#Colombo & Co. cigarmaker

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

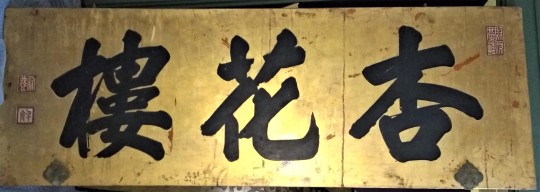

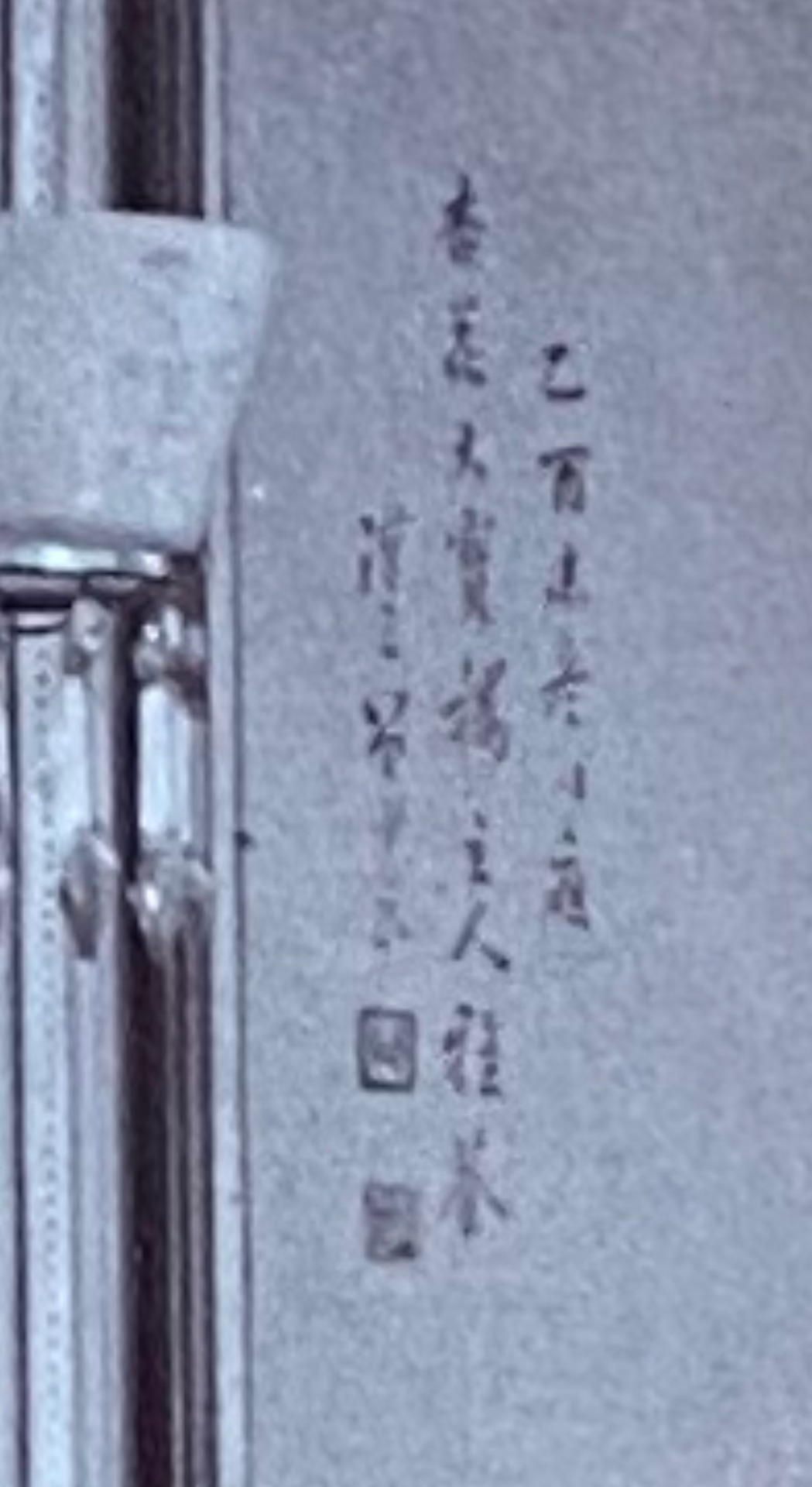

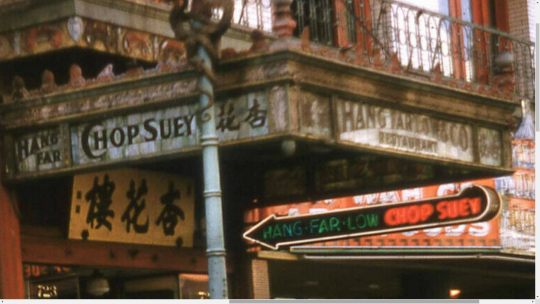

The business signage for the Hang Far Low restaurant. Photograph by Doug Chan (from the collection of the Chinese Historical Society of America)

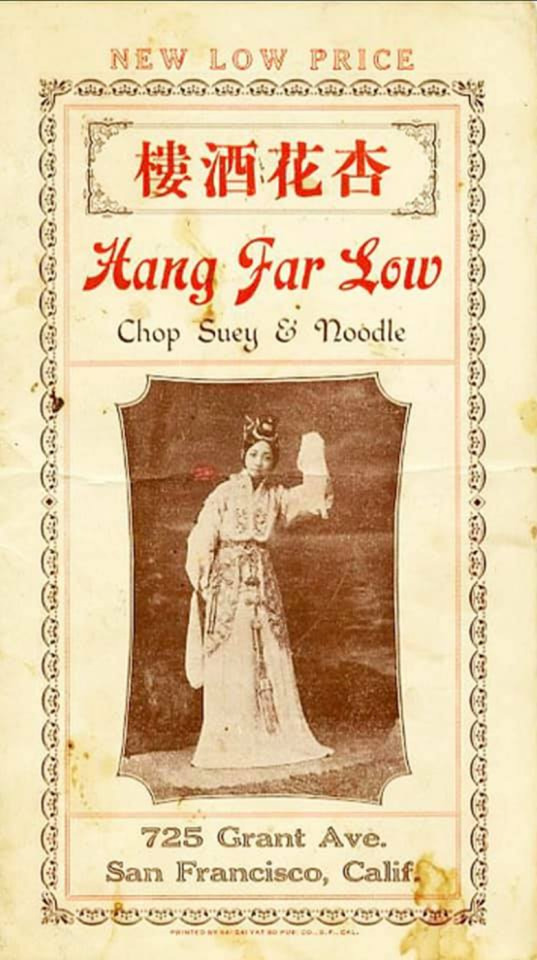

Hang Far Low - 杏花樓: Banquet Culture Starts Here

When Thomas Chinn, the first among the co-founders of the Chinese Historical Society of America, sat down with Ruth Teiser for a series of 12 interviews with the Regional Oral History Office, he and his spouse Daisy L. Wong Chinn provided a wide-ranging and fascinating supplement to his book, Bridging the Pacific, San Francisco Chinatown and its People, the first comprehensive account of this major and unique community.

At one point during the interview, Chinn picked up his treasured copy of the 1876 Bishop Directory of Chinese businesses and pointed to the name of one restaurant: Hang Far Low (杏花樓).

“It was started prior to 1876,” Chinn said of what he asserted was the most sumptuous Chinese restaurant in the West, “and we don’t know how much earlier–maybe five or ten years. It came all the way up and was destroyed in the 1906 earthquake and fire, and it was rebuilt practically in the same location, a door away maybe. In 1930 my wife and I were married there. That was over a half a century after this place was started. Then on our sixtieth wedding anniversary in 1980, which took place last year in June, my wife and I went back to the restaurant and had lunch there to celebrate the occasion. The name has changed; it was sold, as he [the controlling partner] had no descendants who wanted to continue it. He sold it around 1960, and the name is now The Four Seas Restaurant… .”

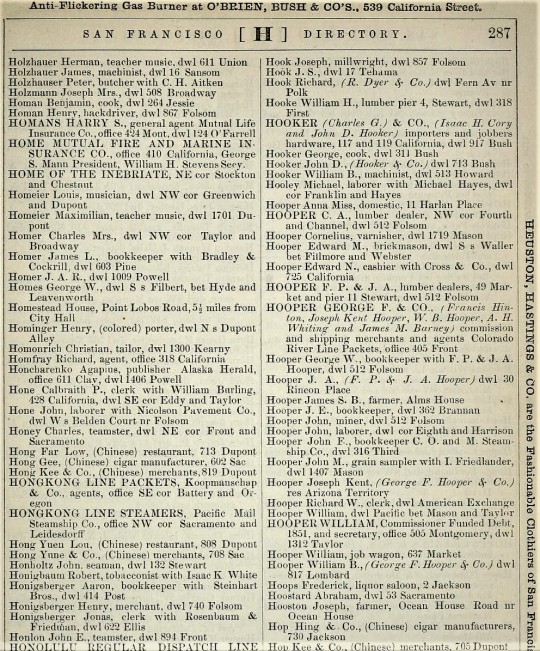

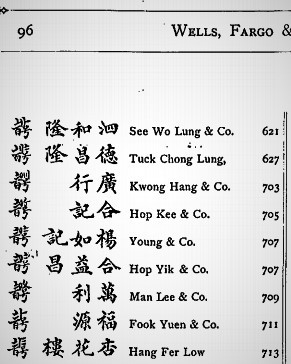

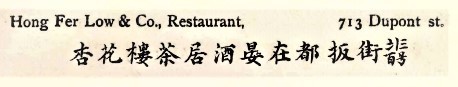

In that pre-internet era, Chinn lacked easily searchable, digital versions of San Francisco business directories that predated his copy of the 1876 directory. In fact, the Langley directory of 1868 lists a “Hong Far Low, (Chinese) restaurant” at 713 Dupont (here).

