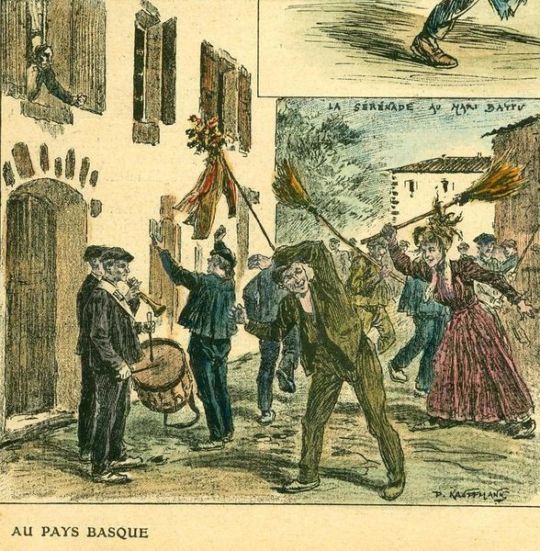

#Charivari

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Riesen Charivari (decorative chain)

173 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pomp Charivari, southern Germany, 19-20. century.

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

E.P. Thompson explains the charivari’s motivation in eighteenth-century Britain:

"Publicity was of the essence of punishment. It was intended, for lesser offences, to humiliate the offender before her or his neighbours, and in more serious offences to serve as example (480).

...

A rough music was a licensed way of releasing hostilities which might otherwise have burst beyond any bounds of control … The argument that rough music rituals were a form of displacement of violence – its acting out, not upon the person of the victim, but in symbolic form – has some truth … Rough music did not only give expression to a conflict within a community, it also regulated that conflict within forms which established limits and imposed restraints’ (486).

...

... the rough music charivari ‘announces disgrace, not as a contingent quarrel with neighbours, but as judgement of the community. What had before been gossip or hostile glances becomes common, overt, stripped of the disguises which, however flimsy and artificial, are part of the currency of everyday intercourse … The victim must go out into the community the next morning, knowing that in the eyes of every neighbour and of every child he or she is seen as a person disgraced. It is therefore not surprising that rough music, except in its lightest forms, attached to the victim a lasting stigma’ (487–8)

...

‘Even where no “court” of judgement existed, the essential attribute of rough music appears to be that it only works if it works: that is, if (first) the victim is sufficiently “of” the community to be vulnerable to disgrace, to suffer from it: and (second) if the music does indeed express the consensus of the community – or at least of a sufficiently large and dominant part of the community … to cow or to silence those who, while perhaps disapproving of the ritual, shared in some degree the same disapproval of the victim’ (491–2).

...

‘Rough music could also be an excuse for a drunken orgy or for blackmail … It is a property of a society in which justice is not wholly delegated or bureaucratised, but is enacted by and within the community … And the psychic terrorism which could be brought to bear … was truly terrifying’ (530).

...

Rough music belongs to a mode of life in which some part of the law belongs still to the community and is theirs to enforce … It indicates modes of social self-control and the disciplining of certain kinds of violence and anti-social offence … which in today’s cities may be breaking down. But when we consider the societies which have been under our examination, one must add a rider. Because law belongs to people, and is not alienated, or delegated, it is not thereby made more ‘nice’ and tolerant, more cosy and folksy. It is only as nice and tolerant as the prejudices and norms of the folk allow. Some forms of rough music disappeared from history in shadowy complicity with bigotry, jingoism and worse … For some of its victims, the coming of a distanced (if alienated) Law and a bureaucratised police must have been felt as a liberation from the tyranny of one’s ‘own.’ (530–1) - quotes from E. P. Thompson, Customs in common. New York: New Press, 1993.

All quoted in Pauline Greenhill, Make the Night Hideous: Four English-Canadian Charivaris, 1881–1940. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2010.

#e. p. thompson#rough music#customs in common#charivari#wedding ceremony#marriage#regulation of marriage#regulation of morality#working class culture#eighteenth century england#criminality#crime and class#history of crime and punishment#reading 2024

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

🪽Vamos

🪽Gipsy Kings

Muro con

@haeck.cv

@dyva.cv

🙏✨

muchas

gracias por la

visita.

