#Carmen Kynard

Text

Day 5

There was and is a lot of woman who had a great impact in pedagogy that i didn't know about, because most findings are credited to men Although, woman are pionners in most of these discoveries. And this still happens to this day not only to teachers but also students, they are still affected by this hierarchy.

I can't speak on this matter but i can educate myself and be aware so i am going to share some sites that can truly express this issue from awoman on the field and that i used to try grasp the surface of it.

Kynard, Carmen and Eric Darnell Pritchard. "'When and Where I enter': History, Black Feminist Thought and Pedagogy." Tracing the Stream, August 2022, https://www.tracingthestream.com/when-and-where-i-enter-history-black-feminist-thought--pedagogy.html.

AECT Interactions (April 19, 2023) How to Embrace Feminist Pedagogies in your Courses. Retrieved from https://interactions.aect.org/how-to-embrace-feminist-pedagogies-in-your-courses/.

by Enilda Romero-Hall

Gender and Education Association GEA http://www.genderandeducation.com/issues/feminist-pedagogy/

Page Author: Emily F Henderson

0 notes

Quote

We know from education research that working class/working-poor Black and Latin[x] students are more likely to have instruction delivered to them from the most underpaid, novice, and/or uncertified teachers.

Carmen Kynard, “Writing while Black: The Colour Line, Black discourses and assessment in the institutionalization of writing instruction”

1 note

·

View note

Quote

The histories that we speak shape the beliefs that we act on.

Carmen Kynard, Vernacular Insurrections: Race, Black Protest, and the New Century in Composition-Literacies Studies

4 notes

·

View notes

Quote

This idea that a teacher need not learn about Asian bodies because having their presence in a classroom is enough becomes fraught with problems. Two white female students once even visited my office to inform me, given their history of having taught many African American Students, that Elaine Richardson (and myself since I upheld Richardson's position) did not fully understand how much better schools are for black people now and, as such, Richardson and I were distorting the truth. These two women even claimed to relate better (than Richardson and me) to African Americans given their Italian and Irish backgrounds, since they, after all, have experienced the same discriminations as blacks

Carmen Kynard, “Teaching While Black: Witnessing and Countering Disciplinary Whiteness, Racial Violence, and University Race-Management” (5)

0 notes

Photo

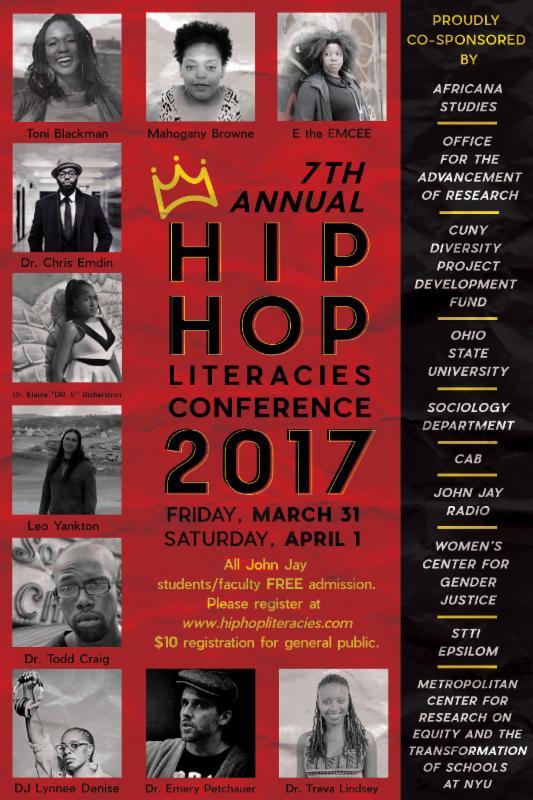

7th Annual Hip-Hop Literacies Conference feat. Toni Blackman, Mahogany Browne, Dr. Todd Craig, E the EMCEE, Dr. Chris Emdin, DJ Lynneé Denise, Dr. Treva Lindsey, Dr. Emery Petchauer, Dr. Elaine Richardson & Leo Yankton

Organized by Drs. Crystal Endsley, Elaine Richardson, and Carmen Kynard

Hosted by John Jay College of Criminal Justice of the City University of New York