The Langley business directory of 1868 contains a listing for “Hong Far Low, (Chinese) restaurant, 713 Dupont”

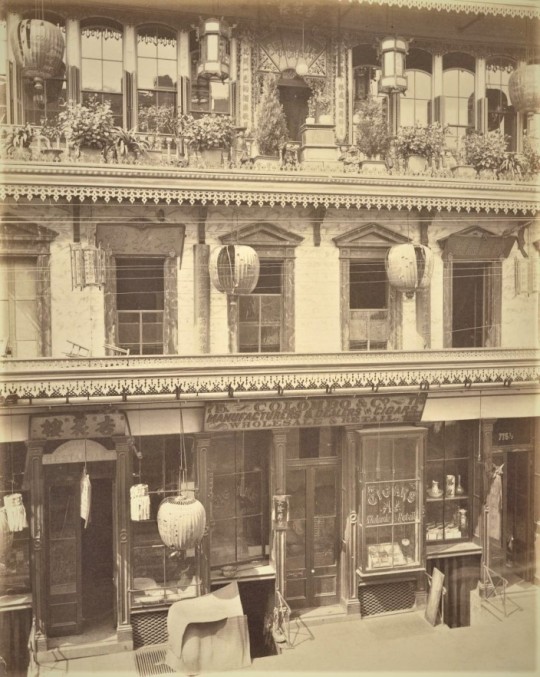

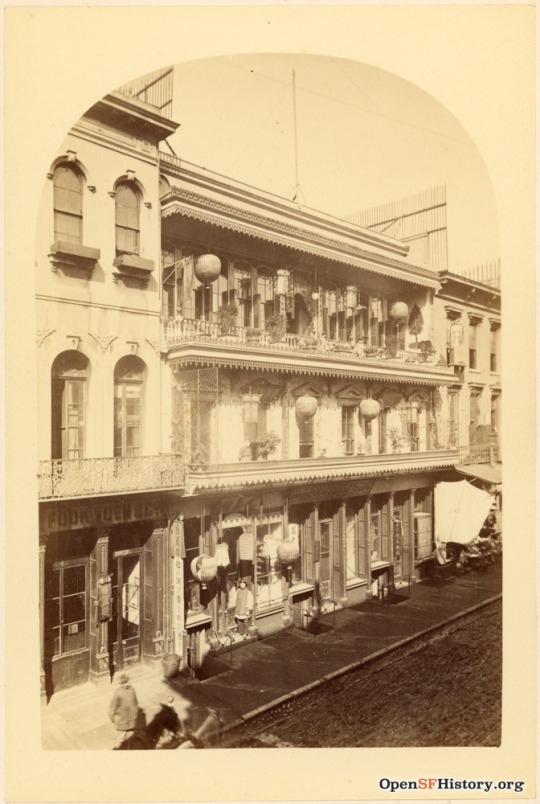

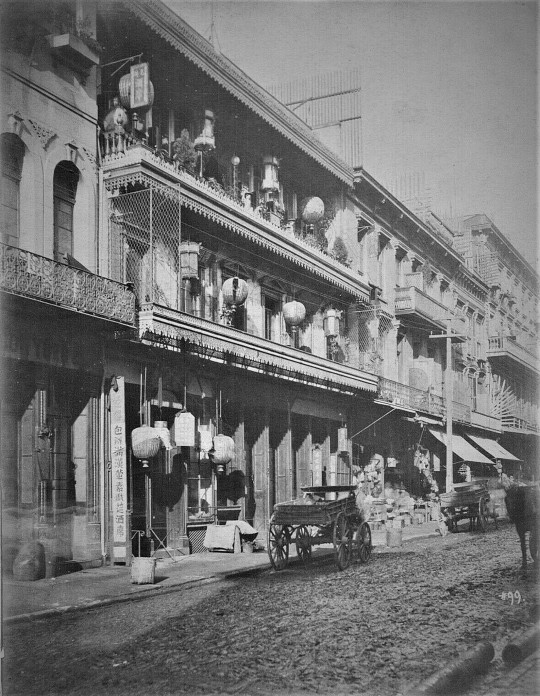

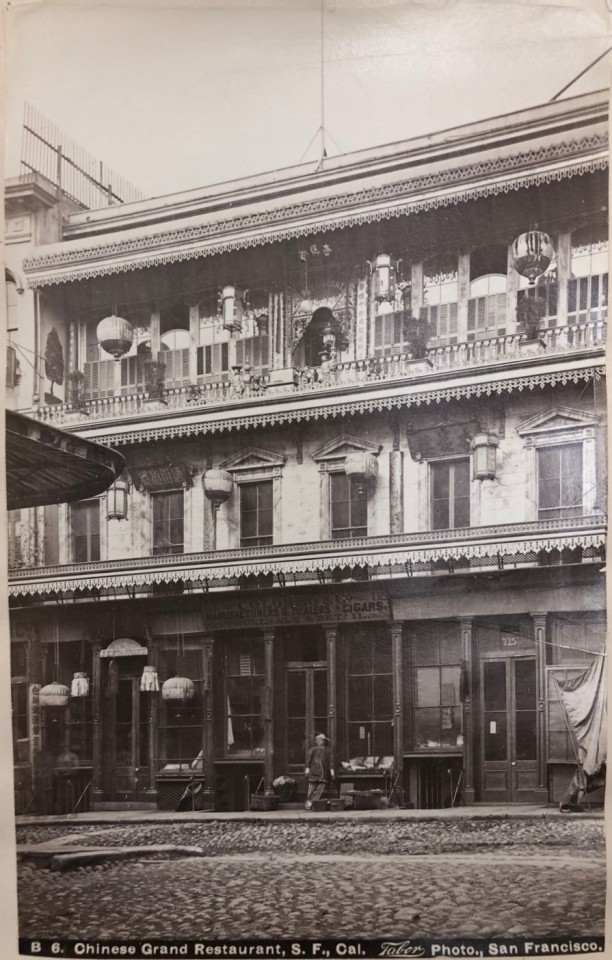

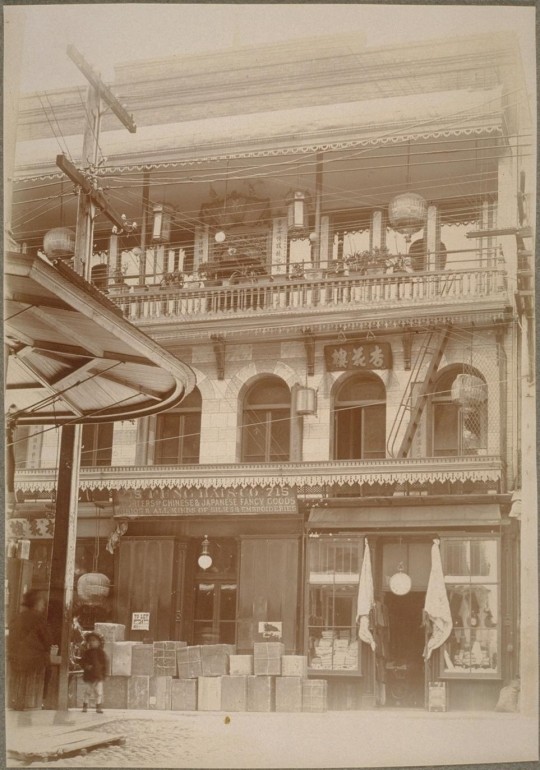

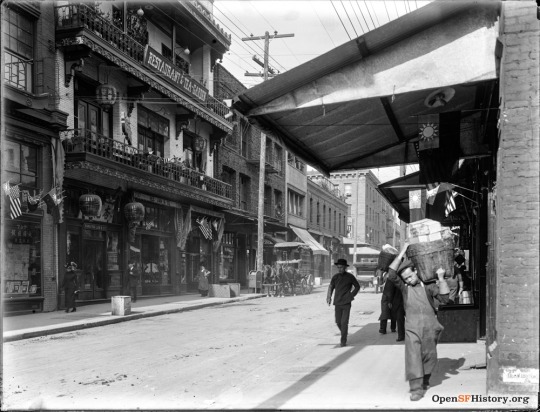

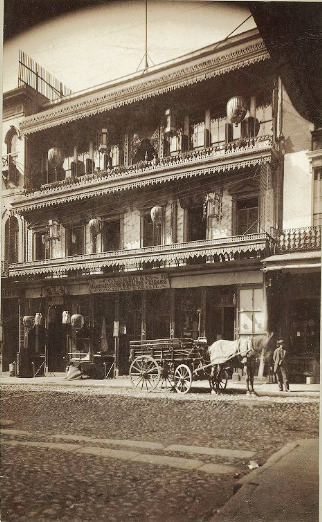

“Restaurant- Cigar Factory- Dupont St. San Francisco” c. 1869 - 1892. Photograph by Isaiah West Taber (courtesy of the California History Room, California State Library, Sacramento, California). This image shows the pioneer-era restaurant Hang Far Low (杏花樓). The English letter rendering of the name, i.e., “Hang Fer Low” in the sign above the ground floor entry door at 713 Dupont Street was used (subject to publisher typos) from at least 1872 to 1906. The earliest listing of the restaurant may be found in the 1868 Langley directory.

