#Dungeon: Adventures for TSR Role-Playing Games

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

FEEL THE DRAGON SICKNESS OVERTAKE YOU IN THIS FEARSOME, FIERY HIGH FANTASY CLASSIC.

PIC INFO: Spotlight on one of the most popular fantasy paintings ever made, "Into the Fire," a.k.a., "THE GREAT RED DRAGON," oils on illustration board, later used as cover art to "Dungeon Adventures" magazine #1, dated September/October 1986. Artwork by the late, great Keith Parkinson (1958-2005).

MINI-OVERVIEW: "Keith’s thoughts on this piece:

"This was the cover to Dungeon magazine #1. Need I say more? I’ll take the silence as a yes. This was done during my “paint a billion objects in the foreground” period. Painting that amount of anything takes a lot of time. Would I do it again? Not in the literal sense. Since this piece was done, I’ve learned faster and more effective ways to suggest that amount of detail without actually painting every single bead. Instead, I’d focus more time and attention on the dragon, and then with all the extra time left over, I’d take a nap.""

-- KEITH PARKINSON (official site & online shop)

Sources: https://osrgrimoire.blogspot.com/2023/07/interview-with-grant-boucher.html, www.keithparkinson.com/product/the-great-red-dragon-giclee, Etsy, various, etc...

#Dungeon: Adventures#TSR Role-Playing#Dungeons & Dragons role-playing game#TSR#TSR Role-Playing Games#Tabletop Gaming#Dungeon 1986#High Fantasy#Dragon Hoard#Dragon Art#Fantasy Art#Dragon Sickness#Dungeon Magazine#Magazines#Cover Art#Oil paintings#Paintings#Keith Parkinson#Keith Parkinson Artist#Keith Parkinson Art#The Great Red Dragon#Dungeon magazine#Dungeon: Adventures for TSR Role-Playing Games#80s#Into the Fire#Dragon Treasure Hoard#1980s#Dragon#1986#Dungeon

0 notes

Text

SFWA Posthumously Presents Jennell Jaquays with the 2024 Kate Wilhelm Solstice Award

A multi-award winning and honored artist, game designer, editor, and activist, Jennell Jaquays left an indelible mark on the gaming industry and SFF community for nearly fifty years. Ms. Jaquays’ career began in college, when she and her friends created “The Dungeoneer,” one of the first licensed Dungeons and Dragons fanzines. Now, from magazines to books, Ms. Jaquays’ art can be seen on multiple covers and throughout the pages of the many different forms and iterations of Dungeons and Dragons’ media. Having designed two modules of her own, “Dark Tower” and “The Caverns of Thracia,” her writing was celebrated by players for eschewing traditional and linear game mechanics and are not only playable today–but continue to inspire game designers and GMs. Also known for her game industry work at companies such as Coleco, TSR, and id Software, Ms. Jaquays designed and contributed to multiple projects such as Coleco Vision, certain levels on the Quake II and III video games, arcade conversions of Pac-Man and Donkey-Kong, Halo Wars, and created an expansion pack in Age of Empires III. Ms. Jaquays was nominated for multiple H.G. Wells Awards for her work and creation of the “Dark Tower” D&D module and for her design and illustrations on“Griffin Mountain.” Her work with Coleco’s WarGames won her the 1984 Summer C.E.S. original software award. Additionally, Castle Greyhawk won an Origins Gamer’s Choice Award for “Best Role-Playing Adventure,” and in 2017, the Academy of Adventure Gaming Arts & Design inducted Ms. Jaquays into their hall of fame. Inspired by her own journey, Ms. Jaquays also became a recognized transgender activist, spending time working as the creative director of the Transgender Human Rights Institute. “A beacon of hope and inspiration, Jennell Jaquays worked tirelessly in the spirit of community while gifting us with her art, her games, and her stories for almost fifty years,” said SFWA Director-at-Large, Monica Valentinelli. “The Board is honored to commemorate Jennell Jaquays and her indelible legacy as an artist, writer, and game designer in the video game and tabletop roleplaying industries.” Accepting on behalf of Ms. Jaquays at the 59th Annual Nebula Awards is her wife, Rebecca Heineman.

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

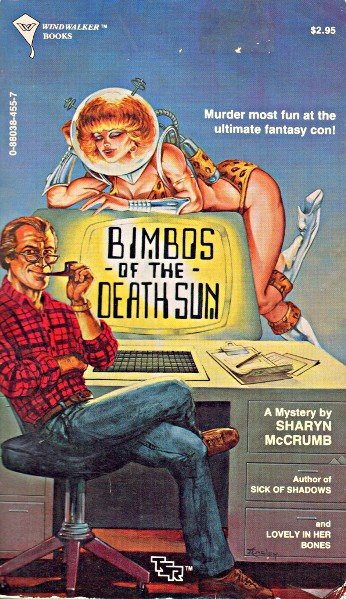

Bimbos of the Death Sun by Sharyn McCrumb

Cover art by Jeff Easley

Windwalker / TSR, February 1987

Even before the unscheduled murder of the world's most detestable cult author, Rubicon was destined to go down in fen history as the most outrageous fantasy convention ever. The great chronicler of the fantasy adventures of the noble Viking warrior, Tratyn Runewind, was suddenly no more. Appin dungannon was dead - a bullet through his hear and a spilled bottle of scotch at his side. Who hated him enough to kill him? The answer: Practically everyone.

James Owens Mega, creator of that deathless tome, Bimbos of the Death Sun, dons the roll of Dungeon Master, and solves this uproarious whodunit in the ultimate role-playing game climax.

#book cover art#cover illustration#cover art#Bimbos of the Death Sun#Sharyn McCrumb#jeff easley#convention#d&d#dungeons and dragons#tsr#dragonlance#forgotten realms#murder mystery#mystery#fantasy#rpg#role playing games#sci fi and fantasy

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Musings: Good luck finding adventure modules!

I originally come from two corners regarding roleplaying, the German The Dark Eye system as it existed in its 1e and 2e incarnations, and playing AD&D fantasy computer games. This built an expectation into me that ready-made playing material would always be available, an expectation I find increasingly thwarted in today's RPG market.

The Dark Eye - I'll use the German acronym DSA going forward to ease discussion - is one of the most well-supported RPGs in the history of the tabletop RPGs. It features hundreds of adventure modules tuned for a certain range of levels, so you can basically pick up one, read it, and run it. It's probably the most well-supported system in general, brimming with setting books, books covering meta-plot development (after it had one), etc. This is not only a good thing, though...

One time I joined a local group, playing through a pre-made adventure campaign. Not only was it impossible to leave the rails (when I tried the obstacles quickly mounted as the GM had achieved her "goal" for the scene), and people actually started to discuss, while playing, where they were in the current meta-plot right now and somebody went to the long line of books on a nearby shelf, pulled one out, and delivered some meta-plot regional info so everybody was on the same page. They basically knew the outline of the story they were playing, going through pre-made motions, having played this before, or read it. I don't know. But it definitely was one of the most bizarre experiences I ever had playing, and I left after two sessions. So, yeah, you can support a game until it stifles all initiative in players, and this has progressed well with DSA, no doubt, making it a rather extreme example.

The other experience were the games now known as Gold Box series. Built mostly on the original Advanced Dungeons & Dragons 1st edition (1e) game for its engine, the publisher brought a good amount of content for several of D&D's worlds - the Forgotten Realms, Dragonlance, and - to some extent - Dark Sun. A lot of it was combat, but even the first game, "Pool of Radiance", included an amazing system of scaling the challenge and it even changed some of its quest areas depending on when in the game you tackled them. (I'm not sure any other game at the time did that, it probably was very revolutionary in 1988.) Only the first two installments (the other one being "Curse of the Azure Bonds") saw release as TTRPG modules.

D&D is of course the other system with a history of being supported by adventure modules, lavishly so during the TSR era (up to the mid-90s). Which is funny - apparently nobody at TSR initially anticipated such a need. When people kept asking, they ended up releasing their tournament modules as write-ups. That goes a long way towards explaining why the "Tomb of Horrors" is such a meat grinder. It was meant to be one - for measuring one's mettle against other groups which ran through the same module, the end result being put into a score for comparison. In this sense, modules in D&D were off to a bad start as well, and maybe D&D altogether. Born from miniatures wargames it took quite a while until the game introduced resolution mechanics for non-combat stuff, and it is still one of most combat-heavy games around. I remember one 4e player asking me whether I found Savage Worlds too light-weight in tactical options, a game that was specifically written to shorten the endless high level combat encounters of the Deadlands Classic role-playing game while retaining the action elements. (And one I prefer - both in what to run and over 4e.)

Fast forward to today

So, growing up with such systems, I would have expected there to be an ever-expanding amount of support for games. I mean, given the grumpy mumbling of old-school grognards on their forums on kids these days and their premade adventure modules and "stories" you would think we would drown in play material ready to go.

