#abu rayhan al biruni

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Non si può fare del bene e non si può evitare il male se non con la conoscenza.

-Abū al-Rayḥān

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The stubborn critic would say: 'What is the benefit of these sciences?' He does not know the virtue that distinguishes mankind from all the animals: it is knowledge, in general, which is pursued solely by man, and which is pursued for the sake of knowledge itself, because its acquisition is truly delightful, and is unlike the pleasures desirable from other pursuits. For the good cannot be brought forth, and evil cannot be avoided, except by knowledge. What benefit then is more vivid? What use is more abundant?

Abu Rayhan al-Biruni

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Abu Rayhan Muhammad ibn Ahmad al-Biruni a/k/a Al Biruni (973 - 1050) was an Iranian scholar and polymath during the Islamic Golden Age. He has been called the "founder of Indology", "Father of Comparative Religion", "Father of modern geodesy", and the first anthropologist.

Al-Biruni was well versed in physics, mathematics, astronomy, and natural sciences, and al distinguished historian, chronologist, and linguist. He studied almost all the sciences of his day. Royalty funded Al-Biruni's research and sought him out. Al-Biruni was influenced by the scholars of other nations, e.g. the Greeks, from whom he took inspiration when he turned to philosophy. He knew at least six languages. He spent much of his life in modern-day central-eastern Afghanistan.

In 1017 he travelled to the Indian subcontinent and wrote a treatise on Indian culture titled Tārīkh al-Hind (History of India), After exploring the Hindu faith practiced in India. He was, for his time, an admirably impartial writer on the customs and creeds of various nations, his scholarly objectivity earning him the title al-Ustadh ("The Master") in recognition of his remarkable description of early 11th-century India.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

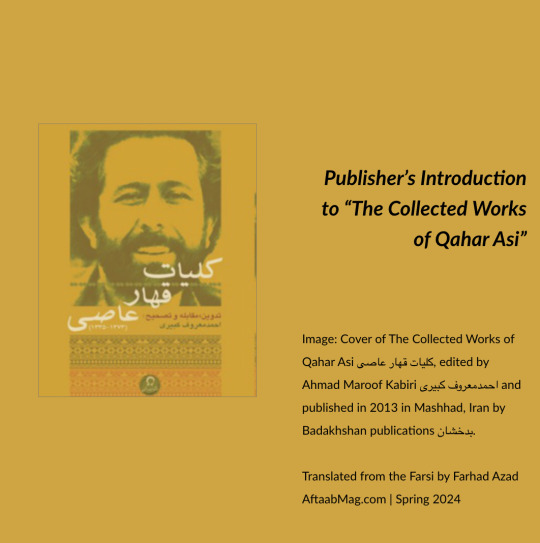

Publisher's Introduction to "The Collected Works of Qahar Asi"

Beyond the Verse: Unveiling the Man Behind the Poet

No formal biography of Qahar Asi (1956-94) exists. Yet, like a puzzle, his life can be pieced together through scattered articles, videos, interviews with colleagues and family members, and audio recordings, a few of which are available in English. In this brief exploration, I aim to illuminate the enigmatic figure of Qahar Asi, delving into critical moments of his life and his impact on contemporary Farsi poetry by sourcing an introduction to his collected works.

The 2013 publication of "The Collected Works of Qahar Asi" offers glimpses into his life. We learn of the encouragement he received from his responsive high school Farsi teacher, شیراحمد حقپناه Sher Ahmad Haqpanah, himself a poet and author.

Asi's development was further shaped by the mentorship of Sufi poet حیدری وجودی Haidari Wujodi and later his classmate نوذر الیاس Noozar Elias at دانشگاه کابل Kabul University.

After graduating, his poetry took on a decidedly political tone. It protested the Soviet occupation and, at times, offered panegyrics to the resistance, as seen in his poem مردان عشق "Men of Ardent Devotion," which he recorded a video recitation. Yet, he was bitterly disappointed when these same resistance forces entered Kabul, engaging in acts of violence, destruction, and cultural erasure.

A reviewer of this collection remarked, "One notable feature of this collection is the removal of duplicate poems that had appeared in multiple collections. Additionally, poems written in local dialects are presented in their original form, with a glossary at the end of the book explaining any unfamiliar terms."

The collection also features unpublished poems, raising questions about whether Asi intended them for print—some may be unfinished drafts, while others, perhaps deemed too radical, never passed the Kabul censors' scrutiny. The book remains a rare find abroad, and it's unclear if subsequent editions have been printed since its initial publication.

— Farhad Azad, Spring 2024

- - -

This is the editor's introduction from the Collected Works of Qahar Asi, editor's Ahmad Maroof Kabiri and published in 2013 in Mashhad, Iran, by Badakhshan بدخشان Publications:

Born in the village of Malima in Panjshir, Qahar Asi entered this world on the fourth of میزان Mizan, 1335 (September 26, 1956), into a family of modest means. After early childhood, he began his education at the village mosque, followed by formal schooling at the Tanbana elementary school at six. His family later relocated to Kabul, where Asi attended the Abu ابوریحان بیرونی Rayhan al-Biruni Middle School and لیسۀ غازی Ghazi High School.

During his high school years, Asi's poetic talents began to flourish. His teacher, Sher AhmadAsi'sanah, recognized and nurtured his budding abilities, encouraging him to write more and refine his craft. At the end of each Farsi language and literature class, Asi would share his verses, earning the admiration of his classmates. This early recognition, a testament to his raw talent, laid a solid foundation for his future as a poet, inspiring him to continue his poetic journey.