Siempre

bienvenidos.

Pondré fotos del

muro completo

y el proceso.

✨✨✨

#hanem #bamos #

#gipsykings

#dyba #haeck

#charivari #wall

#graffitiwall

#graffiti #letters

#graffitiletters

#slowlife

👟

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sept/Oct

Sleep at night - - - - - -----> optional

Sleep around 3-4am - - - -> certainly not!

Unacknowledged presence of mosquitoes still in my room - - - - - - - -> fuck yes. (Outside temperature : 12-14°C)

Presence admitted of some agitated enthusiasts spirits and their charivari, voices, noises and dreams (but I mustn't sleep too much either, remember, lol) - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -- - -> Y E S

I'm probably very slow to process this UTTERANCE - - - - - - - - - -- - - -> yesyesyes

Meanwhile, during the day I try to have a life—------------> unacceptable!

OK.

Happy Halloween Eve Trap, everyone 👻🎃☠️

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Charivari, the Caller of the Unexpected! or as i called her in my files for like 5 months, flaming clown magical girl.

#perianthposts#perianthart#fairy utopia calling keeps au#original art#magical girl#charivari#clip studio paint#look at herrrrrrr

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Waltons were Right -- History of the Charivari

Have you heard of this? I found it in Carol Bennet McCuaig’s book Invisible Women- Deb Shea A few weeks ago I watched and Episode of The Waltons called The Shiveree. Shivaree, or chivaree, was a traditional Mountain folk custom staged during the first night that a bride and groom, following the honeymoon, moved into their new residence (even if it happened to be with relatives in their old…

View On WordPress

#almonte#Carleton-Place#Charivari#genealogy#History#Lanark-County#marriage#married#Mississippi mills#ontario#the waltons

1 note

·

View note

Text

youtube

marcel - playroom

0 notes

Text

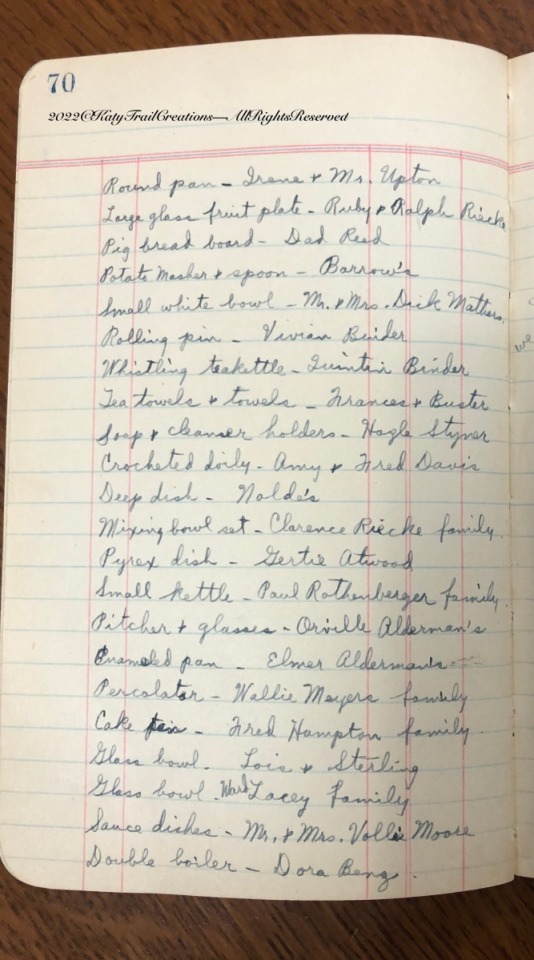

Shower and Charivari / Inez's Clippings

Shower and Charivari / Inez’s Clippings

View On WordPress

#1942#2022#Charivari#Day Journal#family#Grandmother#Grandpa#Inez&039;sClippings#newspaperclippings#Wedding

0 notes

Text

We already have a *beautiful* Chase in dirndl so here's Buddy in my set :3c I also put him in schwäbische tracht (yay) anddddd what people actually wear where I'm from (less yay)