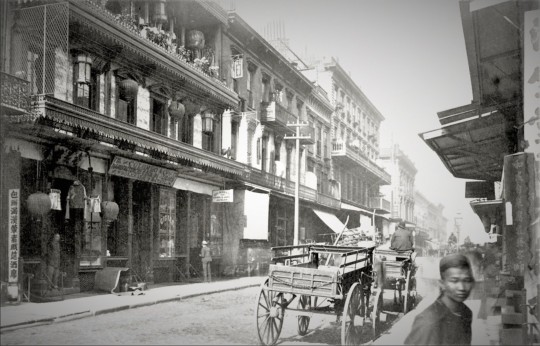

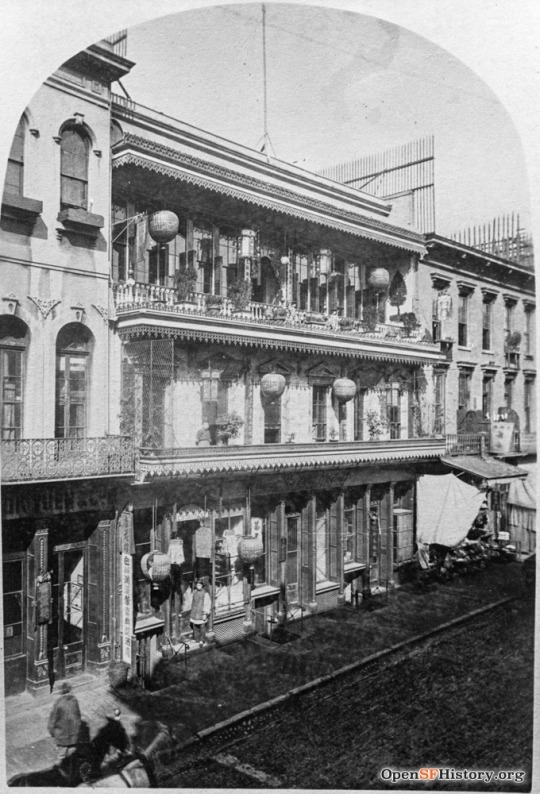

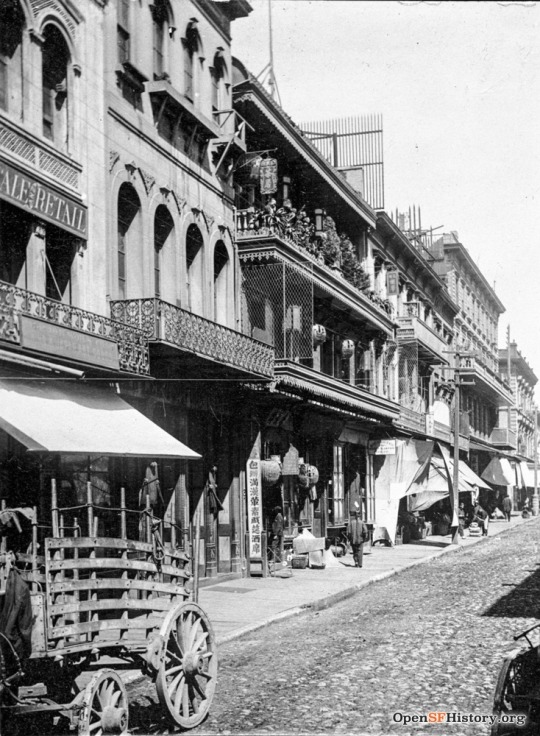

The west side of the 700-block of Dupont Street, c. 1880s. Photographer unknown. In spite of the Italian-type name, the cigar company occupying the central storefront of the building was Chinese-owned. Business directories from 1869-1892 listed in the first year a “Colombo & Co., (Chung Lung) manufacturer cigars, 715 Dupont.” Thereafter, however, the cigarmaker was usually listed as the “Colombo & Co., cigar factory, 715 Dupont.”

Moreover, the restaurant’s closure in 1960 did not represent the end of the story. Chef-restauranteur Brandon Jew resisted turning his back on a Grant Avenue building “steeped in Chinatown celebration history.” 145 years after Hang Far Low’s founding, Jew carried on the restaurant tradition in the same post-1906 building with his own popular eatery, Mr. Jiu’s. As Jew wrote in 2017 for vice.com:

“Before we renovated this space to become Mister Jiu’s, it was the Four Seas restaurant for about 50 years—hosting weddings, political fundraisers, and red egg ginger parties for the local community—and before that, it was a restaurant called Hang Far Low, which opened in the 1880s. With the shutdown of Four Seas and Empress of China—which closed around that time, too—the neighborhood lost two of the biggest and most historic places to celebrate within Chinatown. For long-established businesses, the competition to stay relevant or to become an institution is increasingly impossible.”

Cropped version of the photo by Carleton Watkins and published as stereo card “3759 Chinese Restaurant, Dupont near Sacramento, San Francisco” (from the Marilyn Blaisdell Collection / Courtesy of Molly Blaisdell). The above photo shows an elevated view north to the west side of Dupont Street showing Fook Yuen & Co. at 711 Dupont St., the Hang Far Low restaurant at 713 Dupont St., and Colombo and Co. Manufacturers & Dealers of Cigars, which occupied the ground floor store space at 715 Dupont St. from at least 1869 to 1892.

The “Hang (or Hong) Fer Low” restaurant’s listings in the 1871 and 1878 editions of the Wells Fargo directory of Chinese businesses (courtesy of the Wells Fargo Museum).

“3759 Chinese Restaurant, Dupont near Sacramento, San Francisco” c. 1882 (photograph by Carleton Watkins)

In 1888, The Bancroft Company published A Guide Book to San Francisco, by John S. Hittell, in which the restaurant’s interior space plan was described as follows:

“The Hang Fer Low Restaurant, on Dupont Street, between Clay and Sacramento, is the Delmonico’s of Chinatown. The second floor of this and other leading restaurants is set apart for regular boarders, who pay by the week or month. The upper floor, for the accommodation of the more wealthy guests, is divided into apartments by movable partitions, curiously carved and lacquered. The chairs and tables, chandeliers, stained window-panes, and even the cooking utensils used at this restaurant, were nearly all imported from China. Here dinner parties, costing from $20 to $100 for half a dozen guests, are frequently given by wealthy Chinamen. When the latter sum is paid, the entire upper floor is set apart for their accommodation, and the dinner sometimes lasts from 2 P. M. till midnight, with intervals between the courses, during which the guests step out to take an airing, or to transact business.”

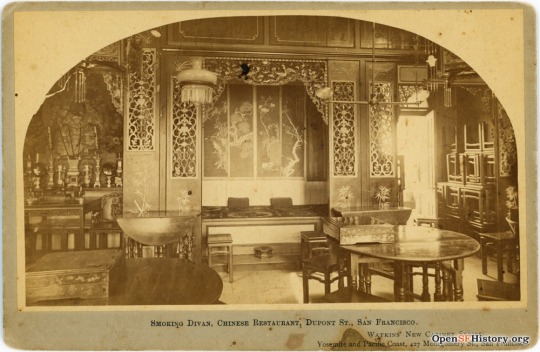

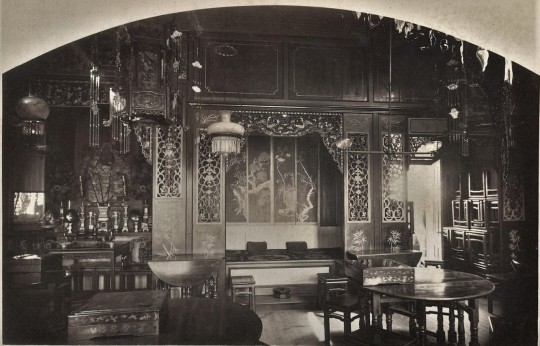

“Smoking Divan, Chinese Restaurant, Dupont St., San Francisco” circa 1880′s (Photograph by Carleton Watkins, courtesy of the Bancroft Library). An altar to the deity Guan Gung (seen at left) and seating alcove in a Hang Far Low dining room, 713 Dupont Street, ca. 1880’s.

“Smoking Divan—Chinese Restaurant [Boudoir Card B3760]” c. 1880′s. Photograph by Carleton Watkins from the collection of the Bancroft Library.

The above alternative print of the “Smoking Divan” photo by Watkins is significant in at least two respects. Under magnification, the print more clearly shows the carved inscription on the wooden box in the lower left-hand corner of the image, i.e., the Chinese characters for Hang Far Low (杏花樓). Although the above image has been cropped to enhance its resolution, the image as cataloged with the Bancroft Library bears the identification as one of Watkins’ “Boudoir Series” of photographs (B3759) as a restaurant on Dupont St. The next number in the series, B3761, was a restaurant on Jackson Street. Thus, the above two photos of the Smoking Divan provide a definitive glimpse of a portion of Hang Far Low’s remarkable interior furnishings. The image of 關公 (canto: “Guan1 Gung1″) appears in the shrine seen in the left portion of the image.

The interior dining rooms attracted other prominent photographers of the day, such as Isaiah West Taber.

“B5 Chinese Restaurant S.F. Cal.” Photograph by I.W. Taber (from the collection of the San Francisco Public Library).

The above photograph depicts the same dining room that was the subject of Watkins’ photo of the Smoking Divan, except that Taber’s shot looks down the hallway toward the shrine to the left of the divan.

Detail from “B5 Chinese Restaurant, S.F. Cal. Photo by I. W. Taber from the collection of the California State Library. The item on the table in the center of the photo is the same Hang Far Low-branded box which is seen more clearly in the Watkins photo of the Smoking Divan.

By the end of its first decade or more, San Francisco’s Hang Far Low had gained such notoriety that city residents had dubbed it “The Delmonico’s of the West.” The restaurant’s interior captivated the photographers of that era.

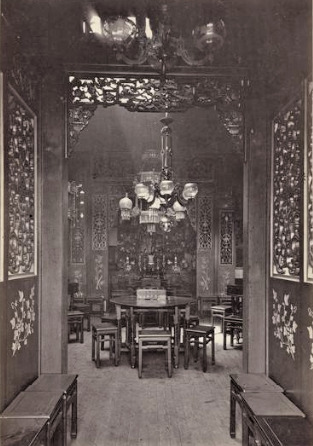

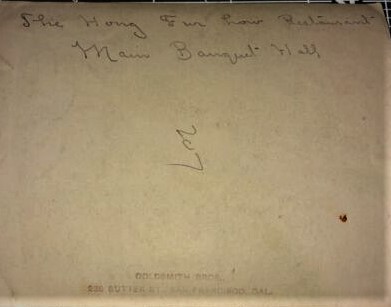

The Bancroft Library for years has only identified the above photo as an “interior of unidentified Chinese restaurant” c. 1880s. Comparison of this photograph by the Goldsmith Bros. with other copies in private collections indicates that the above photo depicts Hang Far Low’s main dining room.

The verso of a copy of the same dining room photo (on an auction website) identifies the “Main Banquet Hall” of the Hang Far Low restaurant shown in the Goldsmith Bros. photo.

Historian Judy Yung, in her 2006 pictorial book San Francisco Chinatown described about the main dining room as follows: “The top floor of Hang Far Low Restaurant – replete with inlaid panels, carved screens, and hardwood tables and stools imported from China – was reserved for the Chinese elite and their guests.”

The exterior elevation of Hang Far Low, and its decorative balconies, continued to fascinate the photographers of that era. The restaurant appears in numerous photos throughout the latter decades of the 19th century

The Hang Far Low restaurant and its adjacent buildings on the 700-block of Dupont Street, c. 1880. Photographer unknown. The vertical white sign 包辦滿漢葷素戲酒席 roughly advertises “banquet arrangements for Manchu and Han meat and vegetarian feasts.”