In late 1358 (late 1979), Asi met Haidari Wujodi (1939-2020), a Sufi poet and mentor whose guidance in literature and mysticism profoundly influenced him. In early 1359 (1980), Asi entered Kabul University, a pivotal environment for his poetic development. He crossed paths with Azim Herati (Noozar Elias), a poet from Herat. Asi’s mastery of the quatrain poetry forms can be traced back to Elias’ influence, evident in their shared emotional depth and evocative imagery.

By 1365 (1986), Asi's intellectual and literary development had significantly accelerated, leading to a newfound maturity in his poetry. During this period, he arose as a pioneer of protest poetry and committed himself to literature, shouldering the pain of his people and their vulnerability. He evolved into an authentic voice of their suffering, and his poetry was a raw and resolute narrative of the human cost of conflict.

On a fateful Wednesday evening in Mizan 1373 (September 1994), a rocket explosion in Kabul tragically cut short Asi's life. He embraced martyrdom, joining the ranks of those whowAsi'sd sacrificed their lives for their beliefs.

Asi’s published works, both poetry and prose, include: “The Crimson Flower Collection,” “Melodies for Malima,” “The Garden of Lovers’ Divan,” “My Ghazal and My Sorrow,” “Alone but Everlasting,” “From the Island of Blood,” “The Beginning of an End,” “Of Fire, Of Silk,” “The Year of Blood, the Year of Martyrdom,” and “The Collected Works of Qahar Asi.”

Asi’s poetry, rich in thematic depth and purpose, represents a fresh current in Farsi literature. He pioneered a bold and dynamic style, championing a more authentic and impactful art form. His verses seamlessly blend the unique spirit of his homeland with universal narratives, incorporating elements of humor, heroism, and realism. This unique blend of local and universal themes in his poetry invites the audience to connect with his work on a deeper level.

Asi’s poetic forms are diverse and varied, unrestricted by any rigid framework. He excelled in free verse and traditional classical forms, showcasing his versatility and talent. This duality in his poetical structures strengthens his poetic originality and demonstrates his exceptional capabilities, intriguing the audience with his creative approach to poetry.

In essence, Qahar Asi was a fearless poet, a true champion of the people, and a visionary who yearned for an open and humane society.

0 notes

Text

Babylonian mathematical calculation (1900 -1700 BCE)]

Marshall Islands sailing chart

Phases of the Moon: Abu al-Rayhan Muhammad ibn Ahmad al Biruni (Iranian, 973-1048)

Dublin, Ireland town plan: Patrick Abercrombie, Sydney A. Kelly and Arthur J. Kelly, (1916)

Spacetime Mathematical Diagram. Hermann Minkowski (1908)

Fruit Dish and Glass, Georges Braque (1912)

0 notes

Photo

On one side is part of the Sacred Jedi Texts, on p41 of TROS visual dictionary. A diagram of the solution to "Phases of Mortis".

On the other side a diagram of Phases of the Moon. A 1000 year old drawing by Persian scholar and polymath, Al-Biruni.

They should at least adknowledge this in canon and make a Jedi Master of the Old Republic who solved this 'theorem' have a name derived from Al-Biruni.

#star wars#star wars books#the rise of skywalker#the last jedi#the sacred jedi texts#al-biruni#abu rayhan al biruni#plagiarism#islamic golden age

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

El nacimiento de la Física parte I.

Mucho antes que el método experimental viera la luz, los científicos del pasado (llamados entonces filósofos naturales) usaban la razón para asimilar el comportamiento del universo. Esta forma de trabajo condujo a ideas que hoy son consideradas erróneas por la vastedad de la comunidad científica, como que la Tierra es el centro del universo.

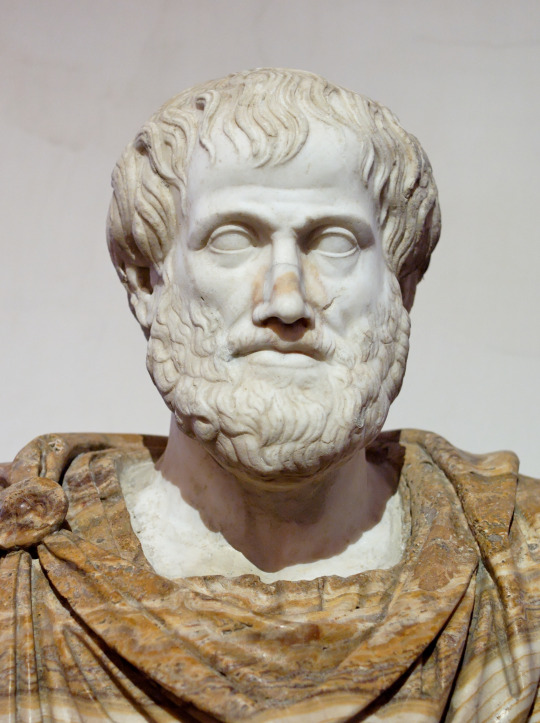

Pobres de aquellos que intentaban refutar tales ideas, ya que se oponían a lo que parecía claro para el sentido común y, más aún, a lo que aseguraban sabios indiscutibles como Aristóteles y Ptolomeo. Algunos de ellos padecieron burlas e incluso persecución, tal fue el caso de Giordano Bruno y Galileo Galilei.

La ciencia tiene como objetivo general encontrar la naturaleza real y las causas a los fenómenos que observamos. Los primeros que sabemos que intentaron explicar el mundo lejos de la influencia del misticismo fueron los griegos, en particular, Tales de Mileto; aunque Aristóteles jugó un mayor rol en esto, según varios historiadores.

Si bien es cierto que muchas de las ideas de Aristóteles no son aceptadas en la actualidad, hay que recalcar que sus esfuerzos por explicar el mundo, sin recurrir a dioses, son notables y gran relevancia histórica.

