#duncan waugh

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

HAPPY BIRTHDAY @sigmxnd !!!!!!!!!

I hope you like these and have a great birthday!!!!! You're one of my best friends on this site and i love you /p!!!!! Teehee these were so fun to draw :3

#total drama#td ezekiel#ezekiel tdi#td duncan#duncan tdi#td oc#others ocs#sigmund!!#leo!!#oc x canon#WAUGH I LOVE YOU BRO HAPPY BIRTHDAY!!! /p

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Alastair Graham, one of Evelyn Waugh’s lovers

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

…..January 27, 1897 ~

Remembering English poet IRIS TREE, on her birthday today 🖤

Born into an upper-middle class London family, Tree was a poet, artist’s model, and part-time actress. In the 1920’s, she was a part of the loose group of like-minded bohemians and literati called, by the London media, the “Bright Young Things”. The group included a couple of the Mitford Sisters, Edith Sitwell, Evelyn Waugh, Cecil Beaton, many others, as they drank and debauched themselves across London.

Tree was painted by Modigliani, Augustus John, Duncan Grant and many others; she was sculpted by Jacob Epstein; and she was photographed by Man Ray, among others. Tree had a small role, as a poet, in Fellini’s 1960 classic, “La Dolce Vita”.

Iris Tree died in London of heart failure on April 13, 1968, at the age of 71.

PHOTOS:

L: Iris Tree, by Man Ray, 1920.

R: Iris Tree by Modigliani, c. 1916.

0 notes

Photo

Arthur Adventures (Arthur Kobalewscuy Fashion) DH S1E2: A New Start Part 2 Aired: 1989

So now that we are in high school, will Arthur finally be cool? Well, by the looks of these pleated pants and the fact he’s still stuck on this beret, I think the answer is gonna be no.

*However, if you have never looked up actor Duncan Waugh today, don’t worry, he totally became cool. I’m hoping to do a “where are they now” series maybe after I’m done screen capping Degrassi High.

#arthur kobalewscuy#duncan waugh#degrassi#degrassi fashion#degrassi style#degrassi wardrobe#degrassi high#broomheadz#80s fashion

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Duncan McLaren & George Shaw - 2013

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Act of Valor (2012) Directed by Mike McCoy & Scott Waugh, Cinematography by Shane Hurlbut "Live your life that the fear of death can never enter your heart. Trouble no one about his religion. Respect others in their views and demand that they respect yours. Love your life, perfect your life. Beautify all things in your life. Seek to make your life long and of service to your people. When your time comes to die, be not like those whose hearts are filled with fear of death, so that when their time comes they weep and pray for a little more time to live their lives over again in a different way. Sing your death song, and die like a hero going home."

#scenesandscreens#Mike McCoy#Scott Waugh#act of valor#Rorke Denver#Derick Van Orden#Captain Duncan Smith#Jason Cottle#Roselyn Sanchez#Alex Veadov#Ailsa Marshall#Shane Hurlbut

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

tagged by @maerenee930, thanks darling 😊

I haven’t done this sort of check-in tag thing in a while, so let’s do it.

Three Ships: The Enterprise, The Serenity, and The SSV Normandy? 1) Thief Juice OT3 (Elliot/Parker/Hardison; Leverage) 2) Peaches and Plums Motherfucker (Eliot Waugh/Quentin Coldwater, The Magicians) 3) Myka Bering/H.G. Wells (Warehouse 13)

First Ship: Oh lord. I don’t think I knew what ships were technically, but probably Duncan McLeod x Tessa Noël from Highlander. If not the first, one of the very early ones

Last Song: Wicked Girls ~ Seanan McGuire

Last Film: Ocean’s Eight (10/10)

Currently Reading: The Call to Arms ~ Melissa Croft

Currently Watching: Warehouse 13 (for the who knows how many-th time), Around the World in Eighty Days (I have mixed feelings on David’s moustache)

Currently Consuming: only air, for I am soon to bed.

Currently Craving: I can’t actually think of anything? I’m pretty content right now. Maybe a hug/cuddle. I always crave those.