#idk why he doesnt want to wear a 2kg hat full of pompoms ¯\_(ツ)_/¯#he tied the apron bow on the right hehehe >:3c sorry everyone he is in fact taken#disclaimer i'm not actually german#i think it would be cute if he had a little charivari with his key on it but i didn't wanna draw it whoops#cbculturechallenge#cinderella boy#my art

59 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Charivari comprises a cross-cultural range of originally European practices, symbolic means, and purposes. At their most extreme, charivaris approach or even achieve riot status; when benign they are simply playful gatherings. They include noisemaking, house visiting – usually unexpected and late at night – and often pranks. Most are associated with weddings – demonstrating approval of matches the community deemed suitable, or the converse, showing or stirring up disapproval of old/old, old/young, interracial, or inter-religious ones. Still others provide overt negative commentary on individuals’ behaviour, particularly in the political and sexual realms (see Alford 1959; Amussen 1985; Atwood 1964; Burke 1978; Davis 1975, 1984; Desplat 1982; DeVoto 1947; Dobash and Dobash 1981, 1992; Dufresne 2000; Greer 1993; Ingram 1984, 1985; Jones 1990; Kent 1983; Le Goff and Schmitt 1981; Pettitt 1999; Rey-Flaud 1985; Thompson 1992, 1993; Underdown 1985, 1987; Ziff 2002).

There has long been a range of wedding-associated practices usually gathered by academics under the heading of charivari (LeGoff and Schmidt 1981). In English Canada, charivaris were probably historically associated most often with heterosexual marriages considered in some way problematic by the communities in which they took place. In that form, charivari can be understood as an extra-legal mode of social control, ‘to publicly ridicule an object of communal scorn’ (Gilje 1996, 47). Historian Natalie Zemon Davis argues, ‘At best, a charivari in its boisterous mixture of playfulness and cruelty tries to set things right in a community’ (1984, 42). According to sociologists Russell P. Dobash and R. Emerson Dobash in their discussion of historic charivaris, ‘Public shamings were attempts to make unspeakable community grievances and private disputes into matters of community concern’ (1981, 565). At their worst, charivaris were a kind of local terrorism – directed to specifically punish a wrongdoer, but also making an example for the rest of the community to show what would happen if they were to do likewise – culminating, particularly in the case of interracial marriages, in murder (e.g., Moodie 1997; Roberts 2002). However, even negative charivaris by no means always led to bad outcomes; usually the recipients simply paid the charivariers to go away, because ‘accepting to make the payment demanded by the crowd brought charivaris and community disapproval to an end’ (Noël 2003, 61).

Canadian historian Bryan Palmer notes, ‘In nineteenth-century Upper Canada … the charivari was often a force undermining social authority, resolutely opposed by magistrate and police’ (1978, 24–5). Specifically, for example, ‘Three Kingston, Upper Canada, charivaris of the mid-1830s, all directed against remarriage, forced the hand of the local authorities, one leading to two arrests, another necessitating the calling into action of the Summary Punishment Act, the third leading to the creation of a special force of constables, 40 strong, to enforce the peace’ (ibid., 26). Just because it opposed formal legal structures, however, does not mean that charivari was not in its own way a quasi-legal form – enforcing good behaviour by negative example (this is what happens when you step outside the bounds of community morality) as well as punishing specific culprits. Well into the twentieth century, charivaris certainly provided a context for both criminal and civil charges. The combination of guns (used as noisemakers) and alcohol (lubricating the participants) made bodily harm and even homicide a rare but nevertheless predictable outcome. Recipients of charivaris sometimes brought trespass charges, and other illegal acts such as disturbing the peace and public drunkenness also occasioned court cases.

The significance of the quête manifests the charivari’s quasi-legal form. Reciprocity and mutual obligation were significant in working-class culture in the nineteenth century, as evidenced by the practice of the tavern ‘treat’:

Commensurate with early tavern culture was the practice of treating or the buying of rounds of liquor for all men present. Those on the receiving end were obliged to drink and to reciprocate at a later date, and those treating others were obligated by expenditure. Such obligatory expressions of manhood and economic exchange exhibited character and reputation that invoked a certain fraternity among drinking men’ (Wamsley and Kossuth 2000, 417).

