#Holzmaden Germany

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

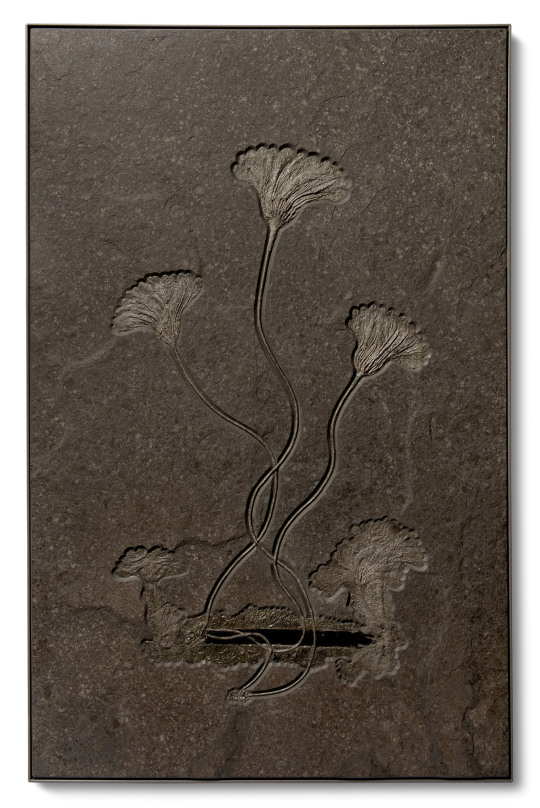

A FOSSIL SEA LILY PLAQUE Holzmaden, Germany

From the Jurassic (circa 208 to 146 million years ago), this pair of pyritised Seirocrinus subangularis with largest crown measuring 10-inches in width, in slate matrix, the edges cut straight.

607⁄8 x 331⁄4 x 11⁄4in. (154.6 x 84.5 x 3.2cm.).

Crinoids, also known as sea lilies or feather stars, are examples of living fossils. They belong to the phylum Echinodermata, and are distantly related to the starfish, brittle star and sea urchin. Filter feeders, with crowns of pinnules that trap microscopic particles on which to feed, they sway back and forth on the ocean floor. Their fossil remains are found all over the world, but most beautiful and best preserved examples are those from the Posidonia shale beds of Holzmaden in southern Germany. The strong dark colour of the shale matrix serves as a beautiful background to the delicate serpentine neck of the fossil, highlighted by the subtle shimmer of pyritisation. The matrix itself has been prepared, to better the contrast with the superb three-dimensional detail of the fossil itself which stands out in high relief.

#A FOSSIL SEA LILY PLAQUE#Holzmaden Germany#jurassic period#pyritised Seirocrinus subangularis#sea lilies#feather stars#fossils#archeology#archeolgst#history#history news#ancient artifacts#nature

75 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Fossil Sea Lily Plaque, From the Jurassic (248 - 146 million years ago),

Holzmaden, Germany,

The multiple specimens of Seirocrinus subangularis displaying fine detail and elegantly positioned in the slate matrix, displaying the fossilised flotsam wood to which they would have been anchored in life, the crown of the largest specimen measuring 11 inches, the matrix cut square to form large plaque, in metal frame.

66 x 42 x 21⁄2in. (167.5 x 106.5 x 6.5cm.)

Courtesy: Christie’s

#art#fossil#sea lily#lilie#germany#jurassic#holzmaden#seirocrinus subangularis#matrix#history#christie's

830 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Sea Lily (Crinoid) fossil (Seirocrinus subangularis) - Holzmaden, Germany - Jurassic (248-146 million years ago)