Tagging (if you want to play): @exlibrisfangirl @redlippedladyofrohan @misskittysmagicportal @forenschik @frogs--are--bitches and anyone else that wants to play along

#I think I make the ship joke every time I play this tag and never use the same 3 ships for it#but it continues to amuse me so...I'm gonna keep doing it#tag game#check in tag game#about me#also this might be the first time I've been able to answer something other than Middlegame#because law school meant it took me a year and a fucking half to read that book#(it was a very good book but I can't believe it took me that long to read it)

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

“...The letters, biographies, memoirs, and diaries that recorded Victorian women’s lives are essential sources for differentiating friendship, erotic obsession, and sexual partnership between women. The distinctions are subtle, for Victorians routinely used startlingly romantic language to describe how women felt about female friends and acquaintances. In her youth, Anne Thackeray (later Ritchie) recorded in an 1854 journal entry how she “fell in love with Miss Geraldine Mildmay” at one party and Lady Georgina Fullerton “won [her] heart” at another. In reminiscences written for her daughter in 1881, Augusta Becher (1830–1888) recalled a deep childhood love for a cousin a few years older than she was: “From my earliest recollections I adored her, following her and content to sit at her feet like a dog.”

At the other extreme of the life cycle, the seventy one-year-old Ann Gilbert (1782–1866), who cowrote the poem now known as “Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star,” appreciatively described “the latter years of . . . friendship” with her friend Mrs. Mackintosh as “the gathering of the last ripe figs, here and there, one on the topmost bough!” Gilbert used similar imagery in an 1861 poem she sent to another woman celebrating the endurance of a friendship begun in childhood: “As rose leaves in a china Jar / Breathe still of blooming seasons past, / E’en so, old women as they are / Still doth the young affection last.” Gilbert’s metaphors, drawn from the language of flowers and the repertoire of romantic poetry, asserted that friendship between women was as vital and fertile as the biological reproduction and female sexuality to which figures of fruitfulness commonly alluded.

Friendship was so pervasive in Victorian women’s life writing because middle-class Victorians treated friendship and family life as complementary. Close relationships between women that began when both were single often survived marriage and maternity. In the Memoir of Mary Lundie Duncan (1842) that Duncan’s mother wrote two years after her daughter’s early death at age twenty-five, the maternal biographer included many letters Duncan (1814–1840) wrote to friends, including one penned six weeks after the birth of her first child: “My beloved friend, do not think that I have been so long silent because all my love is centered in my new and most interesting charge. It is not so. My heart turns to you as it was ever wont to do, with deep and fond affection, and my love for my sweet babe makes me feel even more the value of your friendship.”

Men respected women’s friendships as a component of family life for wives and mothers. Charlotte Hanbury’s 1905 Life of her missionary sister Caroline Head included a letter that the Reverend Charles Fox wrote to Head in 1877, soon after the birth of her first child: “I want desperately to see you and that prodigy of a boy, and that perfection of a husband, and that well-tried and well-beloved sister-friend of yours, Emma Waithman.” Although Head and Waithman never combined households, their regular correspondence, extended visits, and frequent travels were sufficient for Fox to assign Waithman a socially legible status as an informal family member, a “sister-friend” listed immediately after Head’s son and husband.

In A Room of One’s Own, Virginia Woolf lamented that a woman born in the 1840s would not be able to report what she was “doing on the fifth of April 1868, or the second of November 1875,” for “[n]othing remains of it all. All has vanished. No biography or history has a word to say about it.” Yet as an avid reader of Victorian life writing, Woolf had every reason to be aware that in the very British Library where her speaker researches her lecture, hundreds of autobiographies, biographies, memoirs, diaries, and letters provided exhaustive records of what women did on almost every day of the nineteenth century.

One cannot fault Woolf excessively for having discounted Victorian women’s life writing, for even today few consult this corpus and no scholar of Victorian England has used it to explore the history of female friendship. Scholars of autobiography concentrate on a handful of works by exceptional women, and historians of gender and sexuality have drawn primarily on fiction, parliamentary reports, journalism, legal cases, and medical and scientific discourse, which emphasize disruption, disorder, scandal, infractions, and pathology. Life writing, by contrast, emphasized ordinariness and typicality, which is precisely what makes it a unique source for scholarship.

The term “life writing” refers to the heterogeneous array of published, privately printed, and unpublished diaries, correspondence, biographies, autobiographies, memoirs, reminiscences, and recollections that Victorians and their descendants had a prodigious appetite for reading and writing. Literary critics have noted the relative paucity of autobiographies by women that fulfill the aesthetic criteria of a coherent, self-conscious narrative focused on a strictly demarcated individual self. Women’s own words about their lives, however, are abundantly represented in the more capacious genre of life writing, defined as any text that narrates or documents a subject’s life.