March 31st-April 1st, 2017

The Graduate Center | 365 Fifth Avenue New York, NY 10016

Admission: $10

Get the conference schedule and registration information at: http://www.hiphopliteracies.com/#sthash.845Q5vIW.dpuf

For more information, email [email protected] or call 212.817.2076

This year's Hiphop literacies conference compels us to ask: What is Hip-Hop's ongoing (re)vision and (re)valuing of Black life and culture in the Third Post-Reconstruction? How do Brown and Black peoples who are threatened by Trump's walls get ready to respond to and resist through Hiphop culture? How does Hiphop stand with Standing Rock and stand against colonization set in motion centuries ago? What are the hetero-patriarchal scripts that Hip-Hoppas will now rewrite? How will we sustain, maintain, and thrive as a legacy of our cultural survival?

The purpose of the Hiphop Literacies conference is to bring together scholars, educators, activists, students, artists, and community members to dialogue on pressing social problems. This year our working conference theme is Hiphop Justice (Hiphop in the 3rd Reconstruction). Participants of the Hiphop Literacies Conference join a community of those concerned with African American/Black, Brown and urban literacies who are interested in challenging the sociopolitical arrangement of the relations between institutions, languages, identities, and power through engagement with local narratives of inequality and lived experience in order to critique a global system of oppression. Literacies scholars who foreground the lives of Hiphop generation youth see Hiphop as providing a framework to ground work in classrooms and communities in democratic ideals.

Toni Blackman is an international champion of hip-hop culture, known for the irresistible, contagious energy of her performances and for her alluring female presence. She's all heart, all rhythm, all song, all power, a one-woman revolution of poetry and microphone. An award-winning artist, her steadfast work and commitment to hip-hop led the U.S. Department of State to select her to work as the first ever hip-hop artist to work as an American Cultural Specialist. She recently toured Southeast Asia with Jazz at Lincoln Center's Musical Ambassador program and has shared the stage with the likes of Erykah Badu, Mos Def, The Roots, Wu Tang Clan, GURU, Bahamadia, Boot Camp Clic, Me'Shell NdegeoCello, Sarah McLachlan, Sheryl Crow, Jill Sobule and even Rickie Lee Jones. Her first book, Inner-Course was released in 2003 (Villard/Random House).

Mahogany Browne The Cave Canem, Poets House & Serenbe Focus alum, is the author of several books including Redbone (nominated for NAACP Outstanding Literary Works), Dear Twitter: Love Letters Hashed Out On-line, recommended by Small Press Distribution & About.com Best Poetry Books of 2010. Mahogany bridges the gap between lyrical poets and literary emcee. Browne has toured Germany, Amsterdam, England, Canada and recently Australia as 1/3 of the cultural arts exchange project Global Poetics. Her journalism work has been published in magazines Uptown, KING, XXL, The Source, Canada's The Word and UK's MOBO. Her poetry has been published in literary journals Pluck, Manhattanville Review, Muzzle, Union Station Mag, Literary Bohemian, Bestiary, Joint & The Feminist Wire.

Dr. Todd Craig

As a product of Ravenswood and Queensbridge Houses in Queens, New York, Dr. Todd Craig is a writer, educator and DJ whose career goal involves meshing his love of writing, teaching and music. Craig straddles the genres of fiction, creative non-fiction, and poetry, with texts that paint a vivid depiction of the urban lifestyle he experienced in his community, and listened to in hip-hop music. However, his formal academic training allows him to express the hope and infinite possibilities people of color have in their daily lives. Craig completed his doctorate in English at St. John's University where he was selected as the Hooding Ceremony Student Keynote Speaker and awarded the Academy of American Poets Prize. Craig's research interests include composition/ rhetoric, hip-hop pedagogy, African-American literature, multimodality in the Composition classroom and creative writing pedagogy and poetics.