En cierto sentido, debemos las bases del método científico a Aristóteles porque, al contrario de su maestro Platón, él sostenía que la observación cuidadosa y la medición meticulosa seguida de un tiempo prudente de meditación eran la vía para alcanzar el conocimiento. Más aún, Aristóteles recomendaba “hacer una revisión de la literatura” antes de embarcarse en cualquier investigación. A raíz de esto, la biblioteca de Alejandría fue la primera en ofrecer un catálogo de biblioteca como ayuda para los investigadores de la época.

La primera propuesta de un método de investigación semejante al método científico moderno, vino de parte del mundo árabe por Ibn Al-Hassan Ibn Al-Haytham. Él propuso el siguiente sistema:1. Plantear el problema.2. Poner a prueba su hipótesis mediante experimentos. 3. Analizar los resultados y llegar a una conclusión.

Reconoció que una actitud escéptica e inquisitiva, sumada a un sistema de mediciones controlado y riguroso, eran esenciales para la adquisición del saber. Más tarde, Abu Rayhan Al-Biruni hizo notar que los resultados podrían acarrear errores debido a la imperfección de los instrumentos de medición o la falibilidad del observador. La revisión por pares se remonta hasta el médico Al-Rahwi.

Durante mucho tiempo la ciencia árabe se vio opacada por la iglesia radical, y todas aquellas ideas brillantes no fueron retomadas sino hasta el Renacimiento. En esta era Francis Bacon propuso la forma moderna del método científico, basada en el pensamiento inductivo y que partía de la negación de “ídolos” o nociones recibidas, para así abrirse a nuevos resultados.

#historia#history#science#ciencia#fisica#matematicas#physicsblr#physblr#mathblr#mathematics#studyblr

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Messenger of God: Muhammad: Part 69

The Ethos Created by the Messenger: Part 2

Islam is the middle way. Its elaborate hierarchy of knowledge is integrated by the principle of Divine Unity (tawhid). There are juridical, social and theological sciences, as well as metaphysical ones, all deriving their principles from the Qur'an. Over time, Muslims developed elaborate philosophical, natural, and mathematical sciences, each of which has its source in a Beautiful Name of God. For example, medicine depends on the Name All-Healing; geometry and engineering on the Names All-Just and All-Determiner, and All-Shaper and All-Harmonizing; philosophy reflects the Name All-Wise.

Each level of knowledge views nature in a particular light. Jurists and theologians see it as the background for human action; philosophers and scientists see it as a domain to be analyzed and understood; and metaphysicians consider it the object of contemplation and the mirror reflecting suprasensible realities. The Author of Nature has inscribed His Wisdom upon every leaf and stone, on every atom and particle, and has created the world of nature in such a way that every phenomenon is a sign (aya) singing the glory of His Oneness.

Islam has maintained an intimate connection between science and Islamic studies. As a result, the traditional education of Islamic scientists, particularly in the early cneturies of Islam, was broad enough to comprise most of the sciences of that time. In later life, each scientist's aptitude and interest would cause him or her to become an expert and specialist in one or more sciences.

Universities, libraries, observatories, and other scientific institutions played a major role in the continuing vitality of Islamic science. These, together with students who would travel hundreds of miles to study under acknowledged scholars, ensured that the whole corpus of knowledge was kept intact and transmitted from one place to another and from one generation to the next. This knowledge did not remain static; rather, it continued to expand and enrich itself. Today, there are hundreds of thousands of Islamic (mainly in Arabic) manuscripts in the world's libraries, a large number of which deal with scientific subjects.

For example, Abu Yusuf Yaqub al-Kindi (the "Philosopher of the Arabs") wrote on philosophy, mineralogy, metallurgy, geology, physics, and medicine, among other subjects, and was an accomplished physician. Ibn al-Haytham was a leading Muslim mathematician and, without doubt, the greatest physicist. We know the names of over 100 of his works. Some 19 of them, dealing with mathematics, astronomy, and physics, have been studied by modern scholars. His work exercised a profound influence on later scholars, both in the Muslim world and in the West, where he was known Alhazen. One of his works on optics was translated into Latin in 1572.

Abu al-Rayhan al-Biruni was one of the greatest scholars of medieval Islam, and certainly the most original and profound. He was equally well-versed in mathematics, astronomy, the physical and natural sciences, and also distinguished himself as a geographer and historian, a chronologist and linguist, and as an impartial observer of customs and creeds. Such figures as al-Kharizmi (mathematics), Ibn Shatir (astronomy), al-Khazini (physics), Jabir ibn Hayyan (medicine) are remembered even today. Andalucia (Muslim Spain) was the main center from which the West acquired knowledge and enlightenment for centuries.

Islam founded a most brilliant civilization. This should not be considered surprising, for the Qur'an begins with the injunction: Read: In the Name of Your Master Who creates (96:1). The Qur'an told people to read when there was very little to read and most people were illiterate. What we understand from this apparent paradox is that humanity is to "read" the universe itself as the "Book of Creation." Its counterpart is the Qur'an, a book of letters and words. We are to observe the universe, perceive its meaning and content, and through those activities gain a deeper perception of the beauty and splendor of the Creator's system and the infinitude of His Might. Thus we are obliged to penetrate into the universe's manifold meanings, discover the Divine laws of nature, and establish a world in which science and faith complement each other. All of this will enable us to attain true bliss in both worlds.