The autobiographical requirement of a unified individual life story was irrelevant for Victorian life writing, a hybrid genre that freely combined multiple narrators and sources, and incorporated long extracts from a subject’s diaries, correspondence, and private papers alongside testimonials from friends and family members. A single text might blend the journal’s dailiness and immediacy and a letter’s short term retrospect with the long view of elderly writers reflecting on their lives, or the backward and forward glances of family members who had survived their subjects.

For example, Christabel Coleridge was the nominal author of Charlotte Mary Yonge: Her Life and Letters (1903), but the text begins by reproducing an unpublished autobiographical essay Yonge wrote in 1877, intercalated with remarks by Coleridge. The sections of the Life written by Coleridge, conversely, consist of long extracts from Yonge’s letters that take up almost as much space as Coleridge’s own words. Coleridge undertook the biography out of personal friendship for Yonge, and its dialogic form mimics the structure of a social relationship conducted through conversation and correspondence.

The biographer was less an author than an editor who gathered and commented on a subject’s writings without generating an autonomous narrative of her life. Reticence was paradoxically characteristic of Victorian life writing, which was as defined by the drive to conceal life stories as it was indicative of a compulsion to transmit them. This was true of life writing by and about men as well as by and about women. The authors of biographies often did not name themselves directly. Instead they subsumed their identities into those of their subjects. Authors who knew their subjects intimately as children, spouses, or parents usually adopted a deliberately impersonal tone, avoiding the first person whenever possible.

In her anonymous biography of her daughter Mary Duncan, for example, Mary Lundie completely avoided writing in the first person and was sparing even with third-person references to herself as Duncan’s “surviving parent” or “her mother” (243, 297). The materials used in biographies and autobiographies were similarly discreet, and the diaries that formed the basis of much life writing revealed little about their authors’ lives. Victorian life writers who published diary excerpts valued them for their very failure to unveil mysteries, often praising the diarist’s “reserve” and hastening to explain that the diaries cited did “not pretend to reveal personal secrets.”

Although we now expect diaries to be private outpourings of a self confronting forbidden desires and confiding scandalous secrets, only a handful of authenticated Victorian diaries recorded sexual lives in any detail, and none can be called typical. Unrevealing diaries, on the other hand, were plentiful in an era when keeping a journal was common enough for printers to sell preprinted and preformatted diaries and locked diaries were unusual. Preformatted diaries adopted features of almanacs and account books, and journals synchronized personal life with the external rhythms of the clock, the calendar, and the household, not the unpredictable pulses of the heart.

Diaries were rarely meant for the diarist’s eyes alone, which explains why biographers had no compunction about publishing large portions of their subjects’ journals with no prefatory justifications. Girls and women read their diaries aloud to sisters or friends, and locked diaries were so uncommon that Ethel Smyth, born in 1858, still remembered sixty years later how her elders had disapproved when she started keeping a secret diary as a child. Some diarists even explicitly wrote for others, sharing their journals with readers in the present and addressing them to private and public audiences in the future. By the 1840s, published diaries had created a popular consciousness, and self-consciousness, about the diary form.

In 1856, at age fourteen, Louisa Knightley (1842–1913), later a conservative feminist philanthropist, began to keep journals “written with a view to publication” and modeled on works such as Fanny Burney’s diaries, published in 1842. When the working-class Edwin Waugh began to keep a diary in 1847, his first step was to paste into it newspaper clippings about how to keep a journal. One young girl included diary extracts in letters to her cousin in the 1840s. Princess Victoria was instructed in how to keep a daily journal by her beloved governess, Lehzen, and until Victoria became Queen, her mother inspected her diaries daily.

Diarists often wrote for prospective readers and selves, addressing journal entries to their children, writing annual summaries that assessed the previous year’s entries, or rereading and annotating a life’s worth of diaries in old age. Journals were a tool for monitoring spiritual progress on a daily basis and over the course of a lifetime. Diarists periodically reread their journals so that by comparing past acts with present outcomes they could improve themselves in the future. A Beloved Mother: Life of Hannah S. Allen. By Her Daughter (1884) excerpted a journal Allen (1813–1880) started in 1836 and then reread in 1876, when she dedicated it to her daughters: “To my dear girls, that they may see the way in which the Lord has led me.”