Another view of the Hang Far Low restaurant and its adjacent buildings, looking northwesterly up the 700-block of Dupont Street, c. 1880. Photographer unknown. The vertical white sign 包辦滿漢葷素戲酒席 roughly advertises “banquet arrangements for Manchu and Han meat and vegetarian feasts.”

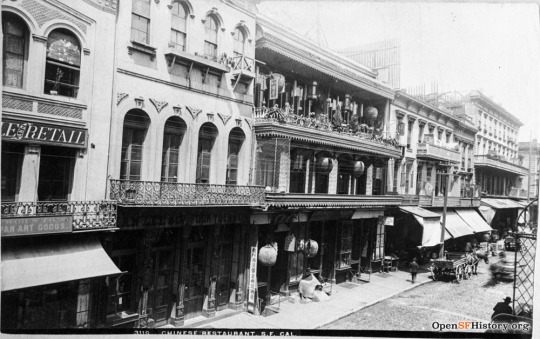

“3119 Chinese Restaurant, S.F. Cal., c. 1880s. Photographer unknown.

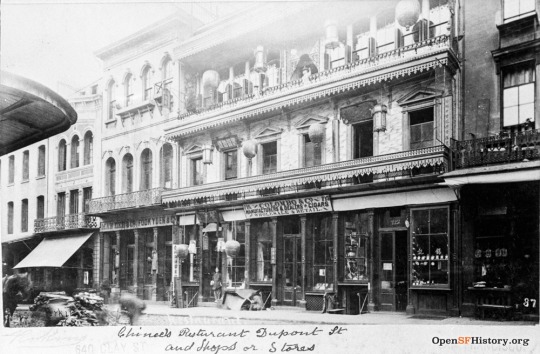

“Chinese Restaurant Dupont St. and Shops or Stores” The above photo was taken by Perkins circa 1885 (from the Marilyn Blaisdell Collection /Courtesy of a Private Collector). The southwesterly view of the west side of Dupont St. depicts from left to right Fook Woh & Co. Art Goods, Man Lee & Co. (709 Dupont), Fook Yuen & Co.(711 Dupont).

The Langley’s San Francisco directories for the years 1879 through 1883 (and probably for the balance of the decade) show both the variety store Man Lee & Co. and the drugstore Fook Yuen & Co. (the signage for which is seen clearly in the above photo), operated next door to the restaurant’s building at the addresses of 709 and 711 Dupont Street, respectively. (By 1894, other businesses had occupied the 711 Dupont address.)

Hang Far Low Restaurant as viewed from Commercial Street looking at the west side of Dupont Street, c. 1885. Photograph probably by Goldsmith Bros. (from the collection of the Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley).

“Chinese Grand Restaurant, S.F., Cal.” c. 1885. Photograph by Isaiah West Taber (or O.V. Lange?).

“The Orient Entertaining The Occident – On the occasion of their annual banquet, the Yinn Yee Kong Sow Society invited the Supervisors of San Francisco and their lady friends to a banquet in the Hong Fer Low restaurant. From a flashlight by Taber.” The caption indicates that Isaiah West Taber or an assistant presumably took this photograph using a “flashlight.” (Photography historians will recall that Sylvester M. Williams, a photographer, printer, and Oakland resident, worked for I.W. Taber & Co. from 1877 to 1878. Williams was known for his pioneering inventions in the field of flash photography, including the Williams Flash Light Apparatus.)

The above photograph of family association members (a branch of the Yee clan?) with members of the San Francisco Board of Supervisors provides early evidence that the Chinatown community understood the utility of feeding politicians, even if those same politicians exhibited hostility to the Chinese community. Perhaps significant, and given the relative lack of ornate decorations seen in other photographs of the Hang Far Low restaurant’s interior, the banquet appears to have been held in a lesser, more utilitarian, dining room.

In 2022, historian and author Roland Hui sent to me this comment about this banquet photo as follows:

“Taber’s flashlight photo showing a dinner gathering of Chinese and city supervisors was probably taken in 1897 since there’s a 2/21/1897 SF Chronicle article on a banquet hosted by the same Yinn Yee Kong Sow. However, I believe they made a typesetting error. It should have been Tinn (or Tin) Yee Kong Sow [ 親義公所; std. canto: “Sun Yee Goong Saw”)], the defense unit of the Four Brothers. Tin Yee was the new name of Mu Tin [(睦親; std. canto: “Mook Tun”] described in Bruce Quan’s book Bitter Roots. [The] [n]ame was changed in 1896.”

The rare shot of diners at a 19th century banquet prompts the question about the dining experience provided by Hang Far Low. The 1888 Bancroft Company publication, A Guide Book to San Francisco by John S. Hittell, described a typical banquet as follows:

“Among the delicacies served on such occasions are bird’s-nest soup, shark’s fins, Taranaki fungus (which grows on a New Zealand tree), Chinese terrapin, Chinese goose, Chinese quail, fish brains, tender shoots of bamboo, various vegetables strange to American eyes, and arrack (a distilled liquor made of rice); champagne, sherry, oysters, chicken, pigeon, sucking pig, and other solids and liquids familiar to the European palate also find their places at the feast. The tables are decorated with satin screens or hangings on one side, the balconies or smoking-rooms are illuminated by colored lanterns, and Chinese music adds to the charms of the entertainment.”

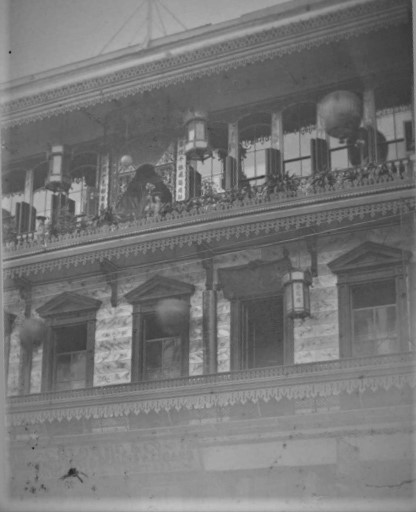

Balcony of Hang Far Low Restaurant ( c. 1885?). Photographer unknown (from the collection of the California Historical Society).

In her travelogue, Bits of Travel At Home, writer Helen Hunt Jackson (1830-1885) described the façade of the Hang Far Low restaurant as follows:

‘ Hang Fee[sic], Low & Co.’ keep it, and foreigners go there to drink tea. There is a green railed balcony across the front, swinging full of high-colored lanterns, round and square; tablets with Chinese letters on bright grounds are set in panels on the walls ; a huge rhinoceros stands in the centre of the railing : a tree grows out of the rhinoceros's back, and an India-rubber man sits at foot of the tree. China figures and green bushes in flower-pots are ranged all along the railing. Nowhere except in the Chinese Empire can there be seen such another gaudy, grotesque housefront. We make an appointment on the spot to take some of Hang Fee’s tea, on our way to the Chinese Theatre, the next evening . . .

“B 1184 In Chinatown, S.F. Cal.” c. 1885. Photograph probably taken by I.W. Taber (from the collection of the California State Library). The name, Hang Far Low, in Chinese characters (i.e., 杏花樓) is clearly visible on the lantern suspended in the upper left-hand corner of the frame.

The above two photographs were taken at different times (based on the presence of the deck chair and state of the plantings) from the balcony of the Hang Far Low restaurant, looking north up Dupont Street. The first photograph evokes the style and perspective of I.W. Taber who took a similar photo from the same balcony and sold prints under the B 1184 serial number.

The upper balcony of the Woey Sin Low at 808 Dupont appears in the right-hand third of both photos, situated across Dupont and northerly and beyond the intersection of Dupont and Clay Streets (shown at the mid-right part of the photo). Only horse-drawn wagons can be seen parked at the eastern curb of Dupont which suggests the decade of the 1880’s.

Close up of the second and third floor balconies of the Hang Far Low restaurant as viewed from the street level. Photographer unknown (courtesy of the California History Room, California State Library, Sacramento, California). The plants on the top floor and the darkened signage above the second floor window to the right of center appear consistent with the I.W. Taber photos of the balcony from the mid-1880′s, suggesting the year of the photo as circa 1885. The signage for the Colombo & Co. cigar store at 715 Dupont St. is barely visible at the bottom of the print.

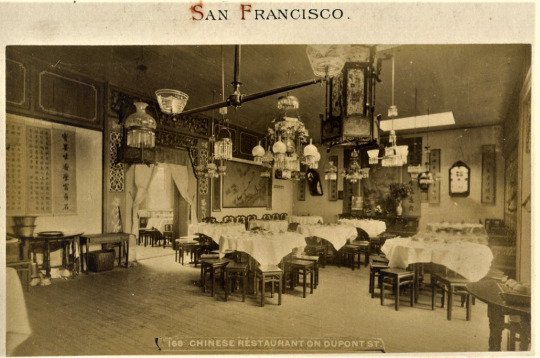

Researchers of pre-1906 Chinatown owe a debt of gratitude to pioneer photographers such as Isaiah West Taber, Carleton Watkins, and others for capturing images of the interiors of the neighborhood’s grand restaurants. However, the surviving prints or plates left scant information about particular photographs, making the job of identifying restaurant interiors difficult even upon close examination.

Fortunately for Chinatown historians, Taber apparently took a series of photos of one of Hang Far Low’s mid-level dining rooms from different angles and at different times. Thus, a comparison of several photos provides important clues to identify positively a principal dining room of one of Chinatown’s legendary establishments, Hang Far Low (杏花樓), during the late 1880s.

Chinese Restaurant c. mid-1880s. Photograph by I.W. Taber from the collections of the California Historical Society and the Bancroft Library.

“168 Chinese Restaurant on Dupont St.” c. mid-1880s. Photograph on card attributed to I.W. Taber.

Close up of “Chinese Restaurant on Dupont St., S.F. Cal.” c. mid-1880s. Photograph attributed to I.W. Taber.

