#Nikolai Plastov

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

Николай Аркадевич Пластов | Nikolai Arkadevich Plastov – Интерьер | Interior (1968)

“Interior” by Nikolai Plastov (1968)

#Николай Аркадевич Пластов#Интерьер#живопись#soviet art#1960s#Interior#Nikolai Plastov#Sowjetunion#art#painting#Kunst#Malerei#peinture#SSSR#Советский союз#USSR#UdSSR#СССР

288 notes

·

View notes

Photo

‘Portrait of Nikolai Volkov’, as painted by Russian painter Arkadi Plastov (1893-1972).

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

TANGLED HIERARCHIES: remnants, collective endurance and strange loops

Essay by Sunshine Frère

A strange loop is a phenomenon that occurs when someone, or something, moves either upwards, downwards or through multiple levels of an abstracted hierarchical system. At some point, moving through the system, the person or thing doing the moving, unexpectedly arrives back where they or it started. MC Escher's Lithograph, Drawing Hands (1948) illustrates this concept in a succinct manner. These types of experiments form what author Douglas Hofstadter describes as a tangled hierarchy, “a complex system where beginning and ending are undefined, and even the direction or movement of a system is not apparent”i.

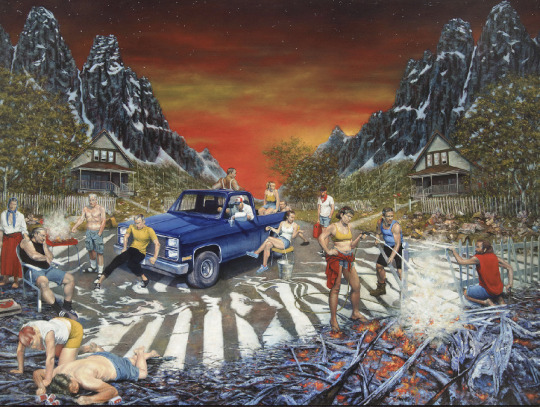

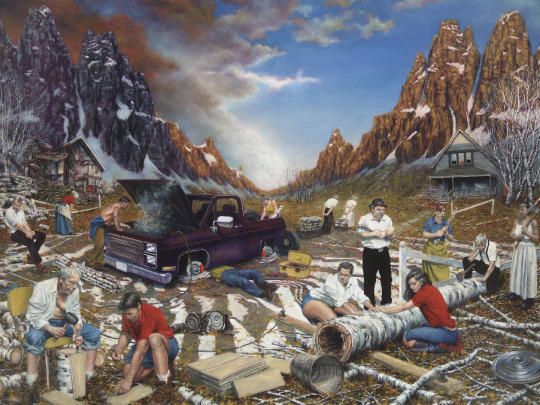

The Course of a Distant Empire, is an installation by artist Jay Senetchko, it consists of five large-scale paintings. The artist invites the viewer to navigate a maze of strange loops within this series. Tangled hierarchies of communal polytely and historical referencing, conflate past, present and future. All tenses collide, forming a cacophonous vortex.

A cluster of human figures feature prominently in all five paintings, the majority of them carve out a large elliptical shape in the foreground on each canvas. The group is not exactly a unified anomaly, they are more of a loose configuration of active beings, in close proximity. Process and polytely feature overtly; each individual, or small group, is focussed on the completion of a particular task: the removal of debris, the building of a fence, barbecuing, thinking, clearing snow, or even, simply relaxing. What we observe is a collective of people working, but not necessarily symbiotically towards a common goal. This central foregrounded space is simultaneously everyone's, and yet, also, no one’s; a busy commons of sorts where intertwined cycles of action and non-action recur throughout the seasons. An interesting tension is established between the individual and the collective in this series.