Far from being a repository of the most secret self, the diary was seen as a didactic legacy, one of the links in a family history’s chain. Victorian women’s diaries combined impersonality with lack of incident. Although Marian Bradley (1831–1910) wrote, “My diary is entirely a record of my inner life—the outer life is not varied. Quiet and pleasant but nothing worth recording occurs,” she in fact devoted hundreds of pages to recording an outer life that she accurately characterized as regular and predictable. Indeed, the stability and relentless routine that diaries labored to convey goes far to explain why Victorians were so eager to read the poetry that lyrically expressed spontaneous emotion and the novels that injected eventfulness and suspense into everyday life.

Diaries and novels had common origins in spiritual autobiography, and diaries played a dramatic role in Victorian fiction, but although diaries shared quotidian subjects and diurnal rhythms with novels, they were rarely novelistic. Most diarists produced chronicles that testified to a woman’s success in developing the discipline necessary to ensure that each day was much like the rest, and even travel diaries were filled not with impressions but descriptions similar to those found in guidebooks. When something unusually tumultuous took place, it often interrupted a woman’s daily writing and went unrecorded.”

- Sharon Marcus, “Friendship and the Play of the System.” in Between Women: Friendship, Desire, and Marriage in Victorian England

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

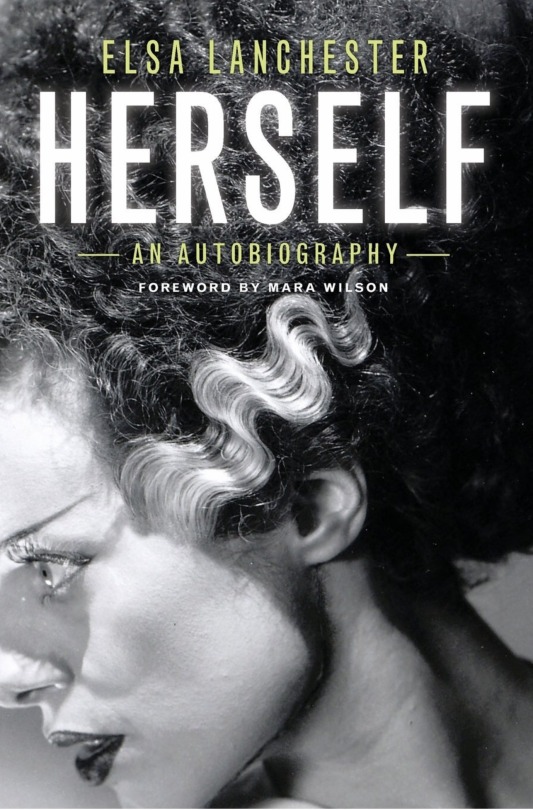

Being known as "The Bride of Frankenstein" is an unusual form of fame, but for Elsa Lanchester the unusual came naturally. Born to radical socialist parents who made civil disobedience a way of life, Elsa attended a Summerhill-like all-boys school and later "studied" in Paris with Isadora Duncan. She returned to London at age thirteen to dance and give lessons in the new style. At seventeen, she opened her own theater. The Cave of Harmony, which was frequented by people such as H. G. Wells, Aldous Huxley, and Evelyn Waugh. She began performing with and then fell in love with an up-and-coming young actor named Charles Laughton. Soon after their marriage he revealed his homosexuality. Though it made their union shaky at times, it did not overshadow their common love of art, music, and nature, and their marriage endured for thirty-six years until Laughton's death.

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

ELSA LANCHESTER

October 28, 1902

Elsa Sullivan Lanchester was born in Lewisham, London. She studied dance in Paris under Isadora Duncan, whom she disliked. When the school was discontinued due to the start of the World War I, she returned to the UK.

“My parents were always a bit arty. They were ‘advanced’. They supported pacifism, vegetarianism, socialism, atheism and all that.” ~ Elsa Lanchester

Her cabaret and nightclub appearances led to more serious stage work and it was then that Lanchester first met actor Charles Laughton. They were married two years later and continued to act together from time to time, both on stage and screen. Lanchester made her film debut in The Scarlet Woman (1925) alongside author Evelyn Waugh.