E the EMCEE will represent Science Genius B.A.T.T.L.E.S. at the Hiphop Literacies 2017 conference. Science Genius BA.T.T.L.E.S. is an initiative that is focused on utilizing the power of hip-hop music and culture to introduce youth to the wonder and beauty of science. The core message of the initiative is to meet urban youth who are traditionally disengaged in science classrooms on their cultural turf, and provide them with the opportunity to express the same passion they have for hip-hop culture for science. Concurrently, the project aims to display the interests of science enthusiasts who have a passion for hip-hop, and introduce both hip-hop and science to a wider audience. Together, Chris Emdin and Rap Genius sponsor Science Genius. For more information, click here.

Dr. Chris Emdin is an associate professor in the Department of Mathematics, Science, and Technology at Teachers College, Columbia University, where he also serves as Associate Director of the Institute for Urban and Minority Education. The creator of the #HipHopEd social media movement and Science Genius B.A.T.T.L.E.S., author of the award-winning book Urban Science Education for the Hip-Hop Generation and the New York Times Best Seller, For White Folks Who Teach In The Hood and the Rest of Ya'll Too. Emdin was named the 2015 Multicultural Educator of the Year by the National Association of Multicultural Educators and has been honored as a STEM Access Champion of Change by the White House under President Obama. In addition to teaching, he served as a Minorities in Energy Ambassador for the US Department of Energy.

DJ Lynneé Denise

For the past decade, DJ Lynneé Denise has worked as an artist who incorporates self-directed project based research into interactive workshops, music events and public lectures that offer participants the opportunity to develop an intimate relationship with under-explored topics related to the cultural history of marginalized communities. She creates multi dimensional and multi sensory experiences that require audiences to apply critical thinking to how the arts can hold viable solutions to social inequality. Her work is informed and inspired by underground cultural movements, the 1980s, migration studies, theories of escape, and electronic music of the African Diaspora. She's the product of the Historically Black Fisk University with a MA from the historically radical San Francisco State University Ethnic Studies department.

Dr. Treva Lindsey is an Associate Professor of Women's, Gender, and Sexuality Studies at The Ohio State University. Her research and teaching interests include African American women's history, black popular and expressive culture, black feminism(s), hip hop studies, critical race and gender theory, and sexual politics. Her first book is Colored No More: Reinventing Black Womanhood in Washington D.C. She has published in The Journal of Pan-African Studies, Souls, African and Black Diaspora, Transnationalism, Urban Education, The Black Scholar, Feminist Studies, Signs, and the edited collection, Escape from New York: The New Negro Renaissance Beyond Harlem. She is the inaugural Equity for Women and Girls of Color Fellow at Harvard University (2016-2017). She is also the recipient of several awards and fellowships from the Woodrow Wilson Foundation, the Social Science Research Council, the Andrew W. Mellon.

Dr. Emery Petchauer is Associate Professor of English and Teacher Education at Michigan State University where he also coordinates the English Education program. His research has focused on the aesthetic practices of urban arts, particularly hip-hop culture, and their connections to teaching, learning, and living. He is the author of Hip-Hop Culture in College Students' Lives (Routledge, 2012), the first scholarly study of hip-hop culture on college campuses, and the co-editor of Schooling Hip-Hop: Expanding Hip-Hop Based Education Across the Curriculum (Teachers College Press, 2013). Nearly two decades of organizing and sustaining urban arts spaces across the United States inform this scholarly work. Dr. Petchauer also studies high-stakes teacher licensure exams and their relationship to the racial diversity of the teaching profession.

Dr. Elaine Richardson

Cleveland, Ohio native, Dr. Elaine Richardson is currently Professor of Literacy Studies at The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio, where she teaches in the Department of Teaching and Learning. Her books include African American Literacies, (2003, Routledge) and Hiphop Literacies (2006 Routledge). Her urban education memoir, PHD (Po H# on Dope) to PhD: How Education Saved My Life, (2013, New City Community Press) chronicles her life from drugs and the streetlife to the award-winning scholar and university professor, art activist: Richardson has also co-edited two volumes on African American rhetorical theory, Understanding African American Rhetoric: Classical Origins to Contemporary Innovations (2003, Routledge) and African American Rhetoric(s): Interdisciplinary Perspectives (2004, Southern Illinois University Press). She was Fulbright lecturing/researcher in the department of Literatures in English at the University of the West Indies, Mona, Jamaica.