A sea of red poppies coats a huge portion of the surface of What the Thunder Said, a bewitching depiction of summer. The people of the commons perform contemplative gestures, relaxing on a blanket, stopping to chat, daydreaming. Traces of productivity hang in the air, the laundry is being put out to dry, truck parts, buckets and fan belts are left in limbo - part of a project that is finished, or something to start, it is not clear. This scene is arguably the most pastoral of the series; visual tropes form tethers that connect it to genre painting and even abstraction. Senetchko's colour palette, particularly in reference to the clothing on the figures, is a nod, not only to Malevich's abstract Peasant Paintings, but also to genre painters like Pieter Brueghel the Elder, and Ukrainian painters such as Nikolai Pimonenko and Vladimir Makovsky. Nature is in all its splendour at this point in the painted polyptych cycle; bright blossoms, lush greenery, and a big blue sky demonstrate the season's awe-inspiring presence.

A Game of Chess features many work strategies unfolding. Someone examines a smoking truck engine, whilst others transform tree trunk cut-offs into shingles, and others still, stack and roll away log piles. Nearly everyone is focussed on a productive task, preparing for the winter ahead. As a sun sets over a crisp sky, autumn casts a shadow into the valley. Productivity also runs throughout Death By Water. Most individuals are working away; there is an attempt to revitalize the melted cross-walk, and to salvage parts from the truck. Someone is framing up a house, whilst someone else is sowing seeds in a field in the distance in preparation for spring.

Both of these paintings are haunted by a past genre of themselves. In socialist realism, painters portrayed daily life in a celebratory manner propagating life under communist rule as idyllic; paintings often featured a happy and productive proletariat. Ukrainian and Russian painters such as Arkadiy Plastov and Tatiana Yablonskaya depicted farming folk hard at work and loving every minute of it. Senetchko used found imagery of Ukranian immigrants, as well as Ukrainians working in the Carpathian Mountains as source material for some of his figures. Productivity is infused in the painting as is pastoralism, but the sentiment of joyful labour has been subsumed by a practical and pragmatic focus. The artist introduces disparity as a harbinger of reality in these works. Absent in socialist realist painting is the messiness of productivity which is amply represented within Senetchko's work. The remnants of failed attempts are multifarious: a smoking truck, a broken down fence, the fragments of a collapsed house, old parts and tools strewn about. The neat and orderly fashion of production lines is eclipsed with a chaotic bric-a-brac collection of objects and individuals working through specific tasks, often in too-close-for-comfort proximity.

There is a vibrancy of colour found in The Fire Sermon. The painting's blood red sunset suggests the peak of summertime, heat is felt throughout the composition. It can be found in the glowing embers of a smouldering fire and in the watery white lines of a melted cross-walk. The colour red is peppered throughout, found on a jerry-can, clothing, beer cans and a barbecue. In this work, individual appearances are at their most contemporary. Clothing design coupled with the way items are worn, serve as queues that speak to our present everyday. A tangled hierarchy presents itself in the form of understanding action and inaction within the painting. Is the fence being built, or taken apart? Are people waiting to go somewhere, or just arriving? What is going on with the scattered back lawn detritus, the result of a big party, or simply collective negligence over time? Transformation subsists in a tangled manner as well, represented in the form of the between states of the objects scattered throughout the composition.

In the heat of the summer, a tiredness and sense of boredom permeate. The individuals depicted in The Fire Sermon seem disconnected to a greater degree than any of the others in this series of paintings. Lost in solitary thought, passed out, and minimally engaged in menial chores; there is a lot of waiting and hanging around. This particular piece finds some roots within social realismii; individuals perform mundane tasks, and apathy prevails. Excess is reflected in overindulgence with alcohol, the pile of burning timber, the melted cross-walk and carelessness with cleaning up after oneself. These signs serve as subtle indicators signalling the demise of the immediate surrounds, and also, perhaps the planet and humanity itself. Reality has seeped onto the canvas, leaving one to wonder... are boredom and apathy coping mechanisms for survival in today's world?