5K notes

·

View notes

Text

Holzmaden Crinoid - Seirocrinus subangularis. Lower Jurassic - 180 million years old From Germany

photo: fossilrealm

Geology Wonders

269 notes

·

View notes

Text

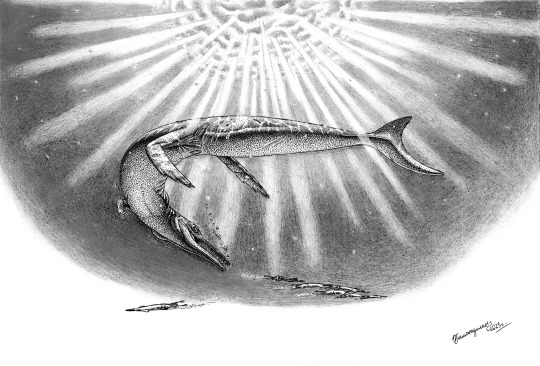

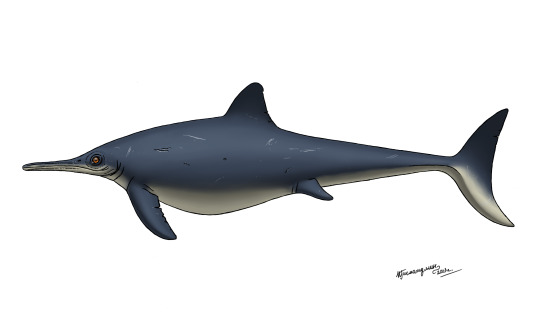

In the spring of last year, I made several color reconstructions of marine reptiles for a thesis and presentation (it was about the reconstruction of marine reptiles) for a conference that was held in Ulyanovsk in September. The drawings were done in ballpoint pen (lineart) and Paint Tool Sai 2.0 (shadows and colors).

The first is reconstruction of Mixosaurus cornalianus, a widespread small Triassic ichthyosaur. I had already drawn a Mixosaurus in water earlier and even wanted to use it in the article, but later changed my mind, deciding that lateral reconstruction would better convey the appearance of soft tissues. This earlier drawing can bee seen here:

Both pieces are based on the fin impressions described in 2020 from a specimen found in the Middle Triassic rocks of the Bezano formation, Italy (www.researchgate.net/publicati…). This specimen has preserved the tissues of the dorsal and caudal fins. Both prints have thin collagen filaments, and at the base of the caudal fin, it was possible to detect the remains of smooth, scaleless skin. The fins have a triangular shape, and the dorsal one is associated with 15-23 trunk vertebrae. In other words, its position turned out to be more

forward then in reconstructions done before his paper.

The second is lateral reconstruction of the metriorhynchid Cricosaurus albersdoerferi, belonging to a widespread genus that inhabited the shallow seas of future Europe, Central America and Argentina. It was not a particularly large animal, reaching from 2 to 3.2 meters in length. Like the first reconstruction of a Cricosaurus, which I performed in the spring, this drawing is based on a specimen that preserved a large volume of soft tissue on the tail (upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia…). Also shown here is the salt gland in the antorbital fenestra, the presence of which was previously indicated in Cricosaurus araucanensis and Dakosaurus andiniensis. The spring work with C. albersdoerferi can be seen below:

Plesiosaurs are mentioned too. This is reconstruction of the polycotylid Mauriciosaurus fernandezi from the Late Cretaceous of Mexico. A complete reptile skeleton preserved in fine-grained rocks was described by a team of paleontologists in 2017: www.researchgate.net/publicati… There are five types of soft tissue imprints around the bones. Among them are dark material, probably left from the walls of the peritoneum, dark gray traces of blubber and impressions of possible small scales. The impressions show that the animal's belly was covered with rectangular scales, which were mixed with inclusions of small fragments closer to the limbs. The scales of the living reptile were almost indistinguishable, so that the skin looked smooth. This beautifully preserved specimen showed that plesiosaurs had much more soft tissue than previously thought. The tail was especially fleshy. Fat deposits created a smooth, streamlined shape, ideal for an agile swimmer.