But if I look at what's actually on my shelf, the reality is quite inverse. The recent/current systems I see that actually had significant publisher support are

D&D 5e,

Dungeon Crawl Classics (DCC),

Lamentation of the Flame Princess (LotFP),

the three Star Wars RPGs by Fantasy Flight Games,

Chaosium's Call of Cthulhu,

Pelgrane Press' GUMSHOE games (especially Trail of Cthulhu and Night's Black Agents),

Modiphiüs' Conan 2d20 and Achtung! Cthulhu,

Delta Green, and

The One Ring.

This seems a sizable list, but when I look at most games lined up behind me, I see the majority follow a different structure:

A core rulebook if it has its own system, and/or...

A setting guide, and maybe...

A companion to the core rulebook with more player options, and probably...

One or (at most) two adventure collections.

Many games in fact never make it beyond a book comprising options 1 and 2 in the same volume.

A (not so) short detour

I was reminded of this situation recently because I'm currently reading the Dragon AGE RPG by Green Ronin. As I prepare for play in a world I only somewhat remember from the first computer games, I would have appreciated some adventure modules to run or take inspiration from.

But to be fair - do I need it? One role modules play is that they give you many example encounters you can emulate. They show you how somebody with experience in the system structures a combat encounter, how many monsters is a good match, maybe it also introduces custom monsters as well. (It also shows how stories derive from the general lore of the setting.)

So I checked what the rulebook offers me in terms of advice for building encounters and monsters on my own. And this is usually where most systems that aren't D&D fall flat because you get shoddy or incomplete advice, or advice that barely works. (Looking at you, Shadow of the Demon Lord... even though you at least had some. I just don't like you, that's all.)

So, don't color me surprised that the hefty 441 page tome contains only 2 pages on encounter math, though to be fair it gives you a good guide to computing it yourself and some solid pointers. But it also comes from yet another game designer too lazy to distill their own work into a ready-to-use format. I say lazy because it would definitely require a lot of work to make something lean and mean to use. (And even 5e's system - or two systems - refined by several people, doesn't work that well, really.) But you can use it, even though presentation is prose without examples. A shoddy job, but something you can work with.

And monster design? [Insert sound of sad trombone here.] While you get almost fifty pages of adversaries and quickly usable advice how to vary them, you won't find any actual guidelines for making your own and assigning a threat level to them. Just to be sure, I also checked in the Fantasy AGE game which generalizes the system. I eventually found the needed information in the Fantasy AGE Campaign Builder's Guide, a solid 10 pages with a guided example. But to put this into context - the first Dragon AGE boxed set was published 2010, the Fantasy AGE Basic Rules in 2015, and the guide I mentioned in 2019! So, you had to wait 9 years to get this info, published in what technically is another game? What gives, Green Ronin?

So yeah, modules can help. And again Dragon AGE does neither really good or bad on that front. What they mostly don't do is publish individual modules. Here's what I found:

The Dalish Curse (originally part of Set 1, now a free download, 2010)

An Arl's Ransom (included in the Quickstart, free download, 2011)

A Bann Too Many (included in the Game Master's Kit, 2010)

Buried Pasts (included in the revised GM's Kit, 2016)

Invisible Chains (contained in the Core Rulebook, 2015)

The Autumn Falls (originally part of Set 2, now included in Core Rulebook, 2011)

Battle's Edge (originally part of Set 3, now included in Core Rulebook, 2012)

Amber Rage (in the Blood in Ferelden adventure anthology, 2010)

Where Eagles Lair (in the Blood in Ferelden adventure anthology, 2010)

A Fragile Web (in the Blood in Ferelden adventure anthology, 2010)

Duty Unto Death (an actual stand-alone module! 2013)

That's basically it. To put it into context - the game was originally split into Set 1 (levels 1-5), Set 2 (levels 6-10), and Set 3 (levels 11-20). So adventures 1, 6, and 7 were originally included in three different sets to buy. All adventures listed here are for levels 1-5 except for 6 and 7!! When the game came out, you essentially had four adventures you could run if you bought Set 1 and the anthology.

What you basically don't see is a continued support with stand-alone modules. You get them from buying the GM's Kits, the core books, and a multi-adventure anthology. I would also be fine if they ever released another anthology. But this is basically what Green Ronin does - or rather, what they don't do. (Fantasy AGE barely managed to scrape out a book per year until you finally had the basic set of books - rules, monsters, companion, campaign building.)

Reflecting our current reality

If you want to get material for pickup games, episodic stuff, isolated storylines, you are better off selecting your publisher and game to match that desire.

Some publishers only give tacit support to their product after release, while others keep pushing product. If you look for publishers who actually support (some of) their lines, you could check these out (in no particular order):

Modiphiüs (especially Achtung! Cthulhu and Star Trek Adventures)

Paizo (Pathfinder is probably the RPG with the most content to support it available to buy in print and heavily dedicated to the concept of the "adventure path")

Son of Oak Game Studio (City of Mist is probably one of the best-supported newer games!)

Chaosium (Call of Cthulhu has an endless amount of modules if you don't mind most of them being in electronic form now)

Pelgrane Press (Trail of Cthulhu has lots of modules and collection books, Night's Black Agents less but still some and especially collections/campaigns)

Goodman Games (Dungeon Crawl Classics and Mutant Crawl Classics specialize in releasing lots of modules)

Arc Dream Publishing (Delta Green has many adventure and campaign books by now)

Monte Cook Games (Numenera especially had a steady stream of material, not necessarily as modules, though)

Wizards of the Coast (D&D 5e has whole campaigns published but also a few adventure collections by now)

Pinnacle Entertainment (but only for their Deadlands series)

There's also publishers that have proven a risky bet in this regard (which is a shame given the quality of the content):

Green Ronin (slow release schedule, and of course: see above)

Pinnacle again (it's hard to predict which of their settings they will support and for how long - East Texas University (ETU) for example seems to have seen support, other series get nothing after their initial Kickstarter/crowdfunding, it's rather unpredictable - it's safest to expect nothing else to come after)

Atlas Games (Over the Edge has many modules - but only if you consider the old editions. Not much surrounding their new editions of existing games. You basically can expect that anything they release to center around their core books now and not much to come after - with Ars Magica being the positive exception)

[EDIT:] I originally listed Free League Publishing here. I was incorrect about this. Having checked their website I noticed that they issued new material for several of their games, and lots of modules of their own, even if only in PDF. They're just not pushing everything to Kickstarter nor do they mail previous backers with new releases like other publishers do. Maybe because these weren't crowdfounded. Doesn't matter. I retract Free League from this list.

I'm not trying to diss these companies, I wish they had published more stuff! It's just that their business model does not seem to include a large amount of continued support, in spite of them being surely in the middle tier of publishers. And that doesn't even include the many games that exist as core books only and their respective publishers.

A New Hope?

However, there is one more option - the companies that have opened up to third party publishing - either as content creator programs, as official licensees, or similar things. The degree to which you can use their official IP varies - sometimes you can use their rules, sometimes some or all of their settings, etc.

A good place to start is here.

The problem, of course, is that you won't know who makes quality content and who doesn't. Whether you opt to wade through the deluge of 5e third party content or the official Dungeon Masters Guild, you will probably find something to strike your fancy, but also much that is best left by the wayside.

While I have published 2 1/2 modules as a licensee for Goodman Games as well, I see this type of content as trial and error. If it's "fan made," it's often very hit-and-miss. And each third party publisher has their own merit or lack thereof.

What I definitely didn't miss was the endless amount of 3e splatbooks (especially regarding character options) - and they're back in force. What you will find in abundance are dubious custom-made classes for every taste (or again, lack thereof) with no guarantee they balance well with anything. As for adventures, the only way to know is reading samples and sinking some money into PDFs you might never use. Probably the fate of most RPG collections, though...

While publisher-made content isn't a guarantee for quality, professionals paid to write usually bring some qualities to the table that amateurs might or might not have. Your mileage may vary, but a book adhering to an established formatting and branding is not only useful, but more often than not also aesthetically pleasing. And though high-quality fan- and third-party-made content does definitely exist, the art is in finding it among the throng.

Conclusion

If you don't intend to write all your content yourself, picking a supported system might save you a lot of headache.

Even if you write your own content, you might want to consider if your system actually supports you meaningfully in doing so. Books that wax poetic for pages on end about story structure will leave you flat if they do not also contain usable advice for building encounters, adversaries, or challenges considering the system at hand. (Worst offender here: Pinnacle Entertainment. Savage Worlds is great, but they give you nothing except for a few words excusing themselves as to why they gave you nothing. For shame.)

We seem to live in an age of role-playing game abundance, but if you take a second look, you notice a lot of it are unsupported games that see a corebook release and a second volume to accompany it at best. Publishers that massively support their games are few and far between - though my list above is hardly comprehensive. I, for example, left out White Wolf/Onyx Path in spite of the lots of material because I know too little about the World of Darkness lines to comment.

