#but a bolshevik coup

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Me when Westerners give bolsheviks credit for overthrowing the monarchy

#random history#russia#communism#are the esers cadets et al a joke to you#my professor of modern russian history#even doesn't consider the October events a revolution#but a bolshevik coup

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

The head of the Russian occupation administration of Zaporizhia, Yevgeny Balitsky, said that Russia’s goal is to occupy not only Ukraine, but also the Baltic countries, Poland and Finland. Because these states are "the historical lands of Russia".

"The Russian Empire, when it was shaken after the Bolshevik coup and took a different path of development lost a lot of its subjects (citizens). I'm not talking about lost lands now, that goes without saying, I understand that these are both Warsaw and Helsinki. And Revel (Tallinn) and Liepaja... And of course the entire Baltic region is all our lands and our people live there. The fact that they have now been made into a "dump herd" and "trembling creatures" - we must correct this. "And we will correct this situation with the power of Russian weapons. I don't believe in any diplomacy in this case. Well, perhaps diplomacy should always be present, but I believe that we can return all this (to Russia) only by the force of Russian weapons. Bring back you people, your subjects who previously belonged to the Russian Empire and today belong to the Russian Federation. This must be done so that the whole world does not turn into the Sodom and Gomorrah that is now happening in Europe."

650 notes

·

View notes

Text

In April 15th, 1920, the National Committee of the Federation of Socialist Youths met in Madrid to, taking the initiative over the PSOE, take the decision of joining the Third International, founded by the Bolshevik party. After a convoluted process that lasted until the 14th of November of 1921, the Communist Party of Spain (Spanish Section of the Communist International) was born, pejoratively called "The party of the 100 children" by its opponents.

The Komintern's policy in its early days was one of the "only front", stating that capital could only be beat via the united effort of all communists in all spheres of life. Its motto became "Towards the Masses!". In Spain, this period was marked by Primo de Rivera's dictatorship between 1923 and 1930, during which almost every political group was banned. The social-democratic PSOE and UGT avoided this by remaining "neutral" towards the dictatorship. Some members of the PSOE even collaborated, like Largo Caballero, who became Rivera's Minister of State. The Communist Party maintained its sole struggle during this time, gaining popularity among the Spanish proletariat.

When the dictatorship ended and the Second Republic was proclaimed in April of 1932, in the midst of the effects of the 1929 capitalist crisis, the 1931 strike in Sevilla and 1932 general strike, the PCE had found itself unable to work outside the dynamics imposed by the dictatorship's repression, and only began to regain its force after the selection of José Diaz as general secretary in September of 1932. The party corrected some of the left-communist and sectarian mistakes that characterized the period of the dictatorship.

The PCE took on an even bigger role in the organization of our class after its crucial role in the October insurrection of 1934 in Asturias, during which the proletariat took power in the mining basin and most of Oviedo, via the Peasant and Worker Alliances, expressions of the aforementioned only front strategy decided by the Third International. The government of the Second Republic, carrying out the needs of a section of the Spanish bourgeoisie, brutally repressed the Asturian revolutionaries, with general Francisco Franco at the helm of the military's intervention. Among the victims was Aida Lafuente, a militant of the Communist Youth and an example of bravery.

This glimmer of worker power was contextualized in the Black Biennium (1933-1935), a period of the Republic when reactionaries accessed the government and expressed the most violent tendencies of the Spanish bourgeoisie against the more than 30,000 political prisoners they took, and against the rapidly developing workers' movement.

It was during this time in Spain and the whole world, when the Third International identified the generalized rise of fascism and reactionarism, and adopted in its 7th Congress, during the summer of 1935, the policy of the Popular Front, failing to link the anti-fascist struggle with the struggle for workers' power, instead advocating for alliances with "socialist" parties and other bourgeois-democratic parties, placing the fight for socialism-communism in the background.

Half a year after this decision, the Popular Front alliance won the elections in the 16th of February, 1936. Shortly after, and only a year after the 7th Congress, sections of the Spanish and international bourgeoisie countered this victory with a failed coup d'etat by fascist generals in the 18th of July, 1936. They had the backing of the nazi-fascist powers in Europe and the complicity of the "democratic" capitalist powers, who were anxious about the strengthening proletariat in Spain. Curiously, the plane that carried Franco from his exile in the African colonies to Tetuán in north Africa, the Dragon Rapide, originally took off from London.

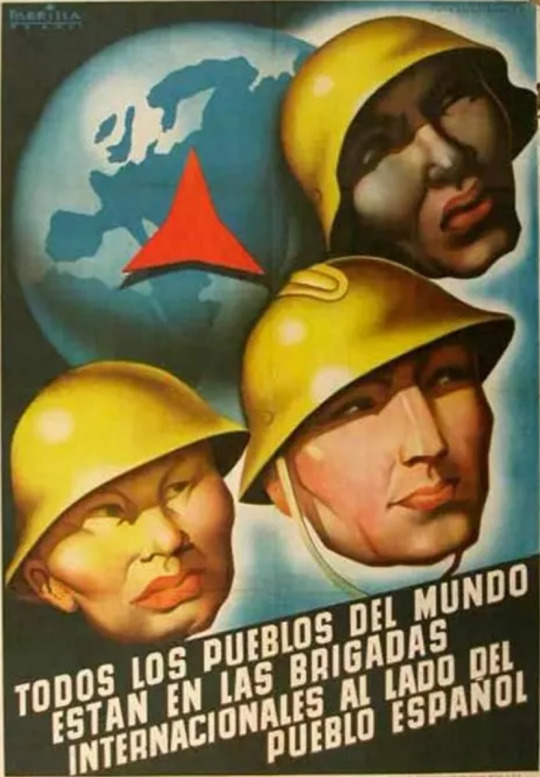

The biggest supporter of the Spanish Republic was the USSR, that, through the enormous effort of the Third International and the Communist Parties in 52 countries, against the banning of volunteering by many of those 52 countries, organized the enlistment, falsification of documents, logistics, arrival and other matters for the arrival of around 35,000 workers, peasants and intellectuals from all over the world. Under the single banner of the International Brigades, and for the first time materializing the historic slogan Workers of the World, Unite!, the Volunteers of Liberty, as they also came to be known, gave their mind and their body to the cause of the Spanish people, armed with the teachings of marxism-leninism. They knew that it was no longer a fight for only the Spanish. As J. V. Stalin put it in October of 1936:

The workers of the Soviet Union are merely carrying out their duty in giving help within their power to the revolutionary masses of Spain. They are aware that the liberation of Spain from the yoke of fascist reactionaries is not a private affair of the Spanish people but the common cause of the whole of advanced and progressive mankind.

In July of 1936 there already were Brigadiers present in Spain, for the occasion of the Popular Olympics (in boycott of the Berlin Olympics) organized by the Red Sport International and the Socialist Worker Sport International in Barcelona, they were among the first to take up arms against the coup d'etat. The Executive Committee's Secretariat of the Third International formalized in the 18th and 19th of September the creation of the International Brigades, which began to arrive in Spain the 14th of October of 1936. Despite the propaganda levied by fascists and bourgeois historiography, the importance of the International Brigades is undeniable today.

After the integration of the Brigades into the Popular Militias in the 22nd of October, the Brigadiers began their training in Albacete and saw action for the first time the 8th of November in Madrid, with the 11th and 12th Brigade. Militarily, the Brigades were present and indispensable in every major battle of the war, but they also played a moral role. After every capitalist power had abandoned the Spanish people to their fate with the policy of non-intervention, the compact and disciplined columns that marched through the streets of Madrid singing songs like The Internationale, Young Guard, or The Marseillaise, made up of workers who barely knew the language but were willing to make the ultimate sacrifice, decidedly improved the morale of every militia and civilian in Madrid and in Spain.