The Burial of the Dead is the only painting where the group of individuals appear to be working collectively towards a common goal. This is also the only painting where the entire group is uniformly clad. Dark snow suits contrast against the white snow and grey-blue sky; the suits share a resemblance to biohazard outfits, we do not see skin, faces or hair: all is covered up. Nearly everyone is facing away from the viewer. It seems just as likely that these people are on a quest to find the source of an outbreak. A pile of debris burns off on the side of the open area, the houses that once stood so tall and majestic in the background have collapsed, or been dismantled: relics of a previous civilization. One cannot say if the state of the scene occurred through human intervention, natural decay or negligence. Paralleling the clothing and individual uniformity, the landscape is unified under a blanket of snow. The cold presence of winter is ubiquitous: frozen mountains, frosted trees, icy sky, and a barren snow capped truck.

Senetchko's Course of a Distant Empire, series cycles through the canon of painting, merging genres, and coalescing time. Seasons and states of being act as pendulum swings, propelling eyes back and forth, over the polyptych spread. Several additional elements in this series invoke a non-linear way of reading the painting suite. These reinforce the set of strange loops that pirouette across the series, giving poly-rhythm to the work.

In all works of this series, landscape and perspective remains uniform, the mountains, stacked like bookends on either side of the sky, loom large. Line the series up in a row, side by side, and the peaks and valley of each painting form an undulating wavelength that has no endpoint or beginning. Circularity and repetition is prevalent across the suite. From the earth's seasonal rotation and the constant fluctuating state of projects to the recurring placement of circular items, such as tires, buckets, hubcaps, and logs. Beginnings and endings integrate into multiple recursive loops.

Doubling occurs frequently in this series: twin houses, twin peaks, couples sitting together, people working in pairs, the lines of a white fence next to the white lines of a crosswalk. A contrapuntal cadence further expands the series, parallel dimensions open as past and future are projected simultaneously.

Quite possibly the most salient strange loop within this suite is the symbolism and life-cycle of the pick-up truck. It is a haunting talisman that stays the course. In spring, the truck appears as an abandoned red husk. Its mechanical components spread across the painted foreground like excavated bones. In fall, now purple, the truck is running, but its eventual demise is foretold. In summer, the truck is depicted in two extreme states: in pristine condition, and also as a long abandoned relic where nature staged a coup on its core, flowers blossom and cascade outwards from both the engine and interior cavities. The state of the truck in winter is indiscernible; pillows of snow hide a large portion of the body. It seems likely that the snow removal is occurring so the vehicle can be used. In this series, which constantly reconfigures activities and individuals, the truck remains a constant; however, unlike the stoic and seemingly unchanging mountains, it is an entity of fluidity. It serves as an anchor in the paintings, a primordial symbol of life, death and change.

Senetchko also incorporated the truck an abstracted homage to Théodore Géricault's Raft of Medusa. He references Géricault's triangular composition, particularly notable in The Fire Sermon painting. Géricault's pyramid composition alludes to the struggle of man and nature; the figures within each triangular grouping representing either rescue and salvation, or death and tragedy. Senetchko sees the truck a both raft and lifeline, for him the characters on the truck are: “the survivors of a societal shipwreck, riding a conspicuous symbol of mobility.” The pick-up thus becomes a problematic vessel of salvation. In The Course of a Distant Empire, salvation is not always what it seems. The pick-up's transformation loop, through which it is absorbed back into nature by way of deconstruction, decomposition and growth, emphasizes the impact and indifference between mother nature and humanity. Senetchko guides us into murky territory, salvation comes in crashing waves, with one crest threatening human annihilation, the following one promising human ingenuity. Then, yet another wave crashes down, in swirls planetary collapse, followed by an undulation of mother nature's resilience.

Senetchko's series title connects back in time to Thomas Cole's The Course of Empire, a five-part painted series focussed on pastoralism as the ideal phase of human civilization. In his era, Cole was known to have quoted Lord Byron's Canto IV when promoting his series to his contemporaries. A verse from Byron's canto eloquently highlights history's own strange loop:

There is the moral of all human tales;

'Tis but the same rehearsal of the past. First freedom and then Glory – when that fails, Wealth, vice, corruption – barbarism at last. And History, with all her volumes vast, Hath but one page...