She was nominated for Academy Awards for Come To The Stable (1949) and Witness for the Prosecution (1957). Her most memorable role, however, was as Mary Shelley and the Monster’s Bride in Bride of Frankenstein (1935), a sequel to James Whale’s Frankenstein (1931). Later in her career she starred in popular comedies like Murder By Death (1976) and musicals like Mary Poppins (1964), among others.

Lanchester made her television debut in “Music and Mrs. Pratt” in October 1953, a production of the “Studio One” anthology series. Lanchester played Mrs. Pratt.

In April 1955, she did a television version of the 1936 play and 1937 film “Stage Door”, which featured Lucille Ball. It was part of “The Best of Broadway” anthology series. Lanchester played Mrs. Orcutt.

“Stardom is all hard work, aspirins and purgatives.” ~ Elsa Lanchester

Lucy fans recognize Lanchester as Edna Grundy, the eccentric woman that Lucy and Ethel share a ride with in “Off To Florida” (ILL S6;E6). The girls think Grundy may be an escaped hatchet murderess and vice versa! Grundy drives off and leaves Lucy and Ethel stranded.

The Oscar-nominated actress received $2,000 for appearing in the episode, just $500 less than she was paid for The Bride of Frankenstein twenty years earlier. In “Lucy Writes a Play” (S1;E17), Ricky jokes that Ethel looks like the Bride of Frankenstein in her Spanish mantilla.

Eighteen years later, Lanchester once again worked with Lucille Ball, this time playing ex-con Mumsie Westcott on a 1973 episode of “Here’s Lucy” “Lucy Goes to Prison” (HL S5;E18). Westcott was the surname of the “Here’s Lucy” props master.

Mumsie is an imprisoned bank robber who has hidden $300,000 but the police don’t know where. The undercover prisoner will receive a reward if they help find the stolen loot and the Unique Employment Agency will get 15% of that fee. The prisoner (Lucy) will receive $400 a week while in the clink, no matter what the outcome. Naturally, Lucy volunteers for the assignment.

Lanchester draws on her early days in the British music hall, singing snatches of songs and little dances, to create this odd, gin-guzzling lady criminal.

Lanchester’s final screen appearance was in 1980 comedy Die Laughing starring Robby Benson.

Her husband, Charles Laughton, died in 1962. Lanchester talked about her open (and child-less) marriage:

“We both needed other company. I met his young men, and I had a young man around and Charles didn't even argue.”

Elsa Lanchester died on Boxing Day 1986.

#Elsa Lanchester#I Love Lucy#Lucille Ball#Here's Lucy#Desi Arnaz#Vivian Vance#Charles Laughton#Bride of Frankenstein#Die Laughing#Off To Florida#Robby Benson#Lucy Goes to Prison#Stage Door#Murder By Death#Mary Poppins#Come to the Stable#Witness for the Prosecution

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

In "How to Disappear: A Memoir for Misfits" (Call #: B F196a) Duncan Fallowell sets out to odd corners of the world in pursuit of some extraordinary and improbable characters who were in most cases momentarily famous--or infamous--and then simply disappeared. The first to disappear is the author himself--to a ghostly hotel on a Mediterranean island. His subjects, though unmet or hardly met, live for the reader with remarkable vividness, such as the German artist who bought a large island in the Hebrides and vanished immediately afterward, to the astonishment of its inhabitants. Fallowell tracks down the recluse who inspired Evelyn Waugh's creation, Sebastian Flyte, the legendary love object of Waugh's novel Brideshead Revisited, who wants both to forget the past and to cling to it. He even pursues the ultimate disappearance--the death of Princess Diana--and the haze of shock, wonder, and grief that followed, writing "Mystification is absolutely essential to our feeling of being alive.

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

i am about to write some awful duncan whump for the hk tag and i wanted to apologize in advance. im sorry for what im about to do to your blorbo

!!!! 👀👀👀 yesssssss but also WAUGH i can't wait :]

1 note

·

View note

Text

Alastair Graham, one of Evelyn Waugh’s lovers

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Arthur Adventures (Arthur Kobalewscuy Fashion) DJH S3E14: Black and White Aired: 1989

Arthur didn’t have much of a presence this episode, but we do see a few seconds of his photoshoot with Yick, in which we wears his Joke Emporium shirt. This shirt only reminds me of how he ran off his almost-stepmom Carol. Nice going Arthur. He’s also got a tiny little baby mullet coming in, so that’s somewhat redeeming.