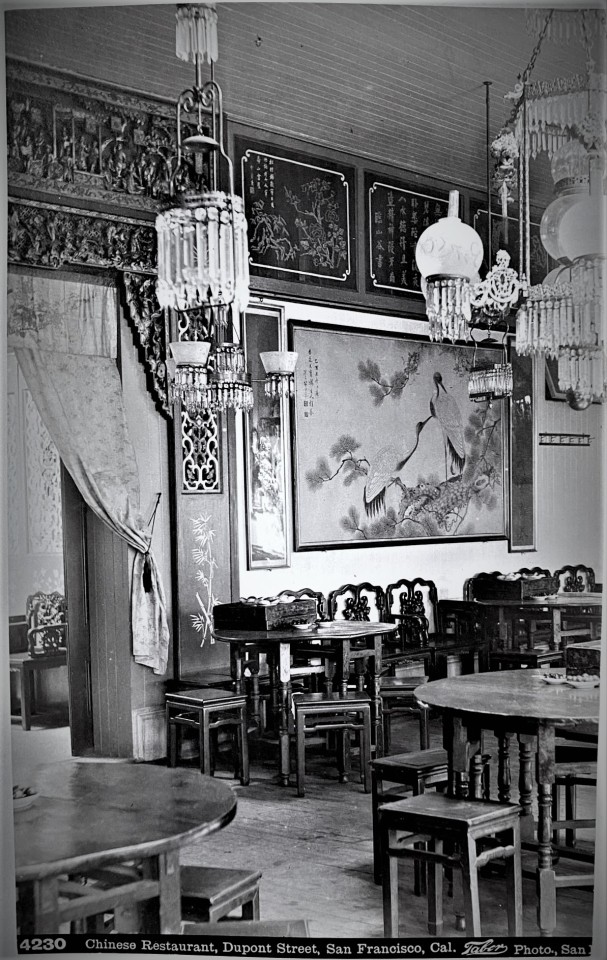

“4230 Chinese Restaurant, Dupont Street, San Francisco, Cal.” Photograph by I.W. Taber and print bearing a date of April 1, 1889 (from the private collection of Wong Yuen-ming).

Identification of the preceding two photographs of the same dining was only made possible thanks to Taber’s printing photo no. 4230, a detail of what was probably a westside interior wall of the dining room which shows clearly two important clues about its location. Taber took this photograph during the day and without the banquet tablecloths and place settings. As a result, the Hang Far Low- branded boxes (seen previously in Watkins’ “Smoking Divan” photo) were placed back on at least two tabletops.

Enlargement of “4230 Chinese Restaurant, Dupont Street, San Francisco, Cal.” Photograph by I.W. Taber and print bearing a date of April 1, 1889 (from the private collection of Wong Yuen-ming).

A close inspection of the box in the center of photo no. 4230 reveals the Chinese characters for the Hang Far Low restaurant (from right to left: 杏花 ), as well as the same detail on the panel of the wooden screen seen in the background.

The case for locating the dining room shots at Hang Far Low is further bolstered by the inscription seen in the upper left corner of the wall painting.

Enlarged detail from “4230 Chinese Restaurant, Dupont Street, San Francisco, Cal.” Photograph by I.W. Taber and print bearing a date of April 1, 1889 (from the private collection of Wong Yuen-ming).

On the left side of the wall painting the first two characters (read vertically from right to left) are 乙酉 pinyin: “Yiyou”; canto: “Yuht Yau”) indicates, according to the collector Wong Yuen-ming, the date around which the painting was given to the restaurant, which “might be 1885 or any 60 years before.” The center or second line of characters appears to read: 杏花大賣場 (lit.: “ “; pinyin: “Xìng huā dà màichǎng”; canto: “Hahng Fah dai mai cheung”). Assuming that the characters 杏花 refer to the restaurant, Wong surmises that the 大賣場 represents a form of exhortation or wish for Hang Far Low to make money.

Exterior of Hang Far Low (photographer unknown, c. 1894)

By the 1890s, when the above photo was taken (from the west end of Commercial St. looking at the restaurant situated on the west side of Dupont Street), the Colombo & Co. cigar store had departed, and the 715 Dupont Street address in the building had become a gift bazaar. The view of the second floor shows alterations to the façade and arched window frames with more prominent Chinese character signage. A dozen years later, the building would be destroyed completely in the Great Earthquake and Fire of 1906.

Post-earthquake exterior of Hang Far Low restaurant (photographer unknown, c. 1907).

Chinatown was rebuilt in place after the earthquake and fire, and a new home for the old Hang Far Low restaurant was built in 1907 into which the new restaurant would move at 735 Grant Avenue. This photo showing the new restaurant was taken from approximately the same location on Commercial Street as shown in pre-1906 photos. The striking addition of an oriental-style cupola on the roof, and visible from the street, exemplified the architectural flourishes of the new “Oriental City” into which the neighborhood had been transformed. The availability of “Chop Suey” is prominently advertised by signage on the second floor balcony. The Hang Far Low sign above the door is seen at left, and it reposes today in the collection of the Chinese Historical Society of America. The awning of the Hee Jan furnishings store can be seen in the center space of the store frontage at 737 Grant.

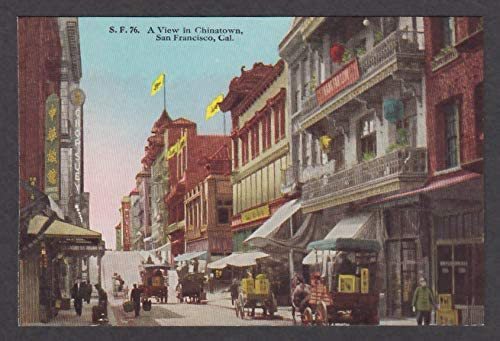

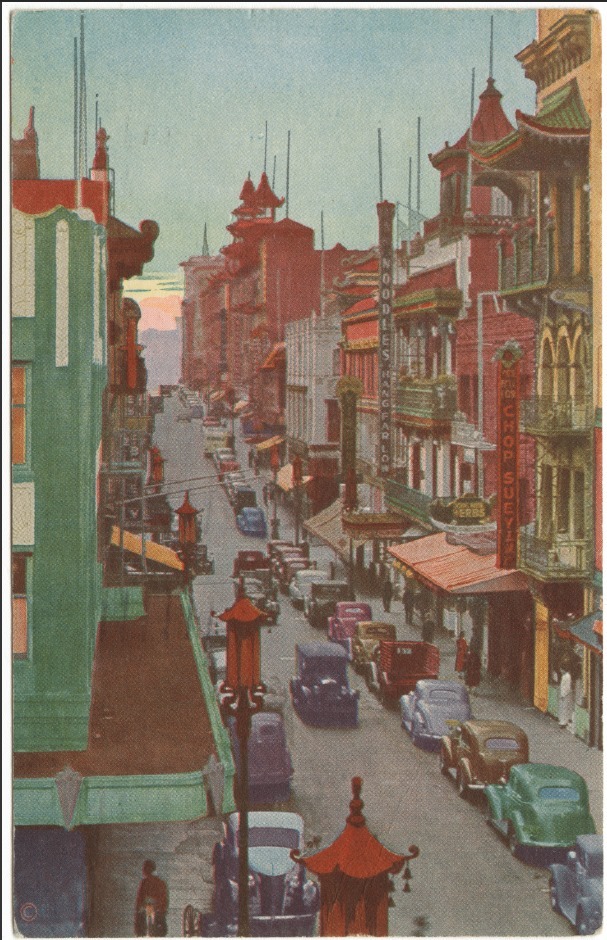

“S.F. 76. A view in Chinatown, San Francisco, Cal.” Given the vintage of the signage depicted in the postcard, the painting appears to depict the new post-1906 Chinatown and is itself exemplary of the success of the community’s survival strategy to cater to the tourist trade.

The new banquet dining room of Hang Far Low (c. 1908 by Martin Behrman). The third floor banquet hall of the new Hang Far Low restaurant one year after the construction of the new building admitted plenty of sunlight, but never equaled the opulence of the pre-1906 grand dining room.

“Banquet in San Francisco Chinatown” c.1910. Photographer unknown (from the Jesse B. Cook Collection at The Bancroft Library).

As is evident from the above photo, purportedly taken in 1910 to honor members of the San Francisco Board of Supervisors, the merchant and other leaders of the Chinese community resumed using Hang Far Low for cultivating influence with public officialdom.

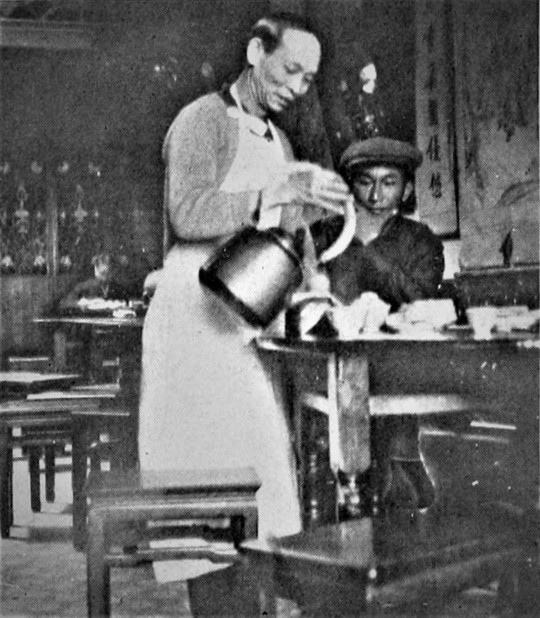

“Common Dining Room” c. 1911. Photograph by Louis J. Stellman (courtesy of the Society of California Pioneers).

Historian July Yung wrote in her pictorial book San Francisco’s Chinatown (published by the Chinese Historical Society of America) about the post-1906 incarnation of Hang Far Low’s serving Chinatown’s workers as follows:

“The middle floor of Hang Far Low housed the kitchen and served more common fare to Chinese shopkeepers and workers during the day. Some restaurants offered monthly coupons for meals at different prices. Cheaper restaurants that served simple rice and noodle dishes were usually located in the basements of buildings.”

A waiter pours tea for a customer in Hang Far Low’s middle floor dining room, c. 1911. Photograph by Louis J. Stellman (from “Camera Craft – A Photographic Monthly” ed. Sigismund Blumann, vol. XL, no. 1 (January 1933). Stellman took this photograph using a small box camera. “Another luck shot was in the Hang Far Low restaurant,” Stellman wrote 22 years later. “Setting my camera on a table I chanced a fifth of a second exposure of a Chinese waiter pouring hot water into a tea bowl. He was talking at the time but the print shows little movement. “

Photograph of a banquet held in the main dining room of Hang Far Low, circa 1912. (Photographer unknown from the collection of Bruce Quan). The event was possibly hosted by prominent businessman Lew Hing.