In obedience to the Qur'an's injunctions and the Prophet's example, Muslims studied the Book of Divine Revelation (the Qur'an) and the Book of Creation (the universe) and eventually erected a magnificent civilization. Scholars from all over Europe benefited from the centers of higher learning located in Damascus, Bukhara, Baghdad, Cairo, Faz, Qairwan, Zeituna, Cordoba, Sicily, Isfahan, Delhi and other great Islamic cities. Historians liken the Muslim world of the medieval ages, dark for Europe but golden and luminous for Muslims, to a beehive. Roads were full of students, scientists, and scholars traveling from one center of learning to another.

For the first 5 centuries of its existence, the realm of Islam was a most civilized and progressive area. Studded with splendid cities, gracious mosques, and quiet universities, the Muslim East offered a striking contrast to the Christian West, which was sunk in the Dark Ages. Even after the disastrous Mongol invasions and Crusades of the thirteenth century ce and onwards, it displayed vigor and remained for ahead of the West.

Although Islam ruled two-thirds of the known civilized world for at least 11 centuries, laziness and negligence of what was going on beyond its borders caused it to decay. However, it must be pointed out clearly that only Islamic civilization decayed—not Islam. Military victories and superiority, which continued into the eighteenth century, encouraged Muslims to rest on their laurels and neglect further scientific research. They abandoned themselves to living their own lives, and recited the Qur'an without studying its deeper meanings. Meanwhile, Europe made great advances in sciences, which they had borrowed from the Muslims.

What we call "sciences" are, in reality, languages of the Divine Book of Creation (another aspect of Islam). Those who ignore this book are doomed to failure in this world. When the Muslims began to ignore it, it was only a matter of time before they would be dominated by some external force. In this case, that external force was Europe. European cruelty, oppression, and imperialism also contributed greatly to this result.

The present modern civilization cannot last for long, for it is materialistic and cannot satisfy humanity's perennial needs. Such Western sociologists as Oswald Spengler have predicted its collapse on the grounds that it is against human nature and values. On the other hand, Islam has been around for 14 centuries. In addition, it is fully capable of establishing the bright world of the future on the firm foundation of its creed, ethics, spirituality, and morality, as well as its legal, social and economic structures.

#god#islam#muslim#muslimah#help#hijab#allah#ayat#quran#revert#convert#religion#reminder#hadith#sunnah#prophet#Muhammad#pray#prayer#salah#dua#convert help#revert help#islam help#muslim help#welcome to islam#how to convert to islam#new convert#new muslim#new revert

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Abu Rayhan Al-Biruni

Abu Rayhan Al-Biruni is one of the world's most celebrated polymaths. He lived during the period now known as the Islamic Golden Age (from the 8th to the 14th century). This was a time when many important inventions and developments took place that had a profound effect on the Islamic world and beyond. In fact, this period of incredible scientific development and cultural thriving had a major impact on the progress of mankind.

The Life of Abu Rayhan Al-Biruni

Born in the year 973 in Khwarazm, little is known of his early life. However, one story about Abu Rayhan Al-Biruni tells us that he also knew very little about his past. When being praised for his achievements, Al-Biruni claimed that he did not even know who his father was, far less the provenance of his family. He used this statement to make a point about praise and flattery, and this was preserved for history in a poem. Other than this, there is no evidence for what his early life or childhood might have looked like.

The prince of the district educated Al-Biruni, and he received instruction in a very wide range of subjects, including astronomy, mathematics, medicine, and the sciences (such as they were in the tenth century) as well as Islamic law, theology, and philosophy. This period of study was brought to an end when a new dynasty took over. A civil war ensued, and Abu Rayhan Al-Biruni fled eastwards. He traveled extensively and worked under the patronage of many important dynasties and aristocrats. He was frequently sought out by the wealthy and the powerful; at this time, there was a real sense of understanding that power came not only from wealth but from knowledge. Scholars and scientists were highly prized and seemed like a great asset to the ruling classes' household or court. Al-Biruni often found himself in demand, as he was called on to study under the patronage of different aristocrats. Around the turn of the century, between 998 and 1000, Abu Rayhan Al-Biruni produced a book called 'al-Athar al-Baqqiya 'an al-Qorun al-Khaliyya,' or Vestiges of the Past. This was an extensive guide to history and science.

When the Ma'munids became the ruling dynasty in 998, Rayhan Al-Biruni was one of many scientists forced to join the court of Mahmud. He was forced to settle in Ghazna, where the Ma'munids had their capital. Mahmud was a fierce ruler, and not to be crossed, so Rayhan Al-Biruni was unable to get away from the court. He became the official court astronomer. He also traveled with Mahmud's court and followed his military campaigns into India, which in turn led to the creation of some of Rayhan Al-Biruni's most famous works on the history and ethnography of India.

Very little is known about the end of Rayhan Al-Biruni's life. It is assumed that he was with the court of Mahmut until his death sometime after 1050.

Abu Rayhan Al-Biruni's Other Works

As well as his best-known books already mentioned, Vestiges of the Past and his Study of India, Abu Rayhan Al-Biruni wrote hundreds of other works, mostly on astronomy and mathematics. He also conducted many scientific investigations in many fields of scientific knowledge, including works on astronomy,

Al-Biruni studied religious philosophy and theology thoroughly, investigating many different religions, including Christianity, Judaism, Hinduism, Buddism, Zoroastrianism, and Islam. While he always found in favor of Islam and was a committed Muslim, he did approach the study of other religions with a balanced view. Even though he dedicated a significant part of his life to studying and documenting the differences between cultures and traditions, he promoted the idea that all these different cultures were related to one another.

Rayhan Al-Biruni's Achievements

Rayhan Al-Biruni's many achievements changed the way people thought and wrote about the world. He laid the foundations for scientific study that changed the world. Just a few of his most important discoveries and achievements include:

Finding a way to measure the height of the sun using a quadrant.

Being the first person to divide hours into minutes and seconds.