It's just like with finding players. Sometimes you end up running something that isn't your favorite because it gets the job done - whether the job is finding actual people wanting to play it or if it is minimizing your prep time through available material. The scarcity of prep time is something publishers ignore at their own peril, though, and it will come back to bite some of them eventually.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

So, I like different editions of the game and they give different Vibes.

1st: The Beta Run, the old Fallout Game & Diablo style of play. It IS just Dungeons & Dragons, but if you're witty or clever enough you can break the DMs expectations and win the loot.

2nd: thac0 and the gritty art & relevancy of Every Rule Ever that you need to know all conditions that apply? Fuck yes, you're in the Dark Souls version where there is Deep Lore & some Role-playing available, but combat is deeply involved, and everything that spent time specializing has become relevant in later levels and your skill generalist is the support as intended. You need to know what you have with you at all times and you get minions that mean something to the story so you can build influence in an area and become the Dark Souls Boss. Rules Lawyer Haven.

3rd-3.5e: Did you want EPIC QUESTS?!?! We have the place for you! Steampunk? Check! Samurai? Check! Fucking wicked ass magic items that are regularly everywhere and everyone you meet has been an adventurer at one point? CHECK, MY FRIENDS! You don't need to worry about that BESM system over there, or that D20 modern system over there, just stick with us and you can live out your Human to Hero Final Fantasy Pokémon dreams right here, buddy!

Why yes that means out focus on Role-playing has diminished the coolness of survival type styles of games, but we do have lots of undead available in our rules for your Gunslinging Dark Tower Action Man to take them out on the regular. Leveling from 1 to 20? Why? You're super powerful at level 5! Minions are meaningless? Why, of course they are! They just follow you around, and I mean you can have them if you wanted, I guess, but this is YOUR STORY, so don't you want more Epic Quest?

4th ed: Hey guys, I hear Warhammer is having a revival of sorts and everybody's into painting all of a sudden, why don't you try out OUR EFFICIENT Non-Rules Lawyering,(Not stolen from the Star Wars Minis) 100% No RolePlay Encouraging, We Only have Battles on the Table Now System?

Elminster? Who the fuck is that? We don't care- I mean, here he is! Check out his minifig stats! Put him up against...*rummaging in box noises* Strahd! And his 3 delicious Vampire Babes! And check out these Eberron Steamjacks!

Did we say it was Non-Rules Lawyering?! We LIED! All of your Worst RP Friends ever (BroGrammers Galore!) will both Complain ceaselessly about this game WHILE Insisting On Only Playing This System, because while it SUCKS ASS FOR RP, it makes SENSE for Minis, that they live for. Minis & Cards.

Aka Hey man, I heard you like Warcraft & Starcraft? Well we put plastic pewter in your Warhammercraft/Starcraft.

5th Ed: Hey guys, um sorry about that mess back there. Did you guys miss role-playing? Oh, I see we're making podcasts now, that's nice, let's make a rules set for you 😉 😀 I mean, we gotta put these Rules Bits in there so the 4th ed and 2nd ed guys are willing to buy our books again, but yknow, this edition isn't about that. It's about sitting at the campfire with your friends and having fun Magic stories to um... to be nostalgic about, and come up with to make memories with um... hey are you guys hearing that? *checks bushes, 👀 Critical Role hitting a jackpot with a slot machine* huh, well as I was saying, what? *Witnesses Acquisitions Incorporated making a whole supplement book crossing the camp* "HUH. As I was saying, while we can't specialize and expect to make a prof-" *Vox Machina, Fool's Gold, Legends of Avernus, Dimension 20 & Dungeons & Daddies making specialized systems as mini games to fix bad rules, making bank*

"HEY, STOP THAT. YOU CAN'T JUST TAKE OUR NICE RULES FREE GAMES AND MAKE ACTUAL MONEY OFF THEM. WE CAN'T, SO YOU CAN'T EITHER"

rp groups who are doing well: "Hey WotC, we tried getting hired by you, and you said we didn't have the business sense to make it in the industry, and you made it be a free access license because that was the terms you bought it from TSR."

WotC: "Well, we'll see about THAT!"

Yeah, different Vibes in each edition.

Anyway OP, If you can find a set of 2nd edition, it might be more your style, but I do agree that it's weird the developers feel the need to include Bad Rules in order to make a profit, when after all, they could just remove the rules and make a minibook revolving around survival and make more money that way.

It's often remarked how D&D 5e's play culture has this sort of disinterest bordering on contempt for actually knowing the rules, often even extending to the DM themselves. I've seen a lot of different ideas for why this is, but one reason I rarely see discussed is that actually, a lot of 5e's rules are not meant to be used.

Encumbrance is a great example of this. 5e contains granular weights for all the items that you might have in your inventory, and rules for how much you can carry based on your strength score, and they've set these carry capacities high enough that you should never actually need to think about them. And that's deliberate, the designers have explicitly said that they've set carrying capacity high enough that it shouldn't come up in normal play. So for a starting DM, you see all these weights, you see all the rules for how much people can carry or drag, and you've played Fallout, you know how this works. And then if you try to actually enforce that, you find that it's insanely tedious, and it basically never actually matters, so you drop it.

Foraging is the example of this that bothers me most. There's a whole system for this! A table of foraging DCs, and math for how much food you can find, and how long you can go without food, etc. But the math is set up so that a person with no survival proficiency and a +0 to WIS, in a hostile environment, will still forage enough food to be fine, and the starvation rules are so generous that even a run of bad luck is unlikely to matter. So a DM who actually tries to use these rules will quickly find that they add nothing but bookkeeping. You're rolling a bunch of checks every day of travel for something that is purpose built not to matter. And that's before you add in all the ways to trivialize or circumvent this.

These rules don't exist to be used, that is not their purpose. These rules exist because the designers were scared of the backlash to 4e, and wanted to make sure that the game had all the rules that D&D "should" have. But they didn't actually want these mechanics. They didn't want the bookkeeping, they didn't care about that style of play, but they couldn't just say, "this game isn't about that" for fear of angering traditionalists. And unfortunately the way they handled this was by putting in rules that are bad, that actively fight anyone who wants to use that style of play and act as a trap to people who take the rules in good faith.

And this means that knowing what rules are not supposed to be used is an actual skill 5e DMs develop. Part of being a good 5e DM is being able to tell the real rules that will improve your game from the fake rules that are there to placate angry forum posters. And that's just an awful position to put DMs in (especially new DMs), but it's pretty unsurprising that it creates a certain contempt for knowing the rules as written.

You should have contempt for some of the rules as written. The designers did.

9K notes

·

View notes

Text

Advanced Dungeons & Dragons 2nd Edition by TSR

🐉 Step into the realm of epic quests and classic adventures with Advanced Dungeons & Dragons 2nd Edition by TSR! ⚔️ Relive the golden age of fantasy RPGs, filled with rich lore, legendary monsters, and unforgettable heroes. Perfect for both nostalgic veterans and new adventurers alike! #ADnD #DungeonsAndDragons #RPG #TabletopGaming #FantasyAdventure

Advanced Dungeons & Dragons 2nd Edition by TSR What is it? AD&D 2E – PHB AD&D 2E – DMG Advanced Dungeons & Dragons 2nd Edition (AD&D 2E) by TSR is a fantasy tabletop role-playing game set in a myriad of worlds, from the mystical realms of the Forgotten Realms to the dark and gothic Ravenloft. Released in 1989, this edition builds on the foundation of the original AD&D, refining and expanding its…

#ad&d 2e#ad&d 2e adventures#ad&d 2e campaigns#ad&d 2e character creation#ad&d 2e classes#ad&d 2e combat system#ad&d 2e dungeon master’s guide#ad&d 2e gameplay#ad&d 2e lore#ad&d 2e magic#ad&d 2e modules#ad&d 2e monsters#ad&d 2e player’s handbook#ad&d 2e review#ad&d 2e rules#ad&d 2e settings#ad&d 2e sourcebooks#ad&d 2e spells#ad&d 2e supplements#advanced dungeons and dragons 2e pdf#advanced dungeons and dragons 2nd edition#classic dungeons and dragons#dungeons and dragons 2nd edition#legion of myth#tsr games

0 notes

Text

Lankhmar and the Origins of Adventure Fantasy

Fritz Leiber’s Lean Times in Lankhmar is a sword and sorcery short story that is part of the Fafhrd and Gray Mouser series. The Series had a huge impact on the development of the Sword and Sorcery Genre and the term for the genre itself comes from Lieber. The story is set in the city of Lankhmar, a metropolis full of scheming factions and false gods. Fafhrd and Grey Mouser begin the story by arriving in the city of Lankhmar and split apart as their friendship has fallen apart over a disagreement of loot splitting. Both find new routes in the city with Gray Mouser entering the service of Pulg, a mob leader who gets money from the small religions of the city.Fafhrd became an acolyte for the church of Issek of the Jug. Mouser eventually has to rob the church Fafhrd works and the two reunite as opponents but eventually things resolve with Fafhrd attaining apotheosis, becoming a living god, and Pulg ends up serving Issek The two eventually leave with the money.