The last thesis drawing is this reconstruction of the famous Early Jurassic ichthyosaur Stenopterygius quadriscissus. Many of its skeletons of amazing preservation were found in the fine-grained limestones of Holzmaden, Germany. Some of them were discovered back in the 19th century, which made it possible to quickly correct previous ideas about ichthyosaurs. The Stenopterygius specimens retained soft tissue prints in the form of a bacterial film, which made it clear that they were fish-like creatures with a dorsal fin and a crescent tail. They re still attract the attention of researchers. In 2018, the skin structure of one partial specimen was studied: www.researchgate.net/publicati… A fossilized blubber was described, similar in microstructure to that of marine mammals and leatherback turtles. This led to the conclusion that ichthyosaurs were reptiles with a high metabolism, which required fat insulation. Blubber allowed ichthyosaurs to travel across the oceans, swimming even into the cold polar waters. In addition, this Stenopterygius had pigment cells - melanophores. They were absent on the ventral side, which means that the Stenopterygius had a dark back and a light belly. This countershading coloring is typical of today's marine vertebrates and serves as a camouflage.

I did also three works in fully traditional style, with pens and pencils, but I'll show them in the separate post. :)

#mixosaurus#stenopterygius#ichthyosaurs#cricosaurus#metriorhynchidae#mauriciosaurus#polycotylidae#plesiosaur#mesozoic marine reptiles#paleoart

31 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Dactylioceras ammonites from Holzmaden, Germany

75 notes

·

View notes

Note

using this as an excuse to show rocks. i dont have my entire collection bc its packed away w my school apartment stuff right now but here's some favorites of what i do have:

mica schist (my fav rock!) its really hard to show mica on camera but this SHINESSS like crazy she's so beautiful

ammonite fossil from holzmaden quarry near where i grew up in germany. you pay like 6€ and give you a pickaxe and you run wild. i did this yearly for like 7 years of my life so i have quite a collection of these

third one is slag but its awesome - my brother hoarded this for forever thinking it was some kind of cool rock and gave it to me to identify last year and i had to be like "umm its slag!" but i think its still cool even if a piece once broke off and stabbed me

On average, how many rocks do you collect on a field trip before your bag is too heavy and you have to resist the Urge?

who is this.. come french me NOW....

you get me. it's a ridiculous amount.. i did a northern arizona trip last fall and returned home with an obscene amount of rocks. i fear when i do field camp at the end of my degree i'll have to bring an entire extra bag just to fit all the rocks. i don't even have anywhere to display them! i keep them in ziplocs labeled with the trip date and approx. location! i'm completely incapable of resisting the urge though i just collect forever and ever and make it later me's problem

3 notes

·

View notes

Video

tumblr

astoneforeveryhome

Fossil Friday! Hot off the 180 million year old geologic press, this pyritized ammonite from the famous Holzmaden shale layer in Germany has one mighty fossil surrounded by many smaller dactylioceras ammonites 😍 it even has a pre-drilled hole in the back for wall hanging

#fossil#fossils#fossilfriday#ammonite#pyrite#holzmaden#shale#geology#germany#video#instagram#the earth story

185 notes

·

View notes

Photo

A scene from the Posidonia Shale (Holzmaden, Germany, ~180mya) featuring a wide variety of life.

#paleoart#holzmaden#posidonia shale#germany#campylognathoides#pterosaur#seirocrinus#crinoid#meyerasaurus#rhomaleosaurid#temnodontosaurus#stenopterygius#ichthyosaur#nature#extinct#animal#fossil#ocean#aquatic#marine#underwater#prehistoric#harpoceras#ammonite

149 notes

·

View notes

Text

Understanding Fossil Fuels through Carnegie Museums’ Exhibits

by Albert D. Kollar, Collection Manager, with assistance from Suzanne Mills, Collection Assistant, and Joann Wilson, Volunteer Section of Invertebrate Paleontology

The exhibits of Carnegie Museum of Natural History and Carnegie Museum of Art are ideal for a multidisciplinary study of fossil fuels in Pennsylvania and beyond. Such a study must properly begin with some historical background about the landmark Oakland building that houses both museums, as well as some background information about fossil fuels.

