#davidwiley

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Up next on my 80's Fest Movie 🎬 Marathon...Friday The 13th, Part 3 (1982) on glorious vintage VHS 📼! #movies #Movie #horror #fridaythe13th #fridaythe13thpart3 #seanscunningham #danakimmell #richardbrooker #riprichardbrooker #paulkratka #larryzerner #rachelhoward #katherineparks #davidkatims #jeffreyrodgers #traciesavage #gloriacharles #ripgloriacharles #cherimaugans #nicksavage #stevesusskind #amysteel #JohnFurey #stevedash #ripstevedash #KevinOBrien #DavidWiley #vintage #VHS #80s #80sfest #durandurantulsas6thannual80sfest

#friday the 13th#friday the 13th part 3#sean s cunningham#richard brooker#rip richard brooker#Jason#Jason Voorhees#dana kimmell#paul kratka#david katims#cheri maugans#steve susskind#larry zerner#nick savage#tracie savage#rachel howard#catherine parks#jeffrey rodgers#Gloria Charles#rip gloria charles#amy steel#john furey#steve dash#rip steve dash#david wiley#vhs#80s#80s fest#duran duran tulsa's 6th annual 80s fest

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Join us for a virtual tour of Jacques-Louis David Meets Kehinde Wiley! Created by Lisa Small, Senior Curator, European Art, Eugenie Tsai, Senior Curator, Contemporary Art , and Joseph Shaikewitz, Curatorial Assistant, Arts of the Americas and Europe.

The exhibition places two iconic paintings in dialogue: Kehinde Wiley’s Napoleon Leading the Army over the Alps (2005) and its early nineteenth-century source image, Jacques-Louis David’s Bonaparte Crossing the Alps (1800–1) from the Château de Malmaison.

Displayed together for the first time, these two heroic images provide an opportunity to explore how constructions of power, representation, race, masculinity, and agency are enacted within the realm of portraiture.

The introductory gallery features Wiley's Rumors of War—a smaller version of the monument he unveiled in Times Square last fall—which shows his continued interest in equestrian imagery (or sitters on horseback).

Here, he adapted a contested statue depicting the Confederate General J. E. B. Stuart installed on Monument Avenue in Richmond, Virginia, and transformed the sitter into a valiant young Black man whose likeness is a composite of several young men.

In Wiley’s words, this work functions “to expose the beautiful and terrible potentiality of art to sculpt the language of domination.”

This case displays several 18th and 19th-century objects from the Brooklyn Museum collection that show how Napoleon and his achievements were celebrated in visual culture during and after his rule.

Napoleon entered the military at 16, became a full general in the French Revolutionary Army at age 24, and in 1804, he crowned himself Emperor of the French.

This medal struck in 1806 aligns his profile with the early 9th-century Roman emperor Charlemagne. A savvy political propagandist, Napoleon liked to connect his reputation and image with ancient imperial glory.

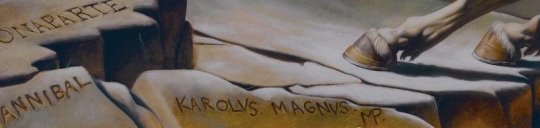

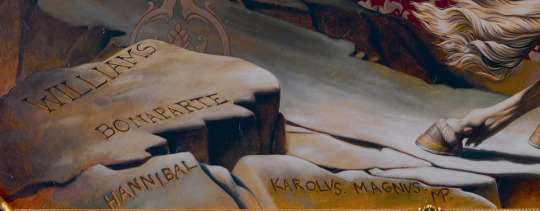

David made the same connection in his painting, inscribing “KAROLVS MAGNVS” (Latin for Charlemagne) in the rocky foreground.

The equestrian format of Antoine-Louis Barye’s bronze sculpture of Napoleon echoes the same ancient visual tradition for portraying rulers David used in his painted portrait, and that Wiley continues in his painting and sculpture.

Barye made this sculpture in the 1860s, long after the end of Napoleon’s reign in 1815, during the rule of his nephew, Napoleon III, who sought to revive and connect to his uncle’s imperial image and legacy.

Visual propaganda goes both ways! This small section features several early 19th-century satirical prints that subverted Napoleon’s heroic persona by belittling his character and portraying him as a villainous despot.

The British, who were constantly at war with France during this period, were especially good at creating scathing, satirical images of Napoleon, whom they gave the unflattering nickname “Boney.”

In this 1806 etching, James Gillray highlights Napoleon’s penchant for installing loyal rulers across his growing empire by showing him pulling his “imperial gingerbread” from the “new French oven” while behind him his Foreign Minister Talleyrand kneads the dough to make more. If you look to the right, you’ll see a favorite detail: a group of “Little Dough Viceroys” waiting to be baked.