Lean Times in Lankhmar serves as a sword and sorcery template for novels such as Alyx by Joanna Russ and Michael Moorcock’s Elric Series. Most significantly, Leiber’s work was a major influence on Dungeons and Dragon, With TSR putting out adventure supplements set in Lankhmar and the world of Nehwon. This influence creates an image of fantasy that has bled into the mainstream perception of fantasy literature. Leiber writes in an immersive style, much of it sounding like descriptions of a D&D scenario, this is seen with the naming conventions of characters such as Gray Mouser, Muulsh the Moneylender. These names evoke images and associations that stick in the mind and immerse the reader as it makes the character sound as if they are a part of the world and have a reputation. The immersion is also seen in the allusion to another Fafhrd and Gray Mouser story in referencing the Year of the Feathered Death, giving a sense of continuity to the stories and sewing the plots into the fabric of the setting. This sense of immersion plays into a reminder of DnD as it reminds readers of the shared connected worlds and stories of the role playing game. It also adds immersion as it allows the reader to speculate on what the Year of the Feathered Death was if they’ve never read that tale similar to the allusion to the Clone Wars in the original Star Wars where there was nothing but the allusion until the Prequel Trilogy fleshed out the Clone Wars. Leiber’s approach to immersion is akin to throwing you into the world and letting the reader figure it out rather than using exposition to accomplish this. Depending on the reader, the show not tell approach can be an effective tool for immersing the reader but for other readers this can pull them out of the narrative. Leiber’s characters also set up archetypes that are seen within Dungeons and Dragons, Fafhrd being the large northern warrior who is honorable and brave, Gray Mouser is the sly rogue who uses wits and deception to achieve success, both of these are common character types in fantasy and within Dungeons and Dragons. The competing priests and faction also plays into this as characters like Pulg can easily be seen as quest givers. These character tropes have even bled into the characterization of characters within Dungeons and Dragons lore and novels such as the Dragonlance Chronicles series, with Fafhrd being very similar to Solamnian Knight Sturm Brightblade. Leiber’s work here can be seen as cliche but only in that it is an origin point for the development of these fantasy conventions and tropes. Leiber’s originality might be overrated now but it lays the groundwork for much of the fantasy genre and Lean Times in Lankhmar contributes much to what we owe to Leiber.

0 notes

Text

A brand-new way to create a story

[by David M. Ewalt]

Original D&D: Blackmoor (the 1975 TSR edition and the 2013 WotC reprint)

In December 1970, after a two-day binge of watching monster movies and reading Robert E. Howard’s Conan the Barbarian books, Dave Arneson invited his friends over under the pretense of playing a traditional Napoleonic war game. Instead, he introduced them to the city of Blackmoor.

“They came down to the basement and there was a medieval castle in the middle of the table,” says David Megarry. The players, Arneson explained, had been sent through time and space to a medieval city and had to control original heroic characters, each with their own attributes, powers, and goals.

“My very first character was a thief,” says Megarry, “and my nemesis was Dan Nicholson, the merchant. His role was to try to get stuff into town and then sell it. And my role was to try to steal his stuff and make my money that way. It gave us a framework of how to operate in this world.”

Characters in place, Arneson sent the players to explore the dungeons beneath the castle and town. Inside, he hit them with another twist: The subterranean passages weren’t defended by human soldiers but inhabited by fantastic monsters—like a dragon, which Arneson represented on the table using a plastic toy brontosaurus with a fanged clay head. The fantasy role-playing game was born.

Much of the appeal of the game came from the excitement of exploring the winding corridors underneath Blackmoor. “There was that thrill of discovery,” says Megarry. “You have to make a decision... left or right, or staircase in front of you going down?”

At first, combat in the world of Blackmoor was resolved using a clunky system of rock-paper-scissors showdowns. But Arneson quickly turned to the rules of a medieval-miniatures war game called Chainmail, paying particular interest to two sections of its sixty-two-page booklet: “Man-to-Man,” which explained how to manage individual heroes amongst your army, and “Fantasy Supplement,” which included rules for casting magical spells and fighting hideous monsters.

Chainmail’s “Man-To-Man” and “Fantasy Supplement” sections were not intended for roleplaying, they were still war game variants; thankfully, they were appropriated by roleplayers, and 50 years later, here we are.

Chainmail provided a framework that helped Blackmoor develop from a novelty into a consistent, ongoing game. But ultimately the system proved too limited for Arneson’s growing fantasy world. He began adding his own innovations—rules for fighting in different types of armor, lists of magical artifacts, and provisions for improving a character over time.

Like any passionate hobbyist, Arneson was excited to share his work with others. So he decided to show off Blackmoor to Chainmail’s author. [...]

Greyhawk: Original D&D (TSR, 1975) and Advanced D&D (TSR, 1983)

Arneson visited Lake Geneva in the fall of 1972 to show off his Blackmoor game, but what he really delivered was innovations: Every player at the table controls just one character. Those characters seek adventure in a fantasy landscape. By doing so, they gain experience and become more powerful.

Gary Gygax took those ideas and turned them into a commodity. “I asked Dave to please send me his rules additions, for I thought a whole new system should be developed,” he wrote. “A few weeks after his visit I received 18 or so handwritten pages of rules and notes pertaining to his campaign, and I immediately began work on a brand new manuscript.”

Over the next two months, Gygax labored at a portable Royal typewriter crafting the rules for a new kind of game, where players roll dice to create a hero, fight monsters, and find treasure. By the end of 1972, he’d finished a fifty-page first draft. He called it the Fantasy Game.

The first people to play it were Gygax’s eleven-year-old son, Ernie, and nine-year-old daughter, Elise. Gygax had created a counterpart to Arneson’s Blackmoor, which he called Castle Greyhawk, and designed a single level of its dungeons; one night after dinner, he invited the kids to roll up characters and start exploring. Ernie created a wizard and named him Tenser—an anagram for his full name, Ernest. Elise played a cleric called Ahlissa. They wrote down the details of their characters on index cards and entered the dungeon. In the very first room, they discovered and defeated a nest of scorpions; in the second, they fought a gang of kobolds—short subterranean lizard-men. They also found their first treasure, a chest full of copper coins, but it was too heavy to carry. The two adventurers pressed on until nine o’clock, when the Dungeon Master put them to bed. Fatherly duties completed, Gygax returned to his office and designed another level of the dungeons.

The next day the play tests continued, and Ernie and Elise were joined by three players plucked from Gygax’s regular war-gaming group: his childhood friend Don Kaye (Murlynd) and local teenagers Rob Kuntz (Robilar) and his brother Terry (Terik). He also sent the manuscript to a few dozen war-gaming friends around the country, requesting feedback. “The reaction . . . was instant enthusiasm,” wrote Gygax. “They demanded publication of the rules as soon as possible.”

The local gamers also clamored for more. As they got farther into the depths of Castle Greyhawk, they faced greater challenges and began to feel like they were a part of a legend: Thanks to Dave Arneson’s innovation of persistent characters, the dungeons had a living history. If Tenser killed a pack of kobolds on Tuesday, Robilar might find the corpses on Thursday. It was a brand-new way to create a story.”

— David M. Ewalt, Of Dice and Men: The Story of Dungeons & Dragons and the People Who Play It (Scribner, 2013); abridged excerpts

#David M. Ewalt#d&d history#od&d#chainmail#dave arneson#gary gygax#Of Dice and Men: The Story of Dungeons & Dragons and the People Who Play It

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

D&D: Magic of The Game

Anyone who is familiar with the title will already know what I will be talking about this Odin’s Wednesday. We’ll be talking about some Dungeons and Dragons (D&D)!

As a Chameleon of a number of communities. The world of D&D has been a subject that I hear a lot but am terribly new to. I see it referenced in various mediums and mentioned among friends who are board game enthusiasts but I never bothered to sink into. That was until I stumbled across this video from Fandom Entertainment about;

[Defeating Your Demons with D&D].

After that, I watched a few more videos related to D&D and, I got the general basics of the game itself, its history with religious communities and the people who played them but I don’t completely understand it. As in, I didn’t understand its appeal. How can a game about people role playing with a piece of paper, some dices and a simple figurine be so interesting? Why do you want to be an other worldly being? It felt strange to me.

All that being said, the idea felt oddly familiar. Like sore thumb, it stuck out to me as an odd thing but at the same time, it strangely fits in with the subjects I am quite versed in. Granted, I am, STILL new. I don’t know much about this stuff but, the internet IS helpful so...