But even greater than the support of the Brigades were the more than 300,000 strong military detachments sent by Germany and Italy, with the implicit approval of capitalist democracies, including the Popular Front in France, whose efforts of non-intervention focused exclusively on the republic. And it was the strategy of the popular front that forced the PCE to sideline the revolutionary potential of the hundreds of thousands of militants, instead preserving the legitimacy of the bourgeois republic.

By 1938, the republic was on its last legs and, wishing to evidence the foreign involvement on the fascist side, declared to the League of Nations in the 21st of September that they would disband all volunteers enlisted after the 18th of July, 1936. The 16th of October, 2 years and 2 days after the arrival of the Brigades, the League of Nations' International Committee arrived in Spain to verify the disbandment and departure of the Brigadiers. No such inspection was ever made on the fascist side.

According to the International Committee's report published on the 18th of January, 1939, there were a total of 12,673 Brigadiers in Spain, less than half of the total number of volunteers at around 35,000. They began to depart Spain on the 2nd of November, 1938, through the French border. During the process of departures, some Brigadiers were murdered in Spain, others died protecting the fleeing republicans and hundreds of thousands of refugees at the crossing in France. This was when Mexico, and especially the Communist Party of Mexico which pressured the government, took on around 1,600 brigadiers, mainly Germans, Poles, Italians, Austrians, Czechoslovaks and Yugoslavians, who could not safely return to their homes due to the advance of fascism within their countries. The debt owed by the workers of the world, especially the Spanish, to the Communist Party of Mexico is immeasurable, along with every other Communist Party that helped and the Third International.

The dissolution of the International Brigades did not achieve the result desired by the Republic. Instead, their retreat towards the end of the Battle of the Ebro only accelerated the morale defeat of the republican militias. Most of the brigadiers who survived the war but could not be repatriated in time did not have a pleasant fate. Most of those ended up in the French concentration camps of Gurs, Argèles-sur-Mer, Saint-Cyprien and Barcarès, Septfonds, Riversaltes, or Vernet d'Ariège.

Their fight was not in vein. The experience gained by the few who survived at a high cost proved essential in the development of their own parties, and soon enough, anti-fascist resistance. Everywhere that people took up arms against the fascist occupation, whether inside or outside the concentration camps, ex-Brigadiers were present, continuing the fight they started in the 18th of July, 1936, well after the war that had began that day was history.

Back in Spain, while the moribund republic thrashed for the last few times, the bourgeois republican government, headed by the social-democrat Juan Negrín, began to isolate the PCE with the support of the trotskyists and anarchists. It came to a close after the coup d'etat by the republican general Casado, during and after which the communist militancy was oppressed, and the fascist fifth column that had remained in Madrid opened its gates to the fascist military. This is how the fascist dictatorship began in Spain, with a betrayal by the Popular Front's social-democrats and by the democratic-bourgeois powers of the world. They couldn't help but mirror the collaborationism happening on the world stage; the UK was actively looking for an alliance with Germany, and every other capitalist country was making business with the looted property. All for one purpose that united them; the destruction of workers' power in the form of the marxist-leninist parties that around the world were beginning to challenge the capitalists, with the Third International at the helm.

These are the lessons that Spain and the world learnt during and after its fierce resistance against fascism. No popular front with bourgeois-democrats is sustainable, and their class character will always prevail above the superficial differences with fascism. The only viable tool is the organization of the social majority within the Communist Party, with proletarian internationalism and an altruist disposition as principles. No matter how much social-democracy may fear fascist privatization, and no matter how much they disrespect bourgeois democracy, the class interests that guide them will always prevail when faced with a capable mass of organized workers.

The progressive Popular Front in France, the "appeasing" government in the UK, and the nominally anti-violence liberal democracies, did not ever attempt to do anything else than giving carte blanche to the fascists and hindering their rivals. The betrayal of Spain, Austria, Czechoslovakia and Poland were all made with the same reasoning: the alliance with fascism to destroy communism. There are no reasons that make the opposite possible today. When reactionarism picks up traction in lockstep with the deepening capitalist crises, all of these bourgeois-democrats some "leftists" like to place their hope in will not vary substantially from the script they followed 85 years ago.

Quedad, que así lo quieren los árboles, los llanos, las mínimas partículas de la luz que reanima un solo sentimiento que el mar sacude. ¡Hermanos! Madrid con vuestro nombre se agranda e ilumina

Rafael Alberti, A las Brigadas Internacionales

127 notes

·

View notes

Text

To understand the full context of the American-led ‘53 coup against Mosaddegh in Iran it is imo critical to recognize anti-communism as a proximate cause. Write-up below:

It is commonly understood that the early decades of the 20th century in Iran are characterized by British colonial extortion of material resources (mostly oil) within the boundaries of “Persia” (pre-1935) / “Iran” (post). The penultimate monarchical dynasty, the Qajars, were ousted in 1925—but the exile of the last Qajar Ahmad Shah was the direct result of the 1921 military coup led by then-Reza Khan (later the first “Pahlavi”, Reza Shah) which was directed by Britain. And at this time, British anxieties heavily featured concerns about Bolshevik encroachment from the Caucuses (not just through the newly-formed Azerbaijan SSR, but also through domestic sympathizers that fueled such projects as large as the transient Persian SSR, put down by Reza Khan after Soviet withdrawal).

This is stage-setting. Of course, by the 50s, in tandem with Cold War thread-pulling, the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company constituted a thirsty tentacle of British imperialism sucking Abadan dry and contributing pittances to the local economy. It was in the midst of decades of growing resentment against this presence that Mosaddegh became Prime Minister in 1951 as the leader of the broad National Front coalition, and we are familiar with how intensely he campaigned for nationalizing the country’s oil and how pissy this made the British (here’s one and another post on the subject if not).

Here’s the detour: you may know that it was the CIA, an American institution, that orchestrated the ‘53 coup to oust Mosaddegh. But we were just now discussing threats against British colonial power in Iran. How did things get from B to A, as it were? We can’t take this for granted.

The British in fact spent the intervening two years trying to get Mosaddegh out by mobilizing the Shah and various right-wing (often clerical and mercantile) interests in Iran (this point, and much of what follows, draws from bits of Darioush Bayandor’s Iran and the CIA and Mostafa Elm’s Oil, Power, and Principle). They spent the same two years desperately trying to get the Americans on board with their efforts. But—here it is—the Truman regime and American foreign policy was in general intensely hostile to this strain of British interventionism in Iran, going so far as to issue warnings against it.

Why? Well, as you would expect, the Americans were concerned about Soviet influence in the region. Then-U.S ambassador in Tehran Henry Grady claimed that “Mosaddegh’s National Front party is the closest thing to a moderate and stable element in the national parliament” (Wall Street Journal, June 9 1951). This summarizes the American position at the time: Mosaddegh’s nationalist movement constituted the bastion against communism, and the US was very interested in the survival of this bastion lest Iran align with the USSR.

What happened between 1951 and 1953 is that British pressure, operating through the Shah and more conservative elements of the Iranian government, jeopardized moderate support for Mosaddegh. With the right and center-right against him an entire wing of National Front coalition was falling off, and Mosaddegh found himself leaning more and more on the strengthening Tudeh Party, which had grown in numbers to militaristic significance during Mosaddegh’s tenure (including a network of at least 600 officers in the state military). Tudeh, of course, was the pro-Soviet communist party in Iran. And now the threads come together.