The main gallery focuses on the David and Wiley paintings. Made two centuries apart, they highlight the connection of image-making to power, serving as a reminder, in this age of social media and celebrity, of the relationship between visual culture, dominance, and history.

The pairing offers a timely examination of the European canon, while also showing how historical artworks can speak to issues of race and power in the present moment.

David reimagines Napoleon crossing the Alps in 1800, on his way to recapture Italian territory lost in war with Austria. With him was an army of 4,000 soldiers who pulled heavy artillery up 6,500 feet.

Reality check: Napoleon didn’t actually lead the charge across the Alps wearing a fine uniform and riding a white horse, but in a grey overcoat and riding a donkey.

This idealized image was meant to serve as an emblem of power, victory, and authority. It is pure propaganda, and has become a famous symbol of military glorification and the cult of personality.

King Charles IV of Spain commissioned David’s painting, but Napoleon himself liked it so much that he asked the artist to create a replica of it for him. We have on view the first version, which went to Spain.

Fun fact: In 1808 Napoleon made his brother Joseph the King of Spain, and he took ownership of David’s painting. When Napoleon lost power in 1815, Joseph went into exile in the US and took the painting with him to New Jersey, where it remained for at least 15 years!

Wiley engages with the grand tradition of European portraiture and its ability to construct images that convey the power of the sitter. His work shows his practice of drawing from older paintings, preserving the pose and composition. Here he swaps the heroic figure of Napoleon for a Black man, an everyday civilian, to highlight the fact that he and other brown and Black people have been written out of this history.

Part of his 2005 series “Rumors of War,” the painting is emblematic of Wiley’s complicated engagement with European history and portrait painting, showing, as he has said, that he’s “drawn toward that flame and wanting to blow it out at once.”

Wiley replaces the figure of Napoleon with a contemporary Black citizen. Wiley chose him using his technique of street casting, in which the artist invites passersby into his studio to pose for paintings.

The sitter’s last name “Williams” joins the names of other military leaders in David’s original composition.

Wearing fatigues and Timberland boots, the sitter literally and figuratively redresses history. Although his camo attire updates the Napoleonic uniform, his style has more to do with what the artist has called “Brooklyn bravado” more so than an overt reference to the military.

Exhibition designer Lance Singletary created an opulent, theatrical space for the two paintings, including a central curtain swag that evokes the Napoleonic era. The golden crest, created by our talented graphic designer Paige Hanserd, combines David and Wiley’s initials enclosed by laurel branches.

The design is a nod to the laurel-wreath crown that Napoleon wore at his coronation and the popularity of the laurel motif in French Empire design.

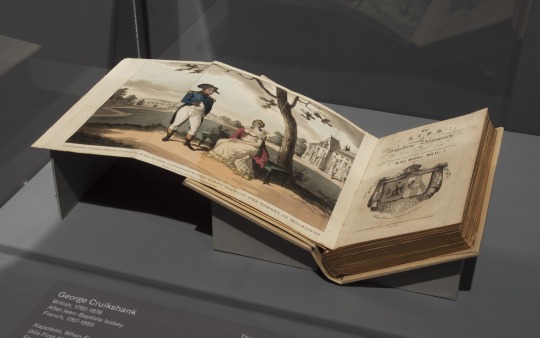

This book in the last gallery shows Napoleon and his first wife, Joséphine Bonaparte, on the grounds of Malmaison, the couple’s residence from 1800–02. During this period, Napoleon reinstated slavery in France’s Caribbean colonies—a practice that had been abolished by the French Revolution in 1794.

Some historians believe that Napoleon’s decision was influenced by Joséphine, who was born and raised in Martinique to a family that made its wealth through a sugar plantation and the labor of enslaved peoples.

The final gallery also includes this sculpture by Wiley in the Brooklyn Museum’s collection. The work draws on an eighteenth-century bust by the French neoclassical sculptor Jean-Antoine Houdon.

youtube

The exhibition closes with a video of Wiley’s visit to Malmaison last year to see David’s painting in person for the first time. He comments on the ways in which history masks the construction of power, the labor of brown and Black bodies, and the complex racial overtones of imperialism.

Thank you for joining us on our virtual tour of Jacques-Louis David Meets Kehinde Wiley. Tune in next Sunday for another virtual tour of our galleries.

Installation view, Jacques-Louis David Meets Kehinde Wiley, Brooklyn Museum (Photo: Jonathan Dorado)

#virtual tours#davidwiley#kehinde wiley#virtual tour#exhibitions#art#history#brooklyn#brooklyn museum#art museums#jacques-louis david#museumfromhome#art history#virtualtour

190 notes

·

View notes