't find any pictures of it on the internet so i'm posting the pic i took this summer#if you see this please reblog i NEED more people to know about this paintingggg#thx c:#🦷

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tower of Babel. Frederik van Valckenborch ~ ca.1600 Kunsthistorisches Museum Wien

0 notes

Photo

Jesus Walking on the Sea of Galilee, Paul Bril and Frederik van Valckenborch, 1590s

#art#art history#Paul Bril#Frederik van Valckenborch#Northern Renaissance#Flemish Renaissance#religious art#Biblical art#Christian art#New Testament#Gospels#landscape#landscape painting#Italianate#veduto#vedutismo#vedutisti#Flemish art#16th century art#Museum of John Paul II

282 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Joos van Winghe - Religious wars between Catholics and Protestants or Procession of the League in 1590 or 1593 -

Joos van Winghe, Jodocus a Winghe or Jodocus van Winghen (1544–1603) was a Flemish painter and print designer. He is known for his history paintings, portraits, allegories and genre scenes, including merry companies. He worked in Brussels as court painter and left Flanders after the Fall of Antwerp in 1584. He then worked in Frankfurt for the remainder of his career. In Germany he enjoyed the patronage of Holy Roman emperor Rudolf II and adopted a more clearly Mannerist style.

The principal source on the life of Joos van Winghe is the Flemish contemporary art historian and artist Karel van Mander. Modern art historians treat van Mander's biographies of artists with circumspection. Van Mander recounts that van Winghe was born in Brussels in 1544. There is no independent information which can confirm this birth date.

Van Mander states that van Winghe traveled to Italy to further his studies. In Rome he lived with a cardinal for four years. Van Winghe spent time in Parma where he reportedly painted a fresco of the Last Supper in the refectory of the monastery of the Servites. He worked in the workshop of the Italian Mannerist painter Jacopo Bertoja who also employed the Flemish painter Bartholomaeus Spranger. Bertoja took van Winghe and Spranger to paint in the rooms of the Villa Farnese that he had been commissioned to finish. He also worked in Rome and Parma for Bertoja. A close friendship between Spranger and van Winghe must have developed during their time in Italy. A drawing by Spranger after a painting van Winghe, which has disappeared today, proves that the two artists remained in contact decades later, when Spranger had been court painter to Rudolph II in Prague for many years and van Winghe had settled in Frankfurt.

On his return trip he passed by Paris. He spent time at Fontainebleau where he was exposed to the Mannerist style of the School of Fontainebleau. His period of travel is situated between 1564 and 1568. Flemish painter Hendrick de Clerck may have been van Winghe's pupil during his stay in Italy.

After his return to Brussels in 1568 he became court painter to Alexander Farnese, Duke of Parma, then the governor-general of the Spanish Netherlands. He created a number of religious compositions during his stay in Brussels. He married with Catharina van der Borcht, who was a member of the van der Borcht family of painters. Their son Jeremias van Winghe later became a painter. He left his home country with his family in 1584 after the Fall of Antwerp and his position as court painter was taken up by Otto van Veen. The fact that he left Flanders after the recapturing of Antwerp indicates that he was a Protestant. A painted allegory described by van Mander depicting a chained personification of Belgica, i.e. the Netherlands, supports the view that his emigration was politically motivated.

He settled in Frankfurt, where he became a citizen (burgher) in 1588. In Frankfurt he was part of the large contingent of Flemish artists who had left their home country for religious reasons, such as Hans Vredeman de Vries, Marten van Valckenborch and his sons Frederik van Valckenborch and Lucas van Valckenborch, Joris Hoefnagel and Jacob Hoefnagel. There were also a great number of Flemish printmakers in Frankfurt. Many of the artists were tied together through a network of family relationships established through intermarriage. The exiled artists regularly worked together on projects where each artist would contribute to a painting the portion in which they were specialised. For instance, a figure painter and still life painter would contribute respectively the figures and still life elements in a painting. The artists would also provide designs for the publications engraved by the Flemish printmakers established in Frankfurt. Van Winghe further maintained close relations with the group of Flemish artists in Frankenthal through Hendrik Gijsmans, with whom he was related by marriage, through his younger brother Maximilian van Winghe, who lived in Frankenthal and through his marriage to Catharina van der Borcht, which connected him with the painter family of van der Borcht. Van Winghe likely enjoyed the patronage of Holy Roman emperor Rudolf II thanks to his friend Spranger who was court painter. Spranger may have been instrumental in the purchase of van Winghe's painting Apelles paints Campaspe before Alexander for the imperial collection and a series of twelve apostles designed by him, which was dedicated to Archbishop Berka in Prague.