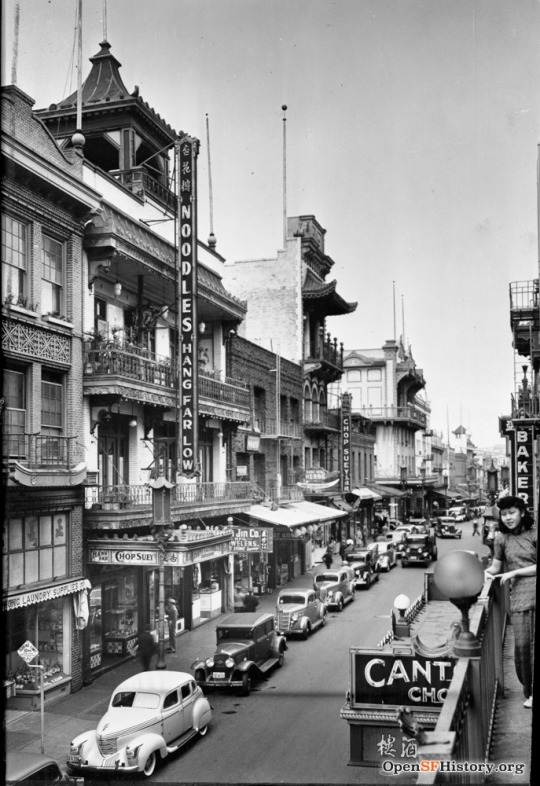

Hang Far Low restaurant looking northwest across Grant Avenue, c. 1917. Photographer unknown from a private collection.

The 1907 building (designed by architect Albert Pissis) appears a decade later with additional signage advertising a Restaurant and Tea Garden from the third floor balcony. A man carrying basket approaches the photographer’s position on the east side of Grant Avenue. Above the next door entryway at 717 Grant, the American flag shares space with the white sun on sky blue background flag of the six year-old Republic of China, as does the entrance to the Jee Jan store at 737 Grant.

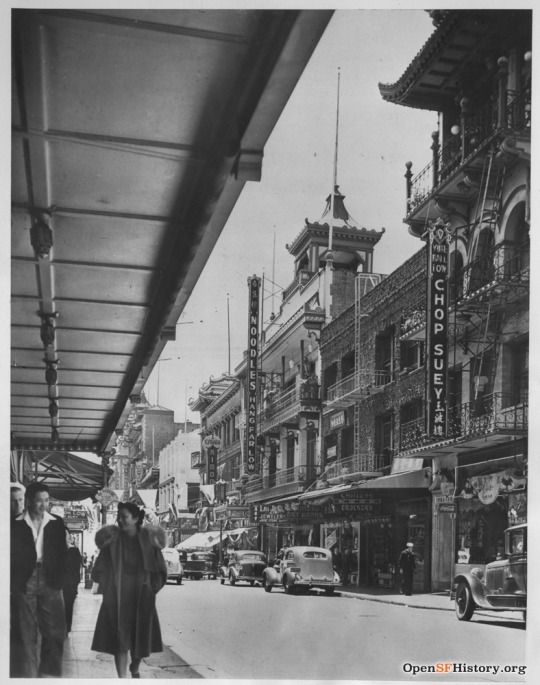

Vertical, neon signage in the daytime for Hang Far Low and Yoke Ball Low restaurants appear prominently in this photograph from 1939 of Grant Avenue’s west side. The “Yuck Ball Low” restaurant (as listed in the Polks Crocker-Langley directors of 1939 was located at 747 Grant Avenue.

Architectural historian Hongyan Yang writes about Hang Far Low’s building in her upcoming book as follows:

“… The property was owned by Paul Fleury and Leonide Arizerais. This three-story three-bay building was designed by Albert Pissis and completed in 1907. Among one of the first generation American architects trained in Paris, Pissis was highly influenced by the Baroque and Renaissance traditions, and was actively involved in rebuilding downtown San Francisco after the 1906 earthquake. His design of the Hang Far Low building also consisted of collections of Oriental details and decorations that were commonly employed in the buildings of Chinatown. In addition to the vibrant colors of green and red, the most evident feature was the cupola tower that perched on top of the building. Compared to typical cupola towers found in Renaissance-influenced architecture, Pissis dressed this square copula in an Oriental fashion, accentuated by the red and green color schemes and upturned eave ends to evoke a sense of exoticism associated with a Chinese pagoda tower. Different from the religious pagoda towers in China, the cupola tower kept its western ornamental connotation and was used vertically and scenically in the composition of Oriental architecture, without any adjacency to a monastery and religious significance. Different from the intricate structural system of a Chinese pagoda tower, it featured a much simpler structural system with straight crossed beams and columns. In fact, American architects were keenly aware that these newly constructed buildings with Oriental features like a pagoda tower did not represent traditional Chinese architecture… . “

The west side of the 700 block of Grant Avenue in 1945.

By Mar 10, 1945, when the above photograph was taken of the view north along the west side of Grant Avenue, a hard awning had been built over the sidewalk fronting the entrance to Hang Far Low restaurant. The bakery sign in the right of the photo over the woman’s left shoulder was for the old Eastern Bakery which operates today at 720 Grant Avenue.

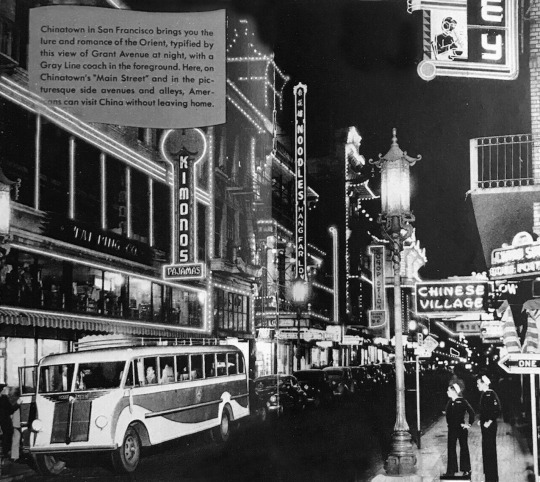

Nighttime on Grant Avenue during the 1940s, and the heyday of San Francisco as a Navy town.

A waiter (伙記; canto: “fo2 gei3) serves a table of postwar Chinatown businessmen probably in the middle dining room of the Hang Far Low restaurant on February 9, 1946. Photographer unknown (from the collection of the San Francisco Public Library).

A postcard of mid-century Grant Avenue.

A 1954 close up of the Hang Far Low awning signage over-hanging Grant Avenue. The sign over the doorway was salvaged and accessioned to the collection of the Chinese Historical Society of America.

The remodeled banquet room for the new Four Seas restaurant.

By 1960, the family of the controlling partner of the Hang Far Low restaurant no longer wished to operate it, and the establishment was sold in 1960 to operate under the new name of Four Seas.

The legendary eating establishment that had served San Francisco’s Chinatown for a century had come to an end.

The history of Hang Far Low implicates a less examined, but deeper, narrative, wherein the Chinese learned that the banquet halls could serve as tools for civic engagement with the greater San Francisco community and its political institutions.

In the first quarter of the 21st century, however, banquet culture in SF Chinatown has waned substantially due to a confluence of factors. Demographic changes, pandemic lockdown and stigmatization, the dispersion of Chinese communities throughout the Bay Area, and the corresponding decline in Chinatown’s role during the era of exclusion and segregation as the principal market and financial hub had all converged to end the 170 year-old institution of the banquet hall in Chinatown.

The building which housed the Hang Far Low and Four Seas restaurants at 731 Grant Avenue, January 5, 2024. (Photograph by Doug Chan). Since the rebuilding of San Francisco’s Chinatown after the disaster of 1906, the building continues to house the restaurant operations of the highly-rated Mister Jiu’s, a contemporary Chinese American and bar. The entrance to the modern-day restaurant is located on the west side of the building at 28 Waverly Place. As almost a metaphor for the reinvention of Chinatown and the restoration of its banquet rooms, the Executive Chef, Brandon Jew, and his team have gradually expanded operations within the building to its remodeled top floor’s “Moongate Lounge.”

[updated: 2024-1-19]

#Hang Far Low#Chinatown banquet culture#I.W. Taber#Carleton Watkins#Louis Stellman#Thomas W. Chinn#Long Kong Tin Yee Association#Tin Yee Association#Mu Tin Association#Brandon Jew#Judy Yung#Four Seas restaurant#Colombo & Co. cigarmaker

0 notes

Photo

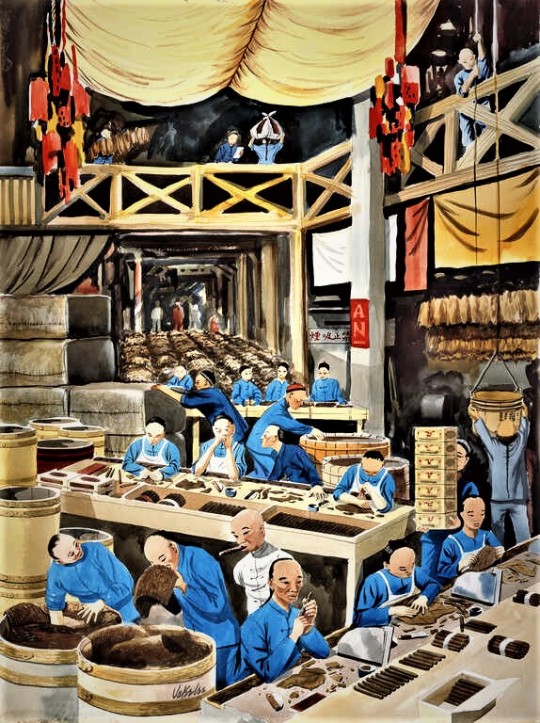

“Cigar Makers” Watercolor by Jake Lee (from the collection of the Chinese Historical Society of America)

Rolling Their Own: SF Chinatown’s Cigar Story

A short article on The San Francisco Standard news site recently acquainted readers with the colorful and contentious story of Chinese cigar manufacturing in pioneer San Francisco of the 19th century.

As historian Nicholas Sean Hall has written about its rise, “[t]he cigar-making industry, just as had been the case with gold mining two decades prior, had outgrown its artisanal phase. A newly developed mold had simplified cigar shaping and it no longer made sense for one individual to see the entire process through from beginning to end. As a result, the industry now relied on enormous, highly capitalized cigar-making firms, which, through routinization, allowed these firms to hire unskilled laborers (i.e., the Chinese) to begin the process of cigar making.”