Leo Yankton from the Lakota Nation.

We want to keep the momentum rolling forward from previous conference themes where we have examined the intersections of Hiphop, critical education/literacies, the current BlackLivesMatter movement, activism-artistry, social stratification, globalization, popular culture and technology.

Dr. Todd Craig, E the EMCEE, Dr. Chris Emdin, DJ Lynneé Denise, Dr. Treva Lindsey, Dr. Emery Petchauer, Dr. Elaine Richardson & Leo Yankton

Organized by Drs. Crystal Endsley, Elaine Richardson, and Carmen Kynard

#hip hop#conference#ip-Hop Literacies Conference#toni blackman#Mahogany L. Browne#hip-hop and politics#Dr. Todd Craig#E the EMCEE#Dr. Chris Emdin#DJ Lynneé Denise#Dr. Treva Lindsey#Dr. Emery Petchauer#Dr. Elaine Richardson#Leo Yankton#Carmen Kynard#Dr. Crystal Endsley

0 notes

Quote

No post-colonialist, no critical theorist, no African Americanist, and no queer theorist thought anything of this situation because they counted on white supremacy to let them sit on the sidelines and observe violence, racially mark the black male student as 'difficult'; racially mark me as angry and inappropriate (I never seemed to pick the 'right time' to discuss race with white people); and racially mark the white woman as 'innocent' and 'victim.'

Teaching While Black: Witnessing and Countering Disciplinary Whiteness, Racial Violence, and University Race-Management, Carmen Kynard

1 note

·

View note

Quote

When discussions about race, culture, and whiteness go down in my graduate classrooms, it is often students of color who challenge white students, rarely other white students though many of them claim to do critical literacy teaching, anti-racist advocacy, and research amongst students of color.

“Teaching While Black: Witnessing and Countering Disciplinary Whiteness, Racial Violence, and University Race-Management” -- Carmen Kynard

1 note

·

View note

Quote

Thus, on the one hand, English departments organize the use of cheap labor for the supra-income-generating composition course/product (given how many students take these courses, often many times, in comparison to how much their instructors earn); and on the other hand, they re-code the elite, high-brow gate-keeping of (literacy) discourses and language by removing freshman English teachers and their students.

Carmen Kynard, “Writing While Black: The Colour Line, Black Discourses and Assessment in the Institutionalization of Writing Instruction” (7)

0 notes

Text

Reflection 3

Writing, Literacy, and Discourse

11 November 2020

There is a unique linguistic expression that black Americans originated and can possess that can be referred to as African American Vernacular English, AAVE, or Black English. Black English is most often an oral tradition but over time, due in part to black people gaining access to literacy, it has been recorded through physical writing, online media, and even on one’s skin. AAVE is a powerful tool of the black community but it does face stigmatization and has been associated with illiteracy, stupidity, and a lack of education. As most media has become digitized over the past 20 years, “Afro-digitization” has arisen tangentially. Most interestingly, tattoos have evolved to be part of black culture and have their own symbolic meanings as a visual media. The black community has an extraordinary ability to utilize existing forms of communication and apply special meaning and significance to them.

It is said that AAVE began to sprout roots within the first century of the British colonization of America (Winford). Because slavery prohibited the education of African Americans in any way, they developed their own version of English using elements derived from the English dialects of British settlers, their native African languages, and potentially even some creole influence coming from slaves from the Caribbean (Winford). AAVE is deeply intertwined with black American history and has evolved through the centuries. Within the black community, it has been the common vernacular and is usually viewed as a key aspect of the African American experience. Outside of the community, it is associated with ignorance and a lack of intelligence. This is intentional as nearly all aspects of blackness in America are demonized. While accents, like a country one, may be viewed as less than articulate, they are still accepted as a valid approach to the English language. June Jordan writes about her experience as a professor who eventually comes to teach a class on Black English. She also discusses how a student’s brother is shot and killed by a police officer and how her student’s respond to the tragedy. All semester, Jordan would preach the power, beauty, and significance of Black English, therefore it is no surprise the students wanted to address the police in their and Reggie Jordan’s, the victim, native language (133). Standard English is literally the language of his murderer, but the students were afraid they would not be taken seriously; they were right and their message was rejected by every news outlet they reached out to (Jordan 134). Even with this widespread rejection of Black English, it is still widely used by the black community and can be found anywhere black people are.