It was in this context of Mosaddegh, backed into a corner with almost only the communists behind him, that the CIA released a memo on November 20th, 1952 singing a very different tune:

It is of critical importance to the United States that Iran remain an independent and sovereign nation, not dominated by the USSR...

Present trends in Iran are unfavorable to the maintenance of control by a non-communist regime for an extended period of time. In wresting the political initiative from the Shah, the landlords, and other traditional holders of power, the National Front politicians now in power have at least temporarily eliminated every alternative to their own rule except the Communist Tudeh Party...

It is clear that the United Kingdom no longer possesses the capability unilaterally to assure stability in the area. If present trends continue unchecked, Iran could be effectively lost to the free world in advance of an actual Communist takeover of the Iranian Government. Failure to arrest present trends in Iran involves a serious risk to the national security of the United States.

And (!!!)

In light of the present situation the United States should adopt and pursue the following policies:...

Be prepared to take the necessary measures to help Iran to start up her oil industry and to secure markets for her oil so that Iran may benefit from substantial oil reserves...

Recognize the strength of Iranian nationalist feeling; try to direct it into constructive channels and be ready to exploit any opportunity to do so

It took two tries for the CIA to bring about a coup that removed Mosaddegh from power, but the objective of this coup was not the preservation of British control over Iranian resources; it was the maintenance of the Western sphere of influence against communist revolution (this was further prioritized by the arrival of the Eisenhower administration). In fact, after the coup the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company (now renamed British Petroleum) had to make room for six other companies from the US, France, and the Netherlands as part of a consortium, and this consortium would split profits with Iran 50/50. This is, to be clear, still colonialist extraction! But it constitutes a huge blow to British economic interests, because they were never the CIA’s goal. This is part of why the post-coup government is characterized far more as a US puppet than a British one.

It does remain that this was a sequence of events very much set in motion because of actions taken by the British government; by the time they managed to get shit to hit the fan, though, it was very much no longer in their control where the shit was flying.

614 notes

·

View notes

Text

here's a jewish joke for you:

I thought I would just make a real quick list of all the pogroms over the past 200 years.

that's it , that's the joke.

it is to laugh.

first of all, I didn't fully understand what a pogrom was until I started making a list.

a pogrom is basically mob violence against the Jews, or in some definitions, mob violence by one community against another. but like. it's when a violent, angry mob smashes, burns, and loots its way through a Jewish neighborhood. this usually involves Jewish casualties.

sometimes the casualties are the point. in the one I just read about, the head of the Cossack brigade crushed a Bolshevik coup in his city, then turned around and told his troops that the Jews were behind it (the Jews had in fact said NO, DON'T, THIS IS A BAD IDEA), and that they were the greatest threat to both Russia and Ukraine, and to "exterminate" them.

and then the troops spent three hours busting into Jewish homes and killing a total of 1,650 people.

wait, no, that's not even my point.

my point is:

i already had more than 190 listed, and tons more places to check or to finish looking at. like, honestly, most of the world and era to finish looking at.

then i got to the Russian Civil War and oopsie

1,326 pogroms.

NO WAIT FUCK

the article it links to says "over 1,500."

like, it's not like i'm gonna put the time in to identify every single one of those. that is just a literally jaw-dropping number of pogroms.

IN tHREE YEARS.

Historians have begun calling it the precursor to the Holocaust.

About 250,000 Jews were killed. 50,000 to 300,000 children were orphaned. And 500,000 were driven out from or fled their homes.

This was AFTER the Soviet Union displaced 600,000 Polish Jews deep into Russia during WWI. It deported 250,000 Polish Jews, and 350,000 more followed as refugees.

52 notes

·

View notes

Note

You mentioned Allende being a part of your journey towards M-L; if you don't mind expanding on this, I don't know a lot about it and I was curious which element of his story/Chile's history you meant in particular? His suicide? The coup itself? CIA intervention? The situation as a whole? Why did it impact your world view so much compared to other similar histories? Thanks!

the thing about allende is that he 'did everything right', so to speak. he was legally elected under a liberal democratic system, he made diplomatic concessions to try and appease the USA, he didn't suppress his opposition or form militias--and the CIA couped him anyway and installed a government that brutalized chile and chilean socialism for eleven years. learning about the coup and what came before and after totally shattered my youthful belief that you just had to be fairly voted into power and you'd have a mandate after that. the truth is, it's a game you just can't win. even if you win, you lose.

i don't think there's anything especially unique about allende's case--he's just the first one i learned about and hit especially close to home because i'm latin american (my home country has faced two coup attempts in my lifetime lol). if i'd learned about arbenz or sukarno first it probably would have had the same effect.

this realization also fundamentally opened my mind to reading lenin & other bolshevik theorists, because with the death of my belief in the possibility of winning by the rules of liberal politics came the death in my belief in the myth of the bolsheviks as anti-democratic oppressive tyrants and an interest in seeing what they did and believed that worked.

in summary, as engels wrote:

724 notes

·

View notes

Text

Following are remarks Friday of the foreign minister of Poland, Radek Sikorski, at the United Nations Security Council.

* * *

I’m amazed at the tone and the content of the presentation by the Russian ambassador.

And I thought I could be useful by correcting the record. Ambassador Nebenzya has called Kyiv a client of the West. Actually, Kyiv is fighting to be independent of anybody.

He calls them a criminal Kyiv regime. In fact, Ukraine has a democratically elected government.

He calls them Nazis. Well, the president is Jewish, the defense minister is Muslim, and they have no political prisoners.

He said that Ukraine was wallowing in corruption. Well, Alexei Navalny documented how honest and full of probity his own country is.

He blamed the war on U.S. neo-colonialism. In fact, Russia was trying to exterminate Ukraine in the 19th century, again under Bolsheviks, and now it is the third attempt.

He said we are prisoners of Russophobia. “Phobia” means irrational fear. Yet, we are being threatened almost every day by the former president of Russia and Putin’s propagandists with nuclear annihilation. I put it to you that it is not irrational — when Russia threatens us, we trust them.

He said that we are denying Russia’s security interests. Not true. We only started rearming ourselves when Russia started invading her neighbors.

He even said that Poland attacked Russia during World War II. What is he talking about? It was the Soviet Union that attacked Poland together with Nazi Germany on the 17th of September 1939. They even held a joint victory parade on the 27th of September.

He says that Russia has always only beaten back aggression. Well, what were then Russian troops doing at the gates of Warsaw in August 1920? They were on a topographic excursion? The truth is that for every time Russia was invaded, she has invaded ten times.

He says that it is a perfidious proxy war by the West. My advice is – don’t fall into the Western trap. Withdraw your troops to international borders and avoid this Western plot.

He also says that there was an illegal coup in Kyiv in 2014. I was there. There was no coup. President Yanukovych murdered a hundred of his compatriots and was removed from office by a democratically elected Ukrainian parliament, including by his own party, the Party of Regions.

And finally he is saying that we the West are somehow trying to persuade that Russia can never be beaten. Well, Russia did not win the Crimean War, it didn’t win the Russo-Japanese war, it didn’t win World War I, it didn’t win the battle of Warsaw, it didn’t win in Afghanistan, and it didn’t win the Cold War.

But there’s good news. After each failure there were reforms.

Such demagoguery is unworthy of a member on a permanent basis of the Security Council. But what the ambassador has achieved is to remind us why we resisted Soviet domination and what Ukraine is resisting now.

They failed to subjugate us then. They’ll fail to subjugate Ukraine and us now.