Senetchko's series is also intertwined with the words of a modern writer. T.S. Eliot wrote Wasteland, an abstract poem that teeters between healing transformation and grim breakdown. The titles of each painting by Senetchko correspond to the five chapter titles found within this modernist poem. Hundreds of literary, historical and British societal references form their own interconnected web of strange loops within Eliot’s poem. Many have written about and attempted to decode it, line by cryptic line. With the lens of the present, Eliot's work is modernist triumph of hybridity. Sampling, references and appropriation collectively form both old and new meaning. The constant switching, transforming and reintegration of ideas, has an immediate resonance within our current world, where all forms of culture are endlessly cut up and collaged back together again.

This perpetual assemblage style of investigation is fascinating and hypnotic: it captures the attention of virtually all of society, keeping everyone fully distracted. As much as we are provided with limitless possibilities, we are also paralyzed by the power of too much choice, too many products and channels, and way too many opinions. Senetchko's expansive investigation into our contemporary condition essentially distils this cut-copy-paste schism down to a critical intimation. One best illustrated by one of the last lines found within Elliot's Wasteland:

These Fragments I have shored against my ruins

Senetchko's characters are practical, resourceful and resilient. But they are also wasteful and lazy; no one is perfect. Through historical tropes and visual representation, these individuals reflect a heartiness. It is this pragmatism that sustains across the series, used as a tool to combat the senselessness of life. One can see repeated attempts to decode meaning by keeping things in motion. Senetchko plays with excess, there is often detritus hanging about, but there is no real superfluity in the objects strewn from here to there. The objects are often utilitarian in nature, we primarily see industrial objects and items that could be reintegrated into other systems. Salvaging and scavenging the left-overs from previous states of existence is prevalent throughout the polyptych. A pragmatic approach that we are hard pressed to find in the buy more, buy new, buy now world that teems with products, platforms and patents at every corner. Just as with Eliot, Senetchko's characters are shoring found fragments against their ruins. The fragments are not lost - not forgotten - they are collected, stored and eventually reintegrated within the tangled hierarchy of this ever-unfolding strange loop.

But we cannot do it all at once; it is a sequence. An unfolding process.

We can only control the end by making a choice at each step.

-Philip K. Dick, The Man in the High Castle

**originally published in conjunction with Jay Senetchko’s exhibition: The course of a Distant Empire in the fall of 2017.

i Douglas Hofstadter, “I Am a Strange Loop”, (New York: Basic Books, 2008)

ii It should be noted that Senetchko's work incorporates elements of both socialist realism and social realism.

Socialist Realism: patriotic in its intentions, this is a genre that glorifies socialist/communist values in the depiction of daily life of the proletariat

Social Realism: paintings that are intended to reflect the current state of working class and poor members of society - without the rose coloured glasses. An intentionally realistic and often critical portrayal of society

ARTWORKS REFERENCED IN ESSAY:

Drawing Hands, 1948, Lithograph, MC Escher

Girls in A Field, 1928-1929, Kazimir Malevich (left)

Harvest Gathering in the Ukraine, 1896, Mykola Pymonenko (right)

De bruiloft dans in de open lucht (Wedding Dance in the Open Air), c1566, Pieter Bruegel the Elder (left)

Peasant Dinner in the Harvest, 1987, Vladimir Makovsky (right)

Getting Ready to Harvest, 1960, oil on canvas, Tatiana Yablonskaya

Grain, 1949, oil on canvas, Tatiana Yablonskaya

The Raft of Medusa, 1818, Théodore Géricault, oil on canvas, 193.5 x 282”

The Course of Empire Paintings, Thomas Cole, oil on canvas, 1834-1836:

Savage State, The Arcadian Pastoral State, The Consummation of Empire, Destruction, Desolation

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Illustration by Nikolai Plastov from the book “Winter Pictures” (author Georgiy Ladonschikov), 1956

#Book Illustration#book art#winter#snow#1950s#children's books#soviet union#soviet#ussr#russia#history#photography#vintage#retro

226 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“Interior” by Nikolai Plastov (1968)

288 notes

·

View notes