The patent drawing of DuBrul’s innovative cigar mold. According to Tony Hyman “[n]o evidence exists as to when moulds arrived in the U.S. Some writers claim a date as late as 1870. Most place it in the 1860’s.”

Five decades ago, the Chinese Historical Society’s first generation of historians wrote about the city’s cigar industry in the groundbreaking publication, A History of the Chinese in California: A Syllabus (Thomas W. Chinn, Editor, pub. Chinese Historical Society of America, 1969) as follows:

“The first large scale introduction of Chinese into manufacturing occurred in the cigar industry. The traditional date is given as 1859 when Englebricht and Levy hired Chinese workers in their establishment in San Francisco.[ ] The Segar (cigar) Maker’s Association in November of that year passed a resolution in opposition to the hiring of these workers, claiming that the action “is tending to destroy the true basis of our country's prosperity” and that it “will prove destructive to the general welfare, and retard the advance of civilization and the manifest destiny of our country** and “will bring want and suffering into the homes of our people.” [ ]

“Subsequent events proved that the cigar makers’ alarm was premature since, at that time, as the white miners were leaving the diggings, Chinese were returning to the mines. . . . The first period of the expansion of the cigar industry did not actually take place until after 1864. San Francisco then became the center of the industry in California. The total value of cigars manufactured in the city jumped from $2,000 in 1864 to $1,000,000 in 1866.[] By 1868, California had displaced Massachusetts as the fourth large cigar producing state.[ ]

“Chinese quickly learned the trade and soon set up their own factories, selling the same quality products at lower prices. Even as early as 1866 half of San Francisco's cigar factories were Chinese-owned.[ ] However, in view of the anti-Chinese sentiments, many Chinese firms, especially in later years, used Spanish names as Cabanes & Co., Ramirez & Co., etc.[ ]

Detail from “Cigar Factory- Dupont St. San Francisco” c. 1869 - 1892. Photograph by Isaiah West Taber (courtesy of the California History Room, California State Library, Sacramento, California). In spite of the Spanish-type name, the cigar company occupying the central storefront of the building was Chinese-owned. (Its vertical Chinese signage 長隆邦記 [canto: “cheung loong bong gay”] appears to the left of the entrance.)

“A horse and cart in front of Colombo & Co., a store in a building of slightly Asian architecture,” c. 1892. Photograph by Charles Roscoe Savage (from the L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University). The building at 713 - 715 Dupont St. housing the Colombo & Co wholesale & retail store and the legendary Hang Far Low (杏花樓) restaurant on the two upper floors. Business directories from 1869-1892 listed in the first year a “Colombo & Co., (Chung Lung) manufacturer cigars, 715 Dupont.” Thereafter, and perhaps in response to growing anti-Chinese harassment, the cigar maker was listed as the “Colombo & Co., cigar factory, 715 Dupont.” Although its business premises were destroyed in the 1906 quake and fire, the Colombo Cigar Company (廣 和 源 呂宋 煙; canto: “gwong wo yuen leuih sung yeen”) would resume operations thereafter on Vallejo Street. The English letter rendering of the name, i.e., “Hang Fer Low” in the sign above the ground floor entry door at 713 Dupont Street (at left) was used from at least 1872 to 1906.

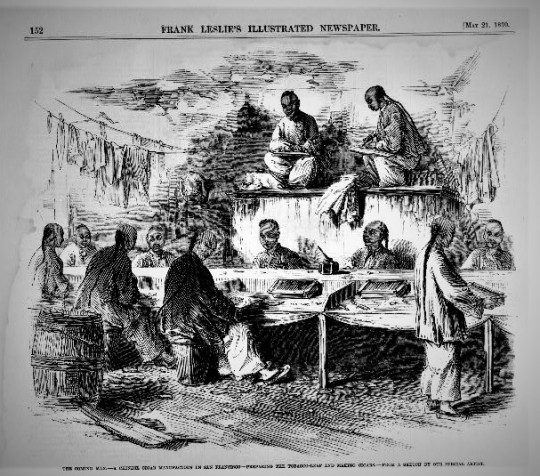

“The Coming Man – A Chinese Cigar Manufactory in San Francisco – Preparing the Tobacco-leaf and Making Cigars,” from a drawing in Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, May 21, 1870 (from the collection of the Library of Congress).

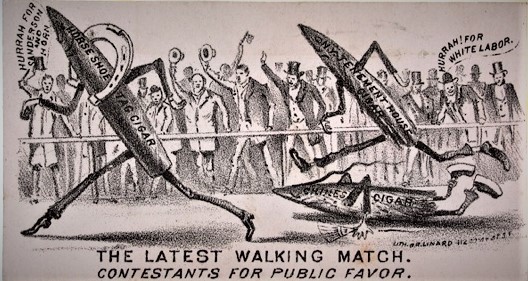

“The Latest Walking Match.” In this political cartoon, the makers of cigars in New York tenement houses are shown surpassing Chinese cigar makers in a walk race which was popular in the 1870′s.

“During the 1870’s, through the years of the most violent anti-Chinese agitation in California, Chinese labor was predominant in the cigar-making industry.

“In the mid-1880’s the Cigar-Makers Union (white) aided by the anti-Chinese sentiments of the time, and by the Chinese Exclusion Act, finally succeeded in virtually eliminating Chinese from the cigar industry. However, with the passing of the Chinese from the scene, the cigar industry itself in California also declined.[ ]

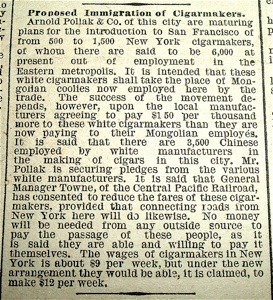

A short article announces plans to essentially fire Chinese workers and replace them with New York cigar makers, as reported in the Evening Bulletin of June 5, 1882, and a month after the enactment of the Chinese Exclusion Act.

“The following table shows the relative number of Chinese cigar workers for various years:

Place Year Chinese Total San Francisco - 1867 450 500 San Francisco - 1870 1,657 1,811 San Francisco - 1876-7 5,500 6,500 San Francisco - 1878-9 4,000 6,000 San Francisco - 1892 700 1,200 San Francisco - 1904-5 800 300

Chinese cigar workers in California worked in any one of the following three types of establishments:

1. Firms employing Chinese but work directed by a white foreman. 2. Firms furnishing tobacco to a Chinese contractor, who made them into cigars at a fixed contract price per thousand. 3. Firms owned and operated by Chinese, many of which were conducted on the cooperative system.[ ]

“Cigar Making in Chinatown, San Francisco” lithograph from the collection of the Bancroft Library. In 1885, the special supervisors’ committee charged with mapping Chinatown found 427 sites for cigar making.

“A typical Chinese cigar factory is a fifteen foot by twenty foot room with a gallery for greater space utilization, where nearly fifty men worked.[ ] Chinese cigar workers were usually paid on a piece-work basis. The pay scale varied from fifty cents to seventy cents per hundred, and a worker made about two hundred cigars a day.[ ]

“The Tung Te Tang (Tung Dak Tong, “Hall of Common Virtue”) [同德堂] was the labor guild to which Chinese cigar workers belonged. The rules of this guild stipulated that guild members shall not work alongside non-guild members. When a controversy occurred between an employer and his employees, the guild agent would report the incident to the guild. The guild then appointed a committee to investigate and if the investigators found that a grievance existed, a strike was then declared. . . .

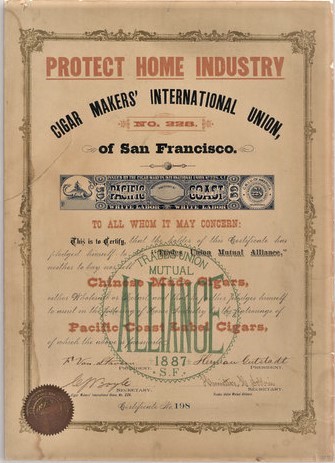

“Protect Home Industry,” a certificate issued in 1887 by the Cigar Makers’ International Union in San Francisco (from the collection of the Bancroft Library). The certificate reads: TO ALL WHOM IT MAY CONCERN: This is to Certify, that the holder of this Certificate has pledged himself to the “Trades Union Mutual Alliance,” neither to buy nor sell Chinese Made Cigars, either Wholesale or Retail, and that he further pledges himself to assist in the fostering of Home Industry by the patronage of Pacific Coast Label Cigars, of which the above is facsimile. TRADES UNION MUTUAL ALLIANCE 1887 S.F. . . .”

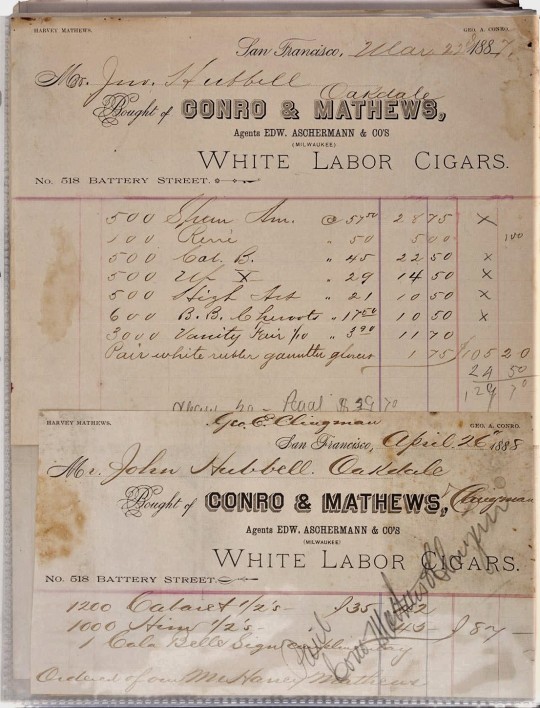

Invoice, dated March 22, 1887, and receipt of April 26, 1887, for “White Labor Cigars”

“Chinese were also employed in the related industry of making cigar boxes.