79 notes

·

View notes

Photo

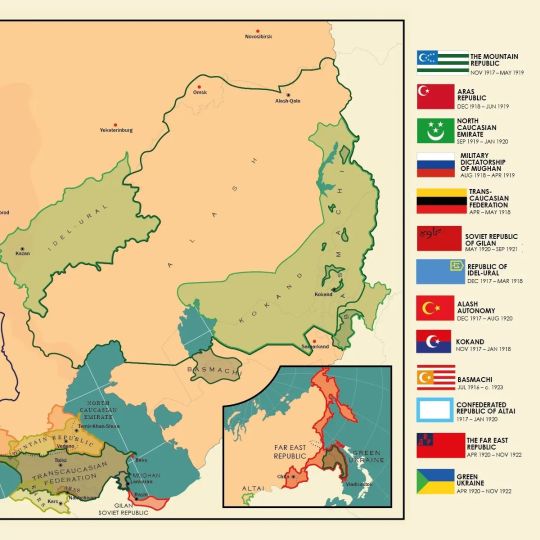

Temporary states during the Russian Civil War (1917–1922)

Anders Kvernberg (Oslo, 2018)

via cartesdhistoire

The Russian civil war (Oct. 1917-summer 1922) pitted Reds (communists), Whites (tsarists led by Wrangel, Kolchak, Denikin, Yudenitch) & Greens (armies of peasants facing Whites & Reds) against each other. In this chaos, many states have a brief independent life.

The largest is the Far Eastern Republic, a Bolshevik puppet state (from which Green Ukraine seceded). The smallest are the Republic of Perloja, limited to a Lithuanian village, presided over by a veteran of the Tsarist army, & the Soviet Republic of Naissaar, proclaimed in a fort on an Estonian island in December. 1917 by 82 Bolshevik sailors (hunted by the Germans on February 24, 1918).

The German occupiers signed a first treaty in Brest-Litovsk on February 9. 1918 with Ukraine then a second on March 3 with the Bolsheviks. Germany seizes Poland, Lithuania & Courland while Finland, Estonia, Latvia & Ukraine become independent under German control.

The Ukrainian People's Republic (non-Bolshevik), autonomous since the spring of 1917, was overthrown by the coup d'état of the conservative general Skoropadsky. With German support, he established the Hetmanate (April–Dec. 1918) and was then ousted from power during an uprising led by Simon Petliura & his (non-Bolshevik) Ukrainian People's Army. The Ukrainian republic was restored until 1921, not without first having to fight the libertarian Ukraine (or Makhnovshchina), a revolutionary peasant movement led by Nestor Makhno, who capitulated to the Bolsheviks in August 1921. Other states on Ukrainian territory are the Bolshevik Republic of Odessa, the Lemko Republic, the Komańcza Republic (or Eastern Lemko Republic) & the Hutsul Republic. At the same time, in the east of Ukraine, the anti-Bolshevik Don Cossack Republic was formed.

No state survived the creation of the USSR on December 30. 1922.

93 notes

·

View notes

Note

When do you think Russia had the best chance of breaking the authoritarian cycle

Probably with the Kerensky government. Had he handled the Kornilov Affair better, he could have kept him on his side and kept the Bolsheviks in jail. Having the Soviet Union collapse with a multi-party democracy in its place would have required no August Coup and no Russian revanchism, which is a lot harder, in my view.

Thanks for the question, Asd.

SomethingLikeALawyer, Hand of the King

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

They [the Makhnovists] raised the slogan of Soviets without Parties, or more concretely Soviets without Bolsheviks. But it was the Bolshevik Party that strengthened the Soviets to first repel the Kornilov coup, and then overthrow the provisional (bourgeois) government, gathering all power in the hands of the Soviets. From February to October, no other party could defend the establishment of Soviet power by overthrowing the bourgeois government, even at the level of slogans. Lenin and the Bolsheviks insisted on “all power to the Soviets!”, putting forth this slogan where the Mensheviks and Social-Revolutionaries (Srs) dared not, even while other parties were in their majority in the Soviets. It was the Bolshevik Communist Party that brought the Soviets to power. If it hadn’t been for the October Revolution, the option for Russia would have been a tyrannical bourgeois power in which the Soviets were completely liquidated-and probably a white General of the Kornilov type would have been at the head of that regime.

During this period, the imperialist West also adopted and used the slogan “Soviets without Bolsheviks”. The counter-revolutionary Ataman Grigoryev also said that “the Soviets are fighting for their real power against the commissars” (!) (Arshinov, 1998). Because Soviets without Bolsheviks would be like a lion without teeth, would be destroyed in a few months, and the White Army generals would enter Moscow on horseback. Thus, in the context of the civil war, the slogan “Soviets without Bolsheviks” was synonymous with abandoning Soviet power.

These were the outlines of the order declared by Makhno’s Land Army. But behind this “libertarian” rhetoric, Makhno also did not shy away from building similar institutions to those Soviet ones he had banned under his own Black Flag. The Red Army was forbidden, but he had his Black Army. The Bolshevik Party was forbidden, but in areas ruled by Makhno, power was invested in his anarchist organisation. Although he might not have declared a party and did not appear as the leader of such before the masses, the organised political power of the Makhnovist anarchist movement was the only political movement in all “free” Soviets. The Cheka was forbidden, but Makhno had set up his own secret service under the label of “counter-intelligence”. Makhno’s Intelligence Department also did everything that the Cheka did (prosecution, imprisonment, trial, executions).

The Makhno Movement and Bolshevism, abstrakt, 2020

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Outside the army barracks on General Radko Dimitriev street. He was Head of the General Staff of the Bulgarian Army between 1904 and 1907 . Following an unsuccessful coup he was exiled to Rumania . He served as a Commander of a Corps in the Russian army during WW1. He was executed by the Bolsheviks in 1918.

#Plovdiv

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

Carceral communism has so far been the main narrative of communism due to the prevalence of “communist” States from the former Soviet Union, the People’s Republic of China, other socialist States, and their aligned Western parties.

After the Bolshevik coup during the Russian Revolution, the party of Lenin constituted a secret police—the Cheka—and even set up their headquarters at the Lubyanka, built on the same site as the secret police of Czarina Catherine. While the revolutionary upsurge emptied the Czar’s prisons and forced labor camps, the party of Lenin reconstituted these as gulags which Stalin would later inherit to incredibly bloody effect. Carceral communists such as Lenin, Trotsky, and Stalin may have opposed the Czar’s police and prisons, but only for the sake for their own institutions of oppression.

What Lenin and the Bolsheviks failed to realize is that communism is intrinsically a movement of proletarians struggling to abolish their class. By reconstituting “communist” police and prisons the Bolsheviks merely reproduced institutions of proletarianization and all that entailed.

Bolshevik “communism” merely universalized the proletarian condition instead of its abolition and married this proletarianization with the spectacular image of communism. ACAB means “communist” cops too. Abolition means abolish “communist” police and prisons.