One can even find Black English in every corner of the internet. It is almost more common online, as code-switching is not as much of a necessity in spaces like Tumblr blogs, YouTube, or “Black Twitter.” The intended audience of online black authors is often other black people which has allowed “Afro-digitalization” to take place. Of course, there are still digital pieces of media produced by black people written or spoken in Standard English, but it seems that the target audience determines which is preferred and chosen. Carmen Kynard notes that the way her black students interacted with technology was influenced by their unique histories and experiences (143). Her findings also suggested that Black English created an environment that allowed for complex discussions among her students (145). Standard English leaves little room for successful sarcasm or deep passion, but online AAVE grants a deeper expression of emotion and intention. Black English lacks strict grammatical rules so elements like capitalization for emphasis or lack of punctuation to express a continuous stream of thoughts are perfectly legitimate choices. It seems that black people made a choice to approach online spaces using the vernacular they are most comfortable with and ran with it. Kynard argues for the use of AAVE in digital academic settings, but the basic principles of “Afro-digitalization” may be observed all over the internet. “Afro-digitalization” extends beyond language and can include how black people interact with any online resource; it could be argued that the manner in which black people share recipes in a visual form where they emphasize spices, like Lowry’s or Old Bay, or when sharing their choreographed dances there is emphasis on facial expressions and energy are further examples of “Afro-digitalization” as these are aspects of black culture in real life being displayed digitally.

Tattoos outside of the Western world almost exclusively hold a cultural significance, as opposed to their primarily aesthetic Western purpose. In the black community, tattoos fulfill both functions simultaneously. David Kirkland explores this precise phenomenon through his study of Derrick Todd’s tattoo collection (157). Kirkland describes these chosen tattoos as a form of literacy which “implies a potential to make meaning and an opportunity to comment on one’s reality through a symbol system that uses more than words” (158). Todd explains how his tattoos hold significance to him but also communicate to the world ideas and experiences he wants to share. Kirkland goes on to discuss tattoos as a mechanism of coping and maintains a conversation about the multifaceted aspects of tattoos, such as them sharing something about the person they are engraved in but they can also be about other people, like loved-ones (166). These chosen physical engravings are personal but are also social (171). Just like all forms of communication, the tattoos serve to say something; and the black community understands this and attempts to listen to their meaning, purpose, and messaging.

Black people have always been able to establish a distinct culture, even with the oppression they have faced, sometimes the culture develops directly from that oppression. A restriction from Standard English motivated the creation of African American Vernacular English. A lack of room for discussion by, for, and about black people prompted the creation of black spaces on the internet which allowed “Afro-digitalization” to occur. Within the black community, tattoos are known to hold cultural and aesthetic significance, and they reveal information about the individual they are inscribed upon. These are different manners in which black literacy has manifested itself. They are all so different and creative, but primarily, they express the resilience of the black spirit and the desire to be heard.

Works Cited

Jordan, June. “Nobody Mean More to Me Than You and the Future Life of Willie Jordan.” Visions and Cyphers: Explorations of Literacy, Discourse, and Black Writing Experiences, edited by David F. Green, Inprint Editions, 2016, pp. 123–135.

Kynard, Carmen. “‘Wanted: Some Black Long Distance [Writers]’: Blackboard Flava-Flavin and Other AfroDigital Experiences in the Classroom.” Visions and Cyphers: Explorations of Literacy, Discourse, and Black Writing Experiences, edited by David F. Green, Inprint Editions, 2016, pp. 137–154.

Kirkland, David. “The Skin We Ink: Tattoos, Literacy, and a New English Education.” Visions and Cyphers: Explorations of Literacy, Discourse, and Black Writing Experiences, edited by David F. Green, Inprint Editions, 2016, pp. 156–174.