Applying advanced mathematical techniques to astronomical calculations.

Using mathematical techniques to further the concept of mathematical geography and utilizing these techniques to calculate the distances between cities and work out longitude and latitude.

Investigations into the earth's rotation.

Developing an observational instrument known as an astrolabe.

Recording data on equinoxes and eclipses that have proved useful to later scientists.

Investigating rudimentary physics, notably using hydrostatic balance to work out density.

Using the principles of trigonometry to make calculations, including the radius of the earth.

Theorizing on the likelihood of other landmasses' existence based on his calculations on the earth (correlating to the Americas).

Recording insights into language and linguistics (he had a working knowledge of Khwarezmian, Arabic, Persian, Sanskrit, Hebrew, Syriac, and Greek)

The Legacy of Abu Rayhan Al-Biruni

Al-Biruni's work was not appreciated in the time after his death, but it was later rediscovered by Western academics who were astounded by the breadth of study that the man had covered during his lifetime. He is widely considered one of the most important scholars to have emerged from the Islamic Golden Age. This has led to him receiving various titles such as the 'first anthropologist,' 'founder of geodesy,' 'father of comparative religion' and 'founder of Indology.' His work on India's study has become part of the country's historical record, while his work in astronomy has led to a lunar crater and an asteroid, both bearing his name. His birthday is even celebrated still as the official day of the engineer in Iran.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rindu Budaya Ilmu

Malam itu telah larut. Tapi ada sebuah rumah yang masih penuh sesak dengan para perempuan. Mereka terlihat mengelilingi seseorang. Ia muda, pipinya kemerahan, dan sangat cerdas. Wajahnya mengguratkan kelelahan, tapi ia terus-menerus berdialog dengan perempuan-perempuan lain yang mengelilinya.

Itu bukan malam biasa. Aisyah istri Nabi bermalam sebagai tamu di rumah Safiyyah binti Harits al-Abdari di Basrah. Safiyyah mengundang teman-teman perempuannya untuk datang. Mendengar kabar Aisyah sedang menginap, mereka "mengepung" rumah Safiyyah binti Harits untuk belajar dari Aisyah. Ia lah orang yang sedari tadi terus menerus berdialog dan menjawab pertanyaan.

Budaya ilmu macam apa ini? Saat itu Aisyah pulang sehabis tempur, tapi malamnya ia malah menggelar kelas hingga larut. Perempuan-perempuan yang ada di sekitar itu pun dengan semangat mengikuti kelas dadakan itu.

Jadi, Apa itu Budaya Ilmu?

Profesor Wan Mohd Wan Daud dari Malaysia berusaha menjelaskan dengan ringkas,

“Budaya ilmu adalah suatu keadaan di mana seluruh lapisan masyarakat melibatkan diri, baik secara langsung atau tidak langsung, dalam kegiatan keilmuan dalam setiap kesempatan.

Budaya ilmu juga merujuk kepada suatu keadaan di mana seluruh lapisan masyarakat berusaha memutuskan sesuatu berdasarkan ilmu, baik melalui musyawarah ataupun kajian ilmiah dahulu.

Dalam budaya ilmu, ilmu itu sendiri dianggap keutamaan tertinggi dalam sistem nilai pribadi dan masyarakat. Diri pribadi dan masyarakat sangat membenci kebodohan dan pandangan yang tidak didasari ilmu.

Budaya ilmu tidak akan terjadi jika masyarakat yang mengamalkan hal-hal di atas cuma sebagian kecil saja. Ciri-ciri di atas harus tersebar luas dan berurat akar dalam setiap lapisan masyarakat”

Budaya ilmu ini sangat terlihat jelas di negeri-negeri yang sudah maju ataupun yang tengah bangkit. Siapapun negeri itu, tak peduli siapapun mereka, budaya ilmu adalah syarat kemajuan negeri itu. Ia terlihat begitu menonjol.

Budaya Ilmu Yunani

Filsafat, logika, geometri, dan banyak ilmu lainnya adalah hasil dari pemikiran bangsa Yunani. Hasil ilmu mereka masih banyak dipakai oleh bangsa modern seperti kita, 2000 tahun setelah mereka hidup.

Robert M Hutchins, mantan Presiden University of Chicago menulis bahwa budaya ilmu Yunani begitu mengagumkan.

“Di Athena, pedidikan bukanlah satu kegiatan yang terbatas pada masa-masa tertentu, di tempat-tempat tertentu, atau pada peringkat umur tertentu. Pendidikan merupakan matlamat utama masyarakat. Kota raya mendidik manusia. Manusia di Athena dididik oleh budaya, oleh paideia.”

Budaya Ilmu Yahudi

Yahudi pun memiliki budaya ilmu yang kuat. Mungkin ada sekitar 13 juta Yahudi di seluruh dunia saat ini. Hampir setengah dari mereka tinggal di USA dan Kanada. Dan di sana, mereka banyak menguasai berbagai lembaga dan lapangan.

Tak terhitung lagi orang Yahudi yang memiliki posisi penting sehingga turut mengangkat budaya ilmu di USA dan Kanada. Mark Zuckerberg (Facebook), Henry Kissinger (Menteri), Gary Vaynerchuck (entrepreneur digital), Sergey Brinn dan Larry Page (Google), dan masih banyak lagi lainnya.

Budaya Ilmu China

Sudah sejak lama China menguasai dunia. Beribu-ribu buku telah diciptakan oleh para ahli ilmu China di zaman kuno. Lao Tze, Konfusius, dan banyak filsuf lain pun menjadikan China salah satu pusat ilmu dunia sampai sebelum zaman penjajahan Asia-Afrika. Bahkan, di zaman ini, China pun bangkit kembali menjadi raksasa dunia, melewati USA.