He was the father of the painter Jeremias van Winghe who remained active in Frankfurt.

He died in Frankfurt in 1603.

18 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Tower of Babel (detail). Circle of Frederik van Valckenborch (Antwerp 1570-1623 Nuremberg) Bonhams Auctions • via Bibliothèque Infernale on FB

34 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Construction of the Tower of Babel

- Frederik van Valckenborch

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Mountainous Landscape by Frederik van Valckenborch, 1605, Museum of the Netherlands

Bergachtig landschap met in het midden een rivier tussen rotsen. Links op de voorgrond worden enkele boeren onderweg naar de markt door rovers overvallen, op de achtergrond een galg en een rad. Rechts een steile berghelling waartegen huizen en bruggen zijn gebouwen.

https://www.rijksmuseum.nl/nl/collectie/SK-A-1506

20 notes

·

View notes

Photo

View of a Moated City in a Hilly Landscape, Frederik van Valckenborch, 16th-17th century, Harvard Art Museums: Drawings

Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, The Kate, Maurice R. and Melvin R. Seiden Special Purchase Fund in memory of Liliane Soriano and in honor of José Soriano Size: actual: 19.5 x 28 cm (7 11/16 x 11 in.) Medium: Black and brown ink, brown wash, and black chalk on cream antique laid paper, partial framing line in graphite

https://www.harvardartmuseums.org/collections/object/312328

0 notes

Text

Trusting Jesus in the COVID-19 storm

(RNS) — One of my favorite stories in the Gospels is about a storm.

Jesus had just finished feeding thousands of people near the Sea of Galilee by multiplying five loaves of bread and two fish. He told his disciples to go ahead of him to the town of Gennesaret in their boat while he dismissed the crowds. After everyone left, the Gospel of Matthew says, Jesus went up on a mountain to pray.

Jesus was still on the mountain as evening came. His disciples, on the other hand, were in trouble.

As the disciples made for their destination, a raging storm came upon the sea. Their boat “was a long way from the land, beaten by the waves, for the wind was against them.” I can imagine how helpless and hopeless the disciples felt.

Suddenly, the disciples saw a figure coming toward them, walking on the waves. In their terror, they cried out, “It is a ghost!” (As if things weren’t bad enough already.)

But then they heard a familiar voice: “Take heart; it is I. Do not be afraid.”

The Apostle Peter, impulsive man that he was, said, “Lord, if it is you, command me to come to you on the water.”

Jesus simply replied: “Come.”

So Peter got out of the boat. He was walking on the water toward Jesus. But then he looked away.

The wind got his attention, all consuming. And he began to sink.

Panicked, he cried, “Lord, save me!”

Immediately, Jesus grabbed hold of Peter and said, “O you of little faith, why did you doubt?” Then they got back into the boat and the storm was gone.

In our storm, Jesus asks us the same question: “Why do you doubt?”

“Jesus Walking on the Sea of Galilee” painting by Paul Brill and Frederik van Valckenborch, circa 1590. Image courtesy of Creative Commons

This terrible COVID-19 pandemic is like a massive storm. We are afraid and worried about our futures.

Although we might feel forsaken, we are not. I am comforted by this beautiful story, as it reminds me that I can trust God in the storms of my life. Jesus watches us in our storms.

While Matthew tells us that Jesus “went up on a mountainside by himself to pray,” Mark’s Gospel gives us an added detail: “And he saw that they were making headway painfully, for the wind was against them.”