#Arthur Kobalewscuy#duncan waugh#degrassi#degrassi fashion#degrassi style#degrassi wardrobe#degrassi junior high#djh#broomheadz#80s fashion

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

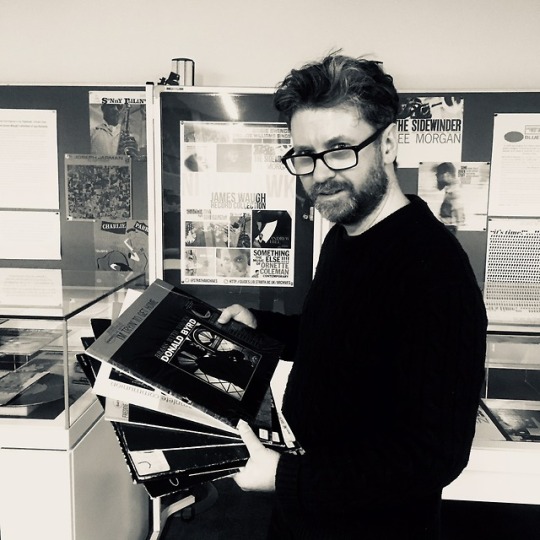

From Civil Engineer to the “Nighthawk” of Radio Clyde

Duncan Birrell, Archive Assistant, takes a closer look at the James Waugh Collection of Jazz Records.

James Waugh (1941-1995) was the immensely talented but always self-effacing presenter of ‘Nighthawk’ on Radio Clyde, the late night Jazz show which aired from Glasgow throughout the 1980s.

The collection of over 2,300 vinyl records of Jazz music collated during Jimmy Waugh's career, was donated to the University of Strathclyde by his widow Genevieve Waugh in 1998. It spans Jazz from its origins in Gospel and Blues, and the inception of rag-time and Dixie-land (or Traditional Jazz) at the turn of the 20th century; includes the Chicago style of the 1920s; follows the Swing of the 30s, the Big Band Jazz and Bebop of the 40s; charts the arrival of Free Jazz in the 1950s, and scopes the avant-garde experiments and break down of Jazz convention which followed in the 1960s; also tracking Jazz fusions incorporation of funk in the 70s and 80s.

All the Jazz legends are here too: from drummers like Buddy Rich, Max Roach, Art Blakey, to percussionists like Bobby Hutcherson; double bassists like Charlie Mingus and Dave Holland; trombonists like Fred Wesley; guitarist such as Grant Green and Kenny Burrell; Jazz organists like Herbie Hancock, Quincy Jones, and Charles Earland; pianists like Andrew Hill; and Jazz violinists like Stéphane Grappelli. The recordings of legendary trumpeters like Miles Davis, Dizzy Gillespie, and Lee Morgan, are joined by those of all round performers such as Louis Armstrong, and celebrated female vocalists like Ella Fitzgerald, Bessie Smith, Billie Holliday and Jean Knight.

Waugh would broadcast through the night, from midnight until 3am a show, which as the journalist Andrew Gray describes, would “tell the solitary driver, the insomniac, the invalid, the shift worker: You are not alone.” Using the handle ‘Nighthawk’, Jimmy Waugh shared with listeners his love and encyclopaedic knowledge of the international Jazz scene, with its diverse range of complex talents and larger than life personalities to entertain his loyal, nocturnal fan base.

Less well known is that the ‘Nighthawk’s’ early career was in civil engineering, a fact that no doubt would have come as a surprise to many of his late night listeners. In fact, Scotland’s foremost Jazz broadcaster was also responsible for a number of very large civil engineering projects in the UK and Middle East. Perhaps it was this spirit to construct and make new which first attracted Waugh to Jazz, or maybe it provided the perfect counter balance to his chosen profession.

Check out this playlist selected from albums held in the collection or visit the Archives and Special Collections reading room on level 5 of the library to discover if the spontaneous, improvisational aesthetic of Jazz might inspire you.

Search for titles in the James Waugh record collection in the SUPrimo library catalogue.

#jazz#vinyl#20th century#special collections#James Waugh#Nighthawk#album art#cover art#music#archives and special collections#university of strathclyde

8 notes

·

View notes