When the Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh opened in 1895, the architects, Longfellow, Alden, and Harlow incorporated roof skylights for maximum daytime lighting in the Italian Renaissance designed building¹. Nighttime activities were illuminated by interior gas lighting fixtures, possibly supplied by the Murrysville gas field, which began production in 1878. With the opening of the Carnegie Institute Extension in 1907, the Bellefield Boiler Plant was built in Junction Hollow to supply in-house steam heat and electricity from bituminous coal¹. From the 1970’s, coal and natural gas had been used to heat the boilers that supply heat to the Oakland Campus, Phipps, the University of Pittsburgh and the Oakland hospitals. In 2009 coal was eliminated as a fuel source. Electricity on the other hand, is supplied through Talen Energy from multiple sources (coal, gas, and renewable energy sources). For the future, Carnegie Museums of Pittsburgh plans to receive its electricity from renewable solar energy via Talen Energy².

What are Fossil Fuels?

Coal, oil, and natural gas (methane), known collectively as fossil fuels, are sources of energy derived from the remains of ancient life forms that usually are found preserved in coal rock, black shale, and sandstone.

Figure 1.

Coal is a rock. The coalification process starts from a thick accumulation of plant material in reducing environments where the organic matter does not decay completely. This deposit of plant residue that thrives in freshwater swamps at high latitudes forms peat, an early stage or rank in the development of coal. With the burial of peat over geologic time and a low temperature form of metamorphism produces a progression of the maturity or “rank” of the organic deposits that form the coal ranks of lignite, sub-bituminous, bituminous, and anthracite³ (Fig. 1). The Pennsylvanian Period was named for the rocks and coals of southwestern Pennsylvania that formed more than 300 million years ago.

Oil and natural gas, collectively known as hydrocarbons, were forming in the Devonian rocks of Pennsylvania between 360 and 390 million years ago. These hydrocarbon deposits or kerogens are made of millions of generations of marine plankton and animal remains that accumulated in a restricted anoxia ocean basin that extended from southern New York, through western Pennsylvania, northern West Virginia to eastern Kentucky⁴. The thick layers of sediment formed black shales or mud rocks such as the Marcellus Shale. Black shales are rich in oil and gas and are called source rocks. Sandstones such as the Oriskany Sandstone that is older than the Marcellus Shale is a reservoir rock. An amorphous mass of organic matter or kerogen undergo complex geochemical reshuffling of the hydrocarbon molecules first with burial then by thermal “cracking” as heat and pressure through the geologic process of metamorphism over millions of years transform kerogen into modern day fossil fuels⁴.

Fossil Fuels in Modern Society

As commodities converted to fuels for our modern world, these resources account for 80% of today’s energy consumption in the United States⁵. All three fossil fuels, in furnaces of vastly different design, have been used to directly heat homes, schools, workplaces, and other structures. In power plants, all three have been used for generating electricity for lighting, charging mobile phones, and powering computers, home appliances, and all manner of industrial machines. In the United States, coal became the country’s primary energy source in the late 1880s, displacing the forest-destroying practice of burning wood. It ceded the top spot to petroleum in 1950 but enjoyed a late-20th-century renaissance as the primary fuel for power plants⁵. Coal now generates approximately 11% of our country’s supply down from 48% just 20 years ago. Natural gas is currently used to generate approximately 35% of US electricity supplanting the use of coal⁶. While petroleum is less than1%⁶.

Transportation accounts for approximately 37% of total energy consumption. Coal played an historic role in powering railroads, and both compressed natural gas and batteries (charged with electricity generated from various sources) are of growing importance, however, refined oil products currently power 91% of the transportation sector⁶.

Figure 2.

In the early 20th century, scientists warned about how the burning of coal could create global warming in future centuries by raising the level of carbon dioxide, a greenhouse or heat-holding gas, in the atmosphere. (Fig. 2). It took less than a century for evidence to mount of climate change associated with the burning of fossil fuels, the clearing of forests associated with industrial scale livestock production, and from waste management and other routine processes of modern life. In recent decades headlines have routinely proclaimed the risks of a warming planet, including damage to terrestrial ecosystems, the oceans, and a rise in sea level⁷.

Fossil Fuels and Museum Geology Displays

When architects Frank E. Alden and Alfred B. Harlow designed the Carnegie Institute Extension (1907), they incorporated Andrew Carnegie’s vision to create an introduction hall to the museum named Physics, Geology and Mineralogy⁸. This hall (the forerunner to Benedum Hall of Geology) was intended to introduce Pittsburghers to the regional natural history subjects of geology, paleontology, and economic geology (fossil fuels)⁹.