[This is just for transition, Credits to JoCat]

- Welcome to a Crap Post to D&D -

Dungeons and Dragons is a tabletop role playing game that was founded by Gary Gygax and Dave Arneson in 1974, published by Tactical Studies Rules, Inc. (TSR). It’s a board game hybrid that uses in-world based character sheets, action dices, imaginative immersion, a game master or, Dungeon Master and talking. Lots and lots of talking.

The DM’s duty in the game is to world-build, create scenarios, determine player outcomes, keep/ make/ break the rules and most importantly. Keep track and keep score of everything. Basically, the DM is the appointed nanny for Board Game Night. Meanwhile, the player’s role is to create a character, decide their course of action in said scenario and...just have fun.

If you look it up, you’ll notice that lots of celebrities have openly talked about and publicly played D&D. To name a few, there is Joe Manganiello, Matthew Mercer, Stephen Colbert, Chris Hardwick, Ashley Johnson, Terry Crews, Wil Wheaton and many more. Its a game that looks intimidating, sounds very complicated but generally easy to start.

As of today in 2021. D&D is making a comeback. From what I was told, the group; [Critical Role] is the biggest one currently leading the charge with live streaming sessions of D&D for about four to five hours. Granted, there are other streamers and creators who are also live streaming D&D or making content of D&D like the group; [Acquisitions Inc], the animators [Mr Ripper]��and [Blaine Simple] and the wiggly crap guide, [JoCat]

- The Best of Both Worlds -

So, back to my question. Why do people like to imagine themselves as someone or rather, something else? Say, Person A - is from Texas, hates germs, smarter than everyone in his school but prefers to stay at home to read comic books and play video games.

(Wait...I just described Sheldon!)

Why would Person A want to be a, Level 30 Lizardman Mage with spells for days to kick ass, take names and be awesome? - By the way, I just made that up. I don’t really remember Sheldon’s actual D&D character.

Well, why wouldn’t you? Part of the charm in D&D is the ability to immerse yourself into a role YOU made to exist and function. Essentially, D&D provides some established set pieces and various species of beings to mix, match and play with. The world of D&D may have its own set of rules and regulations but the character is your creation.

Using the established “Race” and choosing a “Class” the player gets to decide the character’s personality, their history, the quirks and the in-world interactions they have with the other characters and the world itself. The player gets to go on epic adventures and make memories with their friends, all while sitting together in a room with their notes and their minds, wandering off to D&D Land.

With D&D, there is no desire to conclude the game or reach the end of the game but rather, there is the desire to keep going and uncover more about the world itself. While your decisions and conclusions are dictated by the roll of your dice and the various game mechanics (which I know very little about). The Player’s engagement to the game is what makes the world, the story, the character itself and the quests feel so real.

Back to Sheldon, I remember watching this one episode of The Big Bang Theory when the character, Bernadette was pregnant. She couldn’t eat and drink certain things, she felt like she was something fragile because she’s having a baby and she was upset. To cheer her up, Sheldon created a solo campaign of D&D that turned Bernadette into...well, [See for yourself]

For a moment in the scene, Bernadette became invested in the story. She happily engaged and jumped with excitement when she could do certain things as her character. While still her pregnant-self. Her character could, drink alcohol, eat sushi, watch her husband (Howard) suffer while being pregnant, be tall and other wishful thoughts.

Perhaps that is the other appeal of the game. This idea of living in two very different worlds is what makes the game fun. Your in-game character, the decisions you make, the story you partake in and the actions you do. They don’t affect the real world and yet, in some way. It lifts your spirit and gives freedom. In a strange twist, it did something...magical. According to some D&D enthusiast, the game also builds positive characteristics. Such as leadership, empathy, respect, understanding while also being your inner hero.

There is NO WRONG way to play D&D, there is only, A WAY to play D&D and regardless of the outcome, there is always the next turn. In fact, some say that D&D is a game that allows you to make mistakes but the mistake could also be a blessing in the long run. This game allows you to leap out of your limited human body and become the very character you wanted to be. Its the best of both worlds. You get to be yourself and you also get to be that desired someone at the same time.

To quote Judy Hopps: “Anyone can be Anything.”

- Heroes, Let’s Play! -

Like most things in pop culture, It has a fair share of good days and bad days when dealing with the general public. As a board game of make-believe with monsters, magical creatures and...demons. It sure has raised some eyebrows of the religious kind. But that was donkey’s years ago!

In today’s age, D&D has become a positive tool to help children, teens and adults to hang around and play with their friends and their imagination. Earlier, I mentioned Critical Role and the names of other D&D content creators that has made D&D accessible and simple to get into. What used to be a nerdy or geeky game has now been brought back from the dead with big and popular names in media as well as individuals from various identities joining hands to widen its spectrum. While it once was a Western phenomenon, is slowly building up to other parts of the world as we speak. My country included!

Remember how I said D&D felt odd and yet familiar? If you look at other shows/movies, board games and role playing video games. They, in some way fit in with that spectrum. The Anime, [Konosuba] is basically D&D but with some very unreliable and horribly incompetent players in a sitcom-like fashion. The teen drama, [Riverdale] featured an in-show D&D knockoff called, Gryphons and Gargoyles. With darker additions of drugs, gangs, killers and other angsty stuff! The movie, [The Guardians of The Galaxy] is just D&D IN SPACE!

Speaking of Space, there are also other types of board games that used the D&D mechanics with a bit of a theme change. Like say, Warhammer 40,000 - a Sci-Fi twist version of D&D, Mice & Mystics - is an easy to understand and easy to play game about fighting pests, Cyberpunk 2020 - is a dystopian cyber world, floating cars and all that.

Its a simple concept that, despite it once being banned has now gotten popular again as something good but still, why? Here’s the thing, if you take away the magic of D&D, the sets, the mini figures and strip it down to its core. D&D is basically a game of escape. To awaken your inner hero, anti-hero, edge lord, borderline villain and so much more to be a different YOU without any worries and any judgement.

D&D has helped people in its own special way. It allows people a chance to be unique and it feels, cathartic. For some of us, we are bound to something and that something hold us back. D&D breaks that, it may still be a fantasy game that exists in only our heads but its a game that transcends past itself and beyond. A world that is constantly developing and makes hanging out with people to be a little bit more...interesting and its right there. Waiting...

With all that in mind, the table is set and now...its [YOUR Turn to Roll!]

And with that, comes the end of another post. I...hope I did this topic justice and I hope that you enjoy it. Also just a final note, with the world still being on FIRE right now, you might be interested in trying D&D. If you don’t have the game, don’t worry. Its available to play online. Keep in mind, you DO have to register for an account.

[Link here] and [Link here].

Also, my posts have been quite hit and miss lately. (as it always does B, who are you even trying to impress?!) So I’m thinking, every Odin’s Wednesday might have to cut based on the response but hey, I won’t force you to like it or re-blog it or do anything. This is still just a hobby. Anyways, till the next post...

Thanks for reading

- B -

#dungeons and dragons#dungeon master#original character#critical role#board game#matthew mercer#marisha ray#joe manganiello#ashely johnson#laura bailey#big bang theory#sheldon#sheldon cooper#bernadette#bernadette rostenkowski#zootopia#judy hopps#tabletop#tabletop games#the guardians of the galaxy#groot#konosuba#d20#your turn to roll#jocat#crap guide

61 notes

·

View notes

Photo

220 Further adventures in the Realms of Dungeons and Dragons. An owlbear (also owl bear) is a fictional creature originally created for the Dungeons & Dragons fantasy role-playing game. An owlbear is depicted as a cross between a bear and an owl, which "hugs" like a bear and attacks with its beak. Inspired by a plastic toy made in Hong Kong, Gary Gygax created the owlbear and introduced the creature to the game in the 1975 Greyhawk supplement; the creature has since appeared in every subsequent edition of the game. Owlbears, or similar beasts, also appear in several other fantasy role-playing games, video games and other media. #dungeonsanddragons #wizardofthecoast #TSR #art #artwork #artistofinstagram #artist #artistforhire #Custom #create #drawing #drawingaday #draweveryday #illustration #pencil #sketch #ink #colordrawing #fabercastell #copic #Happs https://www.instagram.com/p/CSTeVZkLuww/?utm_medium=tumblr

#dungeonsanddragons#wizardofthecoast#tsr#art#artwork#artistofinstagram#artist#artistforhire#custom#create#drawing#drawingaday#draweveryday#illustration#pencil#sketch#ink#colordrawing#fabercastell#copic#happs