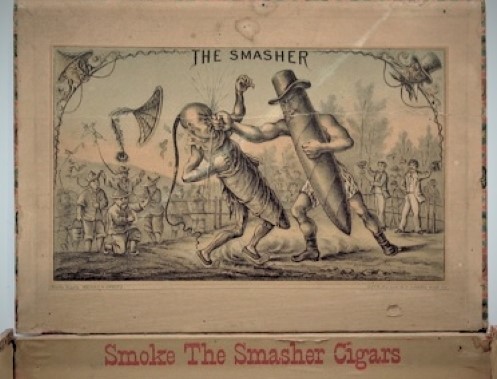

“The Smasher” lithograph adorns a cigar box. Union label cigars made by white labor often featured anti-Chinese cartoons.

“There were both white-owned and Chinese-owned factories employing Chinese labor. In 1881, Chinese made about one-sixth of the entire production in California.[ ] In 1904-05, there were five factories in San Francisco with 80 Chinese out of 140 workers.[ ] In contrast to their dominance in the cigar industry, only a small number of Chinese engaged in the allied cigarette industry.[ ]”

-- from A History of the Chinese in California: A Syllabus, Thomas W. Chinn, Editor, pub. Chinese Historical Society of America (1969)

Although the enactment of the Chinese Exclusion Act and its extension in 1892 had begun to reduce the Chinese labor force substantially, the harassment of Chinese cigar makers by trade unions, police, and the city’s Board of Health continued.

A police-escorted inspection by labor union officials of Chinese cigar makers as reported in the San Francisco Call, March 31, 1897.

Chinese cigar makers continued to operate even after the Great Earthquake and Fire of 1906. The 1913 international directory of Chinese businesses listed at least 30 cigar factories and companies in the San Francisco Chinatown area. As the deliberate, population-reducing effects of the Exclusion Act took effect, however, the fading presence of the once-dominant Chinese in the cigar industry accelerated, and a once robust industry of Chinese California passed into history.

“Chinese Cigar Manufactory on Merchant Street, San Francisco” as drawn for the Illustrated San Francisco News, 1869 (from the collection of the Bancroft Library)

“The Proud Father” c. 1905. Photo by Mervyn D. Silberstein (from a private collection). Silberstein specialized in photography of San Francisco Chinatown residents and producing hand-colored reproductions in “actual Chinese color combinations.” Silberstein’s own ads for his “Chinee-Graphs” promoted “[m]ost of these pictures were taken during the Chinese New Year festivities many years ago when the ancient customs were adhered to.”

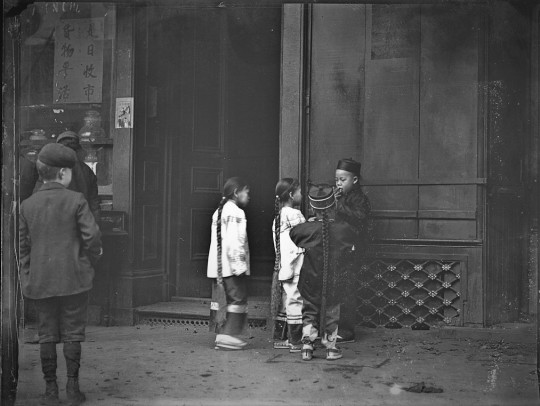

“His First Cigar” c. 1896-1906. Photograph by Arnold Genthe (from the collection of the Library of Congress).

[updated 2024-1-4]

#Chinese cigar makers#San Francisco Chinatown#Tung Te Tang or Tung Dak Tong#Chinese cigarmakers guild#Colombo & Co.#Dupont Street#Arnold Genthe#Mervyn D. Silberstein#Thomas W. Chinn#Merchant Street#Hang Far Low

1 note

·

View note

Photo

The view north of the 700-block of the west side of Dupont Street at the T-intersection with Commercial Street, c. 1890. The signage for the Sic Kee & Co. clothing store at 715-1/2, Hang Yek & Co. (恒益; canto: “hang4 yik1″) at 717, and a horse-drawn delivery wagon is parked in front of what was probably the Ching Wo grocery store. Just beyond the horse-drawn wagon parked at curbside, the vertical sign for the Choy Jee Tong & Co.(采芝堂; canto: choy2 zi1 tong4”) drugstore can be seen at the 725 Dupont address.

Dupont Street Stores of Old Chinatown

In the late 19th century, Dupont Street in San Francisco’s Chinatown was home to a lively array of Chinese businesses that catered to the needs of the local community. The photo record of the west side of Dupont between Commercial and Sacramento Streets is dominated by images of the balconies of the well-known Hang Far Low restaurant at 713 Dupont and the distinctive storefront of the Colombo & Co. at 715 Dupont. The rest of the northerly stretch of storefronts at 715-1/2, 717, 719, and 723 Dupont Street, which housed various enterprises, is often overlooked. However, they played an integral part in the daily, commercial life of old Chinatown.

Detail from the “Official Map of Chinatown in San Francisco” prepared under the supervision of a special committee of the San Francisco Board of Supervisors, July 1885 (from the collection of the Chinese Historical Society of America). The “CH Restaurant” (at left) was the Hang Far Low restaurant at 713 Dupont. The post-1906 replacement building replicated the restaurant’s rear entry/exit onto Waverly Place, a half block west of Dupont.

By the time the "vice" map commissioned by the San Francisco Board of Supervisors was published in July 1885, the commercial uses of the retail storefronts on the west side of Dupont Street (now Grant Avenue) in San Francisco’s Chinatown were well-established,. Businesses along the 700-block of Dupont Street included various Chinese-run enterprises, such as cigar-making, general merchandise, grocery, butcher, and Asian imports, and apothecary catering to both local and wider community needs. The Hang Far Low Restaurant (at 713 Dupont) had become a notable and destination eatery by at least 1867, serving the Chinese merchant elite and residents with decor and furnishings imported from China. Chinatown businesses in this area remained central to the neighborhood’s economy until the 1906 earthquake.

The “Hang (or Hong) Fer Low” restaurant’s listings in the 1871 and 1878 editions of the Wells Fargo directory of Chinese businesses (courtesy of the Wells Fargo Museum).

The west side of the 700-block of Dupont Street, c. 1880s. Photographer unknown (from a private collection). In spite of the Italian-type name, the cigar company occupying the central storefront of the building at 715 Dupont (above which the Hang Far Low restaurant operated), was Chinese-owned. Business directories from 1869-1892 listed in the first year a “Colombo & Co., (Chung Lung) manufacturer cigars, 715 Dupont.” Thereafter, however, the cigarmaker was usually listed as the “Colombo & Co., cigar factory, 715 Dupont.”

The Colombo & Co. listings as a cigar factory in the 1878 and 1882 editions of the Wells Fargo directory of Chinese businesses (courtesy of the Wells Fargo Museum). As was frequently the case with English language directories during this period, the 1882 Wells listing contained a spelling variant of the business name.

“167 Chinese Market on Dupont St.” c. 1894. Photographer unknown. Grant near Commercial circa 1890. The signage for the Hang Yeck & Co. store at 717 Dupont Street is clearly visible over an entryway.

One of the notable images from the block that has survived to this day is the Hang Yeck & Co. sidewalk displays at 717 Dupont Street. Hang Yeck (a.k.a. Yek) [恒益; canto: “hang4 yik1″] grocery store had established itself by 1894, according to Langley’s San Francisco Directory. The store, with its slightly varied Romanization in the business listings of the day, occupied a space just three doors away from the legendary restaurant Hang Far Low at 713 Dupont. The commercial space was known for its provision stores, and Hang Yek & Co. followed at least two predecessors in the same location. Regrettably, the store did not survive the devastating earthquake and fire of 1906. By the time the city rebuilt, 717 Dupont Street—later renamed Grant Avenue—became the home of Tai Tung Yat Po, a daily Chinese newspaper (大同日報; canto: “daai6 tung4 yat6 bou3”).

Adjacent to Hang Yek & Co. were other key businesses that served Chinatown’s residents. Sic Kee & Co.(錫記; canto: “sek3 gei3″), a clothing store and tailor shop, operated at 715-1/2 Dupont Street; Ching Wo (正和; canto: “zing3 wo4″) , whose provisioning business is less well-documented, occupied 719 Dupont Street; and the Choy Jee Tong & Co.(采芝堂; canto: “choy2 zi1 tong4”) drugstore at 725 Dupont.

The listing for the Ching Wo (正和; canto: “zing3 wo4″) store at 719 Dupont St. from the 1892 Horn Hom Co. directory.

The listings for the Sic Kee & Co.(錫記; canto: “sek3 gei3″) tailorshop and the Choy Jee Tong & Co. druggist appeared in the 1882 Wells Fargo Chinese business directory.

Together, these stores contributed to the 700-block’s vitality at the southern end of Chinatown’s main shopping street.

“Dupont St. in China Town, San Francisco Ca” c. 1900. Photographer unknown from the Marilyn Blaisdell collection. In this elevated view north of the 700-block of the west side of Dupont Street, signage for the Sic Kee & Co. (錫記; canto: “sek3 gei3″) clothing store at 715-1/2, Hang Yek & Co. at 717, and a horse-drawn delivery wagon is parked in front of what was probably the Ching Wo (正和; canto: “zing3 wo4″) grocery store. In the right of the frame (across on the east side fo the street), the partially visible address sign of the Sun Kam Wah store across the street at 714-1/2 Dupont can be seen. The second horse-drawn wagon appears at the curb in front of the partially-obscured vertical sign for the Choy Jee Tong & Co.(采芝堂; canto: choy2 zi1 tong4”) drugstore at 725 Dupont.

This west side of the 700-block of old Chinatown’s Dupont Street, like much of San Francisco, would be destroyed and transformed in the aftermath of the 1906 disaster. Yet, the legacy of Chinatown’s early businesses, such as Hang Yek & Co., remains a testament to the resilience and industriousness of the city’s early Chinese residents during an urban pioneer era.

[updated 2024-10-24]

#Hang Yek & Co.#Sic Kee & Co.#Sun Kam Wah#Choy Jee Tong & Co.#Ching Wo#Hang Far Low restaurant#Colombo & Co. cigarmaker

0 notes

Text

Hang Far Low: Banquet culture starts here

(from the collection of the Chinese Historical Society of America)

This article has been updated. Please go here or click on the following link:

https://demospectator.tumblr.com/post/704950918501761024/the-business-signage-for-the-hang-far-low

#Hang Far Low#Chinatown#I.W. Taber#Colombo & Co. cigarmaker#Carleton Watkins#Thomas W. Chinn#Long Kong Tin Yee Association#Tin Yee Association#Mu Tin association#Louis J. Stellman#Chinatown banquet culture

0 notes