Budaya Ilmu India

Banyak sekali sumbangan India untuk peradaban modern. Angka yang kita kenal sekarang akarnya berasal dari budaya India yang kemudian disempurnakan oleh ilmuwan muslim al-Khwarizmi.

Budaya Ilmu Barat

Setelah Renaissance muncul, di Barat terjadi ledakan budaya ilmu. Keluarga Medici memiliki satu istana yang tiap malam menjadi tempat berkumpulnya para ahli ilmu. Di sana mereka berdiskusi, berdebat, dan mencari solusi. Galileo Galilei, Charles Darwin, Leonardo da Vinci, Marie Curie, Albert Einstein, sampai zaman Stephen Hawking, itu semua adalah ilmuwan-ilmuwan Barat yang telah mewarnai sejarah dunia.

Budaya Ilmu Jepang

Pada awal zaman Meiji (1860-80an), 30.000 pelajar berkumpul di Tokyo untuk belajar. 80% mereka berasal dari luar Tokyo. Mereka diberikan beasiswa untuk belajar. Harta itu berasal dari para tuan tana dan dermawan. Banyak di antara mereka yang bekerja paruh waktu, lalu menepuk dada dengan bangga,

“Jangan menghina kami, kelak kami mungkin menjadi menteri!”

Sampai di zaman ini, orang Jepang adalah pencandu ilmu yang sangat kuat. Budaya membaca mereka begitu kuat, sampai-sampai mereka tetap membaca di kendaraan umum seperti kereta.

Budaya Ilmu Islam

Mulainya Budaya Ilmu dalam Islam ditandai dengan turunnya ayat pertama “Iqra!” (bacalah). Maka, sejak saat itu, Nabi saw dan para sahabatnya belajar sangat giat tentang apapun. Budaya ilmu tumbuh subur.

Para sahabat nabi belajar dari Nabi di malam hari, subuh, dhuha, siang, sore, sampai Isya. Mereka bertanya kepada Nabi saw di samping sungai, kebun kurma, depan sumur, di dalam masjid, atau bahkan di perjalanan.

Nabi saw terus mendidik para sahabat di kondisi apapun, entah di kondisi peperangan, terkepung di Madinah, kelaparan, setelah selesai sholat, saat makan bersama, atau bahkan saat bersenda gurau.

Bahkan, Nabi saw bersabda bahwa menuntut ilmu untuk setiap muslim dan muslimah adalah wajib dari buaian hingga liang lahat.

Ketika Urwah bin Zubair bertanya kepada bibinya, Aisyah, kenapa ia bisa menguasai ilmu kedokteran, Aisyah menjawab,

“Saat Rasulullah menerima kunjungan dari para kabilah Arab, di antara mereka ada dokter. Beliau terus bertanya tentang kedokteran dari para tabib itu, sementara aku menguping pembicaraan itu”

Saat akan wafat, Abu Rayhan al Biruni (1048 M) masih berjawab soal tentang suatu masalah dengan sahabatnya. Sahabatnya protes, “Di saat seperti ini kamu masih belajar?”

Al-Biruni menjawab, “Aku tidak mau meninggalkan alam fana dalam keadaan bodoh, tak tahu jawaban masalah itu”

---

Inilah kerinduan saya terhadap budaya ilmu. Kita terapkan budaya ilmu di diri kita sendiri, kemudian keluarga kita, komunitas kita, dan mungkin kita akan melihat budaya ilmu itu akan diterapkan secara ramai-ramai di seantero Indonesia. Bahagianya kita. Itulah saatnya Indonesia akan lepas landas menjadi negara maju.

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Abu Rayhan al-Biruni was an Iranian scholar and polymath during the Islamic Golden Age. He has been variously called as the "Founder of Indology", "Father of Comparative Religion", "Father of Modern Geodesy" and the first Anthropologist.

#father#modern#first#mathematics#astronomy#muslim#jewish#universe#greek#physics#geography#earth#america#asia#europe#pharmacology#mineralogy#persian#indian#afghan#syriac#history#religions#judaism#islam#christianity#buddhism#hinduism#god#filinta

0 notes

Text

Abu Rayhan Al Biruni" "Muhammad", who was nicknamed "Abi Rayhan" by his mother and who would be known later by the name "Al Biruni" was passionate about science from a young age His encounter with the Greek botanist was his access to the gates of the world of knowledge

0 notes

Photo

Kartprojektioner (I av II)

1. Nicolosis klotformiga; Giovanni Battista Nicolosi 1660, efter Abu Rayhan al-Biruni ca 1000

2. Goode homolosine (interrupted); John Paul Goode 1923

3. Robinsons; Arthur H. Robinson 1963

4. Aitoffs; David A. Aitoff 1889

5. Bertins; Jacques Bertin 1953

6. Peirce quincuncial; Charles Sanders Peirce 1879

7. AuthaGrath; Hajime Narukawa 1999

8. Airocean; Buckminster Fuller och Shoji Sadao 1954, efter Buckminster Fullers ”Dymaxion” 1943

0 notes

Photo

Statue of Abu Rayhan al Biruni Tehran Iran Postcard https://ift.tt/35ojaW9. More Designs http://bit.ly/2g4mwV2

0 notes

Text

Avicenna

Pūr Sinɑʼ ( c. 980 – June 1037), commonly known as Ibn Sīnā, or in Arabic writing Abū ʿAlī al-Ḥusayn ibn ʿAbd Allāh ibn Sīnā[2] (Arabic أبو علي الحسين بن عبد الله بن سينا) or by his Latinized name Avicenna, was a Persian[3][4][5][6] polymath, who wrote almost 450 treatises on a wide range of subjects, of which around 240 have survived. In particular, 150 of his surviving treatises concentrate on philosophy and 40 of them concentrate on medicine.[7][8]