#communism#abolition#police#prison#state capitalism#statism#authoritarianism#lenin#stalin#ussr#bolshevism

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

Events 8.19 (before 1930)

295 BC – The first temple to Venus, the Roman goddess of love, beauty and fertility, is dedicated by Quintus Fabius Maximus Gurges during the Third Samnite War. 43 BC – Gaius Julius Caesar Octavianus, later known as Augustus, compels the Roman Senate to elect him Consul. 947 – Abu Yazid, a Kharijite rebel leader, is defeated and killed in the Hodna Mountains in modern-day Algeria by Fatimid forces. 1153 – Baldwin III of Jerusalem takes control of the Kingdom of Jerusalem from his mother Melisende, and also captures Ascalon. 1458 – Pope Pius II is elected the 211th Pope. 1504 – In Ireland, the Hiberno-Norman de Burghs (Burkes) and Cambro-Norman Fitzgeralds fight in the Battle of Knockdoe. 1561 – Mary, Queen of Scots, aged 18, returns to Scotland after spending 13 years in France. 1604 – Eighty Years War: a besieging Dutch and English army led by Maurice of Orange forces the Spanish garrison of Sluis to capitulate. 1612 – The "Samlesbury witches", three women from the Lancashire village of Samlesbury, England, are put on trial, accused of practicing witchcraft, one of the most famous witch trials in British history. 1666 – Second Anglo-Dutch War: Rear Admiral Robert Holmes leads a raid on the Dutch island of Terschelling, destroying 150 merchant ships, an act later known as "Holmes's Bonfire". 1692 – Salem witch trials: In Salem, Province of Massachusetts Bay, five people, one woman and four men, including a clergyman, are executed after being convicted of witchcraft. 1745 – Prince Charles Edward Stuart raises his standard in Glenfinnan: The start of the Second Jacobite Rebellion, known as "the 45". 1745 – Ottoman–Persian War: In the Battle of Kars, the Ottoman army is routed by Persian forces led by Nader Shah. 1759 – Battle of Lagos: Naval battle during the Seven Years' War between Great Britain and France. 1772 – Gustav III of Sweden stages a coup d'état, in which he assumes power and enacts a new constitution that divides power between the Riksdag and the King. 1782 – American Revolutionary War: Battle of Blue Licks: The last major engagement of the war, almost ten months after the surrender of the British commander Charles Cornwallis following the Siege of Yorktown. 1812 – War of 1812: American frigate USS Constitution defeats the British frigate HMS Guerriere off the coast of Nova Scotia, Canada earning the nickname "Old Ironsides". 1813 – Gervasio Antonio de Posadas joins Argentina's Second Triumvirate. 1839 – The French government announces that Louis Daguerre's photographic process is a gift "free to the world". 1848 – California Gold Rush: The New York Herald breaks the news to the East Coast of the United States of the gold rush in California (although the rush started in January). 1854 – The First Sioux War begins when United States Army soldiers kill Lakota chief Conquering Bear and in return are massacred. 1861 – First ascent of Weisshorn, fifth highest summit in the Alps. 1862 – Dakota War: During an uprising in Minnesota, Lakota warriors decide not to attack heavily defended Fort Ridgely and instead turn to the settlement of New Ulm, killing white settlers along the way. 1903 – The Transfiguration Uprising breaks out in East Thrace, resulting in the establishment of the Strandzha Commune. 1909 – The Indianapolis Motor Speedway opens for automobile racing. William Bourque and his mechanic are killed during the first day's events. 1920 – The Tambov Rebellion breaks out, in response to the Bolshevik policy of Prodrazvyorstka. 1927 – Patriarch Sergius of Moscow proclaims the declaration of loyalty of the Russian Orthodox Church to the Soviet Union.

1 note

·

View note

Note

what is the historical stages stuff? im not trying to be confrontational, im just curious.

So Karl Marx, working with the data he had in the middle of the 19th century, theorized about the evolution of political economy as passing through several phases- "primitive communism" prior to the developed state, then economic relations based on slavery, then feudalistic ones, and finally, capitalism, where each phase produces a characteristic struggle between economic classes defined by their relationship to the "means of production".

To use Marxian feudalism as an example, it comes to an end because the means of production it relied on were land, and so it produced a class system where aristocrats held control over the majority of land and extracted production from peasants who worked it as serfs or tenants, and urban burghers, the bourgeoisie, were shut out from any relationship to the means of primary production, through land being controlled by customs and inheritance laws and unable to be alienated freely, thereby not being a commodity that could be sold on the market, though they held a substantial proportion of cash wealth because they were outside primary production. As a consequence, the development of capital-intensive means of production in the countryside and in the cities leads to bourgeois enterprises that snap up displaced peasants, who become impoverished urban workers that contribute to a growing slice of production. And then as this system develops, it leads eventually to bourgeois revolutions, where the burghers organize to overthrow the aristocrats and claim the power they believe they deserve.

This is Marxian feudalism, which is to say the vision that was roughly available to Marx. More recent research has complicated this and shifted it significantly.

So Marx concludes that capitalism, his contemporaneous mode of production, where the economic base lies in labor arrangements where capital goods used for production are functionally rented out by their owners to the workers who use them for production, has a class tension between these urban workers and the burghers, and that when capitalism ends, as he assumed it would, because for him history would keep moving on, that would be through a class struggle in which the urban proletarians (drawing a term from Roman history) overthrow the bourgeoisie and claim the power they believe they deserve, followed by a further point at which class distinctions vanish, because production has developed to the degree there is no way to control production and lock it off from other people.

Marx's analysis was necessarily tentative- his "Asiatic mode of production" is an acknowledgement that, even with his limited dataset, his analysis couldn't really account for China and India and so on.

Later in Marx's life and after his death, his students and collaborators end up calcifying this into a theory of historical stages and a grand narrative of progress through these stages, and with it the formalized belief that socialism/proletarian revolution could only emerge in the developed industrial economies of (at the time) Western Europe and the United States of America.

Then in 1917 and 1918, there's a revolution in Russia followed by a coup. By the end of the next three bloody years, the Bolshevik Party has established itself firmly as the government of what is now called the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. Marxist orthodoxy, and frankly, mainstream economists as well, understood Russia as a pre-capitalist society, with serfdom having been abolished only recently and extremely limited capital industrial development.

This means that, within the existing theory of Marxism, the Bolsheviks are incapable of a socialist revolution, but only a bourgeois one by which capitalism could be instituted and developed. The Bolsheviks were also not particularly popular in the Russian socialist left and broader Marxist circles prior to their victory, and so they were vulnerable to this kind of critique. They had made this even worse by, during the civil war, solving many problems with other socialist parties, the anarchists, and armed peasant groups through the application of force for expediency. (And like most leftist political parties then and now, their leadership had a number of people from families and situations well-off enough to produce intellectuals.)

Thus, Leninism emerges in order to explain why the use of force wasn't just another Reign of Terror falling on the sans-culottes and how the USSR can be socialist, but to do so, it must reify the historical stages even further to make the actions of the Bolsheviks necessary to "skip" the bourgeois stage, or at least speedrun it.

But the older Marxist orthodoxy doesn't go away. This is why the communists in Guatemala who advised Jacobo Arbenz urged him to establish a capitalist land market by breaking up plantations, why the Japan Socialist Party and Japan Communist Party cooperate with American occupation force economists to push through similar land reform bills in the late 1940s, and it's why Frantz Fanon has a long section in The Wretched of the Earth laying out that the problem for postcolonial societies is that their bourgeoisie have been warped into established relationships with the colonial metropole, and so an interventionist state must build proper capitalism independently.

Now, I am personally skeptical of the specifics, because more recent economic histories have shown a more complex economic environment everywhere we look, and we have examples like Andean gift economies which are somewhat outside of the structure of phases and stages. I think a meaningful political economy that accommodates this data is yet to be assembled, (no, I don't accept David Graeber as doing anything meaningful). And much of Marxist orthodoxy is simplified, and hasn't incorporated Marx's more powerful theorization of the base and superstructure relationship.

Does that help?

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chapter 6. Revolution

How do we know revolutionaries won’t become new authorities?