1 note

·

View note

Text

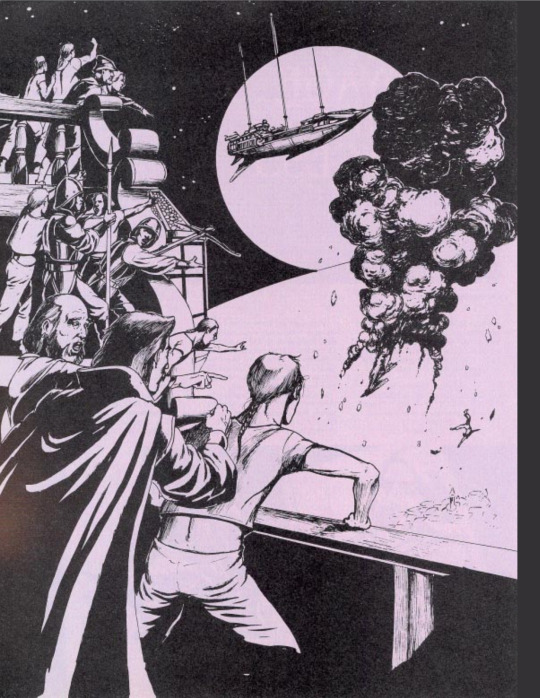

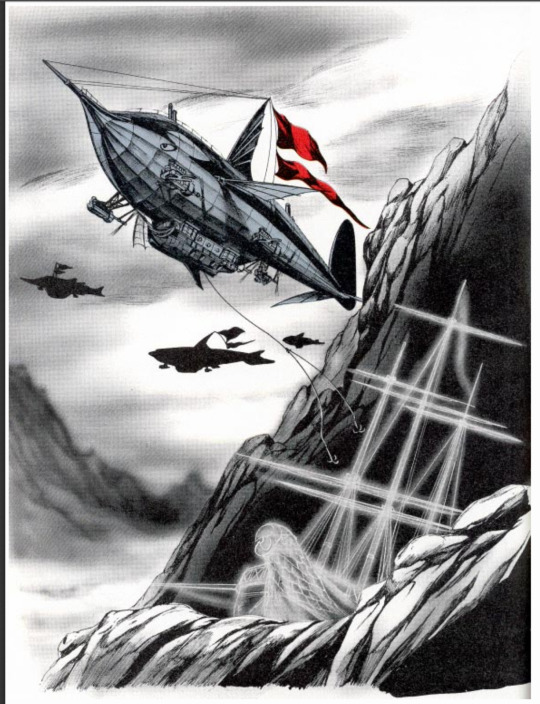

Books of Magic: The Voyage of the “Princess Ark”

(Images by Jim Holloway and Thomas Baxa come from PDF scans of Dragon Magazine, are © Wizards of the Coast or their respective copyright holders, and are used for review purposes.)

Previous installments in my “Books of Magic” series were, weirdly enough, about books.

This time, I want to tell you about a series: Bruce A. Heard’s “The Voyage of the Princess Ark,” which turns 30 years old this very month.

TVotPA ran in the pages of TSR’s Dragon Magazine nearly every month from January 1990 (Dragon #153) through December 1992 (Dragon #188). A serialized travelogue and adventure story told in 35 installments over three years, TVotPA was part Master and Commander, part Star Trek, and part The Adventures of Asterix (the last two of which Heard explicitly cited as inspiration in his letters columns). It follows the saga of Prince Haldemar of Haaken, an Alphatian wizard who recommissions an old skyskip and sets out to explore the lesser known regions of the Dungeons & Dragons game’s Known World, which would soon come to be known as Mystara.

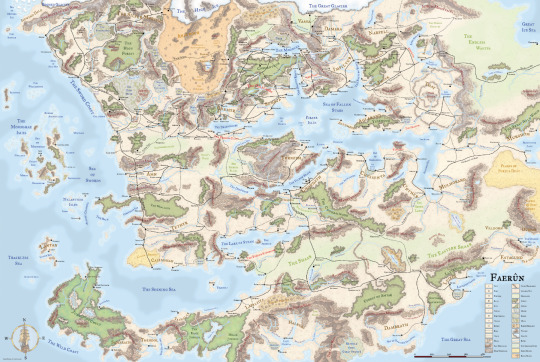

Some background might be necessary for those of you who aren’t familiar with the chaos that was D&D at the time. In the 1980s and 1990s, Dungeons & Dragons and Advanced Dungeons & Dragons were two different games. I’m simplifying the chronology here, but basically in the late ’70s D&D was meant to serve as a simplified gateway to introduce fans to fantasy role-playing before guiding them on to AD&D. But in the 1980s, thanks to the release of the Moldvay/Cook Basic and Expert Sets, and then the five Mentzer box sets (the ones with Larry Elmore dragons on the cover, now referred to as BECMI D&D—for the Basic, Expert, Companion, Master, and Immortals Rules box sets), D&D had become a viable game in its own right, with its own world, referred to only as the Known World.

The Known World—particularly as it was showcased in the Expert Rules—was a mess: more than a dozen nations slammed together in the corner of a continent to illustrate for young DMs the various forms of government you might find in D&D beyond kings and queens. Along the way, these nations also served as analogues for real-world societies ranging from Western European countries to Native American nations to the Mongolian khanate. But it was a glorious mess, thanks to a series of excellent Gazetteer supplements that had rounded out and mapped these nations in great detail, capped off by a box set, Dawn of the Emperors, that described the Known World’s pseudo-Rome, Thyatis, and its rival empire Alphatia, a nation of wizards across the sea.

By the end of 1989, then, D&D was at a crossroads. It was clearly the unloved child, seen as “basic,” best for beginners. Its setting did not have the novel support of Dragonlance or the energy of the surging and more thoughtfully conceived Forgotten Realms, then only two years old. The Gazetteer series had covered nearly all the known nations (two more would come later thanks to popular demand). And even Dragon Magazine rarely carried D&D material—a fact that was excruciating to me when I started picking up issues in late 1988 as a 5th grader.

Into this void stepped Bruce Heard. He’d been the architect of the Gazetteer series, had written some of its best installments, and was the overmind behind the D&D line at the time. If I’m remembering my history correctly, he approached the editor of Dragon, the amazing Roger Moore, about supplying a column that would provide regular D&D content for that starved segment of Dragon’s audience. In his editorials and answers to reader letters, Moore had made several mentions of needing more D&D content for the magazine, so he was a receptive audience. Heard got the green light, and “The Voyage of the Princess Ark” was born.

I still remember where I was when I realized this was happening. I missed the series launch—with my tiny allowance, I could only justify buying Dragon issues that really interested me, and Dragon #153 hadn’t leapt of the shelf at me. (Not having the Masters Rules box at the time, I didn’t realize the illustration of a continental map plastered with “WRONG WRONG WRONG” was referring to the D&D world.) I did have Dragon #155 (still one of my favorite issues of all time), but somehow I skipped past TVotPA Part 3—I wasn’t reading issues cover to cover yet and somehow didn’t grasp what was going on.

Then came issue #158. I was away for a week at Boy Scout summer camp, and I’d brought the June issue of Dragon with me. Having torn through the articles about dragons (June’s theme was always dragons), I turned to an article illustrated with a wizard and an ogre/elf cross riding pelicans. Better yet, they article had stats for playing these ogre-elves as PCs.

D&D stats.

THIS WAS A D&D ARTICLE!

And it was part of a SERIES!!!

With some effort, I tracked down the issues I’d missed—no easy task for a just-finished-6th-grader—and soon was buying Dragon every month. Moore and Heard’s plan had worked. I was hooked on both TVotPA and Dragon from then on. (The next time I missed an issue, I’d be a college freshman and the industry was on the verge of collapse.)

Most installments of TVotPA followed a simple template: The Princess Ark would fly to some new spot on the map, the crew would get into some trouble (usually brought down on them by the actions of Captain Haldemar himself), and then more or less get out again, either due to a last-minute save by Haldemar or some surprising turn of events. All this played out in the form of log entries—originally by Haldemar, then supplemented by other crewmembers as the cast expanded—that allowed Heard to deliver both in-world descriptions and rollicking action at the same time. The article would then offer back matter containing rules content or setting write-ups, and sometimes conclude with a letters column of readers reacting to the setting or seeking clarification on some arcane point of D&D rules and lore.

While this template was simple, it was never boring. The episodic nature of the series let Heard play in a variety of tones and genres: lost-world pulp, courtly drama, horror, farce, even a Western—heck, he slipped in an homage to the Dark Crystal (which at the time I didn’t get, not having seen it) as early as Part 5 (Dragon #157). As well (without getting into too spoilery territory), various overarching antagonists and plot threads—including a threatening order of knights, a devious dragon, two major status quo changes, and divine machinations—kept things simmering in the background from episode to episode. The characters likewise became more developed as Heard’s writing grew in confidence and ambition, and reader affection grew for side characters like Talasar, Xerdon, Myojo, and the rest. Once the series was up and running at full speed, it was a sure bet that if you didn’t like that month’s story, you’d dig the rules write-up, or vice versa. And when the story, setting, characters, and rules all came together, such as in Dragon #177, an episode would just sing.

Once again, I can’t tell you how thrilling this series was to 6th–9th-grade me. First of all, it came along at the perfect time. Heard’s writing literally matured just as my reading did, so the series and I literally grew up together. 6th grade was also the year I discovered comics, so this was also the era of my life when I was falling in love with serialized storytelling. Similarly, it was my first time really embracing the epistolary form.