Figure 3.

In the 1940s, the 300-million-year-old Pennsylvanian age coal forest diorama was installed in a corner space of what is now part of the Benedum Hall of Geology (Fig. 3). Because coal converted to coke is a vital ingredient in steel production, this three-dimensional depiction of the conditions under which Pittsburgh’s economically important coal deposits formed was (and remains) an important public asset.

Figure 4.

In 1965, as part of an overall plan to bring more of the natural history museum’s fossil collection to the public, Paleozoic Hall opened with funding from the Richard King Mellon Foundation¹⁰. This exhibition featured nine dioramas that recreate the ancient environments through 290 million years of Earth history. Sadly, only one of the nine units remains on display, the diorama depicting the Pennsylvanian age marine seaway (Fig. 4), in the Benedum Hall of Geology.

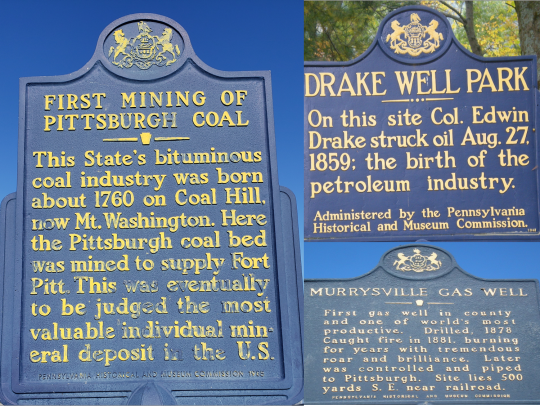

Since the Benedum Hall of Geology opened to the public in 1988 the exhibition has featured an economic geology component with displays explaining differences between coal ranks Lignite coal to anthracite coal, and a variety of Pennsylvania’s crude oils and lubricants processed from the historic well Edwin Drake drilled in Titusville in 1859 (Fig. 1 )¹¹.

Figure 5.

Today, the Hall’s “strata wall,” a towering depiction of some of the rock layers found thousands of feet below western Pennsylvania, is in my opinion, an under-utilized display in terms of conveying information about fossil fuels. Although the wall is not currently documented with any geologic information, minor changes might allow visitors to use the lens of rock strata to better understand historical events such as the Drake Well, and economically important geologic reservoirs such as the Marcellus Shale (the second largest gas deposit in the United States), the natural gas storage reservoir of the Oriskany Sandstone, and the gas and liquid condensate (ethane) extracted from the Utica Formation (Ordovician Age) for making plastic products at the Shell Cracker Plant in Beaver County, PA (Fig. 5).

Figure 6.

Elsewhere in the museum, visitors can learn more about the topic of fossil fuels at several other locations. At the Holzmaden fossil exhibit in Dinosaurs in Their Time, there is a large fossil crinoid preserved in a dark gray limestone of Jurassic age, that represents a reservoir of crude oil in Germany (Fig. 6). At the mini diorama of the La Brea tar pits, oil seeps from natural fractures from an approximately six-million-year-old rock of Miocene age, to the unconsolidated surface sediment in what is now part of the City of Los Angeles (Fig. 7).

Figure 7.

Looking for Fossil Fuel Evidence in Art

In 2018, I reviewed 58 landscape paintings and the John White Alexander wall murals on the first and second floors of the Grand Staircase within Carnegie Museum of Art (CMOA) galleries to look for artistic documentation of what I interpreted to be causes for climate change based on the science. I found many examples based on the use of coal as a fossil fuel for power and coking in steel mills and the natural formation of bio-methane as portrayed in ecosystem landscapes of the industrial age of the middle 19th and early 20th century¹².

Figure 8.

Figure 9.

Searching for the CMOA landscapes paintings takes a little patience, but the visitor is rewarded by taking a new look at some of the art museum’s classic paintings (Fig. 8 and 9).

Figure 10.

Within day trip visiting distance of Carnegie Museums are historic plaques highlighting the discovery of coal on Mount Washington, natural gas in Murrysville, and oil in Titusville, Pennsylvania. (Fig. 10). At all three stops you’ll have a better understanding of the significance if you begin your investigation of fossil fuels at Carnegie Museums.