It is not inevitable for revolutionaries to become the new dictators, especially if their primary goal is the abolition of all coercive authority. Revolutions throughout the 20th century created new totalitarian systems, but all of these were led or hijacked by political parties, none of which denounced authoritarianism; on the contrary, a great many of them promised to create a “dictatorship of the proletariat” or a nationalist government.

Political parties, after all, are inherently authoritarian institutions. Even in the rare case that they legitimately come from disempowered constituencies and build internally democratic structures, they still must negotiate with existing authorities to gain influence, and their ultimate objective is to gain control over a centralized power structure. For political parties to gain power through the parliamentary process, they must set aside whatever egalitarian principles and revolutionary goals they might have had and cooperate with pre-existing arrangements of power — the needs of capitalists, imperialist wars, and so on. This sad process was demonstrated by social democratic parties around the world from Labour in the UK to the Communist Party in Italy, and more recently by the Green Party in Germany or the Workers’ Party in Brazil. On the other hand, when political parties — such as the Bolsheviks, the Khmer Rouge, and the Cuban communists — seek to impose change by taking control in a coup d’etat or civil war, their authoritarianism is even more immediately visible.

However, expressly anti-authoritarian revolutionaries have a history of destroying power rather than taking it. None of their uprisings have been perfect, but they do provide hope for the future and lessons on how an anarchist revolution could be achieved. While authoritarianism is always a danger, it is not an inevitable outcome of struggle.

In 2001, following years of discrimination and brutality, the Amazigh (Berber) inhabitants of Kabylia, a region of Algeria, rose up against the predominantly Arab government. The trigger to the uprising came on the 18th of April when the gendarmerie killed a local youth and later subjected a number of students to arbitrary arrest, though the resulting movement clearly demonstrated itself to be much broader than a reaction against police brutality. Starting April 21, people fought with the gendarmerie, burned down police stations, government buildings, and offices of opposition political parties. Noting that the offices of government social services were not spared, domestic intellectuals and journalists as well as leftists in France paternalistically admonished that the misguided rioters were destroying their own neighborhoods — omitting out of hypocrisy or ignorance the fact that social services in poor regions serve the same function as the police, only that they perform the softer part of the job.

The riots generalized into insurrection, and the people of Kabylia soon achieved one of their main demands — the removal of the gendarmerie from the region. Many police stations that were not burnt down outright were besieged and had their supply lines cut off so that the gendarmerie had to go out in force on raiding missions just to supply themselves. In the first months, police killed over a hundred people, and wounded thousands, but the insurgents did not back down. Due to the fierceness of the resistance rather than the generosity of the government, Kabylia was still off limits to the gendarmerie as of 2006.

The movement was soon organizing the liberated region along traditional and anti-authoritarian lines. The communities resurrected the Amazigh tradition of the aarch (or aaruch in plural), a popular assembly for self-organization. Kabylia benefited from a deep-rooted anti-authoritarian culture. During the French colonization, the region was the home to frequent uprisings, and daily resistance to government administration.

In 1948, a village assembly, for example, formally prohibited communication with the government about community affairs: “Passing information to any authority, be it about the morality of another citizen, be it about tax figures, will be sanctioned with a fine of ten thousand francs. It is the most grave type of fine that exists. The mayor and the rural guard are not excluded” [...] And when the current movement began to organize committees of neighborhoods and villages, one delegate (from the aarch of Ait Djennad) declared, to demonstrate that at least the memory of this tradition had not been lost: “Before, when the tajmat took charge of the resolution of a conflict between people, they punished the thief or the fraudster, it wasn’t necessary to go to the tribunal. In fact it was shameful.”[94]

Starting from April 20, delegates from 43 cities in the subprefecture of Beni Duala, in Kabylia, were coordinating the call for a general strike, as people in many villages and neighborhoods organized assemblies and coordinations. On the 10th of May, delegates from the different assemblies and coordinations throughout Beni Duala met to formulate demands and organize the movement. The press, demonstrating the role they would play throughout the insurrection, published a false announcement saying the meeting was cancelled, but still a large number of delegates came together, predominantly from the wilaya, or district, of Tizi Uzu. They kicked out a mayor who tried to participate in the meetings. “Here we don’t need a mayor or any other representative of the state,” said one delegate.

Delegates from the aaruch kept meeting and created an interwilaya coordination. On the 11th of June they met in El Kseur:

We, representatives of the wilayas of Sétis, Bordj-Bu-Arreridj, Buira, Bumerdes, Bejaia, Tizi Uzu, Algiers, as well as the Collective Committee of Universities of Algiers, meeting today Monday the 11th of June 2001, in the Youth House “Mouloud Feraoun” in El Kseur (Bejaia), have adopted the following table of demands: For the State to urgently take responsibility for all the injured victims and the families of the martyrs of the repression during these events. For the trial by civil tribunal of the the authors, instigators and accomplices of these crimes and their expulsion from the security forces and from public office. For a martyr status for every dignified victim during these events and the protection of all witnesses to the drama. For the immediate withdrawal of the brigades of the gendarmerie and the reinforcements from the URS. For the annulment of judicial processes against all the protestors as well the liberation of those who have already been sentenced during these events. Immediate abandonment of the punitive expeditions, the intimidations, and the provocations against the population. Dissolution of the investigation commissions initiated by the power. Satisfaction of the Amazigh claims, in all their dimensions (of identity, civilization, language, and culture) without referendum and without conditions, and the declaration of Tamazight as a national and official language. For a state that guarantees all socio-economic rights and all democratic liberties. Against the policies of underdevelopment, pauperization, and miserablization of the Algerian people. Placing all the executive functions of the State including the security forces under the effective authority of democratically elected bodies. For an urgent socio-economic plan for all of Kabylia. Against the Tamheqranit [roughly, the arbitrariness of power] and all forms of injustice and exclusion. For a case by case reconsideration of the regional exams for all students who did not pass them. Installment of unemployment benefits for everyone who makes less than 50% of the minimum wage. We demand an official, urgent, and public reply to this table of demands. Ulac Smah Ulac [the struggle continues][95]

On June 14, hundreds of thousands went to march on Algiers to present these demands but they were preemptively waylaid and dispersed through heavy police action. Although the movement was always strongest in Kabylia, it never limited itself to national/cultural boundaries and enjoyed support throughout the country; nonetheless opposition political parties tried to water down the movement by reducing it to simple demands for measures against police brutality and the official recognition of the Berber language. But the defeat of the march in Algiers did effectively demonstrate the movement’s weakness outside of Kabylia. Said one resident of Algiers, regarding the difficulty of resistance in the capital in contrast to the Berber regions: “They’re lucky. In Kabylia they’re never alone. They have all their culture, their structures. We live in between snitches and Rambo posters.”

In July and August, the movement set itself the task of reflecting strategically on their structure: they adopted a system of coordination between the aaruch, dairas and communes within a wilaya, and the election of delegates within towns and neighborhoods; these delegates would form a municipal coordination that enjoyed full autonomy of action. A coordination for the whole wilaya would be composed of two delegates from each of the municipal coordinations. In a typical case in Bejaia, the coordination kicked out the trade unionists and leftists that had infiltrated it, and launched a general strike on their own initiative. At the culmination of this process of reflection, the movement identified as one of its major weaknesses the relative lack of participation by women within the coordinations (although women played a large role in the insurrection and other parts of the movement). The delegates resolved to encourage more participation by women.