His most famous works are The Book of Healing, a vast philosophical and scientific encyclopedia, and The Canon of Medicine,[9] which was a standard medical text at many medieval universities.[10] The Canon of Medicine was used as a text-book in the universities of Montpellier and Leuven as late as 1650.[11] Ibn Sīnā's Canon of Medicine provides a complete system of medicine according to the principles of Galen (and Hippocrates).[12][13]His corpus also includes writing on philosophy, astronomy, alchemy, geology, psychology, Islamic theology, logic, mathematics, physics, as well as poetry.[14] He is regarded as the most famous and influential polymath of the Islamic Golden Age

Circumstances

Avicenna created an extensive corpus of works during what is commonly known as Islam's Golden Age, in which the translations of Greco-Roman, Persian, and Indian texts were studied extensively. Greco-Roman (Mid- and Neo-Platonic, and Aristotelian) texts by the Kindi school were commented, redacted and developed substantially by Islamic intellectuals, who also built upon Persian and Indian mathematical systems, astronomy, algebra, trigonometry and medicine.[16] The Samanid dynasty in the eastern part of Persia, Greater Khorasan and Central Asia as well as the Buyid dynasty in the western part of Persia and Iraq provided a thriving atmosphere for scholarly and cultural development. Under the Samanids, Bukhara rivaled Baghdad as a cultural capital of the Islamic world.[17]

The study of the Quran and the Hadith thrived in such a scholarly atmosphere. Philosophy, Fiqh and theology (kalaam) were further developed, most noticeably by Avicenna and his opponents. Al-Razi and Al-Farabi had provided methodology and knowledge in medicine and philosophy. Avicenna had access to the great libraries of Balkh, Khwarezm, Gorgan, Rey, Isfahan and Hamadan. Various texts (such as the 'Ahd with Bahmanyar) show that he debated philosophical points with the greatest scholars of the time. Aruzi Samarqandi describes how before Avicenna left Khwarezm he had met Rayhan Biruni (a famous scientist and astronomer), Abu Nasr Iraqi (a renowned mathematician), Abu Sahl Masihi (a respected philosopher) and Abu al-Khayr Khammar (a great physician).

Biography

The only source of information for the first part of Avicenna's life is his autobiography, as written down by his student Jūzjānī. In the absence of any other sources it is impossible to be certain how much of the autobiography is accurate. It has been noted that he uses his autobiography to advance his theory of knowledge (that it was possible for an individual to acquire knowledge and understand the Aristotelian philosophical sciences without a teacher), and it has been questioned whether the order of events described was adjusted to fit more closely with the Aristotelian model; in other words, whether Avicenna described himself as studying things in the 'correct' order. However given the absence of any other evidence, Avicenna's account essentially has to be taken at face value.[18]

Avicenna was born c. 980 in Afšana, a village near Bukhara (in present-day Uzbekistan), the capital of the Samanids, a Persian dynasty in Central Asia and Greater Khorasan. His mother, named Setareh, was from Bukhara;[19] his father, Abdullah, was a respected Ismaili[20] scholar from Balkh, an important town of the Samanid Empire, in what is today Balkh Province, Afghanistan. His father was at the time of his son's birth the governor in one of the Samanid Nuh ibn Mansur's estates. He had his son very carefully educated at Bukhara. Ibn Sina's independent thought was served by an extraordinary intelligence and memory, which allowed him to overtake his teachers at the age of fourteen. As he said in his autobiography, there was nothing that he had not learned when he reached eighteen.

A number of different theories have been proposed regarding Avicenna's madhab. Medieval historian Ẓahīr al-dīn al-Bayhaqī (d. 1169) considered Avicenna to be a follower of the Brethren of Purity.[21] On the other hand, Dimitri Gutas along with Aisha Khan and Jules J. Janssens demonstrated that Avicenna was a Sunni Hanafi.[21][21][22] However, Shia faqih Nurullah Shushtari and Seyyed Hossein Nasr, in addition to Henry Corbin, have maintained that he was most likely a Twelver Shia.[20][21][23] Similar disagreements exist on the background of Avicenna's family, whereas some writers considered them Sunni, more recent writers thought they were Shia.[22]According to his autobiography, Avicenna had memorised the entire Qur'an by the age of 10.[9] He learned Indian arithmetic from an Indian greengrocer, and he began to learn more from a wandering scholar who gained a livelihood by curing the sick and teaching the young. He also studied Fiqh (Islamic jurisprudence) under the Hanafi scholar Ismail al-Zahid.[24]

As a teenager, he was greatly troubled by the Metaphysics of Aristotle, which he could not understand until he read al-Farabi's commentary on the work.[20] For the next year and a half, he studied philosophy, in which he encountered greater obstacles. In such moments of baffled inquiry, he would leave his books, perform the requisite ablutions (wudu), then go to the mosque, and continue in prayer (salat) till light broke on his difficulties. Deep into the night, he would continue his studies, and even in his dreams problems would pursue him and work out their solution. Forty times, it is said, he read through the Metaphysics of Aristotle, till the words were imprinted on his memory; but their meaning was hopelessly obscure, until one day they found illumination, from the little commentary by Farabi, which he bought at a bookstall for the small sum of three dirhams. So great was his joy at the discovery, made with the help of a work from which he had expected only mystery, that he hastened to return thanks to God, and bestowed alms upon the poor.