Albert D. Kollar is the Collection Manager for the Section of Invertebrate Paleontology. Suzanne Mills is the Collection Assistant and Joann Wilson is a volunteer Section of Invertebrate Paleontology.

References

1. Kollar, A.D. 2020. CMP Travel Program and Section of Invertebrate Paleontology promotes the 125th Anniversary of the Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh with an outdoor walking tour. https://carnegiemnh.org/125th-anniversary-carnegie-library-of-pittsburgh-outdoor-walking-tour/

2. Personal communications Anthony J. Young, Vice President (FP&O) Carnegie Museums of Pittsburgh.

3. Brezinski, D. K. and C K. Brezinski. 2014. Geology of Pennsylvania’s Coal. PAlS Publication Number 18.

4. Geology of the Marcellus Shale. 2011. Brezinski, D.K., D. A. Billman, J.A. Harper, and A.D. Kollar. PAlS Publication 11.

5. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-05-03/coal-consumption-in-the-u-s-declines-as-natural-gas-solar-wind-energy-rise

6. United States Energy Agency (EIA) 2019.

7. Bill Gates. 2021. How to Avoid A Climate Disaster.

8. Kollar et al. 2020. Carnegie Institute Extension Connemara Marble: Cross-Atlantic Connections Between Western Ireland and Gilded Age Architecture in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. ACM, 86, 207-253.

9. Dawson, M. R. 1988. Benedum Hall of Geology. Carnegie Magazine, 12-18.

10. Eller, E. R. 1965. Paleozoic Hall. Carnegie Magazine, 255-338.

11. Harper and Dawson 1992. Benedum Hall-A Celebration of Geology. Pennsylvania Geology, 23, 12-15.

12. Kollar et al. 2018. Geology of the Landscape Paintings at the Carnegie Museum of Art, a Reflection of the “Anthropocene” 1860-2017. Geological Society of America, Abstracts with Programs, v. 49, 243.

33 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Rare fisch from Holzmaden, Germany Photo: Andi Chladny Amazing Geologist

86 notes

·

View notes

Note

Your post /129246392184/fossil-crocodile-steneosaurus-bollensis-lower Hi there. Holzmaden is not Bavaria. It`s like you change Illinois with Missouri lol. Greetz from germany ;)

#1 THANK YOU for the correction, I would never have known and appreciate the geography help.

#2 damn that Heritage Auction site! I always wonder how accurate their descriptions are but give them the benefit of the doubt. Flowery language is one thing but actual data needs to be right! :P

anyway thanks and I will repost it. I like that one. Will just put “Germany” to be safe :)

2 notes

·

View notes

Link

Early Jurassic Ichthyosaurus with ammonites from Holzmaden Germany – earth66.com/…

0 notes

Photo

A BEAUTIFUL SEA LILY FOSSIL, SEIROCRINUS SUBANGULARIS, LOWER JURASSIC, HOLZMADEN, SOUTH GERMANY

Photo: sothebys.com

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

These Jurassic sea creatures spent decades crossing the ocean on rafts. Here's how

https://sciencespies.com/nature/these-jurassic-sea-creatures-spent-decades-crossing-the-ocean-on-rafts-heres-how/

These Jurassic sea creatures spent decades crossing the ocean on rafts. Here's how

The English town of Lyme Regis is part of the Jurassic Coast World Heritage Site. It was here in the 1830s that William Buckland, better known for the discovery of the first dinosaur, Megalosaurus, collected fossils with another pioneering palaeontologist, Mary Anning.

One of their discoveries was the remains of fossilised crinoids, sometimes known as “sea lilies”. Close relatives of sea urchins and starfish, these flower-like animals consist of a series of plates connected together in branches with a stem.

The specimens from Lyme Regis, dating back to the Jurassic period over 180 million years ago, look like polished brass because they have been fossilised with pyrite (fool’s gold).