Throughout this process some delegates kept secretly trying to dialogue with the government while the press shifted between demonizing the movement and suggesting that their more civic demands could be adopted by the government, while ignoring their more radical demands. On August 20, the movement demonstrated its power within Kabylia with a major protest march, followed by a round of interwilaya meetings. The country’s elite hoped that these meetings would demonstrate the “maturity” of the movement and result in dialogue but the coordinations continued to reject secret negotiations and reaffirmed the agreements of El Kseur. Commentators remarked that if the movement continued to reject dialogue while pushing for their demands and successfully defending their autonomy, they effectively made government impossible and the result could be the collapse of state power, at least within Kabylia.

On October 10, 2002, after having survived over a year of violence and pressure to play politics, the movement launched a boycott of the elections. Much to the frustration of the political parties, the elections were blocked in Kabylia, and in the rest of Algeria participation was remarkably low.

From the very beginning, the political parties were threatened by the self-organization of the uprising, and tried their hardest to bring the movement within the political system. It was not so easy, however. Early on the movement adopted a code of honor that all the coordination delegates had to swear to. The code stated:

The delegates of the movement promise to Respect the terms enunciated in the chapter of Directing Principles of the coordinations of aaruch, dairas, and communes. Honor the blood of the martyrs following the struggle until the completion of its objectives and not using their memory for lucrative or partisan ends. Respect the resolutely peaceful spirit of the movement. Not take any action leading to establishing direct or indirect connections with power. Not use the movement for partisan ends or drag it into electoral competitions or attempts to take power. Publicly resign from the movement before seeking any elected office. Not accept any political office (nomination by decree) in the institutions of power. Show civic-mindedness and respect to others. Give the movement a national dimension. Not circumvent the appropriate structure in matters of communication. Give effective solidarity to any person who has suffered any injury due to activity as a delegate of the movement. Note: Any delegate who violates this Code of Honor will be publicly denounced.[96]

And in fact, delegates who broke this pledge were ostracized and even attacked.

The pressure of recuperation continued. Anonymous committees and councils began issuing press releases denouncing the “spiral of violence” of the youth and the “poor political calculations” of “those who continue loudly parasitizing the public debate” and silencing the “good citizens.” Later this particular council clarified that these good citizens were “all the scientific and political personages of the municipality capable of giving sense and consistency to the movement.”[97]

In the following years, the weakening of the movement’s anti-authoritarian character has demonstrated a major obstacle to libertarian insurrections that win a bubble of autonomy: not an inevitable, creeping authoritarianism, but constant international pressure on the movement to institutionalize. In Kabylia, much of that pressure came from European NGOs and international agencies who claimed to work for peace. They demanded that the aarch coordinations adopt peaceful tactics, give up their boycott of politics, and field candidates for election. Since then, the movement has split. Many aarch delegates and elders who appointed themselves leaders have entered the political arena, where their main objective is to rewrite the Algerian constitution to institute democratic reforms and end the present dictatorship. Meanwhile, the Movement for Autonomy in Kabylia (MAK) has continued to insist that power should be decentralized and the region should win independence.

Kabylia did not receive significant support and solidarity from anti-authoritarian movements across the globe, which might have helped offset the pressure to institutionalize. Part of this is due to the isolation and eurocentrism of many of these movements. At the same time, the movement itself restricted its scope to State boundaries and lacked an explicitly revolutionary ideology. Taken on its own, the civic-mindedness and emphasis of autonomy found within Amazigh culture is clearly anti-authoritarian, but in a contest with the State it gives rise to a number of ambiguities. The movement demands, if fully realized, would have made government impractical and thus they were revolutionary; however they did not explicitly call for the destruction of “the power,” and thus left plenty of room for the state to reinsert itself in the movement. Even though the Code of Honor exhaustively prohibited collaboration with political parties, the movement’s civic ideology made such collaboration inevitable by demanding good government, which is of course impossible, a code word for self-deception and betrayal.

An ideology or analysis that was revolutionary as well as anti-authoritarian might have prevented recuperation and facilitated solidarity with movements in other countries. At the same time, movements in other countries might have been positioned to give solidarity had they developed a broader understanding of struggle. For example, due to a host of historical and cultural reasons it is not at all likely that the insurrection in Algeria would ever have identified itself as “anarchist,” yet it was one of the most inspiring examples of anarchy to appear in those years. Most self-identified anarchists were prevented from realizing this and initiating relationships of solidarity due to a cultural bias against struggles that do not adopt the aesthetics and cultural inheritance prevalent among Euro/American revolutionaries.

The historic experiments in collectivization and anarchist communism that took place in Spain in 1936 and 1937 could only happen because anarchists had been preparing themselves to defeat the military in an armed insurrection, and when the fascists launched their coup they were able to defeat them militarily throughout much of the country. To protect the new world they were building, they organized themselves to hold back the better equipped fascists with trench warfare, declaring “No pasarán!” They shall not pass!

Though they had plenty to keep them busy on the homefront, setting up schools, collectivizing land and factories, reorganizing social life, the anarchists raised and trained volunteer militias to fight on the front. Early in the war, the anarchist Durruti Column pushed back the fascists on the Aragon front, and in November it played an important role in defeating the fascist offensive on Madrid. There were many criticisms of the volunteer militias, mostly from bourgeois journalists and the Stalinists who wanted to crush the militias in favor of a professional military fully under their control. George Orwell, who fought in a Trotskyist militia, sets the record straight:

Everyone from general to private drew the same pay, ate the same food, wore the same clothes, and mingled on terms of complete equality. If you wanted to slap the general commanding the division on the back and ask him for a cigarette, you could do so, and no one thought it curious. In theory at any rate each militia was a democracy and not a hierarchy... They had attempted to produce within the militias a sort of temporary working model of the classless society. Of course there was not perfect equality, but there was a nearer approach to it than I had ever seen or than I would have thought conceivable in time of war... ...Later it became the fashion to decry the militias, and therefore to pretend that the faults which were due to lack of training and weapons were the result of the equalitarian system. Actually, a newly raised draft of militia was an undisciplined mob not because the officers called the privates ‘Comrade’ but because raw troops are always an undisciplined mob... The journalists who sneered at the militia-system seldom remembered that the militias had to hold the line while the Popular Army was training in the rear. And it is a tribute to the strength of ‘revolutionary’ discipline that the militias stayed in the field at all. For until about June 1937 there was nothing to keep them there, except class loyalty... A conscript army in the same circumstances — with its battle-police removed — would have melted away... At the beginning the apparent chaos, the general lack of training, the fact that you often had to argue for five minutes before you could get an order obeyed, appalled and infuriated me. I had British Army ideas, and certainly the Spanish militias were very unlike the British Army. But considering the circumstances they were better troops than one had any right to expect.[98]

Orwell revealed that the militias were being deliberately starved of the weaponry they needed for victory by a political apparatus determined to crush them. Notwithstanding, in October, 1936, the anarchist and socialist militias pushed the fascists back on the Aragon front, and for the next eight months they held the line, until they were forcefully replaced by the government army.

The conflict was long and bloody, full of grave dangers, unprecedented opportunities, and difficult choices. Throughout it the anarchists had to prove the feasibility of their ideal of a truly anti-authoritarian revolution. They experienced a number of successes and failures, which, taken together, show what is possible and what dangers revolutionaries must avoid to resist becoming new authorities.