Jesus was watching his disciples not passively, but with great interest. I am sure he was praying for them as well. The disciples may have lost sight of Jesus, but he never lost sight of them.

If you feel you are all alone in this storm and that Jesus can’t see you, remember this: You don’t escape his attention. Indeed, Jesus comes to us in our storms.

Why did Jesus walk on the water to meet his disciples? Why not fly in?

I think it’s because he wanted to show his disciples that the storm was only a staircase for him to come to them — and that he had power over it.

This, however, only freaked the disciples out. They didn’t recognize Jesus because they were not looking for him. Had they been waiting by faith, they would have recognized him immediately.

How often is the Lord speaking, seeking to lead us, but we don’t see him because we don’t expect him?

You may know Jesus, but you will never know him deeply until he comes to you in the midst of the storms of life. It is better to be in a storm with Jesus than anywhere else without him.

It’s hard to remember sometimes that Jesus calls us to keep our eyes on him in the middle of our storms. Peter began to sink because he wasn’t looking at Jesus. That’s just like us.

We are looking to the Lord and then look back to our circumstances as we watch the latest news report or we hear the latest rumor about COVID-19 and our hearts sink.

We all know the feeling of the downward spiral of fear, anxiety and worry. We “start to sink” when we forget God’s promises to us. We forget that he is in control of our lives. Sometimes, we forget God altogether.

Jesus will get us through this storm called coronavirus. But we have to keep our eyes on him or we, like Peter, will sink. Remember: Where fear reigns, faith is driven away. Where faith reigns, fear has no place.

When we are sinking, we need to call out to Jesus.

When Peter started sinking, he shouted, “‘Lord, save me!’”

Scripture reminds us that prayer calmed storms, healed the sick, raised the dead and even stopped time. And the Lord gives us this promise in the words of the Old Testament prophet Jeremiah. “Call to me, and I will answer you and show you great and mighty things, which you do not know,” he says.

If you are afraid, Jesus is waiting for you to call.

Like a storm, COVID-19 has a beginning, middle and end. Perhaps we are somewhere near the beginning or approaching the middle. But the storm will pass, and don’t forget, Jesus is with us in it.

(The Rev. Greg Laurie is the senior pastor of Harvest churches in California and Hawaii and the founder of the Harvest crusades. He is on Twitter at @GregLaurie. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)

This content was originally published here.

0 notes

Photo

Frederik van Valckenborch, The Construction of the Tower of Babel, c. 1600, oil on canvas, 182 x 292 cm., Kunsthistorisches Museum, Wien.

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Detail of the Tower of Babel. Circle of Frederik van Valckenborch (Antwerp, ca.1570–1623 Nürnberg). Bonhams Auctions

0 notes

Photo

¡Hola, Prado! Exhibition Federico Barocci and Frederik van Valckenborch #switzerland #messebasel #basel #cantondebale #bâle #kunstmuseum #kunstmuseumbasel #museumvisitors #kunstmuseumneubau #federicobarocci #frederikvanvalckenborch (à Kunstmuseum Basel)

#basel#kunstmuseum#kunstmuseumneubau#federicobarocci#museumvisitors#frederikvanvalckenborch#kunstmuseumbasel#cantondebale#bâle#switzerland#messebasel

0 notes

Photo

De toren van Babel. Circle of Frederik van Valckenborch (Antwerp ca.1570—1623 Nürnberg) Bonhams Auctions • via Bibliothèque Infernale on FB

25 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Jesus walking on the Sea of Galilee

- Frederik van Valckenborch and Paul Bril

13 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Mountainous Landscape by Frederik van Valckenborch, 1605, Museum of the Netherlands

Bergachtig landschap met in het midden een rivier tussen rotsen. Links op de voorgrond worden enkele boeren onderweg naar de markt door rovers overvallen, op de achtergrond een galg en een rad. Rechts een steile berghelling waartegen huizen en bruggen zijn gebouwen.

https://www.rijksmuseum.nl/nl/collectie/SK-A-1506

11 notes

·

View notes