Perhaps most significantly for this blog and my freelance career, the column was also an early primer for me on game design. Watching Heard tweak D&D’s simple rules to evoke a more complex world, especially when looked at in concert with D&D’s Gazetteer and Hollow Word supplements, gave me the courage to think about tweaking/inventing lore and systems myself. Heard also made a habit of pilfering monsters from the Creature Catalogue, seeing potential in them no one else had, and then suggesting entire cultures for them. (If that doesn’t sound like someone you know…what blog have you been reading?) He made creating a world seem easy, because he did it month after month after month.

Finally, TVotPA was thrilling because it was clear proof that someone took “basic” BECMI/Rules Cyclopedia-era D&D seriously. And that meant someone took us, the fanbase, seriously too. Back then, I couldn’t afford AD&D. Even if I could, I didn’t want to mess with all the complexity. Plus, I loved the Known World. I loved the Gazetteer books and the Aaron Allston box sets. By writing and publishing TVotPA, Bruce Heard and Roger Moore made me feel like they cared about and for fans like me. I didn’t have Raistlin, I didn’t have Elminster…but I didn’t need them, because I had Prince Haldemar of Haaken and his magical Princess Ark.

In fact, it’s no exaggeration to say that falling under the spell of Dragon and TVotPA were some of the most magical and mind expanding moments of my middle school years.

But what does this mean for you, the current Pathfinder or D&D fan? Should you read “The Voyage of the Princess Ark”?

Obviously I’m going to say yes, for all the reasons I’ve listed above. If you like maritime adventures, steampunk, or pulp adventures, this is obviously the series for you. If you like Pathfinder/D&D where a wizard is as likely to throw a punch as he is to go for his wand, this is the series for you. If you like on-the-fly worldbuilding, this is the series for you. If you like setting, story, and rules expansion all mixed together every month, this is the series for you.

TVotPA has never been collected in its entirely (more on that later), but there are PDF scans of all that era’s Dragon issues online. Start at Dragon #153 and keep reading. I’ll warn you that the first installments are a little slow, but I’d be surprised if you aren’t pulled in by the end of Part 8 (Dragon #161). If you’re the sort of reader who wants to sample a series running on all four cylinders before committing, I recommend Part 18 (Dragon #171), set in the pseudo-Balkan nation of Slagovich, or Part 24 (Dragon #177), when the crew encounters the Celtic-influenced druidic knights of Robrenn, as great places to get a strong first impression.

To my eye, “The Voyage of the Princess Ark” consists of four major arcs, plus a smattering of follow-up material that owes a debt to the series. If you do decide to dive in, here’s a quick reading guide:

Arc 1 / Parts 1–10 / Dragon #153–163 / This arc launches the series and introduces us to several major antagonists. The first few installments are slow going, but by Part 6 (Dragon #158) or 7 (Dragon #160) we see signs of the series as it will be in its prime.

(Dragon #158 also looks at D&D’s immortal dragon rulers; some of this info will later get superseded by a more canonical article in Dragon #170 a year later. Don’t sleep on Dragon #159—though it doesn’t have an installment of TVotPA, there is some fun Spelljammer content in that issue. Speaking of Spelljammer, Dragon #160 also has a companion article entitled “Up, Away & Beyond,” that serves up rudimentary rules for space travel in D&D in tandem with the action in that month’s TVotPA.)

As you have probably just gleaned, this arc also takes the Princess Ark briefly into space and introduces D&D’s second, secret setting, the Hollow World, which was being launched at that time .

Arc 2 / Parts 11–15 / Dragon #164–168 / This short arc deals with the ramifications of a major status quo-altering event at the end of the previous arc. As the crew comes to terms with their new circumstances, Haldemar learns more about the ship itself and the magics behind her. The arc ends with yet another status quo shakeup and detailed maps of the Princess Ark.

Arc 3 / Parts 16–28 / Dragon #169–181 / Hex maps! One of the calling cards of the D&D Gazetteer series was its gloriously detailed full-color hex maps, so it was kind of a disappointment when TVotPA served up only rough sketches of coastlines and mountain ranges. Part 16 gave us what we’d wanted all along: glorious hex maps (detailing the India-inspired nation of Sind no less!). They weren’t always perfect—several issues in the #170s had the wrong colors for mountain ranges, or even seemed crudely painted with watercolors—but by Part 24 (Dragon #177) we got the crisp, expertly designed nations we expected in our Known World.

Early in this arc, we also get a passing of the torch between artists. Parts 1–17 were illustrated by Jim Holloway, who I like for his action scenes, his expressive faces, and the classic stern captain’s look (complete with mustache) he gives Haldemar. (Holloway also does the best dwarves, gnomes, and halflings in the fantasy business.) Starting with Part 18 (Dragon #171), we are treated to the more angular, stylized look of Thomas Baxa, with Haldemar losing his mustache and gaining a silver-streaked ponytail. Terry Dykstra takes over in Part 25 (Dragon #178); his style is more cartoony (his Myojo really suffers from this), but he keeps Baxa’s character designs till the end of the series.

Now that I’ve totally buried the lede, let’s unearth it: This arc is, for my money, the series at its absolute prime. Action-packed stories. More characters in the spotlight. Meaty setting descriptions and rules content. New PC races and classes. Even heraldry for each nation! Heard also continued his habit of dredging up D&D creatures from the Creature Catalogue and loosely tying them to real-world cultures for great effect. I suspect many of you will love the French dogfolk of Renardy or the English catfolk of Bellayne, not to mention the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles reference he sneaks in there.

(By the way, it should be noted that today in 2020 we’re more hesitant to do such A+B design. But remember, 1) 1990–1992 was a different time—by ’90s standards, Heard is engaged in pretty solid, multiculturalist worldbuilding, and 2) Heard grew up in Europe (France originally, I believe), so while some of the characterizations and comedy is broad, the settings are grounded in both on-the-ground familiarity and good research, and the humor is affectionate and of a piece with works like Asterix that any European reader would be familiar with. In other words, don’t stress it and just enjoy that the dog-dudes are shouting “Sacrebleu!” The one exception might be the depiction of Hule, an evil D&D nation that has always been hung with vaguely Persian or Arabian trappings…but again 1) Heard was working within the established canon, and 2) the Known World setting more than balances that out with the Emirates of Ylaruam, an Arabian/Persian-inspired nation that was depicted with lots of sensitivity and care by Ken Rolston and others, to be followed by the amazing Al-Qadim setting for AD&D. So I don’t think there’s much in here that should raise alarms from a cultural sensitivity perspective, but if something does strike you discordantly, remember we’re talking about works that are 30 years old and make allowances as you feel you can.)

Along the way, you’ll also get a sneak peek at what would become AD&D’s Red Steel setting and the Savage Baronies box set—including some of the first Spanish and Moorish-inspired nations you’ll find in fantasy RPGs of this era—learn a bit about the Known World’s afterlife and undead, and even get an honest-to-Ixion cowboy shootout, as well as lots of PC options and deck plans for the evil knights’ flying warbirds, which put the Klingons’ warbirds to shame. (Oh, and while you’re reading, don’t skip the two articles about the Known World’s dragons in #170 and #171!)

Arc 4 / Parts 29–35 / Dragon #182–188 / Dragon #158–181 is among the best two-year-runs Dragon Magazine ever had, and TVotPA is a large part of the reason. But a lackluster issue #182 was a first quiet sign of a long slow downturn to come. The fact that that issue’s TVotPA entry was only a letter column portended even more dire things. In fact, three of the seven installments in this arc were purely letters columns, which was a huge disappointment at the time: We’d waited a whole month and got…just letters?!?

By this point, I think we knew the Wrath of the Immortals box set was coming—one of those world-shattering setting updates that was being pitched as a relaunch of the setting, but which could also serve as its climax. My hope at the time was that Wrath of the Immortals would kick things into a new, higher gear for both the Known World (which by then we knew as Mystara) and TVotPA, especially since the D&D Rules Cyclopedia had only come out the year before. But alas, it wasn’t to be.

Thanks to the three letters-only entries, the writing was on the wall. In Part 35 (Dragon #188), TVotPA wound its way to a close that felt appropriate but not properly climactic. God, what I wouldn’t have given to have traded those three letters columns for one last showdown with a certain dragon, those dastardly knights, or any other more suspenseful end! The end we got was nice and tidy enough (and took us to fantasy Louisiana, Australia, and Endor), but it wasn’t the end we wanted…in part because we didn’t want it to end, ever.