Winford, Donald. “The Origins of African American Vernacular English.” Oxford Handbooks Online, 1 July 2015, www.oxfordhandbooks.com/view/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199795390.001.0001/oxfordhb-9780199795390-e-5#:~:text=The roots of AAVE were,in the Carolinas and Georgia.

0 notes

Quote

We need What LaNita Jacobs Huey has described as the native "gazing and talking back in ways that explicit interrogate the daily operation of white supremacy in our field and our campus rather than more performances of psychologically-internalized black pain for the white gaze(a practice that garners white attention and consumption, but never social change).

Teaching while Black,Carmen Kynard.

0 notes

Quote

...the [rhetoric and composition] community is not aligned either with the content-worldview of [black students]...Though there are numerous works about the unique, linguistic competencies of students of African descent, the dehumanizing experiences that these students face as endemic to their education have not been ameliorated

Carmen Kynard (2008) “Writing while Black: The Color Line, Black Discourses and Assessment in the Institutionalization of Writing Instruction,” English Teaching: Practice and Critique 7.2 (p. 22).

0 notes

Quote

The predominance of underpaid and/or under-trained educators in secondary schools, particularly as it relates to the multiple literacies of young people of colour, mirrors the structural racism that has organized much of the schooling that working class/working-poor Black and Latino students have received all along. We know from education research that working class/working-poor Black and Latino students are more likely to have instruction delivered to them from the most underpaid, novice and/or uncertified teachers; and, most critically, this kind of structure has had dire consequences on these students’ achievement

Carmen Kynard, “Writing While Black: The Colour Line, Black Discourses and Assessment in the Institutionalization of Writing Instruction” (6)

0 notes

Quote

The hyper-economic imperative of organizing cheap labour in higher education hits across all departments and schools in the context of the academy as a new, 'destabilized' but rapidly-growing market....these hiring, market-driven practices serve a larger, ideological function for the disciplines: in the case of English studies, this ideological function intersects directly with freshman English...These political economies, thus, script how English departments are often organized and, as such, as this article attempts to show, also script what Black students will be able to write and, therefore, who they are allowed to be/come as college writers/thinkers.

Carmen Kynard, “Writing while Black: The Color Line, Black discourses and assessment in the institutionalization of writing instruction” (7)

0 notes

Quote

To put it most bluntly and simply: working poor/Black and Latino students have seen inexperienced and un/der-trained teachers most of their (schooling) lives as part of the structuring of the colour line. To provide these students with yet another batch of inexperienced and un/der-trained teachers is/as freshman English (the gatekeeping course that allows entrance into all other, upper-level humanities and social science courses) dooms them to fail.

Carmen Kynard, “Writing While Black...”, p. 6

1 note

·

View note

Text

“I am offering my own personal experiences and stance of bearing-witness as more than just one individual’s observations, but an indication of the levels of systemic racism that we do not address. General discussions about moral and philosophical principles of equity, equality, or diversity are no longer good enough so I take up the tools that Allan Luke privileges: the tools of “story, metaphor, history, and philosophy, leavened with empirical claims,” all of which Luke argues are as integral to truth-telling and policymaking as field experiments and meta-analyses (368). I take up these tools in the context of myself as a writer and researcher of black language, education, and literacies and use narratives to offer stories of institutional racism that compositionists —and thereby, our field—have maintained. These narratives offer a place to decode the symbolic violence that is encoded into our disciplinary sense-making and move towards what a theory of Racial Realism might entail for our classrooms and discipline.”

- Carmen Kynard, “Teaching While Black”

0 notes

Text

"These kind of white Left anti-Ebonics polemics and politics (where the centrality of standardized English is wholly embraced) is like a woman who's slip is showin, as my grandmother might say: we get to see all that is going on up underneath the outer display. Lazere's is a strange kind of stance to take given a world where English is now dominant solely for the purpose of capitalist-based consumption. A class-critical stance on English will have to provide countertheories and praxis for challenging the ways that standardized English has been fantastically mobilized for current modes of capitalist prpduction thay schools and literacy instruction prepare youth for, rather than an othering and displacement of everyone's language who ain't middle class and white" - Carmen Kynard, "Vernacular Insurrections: Race, Black Protest, and the New Century in Composition-Literacies Studies"

0 notes