He turned to medicine at 16, and not only learned medical theory, but also by gratuitous attendance of the sick had, according to his own account, discovered new methods of treatment. The teenager achieved full status as a qualified physician at age 18,[9] and found that "Medicine is no hard and thorny science, like mathematics and metaphysics, so I soon made great progress; I became an excellent doctor and began to treat patients, using approved remedies." The youthful physician's fame spread quickly, and he treated many patients without asking for payment..[15]

#Latinisation of names#Islamic theology#Islamic Golden Age#Canon of Medicine#Book of Healing#Avicenna#Allah#Ali

0 notes

Text

Eclipses and Astronomy in Islam

New Post has been published on http://www.truth-seeker.info/quran-science-2/eclipses-and-astronomy-in-islam/

Eclipses and Astronomy in Islam

By Majid Arbil

Whether it is to predict the future or looking for the signs of God, studying the skies has always been of particular interest to humans. Seven hundred years after Ptolemy’s Almagest, scholars from the Islamic Golden Age (8th century to the 13th century) delved into exploring the wonders of the universe with a passion that humanity had forgotten or reduced it to superstition.

Prophet Muhammad’s Eclipse

Prophet Muhammad (s), was born in Mecca in the Year of the Elephant, CE 569-570. His birth year got its name from an invasion by the Abyssinians, who used elephants in the assault. According to some records, it is also reported that a solar eclipse occurred during the Year of the Elephant.

In ancient times, births and deaths of leaders were correlated to celestial omens. However, Islamic theology does not accept that the eclipse was sent by God as an omen of the prophet’s birth, a doctrine that is based on another solar eclipse closely tied to Prophet Muhammad when his infant son Ibrahim died sadly on January 22, 632 CE.

Al-Mughira bin Shu’ba a companion of the Prophet narrates: On the day of Ibrahim’s death, the sun eclipsed and the people said that the eclipse was due to the death of Ibrahim (the son of the Prophet).

Allah’s Apostle said, “The sun and the moon are two signs amongst the signs of Allah. They do not eclipse because of someone’s death or life. So when you see them, invoke Allah and pray till the eclipse is clear.”

Astronomy in the Qur’an

Muslims recognize that everything in the heavens and on earth is created and sustained by the Lord of the universe, God Almighty. Throughout the Qur’an, people are encouraged to observe and reflect on the beauties and wonders of the natural world – as signs of God’s majesty.

“Allah is He, who created the sun, the moon, and the stars — (all) governed by laws under His commandment.” (Al-A`raf 7:54)

“It is He who created the night and the day and the sun and the moon. All (the celestial bodies) swim along, each in its orbit.” (Al-Anbiya’ 21:33)

“The sun and the moon follow courses exactly computed.” (Ar-Rahman 55:05)

Muslim Scholars on eclipses

Muslim scholars of the past have recorded in detail several eclipses of the Moon and the Sun, in different parts of the Muslim world. These observations are among the most accurate and reliable data from the pre-telescopic period.

Abu al-Rayhan al-Biruni (d. 1048), the famous scientist who excelled in mathematical and applied astronomy, made various observations of eclipses. In his book Kitab Tahdid nihayat al-amakin li-tashih masafat al-masakin (The Determination of the Coordinates of Positions for the Correction of Distances between Cities) he notes:

“The faculty of sight cannot resist it [the Sun’s rays], which can inflict a painful injury. If one continues to look at it, one’s sight becomes dazzled and dimmed, so it is preferable to look at its image in water and avoid a direct look at it, because the intensity of its rays is thereby reduced… Indeed such observations of solar eclipses in my youth have weakened my eyesight.”

In Afghanistan, he observed and described the solar eclipse on April 8, 1019, and the lunar eclipse on September 17, 1019, in detail, and gave the exact latitudes of the stars during the lunar eclipse.

On the solar eclipse which he observed at Lamghan, a valley surrounded by mountains between the towns of Qandahar and Kabul, he wrote:

“At sunrise, we saw that approximately one-third of the sun was eclipsed and that the eclipse was waning.”

He observed the lunar eclipse at Ghazna and gave precise details of the exact altitude of various well-known stars at the moment of the first contact.

Another account of the total solar eclipse of 20 June 1061 CE was recorded by the Baghdad historian Abu-al-Faraj Ibn Al-Jawzi (508-597 H), who wrote approximately a century after the event, in his Al-Muntadham fi tarikh al-muluk wa-‘l-umam (in 10 volumes):

“(453 H.) On Wednesday, when two nights remained to the completion of (the month of) Jumada al-Ula, two hours after daybreak, the Sun was eclipsed totally. There was darkness and the birds fell whilst flying. The astrologers claimed that one-sixth of the Sun should have remained [uneclipsed] but nothing of it did so. The Sun reappeared after four hours and a fraction. The eclipse was not in the whole of the Sun in places other than Baghdad and its provinces.”

In Western astronomy, most of the accepted star names are Arabic and can be traced back to the star catalog of the astronomer al-Sufi, known in medieval Europe as Azophi. His full name was Abu ‘l-Hussain ‘Abd al-Rahman ibn Omar al-Sufi, and he is recognized today as one of the most important scientists of his age.

Studying the cosmos is ingrained in the Qur’an which propelled the early Muslim scientists to chart the horizons and lay the foundations of modern astronomy.

The study of astronomy in Islamic countries is by no means over. In 2016 scientists in Qatar at the Qatar Exoplanet Survey announced their discovery of three new exoplanets orbiting around other stars.

References:

Precious Records of Eclipses in Muslim Astronomy and History

How Islamic scholarship birthed modern astronomy

———–

Taken with slight editorial modifications from islamicity.org

#astronomy#Eclipses and Astronomy in Islam#Faith#Featured#Islam#Islamic History#Prophet Muhammad#quran#science

0 notes