Arc 5 / Coda & Part 36 / Select issues of Dragon #189–200, Champions of Mystara, Dragon #237, #247 & #344 / In 1993, TVotPA was replaced with “The Known World Grimoire.” This was a grab bag of announcements, letters columns, nitty-gritty details on running dominions (Companion and Master-level D&D players got to have their own lands, castles, and even kingdoms if they so wished), and other sundries. Most of these are skippable. Four exceptions are four “Grimoire” entries which could practically be TVotPA installments: Dragon #192, which covers the manscorpions of Nimmur, Dragon #196, featuring the orcs of the Dark Jungle, an article on D&D heraldry in Dragon #199 (which is an edge case, but I’m including it here because the rules could be applied to the coats of arms of the various Savage Coast nations), and Dragon #200, which looked at the winged elves and winged minotaurs of the Arm of the Immortals. Coming out as it did in the giant-sized issue #200, this last article felt like what it was—a last goodbye to D&D’s Known World/Mystara as we knew it before Mystara’s relaunch as an AD&D line.

(Dragon #200 also had a nice article on making magic-users in D&D more distinctive. There was also “The Ecology of the Actaeon” in Dragon #190, one of the only D&D ecologies to be published in Dragon’s 2e AD&D era. Somewhere in this time we also got the news that the Known World would be relaunched as AD&D’s Mystara setting, whose products were famous for coming with audio CDs and not much else.)

Around this time TSR also published its TVotPA-inspired—and utterly maddening—Champions of Mystara box set. I say “maddening” because, at least to me, it clearly felt like a “Sure, here fine, have your dang box set” product, a too-pricey production made because fans demanded it, but not out of real love from anyone at TSR but Bruce Heard himself and co-designer Ann Dupuis.

(Let me be clear: This is all speculation; I can’t confirm any of that; I’m just saying what it felt like.)

Among the reasons for my disappointment: There was no new content featuring Haldemar and his crew. One of the booklets reprinted most of TVotPA…but not the first 10 or so entries (so it wasn’t even the complete epic! *headdesk*) and none of the ancillary material, just the story logs. Another booklet was deep in the weeds of skyship construction—hell yeah, you could build your own skyship!—but gave little content to, say, inspire lots of fun skyship-to-skyship adventures in the vein of Spelljammer, such as tons of skyships from other nations. The box did contain eight standalone cards with other ship designs, but most of these were one-off constructions by solitary wizards and rajahs, not enough to really launch a campaign. My favorite booklet was the “Explorer’s Manual,” which gave us some new setting details we hadn’t seen before, including an amazing subterranean nation of elves and gnolls that I still think about to this day…but again, it was all too little, too late—for this fan, at least.

In other words, don’t try to buy the Champions of Mystara box set—at time of writing it’s crazy expensive and not worth it for anyone not actively playing BECMI D&D right this minute. If, after reading the entire series, you’ve fallen in love with TVotPA (which admittedly was my goal in writing this) and absolutely must have Champions for that nation of elves and gnolls, get the PDF on DriveThruRPG.com.

Years later, as Dragon was limping through the late ’90s before its rejuvenation in 2000, Heard provided 2e AD&D rules for Mystara’s lupins and rakastas in Dragon #237 and #247, including writing up tons of subraces inspired by actual pet breeds. If you’ve ever wanted to play an anthropomorphic St. Bernard or Siamese, these are the articles for you.

Finally in 2006, when Paizo had taken over publishing Dragon, they invited Heard to deliver one last TVotPA entry in Dragon #344…giving us, if not a climax, definitely one last burst of palace intrigue and action to bridge the gap between the series proper and the events of Wrath of the Immortals. Over and above all the other coda material I’ve mentioned, this actually fits in the saga—it’s even labeled Part 36. If you want to ship out one last time with Haldemar and his crew, track it down.

Finally x2, there is the world of Calidar. After being thwarted for several years trying to get permission to write new TVotPA content, Bruce Heard has created his own game world filled with skyships and adventures. I own the books (which are rules-light so fans of any system can use them), but haven’t had time to read them yet; hopefully you will be a more determined fan. Keep an eye out for his various Kickstarters and definitely show your support.

Finally x3, if you think I am the only diehard Known World/Mystara fan out there…wow, no, not by a long shot. The Mystara fan community is one of the most dedicated in gaming. In addition to holding a torch for BECMI/Rules Cyclopedia-era D&D, they’ve taken it upon themselves to continue mapping and describing the remainder of Mystara as part of the fan community based out of the Vaults of Pandius website and the stunning fanzine Threshold. I’ve only skimmed Threshold a little, but it is stunning work on par with the Pathfinder fanzine Wayfinder for the amount of effort the fans put in and the quality that comes out. Kudos to everyone involved!

“The Voyage of the Princess Ark” is a testament to the creative heights one writer could achieve in a fantasy world.

“The Voyage of the Princess Ark” deserves to be spoken of in the terms we use for Pathfinder’s Golarion; AD&D’s Dark Sun, Planescape, and Al-Qadim; and Vampire the Masquerade’s World of Darkness. And Bruce Heard deserves pride of place in the company of Greenwood, Grubb, Weis, Hickman, and others of his era.

Heard showed us that simple rules didn’t mean a less complex world. Heard showed us that a few lines of monster description could be blown out to fill entire nations. Heard showed us that the cultural diversity of our own world could inspire our fictional ones. Most importantly, he showed that if you put in the work month after month, you could achieve amazing things. And he did it for a neglected fanbase of underdogs and windmill-tilters. He championed an audience and a world when no one else would.

“The Voyage of the Princess Ark” is also why I spent nearly seven years serving up monster ideas for another underdog fanbase. And the inspiration and work ethic I took from it is a big part of why I’m lucky enough to occasionally be freelancing on a professional basis today.

Three years isn’t a long time in fantasy fandom. If Elminster and Drizzt are Star Trek, perennially chugging along, and Harry Potter is Star Wars, a brilliant core surrounded by progressively less compelling follow-ups, then “The Voyage of the Princess Ark” is Firefly, a ragged crew whose sojourn was cut short, but whose legacy far outstrips its impact at the time.

Or at least, that’s the way its legacy ought to be.

Give “The Voyage of the Princess Ark” a try. Maybe I’m overselling it. Maybe years of nostalgia have painted a picture rosier than the original could ever live up to. Maybe, in an era where outstanding fantasy worlds and strong writing are almost commonplace, current readers can’t perceive the lightning-in-a-bottle magic that was this series.

Maybe. But I think there’s something more there, something perennial, something of value even when placed side by side with the embarrassment of riches that is Pathfinder 1e/2e and D&D 5e.

The only way you’ll know is if you book a berth on the Princess Ark and see for yourself.

Happy flying.

#daily bestiary#the dailybestiary#books of magic#pathfinder#paizo#3.5#5e#dungeons & dragons#dungeons and dragons#d&d#dnd#BECMI#known world#mystara#the voyage of the princess ark#voyage of the princess ark#bruce heard

48 notes

·

View notes

Photo

From the 5 issue mini-series You Are Deadpool (2018). A choose your own style adventure that takes Deadpool through the decades of Marvel history.

The alternate covers parody various Role Playing Game products:

#1 Paranoia (second edition) ~ West End Games (1987)

#2 Marvel Super Heroes ~ TSR (1984)

#3 Dungeons & Dragons Expert Set ~ TSR (1981)

#4 Dice Man ~ Fleetway Publications (1986)

[Definitely the most obscure of the parody covers. Dice Man was a very short lived Choose Your Own Adventure comicbook series by the then publishers of the British comic 2000AD, home of Judge Dredd]

#5 GURPS Basic Set (first edition) ~ Steve Jackson Games (1986)

378 notes

·

View notes

Text

RPGaDay 2020: Day 30. Portal

RPGaDay 2020: Day 30. Portal

Midnight, one more night without sleeping, Watching till the morning comes creeping. Green door, what’s that secret you’re keeping?

Jim Lowe, Green Door

Role playing games are the gateway to adventure.

Once you step through that portal it unlocks a lot of imagination.

It was a TSR rpg that was my first portal into gaming: Advanced Dungeons & Dragons was the room I stepped into back in…

View On WordPress

1 note

·

View note

Photo

D&D RPG TALES FROM THE YAWNING PORTAL HARDCOVER

WIZARDS OF THE COAST

When the shadows grow long in Waterdeep and the fireplace in the taproom of the Yawning Portal dims to a deep crimson glow, adventurers from across the Forgotten Realms, and even from other worlds, spin tales and spread rumors of dark dungeons and lost treasures. Some of the yarns overheard by Durnan, the barkeep of the Yawning Portal, are inspired by places and events in far-flung lands from across the D&D multiverse, and these tales have been collected into a single volume. Within this tome are seven of the most compelling dungeons from the 40+ year history of Dungeons & Dragons: Against the Giants, Dead in Thay, Forge of Fury, Hidden Shrine of Tamoachan, Sunless Citadel, Tomb of Horrors, and White Plume Mountain. D&D`s most storied dungeons are now part of your modern repertoire of adventures, providing fans with adventures, magic items, and deadly monsters, all of which have been updated to the Fifth Edition rules.

click for best comics talk