[A] 1881 Ottawa charivari ... shows that the wedding of two older people (including the further problematic aspects of differing ages, widow- and widowerhood of the parties, and divorce) called for a payment in recompense to young men. That payment was also clearly part of the culture of reciprocity among those young men themselves, as the first set of charivariers went to a tavern to drink together. In some ways, the charivari treat money was a fine paid by the couple for their contravention of expectation. As Allan Greer argues, ‘More was involved than a simple clearing of the air; charivari was also … a punitive procedure. Victims were punished through both humiliation and monetary extraction’ (1993, 77). That fine, however, needed to be redistributed in a specific way, just as legal fines are paid to the court, not to a wronged individual.

But the notion of reciprocity and sharing of wealth is equally significant in rural cultures, as the examples of early- to mid-twentieth century western Canadian charivaris show. Individuals and communities survived the rigours of farming, economic depression, and wartime (among many others) primarily by working together, and the reciprocity of the treat echoed and cemented the relations involved. However, as the charivari changed from disapproval to a more positive statement, the quête as a collection of money – mere exchange value – was replaced by a treat in the form of specific commodities marking special occasions, such as alcohol, candy, and cigarettes, or, alternatively, as a full-blown party with sociability as well as consumption. Crucially, though it did not involve money, and sometimes not even the sharing of alcohol (though in the alternative, ritual tea and coffee would be served) that often marks a social occasion, this part of the charivari was frequently still called a ‘treat.’ The common nomenclature of charivari/shivaree is not surprising, however, especially considering that it retained the form of a special kind of sharing and reciprocity among community members.

The culture of the rural ‘good sport’ underlines these ideas of redistribution. Good sports are quintessential community participants, who endure hardships together but who also celebrate together. The quality of being able to take a joke, to laugh at oneself as well as at others, extensively comprises the male bonding experience of rural western Canadian good sports (Taft 1997). The development of solidarity means that no one must be consistently elevated or, conversely, debased. This notion of equality persists across the contemporary charivari. Reciprocity employs the notion that no individual should be markedly wealthier than another; similarly, no individual should be ritually raised above others – as happens during a wedding, when the bride and groom are the centre of attention – without experiencing some parallel ritual debasement (often seen in sexualized humiliation in charivari tricks).

The links between the earlier (disapproval) and later (approval) charivari are underlined further by the fact that just because a charivari was intended as a celebration of the wedding did not necessarily preclude damage or harm. Often such events came to the attention of the authorities because of problems that arose. According to folklorist Monica Morrison, who studied New Brunswick serenades:

General questioning also brought [this] response, especially from women. “I don’t like that kind of thing, it can go too far,” followed by a sort of cautionary tale … “This guy he was drunk and he put a fire extinguisher – a fire hose – he put the stuff in it in the groom’s drink … And he drank it and that poor guy was unconscious for two days … and that guy his kidneys were shot and they had to take them out and he died within a week. And that guy who did it, he didn’t know that the chemical was poison, he probably thought it was just water. But that’s where that sort of thing goes’ (1974, 295).

- Pauline Greenhill, Make the Night Hideous: Four English-Canadian Charivaris, 1881–1940. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2010. p. 17-19

#canadian history#charivari#wedding ceremony#marriage#trick or treat#regulation of marriage#farming in canada#rural canada#working class culture#reciprocity#mutual assistance#academic research#reading 2024#make the night hideous#racism in canada

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Two men reading Le Charivari by Honoré Daumier, 1840.

Happy Eighteen-Forties Friday, my friends!

#Eighteen-Forties Friday#1840s#honoré daumier#le charivari#monarchie de juillet#early victorian era#huge newspaper comics decade

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

Une journée à Arras avec le copain Philippe : un resto savoyard-chti au menu plantureux (pour moi, un gratin de crozets) vers la Grand-Place, aux belles façades de style baroque flamand (reconstruites à l'identique après les ravages de 14-18)... Quasiment toutes ont une cave dont l'accès se fait par un escalier extérieur.

3 notes

·

View notes