Behind the lines, anarchists and socialists seized the opportunity to put their ideals in practice. In the Spanish countryside, peasants expropriated land and abolished capitalist relations. There was no uniform policy governing how the peasants established anarchist communism; they employed a range of methods for overthrowing their masters and creating a new society. In some places, the peasants killed clergy and landlords, though this was often in direct retaliation against those who had collaborated with the fascists or the earlier regime by giving names of radicals to be arrested and executed. In several uprisings in Spain between 1932 and 1934, revolutionaries had shown little predisposition to assassinate their political enemies. For example, when peasants in the Andalucian village of Casas Viejas had unfurled the red and black flag, their only violence was directed against land titles, which they burned. Neither political bosses nor landlords were attacked; they were simply informed that they no longer held power or property. The fact that these peaceful peasants were subsequently massacred by the military, at the behest of those bosses and landlords, may help explain their more aggressive conduct in 1936. And the Church in Spain was very much a pro-fascist institution. The priests had long been the purveyors of abusive forms of education and the defenders of patriotism, patriarchy, and the divine rights of the landlords. When Franco launched his coup, many priests acted as fascist paramilitaries.

There had been a long-running debate in anarchist circles about whether fighting capitalism as a system necessitated attacking specific individuals in power, apart from situations of self-defense. The fact that those in power, when shown mercy, turned right around and gave names to the firing squads to punish the rebels and discourage future uprisings underscored the argument that elites are not just innocently playing a role within an impersonal system, but that they specifically involve themselves in waging war against the oppressed. Thus, the killings carried out by the Spanish anarchists and peasants were not signs of an authoritarianism inherent in revolutionary struggle so much as an intentional strategy within a dangerous conflict. The contemporaneous behavior of the Stalinists, who established a secret police force to torture and execute their erstwhile comrades, demonstrates how low people can sink when they think they’re fighting for a just cause; but the contrasting example offered by anarchists and other socialists proves that such behavior is not inevitable.

A demonstration of the absence of authoritarianism among the anarchists can be seen in the fact that those same peasants who liberated themselves violently did not force individualistic peasants to collectivize their lands along with the rest of the community. In most of the villages surveyed in anarchist areas, collectives and individual holdings existed side by side. In the worst scenario, where an anti-collective peasant held territory dividing peasants who did want to join their lands, the majority sometimes asked the individualist peasant to trade his land for land elsewhere, so the other peasants could pool their efforts to form a collective. In one documented example, the collectivizing peasants offered the individual landholder land of better quality in order to ensure a consensual resolution.

In the cities and within the structures of the CNT, the anarchist labor union with over a million members, the situation was more complicated. After defense groups prepared by the CNT and FAI (the Iberian Anarchist Federation) defeated the fascist uprising in Catalunya and seized weapons from the armory, the CNT rank and file spontaneously organized factory councils, neighborhood assemblies, and other organizations capable of coordinating economic life; what’s more, they did so in a nonpartisan way, working with other workers of all political persuasions. Even though the anarchists were the strongest force in Catalunya, they demonstrated little desire to repress other groups — in stark contrast to the Communist Party, the Trotskyists, and the Catalan nationalists. The problem came from the CNT delegates. The union had failed to structure itself in a way that prevented its becoming institutionalized. Delegates to the Regional and National Committees could not be recalled if they failed to perform as desired, there was no custom to prevent the same people from maintaining constant positions on these higher committees, and negotiations or decisions made by higher committees did not always have to be ratified by the entire membership. Furthermore, principled anarchist militants consistently refused the top positions in the Confederation, while intellectuals focused on abstract theories and economic planning gravitated to these central committees. Thus, at the time of the revolution in July, 1936, the CNT had an established leadership, and this leadership was isolated from the actual movement.

Anarchists such as Stuart Christie and veterans of the libertarian youth group that went on to participate in the guerrilla struggle against the fascists during the following decades have argued that these dynamics separated the de facto leadership of the CNT from the rank and file, and brought them closer to the professional politicians. Thus, in Catalunya, when they were invited to participate in an antifascist Popular Front along with the authoritarian socialist and republican parties, they obliged. To them, this was a gesture of pluralism and solidarity, as well as a means of self-defense against the threat posed by fascism.

Their estrangement from the base prevented them from realizing that the power was no longer in the government buildings; it was already in the street and wherever workers were spontaneously taking over their factories. Ignorant of this, they actually impeded social revolution, discouraging the armed masses from pursuing the full realization of anarchist communism for fear of upsetting their new allies.[99] In any case, anarchists in this period faced extremely difficult decisions. The representatives were caught between advancing fascism and treacherous allies, while those in the streets had to choose between accepting the dubious decisions of a self-appointed leadership or splitting the movement by being overly critical.

But despite the sudden power gained by the CNT — they were the dominant organized political force in Catalunya and a major force in other provinces — both the leadership and the base acted in a cooperative rather than a power-hungry manner. For example, in the antifascist committees proposed by the Catalan government, they allowed themselves to be put on an equal footing with the comparatively weak socialist labor union and the Catalan nationalist party. One of the chief reasons the CNT leadership gave for collaborating with the authoritarian parties was that abolishing the government in Catalunya would be tantamount to imposing an anarchist dictatorship. But their assumption that getting rid of the government — or, more accurately, allowing a spontaneous popular movement to do so — meant replacing it with the CNT showed their own blinding self-importance. They failed to grasp that the working class was developing new organizational forms, such as factory councils, that might flourish best by transcending pre-existing institutions — whether the CNT or the government — rather than being absorbed into them. The CNT leadership “failed to realise how powerful the popular movement was and that their role as union spokesmen was now inimical to the course of the revolution.”[100]

Rather than painting a rosy picture of history, we should recognize that these examples show that navigating the tension between effectiveness and authoritarianism is not easy, but it is possible.

#organization#revolution#anarchism#daily posts#communism#anti capitalist#anti capitalism#late stage capitalism#anarchy#anarchists#libraries#leftism#social issues#economy#economics#climate change#anarchy works#environmentalism#environment#solarpunk#anti colonialism#acab

5 notes

·

View notes

Note

you have zero audience on here but you still write all this idiotic bullshit. for who? it's a performance you do for yourself. you're a fucking idiot and a tool and a hopeless loser. you're as interesting as a piece of frozen dog shit. you cant handle that truth so you come on here and post your bootlicking dogmatic propaganda bullshit in order to create a narrative about yourself. have fun continuing to be a pathetic coward and achieving nothing in your life.

Hey, you read it, didntcha? It shows up in the tags, some of these posts get notes, means it works.

Everything is propaganda, dude, but whenever the West reports anything related to Ukraine it's always a David vs Goliath hero worship story. Not a "country we sponsored a coup in twice and are now turning into an arms depot like we did Afghanistan before and egged on to go fight its own people in a meaningless civil-war-turned-ethnic-cleansing vs the country whose ethnicity they are trying to cleanse".

I mean, we're already past the point where NYT admits there's open Nazis in the Ukrainian armed forces and maybe America should stop just dumping guns and Geneva Convention-banned munitions there and do something else maybe.

It's easy to paint a narrative of Russia being the terrible big bad aggressor because Western peoples were being indoctrinated into hating us since before the Bolsheviks came into power. It's harder to admit that maybe the imperialism that tore Ukraine up is American.

But you know, triple standards, yeah? Nobody went to jail over what either Bush did to Iraq, after all, despite even Bush Jr admitting it was wrong. Afghanistan is turning into a worse version of what it was before the War on Terror murdered hundreds of thousands of its civilians as a side effect, one even the UN acknowledges (still did nothing about it though, not even a teeny tiny sanction).

Not that I should mislead myself into thinking you will go do at least the bare minimum of research about the Maidan, the Azov batallion, the Minsk Agreements, the frankly ridiculous number of ties Hunter Biden seems to have to the Ukrainian economy or any of the other times the current conflict could have been stopped or outright prevented if the West wasn't pouring lies into the minds of Ukraine.

7 notes

·

View notes