Buckland noticed that these crinoid fossils were attached to small pieces of driftwood we call lenses, which had turned into coal. He hypothesised that the crinoids had been attached to the driftwood while alive, and perhaps for their entire lives, possibly living suspended underneath it.

Modern crinoids don’t typically take such journeys, but we’ve since discovered fossilised examples of groups of floating crinoids. However it wasn’t clear whether these were really thriving colonies living on the driftwood or just short-term passengers.

Now my colleagues and I have shown that such rafts could last for as long as 20 years, plenty of time for crinoids to grow to maturity and become full-time ocean sailors.

Buckland’s idea was initially seen as fantastical and the scientific world remained sceptical. Until, that is, the discovery in the 1960s of a truly spectacular group of fossils from Holzmaden, a village not far from Stuttgart, Germany.

Crinoid raft fossils have now been found. (R. Haude/University of Göttingen)

In among marine reptiles, crocodiles and ammonites, were giant colonies consisting of complete logs covered with hundreds of perfectly preserved crinoids.

The German professor Adolf Seilacher and his then student (now professor) Reimund Haude appeared to have resolved Buckland’s mystery. These floating rafts of crinoids did exist.

This idea was strengthened by evidence that, in the Jurassic period, what is now Holzmaden had been a seabed that was uninhabitable due to low oxygen levels. The crinoids would have clung for life to these logs as there was no seabed for them to live on.

However, not all scientists agreed. One of the key questions asked was whether these log rafts could have survived for long enough for the crinoids to grow to maturity. This can take up to ten years, based on modern growth rates of their living relatives that can still be found at depths of around 200 meters.

A team of scientists from the UK and Japan led by myself decided to tackle the problem. We were motivated by groundbreaking research on Japanese crinoids by Professor Tatsuo Oji, that were kept alive in the labs at the University of Tokyo.

One of the key parts of the original theory was that any floating colony of crinoids would have grown until the population became too heavy for the wood raft to support it. The log would have sunk to the oxygen-free seafloor where the crinoids would then have become fossilised.

However, research on living crinoid populations off the coast of Japan revealed that the animals would be too lightweight, even in large mature colonies, to cause a log to become overburdened and sink.

Model breakup

Our research then turned towards the wood itself. We established that the way to understand how long the colony could have lasted was to develop a “diffusion model”. This estimated how long it would take before the log would become saturated with water and fail.

The wood in crinoid raft fossils hasn’t been preserved well enough for us to know what species it comes from. So we represented it in the model with a composite estimate of trees we know existed in the Jurassic, such as conifers, cycads and ginkgo trees.

We found that the floating wood and its crinoid cargo would have been able to last for at least 15 years and maybe up to 20 years before the log would begin to sink or break up. There is evidence from museum collections of fragments of wood with entire, fully grown crinoids attached to them that could only have resulted from this kind of collapse.

Finally, we utilised a technique known as spatial point analysis developed by Dr Emily Mitchell, to plot the spaces between the fossils and work out whether the position pattern is ecological, environmental or both. This enabled us to estimate how this crinoid community might have looked on the log.

We found that the crinoids do indeed hang suspended underneath the driftwood, but clustered towards one end of it. Although difficult to observe in the original fossils, the pattern resembles that of other modern rafting species such as goose barnacles.

They tend to inhabit the area at the back of a raft where there is least resistance, which can tell us the direction of travel of the colony across the ocean.

This research has now put beyond doubt that crinoid raft colonies could exist and survive for many years to grow to maturity and travel the vast distances across the Jurassic oceans. They are a deep-time example of similar structures we see in today’s oceans.

These exciting techniques are now being used by a new team to compare living populations on the sea floor to their Jurassic forebears.

This could reveal how past changes in climate have shaped marine communities and will help scientists understand how such communities might respond to future challenges in an ever changing world.

Aaron W Hunter, Science Guide & Tutor, Dept. of Earth Sciences, University of Cambridge.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

#Nature

0 notes

Photo

Fóssil de ictiossauro. Jurassico inferior, de 185 milhões de anos atrás. From:Amazing Geologist Ichthyosaur fossil. Lower Jurassic, 185 million years ago. Holzmaden, Germany. #Fossils

0 notes